Submitted:

17 July 2025

Posted:

18 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Molecular and Cellular Mechanisms of Injury: Inflammation and Oxidative Stress

4. Nanotechnology for Ultra-Precise Diagnosis

5. Targeted Multi-Modal Therapeutic Strategies

5.1. Nanoparticle-Based Targeted Delivery for the Treatment of Spinal Cord Injury

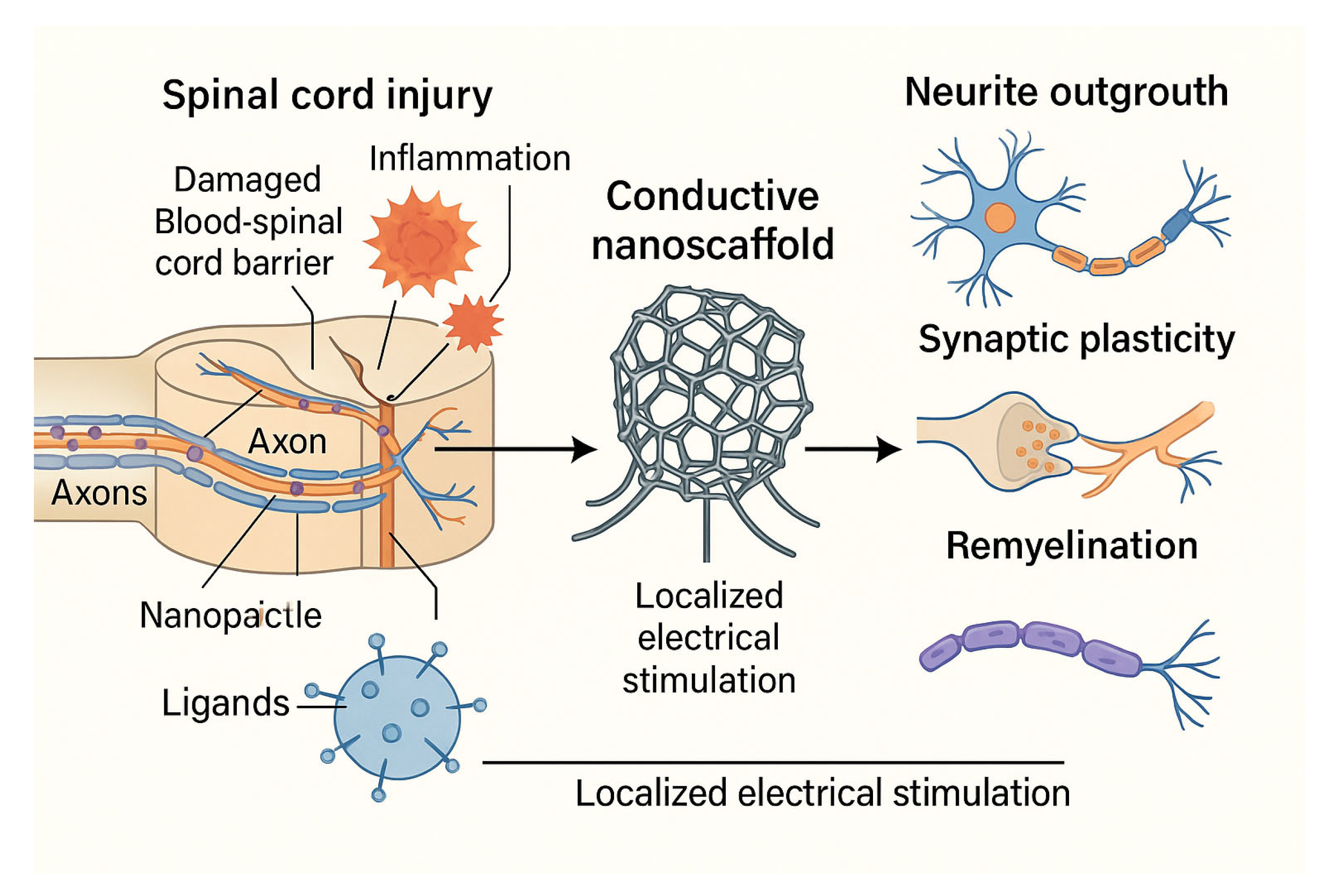

5.2. Electro-Nanohybrid Stimulation

6. Nanotechnological Strategies for CNS Drug Delivery

7. AI-Guided Personalized Nanomedicine

8. Integration with Conventional Therapies and Personalized Nanomedicine

8.1. Physical Rehabilitation

9. Discussion

10. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tran AP, Warren PM, Silver J. The Biology of Regeneration Failure and Success After Spinal Cord Injury. Physiol Rev. 2018;98(2):881–917. [CrossRef]

- Silva GA. Nanotechnology approaches to crossing the blood-brain barrier and drug delivery to the CNS. BMC Neurosci. 2008;9 Suppl 3(Suppl 3):S4. [CrossRef]

- Patel T, Zhou J, Piepmeier JM, Saltzman WM. Polymeric nanoparticles for drug delivery to the central nervous system. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2012;64(7):701–705. [CrossRef]

- Chen S, John JV, McCarthy A, Xie J. New forms of electrospun nanofiber materials for biomedical applications. J Mater Chem B. 2020;8(17):3733–3746. [CrossRef]

- Wang W, Hou Y, Martinez D, Kurniawan D, Chiang WH, Bartolo P. Carbon Nanomaterials for Electro-Active Structures: A Review. Polymers (Basel). 2020;12(12):2946. [CrossRef]

- Gupta AK, Gupta M. Synthesis and surface engineering of iron oxide nanoparticles for biomedical applications. Biomaterials. 2005;26(18):3995–4021. [CrossRef]

- Jokerst JV, Gambhir SS. Molecular imaging with theranostic nanoparticles. Acc Chem Res. 2011;44(10):1050–1060. [CrossRef]

- Blanco-Andujar C, Walter A, Cotin G, et al. Design of iron oxide-based nanoparticles for MRI and magnetic hyperthermia. Nanomedicine (Lond). 2016;11(14):1889–1910. [CrossRef]

- Burnouf T, Agrahari V, Agrahari V. Extracellular Vesicles As Nanomedicine: Hopes And Hurdles In Clinical Translation. Int J Nanomedicine. 2019;14:8847–8859. [CrossRef]

- Bafekry A, Faraji M, Fadlallah MM, et al. Effect of adsorption and substitutional B doping at different concentrations on the electronic and magnetic properties of a BeO monolayer: a first-principles study. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2021;23(43):24922–24931. [CrossRef]

- Gong W, Zhang T, Che M, et al. Recent advances in nanomaterials for the treatment of spinal cord injury. Mater Today Bio. 2022;18:100524. [CrossRef]

- Yang Q, Lu D, Wu J, et al. Nanoparticles for the treatment of spinal cord injury. Neural Regen Res. 2025;20(6):1665–1680. [CrossRef]

- Gu X, Zhang S, Ma W. Prussian blue nanotechnology in the treatment of spinal cord injury: application and challenges. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2024;12:1474711. [CrossRef]

- Wang W, Yong J, Marciano P, O'Hare Doig R, Mao G, Clark J. The Translation of Nanomedicines in the Contexts of Spinal Cord Injury and Repair. Cells. 2024;13(7):569. [CrossRef]

- Hu X, Xu W, Ren Y, et al. Spinal cord injury: molecular mechanisms and therapeutic interventions. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2023;8(1):245. [CrossRef]

- Gu X, Zhang S, Ma W. Bibliometric analysis of nanotechnology in spinal cord injury: current status and emerging frontiers. Front Pharmacol. 2024;15:1473599. [CrossRef]

- Zhang Y, Peng Z, Guo M, et al. TET3-facilitated differentiation of human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells into oligodendrocyte precursor cells for spinal cord injury recovery. J Transl Med. 2024;22(1):1118. [CrossRef]

- Stewart AN, Bosse-Joseph CC, Kumari R, et al. Nonresolving Neuroinflammation Regulates Axon Regeneration in Chronic Spinal Cord Injury. J Neurosci. 2025;45(1):e1017242024. [CrossRef]

- Yu S, Chen X, Yang T, et al. Revealing the mechanisms of blood-brain barrier in chronic neurodegenerative disease: an opportunity for therapeutic intervention. Rev Neurosci. 2024;35(8):895–916. [CrossRef]

- Toader C, Dumitru AV, Eva L, Serban M, Covache-Busuioc RA, Ciurea AV. Nanoparticle Strategies for Treating CNS Disorders: A Comprehensive Review of Drug Delivery and Theranostic Applications International Journal of Molecular Sciences (2024).

- Gupta, A. K., & Gupta, M. (2005). Synthesis and surface engineering of iron oxide nanoparticles for biomedical applications. Biomaterials, 26(18), 3995–4021. [CrossRef]

- Lee, D. E., Koo, H., Sun, I. C., Ryu, J. H., Kim, K., & Kwon, I. C. (2010). Multifunctional nanoparticles for multimodal imaging and theragnosis. Chemical Society Reviews, 41(7), 2656–2672. [CrossRef]

- Jokerst, J. V., & Gambhir, S. S. (2011). Molecular imaging with theranostic nanoparticles. Accounts of Chemical Research, 44(10), 1050–1060. [CrossRef]

- Hong, G., Antaris, A. L., & Dai, H. (2017). Near-infrared fluorophores for biomedical imaging. Nature Biomedical Engineering, 1(1), 0010. [CrossRef]

- Papa S, Ferrari R, De Paola M, et al. Polymeric nanoparticle system to target activated microglia/macrophages in spinal cord injury. J Control Release. 2014;174:15-26. [CrossRef]

- Fortun J, Puzis R, Pearse DD, Gage FH, Bunge MB. Muscle injection of AAV-NT3 promotes anatomical reorganization of CST axons and improves behavioral outcome following SCI. J Neurotrauma. 2009;26(7):941-953. [CrossRef]

- Liu Z, Ran Y, Huang Q, Wang Z, Zhang W, Wu F, et al. Targeted delivery of gene therapy for spinal cord injury using non-viral polymeric nanoparticles. Curr Pharm Des. 2020;26(11):1295–309.

- Li Q, Li C, Zhang X. Research Progress on the Effects of Different Exercise Modes on the Secretion of Exerkines After Spinal Cord Injury. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2024;44(1):62. Published 2024 Oct 1. [CrossRef]

- Zhang Q, Zheng J, Li L, et al. Bioinspired conductive oriented nanofiber felt with efficient ROS clearance and anti-inflammation for inducing M2 macrophage polarization and accelerating spinal cord injury repair. Bioact Mater. 2024;46:173-194. Published 2024 Dec 13. [CrossRef]

- Wu D, Chen Q, Chen X, Han F, Chen Z, Wang Y. The blood-brain barrier: structure, regulation, and drug delivery. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2023;8(1):217. Published 2023 May 25. [CrossRef]

- Van de Winckel A, Carpentier ST, Deng W, et al. Identifying Body Awareness-Related Brain Network Changes after Cognitive Multisensory Rehabilitation for Neuropathic Pain Relief in Adults with Spinal Cord Injury: Delayed Treatment arm Phase I Randomized Controlled Trial. Preprint. medRxiv. 2023;2023.02.09.23285713. Published 2023 Feb 10. [CrossRef]

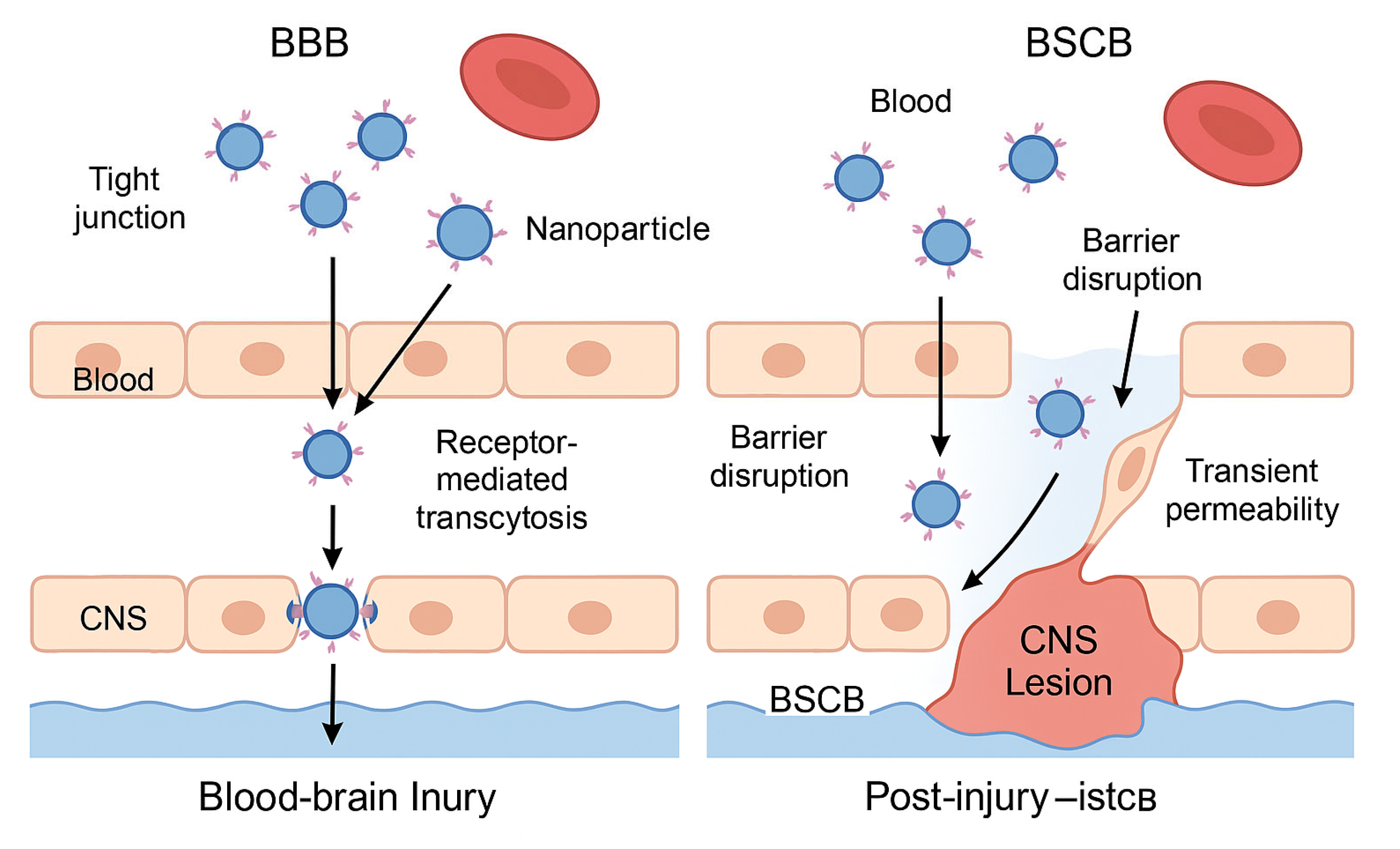

| Parameter | BBB (Blood-Brain Barrier) | BSCB (Blood-Spinal Cord Barrier) |

| Structure | Continuous endothelium with tight junctions; highly selective | Similar to BBB, slightly more permeable under physiological conditions |

| Therapeutic challenge | Blocks over 98% of systemically administered drugs | Less restrictive but still limits large or hydrophilic molecules |

| Nanoparticle strategy | Functionalization with ligands for receptor-mediated transcytosis (e.g., transferrin) | Exploitation of increased permeability after injury |

| Entry mechanism | Receptor-mediated transcytosis across endothelial cells | Passive diffusion through transiently disrupted barrier |

| Optimal timing | Constant, but difficult without targeting ligands | Subacute phase: hours to days post-injury, during inflammation |

| Clinical applications | Alzheimer's, brain tumors, encephalitis | Spinal cord injury, multiple sclerosis, spinal inflammation |

| Nanotherapy advantages | Targeted access with potential for theranostic monitoring | High efficiency when administered during post-injury permeability window |

| Nanoparticle Type | Therapeutic Cargo | Main Advantages | Limitations | Clinical Status |

| Polymeric | Anti-inflammatory drugs, growth factors, antioxidants | Customizable, sustained release, biocompatible | Scalability, burst release, clearance rate | Preclinical, some early-phase trials |

| Liposomal | Hydrophilic/lipophilic drugs, peptides | Good biocompatibility, approved in other indications | Stability, drug leakage, short half-life | Clinically approved for other diseases |

| Exosome-derived | Endogenous miRNAs, proteins, neurotrophic factors | Natural origin, low immunogenicity, high targeting potential | Isolation/purification challenges, batch variability | Preclinical studies |

| Magnetic (e.g., iron oxide) | Drugs + external magnetic control | Magnetic guidance, imaging compatibility | Possible long-term toxicity, low biodegradability | Used in oncology trials, not yet in SCI |

| Prussian Blue | Antioxidants, anti-inflammatory agents | Strong ROS scavenging, neuroprotection | Limited clinical validation, synthesis complexity | Preclinical |

| Carbon Nanotube (CNT) | Electrical stimulation interfaces | Restores neuronal conductivity, bioelectrical signaling | Biocompatibility issues, inflammatory potential | Preclinical (neural interface models) |

| Application Area | Description | Rehabilitative Benefit | Development Status |

| Neurotrophic Factor Delivery | Use of nanoparticles to deliver agents like BDNF, NGF, or IGF-1 to enhance plasticity during motor rehabilitation. | Amplifies the effect of activity-based therapies by promoting synaptic and axonal plasticity. | Preclinical |

| Bioelectronic Interfaces | Integration of conductive nanomaterials into scaffolds or implants to restore electrical signaling and support neuronal reactivation. | Enables functional reactivation of spinal circuits and synergy with FES or robotic training. | Preclinical to early prototyping |

| Nanosensors for Monitoring | Implantable or wearable nanosensors to monitor inflammation, neural activity, or metabolic markers during therapy. | Personalizes rehabilitation intensity and timing based on real-time physiological data. | Emerging technology |

| Gene Modulation via Nanocarriers | Nanoparticles carrying siRNA or miRNA to modulate genes involved in inhibitory signaling or regeneration during rehabilitation phases. | Maximizes the molecular environment's responsiveness to training by modulating key signaling pathways. | Preclinical studies in animal models |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).