Submitted:

17 July 2025

Posted:

18 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

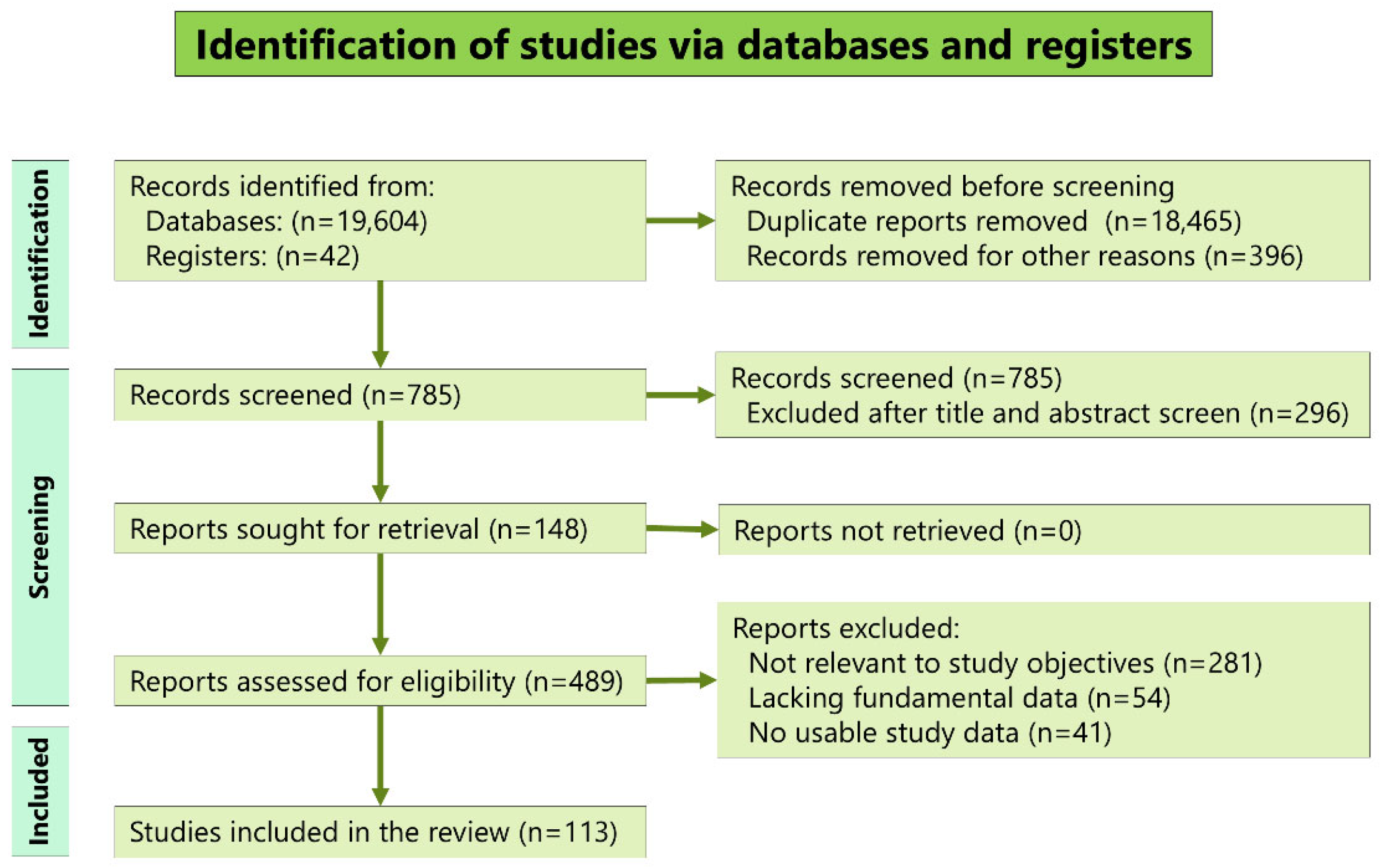

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Literature Review

2.2. Analysis

2.3. Statistics

3. Results

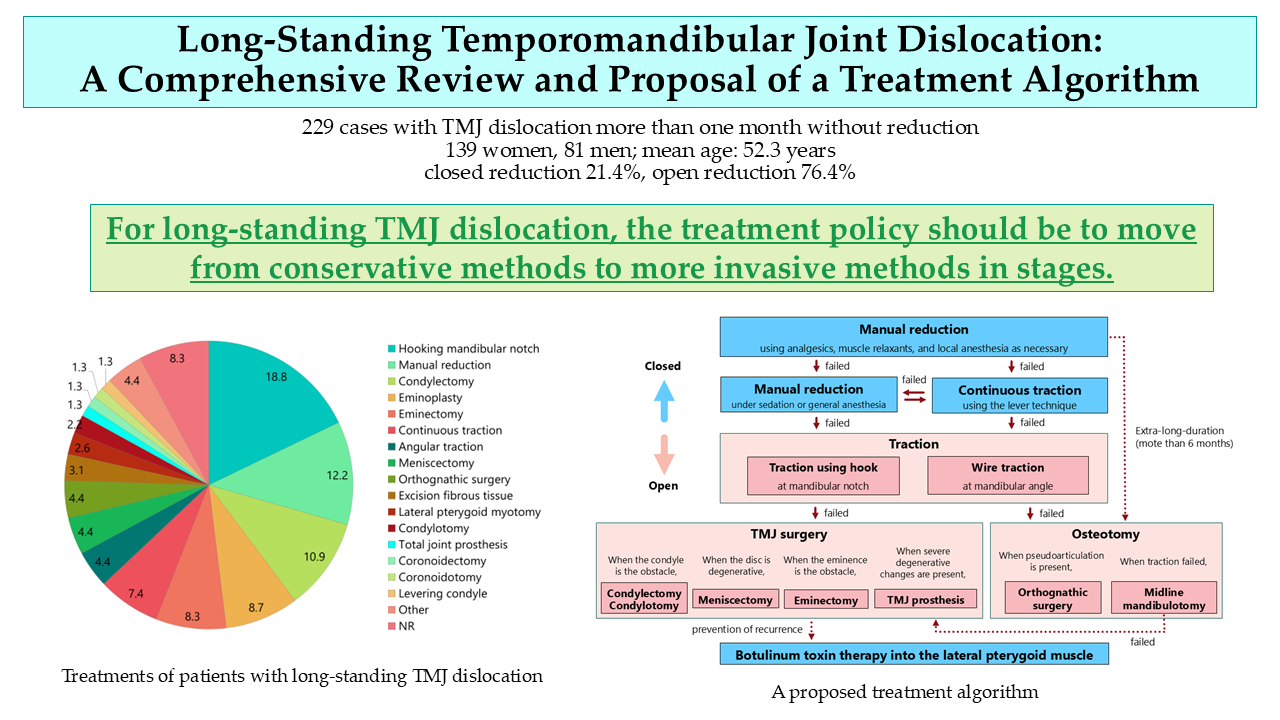

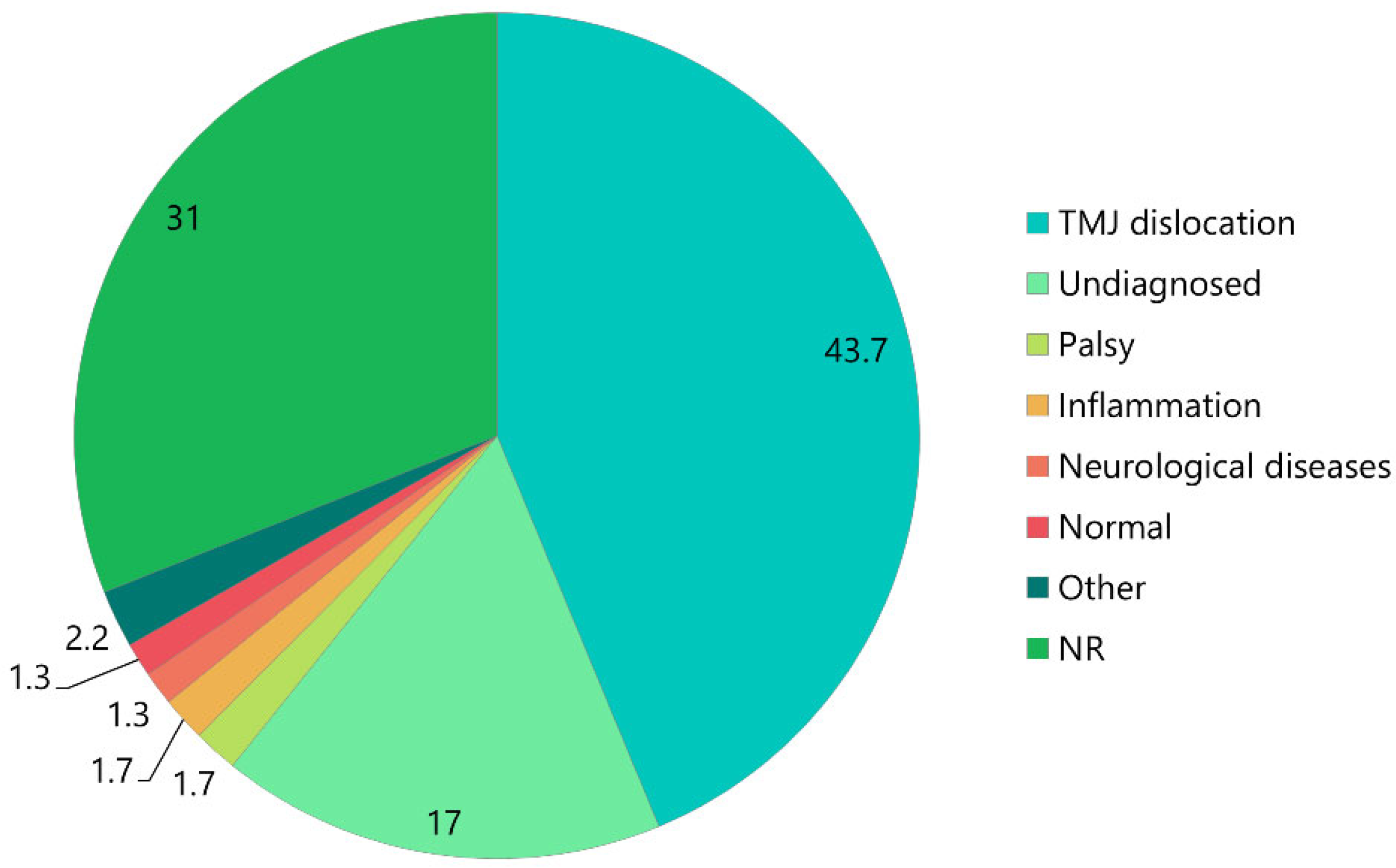

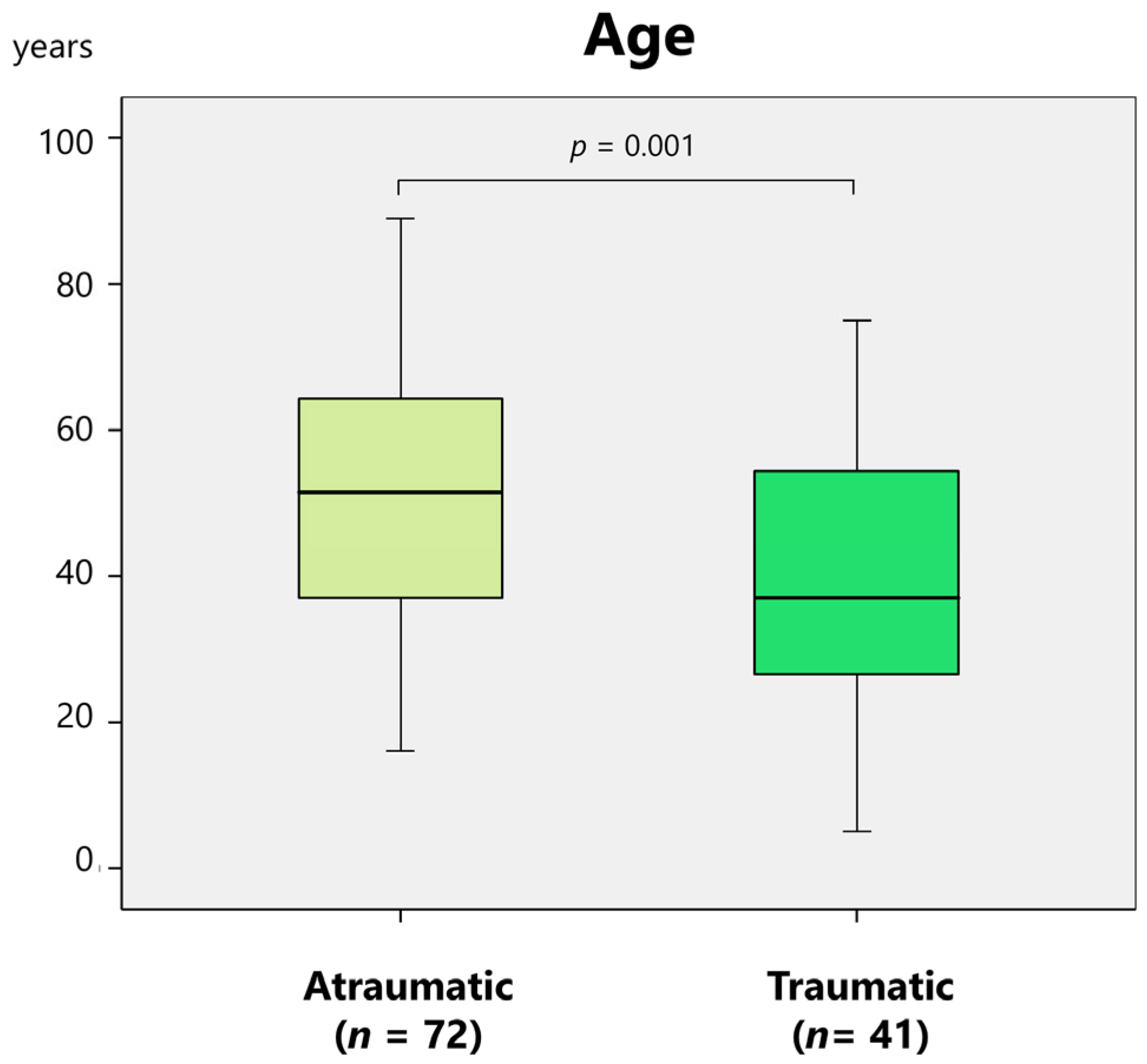

3.1. Demographic Data and Diagnoses

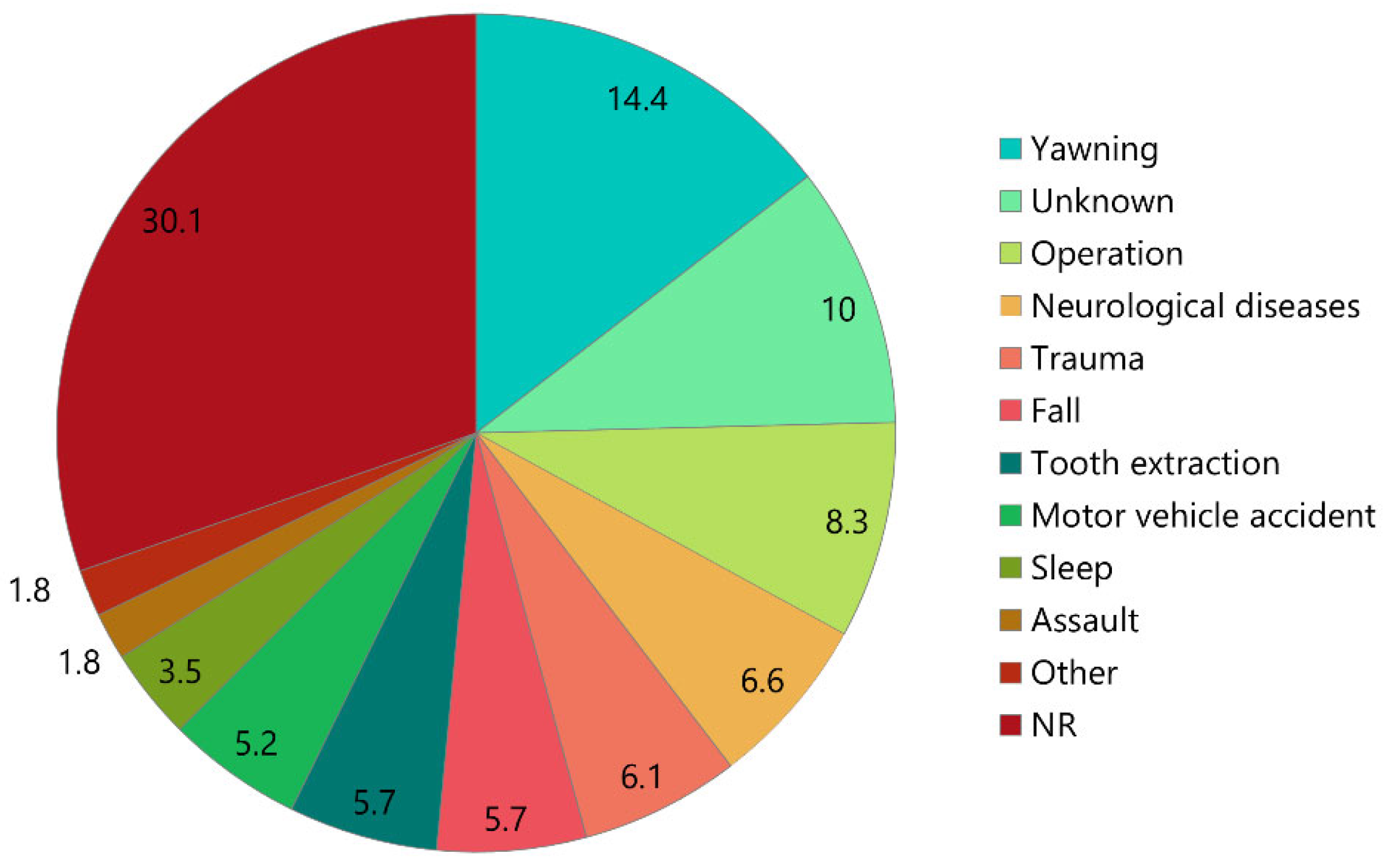

3.2. Symptoms and Etiology

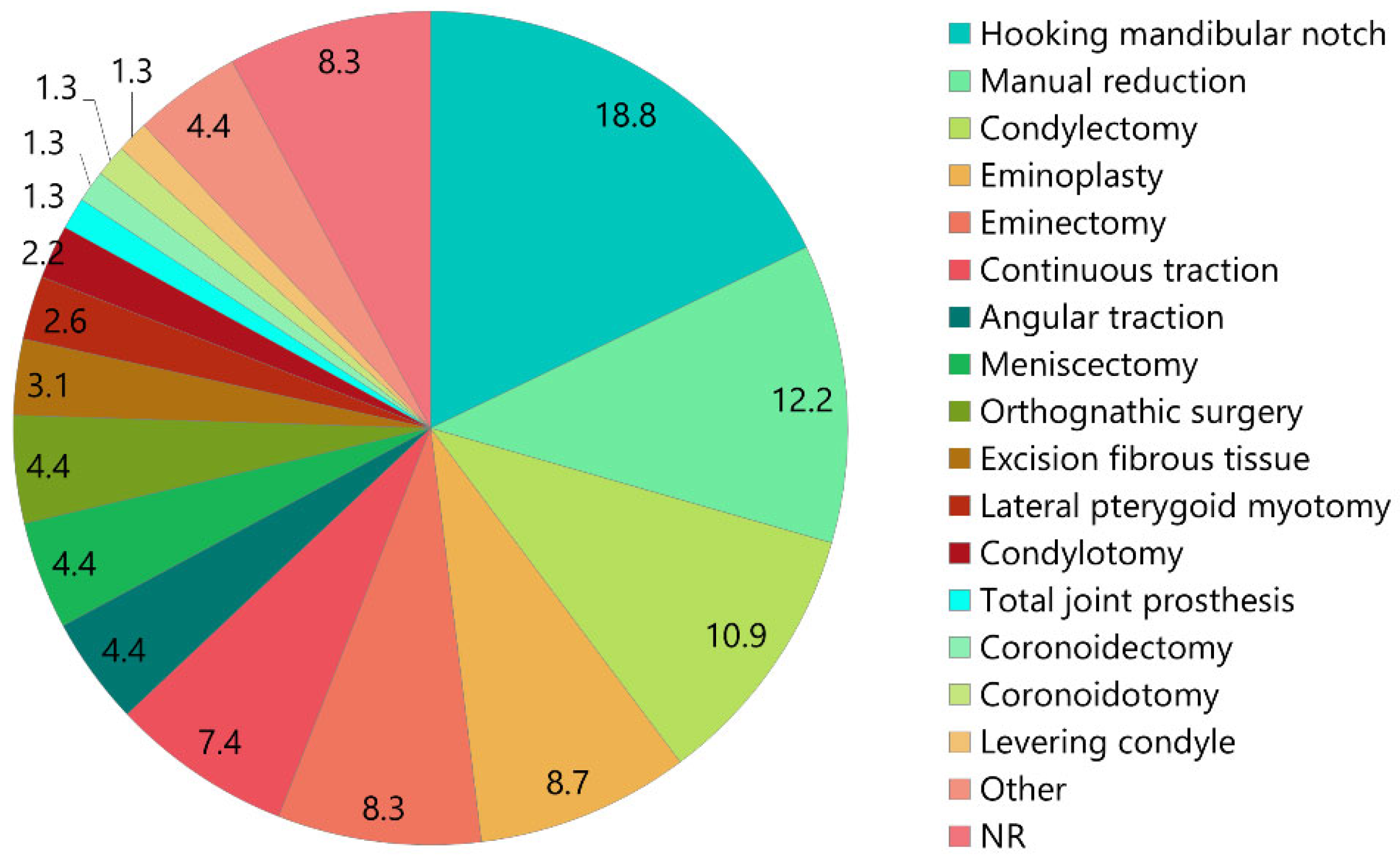

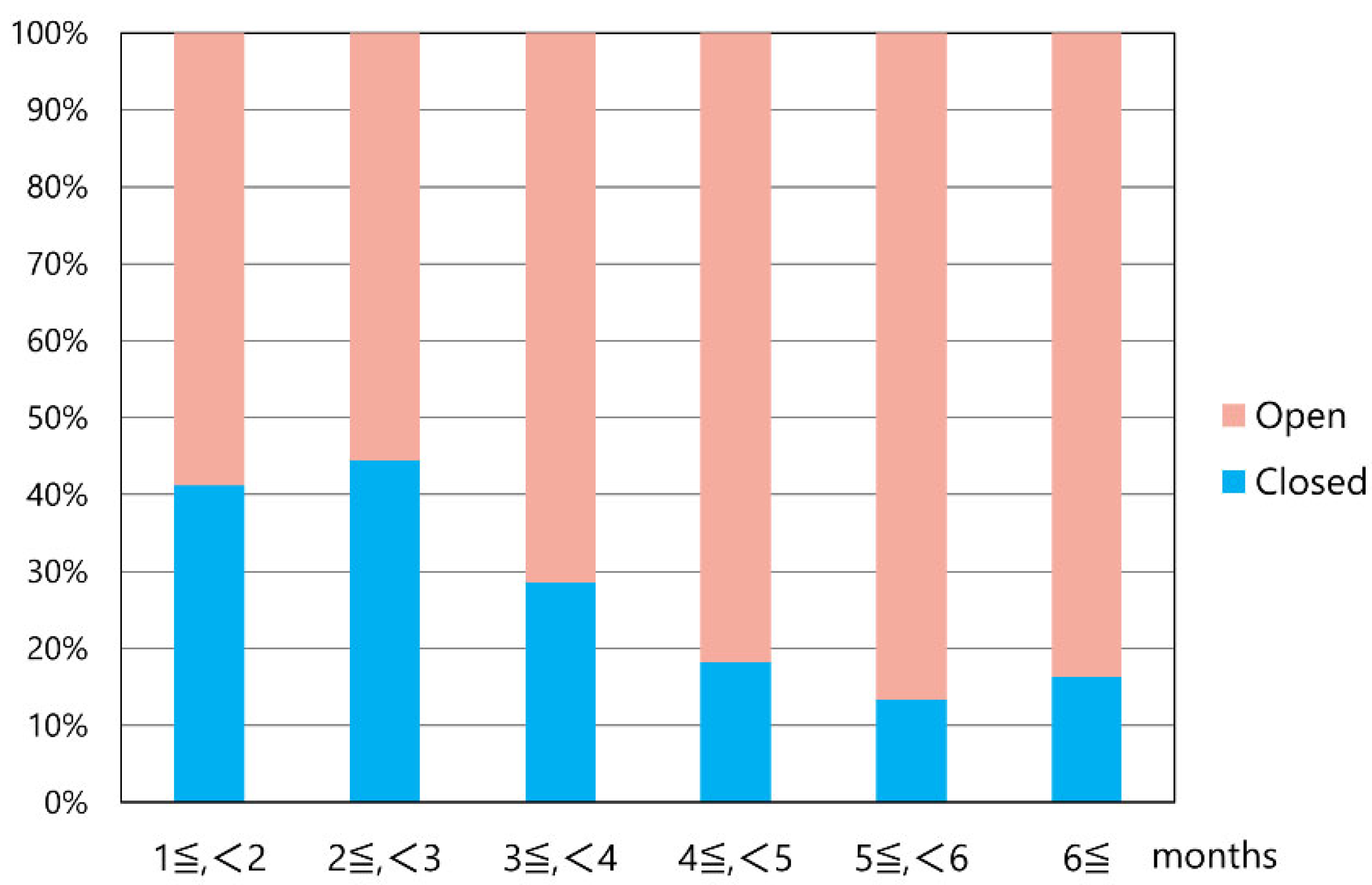

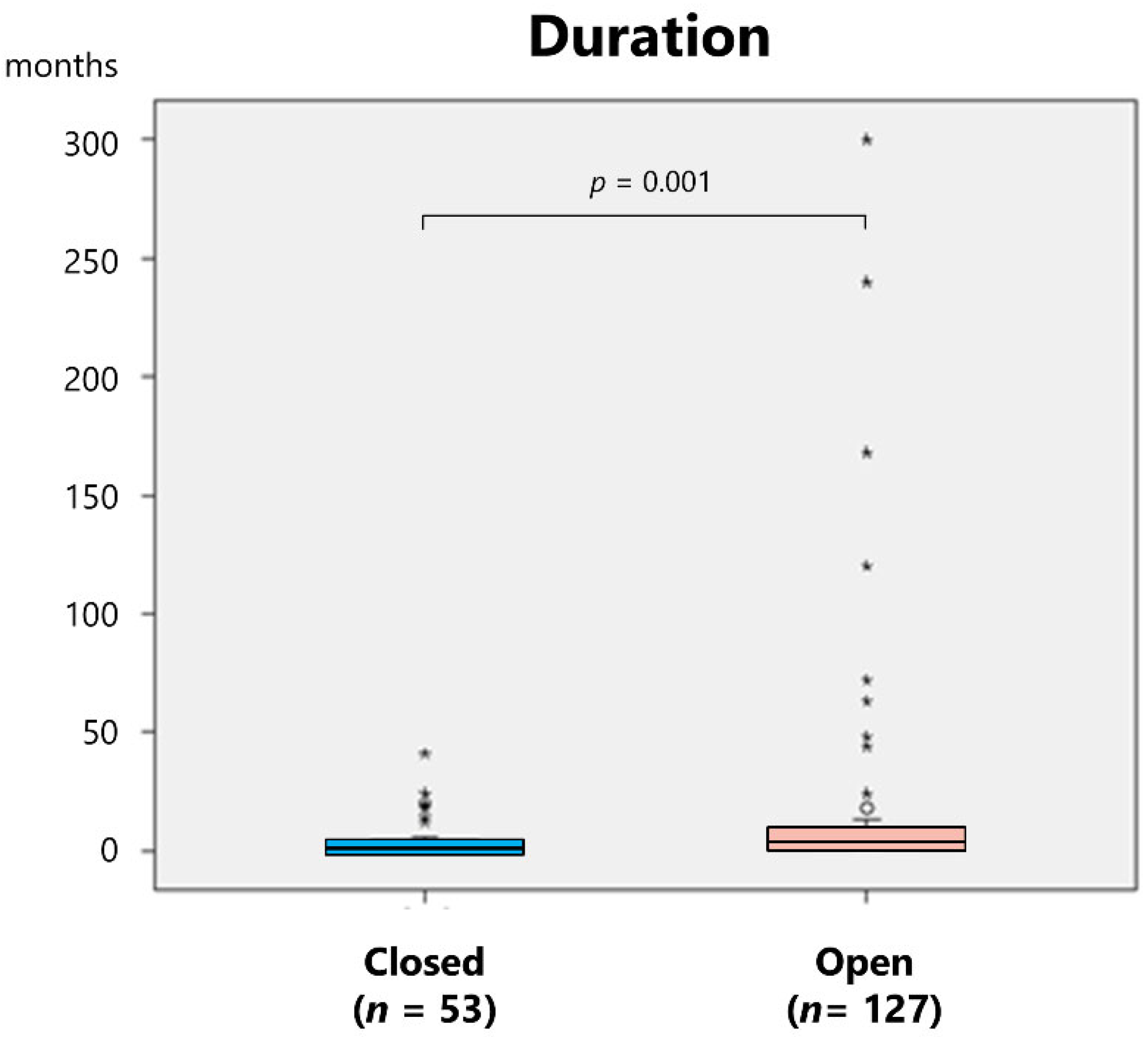

3.3. Treatments and Sequelae

4. Discussion

4.1. Etiology of Long-Standing TMJ Dislocation

4.2. Diagnosis of Long-Standing TMJ Dislocation

4.3. Treatment of Long-Standing TMJ Dislocation

4.4. Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BC | Before Christ |

| MRI | magnetic resonance imaging |

| NR | Not reported |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| TMJ | Temporomandibular joint |

References

- Neff, A.; Hell, B.; Kolk, A.; Pautke, C.; Schneider, M.; Prechel, U. S3 Leitlinie Kiefergelenkluxation; AWMF Registernummer 007-063; Arbeitsgemeinschaft der Wissenschaftlichen Medizinischen Fachgesellschaften e.V.: Berlin, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Neff, A.; McLeod, N.; Spijkervet, F.; Riechmann, M.; Vieth, U.; Kolk, A.; Sidebottom, A.J.; Bonte, B.; Speculand, B.; Saridin, C.; et al. The ESTMJS (European Society of Temporomandibular Joint Surgeons) consensus and evidence-based recommendations on management of condylar dislocation. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 5068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akinbami, B.O. Evaluation of the mechanism and principles of management of temporomandibular joint dislocation. Systematic review of literature and a proposed new classification of temporomandibular joint dislocation. Head Face Med. 2011, 7, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, F. The genuine works of Hippocrates. Translated from the Greek with a Preliminary Discourse and Annotations. Vol. 2, New York, William Wood and Company, 1886,pp107. https://www.google.co.jp/books/edition/The_Genuine_Works_of_Hippocrates/6BAWAAAAYAAJ?hl=ja &gbpv=1&dq=The+genuine+works+of+HIPPOCRATES,+Vol+2&printsec=frontcover.

- Daelen, B.; Thorwirth, V.; Koch, A. Neurogene Kiefergelenkluxation. Definition und Therapie mit Botulinumtoxin. Nervenarzt 1997, 68, 346–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, K. Botulinum neurotoxin injection for the treatment of recurrent temporomandibular joint dislocation with and without neurogenic muscular hyperactivity. Toxins 2018, 10, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shorey, C.W.; Campbell, J.H. Dislocation of the temporomandibular joint. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. Endod. 2000, 89, 662–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iizuka, T.; Hidaka, Y.; Murakami, K.-I.; Nishida, M. Chronic recurrent anterior luxation of the mandible: A review of 12 patients treated by the LeClerc procedure. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 1988, 17, 170–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Undt, G.; Kermer, C.; Piehslinger, E.; Rasse, M. Treatment of recurrent mandibular dislocation, part I: Leclerc blocking procedure. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 1997, 26, 92–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, K. Etiology of pneumoparotid: A systematic review. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 12, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, K. Superior dislocation of the mandibular condyle into the middle cranial fossa: A comprehensive review of the literature. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 3781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramer. Zur Behandlung der irreponiblen Unterkieferverrenkung. Centralblatt für Chirurgie. 1901, 28, 269. [Google Scholar]

- Hildebrand, O. Zur blutigen Reposition veralteter Kieferluxationen. Archiv für Klinische Chirurgie. 1902, 66, 352. [Google Scholar]

- Willcutts, M.D. Treatment of an irreducible dislocated lower jaw of 98 days’ duration. U. S. Navy Med. Bull. 1927, 25, 331–336. [Google Scholar]

- Miyakoda, T. Surgical reduction of chronic dislocation of the mandibular joint. Jpn. Surg. Soc. 1931, 1369–1370. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz, M. Unreduced unilateral dislocation of the jaw. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1940, 22, 176–181. [Google Scholar]

- Reiß, M. Operative Reposition veralterer doppel-seitiger Unterkieferluxationen. Zahnärztl. Rundsch. 1940, 49, 1235–1240, 1282–1285, 1309–1311. [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe, I.; Hagino, T. A case of chronic bilateral mandibular anterior dislocation successfully reduced by open reduction. Med. Biol. 1942, 1, 581–583. [Google Scholar]

- Müller, G.M. Long-standing dislocation of mandible. Br. Med. J. 1946, 1, 572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, J.C.B. Treatment of unreduced bilateral forward dislocation of the temporomandibular joint. Br. Dent. J. 1949, 86, 275–278. [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe, Y.; Otake, O. Unreduced dislocation of the mandibular joint following eclampsia. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Path. 1950, 3, 1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottlieb, O. Long-standing dislocation of the jaw. J. Oral Surg. 1952, 10, 25–32. [Google Scholar]

- Matsumae, G, Ito, I. A Case of nonsurgical reduction of chronic anterior dislocation of the mandible. J. Jpn. Stomatol. Soc. 1952, 1, 91–92. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, J.; White, T.C.; Anderson, H. A case of bi-lateral dislocation of the mandible of nine months duration. Dent. Record. 1952, 72, 230–239. [Google Scholar]

- Curson, I. Long-standing bilateral dislocation of the temporomandibular joints. Br. Dent. J. 1959, 107, 351–353. [Google Scholar]

- Whinery, J.G. Bilateral condylar neck dissection for long-standing dislocation of the mandible. J. Oral Surg. Anesth. Hosp. Dent. Serv. 1961, 19, 432–435. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Berg, A. Ein Fall einer veralteten, doppelseitigen Unterkieferrenkung. Zschr. Stomat. 1962, 24, 876. [Google Scholar]

- Litzow, T.J.; Royer, R.Q. Treatment of long-standing dislocation of the mandible. Staff Meet Mayo Clinic. 1962, 37, 399–403. [Google Scholar]

- Glahn, M. Malposition of the mandibular condyle. Br. J. Oral Surg. 1964, 2, 33–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogan N, Nally F. Prolonged bilateral temporomandibular joint dislocation. Irish Dent, 1964, 10: 40–42.

- Fordyce, GL. Long-standing bilateral dislocation of the jaw. Br. J. Oral Surg. 1965, 3, 222–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayward, J.R. Prolonged dislocation of the mandible. J. Oral Surg. 1965, 23, 585–594. [Google Scholar]

- Topazian, R.G.; Costich, E.R. Management of protracted dislocation of the mandible. J. Trauma. 1967, 7, 257–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kameyama, T.; Miura, T.; Moji, K. A case of chronic dislocation of the temporomandibular joint. Jpn. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 1968, 14, 17–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, Y.; Terai, H.; Nakashiro, T. Surgical reduction of chronic anterior dislocation of the temporomandibular joint. J. Jpn. Stomatol. Soc. 1970, 19, 234–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowe, P.F.; Caldwell, J.B. Correction of permanent temporomandibular joint dislocation. J. Oral Surg. 1970, 28, 222–226. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ohto, A.; Shimura, K.; Suzuki, K.; Amanai, S. A case of chronic dislocation of the temporomandibular joint. J. Kanagawa Odont. Soc. 1970, 4(3/4), 83.

- Okano, M.; Henomatsu, K.; Yoda, K.; Kawai, S. A case of open reduction of chronic temporomandibular joint dislocation. Jpn. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 1971, 17, 356. [Google Scholar]

- Sujaku, C.; Kameyama, T.; Hosino, N. A case of long-standing forward dislocation of the mandible. Jpn. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 1972, 18, 593–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horii, M.; Murata, A.; Ikeda, S.; Kashiwagi, A.; Ishii, Y. A case of obsolute luxation of jaw joint for 6 years. Kitano Hospital J. Med. 1973, 18, 88–90. [Google Scholar]

- Rawls, H.C.; Bruni, A.; Hamilton, M.K. Surgical correction of the permanently dislocated mandible. J. Oral Surg. 1973, 31, 385–388. [Google Scholar]

- Gorman, J.M. Condylotomy for bilateral dislocation. Br. J. Oral Surg. 1974, 12, 96–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashimoto, K.; Kawachi, S.; Murase, H.; Akashi, Y.; Masuda, M.; Ohtani, T. Two cases of obsolete bilateral dislocation of the temporomandibular joints. Jpn. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 1976, 22, 423–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adekeye, E.O.; Shamia, R.I.; Cove, P. Inverted L-shaped ramus osteotomy for prolonged bilateral dislocation of the temporomandibular joint. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Path. 1976, 41, 568–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, B.; Schneider, J.; Given, J. Prolonged dislocation of the mandibular condyle. J. Oral Surg. 1979, 37, 346–348. [Google Scholar]

- Littler, B.O. The role of local anaesthesia in the reduction of long-standing dislocation of the temporomandibular joint. Br. J. Oral Surg. 1980, 18, 81–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawamura, H.; Takano, N.; Abe, Y.; Kikuchi, M.; Fujita, Y.; Hayashi, S. A case of chronic bilateral dislocation of the temporomandibular joint treated by nonsurgical reduction. Jpn. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 1980, 29, 341–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizuno, A.; Fujita, S.; Shimada, T.; Sekiyama, S. Long-standing luxation of the mandible, report of a case and review of the Japanese literature. Int. J. Oral Surg. 1980, 9, 225–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabhakara, B.S. Conservative treatment of bilateral persistent anterior dislocation of the mandible. J. Oral Surg. 1980, 38, 51–52. [Google Scholar]

- Stakesby Lewis, J.E. A simple technique for reduction of long-standing dislocation of the mandible. Br. J. Oral Surg. 1981, 19, 52–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blank DM, Stein AC, Gold BD, Berger J. Treatment of protracted bilateral mandibular dislocation with Proplast-Vitallium prostheses. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. 1982, Apr;53(4):335–339. [CrossRef]

- Tipps, S.P.; Landis, C.F. Prolonged bilateral mandibular dislocation. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 1982, 40, 524–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parekh PK, Bhatia IK. Condylectomies for prolonged bilateral temporomandibular dislocation. Arch. Orthop. Trauma Surg. (1978). 1983, 102, 123–125, 1978. [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, T.; Tamura, H.; Ioku, N. Two cases of obsolete dislocation of the temporomandibular joint. Jpn. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 1984, 30, 1708–1715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudo, K.; Baba, Rie. ; Chen, C-H.; Komai, T.; Fujioka, Y.; Kanamori, T. Restricting operation of anterior movement for obsolete dislocation of temporomandibular joint: a case report. Jpn. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 1985, 31, 337–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Attar, A.; Ord, R.A. Longstanding mandibular dislocations: report of a case, review of the literature. Br Dent J 160:91, 1986.

- Wijmenga, J.P.; Boering, G. Blankestijn, J. Protracted dislocation of the temporomandibular joint. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 1986, 15, 380–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammersley, N. Chronic bilateral dislocation of the temporomandibular joint. Br. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 1986, 24, 367–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzuki, S.; Mizuno, A.; Torii, S.; Kamiya, H.; Katayama, T.; Yokoi, C.; Shikimori, M.; Motegi, K. Eminectomy for long-standing bilateral forward dislocation of the temporomandibular joint: Report of two cases. Jpn. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 1987, 33, 386–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowaka, S.; Hosoda, M.; Segami, N.; Hata, T.; Hanafusa, H.; Fujimura, K.; Fukuda, M. A case of long-standing bilateral dislocation of the mandibular condyle. Jpn. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 1987, 33, 2131–2135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obara, S.; Oka, M.; Harada, T.; Yoshimura, Y. A case of long-standing dislocation of the temporomandibular joint with severe complications. Jpn. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 1988, 34, 716–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin RS, Gropp H, Beirne OR. Long-standing mandibular dislocation: report of a case. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 1988, 46, 693–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanimoto, Y.; Morizane, T.; Hadano, T.; Yoshiga, K.; Takada, K. The chronic bilateral anterior dislocation of the temporomandibular joint (TMJ): Report of a case. J. Jpn. Soc. TMJ. 1991, 3, 69–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishihara, A.; Mizuno, K.; Kamiya, Y.; Ito, A.; Imai, T.; Adachi, M.; Yamashita, T.; Fukaya, M. Reduction of obsolete dislocation of temporomandibular joint: Report of a case. Jpn. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 1992, 38, 500–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishimaru, T.; Hayatsu, Y.; Ohsawa, S.; Shinozaki, F. A case of prolonged mandibular dislocation of the patient medicated with antipsychotic drugs. J. Jpn Stomatol. Soc. 1992, 41, 504–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogawa, T.; Mori, M.; Sawatari, S.; Yamamoto, Gaku. ; Yamaguchi, Y.; Yoshitake, K. A case of open reduction for long-standing anterior luxation of the temporomandibular joint. Jpn. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 1992, 38, 1927–1928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith WP, Johnson PA. Sagittal split mandibular osteotomy for irreducible dislocation of the temporomandibular joint. A case report. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 1994, 23, 16–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawakami, T.; Tsuzuki, M.; Shohara, E.; Takayama, K.; Morimoto, Y.; Sugimura,M. Surgical treatment by Dautrey procedure for long-standing anterior luxation of the temporomandibular joints. J. Jpn. Soc. TMJ. 1995, 7, 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, M.; Isobe, M.; Kamiya, Y.; Ohtani, T. Two cases of obsolete dislocation of the temporomandibular joint with cerebrovascular disease. J. Jpn. Soc. Dent. Medically Compromised Patient. 1996, 5, 30–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwatsubo, R.; Hosaka, H.; Goto, K.; Murayama, T. Treatment of temporomandibular joint luxation in patients with complications. –Case report–. J. Jpn. Soc. Dent. Medically Compromised Patient. 1996, 4, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurita K, Mukaida Y, Ogi N, Toyama M. Closed reduction of chronic bilateral temporomandibular joint dislocation. A case report. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 1996, 25, 422–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caminiti, M.F.; Weinberg, S. Chronic mandibular dislocation: The role of non-surgical and surgical treatment. J. Can. Dent. Assoc. 1998, 64, 484–491. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hoard MA, Tadje JP, Gampper TJ, Edlich RF. Traumatic chronic TMJ dislocation: report of an unusual case and discussion of management. J. Craniomaxillofac. Trauma. 1998, 4, 44–47. [Google Scholar]

- Mizutani, H.; Hattori, H.; Senga, K.; Seko, K.; Asahina, T.; Kaneko, R.; Shinoda, M.; Ueda, M. Eight cases with chronic mandibular dislocation. J. Jpn. Soc. TMJ. 2000, 12, 52–56. [Google Scholar]

- Murakami, K.; Kondo, T.; Irisa, K.; Takahashi, K.; Kishida, T.; Itoh, T. J. J. Jpn. Soc. Dent. Medically Compromised Patient. 2002; 11, 41–46. [CrossRef]

- Takenaka, A.; Fujita, H.; Sasaki, H.; Tanabe, S.; Matsuda, S.; Yoshimura, Y. A case of old anterior temporomandibular joint dislocation treated by lysis and lavage using arthroscopic technique and manual reduction. J. Jpn. Soc. TMJ. 2003, 15, 29–32. [Google Scholar]

- Aquilina, P.; Vickers, R.; McKellar, G. Reduction of a chronic bilateral temporomandibular joint dislocation with intermaxillary fixation and botulinum toxin A. Br. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2004, 42, 272–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohno, K.; Sumitomo, S.; Mouri, K.; Kuwajima, K.; Takai, Y. Chronic dislocation of temporo-mandibular joint reset by closed reduction with intra-articular pumping technique. J. Jpn. Soc. TMJ. 2005, 17, 215–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayakawa, M.; Kamei, K.; Sato, T.; Nakamura, M.; Ito, K.; Kobayashi, K. A case of bilateral chronic dislocation of the temporomandibular joint reduced by removal of fibrous adhesive lesions after eminectomy. Jpn. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2005, 51, 212–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terakado, N.; Shintani, S.; Nakahara, Y.; Yano, J.; Hino, S.; Hamakawa, H. Conservative treatment of prolonged bilateral mandibular dislocation with the help of an intermaxillary fixation screw. Br. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2006, 44, 62–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Debnath SC, Kotrashetti SM, Halli R, Baliga S. Bilateral vertical-oblique osteotomy of ramus (external approach) for treatment of a long-standing dislocation of the temporomandibular joint: A case report. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. Endod. 2006, 101, e79–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee SH, Son SI, Park JH, Park IS, Nam JH. Reduction of prolonged bilateral temporomandibular joint dislocation by midline mandibulotomy. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2006, 35, 1054–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, M.; Nakayama, S.; Yoshihama, Y.; Mese, H.; Sasaki, A. Conservative reduction of obsolete dislocation of the temporomandibular joint –A case report: Innovation for a patient with severe marginal periodontitis–. J. Jpn. Soc. TMJ. 2007, 19, 171–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rattan, V.; Rai, S. Management of long-standing anteromedial temporomandibular joint dislocation. Asian J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2007, 19, 155–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakashima, M.; Yano, H.; Akita, S.; Tokunaga, K.; Anraku, K.; Tanaka, K.; Hirano,A. Traumatic unilateral temporomandibular joint dislocation overlooked for more than two decades. J. Craniofac Surg. 2007, 18, 14661470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kale, T.P.; Kotrashetti, S.M.; Janardhan, S.; Urolagin, S.B. Long standing TMJ dislocation: closed reduction –A case report and technical note. J. Int. Oral Health. 2010, 2, 59–67. [Google Scholar]

- Huang IY, Chen CM, Kao YH, Chen CM, Wu CW. Management of long-standing mandibular dislocation. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2011, 40, 810–814. [CrossRef]

- Shakya, S.; Ongole, R.; Sumanth, K.N.; Denny, C.E. Chronic bilateral dislocation of temporomandibular joint. Kathmandu Univ Med J (KUMJ). 2010, 8, 251–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C-H. ; Kim, D-H. Chronic dislocation of temporomandibular joint persisting for 6 months: a case report. J. Korean assoc. Maxillofac. Surg. 2012, 38, 305–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rattan, V.; Rai, A.; Sethi, A. Midline mandibulotomy for reduction of long-standing temporomandibular joint dislocation. Craniomaxillofac. Trauma Reconstr. 2013, 6, 127–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshida, M.; Shibayama, N.; Kondo, E.; Ogami, J.; Takekawa, M.; Matsuda, M. A case of chronic mandibular dislocation treated by conservative reduction. Jpn. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2013, 59, 18–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baur, D.A.; Jannuzzi, J.R.; Mercan, U.; Quereshy, F.A. Treatment of long term anterior dislocation of the TMJ. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2013, 42, 1030–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmorsy, K.A. Management of long-standing temporomandibular joint dislocation. Egypt J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2014, 5, 39–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayashi, K.; Onda, T.; Ogane, S.; Yakushiji, T.; Ohata, H.; Takano, N.; Shibahara, T. A case of long standing dislocation of bilateral temporomandibular joints of the elderly. J.J. Gerodont. 2014, 28, 284–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saikia, D. Long standing temporomandibular joint dislocation: a case report. IOSR-JDMS, 2014, 13, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, L.; Jaisani, M.R.; Sagtani, A.; Win, A. Conservative management of chronic TMJ dislocation: An old technique revived. J. Maxillofac. Oral Surg. 2015, 14 (Suppl 1), A267–S270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogawa, M.; Kanbe, T.; Kubota, F.; Makiguchi, T.; Miyazaki, H.; Yokoo, S. Conservative reduction by lever action of chronic bilateral mandibular condyle dislocation. Cranio. 2015, 33, 142–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arzul L, Henoux M, Marion F, Corre P. Luxation chronique bilatérale des articulations temporo-mandibulaires et syndrome de Meig. Rev. Stomatol. Chir. Maxillofac. Chir. Orale. 2015, 116, 106–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marqués-Mateo, M.; Puche-Torres, M.; Iglesias-Gimilio, M.E. Temporomandibular chronic dislocation: The long-standing condition. Med. Oral Patol. Oral Cir. Bucal. 2016, 21, e776–e783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeyaraj, P.; Chakranarayan, A. A conservative surgical approach in the management of longstanding chronic protracted temporomandibular joint dislocation: A case report and review of literature. J. Maxillofac. Oral Surg. 2016, 15 (Suppl 2), S361–S370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Güngörmüş, M.; Yavuz, M.S.; Ömezli, M.M.; Akkaş, İ. Long-term temporomandibular joint dislocation treated with bilateral eminectomy and chin-cap; Case report. Turkiye Klinikleri J. Dental Sci. Cases. 2016, 2, 75–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negishi, S.; Shibasaki, M. A case of long-standing bilateral temporomandibular joint dislocation treated by intraoral condylectomy. Jpn. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2017, 63, 304–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, K.; Debnath, S.C.; Adhyapok, A.K.; Hazarika, K. Long-standing temporomandibular joint dislocation: A rare experience. Saudi J. Oral Sci. 2017, 4, 112–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaban, S.D.; Sohal, K.S.; Moshy, J.R. A novel technique for surgical reduction of long-standing temporomandibular joint dislocation. Int. J. Head Neck Surg. 1: (3). [CrossRef]

- Dhiman, N.K.; Pandey, A.; Vishwakarma, A.K.; Verma, V.; Singh, S. Management of long standing TMJ dislocation: Report of three cases. J. Adv. Med Dent Sci. Res. 2018, 6, 55–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, S.Y.; Berahim, N.B.; Andan, K.B.; Ramasamy, S.N. Delayed management of unrecognized bilateral temporomandibular joint dislocation: A case report. Craniomaxillofac. Trauma. Reconstr. 2018, 11, 145–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholami, M.; Shirzadeh, A.; Khalife, H. Chronic long-standing temporomandibular joint dislocation: Report of three cases and review of literature. J Maxillofac Oral Surg. 2018, 17, 502–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segami, N.; Nishimura, T.; Miyaki, K.; Adachi, H. Tethering technique using bone screws and wire for chronic mandibular dislocation: a preliminary study of refractory cases. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2018, 47, 1065–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balaji, S.M.; Balaji, P. Surgical management of chronic temporomandibular joint dislocations. Indian J. Dent. Res, 4: 29. [CrossRef]

- Güven, O. Nearthrosis in true long-standing temporomandibular joint dislocation; a report on pathogenesis and clinical features with review of literature. J. Craniomaxillofac. Surg. 2019, 47, 945–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuevas Queipo de Llano, A.; Monje Gil, F.; Gonzalez García, R.; Villanueva Alcojol, L.; Gonzalez Ballester, D. Long-term dislocation of the mandible: Is there an algorithm to success? intraoperative decision and review of literature. J. Maxillofac. Oral Surg. 2020, 19, 12–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karakida, K.; Takahashi, M.; Hamada, Y.; Aoki, J.; Hoshimoto, Y. A case of long-standing temporomandibular joint dislocation: Restoration of oral function following condylectomy. Tokai J. Exp. Clin. Med. 2020, 45, 152–155. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sarlabous, M.; Psutka, D.J. Total joint replacement after condylar destruction secondary to long-standing dislocation of the temporomandibular joint. J. Craniofac. Surg. 2020, 31, 989–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bavia, P.F.; Ganjawalla, K.; Keith, D.A. Long-standing unilateral temporomandibular joint (TMJ) dislocation with pseudo articulation with the base of the skull. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. Cases. 2020, 6, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uetsuki, R.; Ono, S.; Tada, M.; Okuda, S.; Takechi, M. Long-standing temporomandibular joint dislocation treated by intraoral condylectomy: a case report and review of the literature. J. Med. Case Rep. 2022, 16, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikunj, A.; Khan, N.; Rajkhokar, D.; Mishra, B.; Rajurkar, S. Deg-induced oromandibular dystonia presenting as chronic temporomandibular joint dislocation: a rare case report. Cureus. 2022, 14, e23478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anehosur, V.; Mehra, A.; Kumar, N. Management of chronic long standing condyle dislocation. Int. Surg. J. 2023, 10, 114–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekram, S.; Tigga, C.; Prajapati, V.K.; Prakash, O. Elastic traction treatment for the management of chronic dislocation of bilateral condyle – A report of 2 case. Dent J Indira Gandhi Inst Med Sci. 2022, 1, 73–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navaneetham, R.; Navaneetham, A.; Pugazhendi, S.K.; Nara, G.; Umarani, P.J. Chronic protracted dislocation of temporomandibular joint in a trauma patient – a case report. Ann. Maxillofac. Surg. 2023, 13, 130–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, G.; Gupta, D.K.; Gupta, N.; Chandra, N.; Sankhla, D. Conservative management of a 3 months long standing bilateral temporomandibular joint dislocation: a case report. J. Oral Med. Oral Surg. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. 2023, 9, 222–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogundipe, O,K. ; Ugwu, E,I.; Ajayi, O,S.; Ojo, O,O. Reduction of manually irreducible TMJ dislocation with forceps traction: Case report in a 60-year-old woman. Nigerian Dent J. 2023, 31, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Zou, J, Wang, L. ; Acharya, K.; Hou, X.; Li, L.; Hu, X.; Xing, X. The experience of chronic protracted mandibular dislocation treatment: manual vs. surgical reduction. BMC Oral Health. 2024, 24, 1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, T.; Momozaki, N.; Honda, E.; Matsuno, A. Delayed diagnosis of temporomandibular joint dislocation in severe stroke patients. Cureus. 2024, 16, e68896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yanagisawa, Y.; Nogami, S.; Iwama, R.; Otake, Y.; Sato, S.; Yamauchi, K. A case of chronic bilateral temporomandibular joint dislocation treated via a bilateral intraoral vertical ramus osteotomy. Jpn. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2024, 70, 379–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, K. How doi inject botulinum toxin into the lateral and medial pterygoid muscles? Mov Disord Clin Pract 2017, 4, 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshida, K. Botulinum toxin therapy for oromandibular dystonia and other movement disorders in the stomatognathic system. Toxins. 2022, 14, 282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O'Connor, M. , Rooney, M.; Nienaber, C.P. Neuroleptic-induced dislocation of the jaw. Br. J. Psych 1992, 161:281–282. [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim., Z.Y.; Brooks, E.F. Ibrahim. Z.Y.; Brooks, E.F. Neuroleptic-induced bilateral temporomandibular joint dislocation. Am. J. Psychiatry. 1996, 153 (2), 2–3. [CrossRef]

- McGraw, T.A. A new method of reducing old dislocations of the lower jaw. Med. Record. 1899, 56, 511. [Google Scholar]

- Leclerc, G. ; Girard, G.Un nouveau procédé de butée dans le traitement chirurgical de la luxation récidivante de la mâchoire inférieure.Mém. Acad. Chir. 1943, 69, 457–459. [Google Scholar]

- Myrhaug, H. A new method of operation for habitual dislocation of the mandible. Review of former methods of treatment. Acta Odontol. Scand. 1951, 9, 247–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dautrey, J. Reflexions sur la chirurgie de l’articulation temporo-mandibulaire. Acta. Stomatol. Belg. 1975, 72, 577–581. [Google Scholar]

- Niezen, E.T.; B van Minnen, B.; Bos, R.R.M.; Dijkstra, P.U. Temporomandibular joint prosthesis as treatment option for mandibular condyle fractures: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2023, 52, 88–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laskin, D.M. Myotomy for the management of recurrent and protracted mandibular dislocations. 4th International Conference on Oral Surgery, Amsterdam, Copenhagen, 1973, Munskgaard 264, 1973.

- Miller, G.A.; Murphy. E.J. External pterygoid myotomy for recurrent mandibular dislocation. Oral Surg. 1976, 42, 705–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sindet-Petersen, S. Intraoral myotomy of the lateral pterygoid muscle for the treatment of recurrent dislocation of the mandibular condyle. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 1988, 46, 445–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sex, (n [%)] | Women, n = 139 (60.7%); men, n = 81 (35.4%); NR, n = 9 (3.9%) |

| Age (years), [mean ± SD, range] | 52.3 ± 19.5, 5–89 |

| Affected side, (n [%)] | Bilateral, n = 171 (72.5%); left, n = 11 (4.7%); right, n = 9 (3.8%); NR, n = 31 (13.2%) |

| Duration (months), (mean ± SD, n [%], range) |

11.9 ± 34.4, n = 174 (73.7%), range 1–300 |

| First clinical diagnosis, (n [%]) | TMJ dislocation, n = 100 (43.7%); undiagnosed, n = 39 (17%); palsy, n = 4 (1.7%); inflammation, n = 4 (1.7%); neurological diseases, n = 3 (1.3%); normal, n = 3 (1.3%); other, n = 5 (2.2%); NR, n = 71 (31%) |

| Previous dislocation, (n [%]) | Once, n = 14 (6.1%); frequently, n = 6 (2.6%); sometimes, n = 3 (1.3%); N, n = 37 (16.2%); NR, n = 169 (73.8%) |

| Anamnesis, (n [%]) | Psychiatric diseases, n = 19 (8.3%); dementia or menta retardation, n = 15 (6.6%); neurological diseases, n = 10 (4.4%); cerebral infarction, n = 10 (4.4%); cerebral hemorrhage, n = 9 (3.9%); brain injury, n = 4 (1.7%); NR, n = 121 (52.8%) |

| Diagnostic image, (n [%]) | Radiography; n = 165 (69.9%); CT, n = 57 (24.2%); MRI, n = 4 (1.7%); NR, n = 45 (19.1%) |

| Chief complaint, (n [%]) | Preauricular pain, n = 61 (25.8%); inability of mouth closing, n = 44 (18.6%); masticatory disturbance, n = 32 (13.6%); difficulty in speaking, n = 24 (10.2%); malocclusion, n = 15 (6.4%); facial deformity, n = 12 (5.1%); difficulty in swallowing, n = 12 (5.1%); other, n = 5 (2.1%); NR, n = 87 (36.9%) |

| Maximal mouth opening (mm), (mean ± SD, n [%]) |

24.6 ± 69.9, n = 62 (27.1%); NR, n = 167 (72.9%) |

| Open bite (mm), (mean ± SD, n [%]) | 14.4 ± 6.6, n = 26 (11.4%); NR, n = 203 (88.6%) |

| Edentulousness, (n [%]) | Total edentulous, n = 48 (20.3%); upper or lower, n = 8 (3.4%); N, n = 95 (40.3%); NR, n = 62 (26.3%) |

| Etiology, [n (%)] | Yawning, n = 33 (14.4%); unknown, n = 23 (10%); operation, n = 19 (8.3%); neurological diseases, n = 15 (6.6%); trauma, n = 14 (6.1%); fall, n = 13 (5.7%); tooth extraction, n = 13 (5.7%); motor vehicle accident, n = 12 (5.2%); sleep, n = 8 (3.5%); assault; n = 4 (1.8%); others, n = 4 (1.8%); NR, n = 69 (30.1%) |

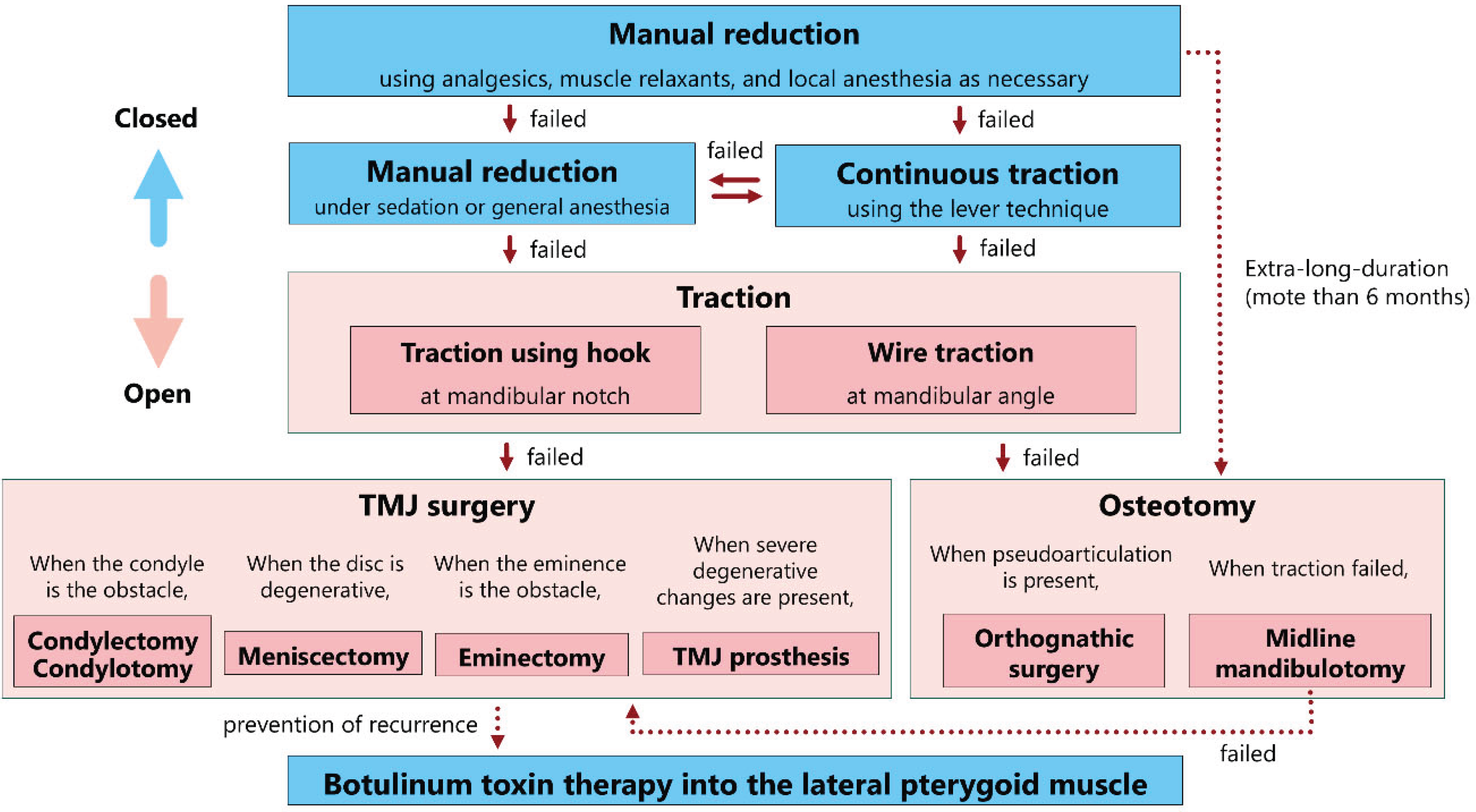

| Treatment, (n [%]) |

Closed reduction, n = 49 (21.4%) Manual reduction, n = 28 (12.2%); with instruments, n = 3 (1.3%), continuous traction, n = 17 (7.4%), 3–40 days |

|

Open reduction; n = 175 (76.4%) Hooking mandibular notch, n = 43 (18.8%), condylectomy, n = 25 (10.9%), eminoplasty, n = 20 (8.7%), eminectomy, n = 19 (8.3%), angular traction, n = 10 (4.4%), meniscectomy, n = 10 (4.4%), orthognathic surgery, n = 10 (4.4%), excision of fibrous tissue, n = 7 (3.1%), lateral pterygoid myotomy, n = 6 (2.6%), condylotomy, n = 5 (2.2%), total TMJ prosthesis, n = 3 (1.3%), coronoidectomy, n = 3 (1.3%), coronoidotomy, n = 3 (1.3%), levering condyle, n = 3 (1.3%), other, n = 10 (4.4%), NR, n = 19 (8.3%) | |

|

Incision Preauricular, n = 107 (46.7%), submandibular, n = 24 (10.5%), zygomatic arch , n = 15 (6.6%), intraoral, n = 13 (5.7%), Al-Kayat Bramery, n = 4 (%), Bockenheimer-Axhausen, n = 3 (1.3%), other, n = 5 (2.2%) |

| Treatment complication, (n [%]) |

Facial nerve paralysis, n = 8 (6.9%); redislocation, n = 3 (2.6%); others, n = 3 (2.6%); N, n = 77 (66.4%); NR, n = 17 (7.4%) |

| Fixation (days), (n [%], mean ± SD) |

Y, n = 122 (53.3%), 17.5 ± 15; N, n = 20 (8.7%); NR, n = 76 (33.2%) |

| Follow-up (months), (mean ± SD, n [%], range) |

11.8 ± 13, n = 147 (64.2%), 0.25–96; NR, n = 82 (35.8 |

| Maximal mouth opening at follow-up (mm), (mean ± SD, n [%], range) |

36.2 ± 6.8, n = 90 (77.6%), 22–51, 35; NR, n = 23 (19.8%) |

| Sequelae, (n [%]) | Redislocation; n = 4 (%), deviation; n = 3 (%), condylar absorption; n = 2 (%), other; n = 9 (%); N, n = 128 (55.9%); NR, n = 69 (30.1%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).