Submitted:

20 July 2025

Posted:

21 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Case Presentation

- Questions asked to the patient:

- Have you ever received any treatment for your temporomandibular joint problems? NO

- Do you ever wake up with tooth or jaw discomfort? YES

- Does she ever realize that she clenches her teeth hard during the day? YES

- Has anyone ever told you that you rattle your teeth during sleep? NO

- Does she experience pain when she eats? SOMETIMES

- Does she experience pain or discomfort around her eyes, ears, or other parts of her body? AROUND MATICATORY MUSCLES

- Does she have hearing problems? NO

- Does She have headaches or a sense of "tightness"? YES

- Does She have occasional headaches? YES

- Does She or she suffer from migraines? NO

- Does she feel the whole mouth burning? NO

- Does she feel burning parts of the mouth (tongue, gums, cheeks, palate)? NO

- Does she have frequent neck muscle discomfort or neck pain? YES

- Do you feel the pain move from one place to another in your face, neck, shoulders, or back? YES

- Do the jaw muscles tire easily? YES

- Do you have difficulty opening your mouth much? NO

- Does she suffer or has he suffered from arthritis? NO

- Do you have any relatives who suffer from arthritis or gout? NO

- Have you ever received a bump in the neck or jaw area? NO

- Have you ever experienced pain in the jaw joint? NO

- Have you ever had ear problems such as ringing or lowered hearing? NO

- Have you ever heard creaking-type noises coming from the jaw joint? NO

- Do you feel that you cannot open your mouth as much as you would like? NO

- Do you currently experience pain coming from the jaw joint or muscles? YES, IN MUSCLES

- Does the pain or discomfort coming from the jaw joint interfere with your work or other activities? SOMETIMES

- Are there times when you feel that the problem or pain is less or disappears altogether? SOMETIMES

- Do you feel depressed? NO

- Have you ever been seen by a psychologist? NO

- Do you have problems with insomnia? NO

- Are you currently in a particular stressful situation (work, family, study, etc.)? NO

- Does he/she drink more than one alcoholic beverage per day? NO

- Does he smoke cigarettes, pipe or cigar? NO

- Does he usually bite his nails, lips or tongue? NO

- Do you think your pain may be related to stress? MAYBE

- In your opinion, during the day, your teeth are in contact (even light contact) for: 2 min, 2 h, 10 h, 15 h, 24 h. THE PATIENT SELECT 10 H.

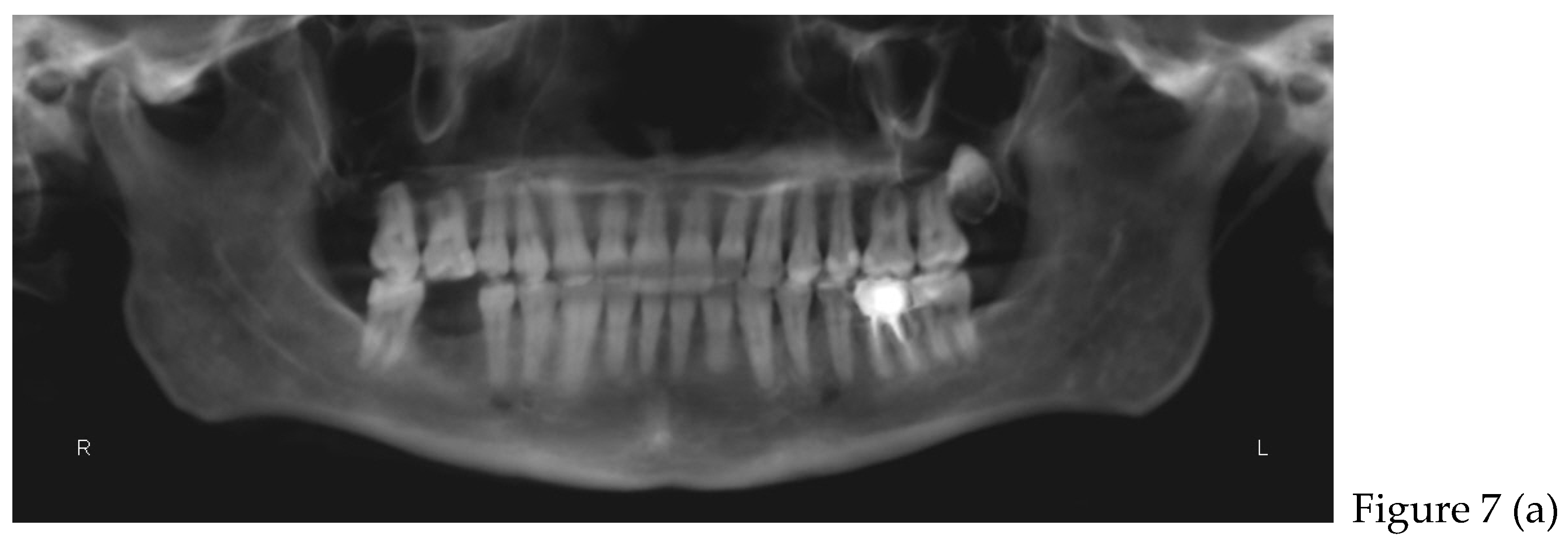

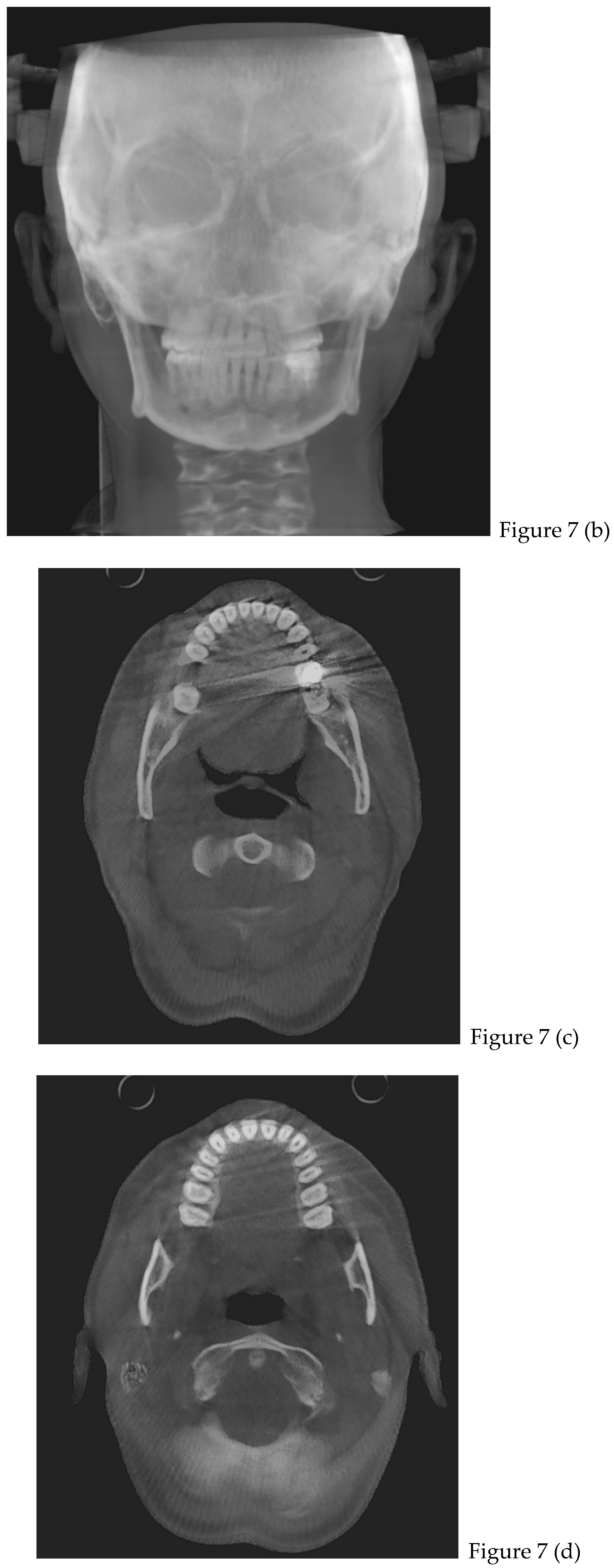

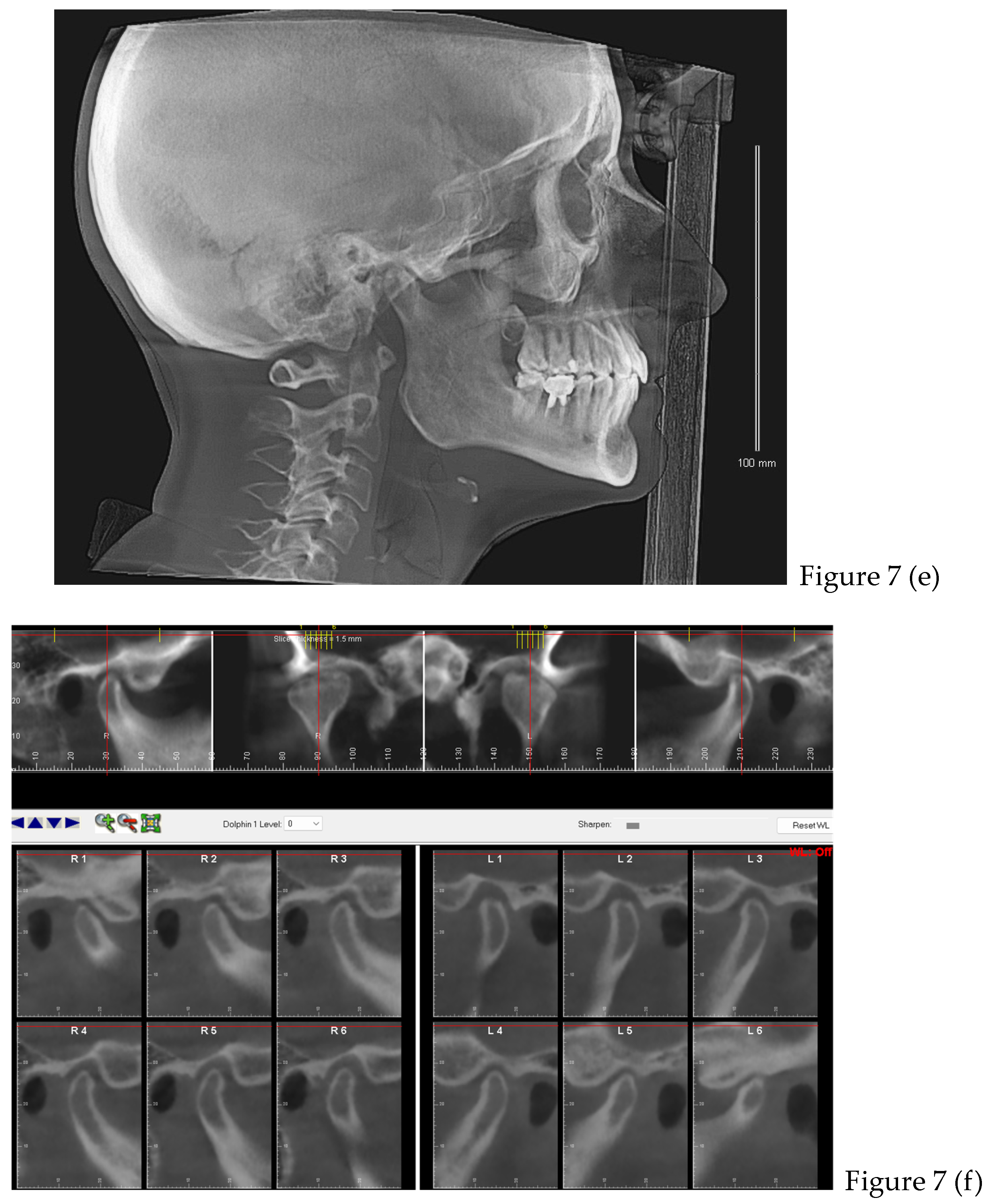

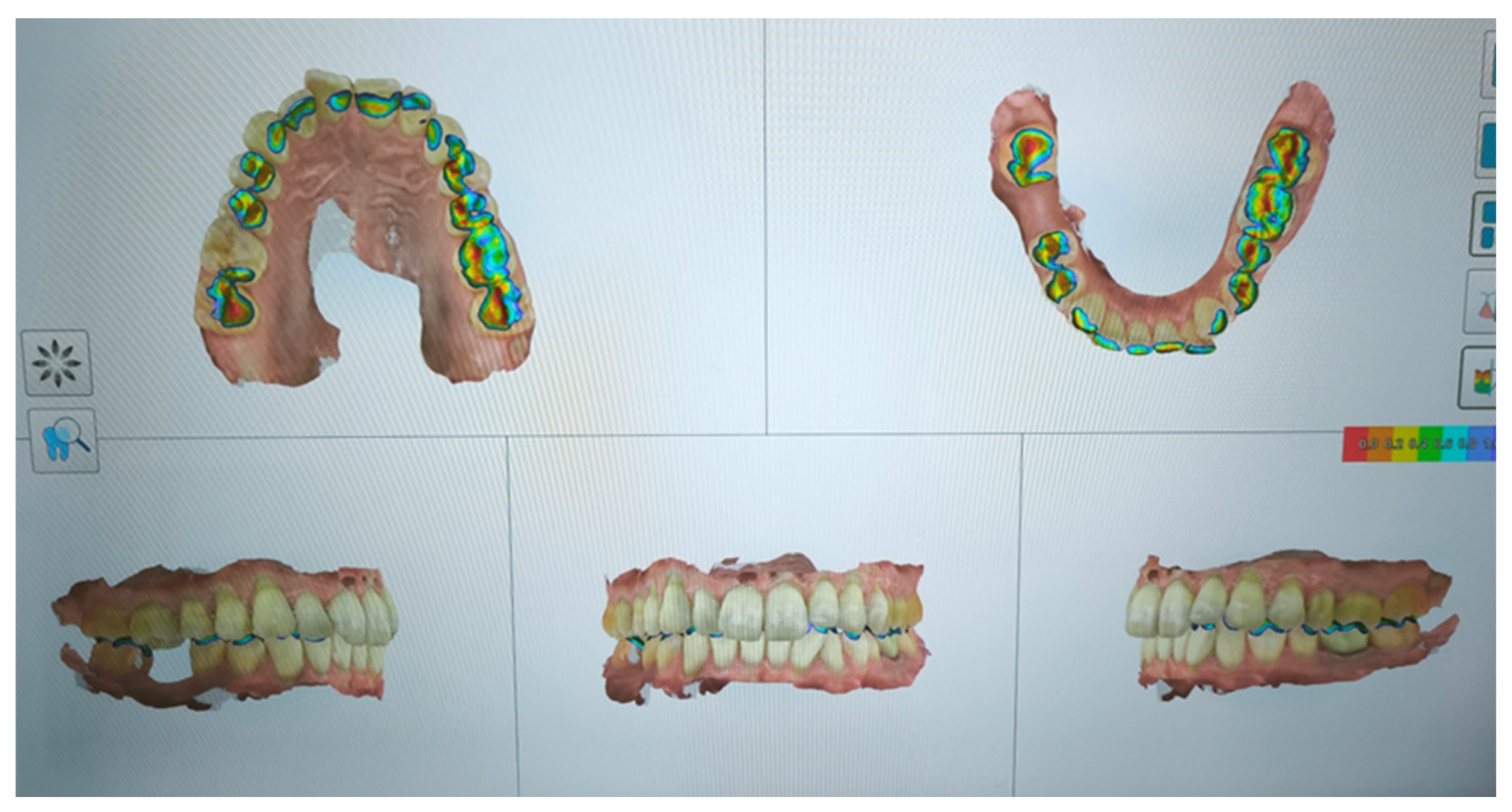

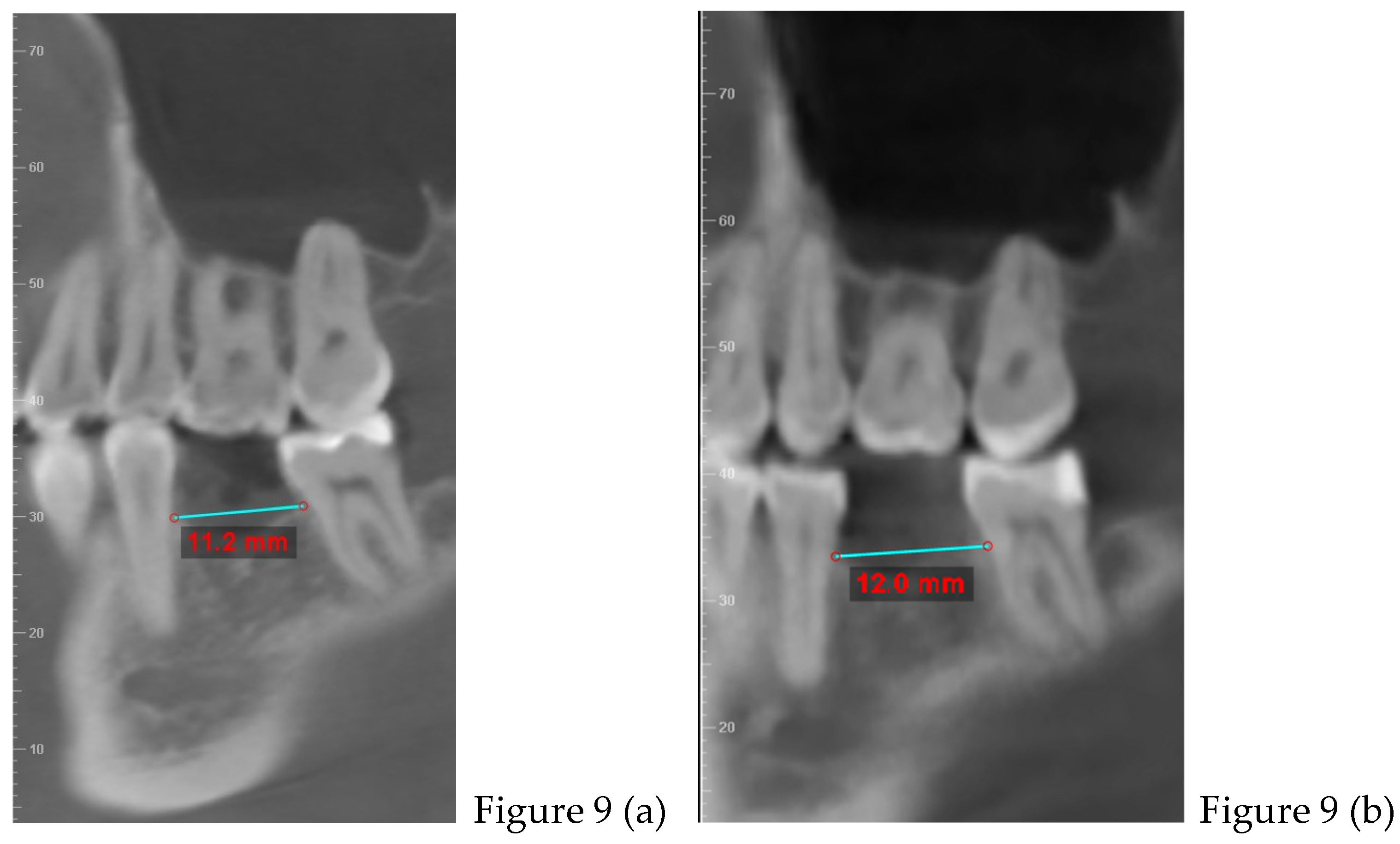

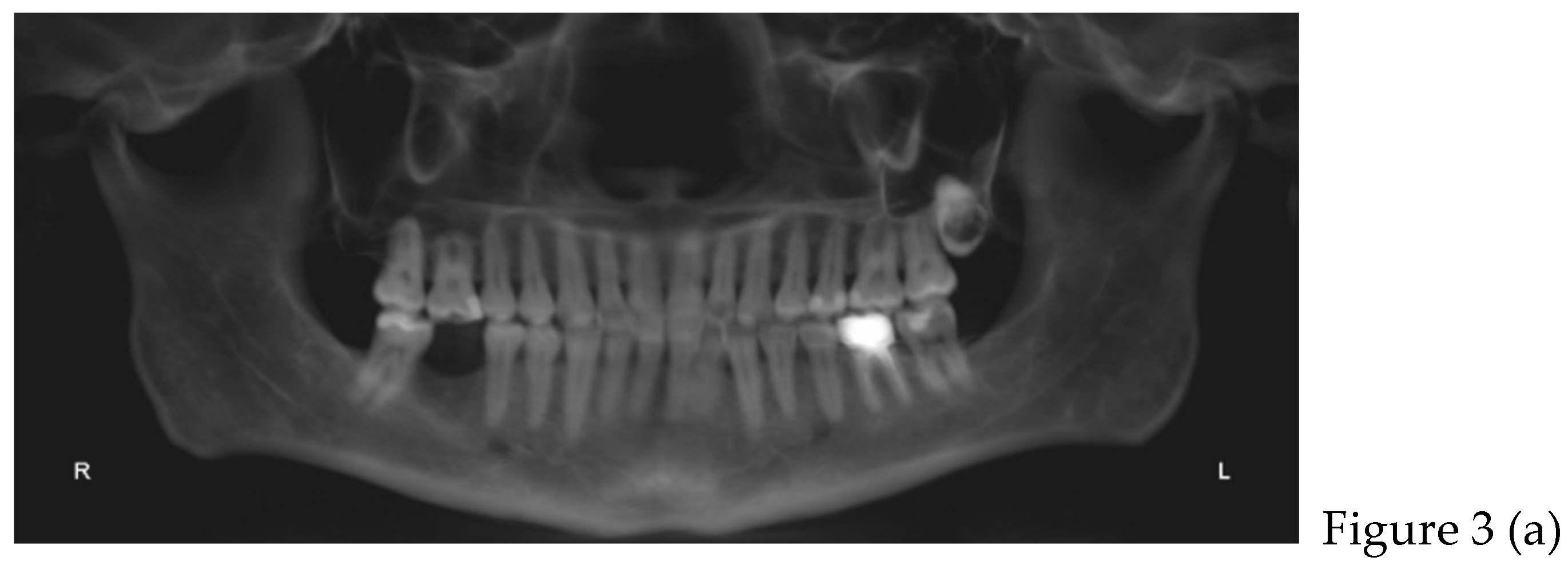

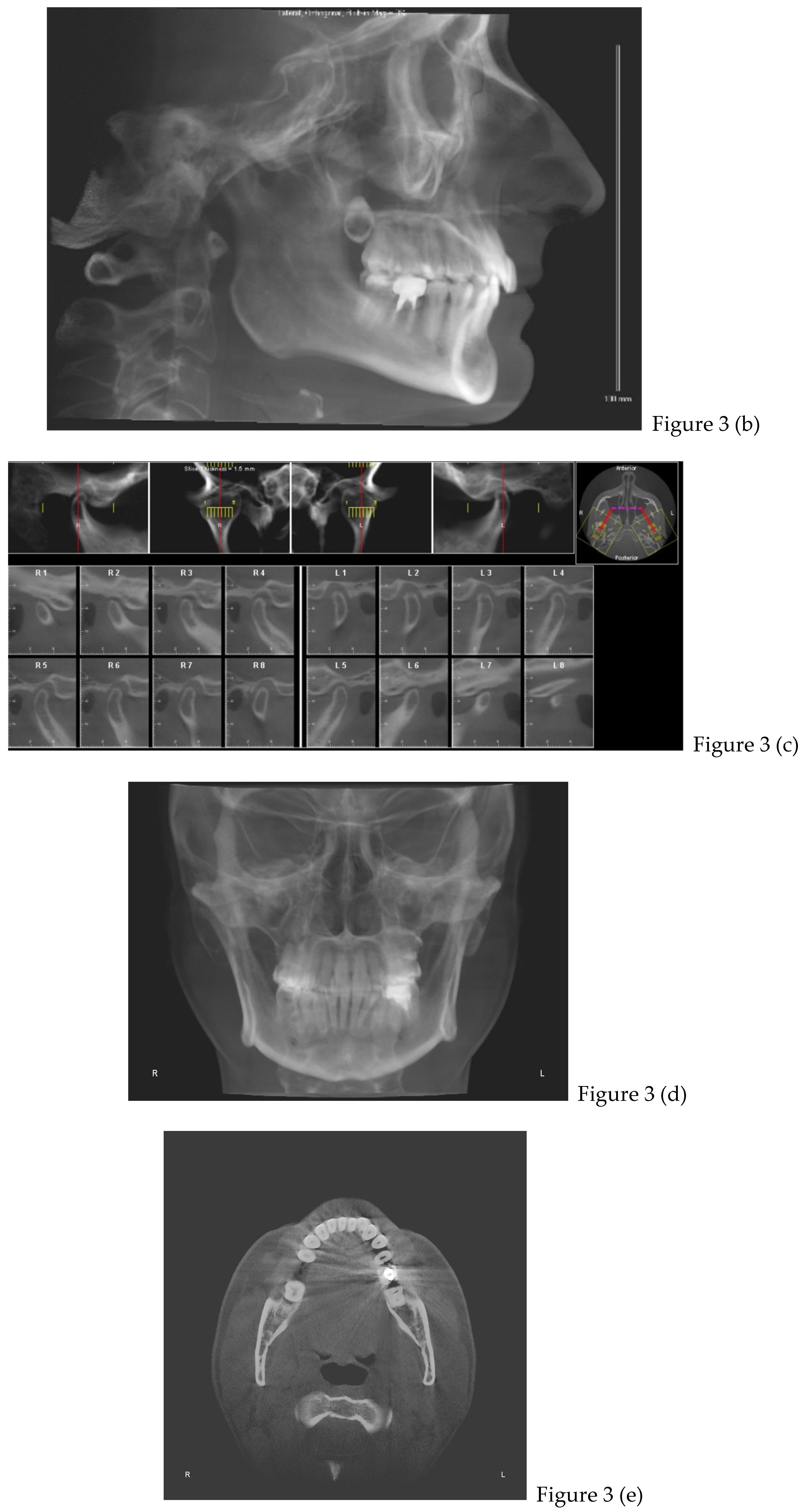

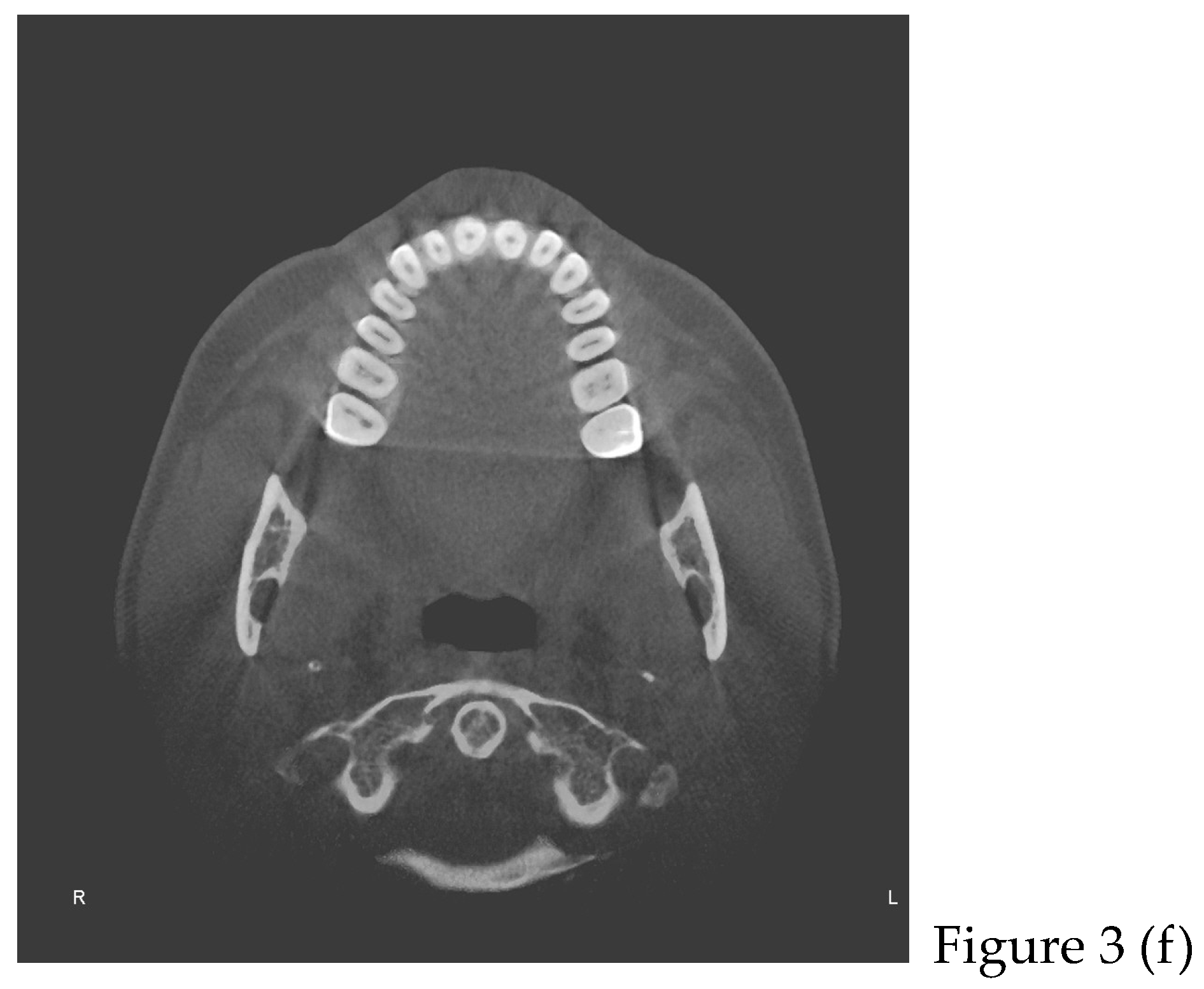

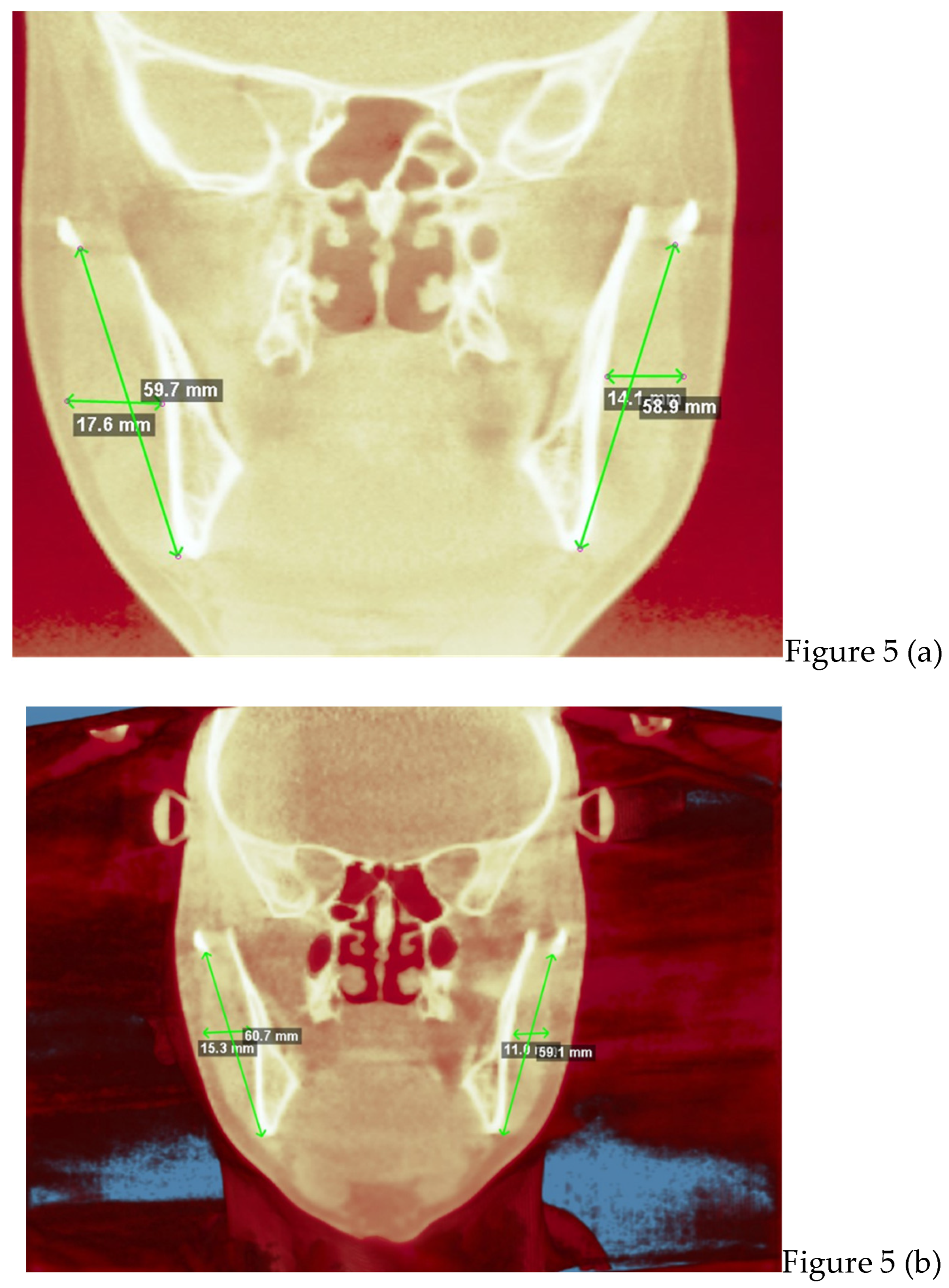

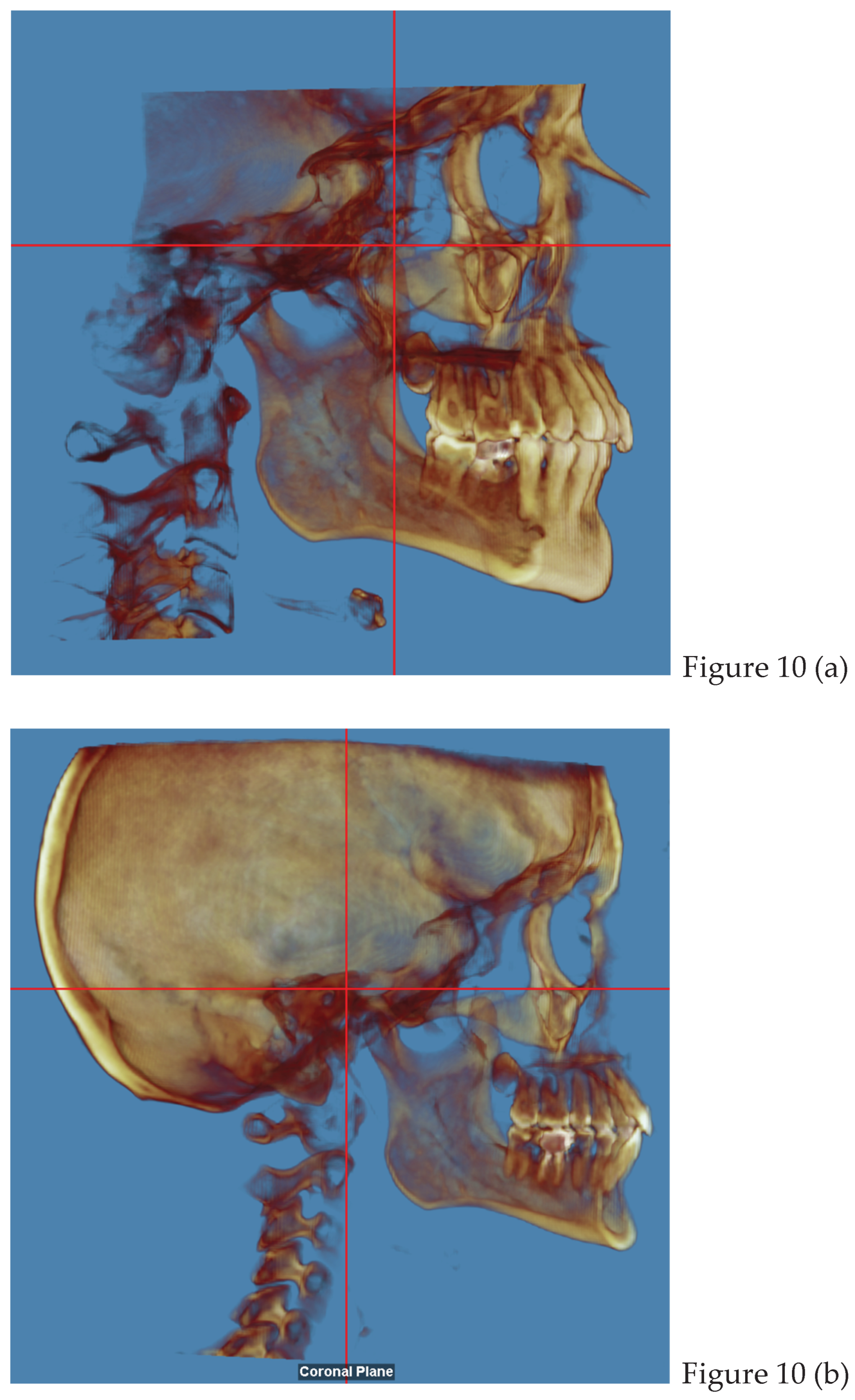

2.2. Cone Beam CT Analysis

2.3. Diagnosis and Treatment Planning

2.3.1. Gnathological Therapy

2.3.2. Orthodontic Therapy

3. Discussion

3. Limitations

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| TMJ | temporomandibular joint |

| AEI | articular eminence inclination |

| VAS | visual analogic scale |

| NSAIDs | Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs |

| TT | temporalis tendon |

| PES | external pterygoid muscle upper head |

| PEI | external pterygoid muscle lower head |

| PIS | internal pterygoid muscle upper head |

| PII | internal pterygoid muscle lower head |

| MMP | deep masseter muscle |

| MMS | superficial masseter muscle |

| CBCT | Cone Beam Computer Tomography |

| DICOM | Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine |

| NHP | natural head position |

References

- Wieckiewicz M, Boening K, Wiland P, Shiau YY, Paradowska-Stolarz A. Reported concepts for the treatment modalities and pain management of temporomandibular disorders. J Headache Pain. 2015;16:106.Epub 2015 Dec 7. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Warzocha J, Gadomska-Krasny J, Mrowiec J. Etiologic Factors of Temporomandibular Disorders: A Systematic Review of Literature Containing Diagnostic Criteria for Temporomandibular Disorders (DC/TMD) and Research Diagnostic Criteria for Temporomandibular Disorders (RDC/TMD) from 2018 to 2022. Healthcare (Basel). 2024 Feb 29;12(5):575. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Rawat P, Saxena D, Srivastava PA, Sharma A, Swarnakar A, Sharma A. Prevalence and severity of temporomandibular joint disorder in partially versus completely edentulous patients: A systematic review. J Indian Prosthodont Soc. 2023 Jul-Sep;23(3):218-225. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lekaviciute R, Kriauciunas A. Relationship Between Occlusal Factors and Temporomandibular Disorders: A Systematic Literature Review. Cureus. 2024 Feb 13;16(2):e54130. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Tabatabaei S, Paknahad M, Poostforoosh M. The effect of tooth loss on the temporomandibular joint space: A CBCT study. Clin Exp Dent Res. 2024 Feb;10(1):e845. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Okeson, Jeffrey P. (2008). Management of temporomandibular disorders an occlusion, 6 Edition. St. Louis, Missouri: Elsevier Health Sciences.

- Chen Y, Luo M, Xie Y, Xing L, Han X, Tian Y. Periodontal ligament-associated protein-1 engages in teeth overeruption and periodontal fiber disorder following occlusal hypofunction. J Periodontal Res. 2023 Feb;58(1):131-142. Epub 2022 Nov 29. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ulay, G., Pekiner, F. N., & Orhan, K. (2020). Evaluation of the relationship between the degenerative changes and bone quality of mandibular condyle and articular eminence in temporomandibular disorders by cone beam computed tomography. CRANIO®, 41(3), 218–229. [CrossRef]

- Zheng H, Shi L, Lu H, Liu Z, Yu M, Wang Y, Wang H. Influence of edentulism on the structure and function of temporomandibular joint. Heliyon. 2023 Sep 23;9(10):e20307. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Rosado LPL, Barbosa IS, Junqueira RB, Martins APVB, Verner FS. Morphometric analysis of the mandibular fossa in dentate and edentulous patients: A cone beam computed tomography study. J Prosthet Dent. 2021 May;125(5):758.e1-758.e7. Epub 2021 Feb 17. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leal MDCF, Castro MML, Sosthenes MCK. Updating The General Practitioner on The Association Between Teeth Loss and Temporomandibular Disorders: A Systematic Review. Eur J Dent. 2023 May;17(2):296-309. Epub 2022 Dec 27. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Konishi M, Verdonschot RG, Kakimoto N. An investigation of tooth loss factors in elderly patients using panoramic radiographs. Oral Radiol. 2021 Jul;37(3):436-442. Epub 2020 Aug 18. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Craddock HL. Occlusal changes following posterior tooth loss in adults. Part 3. A study of clinical parameters associated with the presence of occlusal interferences following posterior tooth loss. J Prosthodont. 2008 Jan;17(1):25-30. Epub 2007 Oct 8. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang A, Cao J, Zhang H, Zhang B, Yang G, Hu W, Chung KH. Three-dimensional position changes of unopposed molars before implant rehabilitation: a short-term retrospective cohort analysis. BMC Oral Health. 2022 Dec 3;22(1):562. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Aldayel AM, AlGahnem ZJ, Alrashidi IS, Nunu DY, Alzahrani AM, Alburaidi WS, Alanazi F, Alamari AS, Alotaibi RM. Orthodontics and Temporomandibular Disorders: An Overview. Cureus. 2023 Oct 15;15(10):e47049. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Thong ISK, Jensen MP, Miró J, Tan G. The validity of pain intensity measures: what do the NRS, VAS, VRS, and FPS-R measure? Scand J Pain. 2018 Jan 26;18(1):99-107. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez CAF, Laverde COD, Rodríguez SEN, Gallego GAC, Aristizábal JF, Salazar OIC. Methodology for the correction of a CBCT volume from the skull to the natural head position. MethodsX. 2024 Nov 27;13:103073. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- McKinney R, Olmo H, McGovern B. Benign Chronic White Lesions of the Oral Mucosa. 2024 Jan 11. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan–. [PubMed]

- Wadhokar OC, Patil DS. Current Trends in the Management of Temporomandibular Joint Dysfunction: A Review. Cureus. 2022 Sep 19;14(9):e29314. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Okeson JP, de Leeuw R. Differential diagnosis of temporomandibular disorders and other orofacial pain disorders. Dent Clin North Am. 2011; 55(1): 105-120.

- Voß LC, Basedau H, Svensson P, May A. Bruxism, temporomandibular disorders, and headache: a narrative review of correlations and causalities. Pain. 2024 Nov 1;165(11):2409-2418. Epub 2024 Jun 18. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minakuchi H, Fujisawa M, Abe Y, Iida T, Oki K, Okura K, Tanabe N, Nishiyama A. Managements of sleep bruxism in adult: A systematic review. Jpn Dent Sci Rev. 2022 Nov;58:124-136. Epub 2022 Mar 25. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Garstka AA, Kozowska L, Kijak K, Brzózka M, Gronwald H, Skomro P, Lietz-Kijak D. Accurate Diagnosis and Treatment of Painful Temporomandibular Disorders: A Literature Review Supplemented by Own Clinical Experience. Pain Res Manag. 2023 Jan 31;2023:1002235. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Åström M, Thet Lwin ZM, Teni FS, Burström K, Berg J. Use of the visual analogue scale for health state valuation: a scoping review. Qual Life Res. 2023 Oct;32(10):2719-2729. Epub 2023 Apr 7. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Mitro V, Caso AR, Sacchi F, Gilli M, Lombardo G, Monarchi G, Pagano S, Tullio A. Fonseca's Questionnaire Is a Useful Tool for Carrying Out the Initial Evaluation of Temporomandibular Disorders in Dental Students. Clin Pract. 2024 Aug 26;14(5):1650-1668. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Szcześniak M, Issa J, Öztürk I, Karahan E, Czajka-Jakubowska A, Orhan K, Dyszkiewicz-Konwińska M. The diagnostic accuracy of cone beam computed tomography in detecting temporomandibular joint bony disorders: a systematic review. Pol J Radiol. 2024 Jun 13;89:e292-e301. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wie C, Dunn T, Sperry J, Strand N, Dawodu A, Freeman J, Covington S, Pew S, Misra L, Maloney J. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy and Biofeedback. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2025 Jan 9;29(1):23. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergmann A, Edelhoff D, Schubert O, Erdelt KJ, Pho Duc JM. Effect of treatment with a full-occlusion biofeedback splint on sleep bruxism and TMD pain: a randomized controlled clinical trial. Clin Oral Investig. 2020 Nov;24(11):4005-4018. Epub 2020 May 19. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Alneyadi M, Drissi N, Almeqbaali M, Ouhbi S. Biofeedback-Based Connected Mental Health Interventions for Anxiety: Systematic Literature Review. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2021 Apr 22;9(4):e26038. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Alfallaj H. Pre-prosthetic orthodontics. Saudi Dent J. 2020 Jan;32(1):7-14. Epub 2019 Aug 27. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Maspero C, Farronato D, Giannini L, Farronato G. Orthodontic treatment in elderly patients. Prog Orthod. 2010;11(1):62-75. Epub 2010 May 11. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erbe C, Heger S, Kasaj A, Berres M, Wehrbein H. Orthodontic treatment in periodontally compromised patients: a systematic review. Clin Oral Investig. 2023 Jan;27(1):79-89. Epub 2022 Dec 11. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Macrì M, Medori S, Varvara G, Festa F. A Digital 3D Retrospective Study Evaluating the Efficacy of Root Control during Orthodontic Treatment with Clear Aligners. Applied Sciences. 2023; 13(3):1540. [CrossRef]

- Festa F, Capasso L, D'Anastasio R, Anastasi G, Festa M, Caputi S, Tecco S. Maxillary and mandibular base size in ancient skulls and of modern humans from Opi, Abruzzi, Italy: a cross-sectional study. World J Orthod. 2010 Spring;11(1):e1-4. [PubMed]

- Minervini G, Franco R, Marrapodi MM, Crimi S, Badnjević A, Cervino G, Bianchi A, Cicciù M. Correlation between Temporomandibular Disorders (TMD) and Posture Evaluated trough the Diagnostic Criteria for Temporomandibular Disorders (DC/TMD): A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. J Clin Med. 2023 Apr 2;12(7):2652. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Häggman-Henrikson B, Ali D, Aljamal M, Chrcanovic BR. Bruxism and dental implants: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Oral Rehabil. 2024 Jan;51(1):202-217. Epub 2023 Aug 17. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| FIRST VISIT | OPERATIVE WORKFLOW |

| general anamnesis | |

| dental anamnesis | |

| gnathological questionnaire | |

| muscles palpation (pain level 3) | |

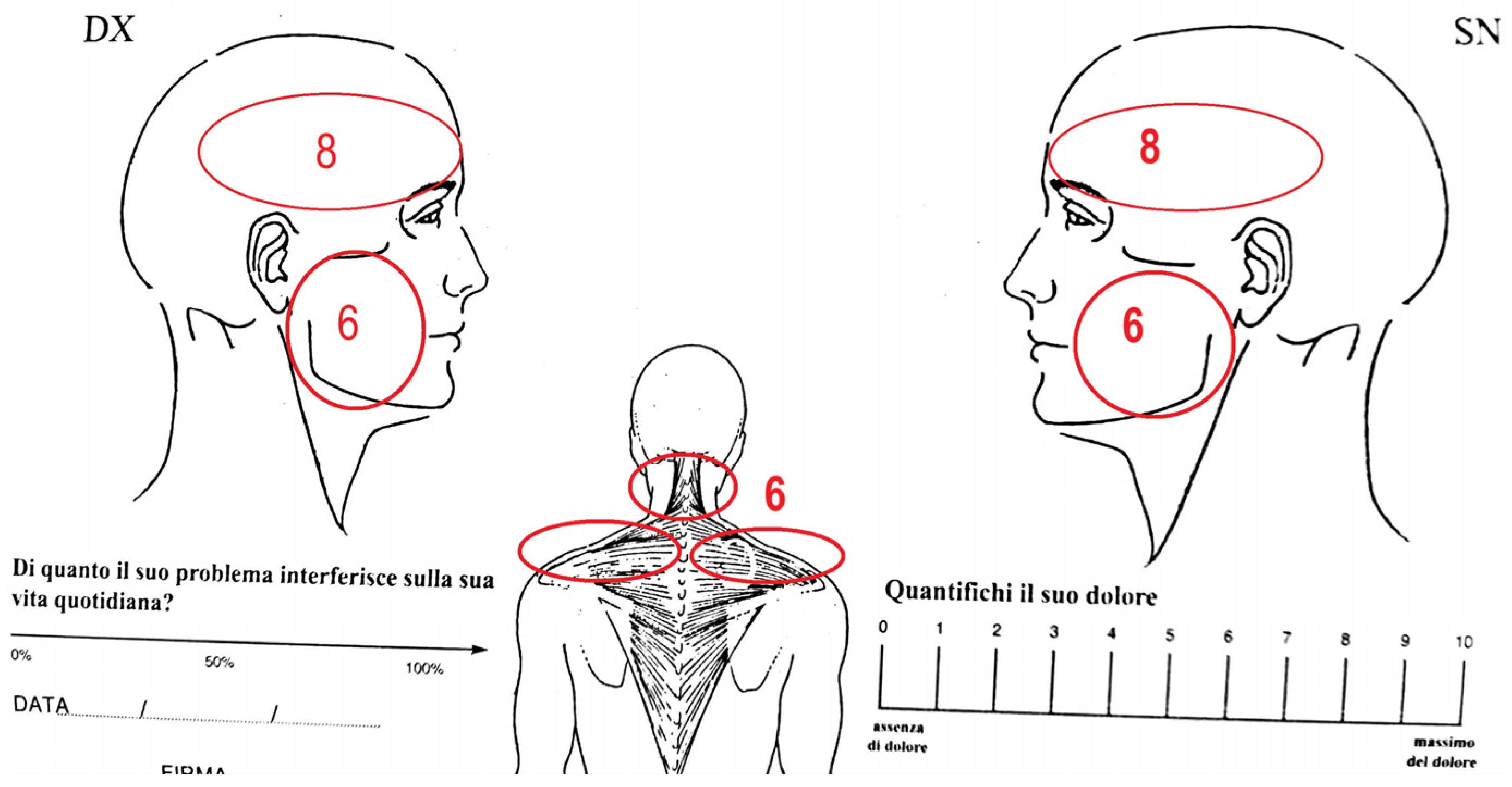

| VAS (pain level 8) | |

| CBCT (t0) | |

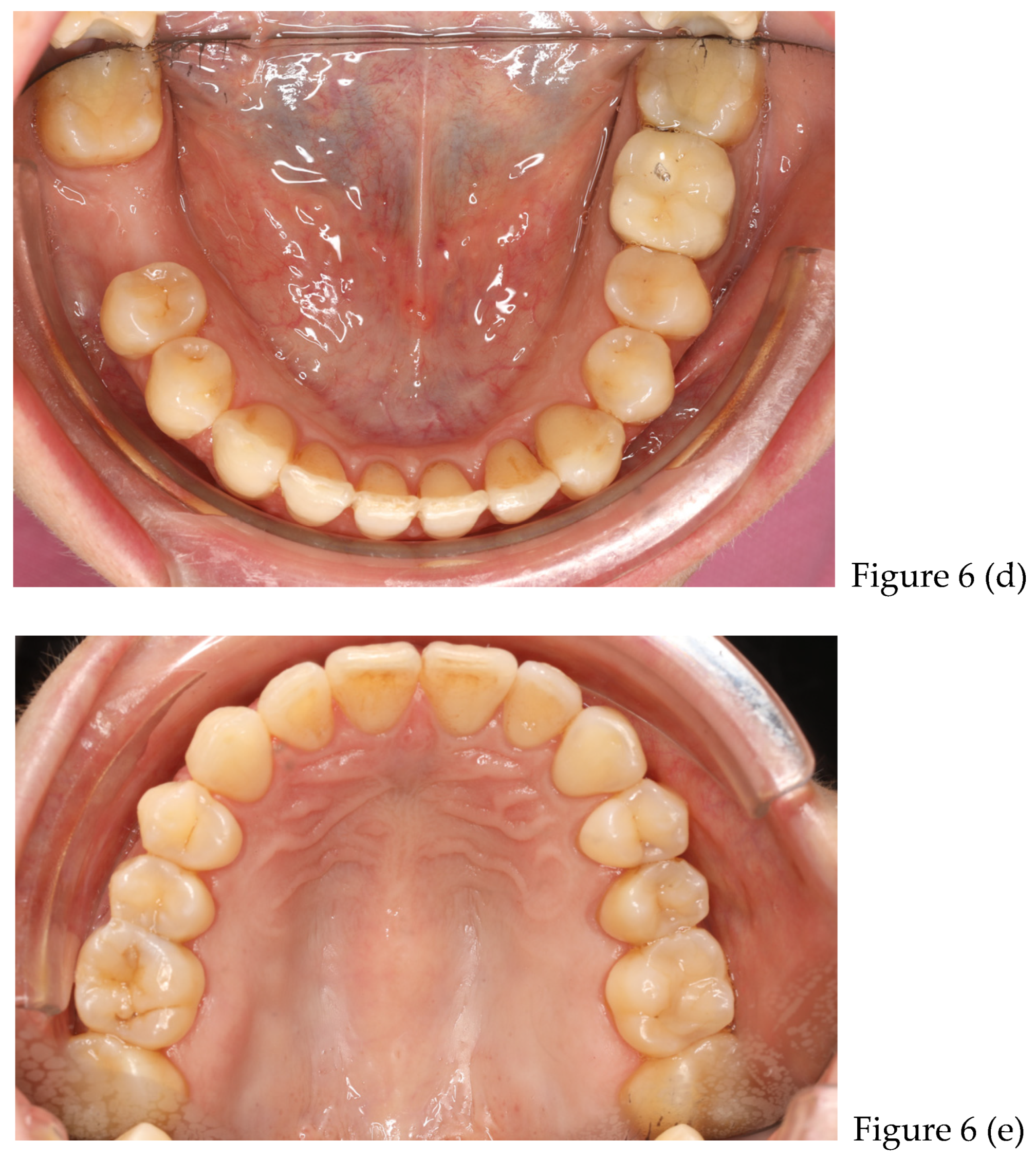

| preliminary photos | |

| DIAGNOSIS | tension type headaches with cleanching |

| GNATOLOGICAL THERAPY | upper and lower splint + biofeedback exercise |

| monthly folow up | |

| after 2 months | VAS (pain level 5) |

| muscles palpation (pain level 2) | |

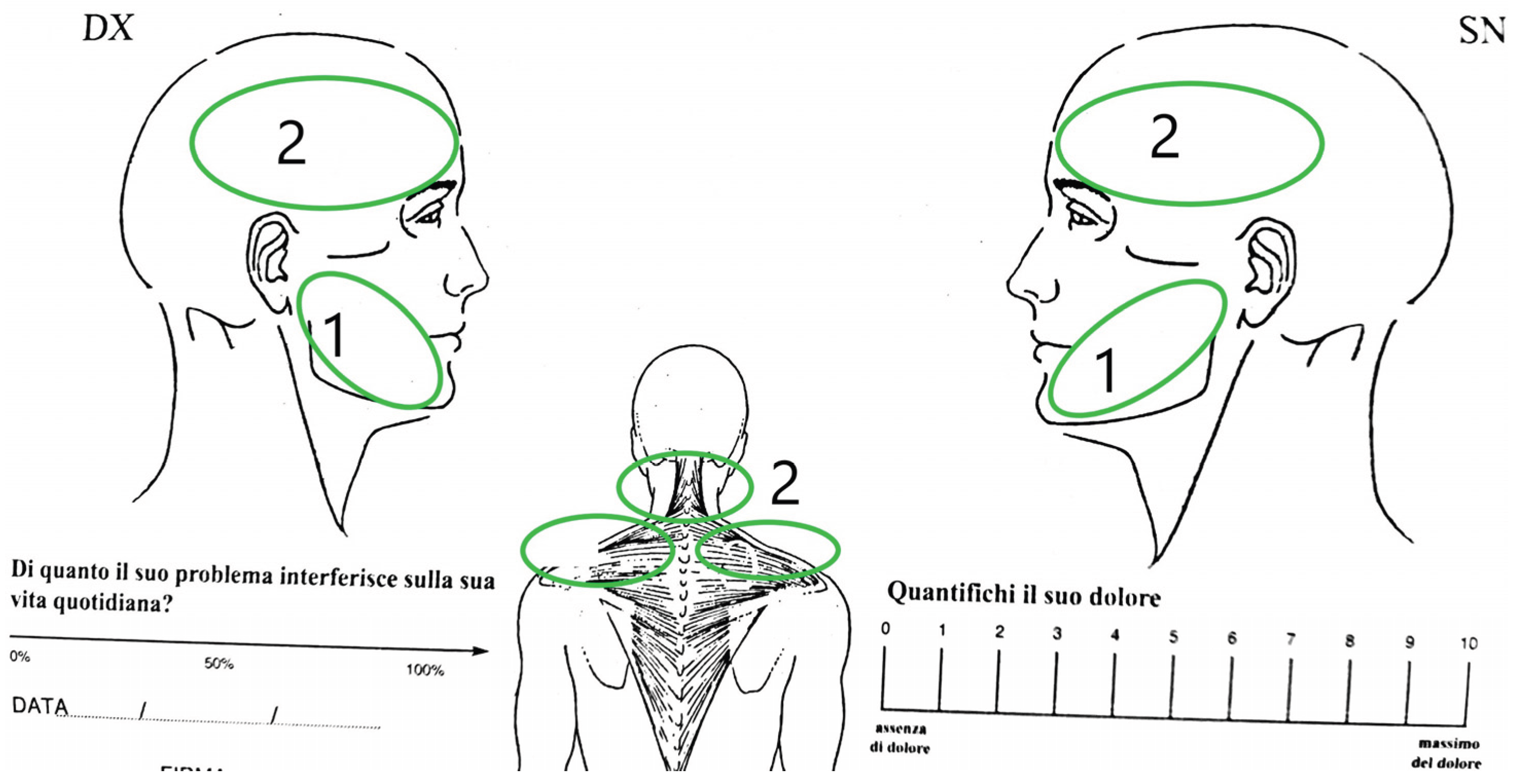

| after 5 months | VAS (pain level 2) |

| muscles palpation (pain level 1-0) | |

| 6 month | no variations/ STABILITATION |

| ORTHODONTIC THERAPY | use of 30 pairs of clear aligners (15 days each couples) |

| after 1 year | refinement with 15 pairs of clears aligners (use 15 days each couples) |

| after 8 months | Retainers + CBCT (t1) + final photos |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).