1. Introduction

Emerging progress in metagenomic sequencing has improved microbiome research, with both shotgun and 16S rRNA sequencing playing vital roles. Shotgun metagenomic sequencing enables unbiased, high-resolution profiling of microbial communities, capturing taxonomic and functional diversity across the domines of microbiome. In contrast to 16S rRNA gene sequencing, shotgun metagenomic sequencing offers enhanced taxonomic resolution at the species and strain levels, along with the ability to profile functional gene content, thereby representing the method of choice for in-depth characterization of host-associated microbiomes and investigation of their contributions to human health and disease [

1]. The convoluted association between diet and human health has been a subject of extensive research, with recent focus shifting towards understanding how dietary habits influence the composition and functionality of the microorganisms in gut [

2]. The gut microbiome, a multifaceted ecology of microorganisms in the gastrointestinal tract, plays a critical role in maintaining host health by modulating various physiological processes. Emerging evidence suggests that dietary patterns profoundly influence the gut microbiome composition, which, in turn, impacts the host's susceptibility to diseases and overall well-being [3-5].

The human gut is a shelter for trillions of microorganisms, which include bacteria, viruses, fungi, and archaea [

5]. Nutritional components of the diet serve as substrates for microbial metabolism, persuading the abundance and diversity of gut microbial communities. For instance, diets rich in fiber promote the growth of beneficial gut bacteria, like Bifidobacterium sp. and Lactobacillus sp., whereas high-fat diets have been associated with a reduction in beneficial microorganisms or keystone species (microorganisms helping in maintaining the gut microbiome ecosystem). Moreover, high-fat diets may lead to an increase in pathogenic bacteria in gut, specifically belonging to the phylum Firmicutes (

Ruminococcus sp., Streptococcus sp.) [6, 7].

The raising evidence suggests that modifications in gut microbiome composition due to nutritional factors can influence the growth and development of various chronic diseases [8, 9]. Chronic conditions such as obesity, metabolic syndrome, inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD), cancer and cardiovascular diseases have been associated with dysbiosis, which refers to an imbalance or disruption in the composition and metabolic capacity of the gut microbiota [

10,

11]. For instance, consumption of modern lifestyle diet, characterized by high fat, sugar, and processed foods, has been associated with an increased abundance of pathogenic species causing various diseases. This reflects an increased relative abundance of pathogens or microbial biomarkers associated with obesity, inflammation, cardiovascular disease, and insulin resistance—key risk factors contributing to chronic disease development [12, 13].

Modification of gut microbiome by dietetic changes opens avenues for targeted dietary interventions to promote health and prevent diseases. Dietary modifications, such as increasing fiber intake, consuming fermented foods rich in probiotics, and adopting a diet rich in fruits, vegetables, and whole grains, have been shown to positively impact gut microbiome composition and function [

14]. These dietary interventions have been associated with reduced inflammation, improved metabolic health, and enhanced immune function, highlighting the potential of diet-microbiome interactions in promoting overall well-being [15, 16]. Abnormal changes in the gut microbiome (dysbiosis) impacts host health and leads to physical and mental health problems. Moreover, databases like GMrepo focus on curated human gut microbiome data, emphasizing disease biomarkers and facilitating cross-dataset comparisons to identify consistent and non-consistent disease-associated microbial markers across various health conditions [

17]. Additionally, specific gut bacteria like

Clostridium symbiosum,

Ruminococcus gnavus,

Ruminococcus torques, Fusobacterium nucleatum and

Clostridium colicanis have been proposed as indicative markers in diseases such as obesity, colorectal cancer and gastric cancer, highlighting the significance of gut microbial markers in disease diagnosis and understanding the relationship between gut microbiota and human health [

18]. These published reports also highlight that the manipulation of the gut microbiome through the use of probiotics, prebiotics, and synbiotics can help restore the balance of the microbiota and promote health [19-21].

Thus, in the present study, we delve into the current body of evidence elucidating the impact of diet on the gut microbiome, disease microbial markers, and health outcomes. The growing body of evidence from epidemiological studies, clinical trials, and mechanistic investigations, we aim to provide insights into the complex interplay between diet, gut microbiome, and human health. This is the first study comparing gut microbiota of human subjects following different diet and it’s association with different diseases i.e cancer or obesity. Understanding these relationships is essential for developing personalized dietary strategies aimed at optimizing gut microbiome composition and mitigating the risk of chronic diseases.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample data collection and processing

This research was conducted in strict compliance with ethical guidelines of the Health Research Ethics Board of Alberta (HREBA.CHC-25-0013). Informed consent was duly obtained from all participants, with robust measures implemented to ensure the protection of their privacy and confidentiality. As part of the BioGut program, clinical samples were received at the Genomics Facility of BioAro Inc. for next generation sequencing (NGS) and results were archived in BioAro Inc data repository with anthropometric measures and medical history of the participants. In this retrospective study data were collected from the repository of BioAro Inc. for 73 participants with different age groups ranging from 10-80 years. Additionally, for the comparison 20 healthy subjects’ gut microbiome data was obtained from Human microbiome project (HMP) site and added to the analysis as a control group.

Stool samples for Bio-Gut analysis from participants were received, at the BioAro Inc. genomic facility, and then frozen for storage at -80°C for further processing. Microbial genomic DNA was extracted from samples using the Zymo BIOMICS DNA Miniprep Kit (Zymo Research, Cat. No. D4300) following the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, the protocol involved cell lysis using enzymatic digestion and bead beating, followed by DNA purification using spin columns and washes. Purified DNA was eluted in DNase-free water.

2.2. Library construction and sequencing

The extracted DNA from each sample was quantified using Qubit fluorometer [

22] according to the manufacturer's instructions. Dilute each DNA sample to a pre-determined concentration (e.g., 10 ng/µL) using TE buffer to ensure equal representation in the library. Ligate sequencing adapters containing MGI Rapid sequencing flow cell complementary sequences and unique barcode sequences to the fragmented DNA ends using T4 DNA Ligase in MGIEasy FS DNA library prep kit according to the manufacturer's protocol. These adapters allow for library attachment to the sequencing flow cell and sample identification during sequencing, respectively. The prepared library was quantified using size-selection methods (e.g., gel electrophoresis or magnetic beads) and Qubit fluorometer [

22]. This ensures sequencing of the desired library fragments. Additionally, the purified library was quantified using a fluorometric method and assessing the fragment size distribution using an automated capillary electrophoresis system like Agilent Tapestation [

23]. This step ensures quality and quantity of library for further sequencing process and verifies fragment size (350-500 bp) suitability for the MGI sequencing platform.

Further, the samples from library were pooled together by combining the aliquots of normalized library DNA from all microbiome samples into a single tube. The volume of each aliquot should be proportional to the desired representation of each sample in the final sequencing data. The circular single-stranded DNA molecules were prepared by enzymatic circularization. Following the manufacturer's instructions, this circularization method was completed using commercially available MGIEasy circularization module reaction kits. The circularized DNA were diluted to the recommended concentration for DNA Nano Ball (DNB) preparation and loaded onto the DNBSeq-G400RS Sequencing Flow Cell by following the manufacturer's instructions. Finally, the paired-end shotgun sequencing was performed using sequencing platform (MGI DNBSEQ-G400) to obtain reads from both ends of the DNA fragments. Shotgun sequencing was preferred over 16S RNA sequencing as it enables to detect the variety of microorganisms at species level. The sequencing procedure was regulated by the addition of positive and negative controls in each run.

Concurrently, 16S sequencing and shotgun metagenomic sequencing are most extensively utilized methodologies for taxonomical profiling of microorganisms which offer diverse molecular and analytical advantages. The 16S sequencing depends on the amplification of homologous regions of 16S ribosomal RNA gene, for genus level identification of microbial taxonomy [

24]. On the other hand, shotgun metagenomic sequencing amplifies every DNA present in the sample, including host genome and identifies species and strain-level microbial taxonomy. It also aids in functional annotation of genes involved in antibiotic resistance, virulence and other metabolic processes [25, 26].

2.3. Taxonomy classification

The raw reads were processed through the in-house bioinformatics pipeline PanOmiQ developed at BioAro Inc. It utilized databases, which are rapidly curated and comprehensive platform for taxonomy identification and classification [

27]. It has more than 27,000 microbial genomic DNA sequences for rapid identification. Initially, the raw reads were analyzed for its quality, low quality reads and adaptors were trimmed. Further, Host DNA and rRNA were removed from the sequences by assembling with human reference genome. The taxonomy classification and species identification were performed for species identification.

2.4. Statistical analysis

The tertiary analysis using R statistical software package was utilized to perform statistical analysis that explored potential variations in microbial community composition between the different patient groups. Non-parametric Fisher’s exact test was performed to calculate p<0.05 with 95% confidence interval.

3. Results and Discussions

This section may be divided by subheadings. It should provide a concise and precise description of the experimental results, their interpretation, as well as the experimental conclusions that can be drawn.

Gut microbiome, as a characteristic human-associated niche, can be comprehensively analyzed using shotgun metagenomic sequencing to elucidate the host–microbial interactions. Effective computational methods aid in filtering host DNA contamination and enable accurate downstream analyses [

28]. Despite the cost-efficiency of 16S sequencing, which makes it ideal for broad surveys and ecological comparisons, shotgun metagenomics delivers a more multi-faceted and exhaustive analysis of microbial communities, including functional characterization and species- or strain-level resolution [

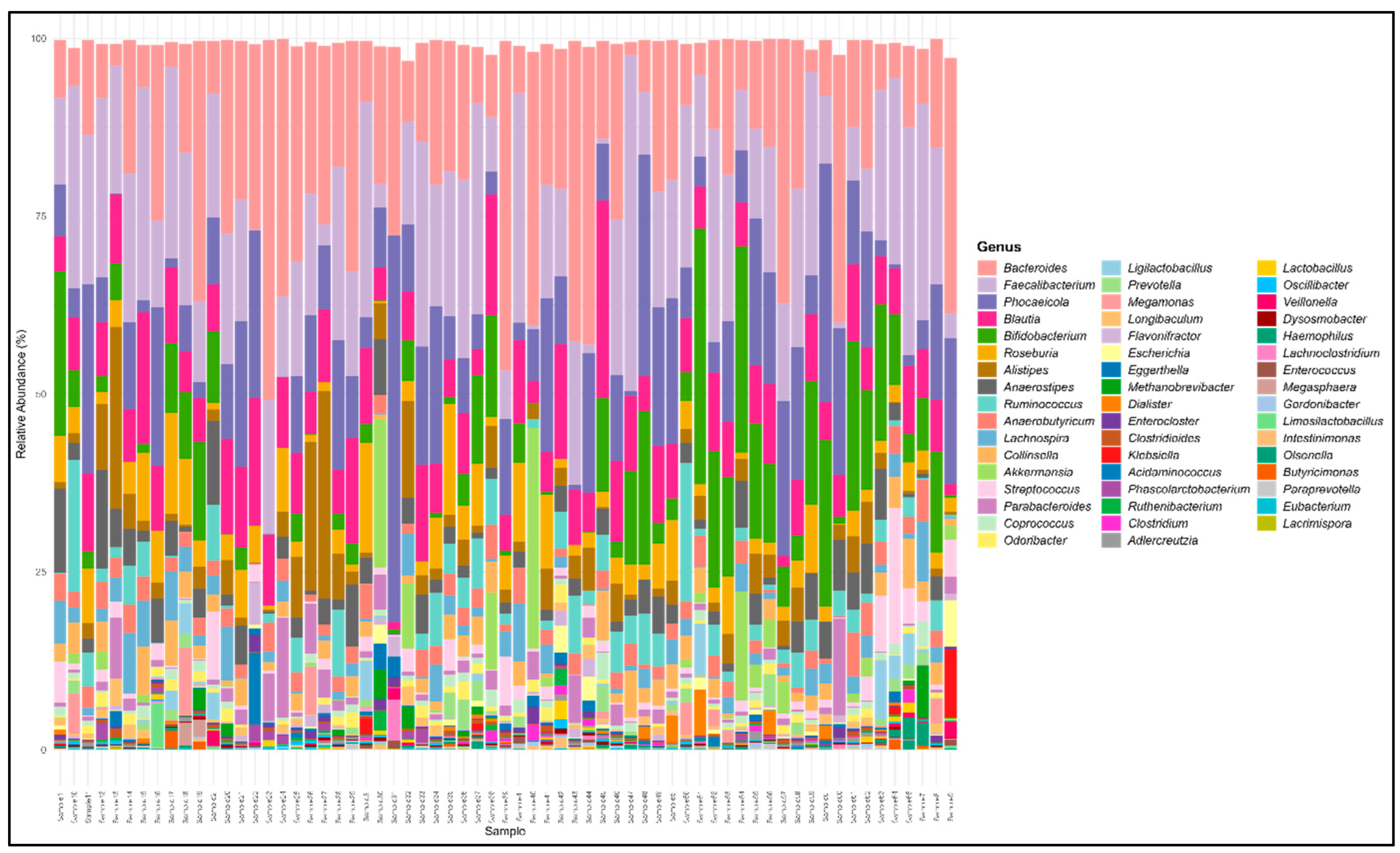

29]. Our shotgun metagenomic sequencing analysis found the bacterial fraction of different gut microbiome samples. The clean reads were mapped to the human reference genome for host sequence removal before taxonomic classification. The taxonomical composition and relative abundance of gut microbiota of plant and meat eaters has varied significantly. The gut microbiome of healthy controls, plant and meat-based diet consumers were dominated by four phyla Bacteroidetes, Firmicutes, Actinobacteria and Proteobacteria. The genus level distribution of the species is given in

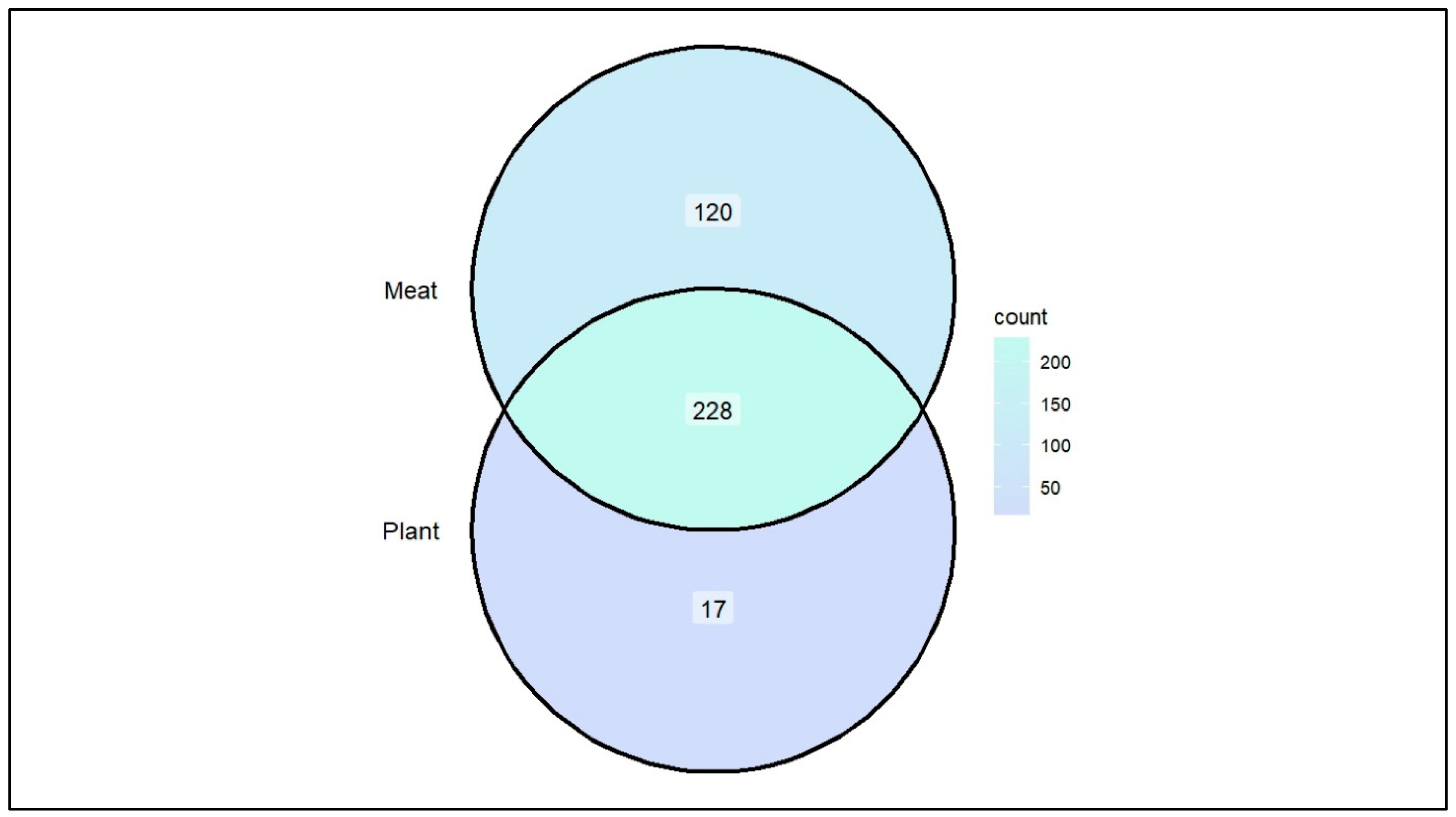

Figure 1. The species level comparison of Plant diet (PD) and Meat diet (MD) consumers reveals an increased intestinal bacteria load in MD compared to PD consumers. There were 228 common bacterial species found in both groups, whereas 17 and 120 unique bacterial species were observed only in PD and MD respectively [

Figure 2]. Some of these unique species are considered as opportunistic pathogens such as Actinomyces spp., and Corynebacterium spp. Our analysis revealed that MD consumer group had apparently a higher number of species than that of the PD group. Additionally, MD consumer group’s gut samples indicated that the pathogenic species such as

Ruminococcus torques (>3.34%),

Ruminococcus gnavus (>2.22%) and

Clostridium symbiosum (>1.87%) were relatively higher in abundance than PD.

3.1. Opportunistic Pathogen Species and Disease risk.

Based on the anthropometric measurements of participants, Body Mass Index (BMI) were calculated. Samples were categorized into normal weight, moderately obese, severely underweight and severely obese using BMI. On the basis of the healthy history of the participants, samples were also categorized into cancer and normal. The species level comparison was also analyzed for different types of obese and normal samples which revealed that 54 microbial species were commonly found in all the categories. Total 53, 27, 26 and 3 unique microorganisms were detected in normal, moderately obese, severely obese and severely underweight samples respectively [

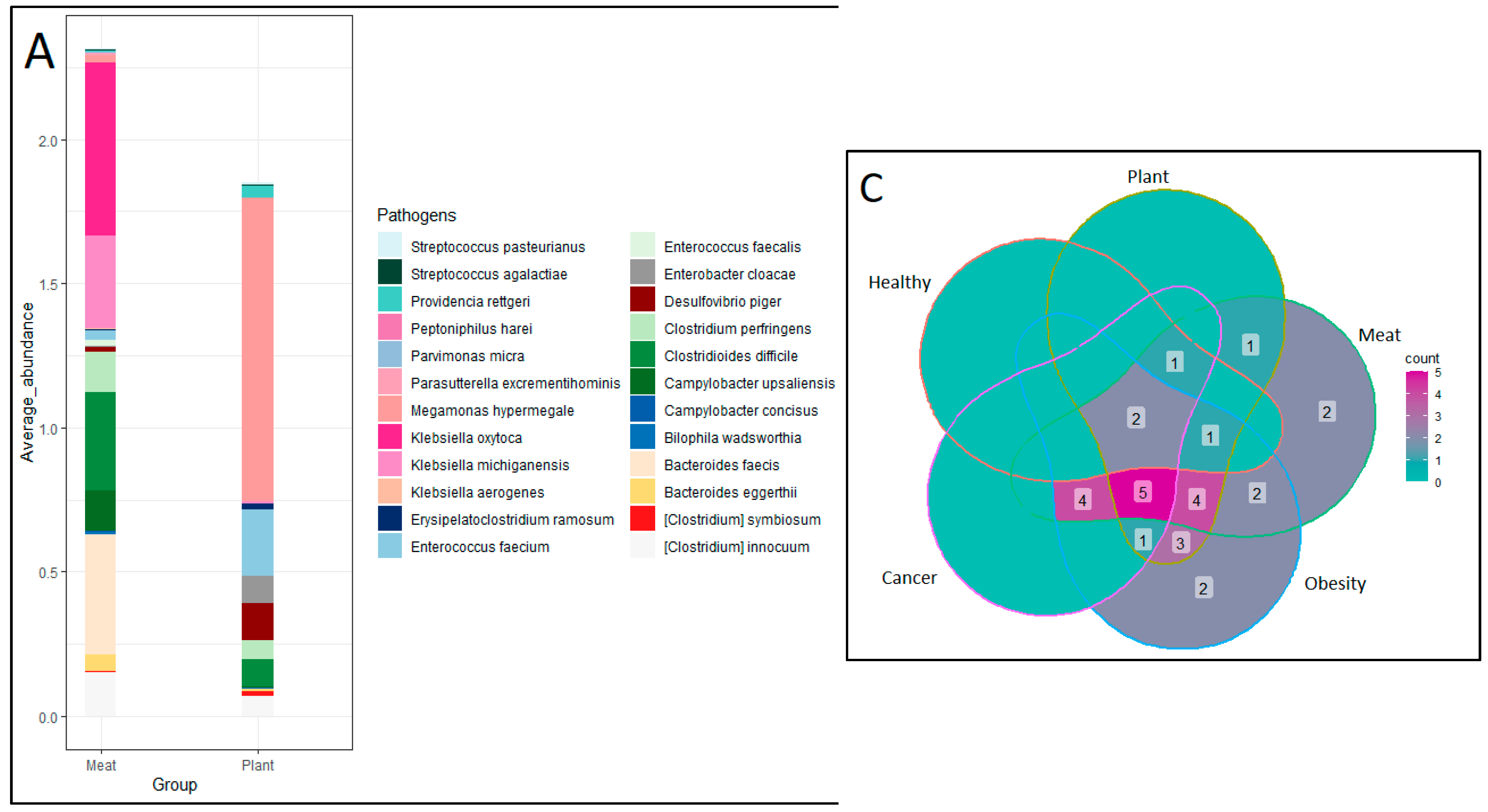

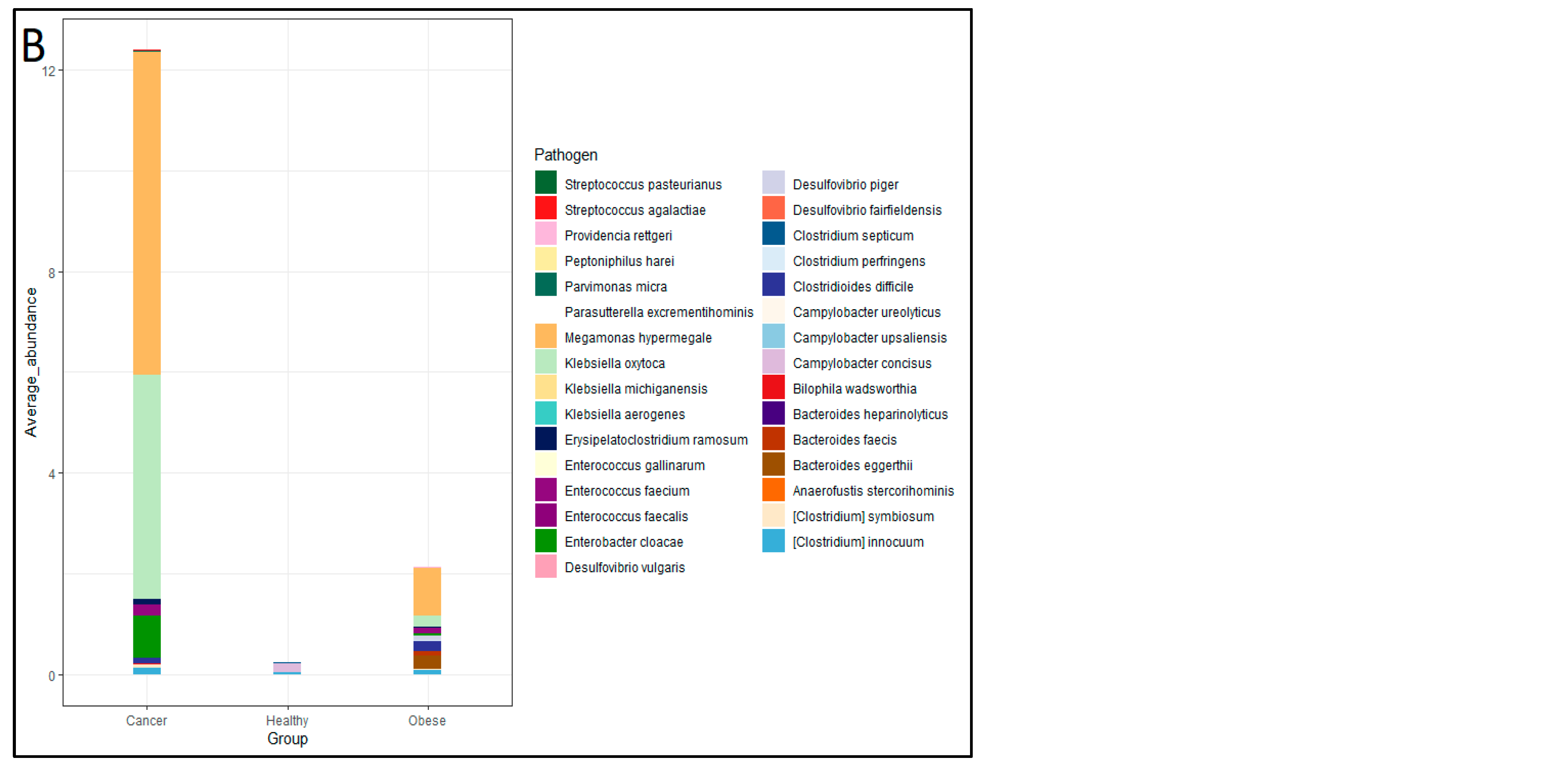

Figure 3]. The fisher exact test performed using R software with 95% confidence interval for PD and MD group pathogens revealed a statistically significant difference (p = 0.02) in both the number and relative abundance of pathogens. between the two categories. These pathogenic species exhibited a relative abundance ranging from 0%–0.04% in Healthy subjects, 0%–0.07% in PD subjects, and notably higher levels of 0.006%–0.6% in MD subjects. The presence of pathogens was compared between three groups, healthy control, PD and MD consumers, alongside pathogen comparison was also carried out between healthy control, obese and cancer patients. It is observed that 24 pathogens were found in obese patients followed by MD (22 pathogens), PD (17 pathogens), Cancer subjects (13 pathogens) and healthy control subjects (5 pathogens) [

Figure 4].

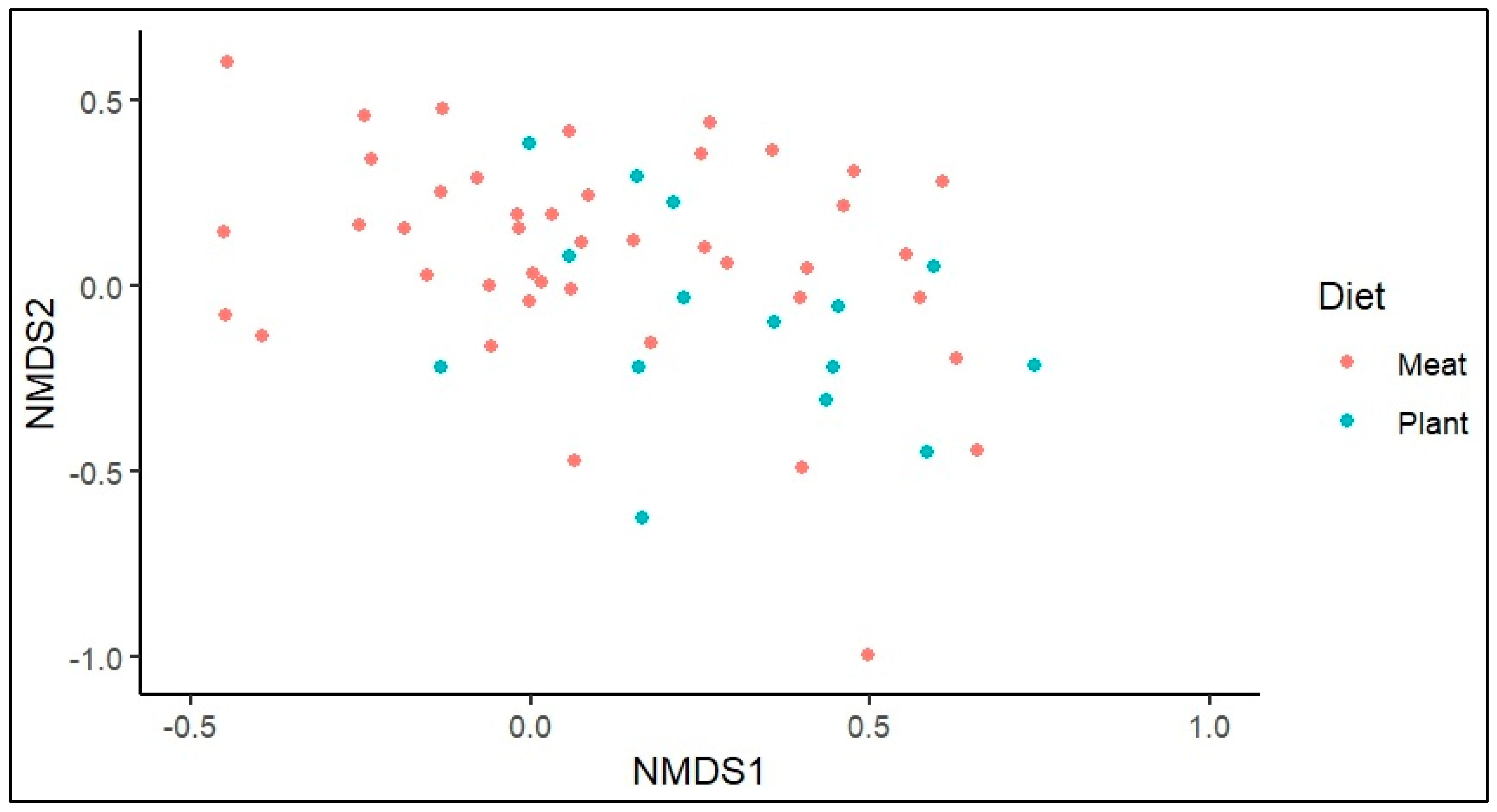

Non-metric multi-dimensional scaling analysis was performed using Phyloseq package in R software [

30].

Figure 5 represents the Bray-Curtis dissimilarity between samples, in which most of the MD group gut samples fall above 0.2 indicates the differences in species abundance compared with PD with p value of (0.005%). It is also observed that a higher abundance of

R. gnavus (>2.22%) and R. torques (>3.34%) was observed in most of MD samples.

R. gnavus is one of the microbial markers for various diseases such as cardiovascular disease (CVD), obesity, IBD and mental health [

31]. R. torques along with

R. gnavus contributes to the IBD progression. Pathogens like

C. symbiosum and

Clostridium innoccum are common in both PD and MD group but not found in healthy subjects. Among obese patients, a reduced abundance of the species

Akkermansia muciniphila was observed (0% - 0.15%). The relative abundance of Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS) microbial markers such as

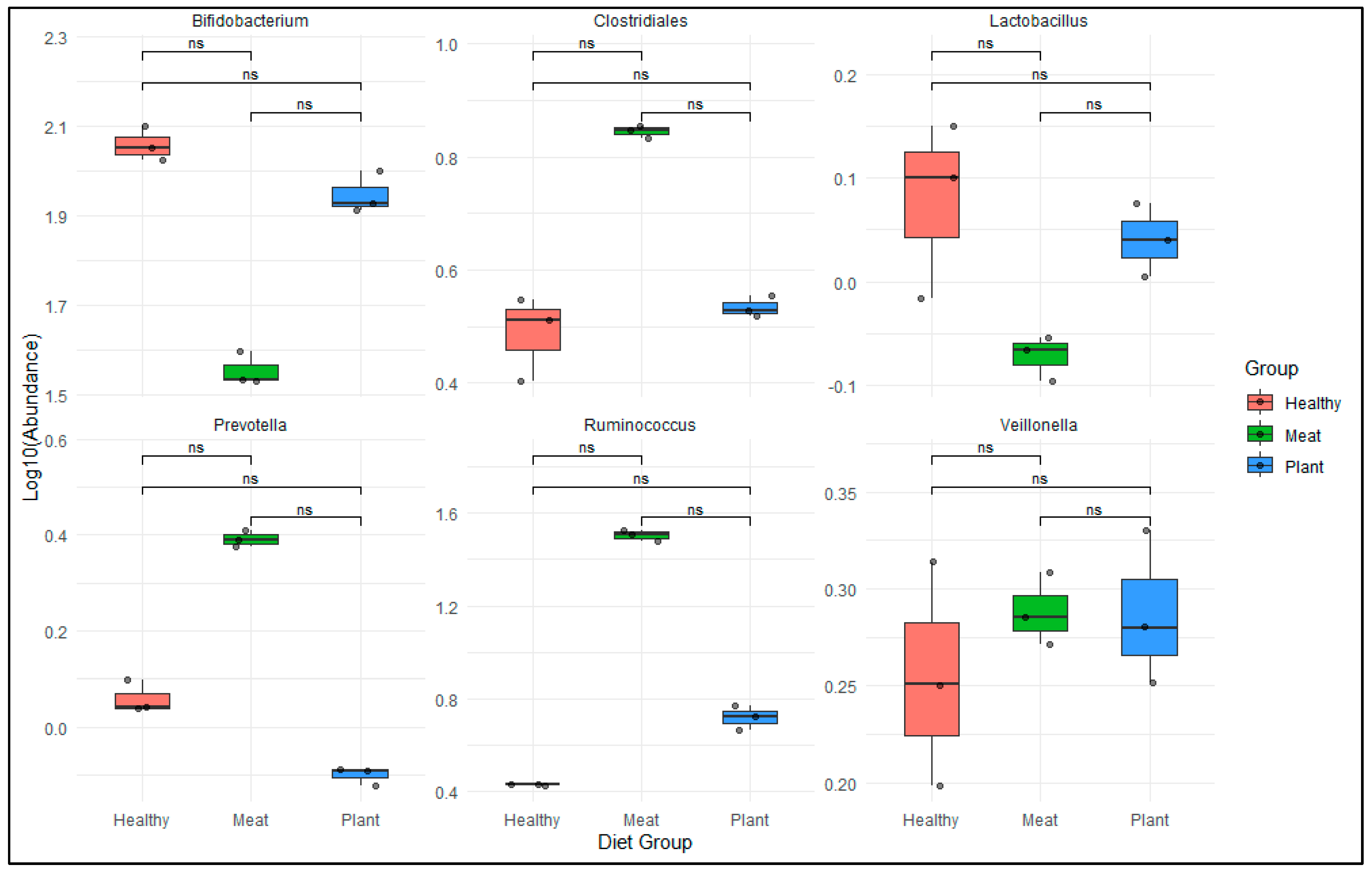

Bifidobacterium spp., Lactobacillus spp., Veillonella spp., Ruminococcus spp., Clostridiales spp., and

Prevotella spp. reveals a significant difference (non-significant in similarity) between MD, PD and healthy subjects [

Figure 6]. These species help in improving insulin sensitivity and regulate glucose hemostasis metabolism [32, 33]. The Wilcoxon non-parametric test was employed to evaluate the statistically non-significant variation in the abundance of IBS-associated microbial markers between MD and PD consumer groups. The study also revealed that the relative abundance of beneficial bacterial family such as

Lactobacillaceae (PD: 0.5% - 1.46%; MD: 0% - 0.02%) and

Bifidobacteriaceae (PD: 2.97% - 14.43%; MD: 0.027% - 1.31%) was reduced, whereas

Prevotella spp., Ruminococcus spp. and

Clostridium spp. were increased in maximum number of MD samples. Both these beneficial species have anti-inflammatory properties and help in maintaining intestinal metabolic health.

Lactobacillus spp. helps in inhibiting the growth of certain pathogens such as

Staphylococcus aureus, Escherichia coli, Clostridium difficile upon others [

34].

Bifidobacterium spp. facilitates fiber digestion and produces saturated fatty acids and B vitamins. Lower abundance of these species might lead to diseases like gastrointestinal infections, gastric cancer, colon neoplasms [35, 36]. Moreover, the lower presence of probiotic species belonging to genus

Lactobacillaceae has been linked with increased anxiety and altered cognitive behaviors [

37]. The present analysis also detected the bacteria belonging to genera

Bacteroides spp., Roseburia spp., Eubacterium spp., and

Methanobrevibacter spp. in the PD samples. The presence of aforementioned bacteria was due to consumption of foods like pulses -beans and these might be responsible for somatic pain [

38].

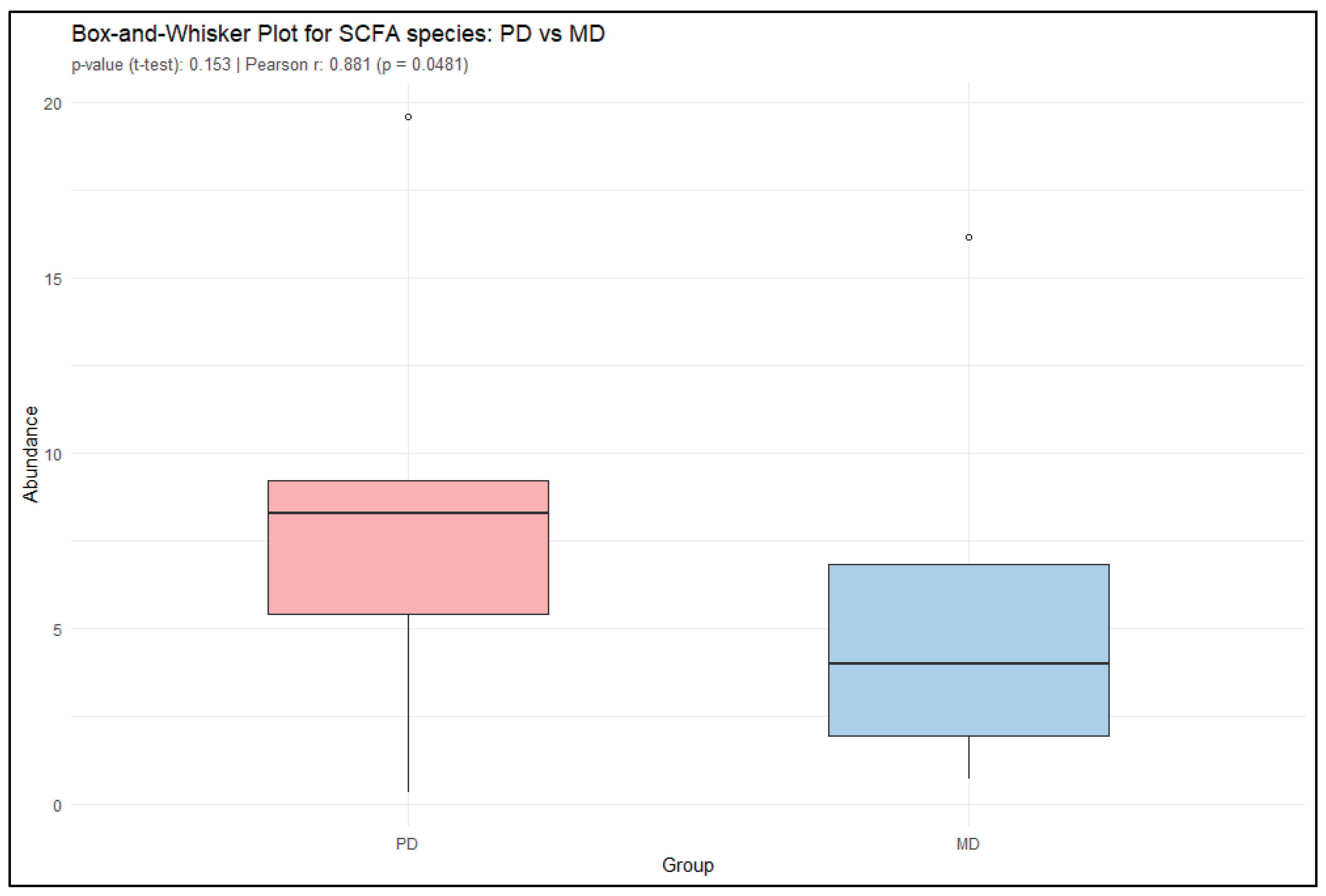

3.2. SCFA Production

Furthermore, short-chain fatty acid (SCFA)-producing bacteria were analyzed in both PD and MD samples. Genera known for SCFA production such as

Faecalibacterium, Bifidobacterium, Coprococcus, Roseburia, and Akkermansia play a crucial role in maintaining gut health and overall metabolic balance. These bacteria ferment dietary fibers and resistant starches in the colon to produce SCFAs such as acetate, propionate, and butyrate. They also influence glucose and lipid metabolism, support gut-brain signaling, and play a protective role against obesity, type 2 diabetes, colorectal cancer, and other chronic diseases. The presence and abundance of SCFA-producing bacteria are therefore considered beneficial markers of a healthy gut microbiome and are often associated with reduced risk of metabolic and inflammatory disorder. A paired t-test comparing the relative abundance of these SCFA producing bacteria in PD and MD groups yielded a t-value of 1.76 (df = 4, p = 0.153), indicating that the observed difference in mean abundance was not statistically significant at the 0.05 level. The 95% confidence interval for the mean difference ranged from -1.51 to 6.77, suggesting substantial variability and insufficient evidence to reject the null hypothesis. However, Pearson correlation analysis revealed a significantly higher abundance of SCFA-producing bacteria in PD samples compared to MD, with a correlation coefficient of r = 0.8814 (p = 0.04812) and a 95% confidence interval [

Figure 7].

4. Conclusions

In summary, the pilot study investigated the gut samples of the subjects suffering from different disease and following varying dietary patterns by using advanced shotgun metagenomic sequencing analysis. Taxonomical classification and relative abundance calculation was performed using PanOmiQ software. The secondary analysis revealed that more than 100 unique species were detected only in the MD samples when compared with PD and healthy subjects. Among those unique species, 22 were pathogenic microorganism. Additionally, the abundance of pathogenic microorganisms i.e R. gnavus and R. torques were higher in MD samples in comparison to other groups. We also observed the presence of C. symbiosum and C. innoccum in maximum number of the samples. These species were found to be more abundant in samples from cancer patients and obese people. Overall, this is the first study depicting that dietary factors influence the presence of opportunistic pathogens in gut microbiome, and might leads to diseases i.e. cancer and obesity. Pathogenic microorganisms are less common when a plant-based diet is consumed. The study provides insights for personalized dietary practice based on their health condition.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.B, M.B.T and K.D.; Sample Extraction, A.K., R.C. and P.B.; Sequencing M.B.T, K.D and R.C.; Data curation, P.B.; Script generation F.D.; Data Analysis, P.B., F.D. and S.V.; original draft preparation, P.B.; reviewing and editing, K.D. and M.BT.; supervision, M.BT., R.K., R.S., C.H. and An.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

Authors acknowledge patients and volunteers who participated in the study and BioAro Inc. for providing laboratory and computational facility for performing the study.

Conflicts of Interest

This research project is carried out in the facility of BioAro Inc, Calgary, Alberta, Canada, R.C., A.K., M.BT., R.S. and An.K. are employees of BioAro Inc. whereas P.B is working as a MITACS Fellow with University of Calgary and K.D is a postdoctoral research fellow with MITACS Fellowship at University of Lethbridge. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as potential conflicts of interest.

References

- Knight, R. , Vrbanac, A., Taylor, B.C., Aksenov, A., Callewaert, C., Debelius, J., Gonzalez, A., Kosciolek, T., McCall, L.I., McDonald, D., Melnik, A.V., Morton, J.T., Navas, J., Quinn, R.A., Sanders, J.G., Swafford, A.D., Thompson, L.R., Tripathi, A., Xu, Z.Z., Zaneveld, J.R., … Dorrestein, P.C. Best practices for analysing microbiomes. Nature reviews. Microbiology 2018, 16, 410–422. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sheflin, A.M.; Melby, C.L.; Carbonero, F.; Weir, T.L. Linking Dietary Patterns with Gut Microbial Composition and Function. Gut Microbes 2016, 8, 113–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adithya, K.K.; Rajeev, R.; Selvin, J.; Seghal Kiran, G. Dietary Influence on the Dynamics of the Human Gut Microbiome: Prospective Implications in Interventional Therapies. ACS Food Science & Technology 2021, 1, 717–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redondo-Useros, N.; Nova, E.; González-Zancada, N.; Díaz, L.E.; Gómez-Martínez, S.; Marcos, A. Microbiota and Lifestyle: A Special Focus on Diet. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rinninella, E.; Tohumcu, E.; Raoul, P.; Fiorani, M.; Cintoni, M.; Mele, M.C.; Cammarota, G.; Gasbarrini, A.; Ianiro, G. The Role of Diet in Shaping Human Gut Microbiota. Best Practice & Research Clinical Gastroenterology 2023, 62-63, 101828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- David, L.A.; Maurice, C.F.; Carmody, R.N.; Gootenberg, D.B.; Button, J.E.; Wolfe, B.E.; Ling, A.V.; Devlin, A.S.; Varma, Y.; Fischbach, M.A.; Biddinger, S.B.; Dutton, R.J.; Turnbaugh, P.J. Diet Rapidly and Reproducibly Alters the Human Gut Microbiome. Nature 2013, 505, 559–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turnbaugh, P.J.; Bäckhed, F.; Fulton, L.; Gordon, J.I. Diet-Induced Obesity Is Linked to Marked but Reversible Alterations in the Mouse Distal Gut Microbiome. Cell Host & Microbe 2008, 3, 213–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noce, A.; Marrone, G.; Di Daniele, F.; Ottaviani, E.; Wilson Jones, G.; Bernini, R.; Romani, A.; Rovella, V. Impact of Gut Microbiota Composition on Onset and Progression of Chronic Non-Communicable Diseases. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Q.; Liang, Q.; Balakrishnan, B.; Belobrajdic, D.; Feng, Q.-J.; Zhang, W. Role of Dietary Nutrients in the Modulation of Gut Microbiota: A Narrative Review. Nutrients 2020, 12, 381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horn, J.; Mayer, D.E.; Chen, S.; Mayer, E.A. Role of Diet and Its Effects on the Gut Microbiome in the Pathophysiology of Mental Disorders. Translational Psychiatry 2022, 12, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manor, O.; Dai, C.L.; Kornilov, S.A.; Smith, B.; Price, N.D.; Lovejoy, J.C.; Gibbons, S.M.; Magis, A.T. Health and Disease Markers Correlate with Gut Microbiome Composition across Thousands of People. Nature Communications 2020, 11, 5206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Keefe, S.J.D.; Li, J.V.; Lahti, L.; Ou, J.; Carbonero, F.; Mohammed, K.; Posma, J.M.; Kinross, J.; Wahl, E.; Ruder, E.; Vipperla, K.; Naidoo, V.; Mtshali, L.; Tims, S.; Puylaert, P.G.B.; DeLany, J.; Krasinskas, A.; Benefiel, A.C.; Kaseb, H.O.; Newton, K. Fat, Fibre and Cancer Risk in African Americans and Rural Africans. Nature Communications 2015, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, R.K.; Chang, H.-W.; Yan, D.; Lee, K.M.; Ucmak, D.; Wong, K.; Abrouk, M.; Farahnik, B.; Nakamura, M.; Zhu, T.H.; Bhutani, T.; Liao, W. Influence of Diet on the Gut Microbiome and Implications for Human Health. Journal of Translational Medicine 2017, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, P. Influence of Foods and Nutrition on the Gut Microbiome and Implications for Intestinal Health. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2022, 23, 9588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sonnenburg, J.L.; Sonnenburg, E.D. Vulnerability of the Industrialized Microbiota. Science 2019, 366, eaaw9255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Filippis, F.; Pellegrini, N.; Vannini, L.; Jeffery, I.B.; La Storia, A.; Laghi, L.; Serrazanetti, D.I.; Di Cagno, R.; Ferrocino, I.; Lazzi, C.; Turroni, S.; Cocolin, L.; Brigidi, P.; Neviani, E.; Gobbetti, M.; O’Toole, P.W.; Ercolini, D. High-Level Adherence to a Mediterranean Diet Beneficially Impacts the Gut Microbiota and Associated Metabolome. Gut 2015, 65, 1812–1821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, D.; Zhu, J.; Sun, C.; Li, M.; Liu, J.; Wu, S.; Ning, K.; He, L.; Zhao, X.-M.; Chen, W.-H. GMrepo V2: A Curated Human Gut Microbiome Database with Special Focus on Disease Markers and Cross-Dataset Comparison. Nucleic Acids Research 2021, 50, D777–D784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Afzaal, M.; Saeed, F.; Shah, Y.A.; Hussain, M.; Rabail, R.; Socol, C.T.; Hassoun, A.; Pateiro, M.; Lorenzo, J.M.; Rusu, A.V.; Aadil, R.M. Human Gut Microbiota in Health and Disease: Unveiling the Relationship. Frontiers in Microbiology 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zuo, T.; Ng, S.C. The Gut Microbiota in the Pathogenesis and Therapeutics of Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Frontiers in Microbiology 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vyas, U.; Ranganathan, N. Probiotics, Prebiotics, and Synbiotics: Gut and Beyond. Gastroenterology Research and Practice 2012, 2012, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Silva, T.F.; Casarotti, S.N.; de Oliveira, G.L.V.; Penna, A.L.B. The Impact of Probiotics, Prebiotics, and Synbiotics on the Biochemical, Clinical, and Immunological Markers, as Well as on the Gut Microbiota of Obese Hosts. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition, 2020, 61, 337–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robin, J.D.; Ludlow, A.T.; LaRanger, R.; Wright, W.E.; Shay, J.W. Comparison of DNA Quantification Methods for next Generation Sequencing. Scientific Reports 2016, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inche, A.; Gassmann, M.; Arunkumar Padmanaban; Ruediger Salowsky. High-Throughput DNA Sample QC Using the Agilent 2200 Tapestation System. Journal of biomolecular techniques 2013, 24. [Google Scholar]

- Caporaso, J.G.; Lauber, C.L.; Walters, W.A. , Berg-Lyons, D.; Lozupone, C.A.; Turnbaugh, P.J.; Fierer, N.; Knight, R. Global patterns of 16S rRNA diversity at a depth of millions of sequences per sample. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 2011, 108 (Supplement 1), 4516–4522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quince, C.; Walker, A.W.; Simpson, J.T.; Loman, N.J.; Segata, N. Shotgun metagenomics, from sampling to analysis. Nature Biotechnology, 2017, 35, 833–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knight, R.; Vrbanac, A.; Taylor, B.C.; Aksenov, A.; Callewaert, C.; Debelius, J.; Gonzalez, A.; Kosciolek, T.; McCall, L.-I.; McDonald, D.; Melnik, A.V.; Morton, J.T.; Navas-Molina, J.A.; Sanders, J.G.; Swafford, A.D.; Thompson, L.R.; Tripathi, A.; Xu, Z.Z.; Zaneveld, J.R.; Dorrestein, P.C. Best practices for analysing microbiomes. Nature Reviews Microbiology, 2018, 16, 410–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wood, D.E.; Lu, J.; Langmead, B. Improved Metagenomic Analysis with Kraken 2. Genome Biology 2019, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Jia, H.; Cai, X.; Zhong, H.; Feng, Q.; Sunagawa, S.; Arumugam, M.; Kultima, J.R.; Prifti, E.; Nielsen, T.; Juncker, A.S.; Manichanh, C.; Chen, B.; Zhang, W.; Levenez, F.; Wang, J.; Xu, X.; Xiao, L.; Liang, S.; Bork, P. An integrated catalog of reference genes in the human gut microbiome. Nature Biotechnology, 2021, 32, 834–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franzosa, E.A.; McIver, L.J.; Rahnavard, G.; Thompson, L.R.; Schirmer, M.; Weingart, G.; Lipson, K.S.; Knight, R.; Caporaso, J.G.; Segata, N.; Huttenhower, C. Species-level functional profiling of metagenomes and metatranscriptomes. Nature Methods, 2015, 15, 962–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMurdie, P.J.; Holmes, S. Phyloseq: An R Package for Reproducible Interactive Analysis and Graphics of Microbiome Census Data. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e61217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coletto, E.; Bell, A.; Juge, N.; Emmanuelle Crost. Ruminococcus Gnavus: Friend or Foe for Human Health. Fems Microbiology Reviews 2023, 47. [Google Scholar]

- Abuqwider, J.N.; Mauriello, G.; Altamimi, M. Akkermansia Muciniphila, a New Generation of Beneficial Microbiota in Modulating Obesity: A Systematic Review. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Depommier, C.; Everard, A.; Druart, C.; Plovier, H.; Van Hul, M.; Vieira-Silva, S.; Falony, G.; Raes, J.; Maiter, D.; Delzenne, N.M.; de Barsy, M.; Loumaye, A.; Hermans, M.P.; Thissen, J.-P.; de Vos, W.M.; Cani, P.D. Supplementation with Akkermansia Muciniphila in Overweight and Obese Human Volunteers: A Proof-of-Concept Exploratory Study. Nature Medicine 2019, 25, 1096–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dempsey, E.; Corr, S.C. Lactobacillus Spp. For Gastrointestinal Health: Current and Future Perspectives. Frontiers in Immunology 2022, 13, 840245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gholam Reza Hanifi; Hossein Samadi Kafil; H Tayebi Khosroshahi; Reza Shapouri; Asgharzadeh, M. Bifidobacteriaceae Family Diversity in Gut Microbiota of Patients with Renal Failure. 2021.

- Youssef, O.; Lahti, L.; Kokkola, A.; Karla, T.; Tikkanen, M.; Ehsan, H.; Carpelan-Holmström, M.; Koskensalo, S.; Böhling, T.; Rautelin, H.; Puolakkainen, P.; Knuutila, S.; Sarhadi, V. Stool Microbiota Composition Differs in Patients with Stomach, Colon, and Rectal Neoplasms. Digestive Diseases and Sciences 2018, 63, 2950–2958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bistas, K.G.; Tabet, J.P. The Benefits of Prebiotics and Probiotics on Mental Health. Cureus 2023, 15, e43217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Młynarska, E.; Gadzinowska, J.; Tokarek, J.; Forycka, J.; Szuman, A.; Franczyk, B.; Rysz, J. The Role of the Microbiome-Brain-Gut Axis in the Pathogenesis of Depressive Disorder. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Title of Site. Available online:. (accessed on Day Month Year).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).