Submitted:

20 July 2025

Posted:

22 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Constitutive Model

Asymptotic Behavior of the Model for Steady-State and Transient Shear Flow

3. Results and Discussion

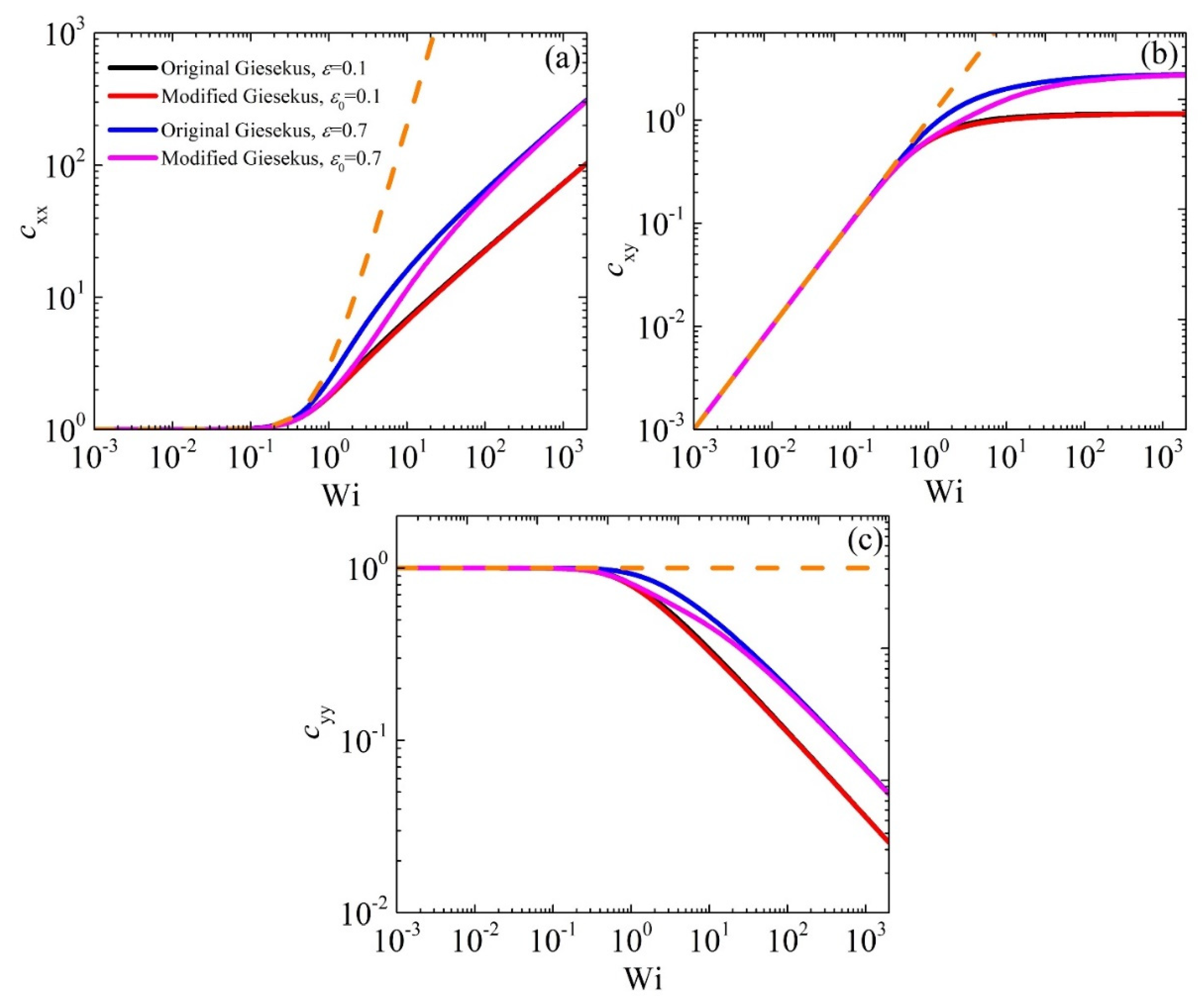

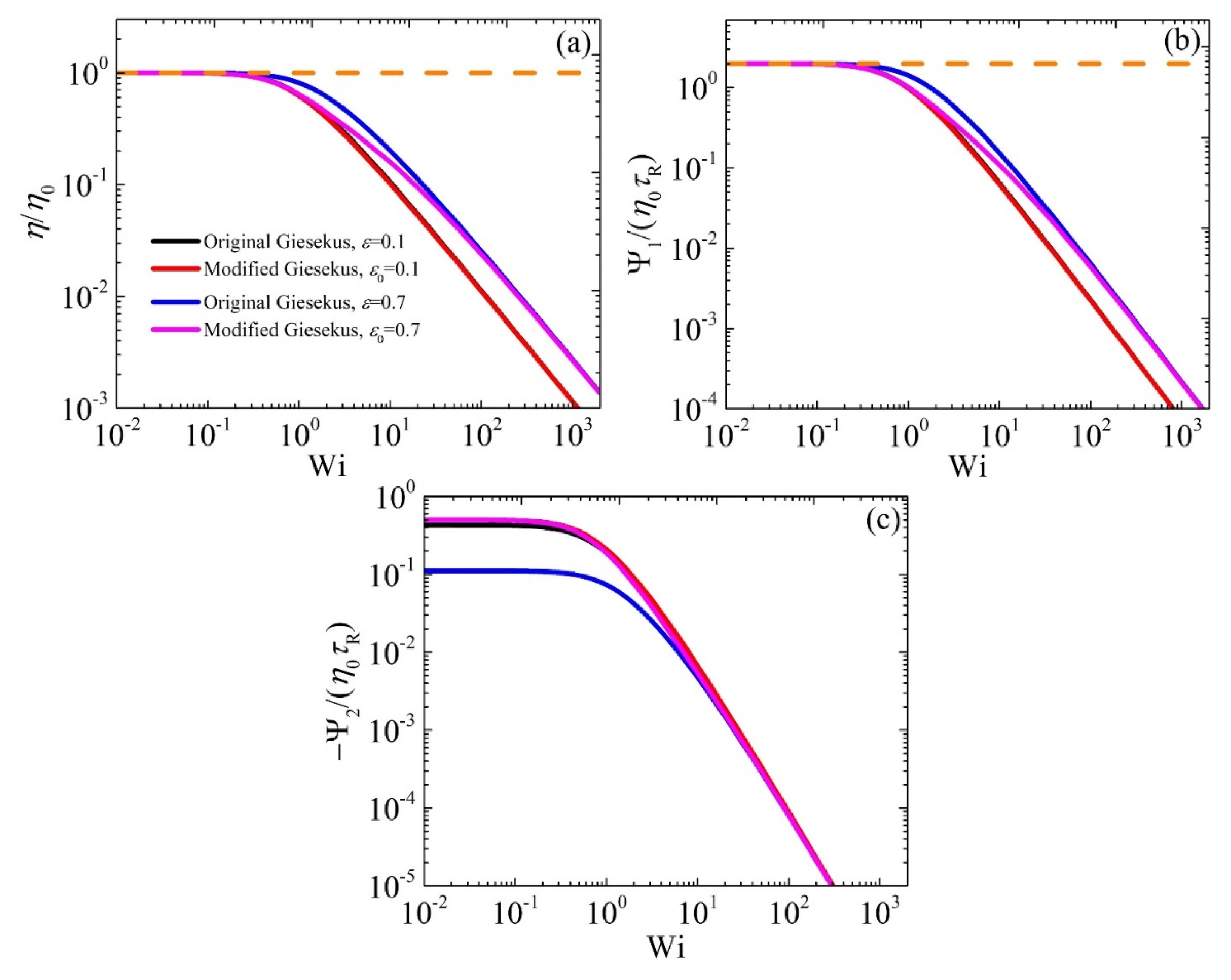

3.1. Model Predictions in Steady-State Shear Flow

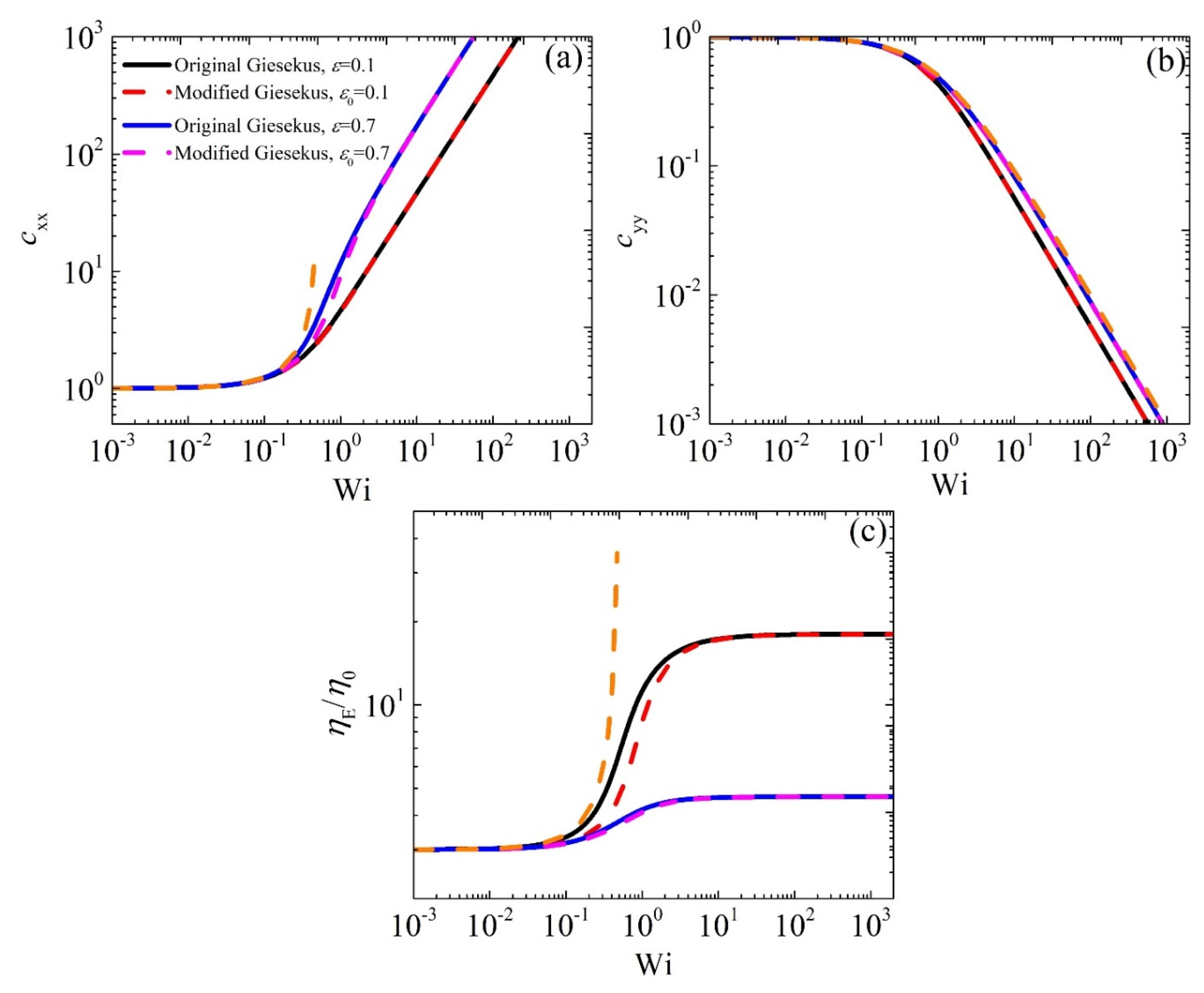

3.2. Model Predictions in Steady-State Uniaxial Elongational Flow

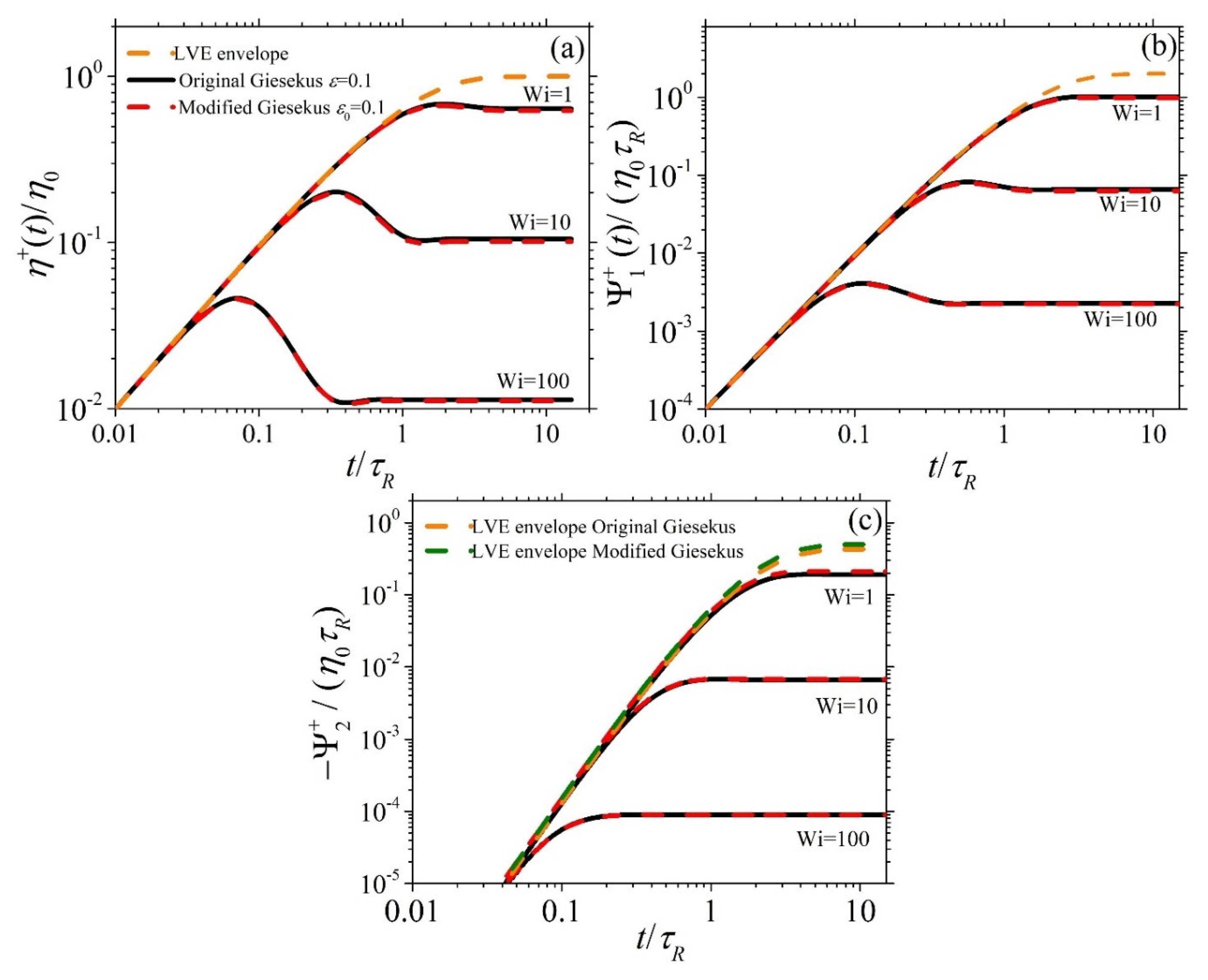

3.3. Model Predictions in Start-Up Shear Flow

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Graham, M.D. The Sharkskin Instability of Polymer Melt Flows. Chaos 1999, 9, 154–163. [CrossRef]

- Tadmor, Z.; Gogos, C.G. Principles of Polymer Processing; 2nd Editio.; Wiley-Interscience: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2006; ISBN 978-0-471-38770-1.

- Germann, N. Preface to Special Topic: One Hundred Years of Giesekus. Phys. Fluids 2024, 36, 050401.

- Larson, R.G. The Structure and Rheology of Complex Fluids; Oxford University Press: New York, United States, 1999; ISBN 9780195121971.

- Larson, R.G. Constitutive Equations for Polymer Melts and Solutions; 1st ed.; Butterworth-Heinemann, 1988; ISBN 978-0-409-90119-1.

- Bird, R.B.; Armstrong, R.C.; Hassager, O. Dynamics of Polymeric Liquids. Volume 1. Fluid Mechanics.; 2nd Editio.; Wiley-Interscience, 1987; ISBN 047107375X.

- Tanner, R.I. Engineering Rheology; 2nd ed.; Oxford Engineering Science Series, 2002; ISBN 9780198564737.

- Giesekus, H. Stressing Behaviour in Simple Shear Flow as Predicted by a New Constitutive Model for Polymer Fluids. J. Nonnewton. Fluid Mech. 1983, 12, 367–374. [CrossRef]

- Giesekus, H. On Configuration-Dependent Generalized Oldroyd Derivatives. J. Nonnewton. Fluid Mech. 1984, 14, 47–65. [CrossRef]

- Bird, R.B.; Curtiss, F.C.; Amstrong, C.R.; Ole, H. Dynamics of Polymeric Liquids, Second Edition Volume 2: Kinetic Theory; Wiley-Interscience, 1987; ISBN 978-0-471-80244-0.

- Curtiss, C.F.; Byron Bird, R. A Kinetic Theory for Polymer Melts. I. The Equation for the Single-Link Orientational Distribution Function. J. Chem. Phys. 1980, 74, 2016–2025. [CrossRef]

- Curtiss, C.F.; Byron Bird, R. A Kinetic Theory for Polymer Melts. II. The Stress Tensor and the Rheological Equation of State. J. Chem. Phys. 1980, 74, 2026–2033. [CrossRef]

- Giesekus, H. A Simple Constitutive Equation for Polymer Fluids Based on the Concept of Deformation-Dependent Tensorial Mobility. J. Nonnewton. Fluid Mech. 1982, 11, 69–109. [CrossRef]

- Stephanou, P.S.; Schweizer, T.; Kröger, M. Communication: Appearance of Undershoots in Start-up Shear: Experimental Findings Captured by Tumbling-Snake Dynamics. J. Chem. Phys. 2017, 146, 161101. [CrossRef]

- Stephanou, P.S.; Kröger, M. Non-Constant Link Tension Coefficient in the Tumbling-Snake Model Subjected to Simple Shear. J. Chem. Phys. 2017, 147, 174903. [CrossRef]

- Stephanou, P.S.; Baig, C.; Mavrantzas, V.G. A Generalized Differential Constitutive Equation for Polymer Melts Based on Principles of Nonequilibrium Thermodynamics. J. Rheol. 2009, 53, 309–337. [CrossRef]

- Kröger, M. Models for Polymeric AndAnisotropic Liquids; Springer-Verlag: Berlin Heidelberg, 2005; ISBN 978-3-540-26210-7.

- Beris, A.N.; Edwards, B.J. Thermodynamics of Flowing Systems: With Internal Microstructure; Oxford University Press: New York, 1994; ISBN 019507694X.

- Nikiforidis, V.-M.; Tsalikis, D.G.; Stephanou, P.S. On The Use of a Non-Constant Non-Affine or Slip Parameter in Polymer Rheology Constitutive Modeling. Dynamics 2022, 2, 380–398. [CrossRef]

- Stephanou, P.S.; Tsimouri, I.C.; Mavrantzas, V.G. Simple, Accurate and User-Friendly Differential Constitutive Model for the Rheology of Entangled Polymer Melts and Solutions from Nonequilibrium Thermodynamics. Materials (Basel). 2020, 13, 2867. [CrossRef]

- Costanzo, S.; Huang, Q.; Ianniruberto, G.; Marrucci, G.; Hassager, O.; Vlassopoulos, D. Shear and Extensional Rheology of Polystyrene Melts and Solutions with the Same Number of Entanglements. Macromolecules 2016, 49, 3925–3935. [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.M.; Baig, C. Precise Analysis of Polymer Rotational Dynamics. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 19127. [CrossRef]

- Nafar Sefiddashti, M.H.; Edwards, B.J.; Khomami, B. Individual Chain Dynamics of a Polyethylene Melt Undergoing Steady Shear Flow. J. Rheol. 2015, 59, 119–153. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).