Submitted:

21 July 2025

Posted:

22 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

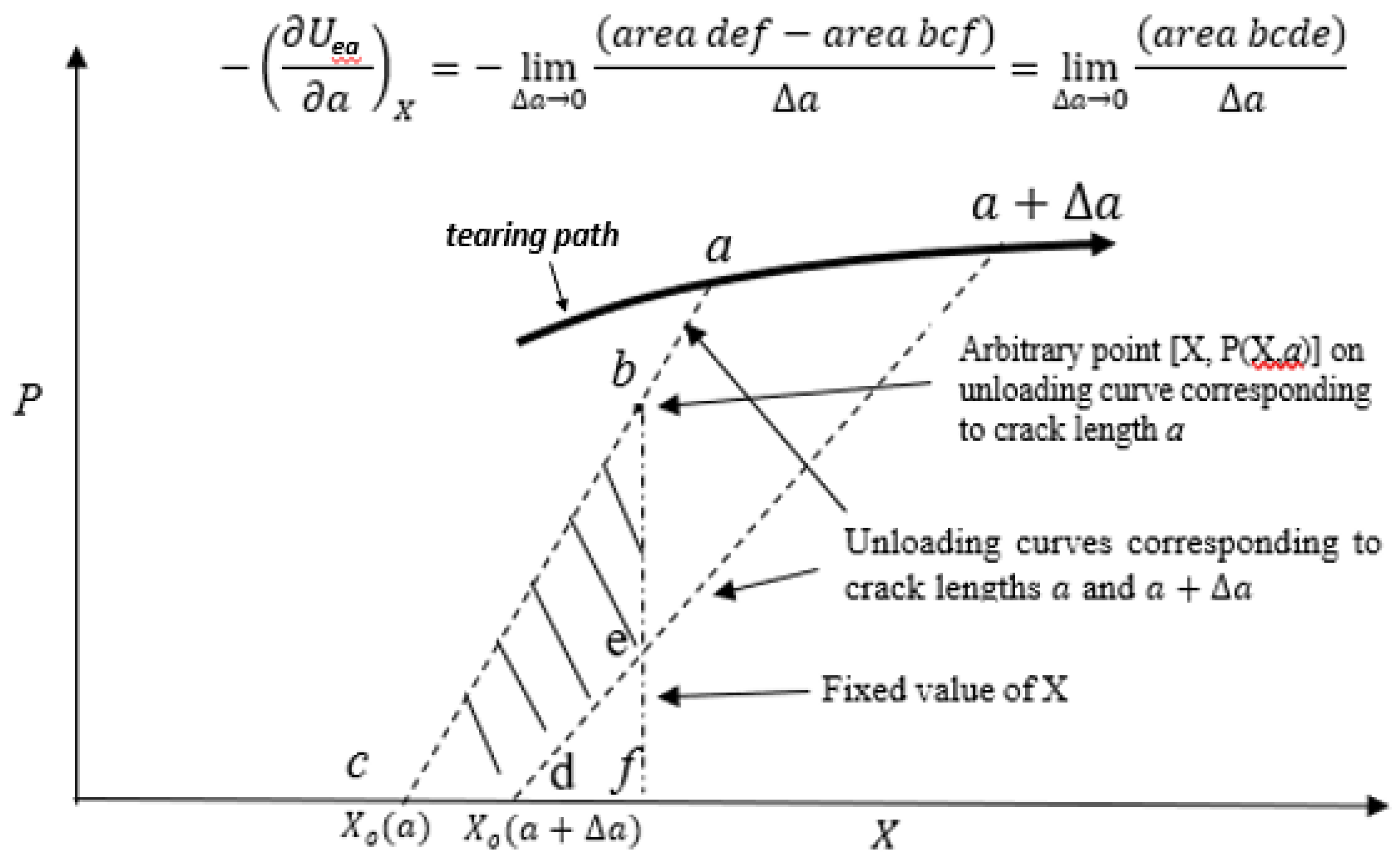

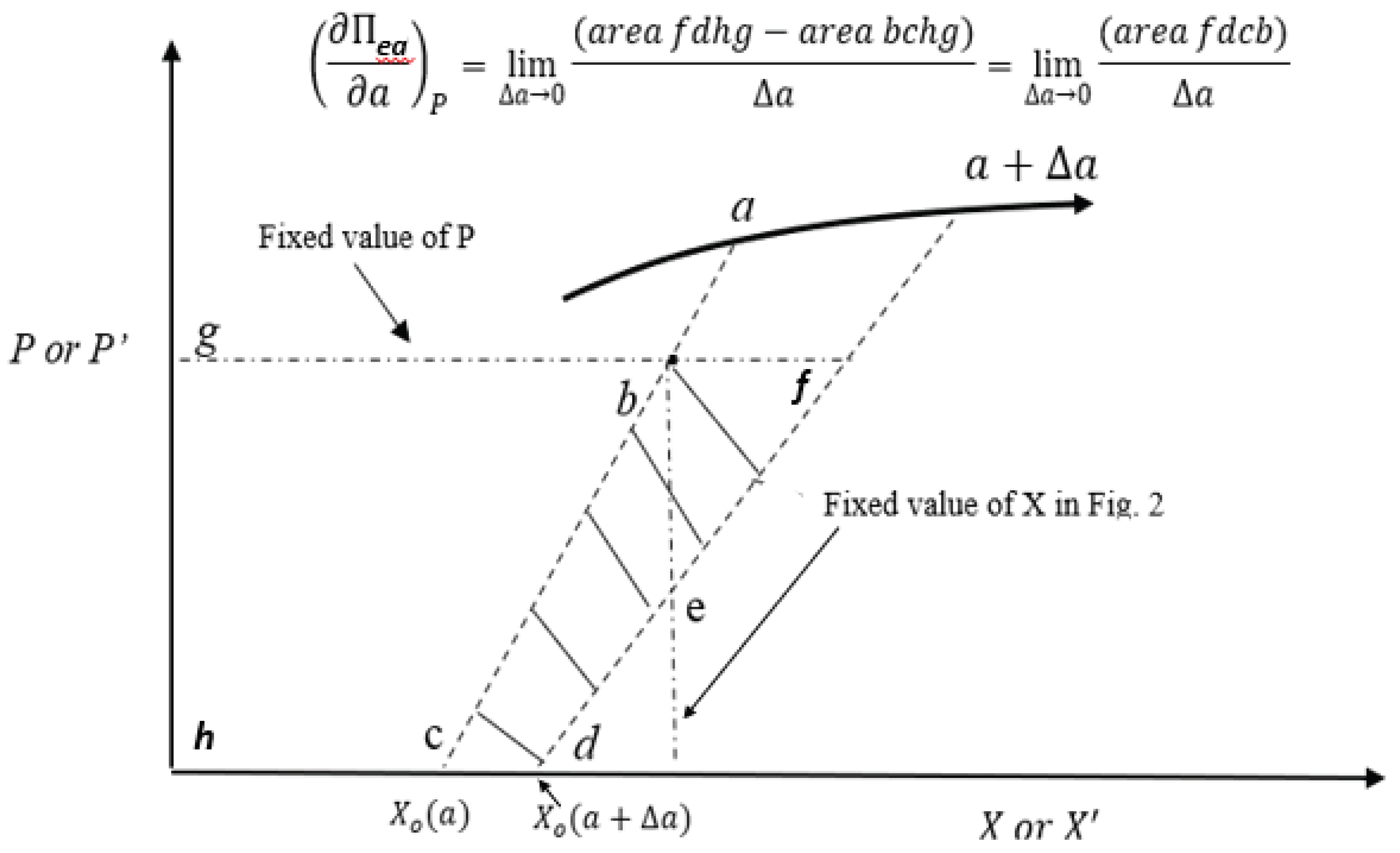

2. Derivation of (4) and Associated Instability Conditions from the Definitions of C, D and I

2.1. Definition and Derivative Properties of the Unloading Compliance Function

2.2. Definition of the Energy Dissipation Rate Function D*(a) and Associated Properties

2.3. Tearing Criterion Implicit in (16) and (20)

2.4. Analysis of Stability Conditions

2.4.1. Stability of Fracture Toughening Systems

2.4.2. Stability of Fracture Weakening Systems

3. Thermodynamic Formulation of Elastic-Plastic Tearing Processes

3.1. Conventions

3.2. State Functions and Internal Variables

3.3. First and Second Laws of Thermodynamics and Resulting Constraints on State Functions

3.4. Indeterminacy of Helmholtz Energy and Transformation of (42) to a Determinate Form

3.5. Application of Thermodynamic Criterion (48) to Fully Elastic Fracture

3.6. Stability Conditions Associated with Thermodynamic Criterion (48)

3.7. Consistency of Irwin’s Elastic-Plastic Tearing Criterion (2) and Orowan’s Associated Instability Criterion (3) with Thermodynamic Constraint (48)

3.8. Implications Regarding Significance of the Energy Dissipation Rate D*

4. Summary and Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Irwin, G.R. Fracture Dynamics. In Fracturing of Metals, Am. Soc. for Metals. 1948. pp.147-166.

- Griffith, A.A. VI. The phenomena of rupture and flow in solids. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. A 1921, 221, 163–198. [Google Scholar]

- Orowan, E. Fracture and Strength of Solids. Reports on Progress in Physics 1948, 12, 185–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orowan, E. Energy criteria of fracture. Welding Jour. Res. Supp. 1955, 20, 157s–160s. [Google Scholar]

- Orowan, E. Condition of High-Velocity Ductile Fracture. J. Appl. Phys. 1955, 26, 900–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, J. Inelastic constitutive relations for solids: An internal-variable theory and its application to metal plasticity. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 1971, 19, 433–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, R.; Rice, J.R. Elastic Potentials and the Structure of Inelastic Constitutive Laws. SIAM J. Appl. Math. 1973, 25, 448–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duvarda, V. Elastoplasticity Theory; CRC Press: Boca Raton, Florida, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Maugin, G.A. The saga of internal variables of state in continuum thermo-mechanics (1893–2013). Mech. Res. Commun. 2015, 69, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irwin, G.R. Plastic zone near a crack and fracture toughness. Proc. 7th Sagamore Conf. Vol. IV: 1960; pp. 63-70.

- Malvern, L. Introduction to the mechanics of a continuous medium. Prentice-Hall. 1969.

- Atkins, A.G.; Mai, Y.W. Residual strain energy in elastoplastic adhesive and cohesive fracture. Int. J. Fract. 1986, 30, 203–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coules, H.; Horne, G.; Venkata, K.A.; Pirling, T. The effects of residual stress on elastic-plastic fracture propagation and stability. Mater. Des. 2018, 143, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherepanov, G. Crack propagation in continuous media. J. Appl. Math. Mech. 1967, 31, 503–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, J.R. A Path Independent Integral and the Approximate Analysis of Strain Concentration by Notches and Cracks. J. Appl. Mech. 1968, 35, 379–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, J.R. Mathematical analysis in the mechanics of fracture. In Liebowitz, H.(ed.). Fracture – and Advanced Treatise. Vol. II. Mathematical Fundamentals. Academic Press. 1968; pp. 191-308.

- Begley, J.A.; Landes, J.D. The J-integral as fracture criterion. In Fracture Toughness, ASTM STP 514. American Society for Testing and Materials, H.T Corten editor. 1972. pp. 1-23.

- Paris, P.C. Fracture mechanics in the elastic plastic regime. In Barsom, J. (ed). Flaw Growth and Fracture. ASTM E24. American Society for Testing and Materials, 1977.

- Hutchinson, J. Singular behaviour at the end of a tensile crack in a hardening material. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 1968, 16, 13–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, J.; Rosengren, G. Plane strain deformation near a crack tip in a power-law hardening material. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 1968, 16, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Society for Testing and materials. Standard test method for measurement of fracture toughness. ASTM E1820-13. 2013.

- Saxena, A. Advanced Fracture Mechanics and Structural Integrity; Taylor & Francis: London, United Kingdom, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Watson, T.J.; Jolles, M.I. Plastic energy dissipation as a parameter to characterize crack growth. ASTM 1986, 905, 542–555. [Google Scholar]

- Memhard, D.; Brocks, W.; Fricke, S. Characterization of ductile tearing resistance by an energy dissipation rate. Fatigue Fract. Eng. Mater. Struct. 1993, 16, 1109–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, C.E.; Kolednie, O. A micro and macro approach to the energy dissipation rate model of stable ductile crack growth. Fatigue Fract. Eng. Mater. Struct. 1994, 17, 1089–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, C.E.; Kolednik, O. Application of energy dissipation rate arguments to stable crack growth. Fatigue Fract. Eng. Mater. Struct. 1994, 17, 1109–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, C.E.; Kolednik, O. A simple test method for energy dissipation rate, CTOA and the study of size and transferability effects for large amounts of ductile crack growth Fatigue Fract. Engng. Mater. Struct. 1994, 17, 1507–1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolednik, O.; Turner, C.E. Application of energy dissipation rate arguments to ductile instability. Fatigue Fract. Eng. Mater. Struct. 1994, 17, 1129–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolednik, O.; Shan, G.X.; Fischer, F.D. The energy dissipation rate – a new tool to interpret geometry and size effects. ASTM STP 1997, 1296, 126–151. [Google Scholar]

- Siegmund, T.; Brocks, W. A numerical study on the correlation between the work of separation and the dissipation rate in ductile fracture. Eng. Fract. Mech. 2000, 67, 139–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumpter, J. The energy dissipation rate approach to tearing instability. Eng. Fract. Mech. 2004, 71, 17–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumpter, J. Size effects in tearing instability: An analysis based on energy dissipation rate. Eng. Fract. Mech. 2007, 74, 2352–2374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumpter, J.D.G.; Turner, C.E. Use of the J Contour Integral in Elastic-Plastic Fracture Studies by Finite-Element Methods. J. Mech. Eng. Sci. 1976, 18, 97–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, C.E. Determination of stable and unstable crack growth in the elastic plastic regime in terms of Jr resistance curves. Fracture Mechanics, ASTM STP 677. In Smith, C.W. (ed) American Society for Testing and Materials. 1979. pp. 614-628.

- Irwin, G.R. Analysis of Stresses and Strains Near the End of a Crack Traversing a Plate. J. Appl. Mech. 1957, 24, 361–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, V.A. Energy criterion implicit in the definitions of the energy dissipation rate, unloading compliance, and elastic unloading energy functions. Proc. 17th Int. Conf. Exp. Mech, Rhodes, Greece, July 2-7, 2016. 2 July.

- Anderson, T.L. Fracture mechanics. CRC Press, Boca Raton, FLA. 2017.

- Rice, J.R. Continuum mechanics and thermodynamics of plasticity in relation to microscale deformation mechanisms. In Argon, S. (ed.) Constitutive relations in plasticity. MIT Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts. 1975.

- Gibbs, J.W. On the equilibrium of heterogeneous substances. Collected works of J.Willard Gibbs. Vol. I. Thermodynamics. Dover. 1875. [CrossRef]

- Rice, J. Thermodynamics of the quasi-static growth of Griffith cracks. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 1978, 26, 61–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Maugin, G. The Thermomechanics of Nonlinear Irreversible Behaviors; World Scientific Pub Co Pte Ltd: Singapore, Singapore, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Kimura, M.; Takaishi, T.; Alfat, S.; Nakano, T.; Tanaka, Y. Irreversible phase field models for crack growth in industrial applications: thermal stress, viscoelasticity, hydrogen embrittlement. SN Appl. Sci. 2021, 3, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, A.; Rule, J.; Moore, J.; Sottos, N.; White, S. Life extension of self-healing polymers with rapidly growing fatigue cracks. J. R. Soc. Interface 2007, 4, 395–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Truesdell, C.; Baierlein, R. Rational Thermodynamics. Am. J. Phys. 1985, 53, 1020–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).