Submitted:

19 July 2025

Posted:

22 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature review

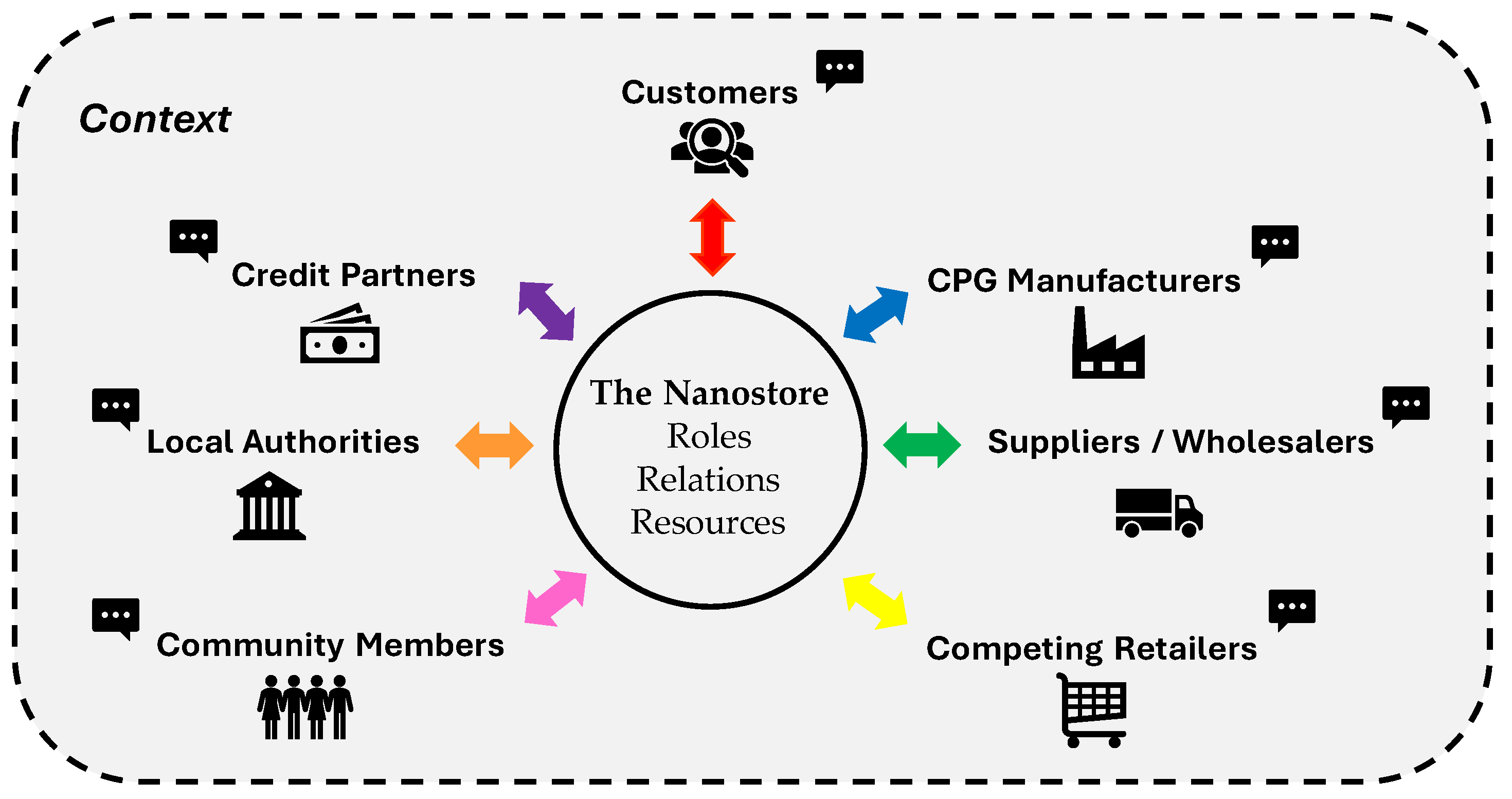

2.1. Nanostores as purposeful systems

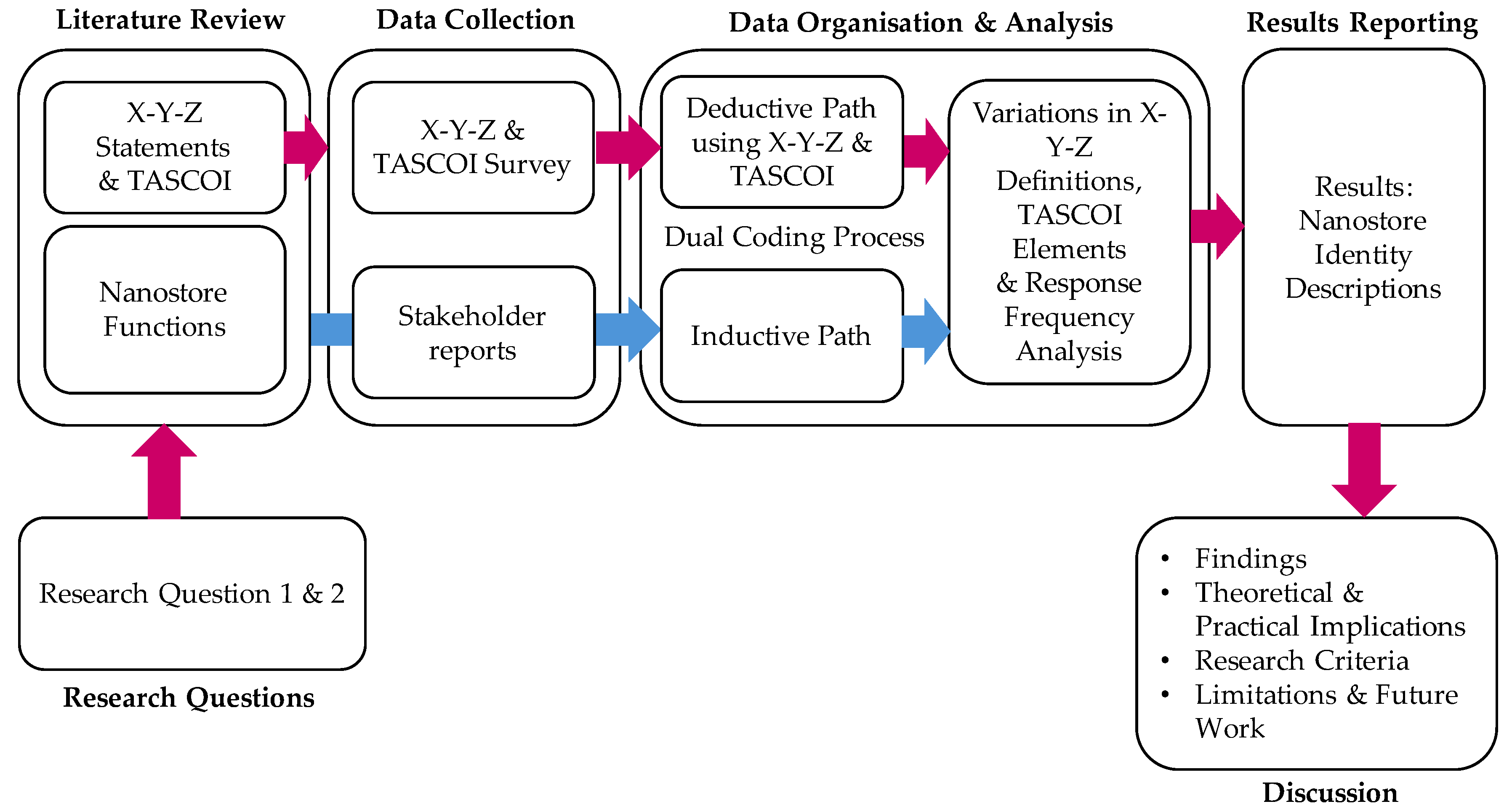

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Design

3.1.1. Data Collection

3.1.2. Data Organisation and Analysis

3.1.3. Results Reporting and Discussion

4. Results

4.1. Identity Statement Descriptions by Stakeholders

4.1.1. Categorisation of “X”—What the nanostore does.

4.1.2. Categorisation of “Y”—How the nanostore functions.

4.1.3. Categorisation of “Z”—Purpose of nanostores (Why it matters).

4.2. X-Y-Z Identity Descriptions of the Nanostore: Patterns, Alternatives, and Significance

4.3. A Systemic View of the Nanostore: Integrating TASCOI with X, Y, Z, and Transformation Variations

5. Discussion

5.1. Findings

5.1.1. Findings on Identity Statements and the TASCOI Tool.

5.1.2. Findings on Nanostore Identity and Transformation

5.2. Implications

5.2.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2.2. Practical Implications

5.3. A Discussion on Validity, Reliability, Transferability, and Generalisability

5.4. Limitations and Future Work

5.4.1. Limitations

5.4.2. Future Research

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| RQ | Research Question |

| X-Y-Z | What they do (X), how they function (Y), and why they matter (Z), |

| TASCOI | Transformation, Actors, Suppliers, Customers, Owners, and Interveners) |

Appendix A: Survey Questionnaire

Section A

- Identify the type of stakeholder to be interviewed (e.g., actor, supplier, client, owner, or intervenor).

- Describe the key characteristics and attributes of the selected stakeholder.

- What is the stakeholder’s specific role within the store?

- In what ways does the stakeholder regularly interact with the nanostore?

- What makes this stakeholder particularly important or relevant to the nanostore’s operations?

- What specific tasks or activities does the stakeholder perform in or in collaboration with the nanostore?

Section B

- What are the stakeholders’ expectations, needs, requirements, or preferences regarding the nanostore and its operations?

- How does the stakeholder assess their relationship with the nanostore?

Section C

- Do “X” (What they do): What does the nanostore do? What are the nanostore’s primary activities?

- Through “Y” (How they function): How does the nanostore conduct its operations? What resources and processes are used to operate?

- With the purpose of “Z” (Why they matter): What is the underlying purpose? Why does it matter?

- Transformation: Which inputs are converted into which outputs in the nanostore? What are the key nanostore processes carried out?

- Actors: Who performs the nanostore activities?

- Suppliers: Who supplies/inputs the products that the nanostore sells?

- Customers/Beneficiaries: Who benefits from (or is affected by) the activities conducted by the nanostore? In what ways?

- Owner: Who is responsible for the nanostore operation? And how?

- Interveners: Who shapes the broader context? Who, from the outside, provides the nanostore with the context for its functioning and operation?

References

- Fransoo, J.C.; Blanco, E.; Mejia-Argueta, C. Reaching 50 Million Nanostores: Retail Distribution in Emerging Megacities; CreateSpace Independent Publisher Platform, 2017; ISBN 978-1-9757-4200-3.

- Boulaksil, Y.; Fransoo, J.; Koubida, S. Small Traditional Retailers in Emerging Markets. BETA publicatie: working papers; Vol. 460. Technische Universiteit Eindhoven. 2014.

- D’Andrea, G.; Lopez-Aleman, B.; Stengel, A. Why Small Retailers Endure in Latin America. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management 2006, 34, 661–673. [CrossRef]

- Escamilla González Aragón, R.; C. Fransoo, J.; Mejía Argueta, C.; Velázquez Martínez, J.; Gastón Cedillo Campos, M. Nanostores: Emerging Research in Retail Microbusinesses at the Base of the Pyramid. Academy of Management Global Proceedings 2020, 161.

- Paswan, A.; Pineda, M. de los D.S.; Ramirez, F.C.S. Small versus Large Retail Stores in an Emerging Market—Mexico. Journal of Business Research 2010, 63, 667–672. [CrossRef]

- Ortega-Jimenez, C.H.; Amador-Matute, A.M.; Parada-Lopez, J.S. Logistics and Information Technology: A Systematic Literature Review of Nanostores from 2014 to 2023. In Proceedings of the 21st LACCEI International Multi-Conference for Engineering, Education and Technology (LACCEI 2023): “Leadership in Education and Innovation in Engineering in the Framework of Global Transformations: Integration and Alliances for Integral Development”; Latin American and Caribbean Consortium of Engineering Institutions, 2023.

- Coen, S.E.; Ross, N.A.; Turner, S. “Without Tiendas It’s a Dead Neighbourhood”: The Socio-Economic Importance of Small Trade Stores in Cochabamba, Bolivia. Cities 2008, 25, 327–339. [CrossRef]

- Kinlocke, R.; Thomas-Hope, E. Characterisation, Challenges and Resilience of Small-Scale Food Retailers in Kingston, Jamaica. Urban Forum 2019, 30, 477–498. [CrossRef]

- Rangel-Espinosa, M.F.; Hernández-Arreola, J.R.; Pale-Jiménez, E.; Salinas-Navarro, D.E.; Mejía Argueta, C. Increasing Competitiveness of Nanostore Business Models for Different Socioeconomic Levels. In Supply Chain Management and Logistics in Emerging Markets; Yoshizaki, H.T.Y., Mejía Argueta, C., Mattos, M.G., Eds.; Emerald Publishing Limited, 2020; pp. 273–298 ISBN 978-1-83909-333-3.

- Espejo, R. Aspects of Identity, Cohesion, Citizenship and Performance in Recursive Organisations. Kybernetes 1999, 28, 640–658. [CrossRef]

- Baron, S.; Harris, K.; Leaver, D.; Oldfield, B.M. Beyond Convenience: The Future for Independent Food and Grocery Retailers in the UK. The International Review of Retail, Distribution and Consumer Research 2001, 11, 395–414. [CrossRef]

- Ortega-Jiménez, C.H.; Amador-Matute, A.; Parada López, J.; Zavala-Fuentes, D.; Sevilla, S. A Meta-Analysis of Nanostores: A 10-Year Assessment. In Proceedings of the 2nd LACCEI International Multiconference on Entrepreneurship, Innovation and Regional Development (LEIRD 2022): “Exponential Technologies and Global Challenges: Moving toward a new culture of entrepreneurship and innovation for sustainable development”; Latin American and Caribbean Consortium of Engineering Institutions, 2022.

- Pathak, A.A.; Kandathil, G. Strategizing in Small Informal Retailers in India: Home Delivery as a Strategic Practice. Asia Pac J Manag 2020, 37, 851–877. [CrossRef]

- Salinas-Navarro, D.E.; Vilalta-Perdomo, E.; Michel-Villarreal, R. Empowering Nanostores for Competitiveness and Sustainable Communities in Emerging Countries: A Generative Artificial Intelligence Strategy Ideation Process. Sustainability 2024, 16, 11244. [CrossRef]

- Everts, J. Consuming and Living the Corner Shop: Belonging, Remembering, Socialising. Social & Cultural Geography 2010, 11, 847–863. [CrossRef]

- Espejo, R. What Is Systemic Thinking? System Dynamics Review (Wiley) 1994, 10, 199–212.

- Beer, S. Diagnosing the System for Organizations; Classic Beer Series; Wiley, 1985; ISBN 978-0-471-90675-9.

- Espejo, R.; Bowling, D.; Hoverstadt, P. The Viable System Model and the Viplan Software. Kybernetes 1999, 28, 661–678. [CrossRef]

- Self-Organization and Management of Social Systems: Insights, Promises, Doubts, and Questions; Ulrich, H., Probst, G., Eds.; Springer series in synergetics; Springer-Verlag: Berlin; New York, 1984; ISBN 978-0-387-13459-8.

- Checkland, P.; Scholes, J. Soft Systems Methodology: A 30-Year Retrospective; New ed.; Wiley: Chichester, Eng.; New York, 1999; ISBN 978-0-471-98605-8.

- Granados-Rivera, D.; Mejía, G.; Tinjaca, L.; Cárdenas, N. Design of a Nanostores’ Delivery Service Network for Food Supplying in COVID-19 Times: A Linear Optimization Approach. In Production Research; Rossit, D.A., Tohmé, F., Mejía Delgadillo, G., Eds.; Communications in Computer and Information Science; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2021; Vol. 1408, pp. 19–32 ISBN 978-3-030-76309-1.

- Salinas-Navarro, D.E.; Alanis-Uribe, A.; da Silva-Ovando, A.C. Learning Experiences about Food Supply Chains Disruptions over the Covid-19 Pandemic in Metropolis of Latin America. In Proceedings of the 2021 IISE Annual Conference; Ghate, A., Krishnaiyer, K., Paynabar, K., Eds.; Institute of Industrial and Systems Engineers (IISE): Norcross, GA, USA, 2021; pp. 495–500.

- Haboush-Deloye, A.L.; Knight, M.A.; Bungum, N.; Spendlove, S. Healthy Foods in Convenience Stores: Benefits, Barriers, and Best Practices. Health Promotion Practice 2023, 24, 108S-111S. https://doi.org/10.1177/15248399221147878.

- Salinas, D.; Fransoo, J.; Mejia-Argueta, C.; Benitez, V. Food Logistics. October 19 2018.

- Ochoa, A.F.; Duarte, M.G.; Bueno, L.A.S.; Salas, B.V.; Alpírez, G.M.; Wiener, M.S. Systemic Analysis of Supermarket Solid Waste Generation in Mexicali, Mexico. JEP 2010, 01, 105–110. https://doi.org/10.4236/jep.2010.12013.

- Hidalgo-Carvajal, D.; Gutierrez-Franco, E.; Mejia-Argueta, C.; Suntura-Escobar, H. Out of the Box: Exploring Cardboard Returnability in Nanostore Supply Chains. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7804. [CrossRef]

- Bocken, N.M.P.; Short, S.W.; Rana, P.; Evans, S. A Literature and Practice Review to Develop Sustainable Business Model Archetypes. Journal of Cleaner Production, 2014, 65, 42–56. [CrossRef]

- Ram, M.; Theodorakopoulos, N.; Worthington, I. Policy Transfer in Practice: Implementing Supplier Diversity in the UK. Public Administration 2007, 85, 779–803. [CrossRef]

- Corner, P.D.; Pavlovich, K. Shared Value Through Inner Knowledge Creation. J Bus Ethics 2016, 135, 543–555. [CrossRef]

- Giddens, A. The Constitution of Society: Outline of the Theory of Structuration; First paperback edition.; University of California Press: Berkeley, Los Angeles, 1986; ISBN 978-0-520-05728-9.

- Beer, S. Decision and Control : The Meaning of Operational Research and Management Cybernetics; Stafford Beer Classic Library; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: UK, 1994; ISBN 978-0-471-94838-4.

- Salinas-Navarro, D.E. Performance in Organisations, An Autonomous Systems Approach; Lambert Academic Publishing: Saarbrücken, Germany, 2010; ISBN 978-3-8383-4887-2.

- Espejo, R. Self-construction of Desirable Social Systems. Kybernetes 2000, 29, 949–963. [CrossRef]

- Argyris, C.; Schön, D.A. Organizational Learning II: Theory, Method, and Practice; Addison-Wesley series on organizational development; Nachdr.; Addison-Wesley: Reading, Mass., 1999; ISBN 978-0-201-62983-5.

- Espejo, R. Requirements for Effective Participation in Self-Constructed Organizations. European Management Journal 1996, 14, 414–422. [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R.E.E.; McVea, J. A Stakeholder Approach to Strategic Management. SSRN Journal 2001. [CrossRef]

- Granovetter, M. Economic Action and Social Structure: The Problem of Embeddedness. American Journal of Sociology 1985, 91, 481–510.

- de Zeeuw, G. Three Phases of Science: A Methodological Exploration. Working Paper 7. Centre for Systems and Information Sciences, University of Lincolnshire and Humberside 1996, 7.

- Vahl, M. Doing Research in the Social Domain. In Systems for Sustainability; Stowell, F.A., Ison, R.L., Armson, R., Holloway, J., Jackson, S., McRobb, S., Eds.; Springer US: Boston, MA, 1997; pp. 147–152 ISBN 978-1-4899-0267-2.

- Hoffmann, V.; Doan, M.K.; Harigaya, T. Self-Selection versus Population-Based Sampling for Evaluation of an Agronomy Training Program in Uganda. Journal of Development Effectiveness 2024, 16, 375–385. [CrossRef]

- Stratton, S.J. Population Research: Convenience Sampling Strategies. Prehosp. Disaster med. 2021, 36, 373–374. [CrossRef]

- Birt, L.; Scott, S.; Cavers, D.; Campbell, C.; Walter, F. Member Checking: A Tool to Enhance Trustworthiness or Merely a Nod to Validation? Qual Health Res 2016, 26, 1802–1811. [CrossRef]

- Mora-Quiñones, C.; Cárdenas-Barrón, L.; Velázquez-Martínez, J.; Karla Gámez-Pérez The Coexistence of Nanostores within the Retail Landscape: A Spatial Statistical Study for Mexico City. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10615. [CrossRef]

- Guest, G.; MacQueen, K.; Namey, E. Applied Thematic Analysis; SAGE Publications, Inc.: 2455 Teller Road, Thousand Oaks, California 91320 United States, 2012; ISBN 978-1-4129-7167-6.

- Saunders, M.N.K.; Lewis, P.; Thornhill, A. Research Methods for Business Students; 9th ed.; Financial Times/Prentice Hall: Harlow, England; New York, 2007; ISBN 978-0-273-70148-4.

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology 2006, 3, 77–101. [CrossRef]

- Salinas-Navarro, D.E. Nanostore Identity Exploration Mexico City 2021-Semester 01 2025.

- Organisational Fitness: Corporate Effectiveness through Management Cybernetics; Espejo, R., Schwaninger, M., Eds.; Campus-Verl: Frankfurt am Main, 1993; ISBN 978-3-593-34783-7.

- Espejo, R. An Enterprise Complexity Model: Variety Engineering and Dynamic Capabilities. International Journal of Systems and Society 2015, 2, 1–22. [CrossRef]

- Espejo, R.; Stewart, N.D. Systemic Reflections on Environmental Sustainability. Syst. Res. 1998, 15, 483–496. [CrossRef]

- United Nations Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; United Nations: New York, NY, 2015;

- O’Connor, C.; Joffe, H. Intercoder Reliability in Qualitative Research: Debates and Practical Guidelines. International Journal of Qualitative Methods 2020, 19. [CrossRef]

| Stakeholder Type | N | Sale of Goods | Source of Income/ Employment | Convenience/ Essential Goods | Market Rival/ Barrier | Personal Investment/ Sustenance | Community Service |

| Actors | 124 | 110 (89%) | 102 (82%) | 18 (15%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (2%) | 18 (15%) |

| Customers | 15 | 13 (87%) | 2 (13%) | 10 (67%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (13%) |

| Owner | 7 | 7 (100%) | 7 (100%) | 2 (29%) | 0 (0%) | 7 (100%) | 1 (14%) |

| Interveners | 22 | 19 (86%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (14%) | 14 (64%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (5%) |

| Stakeholder Type | N | Physical Store | Human Resources | Suppliers | Admin/ Tech Systems | Specific Tools/ Processes | Market Transactions |

| Actors | 124 | 92 (74%) | 81 (65%) | 39 (31%) | 7 (6%) | 18 (15%) | 0 (0%) |

| Owner | 7 | 6 (86%) | 5 (71%) | 7 (100%) | 3 (43%) | 2 (29%) | 0 (0%) |

| Customers | 15 | 11 (73%) | 9 (60%) | 2 (13%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (7%) | 0 (0%) |

| Interveners | 22 | 7 (32%) | 5 (23%) | 7 (32%) | 1 (5%) | 0 (0%) | 14 (64%) |

| Stakeholder Type | N | Generate Income/ Sustenance | Serve Community/ Clients | Business Growth/ Loyalty | Provide Essential Goods | Market Competition |

| Actors | 124 | 106 (85%) | 18 (15%) | 6 (5%) | 14 (11%) | 0 (0%) |

| Owner | 7 | 7 (100%) | 2 (29%) | 4 (57%) | 2 (29%) | 0 (0%) |

| Customers | 15 | 4 (27%) | 3 (20%) | 0 (0%) | 11 (73%) | 0 (0%) |

| Interveners | 22 | 15 (68%) | 1 (5%) | 0 (0%) | 5 (23%) | 7 (32%) |

| Dimension | Category (Theme) | Description | Example Responses | Frequency (approx.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| X | Retail Sales of Everyday Goods | The nanostore sells groceries, snacks, pharmacy items, stationery, and other essential products. | “Sale of consumer products such as soft drinks, ham, etc.”, “Sale of stationery products.” | ~82% |

| Source of Employment/Income | The nanostore is a workplace and the primary source of income for staff and owners. | “It's a source of employment.” “My source of income.” |

~68% | |

| Community Service/Convenience | The nanostore is valued for its accessibility, convenience, and service to the neighbourhood. | “Serve nearby customers.”, “Meet neighbourhood needs.” |

~20% | |

| Family/Personal Investment | The nanostore is seen as a family project or personal investment. | “Family project.”, “Own business.” | ~10% | |

| Market Rival/Barrier | The nanostore is seen as a competitor or obstacle in the local market. | “Direct competition.”, “It represents a barrier because it is direct competition.” | ~7% | |

| Y | Physical Store/Infrastructure | Operations depend on the physical location, premises, and tangible infrastructure. | “Through its establishment.”, “At your premises.” |

~77% |

| Human Resources/Personnel | Staff, owners, or family members carry out activities. | “Staff who attend.”, “A person who attends all day.” | ~61% | |

| Supplier Networks | The nanostore sources goods from external suppliers and brands. | “Buys products from suppliers.”, “Receives merchandise from Bimbo, Sabritas, and others.” | ~33% | |

| Operational Tools/Processes | Use of specific tools, equipment, or routines (e.g., delivery bikes, refrigerators). | “Use bicycles for delivery.”, “Cash register.” | ~18% | |

| Customer Service/Community Engagement | Focus on serving clients and engaging with the community. | “Serve customers.”, “It offers home delivery service.” | ~22% | |

| Z | Generating Income/Sustenance | The primary purpose is to provide economic benefit or financial security. | “Generate income for the family.”, “To have a livelihood.” |

~79% |

| Providing Essential Goods/Services | The purpose is to provide essential products and services to the community. | “Meet customer needs.”, “Offer basic necessities.” | ~28% | |

| Supporting Family/Personal Project | The nanostore is a family business or personal investment. | “Family project.”, “Help the family." | ~11% | |

| Serving the Community | The purpose is to contribute to or support the local community. | “Helping the community.” “To be useful to the neighbourhood.” | ~8% |

| TASCOI Role | X: What/Who (Identity & Activity) | Y: How (Means & Resources) | Z: Why (Purpose) | Example from the Dataset | Variations/Notes |

| Actors | Carry out retail, service, and logistics | Staff, owners, and family members | Seek employment, business growth, and community value | “Staff who attend all day” | These actors may include delivery staff, cashiers, and family members |

| Suppliers | Enable product variety and availability | Deliver goods, maintain supply chains | Support the store’s commercial viability | “Suppliers of each sold product” | Local vs national suppliers, reliability varies |

| Customers | Receive goods/services, define demand | Interact at the store, purchase, and give feedback | Satisfy needs, seek convenience, and community ties | “Close customers”, “People who are passing by” | Frequency, loyalty, and needs differ by segment |

| Owners | Oversee, invest, and manage | Make strategic, financial, and operational choices | Ensure family sustenance, long-term viability | “The owner... is responsible for the operation.” | Sometimes a double role as actors/owners |

| Interveners | Influence context and competition | Compete, manage, or enable operations | Shape the market, set competition norms, and provide retail infrastructure | “Direct competition”, “The government and the arrangements” | It can be positive (support) or negative (barriers) |

| X Identity (What/Who) | Transformation: Inputs → Outputs & Key Processes | Example from the Dataset | Variation/Significance |

| Retail Sales of Everyday Goods | Inventory, staff time, supplier goods → Sold products, customer satisfaction. Key processes include stocking, merchandising, sales, and checkout. | “Sale of consumer products such as soft drinks, ham, etc.” “Arrange material and sell.” |

Transformation is transactional and product-focused. |

| Source of Employment/Income | Employee labour, store infrastructure, inventory → Wages, financial stability, job satisfaction. Key processes include shift management, payroll, and customer service. | “It's a source of employment.”, “Your source of income.” |

Transformation centres on converting labour into livelihoods and security. |

| Community Service/Convenience | Access to location, product variety, staff attention → Neighbourhood convenience, social capital, trust. Key processes: extended hours, personalised service, local engagement. | “Serve nearby customers.” “Meet neighbourhood needs.” |

Transformation emphasises the social value and accessibility over pure sales. |

| Family/Personal Investment | Family labour, personal capital, shared responsibilities → Family income, business experience, generational skills. Key processes include joint decision-making, intergenerational training, and flexible roles. | “Family project.”, “Own business.” | Transformation integrates economic and family/social outcomes. |

| Market Rival/Barrier | Competitive pricing, product selection, marketing efforts → Market share, customer retention, barriers to entry for others. Key processes include monitoring competitors, conducting promotional activities, and adjusting the product mix. | “Direct competition.”, “It represents a barrier because it is direct competition.” | External market dynamics and the level of competition shape the transformation. |

| Dimension | For Management & Problem Solving | For Decision Making & Policy |

| X | Identify core and alternative roles; diversify offerings; strengthen identity as an employer, service provider, or family asset. | Design and deploy support programmes that reflect nanostores’ social and economic functions and impact on their communities. |

| Y | Improve resource utilisation and processes; invest in infrastructure, staff development, and supplier relations; adopt relevant technology. | Set standards for fair, efficient, reliable supply chains, labour, and infrastructure support. |

| Z | Align goals with stakeholder needs (income, service, family, community); measure performance beyond sales. | Develop policies for microenterprise income stability, social impact, and local access. Ensure product availability, accessibility, and affordability. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).