1. Introduction

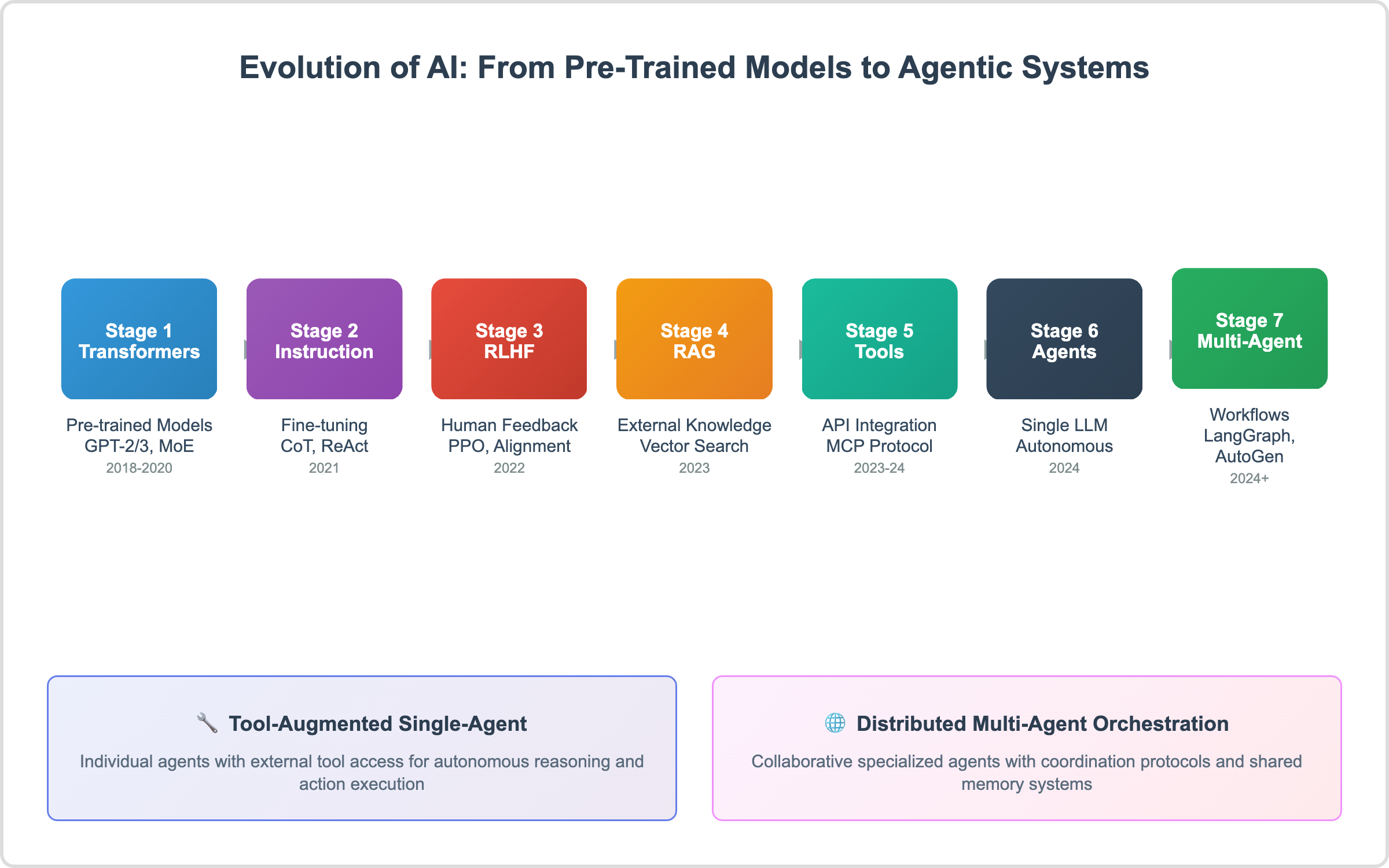

Artificial Intelligence (AI) has evolved rapidly in recent years, transitioning from static, pre-trained language models to dynamic systems capable of autonomous reasoning and coordination. This transformation marks a fundamental shift in the role of AI—from passive language generators to agents that can interact with tools, make decisions, and complete tasks in open-ended environments. We argue that agentic AI represents a critical inflection point in this journey, enabling real-world autonomy while raising important challenges related to scalability, transparency, and equitable access—especially for developing countries with limited digital infrastructure [

1,

2].

This progression began with transformer-based models such as GPT-2 and GPT-3, which introduced attention mechanisms and later Mixture of Experts (MoE) to scale up language modeling using massive training corpora [

3,

4]. While these models demonstrated impressive fluency, they struggled with task specificity, contextual reasoning, and goal-directed behavior. To address this, instruction fine-tuning was introduced to guide models using prompt-response pairs, improving alignment with user intent, though often brittle across diverse tasks [

5]. Reinforcement learning from human feedback (RLHF) further refined alignment by training models based on human preference rankings, improving safety and relevance. However, RLHF introduced new complications such as optimization opacity and increased training complexity [

6].

Despite these advances, language models still relied on static internal knowledge, leading to hallucinations and factual inaccuracies. Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) was among the first methods to address this by allowing models to query external sources in real time [

7]. Although this improved factual grounding, its success depended on the quality of retrieval and effective integration into prompts. RAG also marked the emergence of tool calling, where the model uses external systems to augment its capabilities. This concept generalized further—extending beyond retrieval to include APIs, calculators, databases, and code execution environments. This laid the foundation for

AI agents, defined here as large language models (LLMs) augmented with external tools that they can autonomously call to perform reasoning, planning, and decision-making. In this paradigm, the model becomes an actor, not merely a predictor.

To support such systems, several programming frameworks have emerged. AutoGen, LangGraph, and CrewAI provide mechanisms for task orchestration, memory management, and inter-agent communication in single-agent and multi-agent environments [

8,

9,

10]. These frameworks simplify development but also raise concerns around traceability and coordination overhead. Complementing them, CodeAct enables multi-agent coordination through code-driven reasoning and debugging, offering flexibility but requiring robust safeguards for safety and consistency at scale [

11].

As AI systems adopt agentic capabilities, the focus of research and design shifts from improving generation quality to governing autonomous behavior. Each layer of reasoning and planning adds value—but also complexity and risk. Ensuring transparency, reliability, and responsible deployment becomes essential.

This paper provides a structured analysis of the evolution toward agentic AI across seven stages: transformer-based models, instruction fine-tuning, RLHF, tools integration, RAG, single-agent autonomy, and multi-agent collaboration. We review core architectural foundations (e.g., transformers, MoE), coordination frameworks like CodeAct, and programming tools including AutoGen, LangGraph, and CrewAI [

8,

11]. We then examine the strategic implications of agentic AI—including automation, cost efficiency, and oversight requirements—and assess how these technologies can be leveraged in developing countries to advance healthcare, education, agriculture, and resource management.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 presents the seven-stage evolution of AI systems.

Section 4 synthesizes strategic impacts, deployment challenges, opportunities for developing countries, and future directions for research and implementation. Finally,

Section 5 concludes the paper with a summary of key insights.

2. Evolution of AI: From Pre-Trained Models to Agentic Systems

This section provides a chronological overview of how AI evolved from static language models to agentic systems capable of autonomous reasoning and interaction.

2.1. Stage 1: Transformer-Based Pre-Trained Models (2018–2020)

The advent of transformer-based pre-trained models from 2018 to 2020 marked a transformative milestone in artificial intelligence (AI), enabling large-scale language processing and laying the groundwork for autonomous agentic systems. We argue that this stage introduced scalable architectures but exposed critical limitations in reasoning and intent alignment, driving subsequent advancements. This subsection examines the transformer architecture, Mixture of Experts (MoE), and pre-trained models like GPT-2 [

3]and GPT-3 [

4], detailing their technical components, performance, and constraints, with implications for applications in resource-constrained environments.

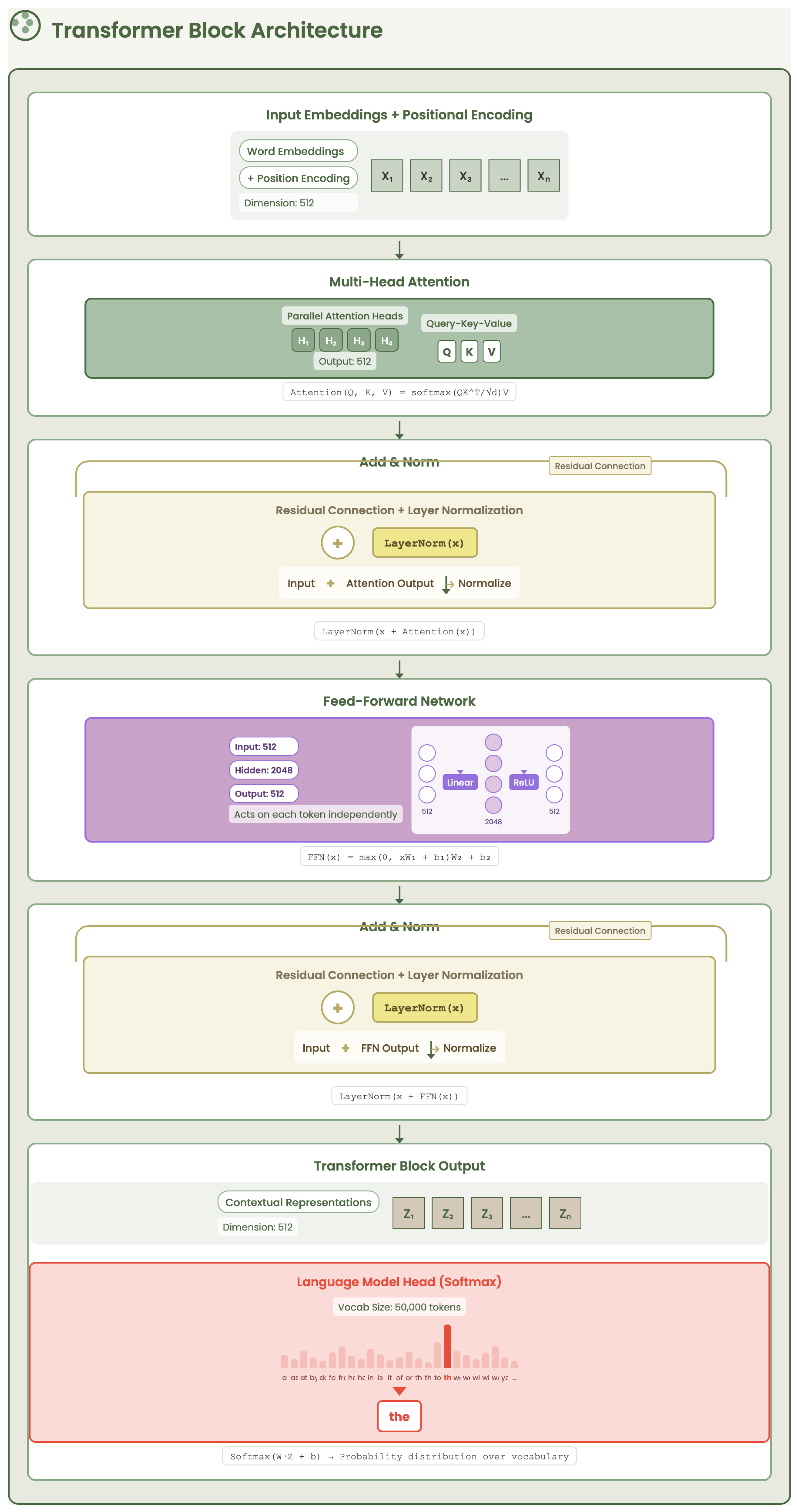

2.1.1. Transformer Architecture Fundamentals

The transformer architecture, introduced by Vaswani et al. [

1], marked a turning point in natural language processing by abandoning recurrence in favor of a purely attention-based mechanism. Its design follows a modular pipeline, where each stage plays a distinct role in transforming raw text into contextualized semantic representations.

The pipeline begins with

tokenization, a crucial preprocessing step that converts unstructured text into discrete sub-word units using algorithms such as Byte-Pair Encoding (BPE) [

12]. This step ensures that rare and compound words are broken down into smaller, reusable segments, enabling the model to generalize across a large vocabulary while maintaining computational tractability.

Once tokens are produced, they are transformed into contextual embeddings. This involves two components: (i) token embeddings encode the semantic identity of each sub-word, and (ii) positional embeddings encode the relative position of each token in the sequence. The combination of these two embeddings allows the model to capture both the meaning and the order of the input text, overcoming the permutation invariance of attention mechanisms.

The hallmark of the transformer lies in its

multi-head self-attention mechanism. At each layer, every token computes weighted interactions with all other tokens in the sequence using a triplet of projections: query, key, and value. This allows the model to attend to relevant context at any distance, effectively capturing long-range dependencies, syntactic structure, and semantic relationships across the entire input sequence. Unlike recurrent neural networks (RNNs), which suffer from sequential bottlenecks and gradient vanishing, transformers allow for full parallelization, dramatically improving training efficiency and scalability [

13].

Following self-attention, representations are passed through a feed-forward network (FFN). This component acts as a form of feature digestion, projecting vectors into a higher-dimensional space, applying non-linear transformations (typically ReLU or GELU), and compressing them back. This refines and filters the features extracted by attention, ensuring that only salient information is propagated to the next layer.

An overview of the transformer block architecture, highlighting the flow from token embeddings through multi-head self-attention and feed-forward layers, is illustrated in

Figure 1.

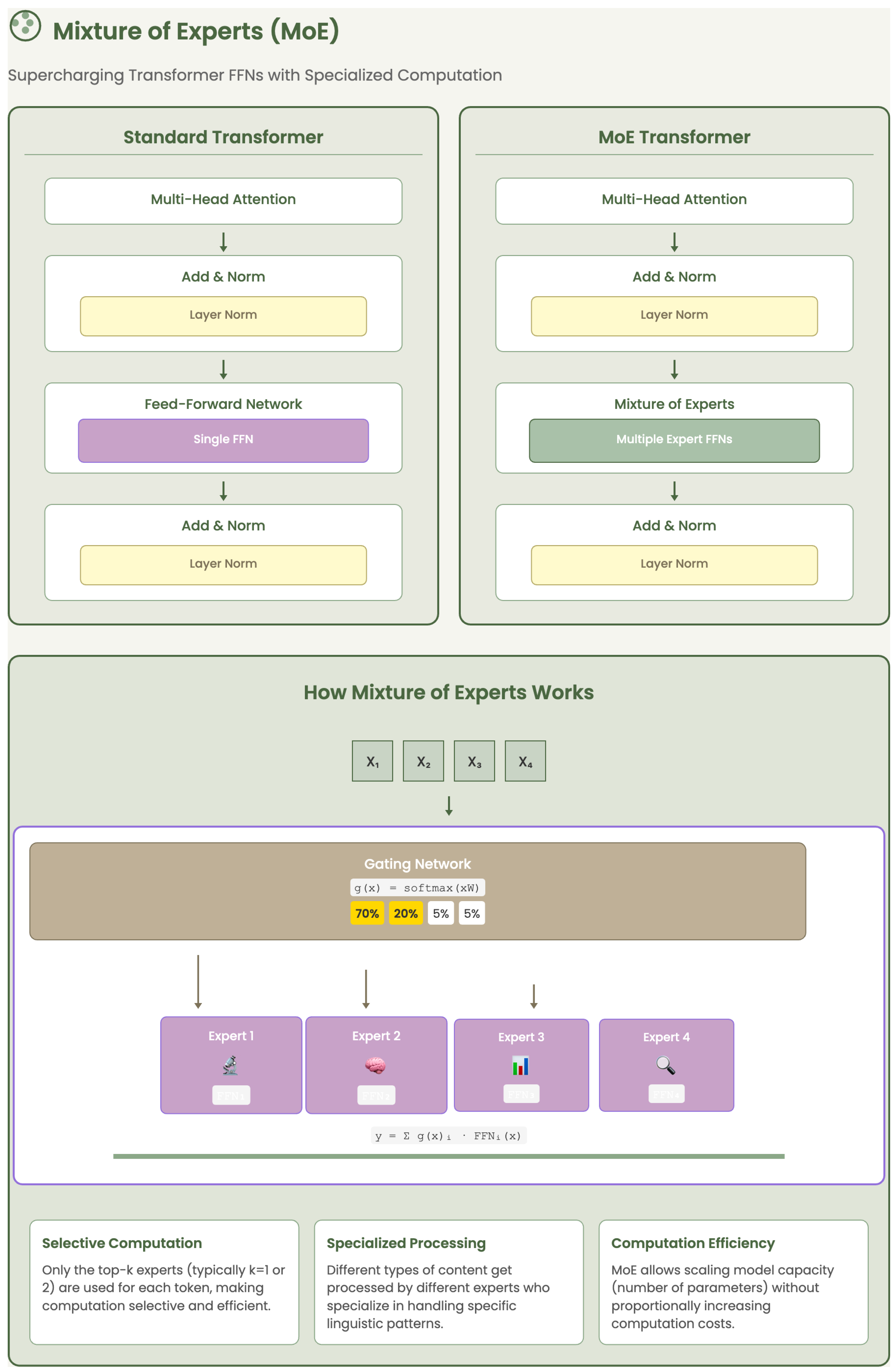

2.1.2. Mixture of Experts (MoE)

As transformer models grew deeper and wider, their computational demands became a limiting factor—especially during inference. To overcome this, the

Mixture of Experts (MoE) architecture was introduced as a scalable alternative to dense feed-forward networks [

2]. The key idea behind MoE is to divide the standard feed-forward layer into a collection of specialized sub-networks, known as

experts, where each expert learns distinct patterns from the data.

Figure 2 provides a schematic representation of the MoE architecture, emphasizing the sparse expert activation controlled by the gating mechanism.

Instead of activating all experts for every token, MoE employs a learnable gating mechanism that dynamically selects only a small subset of experts—typically the top-1 or top-2—for each input token. This mechanism ensures that only the most relevant experts are activated, allowing the model to preserve high representational capacity while significantly reducing computation. For instance, an MoE layer with 8 experts and a top-2 gating strategy activates only 2 experts per token, resulting in a compute cost of just 25% compared to activating all experts, yet maintaining a comparable level of performance.

This sparse activation strategy introduces both efficiency and specialization. Efficiency comes from not having to evaluate every expert for every token, making it feasible to train and deploy much larger models. Specialization emerges as different experts focus on different linguistic, semantic, or structural aspects of the data, allowing the model to better adapt to diverse inputs.

The introduction of MoE layers proved to be a turning point in the architecture of large language models [

14]. It enabled the training of models with billions of parameters while keeping inference tractable—an essential advancement for pushing the limits of generative AI in real-world, resource-constrained scenarios.

2.1.3. Pre-Trained Models: GPT-2 and GPT-3

The advent of GPT-2 and GPT-3 marked a major leap in generative language modeling. These models, built upon the transformer architecture and scaled with billions of parameters—1.5B for GPT-2 and 175B for GPT-3—demonstrated impressive capabilities in generating fluent and contextually consistent text [

3,

4]. Trained on massive corpora like WebText and Common Crawl, they employed a simple yet powerful objective: next-token prediction.

GPT-2 achieved strong performance in zero-shot settings, with remarkable results on benchmarks like LAMBADA. GPT-3 extended these capabilities further, showcasing few-shot and even one-shot learning by conditioning on examples directly in the prompt. For instance, it scored 86.4% on TriviaQA without fine-tuning [

4].

Despite these advances, both models remained fundamentally limited. They operated on surface-level statistical patterns without understanding or reasoning. Their outputs, while coherent, were not aligned with user goals, lacked memory, and could not adapt dynamically to changing tasks or environments. These constraints became critical in real-world domains such as robotics or healthcare, where intent-awareness and external knowledge access are essential.

Nevertheless, GPT-2 and GPT-3 laid the groundwork for scalable generative AI. They proved that large-scale pretraining could generalize across tasks, inspiring the need for better alignment mechanisms—such as instruction fine-tuning—which we explore in the next section.

2.2. Stage 2: Instruction Fine-Tuning (2021)

The second stage in the evolution of large language models introduced a paradigm shift by moving from generic pre-trained text generation to models that follow explicit human instructions. This process, called instruction fine-tuning, aligns model behavior with task-specific goals and user expectations [

5].

At the core, instruction fine-tuning consists of training a base generative model using supervised examples—pairs of prompts and corresponding high-quality responses. These examples span a wide range of tasks (e.g., classification, summarization, translation), enabling the model to learn not just what to predict, but how to structure its outputs based on explicit instructions.

Why it matters: Instruction fine-tuning enhances:

Controllability: The model responds more accurately to varied user intents.

Safety and factuality: Trained models are less likely to hallucinate or produce harmful content.

Task-specific performance: It enables models to generalize better across downstream tasks without retraining.

Prompt Engineering: A Complementary Technique

In parallel to instruction fine-tuning,

prompt engineering emerged as a practical method to guide and shape model behavior without modifying weights. It plays a critical role in extracting reliable, interpretable, and domain-aligned outputs from a single model [

15].

Several advanced prompting strategies have been introduced to improve reasoning, reduce hallucinations, and increase alignment:

-

Chain-of-Thought (CoT): Introduces intermediate reasoning steps to help the model think through problems (e.g., math or logic). This makes its outputs more traceable and reduces logical errors [

16].

Example: To solve “What is 15% of 80?”, the model first converts 15% to decimal (0.15), then multiplies: .

-

Tree-of-Thought (ToT): Explores multiple reasoning paths like a decision tree, which prevents premature conclusions and encourages diverse solution paths [

17].

Example: For the question “How can a company increase profits?”, the model evaluates different branches:

- −

Option 1: Cut operational costs.

- −

Option 2: Raise product prices.

- −

Option 3: Expand to new markets.

-

ReAct (Reasoning + Acting): Combines reasoning with real-time action (e.g., tool use or fact-checking), improving factual grounding [

18].

Example: Q: “What is the capital of France?”

Thought: I need to verify.

Action: Search “capital of France”.

Observation: Paris.

Final Answer: Paris.

Structuring Outputs: Techniques such as Few-Shot Prompting and Role-Based Prompting provide contextual anchors that help the model produce outputs in a well-defined format and tone. This is especially important in high-stakes domains such as legal drafting, scientific summarization, or instructional design, where consistency and precision are critical.

Iterative Techniques: Methods like

Self-Consistency [

19] and

Prompt Chaining reduce generation variability by enforcing redundancy or decomposing tasks into sequential steps. By validating outputs across multiple runs or maintaining logical continuity through chained prompts, these techniques significantly mitigate hallucination risks.

Key Benefit: Prompt engineering serves not only as a performance enhancer but also as a control mechanism against hallucinations. By explicitly guiding the model’s reasoning process, reinforcing structural expectations, and encouraging factual alignment with reference data or tools, prompt engineering transforms LLMs from stochastic generators into more reliable and trustworthy assistants.

In summary, instruction fine-tuning and prompt engineering together mark the transition from passive language generators to reliable, domain-aware assistants. While instruction tuning aligns the internal representations with human intent, prompt engineering provides an external layer of guidance to extract the best reasoning and factual quality from the model at runtime.

2.3. Stage 3: Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback (RLHF)

Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback (RLHF) represents a pivotal advancement in aligning large language models (LLMs) with human values, beyond static instruction tuning. Traditional supervised fine-tuning treats target outputs as ground truth, regardless of subjective quality. In contrast, RLHF introduces an adaptive loop that incorporates human evaluations into the optimization process, allowing models to be trained not only to follow instructions but also to exhibit preferred behavioral traits such as helpfulness, harmlessness, and honesty [

5,

20].

The process begins by generating multiple candidate completions for a given prompt using the pre-trained model. Human annotators then rank these outputs according to preference. These ranked examples are transformed into pairwise comparisons and used to train a reward model

— typically a neural network that estimates the alignment quality of a given output

y conditioned on input

x. The reward model learns to assign higher scores to preferred outputs and lower scores to undesirable ones, effectively approximating human judgment [

6].

Formally, given a pair of responses

for the same prompt

x, where

is preferred over

, the reward model is optimized to satisfy:

using a loss function such as the pairwise logistic loss or Bradley-Terry loss [

21]:

Once the reward model is trained, it serves as the objective function to guide the language model’s behavior. A policy

(i.e., the language model’s distribution over outputs) is fine-tuned to maximize the expected reward:

To perform this optimization safely and efficiently, RLHF commonly uses the Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO) algorithm [

22], which ensures controlled updates to the policy and mitigates the risk of reward hacking [

22,

23]. In practice, PPO is often regularized using a KL penalty to constrain the policy from deviating too far from the reference model, ensuring safe optimization [

5].

The PPO objective balances reward maximization with policy stability:

where

is the probability ratio between new and old policies and

is the advantage estimate based on the reward model.

To illustrate, consider a prompt such as "How can I make money quickly?". The model might generate:

Human annotators may rank (2) and (3) higher due to safety and practicality, while downranking (1). Through training, the model internalizes such preferences and learns to prioritize ethical and safe responses in future generations — thus aligning with human intent beyond syntactic accuracy.

RLHF has proven instrumental in shaping models like ChatGPT, which exhibit reduced hallucination, enhanced factual grounding, and user-centric behavior. However, limitations persist: RLHF models are still reactive to prompts, lack autonomous planning capabilities, and remain constrained by the biases in human feedback [

24]. These challenges open new directions for agentic AI systems, which seek to go beyond response generation and incorporate self-driven reasoning and goal execution.

2.4. Stage 4: Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG)

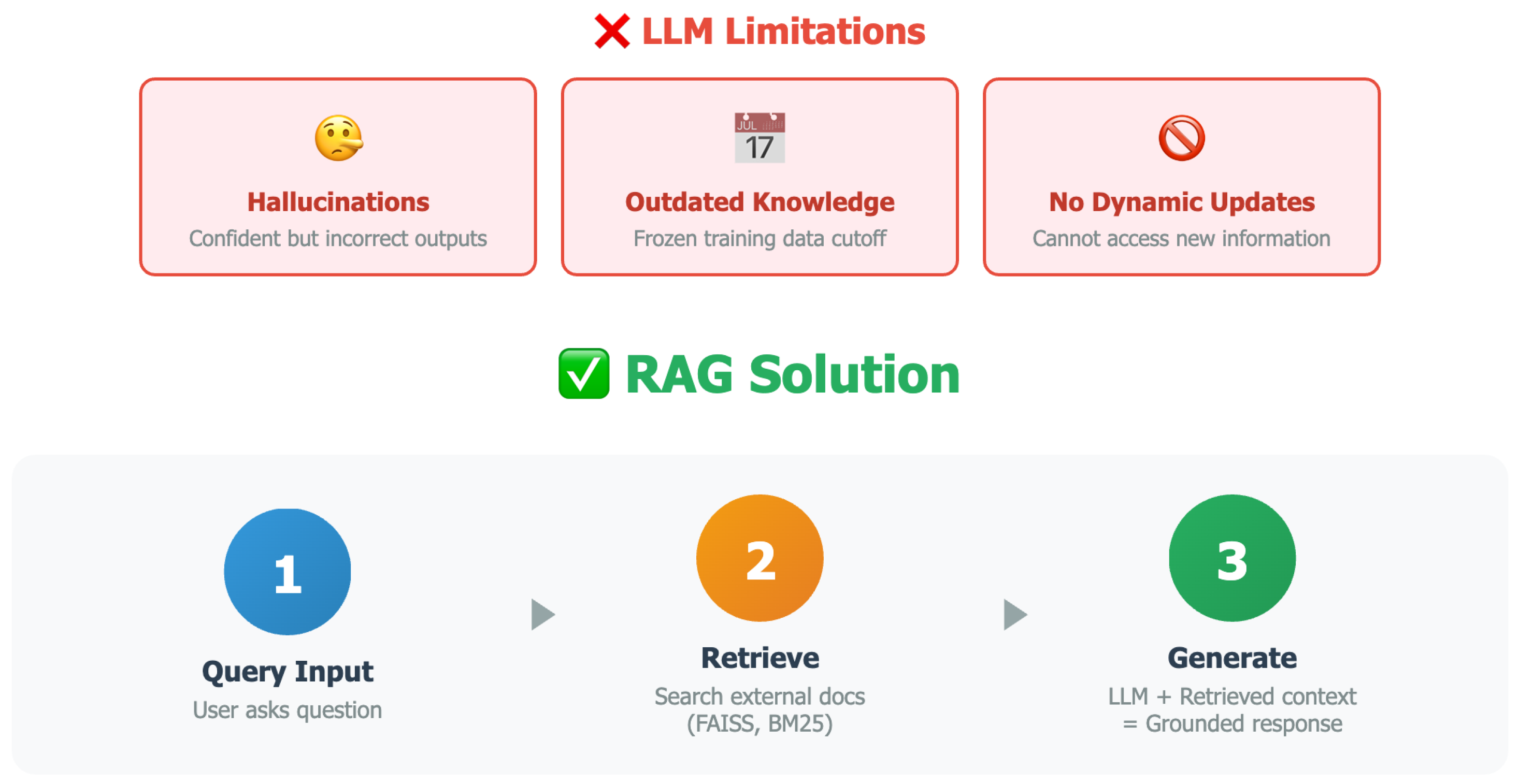

As large language models (LLMs) continued to scale, a key limitation persisted: their inability to access external knowledge beyond their training data. Despite the benefits of fine-tuning, LLMs remained static in nature—frozen after training on a fixed corpus. This led to several critical issues, including hallucinations (i.e., confident but incorrect outputs), outdated knowledge, and the inability to dynamically update facts. Fine-tuning alone proved insufficient to resolve these shortcomings, particularly in tasks requiring factual precision or domain-specific updates.

This process is illustrated in

Figure 3, where the retriever fetches relevant context from an external knowledge base and the generator produces grounded responses conditioned on this information.

Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG), introduced by Lewis et al. [

7], addressed this gap by integrating a retrieval mechanism into the generative pipeline. Rather than relying solely on memorized knowledge, RAG systems connect LLMs to external, often up-to-date, information sources (e.g., databases, document stores, or search engines). This hybrid architecture introduces two main components: a retriever that identifies relevant documents based on a user query, and a generator that conditions its response on the retrieved content.

The retrieval step typically employs dense or sparse vector search (e.g., FAISS [

25] or BM25[

26]) to identify semantically relevant passages. These retrieved contexts are then appended to the prompt or embedded directly into the model’s attention space before generating a response. This process significantly reduces hallucination by grounding the generation in factual evidence and enables the model to access knowledge beyond its training cutoff.

From an engineering perspective, RAG offers several advantages over traditional fine-tuning:

Modularity: Knowledge updates can be made by modifying the retrieval corpus without retraining the model.

Efficiency: Retrieval systems are more computationally efficient than repeated fine-tuning for each domain or update.

Transparency: The retrieved documents provide interpretability and support for the generated response.

RAG has been widely adopted in applications such as document question answering, PDF chat systems, semantic search, and chatbot assistants in enterprise settings. For instance, in a legal assistant scenario, RAG enables the model to retrieve case law or policy clauses from a legal database, thereby avoiding hallucinated legal claims.

Overall, RAG represents a major evolution in LLM architectures. By blending search and generation, it bridges the gap between static models and dynamic knowledge environments, providing a more robust and factually grounded AI assistant.

Towards Tool Use and System Integration. The emergence of Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) laid the foundational architecture for functional modularity in LLMs. By separating static model parameters from dynamic external knowledge, RAG introduced the idea that models could consult tools—in this case, search engines or vector databases—at inference time. This was a first step toward broader tool integration, where LLMs not only retrieve documents but also invoke APIs, perform calculations, read files, and interact with structured systems [

27]. The conceptual shift from “memorize everything” to “consult when needed” opened the door for more general frameworks involving external function calls, which we will explore in the next stage.

2.5. Stage 5: Tools and APIs Integration

As we move beyond pure text generation, the need arises for language models to interact with external systems, perform actions, and access up-to-date information. This capability builds on earlier ideas of reasoning-augmented tool use such as in ReAct [

18]. This is where

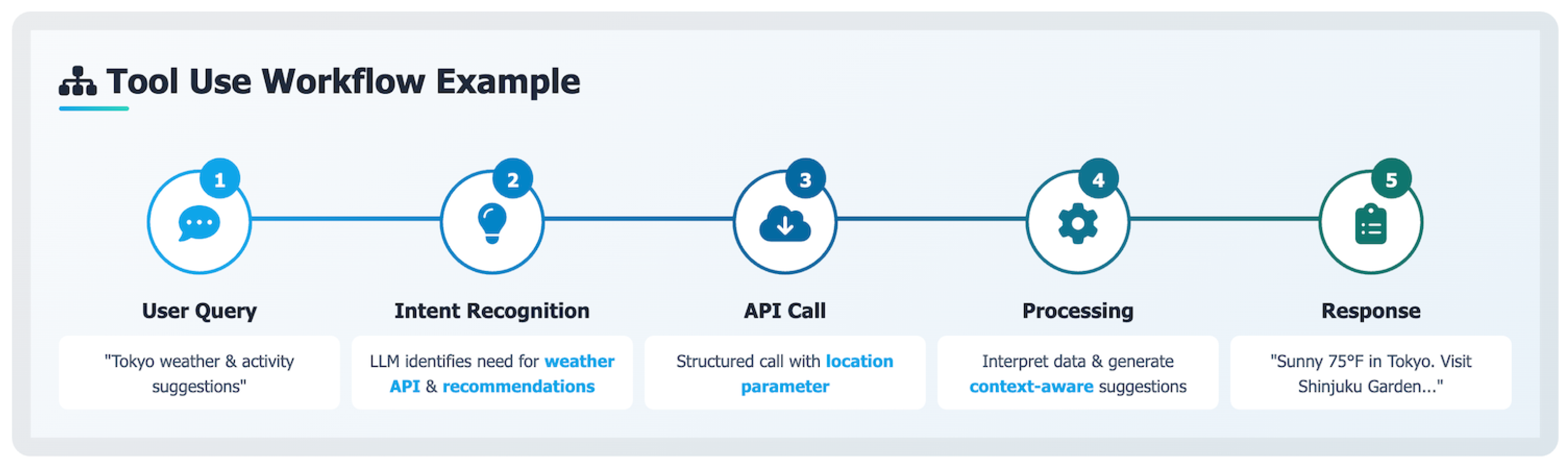

Tool and API integration becomes essential.

While Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) allows LLMs to fetch documents, many user tasks require executing real-time functions, such as calculations, scheduling, or searching a live database. To address this need, recent LLMs have been enhanced with the ability to call external tools through well-defined APIs.

An example of this tool integration workflow is shown in

Figure 4, demonstrating how LLMs bridge text understanding with real-world actions via APIs.

From Text to Action.

In this stage, the LLM transitions from being just a text generator to becoming a reasoning engine that can plan, choose tools, call them, and process results. For example, when asked, “What’s the current exchange rate between USD and EUR?”, the model needs to recognize this task, invoke the appropriate tool (like getExchangeRate), and return a factually correct response.

Training for Intent Understanding.

A key requirement for enabling tool use is that the LLM must be trained to

understand user intent and to

select the right tool based on the request [

27]. This is typically done using supervised fine-tuning datasets that teach the model to generate structured function calls instead of plain answers.

Not all language models support this capability out of the box. For example, OpenAI’s GPT-4 supports native tool calling through structured JSON-based function calls [

28], while many other models do not yet support this feature natively.

How It Works.

Tool integration typically involves the following steps:

Tool Registration: Each tool is described with a name, description, and input/output schema.

Function Call Prediction: The LLM is prompted (or fine-tuned) to detect when a tool is needed and how to call it.

Tool Execution: A backend system receives the tool call, executes it, and returns the result.

Result Injection: The result is returned to the LLM, which then generates a complete response.

Example.

User query:

"Check the weather in Paris tomorrow and summarize the forecast."

The model may internally generate:

getWeather(city="Paris", date="tomorrow") → "Sunny, 24°C"

Final output:

"Tomorrow in Paris, the weather will be sunny with a high of 24°C."

The Role of MCP.

Before the emergence of standardized protocols, the integration of external tools with language models was fragmented and ad hoc. Each system relied on custom interfaces, undocumented behaviors, and brittle assumptions about how models should call tools—making such integrations difficult to scale, reproduce, or secure.

To address this gap, Anthropic introduced the

Model Context Protocol (MCP) [

29], the first practical attempt to standardize how external tools, APIs, and data sources are exposed to language models during inference. MCP defines a machine-readable schema that describes each tool’s name, purpose, input/output formats, and authentication requirements. It acts as a declarative interface layer through which models can dynamically discover and invoke available tools within a given context.

I often refer to MCP as a kind of REST API for resources in AI—a conceptual framework that enables AI systems to reason over structured, discoverable, and securely defined resources, much like how web applications consume RESTful services.

MCP brings three key advantages:

Unification: A common protocol replaces hand-crafted tool-call mechanisms with a structured, extensible specification.

Context-awareness: Tools are only made available to the model within a relevant context, improving safety and reasoning efficiency.

Automation-readiness: Because tools are self-describing, models can auto-generate calls, parse responses, and chain actions in autonomous workflows.

By acting as a middleware layer between the model’s reasoning engine and the external environment, MCP is essential to enabling agentic behaviors. It allows LLMs not only to interpret natural language but also to interact with external systems in a secure, modular, and verifiable manner.

Insights

Stage 5 marks a pivotal shift in the evolution of language models—from passive generators of text to active participants in real-world tasks. By integrating tools through standardized interfaces like MCP, LLMs gain the capacity to retrieve information, perform computations, and interact with dynamic environments. This grounding significantly mitigates hallucinations by anchoring model outputs in factual and verifiable sources. Moreover, tool use lays the foundation for more advanced capabilities—setting the stage for models that not only access external tools but also coordinate reasoning, memory, and planning. This transition leads directly to Stage 6, where LLMs begin to operate as autonomous agents capable of multi-step task execution, decision-making, and self-driven prompt generation [

30].

2.6. Stage 6: Single LLM Agents

Stage 6 represents a major paradigm shift in the evolution of large language models—from passive tool users to autonomous agents capable of reasoning, planning, acting, and learning within a single architectural framework. Unlike prior stages where models merely responded to prompts or executed tools when explicitly guided, single-agent systems embody a more integrated intelligence loop, where the LLM itself orchestrates all steps of the cognitive process.

Figure 5 illustrates this autonomous agentic loop, where a single LLM performs reasoning, planning, tool selection, action execution, and self-reflection in an iterative workflow.

At the core of these agents is the ability to reason through problems using mechanisms like Chain-of-Thought (CoT) prompting [

16], which enables step-by-step logical decomposition of tasks. This reasoning is not static: the model can observe the outcomes of its previous actions, reflect on errors or progress, and update its internal state accordingly—a concept sometimes referred to as

self-reflection or

inner monologue [

31].

Planning emerges as a crucial capability, where the agent decomposes complex goals into subgoals and dynamically selects tools or actions to achieve them. Acting, in this context, involves invoking APIs, retrieving data, or querying databases—all without explicit human instruction at each step. These capabilities are tightly interwoven in a loop [

18]:

Reasoning: The agent breaks down the task into logical steps using CoT.

Acting: It takes concrete actions (e.g., API calls, tool invocation) based on its reasoning.

Observing: It assesses the outcomes of its actions and updates its knowledge or next steps.

Planning: Based on observations, it revises its strategy to continue toward the goal.

Systems such as LangChain’s

AgentExecutor [

9] and Microsoft’s AutoGen [

8] demonstrate practical implementations of this loop, enabling LLMs to autonomously solve multi-step tasks [

32] with minimal human input. While still constrained by the capabilities of single LLMs, this stage establishes the foundational behavior of autonomous agents—setting the stage for multi-agent collaboration in Stage 7.

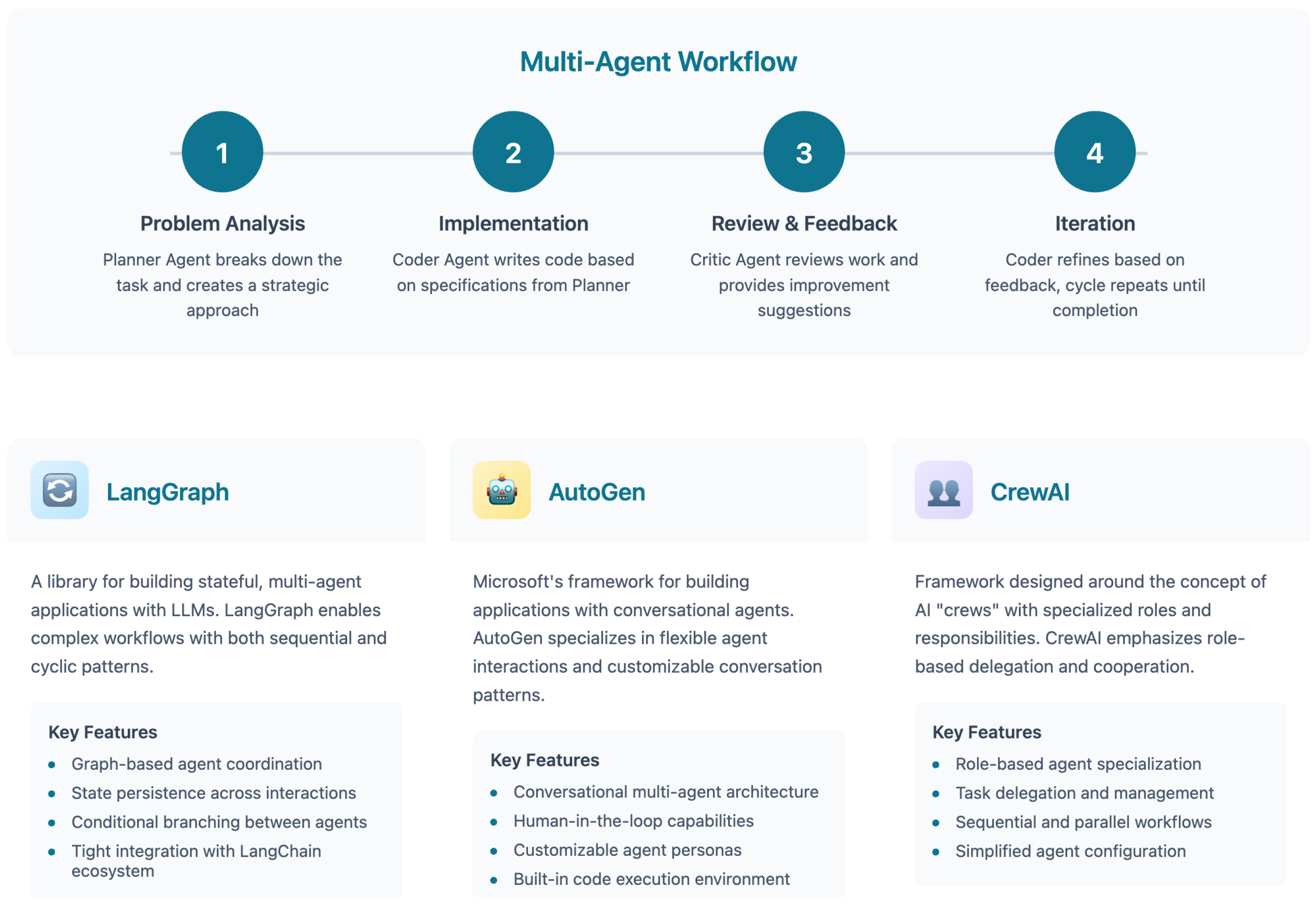

2.7. Stage 7: Agentic AI Workflows

As the capabilities of large language models (LLMs) evolved, a critical limitation emerged: even the most advanced single-agent systems could not sustain long, complex, or multitask workflows. Stage 7 addresses this limitation by introducing agentic AI workflows, where multiple specialized LLM agents collaborate to perform structured, multi-step tasks. This transition parallels the evolution from monolithic computing to distributed systems—enhancing flexibility, robustness, and scalability.

Figure 6.

Multi-Agent Systems.

Figure 6.

Multi-Agent Systems.

Unlike Stage 6, which focuses on self-contained LLMs that observe, reason, and act, Stage 7 introduces coordination and modularity. A task is no longer solved by one model alone, but instead distributed across a set of interacting agents. These agents operate independently, yet communicate through well-defined protocols, enabling task decomposition, specialization, and feedback across the system.

Core Capabilities.

Agentic AI systems bring several novel capabilities that overcome the constraints of monolithic LLM reasoning:

Task Decomposition: A central planner agent breaks down complex problems into subtasks.

Specialized Roles: Different agents are assigned domain-specific functions (e.g., coding, data analysis, summarization).

Memory Sharing: Shared context or memory buffers enable continuity across agents.

Collaboration Protocols: Orchestrators like

LangGraph [

9],

AutoGen [

8], or

CrewAI [

10] coordinate agent execution, feedback, and control flow.

Illustrative Example.

Consider a research assistant workflow:

The Planner Agent parses a user request: “Find recent AI papers on agentic systems and summarize their contributions.”

It dispatches subtasks to a Search Agent, a Summarizer Agent, and a Citation Verifier Agent.

Each agent performs its function independently—querying arXiv, writing summaries, or validating references.

The Supervisor Agent integrates results and decides whether to loop, revise, or finalize the response.

This architecture mimics real-world team dynamics, where division of labor and iterative refinement lead to higher-quality outcomes.

Advantages Over Stage 6.

Agentic AI workflows offer several distinct advantages over single-agent systems introduced in Stage 6. First, they enable

scalability by distributing subtasks across multiple agents, allowing for parallel execution and reducing the memory constraints typically faced by a single LLM. Second, they promote

modularity, as each agent is designed with a specific role and can be independently updated, replaced, or reused in different workflows. This modularity enhances maintainability and flexibility across applications. Third, these workflows support seamless

tool integration, where agents interact with external resources through standardized interfaces such as the Model Context Protocol (MCP) [

29], enabling dynamic access to APIs and databases. Finally, agentic systems help in

reducing hallucinations by incorporating dedicated agents for fact-checking and external verification, ensuring that responses are grounded in real-time data and evidence-based reasoning.

Strategic Impact.

Stage 7 marks a fundamental shift from isolated LLM capabilities to the orchestration of

autonomous, multi-agent systems. Rather than relying on a single model with linear reasoning capabilities, agentic workflows distribute cognitive load across a collaborative network of agents—each specializing in a defined role. This architecture enables structured planning, dynamic task execution, self-correction through feedback loops, and informed decision-making through tool integration. As a result, we witness the emergence of

LLM ecosystems, where coordination and role-based specialization [

33] unlock a new generation of AI systems capable of handling end-to-end processes with minimal human oversight. These developments are already redefining applications in scientific discovery, automated software development, legal analysis, and personalized education.

Outlook.

Despite their transformative potential, current agentic workflows remain limited by

static roles, ephemeral memory, and rigid context windows. Agents today operate in session-bound environments, lacking long-term identity [

34], adaptability, or personal learning trajectories. This limitation opens the path toward Stage 8, which envisions

persistent, memory-augmented agents capable of evolving over time. Such agents will not only collaborate, but also learn from experience, build domain expertise, retain user-specific preferences, and update their internal state across sessions. This shift represents the transition from reactive orchestration to proactive cognition—laying the groundwork for AI agents that operate as long-term collaborators in dynamic, real-world environments.

3. Agentic AI Programming Frameworks

As language models transition from single-turn responders to autonomous, multi-agent systems, dedicated frameworks have emerged to facilitate agentic coordination, modularity, and workflow execution. This section examines three leading agentic AI programming frameworks—LangGraph, AutoGen, and CrewAI—through the lens of programmability, orchestration control, memory management, and use case specialization.

3.1. AutoGen: Conversational Multi-Agent Coordination

AutoGen, developed by Microsoft, provides a conversational orchestration framework where agents interact through message-passing and role-based dialogue [

8]. Each agent operates with configurable personas and behaviors, enabling dynamic coordination in workflows such as code generation, research assistance, or customer support. AutoGen supports human-in-the-loop participation and modular backend integration with OpenAI, Azure, or other LLMs.

Despite its flexibility, AutoGen lacks native replay or time-travel debugging features, relying instead on intervention modes (e.g., NEVER, ALWAYS, TERMINATE) to control loop progression. This can limit convergence in complex or non-deterministic workflows. However, AutoGen excels in scalability and has strong ecosystem support, making it ideal for production-grade applications that prioritize responsiveness and extensibility.

3.2. LangGraph: Graph-Based Workflow Orchestration

LangGraph builds on the LangChain ecosystem by offering a graph-based orchestration model for multi-agent workflows [

9]. Agents are represented as nodes in a directed graph, with transitions governed by conditions, branching logic, and memory state. This structure enables expressive modeling of sequential, parallel, and cyclic workflows, making LangGraph particularly suited for long-running or fault-tolerant applications.

LangGraph’s strength lies in its fine-grained control, including replayability, state recovery, and runtime introspection. Developers can visualize task trajectories and debug complex flows using time-travel mechanisms. However, this expressiveness introduces a steeper learning curve, requiring a deeper understanding of state machines and workflow engineering. LangGraph is best positioned for applications demanding precise orchestration, such as research pipelines, legal assistants, or multi-turn reasoning systems.

3.3. CrewAI: Role-Based Agent Orchestration

CrewAI adopts a lightweight, role-based architecture designed around the concept of collaborative “crews” of agents [

10]. Each agent is assigned a specific role (e.g., planner, coder, reviewer), with coordination managed via structured task plans and YAML configurations. CrewAI supports sequential and parallel execution, memory sharing, and replay of recent tasks.

The framework prioritizes ease of use and rapid prototyping, offering low-code interfaces suitable for educational, startup, or experimental settings. While its replay mechanism is limited to the most recent task execution and lacks stateful time-travel, its simplicity and developer-friendly API make it ideal for small-to-medium-scale agent workflows. CrewAI is rapidly growing in adoption, particularly in community-driven scenarios requiring fast iteration and role delegation.

3.4. Comparative Analysis of Frameworks

Table 1 presents a comparative overview of the three frameworks across key dimensions relevant to agentic AI programming.

Strategic Insight.

LangGraph offers the most granular control and advanced recovery capabilities, making it ideal for deterministic and stateful multi-agent workflows. AutoGen balances modularity and scalability with flexible agent communication but requires manual oversight in complex paths. CrewAI favors accessibility and speed, serving as an effective platform for structured experimentation and educational use.

Outlook.

Agentic AI programming is transitioning toward modular, composable ecosystems where LLM agents communicate, coordinate, and execute tasks with minimal supervision. Frameworks like LangGraph, AutoGen, and CrewAI serve distinct roles within this ecosystem—supporting the spectrum from rigorous, production-level applications to lightweight, collaborative prototyping. The next frontier involves persistent agent memory, adaptive behavior, and self-improving orchestration logic.

4. Strategic Discussion and Future Outlook

The rise of agentic AI marks not just a technical evolution, but a strategic inflection point in AI deployment. These systems, composed of LLMs augmented with memory, planning modules, and tool orchestration, enable autonomous execution of complex workflows across domains. From code generation pipelines to scientific hypothesis testing, agentic AI systems offer 24/7 task fulfillment, elastic scaling, and process acceleration—capabilities that challenge traditional labor and operational paradigms. However, this also shifts accountability toward continuous oversight, demanding new models of human-AI collaboration and auditability [

35].

Despite their promise, deployment at scale faces several friction points. Technically, integrating agentic workflows with legacy systems—many of which lack APIs or structured schemas—requires interface layers and robust tool abstraction protocols such as the Model Context Protocol (MCP). Moreover, agent-based reasoning, while powerful, increases the system’s internal complexity and interpretability challenges. Decision trajectories become less transparent, especially in long-horizon planning where multiple agents co-evolve strategies. Ensuring reliability, reversibility, and control over emergent behaviors remains an open problem.

For the Global South, agentic AI holds unique potential to bypass infrastructure gaps. Lightweight agentic agents deployed on edge devices or integrated with SMS gateways can deliver personalized health triage, remote tutoring, or agricultural monitoring with minimal connectivity. Case studies from rural Mauritania show telehealth agents coordinating local health resources using a multi-agent plan-execute framework, while Sub-Saharan pilots explore curriculum-aligned tutoring agents running on open hardware.

Scalable adoption calls for phased implementation: starting with hybrid setups where humans validate agentic output, followed by incremental automation once reliability thresholds are met. Open-source toolkits, transparent logging, and community governance are essential for trust-building. Regulatory bodies must define audit requirements and sandbox environments before mass deployment. Ultimately, agentic AI offers a blueprint for inclusive digital transformation—but only if coupled with thoughtful design, equitable access, and continuous alignment with human values.

5. Conclusions

The transition from static language models to agentic AI systems reflects a deeper shift in our understanding of intelligence—not as isolated prediction, but as interactive, goal-directed reasoning. Each stage in this evolution addressed specific limitations: lack of alignment, hallucinations, or inability to act autonomously. Yet as capabilities increase, so do the risks—ranging from emergent behavior to ethical opacity.

Our review shows that while frameworks like AutoGen, LangGraph, and the Model Context Protocol (MCP) offer promising abstractions for modularity and tool integration, they are only as reliable as their design principles—particularly with respect to interpretability, security, and coordination. Single-agent systems offer tractability, but their limitations in scalability and specialization make the multi-agent paradigm not just useful, but necessary. However, agentic workflows introduce new layers of complexity that must be critically examined: How do we measure the correctness of an agent team? What governance mechanisms ensure safe delegation?

Agentic AI may be a technical milestone, but it is also a socio-technical one. Its success hinges not only on models but on ecosystems—legal, infrastructural, and human. Future work must bridge these domains, prioritizing adaptive memory, transparent decision pipelines, and inclusive deployment strategies, especially in under-resourced contexts. The path forward is not merely about smarter agents, but about more accountable systems.

References

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, L.; Polosukhin, I. Attention is All You Need. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2017, 30. [Google Scholar]

- Shazeer, N.; Mirhoseini, A.; Maziarz, K.; Davis, A.; Hinton, G. Outrageously Large Neural Networks: The Sparsely-Gated Mixture-of-Experts Layer. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1701.06538. [Google Scholar]

- Radford, A.; Wu, J.; Child, R.; Luan, D.; Amodei, D.; Sutskever, I. Language Models are Unsupervised Multitask Learners. OpenAI Blog 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, T.B.; Mann, B.; Ryder, N.; et al. Language Models are Few-Shot Learners. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2020, 33. [Google Scholar]

- Ouyang, L.; Wu, J.; Jiang, X.; et al. Training Language Models to Follow Instructions with Human Feedback. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2203.02155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christiano, P.F.; Leike, J.; Brown, T.B.; et al. Deep Reinforcement Learning from Human Preferences. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2017, 30. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, P.; Perez, E.; Piktus, A.; et al. Retrieval-Augmented Generation for Knowledge-Intensive NLP Tasks. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2020, 33. [Google Scholar]

- Microsoft. AutoGen: Enabling Next-Gen LLM Applications via Multi-Agent Conversation. https://microsoft.github.io/autogen, 2024.

- LangChain. LangGraph: A Framework for Multi-Agent Workflows. https://langchain.com/langgraph, 2024.

- CrewAI Team. CrewAI: Orchestrating Role-Based AI Agents. https://crewai.com, 2024.

- CodeAct Team. CodeAct: A Framework for Code-Based AI Agents. https://codeact.org, 2024.

- Sennrich, R.; Haddow, B.; Birch, A. Neural Machine Translation of Rare Words with Subword Units. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 54th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Shoeybi, M.; Patwary, M.; Puri, R.; LeGresley, P.; Casper, J.; Catanzaro, B. Megatron-LM: Training Multi-Billion Parameter Language Models Using Model Parallelism. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1909.08053. [Google Scholar]

- Lepikhin, D.; Lee, H.; Xu, Y.; et al. GShard: Scaling Giant Models with Conditional Computation and Automatic Sharding. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2006.16668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Yuan, W.; Fu, J.; Jiang, Z.; Hayashi, H.; Neubig, G. Pre-train, Prompt, and Predict: A Systematic Survey of Prompting Methods in Natural Language Processing. ACM Computing Surveys 2023, 55, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Wang, X.; Schuurmans, D.; Bosma, M.; Ichter, B.; Xia, F.; Chi, E.; Le, Q.V.; Zhou, D. Chain of Thought Prompting Elicits Reasoning in Large Language Models. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2201.11903. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, S.; Yu, D.; Zhao, J.; Shafran, I.; Griffiths, T.L.; Cao, Y.; Narasimhan, K. Tree of Thoughts: Deliberate Problem Solving with Large Language Models. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2023, 36. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, S.; Zhao, J.; Yu, D.; Du, N.; Shafran, I.; Narasimhan, K.; Cao, Y. ReAct: Synergizing Reasoning and Acting in Language Models. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2210.03629. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Wei, J.; Schuurmans, D.; Le, Q.; Chi, E.H.; Narasimhan, K.; Zhou, D. Self-Consistency Improves Chain of Thought Reasoning in Language Models. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2203.11171. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, Y.; Jones, A.; Ndousse, K.; Askell, A.; Chen, A.; Goldie, A.; Mirhoseini, A.; Olsson, C.; Saunders, W.; Schulman, J.; et al. Training a Helpful and Harmless Assistant with Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2204.05862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, R.A.; Terry, M.E. Rank analysis of incomplete block designs: I. The method of paired comparisons. Biometrika 1952, 39, 324–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulman, J.; Wolski, F.; Dhariwal, P.; Radford, A.; Klimov, O. Proximal policy optimization algorithms. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1707.06347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngo, R.; Chan, E.; Kaplan, J.; Amodei, D. Scaling Laws for Reward Model Overoptimization. Anthropic blog https://www.anthropic.com/index/scaling-laws-for-reward-model-overoptimization. 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, J.; Schuurmans, D.; Chi, E.H.; Zhou, D.; Le, Q.V. Language Models Can Self-Improve. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2210.11610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, J.; Douze, M.; Jégou, H. Billion-scale similarity search with GPUs. IEEE Transactions on Big Data 2019, 7, 535–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, S.; Zaragoza, H. The probabilistic relevance framework: BM25 and beyond. Foundations and Trends in Information Retrieval 2009, 3, 333–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schick, T.; Dwivedi-Yu, Y.K.; Sorensen, L.; et al. Toolformer: Language Models Can Teach Themselves to Use Tools. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2302.04761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OpenAI. Function Calling with GPT-4 and GPT-3.5. https://platform.openai.com/docs/guides/function-calling, 2023.

- Anthropic. Model Context Protocol (MCP): Towards Safer Tool Use with Language Models. https://www.anthropic.com/index/mcp, 2024.

- Richards, T.B. AutoGPT: An Experimental Open-Source Attempt to Make GPT-4 Fully Autonomous. https://github.com/Torantulino/Auto-GPT, 2023.

- Shinn, N.; Wang, X.; Radev, D. Reflexion: Language Agents with Verbal Reinforcement Learning. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2303.11366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Li, J.; Yang, K.; et al. Camel: Communicative Agents for Mind Exploration of Large Scale Language Model Society. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2303.17760. [Google Scholar]

- Park, J.S.; O’Brien, J.; Cai, C.J.; et al. Generative Agents: Interactive Simulacra of Human Behavior. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2304.03442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Dong, L.; Cheng, H.; Liu, X.; Yan, X.; Gao, J.; Wei, F. Augmenting Language Models with Long-Term Memory. Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS), arXiv 2023, arXiv:2306.07174. [Google Scholar]

- Koubaa, A. The Rise of Autonomous Intelligence with Agentic AI. In Proceedings of the Alfaisal University Presentation; 2025. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).