1. Introduction

Numerous traits have been effectively linked to specific areas of the genome by genome-wide association studies (GWAS) [

1]. The process by which variations impact the phenotype they are linked to, however, is still unclear for many of these observations [

2]. The majority of trait-associated variations found by GWAS are thought to function by changing gene expression rather than the protein coding and are found in regulatory areas of the genome [

3]. This hypothesis is supported by the discovery of overlaps between GWAS risk variants and genomic loci influencing markers of genome regulation (like histone modifications) and enrichment of expression quantitative trait loci (eQTLs) at identified GWAS risk loci [

4,

5,

6,

7]. Therefore, combining GWAS with gene expression data is one way to improve knowledge of the processes behind GWAS findings.

DNA methylation is a key process in gene regulation. As such, it is an essential intermediary molecular trait that connects genes to other macro-level phenotypes and may contribute to missing heritability [

8]. Despite their physiological importance, the genetic drivers of DNA methylation patterns remain poorly understood. There is evidence that genetic variation at certain loci correlates with the quantitative characteristic of DNA methylation [

9,

10,

11,

12]. Additionally, previous studies discovered that genetic variants at CpG sites (meSNPs) can possibly disrupt the substrate of methylation reactions and thus, severely alter the methylation status at a single CpG site [

13,

14].

While methylation-associated single nucleotide polymorphisms (meSNPs) have been identified in various studies, it remains unclear whether they constitute a major class of methylation quantitative trait loci (meQTLs), or if they significantly influence the methylation status of nearby CpG sites [

9,

10,

11,

12]. Most meQTL studies to date have been limited by relatively small sample sizes and the use of low-resolution methylation microarrays, in which meSNPs are sparsely represented. Furthermore, many current meQTL analyses deliberately exclude probes overlapping with sequence variants to avoid confounding due to disrupted probe hybridization [

9,

10].

Pharmacoepigenetics explores the complex relationship between epigenetic modifications and pharmacological responses, emphasizing how drugs can both alter and be affected by epigenetic mechanisms [

15,

16]. Gaining insight into these epigenetic changes is essential in pharmacology, as it helps optimize drug efficacy, reduce adverse reactions, and drive forward the progress of personalized medicine. As a multidisciplinary and continuously evolving field, pharmacoepigenetics merges pharmacology, epigenetics, and other life sciences to shape innovative therapeutic strategies and uncover new drug targets [

17]. Alongside pharmacogenomics—a pharmacological sub-discipline focused on genetic variability in drug response—pharmacoepigenomics has emerged as a key area of interest. It concentrates on epigenetic therapy, the impact of epigenetic regulation on pharmacokinetics, and its implications in adverse drug reactions [

18].

Finally, both pharmacoepigenetics and pharmacogenomics play a vital role in advancing personalized medicine by shedding light on the intricate relationships between genes, epigenetic mechanisms, and drug responses [

18]. Here we introduce an innovative idea to test the Genomic-Epigenomic-Phenomic-Pharmacogenomics (G-E-Ph-PGx) axis by potential CpG-PGx SNPs (which their PGx roles are known) and possible CpG-PGx SNPs.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. General Design

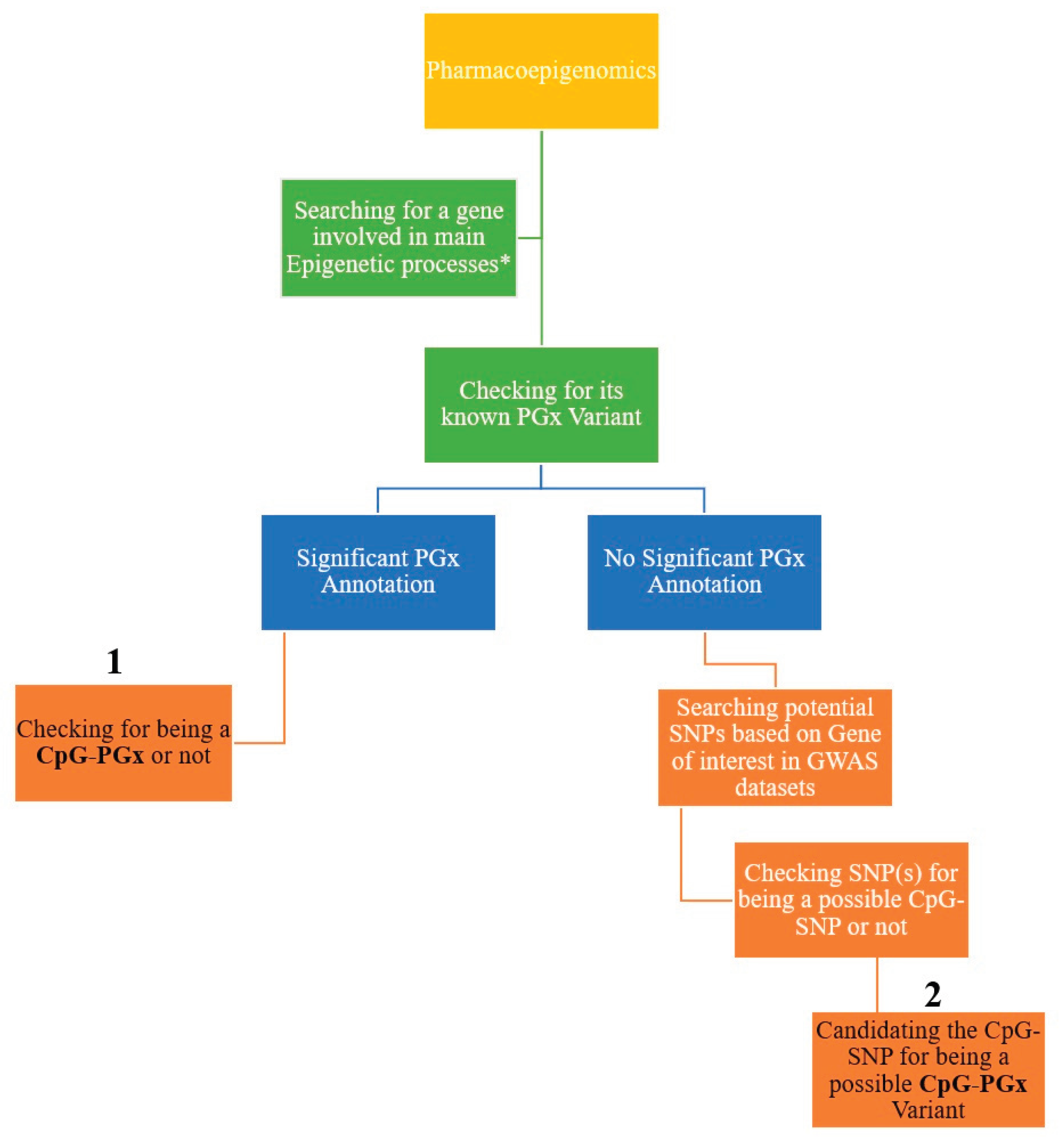

In the first step of this analysis, we analyzed the four major processes in epigenetics including methylation, demethylation, acetylation, and deacetylation. Then, we searched for the best-scored genes in each epigenetic process according to the relevance score of GeneCards (

https://www.genecards.org/) [

19]. Accordingly, we calculated the 1st -25th best-scored genes for each of the 4 epigenetic processes. In the next step, we checked every 100 genes in PharmGKB (

https://www.pharmgkb.org/) [

20] to see if they have at least one significant PGx annotation or not. Then, each PGx variant was subsequently checked if it is a CpG-PGx SNP or not. To find a new CpG-PGx SNP we investigated genes which had no significant PGx annotation in GWAS catalog (

https://www.ebi.ac.uk/gwas/home) [

21]. In the final step, we checked the potential SNPs (based on the best p-values) for being a possible CpG SNP or not. These CpG SNPs are suggested as new CpG-PGx SNPs in the results section. The whole process followed a hierarchal flow which in terms of either uncovering the potential roles of PGx annotations in epigenetic processes or finding new SNP candidates for being a pharmacoepigenetic factor (

Figure 1).

2.2. Data and Datasets

Applying GeneCards, we included 100 best-scored genes based on 4 epigenetic processes including methylation, demethylation, acetylation, and deacetylation (25 top genes of each one). It should be noted that all of the included genes were protein-coding due to the major interactions of Protein-Drugs in real-world findings and considering the highest confidence in introducing a new CpG-PGx SNP for future confirmations. As a well-known dataset, we stablished our strategy on PharmGKB information regarding its basis which consists of CPIC and DPWG as its main pillars. Finally, to check the suggesting new CpG-PGx SNPs, we utilized GWAS catalog for a gene of interest and refined the potential SNPs based on its classified data.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

According to our strategy of analysis, we prioritized and filtered genes, PGx annotations, and CpG-SNPs on various statistical scores which should be described for future investigations and add more clearance to the current study. In the first step, we utilized GeneCards data for finding the top genes in 4 epigenetic processes (methylation, demethylation, acetylation, and deacetylation) based on Elasticsearch 7.11 and also, Relevance score. Theory Behind Relevance Scoring is that Lucene (and thus Elasticsearch) utilizes the Boolean model to find matching documents, and a formula termed “the practical scoring function” to compute relevance. This formula, itself, borrows concepts from term frequency/inverse document frequency and the vector space model, however, adds more-modern characteristics such as a field length normalization, coordination factor, and term/query clause boosting. Supplementary boosting is provided for the annotations including the Symbol, Aliases and Descriptions, Accessions for the major bioinformatics databases (NCBI, Ensembl, SwissProt), Molecular function(s), Gene Summaries, Variants with Clinical Significance, and Elite disorders. The other database we used was PharmGKB which it turns, is a pharmacogenomics knowledge resource which incorporates clinical data including clinical guidelines and medication labels, associations of potentially clinically actionable gene-drug, and genotype-phenotype linkages. PharmGKB gathers, curates and publicizes knowledge regarding the effect of human genetic variation on drug responses via the several activities such as annotating the genetic variants and gene-drug-disease relationships via literature review, summarizing the vital pharmacogenomic genes, associations between genetic variants and drugs, and drug pathways, and curating FDA drug labels covering pharmacogenomic data. The main filtering step in PharmGKB was considering the significant p-value of lower than 0.05 for all obtained PGx annotations. Finally, we mined some genes of the primary list (remained/extracted from the step 1) in GWAS catalog and for adjusting False Discovery Rate (FDR), we considered the critical threshold of p-value <5E-08. This means we exactly included the most significant GWAS-based SNPs in the current study for increasing the validation of our predictions and narrowing the possibilities to be close to future real-world findings.

3. Results

As we described earlier in the Method section, the aim of this study is to open new windows into personalized medicine treatment by advancing PGx approaches. We believe that SNPs as the smallest genetic building blocks can have major impacts by playing multiple roles and have the potential to make bigger changes by additive functions (SNP-SNP interactions). Pharmacoepigenomics can be traced down by CpG-SNPs which have PG roles at the same time and as such we divided the data into more detail of the primary genes (100 genes having 4 major epigenetic impacts).

Initially, we obtained only best-scored protein-coding genes from GeneCards for each of 4 epigenetic processes. This was accomplished following a precise search in PharmGKB. Thus, we separated primary genes with at least 1 significant PGx annotation from genes with no PGx annotation archived in PharmGKB. This separation aligned with the two possible ways in finding CpG-PGx SNPs represented in

Figure 1. It should be clearly noted that a unique SNP may have one or more than one PGx annotation. A PGx annotation refers to a Variant-Drug-Association. More details are presented in the below.

3.1. Potential CpG-PGx SNPs

Table 1 summarizes the primary genes with epigenetic impact which have at least one significant PGx annotation based on PharmGKB. Accordingly, 22 unique genes out of 100 primary genes represented significant PGx annotation(s); notably, TP53, HDAC1, KAT2B, and SIRT1 were duplicated. TP53 is involved in Methylation, Acetylation, and Deacetylation; HDAC1, KAT2B, and SIRT1 are involved in Acetylation and Deacetylation process. The top Pharmacogene based on

Table 1 was CYP2C19 with 949 significant PGx annotations; also, CYP2D6 and CYP2B6 were the second and third best-scored Pharmacogenes with 733 and 383 significant annotations, respectively. Interestingly, COMT was the 7th best-scored Pharmacogene with 121 PGx annotations. In the next step, we searched each annotation for a potential CpG-PGx SNP.

Table 1 has a separate column showing this potential. Accordingly, the top gene based on the number of CpG-PGx SNP was CYP2B6 with 23 CpG-PGx SNPs followed by CYP2C19 with 21 CpG-PGx SNPs and CYP2D6 with 18 CpG-PGx SNPs. Remarkably, all of these genes are involved in the demethylation process and COMT (11 CpG-PGx SNPs) showed the top-scored gene among those are involved in Methylation process. Finally, 16 genes out of 22 genes revealed to have potential CpG-PGx SNPs (

Table 1).

In the next step, we focused on each CpG-PGx SNP to check its function (Missense, Synonymous, Intronic, Spicing, 3’UTR, 5’UTR, or being in regulatory region e.g. Enhancer). To do this, we exactly checked each CpG-PGx SNP in Genome Browser via Ensembl for its both major and minor alleles. This was done for finding the CpG site formation or disruption by allele change. This is a vital check to introduce a CpG-PGx SNP for further investigations. CpG site formation is basically hidden in the Genome Browser and if a minor allele will be a C in a dinucleotide of XpG (where X can be a A, T, or G allele) or a G in a dinucleotide of CpY (where Y can be a A, C, or T allele). On the other hand, CpG site disruption comes from a SNP in either C or G of a CpG dinucleotide site (actually, there might be ApG, TpG, GpG, CpA, CpT, or CpC dinucleotides).

Table 2 verifies each CpG-PGx SNP (based on known rsIDs) and its related gene, function, and CpG site situation. Generally, we found 99 CpG-PGx among them, 61 variants were missense variants, 25 variants were Intronic, 4 variants were 3’UTR, 4 variants were in a regulatory feature, 3 variants were Synonymous, 1 variant was a Spicing, and 1 variant was a Frameshift (

Table 2). CYP2D6 indicated a range for having various types of variants including missense, intronic, splicing, frameshift, and missense/inframeshift variants.

3.2. The Heart of Pharmacoepigenomics

Based on the well-known data in the PGx literature, CYP2D6 is known as the heart of pharmacogenetics, however, our findings suggested CYP2B6 as the top gene based on the number of CpG-PGx SNPs. To reach a more precise comparison among the three best-scored genes including CYP2B6, CYP2C19, and CYP2D6, we considered more factors including relevance score (obtained from GeneCards), number of significant PGx annotations (Obtained from PharmGKB), CpG-PGx SNPs (presented in the

Table 1), type of variants (based on the related SNP functions in

Table 2), Number of CpG site formations, Number of CpG site disruptions, and presenting in the title of papers indexed in PubMed (

Table 3). CYP2D6 showed the best factors (4 out of 7) including best relevance score (10.74248), having the most types of variants (5), highest number of CpG site formation (10), and highly impactful indexing (2,658 papers in their titles). We highly suggest that the other two genes (CYP2C19 and CYP2B6) represent potential candidates for being the hub genes of pharmacoepigenomics.

Diving into deeper layers of PEpGx, we extracted the remaining genes with no significant PGx Annotation and thereafter; by mining the related data of these genes in GWAS catalog, we refined the significant SNPs with p-value lower than 5E-08 and Minor Allele Frequency (MAF) of higher than 0.05. Finally, we checked them in the Genomic Region browser (

https://www.ensembl.org/index.html?redirect=no) to find 1) if they can form a new CpG site (CpG forming) or 2) disrupt a present CpG site (CpG Disruptive).

Final novel CpG-SNPs are proposed for checking their PGx associations to confirm whether each of them can be a novel CpG-PGx SNP. This is the second pathway of the main idea described in

Figure 1. According to the results indicated in

Table 4, for all of the remaining 69 genes (some genes were involved in more than one epigenetic process), we mined 1,230 significant GWAS associations (or SNPs),

which revealed 329 CpG-SNPs related to 48 genes with at least one CpG site formation or disruption. The top gene with the highest CpG-SNPs was

TET2 (42 CpG-SNPs), followed by

JMJD1C (35 CpG-SNPs), and

HDAC9 (26 CpG-SNPs) in the second and third places, respectively. Interestingly, the demethylation process not only was the most important process, but also demethylation was present in the second, third, fourth, and fifth places. The other most important process was methylation by

GRIN2A (13 CpG-SNPs).

In the next step, we separated the CpG-Disruptive SNPs from CpG-Forming SNPs. Totally, we found 173 CpG-Disruptive SNPs, 155 CpG-Forming SNPs, and just 1 CpG SNP with both disruptive and forming impacts (it can be between 2 CpG sites and disrupts one and form the second one as a new CpG site). One example we found was the intronic SNP (rs34770920) of ACAA2 gene. Moreover, we found an interesting epigenetic impact in synonymous SNPs which agrees with our previous result in potential CpG-PGx SNPs sub-section. More specifically, we found some CpG-SNPs in the Epigenetically Modifiable Accessible Region (EMAR) such as rs10849885 (KDM2B; synonymous; MAF: 0.5; CpG-Disruptive SNP), rs1667619 (TET3; synonymous; MAF: 0.47; CpG-Disruptive SNP), rs601999 (NAGLU; synonymous; MAF: 0.29; CpG-Forming SNP), and rs591939 (NAGLU; synonymous; MAF: 0.18; CpG-Forming SNP).We hereby propose that these synonymous CpG-SNPs cannot change the amino acid sequence and in result, the protein structure, also, they may have not reflect visible impacts on the “Human Genome”, but they still can be a CpG-Forming SNP and are involved in the regulatory mechanisms.

In the last step, we tried to classify both CpG-Disruptive SNPs and CpG-Forming SNPs based on their MAFs. Such this standpoint comes from an undeniable rule of statistical and epidemiological genetics which define the possibilities of carrying SNPs by individuals and in a wider view in various populations. In

Table 4 and

Table 5, all CpG-SNPs are presented from the most to the least common along with their functions. In this regard, there were 9 CpG-Disruptive SNPs including with the MAF of 0.5 (the highest prevalence) and 4 CpG-Disruptive SNPs with the MAF of 0.05 (the smallest prevalence).

The most prevalent CpG-Disruptive SNPs were rs2984348 (

HDAC8; Enhancer), rs13245206 (

HDAC9; Intronic); rs10237149 (

HDAC9; Intronic), rs6951745 (

HDAC9; Intronic), rs10849885 (

KDM2B; Synonymous/ EMAR), rs12001316 (

KDM4C, Intronic), rs3814177 (

TET1; 3’UTR), rs9884984 (

TET2; Intronic); and rs6533183 (

TET2; Intronic) (

Table 4).

Accordingly, in group of CpG-Forming SNPs, we found 13 CpG-SNPs with the highest prevalence (MAF= 0.5) and 3 CpG-SNPs with the lowest prevalence (MAF=0.05). The most prevalent CpG-Foming SNPs included rs1931537 (

AR; 3’UTR), rs2116942 (

DNMT1; Missense), rs1935 (

JMJD1C; Missense), rs7962128 (

KDM2B; 3’UTR), rs6489811 (

KDM2B; Intronic), rs2613766 (

KDM4B; Intronic), rs7042372 (

KDM4C; Intronic/ EMAR/ Enhancer), rs960658 (KDM4C; Intronic), rs7037266 (KDM4C, Intronic), rs5969750 (RBBP7;3’UTR), rs7670522 (TET2; 3’UTR), rs9884296 (TET2; Intronic), and rs5952279 (KDM6A; Intronic) (

Table 5).

Table 5.

List of possible CpG-SNPs leading to Formation of a CpG site (novel CpG site) according to the remained genes of GWAS mining.

Table 5.

List of possible CpG-SNPs leading to Formation of a CpG site (novel CpG site) according to the remained genes of GWAS mining.

| SNPS |

Gene |

MAF |

Func |

| rs1931537 |

AR |

0.5 |

3’UTR |

| rs2116942 |

DNMT1 |

0.5 |

Missense |

| rs1935 |

JMJD1C |

0.5 |

Missense |

| rs7962128 |

KDM2B |

0.5 |

3’UTR |

| rs6489811 |

KDM2B |

0.5 |

Intronic |

| rs2613766 |

KDM4B |

0.5 |

Intronic |

| rs7042372 |

KDM4C |

0.5 |

Intronic/ EMAR/ Enhancer |

| rs960658 |

KDM4C |

0.5 |

Intronic |

| rs7037266 |

KDM4C |

0.5 |

Intronic |

| rs5969750 |

RBBP7 |

0.5 |

3’UTR |

| rs7670522 |

TET2 |

0.5 |

3’UTR |

| rs9884296 |

TET2 |

0.5 |

Intronic |

| rs5952279 |

KDM6A |

0.5 |

Intronic |

| rs4827402 |

AR |

0.49 |

Intronic |

| rs739842 |

HDAC7 |

0.49 |

Intronic/ Enhancer |

| rs10995505 |

JMJD1C |

0.49 |

Intronic |

| rs62647699 |

KDM4B |

0.49 |

Intronic |

| rs9876116 |

MLH1 |

0.49 |

Intronic |

| rs10193548 |

HDAC4 |

0.48 |

Intronic |

| rs6658300 |

KDM4A |

0.48 |

Intronic |

| rs8089411 |

MBD2 |

0.48 |

Intronic |

| rs7616853 |

SLC33A1 |

0.48 |

Intronic |

| rs9949052 |

ACAA2 |

0.47 |

Intronic |

| rs9676981 |

KDM4B |

0.47 |

Intronic |

| rs6794232 |

SLC33A1 |

0.47 |

Intronic |

| rs10237366 |

HDAC9 |

0.46 |

Intronic |

| rs17429745 |

TET2 |

0.46 |

Intronic |

| rs62331124 |

TET2 |

0.46 |

Intronic |

| rs10998356 |

TET1 |

0.45 |

Intronic |

| rs1097784 |

GRIN2A |

0.44 |

Intronic |

| rs4852018 |

HDAC4 |

0.44 |

Intronic |

| rs661818 |

HDAC9 |

0.44 |

Intronic/ Enhaner |

| rs9646283 |

CDH1 |

0.43 |

Intronic |

| rs9415676 |

JMJD1C |

0.43 |

Intronic |

| rs11865499 |

KAT8 |

0.43 |

Intronic |

| rs4911257 |

DNMT3B |

0.42 |

Intronic |

| rs2647239 |

TET2 |

0.42 |

Intronic |

| rs2466920 |

TET2 |

0.42 |

Intronic |

| rs2454206 |

TET2 |

0.42 |

Missense |

| rs12150830 |

ACAA2 |

0.41 |

Intronic |

| rs10761765 |

JMJD1C |

0.41 |

Intronic |

| rs1868289 |

GRIN2A |

0.4 |

Intronic |

| rs12241767 |

TET1 |

0.4 |

Missense |

| rs10822163 |

JMJD1C |

0.39 |

Intronic |

| rs7923609 |

JMJD1C |

0.39 |

Intronic |

| rs10822160 |

JMJD1C |

0.39 |

Intronic |

| rs7095571 |

JMJD1C |

0.39 |

Intronic |

| rs10761771 |

JMJD1C |

0.39 |

Intronic |

| rs4405189 |

JMJD1C |

0.39 |

Intronic |

| rs10444491 |

KDM2B |

0.39 |

Intronic |

| rs609292 |

HDAC5 |

0.38 |

Intronic/ Enhancer |

| rs7031625 |

KDM4C |

0.38 |

Intronic |

| rs7683416 |

TET2 |

0.38 |

Intronic |

| rs7070693 |

JMJD1C |

0.37 |

Intronic/ EMAR/ Enhancer |

| rs2285657 |

KAT2A |

0.37 |

Intronic |

| rs4807687 |

KDM4B |

0.37 |

Intronic/ EMAR/ Enhancer |

| rs35158985 |

CDH1 |

0.36 |

Intronic |

| rs9925964 |

KAT8 |

0.36 |

Splicing/ Enhancer/ EMAR |

| rs34770920 |

ACAA2 |

0.36 |

Intronic |

| rs8093891 |

ACAA2 |

0.35 |

Intronic |

| rs1900101 |

ACACA |

0.35 |

Intonic |

| rs7201930 |

GRIN2A |

0.35 |

Intronic |

| rs7812296 |

HDAC9 |

0.35 |

3’UTR |

| rs10761737 |

JMJD1C |

0.35 |

Intronic |

| rs9414802 |

JMJD1C |

0.35 |

Intronic |

| rs9795476 |

SIRT3 |

0.35 |

Intronic/ EMAR |

| rs710956 |

KDM4B |

0.34 |

Intronic |

| rs2647234 |

TET2 |

0.34 |

Intronic |

| rs9964304 |

ACAA2 |

0.33 |

Intronic |

| rs7190785 |

GRIN2A |

0.33 |

Intronic |

| rs169080 |

KDM4B |

0.33 |

Intronic |

| rs7191183 |

GRIN2A |

0.32 |

Intronic |

| rs8088929 |

ACAA2 |

0.31 |

Intronic |

| rs7307046 |

HDAC7 |

0.31 |

Intronic |

| rs34550543 |

KDM4A |

0.31 |

Intronic/ EMAR/ Enhancer |

| rs7191999 |

GRIN2A |

0.3 |

Intronic |

| rs3791452 |

HDAC4 |

0.3 |

Intronic |

| rs4758633 |

SIRT3 |

0.3 |

Intronic |

| rs10902106 |

SIRT3 |

0.3 |

Intronic |

| rs62621450 |

TET2 |

0.3 |

Missense |

| rs1997797 |

DNMT3B |

0.29 |

Splicing |

| rs601999 |

NAGLU |

0.29 |

Synonymous/ EMAR/ Enhancer |

| rs28608872 |

CDH1 |

0.28 |

Intronic |

| rs7972177 |

HDAC7 |

0.28 |

Intronic |

| rs10975974 |

KDM4C |

0.28 |

Intronic |

| rs10022109 |

TET2 |

0.28 |

Intronic |

| rs10744776 |

ACACB |

0.27 |

Intronic |

| rs9646284 |

CDH1 |

0.27 |

Intronic |

| rs2424905 |

DNMT3B |

0.27 |

Intronic |

| rs137993948 |

KDM1A |

0.27 |

Intronic |

| rs79491673 |

MBD2 |

0.27 |

EMAR/ Enhancer |

| rs1023430 |

SIRT3 |

0.27 |

Intronic |

| rs350844 |

SIRT6 |

0.27 |

Intronic |

| rs904274 |

TET2 |

0.27 |

Intronic |

| rs2072945 |

KDM1A |

0.26 |

Intronic |

| rs57917116 |

KDM2B |

0.26 |

Intronic/ EMAR/ Enhancer |

| rs13103161 |

TET2 |

0.26 |

Intronic |

| rs2011779 |

CDH1 |

0.25 |

Intronic |

| rs4420522 |

CDH1 |

0.24 |

Intronic |

| rs2526639 |

HDAC9 |

0.24 |

Intronic |

| rs28540102 |

KDM4B |

0.24 |

Intronic |

| rs7208787 |

KDM6B |

0.24 |

EMAR |

| rs7661349 |

TET2 |

0.24 |

Intronic/ Promoter/ EMAR |

| rs1654885 |

ACACB |

0.23 |

Intronic |

| rs56137247 |

HDAC4 |

0.23 |

Intronic |

| rs11726786 |

TET2 |

0.23 |

Intronic |

| rs2133084 |

TET2 |

0.23 |

Intronic |

| rs6533181 |

TET2 |

0.23 |

Intronic |

| rs6087992 |

DNMT3B |

0.22 |

Intronic |

| rs3791478 |

HDAC4 |

0.22 |

Intronic |

| rs4507125 |

HDAC4 |

0.22 |

Enhancer |

| rs2030057 |

TET1 |

0.22 |

Intronic |

| rs11168236 |

HDAC7 |

0.21 |

Intronic |

| rs75601653 |

KAT5 |

0.21 |

Intronic |

| rs407258 |

SLC33A1 |

0.21 |

Intronic |

| rs1977825 |

TET1 |

0.21 |

Intronic |

| rs28628339 |

CDH1 |

0.2 |

Intronic |

| rs7510675 |

EP300 |

0.2 |

Intronic |

| rs4760624 |

HDAC7 |

0.2 |

Intronic |

| rs302177 |

HDAC9 |

0.2 |

Intronic |

| rs2393967 |

JMJD1C |

0.2 |

Intronic |

| rs4832290 |

KDM3A |

0.2 |

Intronic |

| rs2523162 |

HDAC5 |

0.19 |

Intronic |

| rs13243921 |

HDAC9 |

0.19 |

Intronic |

| rs2620832 |

KDM4B |

0.19 |

Intronic |

| rs6818511 |

TET2 |

0.19 |

Intronic |

| rs13632 |

HDAC7 |

0.18 |

3’UTR |

| rs3791033 |

KDM4A |

0.18 |

Intronic |

| rs591939 |

NAGLU |

0.18 |

Synonymous/ EMAR/ Enhancer |

| rs7499643 |

CREBBP |

0.17 |

Intronic |

| rs78628688 |

KDM2B |

0.17 |

Intronic |

| rs10010512 |

TET2 |

0.17 |

Intronic |

| rs7896294 |

JMJD1C |

0.16 |

Intronic |

| rs58324296 |

KDM4B |

0.16 |

3’UTR/ EMAR |

| rs12352785 |

KDM4C |

0.16 |

Intronic |

| rs61393039 |

HDAC9 |

0.15 |

Intronic |

| rs10975917 |

KDM4C |

0.13 |

Intronic |

| rs11662691 |

ACAA2 |

0.12 |

Intronic |

| rs2288937 |

DNMT1 |

0.12 |

Intronic/ Enhancer |

| rs34149349 |

HDAC7 |

0.12 |

Intronic |

| rs2894069 |

TET1 |

0.12 |

Intronic |

| rs7206296 |

GRIN2A |

0.09 |

Intronic |

| rs13337187 |

GRIN2A |

0.09 |

Intronic |

| rs12250472 |

JMJD1C |

0.09 |

Intronic |

| rs75321784 |

TET2 |

0.09 |

Intronic |

| rs17430251 |

TET2 |

0.09 |

Intronic |

| rs71524263 |

HDAC9 |

0.08 |

Intronic/ OpenChromatin/ EMAR |

| rs1549349 |

KDM2B |

0.08 |

Intronic |

| rs138578374 |

HDAC4 |

0.07 |

Intronic |

| rs2630452 |

HDAC11 |

0.07 |

Intronic |

| rs2655232 |

HDAC11 |

0.07 |

Intronic |

| rs62115563 |

KDM4B |

0.07 |

Intronic |

| rs2675229 |

HDAC11 |

0.06 |

Intronic |

| rs77074018 |

HDAC11 |

0.05 |

Intronic |

| rs41274072 |

JMJD1C |

0.05 |

Missense |

| rs61031471 |

KDM6B |

0.05 |

Missense |

4. Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first-ever paper introducing CpG-PGx SNP as a novel candidate in a Genomic-Epigenomic-Phenomic-Pharmacogenomics (GEPh-PGx) axis. GEPh-PGx suggests a complicated network of regulatory-functional interactions initiating from the smallest genetic block (SNP) to the broader cellular and molecular interplay leading to known and unknown phenotypes which in term, are linked to pharmacological interactions and treatments. Briefly, GEPh-PGx represents a new aspect of Personalized Medicine based on disruption or formation of a CpG site by allele changes in a SNP. This phenomenon clearly helps explain the trans-regulation processes in which these CpG sites can present or remove the possible epigenetic tags for Methylation/Demethylation reactions.

What we designed was a logical and comprehensive strategy of analysis based on the well-known and documented list of various genes in all 4 classical epigenetic processes including Methylation, Demethylation, Acetylation, Acetylation, and Deacetylation. In the current investigation, we mined the CpG sites for all these genes involved in methylation/demethylation and also included genes for acetylation and deacetylation processes. Therefore, we selected 100 genes and following removing the duplications (some genes were present in more than one epigenetic process like TP53), 91 unique genes remained. We followed two pathways including searching and introducing potential CpG-PGx SNPs and possible CpG-SNPs to be newly confirmed CpG-PGx SNPs. We found 3 major genes for having the highest number of potential CpG-PGx SNPs including CYP2B6, CYP2C19, andCYP2D6, among them, CYP2D6 was found to be the heart of pharmacoepigenomics. Finally, after a deep search based on GWAS data, we found TET2 as the top-scored candidate for future PGx confirmations according to its number of possible CpG-SNPs.

There are inadequate studies concerning CpG-SNPs (10 papers in PubMed with CpG-SNP in their titles). All the PubMed-indexed papers for CpG-SNPs can be divided into 3 main categories including Neuropsychological disorders such as suicidal behavior in subjects with schizophrenia [

22], psychosis [

23] and major depression disorder [

24], metabolic disorders including type 2 diabetes [

25,

26] and obesity [

27,

28], and cancer biology [

29].

Pharmacoepigenetics and Pharmacoepigenomics revealed a better result compared with CpG-SNPs in the literature. We found 24 papers in PubMed with the Pharmacoepigenetics or Pharmacoepigenomics in their titles. Interestingly, similar to the aforementioned 3 major categories, these papers focused on the same categories. Montagna was one of the first scientists who discussed the epigenetic and pharmacoepigenetics processes in primary headaches and pain [

30]. Leach et al reviewed pharmacoepigenetics in heart failure and cardiovascular disease (CVD) and concluded that because epigenetics has a vital role in shaping phenotypic variation in health and disease, understanding and manipulating the epigenome has massive capacity for the treatment and prevention of common human diseases [

31]. In the context of cancer, Candelaria et al with an emphasis on gemcitabine, reviewed an update of genetic and epigenetic bases that might account for inter-individual variations in therapeutic results [

32]. Accordingly, Nasr et al studied pharmacoepigenetics in breast cancer [

33], Fornaro et al reviewed pharmacoepigenetics in gastrointestinal cancer [

34], and Gutierrez-Camino et al reported pharmacoepigenetics in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia [

35]. In a meta-analysis, Chu and Yang systematically studied the population diversity impact of DNA methylation on the treatment response and drug ADME in various tissue and cancer types. They concluded that ethnicity should be cautiously considered for in future pharmacoepigenetics explorations [

36]. Notably, Nuotio et al performed a genome-wide methylation analysis of responsiveness to four classes of antihypertensive drugs in pharmacoepigenetics of hypertension [

37].

The last and most important topic in pharmacoepigenetics is psychological and behavioral phenotypes such as generalized anxiety disorder [

38], Alzheimer’s disease [

39], and depression [

40], and opioid addiction [

41].

Epigenetic variants have been found near genes and gene regulators, which control the metabolism of drugs, suggesting a role for epigenetic mechanisms in modulating pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics [

42,

43,

44]. Pharmacoepigenetics, is the field that studies how epigenetic variability impacts variability in drug response [

16]. Of note, Smith et al’s idea is completely consistent with our standpoint. They stated that first, we can detect variation in epigenetic markers, second, we can choose key epigenetic biomarker(s) in regions of variance, and third, we can map these biomarker(s) to a drug-response phenotype [

16]. Smith et al’s idea clearly agrees with our initial idea of a GEPh-PGx axis.

Since we found that the

TET2 gene was top, it is important to point out that it is — a key player in epigenetics, hematopoiesis, and cancer biology. Its full name is Tet methylcytosine dioxygenase 2 located on chromosome 4q24. TET2 is part of the TET family of enzymes, which convert 5-methylcytosine (5mC) to 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (5hmC), playing a role in DNA demethylation and epigenetic regulation. Specifically, TET2 is involved in regulation of gene expression; stem cell differentiation, especially in hematopoiesis (formation of blood cells); immune system regulation; epigenetic reprogramming during development. Interestingly, mutations in

TET2 are somatic (acquired) and commonly found in 1) Myeloid malignancies such as Myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS); acute myeloid leukemia (AML); Chronic myelomonocytic leukemia (CMML); Myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs), and 2) Lymphoid cancers such as Angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma (AITL) and Peripheral T-cell lymphoma (PTCL). It is also known that

TET2 mutations are among the most common in Clonal Hematopoiesis of Indeterminate Potential (CHIP), a condition where aging individuals develop hematopoietic clones without having full-blown cancer — but with an increased risk of cardiovascular disease and leukemia. Clinically,

TET2 mutations may signal different outcomes depending on the context of the disease. TET2-mutant cancers may respond differently to hypomethylating agents (like azacitidine or decitabine). Vitamin C (ascorbate) has been studied to enhance

TET activity and DNA demethylation in TET2-deficient cells (preclinical).

TET2 mutations often co-occur with others (e.g.,

ASXL1,

DNMT3A, IDH2), affecting disease progression and treatment [

45,

46].

The current study faced with some limitations which should be considered to be covered in the similar future investigations. First of all, we used GeneCards data which may get updates based on novel findings in the literature; thus, it should be considered that this study performed on July 2025. The other limitation may rely on the number of included genes which means that the future works should definitely generate a bigger primary gene list. The other issue may be lack of additional in silico investigations on trans-regulation interactions of both potential CpG-PGx SNPs and possible CpG-PGx SNPs; more clearly, a forming CpG site SNP should be check for its new positive/negative binding affinities. Obviously, the clinical and real-world confirmations are highly recommended for validating our findings.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, pharmacoepigenetics can provide novel insights into PGx approaches and describes complicated mechanisms involved in Personalized Medicine treatment options. CpG-PGx SNPs can represent novel potential biomarkers in PGx and epigenomics which requires more confirmation by real-world clinical findings. Based on our data we recommend that the scientific community intensively investigate the top-scored genes reported in the current study such as CYP2B, CYP2D6, CYP2C19, and TET2 with psychiatric and other related phenotypes. Additionally, in this study, we exposed some synonymous PGx SNPs that may be involved in a CpG-PGx Disruption/Formation processes as novel clues for their impact in PGx (potential CpG-PGx SNPs). We further found other synonymous CpG-SNPs in the EMAR confirming our primary results and highlighting the uncovered roles of synonymous SNPs in regulatory mechanisms instead of functional alterations in protein structures.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A. S. and K.B.; methodology, A.S.; software, A.S.; validation, A.S. and K.B.; formal analysis, A.S.; investigation, A.S.; resources, A.S.; data curation, A.S.; writing—original draft preparation, A.S., K.B., and K.U.L.; writing—review and editing, A.S., K.B., K.U.L., I.E., D.B., A.P., P.K.T., R.K.A.F., S.S., E.L.G., M.P.L., A.PL.L., and M.S.G.; visualization, A.S.; supervision, A.S. and K.B.; project administration, A.S.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

R21 DA045640/DA/NIDA NIH HHS/United States, I01 CX002099/CX/CSRD VA/United States, R33 DA045640/DA/NIDA NIH HHS/United States, R41 MD012318/MD/NIMHD NIH HHS/United States, I01 CX000479/CX/CSRD VA/United States.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Any further data will be available on a reasonable request from the corresponding author via email (alirezasharafshah@yahoo.com).

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

Dr. Kenneth Blum is the inventor of both GARS and KB220, which have been assigned to TranspliceGen Holdings, Inc. There are no other conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| GWAS |

Genome-Wide Association Studies |

| PGx |

Pharmacogenomics |

| PEpGx |

Pharmacoepigenomics |

| SNP |

Single Nucleotide Polymorphism |

| EMAR |

Epigenetically Modifiable Accessible Region |

| meQTLs |

methylation quantitative trait loci |

| G-E-Ph-PGx |

Genomic-Epigenomic-Phenomic-Pharmacogenomics |

| FDR |

False Discovery Rate |

| MAF |

Minor Allele Frequency |

References

- MacArthur, J. , et al., The new NHGRI-EBI Catalog of published genome-wide association studies (GWAS Catalog). Nucleic acids research, p: 45(D1).

- Gallagher, M.D. and A.S. Chen-Plotkin, The post-GWAS era: from association to function. The American Journal of Human Genetics.

- Maurano, M.T. , et al., Systematic localization of common disease-associated variation in regulatory DNA. Science, p: 337(6099), 6099. [Google Scholar]

- Nicolae, D.L. , et al., Trait-associated SNPs are more likely to be eQTLs: annotation to enhance discovery from GWAS. PLoS genetics, p: 6(4), 1000. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L. , et al., Genetic drivers of epigenetic and transcriptional variation in human immune cells. Cell, p: 167(5), 1398. [Google Scholar]

- Tehranchi, A.K. , et al., Pooled ChIP-Seq links variation in transcription factor binding to complex disease risk. Cell, 2016. 165(3): p. 730-741.

- Zhang, X. , et al., Identification of common genetic variants controlling transcript isoform variation in human whole blood. Nature genetics, p: 47(4).

- Maher, B. , Personal genomes: The case of the missing heritability. 2008, Nature Publishing Group UK London.

- Gibbs, J.R. , et al., Abundant quantitative trait loci exist for DNA methylation and gene expression in human brain. PLoS genetics, p: 6(5), 1000. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, J.T. , et al., DNA methylation patterns associate with genetic and gene expression variation in HapMap cell lines. Genome biology, 2011. 12(1): p. R10.

- Shoemaker, R. , et al., Allele-specific methylation is prevalent and is contributed by CpG-SNPs in the human genome. Genome research, p: 20(7).

- Zhang, D. , et al., Genetic control of individual differences in gene-specific methylation in human brain. The American Journal of Human Genetics, p: 86(3).

- Gertz, J. , et al., Analysis of DNA methylation in a three-generation family reveals widespread genetic influence on epigenetic regulation. PLoS genetics, p: 7(8), 1002. [Google Scholar]

- Hellman, A. and A. Chess, Extensive sequence-influenced DNA methylation polymorphism in the human genome. Epigenetics & chromatin.

- Majchrzak-Celińska, A. and W. Baer-Dubowska, Pharmacoepigenetics: an element of personalized therapy? Expert Opinion on Drug Metabolism & Toxicology.

- Smith, D.A., M. C. Sadler, and R.B. Altman, Promises and challenges in pharmacoepigenetics. Cambridge Prisms: Precision Medicine, p: 1.

- Bustin, S.A. and K.A. Jellinger, Advances in molecular medicine: unravelling disease complexity and pioneering precision healthcare. 2023, 1416. [Google Scholar]

- Griñán-Ferré, C. , et al., Advancing personalized medicine in neurodegenerative diseases: The role of epigenetics and pharmacoepigenomics in pharmacotherapy. Pharmacological Research, p: 205, 1072. [Google Scholar]

- Stelzer, G. , et al., The GeneCards suite: from gene data mining to disease genome sequence analyses. Current protocols in bioinformatics, p: 54(1).

- Whirl-Carrillo, M. , et al., An evidence-based framework for evaluating pharmacogenomics knowledge for personalized medicine. Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics.

- Cerezo, M. , et al., The NHGRI-EBI GWAS Catalog: standards for reusability, sustainability and diversity. Nucleic acids research, p: 53(D1), 1005. [Google Scholar]

- Polsinelli, G. , et al., Association and CpG SNP analysis of HTR4 polymorphisms with suicidal behavior in subjects with schizophrenia. Journal of Neural Transmission,.

- Van Den Oord, E.J. , et al., A whole methylome CpG-SNP association study of psychosis in blood and brain tissue. Schizophrenia bulletin, p: 42(4), 1018. [Google Scholar]

- Aberg, K.A. , et al., Convergence of evidence from a methylome-wide CpG-SNP association study and GWAS of major depressive disorder. Translational psychiatry, p: 8(1).

- Torkamandi, S. , et al., Association of CpG-SNP and 3’UTR-SNP of WFS1 with the Risk of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus in an Iranian Population. International Journal of Molecular and Cellular Medicine, p: 6(4).

- Vohra, M. , et al., CpG-SNP site methylation regulates allele-specific expression of MTHFD1 gene in type 2 diabetes. Laboratory Investigation, p: 100(8), 1090. [Google Scholar]

- Mansego, M.L. , et al., SH2B1 CpG-SNP is associated with body weight reduction in obese subjects following a dietary restriction program. Annals of Nutrition and Metabolism, 2015. 66(1): p. 1-9.

- de Toro-Martín, J. , et al., A CpG-SNP located within the ARPC3 gene promoter is associated with hypertriglyceridemia in severely obese patients. Annals of Nutrition and Metabolism, p: 68(3).

- Harlid, S. , et al., A candidate CpG SNP approach identifies a breast cancer associated ESR1-SNP. International journal of cancer, p: 129(7), 1689. [Google Scholar]

- Montagna, P. , Epigenetics and pharmaco-epigenetics in the primary headaches. The Journal of Headache and Pain, 193–194.

- Mateo Leach, I., P. Van Der Harst, and R.A. De Boer, Pharmacoepigenetics in heart failure. Current heart failure reports, p: 7(2).

- Candelaria, M. , et al., Pharmacogenetics and pharmacoepigenetics of gemcitabine. Medical oncology, p: 27(4), 1133. [Google Scholar]

- Nasr, R. , et al., The pharmacoepigenetics of drug metabolism and transport in breast cancer: review of the literature and in silico analysis. Pharmacogenomics, p: 17(14), 1573. [Google Scholar]

- Fornaro, L. , et al., Pharmacoepigenetics in gastrointestinal tumors: MGMT methylation and beyond. Front Biosci, p: 2016. 8, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Gutierrez-Camino, A. , et al., Pharmacoepigenetics in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia: involvement of miRNA polymorphisms in hepatotoxicity. Epigenomics, p: 10(4).

- Chu, S.-K. and H.-C. Yang, Interethnic DNA methylation difference and its implications in pharmacoepigenetics. Epigenomics, p: 9(11), 1437. [Google Scholar]

- Nuotio, M.-L. , et al., Pharmacoepigenetics of hypertension: genome-wide methylation analysis of responsiveness to four classes of antihypertensive drugs using a double-blind crossover study design. Epigenetics, p: 17(11), 1432. [Google Scholar]

- Tomasi, J. , et al., Towards precision medicine in generalized anxiety disorder: Review of genetics and pharmaco (epi) genetics. Journal of psychiatric research, p: 119.

- Cacabelos, R. , et al., Sirtuins in Alzheimer’s disease: SIRT2-related genophenotypes and implications for pharmacoepigenetics. International journal of molecular sciences, 2019. 20(5): p. 1249.

- Hack, L.M. , et al., Moving pharmacoepigenetics tools for depression toward clinical use. Journal of affective disorders, p: 249.

- Knothe, C. , et al., Pharmacoepigenetics of the role of DNA methylation in μ-opioid receptor expression in different human brain regions. Epigenomics, p: 8(12), 1583. [Google Scholar]

- Kacevska, M., M. Ivanov, and M. Ingelman-Sundberg, Epigenetic-dependent regulation of drug transport and metabolism: an update. Pharmacogenomics, p: 13(12), 1373. [Google Scholar]

- He, Y. , et al., The effects of micro RNA on the absorption, distribution, metabolism and excretion of drugs. British Journal of Pharmacology, p: 172(11), 2733. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, Y. , et al., Combined study of genetic and epigenetic biomarker risperidone treatment efficacy in Chinese Han schizophrenia patients. Translational psychiatry, 1170. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, X. , et al., Pedigree investigation, clinical characteristics, and prognosis analysis of haematological disease patients with germline TET2 mutation. BMC Cancer, p: 22(1).

- Buckingham, L. , et al., Somatic variants of potential clinical significance in the tumors of BRCA phenocopies. Hereditary Cancer in Clinical Practice,.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).