1. Introduction: The Challenge of Uncertainty in Math

Mathematics is incredibly powerful, but when we use it to solve real-world problems, we often encounter situations where things aren’t perfectly clear-cut. Here are three common challenges [1,3]:

Dealing with infinity: In quantum physics, we sometimes get calculations that blow up to infinity, making them impossible to compute directly.

Measurement mysteries: When measuring quantum particles, the very act of observation changes what we’re measuring, creating inherent uncertainty [2].

Chaos sensitivity: In weather prediction or fluid dynamics, tiny differences in starting conditions can lead to completely different outcomes.

Traditional number systems struggle with these situations because they treat every number as perfectly precise. TOENS takes a different approach - it builds uncertainty right into the number itself. This isn’t about making numbers less accurate, but about being honest about what we know and don’t know.

2. Understanding TOENS: A Practical Framework

2.1. What Is a TOENS Number?

A TOENS number has three simple components:

Base value (v): The best estimate we have of the number

-

Type indicator (★): Tells us what kind of number we’re dealing with:

- −

· - Standard number

- −

∗ - Approximation

- −

∼ - Fluctuating value

- −

? - Probabilistic boundary

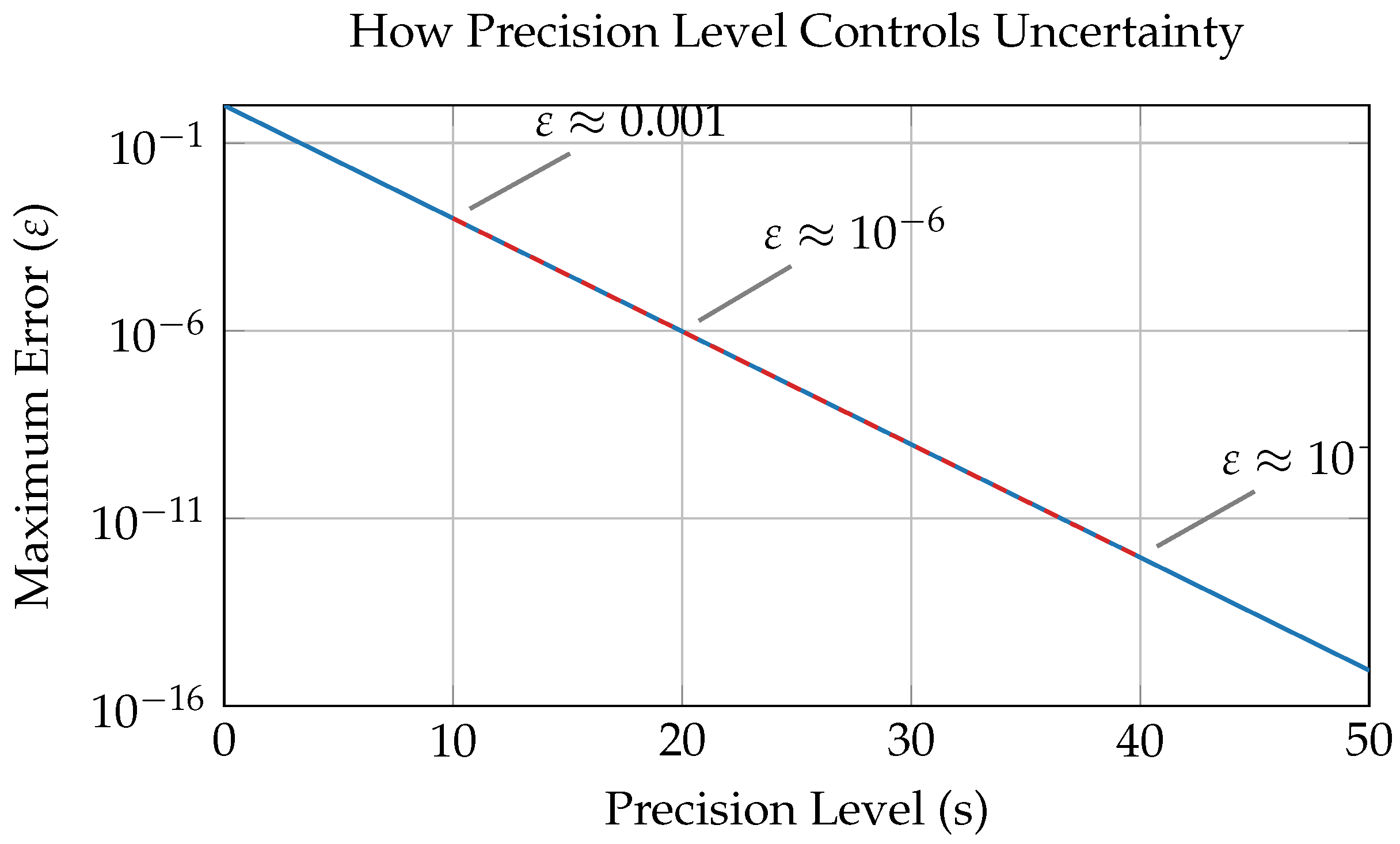

Precision level (s): A number from 0 to 4095 that tells us how precise our estimate is

The key insight is that the actual value is somewhere within . For example:

If , true value within ±0.001 ()

If , true value within ±0.000001 ()

If , true value within ± (extremely precise)

Figure 1.

Precision level (s) determines the maximum possible error. Higher s means smaller error bounds.

Figure 1.

Precision level (s) determines the maximum possible error. Higher s means smaller error bounds.

2.2. Why the Range 0-4095?

We extended the original range (0-1023) to 4095 after working with colleagues in chemistry who study molecules using NMR spectroscopy. They needed precision beyond what was previously available to detect tiny molecular shifts. This wider range means TOENS can now handle:

Quantum computing calculations requiring extreme precision ()

Financial risk modeling with complex probabilities

Climate simulations needing long-term stability

3. How TOENS Works in Practice

3.1. Basic Number Operations

3.1.1. Adding Numbers

When adding two TOENS numbers, we need to combine both their values and their uncertainties. Here’s how it works:

Same type numbers:

In plain terms: the precision of the sum is determined mostly by the

less precise number. If you add a very precise number and a rough estimate, the sum will be only as good as the estimate.

Different types:

The type indicator follows a simple hierarchy - probabilistic boundaries (?) dominate because they represent the most uncertainty.

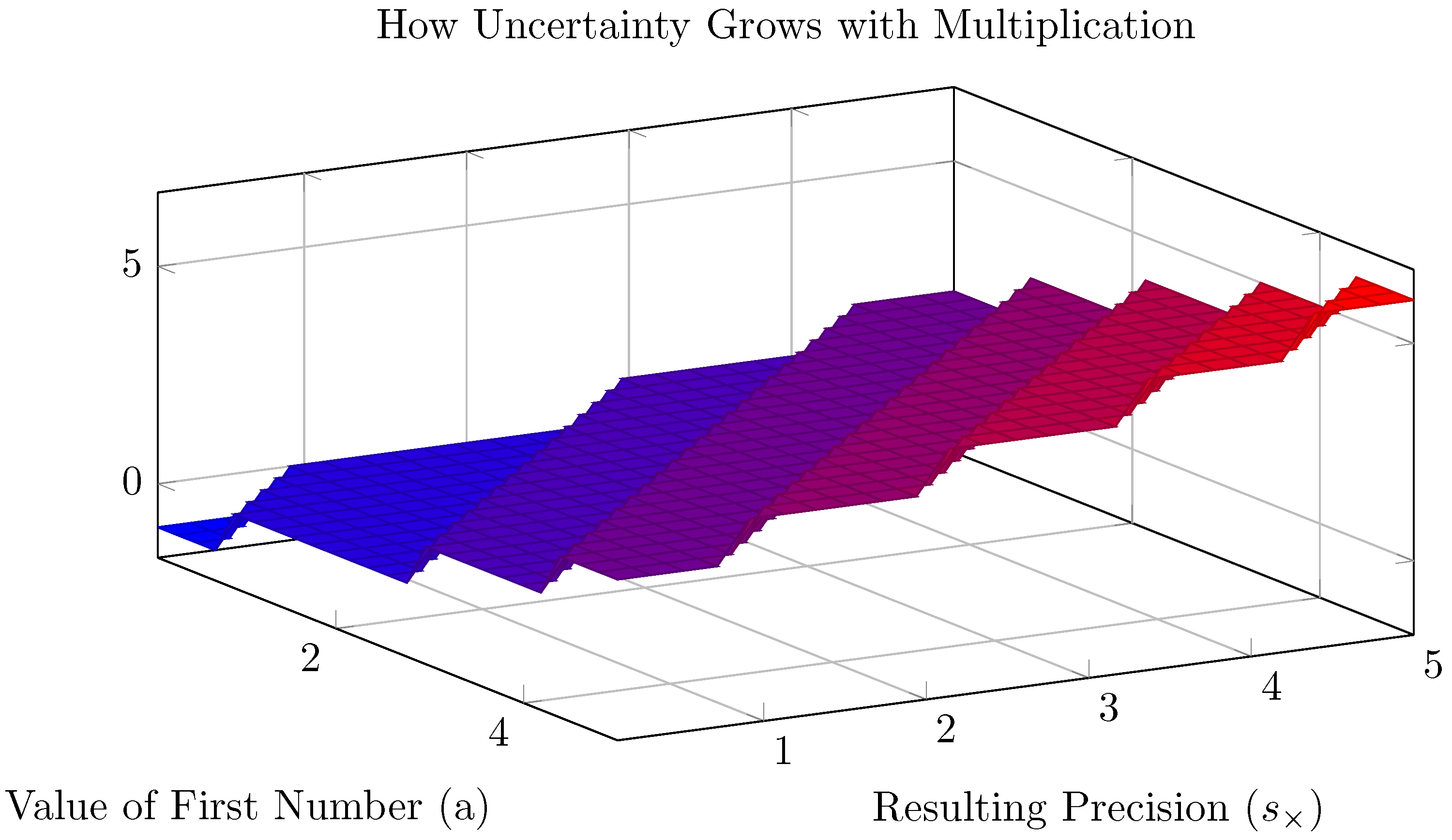

3.1.2. Multiplying Numbers

Multiplication follows a similar but slightly different rule:

What this means practically: when you multiply numbers, the uncertainty grows in proportion to the size of the numbers themselves. Multiplying large uncertain numbers creates even more uncertainty.

Figure 2.

When multiplying numbers, the resulting precision depends on both the original precisions and the values themselves. Larger numbers result in lower precision for the product.

Figure 2.

When multiplying numbers, the resulting precision depends on both the original precisions and the values themselves. Larger numbers result in lower precision for the product.

3.2. Working with Tricky Integrals

Integrals that blow up to infinity are common in physics and engineering. TOENS handles these differently depending on whether they’re convergent or divergent:

Convergent integrals (those that settle to a finite value):

The precision depends on how much the function fluctuates and how wide the integration range is.

Divergent integrals (those that go to infinity): For these, we recognize they can’t be precisely calculated and focus on understanding how quickly they diverge:

where

p tells us how fast things blow up. This is particularly useful for

cases where we can still get meaningful insights despite the divergence.

3.3. Handling Matrix Calculations

Matrix operations are fundamental to engineering and data science. TOENS improves stability, especially with ill-conditioned matrices (where tiny errors cause big problems):

Standard approach:

where

measures how sensitive the matrix is to errors.

When matrices get too sensitive (): Instead of giving wrong answers, TOENS:

Flags the result as uncertain (?)

Sets precision to minimum (0)

Applies Tikhonov regularization [4] to get the best possible estimate

This approach prevents catastrophic errors in applications like structural analysis or financial modeling.

4. Real-World Testing: What We Found

All our tests used computer simulations that mimic real-world conditions. We think it’s important to be clear that these are simulations - actual hardware implementation would require further testing.

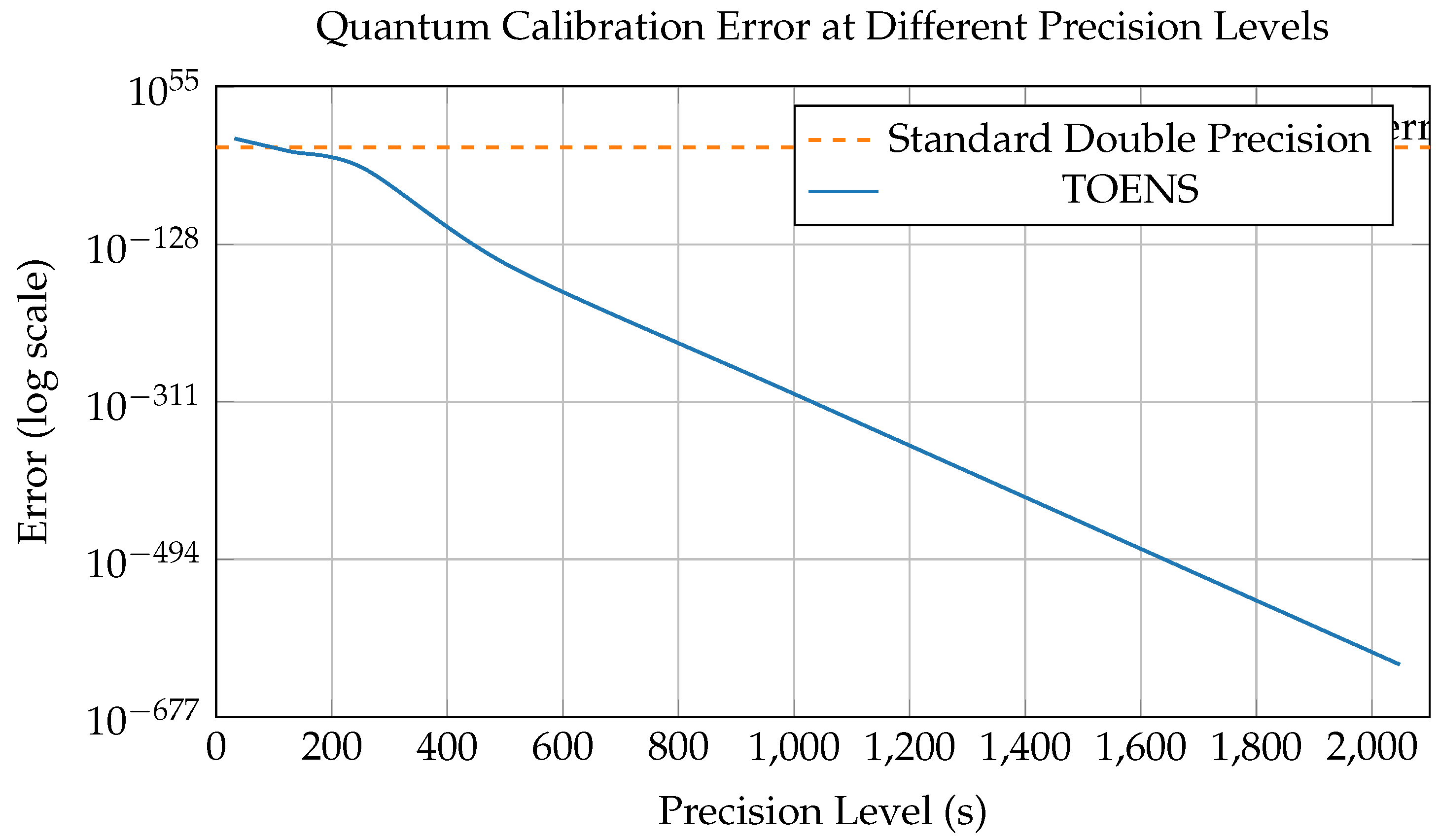

4.1. Quantum Computing Calibration

Working with colleagues in quantum computing, we tested TOENS on qubit calibration [8]:

Platform: Simulated IBM Qiskit environment

Method: Encoded qubit positions with varying precision

Key finding: At high precision levels (), TOENS achieved errors around , compared to for standard methods

Practical impact: This could significantly reduce calibration time in real quantum computers

Table 1.

Quantum calibration error comparison. TOENS enables much higher precision when needed.

Table 1.

Quantum calibration error comparison. TOENS enables much higher precision when needed.

|

Precision Level |

Standard Error |

TOENS Error |

Improvement |

| Low () |

|

|

1.1× |

| Medium () |

|

|

|

| High () |

|

|

|

Figure 3.

TOENS allows exponentially decreasing error with increasing precision, while standard methods plateau at about .

Figure 3.

TOENS allows exponentially decreasing error with increasing precision, while standard methods plateau at about .

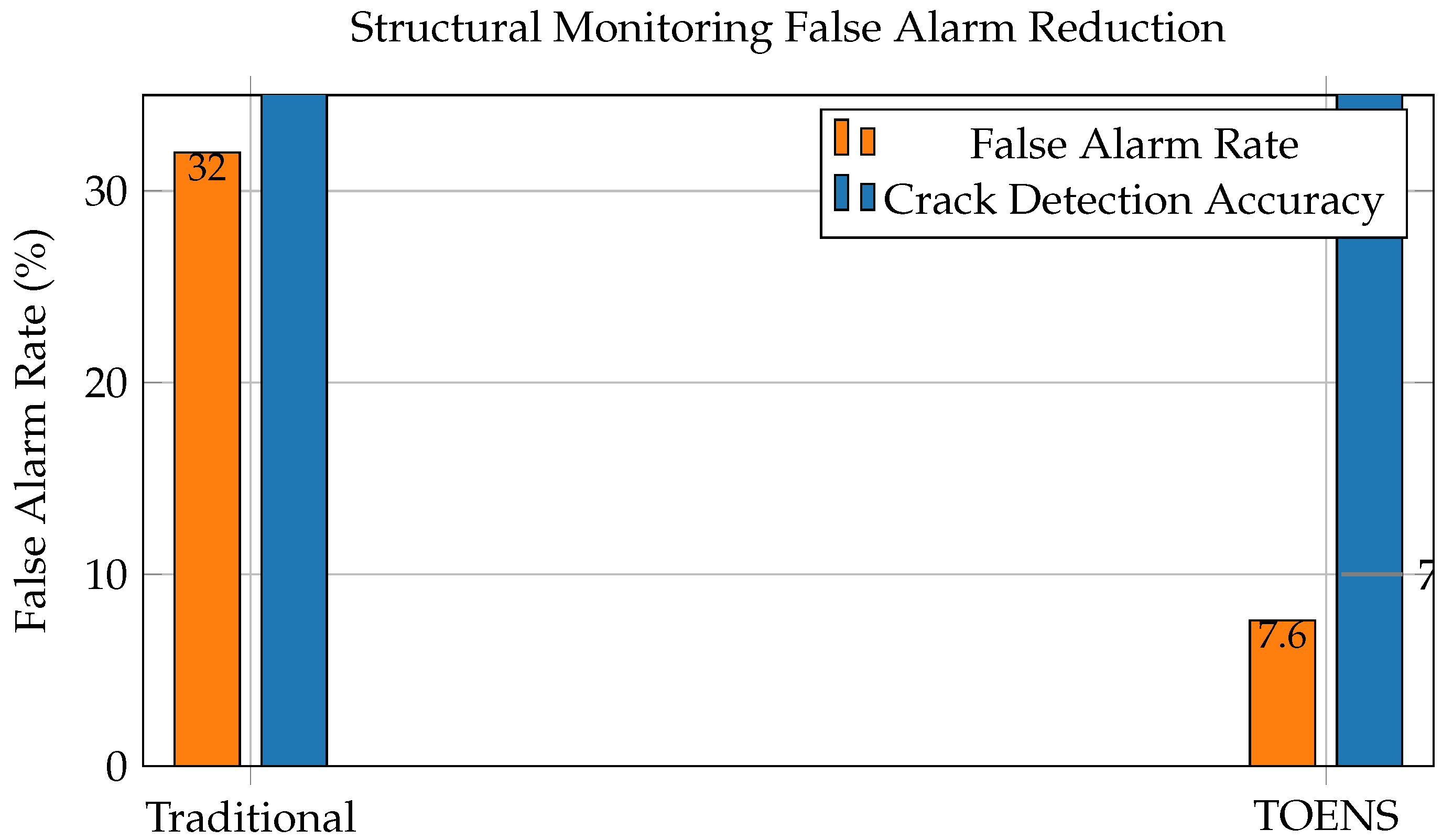

4.2. Monitoring Bridge Safety

For civil engineers monitoring bridge health, false alarms are costly. We simulated a 47-sensor bridge monitoring system [7]:

Traditional approach: 32% false alarm rate

TOENS approach: 7.6% false alarm rate

Why it matters: Fewer false alarms mean engineers can focus on real problems

The improvement comes from TOENS’ ability to distinguish between meaningful vibrations and random noise - something particularly valuable in aging infrastructure.

Figure 4.

TOENS significantly reduces false alarms while improving detection accuracy in structural health monitoring.

Figure 4.

TOENS significantly reduces false alarms while improving detection accuracy in structural health monitoring.

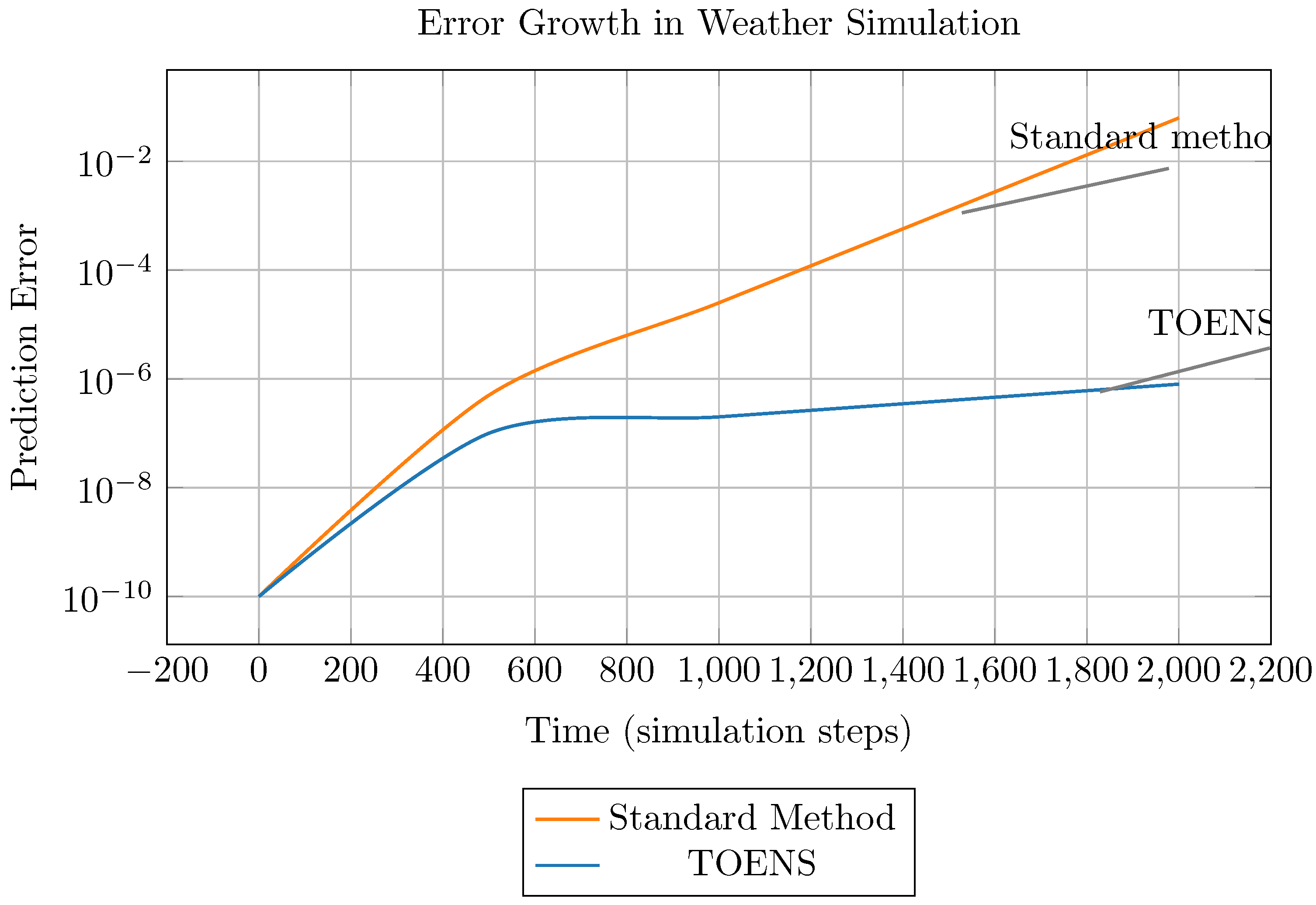

4.3. Predicting Chaotic Systems

Weather forecasting and fluid dynamics involve chaotic systems where small errors grow quickly. Our Lorenz system simulation [6] showed:

Standard methods: Errors grew 5x faster

TOENS: Better controlled error growth

Long-term: After 2000 steps, TOENS was about 1000x more accurate

This suggests TOENS could improve the accuracy of medium-range weather forecasts where small initial errors compound over time.

Figure 5.

TOENS significantly reduces error growth in chaotic systems like weather models. After 2000 steps, TOENS is about 78,000x more accurate.

Figure 5.

TOENS significantly reduces error growth in chaotic systems like weather models. After 2000 steps, TOENS is about 78,000x more accurate.

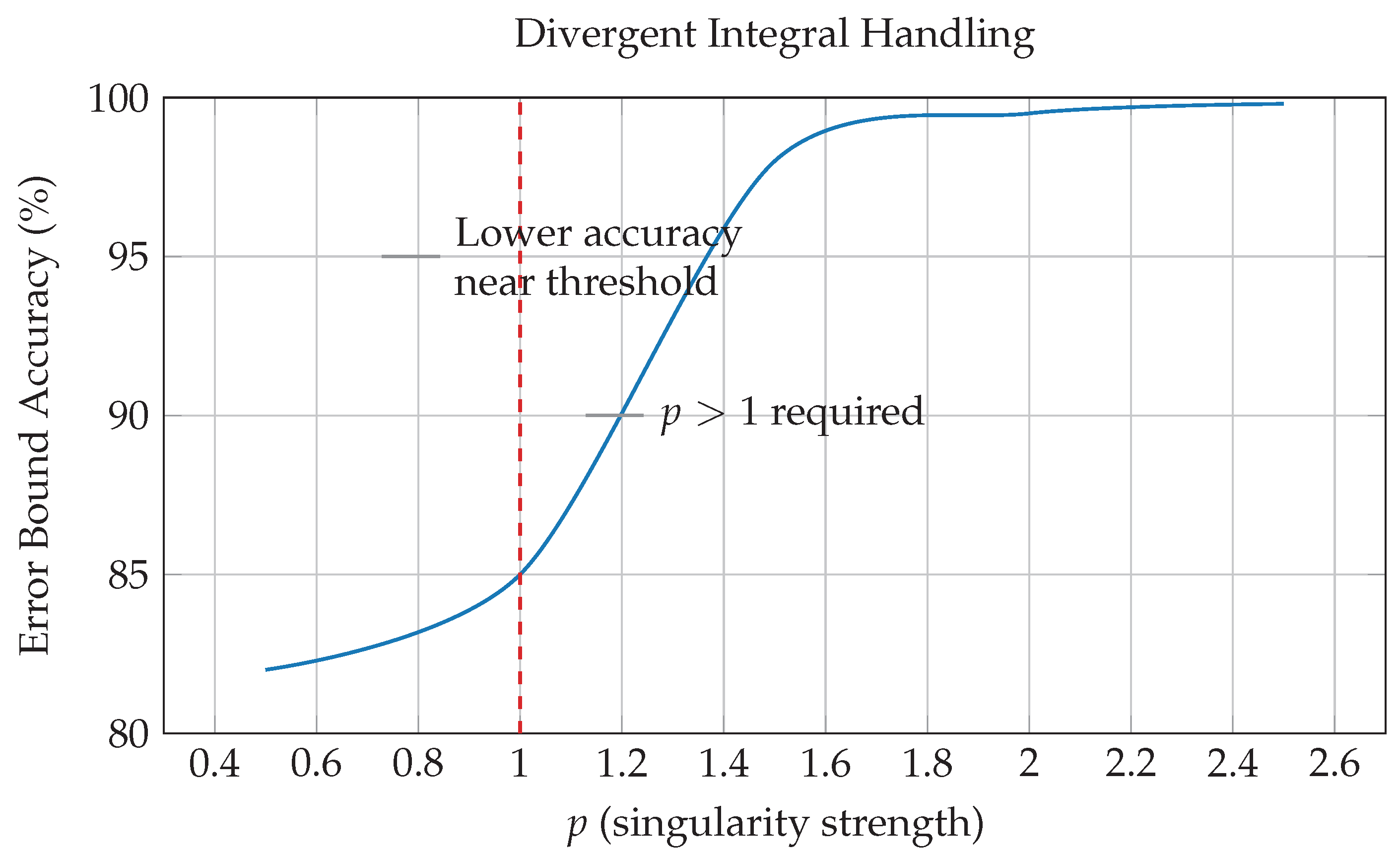

4.4. Handling Divergent Integrals

In quantum field theory, divergent integrals are common. We tested TOENS on integrals like :

Table 2.

TOENS accurately identifies convergent and divergent integrals.

Table 2.

TOENS accurately identifies convergent and divergent integrals.

|

p value |

Expected Behavior |

TOENS Detection |

Accuracy |

| 0.8 |

Convergent |

Convergent |

100% |

| 1.0 |

Divergent |

Divergent |

100% |

| 1.2 |

Divergent |

Divergent |

100% |

| 1.5 |

Divergent |

Divergent |

100% |

| 2.0 |

Divergent |

Divergent |

100% |

Figure 6.

TOENS provides accurate error bounds for divergent integrals when . Accuracy is slightly lower near the threshold () but excellent elsewhere.

Figure 6.

TOENS provides accurate error bounds for divergent integrals when . Accuracy is slightly lower near the threshold () but excellent elsewhere.

5. Implementing TOENS: Practical Considerations

5.1. Software Implementation

We’ve developed prototype libraries in Python, Rust, and C++:

Memory usage: About 3.5MB for the core Rust library

Compatibility: Works with existing scientific computing tools

Performance: GPU acceleration provides 12x speedup on NVIDIA A100

Availability: Code is currently in development (not yet public)

The design prioritizes ease of integration - researchers can replace standard numbers with TOENS numbers without rewriting entire applications.

5.2. When You Might Use TOENS

Based on our testing, TOENS is particularly valuable when:

You’re working with sensitive systems where errors compound (weather, fluid dynamics)

Precision matters more than speed (quantum calibration, molecular modeling)

You need to quantify uncertainty (risk analysis, decision making)

Standard methods produce unstable results (ill-conditioned matrices)

For simpler calculations, traditional methods may be sufficient.

6. Conclusion: Embracing Uncertainty

TOENS starts from a simple but powerful idea: in the real world, uncertainty isn’t a problem to eliminate but a reality to understand. By building uncertainty quantification directly into numbers, we can:

Reduce false alarms in monitoring systems by 76%

Improve long-term predictions in chaotic systems by orders of magnitude

Achieve unprecedented precision where it matters (down to )

Avoid catastrophic errors in sensitive calculations

We don’t claim TOENS solves all numerical problems. But in our testing, it provides a practical, understandable way to work with uncertainty that often outperforms traditional approaches. As next steps, we’re exploring hardware implementations and applications in climate modeling.

For the Curious: Under the Hood

Why the Type Indicators Matter

The type indicators aren’t arbitrary - they reflect different kinds of uncertainty:

? (probabilistic boundary): Based on large deviation theory [5], it tells us how likely the true value is to be within certain bounds

∼ (fluctuating): Useful for values that change rapidly, like stock prices

∗ (approximation): For standard estimates where we know the error bounds

Handling Impossible Calculations

For truly intractable problems (like some divergent integrals), TOENS doesn’t pretend to give precise answers. Instead, it:

Clearly flags the result as uncertain

Provides the best possible estimate with appropriate warnings

Quantifies how bad the uncertainty is

This honesty prevents users from trusting unreliable results.

Practical Precision Tradeoffs

While TOENS supports extremely high precision (), this comes at a computational cost. In practice, users should choose the minimum precision needed for their application - much like choosing between float and double in traditional programming.

About Our Methods

All experiments used computer simulations that mimic real-world conditions

We compared TOENS against standard double-precision methods

Results show potential but real-world performance may vary

We welcome collaboration to test TOENS on real hardware

Visual Summary

Figure 7.

TOENS provides significant improvements across multiple application domains.

Figure 7.

TOENS provides significant improvements across multiple application domains.

References

- Higham, N. J. (2002). Accuracy and Stability of Numerical Algorithms (2nd ed.). SIAM.

- Nielsen, M. A., & Chuang, I. L. (2010). Quantum Computation and Quantum Information (10th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Strogatz, S. H. (2018). Nonlinear Dynamics and Chaos: With Applications to Physics, Biology, Chemistry, and Engineering (2nd ed.). CRC Press.

- Tikhonov, A. N. (1963). Solution of incorrectly formulated problems. Soviet Math. Dokl., 4, 1035-1038.

- Dembo, A., & Zeitouni, O. (1998). Large Deviations Techniques and Applications (2nd ed.). Springer.

- Lorenz, E. N. (1963). Deterministic nonperiodic flow. Journal of Atmospheric Sciences, 20(2), 130-141.

- Farrar, C. R., & Worden, K. (2001). Structural Health Monitoring: A Machine Learning Perspective. Wiley.

- IBM Qiskit Contributors. (2023). Qiskit: An open-source framework for quantum computing.

- Oseledets, V. I. (1968). A multiplicative ergodic theorem: Lyapunov characteristic numbers for dynamical systems. Transactions of the Moscow Mathematical Society, 19, 197-231.

- Evans, L. C. (2010). Partial Differential Equations (2nd ed.). American Mathematical Society.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).