1. Introduction

The increasing participation of women and dual-earning couples in the workforce has exacerbated conflicts between work and family domains (

Hoobler et al., 2009;

Ongaki, 2019). In South Korea, the total number of dual-income households has steadily increased, from 5.37 million in 2015 to 5.675 million in 2020, and then to 6.116 million in 2023 (

Statistics Korea, 2024). Gender stereotyping that presumes a separation between work and family by gender is a traditional cultural norm in Korean society. These gendered norms pressure mother managers to prioritize family roles and responsibilities over their job (

Hoobler et al., 2009;

Oh & Mun, 2022). Particularly, female Korean managers face more challenges in devoting time, attention, and energy to achieving job performance, as managers who are mothers are presumed to assign more importance to family than to their job (

Shockley & Singla, 2011). In this context, the work-family conflict has become a significant issue in Korean society.

The nature of work-family conflict is multidimensional and bidirectional, involving mutual interference between family and work demands. To help address this, flexible work arrangements (FWAs) have been designed to provide more choice over working spaces and schedules (

Allen et al., 2013;

Adams & Schwarz, 2024). Existing literature has highlighted the potential benefits and detriments of FWAs in work-family relations: while they can alleviate work-family conflict, multitasking between work and family domains can also exacerbate inter-role pressures (

Allen et al., 2013). The mutual interference of work and family can increase stressful experiences, resulting in a loss of the resources and energy dedicated to work activities while also reducing organizational commitment (

Singh et al., 2018). Previous studies have presented mixed findings on the effectiveness of FWAs in alleviating work-family conflict (

Bayazit & Bayazit, 2019;

Kossek et al., 2023). This current study tests the extent to which FWAs provide employees discretion over their allocation of energy, attention, and time resources into work and family, which can reduce the strain associated with work-family conflicts.

Moreover, employees’ perceptions of CEO gender equality are presumed to intervene in the effects of work-family conflict on organizational commitment. CEO gender equality perceptions refer to the extent to which employees believe their CEO prioritizes gender equality when shaping and developing human resource management (HRM) practices and programs (

Joo et al., 2023). Higher levels of CEO gender equality perceptions can help alleviate the stereotyping of female workers, which highlights the importance of family roles as well as work roles. CEOs who prioritize gender equality can create an environment that enables employees to effectively balance their work and family responsibilities. Thus, CEO gender equality perceptions can enhance organizational commitment by shaping and developing employees’ beliefs that the organization will help them address conflicting demands related to work and family.

Furthermore, family roles and demands are perceived as more salient for working mothers, as social pressures and gender stereotyping urge female employees to prioritize family, and they tend to be more involved in family matters (

Shockley & Singla, 2011). Working mothers often perceive more interference between work and family (

Hoobler et al., 2009); therefore, gender may determine the activation of family identity, which significantly affects the level of perceived work-family conflict. Notably, there may be a significant gender difference in employees’ perceptions of CEO gender equality and organizational commitment, which are closely associated with work-family conflict levels.

This study contributes to the literature on FWAs and organizational commitment through a longitudinal study based on three years of data, identifying how and when FWAs are effective. Specifically, it investigates the roles of work-family conflict and CEO gender equality perceptions as underlying mechanisms. Additionally, it reveals a distinct gender difference, setting it apart from previous studies: FWAs are more effective for male managers than female ones. These findings have managerial implications for HR practitioners in implementing and utilizing FWAs within organizations. Specifically, it is not just about implementing FWAs into an organization; it is about setting the climate for managers to actually use them.

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

2.1. FWAs and Work-Family Conflict

Previous studies have suggested that FWAs support managers who are parents in resolving the challenges associated with work-family conflict. Time, attention, and energy are finite resources that must compete in these domains (

Shockley & Singla, 2011). FWAs are considered to offer employees control over organizing and negotiating work-family boundaries (

Allen et al., 2013), as parents can use them to adjust the scope of work and family domains.

FWAs blur the demarcation of work and family domains, increasing self-control over schedules, locations, and procedures for carrying out work tasks (

Allen et al., 2013;

Ongaki, 2019). They also enhance the physical and psychological well-being of managers who are also parents, helping to balance conflicting interests. Thereby, implementing FWAs can positively influence parent managers’ control over the conflicts caused by fulfilling work and family roles.

Hypothesis 1. FWAs negatively influence work-family conflicts.

2.2. FWAs, Work-Family Conflict, CEO Gender Equality Perception, & Organizational Commitment

Work-family conflict can become exacerbated when the roles and demands between work and family domains are incompatible. As the conflict intensifies, it can drain the time and energy available for performing work and family roles (

Shockley & Singla, 2011). As this conflict increases, the resulting multitasking imposes role pressures. As work and family interfere with each other, organizational environments are perceived as obstructing the work and family role requirements. Traditionally, family roles and responsibilities are often seen as more salient for mothers. Thus, high levels of work-family conflict disadvantage mother managers more than fathers and can increase their stressful experiences (

Shockley & Singla, 2011). When managers struggle to simultaneously satisfy work and family demands, they may perceive that organizational policies and programs do not adequately support work-family balance. As mothers often assign more importance to family matters and responsibilities, this lack of support can be viewed as hindering gender equality. Because mother managers are stereotyped as devoting more time and attention to their family, their performance may be perceived as less than that of father managers, as organizations perceive fathers to be more compatible with workplace leadership requirements, causing organizations to be considered as less supportive of gender equality (

Cha, 2010;

Oh & Mun, 2022). Thereby, high levels of work-family conflict exacerbate negative perceptions of CEO gender equality.

Flexibility, enhanced through FWAs, allows managers to negotiate work-family boundaries (

Kossek et al., 2023). FWAs help managers manage family matters and responsibilities, as work-family boundaries are blurred to facilitate transitions between work and home (

Adams & Schwarz, 2024). Particularly, FWAs are more beneficial for managers as they can devote resources to satisfying family roles and demands. CEOs exert decision-making authority to influence the adoption and establishment of FWAs (

Vadvilavicius & Stelmokiene, 2024), which can be interpreted as their intentions to support work-family balance (

Joo et al., 2023). FWAs can mitigate the negative effects of work-family conflict on employees’ perceptions of a CEO’s gender equality philosophy by signaling that the CEO prioritizes work-family balance. When employees view CEOs as caring, they are more likely to reciprocate with positive attitudes toward the organization (

Wayne et al., 2013). Similarly, managers are likelier to commit to an organization in exchange for the CEO’s support of work-family balance through FWA implementation (

Sublet et al., 2024). Thereby, FWAs foster positive perceptions of CEO gender equality and organizational commitment by reducing work-family conflict.

Hypothesis 2. FWAs promote CEO gender equality perceptions and organizational commitment through reduced work-family conflict.

2.3. Gender Roles

Existing literature has suggested that FWAs are more effective for mother managers in promoting work-family balance (

Wayne et al., 2013;

Ongaki, 2019). As FWAs increase the permeability and flexibility of temporal, physical, and psychological work-family boundaries, female workers can utilize them to address gendered assumptions about family obligations. However, contrary to previous studies on FWAs and gender, this current study assumes that FWAs are more beneficial in supporting the work-family relations of fathers who are managers. Gendered assumptions in the workplace suggest that working fathers prioritize their job, while working mothers must commit to family care responsibilities (

Oh & Mun, 2022). Existing studies on working mothers have revealed that female managers tend to engage in a larger share of housework and childcare, which prevents them from fully committing to their job (

Cha, 2010).

The mothers sampled in this study work in professional and managerial roles. Working mothers in these positions tend to be highly committed to their career tracks (

Cha, 2010;

Shin & Kim, 2023). While their jobs may be demanding, they often prioritize the challenges associated with household labor and childcare responsibilities. Mother managers are often stereotyped as devoting resources to the family domain by avoiding difficult tasks and long work hours (

Shin & Kim, 2023). When they utilize FWAs to mitigate work-family conflicts, normative assumptions encourage them to prioritize family over work. However, as mothers in professional and managerial positions often strive for career success, they must juggle the transition between home obligations and work commitments (

Cha, 2010;

Oh & Mun, 2022). Working mothers in these positions may fear that FWAs stigmatize them by suggesting they prioritize their family over their job at the expense of their career (

Cha, 2010; Shin et al., 2023). Mothers may also be deemed less eligible for senior management positions due to relying on FWAs to resolve work-family conflicts. As FWAs can disadvantage the career paths of working mothers, they may feel less inclined to use FWAs to cope with incompatible work and family roles and demands.

Compared to mother managers, father managers are often expected to fully commit to job tasks; thus, FWAs may not be associated with their work-family relations. However, this present study assumes that FWAs can help working fathers mitigate work-family conflicts, which in turn promotes a more positive perception of CEO gender equity and organizational commitment. The findings of existing studies have indicated that perceiving organizational support for families can reduce a father’s work-family conflict (

Allard et al., 2011). Traditional gendered norms in the workplace assume that working fathers assume ‘breadwinning’ roles, devoting their time, attention, and motivation to work, while women take on homemaking roles (

Cha, 2010).

Recently, the ideology of gender roles has been extended to promote equal participation by fathers and mothers (

Huffman et al., 2014;

Sievers, 2023). Increasing the involvement of fathers contributes to the well-being of the family by providing social and emotional support (

Holmes et al., 2020). FWAs allow working fathers to share childcare responsibilities with their partners. Therefore, they help reduce work-family conflicts among working fathers, which can promote perceptions of CEO gender equity and increase organizational commitment. Ideal work schemes often require working fathers to prioritize job tasks and work overtime, while downplaying their family commitments (

Huffman et al., 2014;

Sievers, 2023). Thus, working fathers may find it challenging to use FWAs to balance work demands and family responsibilities.

As mentioned, the sample in this study consists of working mothers and fathers who hold professional and managerial positions, which tend to be well-paid and offer work-life balance, particularly as employees in these roles have the time, attention, and energy resources to promote this balance. Working fathers in these positions often take a keen interest in familial obligations and childcare (

Holmes et al., 2020), motivated to balance their family commitments with their job performance and career advancement. Thus, father managers may rely on FWAs to maintain involvement in childcare and family roles by adjusting the time, space, and methods of their work.

Hypothesis 3. Gender moderates the interrelated relationships among FWAs, work-family conflict, CEO gender equality perceptions, and organizational commitment.

Figure 1 depicts the serial mediation relations of the study variables. Gender moderates the relationship between FWAs and work-family conflict. In turn, work-family conflict reduces managers’ perceptions of CEO gender equality, and CEO gender equality perception increases their organizational commitment.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Study Sample

This study’s sample draws upon the Korea Women Manager Panel (KWMP),

1 conducted by the Korean Women’s Development Institute (KWDI), a research institute in Korea that promotes gender equality and family-supportive workplaces. As South Korea ranked at the bottom of countries worldwide for female representation in the labor market, the glass ceiling poses significant challenges for the career development of women workers (

Lee et al., 2023). KWMP conducts an annual survey to track the career histories of female workers and identify the enablers and barriers that determine their career outcomes. It surveys the working conditions and family life of female and male managers, allowing for a gender comparison of career paths and work-family relations. KWMP’s survey is composed of two cycles. The first-cycle survey spans from 2007 to 2019, covering a period of twelve years and seven waves. The second cycle began in 2021, with surveys conducted in three waves. KWDI releases the KWMP datasets on its website

2.

The KWMP sample comprises male and female workers holding professional and managerial positions where they oversee at least 100 regular employees (

Lee et al., 2023). In 2021, KWMP began a large-scale questionnaire survey of the work and family life of 3,500 female and 1,511 male managers, including 640 human resource managers from 605 companies (

Lee et al., 2023). The KWMP survey began in 2020 and had been conducted four times annually by 2023. To reinforce the causal relations of the research model, this current study utilizes variables from different years. The FWA variable is from the 2020 KWMP dataset, the work-family conflict variable is from the 2021 KWMP, and the CEO gender equality perceptions and organizational commitment variables are from the 2022 KWMP dataset. As child-rearing responsibilities comprise large shares of family work, parenthood significantly influences work-family relations. Thus, our study’s control manager sample is composed of mothers and fathers. The study sample includes 2,345 mothers and fathers holding managerial positions across 469 companies. The FWA variable is constructed at the organization level, and the other variables (work-family conflict, CEO gender equality perceptions, and organizational commitment) are structured at the individual level. This study uses a multi-level structure to analyze the research model.

3.2. Variables

The KWMP research team conducted literature reviews to generate questionnaire items. An expert counsel then reviewed these items and provided feedback to improve survey quality. Next, the KWMP research team used the expert counsel feedback to revise questionnaire items (

Lee et al., 2023). Some items were drawn from previous studies published in English. Thus, the team translated questionnaire items from English into Korean. The expert counsel and the KWMP research team collaborated to clarify and enhance the understanding of survey items (

Lee et al., 2023).

3.2.1. FWAs

Human resource officers were asked to report whether organizations use FWAs with ‘1’ as ‘use’ and ‘2’ as ‘no use.’ FWAs were measured using three items: 1) flex-time work, 2) alternative work schedules, and 3) homeworking/telecommuting. We dummy-coded each FWA measure as ‘1’ for ‘use’ and ‘0’ for ‘no use’ and summed the three FWA measures to assess use within the organization. We utilize the FWA measures reported by human resource officers in 2020.

3.2.2. Work-Family Conflict

KWMP draws work-family conflict items from

Grzywacz and Marks (

2000). Negative work-family items include four items measured on a five-point Likert-scale: 1) “Your job reduces the effort you can give to activities at home;” 2) “Job worries or problems distract you when you are at home;” 3) “Personal or family worries and problems distract you when you are at work;” and 4) “Stress at home makes you irritable at work.” We averaged work-family conflict to assess the negative work-family balance reported in 2021.

3.2.3. CEO Gender Equality Perceptions

CEO gender equality perception was measured with a five-point Likert scale using four items: 1) “Our CEO champions gender equality in the organization”; 2) “Our CEO treats employees equally regardless of their gender;” 3) “Our CEO trusts employees and perceives them as human capital;” 4) “Our CEO encourages employees to strike a balance between their work and family lives.” We then averaged the CEO gender equality perception items as reported by mother and father managers in 2022.

3.2.4. Organizational Commitment

Organizational commitment items were drawn from

Allen and Meyer (

1990) and

Mowday et al. (

1979) and measured using three items: 1) “I feel as if this organization’s problems are my own;” 2) “I am proud to tell others that I am part of this organization;” and 3) “I think that I can become attached to this organization.” Next, we averaged these three items as reported by mother and father managers in 2022.

3.2.5. Gender

Manager gender is assigned a value of ‘1’ for men and ‘2’ for women. We dummy-coded manager gender as ‘1’ for mother managers and ‘0’ for father managers.

3.2.6. Control Variables

The control variables are the ages and salaries of company managers.

4. Results

We conduct multilevel path analyses to examine the mediation research model. First, we implement descriptive and correlation analyses. Second, we conduct a multilevel path analytic method to analyze the mediating sequential model.

4.1. Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Analyses

Of the 2,345 managers in the sample, 1,593 are mothers and 752 are fathers

3. The average age is 47.64 with a standard deviation of 6.94 (

Table 1). Additionally, the average yearly wage is

$44,564 with a standard deviation of

$14,829. The average values of work-family conflict, CEO gender equality perceptions, and organizational commitment are 2.49, 3.45, and 3.79, respectively. CEO gender equality perceptions and organizational commitment variables are above the moderate levels, and work-family conflict is below. Of the 469 companies, 156 use three FWA types, 95 use two types, 105 use one type, and 113 do not use FWAs. Specifically, 269 companies utilize flex-time work, 259 adopt alternative work schedules, and 235 use a homeworking/telecommuting program.

4.2. Multilevel Path Analyses

Multilevel path analyses were conducted to analyze the mediating sequential relationships among FWAs, work-family conflict, CEO gender equality perceptions, and organizational commitment.

Table 2 presents the statistical results of the multipath analysis regarding the mediation model. Notably, FWAs do not have any influence on work-family conflict (ß=-.01, p >.10). Regarding gender, mother managers show higher levels of work-family conflict than father managers (ß=.18, p=.02). Gender and FWAs significantly interact in influencing work-family conflict (ß=.07, p=.02). FWAs are positively related to CEO gender equality perceptions (ß=.12, p=.00), while gender and FWAs fail to significantly interact when it comes to CEO gender equality (ß=-.06, p>.10). Work-family conflict and gender are negatively related to CEO gender equality perceptions; father managers show increased levels compared to mother managers (work-family conflict: ß=-.14, p=.00; gender: ß=-.17, p=.03). FWAs, gender, the interaction between FWAs and gender, and the work-family conflict variables are not related to organizational commitment (FWAs: ß=-.01, p >.10; gender: ß=.10, p >.10; interactions: ß=-.01, p >.10; work-family conflict: ß=-.02, p >.10). However, CEO gender equality perception is significantly related to organizational commitment (CEO gender equality perception: ß=.38, p=.00).

In sum, FWAs fail to reduce company managers’ work-family conflict. Thus, Hypothesis 1, which examines the effect of FWAs on the work-family conflict of company managers, is not supported. Furthermore, work-family conflict is negatively related to perceptions of CEO gender equality, and these perceptions are positively related to organizational commitment. Therefore, Hypothesis 2 is partially supported, as work-family conflict mediates the relationship between FWAs and CEO gender equality perceptions, and CEO gender equality perceptions promote organizational commitment. The interaction between gender and FWAs is positively related to work-family conflict; however, the interactive effect is not significantly related to CEO gender equality or organizational commitment. Thus, Hypothesis 3, which investigates the moderating role of gender in mediating the relationships among FWAs, work-family conflict, CEO gender equality perceptions, and organizational commitment, is partially supported.

We conducted bootstrapping 500 times to calculate the direct and indirect effects of mediating relations. Regarding the direct and indirect effect of mediating relations for CEO gender equality perceptions, FWAs positively affect CEO gender equality (.17), as the lower limit confidence interval (LLCI) and the upper limit confidence level (ULCI) do not include a “0” value (LLCI: .11 and ULCI: .22). The interaction between FWAs and the gender (-.07) and work-family conflict (-.188) variables negatively affect CEO gender equality perceptions, as a “0” value is not included in the interaction between LLCI and ULCI (interaction -> LLCI: -.14 and ULCI: -.01; work-family conflict -> LLCI: -.23 and ULCI: -.14). FWAs have marginal indirect effects (.009) on CEO gender equality perceptions through work-family conflict, as LLCI is estimated to be -.001. The interaction between gender and FWAs is negatively related to CEO perceptions of gender equality, mediated by work-family conflict (-.02).

Regarding organizational commitment, the interaction between FWAs and gender fail to directly affect organizational commitment, as LLCI and ULCI include a “0” value (LLCI: -.06 and ULCI: .04). The interactive effects of FWAs with gender indirectly affect organizational commitment through changes in CEO gender equality perceptions (FWAs: -.01; interactions: .00), as LLCI and ULCI do not include a “0” value (FWAs -> LLCI: -.02 and ULCI: -.01; interactions -> LLCI: .00 and ULCI: .01). Work-family conflict and CEO gender equality perceptions have negative (-.07) and positive effects (.41) on organizational commitment, as there is no “0” value in the interaction between LLCI and ULCI (work-family conflict -> LLCI: -.10 and ULCI: -.03; CEO gender equality -> LLCI: .38 and ULCI: .44) (

Table 3). Summarizing the direct and negative effects from the mediation model, the interaction between gender and FWAs influences CEO gender equality perceptions, mediated by work-family conflict. The interactive effect also indirectly impacts organizational commitment, mediated by perceptions of CEO gender equality. Work-family conflict negatively and indirectly affects organizational commitment through CEO gender equality perceptions. Calculating the indirect effects supports the serial mediating relations of FWAs, gender, work-family conflict, CEO gender equality perceptions, and organizational commitment.

4.3. Interaction Figures

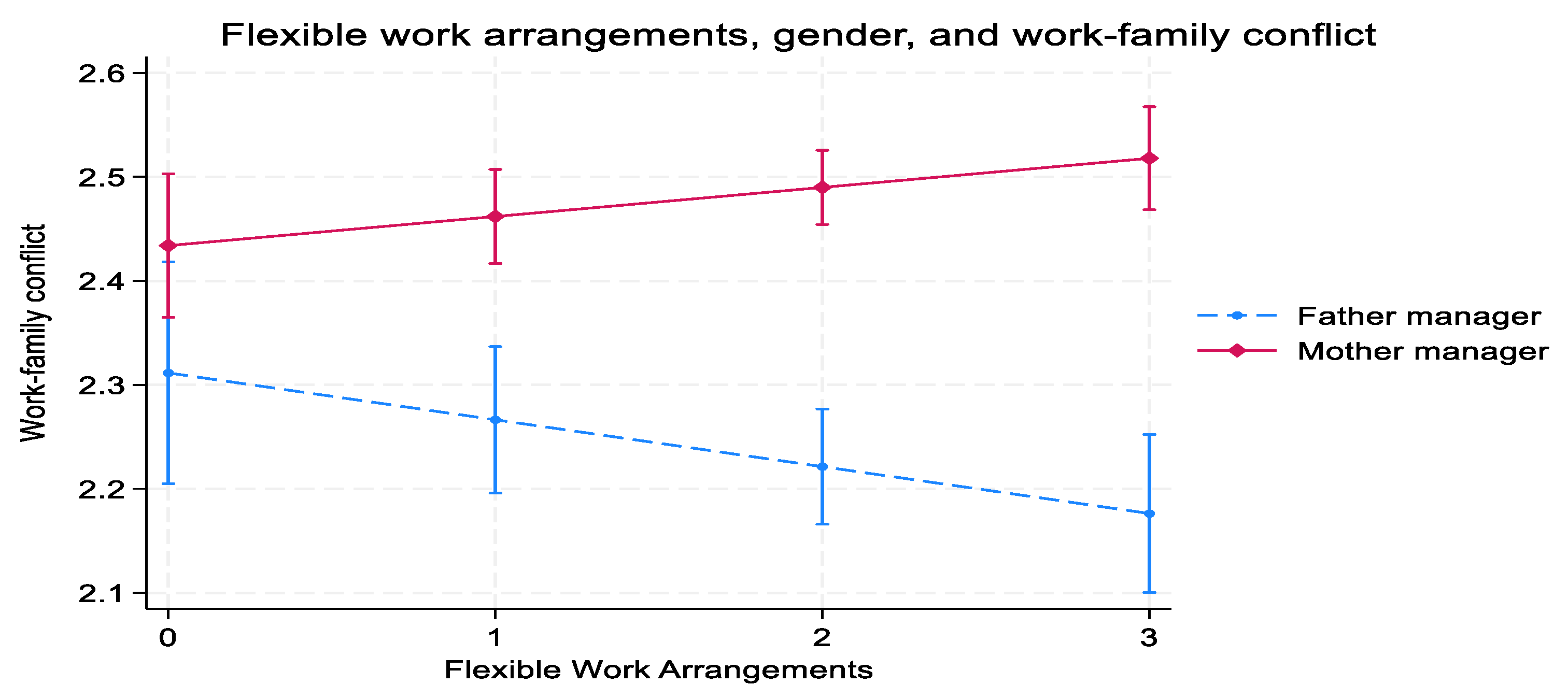

We graph the interaction effects between FWAs and gender on work-family conflict (

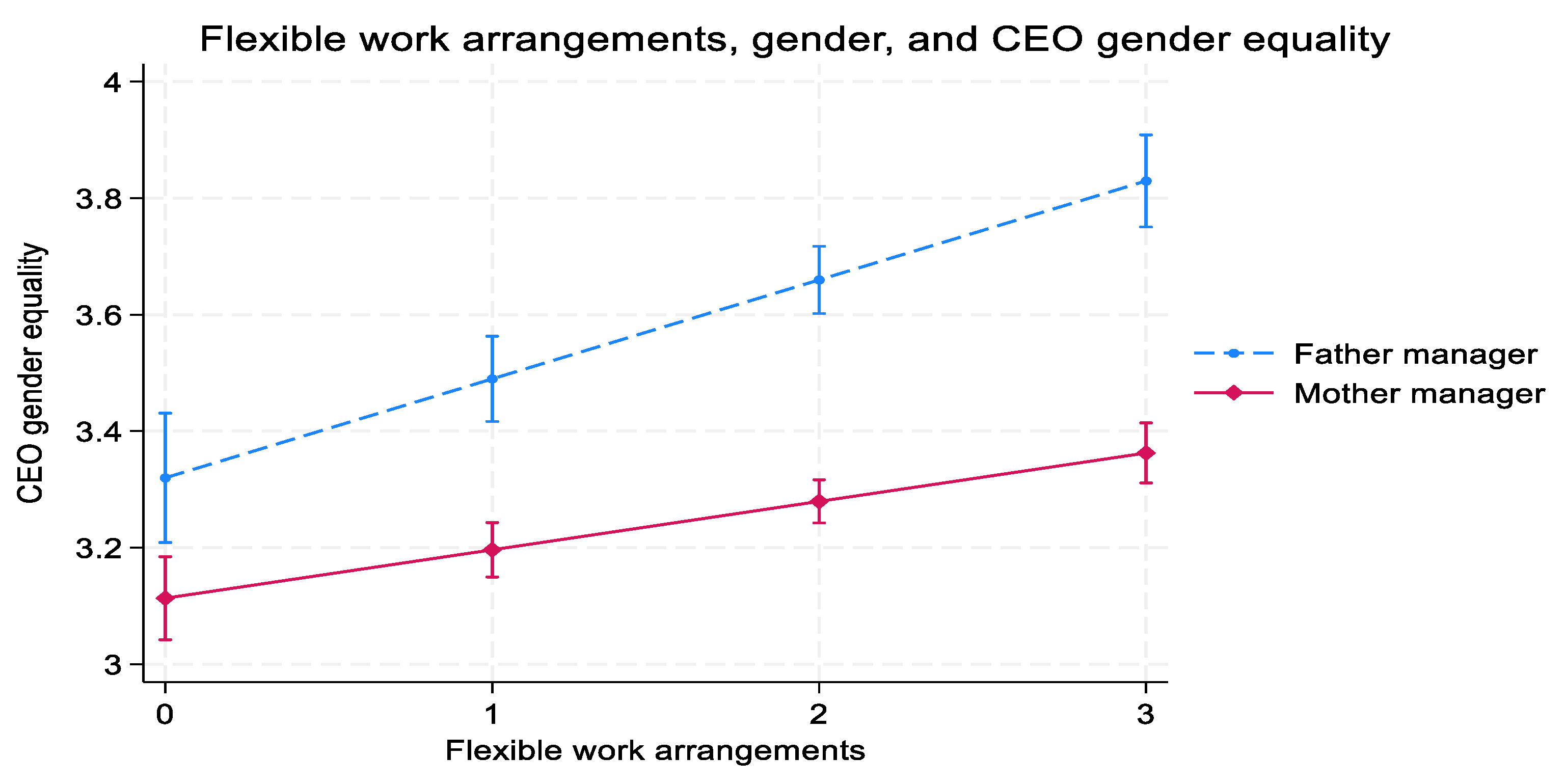

Figure 2), CEO gender equality perceptions (

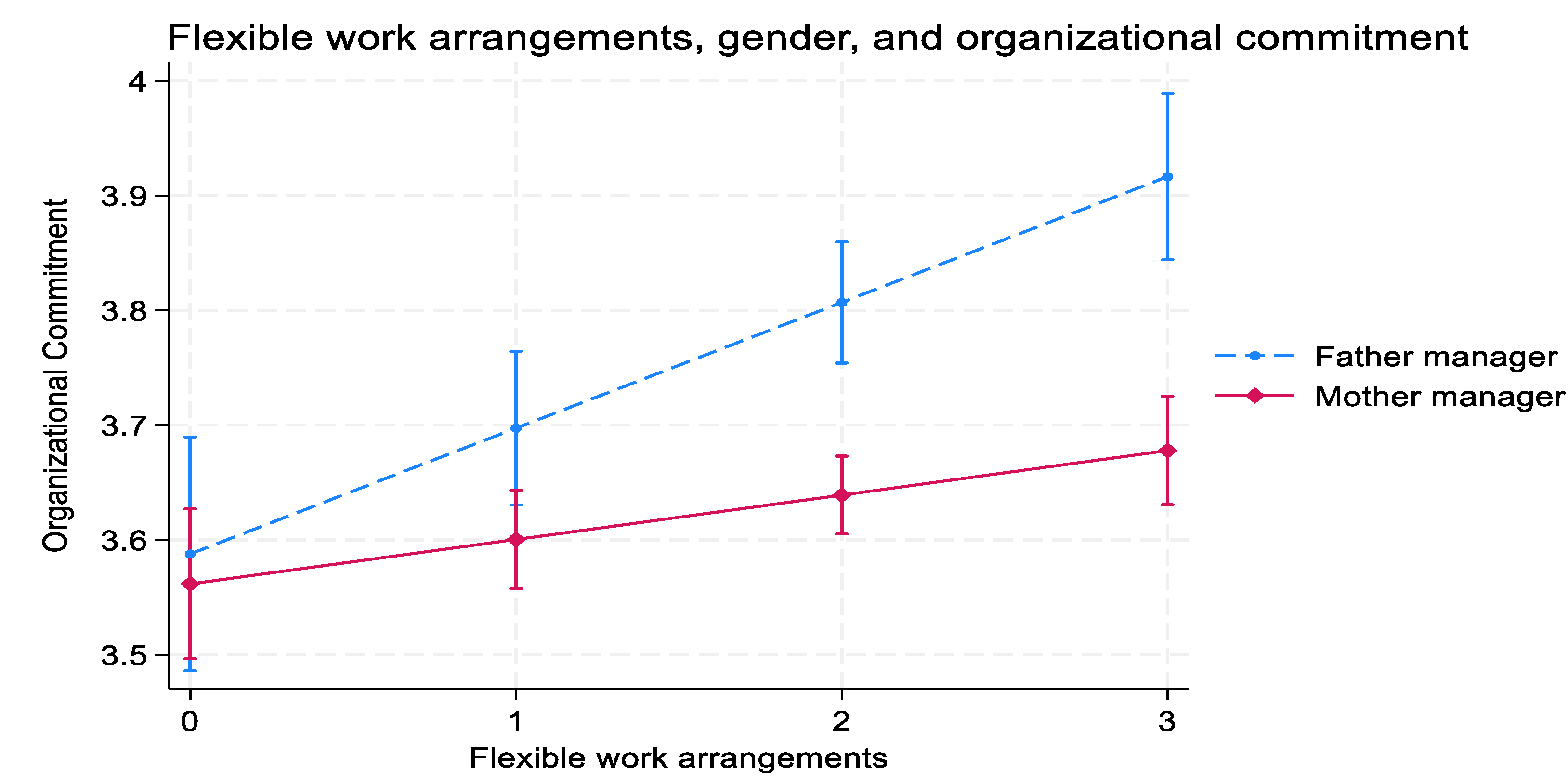

Figure 3), and organizational commitment (

Figure 4).

Figure 2 presents the interactions between gender and FWAs. Father managers show reduced levels of work-family conflict when organizations make significant FWAs. In contrast, the work-family conflict of mother managers increases in correlation with FWA use. These findings suggest that father managers receive more benefits from FWAs than mother managers.

Figure 3 illustrates the relationship between gender and FWAs in influencing CEO gender equality. It reveals that the slope of father managers regarding FWAs and CEO gender equality increases more than that of mother managers as FWAs increase.

Figure 4 presents the interactive effects of gender and FWAs on organizational commitment, particularly when corporations are likelier to utilize FWAs. It also shows that father managers show greater organizational commitment more than mother managers. The graph of the impact of the interaction between gender and FWAs on CEO gender equality indicates that FWAs foster more positive perceptions of CEOs and organizational commitment for father managers than mother managers.

4.4. Statistical Analyses Summary

Gender plays a moderating role in the relationship between FWAs and work-family conflict. Father managers experience less conflict while mother managers perceive more as FWAs increase. This conflict is negatively related to CEO gender equality perceptions, which in turn, promotes organizational commitment of father managers. The mediating model presents significant indirect effects. Particularly, the interaction between FWAs and gender indirectly affects CEO gender equality through changes in work-family conflict. Work-family conflict also indirectly affects organizational commitment, mediated by CEO gender equality perceptions. Therefore, FWAs, work-family conflict, CEO gender equality perceptions, and organizational commitment are sequentially linked, with work-family conflict and CEO gender equality perceptions playing mediating roles. Gender significantly affects the sequential relations of the mediation model: father managers are eligible for FWA benefits, while FWAs increase work-family conflict for mother managers. To increase the effectiveness of FWAs, it is crucial to examine gender roles to determine whether the permeability of the work-family boundary mitigates or exacerbates work-family conflict.

5. Discussion

This current study examines the mediating model of FWAs, work-family conflict, CEO gender equality perceptions, and organizational commitment. Multilevel path analyses reveal that FWAs mitigate work-family conflict, thereby enhancing perceptions of CEO gender equality and organizational commitment. Furthermore, gender significantly affects the mediating relations among FWAs, work-family conflict, CEO gender equality perceptions, and organizational commitment. Specifically, FWAs are more beneficial to father managers than mother managers as they allow fathers to mitigate work-family conflict, and promote CEO gender equality perceptions and organizational commitment.

The use of FWAs can be justified using psychological social exchange theory: when FWAs are available to company managers, these managers reciprocate the spatial and temporal workplace flexibility promoted through FWAs by enhancing their work-related attitudes and perceptions (

Bayazit & Bayazit, 2019). However, concerns are raised about the costs incurred by designing and implementing FWAs. As FWAs increase the number of choices and decisions for company managers, they impose additional burdens on work and family relations (

Allen et al., 2013). Nevertheless, the findings of this study reveal that flexibility in the workplace increases self-control over work schedule, location, and methods. FWAs can be a valuable resource for supporting company managers in exerting more effective control over their allocation of time, energy, and attention to both their work and family domains. Specifically, FWAs are planned and implemented based on a CEO’s authority over HR policies and programs. Therefore, they can be an effective tool for organizations in promoting positive perceptions of CEOs by facilitating psychological exchange relations with company managers.

CEO perceptions of gender equality and organizational commitment are enhanced as FWAs decrease work-family conflict. The mutual interference between the work and family domains exerts pressure on work-family compatibility, resulting in skeptical reactions toward CEOs and organizations. To promote work-related attitudes, organizations must use FWAs to allow family boundaries to be permeable and flexible. Facilitating work-family transition using FWAs increases the recognition of a CEO’s role in adopting and extending work-family benefit programs and policies. Further, viewing a CEO’s role as one who is actively involved in shaping and developing gender equality environments is pivotal to reinforcing parent managers’ attachment to organizations. The role of top managers should be considered a crucial driver of organizational policies that motivate parent managers to continue working and strengthen their connections with the organization. The CEO must be actively involved in formulating and executing work-family flexibility policies and programs to promote positive attitudes among company managers (

Joo et al., 2023).

Interestingly, FWAs target the work-family relations of mother managers by transforming the traditional division of labor and affording them more resources to fulfill family demands and responsibilities. However, the statistical results of this study show that, contrary to their original intentions, FWA benefits are more readily available to fathers than mothers. This study suggests that traditional gender assumptions persist in the workplace. Family devotion often prevents mothers from maintaining their career tracks, as traditional gender role beliefs urge them to engage in intensive parenting, causing them to forsake the idealized worker role and be pushed out due to overwork (

Oh & Mun, 2022;

Shin & Kim, 2023). Work-family benefit programs are offered and allocated equally between father and mother managers (

Oh & Mun, 2022). Related policies encourage father and mother managers to equally divide parenting roles and household labor. However, as mothers often have more family commitments, equal promotion policies may pose disadvantages to their pursuit and development of career paths (

Sievers, 2023). Particularly, mothers are stereotyped as taking advantage of FWAs to satisfy expectations about traditional gendered norms, which may hinder them from work achievements (

Cha, 2010). Contrary to fathers, mothers managers show higher levels of work-family conflict when companies increase FWAs, as they are vulnerable to pressures from satisfying work and family demands simultaneously. Therefore, for mother managers, increased FWAs can exacerbate stress due to the incompatible nature of the work and family domains.

To substantiate the argument against FWAs’ effectiveness for mother managers, t-statistics were implemented to compare genders regarding FWAs. KWMP surveyed participants regarding the ease of FWA use and the associated career disadvantages (

Table A1 in

Appendix A).

Table A2 showed the t-statistics results regarding gender differences in ease of FWA use and career disadvantages. Father managers presented a value of 1.856 for “ease of FWA use” and 1.804 for “career disadvantages from FWA use.” Conversely, mother managers reported a value of 1.775 for “ease of FWA use” and 2.064 for “career disadvantages from FWA use” (

Table A2 in

Appendix A). The results show a significant gender difference regarding “ease of FWA use” (t-value: 3.089 in

Table A2,

Appendix A) and career disadvantages from FWA use (t-value: 5.939 in

Table A2,

Appendix A). The analysis of the T-statistics revealed that mothers confront challenges in utilizing FWAs for realizing a work-family balance. As mothers fear career disadvantages due to FWAs, they perceive obstacles to utilizing FWAs. Thus, FWAs cannot provide sufficient support for mothers’ work-family relations as expected.

To address this, companies must design and execute FWAs to promote the work-family balance of mother managers. Furthermore, the active family involvement of father managers can improve the quality of family life (

Holmes et al., 2020). When fathers take advantage of FWAs, they are likelier to be actively involved in their family. Implementing FWAs can offer fathers the potential to resolve the conflicting demands of work and family, thereby contributing to a better balance between these domains. To align with the original intentions of planning and implementing FWAs, organizations should motivate and support mothers in breaking free from traditional gender stereotypes to advance their career paths (

Cha, 2010).

6. Contributions and Implications

We contribute to the existing literature by addressing several questions about the consequences of FWAs. First, this study develops a serial mediation model that extends the scope of exploring FWA effectiveness by examining gender roles, work-family conflict, CEO gender equality perceptions, and organizational commitment. Our model examines the extent to which father and mother managers perceive differences in the mediating processes of work-family conflict and CEO gender equity perceptions. It also examines the relationship between CEO gender equity perceptions and FWAs as well as organizational commitment. Articulating the process through which FWAs positively impact individuals and organizations, we provide supporting arguments for the use of FWAs. The findings of this study show that FWAs alleviate work-family conflict, enhance positive perceptions of CEOs’ gender equality policies and programs, and ultimately increase organizational commitment. These results align with resource theory (

Allen et al., 2013), positing that individuals gain greater power and influence in social contexts by accessing and controlling more resources.

Second, our study sample consists of managers who are parents. As parenthood involves childbearing responsibilities, it demonstrates significant differences in FWA consequences compared to those without children. Our study sample, composed of parents, can exert controls over variables that significantly influence work-family relations associated with the use of FWAs.

Third, we adopt a dataset spanning three years and a multilevel analysis method to advance FWA research. This study’s dataset draws upon the Korean Women Panel (KWMP) dataset, which covers 2022 to 2024, and includes variables selected from each year. Compared to cross-sectional studies, longitudinal designs provide a more rigorous framework for identifying the causal consequences of FWAs. In addition, conducting a multilevel analysis more accurately accounts for within- and between-organization variances concerning FWAs and the related individual perceptions and attitudes.

Testing the mediating model reveals how FWAs support managers in balancing work and family demands, motivating them to develop positive attitudes toward their organizations. Identifying the gender difference in the relationship patterns provides a better understanding of the beneficial effects of FWAs. Advances in understanding the consequences of FWAs can help organizations establish and develop a supportive environment for managers to integrate work and family domains, refining human resource policies and practices.

7. Limitations

This current study adopts a multilevel, multiyear structure and a sequential mediation model to extend the scope of research on FWAs and the related work-family conflict. Despite its strengths, we should consider certain limitations to better interpret the study results. First, the study sample is constrained to mothers and fathers holding professional and managerial positions. Their average annual wages amount to $41,763 and $49,496, respectively, which are significantly higher than the average annual wages of workers in Korea. The working environments of the study sample are also superior to those of other workplaces. Furthermore, there are many unmarried or married workers without children. Thus, it is necessary to consider the sample characteristics (married workers with children who hold professional and managerial positions) when understanding and applying the study results to construct and establish effective managerial programs and practices.

Second, the FWA variable is constructed using the sum of three dummy variables, flex-time work, alternative work schedules, and homeworking/telecommuting, to measure whether organizations use these FWA types. However, questions can be raised regarding how much dummy measures can appropriately assess FWA use. Thus, future studies should use measures that evaluate the extent to which organizations adopt and utilize FWAs.

Third, the work-family conflict measure reflects the negative aspects of work-family relations. However, there is also a positive side to promoting work-family balance, as it may extend the implications of work-family relations when considering the positive and negative aspects of work-family.

Fourth, the KWMP survey uses four items to measure work-family conflict and three to assess organizational commitment, drawing some items from existing literature. As the survey is sponsored by the Korean government, policies and regulations make limitations about the financial resources available for generating, constructing, and utilizing questionnaire items. Therefore, the survey cannot fully capture the entirety of work-family conflict and organizational commitment measures. Thus, future studies should use from existing literature to construct variables that operationalize study concepts rather than relying on the KWMP surveys.

Fifth, there is a bidirectional nature to the work-family conflict. However, this study does not delineate the distinct directions of work-family conflict. In the future, it may be useful to consider the directions of this conflict (i.e., conflict from work to family or from family to work) in terms of identifying the determinants of FWA effectiveness.

Sixth, asymmetry exists in the sample size of mother and father managers, as the sample size for mothers is 1,593 and 752 for fathers, raising questions about the appropriateness of the sample size in terms of gender comparison. Future studies should ensure symmetry in the sample size by gender.

Finally, the KWMP survey covered Korean managers in Korean corporations. Thus, it is necessary to consider the uniqueness of the characteristics of Korean culture to understand and interpret sequential models of FWAs use, work-family conflict, CEO gender equality perceptions, and organizational commitment.

8. Conclusions

The study findings reveal that FWAs shape and establish work-family boundaries, allowing them to be permeable and flexible, which alleviates work-family conflict and fosters positive attitudes toward CEOs and organizations. The study framework advances the knowledge that guides the process through which FWAs positively impact managers. The statistical results show that FWA effectiveness is more prominent for father managers, as they are less vulnerable to gendered norms regarding work and family life. Contrary to expectations, FWAs make a limited contribution for mother managers. Mothers are often normatively pressured to devote themselves to their families and neglect their career paths. Thus, FWAs can reinforce gender stereotypes about mother managers prioritizing family life over company work. Mothers are less motivated to use FWAs as they fear career disadvantages from gender-stereotyped assumptions about work and family life. In contrast, FWA benefits are more accessible to fathers, as they are less constrained by stereotypes about work-family relations from FWAs. Thus, it is pivotal to accommodate gender roles to promote FWA effectiveness. We hope that this study provides implications for FWA planning and implementation to enhance the acquisition, retention, and development of human capital by alleviating work and family incompatibility.

Author Contributions

All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from Statistics Korea on October 8th, 2018 (approval number 154010) (kostat.go.kr/anse/).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Survey items about the ease of FWA use and its associated career disadvantages.

Table A1.

Survey items about the ease of FWA use and its associated career disadvantages.

| FWAs |

Ease of use |

Career disadvantages |

| Very unlikely |

Unlikely |

Neutral |

Likely |

Very

likely |

Very unlikely |

unlikely |

Neutral |

Likely |

Very

likely |

| Flex-time work |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Alternative work schedules |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Homeworking |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Telecommuting |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Table A2.

Gender differences in the ease of FWA use and its associated career disadvantages.

Table A2.

Gender differences in the ease of FWA use and its associated career disadvantages.

| Variables |

Gender |

Average |

Standard error |

t-value |

| Easy to use |

Mother1

|

1.775 |

.015 |

3.089 |

| Father2

|

1.856 |

.020 |

| Total3

|

1.829 |

.012 |

Career

disadvantage |

Mother1

|

2.064 |

.026 |

5.939 |

| Father2

|

1.804 |

.032 |

| Total3

|

1.977 |

.021 |

References

- Adams, A., and A. Schwarz. 2024. Blurred lines. Gendered implications of digitally extended availability and work demands on work-family conflict for parents working from home. Community, Work & Family 27, 5: 674–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allard, K., L. Haas, and C. P. Hwang. 2011. Family-supportive organizational culture and fathers’ experiences of work-family conflict in Sweden. Gender, Work and Organization 18, 2: 939–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, T. D., R. C. Johnson, K. M. Kiburz, and K. M. Shockley. 2013. Work-family conflict and flexible work arrangements: Deconstructing flexibility. Personnel Psychology 66, 2: 345–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, N. J., and J. P. Meyer. 1990. The measurement and antecedents of affective, continuance, and normative commitment to the organization. Journal of Occupational Psychology 63, 1: 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayazit, Z. E., and M. Bayazit. 2019. How do flexible work arrangements alleviate work-family conflict? The roles of flexibility ideals and family-supportive cultures. The International Journal of Human Resource Management 30, 3: 405–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cha, Y. 2010. Reinforcing separate spheres: The effect of spousal overwork on men’s and women’s employment in dual-earner households. American Sociological Review 75, 2: 303–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grzywacz, J. G., and N. F. Marks. 2000. Reconceptualizing the work-family interface: An ecological perspective on the correlates of positive and negative spillover between work and family. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology 5, 1: 111–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, E. K., R. J. Petts, C. R. Thomas, N. L. Robbins, and T. Henry. 2020. Do workplace characteristics moderate the effects of attitudes on father warmth and engagement? Journal of Family Psychology 34, 7: 867–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoobler, J. M., S. J. Wayne, and G. Lemmon. 2009. Bosses’ perceptions of family-work conflict and women’s promotability: Glass ceiling effects. Academy of Management Journal 52, 5: 939–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huffman, A. H., K. J. Olson, T. C. O’Gara, Jr., and E. B. King. 2014. Gender role beliefs and fathers’ work-family conflict. Journal of Managerial Psychology 29, 7: 774–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joo, J., H. S. Kim, S. G. Song, Y. J. Ro, and J. H. Song. 2024. Performance-oriented HR and career development of women managers: The mediation of self-leadership and the moderated mediation of supervisor’s gender equality. European Journal of Training and Development 48, 7/8: 786–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kossek, E. E., M. B. Perrigino, and B. A. Lautsch. 2023. Work-life flexibility policies from a boundary control and implementation perspective: A review and research framework. Journal of Management 49, 6: 2062–2108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S-H., E-J. Kim, H-J. Bae, M-H. Lee, S-Y. Kwon, W-R. Noh, J-E. Lee, S-Y. Kwon, W-R. Noh, J-E. Lee, K-T. Kim, Y-B. Kim, and G-S. Choi. 2023. The 2022 Korean Women Manager Panel Survey. Korean Women’s Development Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Mowday, R. T., R. M. Steers, and L. W. Porter. 1979. The measurement of organizational commitment. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology 14, 2: 224–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, E., and E. Mun. 2022. Compensatory work devotion: How a culture of overwork shapes women’s parental leave in South Korea. Gender & Society 36, 4: 552–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ongaki, J. 2019. An examination of the relationship between flexible work arrangements, work-family conflict, organizational commitment, and job performance. Management 23, 2: 169–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shockley, K.M., and N. Singla. 2011. Reconsidering work-family interactions and satisfaction: A meta-analysis. Journal of Management 37, 3: 861–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R., Y. Zhang, M. M. Wan, and N. A. Fouad. 2018. Why do women engineers leave the engineering profession? The roles of work-family conflict, occupational commitment, and perceived organizational support. Human Resource Management 57, 4: 901–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistics Korea. 2024. Employment status of dual-income households and single-person households by region in the second half of 2023. Available online: https://kostat.go.kr/board.es?mid=a10301010000&bid=211&act=view&list_no=431387.

- Sublet, L.W., L.M. Penney, and C. Bok. 2024. When workplace family-support is misallocated: Effects of value congruence and fairness perceptions on supervisor family-support. Journal of Management & Organization 30: 1067–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, H., and S. Kim. 2023. Motherhood and mentoring networks: The unequal impact of overwork on women’s workplace mentoring networks. Sociological Perspectives 66, 3: 434–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sievers, T. 2023. Enabled but not transformed-narratives on parent involvement among first-time mothers and fathers in Germany in the context of parental leave policy design. Community, Work & Family 26, 3: 356–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vadvilavicius, T., and A. Stelmokiene. 2024. Employees’ work-family enrichment in leadership context: Systematic review and meta-analytical investigation. Business Theory & Practice 25, 2: 574–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wayne, J. H., W. J. Casper, R. A. Matthews, and T. D. Allen. 2013. Family-supportive organization perceptions and organizational commitment: The mediating role of work-family conflict and enrichment and partner attitudes. Journal of Applied Psychology 98, 4: 606–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| 1 |

KWMP is a panel dataset that longitudinally tracks the career paths of both female and male managers. Its primary objective is to examine the representation of women in management positions and assess the current state of gender diversity in Korean corporations. By collecting a wide range of information, including demographic characteristics, workplace data, and family-related variables, from male and female managers, KWMP enables researchers to conduct gender-based comparisons of managerial careers. |

| 2 |

|

| 3 |

Regarding the number of children, 781 managers have one child (33.3%), 1,376 have two children (58.68%), 176 have three children (7.51%), and 12 have four children (0.5%). |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).