1. Introduction

UAVs have evolved from specialized military assets to ubiquitous platforms that support various civilian and military applications, including aerial surveillance, disaster response, environmental monitoring, precision agriculture, and autonomous logistics [

1]. Their operational advantages - high maneuverability, reduced operational costs and the ability to operate in harsh or inaccessible environments - have driven exponential growth in both research initiatives and commercial deployment across multiple domains [

2]. As UAVs become increasingly integrated into critical infrastructure and multi-agent systems, the volume and sensitivity of their data exchanges continue to expand, making secure and reliable communication within UAV networks a paramount challenge for both industry and academia [

3].

Despite their growing adoption, UAV communication systems remain fundamentally constrained by hardware limitations, energy capacity restrictions, and dynamic network topologies. UAVs operate with limited computational resources on board, making traditional cryptographic approaches, such as full-scale RSA, TLS implementations, or computationally intensive AES variants, impractical for real-time aerial operations [

4]. Additionally, UAV networks frequently operate in self-organized, highly dynamic configurations, particularly in swarm deployments where coordinated systems of potentially hundreds of drones must perform missions autonomously with minimal human oversight [

5]. These operational conditions introduce significant complexities in key management, authentication, and data confidentiality protocols [

6].

The emergence of quantum computing poses an additional and unprecedented threat to UAV communication security. Quantum computers, leveraging Shor’s and Grover’s algorithms, have the potential to break conventional cryptographic methods, including both symmetric and asymmetric schemes that currently secure UAV communications [

7]. This quantum threat necessitates the adoption of post-quantum cryptography (PQC) algorithms specifically designed to remain secure against quantum attacks while maintaining efficiency suitable for resource-constrained UAV platforms [

8]. Recent developments in lightweight post-quantum algorithms, including lattice-based cryptography and code-based cryptography, offer promising solutions for future-proofing UAV security [

7].

Recent research efforts have explored innovative approaches to UAV security, including the integration of blockchain technology for decentralized identity and key management in drone swarms [

9]. Blockchain-based authentication schemes, such as BETA-UAV, exploit the inherent properties of immutability and decentralization to establish secure communication sessions while reducing reliance on centralized trust infrastructures [

10]. Similarly, Physical Unclonable Function (PUF)-based authentication protocols have emerged as lightweight alternatives that eliminate the need for storing sensitive cryptographic keys on UAV devices, thereby mitigating key storage vulnerabilities [

11].

The advent of the ASCON family of authenticated encryption algorithms, selected as the NIST lightweight cryptography standard, represents a significant milestone for UAV security [

12]. ASCON’s sponge-based design offers superior performance metrics compared to traditional AES implementations while maintaining robust security properties suitable for resource-constrained environments [

4]. Performance evaluations demonstrate that ASCON-128a provides optimal balance between efficiency and security for UAV communication systems, achieving comparable throughput to AES with significantly reduced memory footprint and energy consumption [

13].

Figure 1.

Multilayer Security Focus Areas for UAV Communications: Lightweight Encryption, Post-Quantum Cryptography, Trust Mechanisms, Application Suitability, Key Management Schemes, and a Multilayer Security Framework.

Figure 1.

Multilayer Security Focus Areas for UAV Communications: Lightweight Encryption, Post-Quantum Cryptography, Trust Mechanisms, Application Suitability, Key Management Schemes, and a Multilayer Security Framework.

Regulatory developments further underscore the urgency of implementing robust UAV security measures. The Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) has proposed new cybersecurity regulations requiring design approval applicants to identify, assess, and mitigate risks from intentional unauthorized electronic interactions (IUEI) in transport category aircraft, including UAV systems [

14]. Similarly, the European Union Aviation Safety Agency (EASA) has issued draft policies mandating secure data transmission and resilient control link architectures in civilian UAV operations [

15]. These regulatory frameworks emphasize the need for standardized, lightweight security solutions that can be effectively deployed across diverse UAV platforms.

Contemporary UAV security research has predominantly focused on single-layer defensive mechanisms or narrow application domains, lacking comprehensive frameworks that address the full spectrum of security challenges across multiple communication layers [

16]. While recent surveys have examined specific aspects such as physical layer security or blockchain applications in UAV networks, there remains a critical gap in understanding how lightweight cryptographic techniques, scalable key management strategies, and cross-layer security mechanisms can be integrated into unified security architectures [

17,

18]. This fragmentation limits the development of holistic security solutions capable of addressing the complex, multi-faceted threat landscape facing modern UAV deployments.

The rapid evolution of UAV swarm technology further complicates the security landscape. Modern swarm systems can coordinate hundreds of autonomous drones using distributed control algorithms and real-time communication protocols. These swarms leverage artificial intelligence and machine learning to navigate complex environments while maintaining synchronized operations, but they also present new attack vectors and scalability challenges for traditional security mechanisms [

19]. Energy-efficient communication protocols, including non-orthogonal multiple access (NOMA) schemes, must be carefully designed to balance performance optimization with security requirements [

20].

This comprehensive review addresses these critical gaps by providing an integrated analysis of secure communication techniques for UAV networks, with particular emphasis on lightweight encryption methods and efficient key management schemes tailored to resource-constrained aerial platforms. The review critically examines recent advances in symmetric and asymmetric cryptography suitable for constrained devices, evaluates the feasibility of decentralized trust infrastructures such as blockchain, and explores post-quantum solutions that anticipate future computational threats. Furthermore, this work expands the discussion to encompass security threats and defenses across multiple communication layers, from physical channel obfuscation to application-layer authentication protocols. Through a multilayer security framework and a performance analysis of lightweight cryptographic algorithms, this review offers practical guidance for researchers and system designers developing secure UAV architectures that meet real-world operational constraints and mission requirements.

To support this analysis, the paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 provides background on UAV communication challenges and reviews existing survey studies in the field.

Section 3 outlines the computational, energy, and storage constraints of UAV platforms and introduces key metrics for evaluating lightweight cryptographic solutions.

Section 4 discusses the fundamental requirements and design trade-offs of lightweight cryptographic systems.

Section 5 surveys a range of encryption techniques, including symmetric, asymmetric, and post-quantum cryptography, that are optimized for UAV deployment.

Section 6 presents key management strategies, including static, dynamic, and hardware-assisted approaches.

Section 7 introduces a multilayer security framework for UAV communication systems.

Section 8 evaluates the suitability of these techniques across different UAV application scenarios.

Section 9 highlights current limitations and outlines emerging research directions.

Section 10 concludes the paper with a synthesis of findings and future outlook.

2. Background and Related Survey Studies

UAV communication security has become a prominent area of research due to the increasing reliance on drones for surveillance, delivery, and mission-critical operations. A substantial number of survey papers have explored security challenges by addressing threats, countermeasures, and architectural models for secure UAV networking. However, these surveys tend to examine isolated components such as detection techniques [

2], physical-layer vulnerabilities [22], or specific cryptographic schemes [

4,

7], rather than offering a unified framework that spans the entire communication and control stack. This fragmented treatment limits the ability to develop end-to-end, secure, and efficient UAV systems tailored to real-world deployment constraints.

Table 1 offers a structured comparison of existing survey literature, mapping each study’s contributions across six essential security dimensions: lightweight encryption (LWE), key management (KM), post-quantum cryptography (PQC), blockchain or PUF-based trust mechanisms (B/P), multilayer security frameworks (MLS), and application suitability (APS). Early foundational works, such as those by Abro et al. [

2] and Yassine et al. [22], provide general overviews of UAV detection and privacy concerns, yet overlook critical emerging domains such as lightweight cryptography, quantum-safe encryption, and scalable key exchange. Similarly, studies like Patel et al. [

4] emphasize efficient encryption algorithms but do not incorporate key management or trust frameworks.

Recent surveys have begun to bridge these gaps. For instance, Khan et al. [

7], Xia et al. [

8], and Aissaoui et al. [

30] explore post-quantum cryptographic solutions suitable for UAV contexts. Hafeez et al. [

10] and Choi et al. [

28] integrate blockchain and PUF-based trust mechanisms to enhance authentication and key agreement. Abdelaziz et al. [

21] and Rugo et al. [

24] extend their coverage across multiple layers but still do not unify these elements into a cohesive framework. As summarized in

Table 1, none of the reviewed works simultaneously address all six dimensions of UAV security, leaving a gap in the literature for holistic, future-proof solutions.

This review addresses the identified limitations by presenting a unified analysis of secure UAV communication technologies. It integrates lightweight encryption techniques, scalable key management methods, post-quantum secure protocols, and blockchain or PUF-based trust solutions within a multilayer security architecture. In addition, it evaluates these technologies against operational factors such as latency, computational overhead, and mission-specific constraints. By offering a comprehensive framework that spans cryptographic design to system-level deployment, this work aims to guide future research and implementation of secure, scalable, and resilient UAV communication networks.

3. Threat Landscape in Drone Networks

UAVs are increasingly used across diverse domains such as military reconnaissance, precision agriculture, logistics, and disaster response. These autonomous or semi-autonomous systems rely heavily on wireless communication to exchange commands and application data within dynamic and often decentralized network environments. However, UAVs are particularly vulnerable to cyber-attacks due to their reliance on open-air interfaces, constrained energy and computational resources, and constant mobility. To contextualize these vulnerabilities, this section presents a threat analysis mapped to the OSI model, highlighting critical attacks such as eavesdropping, spoofing, jamming, and routing manipulation, and explores how contemporary cryptographic algorithms are employed to mitigate these risks in real-world UAV deployments.

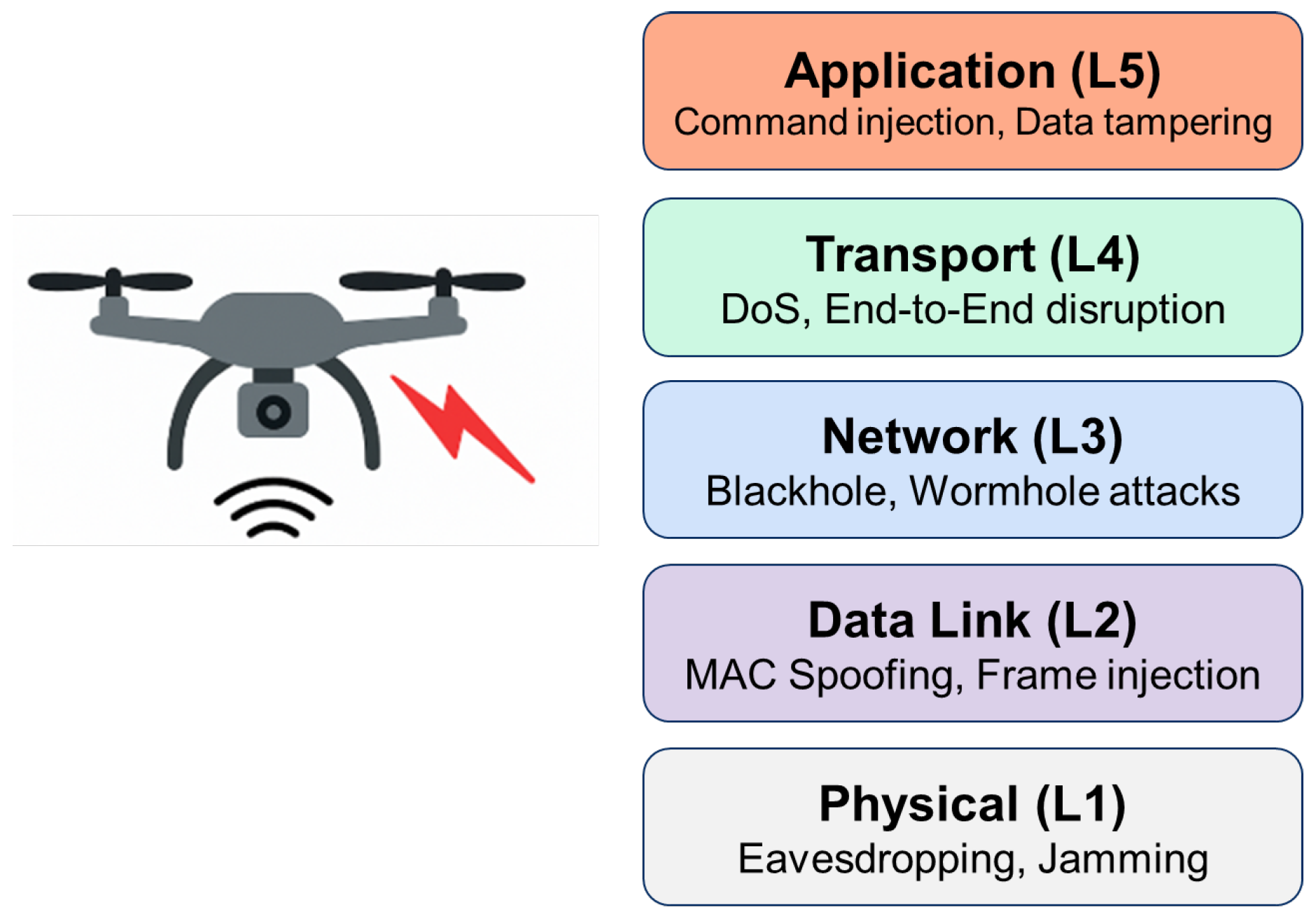

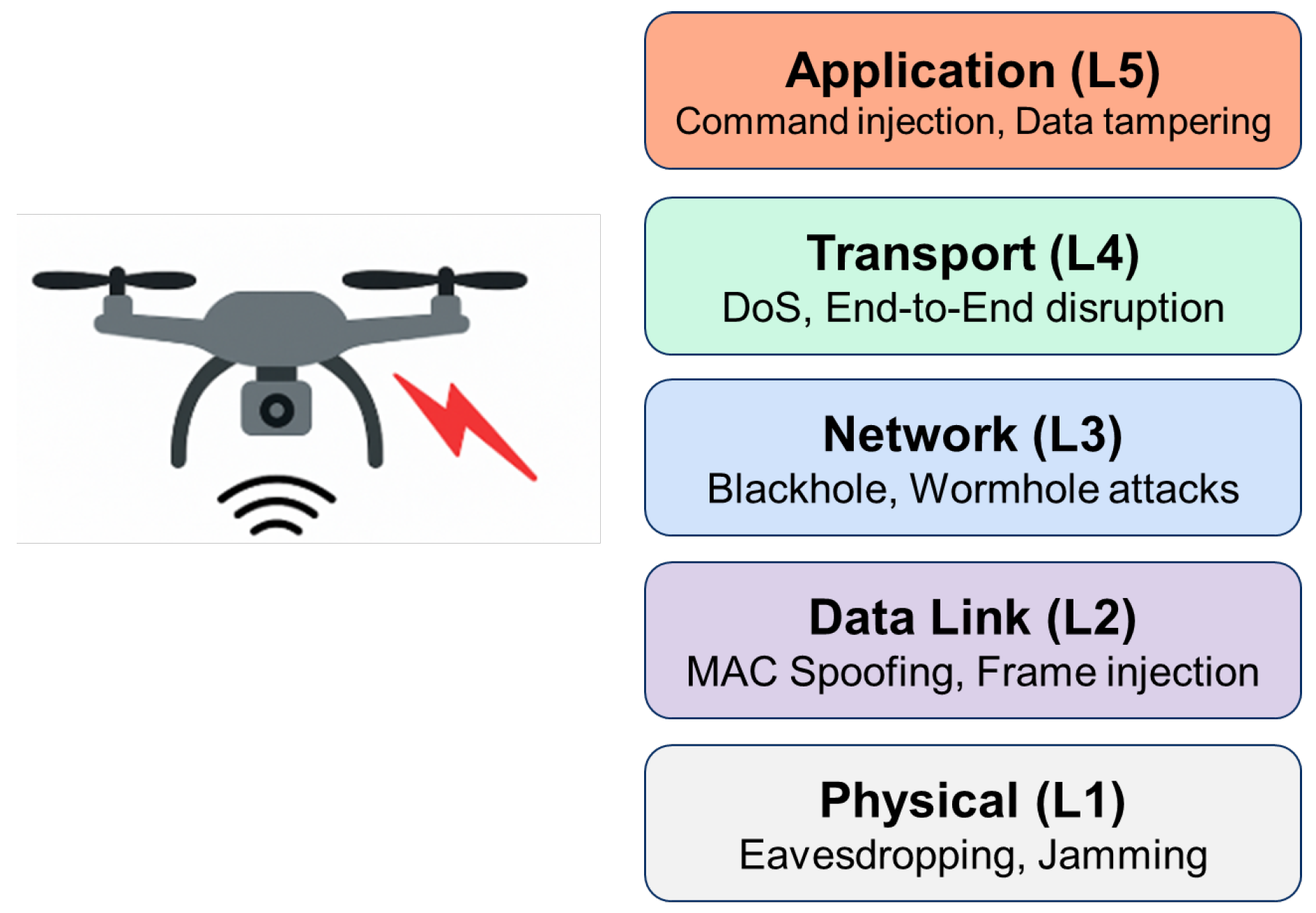

Figure 2.

Security threats mapped to the five-layer OSI model for UAV networks.

Figure 2.

Security threats mapped to the five-layer OSI model for UAV networks.

As illustrated in

Figure 3, each OSI layer is associated with specific threat types—ranging from physical-layer jamming to application-layer command injection. Correspondingly,

Table 2 summarizes cryptographic countermeasures tailored to each layer, demonstrating the layered approach required for securing UAV communications.

3.1. Threats at the Physical Layer

The physical layer (L1) governs radio frequency communication and is particularly susceptible to attacks due to its open and broadcast nature. Among the most critical threats at this layer are jamming and eavesdropping, both of which can severely disrupt mission-critical operations or compromise sensitive information. In surveillance and military contexts, adversaries may exploit these vulnerabilities to intercept or jam UAV communication links, potentially derailing operations or rendering drones uncontrollable [

32,

33].

Jamming involves the deliberate transmission of disruptive signals that degrade the UAV’s communication channel, resulting in a denial of control or data loss. To counteract this, frequency hopping, spread-spectrum techniques, and cognitive radio approaches are employed to adapt transmission parameters in real time. Meanwhile, eavesdropping exploits the open nature of UAV broadcasts, allowing adversaries to passively intercept data streams. In response, physical layer security (PLS) methods such as artificial noise injection, cooperative jamming, and secure beamforming have been adopted to improve confidentiality without relying solely on upper-layer encryption [

18,

34].

The characteristics of aerial-to-ground (A2G) channels further exacerbate these vulnerabilities. High mobility, Doppler shifts, multipath fading, and variable line-of-sight conditions present challenges for both communication reliability and security. These dynamic propagation environments are difficult to secure through static cryptographic approaches and demand real-time adaptation [

18]. Moreover, UAVs themselves can serve as mobile adversaries, launching eavesdropping or jamming attacks against terrestrial networks. Due to their elevation and maneuverability, malicious UAVs can maintain advantageous positions for longer durations, enhancing the impact of their attacks [

35].

3.2. MAC and Data Link Layer Attacks

The Medium Access Control (MAC) and data link layers (L2) are fundamental to identity management, address resolution, and intra-network communication in UAV systems. These layers are particularly susceptible to spoofing, injection, and protocol-based attacks, which can severely disrupt communication integrity, cause misrouting, or lead to drone isolation and mission failure [

36,

37].

Spoofing attacks at the MAC layer involve an adversary falsifying a legitimate MAC address or control signal to impersonate a trusted device. In UAV networks, this can mislead drones into communicating with a malicious ground station or unauthorized peer. The consequences may include command hijacking, loss of situational awareness, or control redirection, potentially culminating in mid-air collision or disconnection from the swarm [

38].

Frame injection attacks are a significant threat, wherein attackers craft and transmit unauthorized MAC frames to UAVs. These frames may include forged control commands, fake telemetry updates, or disarm signals that alter the UAV’s behavior without detection. The risk is particularly high in autonomous or semi-autonomous missions, where UAVs depend on continuous and authenticated command streams [

39]. Studies have demonstrated that flooding UAV networks with repeated spoofed control packets, such as ARP replies or disarm requests, can lead to denial-of-service (DoS) scenarios or force active drones to ground [

40].

Data link layer vulnerabilities are further amplified by using lightweight, often unencrypted communication protocols like MAVLink. As MAVLink messages are typically transmitted in plaintext, attackers can eavesdrop on or alter control flows using simple packet sniffing tools. ARP spoofing and dictionary attacks on these links allow adversaries to gain full access to flight commands, location updates, and mission logs [

39]. Replay attacks and message fabrication are also possible, especially when cryptographic protections are absent or improperly implemented.

Tactical data links used in military UAV operations also face threats. Attackers may exploit vulnerabilities in protocol headers, frequency allocation, or channel access patterns to inject falsified control messages or jam signal propagation. In some proposed architectures, the removal of MAC overhead in relay-based designs aims to optimize link reliability, but also opens new attack surfaces [

41]. Such designs require careful threat modeling to avoid exposure to spoofing, flooding, and timing manipulation attacks.

Overall, attacks at the MAC and data link layers can cause message interception, redirection, impersonation, or channel disruption. These vulnerabilities form a critical attack surface in UAV communications and must be addressed in parallel with upper-layer defenses.

3.3. Network and Transport Layer Attacks

UAV networks are highly susceptible to sophisticated attacks at the network (L3) and transport (L4) layers, particularly in decentralized mission scenarios such as military swarms or search and rescue operations. These vulnerabilities are exacerbated by the inherent mobility, dynamic topologies, and wireless communication dependencies of UAV systems, making them attractive targets for attackers aiming to disrupt routing protocols or interfere with end-to-end data exchange [

36,

42].

At the network layer, some of the most disruptive attacks include Sybil, black hole, and wormhole attacks. In a Sybil attack, a malicious UAV or ground node assumes multiple false identities to manipulate routing paths and gain disproportionate influence over the network. Black hole attacks involve compromised nodes that falsely advertise optimal routes to attract and then drop all passing packets, effectively severing communication links. Wormhole attacks, on the other hand, tunnel packets between two distant malicious nodes to distort the network topology, bypass security checks, or redirect traffic through adversarial paths [

36,

43].

In collaborative threat scenarios, Sybil identities may be used to enable black hole nodes to bypass detection systems, or wormhole nodes may help propagate false routes more rapidly. Such multi-vector attacks are particularly concerning in UAV swarms, where synchronized communication and consistent routing are vital for mission success. The compromise of even a small subset of drones can lead to misdirection, isolation, or mission-wide disruption.

The transport layer is equally vulnerable. DoS attacks pose a significant threat by flooding UAV communication links, leading to loss of connectivity between aerial units and ground control stations. These attacks can overwhelm bandwidth-constrained links, degrade telemetry reporting, and interrupt the transmission of critical commands. Session hijacking at this layer allows attackers to intercept and manipulate session information, including control packets and encryption keys. Once hijacked, adversaries can inject falsified data, suppress legitimate commands, or seize full control of UAVs mid-flight [

4,

44].

In environments where UAVs operate with constrained energy and compute resources, these transport-layer threats are especially damaging. The lack of persistent session validation and the reliance on lightweight, low-latency protocols makes session-based exploits more feasible for attackers with modest capabilities. Furthermore, vulnerabilities in key exchange protocols or sequence number synchronization can open UAV communication systems to replay attacks and connection resets.

These L3 and L4 threats highlight the necessity of designing UAV networks that account for adversarial manipulation of both routing logic and transport-layer session integrity. Effective detection and response mechanisms must be layered into the network stack to address both individual and collaborative adversarial behaviors before they propagate across the fleet.

3.4. Application Layer Vulnerabilities

The application layer (L5) in UAV networks is a prime target for cyber-attacks due to its role in facilitating mission-critical tasks such as remote command execution, software updates, mission planning, and data offloading. These operations typically involve communication between UAVs and cloud services or ground control stations, introducing multiple vectors for application-layer compromise [

36,

37].

One of the most pressing threats is unauthorized access to cloud-connected UAV services. When authentication mechanisms or access control protocols are insufficient, adversaries may intercept or manipulate mission data, gain control over drone navigation, or extract sensitive information from flight logs. These vulnerabilities are especially prevalent in multi-UAV systems that lack granular access restrictions or encrypt communication inconsistently [

45].

Software update processes also present significant risks. UAVs commonly perform over-the-air (OTA) firmware and software updates, which, if not properly authenticated, can be hijacked by attackers. In such scenarios, malicious payloads may be inserted during the update process, granting adversaries persistent access to UAV systems or allowing them to install backdoors for future exploitation [

46,

47].

Command injection attacks represent another critical threat. These attacks involve the manipulation of application interfaces to reroute drones, alter payload delivery destinations, or disrupt mission objectives. For example, in logistics operations, attackers could exploit unsecured control channels to redirect a stolen UAV to an unauthorized location, leading to physical asset loss or theft [

48].

In many UAV deployments, sensitive credentials such as FTP login details or update server keys are stored in plaintext within application-level code or configuration files. This creates a vulnerability in which attackers can extract these credentials to gain persistent control over the UAV, exfiltrate stored data, or intercept telemetry streams. Plaintext storage and hardcoded keys also simplify offline credential guessing and replay attacks.

Together, these application-layer threats represent a high-impact attack surface, particularly in commercial and civilian UAV operations that interface with cloud infrastructure, third-party APIs, and remote configuration systems. As the reliance on remote UAV management continues to increase, addressing these vulnerabilities is essential for ensuring operational trust and mission assurance.

3.5. Cross-Layer Attack Vectors

UAV networks are increasingly exposed to cross-layer attacks, in which adversaries exploit interdependencies between protocol layers to amplify the scope and severity of their disruption. Unlike conventional single-layer threats, cross-layer attacks are characterized by their ability to trigger cascading failures across multiple layers of the communication stack, ultimately compromising mission-critical functionality [

24,

49].

One prominent example involves a jamming attack launched at the physical layer (L1), which disrupts wireless signal integrity and impedes packet transmission. This seemingly localized interference can propagate to the network layer (L3), where it prevents timely updates of routing tables or neighbor discovery processes. In turn, the disrupted network layer can cause malfunctions at the application layer (L5), such as the failure of real-time video streaming or interruption of command-and-control channels. These cascading effects are particularly dangerous in multi-UAV swarms, where node interdependence and tight synchronization are essential to maintaining formation, coverage, and cooperative behavior [

34].

Cross-layer threats are further exacerbated by the operational constraints of UAVs, including mobility, limited energy, and dynamic topologies. In such environments, attackers may leverage time-synchronized or coordinated strategies that simultaneously target multiple layers, leading to complex failure patterns that are difficult to detect using traditional, layer-specific intrusion detection systems. For instance, adversaries may combine physical-layer jamming with transport-layer flooding or spoofing to overload processing pipelines and disrupt system state consistency [

36].

Compromises at lower layers can also undermine higher-level trust and authentication mechanisms. A breach of link-layer synchronization may degrade encryption performance or create misalignment in session management protocols. Similarly, manipulation of timing information across MAC and network layers can enable routing misdirection or replay of sensitive telemetry data, thus undermining situational awareness and UAV coordination.

These multi-faceted threats illustrate that cross-layer attack vectors are not only more disruptive but also harder to mitigate, particularly in autonomous or semi-autonomous UAV deployments. Given their ability to mask indicators across layers, cross-layer attacks challenge the assumptions of modular defense frameworks and demand unified monitoring and anomaly correlation across the protocol stack.

To consolidate the insights presented across the OSI layers,

Table 3 provides a high-level summary of the threat landscape in UAV networks. It maps each layer to its dominant vulnerabilities, common attack vectors, and the corresponding impact on UAV operations. This overview not only highlights the multidimensional nature of cyber threats but also underscores the necessity of a layered and context-aware defense strategy in UAV system design.

Securing UAV communication against the broad spectrum of threats identified across the OSI model requires the integration of robust cryptographic mechanisms. However, conventional encryption protocols often exceed the computational and energy capabilities of UAV platforms, especially in swarm-based or long-duration deployments. This necessitates a shift toward cryptographic techniques specifically optimized for constrained environments. The following section explores the core requirements, design principles, and evaluation metrics for lightweight cryptography, which has emerged as a viable solution for achieving secure, real-time communication in UAV systems under resource limitations.

4. Overview of Lightweight Cryptographic Requirements

The increasing deployment of digital systems in resource-constrained environments, such as UAVs, IoT devices, and embedded platforms, has increased the demand for cryptographic solutions that are both secure and efficient. Traditional encryption algorithms often prove unsuitable for these platforms due to limitations in memory, processing speed, throughput, energy consumption, and implementation cost. To overcome these challenges, lightweight cryptography has emerged as a promising approach, offering an optimal balance between security and resource efficiency, particularly for real-time and low-power operations [

50,

51].

A foundational consideration in this domain is the characterization of what constitutes “lightweight” cryptography. Although such schemes are typically simpler and faster than conventional algorithms, these benefits may entail reduced performance margins or lower cryptographic strength [

50,

51]. Accordingly, a clear understanding of the core design requirements is essential for evaluating and selecting algorithms suitable for UAV applications.

The literature consistently highlights four principal metrics for lightweight cryptographic systems: (1)

computational complexity, defined by the number of logical operations required for encryption or decryption [

52]; (2)

memory footprint, which encompasses both code size (ROM) and working memory (RAM) [

53]; (3)

energy consumption, which is critical for battery-operated or energy-harvesting UAVs [

54,

55]; and (4)

latency, the time needed to compute a single encryption or decryption block, which is particularly important in time-sensitive missions [

53,

56].

To address these requirements, a diverse set of lightweight cryptographic primitives has been developed. Prominent among them are lightweight block ciphers such as PRESENT [

57], SPECK, and SIMON [

58,

59], which are optimized for compact implementations on constrained devices. Similarly, lightweight stream ciphers including Trivium [

60] and Grain [

61] provide rapid, low-overhead encryption suitable for continuous data streams. For public-key operations, Elliptic Curve Cryptography (ECC) [

62,

63] remains a leading choice due to its high security-to-resource ratio and reduced key sizes compared to RSA or DSA [

64].

The remainder of this section is structured as follows:

Section 4.1 explores the computational and energy constraints inherent to UAV platforms.

Section 4.2 outlines the standard evaluation metrics for lightweight cryptography, and

Section 4.3 discusses design principles and performance-security trade-offs that influence algorithm selection.

4.1. Resource Constraints in UAV Platforms

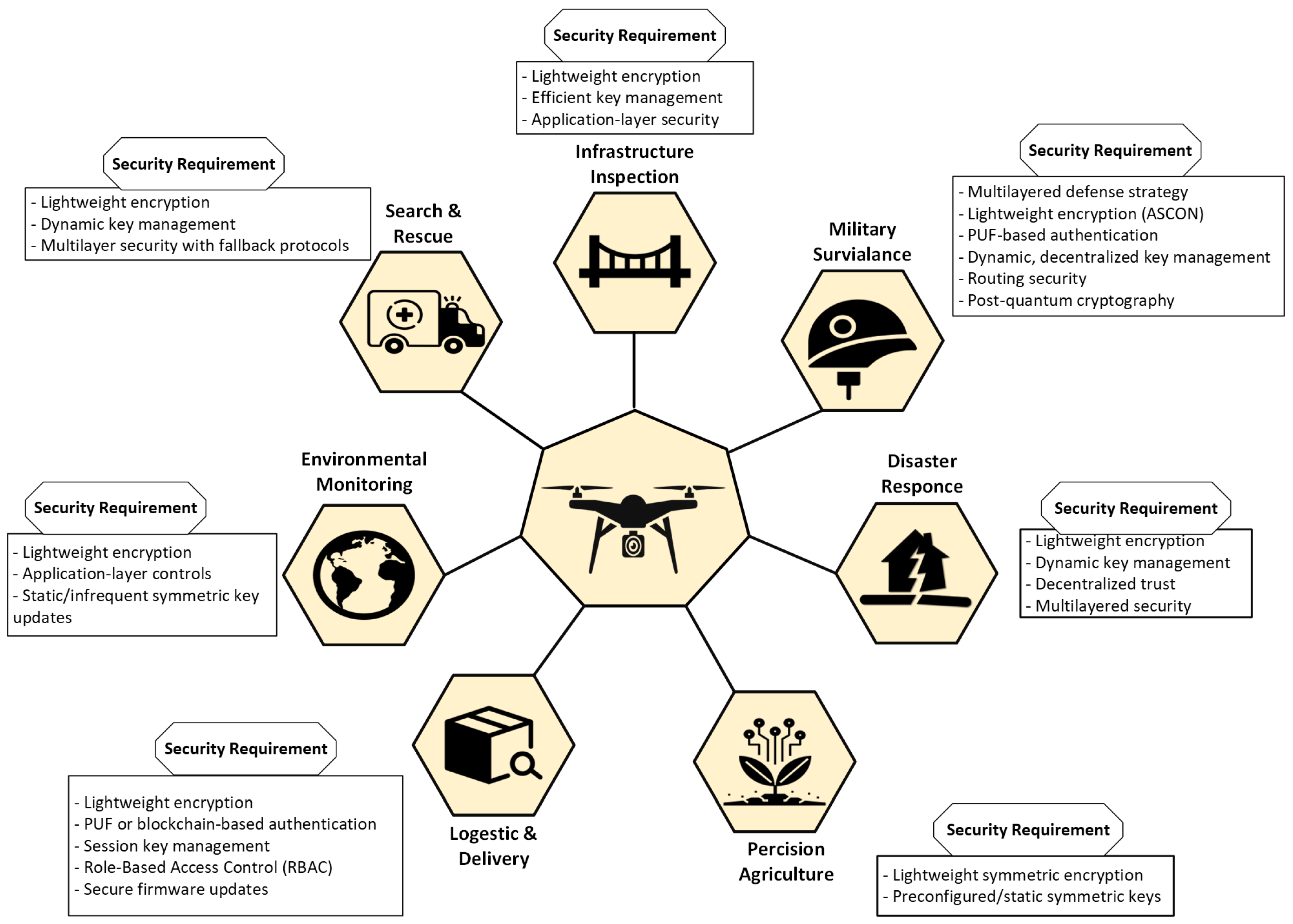

Recent advancements in UAV technologies have led to their widespread adoption across numerous public and industrial sectors. UAVs are now deployed in diverse domains, including surveillance [

65], environmental monitoring [

66], disaster response [

67], delivery services [

68,

69], military operations [

70], traffic monitoring [

71], and precision agriculture [

72]. Each application imposes unique demands on UAV platforms, often under stringent resource constraints. For instance, UAVs used in real-time video surveillance or disaster response typically capture and transmit high-resolution images or video, requiring low-latency communication and fast data processing, all while operating on limited battery power [

73,

74]. In contrast, agricultural UAVs conducting periodic mapping may prioritize data storage and secure network connectivity over computational speed [

75]. For delivery UAVs, energy efficiency is critical for maximizing flight range, while stable communication ensures reliable navigation and real-time tracking, particularly in dynamic environments such as urban areas or traffic congestion [

76].

Despite their growing utility, UAVs are inherently constrained by limited energy, processing capability, memory, latency tolerance, and communication bandwidth. Energy efficiency is particularly challenging, as UAVs are typically battery-powered and may not have opportunities to recharge during extended missions [

77]. Power-intensive operations significantly reduce flight time. Most UAVs rely on low-power microcontrollers that are not suitable for computationally demanding tasks. Memory is also limited, particularly in small and nano-scale UAVs, restricting the deployment of large datasets or advanced algorithms. Furthermore, many UAV applications require on-board, real-time processing and low-latency response, especially in mission-critical operations such as object tracking or autonomous navigation [

78]. Cryptographic functions and control algorithms must therefore be computationally lightweight to avoid introducing delays. Communication bandwidth can also be limited or highly variable, requiring compact and efficient encryption protocols. These challenges are especially pronounced in lightweight UAVs, which are chosen for their mobility and ease of deployment, but often lack advanced hardware support. Consequently, both hardware and software components must be optimized to meet operational demands without compromising system performance or mission success.

Table 4 highlights selected studies that emphasize various resource limitations in UAV systems.

4.2. Definition and Metrics of Lightweight Cryptography

To assess the suitability of lightweight cryptographic algorithms for constrained platforms, it is necessary to evaluate not only their security strength but also their performance under limited computational and energy budgets.

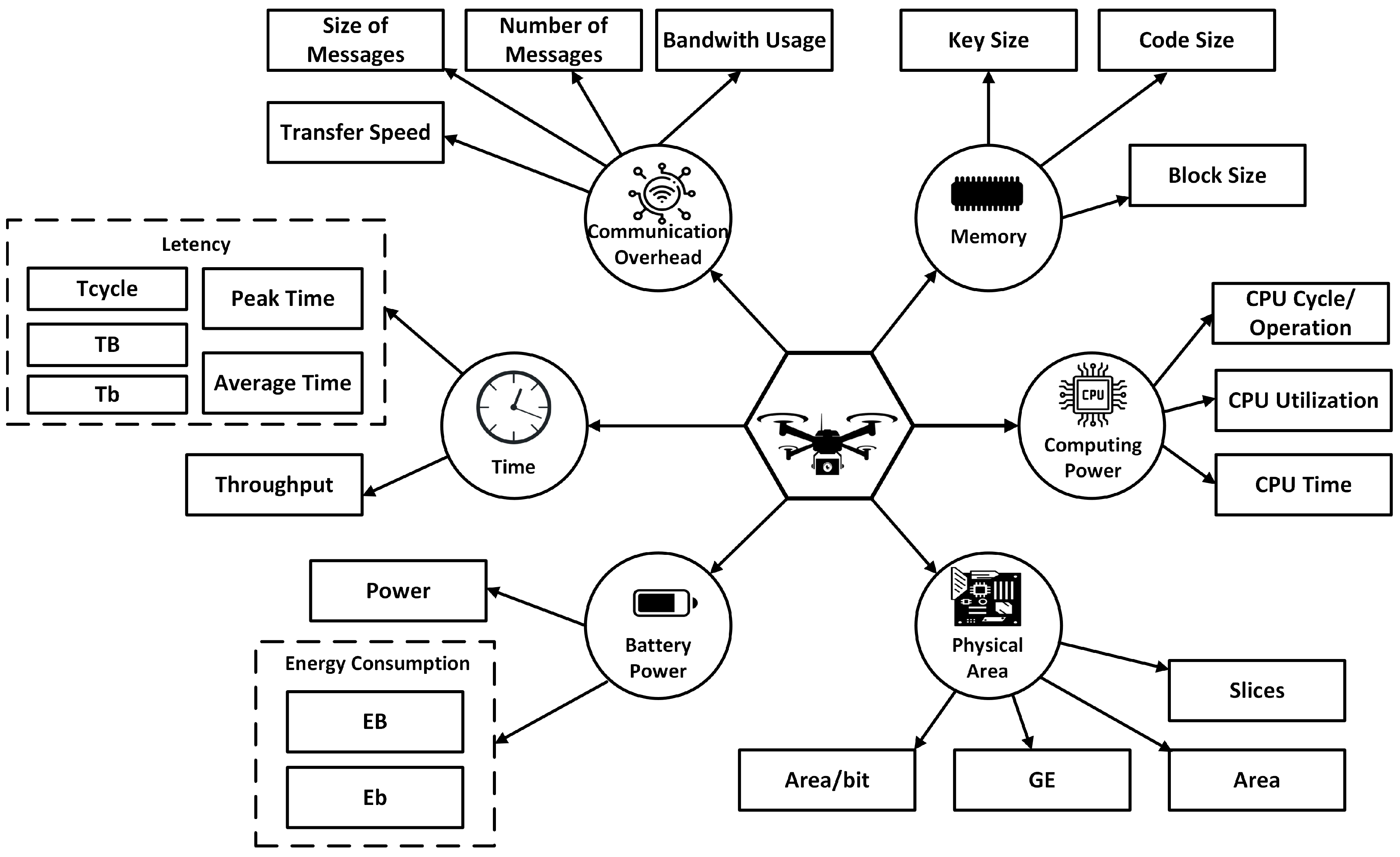

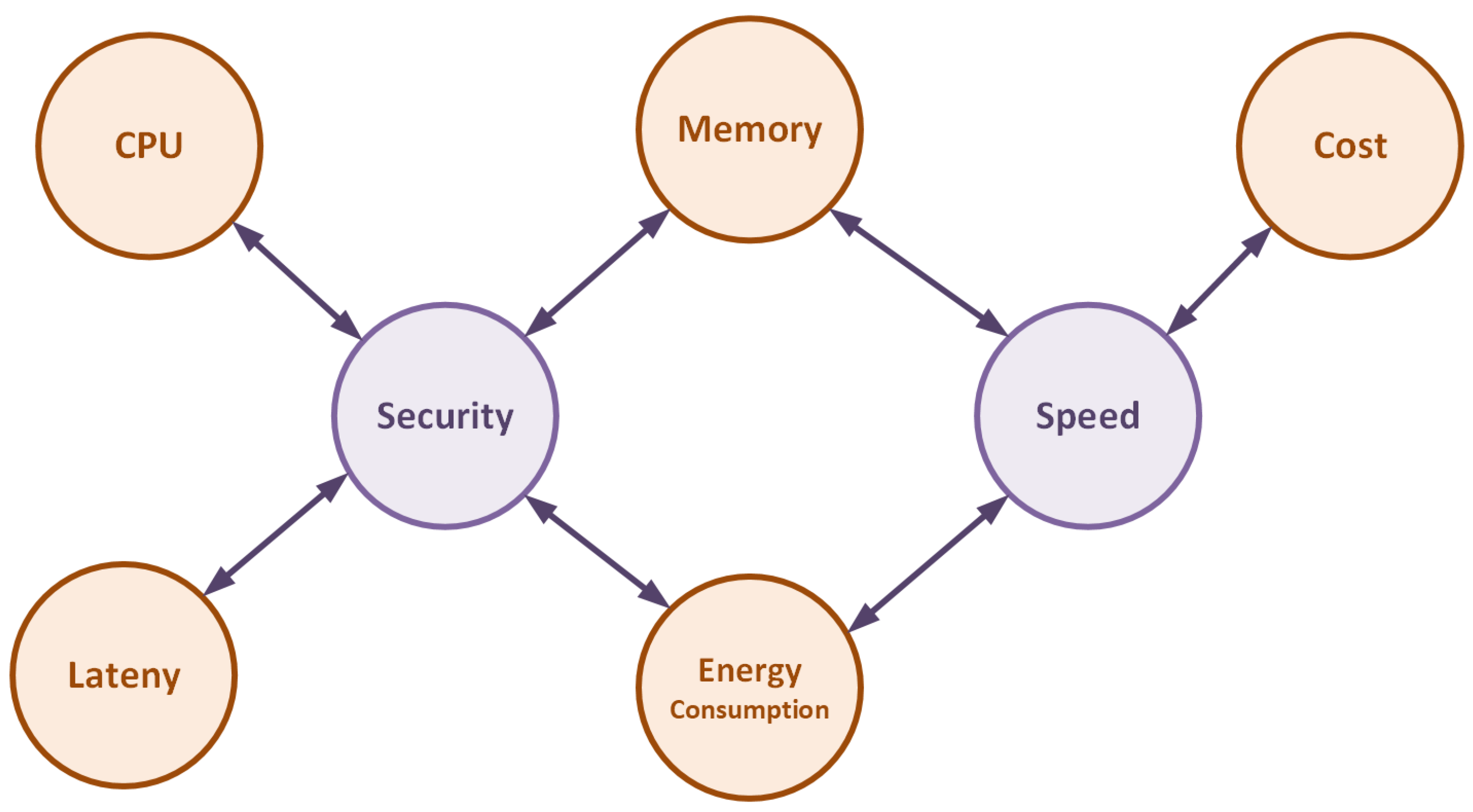

Figure 4 summarizes key operational challenges and the corresponding metrics used to evaluate algorithm efficiency.

A primary consideration is hardware cost, which is often expressed using metrics such as silicon area, slice usage, area per bit [

90], or gate equivalents (GE) [

91,

92]. GE represents the area needed to implement an algorithm on an integrated circuit and serves as a proxy for cost and complexity.

Latency is another essential metric, representing the time taken from the start of an operation to the generation of output [

91]. It can be measured in clock cycles per operation [

93,

94], peak execution time, or average execution time [

4,

95]. For evaluating throughput, which measures the volume of data processed per unit time, hardware performance is typically evaluated at 100 kHz, while software implementations use 4 MHz CPU frequencies [

96,

97].

In battery-powered systems, energy and power consumption are critical. Metrics such as energy per bit [

90,

92,

98] or energy per operation [

96] directly impact the longevity of UAV missions.

Memory usage is also a key constraint. This includes RAM for runtime operations and ROM for storing constants, such as S-boxes or precomputed keys [

91,

95]. Evaluation metrics such as code size, key size, and block size are commonly used to estimate storage requirements [

45,

96].

Given the limited processing capabilities of UAV hardware, computational efficiency must also be assessed. Metrics such as CPU cycles per operation [

98], CPU utilization percentage [

45], and CPU execution time [

95] provide a quantitative basis for comparison.

In networked environments, communication overhead must be minimized. Metrics such as message size [

93,

98], number of transmissions [

98], transfer speed [

45], and bandwidth utilization [

95] help assess the communication efficiency of cryptographic protocols.

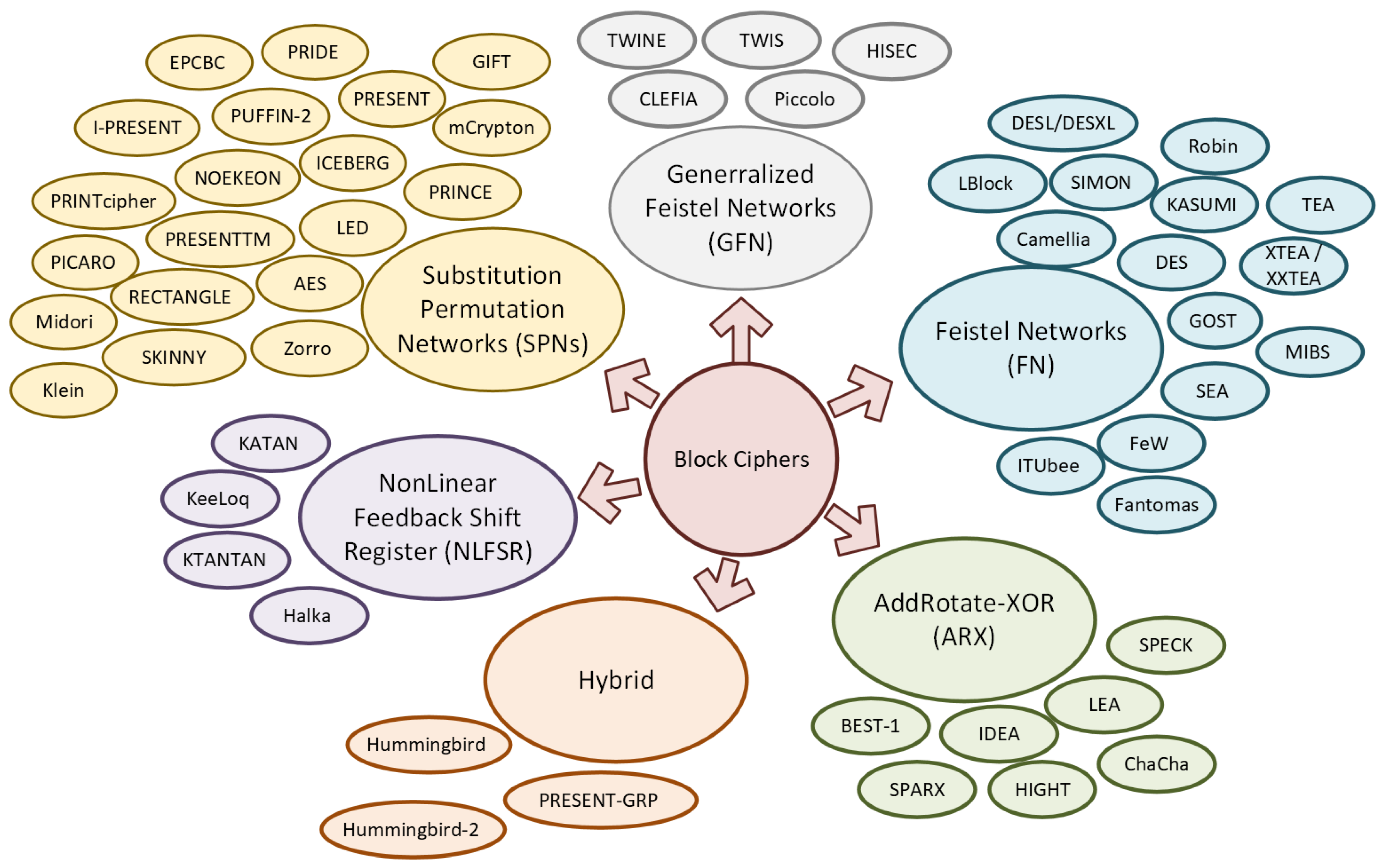

While reducing resource consumption, cryptographic algorithms must continue to meet essential security requirements. Standard internal structures used to achieve this include Substitution-Permutation Networks (SPN), Feistel Networks (FN), Generalized Feistel Networks (GFN), Add-Rotate-XOR (ARX), Nonlinear Feedback Shift Registers (NLFSR), and hybrid models. Security is typically quantified in terms of minimum strength (in bits) and resistance to side-channel and fault injection attacks [

95,

96].

Table 5 and

Table 6 summarize key evaluation metrics and studies that have applied them.

NIST’s [

91] Lightweight Cryptography Project serves as a standard reference to evaluate various algorithms. [

99] was the first to use both NIST and ISO standards as benchmarks for selecting optimal lightweight authentication cryptographic ciphers. This study develops evaluation metrics and criteria based on various requirements and then applies hybrid multi-criteria decision-making (MCDM) methods, such as CRITIC and TOPSIS, to objectively weight the criteria and rank the alternatives. Therefore, it provides a valuable benchmark for the assessment and ranking of lightweight cryptographic ciphers.

4.3. Design Principles: Trade-offs and Optimization

Designing lightweight cryptographic algorithms for UAVs involves balancing security requirements with constraints on energy, memory, and computational power. As discussed in previous sections, these limitations restrict the use of conventional cryptographic approaches. Therefore, designers must evaluate trade-offs between performance, cost, and security to create algorithms that meet operational demands without overburdening system resources [

90,

100].

While lightweight cryptographic algorithms are expected to be simpler and faster than conventional schemes, they may offer reduced security margins [

50].

Figure 5 illustrates the typical trade-offs in designing such algorithms. Enhancing security through longer keys, additional rounds, or added integrity checks increases computational demand and latency. High-speed encryption may require additional memory for storing intermediate values or lookup tables. Conversely, memory-optimized schemes reduce speed due to serialized processing. Parallelization improves throughput but consumes more area and power. Similarly, minimizing latency through higher clock rates increases energy consumption. In hardware implementations, higher throughput often results in increased gate count, while minimizing area generally reduces performance.

Several strategies are used to optimize lightweight cryptographic designs:

These approaches help ensure acceptable security while remaining deployable on constrained hardware platforms. The choice of design technique is often guided by the application context, requiring careful trade-off decisions among competing metrics.

5. Survey of Lightweight Encryption Techniques

Building upon the cryptographic requirements, performance metrics, and design considerations presented in

Section 4, this section provides a structured survey of lightweight encryption techniques tailored for UAV platforms. These techniques are designed to meet the stringent resource constraints of UAVs while ensuring essential security services such as confidentiality, integrity, and authentication [

101].

UAVs operate in dynamic and often adversarial environments, where reliable and secure communication is critical to mission success. Due to limited processing power, energy reserves, and onboard memory, traditional encryption schemes are often impractical. In response, lightweight cryptography has emerged as a viable solution for protecting UAV data exchanges without imposing significant performance overhead.

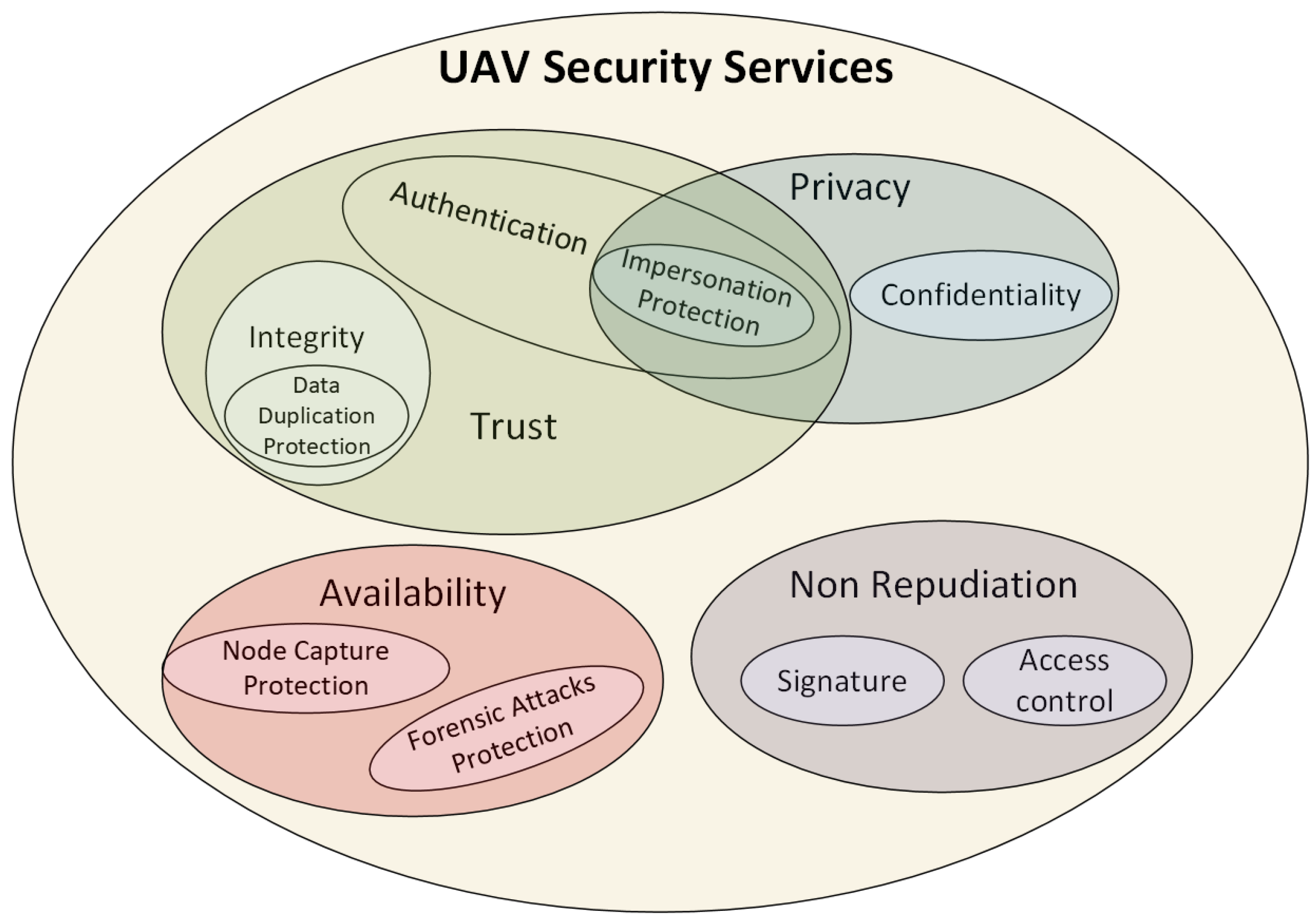

To secure UAV communications, a comprehensive suite of cryptographic services must be in place. As shown in

Figure 6, the core services include confidentiality, integrity, authentication, nonrepudiation, and availability. Additionally, UAV systems must be resilient against targeted threats such as node capture, impersonation, data duplication, and forensic attacks. Properly selected lightweight cryptographic primitives form the basis for defending against such vulnerabilities [

64,

102].

At the core of cryptographic security lies the use of keyed algorithms, which rely on secret values for encryption and decryption. These algorithms fall into two broad categories: symmetric key cryptography and asymmetric key cryptography. Symmetric algorithms use a single shared key for both encryption and decryption, making them computationally efficient and well-suited for constrained platforms. They support confidentiality, data integrity, and authentication, although secure key distribution remains a challenge. This limitation is often addressed by pre-sharing keys through trusted mechanisms. In contrast, asymmetric algorithms use separate public and private keys, offering greater flexibility for tasks such as digital signatures and key exchange, but at the cost of higher computational complexity [

64,

96].

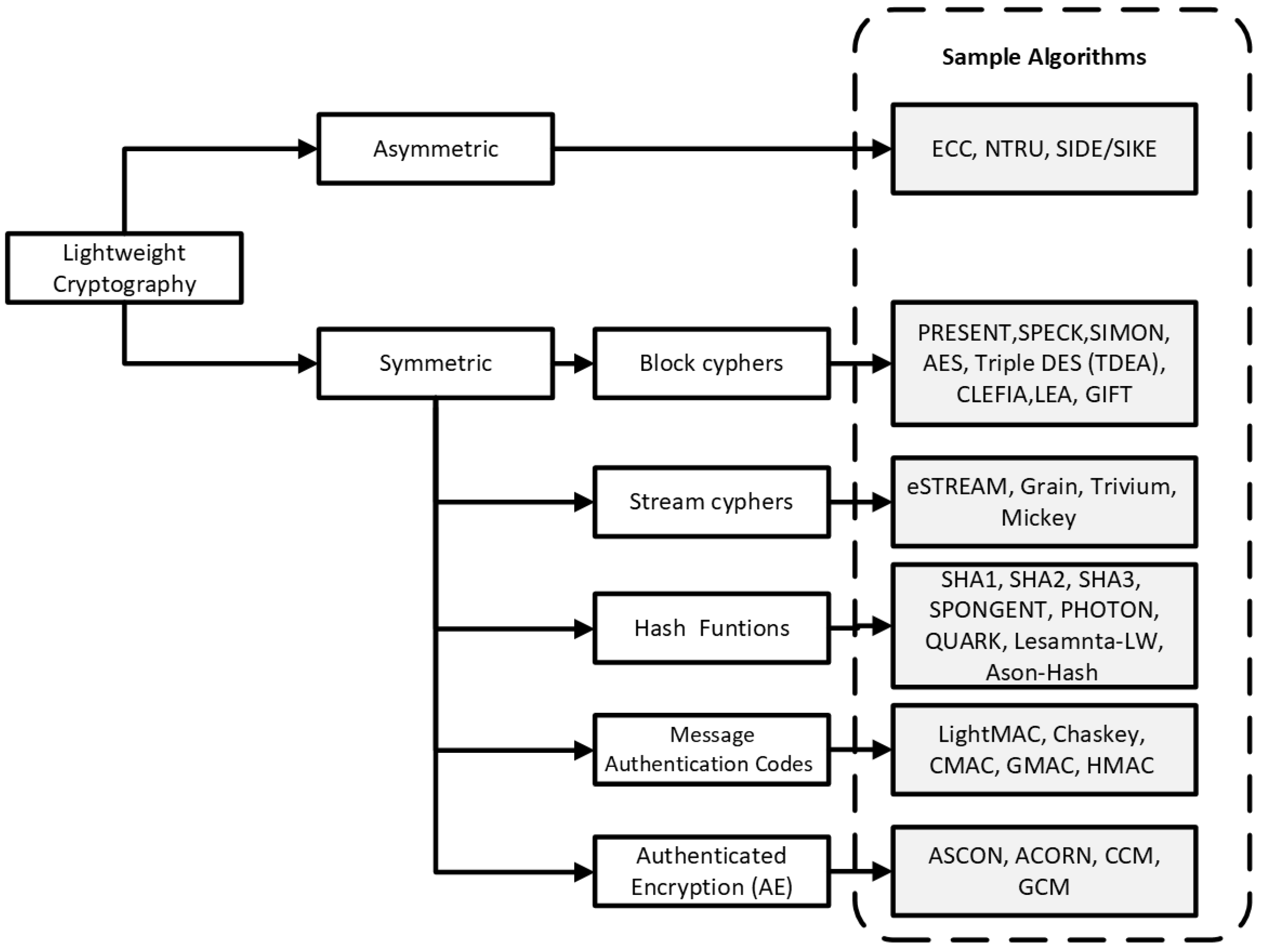

In symmetric lightweight cryptography, a range of primitives has been developed to achieve specific security objectives while minimizing resource usage. These primitives are tailored for constrained environments like UAV platforms, where computational and energy efficiency is critical. As illustrated in

Figure 7, the primary categories include:

Lightweight Block Ciphers (LWBC): Designed for encrypting fixed-size blocks of data with minimal overhead.

Lightweight Stream Ciphers (LWSC): Operate on continuous data streams and are well-suited for real-time encryption tasks.

Lightweight Hash Functions (LWHF): Ensure data integrity and are commonly used in digital signature schemes and authentication protocols.

Lightweight Message Authentication Codes (MACs): Authenticate messages and verify their origin using minimal computational resources.

Lightweight Authenticated Encryption (AE): Provide combined confidentiality and integrity in a single operation [

91,

102,

103].

5.1. Lightweight Block Ciphers

Block cipher cryptography is grounded in two core principles: confusion and diffusion. Confusion aims to obscure the relationship between the ciphertext and the encryption key, typically achieved through substitution operations such as S-boxes. Diffusion, on the other hand, spreads the influence of individual plaintext bits across the ciphertext using permutation mechanisms [

53,

96,

104,

105]. In a block cipher, encryption and decryption are performed on fixed-size data blocks, generally 64 bits or larger [

96].

Figure 8 categorizes block ciphers based on their internal structures, including Substitution-Permutation Networks (SPNs), Feistel Networks, Generalized Feistel Networks (GFNs), Add-Rotate-XOR (ARX) architectures, Nonlinear Feedback Shift Register (NLFSR)-based designs, and hybrid models. Examples of widely used ciphers within these categories include AES (SPN), DES (Feistel), TWINE (GFN), IDEA (ARX), KeeLoq (NLFSR-based), and the Hummingbird family (hybrid) [

53,

96].

Each architectural model presents unique design advantages and trade-offs. SPNs apply iterative substitution and permutation layers, which facilitate efficient serialization and minimal datapath widths [

53,

96]. A notable example is PRESENT [

57], a highly compact SPN cipher developed for embedded systems. It incorporates 31 lightweight rounds, each consisting of a substitution layer, a permutation layer, and round key integration [

106].

Feistel networks operate by dividing input data into halves, applying a round function to one half, and recombining the result with the other half through XOR operations. While this structure increases hardware cost slightly, it simplifies decryption by mirroring the encryption process. The Generalized Feistel Network (GFN) extends this model by partitioning input into multiple sub-blocks, enhancing flexibility and allowing for diverse round functions and shifting patterns.

ARX-based ciphers utilize only modular addition, bitwise rotation, and XOR operations. These primitives enable fast and compact implementations but are generally less scrutinized in terms of cryptanalytic robustness. AES-128, for instance, has been adapted into a compact software form that uses processor registers to store the internal state and the mix column step, while storing the key in RAM. This implementation requires approximately 1659 bytes of ROM and 4557 cycles to encrypt a 128-bit block [

53,

107].

NLFSR-based ciphers, which originate from stream cipher structures, are predominantly used in hardware implementations. Their security depends on nonlinear feedback shift register configurations commonly analyzed in stream cipher design. Hybrid architectures combine features from multiple cipher structures to optimize specific performance or security metrics. The effectiveness of these designs is determined by the selection and integration of component mechanisms [

53,

96].

5.2. Stream Ciphers and Real-Time Encryption

Stream ciphers are symmetric encryption algorithms that process data as a continuous stream, encrypting bit by bit or word by word rather than in fixed-size blocks. This design enables high-speed and low-latency encryption, making stream ciphers particularly well-suited for resource-constrained environments. Unlike block ciphers, which leverage both confusion and diffusion properties, stream ciphers primarily employ confusion through simple operations such as bitwise XOR [

96]. As a result, they are generally less complex, easier to implement in hardware, and more efficient in scenarios where processing power and energy are limited.

Lightweight stream ciphers typically generate keystreams using structures such as Linear Feedback Shift Registers (LFSRs) or Nonlinear Feedback Shift Registers (NLFSRs). These designs support high-speed and low-power operations, making them ideal for use in wireless networks and mobile platforms, including UAVs [

108].

The theoretical foundation of stream ciphers is based on the one-time pad (OTP) model, which offers perfect secrecy when a truly random keystream of the same length as the plaintext is used [

109]. However, the challenges of generating and securely distributing such keystreams have led to the adoption of pseudorandom keystream generators. In lightweight stream ciphers, encryption is performed by XORing the plaintext with a pseudorandom keystream derived from a secret key and initialization vector (IV). While this method offers efficiency, it also introduces vulnerabilities such as key reuse and synchronization issues, necessitating robust key and IV management strategies. Despite these challenges, stream ciphers remain a strong candidate for real-time encryption in UAV systems, where data is transmitted continuously and low latency is essential.

To promote the development of secure and efficient stream ciphers, the eSTREAM project was launched under the European Network of Excellence in Cryptology II [

110]. The project evaluated 34 candidate algorithms and selected a portfolio of ciphers suitable for deployment in both software and hardware-constrained environments. Two implementation profiles were defined: Profile 1 targeted high-throughput software ciphers, including Salsa20/12, Rabbit, LEX, and SOSEMANUK; Profile 2 focused on compact hardware implementations, featuring Grain, Trivium, and MICKEY 2.0. These ciphers were benchmarked on microcontroller platforms and extensively analyzed in the context of wireless sensor networks. While some candidates were disqualified due to security vulnerabilities, the remaining finalists demonstrated resilience against all known attacks exceeding brute-force complexity [

109].

Among the selected ciphers, Trivium and Grain are notable for their lightweight hardware design and strong efficiency. Trivium [

60], standardized under ISO/IEC 29192-3:2012, is a synchronous, bit-oriented cipher utilizing 80-bit keys and IVs. It employs three interdependent shift registers to achieve nonlinearity, maintaining a minimal hardware footprint of approximately 749 gate equivalents (GE), while also offering reasonable software performance. However, its simplicity makes it susceptible to certain fault injection attacks.

Grain [

61] combines both LFSR and NFSR components to generate a secure keystream. It features a bit-oriented architecture and produces between 1 and 32 bits per cycle, depending on configuration. Grain-128a, an enhanced version, supports 128-bit keys and allows for adjustable authentication tag sizes, making it suitable for applications requiring both confidentiality and integrity [

108,

109].

Salsa20 [

111], a Profile 1 finalist, was developed for efficient software encryption and uses modular addition, XOR, and bit rotation operations. It supports 256-bit keys and 128-bit IVs, with variants such as Salsa20/8, Salsa20/12, and Salsa20/20 offering trade-offs between performance and security. Although it performs well in software, its relatively large hardware footprint limits its applicability in highly constrained systems. ChaCha [

112], a variant of Salsa20, enhances diffusion and cryptographic strength and is widely adopted due to its speed and robustness.

MICKEY 2.0 (Mutual Irregular Clocking KEYstream generator) employs irregularly clocked Galois LFSRs and NFSRs to improve keystream randomness. It supports 80-bit keys and variable IVs, offering secure encryption with a higher implementation complexity of over 3000 GE. The extended version, MICKEY-128 2.0, supports larger keys and improved throughput but has also shown vulnerability to related-key and fault injection attacks [

108]. Despite such limitations, these ciphers continue to serve as reference benchmarks for real-time secure communication in UAV networks and other resource-limited systems.

5.3. Asymmetric Encryption

Asymmetric cryptography, also known as Public Key Cryptography (PKC), plays a critical role in securing communication within networked systems such as UAVs. Unlike symmetric encryption, which uses a single shared key, PKC employs a key pair consisting of a public key for encryption and a private key for decryption. These keys are generated using mathematical functions designed to make it computationally infeasible to derive the private key from the public one [

64]. This cryptographic paradigm supports essential security services, including confidentiality, data integrity, authentication, non-repudiation, availability, and access control [

64,

96]. In practical implementations, a sender encrypts data using the recipient’s public key, while digital signatures are created with the sender’s private key and verified using the corresponding public key [

96].

Despite its robustness, asymmetric cryptography presents challenges in resource-constrained environments. Operations often involve large key sizes and computationally intensive arithmetic over algebraic structures, with operands reaching lengths of thousands of bits. These requirements can strain the limited processing, memory, and energy resources of UAV platforms [

64,

113].

Among existing PKC schemes, Elliptic Curve Cryptography (ECC) is widely considered the most suitable for constrained systems. ECC achieves comparable security to classical methods such as RSA, while requiring significantly smaller key sizes, reduced memory footprint, and lower computational load. It is commonly adopted for key exchange, digital signature generation, and authentication in lightweight environments, and is standardized under ISO/IEC 29192 [

113].

The efficiency of ECC in constrained settings is enabled through implementation-specific optimizations. Although ECC itself is not inherently lightweight, lightweight elliptic curve cryptography (ECLC) leverages design decisions across protocol, algorithm, architecture, and circuit levels to meet performance and energy constraints. These optimizations include using efficient point representations (such as projective or mixed coordinates), selecting specialized curve models (including Koblitz, Edwards [

114], and Montgomery curves [

115]), and tailoring implementations to the underlying hardware [

64].

A notable extension of ECC in the lightweight cryptography domain is Identity-Based Encryption (IBE), which simplifies key management by deriving public keys from unique identifiers (e.g., email addresses). In contrast to RSA, where key pairs are generated independently, IBE enables a public key to be deterministically generated from an identity string, while the corresponding private key is issued by a trusted authority. The Boneh-Franklin IBE scheme, one of the earliest and most influential constructions, employs elliptic curve cryptography and uses Weil pairing to achieve chosen ciphertext security under the elliptic curve variant of the Computational Diffie-Hellman assumption [

116]. To improve resilience and decentralization, this scheme can also support threshold cryptography for distributed key generation without requiring a centralized master key.

To further adapt IBE for resource-limited platforms such as UAVs, lightweight variants like IBE-Lite have been introduced [

117]. IBE-Lite retains the core functionality of identity-based public key derivation and secure private key distribution while minimizing computational and memory demands. Built upon the ECC framework, it provides a practical and secure public key infrastructure alternative for embedded and low-power environments.

5.4. Post-Quantum Cryptography

Classical cryptographic systems are built on the computational hardness of problems such as the Integer Factorization Problem (IFP), the Discrete Logarithm Problem (DLP), and the Elliptic Curve Discrete Logarithm Problem (ECDLP). However, the development of quantum computing poses a significant threat to these systems. Algorithms such as Shor’s and Grover’s, when implemented on a sufficiently powerful quantum computer, can efficiently break traditional encryption and key exchange mechanisms. In response, the field of post-quantum cryptography (PQC)—also referred to as quantum-resistant or quantum-safe cryptography—has emerged as a critical area of research to ensure secure communication in the quantum era [

118,

119].

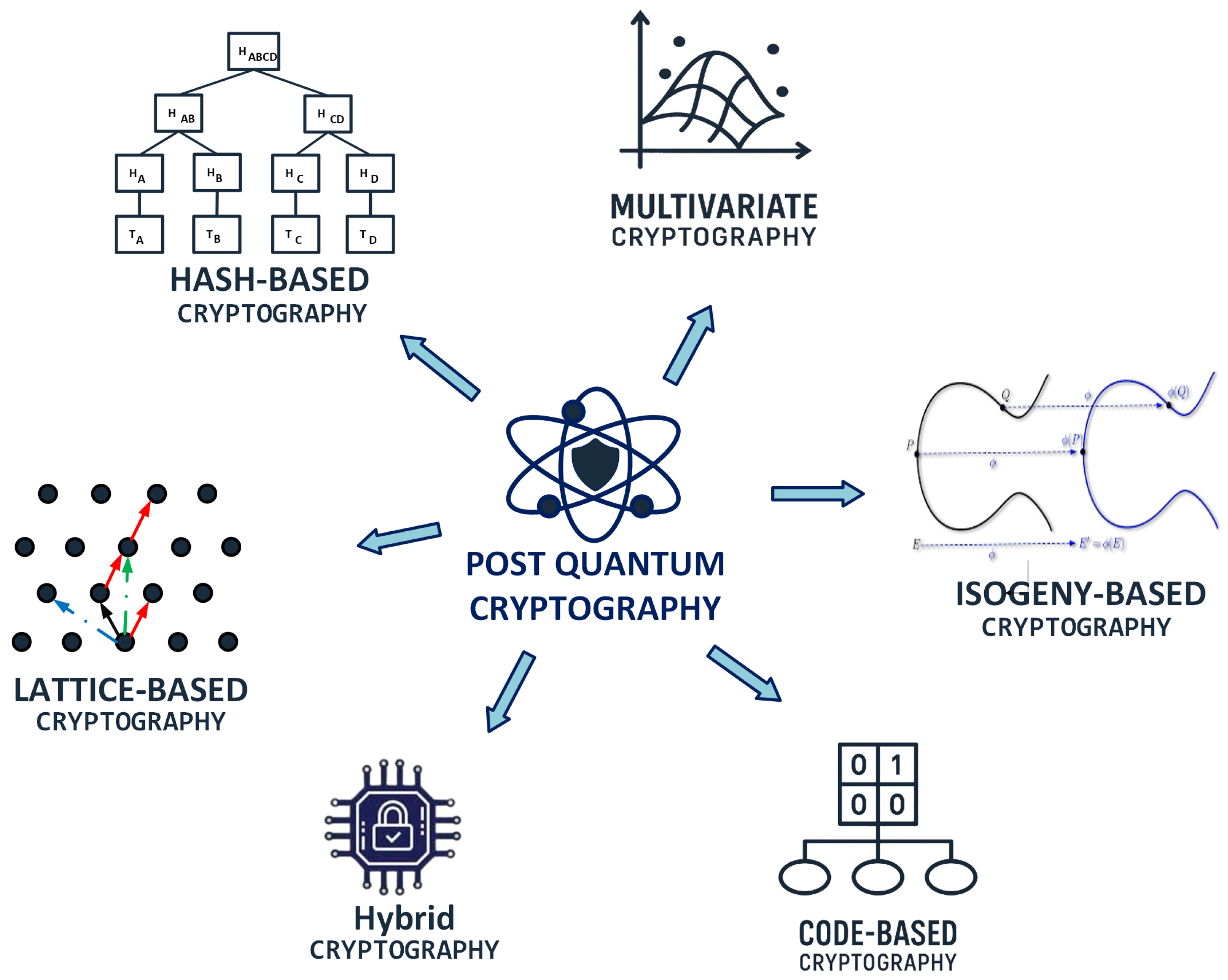

As illustrated in

Figure 9, PQC encompasses five primary categories of cryptographic schemes: code-based, lattice-based, hash-based, isogeny-based, and multivariate-based cryptosystems.

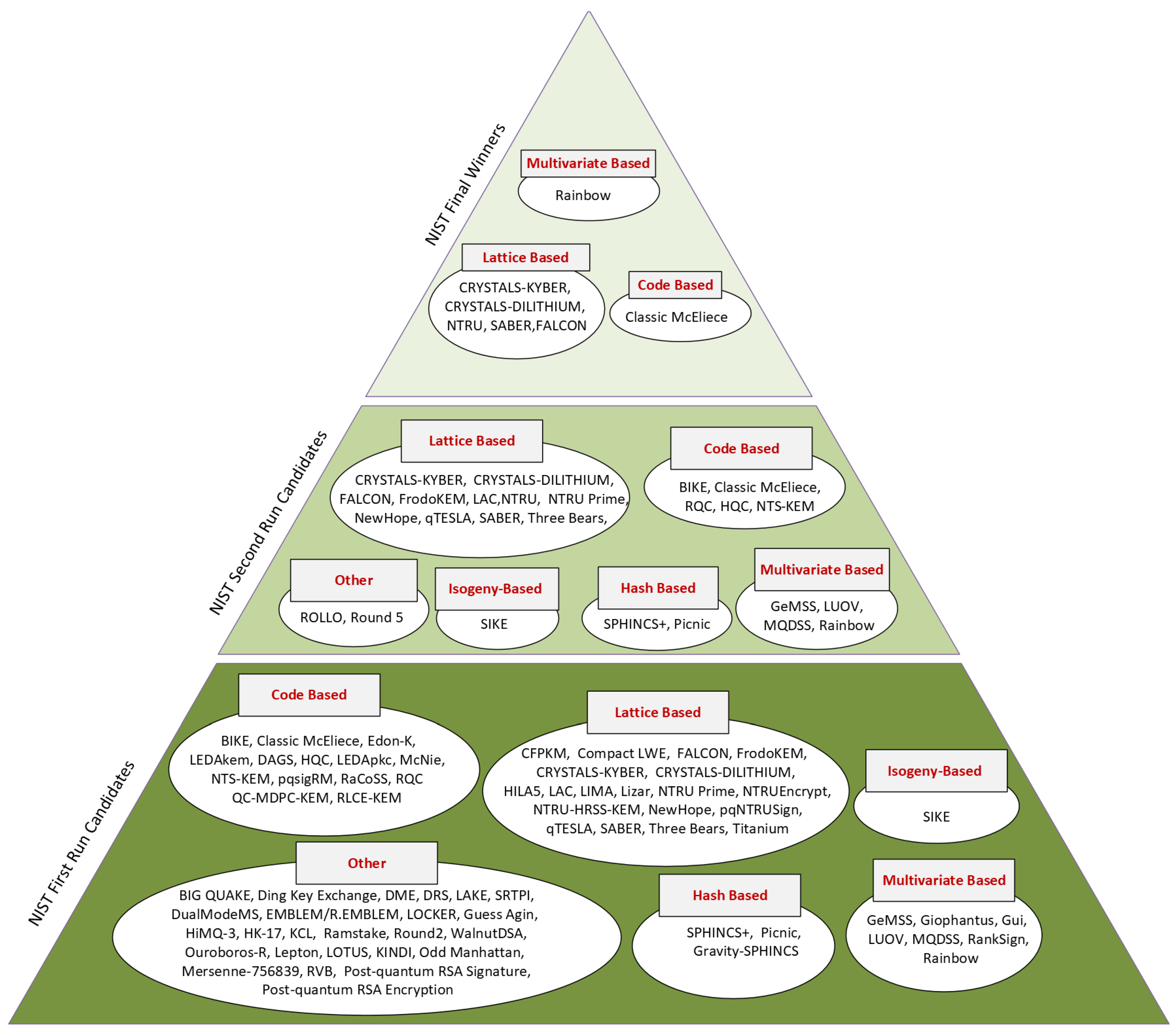

To identify viable quantum-resistant algorithms, the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) launched a multi-round standardization effort. The process began in 2017 with 69 algorithm submissions. Through successive rounds of evaluation—focused on robustness, performance, and implementation feasibility—a subset of algorithms advanced to the final stages. By the conclusion of Round 3 in 2022, NIST had selected a set of finalists and alternate candidates for future standardization [

120]. Although not all candidates are suitable for resource-limited platforms such as UAVs, the selected algorithms have undergone extensive public scrutiny and represent the most promising approaches for real-world deployment [

121].

Figure 10 presents an overview of the algorithms evaluated throughout the competition, organized by cryptographic category. Many of these schemes remain unsuitable for UAVs due to their computational and memory requirements.

The following subsections provide a brief overview of the major classes of PQC schemes and their applicability to UAV platforms [

119,

122].

Code-Based Cryptosystems: These systems are grounded in the use of error-correcting codes. Security is achieved by deliberately introducing errors into messages, rendering them unintelligible without a private decoding key [

123]. A canonical example is the McEliece cryptosystem [

124], which uses a structured code (e.g., a Goppa code [

125]) that is scrambled to produce a public key. The private key consists of the unscrambled, structured version, known only to the recipient [

126,

127]. McEliece is attractive for UAV applications due to its fast encryption and decryption, but suffers from very large key sizes—often exceeding 100 KB—posing significant storage and transmission challenges. Research efforts have explored more compact alternatives, such as low-density parity-check (LDPC), moderate-density parity-check (MDPC), and quasi-cyclic variants [

121].

Lattice-Based Cryptosystems: These systems rely on the hardness of problems like the Shortest Vector Problem (SVP) and Learning with Errors (LWE), defined over multidimensional lattices [

126,

128]. Lattice-based schemes are considered among the most promising for quantum resistance due to their strong security proofs and relatively efficient implementations. However, key and ciphertext sizes remain a concern. Compared to code-based cryptography, they require less storage but still impose nontrivial computational costs. Leading candidates such as NTRU [

129] and NewHope [

130] offer a favorable balance between security and efficiency. Signature schemes based on the Short Integer Solution (SIS) problem have also shown promise, though most remain in early testing stages on constrained hardware. UAV-specific adaptations may benefit from compression techniques and optimized hardware-aware implementations [

121].

Hash-Based Cryptosystems: These systems use the cryptographic properties of hash functions—namely, collision resistance and pre-image resistance—to build secure digital signature schemes [

123,

126]. Hash-based signatures typically generate one-time-use secret keys from a master key and organize them using tree-based structures, such as Merkle trees [

131,

132]. While highly secure and resistant to quantum attacks, such systems require careful management of key states and may involve large tree structures. Stateless variants reduce the risk of key reuse but come with increased computational overhead. Although hash-based signatures are computationally lightweight, their implementation complexity and management requirements have limited adoption in UAVs [

133].

Multivariate Cryptosystems: Multivariate public-key schemes are based on the difficulty of solving systems of multivariate polynomial equations over finite fields [

122]. These systems use simple operations like addition and multiplication, making them computationally attractive for constrained environments [

126]. Well-known schemes include Hidden Field Equations (HFE) [

134] and Unbalanced Oil and Vinegar (UOV), which have been applied in both encryption and signature protocols. Despite their efficiency, multivariate cryptosystems often involve large public keys and ciphertexts, which can limit practical deployment in UAVs. Variants like Rainbow, QUARTZ, QUAD, and Tame Transformation Signatures (TTS) have demonstrated success on low-power devices, but key sizes remain a challenge. For example, a Rainbow implementation with parameters

yields a public key size of approximately 22,680 bytes [

7,

121]. Compression techniques and parameter tuning are essential for making these schemes viable for UAV systems.

Isogeny-Based Cryptosystems: Isogeny-based cryptography leverages the mathematical properties of isogenies, or structure-preserving maps between elliptic curves [

135]. Supersingular elliptic curves, which lack a commutative endomorphism ring, offer strong resistance to quantum attacks [

136]. The Supersingular Isogeny Key Encapsulation (SIKE) protocol has been among the most studied candidates in this category [

126,

137]. While isogeny-based schemes are appealing due to their relatively small key sizes, they often require intensive computations and are sensitive to side-channel and fault injection attacks. These limitations present challenges for deployment on UAV platforms with tight power and timing constraints [

121].

Hybrid Cryptosystems: Hybrid approaches combine classical and post-quantum algorithms to provide defense-in-depth during the transition period. For example, Google’s CECPQ1 and CECPQ2 protocols integrated post-quantum key exchange alongside traditional TLS mechanisms. Although hybrid systems offer an additional layer of protection, they are often not suitable for UAVs due to the increased computational and memory demands required to run two cryptographic systems concurrently [

121].

According to Fernandez-Carames and Fraga-Lamas [

121], the most promising post-quantum cryptographic candidates for UAVs are code-based and lattice-based schemes. Most code-based proposals are derived from McEliece or Niederreiter structures, often using quasi-cyclic enhancements. In contrast, lattice-based approaches typically rely on solving the Learning with Errors (LWE) or Learning with Rounding (LWR) problems, and offer a favorable balance between security and implementation feasibility for lightweight platforms.

6. Key Management Techniques

While cryptographic primitives, including lightweight symmetric ciphers and post-quantum algorithms, serve as the foundation of secure communication, their effectiveness in UAV systems depends significantly on the management of cryptographic keys. Key management is a critical challenge in securing UAV communication networks due to their dynamic topologies, limited resources, and susceptibility to adversarial attacks. The secure distribution, renewal, and storage of cryptographic keys directly influence the confidentiality, integrity, and availability of UAV communications. This section presents a scientific overview of key management strategies, examining the strengths and limitations of pre-deployed (static) and dynamically distributed key schemes. It also highlights recent advances involving blockchain-based trust infrastructures and Physical Unclonable Functions (PUFs), which offer promising directions for lightweight and tamper-resistant key provisioning.

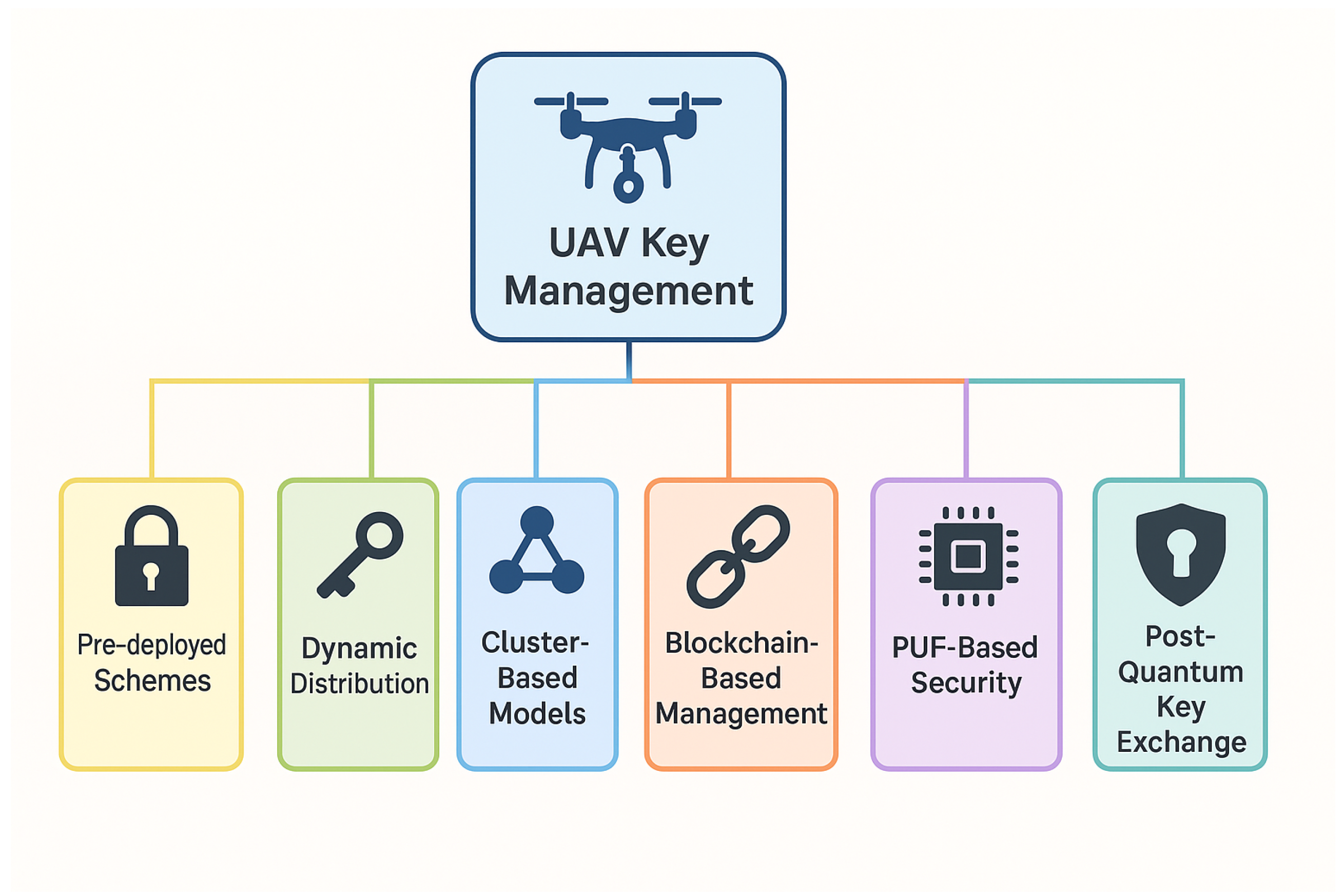

Figure 11.

Overview of key management strategies in UAV networks.

Figure 11.

Overview of key management strategies in UAV networks.

6.1. Pre-Deployed vs. Dynamic Key Distribution

Pre-deployed key distribution schemes involve the assignment of cryptographic keys to UAVs prior to mission deployment. These keys may be distributed individually, hierarchically, or in clusters, and are typically stored on the UAV’s onboard memory. The primary advantage of static schemes lies in their simplicity and low computational overhead, making them suitable for missions with fixed network topologies or limited resource budgets. However, static approaches exhibit significant limitations in scalability, flexibility, and resilience. If a UAV is captured or compromised, all pre-shared keys stored on the device are at risk, potentially exposing the entire network to adversarial attacks [

7]. Furthermore, static keys lack forward secrecy and are particularly vulnerable to quantum computing threats, as they cannot be efficiently updated or replaced in response to evolving risks [

4].

In contrast, dynamic key distribution schemes generate and negotiate cryptographic keys during mission execution. These approaches support session-based or on-demand key establishment, often leveraging protocols such as Diffie-Hellman or Elliptic Curve Diffie-Hellman for secure key exchange [

138]. Dynamic schemes are inherently more adaptable to changes in network topology, enabling secure peer-to-peer communication in UAV swarms and ad hoc deployments. They also facilitate regular key refreshment, reducing the impact of key compromise and supporting forward secrecy. However, dynamic key distribution introduces additional computational and communication overhead, which may affect energy consumption and latency—critical considerations for UAV platforms with limited resources [

4].

Table 7 summarizes the key attributes of pre-deployed and dynamic key distribution approaches, highlighting their relative strengths and limitations in the UAV context.

In summary, while pre-deployed key distribution remains suitable for simple, static UAV missions, dynamic schemes are better suited for flexible and scalable network environments. The ability to adapt to topological changes, support forward secrecy, and refresh keys on demand makes dynamic key distribution increasingly essential in modern UAV networks. Furthermore, the integration of post-quantum cryptographic primitives is becoming a necessary enhancement to ensure resilience against quantum-era threats. The following subsections explore advanced techniques that enhance dynamic key management, including blockchain-based decentralization, hardware-rooted security primitives, and quantum-resistant protocols.

6.2. Cluster-Based and Hierarchical Key Management

Cluster-based and hierarchical key management strategies have gained significant traction in UAV networks due to their ability to balance scalability, efficiency, and security within dynamic and resource-constrained environments. In cluster-based approaches, UAVs are organized into logical groups or clusters, each managed by a designated cluster head responsible for key generation, distribution, and renewal within its domain [

139]. This structure reduces the complexity of key management by localizing key-related operations, thereby minimizing communication overhead and confining the impact of potential node compromise to individual clusters rather than the entire network [

140,

141].

Hierarchical key management extends this concept by introducing multiple layers of authority and responsibility. A typical architecture involves a two-tier structure, where the lower tier consists of cell or cluster groups managed by local leaders (such as mobile backbone nodes or cluster heads), and the upper tier comprises a control group or supernodes that oversee the overall network. This hierarchical arrangement enables efficient group key management and supports secure inter-cluster communication using group key agreement protocols and implicitly certified public keys. The main advantage of this approach is its ability to restrict the effects of membership changes, such as node join or leave events, to the relevant cluster, thus enhancing scalability and reducing the frequency and scope of costly rekeying operations [

142,

143].

Recent advancements have incorporated unsupervised learning and clustering algorithms to further optimize cluster formation and maintenance, enabling UAV networks to dynamically adapt to changing mission requirements and network topologies [

144]. For instance, agglomerative hierarchical clustering has been used to assign UAVs to clusters based on communication quality or mission objectives, ensuring that key management remains efficient even as the network evolves in real time.

Cluster-based and hierarchical schemes also facilitate the integration of advanced security features, such as distributed key agreement, resilience to node capture, and efficient lost key recovery. In denied or adversarial environments, these approaches have demonstrated the ability to maintain secure communication with minimal energy and bandwidth consumption, making them particularly suitable for large-scale UAV swarms and mission-critical applications [

145].

In summary, cluster-based and hierarchical key management architectures provide a robust foundation for scalable, resilient, and efficient key distribution in UAV networks. By localizing key operations and leveraging layered control, these schemes address many of the unique challenges posed by dynamic aerial environments, supporting both intra- and inter-cluster security with reduced overhead and enhanced adaptability.

6.3. Blockchain-Based Decentralized Key Management

Blockchain-based decentralized key management has emerged as a robust paradigm for enhancing the security, transparency, and scalability of UAV networks. Traditional centralized key distribution models are prone to single points of failure and scalability limitations, particularly in dynamic and adversarial environments. In contrast, blockchain leverages a distributed, immutable ledger to enable consensus-driven management of cryptographic operations, including key generation, distribution, and revocation [

9,

146].

In a blockchain-enabled UAV ecosystem, each UAV or ground station may function as a participating node in a private or consortium blockchain, validating and recording security-related transactions. This decentralized architecture eliminates dependency on centralized trust authorities and enhances resilience against impersonation, data tampering, and unauthorized access [

147]. Permissioned blockchain frameworks such as Hyperledger Fabric and Tendermint offer high throughput and low-latency performance, rendering them suitable for real-time UAV applications.

Several blockchain-based protocols have been proposed to address the unique constraints of UAV communication. Notably, the BETA-UAV scheme integrates smart contracts to automate mutual authentication between UAVs and ground control stations, effectively mitigating replay and spoofing attacks with minimal communication overhead [

10]. Other solutions implement group key management where a private blockchain ledger is used to orchestrate secure join/leave operations, distribute group keys, and enable key recovery upon node failure [

148]. These mechanisms ensure tamper-evident logging of security events and provide traceable, auditable key lifecycle management.

Beyond authentication, blockchain also supports decentralized identity frameworks. Each UAV can be assigned a unique digital identity anchored in the blockchain ledger, enabling transparent and verifiable trust relationships across multi-operator or cross-border deployments [

149]. Smart contracts further enhance autonomy by orchestrating key lifecycle tasks such as renewal, revocation, and recovery without manual intervention.

Performance evaluations suggest that lightweight, permissioned blockchain configurations can achieve latency and throughput levels compatible with aerial mission timelines [

9]. However, challenges persist regarding resource consumption, real-time consensus synchronization, and integration with PQC. Emerging research is exploring hybrid architectures that combine blockchain with AI/ML techniques for adaptive threat detection and self-healing key infrastructures [

147].

In summary, blockchain-based decentralized key management offers a scalable, tamper-resistant solution tailored to the operational and security requirements of UAV networks. As autonomous aerial systems grow in complexity and interconnectivity, blockchain is positioned to become a foundational enabler of secure, interoperable, and self-managing UAV ecosystems.

6.4. PUF-Based Secure Key Storage and Generation

Physical Unclonable Functions (PUFs) have emerged as a foundational technology for secure key storage and generation in UAV networks, addressing limitations associated with traditional cryptographic key management systems. PUFs exploit uncontrollable physical variations in integrated circuits to produce unique device-specific responses to external challenges. These responses are reproducible under controlled conditions but nearly impossible to clone or predict, making PUFs an effective basis for lightweight and tamper-resistant security solutions in resource-constrained UAV environments [

150,

151].

Unlike conventional approaches that store sensitive cryptographic keys in non-volatile memory, thereby exposing them to extraction through physical attacks, PUF-based systems derive keys dynamically from the hardware at runtime. During an initial enrollment phase, a set of challenge–response pairs (CRPs) is generated from the UAV embedded PUF and stored securely at the ground station (GS). When authentication or key derivation is needed, the GS transmits a challenge to the UAV, which computes the response using its PUF circuitry. The resulting transient key is reconstructed in real time, eliminating the need for persistent key storage and reducing susceptibility to physical compromise [

28,

152].

This architecture enhances several core security properties. First, tamper resistance is achieved by avoiding long-term storage of static secrets, making it infeasible for adversaries to extract usable key material from a captured node. Second, PUFs support forward secrecy by generating fresh keys for each session, ensuring that the compromise of one key does not retroactively endanger past communications. Third, the lightweight computational profile of PUF-based protocols makes them ideal for UAV platforms with limited processing power and battery capacity. Studies report that authentication latencies can be reduced to 214 μs using programmable switches—roughly twice as fast as CPU-bound methods - while also consuming up to 42% less energy than AES-128 under comparable security assumptions [

93,

151].

Recent PUF-based schemes combine physical uniqueness with cryptographic primitives to achieve robust and scalable key management. Hybrid PUF-hash models use functions such as SHA-3 to convert raw responses into uniform and collision-resistant key material, thereby improving entropy while obscuring hardware-specific noise. Lattice-based PUF designs have also been proposed to extend these methods to post-quantum key exchange, achieving 1,024-bit quantum-resistant security at energy costs as low as 18 mJ per exchange [

153,

154].

A summary of PUF defenses against common UAV attack vectors is provided in

Table 8. These systems resist node capture through volatile key derivation, withstand cloning due to their inherent physical randomness, and protect against eavesdropping with opaque, non-deterministic CRP mappings. Hardware tampering typically disrupts circuit behavior, rendering key generation invalid or unreliable.

Despite their advantages, PUF systems face challenges related to reliability and protocol design. Environmental factors—such as voltage fluctuations and temperature variations—can alter response stability. To mitigate this, error correction codes like BCH and Reed–Solomon are integrated to achieve bit error rates below

[

154]. Additionally, early PUF schemes (e.g., PLAKE, EV-PUF) demonstrated vulnerabilities such as key leakage and response collisions. These have been addressed in more recent protocols by incorporating adaptive CRP sets and authenticated encryption using lightweight standards such as ASCON-128a [

28,

93].

Standardization efforts are underway to formalize PUF evaluation criteria for UAV and aerospace systems. NIST’s Interagency Report 8420 aims to establish metrics to evaluate the reliability, uniqueness, and resistance of PUF to physical and logical attacks, thus supporting a greater adoption in secure UAV communication frameworks.

6.5. Post-Quantum Key Exchange Techniques

The emergence of quantum computing presents a substantial threat to classical cryptographic schemes that currently underpin UAV communication systems. Algorithms based on number-theoretic assumptions such as RSA, DSA, and Elliptic Curve Cryptography (ECC) are vulnerable to quantum attacks, particularly due to Shor’s algorithm, which can solve integer factorization and discrete logarithm problems in polynomial time. Given that many UAV key management protocols rely on these primitives, their long-term security is at risk as quantum computing becomes more viable.

PQC has been proposed as a class of cryptographic algorithms that remain secure in the presence of both classical and quantum adversaries. These include lattice-based, code-based, multivariate, hash-based, and isogeny-based families. Among them, lattice-based schemes such as Kyber, NewHope, and NTRU have demonstrated promise for UAV applications due to their efficiency, strong security proofs, and ongoing standardization through NIST’s Post-Quantum Cryptography project [

7]. Kyber and NTRU are Key Encapsulation Mechanisms (KEMs) that rely on the hardness of problems such as Learning With Errors (LWE) and Ring-LWE, which are believed to be resistant to quantum attacks.

In UAV environments, where energy efficiency, processing speed, and communication overhead are constrained, PQC protocols must be optimized for embedded implementation. Evaluations of Kyber and NewHope have shown that key exchange can be performed with latency under 10ms and memory usage below 32KB on embedded processors, while offering 128-bit post-quantum security levels [

8,

133]. Despite their cryptographic strength, code-based algorithms like Classic McEliece and BIKE present challenges in terms of key size, with public keys often exceeding several hundred kilobytes [

155].

To facilitate gradual migration, hybrid key exchange schemes that combine traditional algorithms (e.g., ECDH) with post-quantum primitives (e.g., Kyber) are being implemented to ensure backward compatibility and layered defense. These approaches enable resilience even if one algorithm is later broken, which is particularly useful in transitional environments like UAV networks [

156]. Additionally, quantum-resilient protocols for cross-domain authentication have been developed using PUF and lattice-based key exchanges, enabling robust identity verification in drone swarms and distributed aerial systems [

157].

Another area of active research involves quantum key distribution (QKD) protocols applied to UAVs. QKD enables information-theoretic security by leveraging quantum entanglement and the no-cloning theorem to generate shared secrets. Demonstrations of mobile QKD between moving aerial platforms have shown the feasibility of secure optical links under flight dynamics, though limitations remain in terms of range, environmental sensitivity, and hardware requirements [

158]. As UAVs transition into more secure and autonomous roles, QKD may complement PQC in high-assurance scenarios.

Performance comparisons of post-quantum techniques indicate that lattice-based protocols offer the most practical balance for UAV networks between computational efficiency and quantum resistance. The adoption of schemes like Kyber is accelerating, driven by NIST’s standardization and increasing availability of optimized embedded libraries [

133,

159]. Continued work in hardware acceleration, including GPU and FPGA-based implementations, further supports their real-world deployment [

127].

Building on the foundational role of key distribution and maintenance in secure UAV communications, it becomes essential to address how these cryptographic mechanisms integrate across the full communication stack.

7. Multilayer Security Framework