1. Introduction

Membrane distillation is a thermally driven separation process that leverages vapor pressure differences to facilitate the diffusion of water vapor through a hydrophobic membrane, effectively isolating salts and other impurities. The technique is adaptable to various configurations, each suited to specific applications and offering distinct advantages, such as direct contact membrane distillation (DCMD) [

1,

2], air gap membrane distillation (AGMD) [

3,

4], sweeping gas membrane distillation (SGMD) [

5,

6], and vacuum membrane distillation (VMD) [

7,

8].

Water gap membrane distillation (WGMD) has emerged as a promising technology for water desalination. In a conventional WGMD configuration, a stagnant layer of distillate water is maintained on the cold side of a hydrophobic membrane, serving as the permeate for the module. Additionally, a cooling fluid is separated from the permeate by a cooling plate, ensuring that the water gap receives adequate cooling. This configuration enhances the water output flux of WGMD compared to air gap membrane distillation (AGMD) systems [

9,

10,

11,

12]. Furthermore, WGMD modules exhibit superior thermal efficiency, resulting in lower thermal energy consumption when compared to direct contact membrane distillation (DCMD) modules [

13,

14].

Numerous studies have investigated the conventional WGMD configuration as a viable technology for desalinating saline water, focusing on enhancing the performance of various WGMD modules [

15,

16,

17]. Lawal et al. [

18] conducted experimental investigations to assess the impact of different cooling plate materials on the performance of plate and frame WGMD modules under various feed and coolant operating conditions. In their experiments, the water gap thickness was maintained at 5 mm, the module length at 40 mm and seawater salinity at the feed inlet was considered for all test cases. The results indicated that increasing the thermal conductivity of the cooling plate positively influenced the module’s output flux, achieving a maximum flux of 32 kg/(m

2h) when utilizing a copper cooling plate (the most conductive material studied) at feed and coolant inlet temperatures of 70 °C and 15 °C, respectively, with a feed flow rate of 1.2 L/min. The gained output ratio (GOR) of the module was approximately 0.38. Furthermore, reducing the feed flow rate improved the thermal performance of the module, resulting in a GOR of 0.42 at a flow rate of 0.6 L/min, under the same temperature conditions. Notably, the use of a stainless-steel plate yielded a slightly higher GOR of about 0.43 under identical operating conditions. Elsheniti et al. [

13] conducted a comparative numerical study between DCMD and WGMD hollow fiber (HF) modules. They developed a two-dimensional axisymmetric transient computational fluid dynamics (CFD) model to simulate the concentrating process of feed water while recirculating through the modules’ feed channels. The study was performed at three different feed tank temperature levels, maintaining the effective module length at 100 mm, with an initial feed salinity of 70000 ppm and permeate (for DCMD) and coolant (for WGMD) inlet temperatures set at 20 °C. The findings indicated that the WGMD desalination system achieved an average water flux of 8.85 kg/(m

2h). In comparison, the DCMD system demonstrated a 25.4% increase in flux at a feed tank temperature of 70 °C while concentrating feed water to 233333 ppm. However, WGMD demonstrated superior energy efficiency, with specific thermal energy consumption (STEC) recorded at 903 kWh/m

3, compared to 1026 kWh/m

3 for the DCMD system under similar conditions while concentrating feed water to 100000 ppm. The GOR for WGMD was 0.72, whereas it was 0.63 for DCMD at the same operational parameters.

Several studies have explored unconventional WGMD modules, such as material gap or conductive gap membrane distillation modules [

19,

20,

21], aimed at enhancing the transport properties of the module gap. Other research efforts have proposed the incorporation of external sources to improve the characteristics of the conventional water gap, such as the use of a rotating impeller [

22,

23]. For instance, Lawal [

22] experimentally examined the performance of a WGMD module equipped with a circulation impeller placed within the water gap to enhance transport characteristics. The study evaluated the effect of impeller rotation speed on the performance of a module with a length of 90.25 mm and a gap thickness of 11 mm at a salinity of 4080 ppm. The results indicated that increasing the impeller speed up to 1100 rev/min significantly improved the overall performance of the module, with a 153.1% increase in flux compared to the conventional WGMD module with a stagnant water gap at feed and coolant inlet temperatures of 70 °C and 20 °C, respectively. Moreover, the STEC of the module was reduced to 1400 kWh/m

3, achieving a 12.2% reduction compared to the conventional WGMD module under the same temperature conditions.

Despite ongoing research aimed at enhancing the thermal performance of WGMD systems, significant improvements are still needed. One effective strategy for reducing thermal energy consumption in WGMD modules involves implementing a multistage (MS) arrangement, which incorporates multiple modules in series [

24,

25,

26]. Series connection enables the feed water to be expelled at lower temperature levels while maximizing the distillate water extraction. In the meanwhile, thermal energy gained through the coolant channel is recovered to preheat saline water before it enters the feed channel. For instance, Alawad et al. [

27] experimentally investigated the influence of various operating conditions, including feed and coolant inlet temperatures and flow rates, on the thermal performance of a multistage WGMD desalination system. This MS-WGMD system, consisting of four stages arranged in series, was evaluated with a fixed feed inlet salinity of 250 ppm. The study revealed that the four-stage system achieved an STEC of 1543 kWh/m

3, representing a 50.6% reduction in STEC compared to a single module at feed and coolant inlet temperatures of 70 °C and 25 °C, respectively. Additionally, the GOR was measured at 0.43, indicating an increase of 104.8% over that of the single module under the same feed and coolant inlet temperatures. Another tactic to make the module more compact, Elbessomy et al. [

28] examined the impact of helical configurations of single and double hollow fibers inserted within the cooling tubes on the productivity and thermal performance. The results indicated that single helical fiber modules enhanced water flux by approximately 11.4% at feed and coolant inlet temperatures of 70 °C and 20 °C, respectively, while double helical fibers showed only an 8.07% increase under the same conditions. Furthermore, the study demonstrated that increasing fiber length through helical configuration could reduce the module’s STEC from 6000 kWh/m

3 for a straight single fiber to 3900 kWh/m

3 for a single fiber with 50 helical turns. Notably, employing up to three stages of helical single fiber modules in series could further decrease the desalination system’s STEC to 1800 kWh/m

3.

A review of the literature reveals a gap in CFD simulations addressing the circulating water gap process, particularly within the context of hollow-fiber membrane distillation. Most to date studies focus on conventional stagnant water gap configurations, overlooking the impact of circulation with the hollow fiber membrane configurations. To address this gap, this study develops a theoretical framework and a CFD simulation to implement and analyze the circulating water gap in HF-WGMD modules to be compared with conventional modules. A two-dimensional axisymmetric mathematical model is established, incorporating mass, momentum and energy conservation equations to simulate the transport phenomena across the feed channel, membrane, water gap, cooling tube and coolant stream. The model provides a detailed assessment of temperature and concentration distributions, offering new insights into the influence of water gap circulation against conventional stagnant water gap configuration. A parametric study evaluates key operational factors, including feed and coolant velocities, temperatures and circulating water gap flow rate. Unlike previous studies [

13,

15,

28], the current work investigates the influence of turbulent flow regime for the different module streams on the HF-WGMD module productivity. Furthermore, the performance of a multistage circulating HF-WGMD module is evaluated and compared with that of a conventional stagnant configuration. Comparative analyses based on permeate flux and STEC are carried out to explore the limitations of water gap circulation in enhancing module productivity and thermal efficiency, offering new insights into the design and optimization of high-performance HF-WGMD systems.

3. Methodology

A 2D axisymmetric model is introduced in this study to simulate the mass, momentum and heat transport physics in HF-WGMD system with both stagnant and circulation water gap configurations. The model is constructed using the fundamental principles of mass, momentum, and energy conservations.

To simplify the computational process while preserving solution accuracy, the following assumptions are considered:

The hollow fiber membrane and cooling tube are perfectly concentric.

The hollow fiber membrane exhibits uniform and isotropic porosity.

Fouling at the feed-membrane interface is neglected.

Pore wetting within the membrane is assumed to be absent.

Heat loss from the WGMD module is considered negligible.

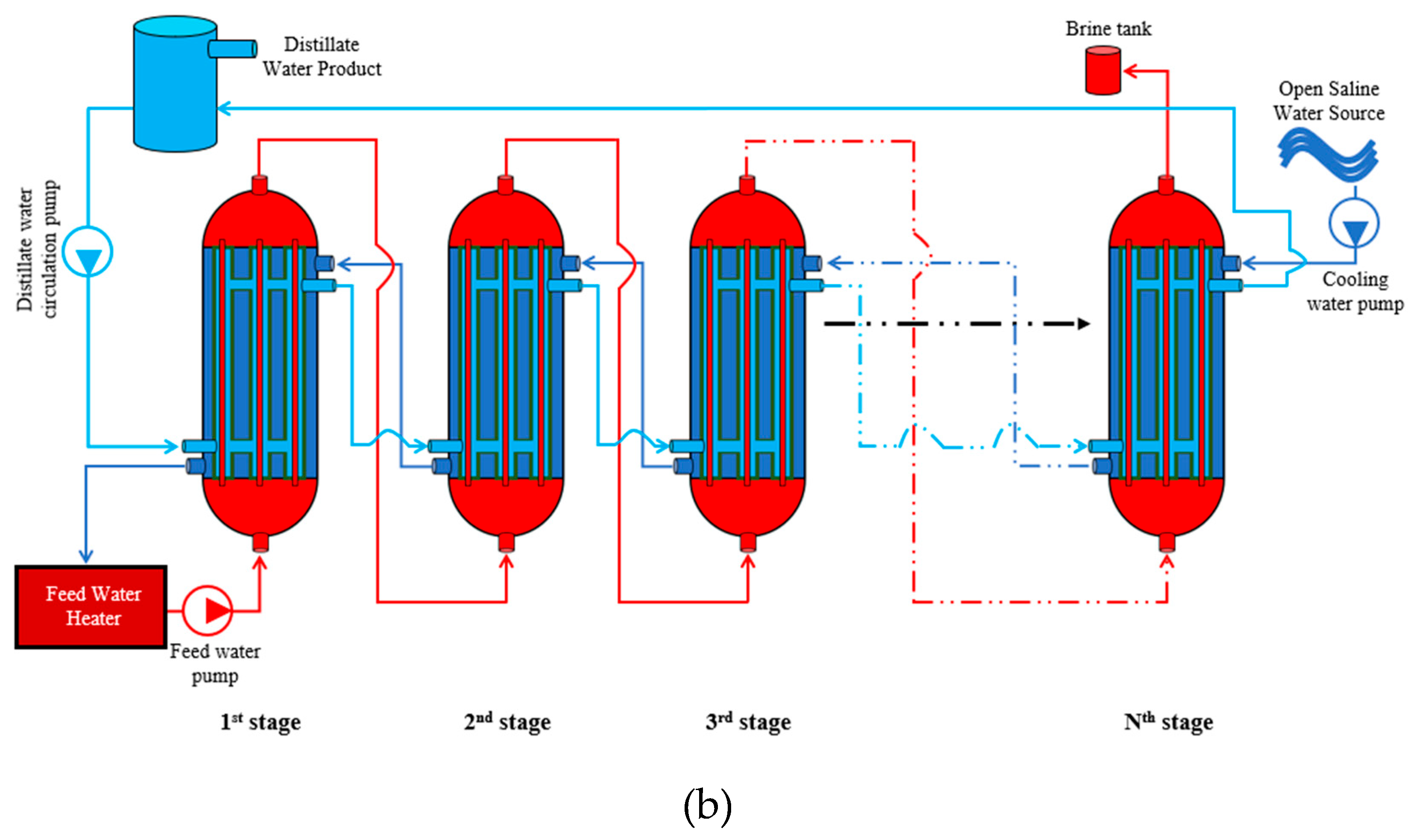

The model includes five domains entitled; feed channel, hollow fiber membrane layer, water gap, cooling tube, and cooling channel, as depicted in

Figure 3. Whereas the distillate water is considered stagnant in the water gap,

Figure 3 (a), it is circulated using an external water pump as shown in

Figure 3 (b).

Table 1 outlines the defined dimensional parameters and operational conditions of the primary module, offering a detailed summary of the system’s specifications.

3.1. Governing Equations

3.1.1. Mass Transport

The concentration balance is applied for feed and membrane domains to determine the distribution of water concentration. In the feed domain, both convection and diffusion terms are considered in Fick’s law, which is mathematically described as follows:

where,

represents the water concentration within the feed channel,

and

denote the velocity components of the feed flow in the radial

and axial

directions, respectively. The mutual diffusion coefficient of water and salt,

, is determined using the Wilke-Chang equation [

29]:

where,

is the feed water local temperature,

represents the molecular mass of feed solution,

is the dynamic viscosity of the feed fluid in cP and

is the molecular volume of water in cm

3/mol.

Conversely, within the membrane domain, mass transport is governed exclusively by diffusion only, as water vapor molecules pass through the membrane pores via the diffusion mechanism. That is modeled using Fick’s law as follows:

Here, is the local vapor concentration in membrane layer, denotes the diffusion coefficient of water vapor through the membrane.

Diffusion mechanism in hydrophobic membranes is influenced by the characteristics of the transported species in addition to membrane’s intrinsic properties. In MD, the primary transport mechanisms are typically Knudsen diffusion, molecular diffusion, and Poiseuille flow. The effective diffusion mechanisms in the membrane model are identified by calculating the Knudsen number

, a dimensionless parameter that quantifies the dominant transport mechanisms, as expressed by the following equation [

30]:

Here,

is the membrane’s pore diameter, equals to 0.16 μm in the current study, while

denotes the mean free path of vapor molecules and can be calculated using the following equation:

In this equation,

represents the average membrane temperature,

is pressure, and

is Boltzmann constant. The molecular collision diameters for air and water are denoted as

and

, respectively [

31]. Additionally,

and

represent the molecular masses of air and water, respectively

and

.

In this study, the calculated Knudsen number falls within the transition region

, indicating that the diffusion process is influenced by both Knudsen diffusion and ordinary molecular diffusion. The effective diffusion coefficient is then calculated as the combined contribution of these two mechanisms as follows.

where

indicates the membrane porosity, and

represents the tortuosity of the membrane pores, which can be estimated using the following equation [

32]:

The coefficients for Knudsen diffusion and the ordinary diffusion of vapor in air can be determined using the following equations [

30]:

3.1.2. Momentum Transport

To obtain the velocity and pressure distributions within the feed, circulating water gap, and cooling channel domains, the governing continuity and Navier-Stokes equations for fluid flow are solved. For 2D-axisymmetric, steady and incompressible, these equations are expressed as follows [

33]:

where,

and

are the fluid density and dynamic viscosity, respectively.

is the turbulent viscosity and set to zero in the laminar flow cases while the realizable

turbulence model, implemented within COMSOL Multiphysics software, is employed to solve for

in the Reynolds-averaged Navier-Stokes (RANS) equations used for turbulent flow cases.

3.1.3. Energy Transport

The temperature distribution is an important factor in the MD process, as it directly impacts the calculations of diffusion coefficients and saturation concentrations. Consequently, the energy conservation equation is solved concurrently with the mass and momentum transport equations to determine the local temperature distribution throughout the entire module. Thermal energy transfer equation, encompassing both convection and conduction, is considered for feed, circulating water gap, and cooling channels and is expressed as follows:

where,

is temperature,

is the thermal conductivity and

is the specific heat of the fluid.

In contrast, only conduction-driven heat transfer is considered in the energy conservation equation for the HF membrane, stagnant water gap, and cooling tube domains and can be presented as follows:

For the membrane layer, the thermal conductivity

is determined using the following equation:

Here,

represents the thermal conductivity of the Polyvinylidene Fluoride (PVDF) membrane’s solid matrix.

denotes the thermal conductivity of water vapor, and it is estimated by the subsequent equation [

34]:

3.2. Boundary Conditions

The boundary conditions used with the mass, momentum and energy transport equations are listed in the following tables.

3.2.1. Mass Transport

The boundary conditions for the mass transport equation, applied to both the feed and membrane domains, are summarized in

Table 2.

Here,

represents water vapor concentration at the feed-membrane interface,

denotes water vapor concentration at the membrane-water gap interface. These values correspond to the saturation state of water vapor on both sides of membrane, driven by feed water evaporation at the feed side and vapor condensation at the water gap side. The saturation pressures associated with these concentrations are determined using the Antoine equation [

35] as follows:

Here,

and

represent the saturation pressures at the feed-membrane and membrane-water gap interfaces, respectively. Whereas

represents the water mole fraction and

refers to the water activity coefficient. Both

and

are determined as follows [

34]:

where,

is the mole fraction of salt in the feed solution.

The vapor concentrations at feed-membrane and membrane-water gap interfaces are derived from the corresponding saturation vapor pressures, as in the following equations:

where,

represents the saturation concentration of water vapor,

is the molecular mass of water,

is the atmospheric pressure,

is the specific volume of water vapor,

is the local temperature at the membrane interfaces, and

denotes the vapor content.

3.2.2. Momentum Transport

Table 3 outlines the boundary conditions employed for momentum transport physics across the feed, circulating water gap, and cooling channel domains.

3.2.3. Energy Transport

The energy equation, for all domains, is solved by considering the boundary conditions presented in

Table 4.

During the evaporation of water at the feed-membrane interface, latent heat is absorbed from the feed water. On the opposite side of the membrane, the vapor condenses, releasing heat into the water gap. To model this thermal behavior, a heat sink boundary condition is applied at the feed-membrane interface. Whereas, a heat source boundary condition is applied at the membrane-water interface. The corresponding heat values is determined as follows:

where

is the diffusive mass flux and

is the latent heat of vaporization or condensation which can be determined using the following equation:

where,

is the membrane local temperature for both membrane interfaces.

3.3. Specific Thermal Energy Consumption

To assess the thermal performance of the desalination module, STEC is employed as a key indicator. STEC represents the amount of thermal energy consumed by the desalination system per unit mass of produced permeate and is expressed in kWh/m3. It is determined using the following equation:

where denotes the feed mass flow rate in kg/s, represents the specific heat capacity of the feed water, and correspond to the feed inlet and coolant outlet temperatures, respectively, refers to the permeate flux, and is the membrane surface area in m2.

3.4. Solving Technique

The finite element approach built in COMSOL Multiphysics is used to solve the current mathematical model. The transport of mass, momentum and heat across the five domains depicted in

Figure 3 is solved by means of COMSOL’s built-in modules. User-defined options and variables are used to integrate the rest of expressions (Eqs. 2, 6-10, 18, and 19).

The entire mathematical model is solved instantaneously across all domains as a totally coupled system. Throughout the analysis, the salt concentration is eliminated from the water gap space and considered to be 35000 ppm at the inlet of the feed channel. As a result, the concentration convection-diffusion balance is used to model the distribution of water and salt concentrations in the feed channel.

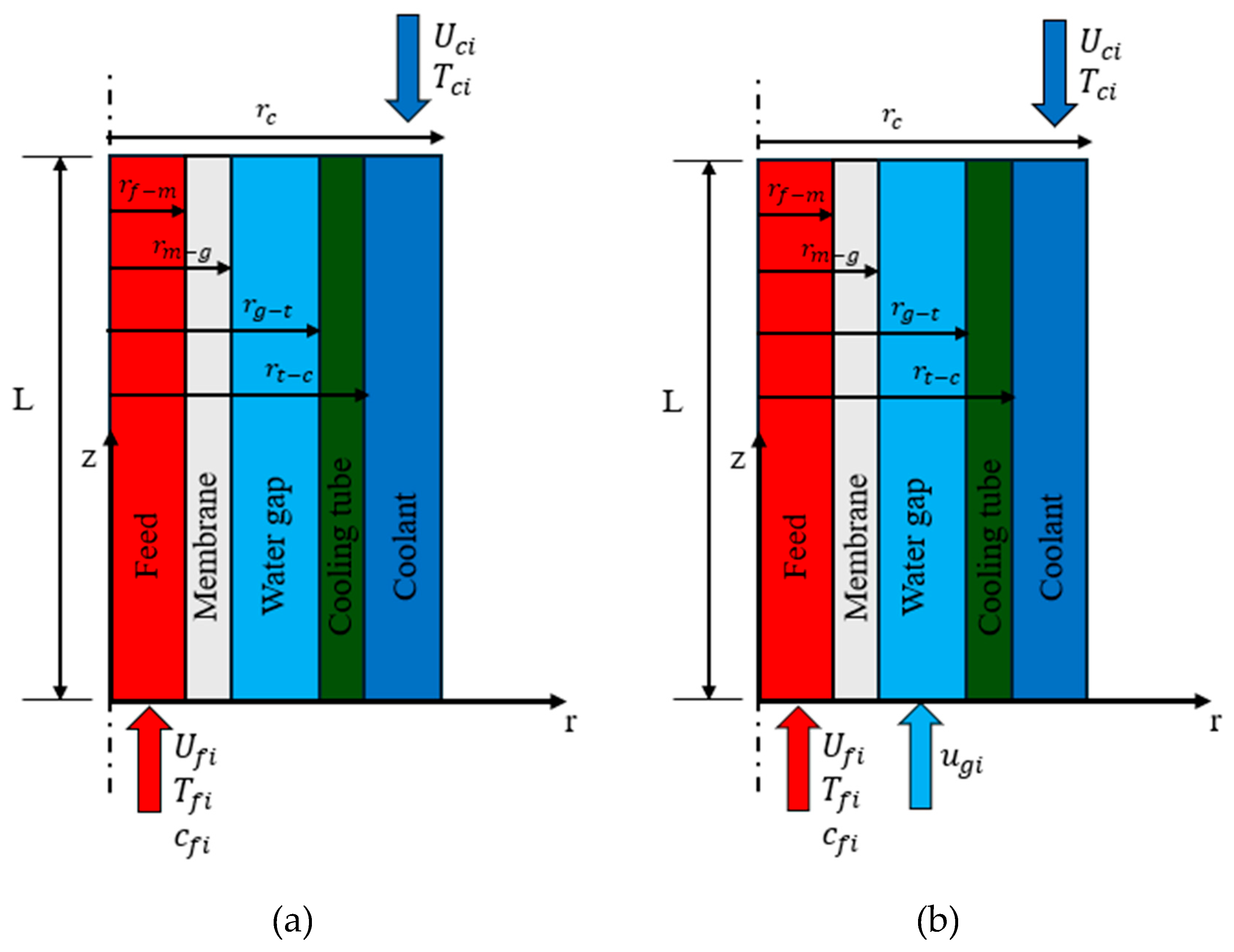

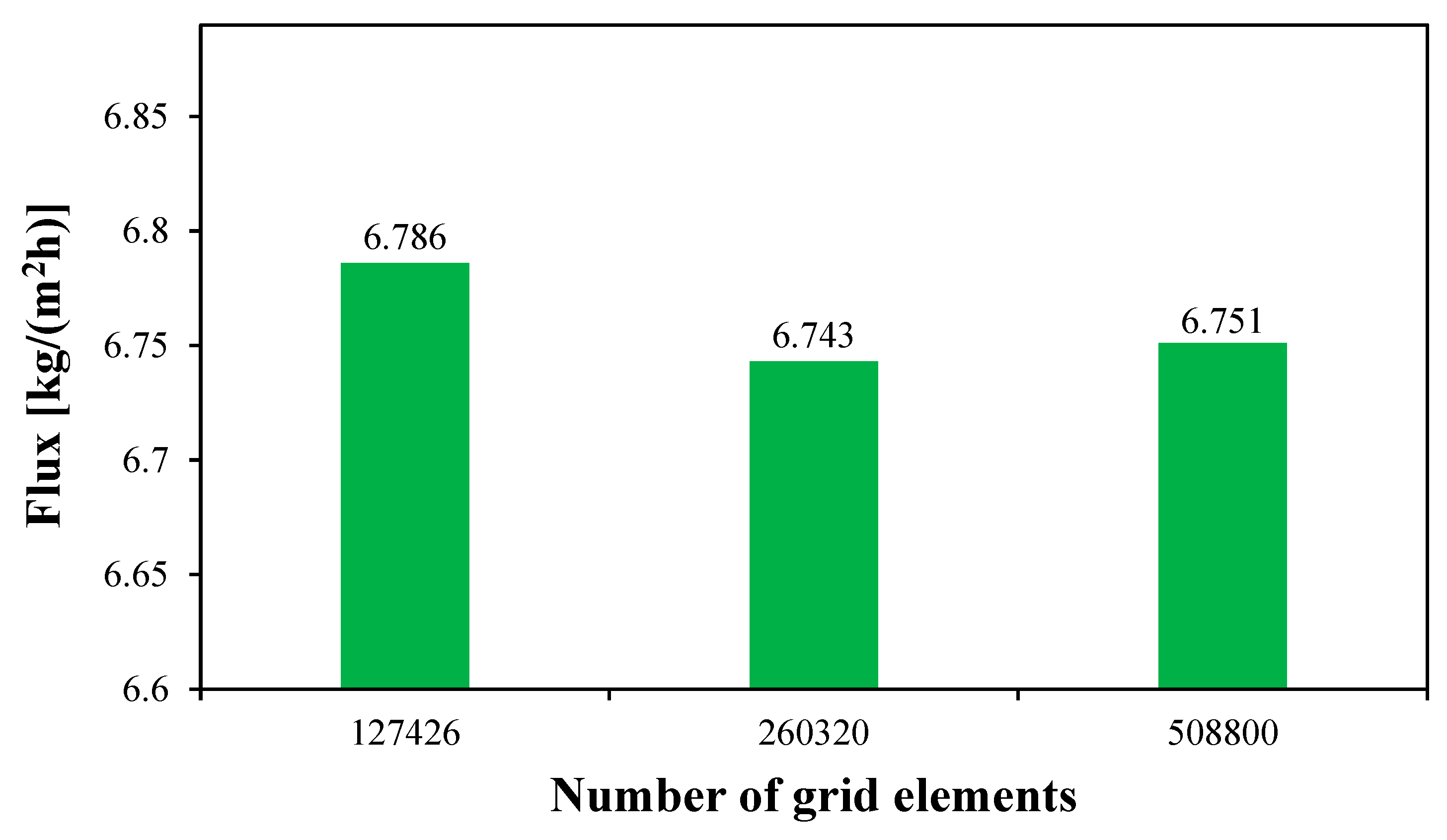

3.5. Study on the Number of Grid Elements

The gird independence test is performed on a circulating HF-WGMD module of the length of 100 mm with Reynolds number of 2760, 146 and 2712 in the feed, coolant, and water gap, respectively. The feed inlet temperature is kept at 50 °C with a salinity of 35000 ppm. Three different grid levels (127426, 260320 and 508800 elements) were used to test the CFD in this study. As illustrated in

Figure 4, using 260320 of grid elements is excessively satisfactory at which the produced flux deviates only by 0.12% when doubling the number of grid elements to 508800. So that, driving the numerical analysis using 260320 number of grid elements can save the computational time with low level of discretization error.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.O.E. and M.B.E.; Methodology, M.O.E. and M.B.E.; Software, M.O.E., K.W.F. and M.B.E.; Validation, M.O.E. and K.W.F.; Formal analysis, M.O.E., K.W.F., M.B.E. and A.R.; Investigation, M.O.E., K.W.F., M.B.E., A.R. and O.A.E.; Data curation, M.O.E. and M.B.E.; Writing—original draft, M.O.E. and K.W.F.; Writing—review & editing, A.R., M.B.E. and O.A.E.; Visualization, S.M.E. and A.R.; Supervision, M.B.E., S.M.E. and O.A.E.; Funding acquisition, M.B.E. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

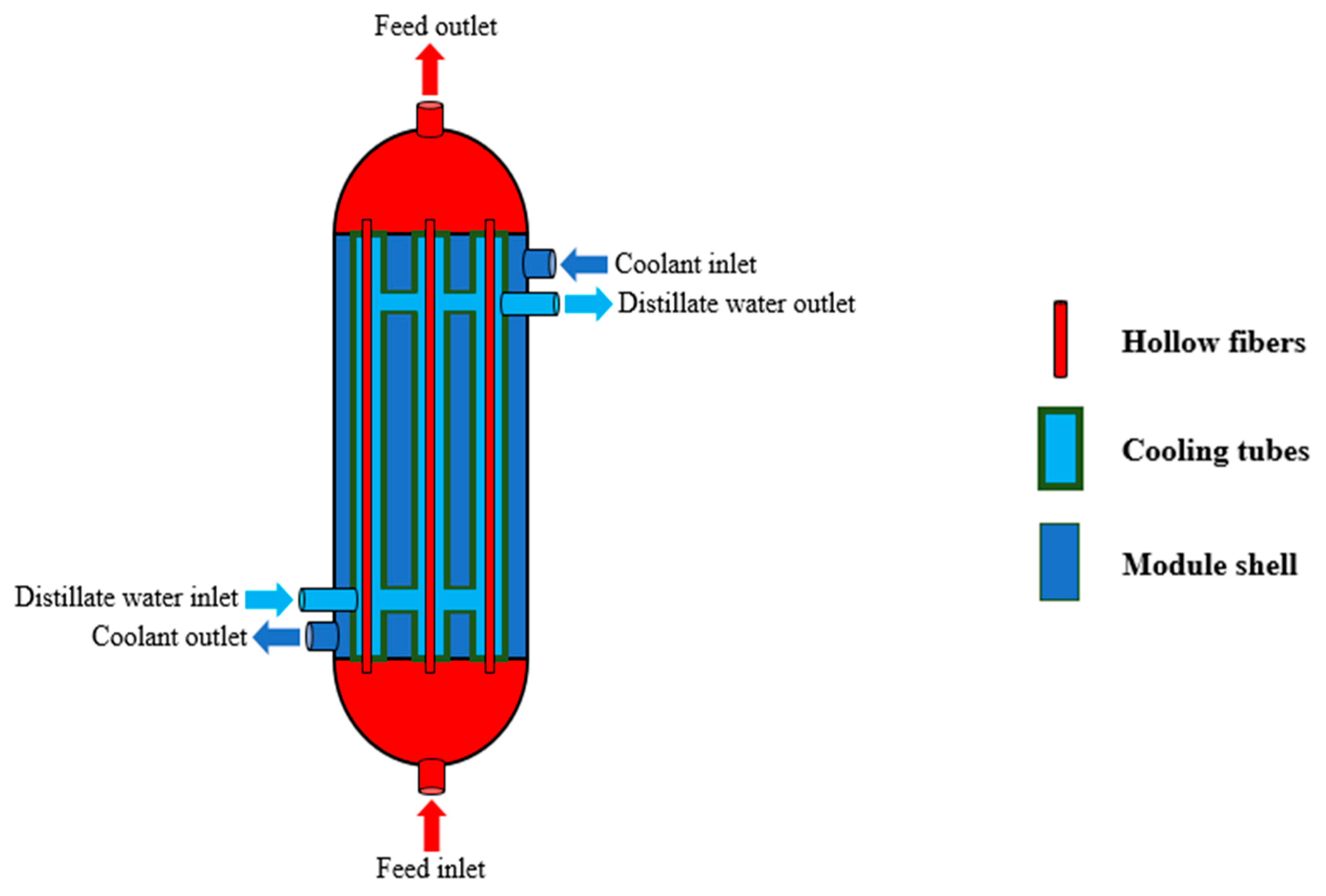

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of the HF-WGMD module with circulating water gap.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of the HF-WGMD module with circulating water gap.

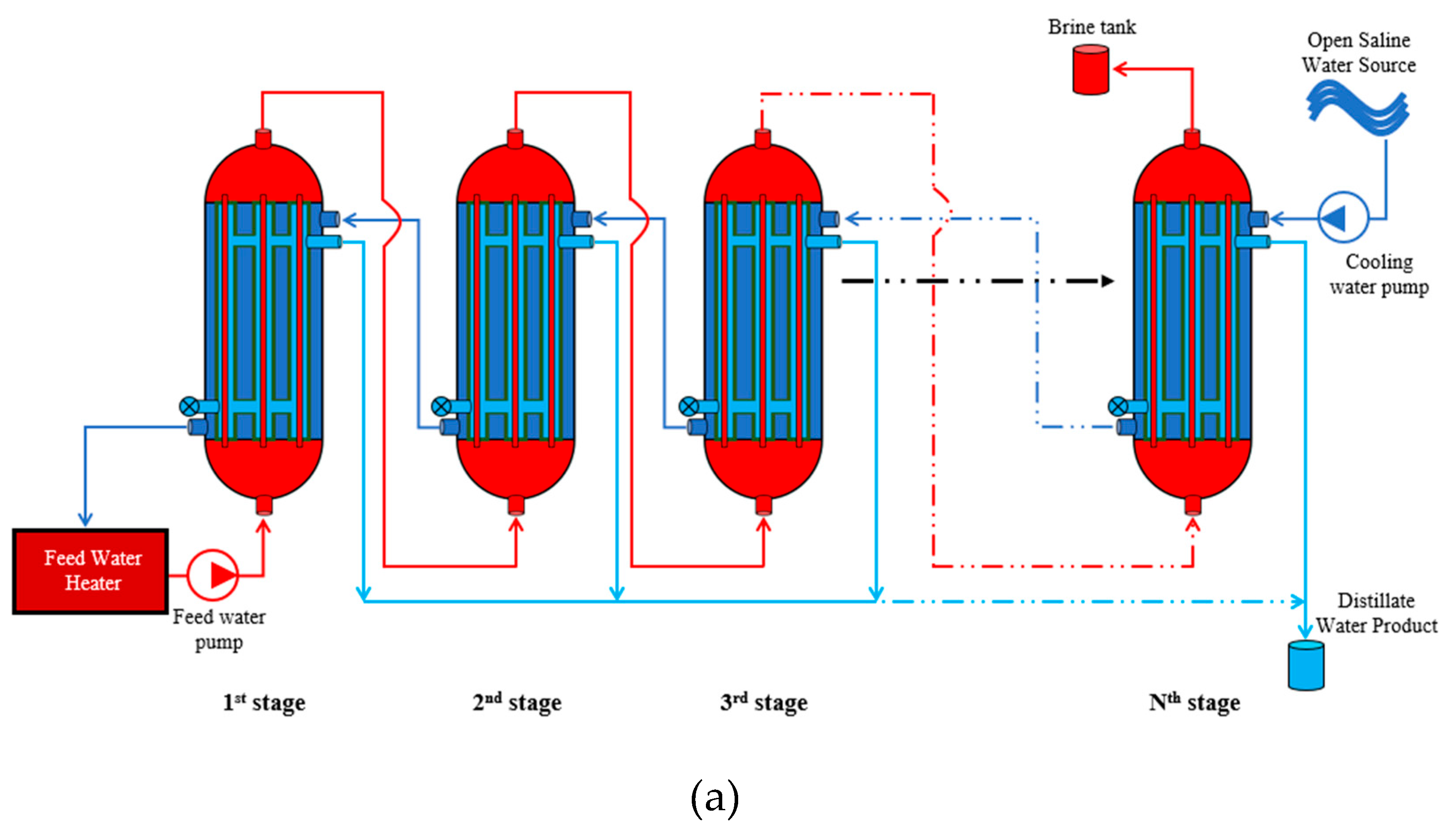

Figure 2.

Schematic diagrams for the configurations of multistage HF-WGMD modules with (a) stagnant WG and (b) circulating WG.

Figure 2.

Schematic diagrams for the configurations of multistage HF-WGMD modules with (a) stagnant WG and (b) circulating WG.

Figure 3.

Schematic diagrams of the simulated domains of HF-WGMD modules; (a) stagnant WG and (b) circulating WG.

Figure 3.

Schematic diagrams of the simulated domains of HF-WGMD modules; (a) stagnant WG and (b) circulating WG.

Figure 4.

The grid independence study of the CFD simulation model for a circulating () HF-WGMD module of , and .

Figure 4.

The grid independence study of the CFD simulation model for a circulating () HF-WGMD module of , and .

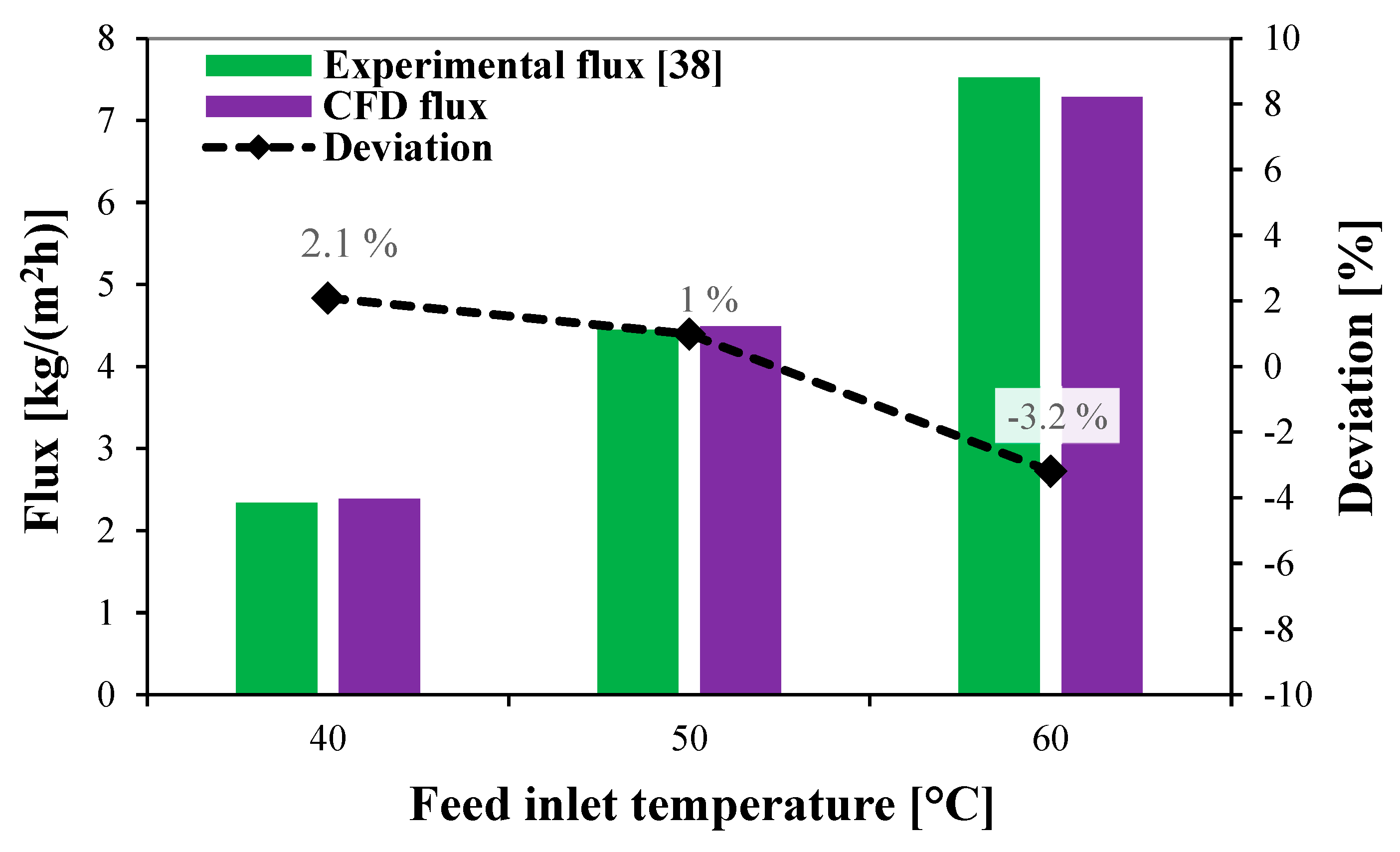

Figure 5.

Experimental validation of the CFD simulation model.

Figure 5.

Experimental validation of the CFD simulation model.

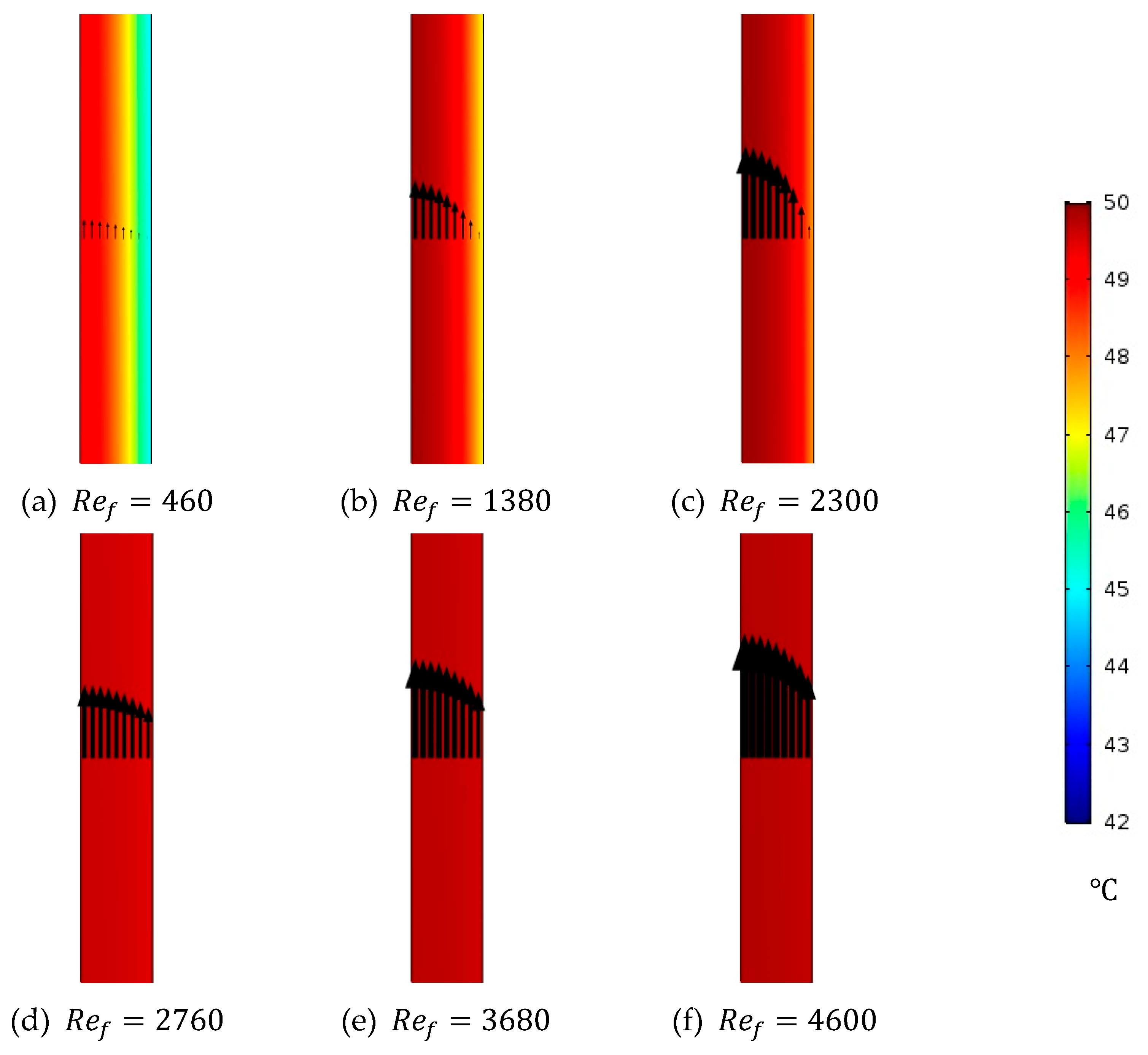

Figure 6.

Temperature distribution of the feed channel of the stagnant HF-WGMD module for different feed Reynolds numbers at and .

Figure 6.

Temperature distribution of the feed channel of the stagnant HF-WGMD module for different feed Reynolds numbers at and .

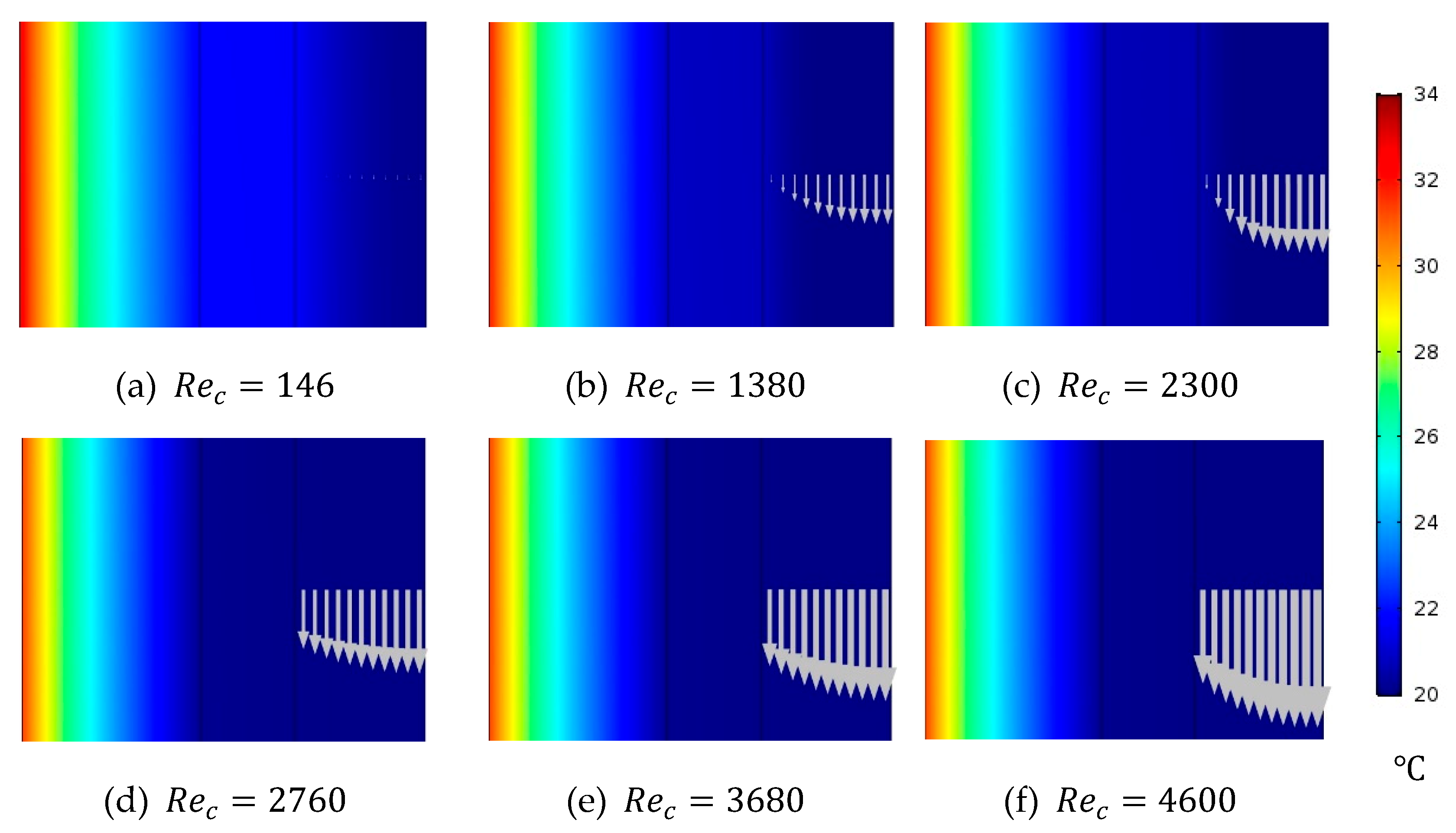

Figure 7.

Temperature distribution of WG, cooling tube and cooling water through the stagnant HF-WGMD module for different coolant Reynolds numbers at and .

Figure 7.

Temperature distribution of WG, cooling tube and cooling water through the stagnant HF-WGMD module for different coolant Reynolds numbers at and .

Figure 8.

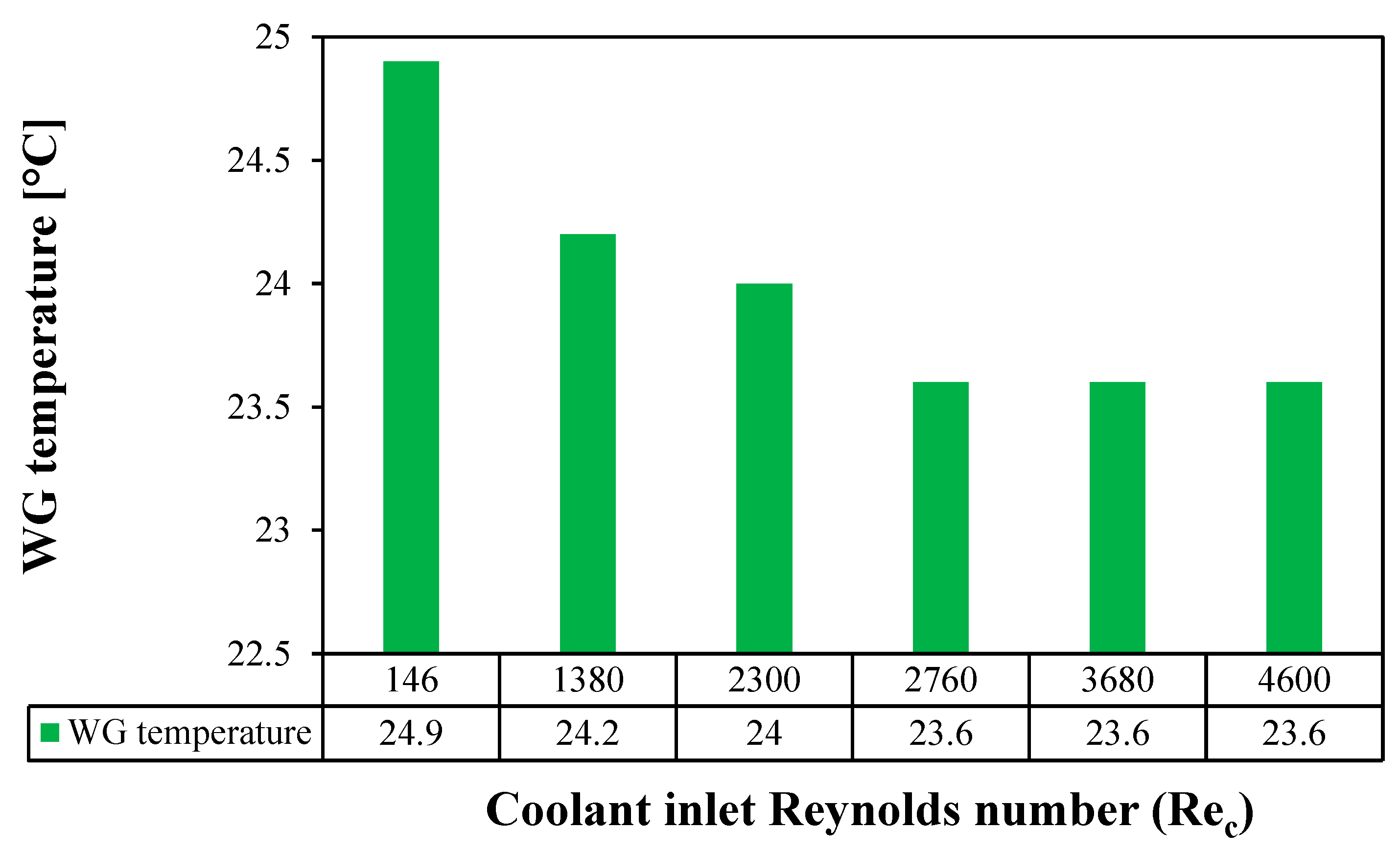

Average WG temperature of the stagnant HF-WGMD module versus coolant Reynolds number at and .

Figure 8.

Average WG temperature of the stagnant HF-WGMD module versus coolant Reynolds number at and .

Figure 9.

Temperature distribution of WG through the circulating HF-WGMD module for different WG circulation Reynolds numbers at , and .

Figure 9.

Temperature distribution of WG through the circulating HF-WGMD module for different WG circulation Reynolds numbers at , and .

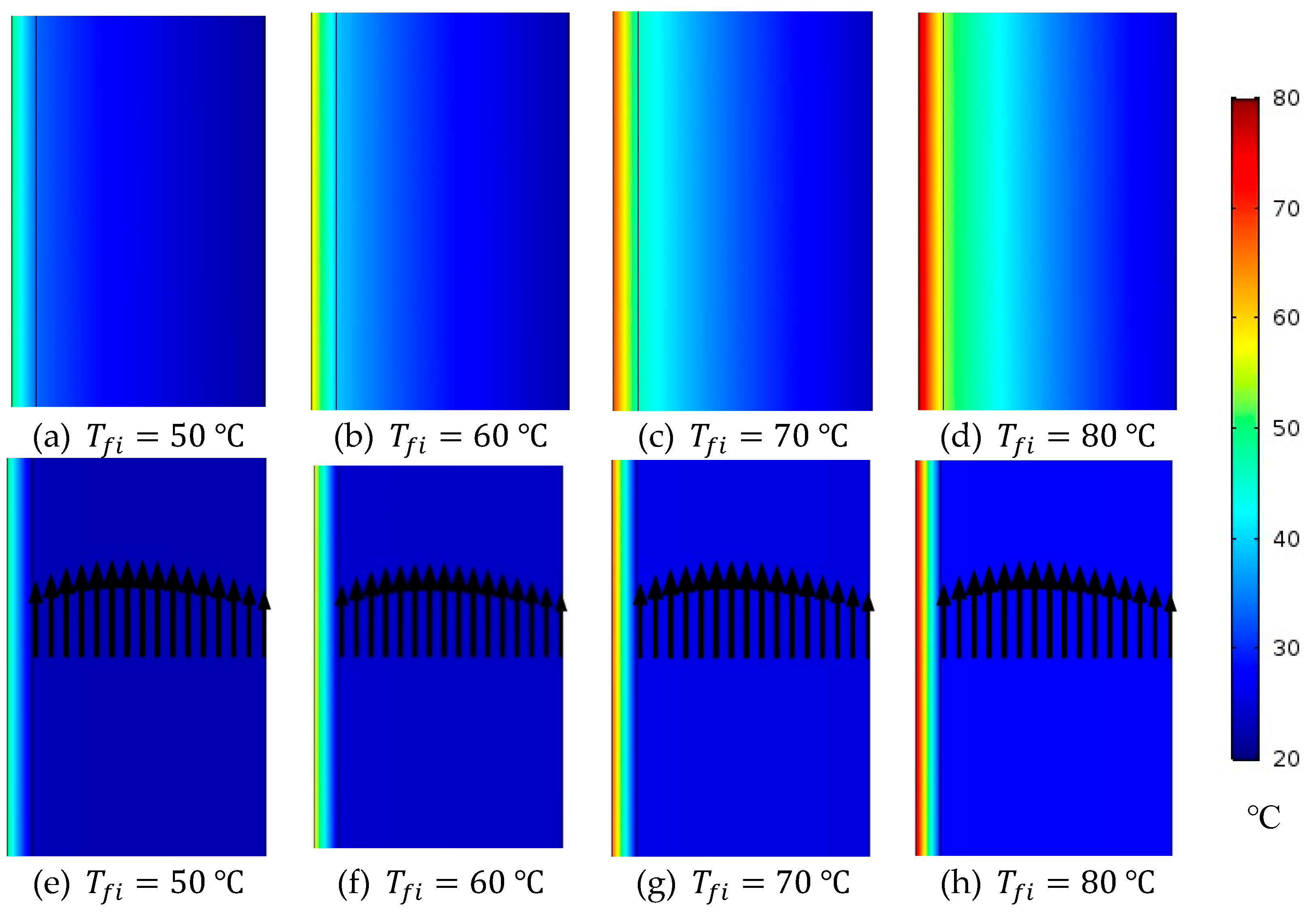

Figure 10.

Temperature distribution of membrane and WG at different feed inlet temperatures through; (a), (b), (c) and (d) stagnant and (e), (f), (g) and (h) circulating () HF-WGMD modules at and .

Figure 10.

Temperature distribution of membrane and WG at different feed inlet temperatures through; (a), (b), (c) and (d) stagnant and (e), (f), (g) and (h) circulating () HF-WGMD modules at and .

Figure 11.

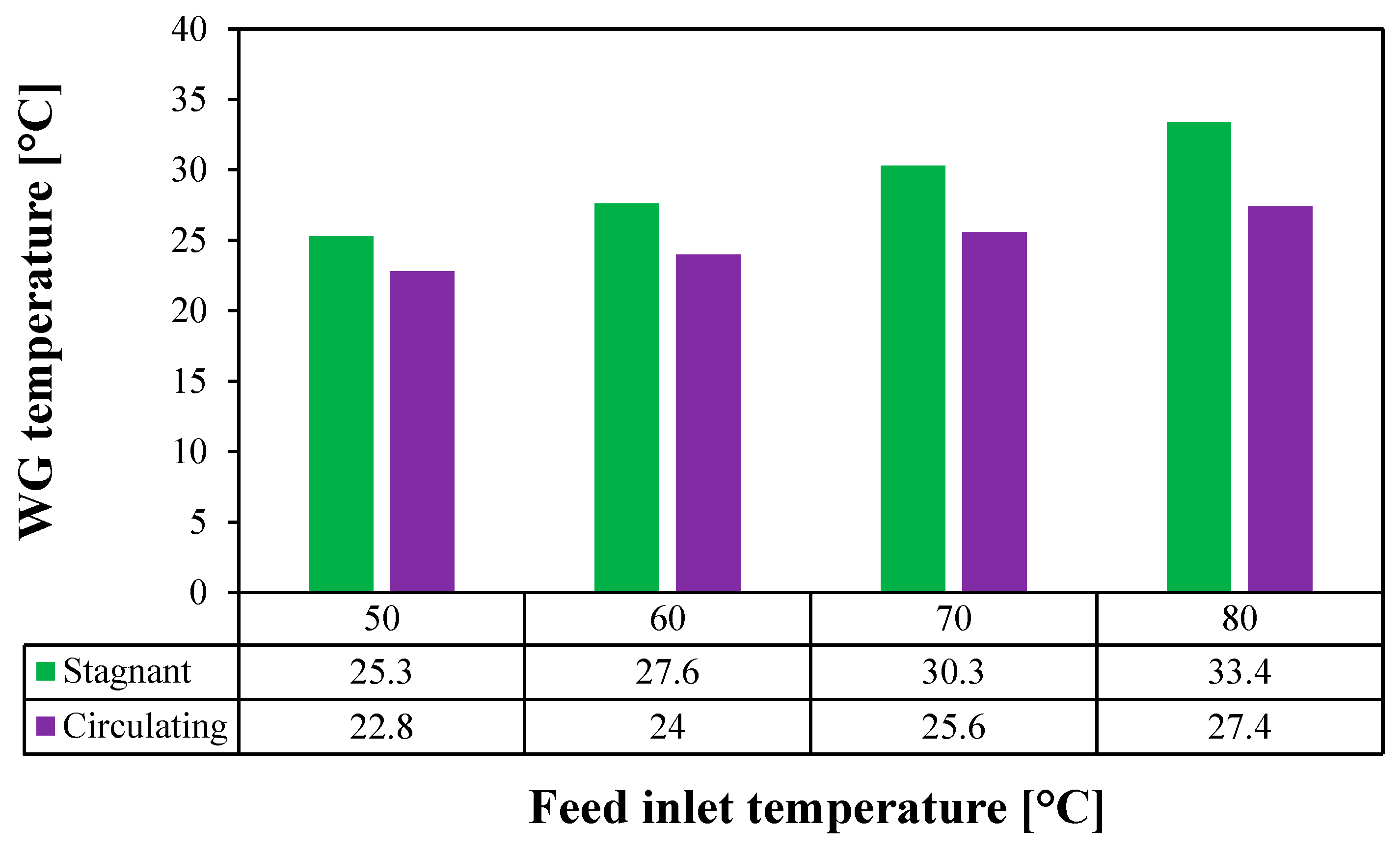

Average WG temperature of the stagnant and circulating () HF-WGMD modules versus feed inlet temperature at and .

Figure 11.

Average WG temperature of the stagnant and circulating () HF-WGMD modules versus feed inlet temperature at and .

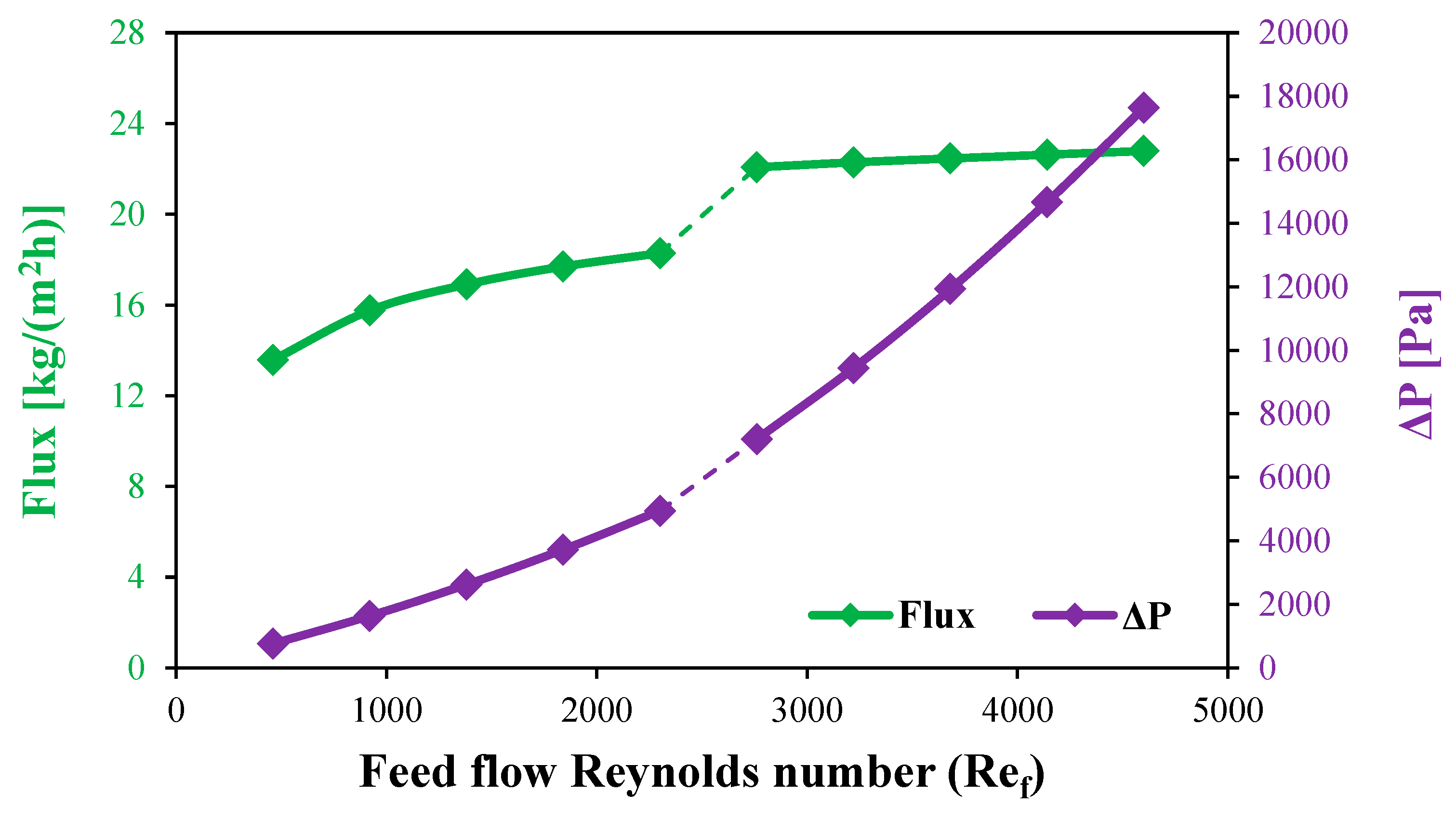

Figure 12.

Flux and feed water pressure drop for the stagnant HF-WGMD module versus feed Reynolds number at .

Figure 12.

Flux and feed water pressure drop for the stagnant HF-WGMD module versus feed Reynolds number at .

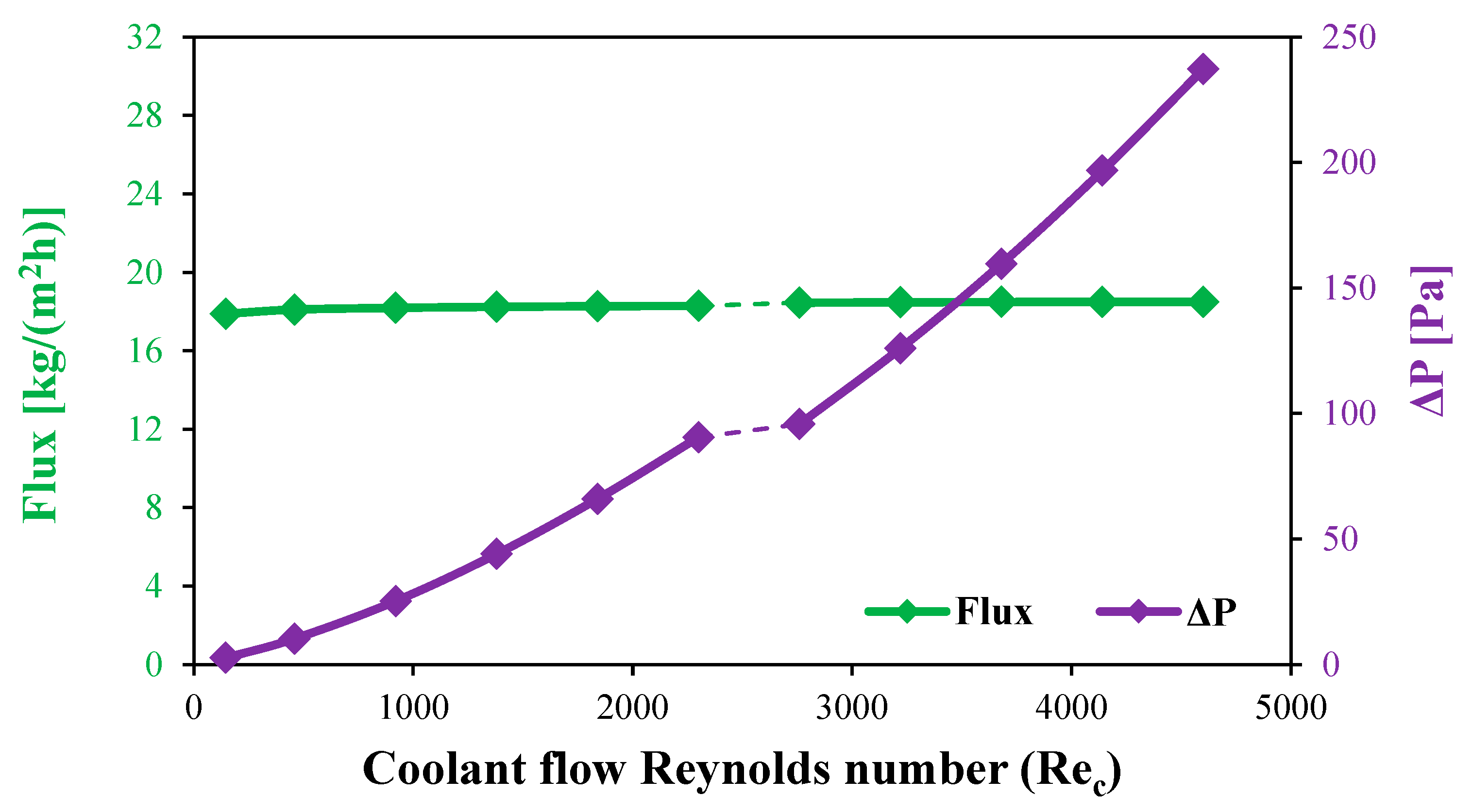

Figure 13.

Flux and cooling water pressure drop for the stagnant HF-WGMD module versus coolant Reynolds number at .

Figure 13.

Flux and cooling water pressure drop for the stagnant HF-WGMD module versus coolant Reynolds number at .

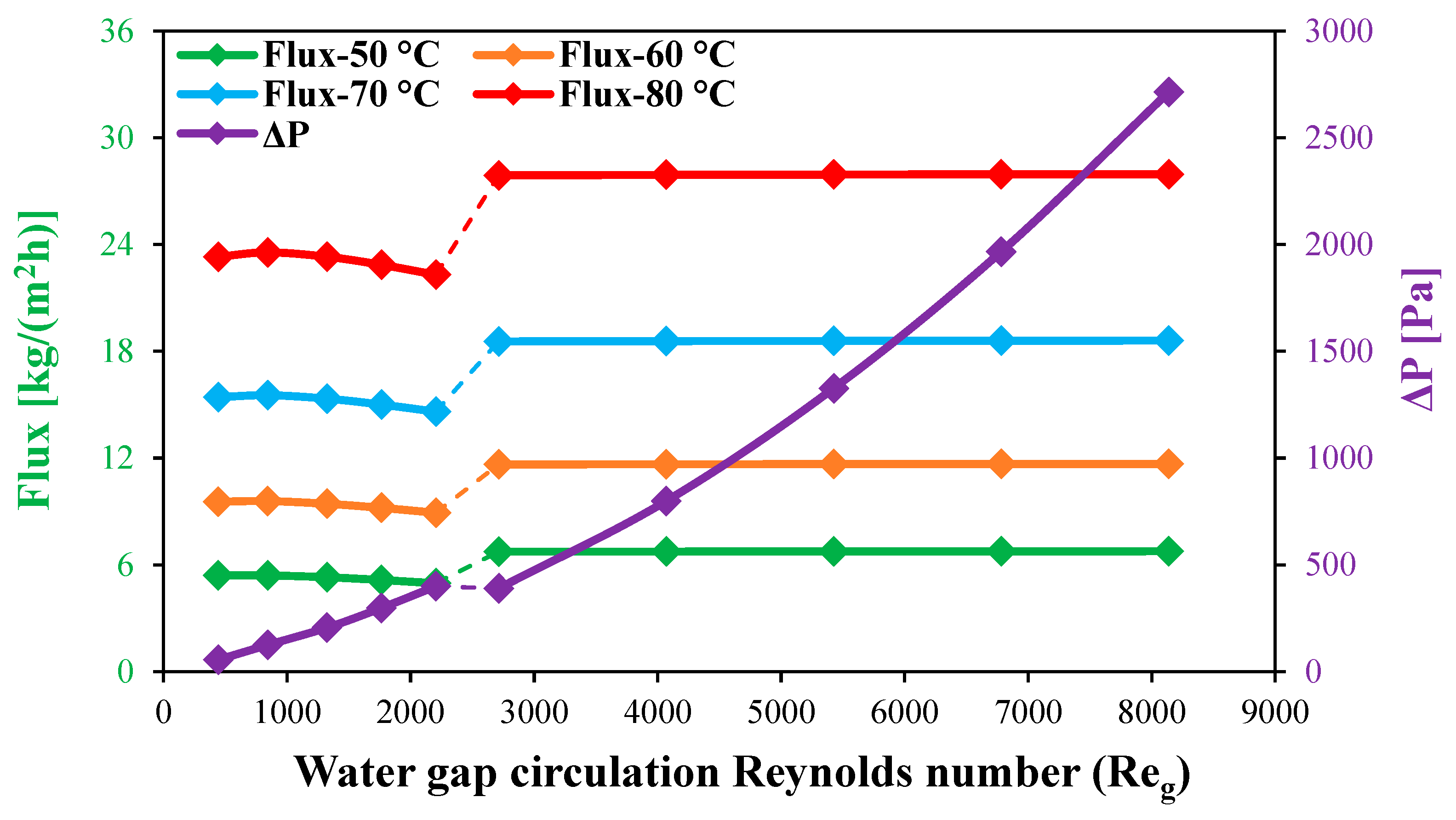

Figure 14.

Flux and WG pressure drop for the circulating HF-WGMD module versus WG circulation Reynolds number at , and different feed inlet temperatures.

Figure 14.

Flux and WG pressure drop for the circulating HF-WGMD module versus WG circulation Reynolds number at , and different feed inlet temperatures.

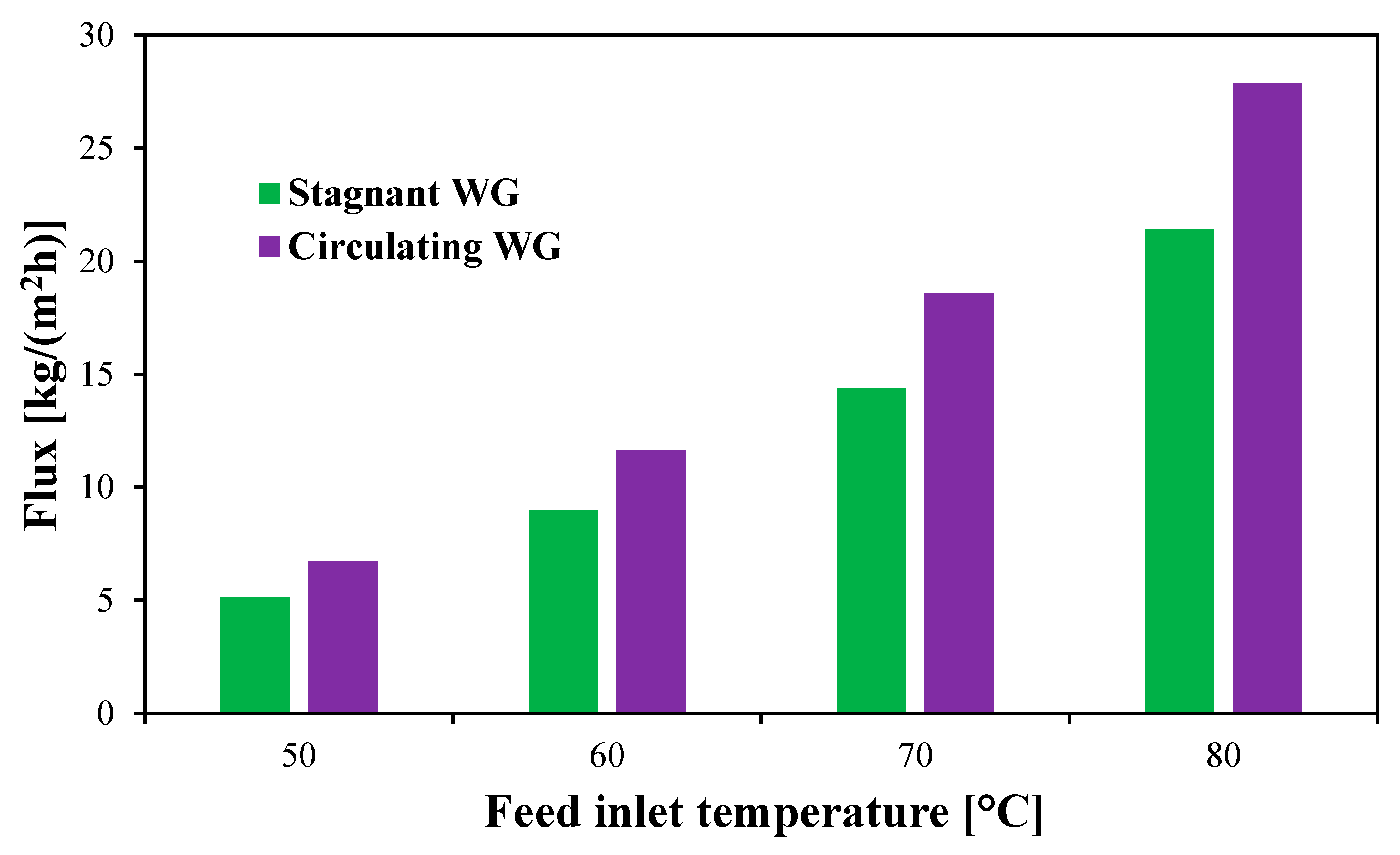

Figure 15.

Water product flux of the stagnant and circulating () HF-WGMD module versus feed inlet temperature at and .

Figure 15.

Water product flux of the stagnant and circulating () HF-WGMD module versus feed inlet temperature at and .

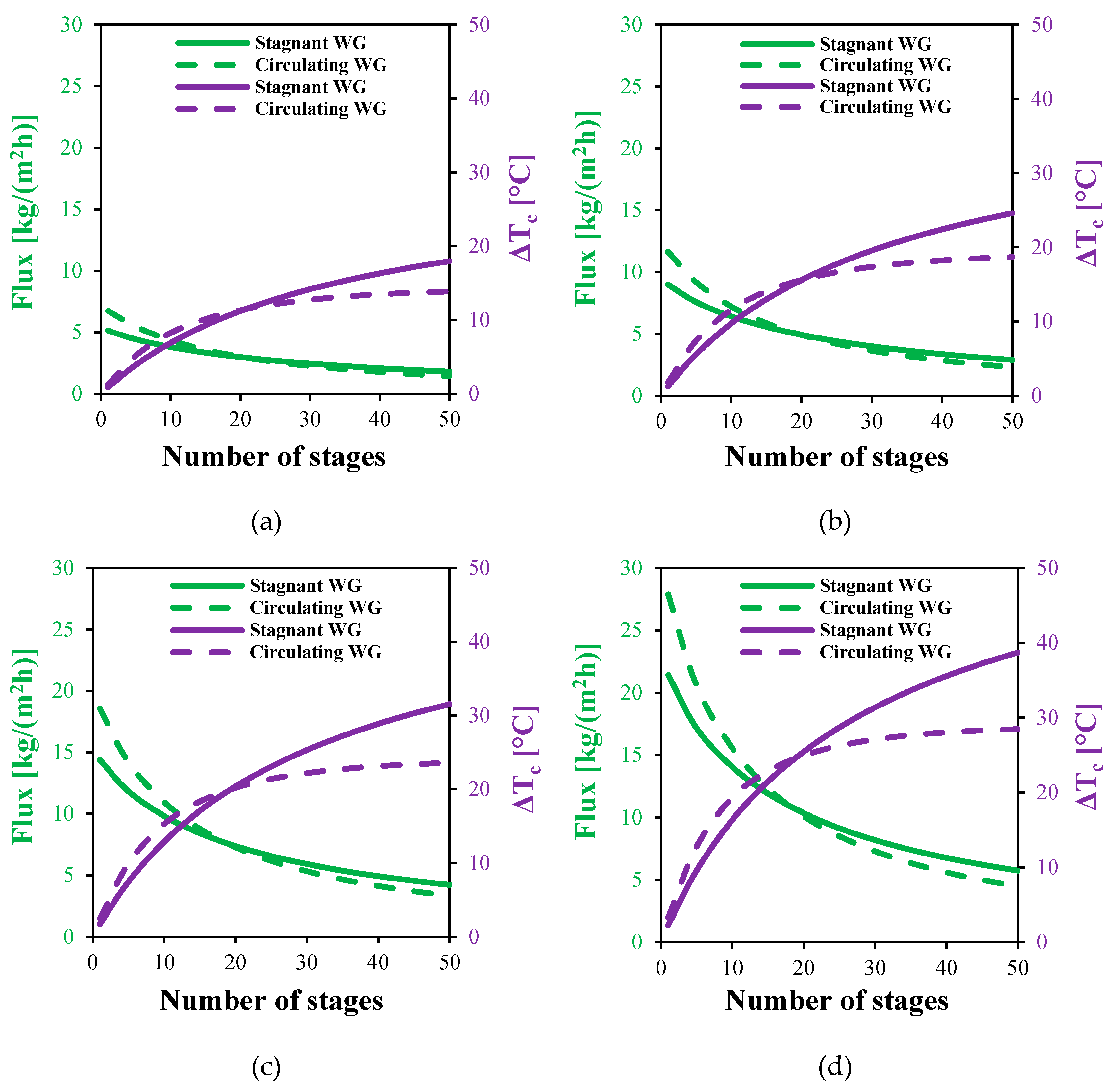

Figure 16.

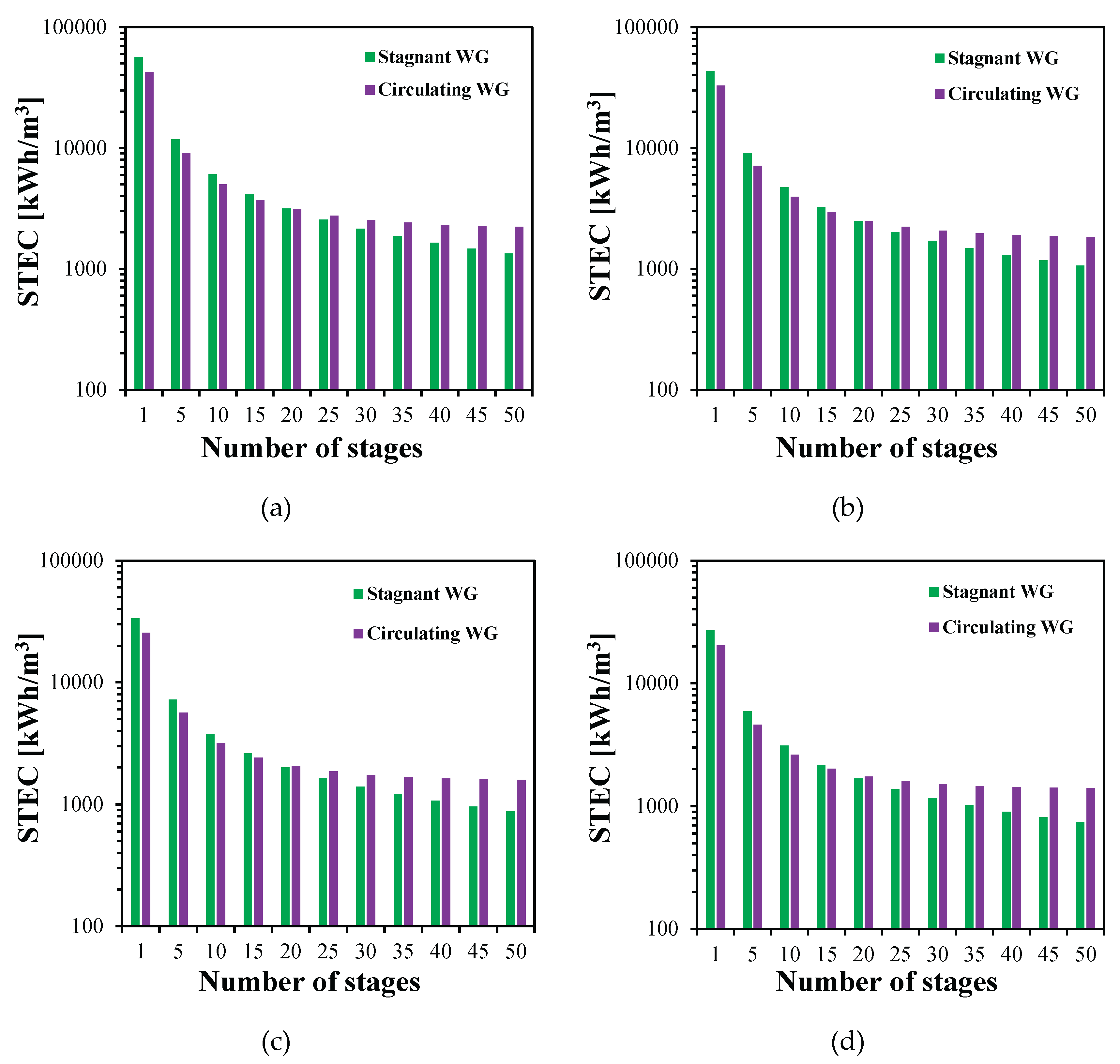

The effect of the number of stages on the flux and cooling water temperature rise of MS-HF-WGMD systems at different feed inlet temperatures of (a) 50 °C, (b) 60 °C, (c) 70 °C and (d) 80 °C.

Figure 16.

The effect of the number of stages on the flux and cooling water temperature rise of MS-HF-WGMD systems at different feed inlet temperatures of (a) 50 °C, (b) 60 °C, (c) 70 °C and (d) 80 °C.

Figure 17.

The effect of the number of stages on the STEC of MS-HF-WGMD systems at different feed inlet temperatures of (a) 50 °C, (b) 60 °C, (c) 70 °C and (d) 80 °C.

Figure 17.

The effect of the number of stages on the STEC of MS-HF-WGMD systems at different feed inlet temperatures of (a) 50 °C, (b) 60 °C, (c) 70 °C and (d) 80 °C.

Table 1.

HF-WGMD module specifications.

Table 1.

HF-WGMD module specifications.

| Parameter |

Symbol |

Value |

Unit |

| Membrane inner radius |

|

0.4 |

mm |

| Membrane outer radius |

|

0.58 |

mm |

| Cooling tube inner radius |

|

2.28 |

mm |

| Cooling tube outer radius |

|

3.18 |

mm |

| Coolant channel radius |

|

2.21 |

mm |

| Module effective length |

|

100 |

mm |

| Feed inlet salinity |

|

35000 |

ppm |

| Feed water thermal conductivity |

|

0.64 |

W/(m K) |

| Membrane thermal conductivity |

|

0.07 |

W/(m K) |

| Membrane porosity |

|

82 |

% |

| Membrane pore tortuosity |

|

1.7 |

- |

| Membrane pore diameter |

|

0.16 |

μm |

| Water gap salinity |

|

0.0 |

ppm |

| Cooling tube thermal conductivity |

|

15 |

W/(m K) |

| Vapor molecular mass (H2O) |

|

18 |

g/mol |

| Salt molecular mass (NaCl) |

|

58.5 |

g/mol |

Table 2.

Boundary conditions for the mass transport equations.

Table 2.

Boundary conditions for the mass transport equations.

| Domain |

Position |

Boundary condition |

| Feed |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Membrane |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Table 3.

Boundary conditions for the momentum transport equations.

Table 3.

Boundary conditions for the momentum transport equations.

| Domain |

Position |

Boundary condition |

| Feed |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Circulating WG |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Cooling channel |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Table 4.

Boundary conditions for the mass transport equations.

Table 4.

Boundary conditions for the mass transport equations.

| Domain |

Position |

Boundary condition |

| Feed |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Membrane |

|

|

|

|

| Stagnant WG |

|

|

|

|

| Circulating WG |

&

|

Periodic |

| Cooling tube |

|

|

|

|

| Cooling channel |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Table 5.

Average temperature and concentration at feed-membrane interface of stagnant HF-WGMD module for different feed Reynolds numbers at and .

Table 5.

Average temperature and concentration at feed-membrane interface of stagnant HF-WGMD module for different feed Reynolds numbers at and .

| |

Feed Inlet Reynolds Numbers |

| 460 |

1380 |

2300 |

2760 |

3680 |

4600 |

| Temperature [°C] |

45.1 |

47.2 |

47.9 |

49.5 |

49.6 |

49.7 |

| Concentration [mol/m3] |

3.53 |

3.9 |

4.04 |

4.38 |

4.42 |

4.44 |

Table 6.

Average temperature and concentration at membrane-WG interface of circulating HF-WGMD module for different WG circulation Reynolds numbers at , and .

Table 6.

Average temperature and concentration at membrane-WG interface of circulating HF-WGMD module for different WG circulation Reynolds numbers at , and .

| |

WG Inlet Reynolds Numbers |

| 441 |

1322 |

2204 |

2712 |

5424 |

8136 |

| Temperature [°C] |

31.9 |

32.4 |

34.1 |

23 |

22.9 |

22.9 |

| Concentration [mol/m3] |

1.88 |

1.93 |

2.11 |

1.15 |

1.14 |

1.14 |