Submitted:

22 July 2025

Posted:

22 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Method

2.1. Subjects

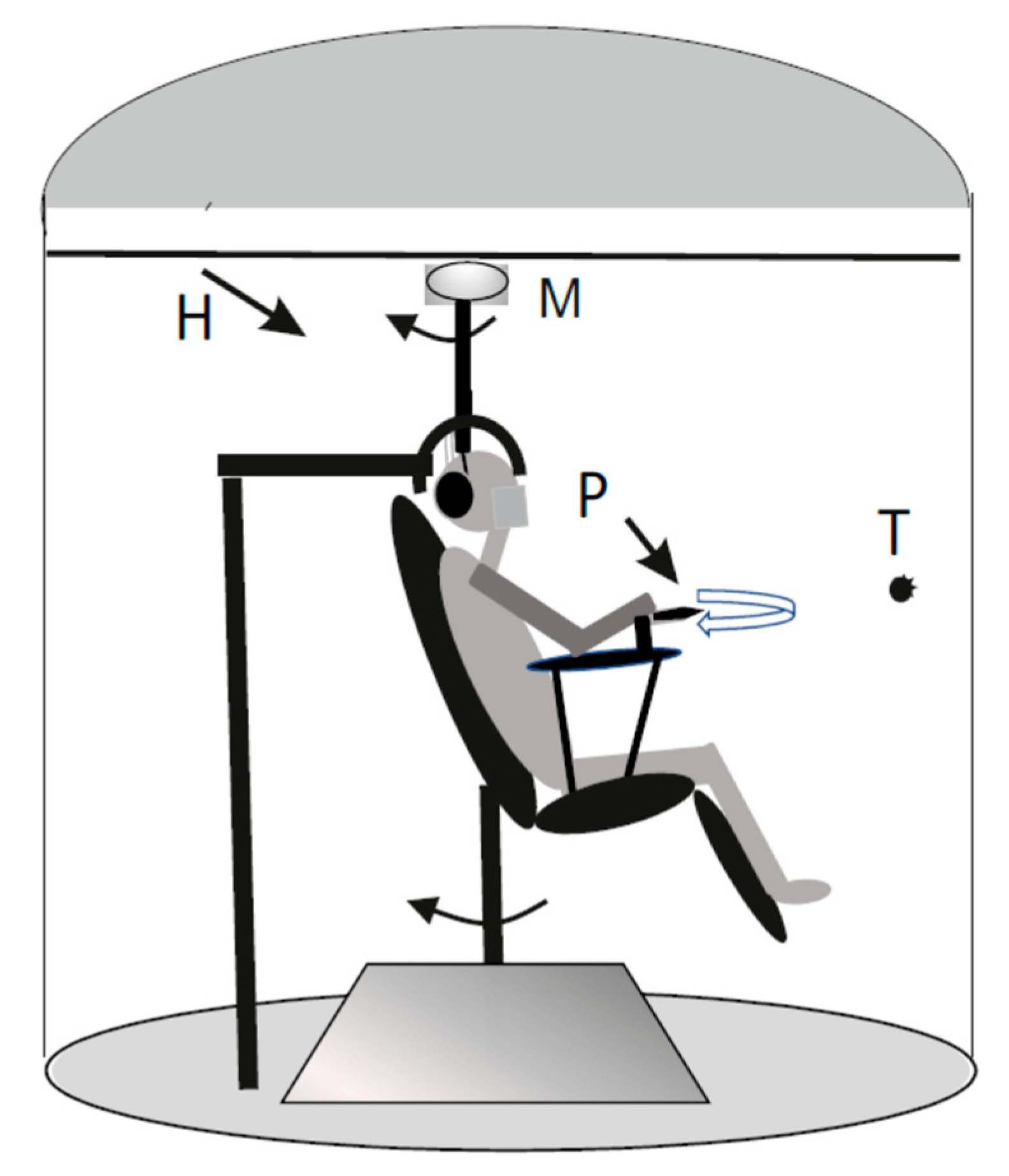

2.2. Experimental Setting

2.2.1. Neck Proprioceptive and Vestibular Stimulation

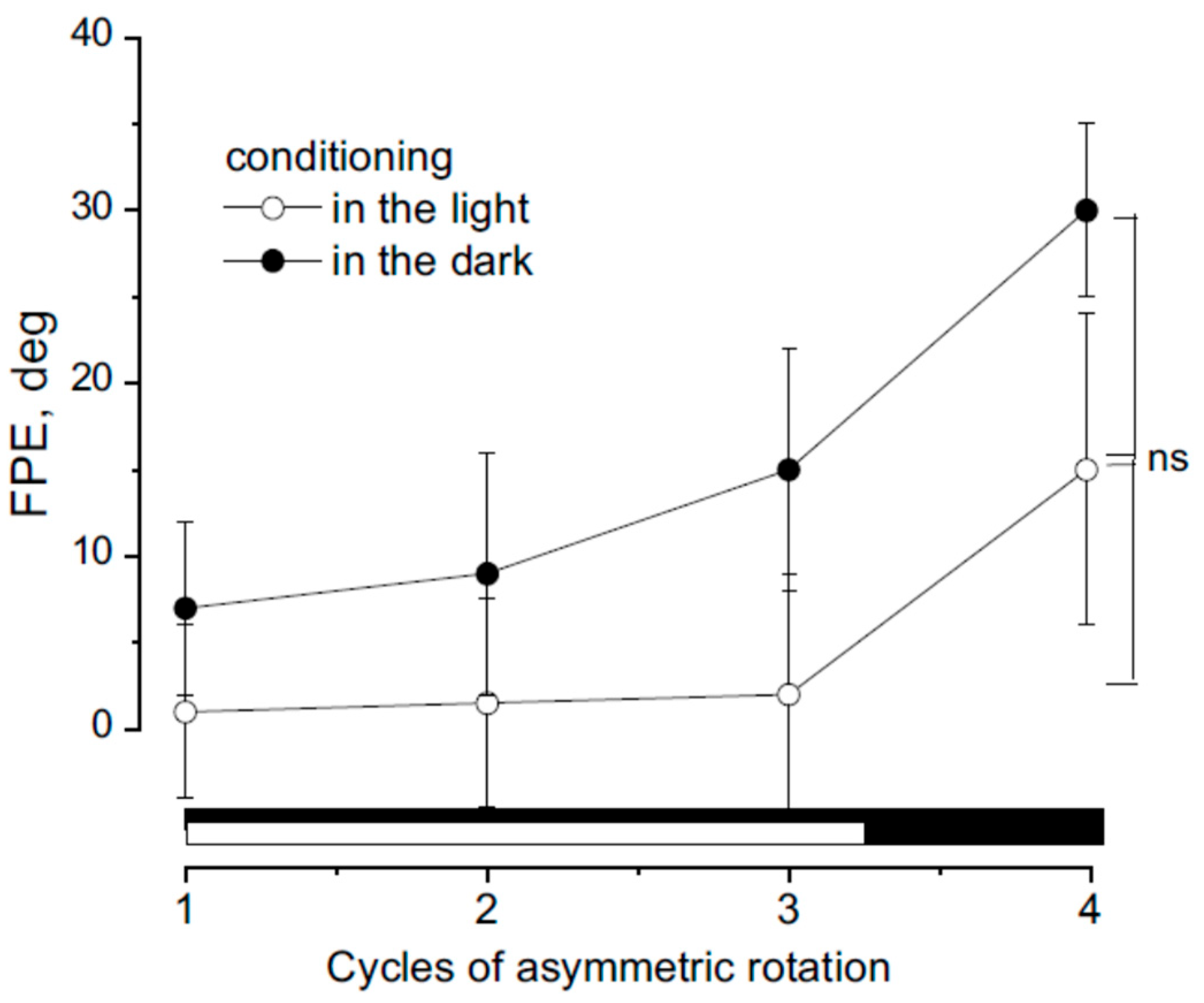

2.2.2. Asymmetric Rotation Protocol

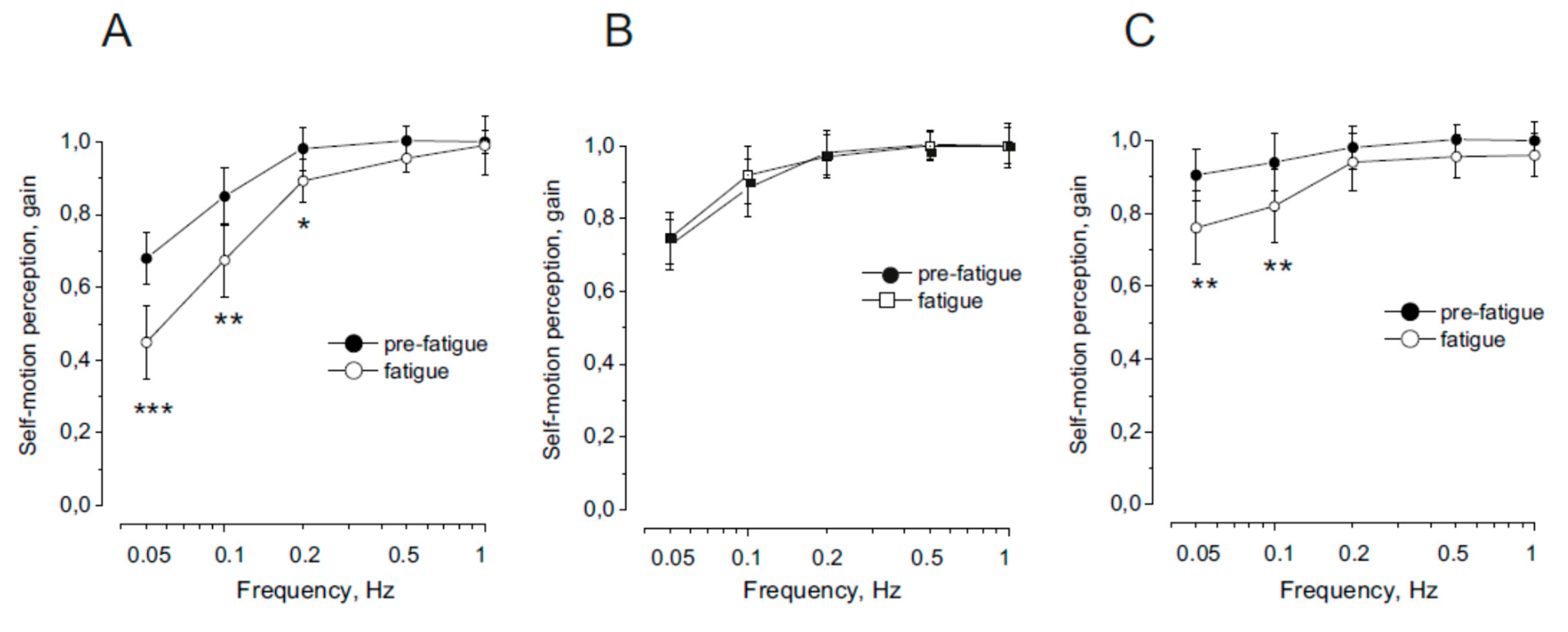

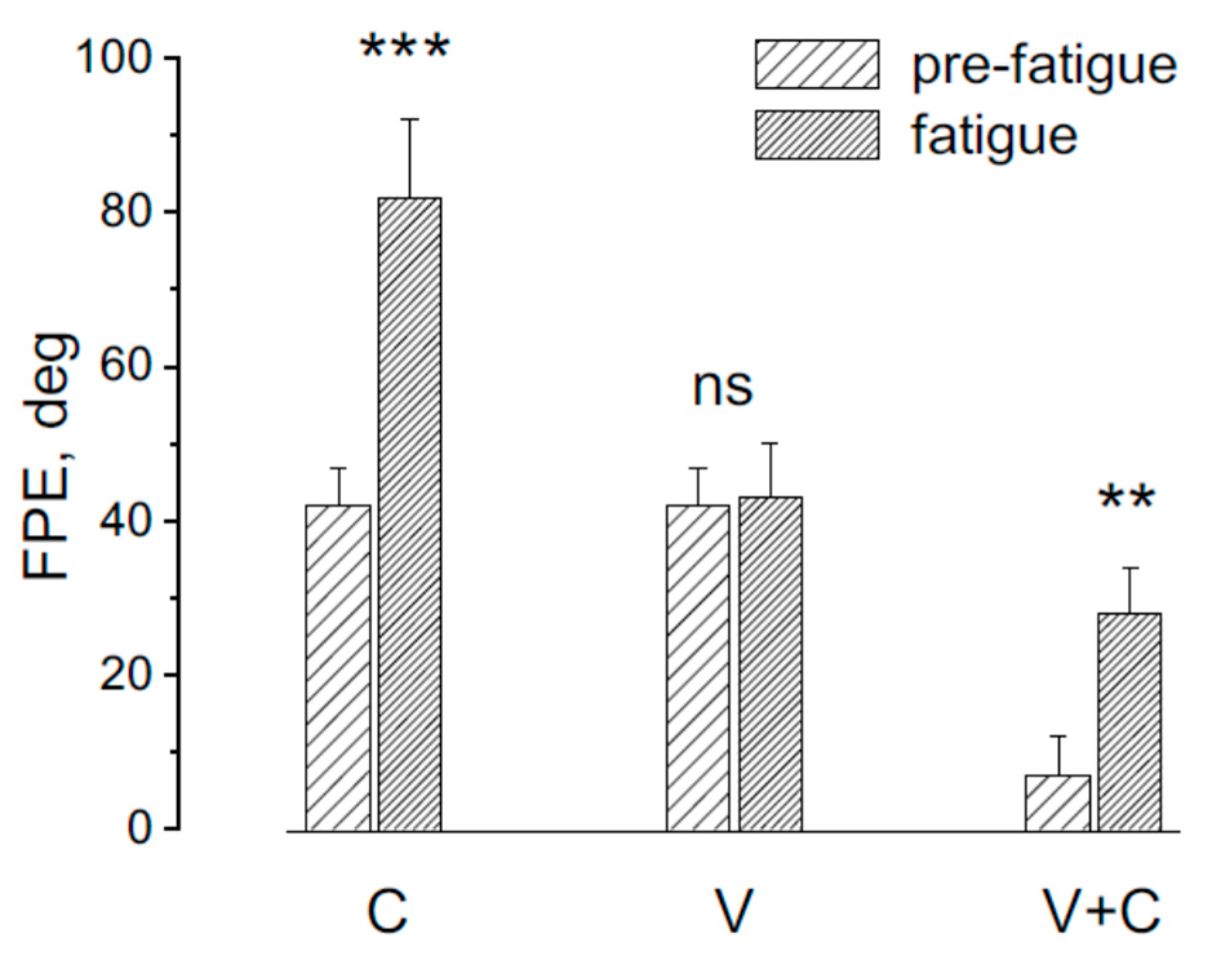

2.2.3. Self-Motion Perception Recordings

2.2.4. Neck Extensor Muscle Fatigue

2.2.5. Experimental Protocol

2.2.6. Acquisition and Analysis of the Pointer Data

3. Results

4. Discussion

References

- Schweigart G., Heimbrand S., Mergner T., Becker W Role of neck input for the perception of horizontal head and trunk rotation in patients with loss of vestibular function. Exp. Brain. Res. 1993, 95, 533–546.

- Schweigart G., Chien R.D., Mergner T. Neck proprioception compensates for age-related deterioration of vestibular self-motion perception. Exp. Brain Res. 2002, 147, 89–97. [CrossRef]

- Bottini G., Karnath H.O., Vallar G., Sterzi R., Frith C.D., Frackowiak R.S., Paulesu E. Cerebral representations for egocentric space: functional anatomical evidence from caloric vestibular stimulation and neck vibration. Brain 2001, 124, 1182–1196. [CrossRef]

- Bove M., Courtine G., Schieppati M. Neck muscle vibration and spatial orientation during stepping in place in humans. J Neurophysiol. 2002, 88, 2232–2241.

- Pettorossi V.E., Schieppati M. Neck proprioception shapes body orientation and perception of motion. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2014, 4(8), 895. [CrossRef]

- Cullen K.E. The neural encoding of self-generated and externally applied movement: implications for the perception of self-motion and spatial memory. Front. Integr. Neurosci. 2014, 7, 108. [CrossRef]

- Jamal K., Leplaideur S., Leblanche F., Moulinet Raillon A., Honoré T., Bonan I. The effects of neck muscle vibration on postural orientation and spatial perception: a systematic review. Neuro physiol. Clin. 2020, 50, 227–267. [CrossRef]

- Gosselin G., Rassoulian H., Brown I. Effects of neck extensor muscles fatigue on balance. Clin. Biomech. 2004, 19, 473–479. [CrossRef]

- Gosselin G., Fagan M.J. Effects of cervical muscle fatigue on the perception of the subjective vertical and horizontal. Springerplus 2014, 8(3),78. [CrossRef]

- Zabihhosseinian M., Holmes M.W., Murphy B Neck muscle fatigue alters upper limb proprioception. Exp. Brain Res. 2015, 233, 1663–1675. [CrossRef]

- Schieppati M., Nardone A., Schmid M. Neck muscle fatigue affects postural control in man. Neurosci. 2003, 121, 277–285.

- Baccini, M., Risaliti, I., Rinaldi, L.A., Paci, M. Head position and neck muscle fatigue: effects on postural stability. Gait Posture 2006, 24, S9–S10. [CrossRef]

- Schmid M., Schieppati M. Neck muscle fatigue and spatial orientation during stepping in place in humans. J. Appl. Physiol.2005, 99, 141–153. [CrossRef]

- Schmid M., Schieppati M., Pozzo T. Effect of fatigue on the precision of a whole-body pointing task. Neurosci. 2006, 139, 909–920.

- Botti, F.M., Guardabassi, M., Ferraresi, A., Faralli, M., Filippi, G.M., Marcelli, V., Occhigrossi, C., Pettorossi, V.E. Neck muscle fatigue disrupts self-motion perception. 2025, Exp. Brain Res. 233, 1663–1675. [CrossRef]

- Guardabassi M., Botti F.M., Rodio A., Fattorini L.,Filippi G.M., Ferraresi A., Occhigrossi C., Pettorossi V.E. Prolonged neck proprioceptive vibratory stimulation prevents the self-motion misperception induced by neck muscle fatigue: immediate and sustained effects. Exp. Brain. Res. 2025, 243, 162. [CrossRef]

- Brunetti O., Della Torre G., Lucchi M.L., Chiocchetti R., Bortolami R., Pettorossi V.E. Inhibition of muscle spindle afferent activity during masseter muscle fatigue in the rat. Exp. Brain Res. 2003, 152, 251 262. [CrossRef]

- Pettorossi V.E., Della Torre G., Bortolami R., Brunetti O. The role of capsaicin-sensitive muscle afferents in fatigue-induced modulation of the monosynaptic reflex in the rat. J. Physiol. 2004, 515, 599–607. [CrossRef]

- Skinner H.B., Wyatt M.P., Hodgdon J.A. Effects of fatigue on joint position sense of the knee. J. Orthop. Res. 1986, 4, 112–118.

- Shape M.H., Miles T.S. Position sense at the elbow after fatiguing contractions. Exp. Brain Res. 1993, 94, 179–182.

- Garland S.J., Kaufman M.P. Role of muscle afferents in the inhibition of motoneurons during fatigue. In:. Fatigue neural and muscular mechanisms. Adv. in Exp. Med. and Biol.; Gandevia S.C., Enoka R.M., McComas A.J., Stuart D.G., Thomas C.K. Eds.; Plenum Press, New York and London, 1995,Volume 384, pp 271–278.

- Gandevia S.C., Enoka R.M., McComas A.J., Stuart D.G., Thomas C.K. Fatigue neural and muscular mechanisms. Adv. in Exp. Med. and Biol., vol 384. Plenum Press, New York and London, 1995.

- Hagbarth K.E., Macefield V.G. The fusimotor system. Its role in fatigue. In:. Fatigue neural and muscular mechanisms. Adv. in Exp. Med. and Biol.; Gandevia S.C., Enoka R.M., McComas A.J., Stuart D.G., Thomas C.K. Eds.; Plenum Press, New York and London, 1995,Volume 384, pp 259–270 pp 259–270.

- Lattanzio P.J., Petrella R.J., Sproule J.R., Fowler P.J. Effects of fatigue on knee proprioception. Clin. J. Sports Med. 1997, 7, 22–27.

- Pedersen J.M., Ljubislavlevic M., Bergenheim M., Johansson H. Alterations in information transmission in ensemble of primary muscle spindle afferents after muscle fatigue in heteronymous muscle. Neurosci. 1998, 84, 953–959.

- Pedersen J.M., Lonn J., Hellstrom F., Djupsjobacka M., Johansson H. Localised muscle fatigue decreases the acuity of the movement sense in the human shoulder. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 1999, 31, 1047–1052.

- Forestier N., Teasdale N., Nougier V. Alteration of the position sense at the ankle induced by muscular fatigue in humans. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2002, 34, 117–122. [CrossRef]

- Hunter S.K., Duchateau J., Enoka R.M. Muscle fatigue and the mechanisms of task failure. Exerc. Sport Sci. Rev. 2004, 32, 44–49.

- Miura K., Ishibashi Y., Tsuda E., Okamura Y., Otsuka H., Toh S. The effect of local and general fatigue on knee proprioception. J. Arthrosc. Relat. Surg. 2004, 20, 414–418.

- Proske U., Gandevia S.C. Kinaesthetic Senses. J. Physiol. 2009, 587, 4139–4146.

- Proske U., Gandevia S.C. The proprioceptive senses: their roles in signaling body shape, body position and movement, and muscular force. Physiol. Rev. 2012, 92(4), 1651–1697.

- Abd-Elfattah, H.M., Abdelazeim, F.H., Elshennawy, S. Physical and cognitive consequences of fatigue: a review. J. Adv. Res. 2015, 6, 351–358.

- Proske U. Exercise, fatigue and proprioception: a retrospective. Exp. Brain. Res. 2019, 237, 2447–2459. [CrossRef]

- Proske U., Allen T.J. The neural basis of the senses of effort, force and heaviness. Exp. Brain Res. 2019, 237, 589–599.

- Karagiannopoulos C., Watson J., Kahan S., Lawler D. The effect of muscle fatigue on wrist joint position sense in healthy adults. J. Hand Ther. 2020, 33, 329–338.

- Sayyadi P., Minoonejad H., Seifi F., Sheikhhoseini R., Arghadeh R. The effectiveness of fatigue on repositioning sense of lower extremities: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Sports Sci. Med. Rehabil. 2024, 16, 35. [CrossRef]

- Blank, R.H., Curthoys, I.S., Markham, C.H. Planar relationships of the semicircular canals in man. Acta Otolaryngol. 1975, 80:185–196. [CrossRef]

- Pettorossi V.E., Panichi R., Botti F.M., Kyriakareli A., Ferraresi A., Faralli M., Schieppati M., Bronstein A.M. Prolonged asymmetric vestibular stimulation induces opposite, long-term effects on self-motion perception and ocular responses. J. Physiol. 2013, 591, 1907 1920. [CrossRef]

- Seemungal B.M., Gunaratne I.A., Fleming I.O., Gresty M.A., Bronstein A.M. Perceptual and nystagmic thresholds of vestibular function in yaw. J. Vestib. Res. 2004, 14, 461–466.

- Panichi R., Botti F.M., Ferraresi A., Faralli M., Kyriakareli A., Schieppati M., Pettorossi V.E. Self-motion perception and vestibulo ocular reflex during whole body yaw rotation in standing subjects: the role of head position and neck proprioception. Hum. Mov. Sci. 2011, 30, 314–332. [CrossRef]

- Pettorossi V.E., Panichi R., Botti F.M., Biscarini A., Filippi G.M., Schieppati M. Long-lasting effects of neck muscle vibration and contraction on self-motion perception of vestibular origin. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2015, 126, 1886–1900. [CrossRef]

- Pettorossi V.E., Occhigrossi C., Panichi R., Botti F.M., Ferraresi A., Ricci G., Faralli M. Induction and Cancellation of Self-Motion Misperception by Asymmetric Rotation in the Light. Audiol. Res. 2023, 13, 196-206. [CrossRef]

- Siegle J.H., Campos J.L., Mohler B.J., Loomis J.M., Bülthoff H.H. Measurement of instantaneous perceived self-motion using continuous pointing. Exp. Brain Res. 2009, 195, 429–444. [CrossRef]

- Merletti R., Lo Conte L.R. Surface EMG signal processing during isometric contractions. J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol. 1997, 7, 241-250.

- Mergner T., Siebold C., Schweigart G., Becker W. Human perception of horizontal trunk and head rotation in space during vestibular and neck stimulation. Exp. Brain Res. 1991, 85, 389–404. [CrossRef]

- Mergner T., Rosemeier T. Interaction of vestibular, somatosensory and visual signals for postural control and motion perception under terrestrial and microgravity conditions—a conceptual model. Brain Res. Rev. 1998, 28, 118–135. [CrossRef]

- Filippi G.M., Rodio A., Fattorini L., Faralli M., Ricci G., Pettorossi V.E. Plastic changes induced by muscle focal vibration: a possible mechanism for long-term motor improvements. Front. Neurosci. [CrossRef]

- Souron R., Besson T., Millet G., Lapole T. Acute and chronic neuromuscular adaptations to local vibration training. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2017, 117, 1939–1964. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).