Submitted:

16 July 2025

Posted:

17 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

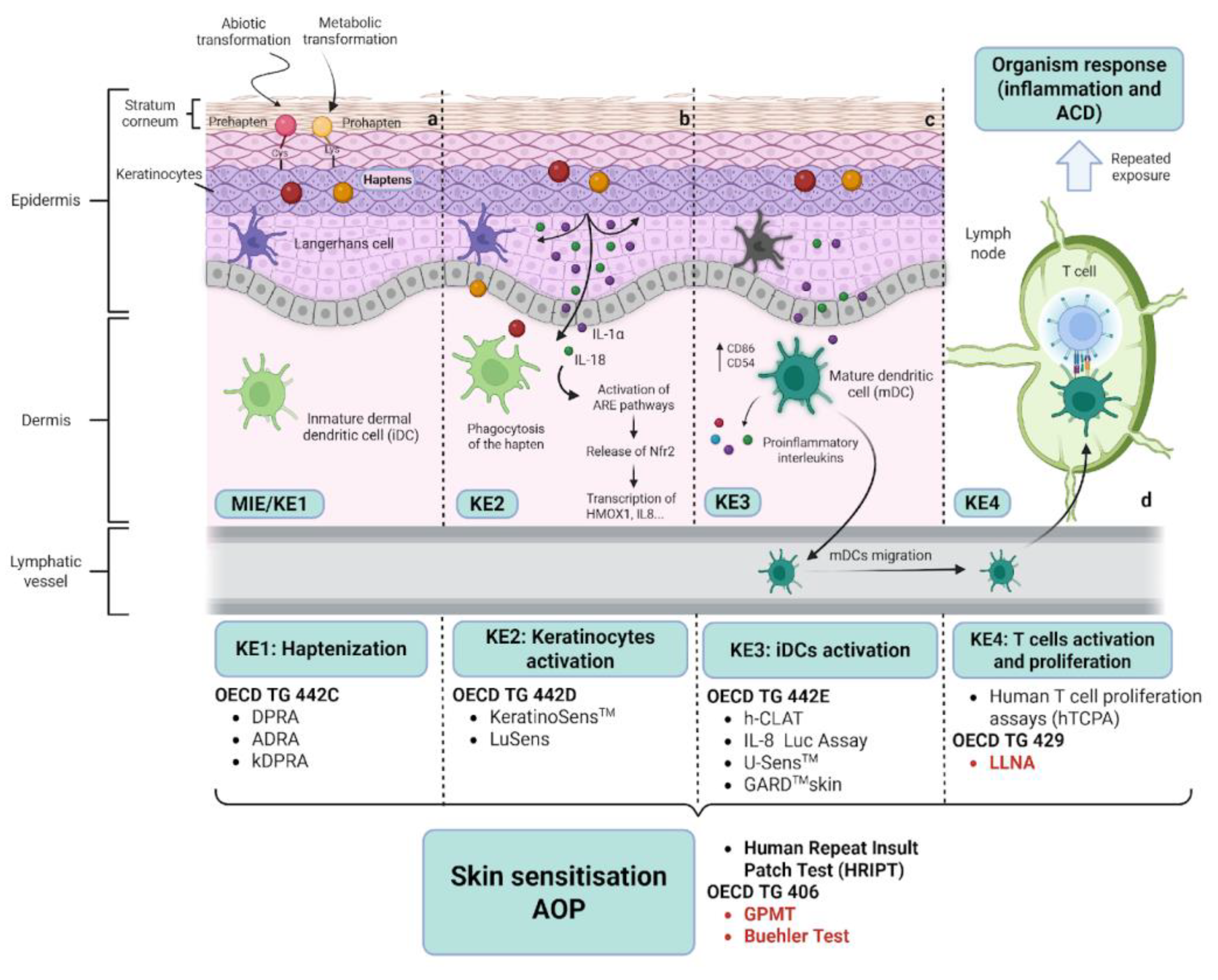

2. Skin Sensitisation, the Adverse Outcome Pathway and Alternative Test Methods

2.1. Skin Sensitisation

2.2. The Adverse Outcome Pathway and Alternative Methods

3. Regulatory Landscape and Advancements in Skin Sensitization Testing for Cosmetics

4. In Vitro Skin Models for Skin Sensitisation Testing

4.1. In Vitro Skin Models: Unique Tools for Dermatology Applications

4.2. RHE-Based Approaches to Evaluate Keratinocyte Response to Sensitisers (KE2)

4.2.1. Markers for the Keratinocyte Response

4.2.2. The RHE Methods for Keratinocyte Response

4.2.3. Performance of EpiSensA and SENS-IS

4.2.4. EpiSensA and SENS-IS in the NAM Battery for Skin Sensitisation

4.3. Immunocompetent Skin Models for KE3

5. Emerging Technologies to Improve Predictability in Skin Sensitisation

5.1. Skin-on-a-Chip (SoC)

5.2. Integration of Omics Approaches for Mechanistic and Predictive Insight

5.3. In Silico Methods

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| RHE | Reconstructed Human Epidermis |

| LLNA | Local Lymph Node Assay |

| ACD | Allergic Contact Dermatitis |

| GPMT | Guinea Pig Maximization Test |

| 3Rs | Replacement, Reduction, and Refinement |

| NAMs | New Approach Methods |

| OECD | Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development |

| AOP | Adverse Outcome Pathway |

| KEs | Key Events |

| 3D | Three-dimensional |

| APC | Antigen Presenting Cells |

| DCs | Dendritic Cells |

| LCs | Langerhans Cells |

| MIE | Molecular Initiating Event |

| ADRA | Amino acid Derivative Reactivity Assay |

| DPRA | Direct Peptide Reactivity Assay |

| kDPRA | kinetics Direct Peptide Reactivity Assay |

| IL | Interleukin |

| DAMPs | Damage-Associated Molecular Patterns |

| ROS | Reactive Oxygen Species |

| ARE | Antioxidant Response Element |

| Keap1 | Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1 |

| HMOX1 | Heme oxygenase1 |

| h-CLAT | Human Cell Line Activation Test |

| GARD | Genomic Allergen Rapid Detection |

| MHC | Major Histocompatibility Complex |

| CLP | Classification, Labelling and Packaging |

| REACH | Registration, Evaluation, Authorisation and Restriction of Chemicals |

| DAs | Defined Approaches |

| IATA | Integrated Approaches to Testing and Assessment |

| ITS | Integrated Testing Strategy |

| GHS | Globally Harmonized System |

| PoD | Point of Departure |

| QRA | Quantitative Risk Assessment |

| RHS | Reconstructed Human Skin |

| MTT | Methyl Thiazole Tetrazolium |

| DNCB | Dinitrochlorobenzene |

| SLS | Sodium Lauryl Sulphate |

| BZC | Benzalkonium Chloride |

| EE | Epidermal Equivalent |

| IVTI | In Vitro Toxicity Index |

| HSE | Human Skin Equivalent |

| SVM | Support Vector Machine |

| SoC | Skin-on-a-chip |

| HaCaT | Spontaneously Transformed Human Keratinocyte Cell Culture |

| TEER | Trans-epithelial electrical resistance |

| QSAR | Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship |

| SVM | Support Vector Machine |

| HPPT | Human Predictive Patch Test |

| SHAP | Shapley Additive Explanations |

Appendix A

| EE potency assay | RHE-IL--18 | SensCeeTox | Episens A | Sens-IS | |

| Test developer | VUMC (The Netherlands) | Università degli Studi di Mano (Italy) | CeeTox (USA) | Kao Corporation (Japan) | ImmunoSearch (France) |

| RHE models used | EpiCS® (CellSystems) SkinEthic™ (L'Oréal) |

In-house RHE (VUMC-EE), EpiCS® (CellSystems), EpiDerm™ (MatTek), SkinEthic™ (L’oreal) |

SkinEthic™ (L'Oréal); EpiDerm (MatTek) |

LabCyte EPI-MODEL 24 (J-Tec) |

EpiSkin™ (L’oreal) SkinEthic™ (L’oreal) |

| Pre-submission (TSAR ID)* |

to ECVAM in 2011 (TM2011-12) |

To EVCAM in 2012 (TM2012-05) |

to ECVAM in 2011 (TM2011-02) |

to JaCVAM in 2018 (TM2018-01) |

to ECVAM in 2011 (TM2011-11) |

| Formal validation | NO |

NO |

NO | Peer-review completed in 2023 |

Peer-review completed in 2024 |

| OEDC adoption | NO | NO | NO | Test Guideline 442D (june 2024) Test No 442D, 2024 | NO |

| Exposure time | 24 h | 24 h | 24 h | 6 h | 15 min (6h incubation) |

| Read out | 1. Cytotoxicity (MTT) |

1. IL-18 release by keratinocytes 2. Cytotoxicity (MTT) |

1. Glutathione (GSH) Depletion. 2. Gene expression of 7 genes controlled by the Nrf2/Keap1/ARE or AhR/ARNT/XRE signaling pathways: NADPH-quinone oxidoreductase 1 (NQO1) Aldoketoreductase 1C2 (AKR1C2) Interleukin 8 (IL-8) Cytochrome P450 1A1 (CYP1A1) Aldehyde dehydrogenase 3A1 (ALDH3A) Heme-oxygenase 1 (HMOX1) Glutamate cysteine ligase catalytic subunit C (GCLC). 3. Cytotoxicity (LDH) | 1. Gene Expression Analysis activating transcription factor 3 (ATF3); glutamate-cysteine ligase, modifier subunit (GCLM); DnaJ (Hsp40) homolog, subfamily B, member 4 (DNAJB4); and interleukin-8 (IL-8) 2.Cytotoxicity |

1. Gene Expression Analysis of 64 genes biomarkers in 3 groups: skin irritation (23), antioxidant pathways: ARE genes (17) SENS-IS genes (21) and housekeeping (3) Which vehicles are used in Episens A assay |

| Hazard prediction | NO | Several prediction models based on thresholds for IL-18 secretion and viability | Proprietary algorithm with data from GSH depletion, viability and marker gene expression | Positive if any marker gene expressed above individual thresholds values | Positive if expression of 7 or more marker genes in REDOX or SENS-IS panels above threshold value |

| Potency prediction Approach | Concentration for 50% reduction in viability (EC50) interpolated in a regression curve of reference substances | Concentration for 50% reduction in viability (EC50) or stimulation of IL-18 secretion (SI2) interpolated in a regression curve of reference substances. | Proprietary algorithm with data from GSH depletion, viability and gene expression (In Vitro Toxicity Index, IVTI) |

Cut-off value of the lowest positive concentration determines GHS potency categories | Lowest positive concentration determines potency according to LLNA categories |

| References | [90,91,172] | [93,94,95,173,174,175] | [96,176] | [99,100,101,114,115,125,177,178] | [105,110,113,116,117,118,122,123,127,128,179] |

| Immune cells incorporated | Differentiation conditions | Skin equivalent | Immune cell incorporation | Exposure to sensitisers | Read-out | Ref |

| CD34-derived Langerhans cells | CD34+ hematopoietic progenitor cells differentiated to LCs after 6 days in the presence of 200 ng/ml GM-CSF and 2.5 ng/ml TNF-a. | RHE-LCs | a) Co-seeding CD34-derived Langerhans cells with keratinocytes onto the Episkin™ support. b) CD34+ hematopoietic progenitor cells, not exposed to GM-CSF and TNF-a, co-seeded with keratinocytes and melanocytes onto dermal equivalents. |

No | Immunohistology staining, migration of CD1a+, Lag+ cells | [137] |

| CD34-derived Langerhans cells | Differentiated into DCs for 7 days in a medium with 2000 U/ml GM-CSF, 20 U/ml TNF-a, 20 ng/ml SCF. | RHE-LCs | CD34-derived LCs and keratinocytes were co-seeded onto the Episkin™ support. | 24 h topical application or solar simulated radiation. Cytokines: TNF-a and IL-1b. Sensitisers: dinitrofluorobenzene (DNFB), oxazolone, p-phenylenediamine (pPD), NiSO4, eugenol, benzocaine. Irritants: sodium lauryl sulphate, benzalkonium chloride, eugenol. |

Immunohistology staining: loss of dendricity. IL-1b, CD86 mRNA expression by RT-PCR |

[180] |

| Monocyte derived DCs (MoDCs) |

MoDCs were derived from peripheral blood CD14+ cells cultured for 6 days in the presence of, 250 U/ml IL-4 and 50 ng/ml GM-CSF. |

RHS-DCs | Layer of agarose–fibronectin gel containing immature MoDCs placed between a bottom fibroblast containing layer and a top keratinocyte layer | 24 h topical application sensitisers: dinitrochlorobenzene (DNCB). Irritant: sodium dodecyl sulphate (SDS). |

CD86 and HLA-DR expression by flow cytometry. IL-1α, IL-6 and IL-8 secretion by ELISA. |

[142] |

| Monocytes | CD14+ cells differentiated into dendritic cells when incorporated into this 3D skin model | RHS-DCs | For the RHS construct, keratinocytes and freshly isolated CD14+ cells were seeded on a fibrin-based dermal compartment populated by fibroblasts. | 24 h topical application f Sensitisers: Formaldehyde and Manganese (II) Chloride Tetrahydrate (MnCl2·4H2O). Irritant: sodium dodecyl sulphate (SDS) |

Immunohistology staining: Migration of CD1a+, Langerin+ cells. | [181] |

| DCs | Commercial normal human dendritic cells | RHS-DCs | RHS constructs were generated by preparing a collagen vitrigel membrane (VG-KDF-Skin) populated with fibroblasts, followed by normal human dendritic cells in collagen and then keratinocytes seeded on top | 1h topical application Sensitisers: Cobalt chloride (CoCl2), 2,4-dinitrofluorobenzene (DNFB), Formaldehyde (HCHO) and glutaraldehyde (GA), m-amino-phenol (m-AP), cinnamaldehyde (CA), DNCB, α-hexyl cinnamic aldehyde (HCA), isoeugenol (IE) . Non-sensitisers: dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), isopropanol (IP), lactic acid (LA), sodium dodecyl sulphate (SDS), Tween 80 |

IL-1α and IL-4 release by ELISA | [143] |

| MUTZ-3-LCs | cells were differentiated into MUTZ-3-LCs for for 7 days in the presence of 100 ng/ml GM-CSF, 10 ng/ml TGF-b and 2.5 ng/ml TNF-a. | RHS-LCs | For RHS generation keratinocytes and MUTZ-3-LCs were seeded on top of a dermal equivalent based on fibroblasts seeded onto a collagen matrix. | No | Immunohistology staining, Langerin+ cells. | [182] |

| MUTZ-3-LCs | MUTZ-3-LCs were derived in the presence of 100 ng/mL GM-CSF, 10 ng/mL, TGF-b, and 2.5 ng/mL TNF-a for 7 days. | RHS-LCs | full-thickness skin equivalent was made by co-culture MUTZ-3--LC with keratinocytes onto fibroblast-populated collagen gels. | 16 h topical application: sensitisers: NiSO4, resorcinol |

Immunohistology staining, migration of CD1a+, Langerin+ cells. IL-1b, CCR7 mRNA expression by RT-PCR. |

[145] |

| MUTZ-3-LCs | MUTZ-3 cells were differentiated into MUTZ-3-LCs for 7 days by treatment with 100 ng/ml GM-CSF, 10 ng/ml TGF-b1 and 2.5 ng/ml TNF-a |

RHS-LCs | SE containing MUTZ-3-LC was achieved by co-seeding CFSE labelled MUTZ-3-LC with Keratinocytes onto fibroblast-populated collagen gels. |

16 h Topical exposure Sensitisers: nickel sulphate, resorcinol, cinnamaldehyde Irritants: Triton X-100, SDS, Tween 80 |

Immunohistology staining and flow cytometry: migration of CD1a+, Langerin+ cells. CD68 mRNA expression by RT-PCR |

[146] |

| MUTZ-3-LCs | Not indicated | Co-culture MUTZ-3-LCs with RHEs | Dermal equivalent with a lattice of collagen and fibroblasts overlaid by a stratified epidermis. RealSkin was used either as a stand-alone assay or co-cultured with MUTZ-3-LCs |

48 h topical exposure: Sensitisers: isoeugenol, and a stron p-phenylenediamine (PPD). Irritant: salicylic acid |

Release of 27 cytokines panel using multiplex bead-based immunoassay. Transwell chemotactic assay to CCL19. |

[183] |

| MUTZ-3-LCs and MoLCsMUTZ-3-LCs | MUTZ-3 cells were differentiated into MUTZ-3-LCs for 10 days by treatment with 10 ng/ml TGF-b1, 100 ng/ml GM-CSF, 2.5 ng/ml TNF-a. MoLCs were obtained after 7 days of monocyte cultivation with 100 ng/mlGM-CSF, 20 ng/ml interleukin IL-4 and 20 ng/ml TGF-b1 MUTZ-3 cells were differentiated into MUTZ-3-LCs for 7 days by treatment with 100 ng/ml GM-CSF, 10 ng/ml TGF-b1 and 2.5 ng/ml TNF-a |

RHS-LCs | Full-thickness skin equivalents prepared by seeding normal human keratinocytes and MUTZ-LCs or MoLCs, respectively, onto the dermal compartment populated with fibroblast on collagen I gel. | 24h topical application: Sensitisers: 2,4-dinitrochlorobenzene (DNCB), isoeugenol. Irritant: sodium dodecyl sulphate (SDS)16 h Topical exposure: Sensitisers: cinnamaldehyde, resorcinol or nickel (II) sulphate hexahydrate (NiSO4) |

Immunohistology staining and flow cytometry: migration CD1a+, Langerin+ cells. IL-6-, IL-8- and IL-18 releases quantified by ELISA ATF3, CD83, CXCR4, IL-1b, PD-L1 mRNA expression by RT-PCR |

[184] |

| MUTZ-3-LCsMUTZ-3-LCs and MoLCs | MUTZ-3 cells were differentiated into MUTZ-3-LCs for 7 days by treatment with 100 ng/ml GM-CSF , 10 ng/ml TGF-b1 and 2.5 ng/ml TNF-a. |

RHS-LCs RHS-LCs/ and MoLCs | RHS-LCs were constructed by preparing a fibroblast populated collagen I hydrogel and coculture Keratinocytes and CFSE-labelled MUTZ-LCs on top of the hydrogel. | 24h topical application: Sensitisers: TiO2, CaO3Ti, C12H28O4Ti, TiALH, nickel sulphate. |

Immunohistology staining CD1a+, Langerin+ cells. CXCL12 vs CCL5-dependent migration of MUTZ-3—LCs. Increase in CD83/CD86 expression by flow cytometry. CXCL8 release quantified by ELISA. IL-1b, CCR7, IL-10 mRNA expression by RT-PCR |

[185] |

| THP-1 MUTZ-3-LCs | THP-1 in RPMI 10% FBS. (Non-differentiated) |

Co-culture of THP-1 with RHE | THP-1 cells were seeded in the basolateral compartment underneath the RHE models (OS-REp, SkinEthic™ RHE).. |

24h topical application. Sensitisers: eugenol, coumarin Irritant: Lactic acid. |

Increase in CD86, CD54, CD40 and HLA-DR expression by flow cytometry | [186] |

| THP1-DCsTHP-1 | THP1 cells were differentiated to DCs for 5 days by treatment with 1500 IU/mL rhGM-CSF and 1500 IU/ml rhIL-4.THP-1 in RPMI 10% FBS. |

RHS-DCs | RHS-DCs were constructed by seeding Keratinocytes with THP-1-derived iDCs onto dermis models based on a solid and porous collagen matrix and primary human foreskin fibroblasts. | 24h topical application: Sensitisers: 1-chloro-2,4-dinitrobenzene (DNCB), nickel sulphate (NiSO4). |

Increase in CD86, CD54, expression by flow cytometry IkBa degradation and phosphorylation of p38 MAPK by western blot. IL-6, IL-8, IL-1b, TNFa and protein secretion by ELISA mRNA expression by RT-PCR |

[187] |

| THP1-DCs and MUTZ-3-LCs |

THP-1 cells were differentiated to DCs for 5 days by treatment with 1500 IU/mL rhGM-CSF and 1500 IU/ml rhIL-4. MUTZ-3 cells were differentiated to LCs for 9 days by treatment with 1000 U/ml rhGM-CSF, 400 U/mL TGF-b and 100 U/ml TNF-a. |

RHS-DCs/LCs | RHS-DCs were constructed by seeding Keratinocytes with MUTZ-3_LCs and THP-1-DCs onto the dermis models. After that freshly detached keratinocytes were seeded on top of the MUTZ-3-LCs +THP1-DCs models. RHS-DCs were constructed by seeding Keratinocytes with THP-1-DCs onto dermis models based on a solid and porous collagen matrix and primary human foreskin fibroblasts. | 6-24h topical application Sensitisers: DNCB, NiSO4 |

Immunohistology staining, migration CD1a+ cells. IkBa degradation, and phosphorylation of p38 MAPK by western blot CD86, CD83, CD54, CXCR4, CCR7, IL-6, IL-8, TNFa, IL-1a IL-1b and IL-12p40 mRNA expression by qPCR.Increase in CD86, CD54, expression by flow cytometry IkBa degradation and phosphorylation of p38 MAPK by western blot. mRNA expression by RT-PCR IL-6, IL-8, IL-1b, TNFa and protein secretion by ELISA |

[188] |

References

- Corsini, E.; Engin, A.B.; Neagu, M.; Galbiati, V.; Nikitovic, D.; Tzanakakis, G.; Tsatsakis, A.M. Chemical-Induced Contact Allergy: From Mechanistic Understanding to Risk Prevention. Arch Toxicol 2018, 92, 3031–3050. [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, D.H.; Igyártó, B.Z.; Gaspari, A.A. Early Events in the Induction of Allergic Contact Dermatitis. Nature reviews. Immunology 2012, 12, 114. [CrossRef]

- Rustemeyer, T. Immunological Mechanisms in Allergic Contact Dermatitis. Curr Treat Options Allergy 2022, 9, 67–75. [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, H.; Y, Y.; E, P. Role of Innate Immunity in Allergic Contact Dermatitis: An Update. International journal of molecular sciences 2023, 24. [CrossRef]

- Alinaghi, F.; Bennike, N.H.; Egeberg, A.; Thyssen, J.P.; Johansen, J.D. Prevalence of Contact Allergy in the General Population: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Contact Dermatitis 2019, 80, 77–85. [CrossRef]

- Park, M.E.; Zippin, J.H. Allergic Contact Dermatitis to Cosmetics. 2014. [CrossRef]

- Diepgen, T.L.; Ofenloch, R.F.; Bruze, M.; Bertuccio, P.; Cazzaniga, S.; Coenraads, P.-J.; Elsner, P.; Goncalo, M.; Svensson, Å.; Naldi, L. Prevalence of Contact Allergy in the General Population in Different European Regions. Br J Dermatol 2016, 174, 319–329. [CrossRef]

- Alani, J.I.; Davis, M.D.P.; Yiannias, J.A. Allergy to Cosmetics: A Literature Review. Dermatitis 2013, 24, 283–290. [CrossRef]

- Uter, W.; Werfel, T.; Lepoittevin, J.-P.; White, I.R. Contact Allergy—Emerging Allergens and Public Health Impact. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2020, 17, 2404. [CrossRef]

- Martin, S.F. The Role of the Innate Immune System in Allergic Contact Dermatitis*. Allergol Select 2017, 1, 39–43. [CrossRef]

- Uter, W.; Werfel, T.; White, I.R.; Johansen, J.D. Contact Allergy: A Review of Current Problems from a Clinical Perspective. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2018, 15, 1108. [CrossRef]

- de Groot, A.C. Contact Allergy to Cosmetics: Causative Ingredients. Contact Dermatitis 1987, 17, 26–34. [CrossRef]

- Meigs, L.; Smirnova, L.; Rovida, C.; Leist, M.; Hartung, T. Animal Testing and Its Alternatives - the Most Important Omics Is Economics. ALTEX 2018, 35, 275–305. [CrossRef]

- Circabc Available online: https://circabc.europa.eu/ui/group/8ee3c69a-bccb-4f22-89ca-277e35de7c63/library/051e5787-7746-46cf-8a0d-310f84fd1900/details (accessed on 8 July 2025).

- Basketter, D.; Ball, N.; Cagen, S.; Carrillo, J.-C.; Certa, H.; Eigler, D.; Garcia, C.; Esch, H.; Graham, C.; Haux, C.; et al. Application of a Weight of Evidence Approach to Assessing Discordant Sensitisation Datasets: Implications for REACH. Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology 2009, 55, 90–96. [CrossRef]

- Aeby, P.; Ashikaga, T.; Bessou-Touya, S.; Schepky, A.; Gerberick, F.; Kern, P.; Marrec-Fairley, M.; Maxwell, G.; Ovigne, J.-M.; Sakaguchi, H.; et al. Identifying and Characterizing Chemical Skin Sensitizers without Animal Testing: Colipa’s Research and Method Development Program. Toxicol In Vitro 2010, 24, 1465–1473. [CrossRef]

- Worth, A.P.; Balls, M. The Principles of Validation and the ECVAM Validation Process. Altern Lab Anim 2004, 32 Suppl 1B, 623–629. [CrossRef]

- Maxwell, G.; MacKay, C.; Cubberley, R.; Davies, M.; Gellatly, N.; Glavin, S.; Gouin, T.; Jacquoilleot, S.; Moore, C.; Pendlington, R.; et al. Applying the Skin Sensitisation Adverse Outcome Pathway (AOP) to Quantitative Risk Assessment. Toxicol In Vitro 2014, 28, 8–12. [CrossRef]

- OECD The Adverse Outcome Pathway for Skin Sensitisation Initiated by Covalent Binding to Proteins; OECD Series on Testing and Assessment; OECD: Paris, France, 2014;

- OECD Test No. 442D: In Vitro Skin Sensitisation: ARE-Nrf2 Luciferase Test Method; OECD Publishing: Paris, 2024;

- Risueño, I.; Valencia, L.; Jorcano, J.L.; Velasco, D. Skin-on-a-Chip Models: General Overview and Future Perspectives. APL Bioengineering 2021, 5, 030901. [CrossRef]

- Footner, E.; Firipis, K.; Liu, E.; Baker, C.; Foley, P.; Kapsa, R.M.I.; Pirogova, E.; O’Connell, C.; Quigley, A. Layer-by-Layer Analysis of In Vitro Skin Models. ACS Biomater Sci Eng 2023, 9, 5933–5952. [CrossRef]

- Kashem, S.W.; Haniffa, M.; Kaplan, D.H. Antigen-Presenting Cells in the Skin. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2017, 35, 469–499. [CrossRef]

- Goodwin, B.F.; Roberts, D.W. Structure-Activity Relationships in Allergic Contact Dermatitis. Food Chem Toxicol 1986, 24, 795–798. [CrossRef]

- Lepoittevin, J.-P. Metabolism versus Chemical Transformation or Pro- versus Prehaptens? Contact Dermatitis 2006, 54, 73–74. [CrossRef]

- Aptula, A.O.; Roberts, D.W.; Pease, C.K. Haptens, Prohaptens and Prehaptens, or Electrophiles and Proelectrophiles. Contact Dermatitis 2007, 56, 54–56. [CrossRef]

- Ankley, G.T.; Bennett, R.S.; Erickson, R.J.; Hoff, D.J.; Hornung, M.W.; Johnson, R.D.; Mount, D.R.; Nichols, J.W.; Russom, C.L.; Schmieder, P.K.; et al. Adverse Outcome Pathways: A Conceptual Framework to Support Ecotoxicology Research and Risk Assessment. Environ Toxicol Chem 2010, 29, 730–741. [CrossRef]

- OECD Test Guideline No. 442C In Chemico Skin Sensitisation_KE1 ASSESSMENT; OECD Guidelines for the Testing of Chemicals, Section 4; OECD: Paris, France, 2023;

- Weber, F.C.; Esser, P.R.; Müller, T.; Ganesan, J.; Pellegatti, P.; Simon, M.M.; Zeiser, R.; Idzko, M.; Jakob, T.; Martin, S.F. Lack of the Purinergic Receptor P2X7 Results in Resistance to Contact Hypersensitivity. J Exp Med 2010, 207, 2609–2619. [CrossRef]

- OECD Test Guideline No. 442E In Vitro Skin Sensitisation_KE3 ASSESSMENT; OECD Guidelines for the Testing of Chemicals, Section 4; OECD: Paris, France, 2023;

- OECD Test No. 429: Skin Sensitisation: Local Lymph Node Assay; OECD Guidelines for the Testing of Chemicals, Section 4; París, 2010;

- de Groot, A.C. Contact Allergy to Cosmetics: Causative Ingredients. Contact Dermatitis 1987, 17, 26–34. [CrossRef]

- Daniel, A.B.; Strickland, J.; Allen, D.; Casati, S.; Zuang, V.; Barroso, J.; Whelan, M.; Régimbald-Krnel, M.J.; Kojima, H.; Nishikawa, A.; et al. International Regulatory Requirements for Skin Sensitization Testing. Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology 2018, 95, 52–65. [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, M.; Matos, A.; Couras, A.; Marto, J.; Ribeiro, H. Overview of Cosmetic Regulatory Frameworks around the World. Cosmetics 2022, 9, 72. [CrossRef]

- Regulation (EC) No 1272/2008 on Classification, Labelling and Packaging of Substances and Mixtures (CLP Regulation); 2008; pp. 1–1355;.

- Commission Regulation (EU) 2017/706 of 19 April 2017 Amending Annex VII to Regulation (EC) No 1907/2006 of the European Parliament and of the Council on the Registration, Evaluation, Authorisation and Restriction of Chemicals (REACH) as Regards Skin Sensitisation and Repealing Commission Regulation (EU) 2016/1688 (Text with EEA Relevance. ); 2017; Vol. 104;.

- Council Directive 76/768/EEC of 27 July 1976 on the Approximation of the Laws of the Member States Relating to Cosmetic Products; 1976; Vol. 262;.

- Regulation (EC) No 1907/2006 Concerning the Registration, Evaluation, Authorisation and Restriction of Chemicals (REACH); 2006; pp. 1–849;.

- Commission Regulation (EU) 2023/… of 26 July 2023 Amending Regulation (EC) No 1223/2009 of the European Parliament and of the Council as Regards Labelling of Fragrance Allergens in Cosmetic Products; 2023;

- Knight, J.; Rovida, C.; Kreiling, R.; Zhu, C.; Knudsen, M.; Hartung, T. Continuing Animal Tests on Cosmetic Ingredients for REACH in the EU. ALTEX 2021, 38, 653–668. [CrossRef]

- OECD Test No. 406: Skin Sensitisation; Skin Sensitisation, OECD Guidelines for the Testing of Chemicals; París, 1992;

- Gerberick, G.F.; Ryan, C.A.; Dearman, R.J.; Kimber, I. Local Lymph Node Assay (LLNA) for Detection of Sensitization Capacity of Chemicals. Methods 2007, 41, 54–60. [CrossRef]

- Chayawan; Selvestrel, G.; Baderna, D.; Toma, C.; Caballero Alfonso, A.Y.; Gamba, A.; Benfenati, E. Skin Sensitization Quantitative QSAR Models Based on Mechanistic Structural Alerts. Toxicology 2022, 468, 153111. [CrossRef]

- OECD Test Guideline No. 497: Defined Approaches on Skin Sensitisation; OECD Guidelines for the Testing of Chemicals, Section 4; OECD: Paris, France, 2023;

- Kleinstreuer, N.C.; Hoffmann, S.; Alépée, N.; Allen, D.; Ashikaga, T.; Casey, W.; Clouet, E.; Cluzel, M.; Desprez, B.; Gellatly, N.; et al. Non-Animal Methods to Predict Skin Sensitization (II): An Assessment of Defined Approaches *. Crit Rev Toxicol 2018, 48, 359–374. [CrossRef]

- Assaf Vandecasteele, H.; Gautier, F.; Tourneix, F.; Vliet, E. van; Bury, D.; Alépée, N. Next Generation Risk Assessment for Skin Sensitisation: A Case Study with Propyl Paraben. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol 2021, 123, 104936. [CrossRef]

- OECD Guidance Document on the Reporting of Defined Approaches to Be Used Within Integrated Approaches to Testing and Assessment; OECD Series on Testing and Assessment, No. 256; OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development): Paris, 2016;

- Takenouchi, O.; Fukui, S.; Okamoto, K.; Kurotani, S.; Imai, N.; Fujishiro, M.; Kyotani, D.; Kato, Y.; Kasahara, T.; Fujita, M.; et al. Test Battery with the Human Cell Line Activation Test, Direct Peptide Reactivity Assay and DEREK Based on a 139 Chemical Data Set for Predicting Skin Sensitizing Potential and Potency of Chemicals. J Appl Toxicol 2015, 35, 1318–1332. [CrossRef]

- Natsch, A.; Haupt, T.; Wareing, B.; Landsiedel, R.; Kolle, S.N. Predictivity of the Kinetic Direct Peptide Reactivity Assay (kDPRA) for Sensitizer Potency Assessment and GHS Subclassification. ALTEX - Alternatives to animal experimentation 2020, 37, 652–664. [CrossRef]

- Api, A.M.; Basketter, D.A.; Cadby, P.A.; Cano, M.-F.; Ellis, G.; Gerberick, G.F.; Griem, P.; McNamee, P.M.; Ryan, C.A.; Safford, R. Dermal Sensitization Quantitative Risk Assessment (QRA) for Fragrance Ingredients. Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology 2008, 52, 3–23. [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, J.; Gilmour, N.; Baltazar, M.T.; Reynolds, G.; Windebank, S.; Maxwell, G. Decision Making in next Generation Risk Assessment for Skin Allergy: Using Historical Clinical Experience to Benchmark Risk. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol 2022, 134, 105219. [CrossRef]

- Gilmour, N.; Kern, P.S.; Alépée, N.; Boislève, F.; Bury, D.; Clouet, E.; Hirota, M.; Hoffmann, S.; Kühnl, J.; Lalko, J.F.; et al. Development of a next Generation Risk Assessment Framework for the Evaluation of Skin Sensitisation of Cosmetic Ingredients. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol 2020, 116, 104721. [CrossRef]

- Natsch, A. Integrated Skin Sensitization Assessment Based on OECD Methods (III): Adding Human Data to the Assessment. ALTEX 2023, 571–583. [CrossRef]

- Zeller, K.S.; Forreryd, A.; Lindberg, T.; Gradin, R.; Chawade, A.; Lindstedt, M. The GARD Platform for Potency Assessment of Skin Sensitizing Chemicals. ALTEX - Alternatives to animal experimentation 2017, 34, 539–559. [CrossRef]

- Gradin, R.; Forreryd, A.; Mattson, U.; Jerre, A.; Johansson, H. Quantitative Assessment of Sensitizing Potency Using a Dose-Response Adaptation of GARDskin. Sci Rep 2021, 11, 18904. [CrossRef]

- Strickland, J.; Zang, Q.; Paris, M.; Lehmann, D.M.; Allen, D.; Choksi, N.; Matheson, J.; Jacobs, A.; Casey, W.; Kleinstreuer, N. Multivariate Models for Prediction of Human Skin Sensitization Hazard. Journal of Applied Toxicology 2017, 37, 347–360. [CrossRef]

- Giménez-Arnau, E. Chemical Compounds Responsible for Skin Allergy to Complex Mixtures: How to Identify Them? Cosmetics 2019, 6, 71. [CrossRef]

- Brohem, C.A.; da Silva Cardeal, L.B.; Tiago, M.; Soengas, M.S.; de Moraes Barros, S.B.; Maria-Engler, S.S. Artificial Skin in Perspective: Concepts and Applications. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res 2011, 24, 35–50. [CrossRef]

- Ponec, M.; Boelsma, E.; Weerheim, A.; Mulder, A.; Bouwstra, J.; Mommaas, M. Lipid and Ultrastructural Characterization of Reconstructed Skin Models. Int J Pharm 2000, 203, 211–225. [CrossRef]

- Ponec, M.; Boelsma, E.; Gibbs, S.; Mommaas, M. Characterization of Reconstructed Skin Models. Skin Pharmacology and Applied Skin Physiology 2004, 15, 4–17. [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Zhang, L.; Hao, H.; Yan, M.; Zhu, Z. Applications of Engineered Skin Tissue for Cosmetic Component and Toxicology Detection. Cell Transplant 2024, 33, 9636897241235464. [CrossRef]

- Roguet, R.; Régnier, M.; Cohen, C.; Dossou, K.G.; Rougier, A. The Use of in Vitro Reconstituted Human Skin in Dermotoxicity Testing. Toxicol In Vitro 1994, 8, 635–639. [CrossRef]

- Gay, R.; Swiderek, M.; Nelson, D.; Ernesti, A. The Living Skin Equivalent as a Model in Vitro for Ranking the Toxic Potential of Dermal Irritants. Toxicology in Vitro 1992, 6, 303–315. [CrossRef]

- Ponec, M.; Kempenaar, J. Use of Human Skin Recombinants as an in Vitro Model for Testing the Irritation Potential of Cutaneous Irritants. Skin Pharmacol 1995, 8, 49–59. [CrossRef]

- Bernard, F.X.; Barrault, C.; Deguercy, A.; De Wever, B.; Rosdy, M. Development of a Highly Sensitive in Vitro Phototoxicity Assay Using the SkinEthic Reconstructed Human Epidermis. Cell Biol Toxicol 2000, 16, 391–400. [CrossRef]

- Roguet, R.; Cohen, C.; Robles, C.; Courtellemont, P.; Tolle, M.; Guillot, J.P.; Pouradier Duteil, X. An Interlaboratory Study of the Reproducibility and Relevance of Episkin, a Reconstructed Human Epidermis, in the Assessment of Cosmetics Irritancy. Toxicol In Vitro 1998, 12, 295–304. [CrossRef]

- de Brugerolle de Fraissinette, null; Picarles, V.; Chibout, S.; Kolopp, M.; Medina, J.; Burtin, P.; Ebelin, M.E.; Osborne, S.; Mayer, F.K.; Spake, A.; et al. Predictivity of an in Vitro Model for Acute and Chronic Skin Irritation (SkinEthic) Applied to the Testing of Topical Vehicles. Cell Biol Toxicol 1999, 15, 121–135. [CrossRef]

- Monteiro-Riviere, N.A.; Inman, A.O.; Snider, T.H.; Blank, J.A.; Hobson, D.W. Comparison of an in Vitro Skin Model to Normal Human Skin for Dermatological Research. Microsc Res Tech 1997, 37, 172–179. [CrossRef]

- Netzlaff, F.; Lehr, C.-M.; Wertz, P.W.; Schaefer, U.F. The Human Epidermis Models EpiSkin, SkinEthic and EpiDerm: An Evaluation of Morphology and Their Suitability for Testing Phototoxicity, Irritancy, Corrosivity, and Substance Transport. Eur J Pharm Biopharm 2005, 60, 167–178. [CrossRef]

- Bouwstra, J.A.; Helder, R.W.J.; El Ghalbzouri, A. Human Skin Equivalents: Impaired Barrier Function in Relation to the Lipid and Protein Properties of the Stratum Corneum. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews 2021, 175, 113802. [CrossRef]

- OECD Test Guideline No. 439: In Vitro Skin Irritation: Reconstructed Human Epidermis Test Methods; OECD Guidelines for the Testing of Chemicals; OECD: Paris, France, 2021;

- OECD Test No. 431: In Vitro Skin Corrosion: Reconstructed Human Epidermis (RHE) Test Method; OECD Guidelines for the Testing of Chemicals, Section 4; OECD Publishing: Paris, 2019;

- Caloni, F.; De Angelis, I.; Hartung, T. Replacement of Animal Testing by Integrated Approaches to Testing and Assessment (IATA): A Call for in Vivitrosi. Arch Toxicol 2022, 96, 1935–1950. [CrossRef]

- OECD Test No. 498: In Vitro Phototoxicity - Reconstructed Human Epidermis Phototoxicity Test Method; París, 2023;

- Enk, A.H.; Katz, S.I. Early Molecular Events in the Induction Phase of Contact Sensitivity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1992, 89, 1398–1402. [CrossRef]

- Müller, G.; Knop, J.; Enk, A.H. Is Cytokine Expression Responsible for Differences between Allergens and Irritants? American Journal of Contact Dermatitis 1996, 7, 177–184. [CrossRef]

- Corsini, E.; Limiroli, E.; Marinovich, M.; Cohen, C.; Roguet, R.; Galli, C.L. Selective Induction of Interleukin-12 in Reconstructed Human Epidermis by Chemical Allergens. Altern Lab Anim 1999, 27, 261–269. [CrossRef]

- Coquette, A.; Berna, N.; Vandenbosch, A.; Rosdy, M.; Poumay, Y. Differential Expression and Release of Cytokines by an in Vitro Reconstructed Human Epidermis Following Exposure to Skin Irritant and Sensitizing Chemicals. Toxicol In Vitro 1999, 13, 867–877. [CrossRef]

- Gerberick, G.F.; Sikorski, E.E. In Vitro and in Vivo Testing Techniques for Allergic Contact Dermatitis. Am J Contact Dermat 1998, 9, 111–118.

- Ryan, C.A.; Hulette, B.C.; Gerberick, G.F. Approaches for the Development of Cell-Based in Vitro Methods for Contact Sensitization. Toxicol In Vitro 2001, 15, 43–55. [CrossRef]

- Dinkova-Kostova, A.T.; Kostov, R.V.; Canning, P. Keap1, the Cysteine-Based Mammalian Intracellular Sensor for Electrophiles and Oxidants. Arch Biochem Biophys 2017, 617, 84–93. [CrossRef]

- Natsch, A.; Emter, R. Skin Sensitizers Induce Antioxidant Response Element Dependent Genes: Application to the in Vitro Testing of the Sensitization Potential of Chemicals. Toxicol Sci 2008, 102, 110–119. [CrossRef]

- Emter, R.; Ellis, G.; Natsch, A. Performance of a Novel Keratinocyte-Based Reporter Cell Line to Screen Skin Sensitizers in Vitro. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 2010, 245, 281–290. [CrossRef]

- Ryan, C.A.; Gildea, L.A.; Hulette, B.C.; Dearman, R.J.; Kimber, I.; Gerberick, G.F. Gene Expression Changes in Peripheral Blood-Derived Dendritic Cells Following Exposure to a Contact Allergen. Toxicology Letters 2004, 150, 301–316. [CrossRef]

- Gildea, L.A.; Ryan, C.A.; Foertsch, L.M.; Kennedy, J.M.; Dearman, R.J.; Kimber, I.; Gerberick, G.F. Identification of Gene Expression Changes Induced by Chemical Allergens in Dendritic Cells: Opportunities for Skin Sensitization Testing. Journal of Investigative Dermatology 2006, 126, 1813–1822. [CrossRef]

- Van Der Veen, J.W.; Soeteman-Hernández, L.G.; Ezendam, J.; Stierum, R.; Kuper, F.C.; Van Loveren, H. Anchoring Molecular Mechanisms to the Adverse Outcome Pathway for Skin Sensitization: Analysis of Existing Data. Critical Reviews in Toxicology 2014, 44, 590–599. [CrossRef]

- Vandebriel, R.J.; Pennings, J.L.A.; Baken, K.A.; Pronk, T.E.; Boorsma, A.; Gottschalk, R.; Van Loveren, H. Keratinocyte Gene Expression Profiles Discriminate Sensitizing and Irritating Compounds. Toxicol Sci 2010, 117, 81–89. [CrossRef]

- Antonopoulos, C.; Cumberbatch, M.; Mee, J.B.; Dearman, R.J.; Wei, X.-Q.; Liew, F.Y.; Kimber, I.; Groves, R.W. IL-18 Is a Key Proximal Mediator of Contact Hypersensitivity and Allergen-Induced Langerhans Cell Migration in Murine Epidermis. J Leukoc Biol 2008, 83, 361–367. [CrossRef]

- Roggen, E.L. Application of the Acquired Knowledge and Implementation of the Sens-It-Iv Toolbox for Identification and Classification of Skin and Respiratory Sensitizers. Toxicology in Vitro 2013, 27, 1122–1126. [CrossRef]

- Teunis, M.A.T.; Spiekstra, S.W.; Smits, M.; Adriaens, E.; Eltze, T.; Galbiati, V.; Krul, C.; Landsiedel, R.; Pieters, R.; Reinders, J.; et al. International Ring Trial of the Epidermal Equivalent Sensitizer Potency Assay: Reproducibility and Predictive-Capacity. ALTEX 2014, 31, 251–268. [CrossRef]

- dos Santos, G.G.; Spiekstra, S.W.; Sampat-Sardjoepersad, S.C.; Reinders, J.; Scheper, R.J.; Gibbs, S. A Potential in Vitro Epidermal Equivalent Assay to Determine Sensitizer Potency. Toxicol In Vitro 2011, 25, 347–357. [CrossRef]

- Corsini, E.; Galbiati, V.; Mitjans, M.; Galli, C.L.; Marinovich, M. NCTC 2544 and IL-18 Production: A Tool for the Identification of Contact Allergens. Toxicology in Vitro 2013, 27, 1127–1134. [CrossRef]

- Gibbs, S.; Corsini, E.; Spiekstra, S.W.; Galbiati, V.; Fuchs, H.W.; DeGeorge, G.; Troese, M.; Hayden, P.; Deng, W.; Roggen, E. An Epidermal Equivalent Assay for Identification and Ranking Potency of Contact Sensitizers. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology 2013, 272, 529–541. [CrossRef]

- Galbiati, V.; Papale, A.; Marinovich, M.; Gibbs, S.; Roggen, E.; Corsini, E. Development of an in Vitro Method to Estimate the Sensitization Induction Level of Contact Allergens. Toxicol Lett 2017, 271, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Andres, E. A New Prediction Model for Distinguishing Skin Sensitisers Based on IL-18 Release from Reconstructed Epidermis: Enhancing the Assessment of a Key Event in the Skin Sensitisation Adverse Outcome Pathway. JDC 2020, 4, 123–137. [CrossRef]

- McKim Jr, J.M.; Keller III, D.J.; Gorski, J.R. An in Vitro Method for Detecting Chemical Sensitization Using Human Reconstructed Skin Models and Its Applicability to Cosmetic, Pharmaceutical, and Medical Device Safety Testing. Cutaneous and Ocular Toxicology 2012, 31, 292–305. [CrossRef]

- McKim, J.M.; Keller, D.J.; Gorski, J.R. A New in Vitro Method for Identifying Chemical Sensitizers Combining Peptide Binding with ARE/EpRE-Mediated Gene Expression in Human Skin Cells. Cutan Ocul Toxicol 2010, 29, 171–192. [CrossRef]

- Clippinger, A.J.; Keller, D.; McKim, J.M.; Witters, H. Inter-Laboratory Validation of an In Vitro Method to Classify Skin Sensitizers. In Proceedings of the PETA Science consortium; 2014.

- Saito, K.; Nukada, Y.; Takenouchi, O.; Miyazawa, M.; Sakaguchi, H.; Nishiyama, N. Development of a New in Vitro Skin Sensitization Assay (Epidermal Sensitization Assay; EpiSensA) Using Reconstructed Human Epidermis. Toxicology in Vitro 2013, 27, 2213–2224. [CrossRef]

- Saito, K.; Takenouchi, O.; Nukada, Y.; Miyazawa, M.; Sakaguchi, H. An in Vitro Skin Sensitization Assay Termed EpiSensA for Broad Sets of Chemicals Including Lipophilic Chemicals and Pre/pro-Haptens. Toxicology in Vitro 2017, 40, 11–25. [CrossRef]

- Mizumachi, H.; Suzuki, S.; Sakuma, M.; Natsui, M.; Imai, N.; Miyazawa, M. Reconstructed Human Epidermis-Based Testing Strategy of Skin Sensitization Potential and Potency Classification Using Epidermal Sensitization Assay and in Silico Data. Journal of Applied Toxicology 2024, 44, 415–427. [CrossRef]

- Epidermal Sensitisation Assay (EpiSensA) Available online: https://tsar.jrc.ec.europa.eu/test-method/tm2018-01-0.

- JaCVAM (Japanese Center for the Validation of Alternative Methods) Epidermal Sensitisation Assay (EpiSensA) Validation Study Report; National Institute of Health Sciences: Japan, 2023;

- OECD Epidermal Sensitisation Assay (EpiSensA) Peer Review Report; Series on Testing and Assesment; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2023;

- Cottrez, F.; Boitel, E.; Auriault, C.; Aeby, P.; Groux, H. Genes Specifically Modulated in Sensitized Skins Allow the Detection of Sensitizers in a Reconstructed Human Skin Model. Development of the SENS-IS Assay. Toxicology in Vitro 2015, 29, 787–802. [CrossRef]

- OECD Draft Validation Report of the SENS-IS Assay; Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development: Paris, France, 2024;

- SENS-IS | EURL ECVAM - TSAR Available online: https://tsar.jrc.ec.europa.eu/test-method/tm2011-11 (accessed on 9 July 2025).

- OECD Peer Review Report of the Epidermal Sensitisation Assay (EpiSensA); Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2023;

- OECD Draft Test Guideline: Sens-IS Assay; 2024;

- Hoffmann, S.; Kleinstreuer, N.; Alépée, N.; Allen, D.; Api, A.M.; Ashikaga, T.; Clouet, E.; Cluzel, M.; Desprez, B.; Gellatly, N.; et al. Non-Animal Methods to Predict Skin Sensitization (I): The Cosmetics Europe Database<sup/>. Crit Rev Toxicol 2018, 48, 344–358. [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, S.; Alépée, N.; Gilmour, N.; Kern, P.S.; van Vliet, E.; Boislève, F.; Bury, D.; Cloudet, E.; Klaric, M.; Kühnl, J.; et al. Expansion of the Cosmetics Europe Skin Sensitisation Database with New Substances and PPRA Data. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol 2022, 131, 105169. [CrossRef]

- Desprez, B.; Dent, M.; Keller, D.; Klaric, M.; Ouédraogo, G.; Cubberley, R.; Duplan, H.; Eilstein, J.; Ellison, C.; Grégoire, S.; et al. A Strategy for Systemic Toxicity Assessment Based on Non-Animal Approaches: The Cosmetics Europe Long Range Science Strategy Programme. Toxicology in Vitro 2018, 50, 137–146. [CrossRef]

- Reisinger, K.; Hoffmann, S.; Alépée, N.; Ashikaga, T.; Barroso, J.; Elcombe, C.; Gellatly, N.; Galbiati, V.; Gibbs, S.; Groux, H.; et al. Systematic Evaluation of Non-Animal Test Methods for Skin Sensitisation Safety Assessment. Toxicol In Vitro 2015, 29, 259–270. [CrossRef]

- Mizumachi, H.; LeBaron, M.J.; Settivari, R.S.; Miyazawa, M.; Marty, M.S.; Sakaguchi, H. Characterization of Dermal Sensitization Potential for Industrial or Agricultural Chemicals with EpiSensA. J Appl Toxicol 2021, 41, 915–927. [CrossRef]

- Kimber, I. The Activity of Methacrylate Esters in Skin Sensitisation Test Methods II. A Review of Complementary and Additional Analyses. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol 2021, 119, 104821. [CrossRef]

- Petry, T.; Bosch, A.; Koraïchi-Emeriau, F.; Eigler, D.; Germain, P.; Seidel, S. Assessment of the Skin Sensitisation Hazard of Functional Polysiloxanes and Silanes in the SENS-IS Assay. Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology 2018, 98, 209–214. [CrossRef]

- Puginier, M.; Roso, A.; Groux, H.; Gerbeix, C.; Cottrez, F. Strategy to Avoid Skin Sensitization: Application to Botanical Cosmetic Ingredients. Cosmetics 2022, 9, 40. [CrossRef]

- Kolle, S.N.; Flach, M.; Kleber, M.; Basketter, D.A.; Wareing, B.; Mehling, A.; Hareng, L.; Watzek, N.; Bade, S.; Funk-Weyer, D.; et al. Plant Extracts, Polymers and New Approach Methods: Practical Experience with Skin Sensitization Assessment. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol 2023, 138, 105330. [CrossRef]

- Cottrez, F.; Boitel, E.; Berrada-Gomez, M.-P.; Dalhuchyts, H.; Bidan, C.; Rattier, S.; Ferret, P.-J.; Groux, H. In Vitro Measurement of Skin Sensitization Hazard of Mixtures and Finished Products: Results Obtained with the SENS-IS Assays. Toxicology in Vitro 2020, 62, 104644. [CrossRef]

- Reinke, E.N.; Corsini, E.; Ono, A.; Fukuyama, T.; Ashikaga, T.; Gerberick, G.F. Peer Review Report of the EpiSensA Skin Sensitization Assay. 2023.

- OECD Test Guideline No. 442D In Vitro Skin Sensitisation_KE2_ARE-Nrf2 Luciferase Test Method; OECD Guidelines for the Testing of Chemicals, Section 4; OECD: Paris, France, 2022;

- Cottrez, F.; Boitel, E.; Ourlin, J.-C.; Peiffer, J.-L.; Fabre, I.; Henaoui, I.-S.; Mari, B.; Vallauri, A.; Paquet, A.; Barbry, P.; et al. SENS-IS, a 3D Reconstituted Epidermis Based Model for Quantifying Chemical Sensitization Potency: Reproducibility and Predictivity Results from an Inter-Laboratory Study. Toxicology in Vitro 2016, 32, 248–260. [CrossRef]

- Na, M.; O’Brien, D.; Lavelle, M.; Lee, I.; Gerberick, G.F.; Api, A.M. Weight of Evidence Approach for Skin Sensitization Potency Categorization of Fragrance Ingredients. Dermatitis 2022, 33, 161–175. [CrossRef]

- Basketter, D.; Ashikaga, T.; Casati, S.; Hubesch, B.; Jaworska, J.; de Knecht, J.; Landsiedel, R.; Manou, I.; Mehling, A.; Petersohn, D.; et al. Alternatives for Skin Sensitisation: Hazard Identification and Potency Categorisation: Report from an EPAA/CEFIC LRI/Cosmetics Europe Cross Sector Workshop, ECHA Helsinki, April 23rd and 24th 2015. Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology 2015, 73, 660–666. [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, S.; Mizumachi, H.; Miyazawa, M. Skin Sensitization Potency Prediction Based on Read-Across (RAx) Incorporating RhE-Based Testing Strategy (RTSv1)-Defined Approach: RTSv1-Based RAx. J Appl Toxicol 2024. [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, S.; Mizumachi, H.; Miyazawa, M. Skin Sensitization Potency Prediction Based on Read-Across (RAx) Incorporating RhE-Based Testing Strategy (RTSv1)-Defined Approach: RTSv1-Based RAx. J Appl Toxicol 2025, 45, 620–635. [CrossRef]

- Clouet, E.; Kerdine-Römer, S.; Ferret, P.-J. Comparison and Validation of an in Vitro Skin Sensitization Strategy Using a Data Set of 33 Chemical References. Toxicol In Vitro 2017, 45, 374–385. [CrossRef]

- Bergal, M.; Puginier, M.; Gerbeix, C.; Groux, H.; Roso, A.; Cottrez, F.; Milius, A. In Vitro Testing Strategy for Assessing the Skin Sensitizing Potential of “Difficult to Test” Cosmetic Ingredients. Toxicology in Vitro 2020, 65, 104781. [CrossRef]

- Gautier, F.; Tourneix, F.; Assaf Vandecasteele, H.; van Vliet, E.; Bury, D.; Alépée, N. Read-across Can Increase Confidence in the Next Generation Risk Assessment for Skin Sensitisation: A Case Study with Resorcinol. Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology 2020, 117, 104755. [CrossRef]

- Gilmour, N.; Alépée, N.; Hoffmann, S.; Kern, P.; Vliet, E.V.; Bury, D.; Miyazawa, M.; Nishida, H.; Europe, C. Applying a next Generation Risk Assessment Framework for Skin Sensitisation to Inconsistent New Approach Methodology Information. ALTEX - Alternatives to animal experimentation 2023, 40, 439–451. [CrossRef]

- Cottrez, F.; Boitel, E.; Sahli, E.; Groux, H. Validation of a New 3D Epidermis Model for the SENS-IS Assay to Evaluate Skin Sensitization Potency of Chemicals. Toxicol In Vitro 2025, 106, 106039. [CrossRef]

- Dickson, M.A.; Hahn, W.C.; Ino, Y.; Ronfard, V.; Wu, J.Y.; Weinberg, R.A.; Louis, D.N.; Li, F.P.; Rheinwald, J.G. Human Keratinocytes That Express hTERT and Also Bypass a P16(INK4a)-Enforced Mechanism That Limits Life Span Become Immortal yet Retain Normal Growth and Differentiation Characteristics. Mol Cell Biol 2000, 20, 1436–1447. [CrossRef]

- Smits, J.P.H.; Niehues, H.; Rikken, G.; van Vlijmen-Willems, I.M.J.J.; van de Zande, G.W.H.J.F.; Zeeuwen, P.L.J.M.; Schalkwijk, J.; van den Bogaard, E.H. Immortalized N/TERT Keratinocytes as an Alternative Cell Source in 3D Human Epidermal Models. Sci Rep 2017, 7, 11838. [CrossRef]

- Alloul-Ramdhani, M.; Tensen, C.P.; El Ghalbzouri, A. Performance of the N/TERT Epidermal Model for Skin Sensitizer Identification via Nrf2-Keap1-ARE Pathway Activation. Toxicol In Vitro 2014, 28, 982–989. [CrossRef]

- El Ghalbzouri, A.; Siamari, R.; Willemze, R.; Ponec, M. Leiden Reconstructed Human Epidermal Model as a Tool for the Evaluation of the Skin Corrosion and Irritation Potential According to the ECVAM Guidelines. Toxicol In Vitro 2008, 22, 1311–1320. [CrossRef]

- Brandmair, K.; Dising, D.; Finkelmeier, D.; Schepky, A.; Kuehnl, J.; Ebmeyer, J.; Burger-Kentischer, A. A Novel Three-Dimensional Nrf2 Reporter Epidermis Model for Skin Sensitization Assessment. Toxicology 2024, 503, 153743. [CrossRef]

- Régnier, M.; Staquet, M.J.; Schmitt, D.; Schmidt, R. Integration of Langerhans Cells into a Pigmented Reconstructed Human Epidermis. J Invest Dermatol 1997, 109, 510–512. [CrossRef]

- LeClaire, J.; de Silva, O. Industry Experience with Alternative Methods. Toxicol Lett 1998, 102–103, 575–579. [CrossRef]

- Lukas, M.; Stössel, H.; Hefel, L.; Imamura, S.; Fritsch, P.; Sepp, N.T.; Schuler, G.; Romani, N. Human Cutaneous Dendritic Cells Migrate through Dermal Lymphatic Vessels in a Skin Organ Culture Model. J Invest Dermatol 1996, 106, 1293–1299. [CrossRef]

- Facy, V.; Flouret, V.; Régnier, M.; Schmidt, R. Langerhans Cells Integrated into Human Reconstructed Epidermis Respond to Known Sensitizers and Ultraviolet Exposure. J Invest Dermatol 2004, 122, 552–553. [CrossRef]

- Pichowski, J.S.; Cumberbatch, M.; Dearman, R.J.; Basketter, D.A.; Kimber, I. Allergen-Induced Changes in Interleukin 1 Beta (IL-1 Beta) mRNA Expression by Human Blood-Derived Dendritic Cells: Inter-Individual Differences and Relevance for Sensitization Testing. J Appl Toxicol 2001, 21, 115–121. [CrossRef]

- Chau, D.Y.S.; Johnson, C.; MacNeil, S.; Haycock, J.W.; Ghaemmaghami, A.M. The Development of a 3D Immunocompetent Model of Human Skin. Biofabrication 2013, 5, 035011. [CrossRef]

- Uchino, T.; Takezawa, T.; Ikarashi, Y.; Nishimura, T. Development of an Alternative Test for Skin Sensitization Using a Three-Dimensional Human Skin Model Consisting of Dendritic Cells, Keratinocytes and Fibroblasts. AATEX 2011, 16, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; DiIulio, N.A.; Fairchild, R.L. T Cell Populations Primed by Hapten Sensitization in Contact Sensitivity Are Distinguished by Polarized Patterns of Cytokine Production: Interferon Gamma-Producing (Tc1) Effector CD8+ T Cells and Interleukin (Il) 4/Il-10-Producing (Th2) Negative Regulatory CD4+ T Cells. J Exp Med 1996, 183, 1001–1012. [CrossRef]

- Ouwehand, K.; Spiekstra, S.W.; Waaijman, T.; Scheper, R.J.; de Gruijl, T.D.; Gibbs, S. Technical Advance: Langerhans Cells Derived from a Human Cell Line in a Full-Thickness Skin Equivalent Undergo Allergen-Induced Maturation and Migration. Journal of Leukocyte Biology 2011, 90, 1027–1033. [CrossRef]

- Kosten, I.J.; Spiekstra, S.W.; de Gruijl, T.D.; Gibbs, S. MUTZ-3 Derived Langerhans Cells in Human Skin Equivalents Show Differential Migration and Phenotypic Plasticity after Allergen or Irritant Exposure. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 2015, 287, 35–42. [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Greenstein, T.; Shi, L.; Maguire, T.; Schloss, R.; Yarmush, M. Tri-Culture System for pro-Hapten Sensitizer Identification and Potency Classification. Technology (Singap World Sci) 2018, 6, 67–74. [CrossRef]

- Zoio, P.; Oliva, A. Skin-on-a-Chip Technology: Microengineering Physiologically Relevant In Vitro Skin Models. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 682. [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Carro, E.; Angenent, M.; Gracia-Cazaña, T.; Gilaberte, Y.; Alcaine, C.; Ciriza, J. Modeling an Optimal 3D Skin-on-Chip within Microfluidic Devices for Pharmacological Studies. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 1417. [CrossRef]

- Jones, C.F.E.; Di Cio, S.; Connelly, J.T.; Gautrot, J.E. Design of an Integrated Microvascularized Human Skin-on-a-Chip Tissue Equivalent Model. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2022, 10. [CrossRef]

- Hindle, S.A.; Bachas Brook, H.; Chrysanthou, A.; Chambers, E.S.; Caley, M.P.; Connelly, J.T. Replicating Dynamic Immune Responses at Single-Cell Resolution within a Microfluidic Human Skin Equivalent. Adv Sci (Weinh) 2025, 12, e2415717. [CrossRef]

- Wufuer, M.; Lee, G.; Hur, W.; Jeon, B.; Kim, B.J.; Choi, T.H.; Lee, S. Skin-on-a-Chip Model Simulating Inflammation, Edema and Drug-Based Treatment. Sci Rep 2016, 6, 37471. [CrossRef]

- Ramadan, Q.; Ting, F.C.W. In Vitro Micro-Physiological Immune-Competent Model of the Human Skin. Lab Chip 2016, 16, 1899–1908. [CrossRef]

- Moon, S.; Kim, D.H.; Shin, J.U. In Vitro Models Mimicking Immune Response in the Skin. Yonsei Med J 2021, 62, 969–980. [CrossRef]

- Yarmush, M.L.; Freedman, R.; Bufalo, A.D.; Teissier, S.; Meunier, J.-R. Immune System Modeling Devices and Methods 2017.

- Zhang, Q.; Sito, L.; Mao, M.; He, J.; Zhang, Y.S.; Zhao, X. Current Advances in Skin-on-a-Chip Models for Drug Testing. Microphysiological Systems 2018, 2. [CrossRef]

- Ren, X.; Getschman, A.E.; Hwang, S.; Volkman, B.F.; Klonisch, T.; Levin, D.; Zhao, M.; Santos, S.; Liu, S.; Cheng, J.; et al. Investigations on T Cell Transmigration in a Human Skin-on-Chip (SoC) Model. Lab Chip 2021, 21, 1527–1539. [CrossRef]

- Quan, Q.; Weng, D.; Li, X.; An, Q.; Yang, Y.; Yu, B.; Ma, Y.; Wang, J. Analysis of Drug Efficacy for Inflammatory Skin on an Organ-Chip System. Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology 2022, 10.

- Sasaki, N.; Tsuchiya, K.; Kobayashi, H. Photolithography-free Skin-on-a-chip for Parallel Permeation Assays. Sensors and Materials 2019, 31, 107–115. [CrossRef]

- Cho, S.W.; Malick, H.; Kim, S.J.; Grattoni, A. Advances in Skin-on-a-Chip Technologies for Dermatological Disease Modeling. J Invest Dermatol 2024, 144, 1707–1715. [CrossRef]

- Govey-Scotland, J.; Johnstone, L.; Myant, C.; Friddin, M.S. Towards Skin-on-a-Chip for Screening the Dermal Absorption of Cosmetics. Lab Chip 2023, 23, 5068–5080. [CrossRef]

- Ta, G.H.; Weng, C.-F.; Leong, M.K. In Silico Prediction of Skin Sensitization: Quo Vadis? Front Pharmacol 2021, 12, 655771. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Huang, Z.; Lou, S.; Li, W.; Liu, G.; Tang, Y. In Silico Prediction of Skin Sensitization for Compounds via Flexible Evidence Combination Based on Machine Learning and Dempster–Shafer Theory. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2024, 37, 894–909. [CrossRef]

- Wilm, A.; Kühnl, J.; Kirchmair, J. Computational Approaches for Skin Sensitization Prediction. Critical Reviews in Toxicology 2018, 48, 738–760. [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.-S.; Wang, C.-C.; Tung, C.-W. SkinSensPred as a Promising in Silico Tool for Integrated Testing Strategy on Skin Sensitization. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2022, 19, 12856. [CrossRef]

- Kan, H.-L.; Wang, S.-S.; Liao, C.-L.; Tsai, W.-R.; Wang, C.-C.; Tung, C.-W. An Integrated Testing Strategy and Online Tool for Assessing Skin Sensitization of Agrochemical Formulations. Toxics 2024, 12, 936. [CrossRef]

- Asai, T.; Umeshita, K.; Sakurai, M.; Sakane, S. Development of an in Silico Evaluation System That Quantitatively Predicts Skin Sensitization Using OECD Guideline No. 497 ITSv2 Defined Approach for Skin Sensitization Classification. Food and Chemical Toxicology 2024, 185, 114444. [CrossRef]

- Wilm, A.; Stork, C.; Bauer, C.; Schepky, A.; Kühnl, J.; Kirchmair, J. Skin Doctor: Machine Learning Models for Skin Sensitization Prediction That Provide Estimates and Indicators of Prediction Reliability. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2019, 20, 4833. [CrossRef]

- Tieghi, R.S.; Moreira-Filho, J.T.; Martin, H.-J.; Wellnitz, J.; Otoch, M.C.; Rath, M.; Tropsha, A.; Muratov, E.N.; Kleinstreuer, N. A Novel Machine Learning Model and a Web Portal for Predicting the Human Skin Sensitization Effects of Chemical Agents. Toxics 2024, 12, 803. [CrossRef]

- Rogiers, V.; Benfenati, E.; Bernauer, U.; Bodin, L.; Carmichael, P.; Chaudhry, Q.; Coenraads, P.J.; Cronin, M.T.D.; Dent, M.; Dusinska, M.; et al. The Way Forward for Assessing the Human Health Safety of Cosmetics in the EU - Workshop Proceedings. Toxicology 2020, 436, 152421. [CrossRef]

- Basketter, D.; Safford, B. Skin Sensitization Quantitative Risk Assessment: A Review of Underlying Assumptions. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol 2016, 74, 105–116. [CrossRef]

- Teunis, M.; Corsini, E.; Smits, M.; Madsen, C.B.; Eltze, T.; Ezendam, J.; Galbiati, V.; Gremmer, E.; Krul, C.; Landin, A.; et al. Transfer of a Two-Tiered Keratinocyte Assay: IL-18 Production by NCTC2544 to Determine the Skin Sensitizing Capacity and Epidermal Equivalent Assay to Determine Sensitizer Potency. Toxicology in Vitro 2013, 27, 1135–1150. [CrossRef]

- Corsini, E.; Gibbs, S.; Roggen, E.; Kimber, I.; Basketter, D.A. Skin Sensitization Tests: The LLNA and the RhE IL-18 Potency Assay. Methods Mol Biol 2021, 2240, 13–29. [CrossRef]

- Andres, E.; Barry, M.; Hundt, A.; Dini, C.; Corsini, E.; Gibbs, S.; Roggen, E.L.; Ferret, P.-J. Preliminary Performance Data of the RHE/IL-18 Assay Performed on SkinEthicTM RHE for the Identification of Contact Sensitizers. Int J Cosmet Sci 2017, 39, 121–132. [CrossRef]

- de Souza, I.R.; Iulini, M.; Galbiati, V.; Silva, E.Z.M.; Sivek, T.W.; Rodrigues, A.C.; Gradia, D.F.; Pestana, C.B.; Leme, D.M.; Corsini, E. An Integrated in Silico-in Vitro Investigation to Assess the Skin Sensitization Potential of 4-Octylphenol. Toxicology 2023, 493, 153548. [CrossRef]

- Mehling, A.; Adriaens, E.; Casati, S.; Hubesch, B.; Irizar, A.; Klaric, M.; Letasiova, S.; Manou, I.; Müller, B.P.; Roggen, E.; et al. In Vitro RHE Skin Sensitisation Assays: Applicability to Challenging Substances. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol 2019, 108, 104473. [CrossRef]

- Reinke, E. N; Hines, R. N; Strickland, J; Casey, W. Integrated Approaches for Skin Sensitization: Regulatory Status and Future Opportunities.; NTP / ICCVAM: Nashville, TN, USA, 2023.

- Kasahara, T.; Yamamoto, Y.; Nakashima, N.; Imamura, M.; Mizumachi, H.; Suzuki, S.; Aiba, S.; Kimura, Y.; Ashikaga, T.; Kojima, H.; et al. Borderline Range Determined Using Data From Validation Study of Alternative Methods for Skin Sensitization: ADRA, IL-8 Luc Assay, and EpiSensA. J Appl Toxicol 2025, 45, 432–439. [CrossRef]

- Pellevoisin, C.; Cottrez, F.; Johansson, J.; Pedersen, E.; Coleman, K.; Groux, H. Pre-Validation of SENS-IS Assay for in Vitro Skin Sensitization of Medical Devices. Toxicol In Vitro 2021, 71, 105068. [CrossRef]

- Facy, V.; Flouret, V.; Régnier, M.; Schmidt, R. Reactivity of Langerhans Cells in Human Reconstructed Epidermis to Known Allergens and UV Radiation. Toxicology in Vitro 2005, 19, 787–795. [CrossRef]

- Gaviria Agudelo, C. Modelling Human Skin: Organotypic Cultures for Applications in Toxicology, Immunity, and Cancer:, University of Groningen, 2022.

- Laubach, V.; Zöller, N.; Rossberg, M.; Görg, K.; Kippenberger, S.; Bereiter-Hahn, J.; Kaufmann, R.; Bernd, A. Integration of Langerhans-like Cells into a Human Skin Equivalent. Arch Dermatol Res 2011, 303, 135–139. [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Dong, D.X.; Jindal, R.; Maguire, T.; Mitra, B.; Schloss, R.; Yarmush, M. Predicting Full Thickness Skin Sensitization Using a Support Vector Machine. Toxicol In Vitro 2014, 28, 1413–1423. [CrossRef]

- Bock, S.; Said, A.; Müller, G.; Schäfer-Korting, M.; Zoschke, C.; Weindl, G. Characterization of Reconstructed Human Skin Containing Langerhans Cells to Monitor Molecular Events in Skin Sensitization. Toxicol In Vitro 2018, 46, 77–85. [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues Neves, C.; Gibbs, S. Progress on Reconstructed Human Skin Models for Allergy Research and Identifying Contact Sensitizers. In Three Dimensional Human Organotypic Models for Biomedical Research; Bagnoli, F., Rappuoli, R., Eds.; Current Topics in Microbiology and Immunology; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2021; pp. 103–129 ISBN 978-3-030-62452-1.

- Schellenberger, M.T.; Bock, U.; Hennen, J.; Groeber-Becker, F.; Walles, H.; Blömeke, B. A Coculture System Composed of THP-1 Cells and 3D Reconstructed Human Epidermis to Assess Activation of Dendritic Cells by Sensitizing Chemicals after Topical Exposure. Toxicology in Vitro 2019, 57, 62–66. [CrossRef]

- Hölken, J.M.; Friedrich, K.; Merkel, M.; Blasius, N.; Engels, U.; Buhl, T.; Mewes, K.R.; Vierkotten, L.; Teusch, N.E. A Human 3D Immune Competent Full-Thickness Skin Model Mimicking Dermal Dendritic Cell Activation. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14. [CrossRef]

- Hölken, J.M.; Wurz, A.-L.; Friedrich, K.; Böttcher, P.; Asskali, D.; Stark, H.; Breitkreutz, J.; Buhl, T.; Vierkotten, L.; Mewes, K.R.; et al. Incorporating Immune Cell Surrogates into a Full-Thickness Tissue Equivalent of Human Skin to Characterize Dendritic Cell Activation. Sci Rep 2024, 14, 30158. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).