1. Introduction

Today, thousands of scientific papers are freely accessible online, yet identifying those truly relevant to a specific research question remains a persistent challenge. Keyword-based search engines often retrieve documents that contain the correct terms but fail to align with the user’s actual intent. This limitation is especially burdensome when writing “Related Work” sections, which require filtering through large volumes of text to find and summarize the most pertinent studies. The problem is amplified for students or early-career researchers entering new fields. To address this gap, we present a prototype web application that integrates semantic search, citation generation, document summarization, and similarity visualization into a unified platform. The system leverages the paradigm of retrieval-augmented generation (RAG) [

1] to improve search relevance by combining dense vector retrieval with large language model (LLM) generation. This enables natural language queries to return meaning-based results rather than just lexical matches, significantly streamlining the academic workflow. One of the primary motivations for this system was to assist users in generating structured and coherent “Related Work” sections by automatically synthesizing content from selected papers.

The RAG framework was first introduced by Lewis et al. [

1] and has since become a widely adopted method for grounding LLM outputs in external, updatable knowledge sources. It outperforms purely parametric models in factual accuracy and significantly reduces hallucinations, especially in dialogue systems [

2]. Surveys further confirm that hallucination remains a major challenge for LLMs and that retrieval-augmented methods represent a promising mitigation strategy [

3]. They are particularly effective in knowledge-intensive tasks with limited labeled data, as demonstrated by Izacard et al. [

4], who showed that such models can perform well even in few-shot scenarios with fewer parameters. Recent literature supports the increasing importance of RAG across diverse NLP tasks. Gao et al. [

5] emphasizes how RAG contributes to factual consistency and overall system robustness, while Muhammad Arslan et al. [

6] outlines its adoption across fields such as healthcare, education, and enterprise systems. However, practical challenges remain, including the lack of standard architecture, dataset diversity, and API (Application Programming Interface) related costs. Khan et al. [

7] and Wang et al. [

8] explore engineering-level implementation strategies and optimization best practices. Chen et al. [

9] further contributes by introducing the RGB (Retrieval-Augmented Generation Benchmark) benchmark, designed to evaluate retrieval-augmented models for robustness, reasoning, and integration, all of which are relevant to the system described in this work. Looking forward, Jiang et al. [

10] propose adaptive RAG frameworks that retrieve information based on output uncertainty, offering a path toward more responsive LLM behavior. Radeva et al. [

11] implemented a similar multi-LLM retrieval system (PaSSER) for smart agriculture and demonstrated the effectiveness of Mistral 7B, the model used in our system, in balancing latency and accuracy. From a system architecture perspective, Humza Naveed et al. [

12] offer a comprehensive review of LLM designs, confirming our modular design approach that separates retrieval from generation. The need for reliable evaluation is further reinforced by Chang et al. [

13], who highlight persistent weaknesses in LLMs regarding reasoning and robustness, areas we directly test via empirical retrieval metrics. Security considerations also play a role in LLM-integrated systems. Rodrigo Pedro et al. [

14] investigated prompt-to-SQL (P2SQL) injection attacks and highlighted the importance of defensive design in applications where LLMs interact with backend services. Finally, beyond technical capabilities, the integration of LLMs in education and research must be approached with care. Kasneci et al. [

15] emphasizes the importance of transparency, human oversight, and ethical safeguards, principles reflected in this prototype’s controlled, verifiable design.

The application focuses on selected scientific domains such as soil mapping, land cover classification, remote sensing, and environmental monitoring. Around 1,000 papers from the arXiv repository, all published in the last year, were segmented and embedded using the all-mpnet-base-v2 model for semantic comparison. Although the system is not yet intended for public release, it serves as proof of concept for how retrieval-augmented systems can assist in academic search, citation, and content synthesis.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Similarity Search

Semantic similarity refers to the ability to compare texts based on meaning rather than just exact word overlap. This capability is essential in modern search systems, especially in academic domains where the same concept may be expressed in many ways. Traditional keyword search is limited to lexical matches and often fails to retrieve semantically relevant documents if different vocabulary is used. To overcome this, modern systems convert text into embeddings, dense numerical vectors that capture semantic content, and compare them using cosine similarity, where higher scores indicate stronger alignment in meaning. As outlined in a recent survey of semantic similarity techniques [

14], methods in this space have evolved considerably. Knowledge-based approaches rely on external resources like ontologies (e.g., WordNet) to infer meaning from structured relationships but tend to lack domain flexibility. Corpus-based methods, such as TF-IDF (Term Frequency-Inverse Document Frequency) or LSA (Latent Semantic Analysis), derive similarity from statistical co-occurrence patterns but do not fully capture semantics. Deep neural network-based models, particularly transformer-based architectures, learn contextual representations directly from large text corpora and achieve superior performance, although at higher computational cost. Hybrid methods combine the strengths of multiple approaches to improve robustness and adaptability. The embedding model used in this work, all-mpnet-base-v2 model, is a transformer-based sentence encoder that falls into the neural network-based category. It is part of the Sentence Transformers library and is specifically fine-tuned for semantic similarity tasks like search and clustering. This model is among the top performers on standard semantic textual similarity benchmarks and offers an effective balance between accuracy and efficiency for academic retrieval. To further support semantic exploration beyond ranked lists, this system also incorporates semantic similarity graphs. In these graphs, papers are represented as nodes, and edges are formed between papers that represent high similarity in their vector representations. While not a replacement for traditional ranking, this visual approach enhances users' ability to interpret relationships between papers and discover related work in a more intuitive way.

Table 1 outlines the key differences between these retrieval and exploration strategies.

2.2. Large Language Models

Large language models (LLMs) are advanced neural networks trained to understand and generate natural language. They work by predicting the next word in a sentence, using patterns they learned from large text datasets. LLMs are used for many tasks such as writing, summarizing, translating or answering questions. Most LLMs today are built using the Transformer architecture [

15], which is the foundation of their performance. A key part of the Transformer architecture is a mechanism called self-attention. This mechanism allows the model to examine all the words in a sentence at once and assign importance to each word depending on the task, for example, when predicting the next word or understanding a word’s meaning in context. In contrast, older models like Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) or Long Short-Term Memory networks (LSTMs) processed text sequentially, one word at a time, which made it difficult to capture long-range dependencies and contextual relationships effectively. Self-attention addresses this limitation by giving the model access to the entire input sequence at every step, allowing it to model relationships between distant words more effectively. There are several types of LLMs:

Decoder-only models (such as Generative Pre-trained Transformer (GPT)) and they are optimized for generating text from a prompt;

Encoder-decoder models (like the Text-to-Text Transfer Transformer (T5) or the Bidirectional and Auto-Regressive Transformer (BART)) and they are good for tasks that involve transforming one type of text into another, such as translation or summarization;

Retrieval-augmented models combine a language model with a retrieval system to look up relevant external information during generation. This helps improve factual accuracy and reduces the likelihood of generating incorrect or made-up content.

LLMs are powerful because they can perform a wide range of tasks with little or no fine-tuning, and they produce fluent, natural text. However, some models, especially those without retrieval, may still generate inaccurate or unsupported answers (a problem known as hallucination), struggle to update their knowledge after training, and often do not cite the source of the information they provide. Retrieval-augmented models address many of these issues by grounding responses in real, up-to-date documents.

2.3. Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) Pipeline

Retrieval-augmented generation (RAG) is a technique that helps LLMs give better and more reliable answers by letting them search for information instead of relying only on what they learned during training. RAG systems combine two types of models: a retriever and a generator.

The retriever is responsible for finding the most relevant documents from an external source of information, such as a document collection or a vector database. It is called non-parametric because it doesn't store knowledge in the form of model parameters. Instead, it performs a live search each time a question is asked. This means the knowledge can be easily updated without retraining the model;

The generator is LLM itself. It is a parametric model, which means it contains knowledge within its internal parameters, based on what it learned during training. The generator takes both the user's question and the retrieved documents as input and produces a written response.

To make the retrieved information usable by the generator, the system applies augmentation methods. These include splitting long documents into smaller parts (so they fit within input limits), reformatting the input into a structured prompt or summarizing content to include more information in a compact form. RAG improves LLM performance by grounding answers on real, external information. This helps reduce hallucinations, makes the model more up-to-date and allows users to see where the information came from. These features are especially useful in applications that need reliable facts and traceable sources, such as research, legal analysis or enterprise decision-making. Still, RAG systems bring their own challenges, for example, the quality of retrieved content strongly affects the final answer, and managing long inputs remains a technical limitation.

2.4. System functionality

This research presents a web application developed to assist users in searching, organizing, and understanding scientific literature more effectively. The main feature of the system is its meaning-based search functionality, which is powered by text embeddings. Instead of using simple keyword matching, the application converts both user queries and paper content into high-dimensional vectors and compares them using semantic similarity. This allows the system to understand the actual meaning behind a user’s query and return papers that are most relevant, even if they use different wording. Users can adjust the number of retrieved text segments (chunks) based on semantic similarity, which helps improve the relevance and usefulness of the search results. In addition to searching, users can interact with the system by asking direct questions. When a specific paper is selected, the application retrieves the most relevant sections of that paper and uses them to generate a focused answer. If no paper is selected, the system compares the question to both paper summaries and document sections across the entire database and selects the most relevant ones to build the response. In both cases, the answer is generated using a language model and is based only on real content from the papers, which reduces the chances of incorrect or made-up information. The app also supports citation generation. Users can select one or more papers and automatically receive references in one of several common styles: APA, MLA, ISO 690, Chicago, IEEE, AMA, or ACS. This makes it easy to create properly formatted citations while writing academic texts or reports. Another key feature is the ability to summarize user-uploaded PDF (Portable Document Format) documents. Uploaded files are stored in a private part of the database, used only by the users. These personal papers are not included in global search or similarity comparisons, which keeps shared results unbiased and ensures privacy. Summaries for uploaded papers can be generated on demand, so users can choose whether to create them immediately or later, depending on their needs. To support further analysis, the system includes tools for finding similar papers based on a selected document, comparing two papers side-by-side using their summaries, and generating a structured “Related Work” section using multiple selected papers. The related work section is written by the language model and includes inline references, helping users prepare well-organized overviews of relevant research. The similarity graph feature allows users to visually explore how selected papers are connected. Each paper is represented as a node, and links between them reflect their degree of semantic similarity. This graph view helps users easily identify groups of related papers and discover clusters of research that are closely linked by topic. Lastly, the application provides a “Papers” page, where users can browse all available papers in the database. This page shows important metadata for each paper, including the title, authors, summary, publication date, DOI (Digital Object Identifier), journal reference, and PDF link. Users can also search by title to quickly locate specific papers. Together, these features make the application a complete platform for semantic search, research discovery, document comparison, citation management, and academic writing assistance.

2.5. Technologies Used

The backend is implemented using Python and the FastAPI framework, which is well suited for building web APIs (Application Programming Interfaces) that manage language model interactions and database queries. On the frontend, the user interface is built with React and TypeScript, while styling is handled using Tailwind CSS. This setup enables structured component development and a consistent visual layout across the interface. Text embeddings are created using the sentence-transformers/all-mpnet-base-v2 model from the sentence-transformers library. This model encodes text into 768-dimensional vectors, which are used for comparing the meaning of queries and documents. These vectors are stored in a PostgreSQL database hosted on Supabase, which provides managed storage and vector search capabilities. To enable similarity search on the stored embeddings, the pgvector [

16] extension is used, which supports vector operations such as cosine similarity directly in the database. Language generation features, such as summarizing papers, answering questions, and writing related work sections, are implemented using the Mistral 7B model [

17], accessed via the mistralai Python library. This model receives context in the form of retrieved document segments and returns generated responses tailored to the user’s input. To build the paper similarity graph, the application uses NetworkX to construct the graph data and Pyvis to render the graph as an interactive visualization in the browser. This visualization allows users to explore connections between selected papers based on content similarity. Additional tools include the arxiv Python library, which was used to download metadata from the arXiv repository, and PyMuPDF for retrieving PDF files. Citation generation is handled using regular expressions that create references in multiple academic styles. Together, these components support document management, semantic search, academic writing, and information exploration within the system.

2.6. Data Storage and Indexing Infrastructure

To support efficient semantic retrieval, the application stores precomputed text embeddings in a PostgreSQL database using the pgvector extension. Each paper is represented at two levels: full-document summaries and smaller text segments (chunks). These are stored in separate tables (papers and paper_chunks) for structured access. Each embedding is stored as a VECTOR(768) column, enabling fast similarity queries. This setup allows precise retrieval of relevant content using vector distance measures and supports scalable operations for thousands of papers and segments. The system supports both IVFFlat (Inverted File Flat) and HNSW (Hierarchical Navigable Small World) indexing, as provided by the pgvector extension. Indexing is a technique used to accelerate data retrieval by structuring data for faster access. In semantic search systems, vector indexes help locate the most relevant high-dimensional embeddings without comparing every entry exhaustively. This system supports two indexing methods via the pgvector extension: IVFFlat and HNSW:

IVFFlat partitions the vector space into clusters and performs search within the most relevant clusters. It requires pre-training and can be fast but may sacrifice some recall;

HNSW, in contrast, builds a navigable multi-layer graph over the embeddings. It does not require prior training and offers higher recall and faster average query times, making it preferable in this implementation.

HNSW indexing method enhances the responsiveness of the semantic search engine, especially when dealing with large embedding datasets. This index was created on the embedding column of the paper_chunks table with the following code:

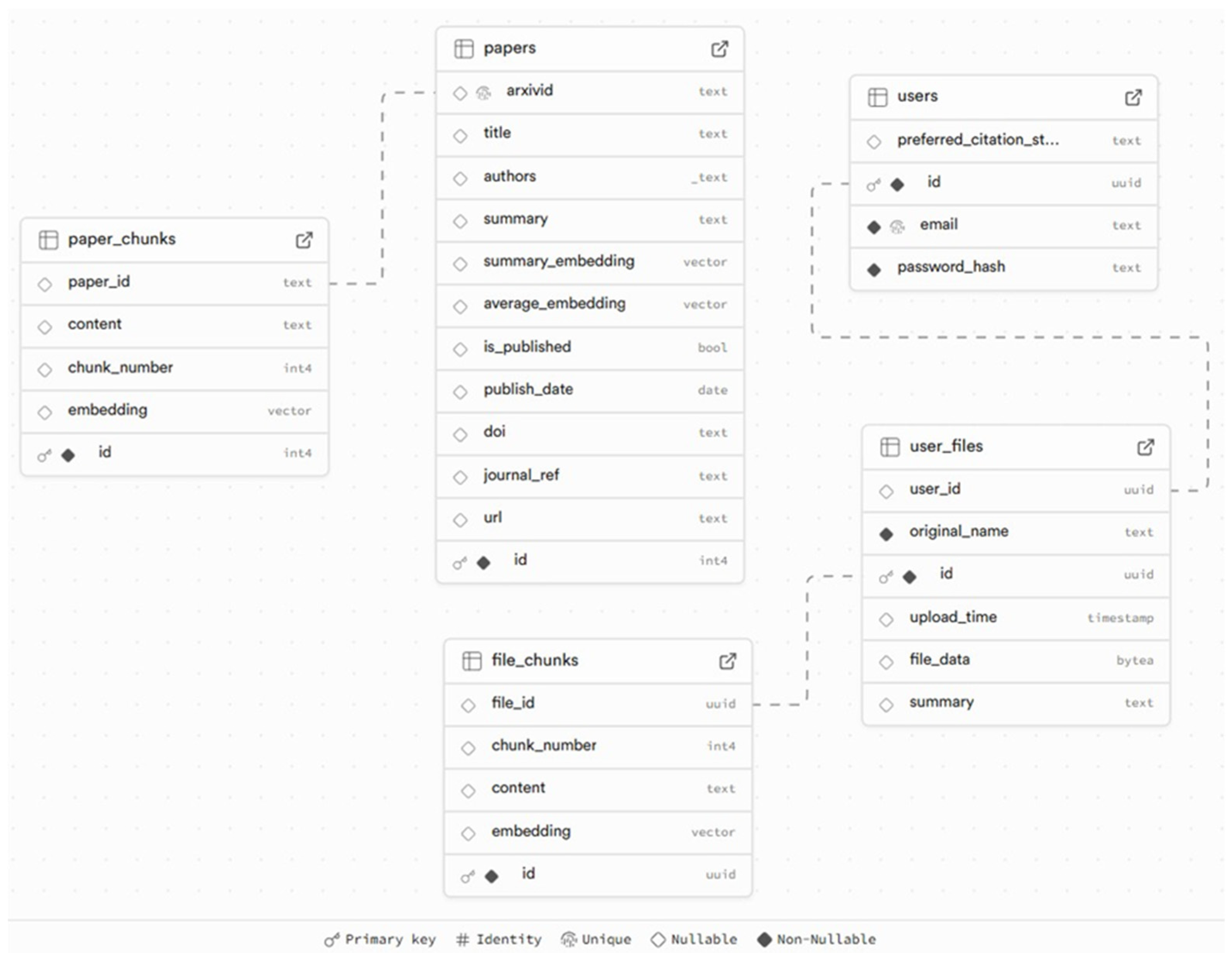

Due to input length limitations of the all-mpnet-base-v2 model (maximum 384 tokens), each document was divided into segments of fewer than 300 tokens. The chunking strategy used context-aware sentence segmentation, which attempts to split text at sentence boundaries by identifying punctuation such as periods. This method preserves the logical structure of the content but is not perfect, for example, it may split incorrectly at numerical lists (e.g., “2.”, “3.”) or abbreviations. Chunking was implemented using the NLTK (Natural Language Toolkit) library and a BERT-compatible tokenizer, with an overlap of 50 tokens to preserve context across adjacent segments. Alternative strategies like fixed-length or paragraph-based chunking exist, but sentence-based segmentation was chosen to retain semantic coherence. The papers were sourced from the arXiv repository and selected from domains like soil science, remote sensing, land cover, environmental monitoring, and geospatial machine learning. In total, 998 papers were collected, forming the dataset used throughout the application. The database design supports efficient semantic search and paper management through a structured relational schema, shown in

Figure 1. Publicly available papers and their semantic chunks are stored separately from user-uploaded files, which follow a similar structure. The papers table holds metadata and summary embeddings for arXiv papers, while paper_chunks stores their segmented content with vector representations. User uploads are stored in user_files and chunked into file_chunks, enabling private semantic search for individuals. The users table manages account credentials and citation preferences. This scheme allows for fast retrieval, personalized interactions, and scalable storage of semantic data. The paper_chunks table, which stores text segments and their corresponding 768-dimensional embeddings, occupies approximately 221 MB (Megabytes) for just 41277 entries. Once an HNSW index is built on the embedding column, the total storage increases to around 383 MB. This additional space reflects the memory required to maintain the multi-layer HNSW graph structure for fast similarity search.

2.7. RAG Workflow Implementation

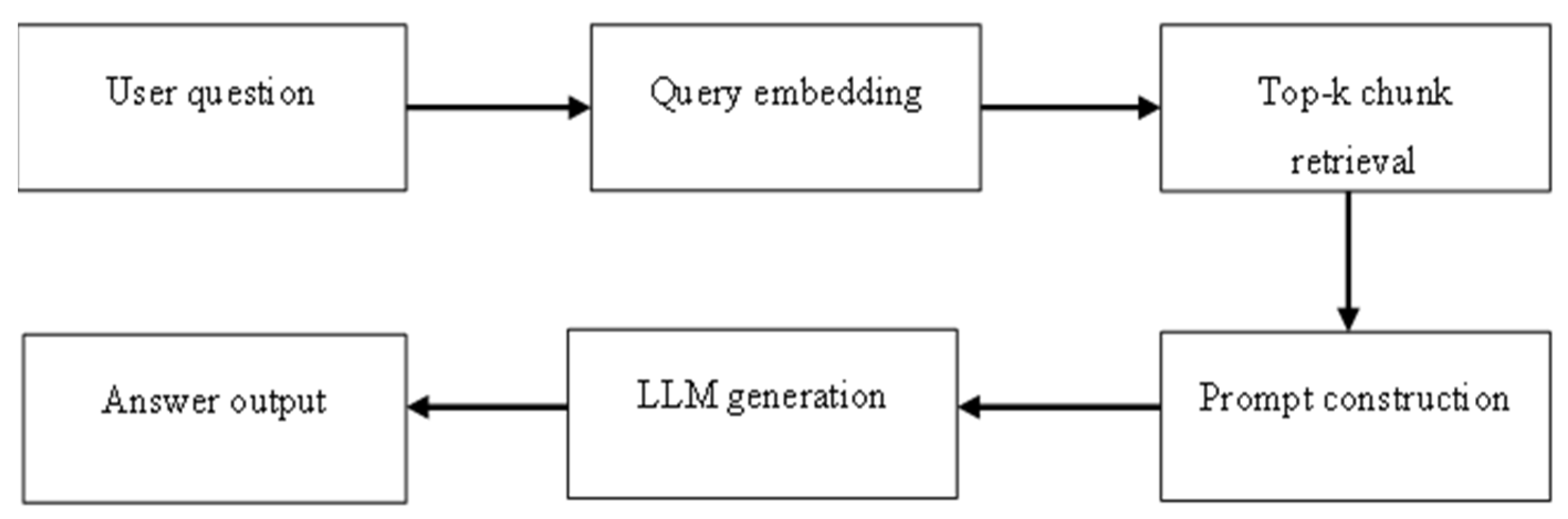

The application uses an RAG pipeline to answer user questions with accurate and grounded responses. This method combines semantic retrieval from a document collection with generative response capabilities of a large language model. The full process is illustrated in

Figure 2.

In the first step, user submits a natural language question, either about a specific paper or the entire document collection. The interface allows selection of the paper to ask about, if desired. Then the question is converted into a 768-dimensional embedding using the all-mpnet-base-v2 model that was also used to embed the document chunks. This ensures compatibility between the question and the stored document vectors. Then for the top-k chunk retrieval step, the embedded question is compared to the embeddings of text chunks stored in the database, using cosine similarity. By default, the system retrieves the top 3 most semantically similar chunks. If a user selects a specific paper before submitting a query, the search is restricted to that paper’s content and the query includes a WHERE clause to restrict retrieval to that paper. If no paper is selected, the condition is omitted, and the system retrieves from the full dataset. This scoping ensures that retrieval is contextually appropriate, narrow when focused and broad when exploring. The SQL command used for this retrieval is:

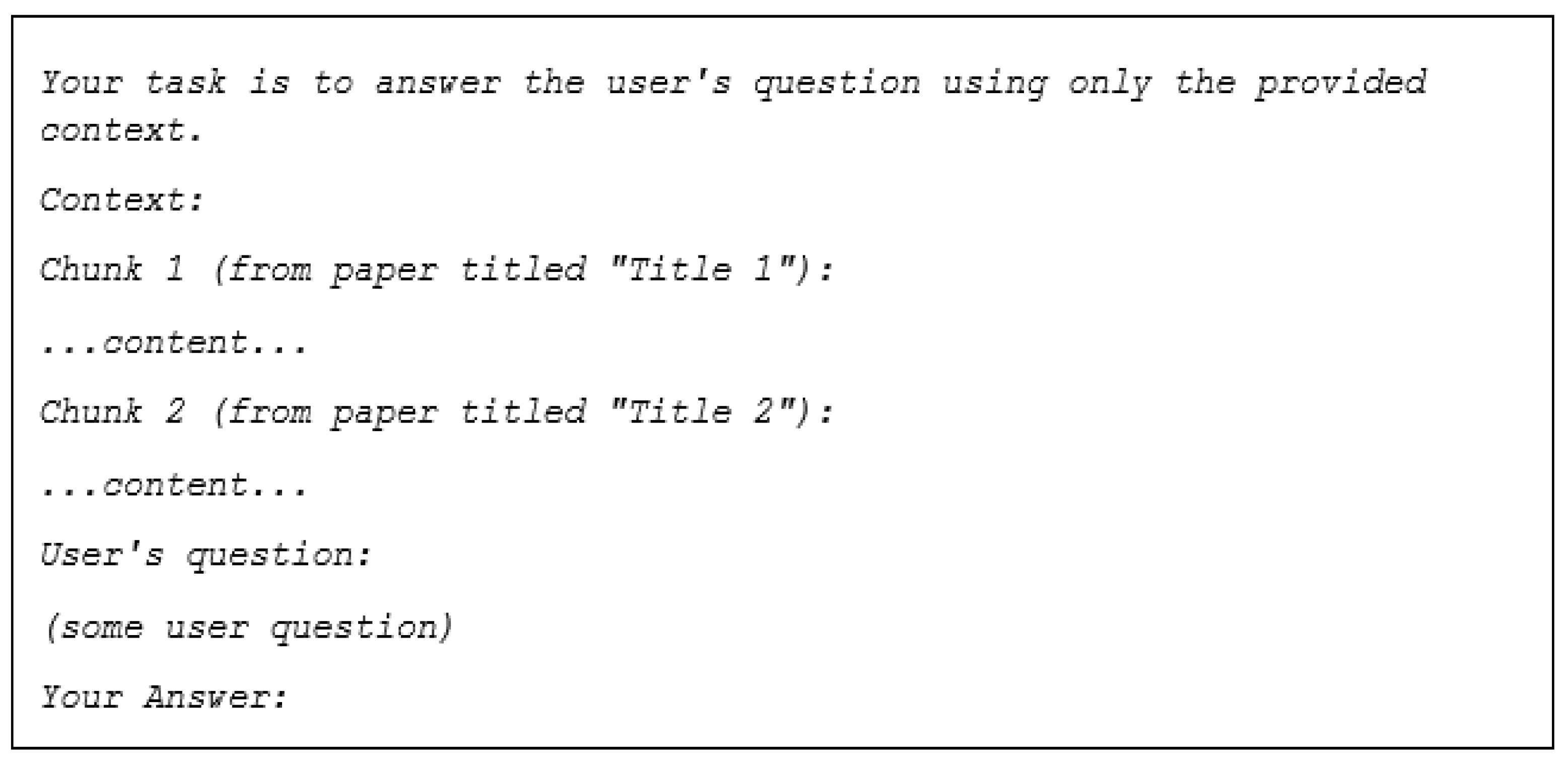

Once the top-k most relevant text chunks are retrieved, the system constructs a prompt designed to guide the language model Mistral 7B toward accurate and grounded answers. This prompt includes:

A system instruction that sets the model’s role (e.g., “You are a helpful and accurate scientific paper expert. Your task is to concisely answer the user's question using only the provided information.”) and defines its limitations (e.g., “If the information is insufficient to answer the question, simply say: ‘I do not have enough information to answer this question accurately.’”);

A formatted list of retrieved chunks, each labeled with the original paper title;

The user’s original question, clearly separated at the end of the prompt.

This design ensures that the model has structured context and is explicitly discouraged from using external or hallucinated knowledge. The prompt is dynamically generated on the backend and the retrieval step always includes the top 3 most semantically similar chunks. This number balances response quality and prompt size for the language model. Although this value can be fine-tuned for more exhaustive results or shorter completions, 3 chunks have shown to be a reasonable default across most use cases. An example of the prompt structure is shown in

Figure 3.

Final prompt is then sent to the Mistral 7B language model, which generates a response based solely on the context provided. To improve reliability, the generation process uses two key parameters:

Temperature = 0.3, which controls the randomness of the output. A lower value like 0.3 makes the model more focused and deterministic, helping reduce speculative or made-up answers (hallucinations);

Max_tokens = 500, is set not to limit display capacity, but to constrain overly verbose outputs. This prevents the model from generating unnecessarily long or speculative answers to simple questions, maintaining focus and relevance.

The combination of a well-structured prompt and these parameters helps ensure that the answers are more factually accurate and grounded in the retrieved content. When the answer is made, it is returned to the user through the interface. If the system determines that the context does not contain an answer, the LLM is expected to respond accordingly (“I do not have enough information to answer this question accurately”).

2.8. Evaluation Methodology

To comprehensively evaluate the system’s performance, several standard information retrieval and generation metrics were used to assess retrieval accuracy and system responsiveness. In the context of document retrieval, Recall measures the system’s ability to find all relevant results. Specifically, Recall@k indicates the proportion of relevant documents that appear within the top k retrieved results. A high Recall value implies that the system is effective at capturing relevant content, which is especially important when users need comprehensive coverage of a topic. Mean Reciprocal Rank (MRR) complements Recall by focusing on the rank position of the first relevant result. It is calculated as the average of the reciprocal ranks (1/rank) of the first correct item across all queries. MRR gives insight into how early relevant information appears in the results list. A higher MRR indicates that the system is not only retrieving relevant results but also ranking them well. Precision, on the other hand, reflects how many of the retrieved documents are relevant. Precision@k is the fraction of the top k retrieved documents that are correct. While Recall assesses coverage, precision measures specificity, how accurate the system is in avoiding irrelevant content. To further evaluate ranking quality, Mean Average Precision (MAP) was used. MAP averages the precision at each point where a relevant document is retrieved, across all queries. It reflects both the quantity and ranking order of relevant results. A high MAP value indicates that relevant documents are consistently ranked near the top of the list, which improves user experience by reducing the need to scroll through irrelevant content. To establish a meaningful baseline for comparison, the same evaluation was also performed using a TF-IDF (Term Frequency–Inverse Document Frequency) retrieval approach. TF-IDF is a classical statistical method that scores documents based on the frequency of query terms, adjusted for how common those terms are across the entire corpus. Unlike vector embeddings, TF-IDF does not capture semantic similarity beyond exact or near-exact word matches. Comparing the performance of TF-IDF with semantic search models (e.g., those using sentence embeddings and vector indexes) helps demonstrate the improvements gained from using modern language representations. In addition to retrieval accuracy, system latency was measured across various components to evaluate responsiveness. Basic timing observations were recorded for document retrieval, similarity graph construction, and answer generation using a language model. While only document retrieval was systematically measured across multiple runs, example times were noted for the other two features to offer a general sense of performance.

3. Results

3.1. Final User Interface

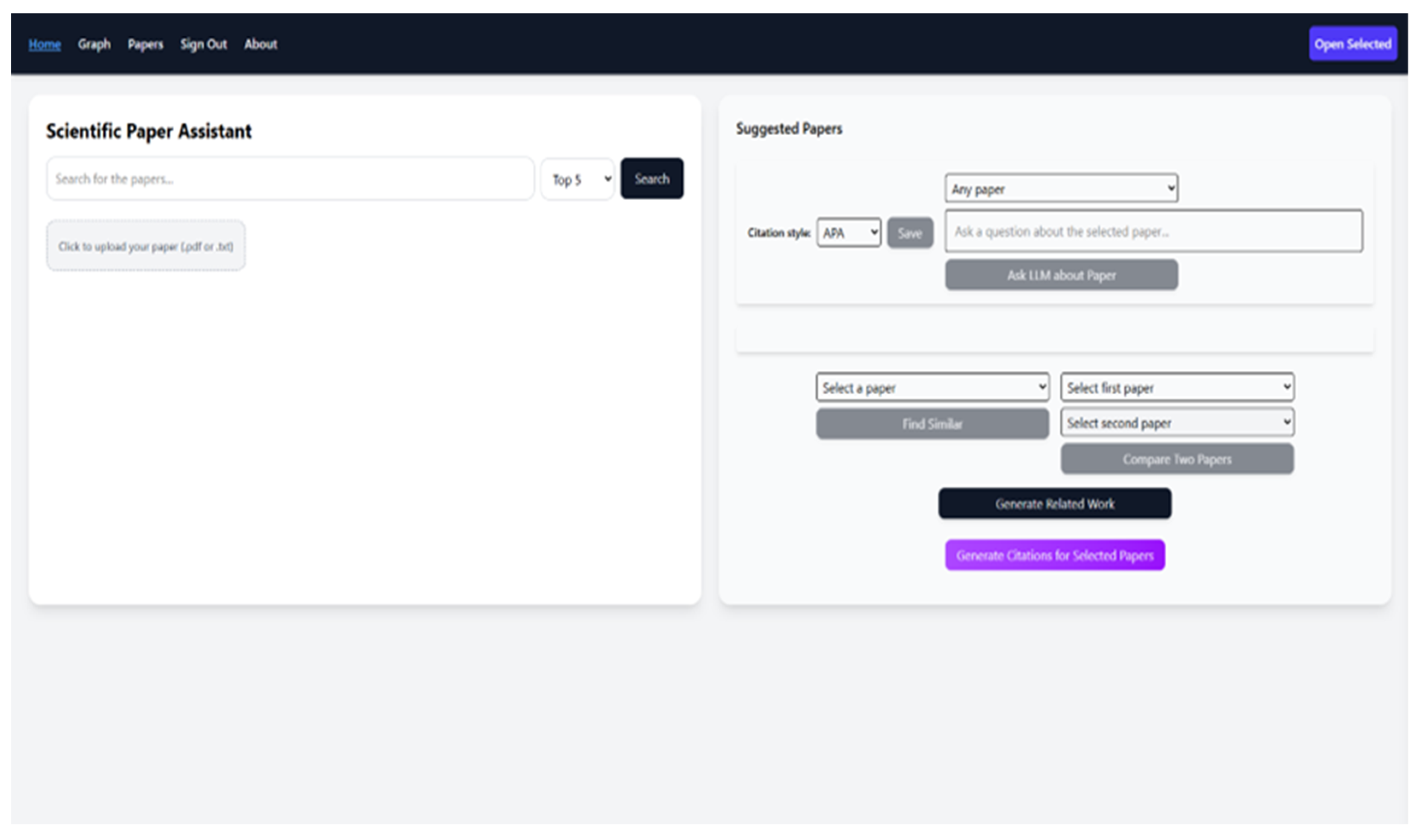

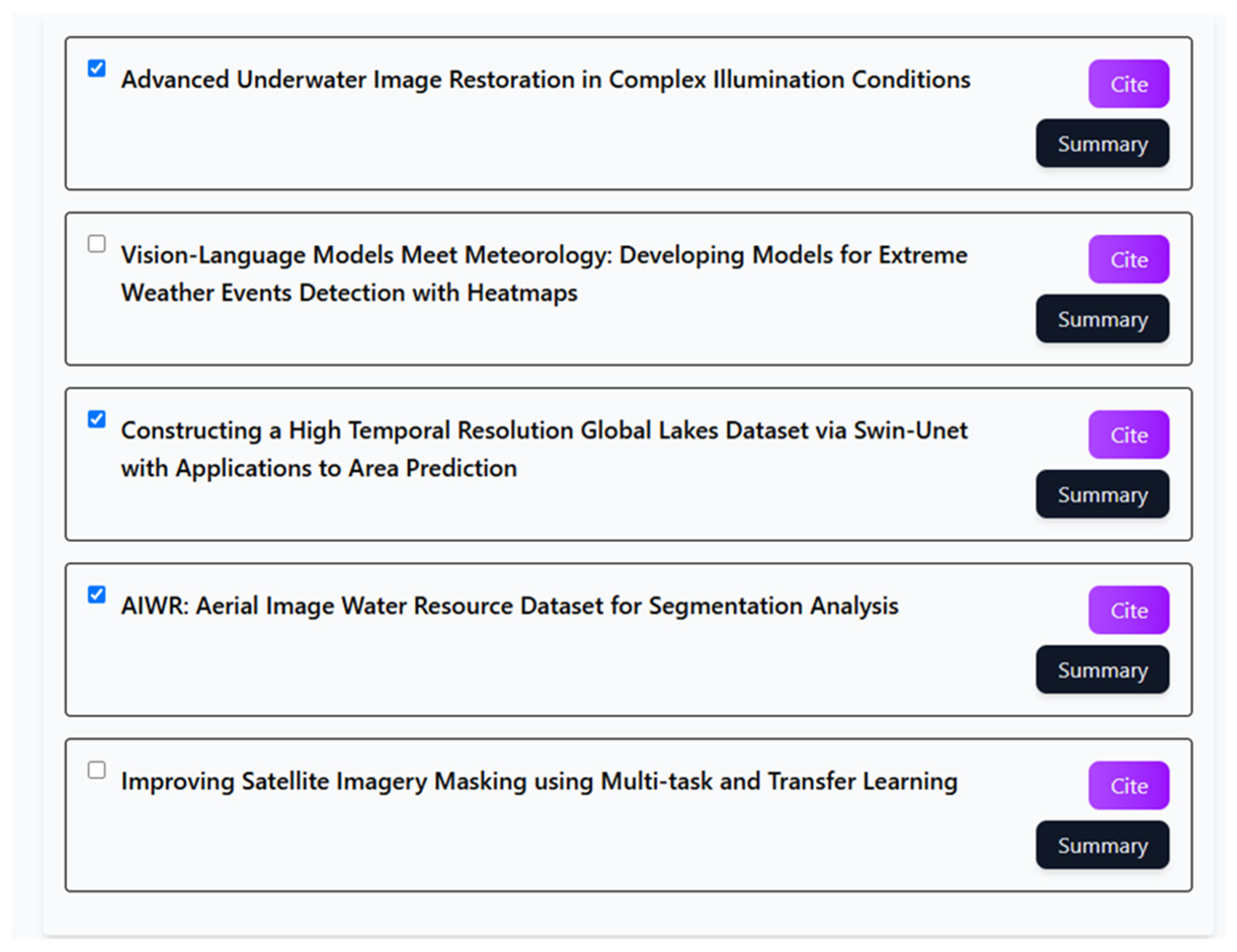

The Home page of the application is divided into two panels, as shown in

Figure 4. On the left side, users can enter a search query and select the number of content chunks they want to retrieve. The system uses semantic similarity via vector embeddings to return relevant results. These results are displayed on the right side as a list of retrieved papers, each showing its title and including buttons to display its summary or generate a citation (see

Figure 5).

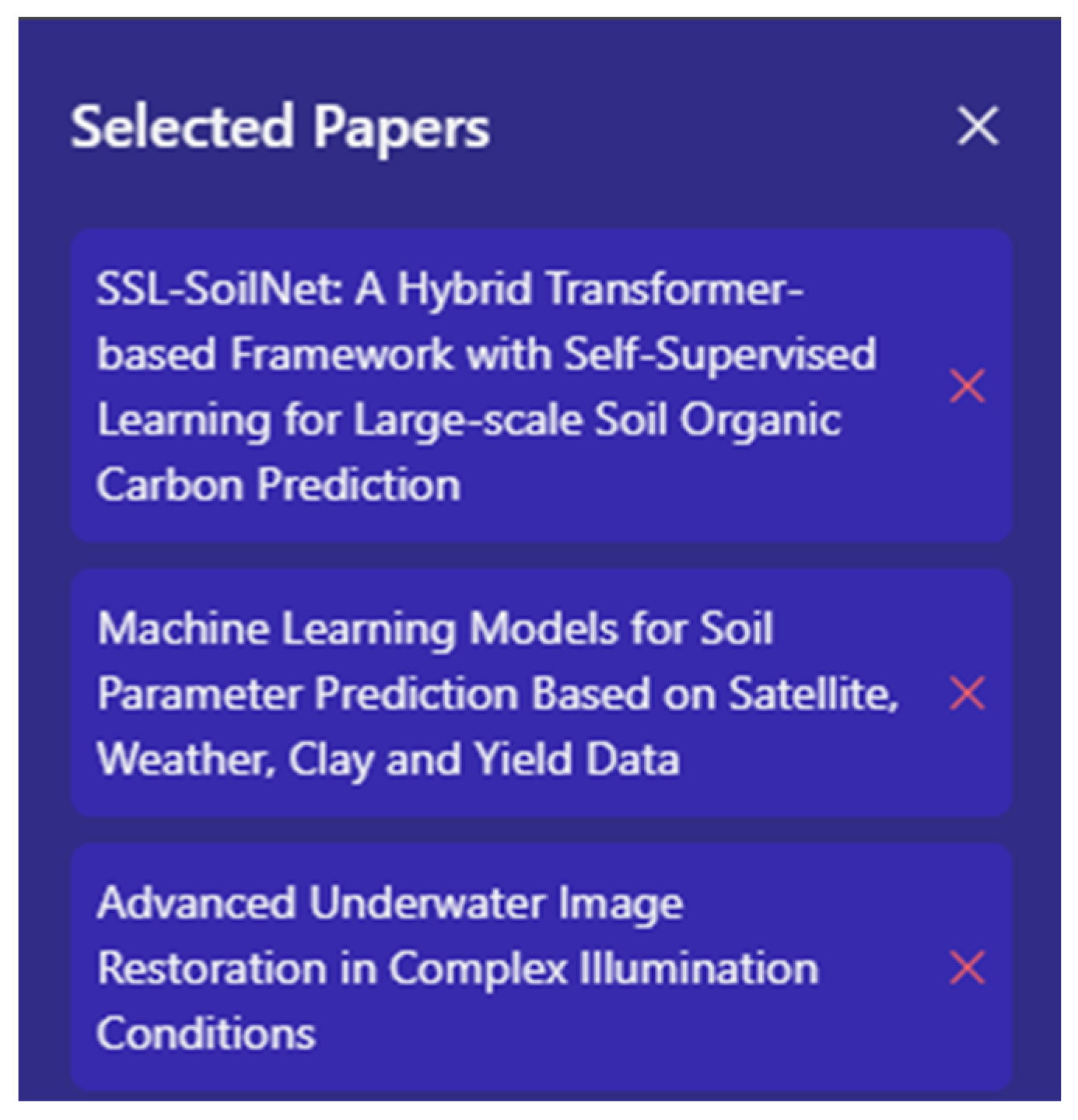

Summaries for these papers are already scraped from arXiv, while summaries for user-uploaded papers can be generated manually if needed. Each retrieved paper includes a checkbox that users can mark to select it. Selected papers are shown in a sidebar, which is opened using the “Open Selected” button in the top-right corner of the interface. This button is always visible. If no papers are selected, the sidebar opens but remains empty. As illustrated in

Figure 6, the sidebar displays the titles of all selected papers and allows users to remove them by clicking the red “X” next to each one.

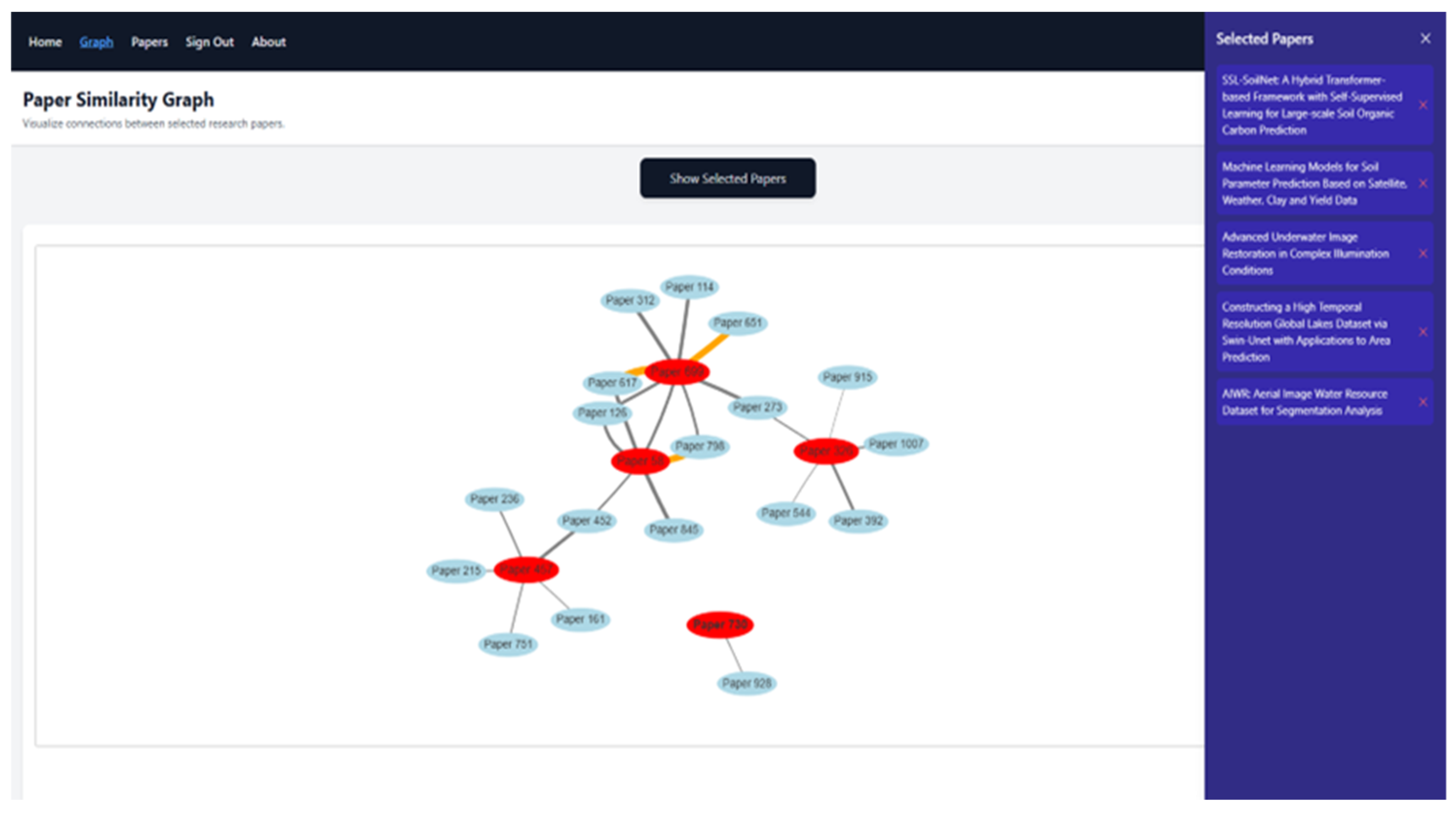

Several advanced functions can be accessed using buttons tied with selected papers. The "Generate Related Work" button produces a structured academic paragraph with inline citations by using a language model to process the summaries of the selected papers. The "Compare Two Papers" button enables users to select two papers from dropdown menus and view their summaries side by side for quick comparison. The "Find Similar" button allows users to select one paper and retrieve the three most semantically similar papers based on summary similarity with other papers in database. All outputs generated by the language model, whether for comparison, related work, question answering, or similar paper suggestions, are displayed in a shared response area located just below the related work section. If multiple functions are used, the responses update dynamically within the same frame, and only the relevant output is changed while others remain visible. This helps users keep track of various outputs in one place. The system also supports citation generation in various academic styles: APA, MLA, ISO 690, Chicago, IEEE, AMA, and ACS. Users can choose to generate citations either for a single paper or for all selected papers at once. These features are especially useful for simplifying the writing process in academic environments. Two additional pages are available in the application: Graph and Papers. The Graph page displays a visual representation of content similarity between selected papers (see

Figure 7).

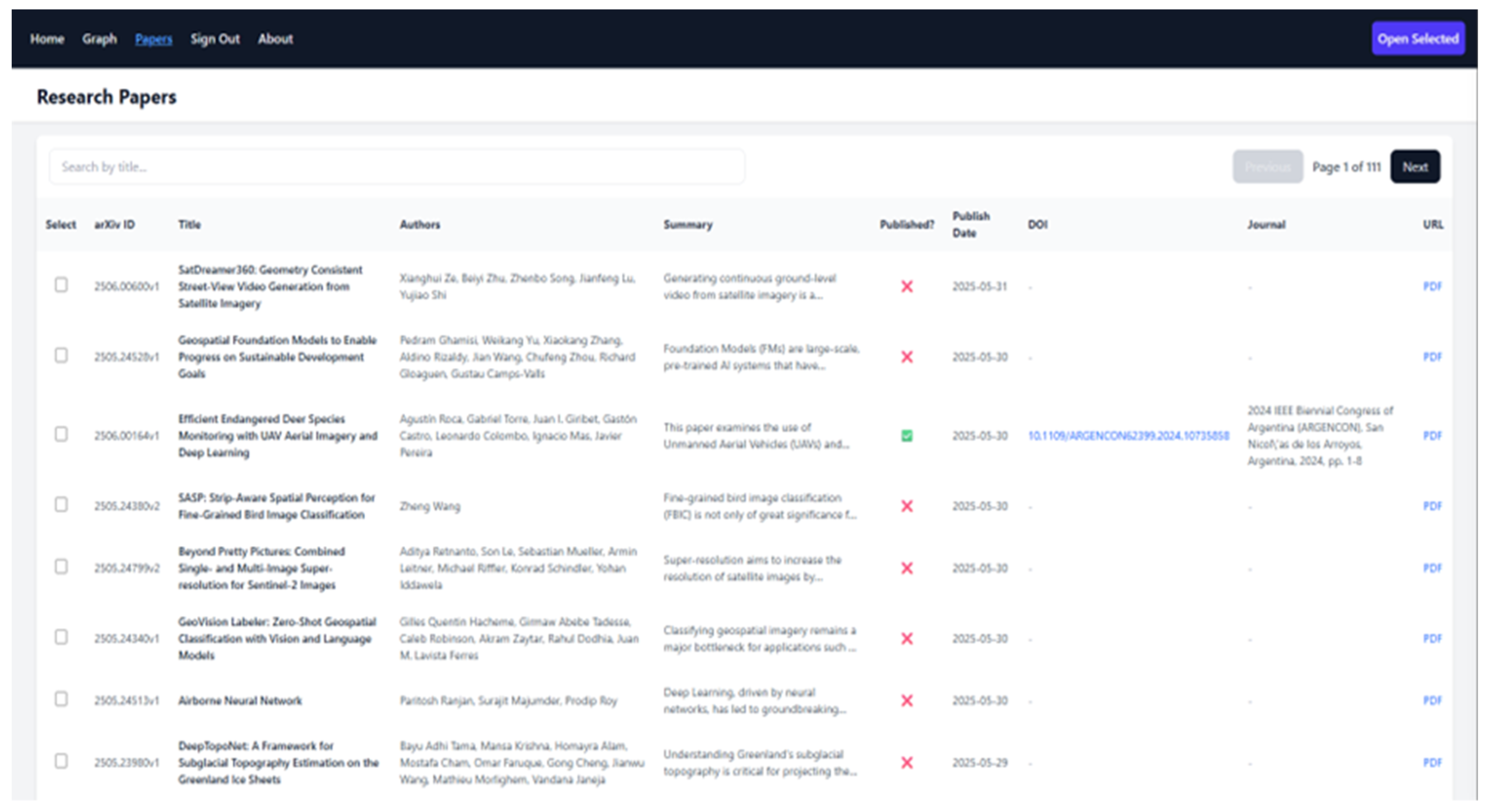

Users must first mark the papers they are interested in (on the Home or Papers page) and then click the "Show selected papers" button. The graph is rendered in a dedicated interactive section of the interface and only appears if at least one paper is selected. Paper titles and relationships are shown as an interactive network graph inside that section. The Papers page provides a searchable and paginated table of all stored research papers, as illustrated in

Figure 8.

Each row contains metadata such as the arXiv ID, title, authors, summary, publication status, publication date, DOI, and journal reference. A direct link to the paper’s PDF file is also provided, allowing users to access the full text immediately without navigating through the arXiv abstract page. A search input allows filtering by title, and each entry includes a checkbox for paper selection. Together, these components provide a complete interface for semantic retrieval, document exploration, citation management, and academic text generation.

3.2. Qualitative System Output

This section presents qualitative results from the developed system. Several key features are demonstrated using sample queries and outputs, including document retrieval, similarity graphs, generated answers, and related work sections. These examples help illustrate how the system performs in real-world usage and what kind of results users can expect.

3.2.1. Semantic Search

To test the system’s ability to retrieve relevant scientific papers based on a user’s query, semantic search was performed using two different inputs: one short and one more complex. The goal was to examine how well the system can understand query meaning and return papers that are topically relevant.

Example 1 - "Soil erosion detection using satellite images"

Top results:

In this example, the system returned only one paper among the top 5 results. Although only a single paper was found, it was highly relevant and matched the intent of the query well. The reason for retrieving only one paper lies in the nature of the database content: relatively few papers specifically focused on soil erosion and satellite image analysis together. Since the system ranks based on chunk-level semantic similarity, the top chunks retrieved likely all belonged to this one paper, resulting in only one unique paper being returned. This reflects a trade-off in the current design: while chunk-level retrieval improves relevance, it does not guarantee diversity in terms of the number of different papers.

Example 2 - "What are the recent machine learning methods used for mapping land cover changes in regions affected by deforestation?"

Top results:

TreeFormers -- An Exploration of Vision Transformers for Deforestation Driver Classification;

Deep Learning tools to support deforestation monitoring in the Ivory Coast using SAR and Optical satellite imagery;

Mapping Africa Settlements: High Resolution Urban and Rural Map by Deep Learning and Satellite Imagery;

Contrasting local and global modeling with machine learning and satellite data: A case study estimating tree canopy height in African savannas;

Dargana: fine-tuning EarthPT for dynamic tree canopy mapping from space.

This more complex query returned five distinct papers that relate to the use of machine learning for environmental mapping tasks, particularly in deforestation contexts. This demonstrates the system’s strength in handling longer and more specific questions that mention multiple topics. The results reflect a good semantic understanding of the query's components, even when phrased naturally in question form. One of the key advantages of the system is its ability to go beyond keyword matching by using dense vector representations of text (embeddings). This allows it to return semantically relevant results, even when the user does not use exact terms from the papers. As shown in the second example, the system successfully connected concepts like "machine learning", "deforestation", and "land cover change" to the content of the papers. The system does not currently aggregate similarity scores at the paper level, so showing an overall “paper similarity score” is not possible. Only the chunk-level match is evaluated, which may not reflect the relevance of the entire paper.

3.2.2. Answer Generation

This part of the system shows how the app can answer user questions by using a language model and similarity search. When a user types a question, the system turns it into a vector and searches for the most similar content in the database. There are two ways to ask a question. The first way is to select one specific paper. In this case, the app only searches through the text chunks of that paper and returns the most relevant ones. This usually gives the most accurate results because the search is focused only on one paper that the user is interested in. The second way is to select "all papers," where the app searches through both the summaries and the content chunks of every paper in the database and returns the parts that best match the question. For example, in

Table 2, we show what kind of answers the system gives in different situations.

One of the papers used in this example is SSL-SoilNet: A Hybrid Transformer-based Framework with Self-Supervised Learning for Large-Scale Soil Organic Carbon Prediction, which explores self-supervised learning (SSL) in the context of soil data. When the user asks, "How can self-supervised learning be used to improve predictions of soil properties?", the app provides a relevant answer both when this specific paper is selected and when all papers are searched. This is because the question uses general terms that are common in both summaries and content chunks. However, when the user asks a more specific question such as "How does SSL-SoilNet improve SOC prediction over traditional methods?", the system gives a detailed and accurate answer only when the SSL-SoilNet paper is explicitly selected. When all papers are selected, the app returns a message saying it does not have enough information. This happens because specific terms like "SSL-SoilNet" or "SOC" (Soil Organic Carbon) may not appear clearly or often enough in the summaries of other papers, and so the system fails to retrieve the right content. Additionally, embedding models are often trained on general vocabulary and may not produce accurate vector representations for rare or technical acronyms, which limits their ability to match such queries to the correct documents. The last example in the table, about coral reef preservation methods, shows what happens when the database does not contain any relevant content. In this case, the app correctly says it does not have enough information to answer the question, which confirms that the system is working as intended when there is no match. These results show that the app gives the most reliable answers when a specific paper is selected, especially for technical or detailed questions. They also show that combining both summaries and chunks when searching all papers improves the chance of getting a helpful answer for more general questions. This makes the system flexible and accurate for both broad and narrow types of queries.

3.2.3. Citation Generation

As part of the system functionality, automatic citation generation was implemented to support academic writing and referencing. The tool creates formatted citations based on metadata retrieved for each selected paper, supporting common citation styles (e.g., APA, MLA, ISO 690, etc.). To demonstrate how this feature performs in practice, we tested APA-style citations on a sample of papers with different types of publication, as shown in

Table 3. While the system handled arXiv preprints well, correctly formatting author names and including arXiv identifiers, several issues were observed with published journal or book chapters. These problems arise primarily from inconsistencies in the source metadata and limitations in the regular expression logic used to extract and format the citation components. This suggests that while the citation generator is a useful aid for quickly producing reference drafts, its output should be carefully checked and corrected by the user. Improvements could include integrating with more reliable metadata sources such as CrossRef, using structured APIs, and adding fallbacks when certain fields are missing.

3.2.4. Similarity Graph

Figure 9 shows how different research papers are connected based on how similar their content is. Each circle in the graph represents one paper, and the connections (called edges) between them show how closely related they are in terms of content. The system measures similarity using a number between 0 and 1, higher means more similar. In this example, the red circles represent the papers that were selected as the starting points for the graph. All other papers shown in light blue are the ones most closely related to the selected ones. Each paper is labeled simply as "Paper" followed by its ID, and when you hover over a node in the interactive version, you can see the title and a summary of that paper. The similarity between papers is computed using their summary embeddings, which capture the overall meaning of each paper's abstract or description. The lines between the papers are color-coded based on how strong the similarity is:

Green lines show a very high similarity (above 0.85);

Orange lines show a moderately high similarity (between 0.75 and 0.85);

Grey lines represent weaker but still meaningful similarity (between 0.65 and 0.75).

This graph is helpful for quickly seeing clusters of papers that are likely talking about the same topic, and it helps users explore related research more easily, even if they didn’t originally know which papers were connected.

Generated related work

The application also includes a feature for generating a "Related Work" section automatically. This functionality is designed to help users quickly create academic summaries by combining and rewriting the key ideas from selected papers. The system works by taking the summaries of the selected papers, combining them into a prompt, and asking the language model to write a coherent and well-structured academic paragraph. Citations are added inline during generation based on the selected metadata. One example of a generated related work section is shown in

Figure 10.

To optimize efficiency and reduce output length, the language model is instructed not to include full citation details at the end of the text. Instead, those citations are generated separately on the backend and presented in a dedicated section below the generated paragraph. Users can obtain the full reference list by clicking the "Generate citations for selected papers" button. These citations are formatted according to the chosen academic style and returned using structured metadata stored in the database, rather than generated by the language model. An example of the generated citation output can be seen in

Figure 11. The quality of the related work generated depends mostly on the quality of the paper summaries stored in the database and the ability of the language model to recognize shared themes. For example, when five papers were selected that all discuss the use of self-supervised learning in remote sensing, the generated text successfully grouped the studies by topic and gave a short explanation of each one. Each paper was briefly introduced with the authors and year, followed by a sentence about the main idea or method proposed in the paper. The generated paragraph was readable, structured logically, and followed typical academic writing style. It even ended with a short general comment about the importance of the topic and suggestions for future research. Although the text generated is not always perfect, it can serve as a strong first draft for the user. Users may still need to check the formatting of citations and edit the phrasing for clarity or correctness. However, this tool can save a significant amount of time in the early stages of writing academic papers and reduce the need to manually summarize each study. This feature was tested with different combinations of papers, and the results consistently reflected the ability of the system to highlight relevant connections between papers and produce text that flows naturally. It is most effective when the selected papers belong to the same research area or share a common topic.

3.3. Retrieval Performance Metrics

To evaluate the effectiveness of the retrieval component in the system, we measured four commonly used information retrieval metrics: Recall@3, MRR@3 (Mean Reciprocal Rank), Precision@3 and MAP@3 (Mean Average Precision). The choice of @3 reflects the scope and scale of the underlying database, which contains a relatively modest number of documents. In smaller collections, retrieving a larger number of top results (e.g., @10 or @20) may dilute the specificity of evaluation and introduce noise, as the pool of truly relevant documents per query is limited. By focusing on the top 3 results, we prioritize evaluating whether the system can retrieve the most semantically relevant content with high precision and ensure that returned results are not only correct but ranked appropriately. This approach also mirrors realistic usage patterns, where users typically examine only the top few results returned by a search interface. Each metric captures a different aspect of retrieval quality. To compute Recall and MRR, we generated 300 queries using a language model, where each query was crafted to match a specific chunk in the database of 41,277 entries. For Precision and MAP, we embedded the titles of 998 papers and checked whether the top 3 retrieved chunks belonged to the same document, which serves as a proxy for relevance. While not perfect, these methods offer a consistent way to evaluate system behavior. We compared three retrieval strategies: a traditional TF-IDF approach, a semantic search system based on dense vector embeddings without indexing, and the same embedding-based system using an HNSW index for faster approximate nearest neighbor retrieval. The results are shown in

Table 4. As expected, the embedding-based approaches outperform the traditional TF-IDF baseline across all accuracy metrics, indicating better semantic understanding and more relevant ranking of results. The highest accuracy is observed when using embeddings without any indexing, but this comes at a significantly higher computational cost (average latency of 508.74ms per query). Introducing the HNSW index offers a strong trade-off, maintaining high retrieval accuracy while cutting query time by more than half. Interestingly, the TF-IDF baseline still performs reasonably well considering its simplicity, which is expected given the relatively small and clean dataset. Overall, the results demonstrate that semantic search with vector embedding provides a substantial benefit in retrieval quality, while approximate indexing techniques like HNSW help ensure the system remains responsive in practice.

The system also supports generating a paper similarity graph, which visualizes top-N related connections between a set of selected papers and their most similar neighbors. This process involves computing pairwise cosine similarities between embeddings and is computationally more expensive than basic retrieval. For example, generating a graph for 50 papers takes around 8 seconds, whereas retrieving the top 50 most similar papers for a query typically completes in under one second. This contrast highlights the difference between one-to-many vector comparisons (used in retrieval) and the many-to-many comparisons required for graph construction. The graph generation time grows with the number of selected and compared papers, since the underlying operation scales approximately with O(N × M), where N is the number of selected papers and M is the number of candidates compared against. Optimizing this further could involve incorporating approximate similarity techniques (e.g., HNSW or Faiss) during graph construction as well.

We also measured the time required for generating an answer to a user query using the Mistral 7B language model. The model itself takes approximately 1.7 seconds to generate a response of around 160 tokens, which aligns with reported token generation speeds of up to 123 tokens/second for Mistral 7B

[18], depending on the hosting backend and inference configuration. However, the total time to answer a query is around 3.3 seconds. This includes several additional steps: connecting to the database, embedding the user query on the CPU (Central Processing Unit), retrieving the top 3 most relevant chunks based on vector similarity, and packaging this context to be sent to the model.

4. Discussion

The system developed in this work demonstrates the feasibility and practical value of combining semantic search, citation generation, and research paper exploration into a single unified web platform. By leveraging vector-based similarity search through pgvector and self-hosted embeddings, the application enables users to retrieve relevant paper content based on natural-language queries with high Recall and Precision. Evaluation results demonstrate that the embedding-based retrieval approach outperforms the TF-IDF baseline across all tested metrics. Notably, it achieves Recall@3 of 0.8633, MRR@3 of 0.82, Precision@3 of 0.86, and MAP@3 of 0.96, highlighting the effectiveness of dense semantic representations in capturing meaning beyond surface-level keyword overlap. Despite the relatively limited dataset of 998 papers and 41,277 text chunks, the system was able to support core functionalities such as top-N document retrieval, paper similarity graphs, and generation of related work sections using a lightweight LLM (Mistral 7B). Retrieval latency remained low even with full-table scans or HNSW indexing, confirming the efficiency of the solution for real-time use. While the system did not include advanced query rewriting, reranking, or feedback-based personalization, results indicate that even simple embedding-based matching yields useful academic retrieval in niche domains.

Despite solid performance, some unresolved issues in the data pipeline, particularly regarding preprocessing and formatting, may impact accuracy in edge cases. The text extraction process did not include any form of preprocessing, mathematical expressions, line breaks, formatting inconsistencies, and whitespace artifacts were left intact. This absence of structured document handling, especially given the varied formatting of scientific PDFs, likely affected semantic retrieval. Additionally, the quality of LLM-generated queries occasionally suffered from ambiguity, leading to less precise chunk matching. These factors highlight the need for more integrated preprocessing and query-generation strategies. Nevertheless, the application demonstrates the practical viability of combining retrieval-augmented generation, vector search, and LLM-based synthesis into a research-focused assistant. The system’s performance on Recall, Precision, and answer generation shows that, even under lightweight infrastructure and partial metadata, meaningful academic support tools can be developed. With scaled data ingestion, improved preprocessing, and model upgrades, this prototype can evolve into a much more powerful research assistant.

While the application demonstrates strong capabilities in semantic retrieval, citation generation, and research assistance, several limitations constrain its current scale and generalization. One of the most significant bottlenecks is the storage restriction imposed by Supabase’s free tier, which limits the PostgreSQL database to 500 MB. As a result, only 998 papers and 41,277 text chunks could be stored, which impacts both the performance and representativeness of retrieval evaluation. Each arXiv API query can return a maximum of 300 papers for a specific date range, which limited the number of relevant papers it could retrieve in a single request. To overcome this, pagination or splitting the date range into smaller intervals would be necessary. This may have led to the omission of relevant papers, especially in fast-growing fields like “remote sensing”. The arXiv API does not allow domain-specific filtering during the query phase, so we had to scrape a broader set of papers and filter them afterward, often resulting in many irrelevant results. Additionally, without using exact-match syntax (e.g., quotation marks), the API sometimes returned loosely related papers due to partial or fuzzy keyword matches. Furthermore, many papers lacked a LaTeX source format, forcing text extraction from PDFs, which are highly inconsistent in structure. This made it difficult to segment text into meaningful sections like “Methodology” or “Results,” reducing the granularity of retrieval and downstream LLM tasks. Another technical limitation arises in citation parsing. Since arXiv journal references vary widely in formatting, relying on regex-based parsing introduced edge cases and inconsistency, especially for non-standard journal entries. Together, these issues highlight that the system’s biggest constraint is not modeling, but the quality and volume of its underlying data infrastructure.

Future improvements to the system could significantly expand its utility, accuracy, and performance. First, increasing storage capacity and removing current hosting limits would allow indexing a much larger corpus of academic papers, leading to more diverse and accurate retrieval. If possible, migrating to a backend with scalable vector storage (e.g., using Pinecone, Weaviate, or cloud-hosted pgvector with larger limits) would open the door to handling tens or hundreds of thousands of documents. Improving the PDF processing pipeline is also a priority. The current implementation relies on unprocessed and unstructured document inputs, with no text normalization, section detection, or cleanup applied during PDF extraction. Additionally, stronger embedding models could replace the current sentence transformer, improving semantic understanding. Similarly, newer LLMs could be used for tasks like summarization, related work generation, or query synthesis to enhance overall quality and reduce generation errors. Other potential improvements include adding fine-grained filtering by research area, enabling users to explore papers by topic or method. A personalized recommendation module could also be introduced, using past queries or read papers to suggest new content. Lastly, citation generation could be improved by integrating external sources such as CrossRef, Semantic Scholar, or OpenAlex, to retrieve accurate publication metadata instead of relying solely on inconsistent arXiv entries.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.H., M.B.B. and V.M..; methodology, M.H.; software, M.H.; validation, M.H.; formal analysis, M.B.B., V.M.; investigation, M.H.; writing—original draft preparation, M.H..; writing—review and editing, M.B.B., V.M.; visualization, M.H.; supervision, M.B.B..; project administration, M.B.B.; funding acquisition, V.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the European Union's Horizon Europe research and innovation programme under grant agreement No. 101086179.

Data Availability Statement

The data utilized in this study comprises approximately 1,000 research papers sourced from the arXiv repository, which are publicly available online at

https://arxiv.org/.

Acknowledgments

The AI4SoilHealth project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon Europe research and innovation programme under grant agreement No. 101086179.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| RAG |

Retrieval-Augmented Generation |

| PDF |

Portable Document Format |

| RGB |

Retrieval-Augmented Generation Benchmark |

| TF-IDF |

Term Frequency-Inverse Document Frequency |

| LSA |

Latent Semantic Analysis |

| LLM |

Large Language Model |

| RNN |

Recurrent Neural Network |

| LSTM |

Long Short-Term Memory |

| GPT |

Generative Pre-trained Transformer |

| T5 |

Text-to-Text Transfer Transformer |

| BART |

Bidirectional and Auto-Regressive Transformer |

| APA |

American Psychological Association |

| MLA |

Modern Language Association |

| ISO 690 |

International Organization for Standardization |

| IEEE |

Electrical and Electronics Engineers |

| AMA |

American Medical Association |

| ACS |

American Chemical Society |

| DOI |

Digital Object Identifier |

| CSS |

Cascading Style Sheets |

| IVFFlat |

Inverted File Flat |

| HNSW |

Hierarchical Navigable Small World |

| NLTK |

Natural Language Toolkit |

| MB |

Megabyte |

| ID |

Identification |

| SQL |

Structured Query Language |

| MRR |

Mean Reciprocal Rank |

| MAP |

Mean Average Precision |

| SSL |

Self-supervised Learning |

| SOC |

Soil Organic Carbon |

| API |

Application Programming Interface |

| CPU |

Central Processing Unit |

References

- Lewis, P.; Perez, E.; Piktus, A.; Petroni, F.; Karpukhin, V.; Goyal, N.; Küttler, H.; Lewis, M.; Yih, W.; Rocktäschel, T.; Riedel, S.; Kiela, D. Retrieval-augmented Generation for Knowledge-intensive NLP Tasks. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2020, 33, 9459–9474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuster, K.; Poff, S.; Chen, M.; Kiela, D.; Weston, J. Retrieval Augmentation Reduces Hallucination in Conversation. arXiv Prepr. arXiv:2104.07567 2021. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, Y.; Cui, L.; Cai, D.; Liu, L.; Fu, T.; Huang, X.; Zhao, E.; Chen, Y.; Wang, L.; Luu, A.T.; Bi, W.;

Shi, F.; Shi, S. Siren's Song in the AI Ocean: A Survey on Hallucination in Large Language Models. arXiv Prepr. arXiv:2309.01219 2023 [CrossRef]

- Izacard, G.; Lewis, P.; Lomeli, M.; Hosseini, L.; Petroni, F.; Schick, T.; Dwivedi-Yu, J.; Joulin, A.; Riedel, S.; Grave, E. Atlas: Few-shot Learning with Retrieval Augmented Language Models. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2023, 24, 1–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Xiong, Y.; Gao, X.; Jia, K.; Pan, J.; Bi, Y.; Dai, Y.; Sun, J.; Wang, H. Retrieval-augmented Generation for Large Language Models: A Survey. arXiv Prepr. arXiv:2312.10997 2023, 2, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arslan, M.; Ghanem, H.; Munawar, S.; Cruz, C. A Survey on RAG with LLMs. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2024, 246, 3781–3790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.A.; Hasan, M.T.; Kemell, K.K.; Rasku, J.; Abrahamsson, P. Developing Retrieval Augmented Generation (RAG) Based LLM Systems from PDFs: An Experience Report. arXiv Prepr. arXiv:2410.15944 2024. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wang, Z.; Gao, X.; Zhang, F.; Wu, Y.; Xu, Z.; Shi, T.; Wang, Z.; Li, S.; Qian, Q.; Yin, R.; Lv, C.; Zheng, X.; Huang, X. Searching for Best Practices in Retrieval-augmented Generation. arXiv Prepr. arXiv:2407.01219 2024. [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Lin, H.; Han, X.; Sun, L. Benchmarking Large Language Models in Retrieval-augmented Generation. Proc. AAAI Conf. Artif. Intell. 2024, 38, 17754–17762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Xu, F.F.; Gao, L.; Sun, Z.; Liu, Q.; Dwivedi-Yu, J.; Yang, Y.; Callan, J.; Neubig, G. Active Retrieval Augmented Generation. Proc. Conf. Empir. Methods Nat. Lang. Process. 2023, 7969–7992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radeva, I.; Popchev, I.; Doukovska, L.; Dimitrova, M. Web Application for Retrieval-augmented Generation: Implementation and Testing. Electronics 2024, 13, 1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naveed, H.; Khan, A.U.; Qiu, S.; Saqib, M.; Anwar, S.; Usman, M.; Akhtar, N.; Barnes, N.; Mian, A. A Comprehensive Overview of Large Language Models. ACM Trans. Intell. Syst. Technol. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.; Wang, X.; Wang, J.; Wu, Y.; Yang, L.; Zhu, K.; Chen, H.; Yi, X.; Wang, C.; Wang, Y.; Ye, W.; Zhang, Y.; Chang, Y.; Yu, P.S.; Yang, Q.; Xie, X. A Survey on Evaluation of Large Language Models. ACM Trans. Intell. Syst. Technol. 2024, 15, 1–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedro, R.; Castro, D.; Carreira, P.; Santos, N. From Prompt Injections to SQL Injection Attacks: How Protected is Your LLM-integrated Web Application? arXiv Prepr. arXiv:2308.01990 2023. [CrossRef]

- Kasneci, E.; Sessler, K.; Küchemann, S.; Bannert, M.; Dementieva, D.; Fischer, F.; Gasser, U.; Groh, G.; Günnemann, S.; Hüllermeier, E.; Krusche, S.; Kutyniok, G.; Michaeli, T.; Nerdel, C.; Pfeffer, J.; Poquet, O.; Sailer, M.; Schmidt, A.; Seidel, T.; Stadler, M.; Weller, J.; Kuhn, J.; Kasneci, G. ChatGPT for Good? On Opportunities and Challenges of Large Language Models for Education. Learn. Individ. Differ. 2023, 103, 102274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrasekaran, D.; Mago, V. Evolution of semantic similarity—a survey. ACM Comput. Surv. 2021, 54, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, Ł.; Polosukhin, I. Attention is All You Need. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2017, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- pgvector. Available online: https://github.com/pgvector/pgvector (accessed on 12 July 2025).

- Jiang, A.Q.; Sablayrolles, A.; Mensch, A.; Bamford, C.; Chaplot, D.S.; de las Casas, D.; Bressand, F.; Lengyel, G.; Lample, G.; Saulnier, L.; Lavaud, L.R.; Lachaux, M.-A.; Stock, P.; Le Scao, T.; Lavril, T.; Wang, T.; Lacroix, T.; El Sayed, W. Mistral 7B. arXiv Prepr. arXiv:2310.06825 2023. [CrossRef]

- Artificial Analysis. Available online: https://artificialanalysis.ai/models/mistral-7b-instruct/providers/prompt-options/single/medium#summary (accessed on 12 July 2025).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).