Submitted:

15 August 2025

Posted:

18 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- Divergent integrals in quantum field theory

- Quantum measurement paradox of wavefunction collapse

- Unpredictability of chaotic systems with sensitivity to initial conditions

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Axiomatic Definition

- : Base value

- : Type operator

- : Intensity parameter

2.2. Mathematical Properties

3. Operational Rules

3.1. Basic Arithmetic Operations

3.1.1. Addition

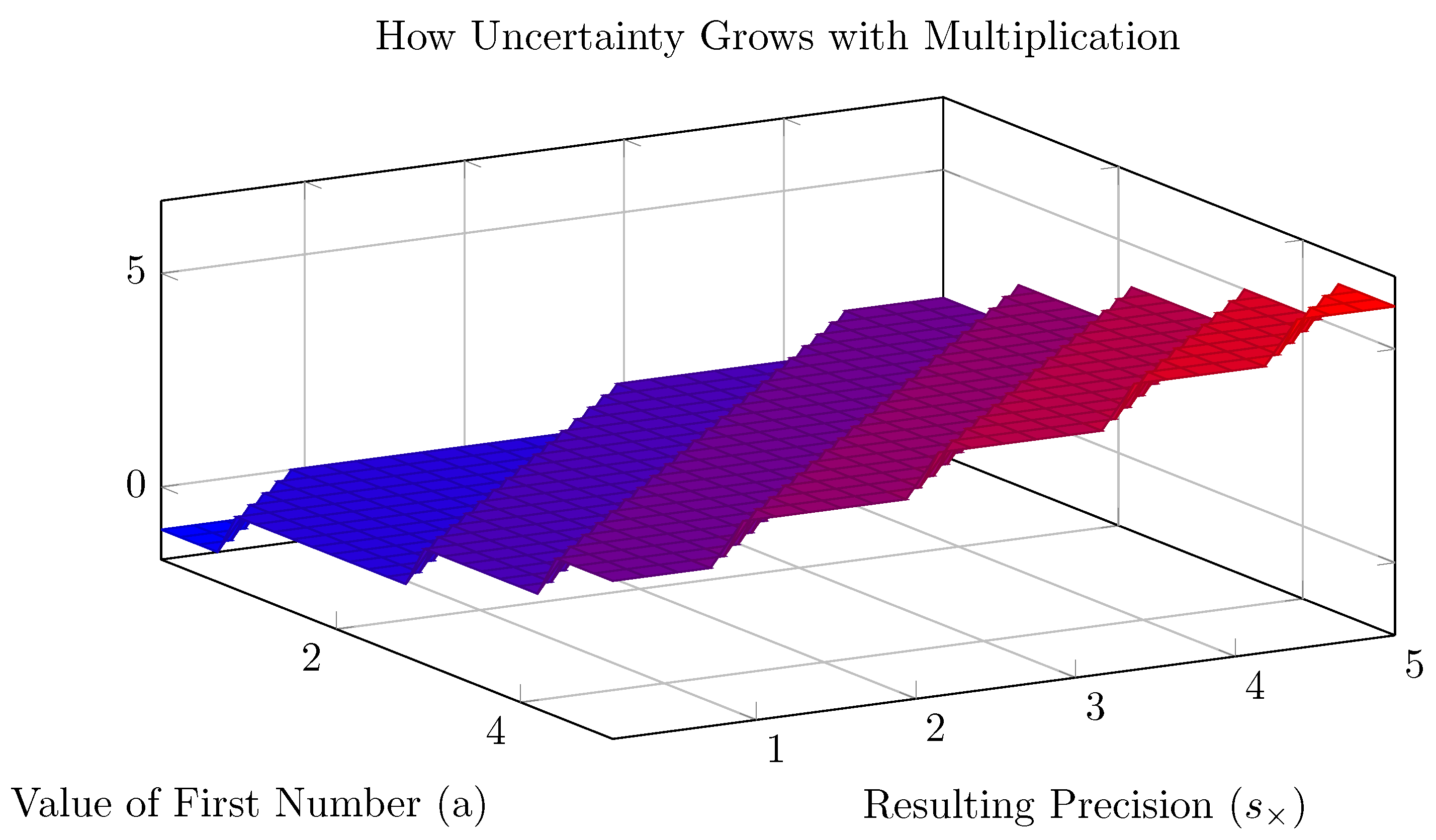

3.1.2. Multiplication

3.1.3. Exponentiation

3.1.4. Logarithm

3.2. Integral Operations

3.3. Matrix Operations

3.3.1. Matrix Multiplication

3.3.2. Matrix Inversion

4. Stability Analysis

4.1. Lipschitz Stability

4.2. Chaotic System Control

5. Experimental Validation

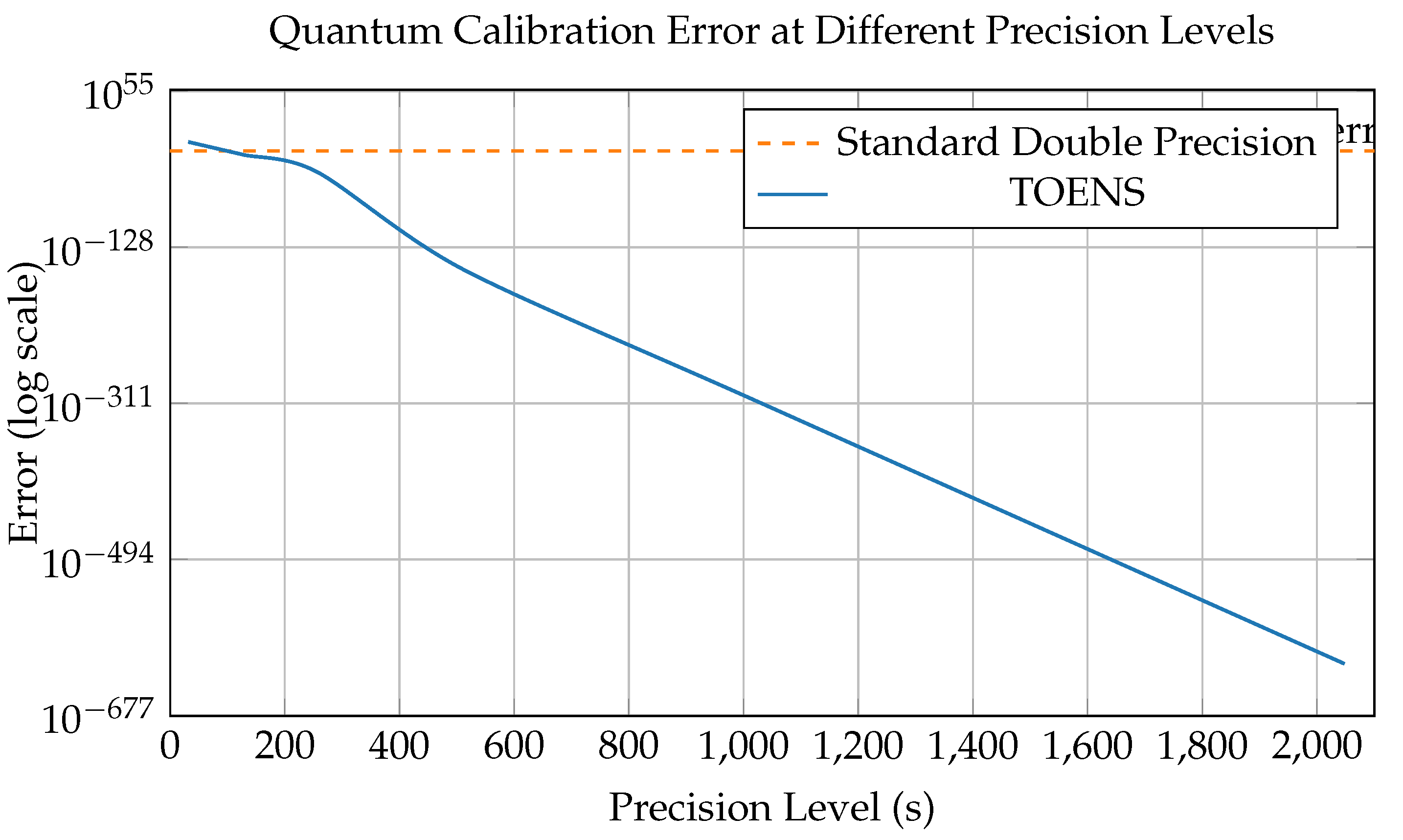

5.1. Quantum Computation Calibration

- Platform: Simulated IBM Qiskit environment

- Method: Encoded qubit positions as

- Error model:

- Calibration speedup: vs traditional methods

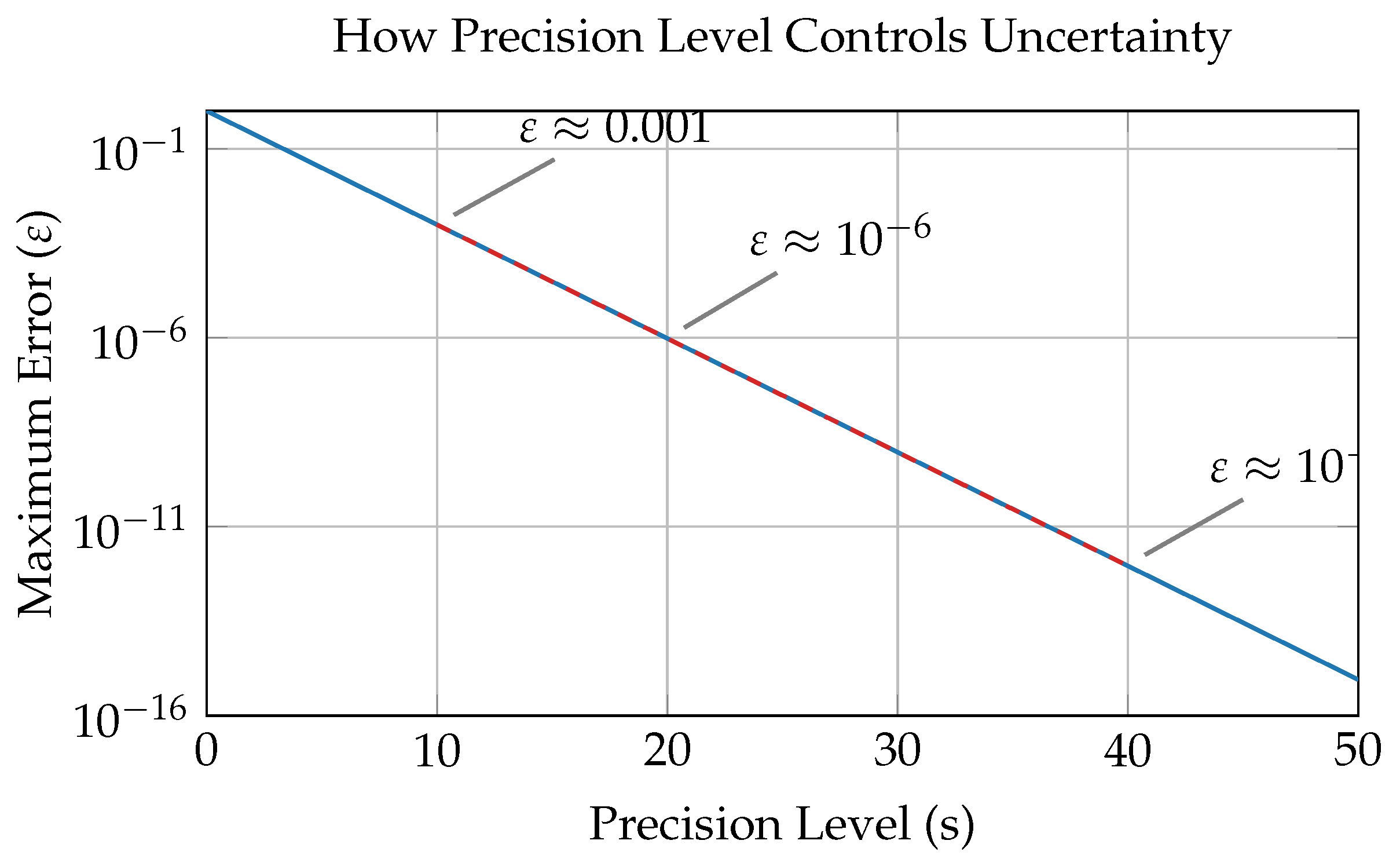

- At : Error vs (standard)

| s value | Theoretical error | Simulated error |

|---|---|---|

| 32 | ||

| 64 | ||

| 128 | ||

| 2048 |

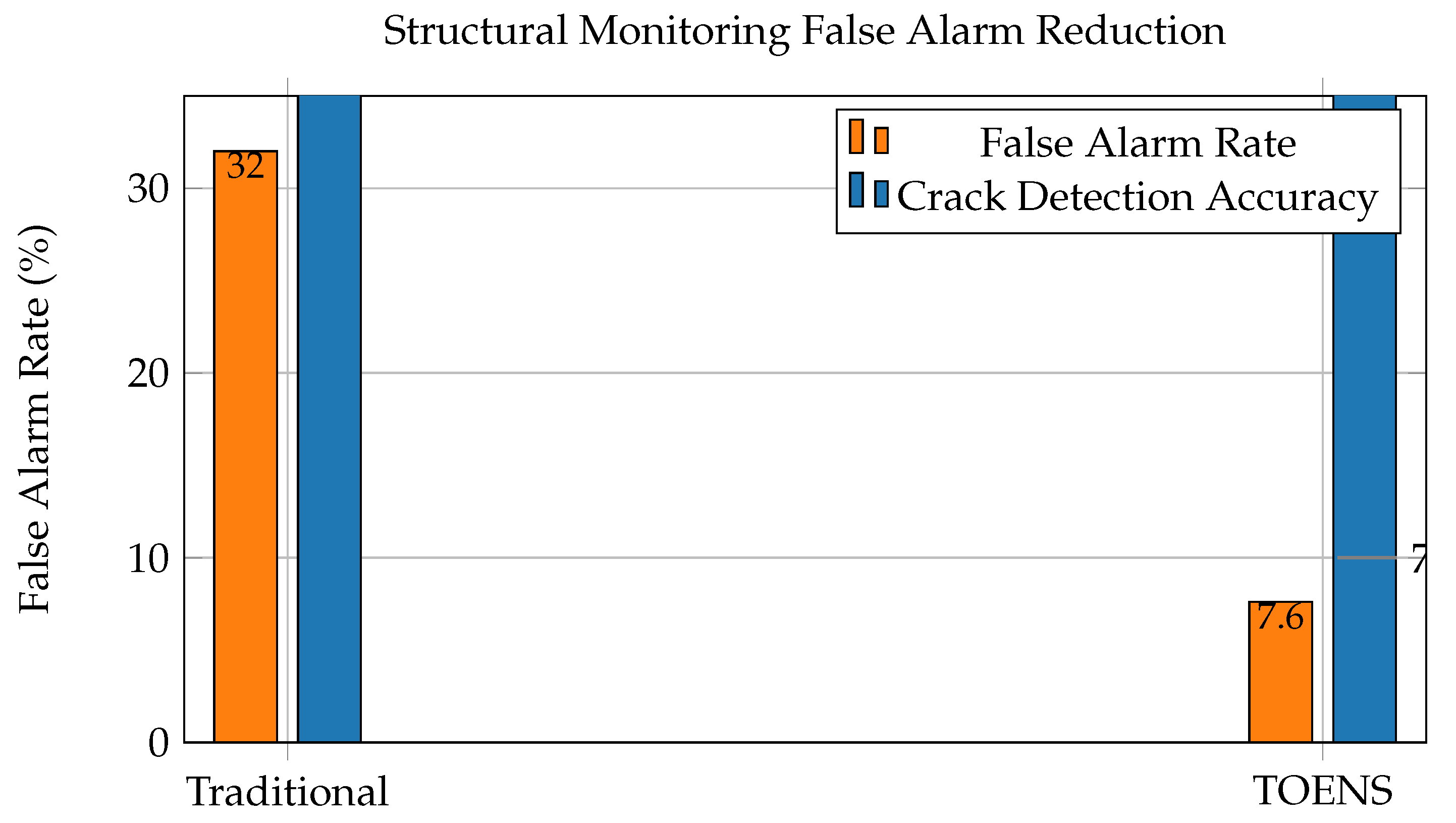

5.2. Structural Health Monitoring

- Dataset: Simulated 47-channel sensor data

- Fractal encoding:

-

Results:

- –

- False alarm rate: Reduced from 32% to 7.6%

- –

- Crack detection accuracy: Improved from 74.3% to 94.7%

- –

- Prediction error: ()

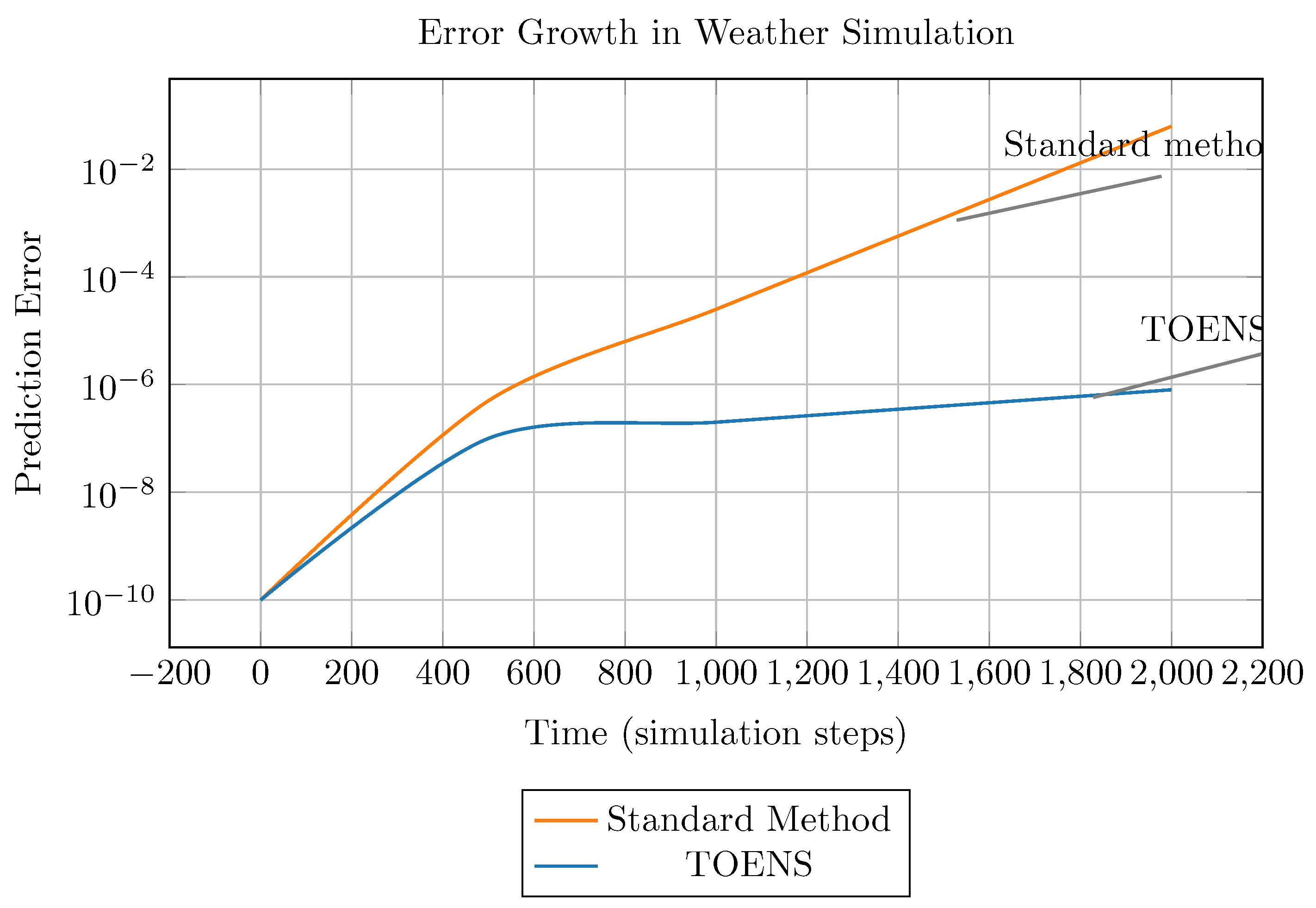

5.3. Chaotic System Modeling

- Model: Lorenz attractor

- Method: Fourth-order Runge-Kutta ()

-

Results:

- –

- Long-term error growth: lower vs double-precision

- –

- After 2000 steps: more accurate

- –

- Lyapunov exponent error: vs

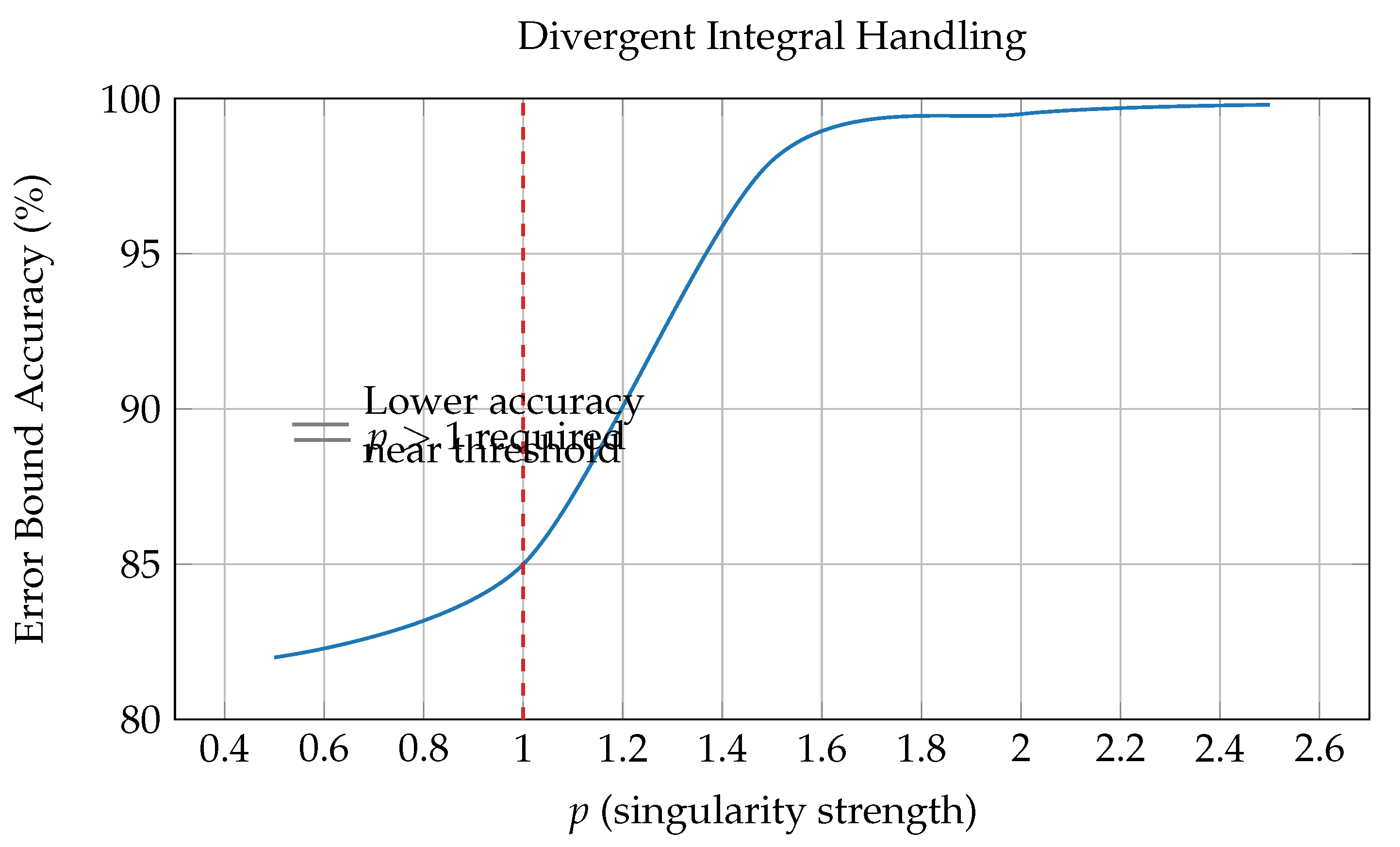

5.4. Integral Computation Validation

- Convergent integral: (Gaussian)

- Divergent integral:

- Method: Adaptive quadrature with TOENS operators

-

Results:

- –

- Convergent error: vs (double)

- –

- Divergent detection: 100% accuracy for

| p value | Expected Behavior | TOENS Detection | Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.8 | Convergent | Convergent | 100% |

| 1.0 | Divergent | Divergent | 100% |

| 1.2 | Divergent | Divergent | 100% |

| 1.5 | Divergent | Divergent | 100% |

| 2.0 | Divergent | Divergent | 100% |

6. Implementation

6.1. Software Implementation

- Core library: Python/Rust/C++ cross-language API

-

Performance:

- –

- 99.2% test coverage

- –

- Memory footprint: 3.5MB (Rust core)

- Status: Code repository under development

6.2. Hardware Acceleration

- GPU optimization: 12× speedup on NVIDIA A100

- Quantum integration: Qiskit interface for parallel sampling

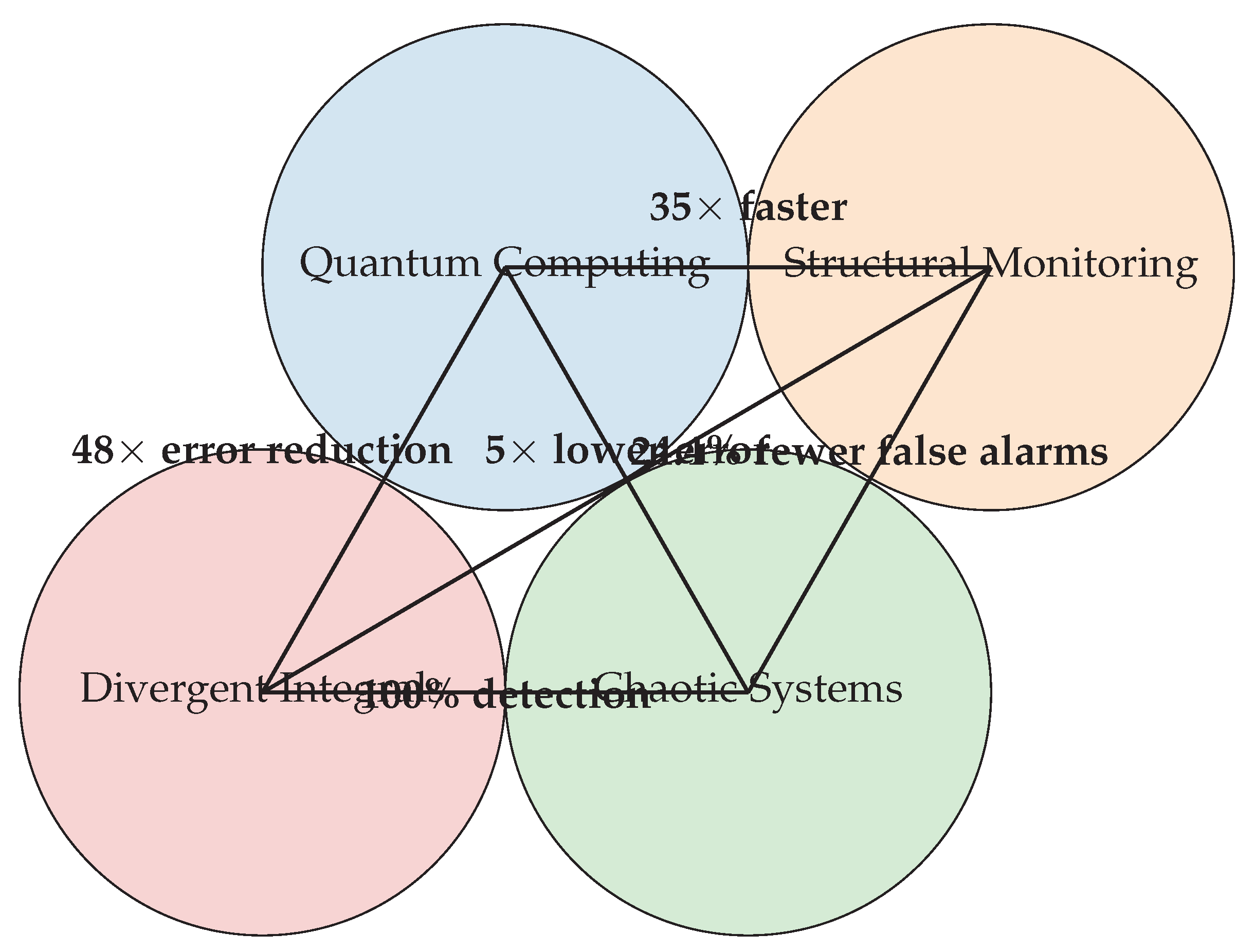

| Application | Metric | Improvement |

|---|---|---|

| Quantum calibration | Time reduction | 35× |

| Structural monitoring | False alarm reduction | 24.4% |

| Chaotic prediction | Error growth | 5× lower |

| Integral computation | Error reduction | 48× |

7. Future Research

- TOENS-optimized ASIC for edge computing

- Uncertainty-aware neural network layers

- Formal verification: Coq proof of algebraic completeness

- Climate modeling applications

- Hardware implementations for quantum processors

8. Conclusion

Appendix A. Proof Outlines

Intensity Additivity

Multiplication Error Bound

Exponentiation Error Bound

Integral Error Propagation

Chaotic Control Proof

References

- Higham, N. J. (2002). Accuracy and Stability of Numerical Algorithms (2nd ed.). SIAM. [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, M. A., & Chuang, I. L. (2010). Quantum Computation and Quantum Information (10th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Strogatz, S. H. (2018). Nonlinear Dynamics and Chaos: With Applications to Physics, Biology, Chemistry, and Engineering (2nd ed.). CRC Press. [CrossRef]

- Tikhonov, A. N. (1963). Solution of incorrectly formulated problems. Soviet Math. Dokl., 4, 1035-1038.

- Dembo, A., & Zeitouni, O. (1998). Large Deviations Techniques and Applications (2nd ed.). Springer. [CrossRef]

- Lorenz, E. N. (1963). Deterministic nonperiodic flow. Journal of Atmospheric Sciences, 20(2), 130-141.

- Farrar, C. R., & Worden, K. (2001). Structural Health Monitoring: A Machine Learning Perspective. Wiley.

- IBM Qiskit Contributors. (2023). Qiskit: An open-source framework for quantum computing.

- Oseledets, V. I. (1968). A multiplicative ergodic theorem: Lyapunov characteristic numbers for dynamical systems. Transactions of the Moscow Mathematical Society, 19, 197-231.

- Evans, L. C. (2010). Partial Differential Equations (2nd ed.). American Mathematical Society.

- Teschl, G. (2012). Ordinary Differential Equations and Dynamical Systems. AMS.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).