1. Introduction

Left ventricular non-compaction cardiomyopathy (LVNC) is characterized by a spongy ventricular architecture with thick trabeculae and deep blood-filled recesses [

1]. It was initially attributed to embryonic compaction failure between gestational weeks five and eight; however, contemporary genetic evidence places LVNC within a spectrum shared with dilated and hypertrophic cardiomyopathies [

2,

3,

13]. The European Society of Cardiology lists LVNC among “unclassified” cardiomyopathies, whereas the American Heart Association includes it among primary congenital forms [

11]. Apparent prevalence varies with imaging technique and population: Ross et al. reported 1.05% in healthy controls, 3.16% in athletes, and up to 18.6% in pregnant women using echocardiography [

12]. Cardiac magnetic resonance increases detection to 14.8%, and the disparity between criteria—Petersen identifying 39% versus Captur 3%—illustrates a considerable risk of over-diagnosis [

3,

15]. Described phenotypes include isolated non-compaction with preserved function; dilated and hypertrophic variants that overlap with DCM and HCM [

13,

21]; forms associated with congenital heart disease (e.g., tetralogy of Fallot) [

16]; and acquired, reversible hypertrabeculation observed in pregnancy, athletes, and sickle-cell anemia [

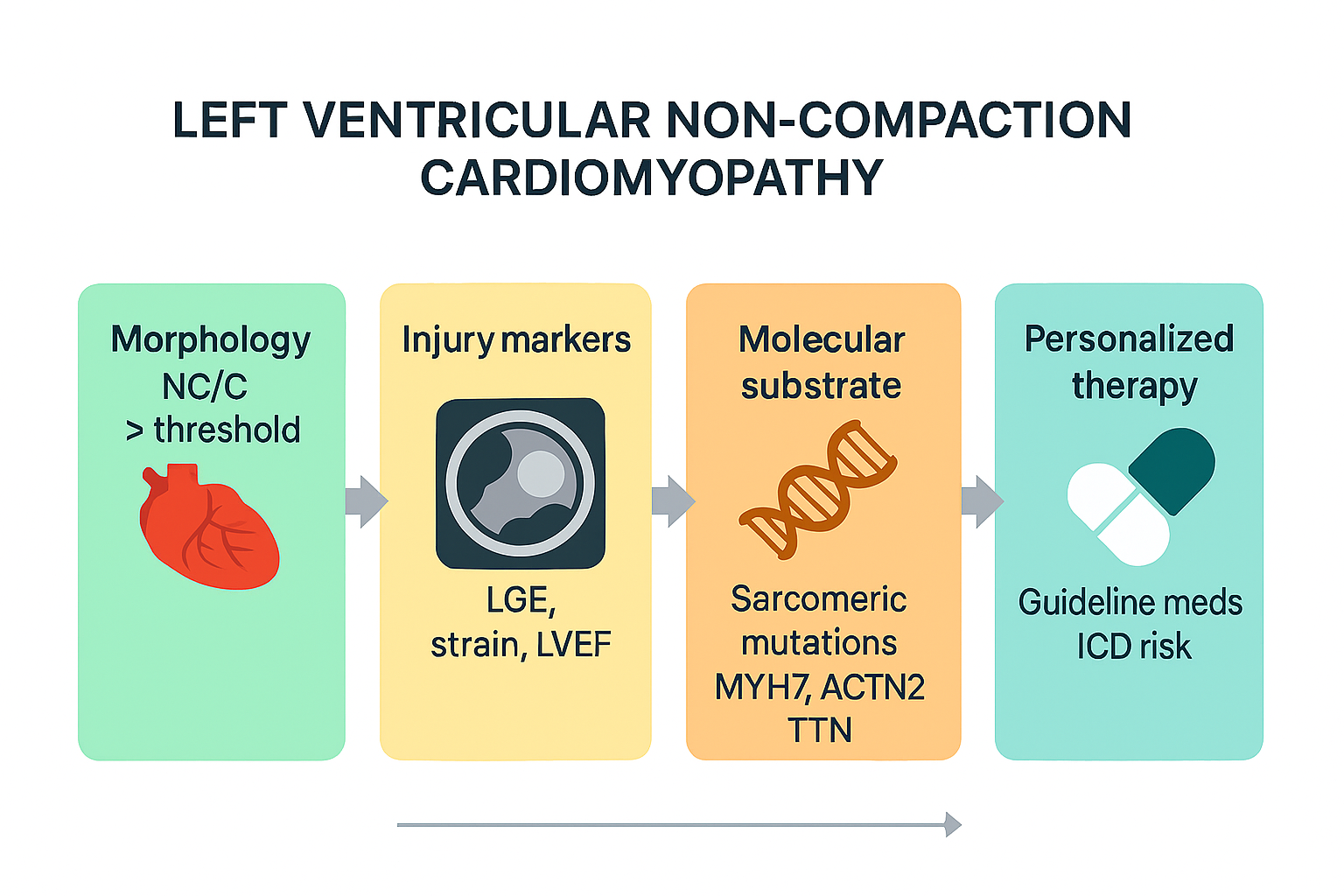

29]. In the current era, cardiomyopathies are increasingly approached through a precision-medicine lens that tailors diagnostics and therapy to the individual’s molecular and phenotypic profile. LVNC—with marked genotype–phenotype variability and reversible forms (e.g., pregnancy, athletic remodeling)—offers a unique opportunity to apply and test such approaches [36].

Objective of the review: To comprehensively describe the pathophysiology, epidemiology, clinical presentation, diagnostic methods, differential diagnosis, treatment, and research perspectives of LVNC using evidence available up to April 2025.

Table 1.

“Apparent prevalence” denotes the proportion of individuals in cohort studies who meet at least one echocardiographic or CMR morphological threshold for LVNC and therefore does not equal disease prevalence. The table was created de novo by the authors from published data; no third-party figures were reproduced. Row-level sources: healthy controls [

12]; athletes [

6]; pregnancy [

5]. Estimates vary with criteria and modality (e.g., echocardiography using Chin or Jenni definitions; CMR using the Petersen diastolic NC/C ≥ 2.3 ratio or Jacquier trabeculated mass > 20%), loading conditions, and segmentation variability; figures should be interpreted as directional signals rather than true population prevalence. In low pretest-probability settings (healthy adults, athletes, pregnancy), morphology alone has limited positive predictive value; a diagnostic label should be considered only when morphology is accompanied by at least one injury marker such as late gadolinium enhancement (LGE), reduced systolic function, malignant arrhythmias, or thromboembolism. Pregnancy- and training-related hypertrabeculation frequently regresses; repeat imaging at 6–12 months postpartum or after a period of de-training is recommended before assigning a permanent diagnosis. The columns summarize, respectively, the screening yield when formal cut-offs are applied, the functional profile typically observed, and the pragmatic clinical action.

Table 1.

“Apparent prevalence” denotes the proportion of individuals in cohort studies who meet at least one echocardiographic or CMR morphological threshold for LVNC and therefore does not equal disease prevalence. The table was created de novo by the authors from published data; no third-party figures were reproduced. Row-level sources: healthy controls [

12]; athletes [

6]; pregnancy [

5]. Estimates vary with criteria and modality (e.g., echocardiography using Chin or Jenni definitions; CMR using the Petersen diastolic NC/C ≥ 2.3 ratio or Jacquier trabeculated mass > 20%), loading conditions, and segmentation variability; figures should be interpreted as directional signals rather than true population prevalence. In low pretest-probability settings (healthy adults, athletes, pregnancy), morphology alone has limited positive predictive value; a diagnostic label should be considered only when morphology is accompanied by at least one injury marker such as late gadolinium enhancement (LGE), reduced systolic function, malignant arrhythmias, or thromboembolism. Pregnancy- and training-related hypertrabeculation frequently regresses; repeat imaging at 6–12 months postpartum or after a period of de-training is recommended before assigning a permanent diagnosis. The columns summarize, respectively, the screening yield when formal cut-offs are applied, the functional profile typically observed, and the pragmatic clinical action.

| Cohort |

Apparent prevalence meeting ≥1 echocardiographic criterion |

Clinical note |

| Healthy controls |

~1.05% |

Asymptomatic; low pretest probability |

| Competitive athletes |

~3.16% |

Preserved LVEF in the vast majority; reassess after de-training if doubt persists |

| Pregnancy (third trimester) |

up to ~18.6% |

Predominantly preserved LVEF; regression reported at 1 year postpartum in a subset |

2. Materials and Methods

We conducted a narrative review addressing the pathophysiology, epidemiology, genetics, clinical presentation, diagnosis, prognosis, and management of left ventricular non-compaction cardiomyopathy (LVNC). Searches were performed in PubMed, Google Scholar, and CrossRef from January 2000 to July 2024. No language restrictions were applied provided that an English abstract was available. We additionally screened the reference lists of included publications to identify relevant studies not captured by the electronic searches.

Eligibility criteria. We considered for inclusion: (i) human clinical studies enrolling ≥10 individuals with LVNC; (ii) genetic studies (family series, multigene panels, exome/genome) with phenotypic characterization of LVNC; (iii) imaging studies with diagnostic or prognostic implications; (iv) mechanistic, animal, or cellular models directly relevant to trabeculation/compaction pathways; and (v) narrative or systematic reviews, meta-analyses, position statements, or consensus documents. We excluded isolated case reports without mechanistic contribution, editorials or letters without original data, and series with ambiguous or mixed cardiomyopathic phenotypes when LVNC could not be distinguished.

Study selection and data extraction. Two reviewers independently screened titles/abstracts and assessed full texts for eligibility. From each eligible article we extracted study design, population, LVNC definition, imaging/genetic methods, and clinically relevant outcomes (heart failure events, arrhythmias, thromboembolism, transplantation, or mortality). When available, identifiers (DOI/PMID) were verified for accuracy. Disagreements were resolved by discussion and consensus.

Synthesis approach. Given the heterogeneity of definitions, imaging thresholds, and study designs, we synthesized the evidence qualitatively and structured it by domain (etiology/pathophysiology, clinical presentation, diagnosis, prognosis/risk stratification, treatment, and differential diagnosis). Quantitative pooling was not attempted because between-study variability in LVNC criteria and outcome definitions precluded a meaningful meta-analysis.

Administrative note. This is a narrative review that does not involve human participants or individual patient data beyond published reports; ethical approval and consent were therefore not required.

3. Etiology and Pathophysiology

LVNC arises from the interplay between genetic variants, developmental programs of trabeculation/compaction, and hemodynamic and mechanobiologic cues. Sarcomeric genes are most frequently implicated, particularly MYH7 and ACTN2, with TTN truncating variants contributing in a substantial subset; overlap with dilated and hypertrophic cardiomyopathies is common, supporting a continuum rather than a discrete entity in many families [

4,

7,

8]. Additional contributors include nuclear-envelope genes (e.g., LMNA), ion-channel and conduction genes (e.g., HCN4, SCN5A), developmental transcription factors (NKX2-5, PRDM16, TBX20), and mitochondrial pathways, each modulating penetrance, age at presentation, and associated extracardiac features [

4,

7,

8].

Developmentally, trabeculation precedes compaction; signaling axes such as NOTCH/BMP10 and neuregulin–ErbB orchestrate endocardial–myocardial crosstalk, while altered mechanotransduction and flow patterns can skew trabecular architecture [

4,

7]. In adults, loading conditions and mechanosensitive pathways (e.g., MAPK–AKT, Hippo/YAP–TAZ, and TGF-β remodeling) influence phenotype expression, fibrotic remodeling, and energetics, helping explain reversible hypertrabeculation in pregnancy or with intensive athletic training, as well as progression to ventricular dysfunction in genetically primed myocardium [

4,

7,

8].

Imaging correlates of injury are integral to pathobiology. Late gadolinium enhancement (LGE) reflects extracellular matrix expansion and correlates with adverse outcomes across cohorts [

9]. T1/T2 mapping and deformation indices (e.g., global longitudinal strain) capture diffuse disease and subclinical dysfunction that may precede overt changes in ejection fraction, refining risk classification when morphology alone is equivocal [

14]. Genotype-specific clinical signals are increasingly recognized: LMNA variants track with early conduction disease and atrial/ventricular arrhythmias; HCN4 with sinus-node dysfunction and occasional aortic dilation; SCN5A with conduction disease and ventricular arrhythmias; and selected developmental genes with congenital phenotypes and pediatric-onset LVNC [

4,

7,

8]. Familial aggregation and variable expressivity justify genetic counseling and cascade testing, with longitudinal follow-up tailored to genotype, injury markers, and clinical course.

Table 2.

This table synthesizes the principal genetic categories implicated in LVNC and links them to biology, phenotype, and management.

Sarcomeric variants (e.g., MYH7, ACTN2, truncating TTN) support a continuum with DCM/HCM and show variable LVEF and fibrosis across cohorts [

4,

7,

8].

Nuclear-envelope variants, especially LMNA, associate with early conduction disease, atrial/ventricular arrhythmias, and higher arrhythmic risk that may lower thresholds for device therapy [

4,

7].

Ion-channel/conduction genes (e.g., HCN4, SCN5A) often present with sinus-node dysfunction, PR/QRS prolongation, ventricular arrhythmias, and occasional aortic dilation with HCN4 [

4,

7,

8].

Developmental transcription factors (NKX2-5, PRDM16, TBX20) track with congenital phenotypes and pediatric-onset LVNC [

7,

8].

Mitochondrial/metabolic defects typically underlie systemic pediatric cardiomyopathies [

7]. Injury markers such as

LGE and impaired deformation (e.g., reduced GLS) correlate with adverse outcomes and refine risk beyond morphology, complementing genotype-informed risk stratification [

9,

10,

14]. Table created

de novo by the authors from published data; no third-party figures were reproduced.

Table 2.

This table synthesizes the principal genetic categories implicated in LVNC and links them to biology, phenotype, and management.

Sarcomeric variants (e.g., MYH7, ACTN2, truncating TTN) support a continuum with DCM/HCM and show variable LVEF and fibrosis across cohorts [

4,

7,

8].

Nuclear-envelope variants, especially LMNA, associate with early conduction disease, atrial/ventricular arrhythmias, and higher arrhythmic risk that may lower thresholds for device therapy [

4,

7].

Ion-channel/conduction genes (e.g., HCN4, SCN5A) often present with sinus-node dysfunction, PR/QRS prolongation, ventricular arrhythmias, and occasional aortic dilation with HCN4 [

4,

7,

8].

Developmental transcription factors (NKX2-5, PRDM16, TBX20) track with congenital phenotypes and pediatric-onset LVNC [

7,

8].

Mitochondrial/metabolic defects typically underlie systemic pediatric cardiomyopathies [

7]. Injury markers such as

LGE and impaired deformation (e.g., reduced GLS) correlate with adverse outcomes and refine risk beyond morphology, complementing genotype-informed risk stratification [

9,

10,

14]. Table created

de novo by the authors from published data; no third-party figures were reproduced.

| Category |

Key genes (examples) |

Mechanistic theme |

Typical phenotype(s) |

Management implications |

| Sarcomeric |

MYH7, ACTN2, TTN |

Contractile/structural integrity |

LVNC overlapping with DCM/HCM; variable LVEF; fibrosis in subsets |

HF guideline-directed therapy; family screening; device decisions driven by LVEF/LGE rather than morphology alone |

| Nuclear envelope |

LMNA |

Nucleoskeletal signaling; conduction system vulnerability |

Early conduction disease; AF/VT; higher arrhythmic burden |

Lower threshold for ICD; close rhythm surveillance |

| Ion channels / conduction |

HCN4, SCN5A |

Pacemaking and depolarization |

Sinus-node dysfunction; PR/QRS prolongation; ventricular arrhythmias; occasional aortic dilation (HCN4) |

Ambulatory monitoring; EP referral as needed; aortic imaging if HCN4 |

| Developmental TFs |

NKX2-5, PRDM16, TBX20 |

Cardiac morphogenesis |

Association with congenital heart disease; pediatric presentation |

Multidisciplinary care; tailored genetic counseling |

| Mitochondrial / metabolic |

mtDNA and nuclear genes |

Bioenergetic impairment |

Pediatric cardiomyopathy with systemic features |

Metabolic work-up; exercise/rehab tailoring |

4. Clinical Presentation and Natural History

LVNC exhibits a broad clinical spectrum ranging from incidental imaging findings with preserved systolic function to overt heart failure with malignant arrhythmias. Common presentations include exertional dyspnea, fatigue, palpitations, presyncope/syncope, chest discomfort, and signs of pulmonary or systemic congestion when heart failure develops. Atrial fibrillation is frequent, and sustained ventricular tachycardia tends to cluster in patients with reduced LVEF and/or myocardial fibrosis. Thromboembolic risk increases in the presence of apical recesses, atrial fibrillation, reduced LVEF, or documented apical thrombus; anticoagulation should be individualized based on arrhythmia status, imaging evidence of thrombus, and overall risk profile.

Population-specific contexts deserve tailored interpretation. Pregnancy may unmask transient hypertrabeculation that fulfills morphological thresholds yet often regresses postpartum; reassessment 6–12 months after delivery is recommended before assigning a lifelong diagnosis. Competitive athletes frequently show increased trabeculation related to physiological remodeling with preserved LVEF and no LGE; when doubt persists, short-term de-training and multiparametric reassessment help avoid overdiagnosis. Pediatric LVNC frequently coexists with congenital heart disease or metabolic disorders, and outcomes depend on baseline function, arrhythmias, and syndromic features. Familial aggregation is common; genetic counseling and cascade screening enable early identification of at-risk relatives. Across ages, natural history is shaped by the interaction between genotype, loading conditions, and tissue injury. In asymptomatic individuals with preserved function and no injury markers, a conservative strategy with periodic clinical and imaging follow-up is appropriate; escalation is guided by development of systolic dysfunction, fibrosis on LGE, clinically significant arrhythmias, or thromboembolic events.

Table 3.

This table operationalizes common clinical presentations of LVNC into an initial work-up, pragmatic red flags, and a next action. For

incidental CMR findings with preserved LVEF, confirm views/segmentation and re-evaluate morphology with targeted echocardiography (NC/C), strain, and LGE;

presence of LGE and

reduced GLS indicate tissue injury and track with higher adverse-event rates, while a strong

family history supports inherited risk and prompts genetics and closer surveillance [

7,

9,

14]. For

palpitations or syncope, short-term ambulatory monitoring identifies NSVT or sustained VT and conduction disease; high-risk genotypes (e.g., LMNA) and arrhythmia burden justify EP evaluation and, when guideline criteria are met,

ICD consideration [

10,

17,

18,

19]. For

atrial fibrillation or prior embolism, image specifically for

apical thrombus and anticoagulate; DOACs are generally preferred, while

VKA is indicated when an apical thrombus is present or DOACs are contraindicated [

16,

23]. For

pediatric LVNC, screen for congenital or metabolic disease and tailor follow-up to baseline function and arrhythmias;

genetic counseling and cascade screening are recommended to identify at-risk relatives [

3,

7]. The table prioritizes escalation triggers anchored in injury (LGE, impaired deformation), rhythm/conduction risk, thromboembolism, and family history, aligning clinical action with individualized risk rather than morphology alone. All summary tables were created de novo; no third-party figures were reproduced.

Table 3.

This table operationalizes common clinical presentations of LVNC into an initial work-up, pragmatic red flags, and a next action. For

incidental CMR findings with preserved LVEF, confirm views/segmentation and re-evaluate morphology with targeted echocardiography (NC/C), strain, and LGE;

presence of LGE and

reduced GLS indicate tissue injury and track with higher adverse-event rates, while a strong

family history supports inherited risk and prompts genetics and closer surveillance [

7,

9,

14]. For

palpitations or syncope, short-term ambulatory monitoring identifies NSVT or sustained VT and conduction disease; high-risk genotypes (e.g., LMNA) and arrhythmia burden justify EP evaluation and, when guideline criteria are met,

ICD consideration [

10,

17,

18,

19]. For

atrial fibrillation or prior embolism, image specifically for

apical thrombus and anticoagulate; DOACs are generally preferred, while

VKA is indicated when an apical thrombus is present or DOACs are contraindicated [

16,

23]. For

pediatric LVNC, screen for congenital or metabolic disease and tailor follow-up to baseline function and arrhythmias;

genetic counseling and cascade screening are recommended to identify at-risk relatives [

3,

7]. The table prioritizes escalation triggers anchored in injury (LGE, impaired deformation), rhythm/conduction risk, thromboembolism, and family history, aligning clinical action with individualized risk rather than morphology alone. All summary tables were created de novo; no third-party figures were reproduced.

| Presentation |

Initial work-up |

Practical red flags |

Suggested action |

| Incidental CMR finding with preserved LVEF |

Confirm views/segmentation; targeted echocardiography (NC/C); strain; LGE |

LGE present; reduced GLS; strong family history of cardiomyopathy/SCD |

Short-interval follow-up; consider electrophysiology and genetics |

| Palpitations or syncope |

24–72 h Holter or patch; echocardiography/CMR |

NSVT or sustained VT; conduction disease; high-risk genotype |

EP study; ICD consideration if additional criteria are met |

| Atrial fibrillation or prior embolism |

TTE/CMR focused on apical thrombus; thromboembolic risk scores |

Apical thrombus; recurrent embolism; low LVEF |

Anticoagulation (DOAC preferred; VKA if apical thrombus or contraindications) |

| Pediatric LVNC phenotype |

Echo/CMR; genetic panel; screening for syndromic features |

Congenital defects; progressive systolic dysfunction; ventricular arrhythmias |

Multidisciplinary pediatric cardiomyopathy care; family screening |

5. Diagnosis

Diagnostic assessment of LVNC should balance morphology with evidence of myocardial injury and the clinical context. In low pretest-probability settings (healthy adults, athletes, late pregnancy), morphology alone has limited positive predictive value; combining structural thresholds with injury markers improves specificity and clinical usefulness.

Echocardiography. Three commonly used echocardiographic approaches include the

Chin ratio (X/Y ≤ 0.5 in diastole) and the

Jenni criterion (non-compacted to compacted ratio, NC/C > 2 in systole, with a bilayered myocardium and perfused intertrabecular recesses on color Doppler) [

1,

2]. Technical pitfalls include suboptimal apical windows, through-plane motion, and load dependence. When suspicion is high, targeted apical views, careful caliper placement at end-systole/end-diastole as specified by the criterion, and consideration of 3D echocardiography can reduce misclassification. Additional echocardiographic clues such as thinning of the compact layer and impaired deformation (reduced global longitudinal strain) support disease when present, but they are not diagnostic in isolation.

Cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR). CMR improves reproducibility and whole-heart coverage. The

Petersen definition uses a diastolic NC/C ≥ 2.3, while the

Jacquier approach quantifies trabeculated mass and considers values > 20% of LV mass consistent with LVNC in validation cohorts [

12,

13]. Segmentation method, reader experience, and vendor/software choices influence results and account for some variability across studies. Beyond morphology,

late gadolinium enhancement (LGE) identifies fibrosis and correlates with adverse outcomes independent of LVEF;

T1/T2 mapping and strain analysis (feature-tracking GLS) detect diffuse disease and may flag higher-risk phenotypes when ejection fraction is preserved [

9,

14].

ECG/CT/Biopsy. ECG frequently demonstrates non-specific conduction delay, bundle-branch block, or fragmented QRS; these findings variably correlate with fibrosis and arrhythmic risk. Cardiac CT can delineate trabeculation and apply NC/C thresholds in patients with MRI contraindications. Endomyocardial biopsy is reserved for suspected infiltrative/storage disease or myocarditis when results would alter management.

Diagnostic framing. A pragmatic approach is to require morphology plus at least one injury marker (fibrosis on LGE, reduced LVEF/GLS, or malignant arrhythmias/thromboembolism) before making a firm diagnosis in low pretest-probability scenarios. Familial aggregation, syndromic features, or high-risk genotypes (e.g., LMNA) increase pretest probability and may justify earlier risk stratification steps.

Table 4.

This table summarizes the most commonly used morphological criteria for LVNC and their practical pitfalls across imaging modalities. Echocardiographic thresholds (Chin end-diastolic ratio; Jenni systolic NC/C with a bilayered myocardium and perfused recesses) are simple and widely taught, but their specificity drops in low pretest-probability settings and under load-dependent conditions, and they are sensitive to apical foreshortening, caliper placement, and through-plane motion [

1,

2]. CMR improves reproducibility and whole-heart coverage; the diastolic Petersen NC/C ≥ 2.3 and the Jacquier trabeculated-mass fraction > 20% have been validated in cohorts, yet reader experience, segmentation choices, and vendor/software differences introduce variability and can shift classification rates [

12,

13]. Because morphology alone has limited positive predictive value in many real-world scenarios, decision-making should be anchored in injury markers—fibrosis on LGE, reduced LVEF/GLS, or malignant arrhythmias/thromboembolism—which consistently track with adverse outcomes and refine risk beyond structural ratios [

9,

14]. A pragmatic approach is to confirm morphology across modalities when feasible, incorporate tissue and functional injury signals, and interpret results in light of clinical context and genotype before assigning a durable diagnostic label. All summary tables were created de novo; no third-party figures were reproduced.

Table 4.

This table summarizes the most commonly used morphological criteria for LVNC and their practical pitfalls across imaging modalities. Echocardiographic thresholds (Chin end-diastolic ratio; Jenni systolic NC/C with a bilayered myocardium and perfused recesses) are simple and widely taught, but their specificity drops in low pretest-probability settings and under load-dependent conditions, and they are sensitive to apical foreshortening, caliper placement, and through-plane motion [

1,

2]. CMR improves reproducibility and whole-heart coverage; the diastolic Petersen NC/C ≥ 2.3 and the Jacquier trabeculated-mass fraction > 20% have been validated in cohorts, yet reader experience, segmentation choices, and vendor/software differences introduce variability and can shift classification rates [

12,

13]. Because morphology alone has limited positive predictive value in many real-world scenarios, decision-making should be anchored in injury markers—fibrosis on LGE, reduced LVEF/GLS, or malignant arrhythmias/thromboembolism—which consistently track with adverse outcomes and refine risk beyond structural ratios [

9,

14]. A pragmatic approach is to confirm morphology across modalities when feasible, incorporate tissue and functional injury signals, and interpret results in light of clinical context and genotype before assigning a durable diagnostic label. All summary tables were created de novo; no third-party figures were reproduced.

| Method |

Core definition |

Strengths |

Caveats / false positives |

When to use |

| Chin (echo) |

Apical ratio X/Y ≤ 0.5 in diastole |

Simple; widely taught |

Load-dependent; variable reproducibility; apical foreshortening |

Initial screening; confirm with CMR if doubt |

| Jenni (echo) |

NC/C > 2 in systole; bilayered myocardium; perfused recesses |

Adds physiological detail |

Specificity drops in athletes and pregnancy |

Moderate/high pretest settings with adequate windows |

| Petersen (CMR) |

Diastolic NC/C ≥ 2.3 |

Reproducible; whole-heart coverage |

May overcall if used alone; reader/segmentation effects |

Baseline CMR characterization |

| Jacquier (CMR) |

Trabeculated mass > 20% LV mass |

Quantifies burden |

Segmentation and software variability; thresholds cohort-dependent |

Follow-up quantification; research and complex cases |

| Risk modifiers |

LGE; reduced GLS; thin compact layer |

Improve risk classification |

Not diagnostic alone |

Combine with morphology to finalize label |

Table 5.

This table outlines contexts in which physiological hypertrabeculation is common and LVNC thresholds can be met without true disease. In endurance/strength athletes, increased trabeculation with preserved LVEF and absent LGE typically represents adaptive remodeling; short-term de-training followed by reassessment helps avoid over-diagnosis [

6]. In late pregnancy, hemodynamic loading may transiently satisfy morphological cut-offs, with postpartum regression frequently observed; repeat imaging at 6–12 months is advised before assigning a permanent label [

5]. Hyperdynamic states (e.g., anemia, thyrotoxicosis) can similarly accentuate trabeculation and should be re-evaluated after the trigger is treated. During adolescence/early adulthood, transitional remodeling may blur thresholds, so multiparametric assessment (strain, LGE) is recommended. Across these settings, morphology by itself has low positive predictive value; defer diagnosis until injury markers or persistent remodeling are demonstrated, integrating family/genetic data where relevant [

5,

6,

9,

14]. All summary tables were created de novo; no third-party figures were reproduced.

Table 5.

This table outlines contexts in which physiological hypertrabeculation is common and LVNC thresholds can be met without true disease. In endurance/strength athletes, increased trabeculation with preserved LVEF and absent LGE typically represents adaptive remodeling; short-term de-training followed by reassessment helps avoid over-diagnosis [

6]. In late pregnancy, hemodynamic loading may transiently satisfy morphological cut-offs, with postpartum regression frequently observed; repeat imaging at 6–12 months is advised before assigning a permanent label [

5]. Hyperdynamic states (e.g., anemia, thyrotoxicosis) can similarly accentuate trabeculation and should be re-evaluated after the trigger is treated. During adolescence/early adulthood, transitional remodeling may blur thresholds, so multiparametric assessment (strain, LGE) is recommended. Across these settings, morphology by itself has low positive predictive value; defer diagnosis until injury markers or persistent remodeling are demonstrated, integrating family/genetic data where relevant [

5,

6,

9,

14]. All summary tables were created de novo; no third-party figures were reproduced.

| Context |

Typical features |

Suggested follow-up |

| Endurance/strength athletes |

Increased trabeculation; preserved LVEF; absent LGE |

Reassess after a period of de-training if uncertainty remains |

| Pregnancy (third trimester) |

Increased wall stress; variable trabeculation |

Reassess 6–12 months postpartum before assigning a permanent diagnosis |

| Hyperdynamic states (e.g., anemia) |

High cardiac output; reversible remodeling |

Treat trigger; reassess morphology after stabilization |

| Adolescence/early adulthood |

Transitional remodeling |

Multiparametric assessment (strain, LGE) |

6. Prognosis and Risk Stratification

Prognosis in LVNC is driven less by morphology per se and more by markers of myocardial injury, electrical instability, and pump failure. Across cohorts, reduced LVEF, late gadolinium enhancement (LGE), and non-apical extension of trabeculation consistently associate with higher major adverse events (heart failure hospitalization, ventricular arrhythmias, stroke/systemic embolism, transplantation, or death) [

9,

10,

15]. In asymptomatic individuals with preserved function, a conservative strategy is reasonable unless injury markers emerge. When genotype is known, risk stratification should integrate variant-specific signals; for example, LMNA variants carry earlier conduction disease and arrhythmic events and may justify a lower threshold for device therapy when combined with imaging or clinical risk features [

4,

7,

10]. Tissue characterization with LGE and deformation imaging (reduced GLS) refine risk beyond LVEF and help identify phenotypes at higher arrhythmic or heart-failure risk despite apparently preserved ejection fraction [

9,

14]. In practice, individualized risk models that combine clinical variables (age, symptoms, AF), imaging (LVEF, LGE, GLS, non-apical extension), and genotype support decisions on surveillance intensity, ICD consideration, anticoagulation, and exercise restrictions [

10,

16,

17,

18,

19].

Table 6.

This table integrates imaging, electrical, and genetic markers that modify prognosis in LVNC. LGE is a reproducible tissue marker linked to ≈2-fold higher adverse events independently of LVEF [

9,

15]. LVEF ≤ 35% after optimized guideline-directed therapy remains the cornerstone threshold for primary-prevention ICD in non-ischemic cardiomyopathy [

16,

17,

18], while extensive/ring-like LGE and non-apical extension of trabeculation signal higher risk and justify intensified rhythm surveillance and earlier device consideration [

9,

10,

15]. Genotype can up- or down-shift risk; LMNA variants exemplify conduction disease and arrhythmic vulnerability that lower the ICD threshold when combined with imaging or clinical risk features [

4,

7,

10]. Reduced GLS often precedes overt LVEF decline and, together with LGE, refines risk in “preserved-EF” phenotypes [

14]. Thromboembolic risk rises with AF and apical thrombus and mandates anticoagulation, preferably with a DOAC unless a visible thrombus or contraindication dictates VKA [

10,

16]. Table created de novo by the authors from published data; no third-party figures were reproduced.

Table 6.

This table integrates imaging, electrical, and genetic markers that modify prognosis in LVNC. LGE is a reproducible tissue marker linked to ≈2-fold higher adverse events independently of LVEF [

9,

15]. LVEF ≤ 35% after optimized guideline-directed therapy remains the cornerstone threshold for primary-prevention ICD in non-ischemic cardiomyopathy [

16,

17,

18], while extensive/ring-like LGE and non-apical extension of trabeculation signal higher risk and justify intensified rhythm surveillance and earlier device consideration [

9,

10,

15]. Genotype can up- or down-shift risk; LMNA variants exemplify conduction disease and arrhythmic vulnerability that lower the ICD threshold when combined with imaging or clinical risk features [

4,

7,

10]. Reduced GLS often precedes overt LVEF decline and, together with LGE, refines risk in “preserved-EF” phenotypes [

14]. Thromboembolic risk rises with AF and apical thrombus and mandates anticoagulation, preferably with a DOAC unless a visible thrombus or contraindication dictates VKA [

10,

16]. Table created de novo by the authors from published data; no third-party figures were reproduced.

| Marker |

Evidence/association |

Clinical implications |

| LGE present |

≈2-fold higher risk of adverse events across LVNC cohorts, independent of LVEF [9,15] |

Closer follow-up; consider ICD when combined with low LVEF, high arrhythmic burden, or high-risk genotype |

| LVEF ≤ 35% after optimized GDMT |

Standard high-risk threshold in non-ischemic cardiomyopathy [16,17,18] |

Primary-prevention ICD per guidelines; optimize GDMT and consider CRT if criteria are met |

| Extensive or ring-like LGE |

Higher arrhythmic/MACE risk in cardiomyopathy populations, signal reproduced in LVNC series [9,15] |

Prioritize device therapy and rhythm surveillance; cautious approach to high-intensity sports |

| Non-apical extension of trabeculation |

Tracks with adverse remodeling and events in observational LVNC cohorts [10] |

Tighter surveillance; integrate with LGE/LVEF/GLS and genotype to guide ICD decisions |

| High-risk genotype (e.g., LMNA) |

Early conduction disease and ventricular arrhythmias; higher SCD risk [4,7,10] |

Lower threshold for ICD; ambulatory rhythm monitoring; family screening |

| Reduced GLS (impaired deformation) |

Identifies subclinical dysfunction and correlates with fibrosis/bad outcomes [14] |

Escalate follow-up and GDMT even if LVEF is “preserved”; consider CMR if not already done |

| Atrial fibrillation / apical thrombus |

Increased thromboembolic risk in LVNC cohorts [10] |

Anticoagulation (DOAC preferred; VKA if apical thrombus or DOAC contraindication) |

7. Treatment

Management of LVNC largely adapts evidence from non-ischemic cardiomyopathy and heart failure, tailoring decisions to tissue injury, arrhythmic burden, thromboembolic risk, and genotype. In asymptomatic individuals with preserved systolic function and

no injury markers (no LGE, normal GLS, no significant arrhythmias), a conservative strategy with periodic clinical review, ECG/ambulatory monitoring, and repeat imaging is appropriate. Once heart failure symptoms or systolic dysfunction develop, initiate

guideline-directed medical therapy (GDMT) with an ACE inhibitor or ARB or

sacubitril–valsartan, a

beta-blocker, a

mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist, and an

SGLT2 inhibitor, titrating to guideline targets as tolerated [

16]. After ≥3 months of optimized therapy, patients with

LVEF ≤ 35% should be considered for

primary-prevention ICD following major society recommendations for non-ischemic cardiomyopathy; in those with left bundle branch block and

QRS ≥ 130 ms,

cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT) is indicated per guideline criteria [

16,

17,

18]. Independent of LVEF, patients with sustained VT/VF or syncope with documented malignant arrhythmias merit device evaluation;

LGE burden,

GLS impairment,

non-apical extension of trabeculation, and

high-risk genotypes (e.g., LMNA) lower the threshold for device implantation when combined with clinical risk [

9,

10,

15,

17,

18,

19].

Anticoagulation is recommended for atrial fibrillation according to thromboembolic risk scores;

DOACs are generally preferred, whereas

VKA is indicated when

apical thrombus is present or DOACs are contraindicated [

16,

23]. Routine anticoagulation in the absence of AF or thrombus is not supported; decisions should consider recess depth, prior embolism, and global risk.

Catheter ablation can reduce recurrent VT when performed in experienced centers using substrate-guided strategies adapted to trabeculated anatomy [

19].

Surgical resection of non-compacted myocardium has been reported in highly selected cases with symptomatic improvement and LVEF gain, but evidence remains limited and patient selection is critical [

20]. In

advanced heart failure, durable

LVAD support and

cardiac transplantation are established options; outcomes mirror those of other non-ischemic etiologies.

Follow-up intensity is individualized. A reasonable framework is clinical evaluation and imaging every

6 months during the first year after diagnosis or therapy changes, then

annually if stable, with earlier reassessment when new symptoms, arrhythmias, or biomarker/imaging changes appear.

Exercise: recreational moderate-intensity activity is acceptable in the absence of fibrosis, significant arrhythmias, or systolic dysfunction; participation in high-intensity or competitive sports should follow shared decision-making informed by LVEF, LGE, arrhythmia burden, and genotype [

10,

16,

17,

18].

Pregnancy: most women with preserved function and no injury markers tolerate pregnancy, but pre-pregnancy counseling and close surveillance are advisable; postpartum reassessment is recommended when hypertrabeculation appears during gestation [

5]. Telemonitoring (rhythm and congestion) can support earlier intervention and reduce hospitalizations in selected patients [

16].

Table 7.

This table consolidates therapeutic decisions for LVNC by aligning heart-failure frameworks with LVNC-specific risk modifiers. GDMT remains foundational for symptomatic patients and those with reduced LVEF [

16]. ICD and CRT indications follow non-ischemic cardiomyopathy guidance, with thresholds individualized by LGE, GLS, non-apical extension, and genotype (e.g., LMNA) when risk is borderline [

9,

10,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19]. Anticoagulation is mandatory for AF and for apical thrombus (prefer VKA when thrombus is present); DOACs are preferred otherwise [

16,

23]. Catheter ablation reduces VT recurrence in selected LVNC patients [

19]; LVAD and transplantation are options in advanced disease, while surgical resection of non-compacted myocardium is reserved for exceptional, highly selected cases with limited evidence [

20]. Table created de novo by the authors from published data; no third-party figures were reproduced.

Table 7.

This table consolidates therapeutic decisions for LVNC by aligning heart-failure frameworks with LVNC-specific risk modifiers. GDMT remains foundational for symptomatic patients and those with reduced LVEF [

16]. ICD and CRT indications follow non-ischemic cardiomyopathy guidance, with thresholds individualized by LGE, GLS, non-apical extension, and genotype (e.g., LMNA) when risk is borderline [

9,

10,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19]. Anticoagulation is mandatory for AF and for apical thrombus (prefer VKA when thrombus is present); DOACs are preferred otherwise [

16,

23]. Catheter ablation reduces VT recurrence in selected LVNC patients [

19]; LVAD and transplantation are options in advanced disease, while surgical resection of non-compacted myocardium is reserved for exceptional, highly selected cases with limited evidence [

20]. Table created de novo by the authors from published data; no third-party figures were reproduced.

| Clinical situation |

Recommended strategy |

Practical notes / triggers |

| Asymptomatic, preserved LVEF, no injury markers |

Periodic follow-up: annual echo or CMR + ambulatory monitoring |

Defer label/device; escalate only if LGE/GLS abnormality, arrhythmias, or remodeling appear [9,14] |

| Symptomatic HFrEF or LVEF ↓ |

GDMT: ACEi/ARB or ARNI + beta-blocker + MRA + SGLT2i |

Titrate to guideline doses as tolerated; manage congestion; cardiac rehab improves capacity [16] |

| LVEF ≤ 35% despite ≥3 months GDMT |

ICD for primary prevention |

Consider CRT if LBBB with QRS ≥ 130 ms; integrate LGE/GLS/genotype for borderline cases [16,17,18] |

| Sustained VT/VF or syncope with malignant arrhythmias |

ICD ± catheter ablation |

Substrate-guided ablation can reduce VT recurrence; experienced centers recommended [17,18,19] |

| Atrial fibrillation or prior embolism |

Anticoagulation (DOAC preferred) |

VKA if apical thrombus present or DOAC contraindicated; image to confirm thrombus [16,23] |

| High-risk genotype (e.g., LMNA) with additional risk features |

Lower threshold for device therapy |

Combine genotype with LGE/GLS, conduction disease, family history to personalize ICD decision [4,7,10] |

| Advanced heart failure |

LVAD or transplantation |

Outcomes comparable to other NICM etiologies; rare surgical resection in selected LVNC cases [20] |

| Return to sport / lifestyle |

Shared decision-making based on LVEF, LGE, arrhythmias, genotype |

Recreational moderate exercise acceptable if no injury markers; restrict competitive sports if high risk [10,16,17,18] |

8. Differential Diagnosis

Several entities can meet echocardiographic or CMR thresholds for LVNC yet represent distinct phenotypes with different prognoses and management. Physiological hypertrabeculation is common in athletes and during late pregnancy and often regresses once the hemodynamic trigger is removed; in these settings, preserved LVEF and absent LGE favor a benign course [

5,

6]. Apical hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) can mimic non-compaction due to apical thickening and a spade-like cavity but typically shows a thick compact layer and characteristic LGE distribution. Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy (ARVC) primarily affects the right ventricle with depolarization/repolarization abnormalities and desmosomal variants; biventricular forms can blur boundaries but differ in electro-anatomic substrate and risk management. Infiltrative/storage diseases such as amyloidosis and Fabry disease produce distinct tissue signatures (e.g., low native T1 and inferolateral mid-wall LGE in Fabry) and systemic features that guide testing and therapy [

4,

7,

14]. Tachycardia-induced cardiomyopathy and other high-output states may cause reversible remodeling; controlling the trigger and reassessing structure/function prevents mislabeling. A multiparametric approach combining morphology with

injury markers (LGE, reduced LVEF/GLS) and clinical-genetic context improves specificity and reduces over-diagnosis [

9,

12,

13,

14].

Table 8.

This table outlines conditions that can satisfy LVNC thresholds yet have different pathophysiology and management. In athletes and pregnancy, hypertrabeculation is frequently reversible and rarely accompanied by injury markers (LGE, reduced LVEF/GLS) [

5,

6]. Apical HCM shows a thick compact layer and a characteristic CMR fibrosis pattern; ARVC presents a right-dominant arrhythmogenic substrate; Fabry shows low native T1 and systemic features; and amyloidosis has diffuse infiltration on CMR. When morphology is borderline, pairing injury markers with genotype/clinical context improves diagnostic specificity and helps avoid overdiagnosis [

9,

12,

13,

14]. Table created de novo by the authors; no third-party figures were reproduced.

Table 8.

This table outlines conditions that can satisfy LVNC thresholds yet have different pathophysiology and management. In athletes and pregnancy, hypertrabeculation is frequently reversible and rarely accompanied by injury markers (LGE, reduced LVEF/GLS) [

5,

6]. Apical HCM shows a thick compact layer and a characteristic CMR fibrosis pattern; ARVC presents a right-dominant arrhythmogenic substrate; Fabry shows low native T1 and systemic features; and amyloidosis has diffuse infiltration on CMR. When morphology is borderline, pairing injury markers with genotype/clinical context improves diagnostic specificity and helps avoid overdiagnosis [

9,

12,

13,

14]. Table created de novo by the authors; no third-party figures were reproduced.

| Entity |

Distinguishing clues |

Tests that help |

What rules LVNC in/out |

| Physiological hypertrabeculation (athletes, pregnancy) |

Preserved LVEF; no LGE; reversible after trigger |

De-training or postpartum reassessment |

Regression and absence of injury markers argue against LVNC [5,6,9] |

| Apical HCM |

Apical hypertrophy; spade-like cavity |

CMR wall thickness; characteristic LGE |

Thick compact layer favors HCM over LVNC; pattern of fibrosis differs |

| Fabry disease |

Neuropathic pain; cornea verticillata; proteinuria |

Low native T1; GLA testing |

Storage-disease pattern and inferolateral LGE point away from LVNC [4,14] |

| ARVC |

RV-dominant phenotype; epsilon waves; desmosomal variants |

RV-focused CMR criteria; genetic testing |

Predominant RV substrate distinguishes from classic LVNC |

| Cardiac amyloidosis |

Low-voltage ECG; diffuse subendocardial LGE |

Bone-avid tracers; biopsy as indicated |

Diffuse infiltration rather than trabecular morphology |

| Tachycardia-induced cardiomyopathy |

Persistent tachyarrhythmia; reversibility |

Rhythm control; remodeling on follow-up |

Structural/functional recovery argues against LVNC |

9. Future Directions and Open Questions

Diagnostic thresholds and risk models for LVNC need prospective validation that accounts for age, sex, ethnicity, and loading conditions. First, criteria standardization should test whether age- and sex-adjusted NC/C or trabeculated-mass cutoffs, when paired with injury markers (LGE, GLS, compact-layer thickness), discriminate pathological from physiological hypertrabeculation across athletes, pregnancy, and high-output states [

9,

12,

13,

14]. Second, genotype-informed risk warrants integration into device and anticoagulation decisions, particularly for high-risk variants such as LMNA, in combination with imaging markers and arrhythmic burden [

4,

7,

10]. Third, advanced imaging and AI-assisted analysis (e.g., 3D CMR segmentation, radiomics, deformation mapping) may improve phenotyping and prediction beyond conventional metrics and should be evaluated in multicenter cohorts with hard outcomes [

14,36]. Fourth, therapeutic trials should test whether early institution of SGLT2 inhibitors or other cardioprotective agents in asymptomatic genotype-positive individuals can delay fibrosis or adverse remodeling. Fifth, pediatric-to-adult transition research should define progression markers and optimal surveillance intervals, ideally through genotype-enriched registries. Finally, global implementation studies must identify simplified imaging protocols and affordable genetic panels that deliver value in resource-limited settings, enabling equitable precision cardiology [38].

10. Conclusions

Left ventricular non-compaction cardiomyopathy (LVNC) is best framed as a structural phenotype within a cardiomyopathic continuum rather than a single discrete disease. Echocardiographic and CMR-based morphological thresholds identify the phenotype with reasonable reproducibility, but in low pretest-probability settings such as athletes and late pregnancy the positive predictive value is limited and the risk of overdiagnosis is non-trivial. Diagnostic certainty increases when morphology is paired with injury markers that reflect tissue damage or pump impairment, notably late gadolinium enhancement, reduced ejection fraction or impaired deformation, malignant arrhythmias, or thromboembolism. This multiparametric stance aligns with the underlying biology, where genotype, loading conditions, and mechanobiology interact to shape expression over time.

Clinically, presentation ranges from incidental imaging findings with preserved function to overt heart failure and malignant ventricular arrhythmias. In asymptomatic individuals without injury markers, a conservative strategy that avoids premature labeling and emphasizes periodic surveillance is appropriate. Pregnancy- and training-related hypertrabeculation frequently regresses once the hemodynamic trigger resolves; reassessment 6–12 months postpartum or after a short period of de-training is recommended before assigning a permanent diagnosis. Pediatric LVNC often coexists with congenital or metabolic disease and requires tailored longitudinal plans through the transition to adult care. Across ages, prognosis is driven more by tissue injury and pump function than by trabecular ratios alone; non-apical extension of trabeculation and impaired deformation add granularity for risk stratification even when ejection fraction appears preserved.

Genetics informs both diagnosis and prognosis. Sarcomeric variants connect LVNC with dilated and hypertrophic cardiomyopathies, while nuclear-envelope and conduction-gene variants associate with early conduction disease and ventricular arrhythmias and may lower the threshold for device therapy when combined with imaging or clinical risk features. Genetic testing should be targeted and interpreted within the clinical and imaging context; cascade screening identifies at-risk relatives and clarifies surveillance needs. Advanced imaging and emerging analytics may refine phenotyping and prediction beyond conventional metrics, but require prospective validation with hard outcomes before routine adoption.

Management aligns with non-ischemic cardiomyopathy frameworks. Symptomatic or reduced-ejection-fraction phenotypes merit guideline-directed medical therapy including renin–angiotensin system inhibition or sacubitril–valsartan, beta-blockade, mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists, and SGLT2 inhibitors, titrated to targets as tolerated. After at least three months of optimized therapy, an ejection fraction at or below 35% supports consideration of primary-prevention defibrillator therapy; cardiac resynchronization is indicated in the presence of left bundle branch block and QRS prolongation according to guideline criteria. Independent of ejection fraction, sustained ventricular arrhythmias, extensive or ring-like fibrosis, non-apical extension of trabeculation, high arrhythmic burden, or high-risk genotypes justify earlier device discussion in shared decision-making. Anticoagulation follows standard indications for atrial fibrillation and for documented apical thrombus; catheter ablation can reduce recurrent ventricular tachycardia in selected cases; advanced therapies such as ventricular assist devices and transplantation remain options in end-stage disease, while surgical resection of non-compacted myocardium is exceptional and supported by limited evidence.

Taken together, these data support a standardized, two-step diagnostic framework: first, confirm morphology with attention to technical pitfalls and pretest probability; second, establish disease by demonstrating injury or a plausible high-risk genotype. Care should be personalized by integrating clinical variables, imaging markers, and genotype to calibrate surveillance intensity, device thresholds, anticoagulation, exercise counseling, pregnancy management, and family screening.

Funding

No external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and drafting, L.E.M.T.; methodology and critical review, X.B.H.; clinical review, E.K.; final review and integration, F.R.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors created all summary tables de novo from published data and did not reproduce third-party figures. They reviewed and edited the manuscript and take responsibility for its content.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript.

| LVNC |

Left-ventricular non-compaction cardiomyopathy |

| CMR |

Cardiac magnetic resonance |

| LGE |

Late gadolinium enhancement |

| LVEF |

Left-ventricular ejection fraction |

| ICD |

Implantable cardioverter-defibrillator |

| CRT |

Cardiac resynchronisation therapy |

| SGLT2i |

Sodium–glucose co-transporter-2 inhibitor |

| DCM |

Dilated cardiomyopathy |

| HCM |

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy |

| NC/C |

Non-compacted/compacted ratio |

| NT-proBNP |

N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide |

References

- Grigoratos, C.; Barison, A.; Ivanov, A.; Andreini, D.; Amzulescu, M.S.; Mazurkiewicz, L.; et al. Prognostic role of late gadolinium enhancement and global systolic impairment in left ventricular non-compaction: A meta-analysis. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging 2019, 12, 2141–2151, Google Scholar CrossRef PubMed. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J Zhou, Z.-Q.; He, W.-C.; Li, X.; Bai, W.; Huang, W.; Hou, R.-L.; Wang, Y.-N.; Guo, Y.-K. Comparison of cardiovascular magnetic resonance characteristics and clinical prognosis in left ventricular non-compaction patients with and without arrhythmia. BMC Cardiovascular Disorders. 2022, 22, 25, Google Scholar CrossRef PubMed. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izquierdo, C.; Casas, G.; Martin-Isla, C.; Campello, V.M.; Guala, A.; Gkontra, P.; Rodríguez-Palomares, J.F.; Lekadir, K. Radiomics-Based Classification of Left Ventricular Non-Compaction, Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy, and Dilated Cardiomyopathy in Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2021, 8, 764312, Google Scholar CrossRef PubMed. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, T.K.; Perloff, J.K.; Williams, R.G.; Jue, K.; Mohrmann, R. Isolated noncompaction of left ventricular myocardium: A study of eight cases. Circulation 1990, 82, 507–513, Google Scholar CrossRef PubMed. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petersen, S.E.; Selvanayagam, J.B.; Wiesmann, F.; Robson, M.D.; Francis, J.M.; Anderson, R.H.; et al. Left ventricular non-compaction: Insights from cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2005, 46, 101–105, Google Scholar CrossRef PubMed. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jenni, R.; Oechslin, E.; Schneider, J.; Attenhofer Jost, C.; Kaufmann, P.A. Echocardiographic and pathoanatomical characteristics of isolated left ventricular non-compaction: A step towards classification as a distinct cardiomyopathy. Heart 2001, 86, 666–671, Google Scholar CrossRef PubMed. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aras, D.; Tufekcioglu, O.; Ergun, K.; Ozeke, O.; Yildiz, A.; Topaloglu, S.; et al. Clinical features of isolated ventricular non-compaction in adults: Long-term clinical course and predictors of left ventricular failure. J. Card. Fail. 2006, 12, 726–733, Google Scholar CrossRef PubMed. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, S.B.; Jones, K.; Blanch, B.; Barratt, A.; Semsarian, C.; Ingles, J. Prevalence of left ventricular non-compaction in adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. Heart J. 2020, 41, 1428–1436, Google Scholar CrossRef PubMed. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzarotto, F.; Hawley, M.H.; Beltrami, M.; Beekman, L.; de Marvao, A.; McGurk, K.A.; et al. Systematic large-scale assessment of the genetic architecture of left ventricular noncompaction reveals diverse etiologies. Genet Med. 2021, 23, 856–864, Google Scholar CrossRef PubMed. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casas, G.; Rodríguez-Palomares, J.F.; Ferreira-González, I. Left ventricular noncompaction: a disease or a phenotypic trait? Revista Española de Cardiología. 2022, 75, 1059–1069, Google Scholar CrossRef PubMed. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhan, O.; Demir, E.; Dogdus, M.; Ozerkan Cakan, F.; Nalbantgil, S. Speckle Tracking Echocardiography and Left Ventricular Twist Mechanics: Predictive Capabilities for Non-Compaction Cardiomyopathy in First-Degree Relatives. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2021, 37, 429–438, Google Scholar CrossRef PubMed. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerecke, G.; Engberding, R. Left ventricular non-compaction: Genesis, diagnosis, prognosis, therapy. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 2457, Google Scholar CrossRef. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDonagh, T.A.; Metra, M.; Adamo, M.; et al. 2021 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure. Eur. Heart J. 2021, 42, 3599–3726, Google Scholar CrossRef PubMed. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayourian, J.; Asztalos, I.B.; El-Bokl, A.; Lukyanenko, P.; Kobayashi, R.L.; La Cava, W.G.; et al. Electrocardiogram-based deep learning to predict left-ventricular systolic dysfunction in paediatric and adult congenital heart disease: a multicentre modelling study. Lancet Digital Health. 2025, 7, e264–e274, Google Scholar CrossRef PubMed. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacquier, A.; Thuny, F.; Jop, B.; Giorgi, R.; Cohen, F.; Gaubert, J.Y.; et al. Measurement of trabeculated left ventricular mass using cardiac MRI in the diagnosis of left ventricular non-compaction. Eur. Heart J. 2010, 31, 1098–1104, Google Scholar CrossRef PubMed. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oechslin, E.N.; Attenhofer Jost, C.H.; Rojas, J.R.; Kaufmann, P.A.; Jenni, R. Long-term follow-up of adults with isolated left ventricular non-compaction. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2000, 36, 493–500, Google Scholar CrossRef PubMed. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habib, G.; Charron, P.; Eicher, J.C.; Giorgi, R.; Baron, O.; Jondeau, G.; et al. Isolated left ventricular non-compaction in adults: Clinical and echocardiographic features in 105 patients. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2011, 13, 177–185, Google Scholar CrossRef PubMed. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casas, G.; Limeres, J.; Oristrell, G.; Gutierrez-Garcia, L.; Andreini, D.; Borregan, M.; et al. Clinical risk prediction in patients with left-ventricular myocardial non-compaction. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2021, 78, 643–662, Google Scholar CrossRef PubMed. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Towbin, J.A.; Lorts, A.; Jefferies, J.L. Left ventricular non-compaction cardiomyopathy. Lancet 2015, 386, 813–825, Google Scholar CrossRef PubMed. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lofiego, C.; Biagini, E.; Pasquale, F.; Ferlito, M.; Rocchi, G.; Perugini, E.; et al. Wide spectrum of presentation and variable outcomes of isolated left ventricular non-compaction. Heart 2007, 93, 65–71, Google Scholar CrossRef PubMed. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohli, S.K.; Pantazis, A.A.; Shah, J.S.; Adeyemi, B.; Robinson, S.; McKenna, W.J.; et al. Diagnosis of left-ventricular non-compaction in patients with left-ventricular systolic dysfunction: Time for a reappraisal of diagnostic criteria? Eur. Heart J. 2008, 29, 89–95, Google Scholar CrossRef PubMed. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogah, O.S.; Iyawe, E.P.; Okwunze, K.F.; Nwamadiegesi, C.A.; Obiekwe, F.E.; Fabowale, M.O.; et al. Left ventricular noncompaction cardiomyopathy: a scoping review. Ann Ib Postgrad Med. 2023, 21, 8–16, Google Scholar CrossRef PubMed. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Huang, W.; Sun, R.; Liu, W.; Xu, R.; Zhou, Z.; Bai, W.; et al. Prognostic Value of Late Gadolinium Enhancement in Left Ventricular Noncompaction: A Multicenter Study. Diagnostics. 2022, 12, 2457, Google Scholar CrossRef PubMed. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rojanasopondist, P.; Nesheiwat, L.; Piombo, S.; Porter, G.A.; Ren, M.; Phoon, C.K.L. Genetic basis of left ventricular noncompaction. Circ Genom Precis Med. 2022, 15, e003517, Google Scholar CrossRef PubMed. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huttin, O.; Venner, C.; Frikha, Z.; Voilliot, D.; Marie, P.-Y.; Aliot, E.; et al. Myocardial deformation pattern in left-ventricular non-compaction: comparison with dilated cardiomyopathy. IJC Heart & Vessels. 2014, 5, 9–14, Google Scholar CrossRef PubMed. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, W.Y.; Moreno-Betancur, M.; Nugent, A.W.; Cheung, M.; Colan, S.D.; Turner, C.; et al. Long-Term Outcomes of Childhood Left Ventricular Non-Compaction Cardiomyopathy: Results From a National Population-Based Study. Circulation. 2018, 138, 367–376, Google Scholar CrossRef PubMed. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacquier, A.; Thuny, F.; Jop, B.; Giorgi, R.; Cohen, F.; Gaubert, J.-Y.; et al. Measurement of trabeculated left-ventricular mass using cardiac MRI in the diagnosis of left-ventricular non-compaction. European Heart Journal. 2010, 31, 1098–1104, Google Scholar CrossRef PubMed. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilde, A.A.M.; Semsarian, C.; Márquez, M.F.; Shamloo, A.S.; Ackerman, M.J.; Ashley, E.A.; et al. European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA)/Heart Rhythm Society (HRS)/Asia Pacific Heart Rhythm Society (APHRS)/Latin American Heart Rhythm Society (LAHRS) Expert Consensus Statement on the State of Genetic Testing for Cardiac Diseases. Heart Rhythm. 2022, 19, e1–e60, Google Scholar CrossRef PubMed. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Chica, J.A.; Gómez-Talavera, S.; García-Ruiz, J.M.; et al. Association Between Left Ventricular Non-compaction and Vigorous Physical Activity. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2020, 76, 1723–1733, Google Scholar CrossRef PubMed. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirono, K.; Takarada, S.; Miyao, N.; Nakaoka, H.; Ibuki, K.; Ozawa, S.; Origasa, H.; Ichida, F. Thromboembolic events in left-ventricular non-compaction: comparison between children and adults — a systematic review and meta-analysis. Open Heart. 2022, 9, e001908, Google Scholar CrossRef PubMed. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inglis, S.C.; Conway, A.; Cleland, J.G.F.; et al. Remote monitoring to reduce hospitalizations in heart failure: An updated meta-analysis. Eur. Heart J. 2016, 37, 3144–3151, CrossRef. [Google Scholar]

- McDonagh, T.A.; Metra, M.; Adamo, M.; et al. 2021 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure. Eur. Heart J. 2021, 42, 3599–3726, Google Scholar CrossRef PubMed. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sethi, Y.; Patel, N.; Kaka, N.; et al. Precision medicine and the future of cardiovascular diseases: a clinically oriented comprehensive review. J Clin Med. 2023, 12, 1799, Google Scholar CrossRef PubMed. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pittorru, R.; Corrado, D. Left ventricular non-compaction: evolving concepts. J Clin Med. 2024, 13, 5674, Google Scholar CrossRef PubMed. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varasteh, Z.; Mohanta, S.; Robu, S.; Braeuer, M.; Li, Y.; Omidvari, N.; et al. Molecular imaging of fibroblast activity after myocardial infarction using a ^68Ga-labeled fibroblast-activation protein inhibitor (FAPI-04). Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 2019, 60, 1743–1749, Google Scholar CrossRef PubMed. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).