Introduction

Functional foods and nutritional interventions usually contain beneficial microorganisms that can be consumed orally as probiotics. This applies to both people and livestock animals that are given microorganisms directly to enhance health and reduce pathogen loads.

Food and Agriculture Association of the United Nations (FAO) and World Health Organisation (WHO) define probiotics as 'live microorganisms which when administered in adequate amounts confer a health benefit on the host (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. and World Health Organization. 2006). Several Lactobacillus species, Bifidobacterium species, Saccharomyces boulardii, and other microbes have been proposed and are used as probiotic strains (Ljungh and Wadström 2001). Due to their long history of use in conjunction with fermented foods, lactic acid bacteria (LAB) are generally recognized as safe, functional, and active food ingredients. Their metabolic byproducts, like lactic acid and bacteriocin, can also be used as natural preservatives and antimicrobial agents to prevent contamination and food spoilage (Chuah et al. 2019). In general, a probiotic isolated from one animal performs less well in another animal. However, because many probiotics are of unknown origin, probiotic use across species is widespread (Goldin 1998). The human body contains thousands of different types of microorganisms, but the presence of harmful microbes leads to a variety of diseases and illnesses because toxic substances build up during digestion as a result of the bad microbes. The immune system begins to weaken at this point. In these circumstances, consuming probiotics in higher doses is an alternative to using antibiotics to treat the issue(Reid et al. 2003). According to studies, probiotics can improve lactose tolerance, lower cholesterol, modulate immunity, and even prevent some cancers (Adhikari et al. 2000). The most used probiotic strains are Lactobacillus and Bifidobacteria; to be effective in promoting health, the population of viable bacteria must be greater than 107 CFU/mL or g end products at the time of consumption (Adhikari et al. 2000). A potential probiotic strain is predicted to possess several desirable traits to exert its beneficial effects. The probiotic’s functional requirements should be determined using in vitro techniques. It must be able to function in the gut environment, survive through the upper gastrointestinal (GI) tract, arrive alive at its site of action and has a reputation for not being pathogenic. Also, it has no antibiotic-resistance genes that can be passed on (Kechagia et al. 2013; Saarela et al. 2000). However, several factors, including pH, hydrogen peroxide, oxygen, and storage temperature, have been reported to affect probiotic viability (Shah et al. 1995). Several approaches for increasing the resistance of these sensitive microorganisms to adverse conditions have been proposed, including the use of oxygen-impermeable containers, two-step fermentation, stress adaptation, incorporation of micronutrients such as peptides and amino acids, and encapsulation (Sarkar 2010). Encapsulation is one of the most efficient methods and has received special consideration and investigation. Encapsulation is the process of retaining cells within an encapsulating membrane to reduce cell loss in a way that results in the release of appropriate microorganisms in the gut (Sultana et al. 2000). Some advantages of cell microencapsulation include: protection from bacteriophages and harmful factors, increased survival during freezing, storage, and converting them into a powder form that is easier to use because it improves their homogeneous distribution throughout the product (Mortazavian et al. 2007).

The purpose of this article is to review the health advantages and therapeutic potential of probiotics, the methods and matrices used for their encapsulation and their benefits

Health Advantages and Therapeutic Potential of Probiotics

Probiotics’ beneficial effects on human health are diverse and exerted through a variety of complex mechanisms, and these effects can be local or systemic (extraintestinal effects). Research suggests that certain variations in the composition of the gut microbiota are linked to a variety of diseases (Finegold et al. 2010; Kalliomäki et al. 2008). To identify the microbiota imbalance in human diseases like inflammatory bowel disease or obesity, this was confirmed by comparing the microbiomes of healthy individuals with those of diseased individuals (Qin et al. 2010; Turnbaugh et al. 2009). Some of the health advantages and therapeutic potential of lactobacillus strains are discussed below, with an emphasis on in vivo and clinical trials.

Probiotics and Immune Response

The ability of probiotic bacteria to modulate the immune system is well established. The probiotics can interact with lymphocytes, dendritic cells (DCs), monocytes/macrophages, and epithelial cells. The majority of pathogens share common structures called pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs), which are recognized by the innate immune system. In contrast, the adaptive immune response, which is highly specific for particular antigens, depends on B and T lymphocytes (Gómez-Llorente, Muñoz, and Gil 2010). Pattern recognition receptors (PPRS) that bind with pathogen-associated molecular patterns activate the initial defense against pathogens (PAMPs). Pattern recognition receptors have been the subject of extensive research. Typically, these receptors are toll-like receptors (TLRs). Extracellular C-type lectin receptors (CLRS) and intracellular nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-containing protein (NOD)-like receptors (NLRS) are known to transmit signals upon interaction with bacteria in addition to pattern recognition receptors (Lebeer, Vanderleyden, and De Keersmaecker 2010). The host cells that interact with probiotics are well-established to be intestinal epithelial cells (IECs). Probiotics may also come into contact with dendritic cells (DCs), which are important for both innate and adaptive immunity. Through their pattern recognition receptors, IECS and DCs can both react to gut microbes (Gómez-Llorente, Muñoz, and Gil 2010; Lebeer, Vanderleyden, and De Keersmaecker 2010). Probiotics can also alter the quality of intestinal mucins to prevent pathogen binding.

Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD)

Two idiopathic inflammatory bowel diseases are Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis. The gastrointestinal tract as a whole, from the mouth to the anus, can be affected by Crohn's disease, whereas ulcerative colitis is limited to the colon (Kawalec 2016). Patients with IBD frequently use probiotics, and their doctors frequently suggest them as an adjunctive treatment (Cheifetz et al. 2017). Although little is known about the mechanisms underlying probiotics' positive effects, these are probably immunomodulatory and anti-inflammatory, as evidenced by the expression of toll-like receptors and the down-regulation of inflammatory cytokines (Ng et al. 2010; Petrof et al. 2004). Lactiplantibacillus plantarum subsp can be found in the normal gut of healthy individuals as well as in a number of ecological niches like vegetables and fermented foods (Le and Yang 2018).

Anticancer Activity

Probiotic lactobacilli may activate anticancer mechanisms in the human gut by either preventing the carcinogenesis process or directly inhibiting the proliferation of cancer cells, as suggested by several in vitro studies (Haghshenas et al. 2014) (Kahouli, Tomaro-Duchesneau, and Prakash 2013; Tiptiri-Kourpeti et al. 2016). while some strains have been demonstrated to have powerful immunomodulating properties (El-Deeb et al. 2018; Tukenmez et al. 2019). Studies have shown that bacterial byproducts can change the environment in the gut and influence the development of cancer (Sungur et al. 2017; Zakostelska et al. 2011). By scavenging reactive intermediates and producing carcinogen-deactivating and antioxidative enzymes such as glutathione-S transferase (GTS), glutathione, glutathione reductase, glutathione peroxidase, superoxide dismutase, and catalase, LAB can reduce the activity of carcinogens such as Methylnitronitrosoguanidine (MNNG) and DMH (Liong 2008).

Effect on Cholesterol

Consumption of probiotics is expected to lower blood cholesterol levels. A high level of cholesterol in the bloodstream puts humans at risk of coronary heart disease (Kratz, Cullen, and Wahrburg 2002). Probiotics' cholesterol-lowering effects could be achieved through a variety of mechanisms, including bile acid deconjugation by bile salt hydrolase (BSH), cholesterol assimilation by probiotics, cholesterol co-precipitation with deconjugated bile, cholesterol binding to probiotic cell walls, and cholesterol incorporation into probiotic cellular membranes during growth (Ooi and Liong 2010).

Allergies and Probiotics Therapy

The possibility of getting a food allergy disease is increasing globally. Preventing allergies and treating them symptomatically are management strategies. According to reports, probiotics can help with the treatment and prevention of food allergies (Tan-Lim and Esteban-Ipac 2018). Lactic acid bacteria have been shown to be potential human therapeutic agents. They have been discovered to alter the human digestive system's intestinal microflora. The term "probiotics" refers to a living microorganism that promotes health, specifically lactic acid bacteria. Probiotics should be given to human newborns as a preventative measure to strengthen their immune systems. Nonetheless, an increasing number of studies have demonstrated the importance of the mother's microbial environment during pregnancy, and how it may influence the offspring's immune development even before birth. The lack of microflora in babies' intestines during the early stages of life causes their digestive systems to be disturbed. Perhaps this explains why pediatricians advise taking a probiotic to restore normalcy to the digestive system. Probiotics are a good, all-natural alternative for the prevention and treatment of many diseases because of their immunomodulatory qualities and safety in use. Additionally, allergic patients receive probiotic therapy for the treatment and future prevention of allergic issues (Haffner 2017; Zukiewicz-Sobczak et al. 2014).

Diabetes

Type 2 diabetes is a major modern disorder that costs governments a lot of money. Individual health is influenced by genetic and environmental factors. Individuals with this pathology have milder gut dysbiosis than patients with inflammatory bowel disease. However, there was a decrease in the proportion of the phylum Firmicutes and the Clostridia class (Larsen et al. 2010). Furthermore, butyrate-producing bacteria are declining, which may be linked to an increase in opportunistic pathogens. These bacteria have been shown to protect against a variety of diseases (J. Wang et al. 2012). Even more interesting is the increase in intestinal permeability seen in obese and diabetic mice when fed a high-fat diet (Cani et al. 2009). Such a diet results in a decrease in the presence of Bifidobacteria, which normally hydrolyzes intestinal lipopolysaccharides and, as a result, a less effective intestinal barrier function. (Griffiths et al. 2004; Z. Wang et al. 2006).

Active Biomolecules Produced by Lactic Acid Bacteria

Different antimicrobial, antiviral and antifungal substances, including organic acids, hydrogen peroxide, diacetyl, and antimicrobial peptides as bacteriocins, are known to be produced by various Lb. plantarum strains. Due to their potential use in food preservation to increase shelf life and reduce or even eliminate chemical additives, as requested by consumers, the choice of antagonistic strains has been extensively studied (Arena et al. 2016).

Bacteriocin

Bacteriocins are antibacterial peptides or proteins produced by bacteria such as Lactobacillus and Bifidobacteria. Bacteriocins have a high antibacterial activity and have been used by humans for thousands of years in the production of fermented foods. Bacteriocins are classified according to their size, mode of action, and inhibitory spectrum. Bacteriocins have many beneficial effects, including inhibiting the growth and development of pathogenic bacteria and being heat and pH resistant. Bacteriocins' antibacterial mechanism is primarily observed through their effect on bacterial cytoplasmic membranes. Bacteriocins are linked by affecting sensitive components such as bacterial peptides and inhibiting spore growth and pore formation in pathogenic bacteria's cell membrane (Gálvez et al. 2007; O’Connor et al. 2020).

Fatty Acid

Fatty acids are among the most important metabolites of probiotic bacteria. These compounds have numerous beneficial effects (such as antibacterial and antiviral properties). The antiviral effect of fatty acids is due to their unique structural properties. Fatty acids are made up of a saturated and unsaturated carbon chain that is joined by a carboxylic (hydrophilic) group. Lauric and meristic acids are two fatty acids that are particularly effective against bacterial growth and development. Short-chain fatty acids (FACs) produced by probiotic bacteria have become increasingly popular in recent years. Because of their high antibacterial activity, they can be used as suitable antibiotic alternatives (Churchward, Alany, and Snyder 2018; Mali et al. 2020).

Organic Acid

Organic acid from probiotics can be used as antimicrobial, antiviral agents. Organic acids are well-known as important postbiotics. The most important acids produced by probiotic bacteria are citric acid, acetic acid, and tartaric acid, all of which have strong antibacterial properties. Lactic acid, acetic acid, tartaric acid, malic acid, and citric acid inhibit pathogens by lowering pH significantly. Lactic acids' inhibitory effect is related to their effect on bacterial cell membranes. Organic acids' antibacterial mechanism is primarily observed by lowering intracellular pH and reducing membrane integrity. Lactic acid can be found in two isomers: L and D. The L-shape is better at preventing viral infections. Citric acid and acetic acid also prevent the infection of viruses by creating an acidic environment. The antiviral mechanism of organic acids produced by probiotic bacteria is observed through the binding of organic acids to the glycoprotein (S) of viruses, thereby preventing viruses from binding to the angiotensin-converting enzyme (Aljumaah et al. 2020; Churchward, Alany, and Snyder 2018; Gurung et al. 2020; Mani-López, García, and López-Malo 2012).

Hydrogen Peroxide

Hydrogen peroxide is produced primarily by all bacteria, but it is most visible in aerobic cultures of catalase-negative bacteria and is the major metabolite of lactic acid bacteria (Aljumaah et al. 2020). These substances have potent antiviral properties. These compounds disinfect materials by interacting with vital components of bacteria, fungi, and viruses, such as enzymes and nucleic acids (DNA and RNA), preventing replication and infection (Bidra et al. 2020).

Exopolysaccharide

EPSs are bacterial components produced by lactic acid bacteria (LAB) that have been shown to play an important role in probiotic activity such as survival, adhesion, and anti-tumor effect. LAB EPSs have a wide range of sugar compositions, which can be classified as homopolysaccharides (one type of monosaccharide) or heteropolysaccharides (a backbone of repeating units made up of two or more types of monosaccharides). LAB is primarily responsible for the production of heteropolysaccharides, which are composed of various sugars such as glucose, galactose, mannose, rhamnose, N-acetylglucosamine, and N-acetylgalactosamine (Sungur et al. 2017). Exopolysaccharide derived from Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactic as a postbiotic capable of antioxidant activity by increasing anti-oxidant enzyme levels (e.g., catalase, superoxide dismutase, and glutathione peroxidase activities) while decreasing lipid peroxidation (e.g., malondialdehyde) in mouse serum and livers (Guo et al. 2013).

Enzymes

Catalase

Catalase, a naturally occurring enzyme found in probiotics and other living organisms, degrades hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) into oxygen and water (He et al. 2019). Catalase is a Reductase Oxidase enzyme that suppresses ROS. As a result, it acts as an antioxidant and protects the cell from oxidative stress by inhibiting active oxygen species. Catalase is made up of four polypeptide chains, each of which contains more than 500 amino acids. It has four porphyrins (iron) in it that allow it to react with oxygenated water. The pH range for this enzyme's activity is 4-11 (Kleniewska and Pawliczak 2019; Yang et al. 2020).

Superoxide Dismutase

Superoxide dismutase can catalyze and facilitate the radical decomposition of superoxide (O2) molecules into ordinary oxygen (O2) or hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) molecules (Lin et al. 2020). In living organisms, there are three superoxide dismutase isoforms: cytosolic SOD1 (copper, zinc-SOD), mitochondrial SOD2 (Mn-SOD), and extracellular SOD3 (EC-SOD), each of which plays a different role in cell health. SOD1 protects the cytoplasm of cells, SOD2 protects the mitochondria of cells from free radical damage, and SOD3, as an antioxidant compound, plays an important role in the development of immunity against inflammatory diseases. With its antioxidant activity, this enzyme protects tissues from the effects of oxidative stress (Banerjee et al. 2019; Saqib et al. 2019) Superoxide dismutase is a critical enzyme in living organisms' antioxidant systems. Probiotics, like all living organisms, have this enzyme, which, as a probiotic metabolite, is a type of postbiotic that can be used as an antioxidant compound (Deeths et al. 2006; Korotkyi et al. 2019).

Glutathione Peroxidases

Glutathione peroxidases are an enzyme family with peroxidase activity whose main biological function is to protect organisms from oxidative damage. H2O2 is neutralized by glutathione peroxidase [

69]. Another important function of glutathione peroxidase is to convert peroxides to alcohol, thereby preventing the formation of free radicals, because cellular lipid compounds are sensitive to free radicals and produce lipid peroxide as a result of the reaction. Glutathione peroxidase isoenzymes are encoded by different genes (Ungati et al. 2019). These isoenzymes are distributed throughout the cell and have distinct substrate properties. Glutathione peroxidase 1 is the most abundant isoenzyme found in the cytoplasm of almost all mammalian tissues, and hydrogen peroxide is its preferred substrate (B. Chen et al. 2019). Glutathione peroxidase 2 is an extracellular enzyme found in the intestine. Glutathione peroxidase 3 is also extracellular and found in high concentrations in plasma. Glutathione peroxidase 4 prefers lipid hydroperoxides and is expressed in almost all mammalian cells, albeit at low levels (Aghebati-Maleki et al. 2022).

Encapsulation Techniques Used for Encapsulating Probiotics

Before delivering materials into a system, encapsulation can be thought of as a technique for enclosing materials into capsules. There are many encapsulation technologies available nowadays. Encapsulated materials can be created by packing bioactive molecules like enzymes, polyphenols, enzyme parts, antioxidants, and micronutrients inside wall materials. Encapsulation technology is referred to as micro- or nano-encapsulation, depending on the particle size (between 3 and 800 µm) (from 10 to 1000 nm). In addition to protecting bioactive substances from harmful environments, nano/microencapsulation can help deliver those substances directly to the target site, increasing their bioavailability (Reque and Brandelli 2021).

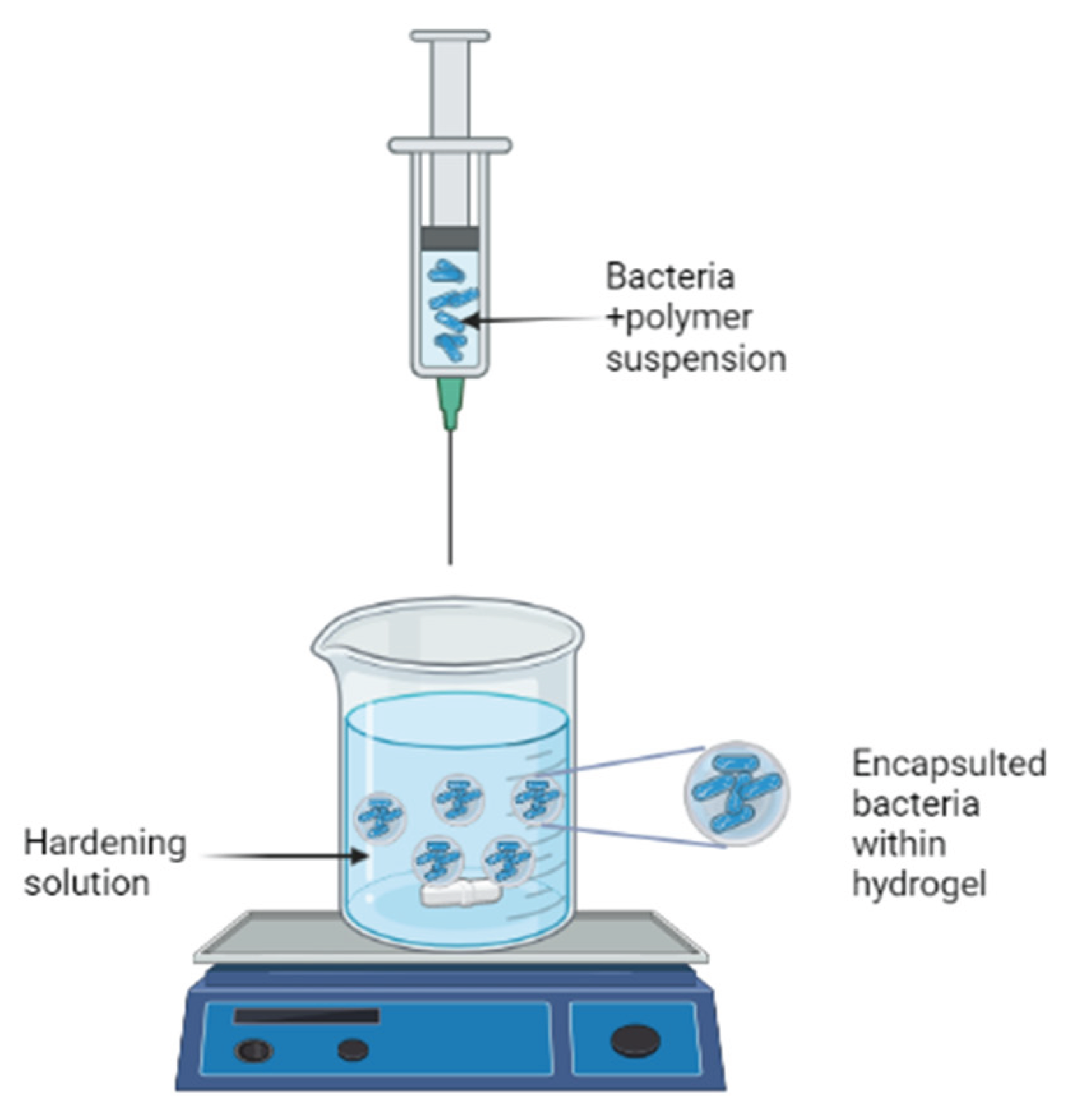

Extrusion

The most popular method is extrusion because of its simplicity, low cost, and gentle formulation conditions that ensure high cell viability (Krasaekoopt, Bhandari, and Deeth 2003). A hydrocolloid solution is simply made, microorganisms are added to it, and then the cell suspension is extruded through a syringe needle in the form of droplets to fall freely into a hardening solution or setting bath. The diameter of the needle and the length of free fall, respectively, determine the beads' size and shape (King 1995).

Figure 1.

Schematic presentation of the extrusion procedure. Created with BioRender.com.

Figure 1.

Schematic presentation of the extrusion procedure. Created with BioRender.com.

Emulsification

Emulsification is a chemical technique that uses hydrocolloids (alginate, carrageenan, and pectin) as encapsulating materials to encapsulate probiotic living cells. This technique's principle is based on the relationship between discontinuous and continuous phases. An emulsifier and a surfactant are required for encapsulation in an emulsion. Emulsifiers are used to make a more effective emulsion because they reduce surface tension, resulting in smaller particles. The emulsion is then treated with a solidifying agent (calcium chloride) (M. J. Chen and Chen 2007; Kailasapathy 2009; Martín et al. 2015; de Vos et al. 2010). The emulsion technique has a high rate of bacterial survival and is simple to scale up (M. J. Chen and Chen 2007).

Coacervation

Coacervation is a modified emulsification technology. The concept is straightforward. A complex is formed when a solution of bioactive components is combined with a matrix molecule of the opposite charge. The size and characteristics of the capsule can be altered by varying the pH, ion concentration, matrix molecule-to-bioactive component ratio, and matrix type. The technique is primarily driven by electrostatic interactions, but it also involves hydrophobic interactions. Furthermore, because this is an immobilization rather than an encapsulation technology, it is mostly proposed and used for bioactive food molecules rather than bioactive living cells. The method is used for flavors, oils, and some water-soluble bioactive molecules (de Vos et al. 2010).

Spray Drying

Spray drying is one of the industrial encapsulation techniques that are most frequently used. Both living probiotics and bioactive food molecules are being used in their application. When properly carried out, it is a quick and reasonably inexpensive procedure that is also very reproducible. The core is dissolved in a matrix material dispersion according to the spray drying principle. After that, the dispersion is atomized in heated air. This encourages the solvent to be removed quickly (water). Then, at the outlet, the powdered particles are separated from the drying air at a lower temperature. The widespread use of spray drying in industrial settings is primarily due to its relative simplicity and low cost. The technology does, however, have some significant drawbacks. The first is its limited range of use. Since it is an immobilization method rather than an encapsulation method, some biological components might be exposed. This is particularly troublesome when taking into account the method used to encapsulate probiotics, as the bacteria may leak into the product when some hydration takes place. Another drawback is the required high temperature for immobilization, which is incompatible with the survival of all probiotic species. Bifidobacteria, for instance, was found to be extremely sensitive to high inlet temperatures (O’Riordan et al. 2001).

Freeze Drying

Freeze-drying is a process that involves freezing the probiotic bacteria, usually in the presence of cryoprotectants, and sublimation of the water under a vacuum. The cryoprotectants increase microorganism survival and stabilize the product during storage. The lack of oxidation and water phase transition is the main advantage of this technique. This greatly increases the probiotic bacteria's survival rate. In comparison to spray drying, the equipment and operating costs are high (Blazheva et al. 2022).

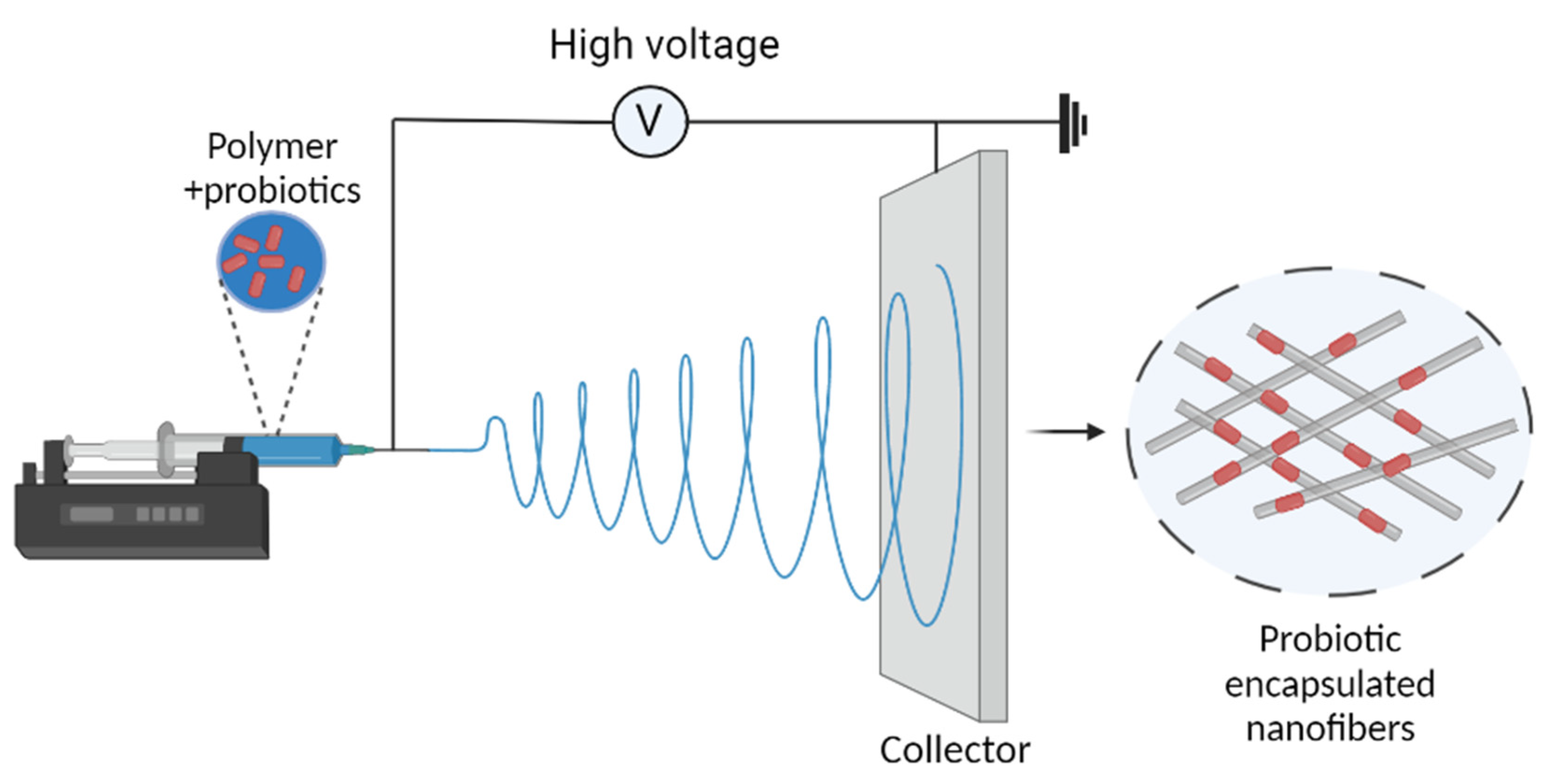

Electrospinning

Electrospinning is an electrohydrodynamic process in which a liquid droplet is electrified to create a jet, which is then stretched and elongated to create fibers (Deng and Zhang 2020). It has been used as an alternative encapsulation method for sensitive foods and bioactive substances in recent years due to its numerous advantages (Feng et al. 2018). It is a typical process for producing nanofibres with diameters of 100 nm or less (Salalha et al. 2006), which was initially introduced by Formhals in 1934 (Formhals 1934).

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of electrospinning.

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of electrospinning.

Matrices Used for the Encapsulation

Alginate

Alginate is a naturally derived polysaccharide made up of b-D-mannuronic and a-L-guluronic acids that are extracted from various algae species. The amount and sequential distribution of the polymer chain vary depending on the source of the alginate, and this influences the functional properties of alginate as a supporting material. Calcium alginate hydrogels are widely used in the encapsulation of cells because it is simple, non-toxic, biocompatible, and inexpensive. Another benefit is the solubilization of alginate gels in the human intestines by trapping calcium ions and releasing trapped cells. The sodium alginate and calcium chloride ratios used to make the beads range from 1 to 3% alginate with 0.05 to 1.5 M CaCl2 (M. J. Chen and Chen 2007; Rowley, Madlambayan, and Mooney 1999). The benefit of alginate is that it can easily form gel matrices around bacterial cells, it is safe for the body, it is inexpensive, mild process conditions (such as temperature) are required for its performance, it can be easily prepared and properly dissolve in the intestine and release entrapped cells. However, there are some drawbacks to using alginate beads. For example, alginate microcapsules are sensitive to acidic environments, which is incompatible with the beads' resistance in stomach conditions. Another disadvantage of alginate microparticles is that the microbeads produced are very porous, making it difficult to protect the cells from their surroundings (Chavarri, Maranon, and Carmen 2012).

ĸ-Carrageenan

ĸ-carrageenan is a natural polymer widely used in the food industry. The cells must be added to the polymer solution at a temperature of between 40 and 50 °C according to the technology using the compound. The gelation takes place when the mixture is cooled to room temperature, and the microparticles are then stabilized by adding potassium ions.

Chitosan

Chitosan is a glucosamine-based linear polysaccharide that can be extracted from fungi, insect cuticles, and crustacean membranes. It can polymerize by forming a cross-link when anions and polyanions are present. This ingredient has not demonstrated a strong ability to increase cell viability through encapsulation, and it is best used as a coat rather than a capsule. Probiotic bacteria can be delivered to the colon in a viable state by being enclosed in an alginate and chitosan coating, which offers protection under simulated GI conditions (Chávarri et al. 2010; Iravani, Korbekandi, and Mirmohammadi 2015).

Gelatin

Gelatin is a protein that is formed from the partial hydrolysis of collagen. It has a unique structure and versatile functional properties, and it forms a viscous solution in water that cools to form a gel. Because of its amphoteric nature, it can have synergistic effects with anionic polysaccharides such as gellan gum. At pH greater than 6, the two polymers mentioned are miscible because they both have net negative charges and repel one another. When the pH is reduced below the isoelectric point of gelatin, the net charge on the gelatin becomes positive, resulting in an interaction with the negatively charged gellan gum. Gelain-toluene diisocyanate mixture produces strong capsules that are resistant to cracking and breaking, especially at higher concentrations. This is due to the formation of cross-links between these polymers (Martín et al. 2015).

Starch

Starch is a polysaccharide, which is made up of D-glucose units linked together by glycosidic bonds, produced by green plants. It is made up of two constitutionally identical but structurally distinct molecules: amylose and amylopectin. Amylose refers to the linear and helical chains of glucose polymer, whereas amylopectin refers to the highly branched chains. The content of each fraction varies depending on the origin of the starch, but in general, it contains 20-30% amylose and 70-80% amylopectin (Chavarri, Maranon, and Carmen 2012). The starch granule is an ideal surface for probiotic cell adhesion, and resistant starch which can not be digested by pancreatic enzymes in the small intestine, can reach the colon and be fermented (Kritchevsky 1995 RS.pdf n.d.). As a result, the resistant starch has a good enteric delivery characteristic, resulting in a better release of bacterial cells in the large intestine. Furthermore, resistant starch can be used by probiotic bacteria in the large intestine due to its prebiotic functionality. It has been shown to be protective against colorectal cancer (Cassidy, Bingham, and Cummings 1994; Chavarri, Maranon, and Carmen 2012).

Xanthan

Xanthan is a heteropolysaccharide with a primary structure made up of repeated pentasaccharide units made up of two glucose units, two mannose units, and one glucuronic acid unit. The polysaccharide is made by fermenting the bacterium Xanthomonas campestris and then filtering or centrifuging it. This polymer is soluble in cold water and quickly hydrates. Even though xanthan is primarily non-gelling, a mixture of xanthan and gellan gum has been used to encapsulate probiotic cells (M. J. Chen and Chen 2007; Sultana et al. 2000).

Conclusion

In general, identifying and selecting probiotics is a safe choice for ingesting drugs and other therapies to control health imbalances in humans and animals. Probiotics are protected by encapsulation during food processing and storage as well as during gastrointestinal conditions, making them one of the most efficient ways to maintain viability and stability. New materials are being tested, and new technologies, like electrospinning, are being developed, in addition to the polysaccharides that have traditionally been used as a matrix in encapsulation. To produce homogenous particles for industrial uses, new methods or apparatus are needed. More research is also needed to identify appropriate carrier matrices and bacterial strains. Microencapsulation incurs additional expenditures that must be anticipated in order to be minimized. Simpler methods, less bacterial waste, and greater product health effects can all result in cost reductions. The research, on the other hand, intends to promote the usage of encapsulated probiotics in various food matrices. Furthermore, few in-vivo studies have been conducted to investigate the beneficial effects of probiotics that have been encapsulated. Despite the excellent results, these research were only conducted on animals. Large-scale clinical trials involving a large number of patients will be required to obtain solid proof of the preventative and therapeutic efficacy of encapsulated probiotics in medical practice. These microorganisms' ability to colonize their niche, as well as information on the optimal formulations in terms of bacterial viability and number, will be required. The administration schedule must be standardized in order to get uniform and comparable results.

References

- Adhikari, K., A. Mustapha, I. U. Grün, and L. Fernando. “Viability of Microencapsulated Bifidobacteria in Set Yogurt during Refrigerated Storage.” Journal of Dairy Science 2000, 83, 1946–1951. https://doi.org/10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(00)75070-3.

- Aghebati-Maleki, Leili, Paniz Hasannezhad, Amin Abbasi, and Nader Khani. “Antibacterial, Antiviral, Antioxidant, and Anticancer Activities of Postbiotics: A Review of Mechanisms and Therapeutic Perspectives.” Biointerface Research in Applied Chemistry 2022, 12, 2629–2645. https://doi.org/10.33263/BRIAC122.26292645.

- Aljumaah, Mashael R. et al. “Organic Acid Blend Supplementation Increases Butyrate and Acetate Production in Salmonella Enterica Serovar Typhimurium Challenged Broilers.” PLoS ONE 2020, 15, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0232831.

- Arena, Mattia Pia et al. “Use of Lactobacillus Plantarum Strains as a Bio-Control Strategy against Food-Borne Pathogenic Microorganisms.” Frontiers in Microbiology 2016, 7, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2016.00464.

- Banerjee, M., P. Vats, A. S. Kushwah, and N. Srivastava. “Interaction of Antioxidant Gene Variants and Susceptibility to Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus.” British Journal of Biomedical Science 2019, 76, 166–171. https://doi.org/10.1080/09674845.2019.1595869.

- Bidra, Avinash S. et al. “Comparison of In Vitro Inactivation of SARS CoV-2 with Hydrogen Peroxide and Povidone-Iodine Oral Antiseptic Rinses.” Journal of Prosthodontics 2020, 29, 599–603. https://doi.org/10.1111/jopr.13220.

- Blazheva, D. et al. “Antioxidant Potential of Probiotics and Postbiotics: A Biotechnological Approach to Improving Their Stability.” Russian Journal of Genetics 2022, 58, 1036–1050. https://doi.org/10.1134/S1022795422090058.

- Cani, P. D. et al. “Changes in Gut Microbiota Control Inflammation in Obese Mice through a Mechanism Involving GLP-2-Driven Improvement of Gut Permeability.” Gut 2009, 58, 1091–1103. https://doi.org/10.1136/gut.2008.165886.

- Cassidy, A., S. A. Bingham, and J. H. Cummings. “Starch Intake and Colorectal Cancer Risk: An International Comparison.” British Journal of Cancer 1994, 69, 937–942. https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.1994.181.

- Chávarri, María et al. “Microencapsulation of a Probiotic and Prebiotic in Alginate-Chitosan Capsules Improves Survival in Simulated Gastro-Intestinal Conditions.” International Journal of Food Microbiology 2010, 142(1–2): 185–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2010.06.022.

- Chavarri, Maria, Izaskun Maranon, and Maria Carmen. 2012. “Encapsulation Technology to Protect Probiotic Bacteria.” Probiotics (October). https://doi.org/10.5772/50046.

- Cheifetz, Adam S., Robert Gianotti, Raphael Luber, and Peter R. Gibson. “Complementary and Alternative Medicines Used by Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Diseases.” Gastroenterology 2017, 152, 415-429.e15. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2016.10.004.

- Chen, Baishen et al. 2019. “Glutathione Peroxidase 1 Promotes NSCLC Resistance to Cisplatin via ROS-Induced Activation of PI3K/AKT Pathway.” BioMed Research International 2019. https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/7640547.

- Chen, Ming Ju, and Kun Nan Chen. “Applications of Probiotic Encapsulation in Dairy Products.” Encapsulation and Controlled Release Technologies in Food Systems: 2007, 83–112. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470277881.ch4.

- Chuah, Li-oon et al. 2019. “S12906-019-2528-2.Pdf.” 2, 1–12.

- Churchward, Colin P., Raid G. Alany, and Lori A.S. Snyder. “Alternative Antimicrobials: The Properties of Fatty Acids and Monoglycerides.” Critical Reviews in Microbiology 2018, 44, 561–570. https://doi.org/10.1080/1040841X.2018.1467875.

- Deeths, Matthew J. et al. “Phenotypic Analysis of T-Cells in Extensive Alopecia Areata Scalp Suggests Partial Tolerance.” Journal of Investigative Dermatology 2006, 126, 366–373. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.jid.5700054.

- Deng, Lingli, and Hui Zhang. “Recent Advances in Probiotics Encapsulation by Electrospinning.” ES Food & Agroforestry: 2020, 3–12. https://doi.org/10.30919/esfaf1120.

- El-Deeb, Nehal M., Abdelrahman M. Yassin, Lamiaa A. Al-Madboly, and Amr El-Hawiet. “A Novel Purified Lactobacillus Acidophilus 20079 Exopolysaccharide, LA-EPS-20079, Molecularly Regulates Both Apoptotic and NF-ΚB Inflammatory Pathways in Human Colon Cancer.” Microbial Cell Factories 2018, 17, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12934-018-0877-z.

- Feng, Kun et al. “Improved Viability and Thermal Stability of the Probiotics Encapsulated in a Novel Electrospun Fiber Mat.” Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 2018, 66, 10890–10897. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jafc.8b02644.

- Finegold, Sydney M. et al. “Pyrosequencing Study of Fecal Microflora of Autistic and Control Children.” Anaerobe 2010, 16, 444–453. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anaerobe.2010.06.008.

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations., and World Health Organization. 2006. Probiotics in Food : Health and Nutritional Properties and Guidelines for Evaluation. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

- Formhals, Anton. 1934. “Apparatus for Producing Artificial Filaments from Material Such as Cellulose Acetate.” Us1975504.

- Gálvez, Antonio, Hikmate Abriouel, Rosario Lucas López, and Nabil Ben Omar. “Bacteriocin-Based Strategies for Food Biopreservation.” International Journal of Food Microbiology 2007, 120, 51–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2007.06.001.

- Goldin, Barry R. “Health Benefits of Probiotics.” British Journal of Nutrition 1998, 80 (SUPPL. 2). https://doi.org/10.1017/s0007114500006036.

- Gómez-Llorente, Carolina, Sergio Muñoz, and Angel Gil. “Role of Toll-like Receptors in the Development of Immunotolerance Mediated by Probiotics.” Proceedings of the Nutrition Society 2010, 69, 381–389. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0029665110001527.

- Griffiths, Elizabeth A. et al. “In Vivo Effects of Bifidobacteria and Lactoferrin on Gut Endotoxin Concentration and Mucosal Immunity in Balb/c Mice.” Digestive Diseases and Sciences 2004, 49, 579–589. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:DDAS.0000026302.92898.ae.

- Guo, Yuxing et al. “Antioxidant and Immunomodulatory Activity of Selenium Exopolysaccharide Produced by Lactococcus Lactis Subsp. Lactis.” Food Chemistry 2013, 138, 84–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2012.10.029.

- Gurung, Arun Bahadur et al. “Unravelling Lead Antiviral Phytochemicals for the Inhibition of SARS-CoV-2 Mpro Enzyme through in Silico Approach.” Life Sciences 2020, 255, 117831. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lfs.2020.117831.

- Haffner, Fernanda B. 2017. “Encapsulation of Lactobacillus Rhamnosus GG into Hybrid Alginate-Silica Microparticles.”.

- Haghshenas, Babak et al. “Different Effects of Two Newly-Isolated Probiotic Lactobacillus Plantarum 15HN and Lactococcus Lactis Subsp. Lactis 44Lac Strains from Traditional Dairy Products on Cancer Cell Lines.” Anaerobe 2014, 30(August): 51–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anaerobe.2014.08.009.

- He, Zhimei et al. “A Catalase-Like Metal-Organic Framework Nanohybrid for O2-Evolving Synergistic Chemoradiotherapy.” Angewandte Chemie - International Edition 2019, 58, 8752–8756. https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.201902612.

- Iravani, Siavash, Hassan Korbekandi, and Seyed Vahid Mirmohammadi. “Technology and Potential Applications of Probiotic Encapsulation in Fermented Milk Products.” Journal of Food Science and Technology 2015, 52, 4679–4696. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13197-014-1516-2.

- Kahouli, Imen, Catherine Tomaro-Duchesneau, and Satya Prakash. “Probiotics in Colorectal Cancer (CRC) with Emphasis on Mechanisms of Action and Current Perspectives.” Journal of Medical Microbiology 2013, 62(PART8): 1107–23. https://doi.org/10.1099/jmm.0.048975-0.

- Kailasapathy, Kasipathy. “Encapsulation Technologies for Functional Foods and Nutraceutical Product Development.” CAB Reviews: Perspectives in Agriculture, Veterinary Science, Nutrition and Natural Resources 2009, 4(033). https://doi.org/10.1079/PAVSNNR20094033.

- Kalliomäki, Marko, Maria Carmen Collado, Seppo Salminen, and Erika Isolauri. “Early Differences in Fecal Microbiota Composition in Children May Predict Overweight.” American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2008, 87, 534–538. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/87.3.534.

- Kawalec, Pawel. “Indirect Costs of Inflammatory Bowel Diseases: Crohn’s Disease and Ulcerative Colitis. A Systematic Review.” Archives of Medical Science 2016, 12, 295–302. https://doi.org/10.5114/aoms.2016.59254.

- Kechagia, Maria et al. “Health Benefits of Probiotics: A Review.” ISRN Nutrition 2013, 2013, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.5402/2013/481651.

- King, Alan H. “Encapsulation of Food Ingredients.” : 1995, 26–39. https://doi.org/10.1021/bk-1995-0590.ch003.

- Kleniewska, Paulina, and Rafał Pawliczak. “The Influence of Apocynin, Lipoic Acid and Probiotics on Antioxidant Enzyme Levels in the Pulmonary Tissues of Obese Asthmatic Mice.” Life Sciences 2019, 234(April). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lfs.2019.116780.

- Korotkyi, O. et al. “Effect of Probiotic Composition on Oxidative/Antioxidant Balance in Blood of Rats under Experimental Osteoarthritis.” Ukrainian Biochemical Journal 2019, 91, 49–58. https://doi.org/10.15407/ubj91.06.049.

- Krasaekoopt, Wunwisa, Bhesh Bhandari, and Hilton Deeth. “Evaluation of Encapsulation Techniques of Probiotics for Yoghurt.” International Dairy Journal 2003, 13, 3–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0958-6946(02)00155-3.

- Kratz, Mario, Paul Cullen, and Ursel Wahrburg. “The Impact of Dietary Mono- and Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids on Risk Factors for Atherosclerosis in Humans.” European Journal of Lipid Science and Technology 2002, 104, 300–311. https://doi.org/10.1002/1438-9312(200205)104, 5<300, :AID-EJLT300>3.0.CO;2-2.

- “Kritchevsky 1995 RS.Pdf.”.

- Larsen, Nadja et al. “Gut Microbiota in Human Adults with Type 2 Diabetes Differs from Non-Diabetic Adults.” PLoS ONE 2010, 5(2). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0009085.

- Le, Bao, and Seung Hwan Yang. “Efficacy of Lactobacillus Plantarum in Prevention of Inflammatory Bowel Disease.” Toxicology Reports 2018, 5(March): 314–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.toxrep.2018.02.007.

- Lebeer, Sarah, Jos Vanderleyden, and Sigrid C.J. De Keersmaecker. “Host Interactions of Probiotic Bacterial Surface Molecules: Comparison with Commensals and Pathogens.” Nature Reviews Microbiology 2010, 8, 171–184. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrmicro2297.

- Lin, Xiangna et al. “Probiotic Characteristics of Lactobacillus Plantarum AR113 and Its Molecular Mechanism of Antioxidant.” Lwt 2020, 126, 109278. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lwt.2020.109278.

- Liong, Min Tze. “Roles of Probiotics and Prebiotics in Colon Cancer Prevention: Postulated Mechanisms and in-Vivo Evidence.” International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2008, 9, 854–863. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms9050854.

- Ljungh, Åsa, and Torkel Wadström. “Lactic Acid Bacteria as Probiotics Further Reading.” Current Issues Intestinal Microbiology 2001, 7, 73–90.

- Mali, Jaishree K. et al. “Novel Fatty Acid-Thiadiazole Derivatives as Potential Antimycobacterial Agents.” Chemical Biology and Drug Design 2020, 95, 174–181. https://doi.org/10.1111/cbdd.13634.

- Mani-López, E., H. S. García, and A. López-Malo. “Organic Acids as Antimicrobials to Control Salmonella in Meat and Poultry Products.” Food Research International 2012, 45, 713–721. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodres.2011.04.043.

- Martín, María José, Federico Lara-Villoslada, María Adolfina Ruiz, and María Encarnación Morales. “Microencapsulation of Bacteria: A Review of Different Technologies and Their Impact on the Probiotic Effects.” Innovative Food Science and Emerging Technologies 2015, 27, 15–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ifset.2014.09.010.

- Mortazavian, Amir, Seyed Hadi Razavi, Mohammad Reza Ehsani, and Sara Sohrabvandi. “Principles and Methods of Microencapsulation of Probiotic Microorganisms.” IRANIAN JOURNAL of BIOTECHNOLOGY 2007, 5, 1–18.

- Ng, Siew C. et al. “Immunosuppressive Effects via Human Intestinal Dendritic Cells of Probiotic Bacteria and Steroids in the Treatment of Acute Ulcerative Colitis.” Inflammatory Bowel Diseases 2010, 16, 1286–1298. https://doi.org/10.1002/ibd.21222.

- O’Connor, Paula M. et al. “Antimicrobials for Food and Feed; a Bacteriocin Perspective.” Current Opinion in Biotechnology 2020, 61, 160–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copbio.2019.12.023.

- O’Riordan, K., D. Andrews, K. Buckle, and P. Conway. “Evaluation of Microencapsulation of a Bifidobacterium Strain with Starch as an Approach to Prolonging Viability during Storage.” Journal of Applied Microbiology 2001, 91, 1059–1066. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2672.2001.01472.x.

- Ooi, Lay Gaik, and Min Tze Liong. “Cholesterol-Lowering Effects of Probiotics and Prebiotics: A Review of in Vivo and in Vitro Findings.” International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2010, 11, 2499–2522. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms11062499.

- Petrof, Elaine O. et al. “Probiotics Inhibit Nuclear Factor-ΚB and Induce Heat Shock Proteins in Colonic Epithelial Cells through Proteasome Inhibition.” Gastroenterology 2004, 127, 1474–1487. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2004.09.001.

- Qin, Junjie et al. “A Human Gut Microbial Gene Catalogue Established by Metagenomic Sequencing.” Nature 2010, 464, 59–65. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature08821.

- Reid, Gregor et al. “New Scientific Paradigms for Probiotics and Prebiotics.” Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology 2003, 37, 105–118. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004836-200308000-00004.

- Reque, Priscilla Magro, and Adriano Brandelli. “Encapsulation of Probiotics and Nutraceuticals: Applications in Functional Food Industry.” Trends in Food Science and Technology 2021, 114(December 2020): 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tifs.2021.05.022.

- Rowley, Jon A., Gerard Madlambayan, and David J. Mooney. “Alginate Hydrogels as Synthetic Extracellular Matrix Materials.” Biomaterials 1999, 20, 45–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0142-9612(98)00107-0.

- Saarela, Maria et al. “Probiotic Bacteria: Safety, Functional and Technological Properties.” Journal of Biotechnology 2000, 84, 197–215. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0168-1656(00)00375-8.

- Salalha, W., J. Kuhn, Y. Dror, and E. Zussman. “Encapsulation of Bacteria and Viruses in Electrospun Nanofibres.” Nanotechnology 2006, 17, 4675–4681. https://doi.org/10.1088/0957-4484/17/18/025.

- Saqib, Muhammad et al. “Lucigenin-Tris(2-Carboxyethyl)Phosphine Chemiluminescence for Selective and Sensitive Detection of TCEP, Superoxide Dismutase, Mercury(II), and Dopamine.” Analytical Chemistry 2019, 91, 3070–3077. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.analchem.8b05486.

- Sarkar, S. “Approaches for Enhancing the Viability of Probiotics: A Review.” British Food Journal 2010, 112, 329–349. https://doi.org/10.1108/00070701011034376.

- Shah, Nagendra P., Warnakulasuriya E.V. Lankaputhra, Margaret L. Britz, and William S.A. Kyle. “Survival of Lactobacillus Acidophilus and Bifidobacterium Bifidum in Commercial Yoghurt during Refrigerated Storage.” International Dairy Journal 1995, 5, 515–521. https://doi.org/10.1016/0958-6946(95)00028-2.

- Sultana, Khalida et al. “Encapsulation of Probiotic Bacteria with Alginate-Starch and Evaluation of Survival in Simulated Gastrointestinal Conditions and in Yoghurt.” International Journal of Food Microbiology 2000, 62(1–2): 47–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0168-1605(00)00380-9.

- Sungur, Tolga, Belma Aslim, Cagtay Karaaslan, and Busra Aktas. “Impact of Exopolysaccharides (EPSs) of Lactobacillus Gasseri Strains Isolated from Human Vagina on Cervical Tumor Cells (HeLa).” Anaerobe 2017, 47, 137–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anaerobe.2017.05.013.

- Tan-Lim, Carol Stephanie C., and Natasha Ann R. Esteban-Ipac. “Probiotics as Treatment for Food Allergies among Pediatric Patients: A Meta-Analysis.” World Allergy Organization Journal 2018, 11, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40413-018-0204-5.

- Tiptiri-Kourpeti, Angeliki et al. “Lactobacillus Casei Exerts Anti-Proliferative Effects Accompanied by Apoptotic Cell Death and up-Regulation of TRAIL in Colon Carcinoma Cells.” PLoS ONE 2016, 11, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0147960.

- Tukenmez, Ummugulsum, Busra Aktas, Belma Aslim, and Serkan Yavuz. “The Relationship between the Structural Characteristics of Lactobacilli-EPS and Its Ability to Induce Apoptosis in Colon Cancer Cells in Vitro.” Scientific Reports 2019, 9, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-44753-8.

- Turnbaugh, Peter J. et al. “A Core Gut Microbiome in Obese and Lean Twins.” Nature 2009, 457, 480–484. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature07540.

- Ungati, Harinarayana, Vijayakumar Govindaraj, Megha Narayanan, and Govindasamy Mugesh. “Probing the Formation of a Seleninic Acid in Living Cells by the Fluorescence Switching of a Glutathione Peroxidase Mimetic.” Angewandte Chemie - International Edition 2019, 58, 8156–8160. https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.201903958.

- de Vos, Paul, Marijke M. Faas, Milica Spasojevic, and Jan Sikkema. “Encapsulation for Preservation of Functionality and Targeted Delivery of Bioactive Food Components.” International Dairy Journal 2010, 20, 292–302. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.idairyj.2009.11.008.

- Wang, Jun et al. “A Metagenome-Wide Association Study of Gut Microbiota in Type 2 Diabetes.” Nature 2012, 490, 55–60. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature11450.

- Wang, Zhongtang et al. “The Role of Bifidobacteria in Gut Barrier Function after Thermal Injury in Rats.” Journal of Trauma - Injury, Infection and Critical Care 2006, 61, 650–657. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.ta.0000196574.70614.27.

- Yang, Gang et al. “Probiotic (Bacillus Cereus) Enhanced Growth of Pengze Crucian Carp Concurrent with Modulating the Antioxidant Defense Response and Exerting Beneficial Impacts on Inflammatory Response via Nrf2 Activation.” Aquaculture 2020, 529, 735691. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aquaculture.2020.735691.

- Zakostelska, Zuzana et al. “Lysate of Probiotic Lactobacillus Casei DN-114 001 Ameliorates Colitis by Strengthening the Gut Barrier Function and Changing the Gut Microenvironment.” PLoS ONE 2011, 6(11). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0027961.

- Zukiewicz-Sobczak, Wioletta, Paula Wróblewska, Piotr Adamczuk, and Wojciech Silny. “Probiotic Lactic Acid Bacteria and Their Potential in the Prevention and Treatment of Allergic Diseases.” Central European Journal of Immunology 2014, 39, 113–117. https://doi.org/10.5114/ceji.2014.42134.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).