Submitted:

21 July 2025

Posted:

22 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

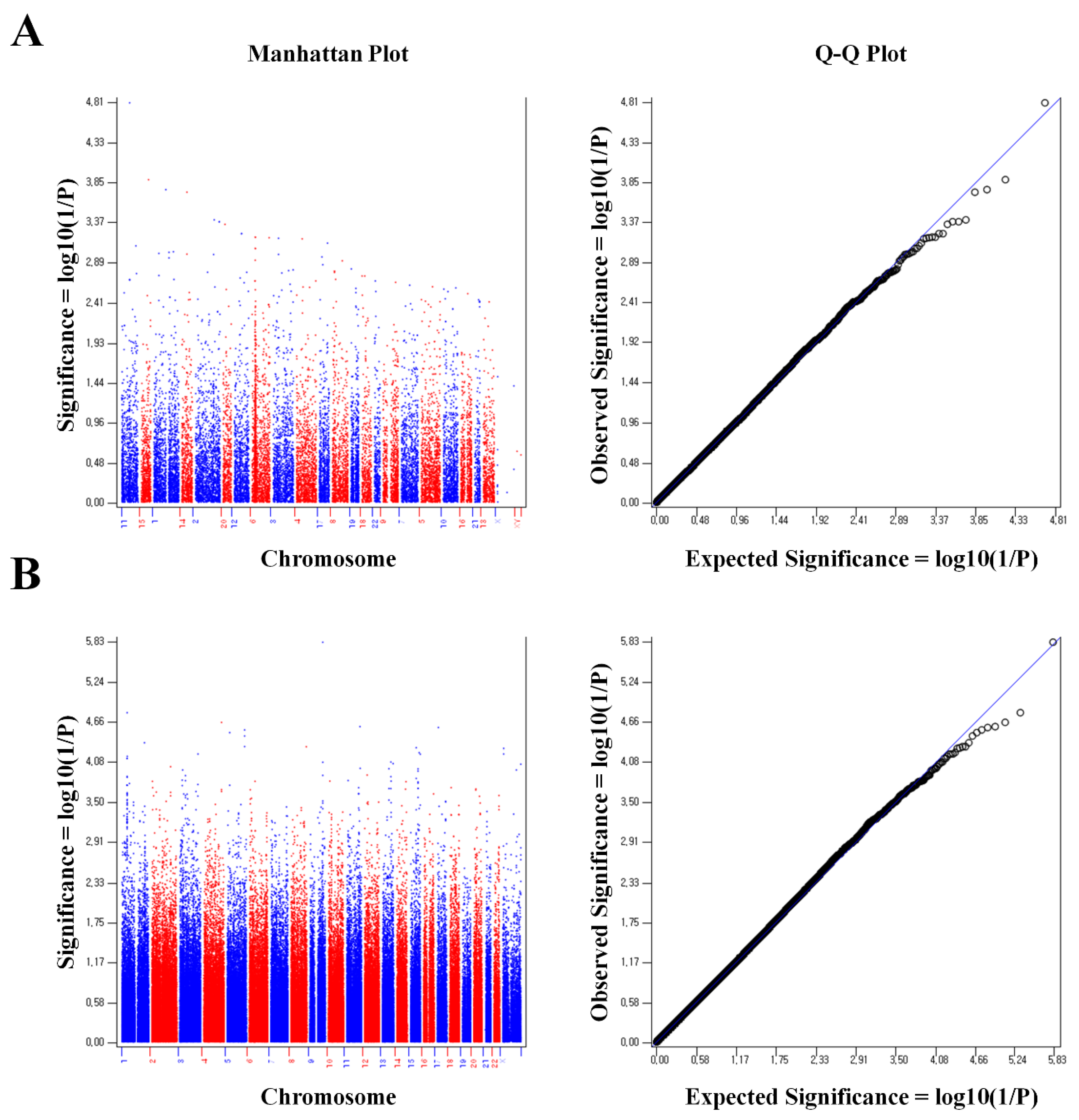

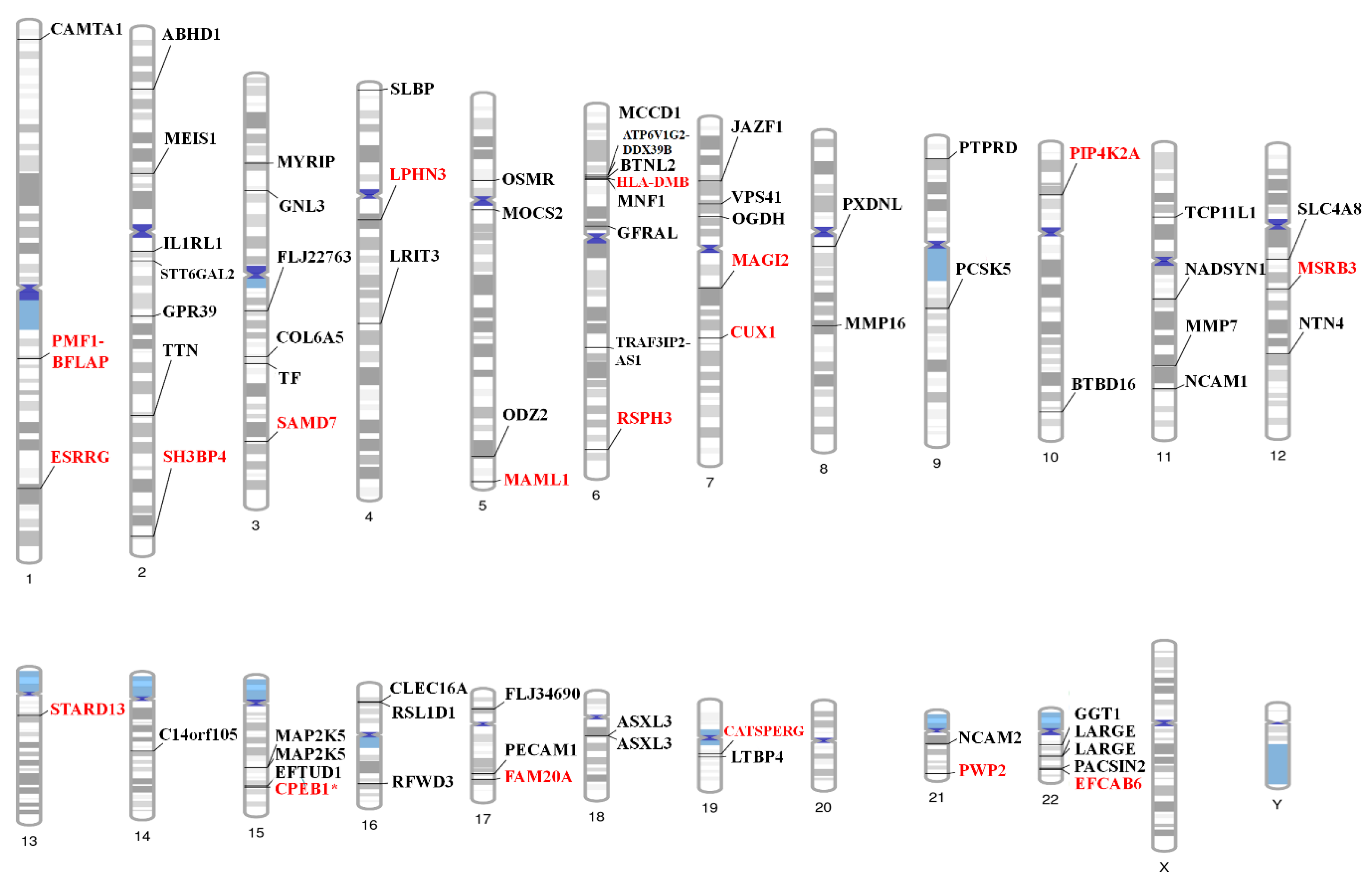

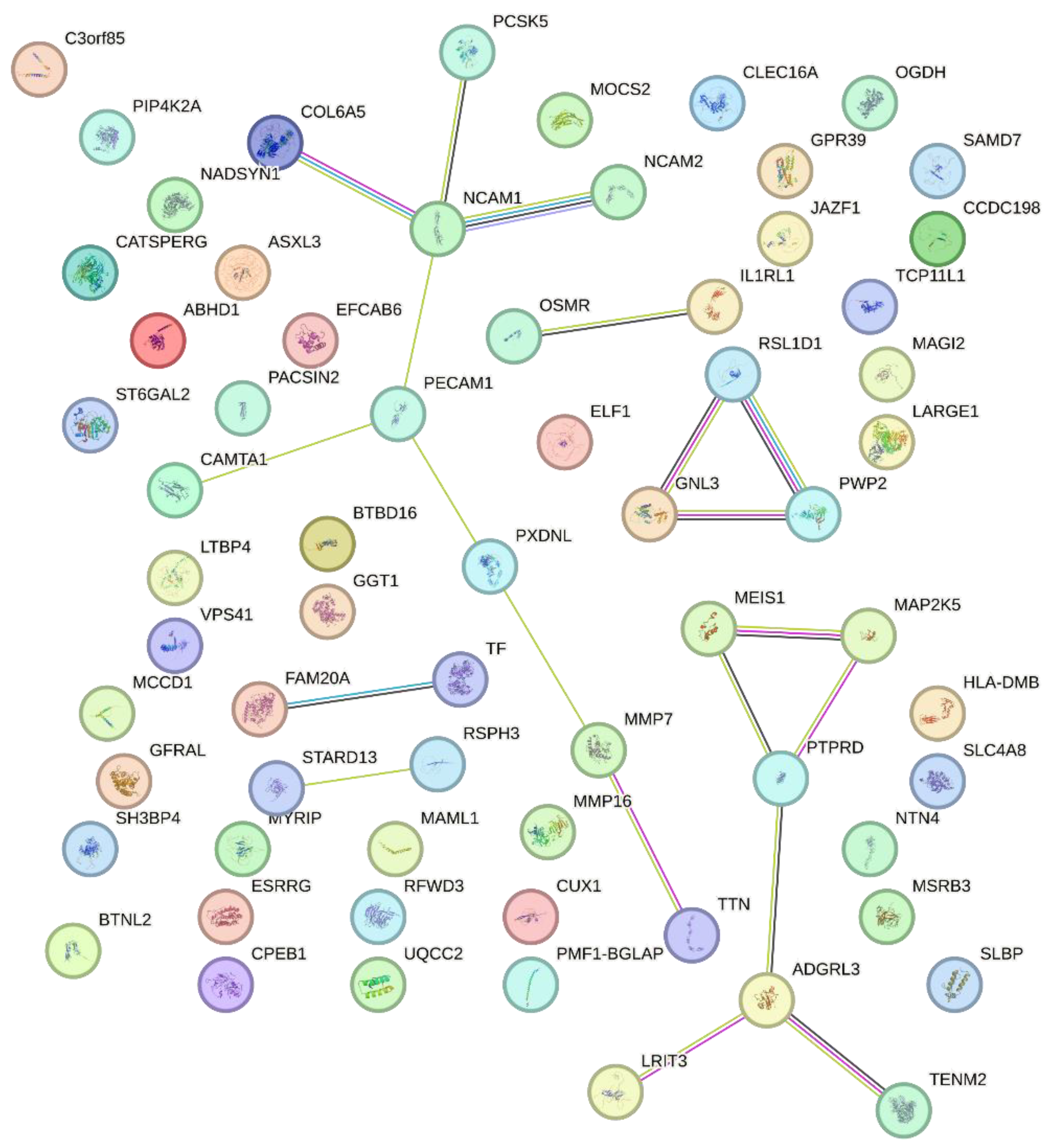

2. Results

3. Discussion

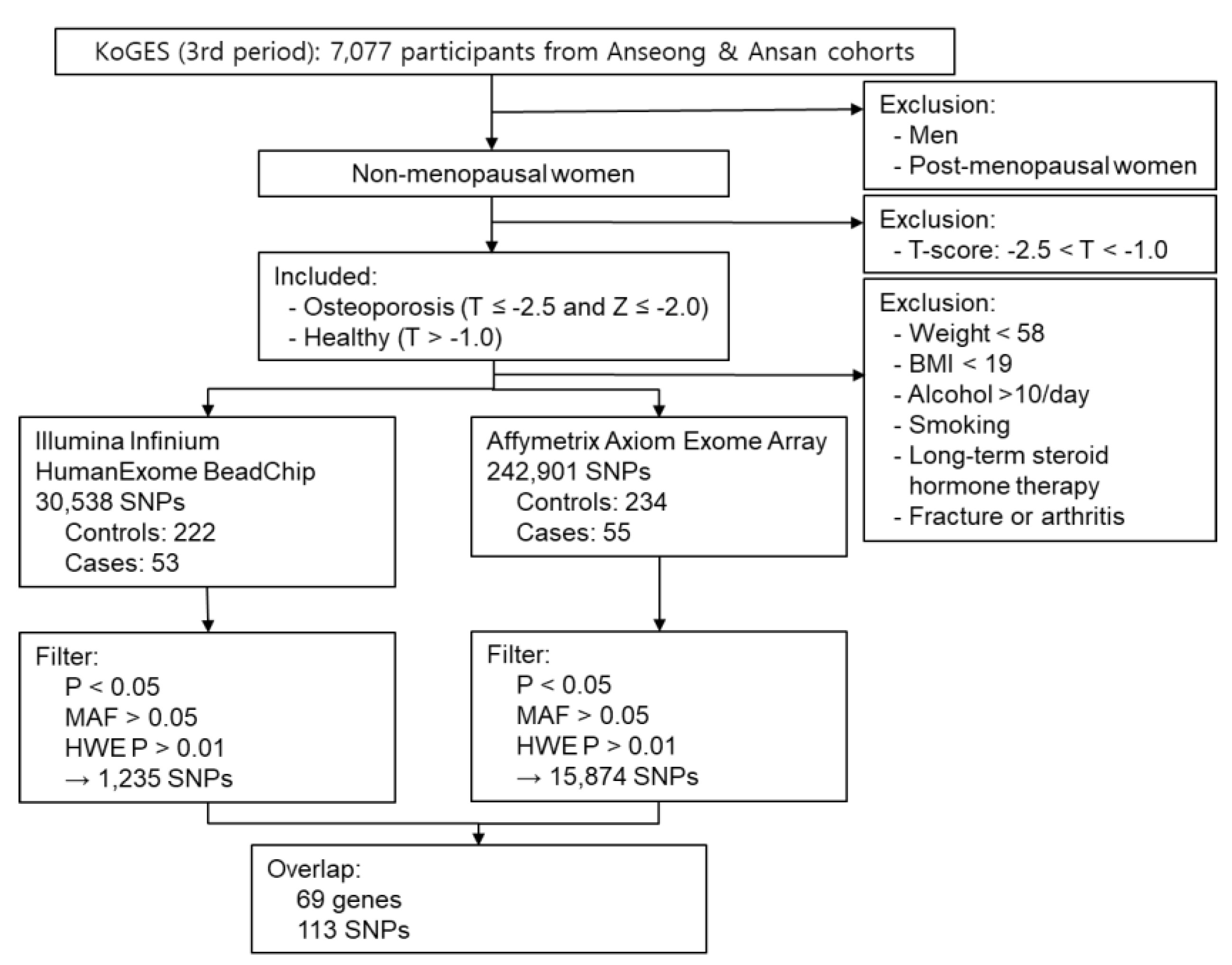

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Study Subjects

4.2. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Adachi, J. D.; Ioannidis, G.; Pickard, L.; Berger, C.; Prior, J. C.; Joseph, L.; Hanley, D. A.; Olszynski, W. P.; Murray, T. M.; Anastassiades, T.; Hopman, W.; Brown, J. P.; Kirkland, S.; Joyce, C.; Papaioannou, A.; Poliquin, S.; Tenenhouse, A.; Papadimitropoulos, E. A. , The association between osteoporotic fractures and health-related quality of life as measured by the Health Utilities Index in the Canadian Multicentre Osteoporosis Study (CaMos). Osteoporos Int 2003, 14, 895–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, R. , Osteoporosis: cause and management. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1987, 294, 329–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGuigan, F. E.; Murray, L.; Gallagher, A.; Davey-Smith, G.; Neville, C. E.; Van't Hof, R.; Boreham, C.; Ralston, S. H. , Genetic and environmental determinants of peak bone mass in young men and women. J Bone Miner Res 2002, 17, 1273–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K. Y.; Wang, C. H.; Lin, T. Y.; Chang, C. Y.; Liu, C. L.; Hsiao, Y. C.; Hung, C. C.; Wang, N. C. , Monitoring early developed low bone mineral density in HIV-infected patients by intact parathyroid hormone and circulating fibroblast growth factor 23. J Microbiol Immunol Infect 2019, 52, 693–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, K. , [Graves' disease and bone metabolism]. Nihon Rinsho 2006, 64, 2317–2322. [Google Scholar]

- Seo, S.; Chun, S.; Newell, M. A.; Yun, M. , Association between alcohol consumption and Korean young women's bone health: a cross sectional study from the 2008 to 2011 Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. BMJ Open 2015, 5, e007914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Briot, K. , Bone and glucocorticoids. Ann Endocrinol (Paris) 2018, 79, 115–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jouanny, P.; Guillemin, F.; Kuntz, C.; Jeandel, C.; Pourel, J. , Environmental and genetic factors affecting bone mass. Similarity of bone density among members of healthy families. Arthritis Rheum 1995, 38, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, F.; Zhou, D.; Shen, G.; Cui, Y.; Lv, Q.; Wei, F. , Association of VDR and OPG gene polymorphism with osteoporosis risk in Chinese postmenopausal women. Climacteric 2019, 22, 208–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondockova, V.; Adamkovicova, M.; Lukacova, M.; Grosskopf, B.; Babosova, R.; Galbavy, D.; Martiniakova, M.; Omelka, R. , The estrogen receptor 1 gene affects bone mineral density and osteoporosis treatment efficiency in Slovak postmenopausal women. BMC Med Genet 2018, 19, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolski, H.; Drews, K.; Bogacz, A.; Kaminski, A.; Barlik, M.; Bartkowiak-Wieczorek, J.; Klejewski, A.; Ozarowski, M.; Majchrzycki, M.; Seremak-Mrozikiewicz, A. , The RANKL/RANK/OPG signal trail: significance of genetic polymorphisms in the etiology of postmenopausal osteoporosis. Ginekol Pol 2016, 87, 347–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Igo, R. P., Jr.; Cooke Bailey, J. N.; Romm, J.; Haines, J. L.; Wiggs, J. L. , Quality Control for the Illumina HumanExome BeadChip. Curr Protoc Hum Genet 2016, 90, 2–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizrahi-Man, O.; Woehrmann, M. H.; Webster, T. A.; Gollub, J.; Bivol, A.; Keeble, S. M.; Aull, K. H.; Mittal, A.; Roter, A. H.; Wong, B. A.; Schmidt, J. P. , Novel genotyping algorithms for rare variants significantly improve the accuracy of Applied Biosystems Axiom array genotyping calls: Retrospective evaluation of UK Biobank array data. PLoS One 2022, 17, e0277680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, C. S.; Choi, H. J.; Kim, M. J.; Kim, J. T.; Yu, S. H.; Koo, B. K.; Cho, H. Y.; Cho, S. W.; Kim, S. W.; Park, Y. J.; Jang, H. C.; Kim, S. Y.; Cho, N. H. , Prevalence and risk factors of osteoporosis in Korea: a community-based cohort study with lumbar spine and hip bone mineral density. Bone 2010, 47, 378–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatsumi, Y.; Higashiyama, A.; Kubota, Y.; Sugiyama, D.; Nishida, Y.; Hirata, T.; Kadota, A.; Nishimura, K.; Imano, H.; Miyamatsu, N.; Miyamoto, Y.; Okamura, T. , Underweight Young Women Without Later Weight Gain Are at High Risk for Osteopenia After Midlife: The KOBE Study. J Epidemiol 2016, 26, 572–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cenci, S.; Weitzmann, M. N.; Roggia, C.; Namba, N.; Novack, D.; Woodring, J.; Pacifici, R. , Estrogen deficiency induces bone loss by enhancing T-cell production of TNF-alpha. J Clin Invest 2000, 106, 1229–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khosla, S.; Atkinson, E. J.; Melton, L. J., 3rd; Riggs, B. L. , Effects of age and estrogen status on serum parathyroid hormone levels and biochemical markers of bone turnover in women: a population-based study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1997, 82, 1522–1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebeling, P. R.; Sandgren, M. E.; DiMagno, E. P.; Lane, A. W.; DeLuca, H. F.; Riggs, B. L. , Evidence of an age-related decrease in intestinal responsiveness to vitamin D: relationship between serum 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 and intestinal vitamin D receptor concentrations in normal women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1992, 75, 176–182. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lips, P.; Wiersinga, A.; van Ginkel, F. C.; Jongen, M. J.; Netelenbos, J. C.; Hackeng, W. H.; Delmas, P. D.; van der Vijgh, W. J. , The effect of vitamin D supplementation on vitamin D status and parathyroid function in elderly subjects. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1988, 67, 644–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holick, M. F. , Perspective on the impact of weightlessness on calcium and bone metabolism. Bone 1998, (5 Suppl), 105S–111S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, D. E.; Dai, A.; Tiffee, J. C.; Li, H. H.; Mundy, G. R.; Boyce, B. F. , Estrogen promotes apoptosis of murine osteoclasts mediated by TGF-beta. Nat Med 1996, 2, 1132–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D'Amelio, P.; Grimaldi, A.; Di Bella, S.; Brianza, S. Z. M.; Cristofaro, M. A.; Tamone, C.; Giribaldi, G.; Ulliers, D.; Pescarmona, G. P.; Isaia, G. , Estrogen deficiency increases osteoclastogenesis up-regulating T cells activity: a key mechanism in osteoporosis. Bone 2008, 43, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brennan, M. A.; Haugh, M. G.; O'Brien, F. J.; McNamara, L. M. , Estrogen withdrawal from osteoblasts and osteocytes causes increased mineralization and apoptosis. Horm Metab Res 2014, 46, 537–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elfassihi, L.; Giroux, S.; Bureau, A.; Laflamme, N.; Cole, D. E.; Rousseau, F. , Association with replication between estrogen-related receptor gamma (ESRRgamma) polymorphisms and bone phenotypes in women of European ancestry. Journal of bone and mineral research : the official journal of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research 2010, 25, 901–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardelli, M.; Aubin, J. E. , ERRgamma is not required for skeletal development but is a RUNX2-dependent negative regulator of postnatal bone formation in male mice. PLoS One 2014, 9, e109592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Enoki, Y.; Sato, T.; Kokabu, S.; Hayashi, N.; Iwata, T.; Yamato, M.; Usui, M.; Matsumoto, M.; Tomoda, T.; Ariyoshi, W.; Nishihara, T.; Yoda, T. , Netrin-4 Promotes Differentiation and Migration of Osteoblasts. In vivo 2017, 31, 793–799. [Google Scholar]

- Enoki, Y.; Sato, T.; Tanaka, S.; Iwata, T.; Usui, M.; Takeda, S.; Kokabu, S.; Matsumoto, M.; Okubo, M.; Nakashima, K.; Yamato, M.; Okano, T.; Fukuda, T.; Chida, D.; Imai, Y.; Yasuda, H.; Nishihara, T.; Akita, M.; Oda, H.; Okazaki, Y.; Suda, T.; Yoda, T. , Netrin-4 derived from murine vascular endothelial cells inhibits osteoclast differentiation in vitro and prevents bone loss in vivo. FEBS letters 2014, 588, 2262–2269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D'Amelio, P.; Cristofaro, M. A.; Tamone, C.; Morra, E.; Di Bella, S.; Isaia, G.; Grimaldi, A.; Gennero, L.; Gariboldi, A.; Ponzetto, A.; Pescarmona, G. P.; Isaia, G. C. , Role of iron metabolism and oxidative damage in postmenopausal bone loss. Bone 2008, 43, 1010–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, J. M.; Kim, T. H.; Kim, H. J.; Park, E. K.; Yang, E. K.; Kim, S. Y. , Genetic association of angiogenesis- and hypoxia-related gene polymorphisms with osteonecrosis of the femoral head. Exp Mol Med 2010, 42, 376–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swanberg, M.; McGuigan, F. E.; Ivaska, K. K.; Gerdhem, P.; Akesson, K. , Polymorphisms in the inflammatory genes CIITA, CLEC16A and IFNG influence BMD, bone loss and fracture in elderly women. PLoS One 2012, 7, e47964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Tworkoski, K.; Michaud, M.; Madri, J. A. , Bone marrow monocyte PECAM-1 deficiency elicits increased osteoclastogenesis resulting in trabecular bone loss. Journal of immunology 2009, 182, 2672–2679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, J.; Hall, B. K. , N-CAM is not required for initiation of secondary chondrogenesis: the role of N-CAM in skeletal condensation and differentiation. The International journal of developmental biology 1999, 43, 335–342. [Google Scholar]

- Hiramatsu, K.; Asaba, Y.; Takeshita, S.; Nimura, Y.; Tatsumi, S.; Katagiri, N.; Niida, S.; Nakajima, T.; Tanaka, S.; Ito, M.; Karsenty, G.; Ikeda, K. , Overexpression of gamma-glutamyltransferase in transgenic mice accelerates bone resorption and causes osteoporosis. Endocrinology 2007, 148, 2708–2715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moriwaki, S.; Into, T.; Suzuki, K.; Miyauchi, M.; Takata, T.; Shibayama, K.; Niida, S. , gamma-Glutamyltranspeptidase is an endogenous activator of Toll-like receptor 4-mediated osteoclastogenesis. Sci Rep 2016, 6, 35930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Pandey, A. K.; Mulligan, M. K.; Williams, E. G.; Mozhui, K.; Li, Z.; Jovaisaite, V.; Quarles, L. D.; Xiao, Z.; Huang, J.; Capra, J. A.; Chen, Z.; Taylor, W. L.; Bastarache, L.; Niu, X.; Pollard, K. S.; Ciobanu, D. C.; Reznik, A. O.; Tishkov, A. V.; Zhulin, I. B.; Peng, J.; Nelson, S. F.; Denny, J. C.; Auwerx, J.; Lu, L.; Williams, R. W. , Joint mouse-human phenome-wide association to test gene function and disease risk. Nature communications 2016, 7, 10464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Liao, X.; Chen, F.; Wang, B.; Huang, J.; Jian, G.; Huang, Z.; Yin, G.; Liu, H.; Jin, D. , Circulating microRNAs, miR-10b-5p, miR-328-3p, miR-100 and let-7, are associated with osteoblast differentiation in osteoporosis. Int J Clin Exp Pathol 2018, 11, 1383–1390. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tang, F.; Zhang, R.; He, Y.; Zou, M.; Guo, L.; Xi, T. , MicroRNA-125b induces metastasis by targeting STARD13 in MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells. PLoS One 2012, 7, e35435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foucan, L.; Velayoudom-Cephise, F. L.; Larifla, L.; Armand, C.; Deloumeaux, J.; Fagour, C.; Plumasseau, J.; Portlis, M. L.; Liu, L.; Bonnet, F.; Ducros, J. , Polymorphisms in GC and NADSYN1 Genes are associated with vitamin D status and metabolic profile in Non-diabetic adults. BMC endocrine disorders 2013, 13, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shao, B.; Jiang, S.; Muyiduli, X.; Wang, S.; Mo, M.; Li, M.; Wang, Z.; Yu, Y. , Vitamin D pathway gene polymorphisms influenced vitamin D level among pregnant women. Clin Nutr 2018, (6 Pt A), 2230–2237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmons, K. M.; Beaudin, S. G.; Narvaez, C. J.; Welsh, J. , Gene Signatures of 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 Exposure in Normal and Transformed Mammary Cells. Journal of cellular biochemistry 2015, 116, 1693–1711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, L.; Anderson, P. H.; Turner, A. G.; Pishas, K. I.; Dhatrak, D. J.; Gill, P. G.; Morris, H. A.; Callen, D. F. , Identification of vitamin D(3) target genes in human breast cancer tissue. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 2016, 164, 90–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locquet, M.; Beaudart, C.; Reginster, J. Y.; Bruyere, O. , Association Between the Decline in Muscle Health and the Decline in Bone Health in Older Individuals from the SarcoPhAge Cohort. Calcif Tissue Int 2019, 104, 273–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, S. Z.; No, M. H.; Heo, J. W.; Park, D. H.; Kang, J. H.; Kim, S. H.; Kwak, H. B. , Role of exercise in age-related sarcopenia. J Exerc Rehabil 2018, 14, 551–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popov, D. V.; Makhnovskii, P. A.; Kurochkina, N. S.; Lysenko, E. A.; Vepkhvadze, T. F.; Vinogradova, O. L. , Intensity-dependent gene expression after aerobic exercise in endurance-trained skeletal muscle. Biol Sport 2018, 35, 277–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Negro-Vilar, A. , Selective androgen receptor modulators (SARMs): a novel approach to androgen therapy for the new millennium. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1999, 84, 3459–3462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niki, T.; Takahashi-Niki, K.; Taira, T.; Iguchi-Ariga, S. M.; Ariga, H. , DJBP: a novel DJ-1-binding protein, negatively regulates the androgen receptor by recruiting histone deacetylase complex, and DJ-1 antagonizes this inhibition by abrogation of this complex. Mol Cancer Res 2003, 1, 247–261. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Fishilevich, S.; Zimmerman, S.; Kohn, A.; Iny Stein, T.; Olender, T.; Kolker, E.; Safran, M.; Lancet, D. , Genic insights from integrated human proteomics in GeneCards. Database (Oxford) 2016, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, Z.; Sun, B.; Wang, Z. P.; He, J. W.; Fu, W. Z.; Fan, Y. B.; Zhang, Z. L. , Whole-Exome Sequencing Identifies Novel Recurrent Somatic Mutations in Sporadic Parathyroid Adenomas. Endocrinology 2018, 159, 3061–3068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quartier, A.; Chatrousse, L.; Redin, C.; Keime, C.; Haumesser, N.; Maglott-Roth, A.; Brino, L.; Le Gras, S.; Benchoua, A.; Mandel, J. L.; Piton, A. , Genes and Pathways Regulated by Androgens in Human Neural Cells, Potential Candidates for the Male Excess in Autism Spectrum Disorder. Biol Psychiatry 2018, 84, 239–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giguere, V. , To ERR in the estrogen pathway. Trends in endocrinology and metabolism: TEM 2002, 13, 220–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esseghir, S.; Kennedy, A.; Seedhar, P.; Nerurkar, A.; Poulsom, R.; Reis-Filho, J. S.; Isacke, C. M. , Identification of NTN4, TRA1, and STC2 as prognostic markers in breast cancer in a screen for signal sequence encoding proteins. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research 2007, 13, 3164–3173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hansen, C. N.; Ketabi, Z.; Rosenstierne, M. W.; Palle, C.; Boesen, H. C.; Norrild, B. , Expression of CPEB, GAPDH and U6snRNA in cervical and ovarian tissue during cancer development. APMIS 2009, 117, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa Martins, J. P.; Liu, X.; Oke, A.; Arora, R.; Franciosi, F.; Viville, S.; Laird, D. J.; Fung, J. C.; Conti, M. , DAZL and CPEB1 regulate mRNA translation synergistically during oocyte maturation. J Cell Sci 2016, 129, 1271–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyon, C.; Mansour-Hendili, L.; Chantot-Bastaraud, S.; Donadille, B.; Kerlan, V.; Dode, C.; Jonard, S.; Delemer, B.; Gompel, A.; Reznik, Y.; Touraine, P.; Siffroi, J. P.; Christin-Maitre, S. , Deletion of CPEB1 Gene: A Rare but Recurrent Cause of Premature Ovarian Insufficiency. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2016, 101, 2099–2104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Lai, Z.; Shi, L.; Tian, Y.; Luo, A.; Xu, Z.; Ma, X.; Wang, S. , Repeated superovulation increases the risk of osteoporosis and cardiovascular diseases by accelerating ovarian aging in mice. Aging (Albany NY) 2018, 10, 1089–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R. S.; Liao, X.; Chen, F. R.; Wang, B. W.; Huang, J. M.; Jian, G. J.; Huang, Z. Y.; Yin, G. H.; Liu, H. Y.; Jin, D. D. , Circulating microRNAs, miR-10b-5p, miR-328-3p, miR-100 and let-7, are associated with osteoblast differentiation in osteoporosis. Int J Clin Exp Patho 2018, 11, 1383. [Google Scholar]

- Sheng, L.; Anderson, P. H.; Turner, A. G.; Pishas, K. I.; Dhatrak, D. J.; Gill, P. G.; Morris, H. A.; Callen, D. F. , Identification of vitamin D3 target genes in human breast cancer tissue. The Journal of steroid biochemistry and molecular biology 2016, 164, 90–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vondracek, S. F.; Hansen, L. B.; McDermott, M. T. , Osteoporosis risk in premenopausal women. Pharmacotherapy 2009, 29, 305–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, C. C.; Chow, C. C.; Tellier, L. C.; Vattikuti, S.; Purcell, S. M.; Lee, J. J. , Second-generation PLINK: rising to the challenge of larger and richer datasets. Gigascience 2015, 4, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Dvorkin, D.; Da, Y. , SNPEVG: a graphical tool for GWAS graphing with mouse clicks. BMC Bioinformatics 2012, 13, 319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adzhubei, I. A.; Schmidt, S.; Peshkin, L.; Ramensky, V. E.; Gerasimova, A.; Bork, P.; Kondrashov, A. S.; Sunyaev, S. R. , A method and server for predicting damaging missense mutations. Nat Methods 2010, 7, 248–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaser, R.; Adusumalli, S.; Leng, S. N.; Sikic, M.; Ng, P. C. , SIFT missense predictions for genomes. Nat Protoc 2016, 11, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, Y.; Chan, A. P. , PROVEAN web server: a tool to predict the functional effect of amino acid substitutions and indels. Bioinformatics 2015, 31, 2745–2747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Control | Osteoporosis | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 47.08 ± 2.57 | 47.54 ± 2.46 | 0.218 |

| Weight (kg) | 63.94 ± 5.13 | 66.62 ± 7.98 | 0.018 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 25.71 ± 2.35 | 27.23 ± 3.22 | 0.001 |

| Alcohol consumption | 1.06 ± 2.03 | 0.66 ± 1.35 | 0.072 |

| Calcium consumption | 435.88 ± 196.07 | 485.01 ± 205.45 | 0.092 |

| Medical history of fracture | none | none | |

| Medical history of arthritis | none | none | |

| Smoking | none | none | |

| Long term steroid | none | none | |

| Hormone therapy | none | none | |

| DR-SOS | 4269.38 ± 123.94 | 4107.46 ± 152.21 | 0.000* |

| DR-T | 0.8 ± 0.99 | -0.45 ± 1.19 | 0.000* |

| DR-Z | 0.92 ± 1.02 | -0.29 ± 1.22 | 0.000* |

| MT-SOS | 3959.12 ± 65.93 | 3608.74 ± 90.86 | 0.000* |

| MT-T | 0.001 ± 0.63 | -3.4 ± 0.89 | 0.000* |

| MT-Z | 0.2 ± 0.63 | -3.2 ± 0.92 | 0.000* |

| SNP | Chromosome | Position | Reference Allele | Alternate Allele | Gene | PolyPhen-2 | SIFT | PROVEAN | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| score | prediction | score | prediction | score | prediction | ||||||

| rs1799852 | 3 | 133475722 | C | T | TF | - | - | 0.333 | tolerated | 0.00 | neutral |

| rs11917356 | 3 | 130110550 | A | G | COL6A5 | 0.093 | benign | 0.717 | tolerated | -1.79 | neutral |

| rs2276360 | 11 | 71169547 | G | C | NADSYN1 | 0.000 | benign | 1.000 | tolerated | 2.56 | neutral |

| rs1128431 | 15 | 82456227 | T | C | EFTUD1 | 0.791 | possibly damaging | 0.010 | deleterious | -1.00 | neutral |

| rs7232237 | 18 | 31324934 | A | G | ASXL3 | 0.000 | benign | 0.668 | tolerated | -0.84 | neutral |

| rs2282632 | 18 | 31320229 | A | G | ASXL3 | 0.003 | benign | 0.744 | tolerated | -0.73 | neutral |

| SNP | Gene | Chromosome | Position |

P value (exome) |

P value (Affymetrix) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs783540 | CPEB1 | 15 | 83254708 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| rs3731646 | SH3BP4 | 2 | 235950002 | 0.000 | 0.003 |

| rs10506525 | MSRB3 | 12 | 65783378 | 0.001 | 0.003 |

| rs2110871 | MAGI2 | 7 | 78080548 | 0.002 | 0.002 |

| rs2172802 | LPHN3 | 4 | 62453209 | 0.003 | 0.001 |

| rs6895902 | MAML1 | 5 | 179201847 | 0.004 | 0.001 |

| rs2020945 | PWP2 | 21 | 45528919 | 0.004 | 0.003 |

| rs3756987 | RSPH3 | 6 | 159398700 | 0.004 | 0.010 |

| rs2286550 | CATSPERG | 19 | 38861362 | 0.004 | 0.008 |

| rs4729759 | CUX1 | 7 | 101536886 | 0.005 | 0.004 |

| rs10513680 | SAMD7 | 3 | 169644710 | 0.005 | 0.000 |

| rs1052053 | PMF1-BFLAP | 1 | 156202173 | 0.005 | 0.008 |

| rs2764020 | STARD13 | 13 | 34234642 | 0.006 | 0.003 |

| rs7088318 | PIP4K2A | 10 | 22852948 | 0.007 | 0.001 |

| rs151719 | HLA-DMB | 6 | 32903900 | 0.007 | 0.005 |

| rs2302234 | FAM20A | 17 | 66538239 | 0.007 | 0.008 |

| rs16990991 | EFCAB6 | 22 | 44167684 | 0.008 | 0.003 |

| rs12757165 | ESRRG | 1 | 216716537 | 0.009 | 0.003 |

| SNP | Chromo-some | Position | Gene | Functional Consequence |

P value (exome) |

P value (Affy-metrix) |

Possible mechanism in the development of osteoporosis |

Function | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs12757165 | 1 | 216716537 | ESRRG | intron | 0.009 | 0.003 | Bone mineral density, | Determination of bone density | [24] |

| rs1799852 | 3 | 133475722 | TF | synonymous | 0.029 | 0.005 | Osteoclastogenesis | Bone mineral density | [28] |

| rs1436109 | 11 | 112991618 | NCAM1 | intron | 0.012 | 0.001 | Osteogenesis | Osteogenesis | [32] |

| rs4341610 | 12 | 96149288 | NTN4 | intron | 0.029 | 0.027 | To promote osteoblasts and inhibit osteoclast | [26,27] | |

| rs6498142 | 16 | 11081249 | CLECL16A | intron | 0.046 | 0.030 | Bone mineral density | [30] | |

| rs11917356 | 3 | 130110550 | COL6A5 | missense | 0.014 | 0.005 | Variation in bone mineral density | [35] | |

| rs2812 | 17 | 62401118 | PECAM1 | UTR 3' | 0.016 | 0.027 | Negative regulator of Osteoclastogenesis | [31] | |

| rs4820599 | 22 | 24990213 | GGT1 | intron | 0.003 | 0.041 | Osteoclastogenesis | [33] | |

| rs2764020 | 13 | 34234642 | STARD13 | intron | 0.006 | 0.003 | Target of miR-125, which is up-regulated in Osteoporosis | [56] | |

| rs2276360 | 11 | 71169547 | NADSYN1 | missense | 0.038 | 0.027 | Vitamin D | Vitamin D status and metabolic profile | [38,39] |

| rs1128431 | 15 | 82456227 | EFTUD1 | missense | 0.025 | 0.032 | Target gene for vitamin D | [40,57] | |

| rs12757165 | 1 | 216716537 | ESRRG | intron | 0.009 | 0.003 | Skeletal muscle | Skeletal muscle exercise | [44] |

| rs11090122 | 22 | 43308475 | PACSIN2 | intron | 0.045 | 0.028 | Skeletal muscle exercise | [44] | |

| rs12757165 | 1 | 216716537 | ESRRG | intron | 0.009 | 0.003 | Reproductive system | Estrogen pathways | [24,50] |

| rs16990991 | 22 | 44167684 | EFCAB6 | intron | 0.008 | 0.003 | Regulation of androgen receptor | [46] | |

| rs4341610 | 12 | 96149288 | NTN4 | intron | 0.029 | 0.027 | Prognosis of ER-positive breast cancer | [51] | |

| rs783540 | 15 | 83254708 | CPEB1 | intron | 0.000 | 0.000 | Oocyte maturation | [53,54] | |

| rs7232237 | 18 | 31324934 | ASXL3 | missense | 0.015 | 0.011 | Androgen pathway | [49] | |

| rs2282632 | 18 | 31320229 | ASXL3 | missense | 0.019 | 0.038 | Androgen pathway | [49] | |

| rs1128431 | 15 | 82456227 | EFTUD1 | missense | 0.025 | 0.032 | Breast cancer | [57] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).