1. Introduction

The Internet of Things (IoT) is a collection of edge devices equipped with sensors, processing capabilities, software, and communication technologies that enable them to connect and exchange data with other devices and systems over the Internet or other networks.

The low power consumption and reduced cost of IoT edge devices have facilitated their widespread adoption in a variety of applications, including smart homes [94], healthcare [

2], smart vehicles [

2], Industrial IoT (IIoT) [

2], and wearable technologies [

2]. According to a recent forecast by the International Data Corporation (IDC), 41.6 billion IoT devices are expected to generate approximately 71.9 zettabytes of data by 2025 [

2]. Much of this data is captured by sensors that may collect sensitive user information, raising significant concerns about the security of IoT devices.

Edge computing is a technique for locally processing data that is captured or received on site, enabling real-time analysis of IoT data for specific applications, thereby avoiding being continuously transmitted to a data center or the cloud.

IoT systems have been the target of a wide range of attacks, including hardware attacks, denial-of-service (DoS) attacks [

2], software exploits, and password-based intrusions [

2]. For instance, a study in [

2] provides a review for malware families, including Mirai [

9] and Bashlite [

10], that were capable of compromising IoT devices and incorporating them into botnets to launch Distributed Denial of Service (DDoS) attacks. Additionally, the authors in [

2] demonstrated how they were able to unlock a commercial smart lock by reverse-engineering its mobile app and replicating the communication between the app and the lock.

Among these, hardware-based attacks are considered particularly severe, as they operate below the software layer, bypassing conventional security mechanisms and often achieving persistent control over the device. Unlike software-based threats, which can typically be mitigated through updates, addressing hardware vulnerabilities often requires physical modifications to the device, posing greater challenges for defense. Consequently, there is a pressing need for accurate and reliable techniques to assess the security of IoT edge devices [

11].

While several frameworks, most notably the Common Vulnerability Scoring System (CVSS) [

12], have been developed to evaluate the severity of security vulnerabilities, their applicability to IoT environments is limited. These limitations have been highlighted in multiple studies, including [

13,

14,

15], which suggest modifications to CVSS metrics to better accommodate the unique characteristics of IoT. However, such adaptations still lack a focus on hardware-specific security concerns.

The COSMIC ISO 19761 method [

16], developed by the Common Software Measurement International Consortium, represents a second-generation Functional Size Measurement (FSM) technique grounded in core software engineering principles. Unlike earlier FSM methods limited to business applications, COSMIC is domain-agnostic and designed to measure the functional size of software systems in a way that is independent of technology and implementation. It quantifies functional user requirements using a standardized and ratio-scaled unit—COSMIC Function Point (CFP), which enables valid mathematical operations and supports consistent benchmarking across projects. COSMIC has demonstrated practical value in software project estimation and performance assessment across diverse application domains, including IoT [

17,

18], aeronautics [

19], automotive systems [

20], and computer hardware [

21,

22]. Despite its versatility and proven accuracy in modelling complex systems, COSMIC has yet to be applied in the domain of cybersecurity, particularly for quantifying the functional size and assessing the impact severity of security attacks at the hardware level.

The ability to map COSMIC elements to computer hardware related low level software Instruction Set Architecture (ISA) [

21,

22] demonstrates its prospective capability of assessing the functional size of attacks, specifically hardware and memory-related attacks, hence inferring the security of the edge devices.

Extending COSMIC into this area could provide objective, repeatable measurements for threat modeling and security-focused system design.

This paper introduces a novel approach to evaluating the likelihood of memory-related attacks on IoT edge devices by leveraging COSMIC FSM for functional size measurement. A prototype tool is proposed to automate the assessment process of buffer overflow attacks, using ESP-based boards as a proof of concept to showcase its applicability.

This paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 provides a literature review for IoT-related attacks, Vulnerability assessment frameworks, and COSMIC FSM;

Section 3 presents an overview of mapping the COSMIC rules to IoT and Computer hardware;

Section 4 presents our COSMIC based assessment methodology;

Section 5 presents the prototype tool proposed along with its testing and validation;

Section 6 provides some discussion related to the tool;

Section 7 concludes the paper.

2. Literature Review

This section provides a literature review on related work discussing IoT-targeted attacks and frameworks proposed for IoT vulnerability assessment.

2.1. Classification of IoT-Based Attacks

Several reviews were proposed to categorize IoT-based attacks. For instance, a recent review study [

23] introduced a comprehensive taxonomy for categorizing IoT attacks, structured around a seven-layer architectural model. This model systematically classifies attacks based on the specific architectural layer they target. At the perception layer, which includes sensors and edge devices, common attacks include side-channel [

24] and node cloning attacks [

25,

26]. The abstraction layer, responsible for harmonizing diverse IoT devices through unified interfaces and standard protocols, is vulnerable to spoofing attacks [

26,

27]. The network layer, which facilitates communication among IoT devices and with external networks, faces threats such as the Routing Protocol for Low-Power and Lossy Networks (RPL) exploits [

28] and traffic analysis [

27]. At the transport layer, which manages data transmission protocols, typical attacks include session hijacking [

30], TCP SYN flooding [

29], and Message Queuing Telemetry Transport (MQTT) exploits [

31]. The computing layer, tasked with data processing, cloud communication, and storage, is targeted by threats like cryptojacking [

32] and Advanced Persistent Threats (APTs) [

33]. In the operation layer, which governs business logic and system management, attackers may exploit vulnerabilities in cloud APIs to gain unauthorized access to business data. A real-life incident occurred in 2018 when the social media platform Facebook experienced a security breach affecting approximately 50 million users. The breach was caused by a flaw exploited through a developed mobile application, leading to the unauthorized harvesting of data from around 87 million Facebook profiles [

34]. Finally, the application layer, responsible for delivering services to end users, is commonly affected by code injection [

35] and brute-force attacks [

2,

36].

Another taxonomy proposed by [

37] categorizes IoT attacks based on specific domains, namely: physical attacks [

38], network attacks [

2,

38,

39], software attacks [

35,

40,

41], encryption attacks [

24,

38,

42,

43] data attacks [

38,

39,

44], and side-channel attacks [

24,

38]. Physical attacks [

38] involve adversaries with physical access or proximity to the device or network, encompassing attacks such as fault injection and hardware tampering. Network attacks exploit vulnerabilities in communication channels, network protocols, or device connectivity, including attacks such as Man in the Middle [

39], Denial of Service [

2]. Software attacks target the software stack of IoT systems, including operating systems, firmware, applications, and software interfaces, such as malware [

40], Code injections [

35], and buffer overflow attacks [

41]. Encryption attacks [

42] focus on compromising cryptographic mechanisms, including attacks such as cryptanalysis [

43] and side-channel exploitation [

24,

38]. Data attacks threaten the confidentiality, integrity, availability, and overall security of data within IoT environments, such as Device Impersonation [

44], Man in the Middle [

39]. Finally, side-channel attacks aim to extract sensitive information, particularly cryptographic keys, by analyzing unintended physical emissions or computational characteristics of the system. According to the study, certain attacks can belong to multiple categories or domains.

In alignment with the objectives of our study, we focus our review in the following on hardware-based attacks targeting edge devices like microcontrollers, with particular attention to memory-related attacks such as buffer overflows, which, although initiated through software, directly impact the memory of these microcontrollers.

The next subsection presents a literature review of hardware and memory-related attacks

2.1.1. Hardware Attacks

A study referenced in [

45] conducted a threat analysis focused on IoT device identity. It identified three key assets that define an IoT device’s identity: its Integrated Circuit (IC) design, firmware, and stored secrets (e.g., passwords or cryptographic keys). Threats to these assets are categorized into two main types: invasive attacks, which involve physical tampering with the hardware, and non-invasive attacks, which do not alter the hardware. The study further breaks down threats into four categories: reverse engineering [

46,

47], fault injection [

48,

49], and side-channel attacks. Each of these can involve either invasive or non-invasive techniques. For example, reverse engineering may involve invasive chip delayering [

47] or non-invasive use of logical interfaces like JTAG to reverse engineer the firmware. To address these threats, the study further expanded the threat model to include the currently implemented technologies to secure the devices, such as True Random Number Generators (TRNGs), One-Time Programmable (OTP) memories, Secure Elements (SEs), cryptographic accelerators, and Trusted Execution Environments (TEEs). These protective measures are linked to specific mitigation strategies. For instance, SEs, crypto accelerators, and TEEs help overcome the need for lightweight encryption algorithms, hence storing sensitive information like passwords and keys securely.

Another review study by [

24] has provided a comprehensive analysis of hardware side-channel attacks. According to the study, side-channel attacks encompassed 2 main categories of attacks, namely Cache Side Channel and Power Side Channel. In addition, each category encompassed multiple attacks or techniques. For instance, the cache side channel included attacks such as Flush and reload [

50] or prime and probe [

51]. The paper further investigated how these attacks can be utilized alongside speculative execution related attacks, such as Spectre [

52], to infer sensitive information. The same thorough analysis was provided for the power side channel that encompassed techniques such as Differential power analysis. The paper also discussed Electromagnetic Analysis and Fault injection that could be utilized for bypassing security checks and exposing sensitive data. Finally, the paper has discussed the current security solutions with a brief insight into their role in protecting authenticity and confidentiality. Among the common solutions mentioned are the Cryptographic ISAs, Memory Encryption, Secure boot, and TEEs.

The following subsections will provide an overview of the commonly mentioned attack categories, including Side Channel and Fault injection, including real-life attacks for IoT.

A. Fault Injection Attacks

Fault Injection attacks are attacks that induce processing errors within the processor, typically to manipulate the normal execution or reveal secret information. This attack category encompasses Voltage Glitching, Electromagnetic (EM) interference, and Laser glitching. On one hand, voltage glitching and EM interference are considered non-invasive techniques that induce faults or alter execution flow by manipulating power and electromagnetic signals of the device. On the other hand, optical fault injection requires invasive access using lasers to induce faults at the transistor level.

The theoretical application of voltage glitching attacks to obtain the secret factor N of the RSA algorithm was early documented by [

48]. Later on, Differential Fault Analysis (DFA), a technique used to compare the faulty outputs produced from fault injection with the correct ones to infer secret information (such as cryptographic keys), was introduced by [

49].

In the context of IoT, an experiment conducted by [

53] demonstrated the feasibility of bypassing secure boot and flash encryption for the ESP32 V3 chip through a single EM glitch. The attack initially involved modifying the encrypted flash to alter the 32-bit CRC value of the bootloader signature. An EM glitch was then used to load this manipulated value into the Program Counter (PC), redirecting execution to the ROM’s download mode and enabling arbitrary code execution.

Another experiment conducted by [

54] demonstrated the feasibility of bypassing the secure boot of both ESP-C3 and ESP-C6 chips using a voltage glitch. The exploit relied on glitching a certain instruction during verifying the secure boot image to induce a buffer overflow, hence, redirecting the execution and bypassing the secure boot.

B-Side Channel Attacks

Side-channel attacks are non-invasive techniques that exploit physical leakages such as power consumption, execution timing, or electromagnetic emissions to extract sensitive data. Power-based attacks, including Simple Power Analysis (SPA) and Differential Power Analysis (DPA), were first demonstrated in [

55]. Timing attacks, whose concept was demonstrated practically in [

56], exploit data-dependent variations in execution time. Cache-based timing attacks, demonstrated in [

57], further extend this approach by leveraging timing differences between cache hits and misses to reveal memory access patterns and secret information.

A practical example of side channel attacks in the context of IoT is presented by the authors in [

58] when they utilized power analysis to recover the encryption and verification keys of a smart bulb’s firmware update mechanism, leveraging them to deploy a malicious over-the-air update.

Another study [

59] has presented a side channel attack that exploits the Central Processing Unit’s (CPU) interrupt mechanism to leak instruction-level timing information from secure enclave environments like Intel SGX, Sancus, and TrustLite. The attack leverages the delayed handling of exceptions and interrupts until instruction retirement. By precisely timing interrupts, an attacker with control over system software can infer fine-grained execution details from within hardware-protected enclaves. Nevertheless, [

60] examines the Nemesis attack presented by [

59] and proposes an effective mitigation approach. Their method involves rewriting binaries to insert padding opcodes, ensuring that all execution branches consume an equal number of CPU cycles, thereby preventing timing-based leakage.

2.1.2. Memory-Based Attacks

Although memory-based attacks often originate from software vulnerabilities, their implications can extend to the hardware layer, potentially resulting in the execution of malicious instructions or the disclosure of sensitive data. A notable example is the buffer overflow attack, which exploits programming flaws that allow an attacker to overflow a local variable (such as an array) with specially crafted inputs, thereby enabling the redirection of the function’s return address to execute attacker-controlled code. The viability of such attacks is largely attributed to the structure of the stack memory layout used during function calls. This issue is particularly critical in the context of IoT, where microcontrollers often lack dedicated hardware protections due to their limited processing capabilities. A study [

61] examined the feasibility of buffer overflow attacks on microcontrollers employing a Harvard memory architecture. The study highlighted key distinctions in stack layout between Harvard and von Neumann architectures. Despite the inherent challenges posed by the Harvard model, such as differences in stack growth direction the researchers successfully demonstrated a buffer overflow attack on the C8051F530 microcontroller.

Several studies have investigated memory-related attacks for IoT. For instance, [

62] has proven the feasibility of conducting Return-Oriented Programming attacks (ROP) for the Xtensa ISA supported by ESP boards. The paper focuses on how gadgets can be chained for Call 0 and Windowed ABI. Although certain protections have been introduced to mitigate buffer overflow attacks, including stack canaries that rely on inserting a canary word on the stack that is checked before function return, so that buffer overflow attacks altering this canary word are easily detected. A study presented in [

63] has shed a spotlight on vulnerabilities present in ESP boards that allow bypassing stack canaries.

Another study [

64] proposed by the same authors investigates the feasibility of extracting ROP gadgets by sniffing Over-The-Air (OTA) firmware updates for MSP430 microcontrollers. The authors were able to partially reconstruct the image by sniffing the OTA traffic, hence finding gadgets that can be used to exploit buffer-overflow vulnerability through ROP attacks. This study has addressed the limitations of finding gadgets for ROP attacks when firmware is protected from being dumped from the device through the approach presented.

Finally, authors in [

65] have highlighted the severity of buffer overflow vulnerabilities that could be exploited to bypass memory isolation techniques implemented by Trusted Execution Environments provided by ARM. The authors were able to embed a malicious mobile application in the secure world since IoT applications allow users to download untrusted third-party apps. Afterwards, the authors exploited the MOFlow vulnerability, which results from a missing validation check between the declared and actual message length sent from non-secure applications to secure ones. By embedding a false, shorter message length, an attacker can trick a secure application into leaking sensitive data from adjacent memory regions, potentially exposing information from other secure applications.

2.2. Vulnerability Assessment Frameworks for IoT

This section presents a literature review of existing frameworks developed for assessing vulnerabilities in IoT systems.

2.2.1. CVSS-Based Frameworks

Vulnerability assessment frameworks are primarily utilized by organizations to assess the severity of vulnerabilities, hence, prioritize the mitigation of vulnerabilities based on their severity.

CVSS is one of the widely adopted frameworks for vulnerability assessment. CVSS integrates 2 sets of metrics (Base Metrics), namely the Exploitability and Impact metrics, into a mathematical formula, resulting in a numerical score reflecting the severity of vulnerabilities.

The Exploitability metrics reflect the ease of exploiting a certain vulnerability. This set of metrics incorporates 4 metrics, namely Attack Vector (AV), Attack Complexity (AC), Privileges Required (PR), User Interaction (UI), and Attack Requirements (AR).

The impact metrics reflect the impact of exploiting a certain vulnerability. This set of metrics incorporates 6 metrics: Confidentiality, Integrity, Availability, Subsequent System Confidentiality (SC), Subsequent System Integrity (SI), Subsequent System Availability (SA).

It is worth mentioning that CVSS has incorporated a new Safety metric in its latest versions to accommodate IoT environments. In addition, it is optional to include the environmental metrics to assess the severity of a vulnerability within a specific environment.

CVSS was primarily designed for traditional IT systems. To that end, certain studies, such as [

13,

14,

15], have highlighted the limitations of applying CVSS for IoT contexts. Among the limitations discussed was the incompatibility of AV metrics with the IoT context, since IoT networks are not as well protected as traditional IT systems. The same concept applies to the AC metrics as attacking a certain IoT requires explicit knowledge of the design; hence, they are more complex. In addition, [

13] has highlighted the lack of a clear explanation provided for the CVSS mathematical formulas. However, it is worth mentioning that an internal report released by National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) [

66] has demonstrated that the CVSS base score equation generally aligns with the expert opinions of its maintainers.

Based on the mentioned limitation, the 3 studies have proposed different approaches to modify the CVSS to accommodate the IoT context that could be summarized as follows:

[

13] Has incorporated 2 sets of metrics in the base metrics, namely the Corporal Impact (CI) and Age (Ag) metrics. The CI assesses the hazards resulting from exploiting a certain vulnerability in a smart system, including metrics such as Not Defined, Human, Environment, and Self. Ag metrics represent the time span when the vulnerability was discovered. The paper has also proposed new metrics for the environmental and temporal metrics that are now suspended per the latest CVSS version.

[

14] has introduced new weights that are applied to the CVSS results, reflecting the severity of vulnerability in IoT contexts. The weights are assigned based on 5 metrics, namely Internet Exposure, Intranet Exposure, Shell Exposure, Physical Protection, and Exploit Code Maturity. For instance, if the Attack Vector (AV) is assigned the value P (indicating that the attacker requires physical access to the device) and the Physical Protection metric is set to True, then the CVSS base score is multiplied by 0.9 (the weight of physical protection per the paper)

[

15] has introduced new Local and Physical values in the AV, which are higher than those assigned for traditional IT systems, highlighting the ease of attacking IoT networks. The study has also modified the AC by introducing new M and H values that are lower than those assigned to the traditional IT system, reflecting the higher complexity of attacking IoT.

In addition, [

15] has extended their work to assess vulnerabilities within Industrial Control Systems (ICS), typically consisting of IoT and IT networks. Their proposed approach [

67] has introduced new metrics in the environmental metrics that are relevant to Industrial Control Systems.

Previous studies have addressed the limitations of CVSS applicability to IoT contexts, particularly [

14,

15] that attempted to provide more relevant assessments for the severity of vulnerabilities from the network and hardware perspective. Having said that, the studies did not provide a thorough analysis of hardware-related vulnerabilities; the studies merely integrated parameters reflecting Hardware (HW) protection without providing formulas to calculate these parameters. In addition, did not propose adjustments for improved assessments of HW related vulnerabilities. Nevertheless, they provided a valuable insight into assessing the severity of vulnerabilities in the context of IoT, where vulnerabilities can pose a harmful impact on its surrounding environment, unlike traditional IoT systems. To our best knowledge, the presented studies to adapt CVSS to the context of IoT did not provide a thorough analysis regarding HW or memory-related vulnerabilities

2.2.2. Non-CVSS-Based Frameworks

Some studies have been proposed to evaluate and categorize vulnerabilities using methods other than CVSS.

For instance, the authors in [

68] have analyzed hardware-related vulnerabilities from the Common Vulnerabilities and Exposures (CVE) database spanning 2010 to 2019 and categorized them according to different IoT application domains. They further utilized the categorized vulnerabilities to construct a labelled dataset that was used to train Support Vector Machine (SVM) classifiers aimed at predicting future hardware vulnerabilities. In addition, the authors in [

69] proposed a set of metrics to evaluate a device’s security against hardware attacks, specifically targeting Simple Power Analysis, Differential Power Analysis, Meltdown, and Spectre. To assess resistance to Power Analysis attacks, the paper introduced a mathematical equation incorporating seven distinct metrics. The metrics presented incorporated Software and Hardware-based mitigations. However, for Meltdown and Spectre, the evaluation was based on the output of the "lscpu" command that displays all the CPU-related information, including present mitigations against the mentioned attacks. Although [

69] presents a promising approach for assessing hardware vulnerabilities, it does not fully address memory-related attacks, specifically buffer overflows.

Another study [

70] has provided a threat model for the common HW attacks, including side channels and reverse engineering, alongside metrics to assess the security of the device against each attack category. For instance, the amount of sensitive information that was vulnerable to side channels and the number of samples required to extract the information were the 2 key metrics for assessing the device security against side channels. Although the paper discussed various HW attacks, memory-related attacks such as buffer overflows were not covered.

In summary, previous studies have either focused on improving the assessment of vulnerability severity without thoroughly analyzing hardware-specific issues or have proposed metrics for evaluating hardware-related vulnerabilities without addressing the severity of memory-based attacks. The following

Table 1 compares the reviewed studies with respect to the vulnerabilities analyzed.

To the best of our knowledge, no vulnerability assessment frameworks have addressed the assessment of memory-related vulnerabilities with respect to COSMIC.

3. COSMIC FSM Background

3.1. COSMIC FSM

The Common Software Measurement International Consortium (COSMIC) method [

16] is an ISO-recognized standard [

71] for Functional Size Measurement (FSM) that quantifies the amount of functionality software delivers to its users, independently of the technology used to implement it. As a second-generation FSM method, COSMIC was developed to address the limitations of earlier FSM methods such as IFPUG [

72] and NESMA [

73], which were primarily oriented toward business applications and lacked domain flexibility.

COSMIC [

16] is designed for universal applicability across multiple domains, including business applications, real-time systems, embedded software, and infrastructure software. It is also particularly well-suited to modern software architectures such as Service-Oriented Architectures (SOA), data warehouses, and mobile applications.

3.1.1. Foundational Principles and Objectives

3.2. Foundational Principles and Objectives

COSMIC is designed to meet two primary objectives in software engineering: enabling performance measurement of development and maintenance activities, and supporting effort estimation for new software projects. It achieves these objectives by providing a standardized, ratio-scaled unit of measurement, the COSMIC Function Point (CFP), which allows for valid mathematical operations and consistent comparison across projects. This characteristic marks a significant advancement over earlier FSM approaches, many of which operated on ordinal or step-based scales with limited applicability across domains.

Beyond traditional use cases, COSMIC size have also been successfully applied to measure technical indicators such as: processor load, energy consumption, and other resource utilization parameters, particularly in embedded and real-time systems [

20,

74]. These applications demonstrate the method’s versatility in supporting both software sizing and system-level performance measurement and estimation.

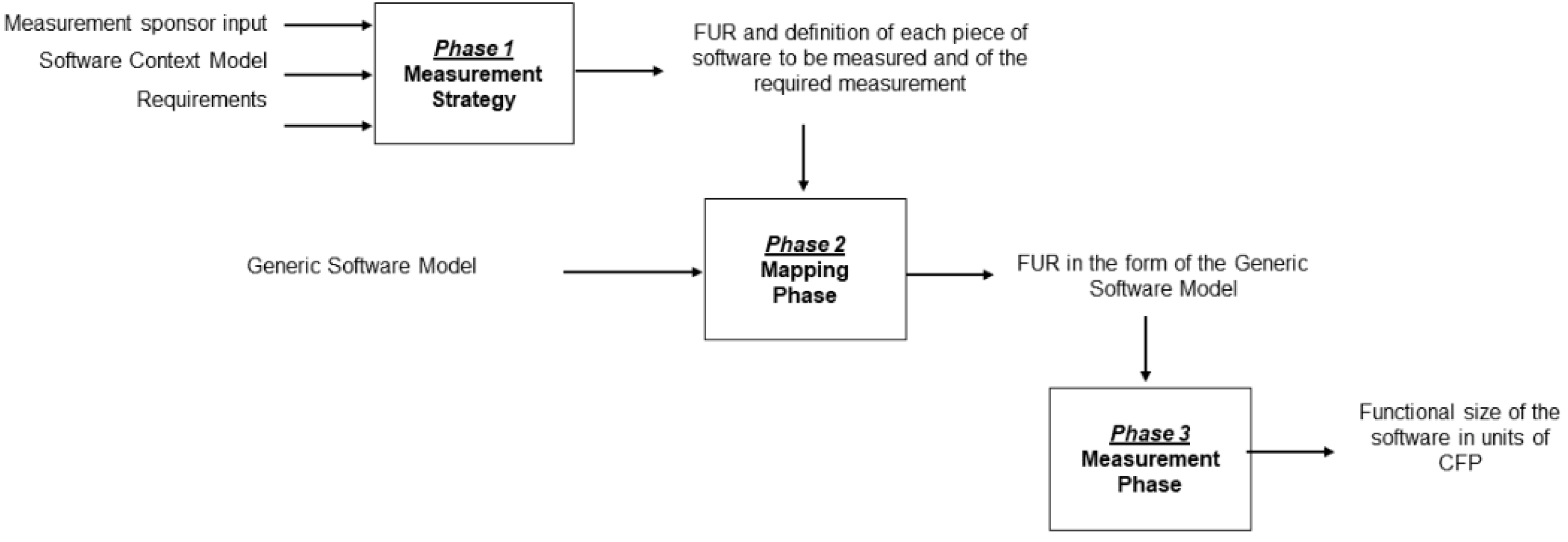

3.2.1. Method Architecture and Phases

The COSMIC measurement process is structured into three key phases: the

Measurement Strategy Phase, the

Mapping Phase, and the

Measurement Phase as shown in

Figure 1.

Measurement Strategy Phase: This initial phase defines the purpose (e.g., effort estimation, benchmarking) and scope (e.g., single application, system component) of the measurement. It results in a Software Context Model that identifies the software boundary, its functional users (humans, devices, or other software), and its persistent storage components.

Mapping Phase: In this phase, the Functional User Requirements (FURs) are mapped to COSMIC’s Generic Software Model. Each FUR is decomposed into one or more functional processes, each of which consists of a sequence of data movements (Entries, Exits, Reads, Writes). These data movements reflect the interaction between the software and its users or storage elements.

Measurement Phase: Finally, each functional process is measured by summing its constituent data movements. The functional size of the software is the total number of data movements across all functional processes. Since each data movement corresponds to one CFP, the resulting size is additive and not limited by predefined categories or thresholds, allowing for precise granularity in complex systems.

3.2.2. Core Measurement Constructs

The COSMIC method is based on two key concepts: functional processes and data group movements.

According to COSMIC, a functional process is defined as follows:

- a.

A functional process consists of a set of data movements that represent an elementary component of the software’s functional user requirements (FUR). Each functional process is unique within the overall FUR and can be defined independently of other functional processes.

- b.

Each functional process is triggered by a single Entry data movement. Processing begins when the functional process receives a data group through the triggering Entry.

- c.

The complete set of data movements within a functional process includes all those necessary to fulfil its FUR, covering every possible response initiated by its triggering Entry.

In addition, COSMIC defines four atomic types of data movement, which collectively form the basis of functional size computation [

16]:

Entry represents the single, distinct flow of data from a functional user across a defined boundary into a functional process.

Exit represents the single flow of a data group from a functional process across a boundary to a functional user.

Read represents the movement of a single data group from persistent storage into a functional process.

Write signifies the movement of a single data group from a functional process into persistent storage.

Each movement involves a data group representing a set of related attributes about a real-world object of interest. One data movement of one data group equals one CFP.

3.2.3. Domain Applicability and Automation

In real-world industrial settings, COSMIC has demonstrated measurable benefits. For instance, Renault has successfully automated the measurement of embedded software specified in Matlab/Simulink, achieving an accuracy rate above 99 % and using COSMIC size in procurement and cost negotiations for Electronic Control Units (ECUs) [

75]. Additionally, COSMIC has been effectively used in agile environments to replace less standardized methods like Story Points, providing objective, repeatable estimates that improve planning and project accountability [

76,

77]. It has also been successfully adapted to specialized domains, such as embedded systems in the aerospace domain, where [

19] mapped COSMIC rules to real-time applications. Similarly, [

20] proposed a prototype for applying COSMIC Functional Size Measurement (FSM) within the AUTOSAR framework. Finally, studies in [

78,

79,

80] demonstrated its applicability to quantifying the functional size of quantum software.

3.2.4. COSMIC for Treatment of Non-Functional Requirements’ Measurement

Although COSMIC is explicitly designed to measure functional user requirements, it also allows for the indirect quantification of certain Non-Functional Requirements (NFRs) when these result in observable functional behavior. For example, a requirement for portability might lead to the development of an isolation layer, which can be measured functionally. Similarly, maintainability and security requirements often result in additional functionalities (e.g., parameter maintenance interfaces or authentication modules) that COSMIC can measure [

16,

81].

3.3. Application Domains of COSMIC FSM

3.3.1. COSMIC FSM in IoT

Mapping COSMIC Rules to IoT

The initial attempt to apply COSMIC measurement rules to the Internet of Things (IoT) domain was introduced in [

82]. The study presents a set of mapping rules, based on the COSMIC method, specifically designed for IoT applications developed using the Arduino IDE [

83].

The study identifies the setup() and loop() functions in Arduino code as functional processes, each associated with a single triggering entry. The setup() function runs at system startup or reset, initializing input/output pins that interact with functional users, such as sensors and actuators in IoT systems. Once setup is complete, the loop() function executes continuously, enabling ongoing data exchange between the system and its functional users according to the specified functional requirements.

Each function in the Arduino code that utilizes an INPUT pin is treated as a COSMIC Entry, while those involving an OUTPUT pin are categorized as COSMIC Exits. Function calls that retrieve data from EEPROM are identified as COSMIC Reads, and those that store data to EEPROM are considered COSMIC Writes. Each of these Entry, Exit, Read, or Write accounts for one Cosmic Functional Point (CFP).

The following

Table 2 provides examples of data group movement and their respective mapping:

Based on the mapping rules provided, [

17] has utilized the mapping rules previously presented to automate functional size measurement of Arduino codes by introducing a prototype tool. However, the tool only supported a limited number of Arduino libraries. The same authors in [

18] have addressed this limitation through integrating Natural Language Processing (NLP) into their tool, allowing the generic analysis of Arduino codes using Machine learning and Regular expressions. [

84,

85] proposed means to improve the accuracy of the tool presented in . While [

84] has focused on enhancing the performance of the machine learning models, [

85] has focused on the recursive analysis of function calls, since each function call inferring data movement could recursively include other function calls, the study has examined each function call in depth, to assign accurate number of Cosmic Function Points (CFPs) rather than just inferring 1 CFPs for each function call.

3.3.2. COSMIC FSM in Computer Hardware

The proposed rules for mapping COSMIC FSM to computer hardware were primarily intended to assess functionality from a hardware perspective, since every software is translated to assembly instructions that reflect data movements between the HW components as CPU, registers, and memory, the functional size is inferred from the assembly instructions of the software. Consequently, these rules provide a generic measure of functional size that is not only independent of the programming language but also able to depict the data movements at the hardware level [

22].

Several studies have been proposed to map the COSMIC rules to the hardware level, enabling the measurement of the functional size of assembly programs. For instance, [

21] has proposed an approach to map cosmic rules to the MIPS Instruction Set Architecture (ISA). Similarly, other studies proposed to map the COSMIC rules to the X86 ISA [

86] and ARM ISA [

22]. The primary distinction among the mapping approaches proposed in the three studies lies in the treatment of registers and the register file. In particular, both [

22,

86] classify registers and the register file as part of the persistent storage. Consequently, any instruction that performs a read from or write to a register infers read or write data movement, according to the COSMIC rules. Conversely, the approach in [

21] limits the identification of read and write data movements to load and store instructions, which are respectively mapped to Read and Write operations.

Mapping COSMIC Rules to Computer Hardware

[

21] has proposed simple and sufficient mapping rules to the COSMIC ISA. According to the rules proposed in [

21],

CPU represents the sole functional user

Each function or subroutine represents a functional process

Each source register or immediate value in a register represents an Entry

Each destination register in an instruction represents an Exit (N.B.: same concept holds for Program Counter register (PC) updates due to jump or branch instructions as well, hence, the update of PC due to a jump or branch instruction accounts for 1 Exit )

Return value after branch and link or jump and link instructions represents an Exit

Each load instruction represents a Read

Each store instruction represents a Store

A notable limitation of the presented rules is that read and write operations are inferred solely from load and store instructions that access non-persistent memory. Nevertheless, they effectively capture the memory access patterns.

3.3.3. Leveraging COSMIC for Memory Vulnerability Assessment in IoT Edge Systems

Given the growing complexity and resource constraints of IoT edge systems, especially those involving embedded software and real-time processing, precise assessment of security vulnerabilities requires structured, quantifiable measures. COSMIC, with its ability to measure functional user requirements at a granular level, including reads from and writes to persistent storage, offers a powerful framework for quantifying the functional exposure of software components to memory-based attacks. Vulnerabilities such as buffer overflows, unauthorized memory access, and code injection often exploit specific functional pathways involving data movement to and from memory. By modelling software using COSMIC and quantifying these memory-related functional processes (e.g., excessive Writes to volatile memory or reads from insecure regions), developers can assess potential attack surfaces systematically. This is particularly valuable in IoT edge environments, where limited memory and computation power make both optimization and security critical. Furthermore, COSMIC’s ability to distinguish changes in functional size over time enables tracking of vulnerability impact and regression across updates or patches. Thus, integrating COSMIC into security assessment pipelines could enhance early threat detection, inform mitigation strategies, and support formal certification efforts for memory-safe software in edge devices.

To the best of our knowledge, existing vulnerability assessment frameworks have not incorporated COSMIC for evaluating memory-related vulnerabilities.

For the purpose of our study, we apply COSMIC hardware mapping rules to assess memory-related vulnerabilities. Although memory-related vulnerabilities are typically exploited through software, they have significant implications at the hardware level, such as manipulation of stack memory and function return addresses. Therefore, a granular analysis that includes hardware components is essential to accurately assess these vulnerabilities.

In this study, buffer overflow vulnerabilities are explored as a representative example of memory-related vulnerabilities. The attack scenario and the assessment methodology are outlined in the following section. It is important to emphasize that the evaluation of buffer overflow vulnerabilities serves as a proof of concept to validate the feasibility of our proposed approach.

4. COSMIC Mapping for Memory-Related Vulnerabilities and Attacks

4.1. ESP Background

ESP boards developed by Espressif are a family of low-cost micro-controllers integrating both Wi-Fi and Bluetooth capabilities, primarily utilized for IoT applications. ESP boards support Tensilica processors that are based on the Xtensa Instruction Set Architecture (ISA) [

87]. Xtensa ISA is a post-RISC design developed by Tensilica; it inherits the efficiency of RISC principles while selectively integrating CISC features where beneficial. The standard Xtensa instruction length is 24 bits, with an optional code density extension that enables 16-bit instructions; wider instruction formats are also supported in certain configurations. Furthermore, Xtensa processors implement a Harvard architecture with separate instruction and data buses, which may interface with distinct or shared memory systems depending on the system-on-chip design.

4.1.1. Memory Management for Function Calls in the Xtensa ISA

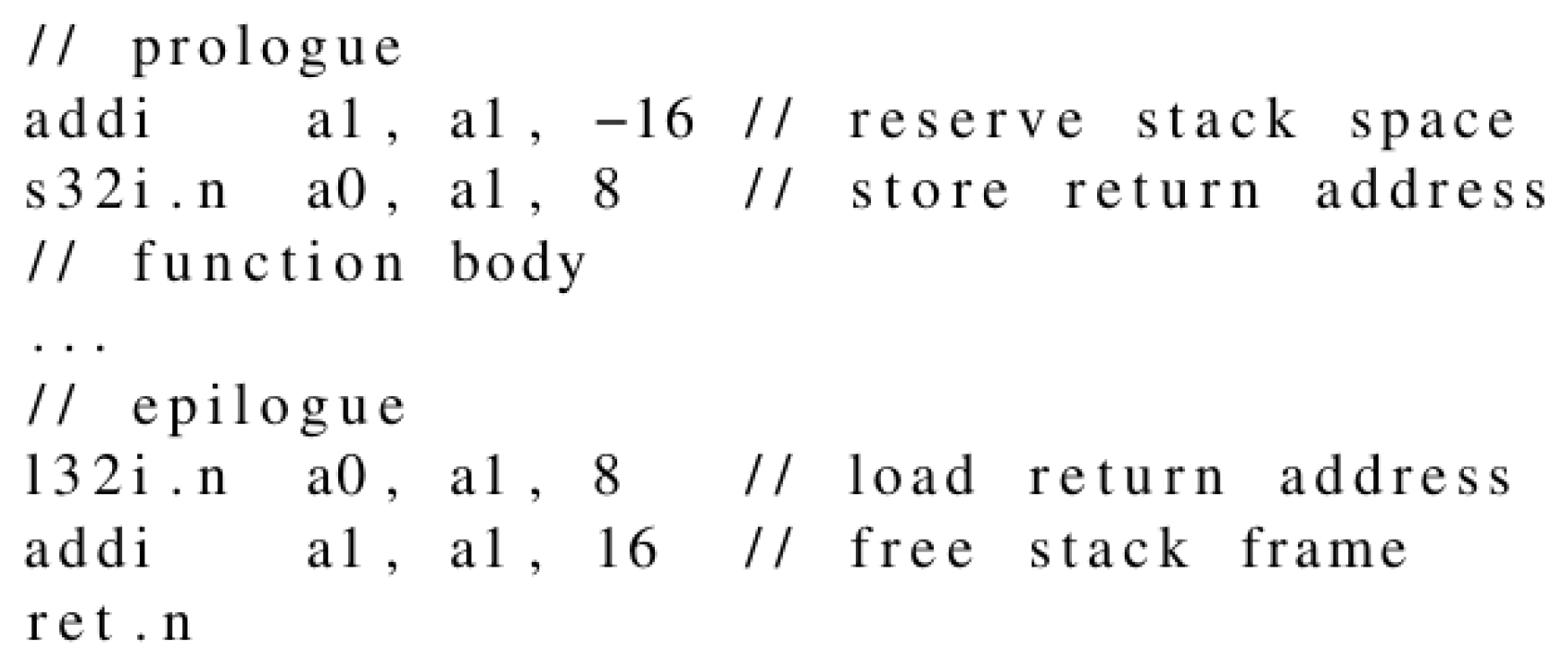

When a function is called, a place in the stack memory is reserved for the function’s local variables, return address, saved registers, and additional arguments if necessary. According to the Xtensa ISA, the stack pointer is stored in register a1 while the function return address is stored in register a0. The function prologue is responsible for allocating stack space for the callee function, it consists of 2 instructions: the first instruction reserves space in the stack for the function being called through decrementing the stack pointer (a1), and the second instruction stores the return address that is previously stored in a0 on the stack. Function arguments and local variables are also stored on the stack. The function epilogue, on the other hand, is responsible for restoring the stack to its original state before the function call and loading the return address back to register a0, hence it contains 2 instructions as well, the first one loads the return address value previously stored on the stack by the prologue, and the second instruction increments the stack pointer by the same value it was decremented by in the prologue to free the stack space, the function epilogues and prologues are shown in Listing 1.

Listing 1.

Function prologue and epilogue

Listing 1.

Function prologue and epilogue

By default, local variables declared in the function are stored on the stack beneath the return address; therefore, when an array is defined as a local variable, its memory is allocated on the stack. The buffer overflow vulnerability naturally lies in overflowing the array with inputs larger than its size, hence overwriting the return address with an address of a malicious function of our choice or to a gadget.

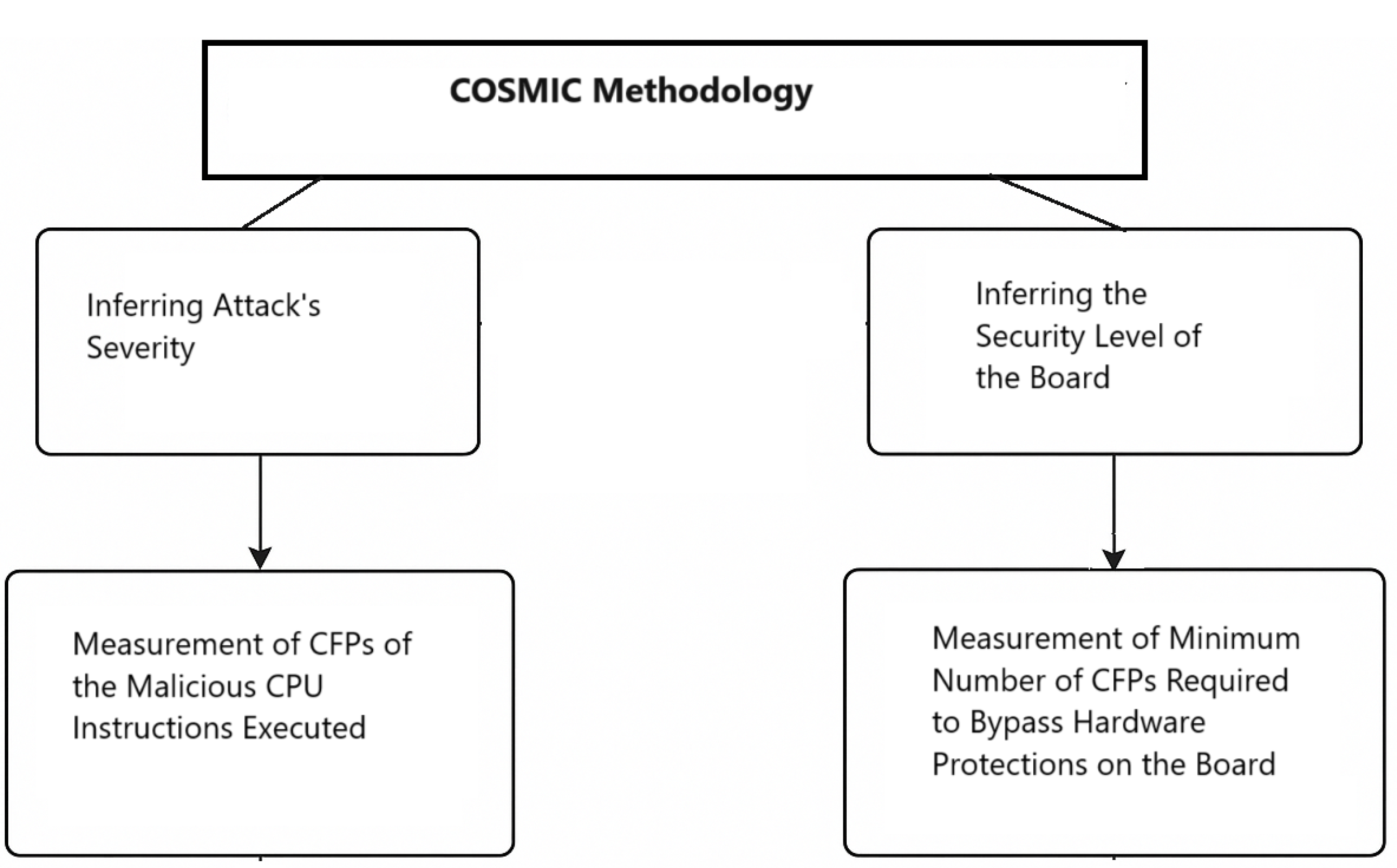

4.2. Proposed Methodology for COSMIC FSM Mapping

In this study, we propose an approach to measure the functional size of buffer-overflow attacks for the ESP boards as a proof of concept. The functional size of the attack is the size of assembly instructions executed maliciously by the attacker.

In addition, the hardware security of the board itself is analyzed using COSMIC CFPs; the rationale behind this is the fact that the attacker will need to execute additional malicious instructions to bypass protections. For instance, to bypass the stack canary, the attacker will first need to leak this canary, which corresponds to COSMIC reads, then proceed with the attack payload that enables them to execute malicious CPU instructions. Hence, executing the same payload on a secure board will result in a higher number of CFPs compared to execution on a board lacking hardware protections. To that end, the security level of a board is inferred from the minimum number of CFPs required to bypass security protections on the device.

Figure 2 depicts the proposed COSMIC methodology.

It is also important to note that buffer overflow attacks can be effectively mitigated by using secure functions when copying input into arrays. Our analysis takes these software mitigations into account.

For the purpose of our research, we conducted a buffer overflow attack on the ESP8266 board, and the functional size of the attack was obtained. In addition, the security level of the board is inferred based on the ease of conducting the attack and the existing protection mechanisms. This security level is then mapped to the CFPs, as previously discussed. Finally, a prototype tool is presented to analyze the vulnerability level of buffer overflow attacks with respect to two factors: the deployed code and the security level of the board.

4.3. Measurement Example

4.3.1. Exploiting Buffer-Overflow Vulnerability on ESP8266

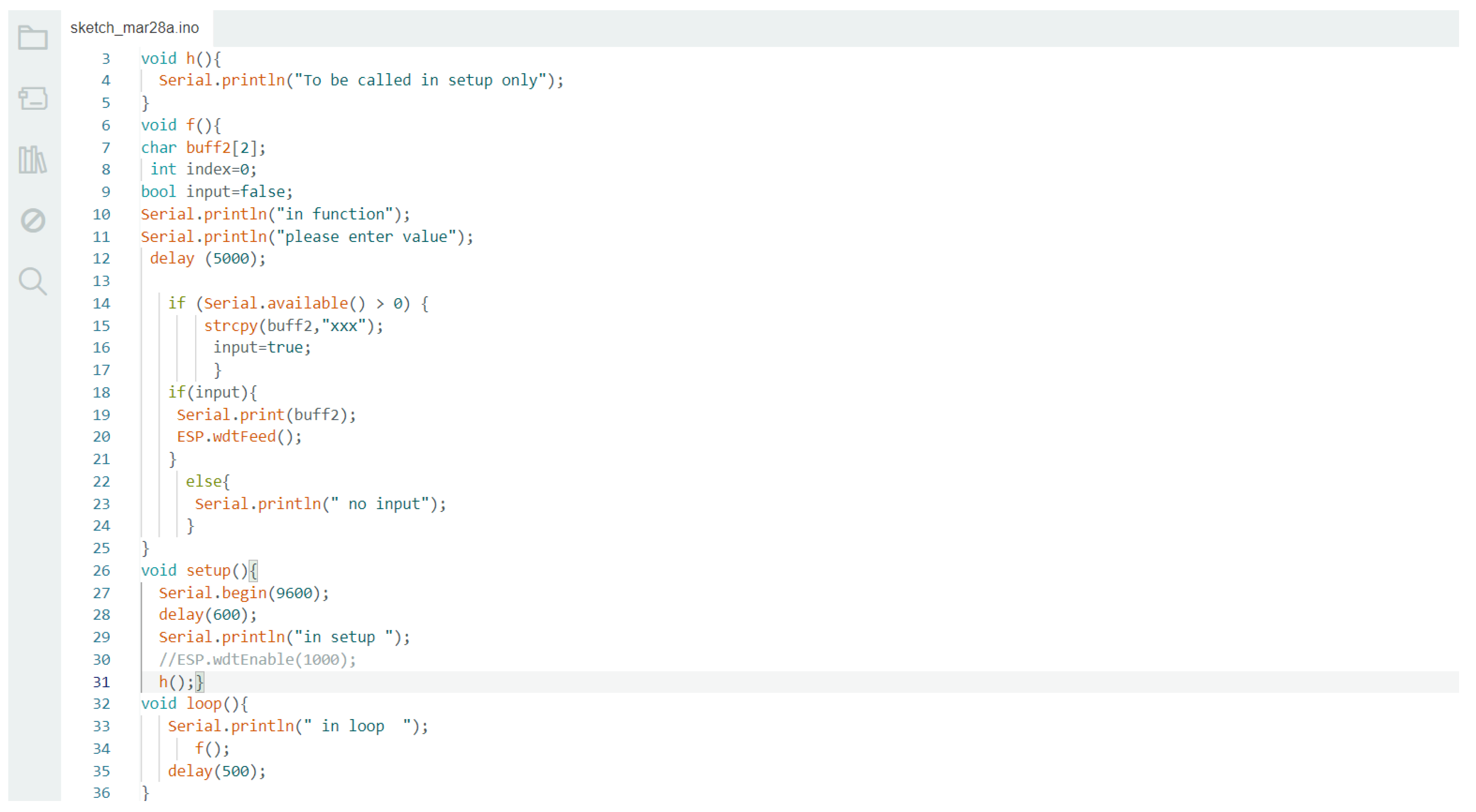

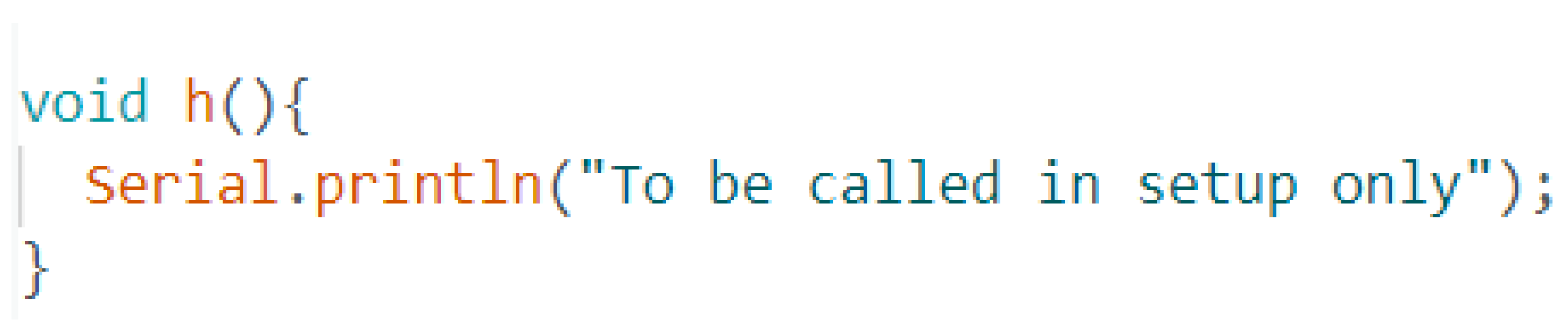

For the purposes of our research, we used a simple code snippet including a vulnerable function that calls the unsafe strcpy function as shown in Listing 2. Following this, the source code was disassembled using the Xtensa toolchain. Based on the assembly code, the size of the reserved stack space allocated for this function and the displacement of the stack pointer are obtained. Since the ESP8266 board lacks any security mechanisms to ensure the authenticity of the return address before executing the epilogue, exploiting the vulnerability was straightforward; it typically lies in overflowing the char buffer declared with characters till the return address is reached (N.B, the exact number of characters required to fill the buffer is deduced from analysis of the assembly previously obtained), afterwards, the desired return address or gadget was written in the payload.

Listing 2.

Vulnerable code snippet.

Listing 2.

Vulnerable code snippet.

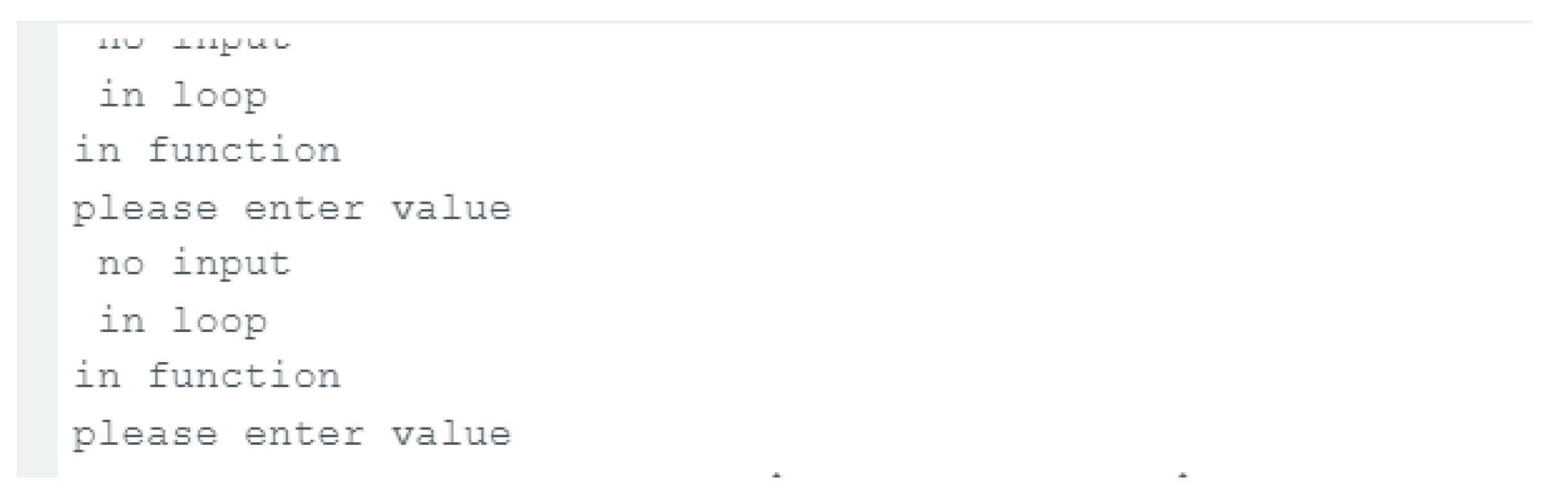

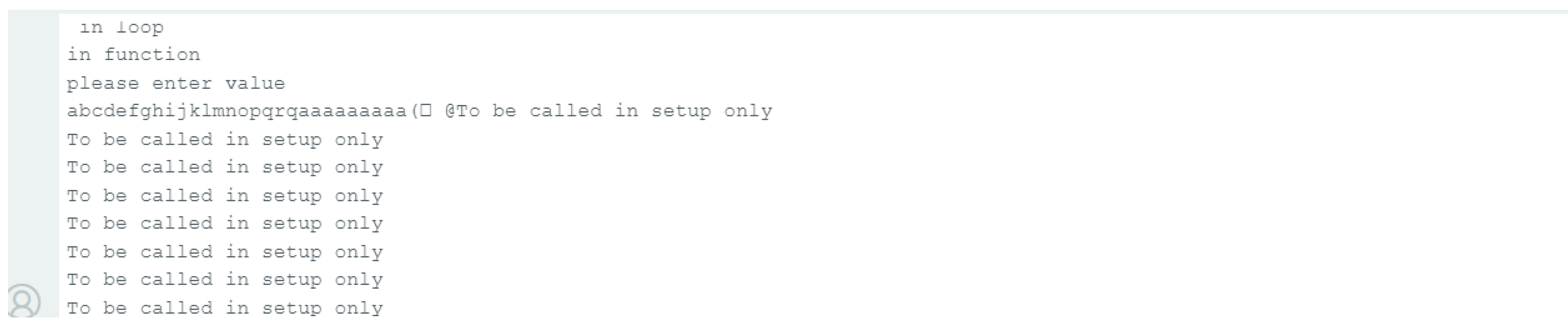

Under normal execution conditions, the program begins by initializing the serial monitor and then invokes the h() function, which outputs the message "To be called in setup only.". After this initial setup, the loop() function is executed, and the vulnerable function is called. Assuming normal execution with properly sized inputs or no data is written into the array, ensuring that no buffer overflow occurs, the code should return to the loop function again, and the process is repeated as shown in Listing 3.

Listing 3.

Normal code execution.

Listing 3.

Normal code execution.

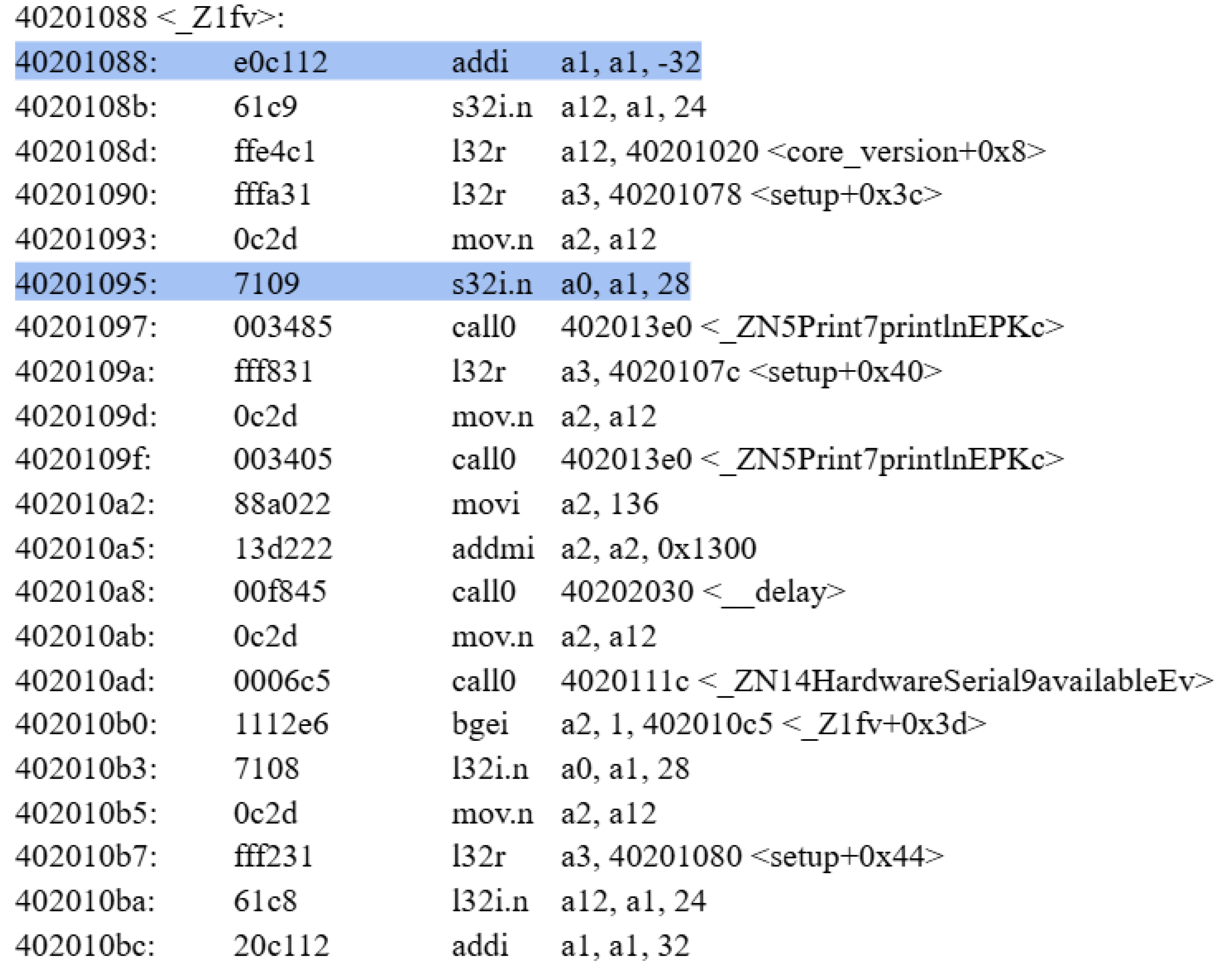

The first step lies in disassembling the code to deduce the number of characters needed to overflow the buffer to the return address of the function. Listing 4 shows the disassembly of the vulnerable function.

The 2 instructions highlighted in red show the function prologue. It can be easily inferred that 28 bytes are required to overflow the buffer. After successfully overflowing the buffer, the flow of the code was redirected to the h() function, which was called only once in the setup. Listing 5 shows the redirection of execution after overflowing the buffer

Listing 4.

Vulnerable function disassembly

Listing 4.

Vulnerable function disassembly

Listing 5.

Redirection of code flow

Listing 5.

Redirection of code flow

N.B. in our attack scenario, it is assumed that the attacker has access to the disassembly code deployed.

4.3.2. Measuring the Functional Size of the Attack

The functional size of the attack is the functional size of the CPU instructions executed by the attacker, as previously mentioned. For the purpose of our study, we adopt the mapping rules proposed in [

21]. Based on the redirection of the return address to function

h(), the CPU instructions executed maliciously by the attacker are the CPU instructions executed by function

h() that result in printing the sentence

“To be called in Set up only” on the Serial monitor.

Listing 6 shows the code for function

h().

The assembly instructions of the function are obtained from the disassembly files as follows:

fffd31 l32r a3, 4020101c <core_version+0x4> 1 Exit + 1 Read + Entry

fffd21 l32r a2, 40201020 <core_version+0x8> 1 Exit + 1 Read + Entry

fffd91 l32r a9, 40201024 <core_version+0xc> 1 Exit + 1 Read + Entry

0009a0 jx a9 1 Exit + Entry

fe87d7 bany a7, a13, 40201036 <_Z1hv+0xe> 1 Exit + 3 Entry

3f .byte 0x3f

1028 l32i.n a2, a0, 4 1 Exit + 1 Read + 2 Entry

20 .byte 0x20

40 .byte 0x40

Hence, the number of CFPs of the assembly instruction as per the rules mentioned in [

21] is 19 CFPs; the detailed analysis of the output is shown in

Table 3.

4.3.3. Board Security Level Inference Using COSMIC

The Security level of the board is inferred from the CFPs required by the attacker to bypass protections. These protections are typically protections implemented on the Hardware level, such as Stack Canaries or Data Execution Prevention (i.e., preventing the CPU from executing instructions placed on the stack). Since the ESP8266 board lacks any of the mentioned security features, the attack was carried out by directly overwriting the return address, without the need to bypass any protections, hence, the security level of the board is evaluated as 0 CFPs referring to that no data group movements were required by the attacker to bypass protections; the attacker directly redirected the code flow by overwriting the return address.

N.B: Measurement of CFPs of executed malicious CPU instructions merely infers the size of the attack .However , measuring the CFPs required to bypass protections to successfully carry out the attack and execute these malicious instructions reflects the security level of the board based on integrated HW protections.

5. The Prototype Tool Proposed

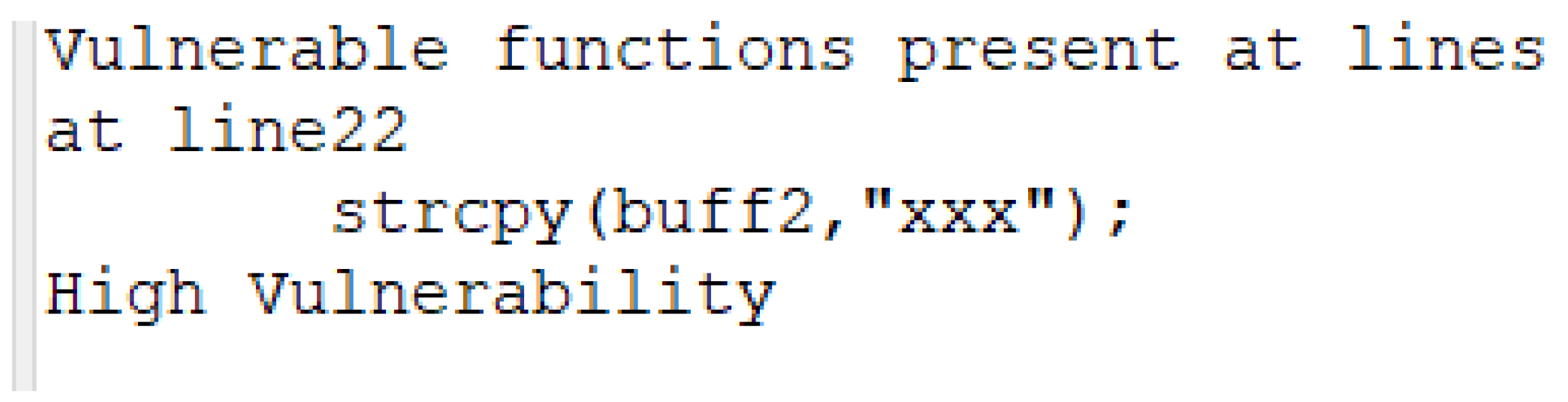

A tool is proposed to assess the current vulnerability level to buffer overflow attacks. The assessment is based on 2 metrics: the first metric is the presence of unsafe functions in the code deployed, the second metric is the security level of the board on which the code is deployed.

5.1. Tool Main Components

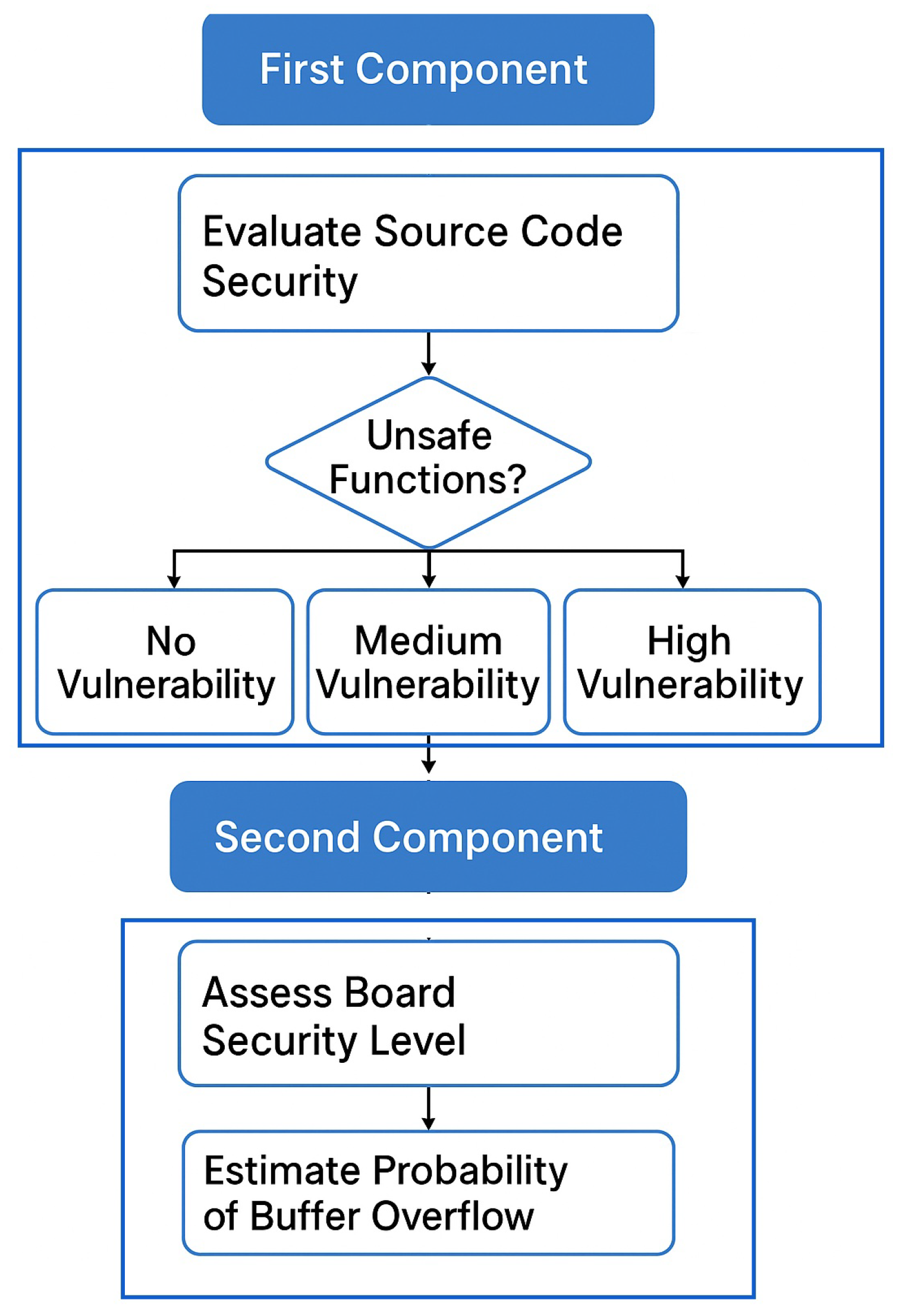

The tool is composed of two main components. The first component focuses on evaluating the security of the deployed source code by scanning for the presence of unsafe functions. Based on its analysis, the tool classifies the code into three categories:

Secure code that lacks any unsafe functions, resulting in “No Vulnerability”.

Code including functions that result in non-null termination of strings, although these functions do not instantly exploit the buffer overflow vulnerability, the vulnerability might be exploited later; this category is assigned the value “Medium Vulnerability”.

Code including unsafe functions that exploit the buffer overflow vulnerability, assuming the weak security of the board on which the code is deployed, this category is assigned the value “High Vulnerability”.

The analysis is done through checking the source code line by line for the presence of the common unsafe functions that are stored by the tool.

The second part checks the security level of the board. Based on the security level of the board and the output from part 1, the final probability of buffer overflow is obtained.

Figure 3 shows the 2 main components of the tool.

The source code is initially fed as input to the tool, the tool analyzes the code line by line to check for the presence of unsafe functions such as strcpy(). In case of the presence of unsafe functions, the tool checks the security level of the board that is previously stored based on the COSMIC mapping discussed to obtain the final vulnerability level. Meanwhile, in case the deployed software is secure, then the output vulnerability level is classified as “No Vulnerability” since buffer-overflow attacks arise mainly from the presence of unsafe functions that were not present in the mentioned scenario.

The tool is implemented in Java. In addition, the mapping of the board security level to COSMIC is stored in a hash map data structure. Furthermore, the tool maintains a list of unsafe functions in an ArrayList, which it iterates through for each line of code to check for the presence of these functions. The vulnerability level obtained is assessed based on the previously mentioned parameters.

The tool is currently limited to ESP8266; for future versions, other ESP boards should be considered. In addition, another important metric should be considered, which is the operational mode of the board, specifically, whether it is configured in development mode or release mode, extracting the firmware using tools such as esptool.py, hence reducing the vulnerability level.

5.2. Tool Validation

5.2.1. Test Cases Scenarios

Several code snippets were fed to the tool to validate the output obtained. The following test cases were included in the code snippets-

A buffer overflow vulnerability resulted from the unsafe use of the “strcpy” function when the size of the source array exceeds that of the destination buffer.

Absence of buffer overflow vulnerability when using the same “strcpy” function and validating the size of the source array.

A buffer overflow vulnerability resulted from the unsafe use of the “strncpy” function when the number of characters to copy is greater than the size of the destination array.

Absence of buffer overflow vulnerability when using the same “strncpy” function and validating the size of the source array, or when the number of bytes to copy is less than the size of the destination array.

There is a potential buffer overflow vulnerability when using “strncpy”, and the size of the destination is equal to the number of characters copied; hence, the string is not NULL-terminated.

Although the mentioned scenario does not exploit the vulnerability instantly, the subsequent use of other functions like strlen() or printf() might potentially exploit the vulnerability as these functions rely on the presence of the null character, hence incorrect size determination of the destination array or unintended reading beyond its bounds are among the potential implications.

The same scenarios were applied to the “memcopy” and “memove” functions.

Absence of a buffer-overflow vulnerability due to the usage of safe functions such as “strlcpy” or “memcopy_s”, or memmove_s”.

Code snippets that do not involve any string copying functions.

The code was deployed on the ESP8266 that lacks any security protection, hence the output for the test cases was categorized as follows:-

“High Vulnerability” for the test cases that result in exploiting the buffer overflow vulnerability.

“Medium Vulnerability” for the test cases that have a prospective buffer overflow vulnerability.

“No vulnerability” when safe functions are used or proper input validation is performed. The same applies to code snippets that do not involve any string-copying functions.

5.2.2. Test Cases Output

The vulnerable code snippet in

Listing 2, which was used to exploit the buffer overflow vulnerability, was provided as input to the tool. The tool successfully identified the presence of the vulnerable

strcpy() function as well as the line of code where this function was called. Furthermore, the vulnerability level was classified as high.

Listing 7 illustrates the output of the tool after the vulnerable code was provided as input.

The same code snippet was provided as input to the tool, with the vulnerable strcpy() function replaced by the safer strlcpy() function. The tool successfully reported ’No Vulnerability’ in this case.

-

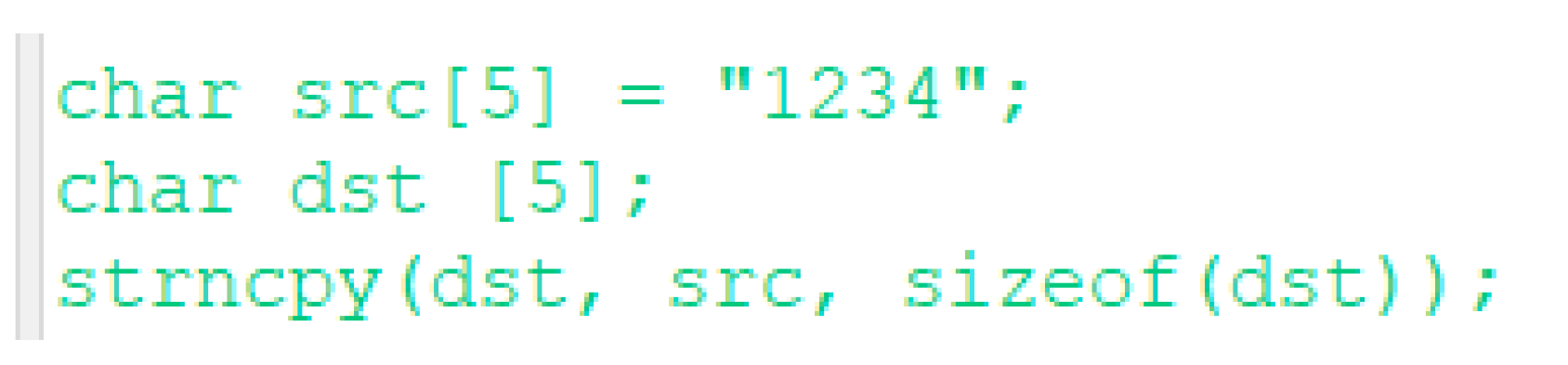

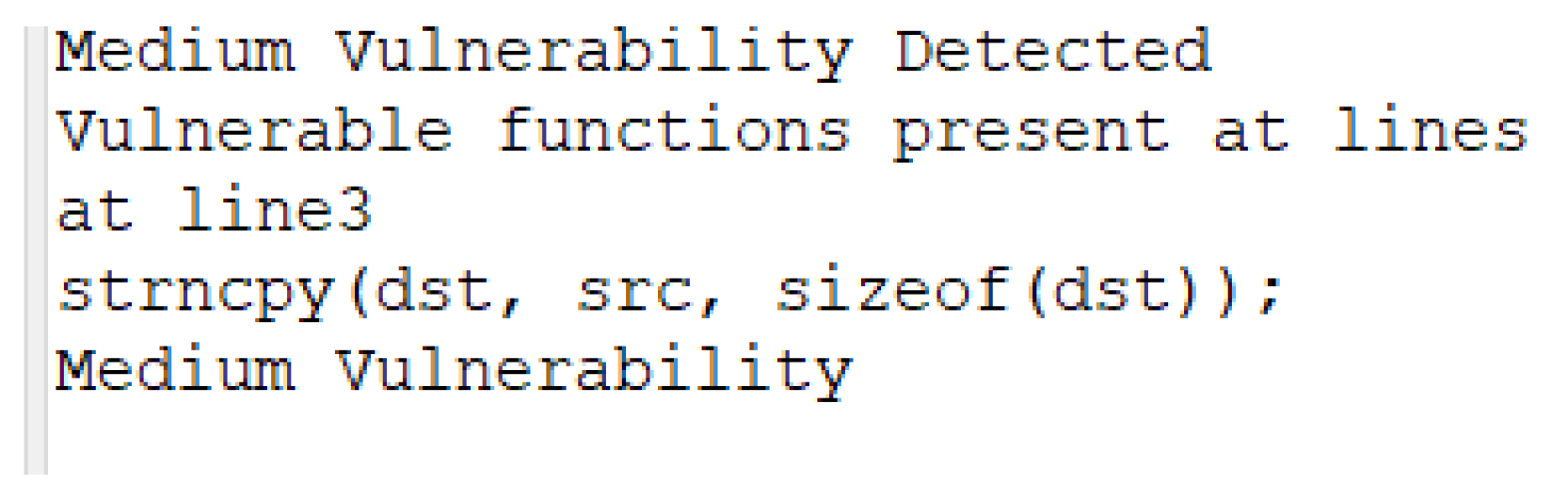

The following code snippet, which results in a prospective vulnerability, was fed into the tool, and the tool successfully output “Medium Vulnerability”. Listing 8 shows the vulnerable code snippet fed to the tool.

The tool correctly identified the vulnerability alongside the line of code that induced the vulnerability. Listing 9 shows the tool output.

Upon replacing the

strncpy(dst, src, sizeof(dst)) with

strncpy(dst, src, sizeof(dst)-1) and placing

NULL in

dst[4], the tool has successfully detected “No Vulnerability” as shown in

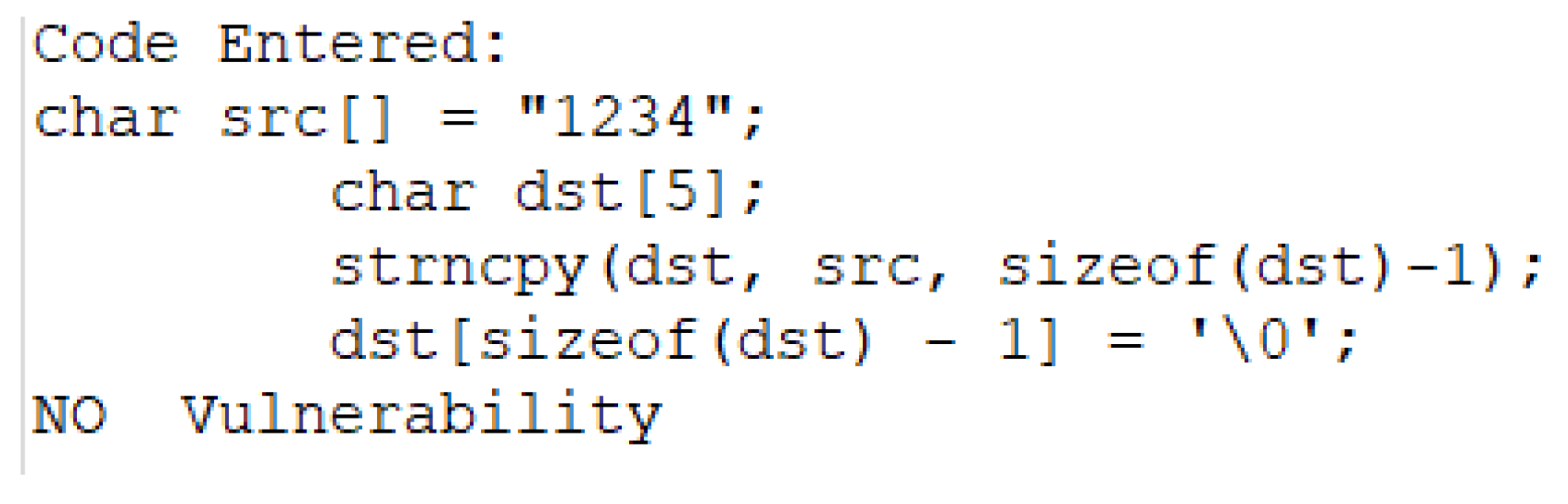

Listing 10.

Listing 8.

Vulnerable code snippet

Listing 8.

Vulnerable code snippet

Listing 10.

Updated Output.

Listing 10.

Updated Output.

A simple code snippet that prints the word “Hello World” on the serial monitor was fed to the tool. The tool has successfully detected “No Vulnerability” since the code lacks any functions involving the copying of Strings.

Listing 11 shows the output of the tool.

Table 4 summarizes the classification of the test cases and the tool output for each test case.

6. Discussion

This study proposed a novel approach for assessing memory-related vulnerabilities in IoT edge devices by integrating COSMIC Functional Size Measurement (FSM) at the hardware level. The approach quantifies both the functional size of attacks and the inherent security level of hardware platforms, using COSMIC FSM to provide objective, repeatable evaluations. A prototype tool was developed to automate vulnerability assessments for buffer overflow attacks, demonstrated on ESP8266 boards. The proposed approach contributes to developing systematic methods for securing IoT Edge devices.

The experimental results confirm that COSMIC FSM can effectively model the functional footprint of memory-based attacks, capturing both the functional size of malicious instruction execution and the additional overhead required to bypass hardware protections. Notably, the proposed security-level metric, expressed in COSMIC Function Points (CFPs), provides a quantitative measure of a device’s resistance to such attacks, based on the number of required data movements.

The current prototype tool successfully identified vulnerabilities in source code by detecting unsafe functions and correlating this information with the board’s hardware-level protections. The classification of vulnerability levels into High, Medium, or None enables developers to make informed decisions during software development and deployment, fostering proactive mitigation strategies.

Despite these promising results, certain limitations should be acknowledged. The tool presently supports only ESP8266 boards, which lack advanced security mechanisms such as stack canaries, memory isolation, or execution prevention technologies. Consequently, the COSMIC-based security level for this board is minimal, emphasizing the need for extending the approach to platforms with more robust hardware defenses.

Furthermore, the prototype’s code analysis focuses primarily on detecting a predefined set of unsafe string handling functions. Expanding this capability to incorporate more comprehensive code parsing, including dynamic memory management, user-defined functions, and indirect vulnerabilities, would enhance the tool’s accuracy and applicability.

Future work will focus on generalizing the COSMIC-based assessment methodology to other IoT platforms, particularly devices equipped with hardware-level countermeasures. Additionally, integrating Natural Language Processing (NLP) techniques to automate vulnerability detection across a broader set of libraries and codebases will improve the tool’s scalability. Beyond buffer overflow attacks, the methodology may also be extended to other classes of memory-related vulnerabilities, such as use-after-free, heap corruption, or unauthorized memory access.

7. Conclusions

The increasing reliance on IoT edge devices for data processing and communication has amplified concerns regarding hardware security, particularly memory-related vulnerabilities such as buffer overflow attacks. This paper introduced a novel approach to quantifying and assessing these vulnerabilities by applying COSMIC Functional Size Measurement (FSM) at the hardware level. By leveraging COSMIC size, the approach enables objective, repeatable evaluations of both the functional size of memory-based attacks and the intrinsic security level of IoT platforms.

As a proof of concept, the methodology was applied to ESP8266 boards, where a prototype tool was developed to analyze source code for unsafe functions and assess device vulnerability levels based on COSMIC Function Points (CFPs). The experimental results demonstrated the feasibility of using FSM to model attack severity and to infer the additional effort required to bypass existing hardware protections.

The proposed COSMIC-based assessment provides an important step toward standardizing security evaluation for IoT edge devices, particularly in environments where traditional security mechanisms may be limited or absent.

Future research will focus on extending this approach to a broader range of IoT hardware platforms, including those with advanced security features such as stack canaries, memory protection units, and Trusted Execution Environments. Additionally, the prototype tool will be expanded to incorporate a more comprehensive set of vulnerability patterns, integrating advanced analysis techniques such as machine learning and Natural Language Processing to enhance detection accuracy.

Beyond buffer overflows, the approach proposed holds potential for evaluating other memory-related vulnerabilities and facilitating quantifiable assessments of IoT security. Ultimately, integrating COSMIC FSM into security frameworks may contribute to the development of more resilient IoT systems, providing developers with a standardized measurement method to guide secure design and deployment practices.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.S. and H.S.; methodology, S.S. and H.S.; software, S.S., H.S., P.L., and M.G.; validation, S.S., H.S., P.L., and M.G.; formal analysis, S.S., H.S., P.L., and M.G.; investigation, S.S., H.S., P.L., and M.G.; resources, S.S., H.S., P.L., and M.G.; data curation, S.S., H.S., P.L., and M.G.; writing—original draft preparation, S.S. and H.S.; writing—review and editing, S.S., H.S., P.L., and M.G.; visualization, S.S., H.S., P.L., and M.G.; supervision, H.S., P.L., and M.G.; project administration, H.S. and M.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

In this section you can acknowledge any support given which is not covered by the author contribution or funding sections. This may include administrative and technical support, or donations in kind (e.g., materials used for experiments). Where GenAI has been used for purposes such as generating text, data, or graphics, or for study design, data collection, analysis, or interpretation of data, please add “During the preparation of this manuscript/study, the author(s) used [tool name, version information] for the purposes of [description of use]. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.”

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| IoT |

Internet of Things |

| IIoT |

Industrial IoT |

| DoS |

Denial of Service |

| DDoS |

Distributed Denial of Service |

| CVSS |

Common Vulnerability Scoring System |

| COSMIC |

Common Software Measurement International Consortium |

| FSM |

Functional Size Measurement |

| CFP |

COSMIC Function Points |

| ISA |

Instruction Set Architecture |

| RPL |

Routing Protocol for Low-Power and Lossy Networks |

| MQTT |

Message Queuing Telemetry Transport |

| APT |

Advanced Persistent Threat |

| IC |

Integrated Circuit |

| TRNG |

True Random Number Generator |

| OTP |

One-Time Programmable |

| SE |

Secure Element |

| TEE |

Trusted Execution Environment |

| EM |

Electromagnetic |

| DFA |

Differential Fault Analysis |

| PC |

Program Counter |

| SPA |

Simple Power Analysis |

| DPA |

Differential Power Analysis |

| CPU |

Central Processing Unit |

| ROP |

Return-Oriented Programming |

| OTA |

Over-The-Air |

| AV |

Attack Vector |

| AC |

Attack Complexity |

| PR |

Privileges Required |

| UI |

User Interaction |

| AR |

Attack Requirements |

| SC |

Subsequent System Confidentiality |

| SI |

Subsequent System Integrity |

| SA |

Subsequent System Availability |

| NIST |

National Institute of Standards and Technology |

| CVE |

Common Vulnerabilities and Exposures |

| SVM |

Support Vector Machine |

| SOA |

Service-Oriented Architectures |

| FUR |

Functional User Requirement |

| ECU |

Electronic Control Unit |

| NFR |

Non-Functional Requirements |

| NLP |

Natural Language Processing |

References

- Tyagi, N.; Bhushan, B. Demystifying the Role of Natural Language Processing (NLP) in Smart City Applications: Background, Motivation, Recent Advances, and Future Research Directions. Wireless Pers. Commun. 2023, 130, 857–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, A.-e.A.; Mashhour, M.; Salama, A.S.; Shoitan, R.; Shaban, H. Development of an Intelligent Personal Assistant System Based on IoT for People with Disabilities. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshdadi, A.A. Cyber-physical system with IoT-based smart vehicles. Soft Comput. 2021, 25, 12261–12273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderón, D.; Folgado, F.J.; González, I.; Calderón, A.J. Implementation and Experimental Application of Industrial IoT Architecture Using Automation and IoT Hardware/Software. Sensors 2024, 24, 8074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surantha, N.; Atmaja, P.; David, M.; Wicaksono, M. A Review of Wearable Internet-of-Things Device for Healthcare. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2021, 179, 936–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dell Technologies. Internet of Things and Data Placement. 2024. Available online: https://infohub.delltechnologies.com/en-us/l/edge-to-core-and-the-internet-of-things-2/internet-of-things-and-data-placement/ (accessed on 11 June 2025).

- Rehman, S.; Manickam, S.; Firdous, N. Impact of DoS/DDoS Attacks in IoT Environment: A Study. In AIP Conference Proceedings, 2023, 020020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caballero-Gil, C.; Álvarez, R.; Hernández-Goya, C.; Pérez, D. Research on Smart-Lock Cybersecurity and Vulnerabilities. Wirel. Netw. 2024, 30, 5905–5917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cloudflare. Mirai Botnet. Available online: https://www.cloudflare.com/en-gb/learning/ddos/glossary/mirai-botnet/ (accessed on 11 June 2025).

- NHS Digital. Cyber Alert—CC-2557. 2018. Available online: https://digital.nhs.uk/cyber-alerts/2018/cc-2557 (accessed on 11 June 2025).

- Bellay, J.; Forte, D.; Martin, R.; Taylor, C. Hardware Vulnerability Description, Sharing and Reporting: Challenges and Opportunities. GOMACTech, 2020. Available online: https://par.nsf.gov/biblio/10237521 (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- National Vulnerability Database (NVD). CVSS Metrics. Available online: https://nvd.nist.gov/vuln-metrics/cvss (accessed on 11 June 2025).

- Anand, P.; Singh, Y.; Selwal, A.; Singh, P.K.; Ghafoor, K.Z. ivqfiot: An Intelligent Vulnerability Quantification Framework for Scoring Internet of Things Vulnerabilities. Expert Syst. 2021, 39, e12829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massaro, V.G.; Capacci, L.; Montanari, R. Towards Context-Aware Risk Assessment Scoring System for IoT/IIoT Devices. In Proceedings of the ITASEC; 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Ur-Rehman, A.; Gondal, I.; Kamruzzaman, J.; Jolfaei, A. Vulnerability Modelling for Hybrid IT Systems. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE International Conference on Industrial Technology (ICIT); 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- COSMIC. Functional Size Measurement—Method Overview. Available online: https://cosmic-sizing.org/ (accessed on 11 June 2025).

- Salem, S.; Soubra, H. Functional Size Measurement Automation for IoT Edge Devices. In Proceedings of the IWSM-Mensura 2024; CEUR Workshop Proceedings, Volume 3543; CEUR-WS.org: Aachen, Germany; paper 13. Available online: https: //ceur-ws.org/Vol-/paper13.pdf (accessed on 11 June 2025), 2024. Available online: https://ceur-ws.org/Vol-3543/paper13.pdf (accessed on 11 June 2025).

- Salem, S.; Soubra, H. Using NLP for Functional Size Measurement of IoT Devices. In *Proceedings of the 2023 Eleventh International Conference on Intelligent Computing and Information Systems (ICICIS)*, Cairo, Egypt, ; pp. 321–327. 16–18 December. [CrossRef]

- Soubra, H.; Jacot, L.; Lemaire, S. Manual and Automated Functional Size Measurement of an Aerospace Realtime Embedded System: A Case Study Based on SCADE and on COSMIC ISO 19761. 2015.

- Soubra, H.; Abran, A.; Sehit, M. Functional Size Measurement for Processor Load Estimation in AUTOSAR. In Lecture Notes in Business Information Processing; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; Volume 230, pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Soubra, H.; Abufrikha, Y.; Abran, A. Towards Universal COSMIC Size Measurement Automation. In Proceedings of the IWSM-Mensura; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Darwish, A.; Soubra, H. COSMIC Functional Size of ARM Assembly Programs. In Proceedings of the IWSM-Mensura; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Krishna, R.R.; Priyadarshini, A.; Jha, A.V.; Appasani, B.; Srinivasulu, A.; Bizon, N. State-of-the-Art Review on IoT Threats and Attacks: Taxonomy, Challenges and Solutions. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, J.; Sahay, S. Modern Hardware Security: A Review of Attacks and Countermeasures. 2025. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2501.04394 (accessed on 11 June 2025).

- Zhu, W.T.; Zhou, J.; Deng, R.H.; Bao, F. Detecting Node Replication Attacks in Wireless Sensor Networks: A Survey. J. Netw. Comput. Appl. 2012, 35, 1022–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makhdoom, I.; Abolhasan, M.; Lipman, J.; Liu, R.P.; Ni, W. Anatomy of Threats to the Internet of Things. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2018, 21, 1636–1675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanam, S.; Ahmedy, I.B.; Idris, M.Y.I.; Jaward, M.H.; Sabri, A.Q.B.M. A Survey of Security Challenges, Attacks Taxonomy and Advanced Countermeasures in the Internet of Things. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 219709–219743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauro, C.; Pallavi, K.; Rabbani, M.M.; Ranise, S. Attestation-Enabled Secure and Scalable Routing Protocol for IoT Networks. Ad Hoc Netw. 2020, 98, 102054. [Google Scholar]

- OWASP. Session Hijacking Attack. Available online: https://owasp.org/www-community/attacks/Session_hijacking_attack (accessed on 11 June 2025).

- IBM. SYN Flood Attack Detection and Prevention. Available online: https://www.ibm.com/support/pages/syn-flood-attack-detection-and-prevention (accessed on 11 June 2025).

- Roldán-Gómez, J.; Carrillo-Mondéjar, J.; Castelo Gómez, J.M.; Ruiz-Villafranca, S. Security Analysis of the MQTT-SN Protocol for the Internet of Things. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 10991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayasinghe, K.; Poravi, G. A Survey of Attack Instances of Cryptojacking Targeting Cloud Infrastructure. In Proceedings of the 2020 2nd Asia Pacific Information Technology Conference (APIT ’20), ACM, New York, NY, USA; 2020; pp. 100–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, B.; Melo, L.; de Sousa Junior, R. A Study on APT in IoT Networks. In Proceedings of the 2021 International Conference on Security and Cryptography (SECRYPT); pp. 160–164. [CrossRef]

- Rehman, I.U. Facebook-Cambridge Analytica Data Harvesting: What You Need to Know. Library Philosophy and Practice (e-journal), 2019, 249.

- Noman, H.A.; Abu-Sharkh, O.M.F. Code Injection Attacks in Wireless-Based Internet of Things (IoT): A Comprehensive Review and Practical Implementations. Sensors 2023, 23, 6067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Zhang, X.; Ming, J.; Chen, T.; Wang, C.; Niu, W. Resetting Your Password Is Vulnerable: A Security Study of Common SMS-Based Authentication in IoT Devices. Wirel. Commun. Mob. Comput. 2018, 2018, 7849065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasi, T.; Lashkari, A.H.; Lu, R.; Xiong, P.; Iqbal, S. A Comprehensive Survey on IoT Attacks: Taxonomy, Detection Mechanisms and Challenges. J. Inf. Intell. 2024, 2, 455–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sengupta, J.; Ruj, S.; Das Bit, S. A Comprehensive Survey on Attacks, Security Issues and Blockchain Solutions for IoT and IIoT. J. Netw. Comput. Appl. 2020, 149, 102481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, Y.; Sengupta, S. A Survey on Classification of Cyber-Attacks on IoT and IIoT Devices. In Proceedings of the 2020 11th IEEE Annual Ubiquitous Computing, Electronics & Mobile Communication Conference (UEMCON), New York, NY, USA; 2020; pp. 406–413. [Google Scholar]

- Victor, P.; Lashkari, A.H.; Lu, R.; Sasi, T.; Xiong, P.; Iqbal, S. IoT Malware: An Attribute-Based Taxonomy, Detection Mechanisms and Challenges. Peer-to-Peer Netw. Appl. 2023, 16, 1380–1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OWASP. Buffer Overflow Attack. Available online: https://owasp.org/www-community/attacks/Buffer_overflow_attack (accessed on 11 June 2025).

- IBM. What is Encryption? Available online: https://www.ibm.com/think/topics/encryption (accessed on 11 June 2025).

- OWASP. Cryptanalysis. Available online: https://owasp.org/www-community/attacks/Cryptanalysis (accessed on 11 June 2025).

- Ling, Z.; Luo, J.; Xu, Y.; Gao, C.; Wu, K.; Fu, X. Security Vulnerabilities of Internet of Things: A Case Study of the Smart Plug System. IEEE Internet Things J. 2017, 4, 1899–1909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cirne, A.; Sousa, P.R.; Resende, J.S.; Antunes, L. Hardware Security for Internet of Things Identity Assurance. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2024, 26, 1041–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rekoff, M.G. On Reverse Engineering. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. 1985, SMC-15, 244–252.

- Torrance, R.; James, D. The State-of-the-Art in IC Reverse Engineering. In *Cryptographic Hardware and Embedded Systems—CHES 2009*; Clavier, C., Gaj, K., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009; pp. 363–381. [Google Scholar]

- Boneh, D.; DeMillo, R.A.; Lipton, R.J. On the Importance of Checking Cryptographic Protocols for Faults. In *Proceedings of the 1997 International Conference on the Theory and Applications of Cryptographic Techniques*; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1997; pp. 37–51. [Google Scholar]

- Biham, E.; Shamir, A. Differential Fault Analysis of Secret Key Cryptosystems. In *Advances in Cryptology—CRYPTO’97*; Koblitz, N., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1997; Volume 1294, pp. 513–525. [Google Scholar]

- Yarom, Y.; Falkner, K. Flush+Reload: A High Resolution, Low Noise, L3 Cache Side-Channel Attack. *IACR Cryptol. ePrint Arch.* 2014, 2013, 448. [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein, D.J. Cache-Timing Attacks on AES. *University of Illinois at Chicago*, 2005. Available online: https://cr.yp.to/antiforgery/cachetiming-20050414.pdf (accessed on 11 June 2025).

- Kocher, P.; Horn, J.; Fogh, A.; Genkin, D.; Gruss, D.; Haas, W.; Hamburg, M.; Lipp, M.; Mangard, S.; Prescher, T.; Schwarz, M.; Yarom, Y. Spectre Attacks: Exploiting Speculative Execution. *Commun. ACM* 2020, 63, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delvaux, J.; Mune, C.; Romero, M.; Timmers, N. Breaking Espressif ESP32 V3: Program Counter Control with Computed Values Using Fault Injection. In *Proceedings of the 18th USENIX Workshop on Offensive Technologies (WOOT ’24)*; USENIX Association: Boston, MA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Courk. ESP32-C3/C6 Fault Injection. 2024. Available online: https://courk.cc/esp32-c3-c6-fault-injection (accessed on 11 June 2025).

- Kocher, P.; Jaffe, J.; Jun, B. Differential Power Analysis. In *Advances in Cryptology – CRYPTO’99*; Wiener, M., Ed.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1999; Volume 1666, pp. 388–397. [Google Scholar]

- Dhem, J.F.; Koeune, F.; Leroux, P.A.; Mestre, P.; Quisquater, J.J.; Willems, J.L. A.; Mestre, P.; Quisquater, J.J.; Willems, J.L. A Practical Implementation of the Timing Attack. In *Smart Card Research and Advanced Applications*; Gollmann, D., Ed.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1998; Quisquater, J.J.; pp. 167–182. [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein, D.J. Cache-Timing Attacks on AES; University of Illinois at Chicago: Chicago, IL, USA, 2005; Available online: https://cr.yp.to/antiforgery/cachetiming-20050414.pdf (accessed on 11 June 2025).

- Ronen, E.; Shamir, A.; Weingarten, A.O.; O’Flynn, C. IoT Goes Nuclear: Creating a ZigBee Chain Reaction. In *Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (SP)*, San Jose, CA, USA, 22–26 May 2017; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 195–212. [Google Scholar]

- Van Bulck, J.; Piessens, F.; Strackx, R. Nemesis: Studying Microarchitectural Timing Leaks in Rudimentary CPU Interrupt Logic. In *Proceedings of the 2018 ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security (CCS ’18)*; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 178–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salehi, M.; De Borger, G.; Hughes, D.; Crispo, B. NemesisGuard: Mitigating Interrupt Latency Side Channel Attacks with Static Binary Rewriting. *Computer Networks* **2022**, *205*, 108744. [CrossRef]