1. Introduction

We are told that motivation is what moves us. That when we want something badly enough, a goal, a change, a challenge, we act. This belief is foundational in psychology, education, and self-help alike. But lived experience reveals a deeper paradox: individuals can feel urgent, focused, and deeply committed to action, yet remain motionless. They plan, prepare, and even obsess, but do not begin. This is not apathy. It is motivated inaction: a state where intention and inertia coexist.

This paper takes that paradox seriously. Why do people stall at the edge of action even when their motivation is high? Why does the engine of the drive hum, but the vehicle never move?

These questions expose a blind spot in motivational science. For nearly a century, theories of motivation have focused on why we want, how we choose, and what sustains effort. But few have explained why we fail to act when all conditions seem right. This review contends that existing models equate motivation with behavioral readiness, assuming that the presence of desire, value, or drive should be sufficient to trigger action. The failure to act is thus often misread as weakness, procrastination, or avoidance. We argue instead that “feeling stuck” is not a failure of motivation per se, but a failure of readiness ignition, the mechanism by which latent intention transitions into executable behavior.

To explore this idea, we follow a developmental arc through the history of motivational theory, spanning six major conceptual movements:

Classical Foundations (1940s–1960s): Early theories viewed motivation as biological need, psychic energy, field force, or outcome expectancy ([

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8]). They emphasized intensity and direction, but not cognitive friction or activation failure.

Self-Regulation and Cognitive Control (1970s–1990s): With the rise of cognitive psychology, researchers introduced self-efficacy, goal hierarchies, and feedback loops ([

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18]). These models tracked how people pursue goals, but not why they sometimes fail to launch them.

Behavioral Disruption and Grit (2000s): Attention turned to procrastination, self-regulatory failure, decision irrationality, and perseverance under difficulty ([

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31]). Yet many framed inaction as a deviation from rational choice, not as a systemic product of the mind’s architecture.

Culture, Cognition, and Cost (2010s): Integrative work blended cultural psychology, emotional salience, and effort cost into motivational theory ([

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41,

42,

43,

44,

45]). These models mapped context and constraint but remained fragmented.

Mechanistic and Computational Models (2016–2020): Neuroscientific and rational theories modeled motivation as cost-benefit optimization, incorporating effort economics and task control architectures ([

46,

47,

48,

49,

50]). Still, they lacked a unified theory of why readiness sometimes fails to ignite.

Cognitive Drive Architecture and Lagunian Dynamics (2025): We end with a synthesis. Lagun’s Cognitive Drive Architecture is introduced not as a model, but as a field, a formal substrate for understanding ignition, inhibition, and internal architecture of cognitive drive systems. Through foundational works ([

51,

52,

53,

54,

55]), we explore constructs like primode, activation potential, anchory, and slip, variables that mechanistically explain why motivation does not always convert to action.

This review does not dismiss prior theories. Each contributed crucial insight. But as motivational science evolved, so did its blind spots, and none fully resolved the paradox of being “ready in mind but frozen in behavior.” By tracing these conceptual layers, we argue that motivation without readiness is not a deficit of will but a misalignment of architecture.

In closing, we propose that the next frontier in motivation research must move beyond “what drives us” toward understanding what switches us on, cognitively, dynamically, and contextually.

2. Classic Foundations of Motivation (1940s–1960s)

The earliest formalizations of motivation theory in psychology emerged between the 1940s and 1960s, when researchers attempted to systematize what compels human behavior. These theories were rooted in three key metaphors: biological drive, psychic force, and cognitive expectancy. Though differing in emphasis, all shared one assumption: that motivation operates as a scalar quantity; more drive should yield more action.

Abraham Maslow’s influential hierarchy [

1] organized human needs into ascending layers, from physiological survival to self-actualization. Maslow reframed motivation as a progression through unmet needs, positing that higher-level goals only emerge once basic needs are satisfied. His model shaped generations of motivational psychology, yet left out any mechanistic account of how needs are translated into behavior, particularly in moments when higher needs dominate but action does not follow.

Kurt Lewin, in contrast, offered a spatial and dynamic approach. In field theory, motivation was a function of the person within their psychological environment [

2]. Behavior resulted from the interaction of internal tensions and environmental forces, pulling the agent toward or away from certain goals. While elegant, Lewin’s model required a clear directional field to predict action, yet failed to explain motivational paralysis within a force-laden system.

Building on this, Leon Festinger introduced cognitive dissonance theory [

4], suggesting that individuals are motivated to resolve inconsistencies between beliefs and actions. Dissonance created psychological discomfort, which in turn triggered corrective behavior. However, the model was reactive rather than generative; it explained motivation in terms of error correction, not ignition failure. A person may fully believe in an action, feel tension in not doing it, and still remain frozen.

Meanwhile, Clark Hull proposed a drive-reduction model grounded in behaviorism [

5]. Organisms, he argued, act to reduce internal tension caused by unmet physiological needs. The stronger the drive, the more likely the behavior. But critics noted that Hull’s model could not explain curiosity, overachievement, or the experience of feeling stuck despite strong drive.

David McClelland added psychological nuance to motivation with his theory of needs, focusing on achievement, power, and affiliation as stable dispositional drivers [

6]. He emphasized the learned nature of motives, marking a shift from reflex to cognition, yet still failed to account for situations where motives are active but behavior does not initiate.

Victor Vroom’s expectancy theory provided a cognitive formalization of choice behavior, positing that motivation is a product of expectancy (likelihood of success), instrumentality (link between action and outcome), and valence (value of outcome) [

7]. Motivation, in this view, is a function of beliefs. However, the theory implicitly assumed that high expectancy and high value would necessarily translate into action, a claim contradicted by the phenomenon of motivated inaction.

Finally, Julian Rotter’s locus of control theory [

8] introduced the idea that individuals differ in their generalized expectancies about control over reinforcements. People with an internal locus believe outcomes are contingent on their own actions; those with an external locus attribute outcomes to chance or external forces. While useful for predicting persistence and learning strategies, this framework did not address internal blockage, when internally motivated individuals still do not act.

2.1. The Conceptual Gap

Together, these foundational theories laid critical groundwork for understanding motivation. They clarified that motivation involves both internal tension and goal-directed expectancy. Yet all implicitly treated motivation as sufficient for action. That is, if one has a strong enough drive, desire, or expectancy, action should follow.

What they did not account for, and could not explain, was the experience of being mentally mobilized but behaviorally paralyzed. The models were analog, not architectural. They assumed that energy input would lead to output but had no language for cognitive inertia, readiness lock, or latent interference.

This left a structural blind spot: how motivation is internally organized and when it fails to ignite, even when drive is high. That blind spot would become the starting point for the next era of motivational theory, one focused not on drive itself, but on how goals are activated, regulated, and blocked within the cognitive system.

3. Emergence of Self-Regulation and Cognitive Models (1970s–1990s)

By the 1970s, cracks had formed in the classical drive-based theories of motivation. Researchers began to shift away from scalar concepts like “strength of desire” toward a richer understanding of how goals are cognitively represented, regulated, and monitored over time. The dominant metaphor was no longer hydraulic or energetic; it became cybernetic. Motivation was increasingly viewed as a dynamic feedback system, with internal standards, self-monitoring, and control mechanisms playing central roles.

This era marked the rise of self-regulation as the dominant paradigm, and with it, a conceptual pivot: rather than asking only what drives action, theorists began to ask how goals are maintained, disrupted, or stalled across time and competing contexts.

3.1. Cognitive Control and Feedback Models

Albert Bandura’s landmark theory of self-efficacy reframed motivation as a function of perceived capability: people are more likely to initiate and persist in actions when they believe they can succeed [

9]. Self-efficacy became a powerful predictor of engagement, effort, and resilience, but Bandura’s model could not fully explain why individuals with high self-efficacy sometimes failed to act.

Carver and Scheier extended this view through control-process theory, treating behavior as governed by feedback loops comparing current states to desired states [

11]. Motivation, in this model, arises when a discrepancy is detected and maintained until resolved. This cybernetic framing brought structure to the moment-to-moment regulation of action but offered limited insight into the pre-initiation phase, when intention exists but action does not begin.

Similarly, Locke and Latham’s goal-setting theory emphasized the role of clear, challenging goals in driving task performance [

12]. Goals focused attention and sustained effort. Yet again, the model emphasized performance once goals were active, not the failure to ignite even when goals are meaningful and well-specified.

Csikszentmihalyi’s flow theory [

13] offered a phenomenological lens on optimal engagement, a state where skill and challenge align, and action unfolds seamlessly. But “flow” is what happens after ignition. The model described peak performance, not the friction preceding action.

Ajzen’s theory of planned behavior [

14] proposed that intention, combined with perceived behavioral control and subjective norms, predicts action. While influential, this framework treated intention as the primary engine of behavior. It did not address instances where intention is strong but implementation is frozen, a gap known in the literature as the “intention–behavior gap.”

Loewenstein’s work on visceral factors [

16] introduced the idea that affective and bodily states can override rational planning, distorting temporal preferences and disrupting goal pursuit. While this introduced emotional noise into the system, it still positioned failure to act as irrational override, not architectural blockage.

3.2. Emerging Concepts of Failure and Delay

During this era, procrastination research gained traction, casting light on how motivation interacts with delay, avoidance, and internal conflict. Solomon and Rothblum [

10] explored academic procrastination as a function of anxiety, task aversion, and irrational delay, reframing inaction as a defensive response, not just laziness. Baumeister and Heatherton’s model of self-regulation failure [

15] positioned impulsivity and ego depletion as core disruptors. Tice and Baumeister later showed that procrastination could have both short-term emotional benefits and long-term costs [

17].

Ryan and Deci’s self-determination theory [

18] provided perhaps the most comprehensive integration, distinguishing between intrinsic and extrinsic motivation and linking behavior to underlying psychological needs for competence, autonomy, and relatedness. While powerful in explaining motivational quality, SDT focused on why we value goals, not why goal pursuit fails to initiate despite strong value alignment.

3.3. The Gap: Mechanism Without Ignition

What these models shared was a shift in emphasis from drive to structure, feedback loops, beliefs, affect, and intention. Motivation became a system of internal regulation rather than external pressure. Yet across the board, these theories assumed that once intention is formed and self-efficacy is high, action follows. That assumption has proven false.

The gap remained unaddressed: what happens when all cognitive variables align, but action does not begin? None of these models offered a precise mechanism for the breakdown of readiness, nor did they explain why the system can stall, even when goals are clear, values are aligned, and the desire to act is intense.

This unmodeled space, cognitive readiness failure, would become the crucible for 21st-century theories focused on procrastination, dual-process models, and the neuroscience of control and effort.

4. Procrastination, Grit, and Modern Behavioral Models (2000s)

As the new millennium unfolded, the motivational sciences turned their gaze to failure, not as pathology, but as data. Procrastination, impulsivity, irrational choice, and stalled effort became central lenses for re-examining how motivation breaks down. What emerged was a fragmented yet powerful set of insights: motivation could be high, yet action delayed. Desire could be focused, yet behavior absent. In other words, being stuck while motivated was no longer anomalous; it was empirically ubiquitous.

This period saw a shift away from clean models of goal pursuit and toward the messy, nonlinear mechanics of cognitive friction, behavioral failure, and effort aversion.

4.1. Procrastination as a Window into “Stuckness”

Procrastination became a key phenomenon through which motivational failure was examined. Joseph Ferrari’s work highlighted procrastination as a chronic form of self-regulation breakdown, tied not only to time mismanagement but also to self-awareness and cognitive load [

21]. Schraw, Wadkins, and Olafson provided a grounded theory of academic procrastination, framing it as a negotiation between emotional cost, task aversiveness, and perceived coping resources [

28].

Steel’s comprehensive meta-analytic review recast procrastination as the “quintessential self-regulatory failure,” linking it to temporal discounting, impulsivity, and intention-action disconnects [

27]. These works collectively suggested that procrastination is not the absence of motivation but the presence of unresolved inner friction.

Tice and Baumeister’s longitudinal research underscored the affective costs of procrastination; short-term relief from task avoidance often yielded long-term stress and diminished performance [

17].

4.2. Decision-Making and Irrationality

Concurrently, the rise of behavioral economics reframed human motivation in terms of bounded rationality. Dan Ariely’s work emphasized how predictable irrationalities, loss aversion, present bias, and social framing distort behavior even when goals are well defined [

19]. Thaler and Sunstein’s nudge theory pushed further, showing that even subtle changes in context could dramatically shape whether actions are taken or deferred [

30].

While these theories described why decisions deviate from rational expectations, they did not offer a mechanistic model of mental gridlock, a structure for understanding how cognitive architecture itself can lock up despite clear incentives and strong intentions.

4.3. Grit and Goal Persistence

Angela Duckworth’s theory of grit reframed persistence as a trait: passion and perseverance toward long-term goals [

26]. Grit became a celebrated counterweight to theories of impulsivity and delay. Yet critics noted its descriptive limitations: it described who keeps going, not why action fails to start. Similarly, Eccles and Wigfield’s motivational belief models [

23] and Heine’s cross-cultural work on the self as a cultural product ([21]) emphasized the variability in goal adoption and pursuit, but not the mechanisms of readiness breakdown.

Adams’ research into “enemyship” as a cultural norm revealed that relational friction, especially in collectivist cultures, could inhibit action even when individual motivation is strong [

25]. These findings hinted at a deeper architecture beneath the motivational surface, where social context, emotional tension, and internal conflict subtly modulate readiness.

4.4. Neurobiological Influences on Motivation

Motivational neuroscience also began to provide biological correlates. Kent Berridge’s work reframed dopamine not as a pleasure chemical but as a marker of incentive salience, the “wanting” system that activates pursuit [

29]. Botvinick introduced hierarchical models of prefrontal control, showing how task representation and effort weighting are organized in layers of priority [

31].

Ryan and Deci revisited self-determination theory [

20], offering empirical validation for the idea that autonomy, competence, and relatedness sustain deep motivation, but even they left open the question of why fully autonomous goals sometimes do not activate behavior.

Baumeister’s “ego depletion” hypothesis posited that self-control is a limited resource that can be exhausted by prior exertion [

24], contributing to task delay or avoidance. But follow-up studies revealed mixed results and raised doubts about whether depletion was metabolic or motivational in nature.

4.5. The Gap: Describing Failure Without Modeling Readiness

Across this phase of motivational science, the symptoms of stuckness were richly described: cognitive overload, emotional aversion, impulsivity, fear of failure, and low grit. Yet these accounts remained post hoc: they explained why people don’t act, not why the brain fails to ignite behavior under favorable motivational conditions.

Despite acknowledging that people can be “motivated but inert,” the field lacked a core theory to explain how latent task structures, competing intentions, or cognitive effort thresholds could systemically block action even when no external barrier is present.

This realization would drive the next wave of research, one that looked more deeply at culture, cognition, and the cost architecture of control.

5. Culture, Emotion, and Cognitive Cost (2010s)

The 2010s brought a turning point in motivational psychology: a growing realization that motivation does not operate in a vacuum. Cultural norms, emotional states, and mental resource constraints emerged as powerful modulators of action. Rather than assuming motivation as a self-contained force, researchers began to treat it as embedded, shaped by environment, governed by cognitive economics, and susceptible to emotional friction.

Yet, even as the lens widened, the core paradox remained unsolved: Why do people remain immobilized despite clarity, desire, and opportunity? This section explores how fragmented perspectives, from cultural cognition to neural economics, edged toward an answer without fully arriving.

5.1. Culture and Self-Construal

Richard Nisbett’s cross-cultural research challenged the Western assumption of the independent, choice-driven self. He revealed that Eastern and Western cognitive styles differ systematically, the former more relational and context-sensitive, the latter more analytic and autonomous [

34]. Markus and Kitayama deepened this analysis, contrasting interdependent versus independent self-construals and demonstrating how motivation is filtered through relational obligations, not just personal desires [

44].

Heine’s work further showed that self is not a universal psychological structure but a cultural product that shapes what kinds of goals are valued and what internal conflicts arise in their pursuit [

22]. These insights reframed motivation not as a fixed engine but as a culturally tuned system. Yet even these rich accounts left unexplored how culture affects the cognitive architecture of task readiness.

Gelfand’s global study on tight vs. loose cultures added another dimension: the regulatory intensity of context. In tight cultures, strict norms constrain behavior, potentially reinforcing motivational inhibition even when goals are internally desired [

36].

5.2. Emotion, Self-Regulation, and Delay

Pessoa synthesized findings from neuroscience and cognitive psychology to argue that emotion and motivation jointly influence executive control [

32]. Emotional salience can amplify or suppress task engagement, even when cognitive intent remains stable. Pychyl explored this idea in the domain of procrastination, emphasizing that emotional aversion, not laziness, drives much of our motivational failure [

33].

Sirois introduced self-compassion as a protective factor against the stress of procrastination, showing that gentler self-evaluation improved task engagement [

45]. Mischel’s delayed gratification experiments, famously embodied in the “marshmallow test,” provided long-term evidence that self-regulatory capacity predicts life outcomes but also revealed the fragility of control under stress or ambiguity [

42].

Inzlicht, Schmeichel, and Macrae proposed that self-control may not be resource-limited per se, but rather governed by a cost-benefit decision-making process, people exert control only when it feels worthwhile [

43].

5.3. Cognitive Cost and Opportunity Structures

The idea that cognitive control is not “spent” but calculated marked a profound shift. Kurzban and colleagues introduced the opportunity cost model of mental effort, suggesting that cognitive labor feels costly when other attractive alternatives are mentally available [

39]. Kool and Botvinick added the concept of control cost: the brain assigns a subjective value to exerting effort, often biasing toward default, low-effort behaviors [

38].

These models approached a key insight: the experience of stuckness may arise from invisible cost-weighting within the mind itself. Not from lack of motivation, but from internal architecture that evaluates and suppresses action before it begins.

Holroyd and Yeung argued that the anterior cingulate cortex motivates extended behaviors by detecting prediction errors, a kind of “neural critic” that may inhibit action when internal coherence is low [

37]. Kahneman’s “dual process” theory, fast vs. slow thinking, supported this, positing that reflective action requires effort and is easily abandoned in favor of intuitive inaction [

35].

Ryan and Deci’s revisited work in this decade acknowledged that autonomous motivation can be undermined by environmental or internal complexity [

40], and Dweck emphasized that self-theories of ability and identity shape task engagement, especially under threat or ambiguity [

41].

5.4. The Gap: Toward a Mechanistic Account of Readiness Breakdown

This era offered profound theoretical insight: motivation is cultural, emotional, and cognitively costly. But what remained elusive was a unifying account of how these forces interact within the mind to prevent behavior. There was no central model of ignition failure, only parallel fragments:

Cultural norms shape what we pursue.

Emotion governs when we approach or avoid.

Cognitive effort defines whether we act at all.

But what is the architecture of this breakdown? How does the system stall when value, belief, and context align? These questions set the stage for the next phase, where models became mechanistic, computational, and increasingly embedded in the neuroscience of cost-benefit control.

6. Advanced Mechanistic and Rational Models (2016–2020)

By the late 2010s, motivation science had moved into its most computationally explicit era. Scholars stopped asking simply why we pursue goals and turned their attention to when and why goal-directed behavior fails to initiate. Emerging models emphasized effort as a cost-calculating function, positioning mental work not as a passive output of desire but as an actively regulated decision variable. The key question became: What determines whether a motivated individual converts intention into action or stalls at the threshold of execution?

This new wave of models brought unprecedented precision to motivational theory. Yet, as we will see, even the most advanced mechanistic accounts fell short of explaining the final failure point, the system’s inability to cross its own internal ignition threshold.

6.1. The Brain Computes Effort, Not Just Desire

Shadmehr, Huang, and Ahmed (2016) provided a critical bridge between neuroeconomics and motor control, demonstrating that effort has a physical representation in the brain. The cost of action, whether physical or cognitive, is encoded and weighted in the decision to engage [

46]. In this view, effort is not an afterthought; it is a front-loaded variable in the behavioral calculus.

Building on this, Shenhav et al. (2017) introduced the Expected Value of Control (EVC) model, formalizing how the brain evaluates whether to deploy mental resources. According to EVC, control is recruited when its predicted benefits outweigh its anticipated costs, thus situating executive effort as an adaptive, decision-level mechanism [

47].

These models marked a leap forward. They showed that “failure to act” isn’t always emotional avoidance or cognitive depletion, it could be a rational (if implicit) refusal to pay a subjective cost.

6.2. Dopamine, Willingness, and Effort Bias

Westbrook et al. (2020) added critical neurochemical evidence by showing that dopamine biases decisions toward cognitive effort [

49]. Rather than merely signaling reward, dopamine may tip the balance in favor of difficult tasks by inflating the subjective benefit of effortful work. This introduced a powerful insight: individuals may stall not due to lack of motivation, but due to dopaminergic underweighting of effort-benefit ratios.

In other words, readiness may fail not because of poor goals or limited ability, but because the system fails to see the act as worth it in real-time computations.

6.3. Resource-Rationality and the Architecture of Delay

Lieder and Griffiths (2020) advanced the theory of resource-rational cognition, proposing that human minds are not irrational per se but are optimized for ecological efficiency [

50]. Failures of motivation are not failures of will; they are intelligent adaptations to resource scarcity, competing demands, and uncertainty. Within this model, procrastination and disengagement are not dysfunctions but strategic deferrals.

However, this model, like its predecessors, lacks a clear architecture for readiness paralysis: it explains why people may delay, but not why no action is taken even when no better option exists. It accounts for rational delay, but not for non-execution under coherent goals and open bandwidth.

6.4. Implementation Intentions and Partial Automation

Gollwitzer (2018) emphasized implementation intentions as a method for reducing the friction of decision-making [

48]. By pre-specifying “if-then” cues, individuals reduce the cognitive cost of goal activation. While powerful for habit formation and adherence, this framework presumes a functional ignition system, it does not address why some goals fail to launch entirely, even when implementation intentions are in place.

6.5. The Remaining Gap: Readiness Ignition Failure

Taken together, these models build a compelling theory of why effort feels costly, how it is computed, and when it is avoided. But all of them stop short of modeling ignition, the final step in which cognitive readiness becomes motor execution.

The key paradox remains:

What causes motivated individuals to stall at the doorstep of action, even when no obvious conflict, depletion, or opportunity cost is present?

This is the phenomenon that the models of 2016–2020, despite their elegance, fail to resolve. They give us the economics of control, but not the dynamics of drive ignition. They offer rational explanations of disengagement, but not systemic accounts of “motivated paralysis.”

This theoretical boundary marks the need for a new field, one that reconceptualizes motivation as a system of thresholds, latent architecture, and dynamic ignition states.

That field is Cognitive Drive Architecture (CDA). And at its core lies Lagunian Dynamics, introduced in 2025 [

51].

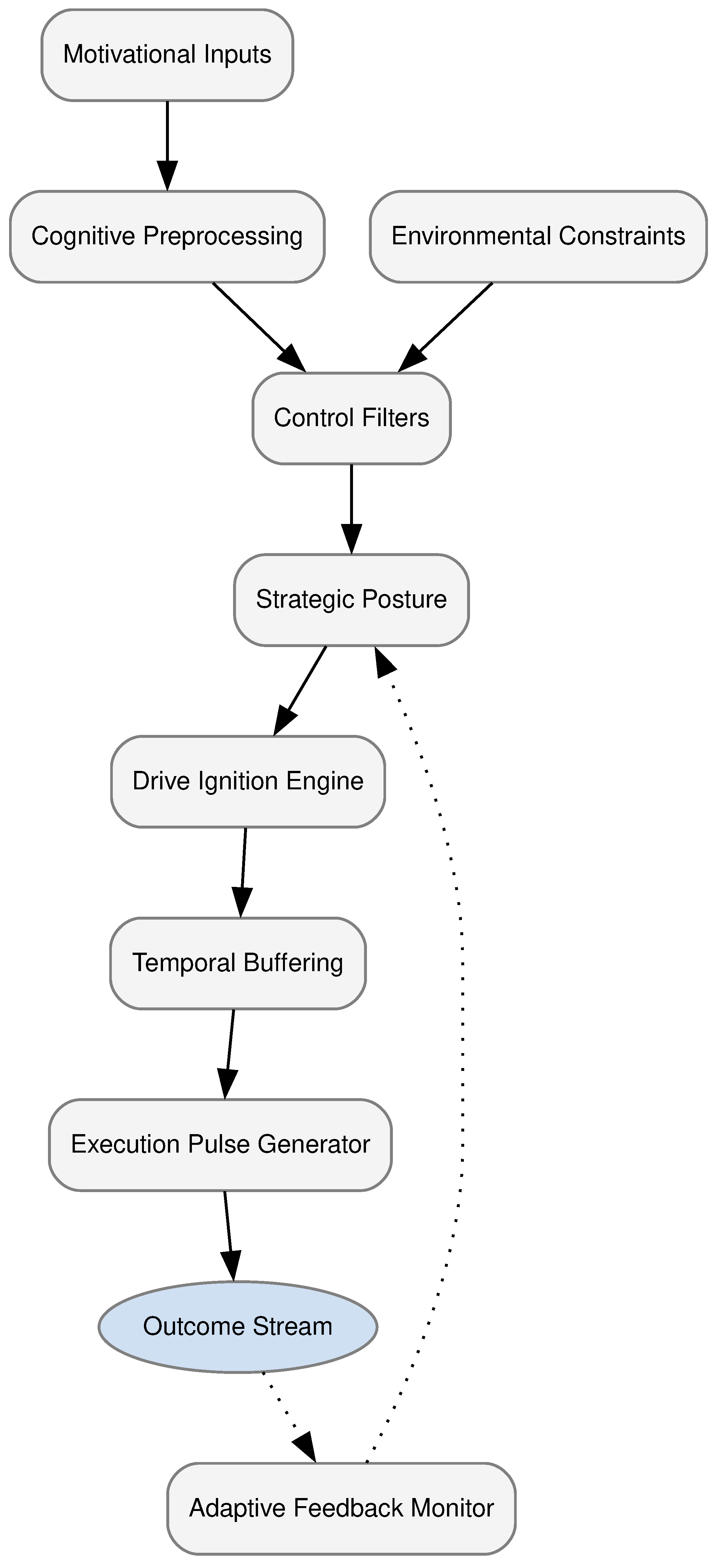

Figure 1.

Cognitive drive architecture control flow.

Figure 1.

Cognitive drive architecture control flow.

This figure presents an abstract, modular view of volitional effort regulation within a cognitive control framework. The process begins with Motivational Inputs (such as goals, needs, and affective drivers), which feed into Cognitive Preprocessing for internal prioritization. In parallel, Environmental Constraints (including task structure, time pressure, or social context) influence downstream control demands. Both channels converge at Control Filters, which act as decision gates that shape the agent’s Strategic Posture, a dynamic representation of readiness or commitment to act.

Once established, strategic posture triggers the Drive Ignition Engine, a mechanism responsible for activating goal-directed volitional force. This output is passed through Temporal Buffering, which allows for pacing, calibration, or intentional delay. The Execution Pulse Generator then transforms buffered signals into executable commands. These lead to the Outcome Stream, which represents observable behavioral or cognitive outputs. A recursive Adaptive Feedback Monitor evaluates the outcome and informs adjustments to strategic posture, completing a closed-loop control cycle. This architecture offers a structured basis for modeling adaptive and context-sensitive volitional behavior.

7. Culmination: Lagun’s Cognitive Drive Architecture (2025)

All prior theories, from Maslow to dopamine, aimed to explain what makes us want to act. But wanting, as we now know, is not doing. By 2025, it was increasingly clear that no existing model accounted for the experience of being fully motivated but inert. That is, the experience of cognitive ignition failure.

This is where Lagunian Dynamics enters, not as a theory within motivation science, but as the substrate of a new theoretical field: Cognitive Drive Architecture (CDA). Rather than adding to the stack of motivational models, CDA redefines the entire problem space [

55].

7.1. Lagunian Dynamics: A First Principles Theory of Drive-Effort Coupling

Nikesh Lagun’s Lagun’s Law (2025) lays the foundation: action is not the outcome of motivation alone, but of an interaction between drive and latent task architecture. Motivation without ignition is treated not as failure but as a distinct system state, a decoupling of internal drive from its cognitive execution pathway [

51].

The theory introduces six fundamental variables (Primode, Cognitive Activation Potential (CAP), Flexion, Anchory, Grain, and Slip) to model how cognitive systems transition (or fail to transition) from desire to readiness. These variables are not metaphors; they are functional descriptors in a control-theoretic model of internal behavior regulation.

For the first time, we are not asking what causes motivation, but what allows it to move.

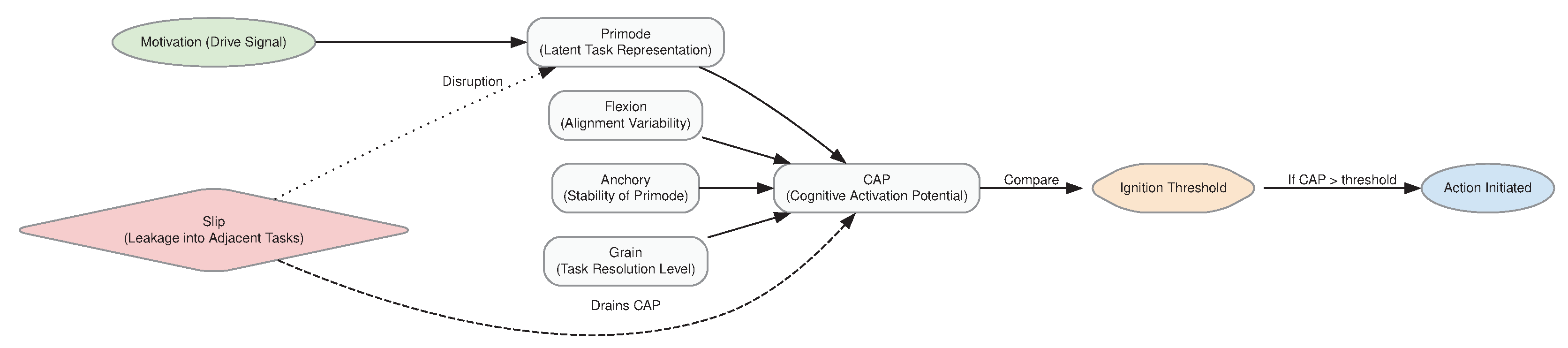

Figure 2.

Ignition Dynamics in Lagunian Theory within the Cognitive Drive Architecture Field.

Figure 2.

Ignition Dynamics in Lagunian Theory within the Cognitive Drive Architecture Field.

This schematic visualizes the ignition model described by Lagunian Dynamics, a core theory within the broader field of Cognitive Drive Architecture (CDA). The diagram outlines six key variables that govern ignition readiness: Primode (the latent task representation), Cognitive Activation Potential [CAP], Flexion (variability of drive-task alignment), Anchory (resistance to Primode decay), Grain (task resolution granularity), and Slip (displacement of activation toward competing tasks). In this model, motivation activates a Primode, which attempts to generate CAP. CAP is influenced by internal dynamics such as Flexion, Anchory, and Grain. If CAP surpasses an ignition threshold, action begins. If it fails, the system stalls, often due to Slip or insufficient convergence. This figure presents motivated inaction as a systemic ignition failure, not as a deficiency of motivation itself. CDA serves as the epistemic domain for such mechanistic explanations.

7.2. Cognitive Thermostat Theory: Modeling Ignition Thresholds

Building on Lagun’s Law, Cognitive Thermostat Theory (CTT) (2025) models the dynamic thresholds for effort ignition. Like a thermostat that regulates when heating activates, the mind continuously computes whether the "temperature" of drive is sufficient to overcome internal resistance. Crucially, this threshold is not fixed; it adapts based on prior success, uncertainty, emotional resonance, and system noise [

52].

CTT explains why individuals sometimes stall even with high intention: the cognitive threshold has not been met or is distorted by interference between latent tasks.

This gives formal structure to what older models left vague: readiness is not linear, and motivation must exceed ignition cost to trigger action. When that threshold is mismatched due to mental overload, misaligned context, or unresolved intentions, the system locks into drive inhibition, despite no decrease in desire.

7.3. Latent Task Architecture: The Lock-Up Mechanism

In Latent Task Architecture (LTA) (2025), Lagun expands on the idea that multiple intentions exist in latent competition. A person may consciously pursue a task (e.g., finishing a report) while unconsciously maintaining unresolved commitments (e.g., emotional reconciliation, unprocessed anxiety), which occupy readiness bandwidth.

This theory introduces a vital insight: the feeling of stuckness is not a lack of energy but a breakdown in task resolution. Competing primodes, intention-specific readiness signals, can block ignition unless a resolution pathway is cleared [

53].

In essence, the mind can be motivated but congested. This is not procrastination as laziness or error; it is an emergent property of unresolved drive routing.

7.4. Switch ON: From Theory to Real-World Activation

Finally, Switch ON (2025) translates the full theory into practical methods for unlocking cognitive drive. It introduces structured protocols for identifying blocked primodes, realigning ignition thresholds, and regulating internal drive thermodynamics [

54].

Unlike interventions based on grit, willpower, or rational goal-setting, Switch ON works by reprogramming the cognitive ignition system itself, a system that classical motivation theory never formally recognized. It shifts the focus from what the individual wants to what the system is ready to release.

7.5. The Emergence of a New Field: Cognitive Drive Architecture (CDA)

It’s important to be precise here: Lagunian Dynamics is not a motivational framework or a model; it is a theoretical substrate. CDA is not a competing theory among others. It is a distinct field, a systems-level container that holds a fundamentally new paradigm:

Drive is not scalar (more vs. less) but dynamical (active vs. blocked states).

Readiness is not guaranteed by desire; it is governed by ignition architecture.

Stuckness is not a failure of will but a misalignment of internal execution architecture.

In this formulation, CDA doesn’t negate earlier models; it absorbs and recontextualizes them. Maslow’s needs become primode configurations. Dopaminergic valuation becomes part of the ignition cost calculus. Implementation intentions become externalized switch cues [

55].

Where others explained what motivation is, CDA explains how motivation moves, or doesn’t.

8. Discussion & Implications

Across more than eight decades of research, motivational science has evolved from descriptions of basic human needs to intricate computational models of decision-making. Yet one critical paradox has remained unaddressed until recently: why do people feel stuck even when they are fully motivated? Why, in the absence of conflict, distraction, or depletion, does behavior still fail to launch?

This review has traced that paradox through the history of motivational theory, not merely to summarize developments, but to expose their systemic blind spots. At every stage, we’ve seen progress:

From drive and expectancy theories that lacked mechanism

To self-regulation and cognitive control models that lacked ignition logic

To resource-rational and neuroeconomic models that computed effort but not execution failure

Each approach offered crucial pieces, but none provided a systems-level model for readiness failure. Until the emergence of Lagunian Dynamics and, with it, the field of Cognitive Drive Architecture (CDA), the phenomenon of “motivated paralysis” remained unmodeled.

8.1. Implications for Theory: Readiness as a Missing Construct

The core theoretical contribution of CDA is that motivation and readiness must be decoupled. The presence of goals, intentions, and values does not guarantee behavioral activation. Readiness, governed by ignition thresholds, task architecture, and internal bandwidth, is a separate subsystem, with its own dynamics and failure modes.

This reconceptualization positions stuckness not as failure, but as friction: a temporary lock-up caused by unresolved latent drives, competing primodes, or mismatched ignition thresholds. By modeling these mechanisms formally, CDA does for motivational theory what control theory did for engineering: it brings precision, diagnostics, and intervention targets.

8.2. Implications for Practice: Toward Activation-Based Interventions

-

Procrastination Treatment:

Traditional interventions focus on reducing avoidance, increasing willpower, or enhancing reward salience. CDA suggests a new route: diagnosing primode interference and recalibrating cognitive thermostats to realign readiness with intention. Switch ON, as a real-world protocol, provides mechanisms for identifying where ignition fails and how to repair it [

54].

-

Goal-Setting Psychology:

SMART goals and implementation intentions are useful but incomplete. CDA implies that goal architecture must be coupled with ignition architecture, ensuring that tasks are not just defined but cognitively routable. This could reshape how we teach and structure productivity systems.

-

Behavioral Therapy and Mental Health:

Therapists often treat inaction as depressive or avoidant. CDA provides a different lens: perhaps the client is not unwilling or irrational but locked in unresolved latent tasks. This could shift therapeutic attention from motivation enhancement to readiness realignment.

-

Education and Executive Function:

In students, “laziness” is often diagnosed where primode congestion may be the real issue. Understanding how latent cognitive loads block ignition can inform new pedagogies, time design, and adaptive learning environments that support not just engagement but release into action.

9. Conclusion

This review suggests that being stuck while motivated is not a contradiction; it is a predictable failure mode of cognitive architecture. The problem was never that we didn’t want enough; it’s that our systems couldn’t release the readiness needed to begin.

Lagunian Dynamics does not replace older motivational theories; it completes them by introducing the architecture of ignition, friction, and cognitive drive flow. It absorbs historical insights, from Maslow’s needs to dopamine’s salience, and repositions them in a dynamic control framework.

Future research should focus on empirically validating the parameters of primode architecture, ignition thresholds, and readiness transitions through behavioral data, neuroimaging, and intervention studies. Just as early emotion research evolved into affective neuroscience, motivational science is now poised to evolve into ignition science.

We began with a question: Why do I feel stuck even when I’m motivated?

We end with a model and a field that is finally capable of answering it.

Author Contributions

No funding was received for this work.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

CRediT Authorship Contribution Statement: Nikesh Lagun: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Visualization.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no competing interests.

References

- Maslow, A.H. A theory of human motivation. Psychological review 1943, 50, 370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewin, K.; Cartwright, D. Field theory in social science: Selected theoretical papers; Harper: New York, 1951. [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson, J.W. Motivational determinants of risk-taking behavior. Psychological review 1957, 64, 359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Festinger, L. A theory of cognitive dissonance (T. 2), 1957.

- Hull, C.L. (Ed.) Principles of behavior: An introduction to behavior theory; Appleton-Century-Crofts: New York, 1959. [Google Scholar]

- McClelland, D.C. Achieving society; Vol. 92051, Simon and Schuster: New York, 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Vroom, V.H. Work and motivation.; Wiley: New York, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Rotter, J.B. Generalized expectancies for internal versus external control of reinforcement. Psychological monographs: General and applied 1966, 80, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandura, A. Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological review 1977, 84, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solomon, L.J.; Rothblum, E.D. Academic procrastination: frequency and cognitive-behavioral correlates. Journal of counseling psychology 1984, 31, 503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carver, C.S.; Scheier, M.F. Origins and functions of positive and negative affect: a control-process view. Psychological review 1990, 97, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locke, E.A.; Latham, G.P. A theory of goal setting & task performance.; Prentice-Hall, Inc: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Csikszentmihalyi, M.; Csikzentmihaly, M. Flow: The psychology of optimal experience; Vol. 1990, Harper &, Ed.; Row New York: New York, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumeister, R.F.; Heatherton, T.F. Self-regulation failure: An overview. Psychological inquiry 1996, 7, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loewenstein, G. Out of control: Visceral influences on behavior. Organizational behavior and human decision processes 1996, 65, 272–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tice, D.M.; Baumeister, R.F. Longitudinal study of procrastination, performance, stress, and health: The costs and benefits of dawdling. Psychological science 1997, 8, 454–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Kuhl, J.; Deci, E.L. Nature and autonomy: An organizational view of social and neurobiological aspects of self-regulation in behavior and development. Development and psychopathology 1997, 9, 701–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ariely, D. Predictably irrational: the hidden forces that shape our decisions. Ebook, Revised and.

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. The" what" and" why" of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological inquiry 2000, 11, 227–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, J.R. Procrastination as self-regulation failure of performance: effects of cognitive load, self-awareness, and time limits on ‘working best under pressure’. European journal of Personality 2001, 15, 391–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heine, S.J. Self as cultural product: An examination of East Asian and North American selves. Journal of personality 2001, 69, 881–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eccles, J.S.; Wigfield, A. Motivational beliefs, values, and goals. Annual review of psychology 2002, 53, 109–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baumeister, R.F. Ego depletion and self-control failure: An energy model of the self’s executive function. Self and identity 2002, 1, 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, G. The cultural grounding of personal relationship: enemyship in North American and West African worlds. Journal of personality and social psychology 2005, 88, 948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duckworth, A.L.; Peterson, C.; Matthews, M.D.; Kelly, D.R. Grit: perseverance and passion for long-term goals. Journal of personality and social psychology 2007, 92, 1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steel, P. The nature of procrastination: a meta-analytic and theoretical review of quintessential self-regulatory failure. Psychological bulletin 2007, 133, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schraw, G.; Wadkins, T.; Olafson, L. Doing the things we do: a grounded theory of academic procrastination. Journal of Educational psychology 2007, 99, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berridge, K.C. The debate over dopamine’s role in reward: the case for incentive salience. Psychopharmacology 2007, 191, 391–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thaler, R.; Sunstein, C. Nudge: Improving decisions about health, wealth and happiness. In Proceedings of the Amsterdam Law Forum; 2008, HeinOnline: Online. HeinOnline; p. 89.

- Botvinick, M.M. Hierarchical models of behavior and prefrontal function. Trends in cognitive sciences 2008, 12, 201–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pessoa, L. How do emotion and motivation direct executive control? Trends in cognitive sciences 2009, 13, 160–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pychyl, T.A. The procrastinator’s digest: A concise guide to solving the procrastination puzzle; Xlibris Corporation: Bloomington, IN, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Nisbett, R. The Geography of Thought: How Asians and Westerners Think Differently... and; Simon and Schuster: New York, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Kahneman, D. Thinking, fast and slow. Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

- Gelfand, M.J.; Raver, J.L.; Nishii, L.; Leslie, L.M.; Lun, J.; Lim, B.C.; Duan, L.; Almaliach, A.; Ang, S.; Arnadottir, J.; et al. Differences between tight and loose cultures: A 33-nation study. science 2011, 332, 1100–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holroyd, C.B.; Yeung, N. Motivation of extended behaviors by anterior cingulate cortex. Trends in cognitive sciences 2012, 16, 122–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kool, W.; Botvinick, M. The intrinsic cost of cognitive control. Behavioral and Brain Sciences 2013, 36, 697–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurzban, R.; Duckworth, A.; Kable, J.W.; Myers, J. An opportunity cost model of subjective effort and task performance. Behavioral and brain sciences 2013, 36, 661–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior; Springer Science & Business Media: New York, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Dweck, C.S. Self-theories: Their role in motivation, personality, and development; Psychology press: Philadelphia, PA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Mischel, W. The marshmallow test: Understanding self-control and how to master it; Random House: New York, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Inzlicht, M.; Schmeichel, B.J.; Macrae, C.N. Why self-control seems (but may not be) limited. Trends in cognitive sciences 2014, 18, 127–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Markus, H.R.; Kitayama, S. Culture and the self: Implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation. In College student development and academic life; Routledge: London, 2014; pp. 264–293. [Google Scholar]

- Sirois, F.M. Procrastination and stress: Exploring the role of self-compassion. Self and Identity 2014, 13, 128–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shadmehr, R.; Huang, H.J.; Ahmed, A.A. A representation of effort in decision-making and motor control. Current biology 2016, 26, 1929–1934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shenhav, A.; Musslick, S.; Lieder, F.; Kool, W.; Griffiths, T.L.; Cohen, J.D.; Botvinick, M.M. Toward a rational and mechanistic account of mental effort. Annual review of neuroscience 2017, 40, 99–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gollwitzer, P.M. The goal concept: A helpful tool for theory development and testing in motivation science. Motivation Science 2018, 4, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westbrook, A.; Van Den Bosch, R.; Määttä, J.I.; Hofmans, L.; Papadopetraki, D.; Cools, R.; Frank, M.J. Dopamine promotes cognitive effort by biasing the benefits versus costs of cognitive work. Science 2020, 367, 1362–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lieder, F.; Griffiths, T.L. Resource-rational analysis: Understanding human cognition as the optimal use of limited computational resources. Behavioral and brain sciences 2020, 43, e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lagun, N. Lagun’s law and the foundations of cognitive drive architecture: A first principles theory of effort and performance. International Journal of Science and Research Archive 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagun, N. Cognitive Thermostat Theory (CTT): A Control-Theoretic Model of Drive Ignition in Cognitive Drive Architecture (CDA). PsyArXiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagun, N. Latent Task Architecture: Modeling Cognitive Readiness Under Unresolved Intentions. Research Square 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagun, N. Switch ON: A User’s Guide To Your Mind’s Drive Engine; Nikesh Lagun: Kathmandu, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Lagun, N. Cognitive Drive Architecture: Derivation and Validation of Lagun’s Law for Modeling Volitional Effort. Preprints 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).