1. Introduction

The prevalence of food allergies varies globally, with estimates ranging from 8% to 10% in developed countries (1). In Saudi Arabia, the prevalence averaged around 15.2%, with significant regional variability (2). Anaphylaxis is an immediate, life-threatening, and immune-mediated reaction to an allergic trigger (3). As such, prompt recognition and treatment are required to prevent severe outcomes, highlighting the importance of awareness and education regarding food allergies.

A study from Spain found that 10-18% of food-related allergic reactions occurred while children were at school, highlighting the importance of school readiness for such events (4). A school nurse's presence differs from the standard practice in Saudi Arabia; however, recently, appointing a teacher as a health liaison has become mandatory for all schools at all educational stages. Multiple studies have highlighted the critical deficiency in training and resources available to the school's staff, who have daily contact with children at risk of experiencing an allergic reaction, emphasising the need for comprehensive training programs to equip them with the necessary skills to manage allergic reactions effectively (4). A study from Saudi Arabia raised a major red flag that most school staff in one region lacked the simple and basic knowledge of food allergy, recognising symptoms, and managing anaphylaxis (5). One essential area where school staff demonstrated a significant lack of knowledge and skills was recognising the symptoms and signs of severe food-induced allergic reactions, as well as when and how to use adrenaline auto-injectors (4, 5). This gap in training not only puts students at risk but also creates a sense of anxiety among parents, who may feel their children's safety is compromised while at school.

Most of the previous studies showed the level of awareness of anaphylaxis in Saudi Arabia, but they failed to provide a real solution. Simulation is an excellent educational tool, enabling educators to expose trainees to real-world scenarios without compromising patient safety (6). This tool has shown great success in medical education for healthcare practitioners (6). Studies have demonstrated that case simulations are more effective than standard lectures for emergency situational training (7-9). It can be extrapolated for use by school staff as necessary. In this study, we utilised simulation-based training to evaluate the knowledge and skills of school staff in recognising the symptoms and signs of anaphylaxis and its management before and after simulation. We also assess attitudes toward guidelines and protocols in schools for managing severe allergic reactions. This approach is unique in Saudi Arabian schools, and we aim to measure the gaps in knowledge and skills related to food allergy and the role of simulation-based training in closing these gaps.

2. Materials and Methods:

2.1. Participants:

This study utilised a simulation-based education approach focusing on a case scenario conducted in elementary schools in Rabigh. This study was designed as a quasi-experimental pre-post intervention to evaluate changes in knowledge and attitudes toward food allergy and anaphylaxis among elementary school teachers following a simulation-based educational intervention. The participants included teachers and staff from six randomly selected elementary schools (both male and female) in Rabigh. The sample size for this study was determined to be

120 individuals using Raosoft, Inc. (Seattle, WA, USA) (

http://www.raosoft.com/samplesize.html) (accessed June 2024), with 95% confidence and a 5% margin of error. The inclusion criteria included elementary schools in Rabigh city and its surrounding villages. Special needs schools were excluded.

2.2. Questionnaire Design:

Pre- and post-simulation knowledge and attitude evaluations were conducted using pre- and post-questionnaires (10, 11). These questionnaires were previously published and validated, and were used in combination to assess knowledge (10) and attitude (11). We modified certain elements to align with the aims and population of our local study. The questionnaire assessed knowledge and attitude in the following categories:

a) It is essential to have guidelines and protocols in place at school for managing severe allergic reactions.

b) Identification of anaphylaxis through recognition of signs and symptoms.

c) Immediate action and management of the case.

This structured approach ensured a comprehensive evaluation of participants' knowledge and practical skills in handling anaphylaxis cases within school settings.

2.3. Simulation

To enhance awareness and readiness for managing critical school situations, the hybrid simulation for teacher education combines video-based scenarios with a task trainer. The program includes a structured debriefing session that encourages participants to reflect on their responses, discuss best practices, and reinforce theoretical knowledge, all presented through the video component. Realistic scenarios include a student exhibiting symptoms of anaphylactic shock, such as coughing, wheezing, and signs of hypoxia, followed by the appropriate actions teachers should take. Additionally, a Jext trainer is utilised to simulate a patient and demonstrate the use of an adrenaline auto-injector as a part-task trainer for procedural training. This setup allows participants to practice administering an epinephrine injection in a controlled, hands-on environment. By bridging theory and practical experience, this simulation design promotes competence and confidence in identifying and managing emergencies in real-life situations.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Sociodemographic data about participants and scores from the questionnaires were summarised. Continuous variables were reported using means and standard deviations, medians, and interquartile ranges. Summary of categorical variables was reported as frequencies and percentages. The Shapiro-Wilk test was used to assess the normality of the data, with comparisons made between pretest and post-test scores. Scores were unpaired and not normally distributed (p < 0.05). The Wilcoxon signed-rank test was conducted to analyse the differences between the before and after groups. The Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare the differences between genders. The Fisher Exact test was used to compare the knowledge before and after the simulation. Statistical tests were performed using Minitab statistical software version 22 and IBM SPSS Statistics version 26. The questionnaire assessing attitudes toward the guidelines and protocols in school for managing severe allergic reactions used the following response scale: 1 = Strongly Agree, 2 = Agree, 3 = Neutral, 4 = Disagree, and 5 = Strongly Disagree. The total score was calculated by summing the responses to all 10 questions, with a maximum possible score of 50 and a minimum of 10.

2.5. Ethical Approval

The Research Ethics Committee at King Abdulaziz University, Unit of Biomedical Ethics, with reference number 240-25, recommended granting permission to conduct the project on 22 October 2024. The Research Ethics Committee (REC) is based on the Good Clinical Practice (GCP) Guidelines. We conducted this investigation in accordance with the ethical criteria outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki.

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics:

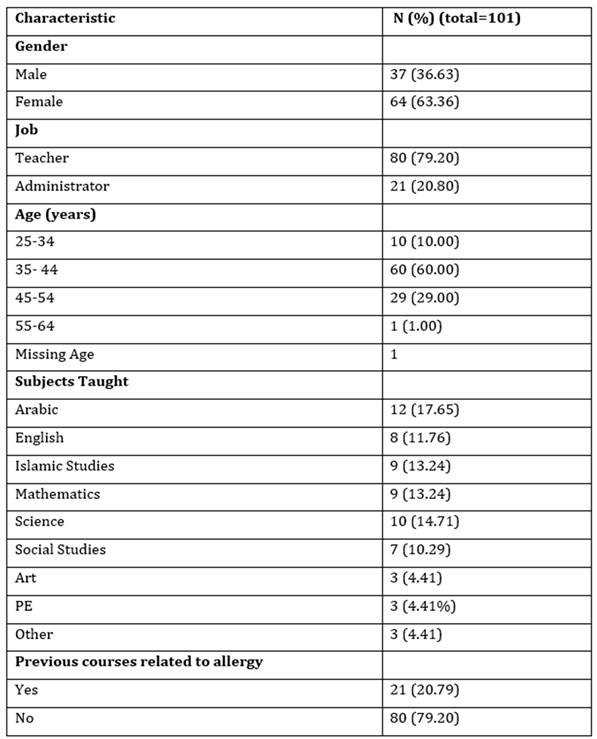

A total of 101 participants completed the pre-test questionnaire. However, 4 participants did not complete the post-test due to reasons such as loss to follow-up or non-response, resulting in a total of 97 participants included in the post-test analysis. The demographic and professional characteristics of the participants are summarised in this study. Male participants accounted for 37 (36.63%) of the sample, while females comprised 64 (63.36%). Participants were grouped into six age categories. Most participants were aged 35–44 years (60 participants; 60.00%) and 45–54 years (29 participants; 29.00%). The majority of participants were teachers (80; 79.20%), followed by administrators (21; 20.80%). A subset of participants (N = 68) provided information on the subjects they taught. The highest proportion of participants taught Arabic (12; 17.65%), followed by science (10; 14.71%), Mathematics (9; 13.24%), and Islamic Studies (9; 13.24%). Regarding previous courses related to allergies and epinephrine auto-injectors, 21 participants (20.79%) had prior training, while the majority (80; 79.20%) had none. Additionally, 63 participants (61.17%) reported having general information about allergies, while 40 (38.83%) did not. Among those with general information (N = 67), the most common source was reading (31 respondents; 46.27%). Other sources included family (17 respondents; 25.37%) and friends (10 respondents; 14.93%). A small proportion of respondents (22; 21.78%) reported having used the epinephrine autoinjector before, whereas the majority (79; 78.22%) indicated they had never used it.

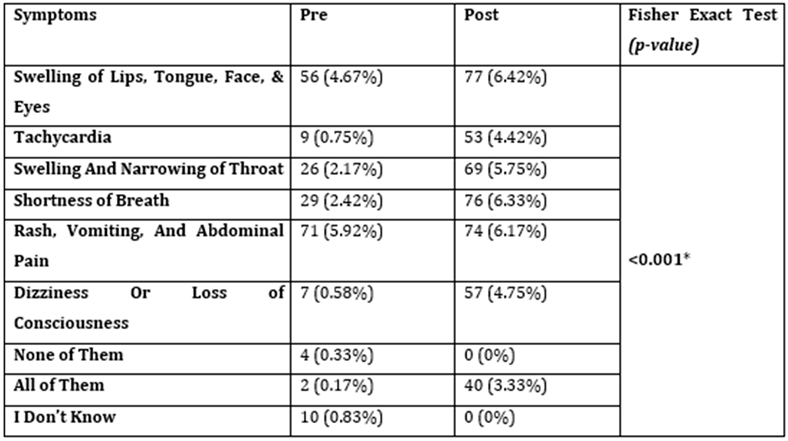

3.2. Identification of Anaphylaxis Through Recognition of Signs and Symptoms:

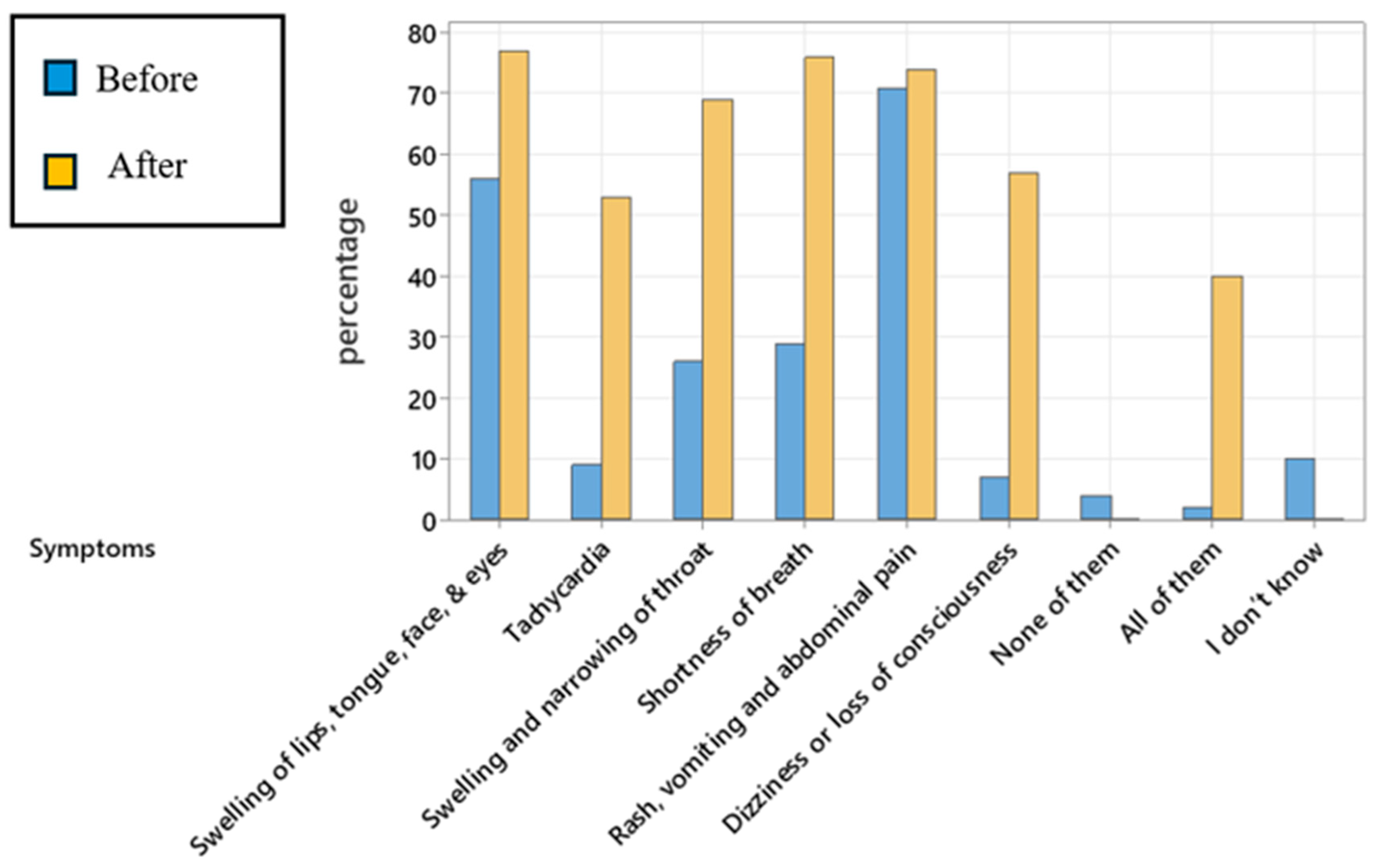

The comparison of knowledge of symptoms before and after the simulation intervention revealed significant changes in understanding of several symptoms. The Fisher Exact test showed a statistically significant increase in the recognition of symptoms post-intervention for swelling of the lips, tongue, face, and eyes (p < 0.001), indicating that participants were more able to identify this symptom after the intervention. Other symptoms, including tachycardia, swelling and narrowing of the throat, shortness of breath, and dizziness or loss of consciousness, also showed improvements in recognition after the intervention. The response categories "None of them" and "I don’t know" were both significantly reduced post-intervention, with all respondents moving away from these answers.

3.3. Assessing Attitude Toward the Guidelines and Protocols in School for the Management of Severe Allergic Reactions

The results of the post-simulation questionnaire revealed a statistically significant change in attitude scores between the pre- and post-intervention periods. The pre-simulation attitude scores ranged from a minimum of 10 to a maximum of 29, with a median score of 12 (IQR: 10-17). After the simulation intervention, the scores ranged from 10 to 27, with a median score of 10 (IQR: 10-13). The significant difference in scores between the pre- and post-intervention periods (p-value = 0.001) was confirmed using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test.

In detail, participants expressed stronger agreement on the importance of implementing measures for allergy preparedness and management after the simulation. The proportion of participants who "strongly agree" on key aspects, such as facilitating direct communication with emergency services (76.2% pre vs. 93.0% post) and defining staff roles in handling emergencies (72.3% pre vs. 80.2% post), increased markedly. The agreement on the need for special supervision during mealtimes (63.4% pre vs. 74.3% post) and rules banning food sharing (61.4% pre vs. 80.2% post) also showed significant improvement. Measures such as banning nuts in schools (58.4% pre vs. 80.2% post) and providing supervision on school buses (58.4% pre vs. 76.2% post) showed notable shifts toward stronger support (Supplementary materials,

Table S1).

In addition, self-assessed knowledge on a 10-point scale also improved significantly, with the mean knowledge score increasing from 4.46 (pre-intervention) to 8.21 (post-intervention) (p <0.001; 95% CI (-5, -3)), indicating a statistically significant improvement in knowledge scores following the intervention. The standard deviation decreased slightly from 2.38 (pre) to 2.18 (post), suggesting more consistent responses after the intervention and potentially reflecting greater confidence among participants.

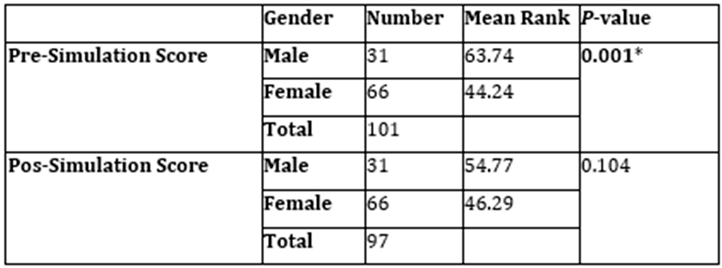

The gender-based comparison of attitude scores before and after the simulation intervention showed a significant difference in pre-simulation scores. The Mann-Whitney U test revealed that male participants had a higher mean rank (63.74) compared to female participants (44.24), with a p-value of 0.001, indicating a statistically significant difference in pre-intervention attitude scores between genders. However, after the intervention, there was no significant difference in post-simulation scores between males and females. The mean ranks were 54.77 for males and 46.29 for females, with a p-value of 0.104. This suggests that the simulation intervention resulted in similar improvements in attitude across both genders, as no significant difference was observed in post-intervention scores.

3.4. Readiness to Use Epinephrine Auto-Injector:

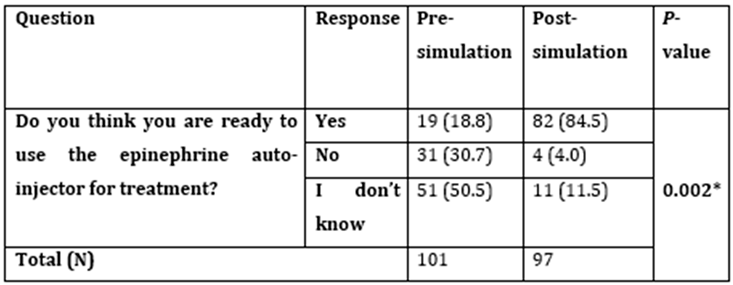

The proportion of participants who reported being ready to use an epinephrine auto-injector increased substantially from 18.8% before the intervention to 84.5% after the intervention (p = 0.002). Conversely, the percentage of participants who were not ready dropped sharply from 30.7% to 4.0%, and those unsure about their readiness decreased from 50.5% to 11.5%. The results, determined using Fisher's Exact Test, underscore the effectiveness of the simulation in enhancing participants’ confidence and preparedness to manage anaphylactic emergencies with appropriate tools.

4. Discussion:

Several studies in Saudi Arabia have measured the knowledge of food allergy and anaphylaxis among schoolteachers. These studies revealed a significant lack of basic knowledge about food allergy, recognition of anaphylactic symptoms and signs, and the immediate action required for allergic reactions, including the use of an epinephrine auto-injector (5, 12-15). The recommendations from these studies included providing training programs for schools and educational campaigns. In this study, we provided an educational simulation intervention and assessed teachers’ knowledge and attitudes toward food allergy and anaphylaxis in primary schools before and after the simulation. The assessment focused on three aspects: identification of anaphylaxis through recognition of signs and symptoms, attitude toward the guidelines and protocols in schools for managing severe allergic reactions, and participants' readiness to use an epinephrine auto-injector. The findings demonstrated that the simulation intervention was effective in improving participants' knowledge of the symptoms and signs, especially critical ones such as swelling of the lips, tongue, face, and eyes, as well as shortness of breath (p < 0.001), which are key indicators of anaphylaxis. Interestingly, the response categories "None of them" and "I don’t know" were both significantly reduced post-intervention (p < 0.001), with all respondents moving away from these answers, suggesting again an increased awareness and understanding of the symptoms associated with the condition. A study in Houston, USA, measured the knowledge of school personnel before and after a 1-hour educational session on food allergies. The study revealed that the training significantly improved teachers' knowledge and attitudes toward food allergies, particularly in the early recognition of anaphylaxis and the use of epinephrine auto-injectors, highlighting the importance of educational interventions in enhancing preparedness for allergic reactions in schools (16).

In the current study, there was a statistically significant improvement in self-assessed knowledge scores following the simulation on a 10-point scale, with the mean knowledge score increasing from 4.46 (pre-intervention) to 8.21 (post-intervention) (p <0.001; 95% CI (-5, -3)). Additionally, a significant gender-based difference was observed in pre-simulation attitudes. However, the simulation appeared to equally benefit both male and female participants, resulting in similar post-intervention outcomes. The attitude toward the guidelines and protocols in schools for managing severe allergic reactions has improved. For example, the agreement on the need for special supervision during mealtimes, rules banning food sharing and the use of nuts, and providing supervision on school buses showed significant shifts toward more substantial support. A previous study evaluating the effect of a single educational session has been successful in enhancing preschool teachers’ self-rated confidence, participant knowledge, and attitude toward anaphylactic emergencies, even after 4- to 12-week follow-ups (17).

Simulation-based education is a well-established teaching method for preparing health workers and medical students to comprehensively understand and manage clinical emergencies (6, 18, 19). To our knowledge, it is uncommon to use a case simulation in educating teachers or the public. A study showed that the in-situ simulation improved team confidence and management of anaphylaxis in the allergy clinic among nurses, allergy-immunology fellows and immunologists (19). A similar study conducted on nurses from different units reported an improvement in the diagnosis and management of anaphylaxis through the detection of signs and symptoms and the rapid use of an epinephrine auto-injector (20). These results underline the effectiveness of the simulation intervention in enhancing participants’ awareness and proactive attitudes toward anaphylaxis management in educational settings.

The simulation resulted in a significant improvement in participants’ confidence in using an epinephrine auto-injector, increasing readiness from 18.8% pre-intervention to 84.5% post-intervention (p = 0.002). Uncertainty and lack of preparedness decreased considerably among school staff after the simulation. A study conducted in Japan, involving teachers, school nurses, and caregivers working with children who were prescribed epinephrine auto-injectors, demonstrated that practical training significantly increased their confidence and self-efficacy in managing allergic emergencies (21). Many studies from different countries have also identified significant deficiencies in school readiness to treat students with anaphylaxis, including the initiation of management, the availability of epinephrine in schools, and the training of staff to administer epinephrine (11, 22-24). The inadequate handling of epinephrine auto-injectors in children with anaphylaxis suggests that more effort should be devoted to educating school staff about the proper use of epinephrine, as simulation-based training could be a practical approach to enhance their practice.

This study has a few limitations. The study was conducted in a single region with a limited number of participants from six schools. Applying this simulation-based training to a larger number of participants and schools will provide a better overview. Additionally, certain aspects of self-reported data may introduce potential bias or lead to over- or underestimation of knowledge levels and attitudes. Despite these limitations, the study’s findings were consistent with the existing literature in both school and clinical settings. Moreover, the simulation implemented has overall increased understanding regarding anaphylaxis, shifting attitude positively toward allergy policies, and improving staff readiness to use epinephrine.

5. Conclusion

In conclusion, while schools have taken steps in managing allergy risks, there remains a need for the broader implementation of policies and practices that prioritise the safety of all students, particularly those with food allergies or anaphylaxis. Further education and training for school staff, along with more robust policies on supervision and food safety, could further enhance the safety and preparedness of schools in the event of allergy emergencies. Simulation-based learning is a suitable choice, as it has a positive impact on the detection and management of food allergy and anaphylaxis within the school environment.

Table Legend:

Table 1. Participant Characteristics.. Comparison of knowledge of symptoms before and after the simulation intervention.

Table 2. Gender based Comparison of Attitude toward the Anaphylaxis Guidelines and Protocols before and after the Simulation Intervention using Post-Simulation Questionnaires.

Table 3. Readiness to use an epinephrine auto-injector.

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics.

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics.

Table 4.

Comparison of knowledge of symptoms before and after the simulation intervention.

Table 4.

Comparison of knowledge of symptoms before and after the simulation intervention.

Fisher Exact test, p-value<0.05* is considered statistically significant. The value listed in bold indicates statistical significance. Data are displayed as numbers (%).

Table 5.

Gender based Comparison of Attitude toward the Anaphylaxis Guidelines and Protocols before and after the Simulation Intervention using Post-Simulation Questionnaires.

Table 5.

Gender based Comparison of Attitude toward the Anaphylaxis Guidelines and Protocols before and after the Simulation Intervention using Post-Simulation Questionnaires.

Mann-Whitney U test, p-value < 0.05* indicates statistical significance. The value listed in bold indicates statistical significance.

Table 6.

Readiness to use an epinephrine auto-injector.

Table 6.

Readiness to use an epinephrine auto-injector.

Fisher's Exact Test was used to determine the difference, including the confidence interval and p-value. p<0.05 is considered statistically significant. The value listed in bold indicates statistical significance.

Figure Legend:

Figure 1.

Comparison of recognised allergy symptoms before and after simulation.

Figure 1.

Comparison of recognised allergy symptoms before and after simulation.

Figure 2. Comparison of recognised allergy symptoms before and after simulation. This figure illustrates the percentage of participants identifying allergy symptoms before and after the simulation. The results show a significant increase in symptom recognition after the simulation (p < 0.001), with a notable decrease in the "None of them" and "I don't know" categories. The Fisher Exact test was used to compare the knowledge.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. More information will be provided upon request.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N,F.; methodology, N.F., M.H., M.D., S.H., and A.A.; software, N.F., M.D.; validation, N.F., M.H., M.D., S.H., and A.A; formal analysis, N.F.; investigation, N.F., M.H., M.D., S.H., and A.A; resources, N.F.; data curation, N.F., M.H., M.D., S.H., and A.A.; writing—original draft preparation, N.F., and S.H.; writing review and editing, N.F.; visualisation, N.F.; supervision, N.F.; project administration, M.H.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The Research Ethics Committee from the King Abdulaziz University, Unit of Biomedical Ethics, with reference number 240-25 on October 22, 2024, recommended granting permission to conduct the project. The Research Ethics Committee (REC) is based on the Good Clinical Practice (GCP) Guidelines. We conducted this investigation in accordance with the ethical principles outlined in the Helsinki Declaration.

Informed Consent Statement

Participants in this study provided their informed consent to participate. All collected data was kept completely confidential and used only for research purposes. Furthermore, the surveys contained no personal information or other ways of identification for the participants.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be provided upon request. For more information, contact the corresponding author, M.H.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Saudi Ministry of Education for facilitating contact with schools. We also acknowledge the principals of schools for promoting the required environment and facilitating data collection—special thanks to the medical students from Rabigh Medical College Who Volunteered For Awareness.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- Bartha I, Almulhem N, Santos AF. Feast for thought: A comprehensive review of food allergy 2021-2023. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2024;153(3):576-94. [CrossRef]

- Alibrahim I, AlSulami M, Alotaibi T, Alotaibi R, Bahareth E, Abulreish I, et al. Prevalence of Parent-Reported Food Allergies Among Children in Saudi Arabia. Nutrients. 2024;16(16). [CrossRef]

- Ercan H, Ozen A, Karatepe H, Berber M, Cengizlier R. Primary school teachers' knowledge about and attitudes toward anaphylaxis. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2012;23(5):428-32.

- Gonzalez-Mancebo E, Gandolfo-Cano MM, Trujillo-Trujillo MJ, Mohedano-Vicente E, Calso A, Juarez R, et al. Analysis of the effectiveness of training school personnel in the management of food allergy and anaphylaxis. Allergol Immunopathol (Madr). 2019;47(1):60-3.

- Gohal G. Food allergy knowledge and attitudes among school teachers in Jazan, Saudi Arabia. The Open Allergy Journal. 2018;9(1). [CrossRef]

- Barni S, Mori F, Giovannini M, de Luca M, Novembre E. In situ simulation in the management of anaphylaxis in a pediatric emergency department. Intern Emerg Med. 2019;14(1):127-32. [CrossRef]

- Maddry JK, Varney SM, Sessions D, Heard K, Thaxton RE, Ganem VJ, et al. A comparison of simulation-based education versus lecture-based instruction for toxicology training in emergency medicine residents. J Med Toxicol. 2014;10(4):364-8.

- Lighthall GK, Barr J. The use of clinical simulation systems to train critical care physicians. J Intensive Care Med. 2007;22(5):257-69. [CrossRef]

- Ten Eyck RP, Tews M, Ballester JM. Improved medical student satisfaction and test performance with a simulation-based emergency medicine curriculum: a randomised controlled trial. Ann Emerg Med. 2009;54(5):684-91.

- Aslan G, Savcı Mağol DD, Bakan ABS. An investigation of the effects of the education given to teachers on food allergy and anaphylaxis management self-efficacy and level of knowledge. Health Education Journal. 2024;83(6):577-86. [CrossRef]

- Raptis G, Perez-Botella M, Totterdell R, Gerasimidis K, Michaelis LJ. A survey of school's preparedness for managing anaphylaxis in pupils with food allergy. Eur J Pediatr. 2020;179(10):1537-45.

- Asiri KA, Mahmood SE, Alostath SA, Alshammari MD, Al Sayari TA, Ahmad A, et al. Knowledge and practices regarding anaphylaxis management in children and adolescents among teachers in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA). Science. 2021;90:23.4.

- Alsuhaibani MA, Alharbi S, Alonazy S, Almozeri M, Almutairi M, Alaqeel A. Saudi teachers' confidence and attitude about their role in anaphylaxis management. J Family Med Prim Care. 2019;8(9):2975-82. [CrossRef]

- Alomran H, Alhassan M, Alqahtani A, Aldosari S, Alhajri O, Alrshidi K. The right attitude is not enough: An assessment of knowledge, attitude, and practice of primary school teachers regarding food allergy in Al-Kharj, Saudi Arabia, 2022.

- Alzahrani L, Alshareef HH, Alghamdi HF, Melebary R, Badahdah SN, Melebary R, et al. Food Allergy: Knowledge and Attitude of Primary School Teachers in Makkah Region, Saudi Arabia. Cureus. 2023;15(9):e45203.

- Canon N, Gharfeh M, Guffey D, Anvari S, Davis CM. Role of Food Allergy Education: Measuring Teacher Knowledge, Attitudes, and Beliefs. Allergy Rhinol (Providence). 2019;10:2152656719856324.

- Dumeier HK, Richter LA, Neininger MP, Prenzel F, Kiess W, Bertsche A, et al. Knowledge of allergies and performance in epinephrine auto-injector use: a controlled intervention in preschool teachers. Eur J Pediatr. 2018;177(4):575-81. [CrossRef]

- Harper NJN, Cook TM, Garcez T, Lucas DN, Thomas M, Kemp H, et al. Anaesthesia, surgery, and life-threatening allergic reactions: management and outcomes in the 6th National Audit Project (NAP6). Br J Anaesth. 2018;121(1):172-88.

- Kolawole H, Guttormsen AB, Hepner DL, Kroigaard M, Marshall S. Use of simulation to improve management of perioperative anaphylaxis: a narrative review. Br J Anaesth. 2019;123(1):e104-e9. [CrossRef]

- Mason VM, Lyons P. Use of simulation to practice multidisciplinary anaphylaxis management. Dimens Crit Care Nurs. 2013;32(6):280-5.

- Sasaki K, Sugiura S, Matsui T, Nakagawa T, Nakata J, Kando N, et al. A workshop with practical training for anaphylaxis management improves the self-efficacy of school personnel. Allergol Int. 2015;64(2):156-60. [CrossRef]

- Rhim GS, McMorris MS. School readiness for children with food allergies. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2001;86(2):172-6.

- Sapien RE, Allen A. Emergency preparation in schools: a snapshot of a rural state. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2001;17(5):329-33. [CrossRef]

- Nowak-Wegrzyn A, Conover-Walker MK, Wood RA. Food-allergic reactions in schools and preschools. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2001;155(7):790-5. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).