Submitted:

10 July 2025

Posted:

17 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

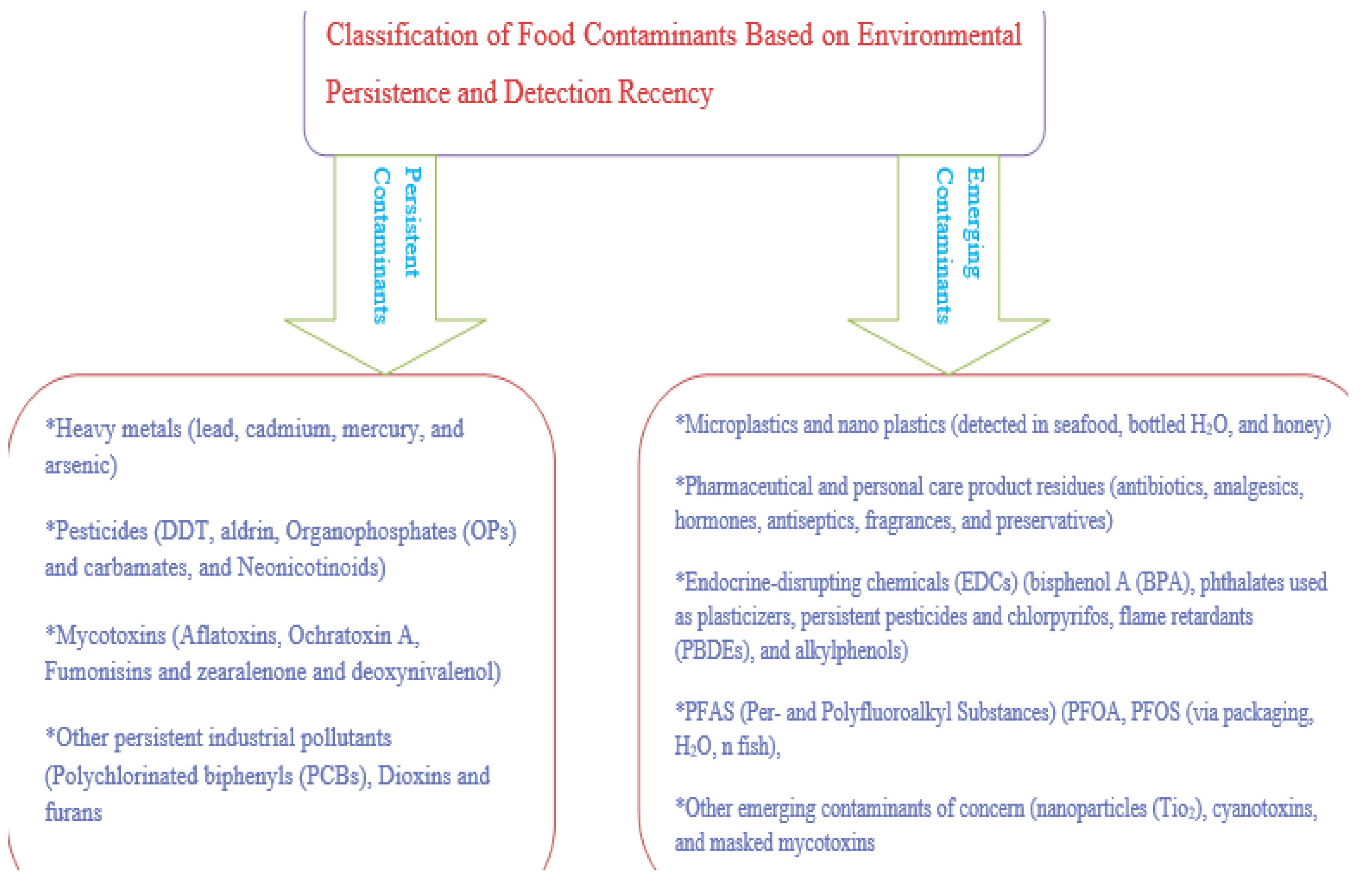

3. Classification of Food Contaminants Based on Environmental Persistence and Detection Recency

3.2. Emerging Contaminants

4. Chemical Structure, Persistence, and Physicochemical Properties

5. Toxicokinetic and Bioaccumulation

| Category | Contaminant Class | Examples | Primary Sources | Toxicological Effects | Persistence/Bioaccumulation |

| Persistent contaminants | Heavy Metals [10,11,14] | Lead (Pb), Cadmium (Cd), Mercury (Hg), Arsenic (As), Chromium, Nickel, Copper | Industrial emissions, fertilizers, mining, water contamination | Neurotoxicity, nephrotoxicity, carcinogenicity, developmental toxicity | Highly persistent, bioaccumulate in soils and food chains |

| Pesticides [16,18,19] | Organochlorines (DDT), Organophosphates, Carbamates, Neonicotinoids, Glyphosate | Agricultural application, residual soil contamination | Endocrine disruption, neurotoxicity, reproductive and developmental toxicity | Varies by type; OCPs highly persistent; OPs less persistent but acutely toxic | |

| Mycotoxins [22,24] | Aflatoxins, Ochratoxin A, Fumonisins, Zearalenone, Deoxynivalenol | Mold growth in cereals, nuts, stored grains | Hepatotoxicity, nephrotoxicity, immunosuppression, carcinogenicity | Stable during processing; bio accumulative in some cases | |

| Industrial Pollutants [29,30] | PCBs, Dioxins, Furans, PAHs, PFAS | Electrical waste, combustion, packaging, industrial effluents | Cancer, immune dysfunction, endocrine and reproductive toxicity | High environmental and biological persistence | |

| Emerging contaminants | Microplastics & Nano plastics [33,35,36] | Polyethylene, Polypropylene, Polystyrene | Breakdown of plastic waste, packaging, textiles | Inflammation, oxidative stress, gut microbiota disruption | Physically persistent, adsorb other pollutants, bio accumulative |

| Pharmaceutical & Personal Care Products (PPCPs) [40,41] | Antibiotics, Hormones, Analgesics, Antiseptics | Wastewater, veterinary use, improper disposal | Antimicrobial resistance, hormonal effects, allergic reactions | Low degradation in water; accumulation in livestock and crops | |

| Endocrine-Disrupting Chemicals (EDCs) [43,44,46] | Bisphenol A (BPA), Phthalates, DDT, PBDEs, Alkylphenols | Plastics, pesticides, cosmetics, detergents | Reproductive disorders, thyroid dysfunction, metabolic and neurodevelopmental effects | Lipophilic and persistent; low-dose potency | |

| PFAS [48,50] | PFOA, PFOS, Short-chain PFAS | Food packaging, cookware, water, firefighting foam | Immunotoxicity, cancer, endocrine disruption, developmental toxicity | “Forever chemicals”; bioaccumulate and resist degradation | |

| Other Emerging Contaminants | Engineered nanomaterials, Cyanotoxins, Masked mycotoxins | Additives, algal blooms, food processing | Cellular damage, hepatotoxicity, neurotoxicity | Incomplete toxicokinetic profiles; unknown persistence |

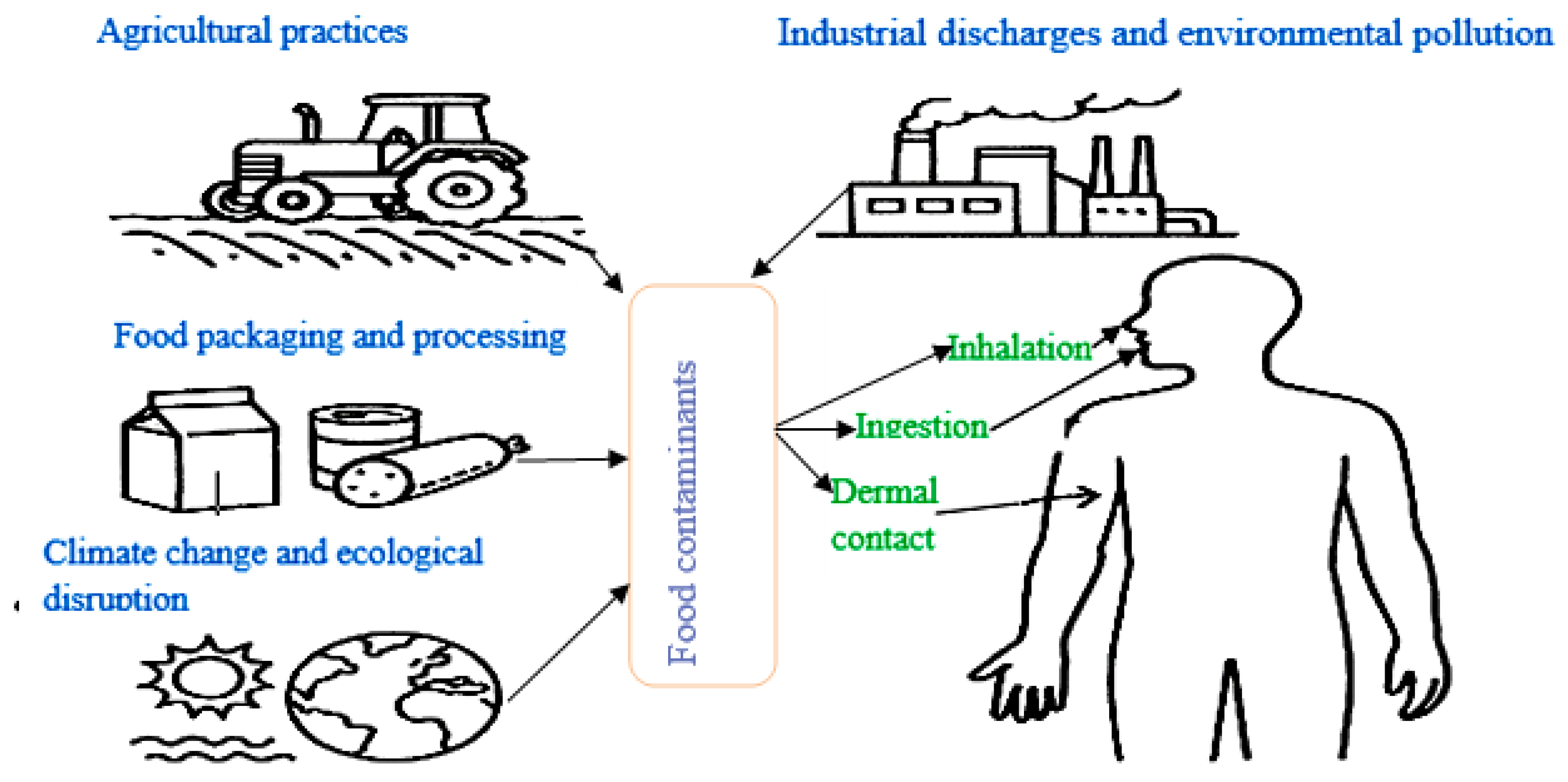

6. Sources and Pathways of Exposure

6.1. Agricultural Practices

6.2. Industrial Discharges and Environmental Pollution

6.3. Food Packaging and Processing

6.4. Climate Change and Ecological Disruption

7. Human Exposure Routes

7.1. Vulnerable Populations and Differential Exposure and Cumulative Exposure and Biomagnification

7.2. Integrated Exposure Perspective

| Category | Source / Subcategory | Contaminant Types | Pathways | Health Implications |

| Agricultural Practices [70,71,72,73] | Pesticides and herbicides | Organochlorines, Organophosphates, Neonicotinoids | Crop residues, soil uptake | Neurotoxicity, endocrine disruption, carcinogenicity |

| Fertilizers and soil amendments | Cadmium, Lead, Arsenic | Soil → plant uptake → food | Renal damage, developmental toxicity | |

| Livestock inputs | Antibiotics, Hormones | Meat, milk, eggs | Antimicrobial resistance, hormonal imbalance | |

| Contaminated irrigation | Industrial effluents, sewage | Crops and vegetables | Multi-pathway toxicity | |

| Improper storage | Mycotoxins (Aflatoxins, Ochratoxin A) | Grains, nuts, cereals | Hepatotoxicity, immunosuppression, carcinogenesis | |

| Industrial Pollution [74,75,76,77,78,79] | Mining, smelting, waste incineration | Lead, Mercury, Cadmium, Arsenic | Soil, water, air → crops, aquatic organisms | Neurological, carcinogenic effects |

| POPs and industrial byproducts | PCBs, Dioxins, PAHs | Soil → food crops, fish | Endocrine disruption, immunotoxicity | |

| PPCPs from urban waste | Antibiotics, Hormones, Triclosan | Aquatic food, crops via irrigation | Antibiotic resistance, endocrine disruption | |

| Plastic pollution | Microplastics, Nano plastics | Water, seafood, airborne particles | Inflammation, oxidative stress | |

| Food Processing & Packaging [80,81,82] | Food contact materials | Phthalates, BPA, PFAS | Migration into food during storage or heating | Endocrine disruption, immune effects |

| Processing byproducts | Acrylamide, PAHs, Heavy metals | Frying, grilling, metal equipment | Carcinogenicity, neurotoxicity | |

| Additives and preservatives | Nitrates, Sulfites, Benzoates | Chemical interactions in processed food | Allergies, potential genotoxicity | |

| Cross-contamination | Allergens, chemical residues | Multi-product processing lines | Anaphylaxis, chronic illness | |

| Climate & Ecology [83,84,85,86,87] | Fungal proliferation | Mycotoxins | Contaminated crops | Liver cancer, stunted growth |

| Increased pesticide use | Modern agrochemicals | Crop residues | Bioaccumulation, ecological toxicity | |

| Contaminated irrigation | Floods, droughts, poor water quality | Crops and food animals | Gastrointestinal and systemic effects | |

| Biodiversity loss | Altered pollutant degradation | Food webs, aquatic systems | Elevated biomagnification | |

| Human Exposure Routes [88,89,90,91,92,93,94] | Ingestion | Food, water | Heavy metals, pesticides, EDCs, mycotoxins | Systemic toxicity, chronic illness |

| Inhalation | Dust, aerosols, indoor air | Microplastics, pesticides, heavy metals | Respiratory damage, mucosal uptake | |

| Dermal contact | Skin handling, contaminated surfaces | Organophosphates, phthalates | Local or systemic absorption | |

| Vulnerable Populations [95,96,97] | Infants and children | BPA, Lead, Mycotoxins | Diet, environment | Neurological damage, immune dysfunction |

| Pregnant women | Mercury, Phthalates | Fish, packaging | Fetal toxicity, endocrine effects | |

| Occupational groups | Farmers, food workers | Multiple (via air, skin) | Cumulative toxicity | |

| Low-income populations | Poor-quality foods | Multiple | Increased exposure, limited care access | |

| Additional Considerations [102,103] | Globalized trade | Imported products | Variable regulation | Transboundary contamination |

| Household behaviors | Cooking methods, storage | Acrylamide, PAHs, degradation products | Formation or reduction of contaminants | |

| Dietary choices | Fish, organic, processed foods | Metals, POPs, additives | Differential exposure |

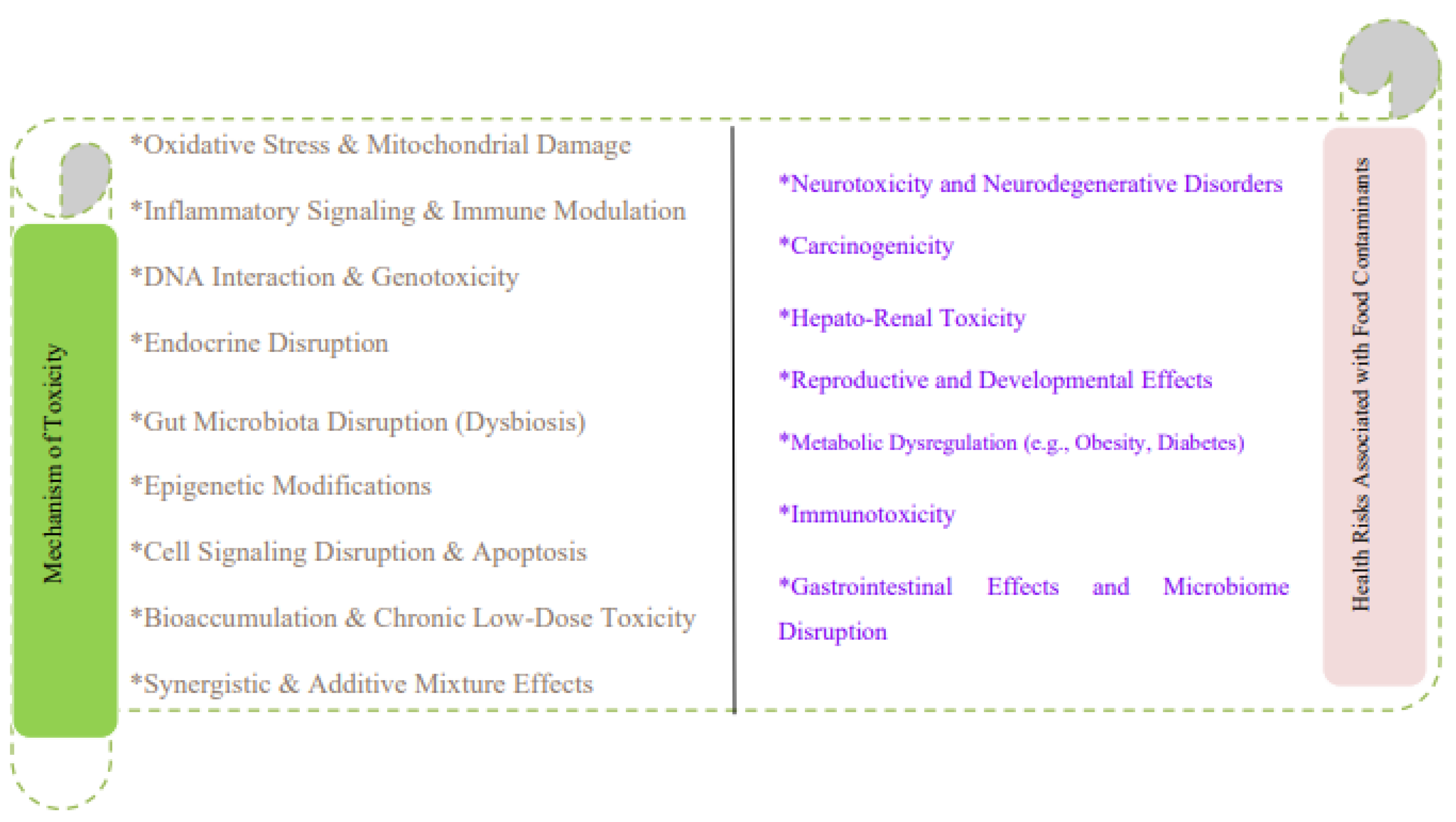

8. Mechanisms of Toxicity

8.1. Oxidative Stress and Mitochondrial Damage

8.2. Inflammatory Signaling and Immune Modulation

8.3. DNA Interaction and Genotoxicity

8.4. Hormonal Interference and Endocrine Disruption

8.5. Disruption of Gut Microbiota (Gut Dysbiosis)

8.6. Epigenetic Modifications

8.7. Disruption of Cell Signaling and Apoptosis

8.8. Bioaccumulation and Chronic Low-Dose Toxicity

8.9. Synergistic and Additive Effects of Contaminant Mixtures

| Toxicological Mechanism | Key Food Contaminants | Biological Effects | Health Implications | Supporting Evidence |

| Oxidative Stress & Mitochondrial Damage [105,106,107,108] | Heavy metals (Cd, Hg, Pb, As), pesticides, mycotoxins, microplastics | ROS overproduction, mitochondrial dysfunction, ATP depletion, cytochrome c release | Neurodegeneration, carcinogenesis, cardiovascular diseases | Mitochondrial ETC inhibition, lipid peroxidation, apoptosis induction |

| Inflammatory Signaling & Immune Modulation [109,110,111,112] | BPA, phthalates, dioxins, microplastics | NF-κB and MAPK activation, cytokine upregulation, inflammasome activation | Chronic inflammation, autoimmune disease, infection susceptibility | IL-6, TNF-α, IL-1β elevation; NLRP3 inflammasome activation in intestines |

| DNA Interaction & Genotoxicity [113,114,115] | Aflatoxin B1, arsenic, chromium, PFAS, pharmaceutical residues | DNA adducts, strand breaks, oxidative lesions, impaired DNA repair | Mutagenesis, carcinogenesis | TP53 mutations; inhibition of BER/NER pathways; promoter methylation changes |

| Endocrine Disruption [116,117,118,119] | BPA, phthalates, PFAS, dioxins | Hormone mimicry/antagonism, disrupted synthesis and signaling | Reproductive disorders, hormonal cancers, developmental delays | Xenoestrogen activity; steroidogenesis inhibition; altered thyroid function |

| Gut Microbiota Disruption (Dysbiosis) [120,121,122,123] | Antibiotics, heavy metals, microplastics, additives | Microbial imbalance, barrier dysfunction, endotoxin leakage | Metabolic syndrome, inflammation, neurobehavioral disorders | Leaky gut; LPS-induced systemic inflammation; altered xenobiotic metabolism |

| Epigenetic Modifications [124,125,126,127] | BPA, phthalates, arsenic, cadmium, lead, mycotoxins | DNA methylation changes, histone modification, miRNA dysregulation | Cancer, neurodevelopmental and metabolic disorders, transgenerational effects | p16/p53 hypermethylation; miR-21 overexpression; heritable epigenetic reprogramming |

| Cell Signaling Disruption & Apoptosis [132,133,134,135] | PCBs, dioxins, pesticides, mycotoxins, microplastics | AhR activation, MAPK/JNK signaling, altered Bcl-2/Bax ratio | Fibrosis, organ damage, tumorigenesis | Apoptotic gene dysregulation; necroptosis induction in GI tissues |

| Bioaccumulation & Chronic Low-Dose Toxicity [136,137,138,139] | Methylmercury, PCBs, PFAS | Lipid accumulation, prolonged half-life, systemic burden | Delayed toxicity, vulnerable population risks | Non-monotonic dose-response; toxic threshold accumulation |

| Synergistic & Additive Mixture Effects [140,141,142,143,144] | Heavy metals + pesticides, mycotoxins + PAHs, microplastics + POPs | Amplified toxicity, detoxification impairment, "Trojan horse" effects | Multi-organ damage, cumulative risk, low-dose potentiation | Co-exposure amplifies oxidative stress, inflammation, neurotoxicity |

9. Health Risks Associated with Food Contaminants

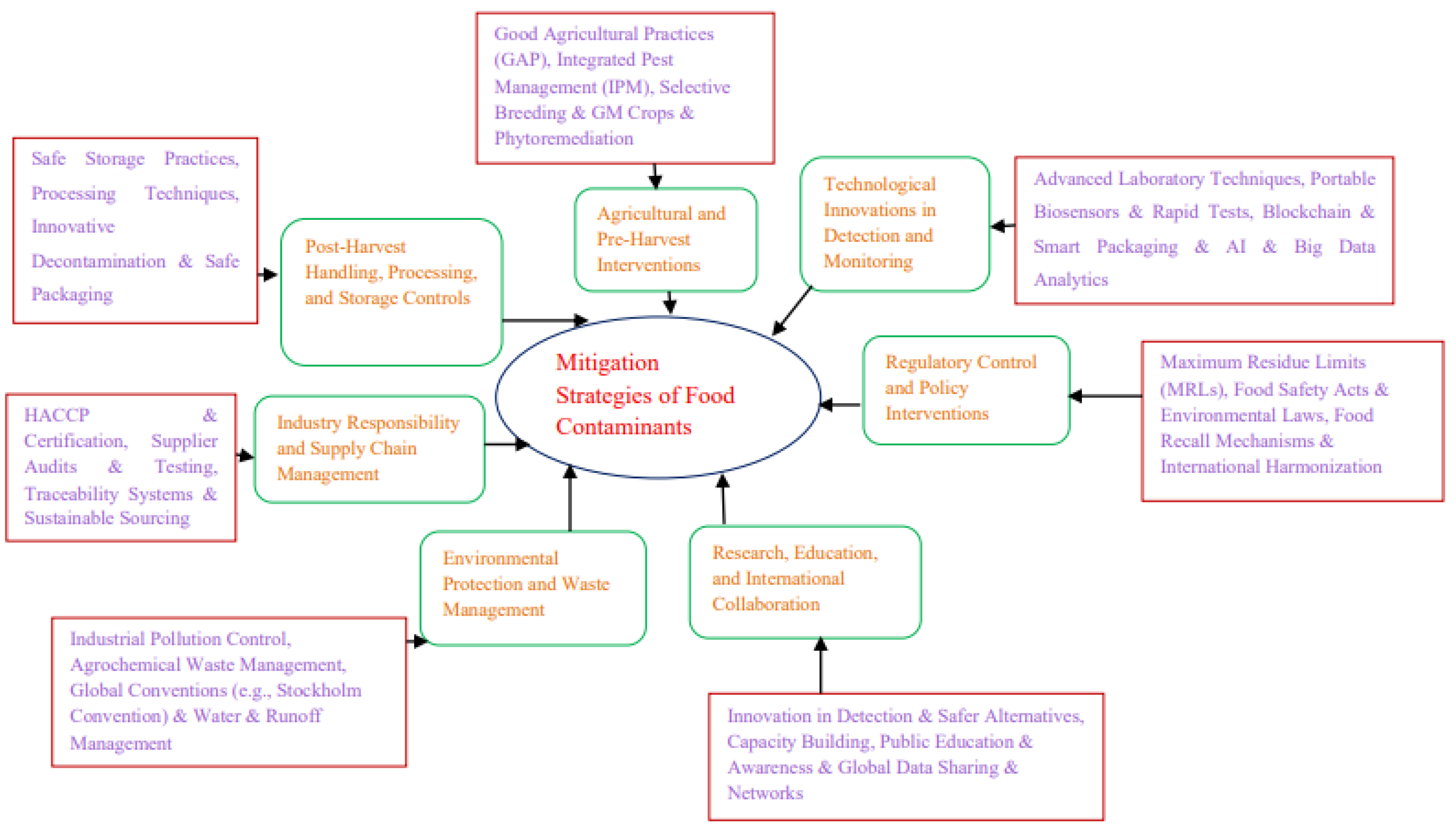

10. Mitigation Strategies for Emerging and Persistent Food Contaminants

10.1. Regulatory Control and Policy Interventions

10.2. Technological Innovations in Detection and Monitoring

10.3. Agricultural and Pre-Harvest Interventions

10.4. Post-Harvest Handling, Processing, and Storage Controls

10.5. Industry Responsibility and Supply Chain Management

10.6. Environmental Protection and Waste Management

10.7. Research, Education, and International Collaboration

11. Strengths, Limitations, and Future Directions

12. Conclusion

Acknowledgments

Conflict of Interest

CRediT Authorship Contribution Statement: Gudisa B

References

- Nayak, R.; Waterson, P. Global food safety as a complex adaptive system: Key concepts and future prospects. Trends Food Sci Technol. 2019, 91, 409–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, B.; Alabbosh, K.F.; Jalal, A.; et al. Sustainable food systems transformation in the face of climate change: strategies, challenges, and policy implications. Food Sci Biotechnol. 2024, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, R.; Abate, M.C.; Cai, B.; et al. A systematic review of contemporary challenges and debates on Chinese food security: integrating priorities, trade-offs, and policy pathways. Foods. 2025, 14, 1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pingali, P.; Aiyar, A.; Abraham, M.; et al. Transforming food systems for a rising India. Springer Nature; 2019.

- Garvey, M. Food pollution: a comprehensive review of chemical and biological sources of food contamination and impact on human health. Nutrire. 2019, 44, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Li, C.; Yu, H.; et al. Chemical food contaminants during food processing: sources and control. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2021, 61, 1545–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iwu, C.D.; Okoh, A.I. Preharvest transmission routes of fresh produce-associated bacterial pathogens with outbreak potentials: a review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019, 16, 4407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Huang, H.; Song, G.; et al. Intelligent biosensing strategies for rapid detection in food safety: a review. Biosens Bioelectron. 2022, 202, 114003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baethge, C.; Goldbeck-Wood, S.; Mertens, S. SANRA—a scale for the quality assessment of narrative review articles. Res Integr Peer Rev. 2019, 4, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munir, N.; Jahangeer, M.; Bouyahya, A.; et al. Heavy metal contamination of natural foods is a serious health issue: a review. Sustainability. 2021, 14, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mititelu, M.; Neacșu, S.M.; Busnatu, Ș.S.; et al. Assessing heavy metal contamination in food: implications for human health and environmental safety. Toxics. 2025, 13, 333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hembrom, S.; Singh, B.; Gupta, S.K.; et al. A comprehensive evaluation of heavy metal contamination in foodstuff and associated human health risk: a global perspective. Contemp Environ Issues Chall Clim Change Era. In Contemp Environ Issues Chall Clim Change Era; 2020; pp. 33–63. [Google Scholar]

- Angon, P.B.; Islam, M.S.; Das, A.; et al. Sources, effects and present perspectives of heavy metals contamination: soil, plants and human food chain. Heliyon. 2024, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarker, A.; Kim, J.E.; Islam, A.R.; et al. Heavy metals contamination and associated health risks in food webs—a review focuses on food safety and environmental sustainability in Bangladesh. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2022, 29, 3230–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carvalho, F.P. Pesticides, environment, and food safety. Food Energy Secur. 2017, 6, 48–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.; Ullah, M.I.; Sajjad, A.; et al. Environmental and health effects of pesticide residues. Sustain Agric Rev. 2021, 48, 311–36. [Google Scholar]

- Grewal, A.S. Pesticide residues in food grains, vegetables, and fruits: a hazard to human health. J Med Chem Toxicol. 2017, 2, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paoli, M.; Giurfa, M. Pesticides and pollinator brain: how do neonicotinoids affect the central nervous system of bees? Eur J Neurosci. 2024, 60, 5927–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buszewski, B.; Bukowska, M.; Ligor, M.; et al. A holistic study of neonicotinoids neuroactive insecticides—properties, applications, occurrence, and analysis. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2019, 26, 34723–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graham, K.Z. Federal regulation of pesticide residues: a brief history and analysis. J Food Law Policy. 2019, 15, 98. [Google Scholar]

- Neme, K.; Mohammed, A. Mycotoxin occurrence in grains and the role of postharvest management as a mitigation strategies: a review. Food Control. 2017, 78, 412–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeyeye, S.A. Fungal mycotoxins in foods: a review. Cogent Food Agric. 2016, 2, 1213127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assefa, T.; Geremew, T. Major mycotoxins occurrence, prevention and control approaches. Biotechnol Mol Biol Rev. 2018, 12, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Awuchi, C.G.; Ondari, E.N.; Ogbonna, C.U.; et al. Mycotoxins affecting animals, foods, humans, and plants: types, occurrence, toxicities, action mechanisms, prevention, and detoxification strategies—a revisit. Foods. 2021, 10, 1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Awuchi, C.G.; Ondari, E.N.; Eseoghene, I.J.; et al. Fungal growth and mycotoxins production: types, toxicities, control strategies, and detoxification. In: Fungal Reprod Growth. IntechOpen; 2021.

- Ododo, M.M.; Wabalo, B.K. Polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) and their impacts on human health: a review. J Environ Pollut Hum Health. 2019, 7, 73–7. [Google Scholar]

- Reddy, A.V.; Moniruzzaman, M.; Aminabhavi, T.M. Polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) in the environment: recent updates on sampling, pretreatment, cleanup technologies and their analysis. Chem Eng J. 2019, 358, 1186–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeno, J.G.; Rathna, R.; Nakkeeran, E. Biological implications of dioxins/furans bioaccumulation in ecosystems. In: Environ Pollut Remediat. Springer; 2021:395-420.

- Yashwanth, A.; Huang, R.; Iepure, M.; et al. Food packaging solutions in the post-PFAS and microplastics era: a review of functions, materials, and bio-based alternatives. Compr Rev Food Sci Food Saf. 2025, 24, e70079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eze, C.G.; Okeke, E.S.; Nwankwo, C.E.; et al. Emerging contaminants in food matrices: an overview of the occurrence, pathways, impacts and detection techniques of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances. Toxicol Rep. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oz, E. Mutagenic and/or carcinogenic compounds in meat and meat products: polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons perspective. Theor Pract Meat Process. 2022, 7, 282–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeyeye, S.A.; Ashaolu, T.J. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons formation and mitigation in meat and meat products. Polycycl Aromat Compd. 2022, 42, 3401–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panel on Contaminants in the Food Chain (CONTAM). Presence of microplastics and nanoplastics in food, with particular focus on seafood. EFSA J. 2016, 14, e04501.

- Toussaint, B.; Raffael, B.; Angers-Loustau, A.; et al. Review of micro- and nanoplastic contamination in the food chain. Food Addit Contam Part A. 2019, 36, 639–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Q.; Chen, Z.; Chen, Y.; et al. Microplastics and nanoplastics: emerging contaminants in food. J Agric Food Chem. 2021, 69, 10450–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amobonye, A.; Bhagwat, P.; Raveendran, S.; et al. Environmental impacts of microplastics and nanoplastics: a current overview. Front Microbiol. 2021, 12, 768297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelis, J.L.; Schacht, V.J.; Dawson, A.L.; et al. The measurement of food safety and security risks associated with micro- and nanoplastic pollution. TrAC Trends Anal Chem. 2023, 161, 116993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alimi, O.S.; Farner Budarz, J.; Hernandez, L.M.; et al. Microplastics and nanoplastics in aquatic environments: aggregation, deposition, and enhanced contaminant transport. Environ Sci Technol. 2018, 52, 1704–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaturvedi, P.; Shukla, P.; Giri, B.S.; et al. Prevalence and hazardous impact of pharmaceutical and personal care products and antibiotics in environment: a review on emerging contaminants. Environ Res. 2021, 194, 110664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, M.; Sridharan, S.; Sawarkar, A.D.; et al. Current research trends on emerging contaminants pharmaceutical and personal care products (PPCPs): a comprehensive review. Sci Total Environ. 2023, 859, 160031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rehman, M.U.; Nisar, B.; Yatoo, A.M.; et al. After effects of Pharmaceuticals and Personal Care Products (PPCPs) on the biosphere and their counteractive ways. Sep Purif Technol. 2024, 126921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guarnotta, V.; Amodei, R.; Frasca, F.; et al. Impact of chemical endocrine disruptors and hormone modulators on the endocrine system. Int J Mol Sci. 2022, 23, 5710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Yang, J.; Yao, B.; et al. Endocrine disrupting chemicals in the environment: Environmental sources, biological effects, remediation techniques, and perspective. Environ Pollut. 2022, 310, 119918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, J.; Liu, P.; Yu, X.; et al. The adverse role of endocrine disrupting chemicals in the reproductive system. Front Endocrinol. 2024, 14, 1324993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lauretta, R.; Sansone, A.; Sansone, M.; et al. Endocrine disrupting chemicals: effects on endocrine glands. Front Endocrinol. 2019, 10, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Priyadarshini, E.; Parambil, A.M.; Rajamani, P.; et al. Exposure, toxicological mechanism of endocrine disrupting compounds and future direction of identification using nano-architectonics. Environ Res. 2023, 225, 115577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glüge, J.; Scheringer, M.; Cousins, I.T.; et al. An overview of the uses of per-and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS). Environ Sci Process Impacts. 2020, 22, 2345–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glenn, G.; Shogren, R.; Jin, X.; et al. Per-and polyfluoroalkyl substances and their alternatives in paper food packaging. Compr Rev Food Sci Food Saf. 2021, 20, 2596–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaines, L.G. Historical and current usage of per-and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS): A literature review. Am J Ind Med. 2023, 66, 353–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dias, D.; Bons, J.; Kumar, A.; et al. Forever chemicals, per-and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), in lubrication. Lubricants. 2024, 12, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogunsona, E.O.; Muthuraj, R.; Ojogbo, E.; et al. Engineered nanomaterials for antimicrobial applications: A review. Appl Mater Today. 2020, 18, 100473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suvarna, V.; Nair, A.; Mallya, R.; et al. Antimicrobial nanomaterials for food packaging. Antibiotics. 2022, 11, 729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Rhim, J.W. Titanium dioxide (TiO2) for the manufacture of multifunctional active food packaging films. Food Packag Shelf Life. 2022, 31, 100806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younis, A.B.; Haddad, Y.; Kosaristanova, L.; et al. Titanium dioxide nanoparticles: Recent progress in antimicrobial applications. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Nanomed Nanobiotechnol. 2023, 15, e1860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, L.A.; Darwish, W.S. Environmental chemical contaminants in food: review of a global problem. J Toxicol. 2019, 2019, 2345283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, H.; Khan, E.; Ilahi, I. Environmental chemistry and ecotoxicology of hazardous heavy metals: environmental persistence, toxicity, and bioaccumulation. J Chem. 2019, 2019, 6730305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chmiel, T.; Mieszkowska, A.; Kempińska-Kupczyk, D.; et al. The impact of lipophilicity on environmental processes, drug delivery and bioavailability of food components. Microchem J. 2019, 146, 393–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lead, J.R.; Batley, G.E.; Alvarez, P.J.; et al. Nanomaterials in the environment: behavior, fate, bioavailability, and effects—an updated review. Environ Toxicol Chem. 2018, 37, 2029–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Améduri, B. Fluoropolymers as unique and irreplaceable materials: challenges and future trends in these specific per or poly-fluoroalkyl substances. Molecules. 2023, 28, 7564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Talabazar, F.R.; Baresel, C.; Ghorbani, R.; et al. Removal of per-and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) from wastewater using the hydrodynamic cavitation on a chip concept. Chem Eng J. 2024, 495, 153573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, I.; Kalve, E.; McDonough, J.; et al. Per-and polyfluoroalkyl substances. Emerg Contam Handb. 2019:85-257.

- Rietjens, I.M.; Tyrakowska, B.; van den Berg, S.J.; et al. Matrix-derived combination effects influencing absorption, distribution, metabolism and excretion (ADME) of food-borne toxic compounds: implications for risk assessment. Toxicol Res. 2015, 4, 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A. Toxicokinetics, pharmacokinetics, and absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion. In: Inf Resour Toxicol. Academic Press; 2020:483-488.

- Rajpoot, K.; Tekade, M.; Sharma, M.C.; et al. Principles and concepts in toxicokinetic. Pharm Tox Consider. 2022, 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Nichols, J.W.; Arnot, J.A.; Barron, M.G. Toxicokinetics in fishes. In: Toxicol Fishes. CRC Press; 2024:3-59.

- Wang, W.X. Bioaccumulation and biomonitoring. In: Mar Ecotoxicol. Academic Press; 2016:99-119.

- Nnaji, N.D.; Onyeaka, H.; Miri, T.; et al. Bioaccumulation for heavy metal removal: a review. SN Appl Sci. 2023, 5, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spacie, A.; McCarty, L.S.; Rand, G.M. Bioaccumulation and bioavailability in multiphase systems. In: Fundam Aquat Toxicol. CRC Press; 2020:493-521.

- Khatri, P.; Kumar, P.; Shakya, K.S.; et al. Understanding the intertwined nature of rising multiple risks in modern agriculture and food system. Environ Dev Sustain. 2024, 26, 24107–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alengebawy, A.; Abdelkhalek, S.T.; Qureshi, S.R.; et al. Heavy metals and pesticides toxicity in agricultural soil and plants: Ecological risks and human health implications. Toxics. 2021, 9, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beyuo, J.; Sackey, L.N.; Yeboah, C.; et al. The implications of pesticide residue in food crops on human health: a critical review. Discov Agric. 2024, 2, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieder, R.; Benbi, D.K.; Reichl, F.X.; et al. Health risks associated with pesticides in soils. In: Soil Comp Hum Health. 2018:503-73.

- Botnaru, A.A.; Lupu, A.; Morariu, P.C.; et al. Balancing health and sustainability: assessing the benefits of plant-based diets and the risk of pesticide residues. Nutrients. 2025, 17, 727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Annar, S. The characteristics, toxicity and effects of heavy metals arsenic, mercury and cadmium: A review. Int J Multidiscip Educ. 2022, 2022, May 10. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman, Z.; Singh, V.P. The relative impact of toxic heavy metals (THMs)(arsenic, cadmium, chromium, mercury, and lead) on the total environment: an overview. Environ Monit Assess. 2019, 191, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mishra, S.; Bharagava, R.N.; More, N.; et al. Heavy metal contamination: an alarming threat to environment and human health. In: Environ Biotechnol Sustain Future. Springer Singapore; 2018:103-125.

- Sonone, S.S.; Jadhav, S.; Sankhla, M.S.; et al. Water contamination by heavy metals and their toxic effect on aquaculture and human health through food chain. Lett Appl NanoBioSci. 2020, 10, 2148–66. [Google Scholar]

- Sankhla, M.S.; Kumari, M.; Nandan, M.; et al. Heavy metals contamination in water and their hazardous effect on human health-a review. Int J Curr Microbiol Appl Sci. 2016, 5, 759–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagaba, A.H.; Lawal, I.M.; Birniwa, A.H.; et al. Sources of water contamination by heavy metals. In: Membr Technol Heavy Metal Remov Water. CRC Press; 2024:3-27.

- Panou, A.; Karabagias, I.K. Migration and safety aspects of plastic food packaging materials: need for reconsideration? Coatings. 2024, 14, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, H.T.; Samsudin, H.; Soto-Valdez, H. Migration of endocrine-disrupting chemicals into food from plastic packaging materials: an overview of chemical risk assessment, techniques to monitor migration, and international regulations. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2022, 62, 957–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Proietti, M. Genotoxic effects of plastic leachates and plastic-related chemicals, Bisphenol A (BPA) and perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA), in Drosophila melanogaster.

- Misiou, O.; Koutsoumanis, K. Climate change and its implications for food safety and spoilage. Trends Food Sci Technol. 2022, 126, 142–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duchenne-Moutien, R.A.; Neetoo, H. Climate change and emerging food safety issues: a review. J Food Prot. 2021, 84, 1884–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhatt, P.; Kumar, V.; Singh, S.; et al. Climatic/Meteorological Conditions and Their Role in Biological Contamination: A Comprehensive Review. Airborne Biocontam Impact Hum Health. 2024:56-88.

- Singh, B.K.; Delgado-Baquerizo, M.; Egidi, E.; et al. Climate change impacts on plant pathogens, food security and paths forward. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2023, 21, 640–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomes, M.P. The convergence of antibiotic contamination, resistance, and climate dynamics in freshwater ecosystems. Water. 2024, 16, 2606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rather, I.A.; Koh, W.Y.; Paek, W.K.; et al. The sources of chemical contaminants in food and their health implications. Front Pharmacol. 2017, 8, 830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohammad, A.M.; Chowdhury, T.; Biswas, B.; et al. Food poisoning and intoxication: A global leading concern for human health. In: Food Saf Preserv. 2018:307-52.

- Lebelo, K.; Malebo, N.; Mochane, M.J.; et al. Chemical contamination pathways and the food safety implications along the various stages of food production: a review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021, 18, 5795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sridharan, S.; Kumar, M.; Singh, L.; et al. Microplastics as an emerging source of particulate air pollution: A critical review. J Hazard Mater. 2021, 418, 126245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boccia, P.; Mondellini, S.; Mauro, S.; et al. Potential effects of environmental and occupational exposure to microplastics: an overview of air contamination. Toxics. 2024, 12, 320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, S.E.; Meade, B.J. Potential health effects associated with dermal exposure to occupational chemicals. Environ Health Insights. 2014, 8, EHI–S15258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nurulain, M.U.; Syed Ismail, S.N.; Emilia, Z.A.; et al. Pesticide application, dermal exposure risk and factors influenced distribution on different body parts among agriculture workers. Malays J Public Health Med. 2017, 1, 123–32. [Google Scholar]

- Tola, G.B. Food Contaminants: A Scoping Review of Sources, Toxicity, Pathophysiological Insights, and Mitigation Strategies. 2025.

- Kościelecka, K.; Kuć, A.; Kubik-Machura, D.; et al. Endocrine effect of some mycotoxins on humans: a clinical review of the ways to mitigate the action of mycotoxins. Toxins. 2023, 15, 515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Renzo, G.C. Nutrients and environmental toxicants: effect on placental function and fetal growth. Obstet Gynecol Reprod. 2024, 18, 112–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonnineau, C.; Artigas, J.; Chaumet, B.; et al. Role of biofilms in contaminant bioaccumulation and trophic transfer in aquatic ecosystems: current state of knowledge and future challenges. Rev Environ Contam Toxicol. 2021, 253, 115–53. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Stanley, J.; Preetha, G. Pesticide toxicity to fishes: exposure, toxicity and risk assessment methodologies. In: Pesticide Tox Non-target Organ. 2016:411-97.

- Stucki, A.O.; Sauer, U.G.; Allen, D.G.; et al. Differences in the anatomy and physiology of the human and rat respiratory tracts and impact on toxicological assessments. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol. 2024, 105648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farraj, A.K.; Hazari, M.S.; Costa, D.L. Pulmonary toxicology. Mammalian Toxicol. 2015, 519–538. [Google Scholar]

- Faour-Klingbeil, D.; Todd, E.C. A review on the rising prevalence of international standards: Threats or opportunities for the agri-food produce sector in developing countries, with a focus on examples from the MENA region. Foods. 2018, 7, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thorsen, M.; Hill, J.; Farber, J.; et al. Megatrends and emerging issues: Impacts on food safety. Compr Rev Food Sci Food Saf. 2025, 24, e70170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dupouy, E.; Popping, B. Emerging contaminants. In: Present Knowl Food Saf. 2023:267-69.

- Afzal, S.; Abdul Manap, A.S.; Attiq, A.; et al. From imbalance to impairment: the central role of reactive oxygen species in oxidative stress-induced disorders and therapeutic exploration. Front Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1269581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lushchak, V.I. Contaminant-induced oxidative stress in fish: a mechanistic approach. Fish Physiol Biochem. 2016, 42, 711–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anetor, G.O.; Nwobi, N.L.; Igharo, G.O.; et al. Environmental pollutants and oxidative stress in terrestrial and aquatic organisms: examination of the total picture and implications for human health. Front Physiol. 2022, 13, 931386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meli, R.; Monnolo, A.; Annunziata, C.; et al. Oxidative stress and BPA toxicity: an antioxidant approach for male and female reproductive dysfunction. Antioxidants. 2020, 9, 405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, F.L.; Kong, L.; Zhao, A.H.; et al. Inflammatory cytokines as key players of apoptosis induced by environmental estrogens in the ovary. Environ Res. 2021, 198, 111225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farkhondeh, T.; Mehrpour, O.; Buhrmann, C.; et al. Organophosphorus compounds and MAPK signaling pathways. Int J Mol Sci. 2020, 21, 4258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harshitha, P.; Bose, K.; Dsouza, H.S. Influence of lead-induced toxicity on the inflammatory cytokines. Toxicol. 2024, 503, 153771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohammadi, H.; Ashari, S. Mechanistic insight into toxicity of phthalates, the involved receptors, and the role of Nrf2, NF-κB, and PI3K/AKT signaling pathways. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2021, 28, 35488–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, W.; Yu, P.; Yang, K.; et al. Aflatoxin B1: Metabolism, toxicology, and its involvement in oxidative stress and cancer development. Toxicol Mech Methods. 2022, 32, 395–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassan, S.M.; Mughal, S.S.; Hassan, S.K.; et al. Cellular interactions, metabolism, assessment and control of aflatoxins: an update. Comput Biol Bioinform. 2020, 8, 62–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monazzah, M.; Lachenmeier, D.W. Genotoxicity of Coffee, Coffee By-Products, and Coffee Bioactive Compounds: Contradictory Evidence from In Vitro Studies. Toxics. 2025, 13, 409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stiefel, C.; Stintzing, F. Endocrine-active and endocrine-disrupting compounds in food–occurrence, formation and relevance. NFS J. 2023, 31, 57–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, V.G.; Henrique, G.; Sousa-Vidal, É.K.; et al. Thyroid under Attack: The Adverse Impact of Plasticizers, Pesticides, and PFASs on Thyroid Function. Endocrines. 2024, 5, 430–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Spade, D.J. Reproductive toxicology: Environmental exposures, fetal testis development and function: phthalates and beyond. Reproduction. 2021, 162, F147–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Nisio, A.; Corsini, C.; Foresta, C. Environmental impact on the hypothalamus-pituitary-testis axis. In: Environ Endocrinol Endocr Disruptors. 2023:207-38.

- Elmassry, M.M.; Zayed, A.; Farag, M.A. Gut homeostasis and microbiota under attack: Impact of the different types of food contaminants on gut health. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2022, 62, 738–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elmassry, M.M.; Zayed, A.; Farag, M.A.; et al. Gut homeostasis and microbiota under attack: Impact of different types of food contaminants on gut health. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2022, 62, 738–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Claus, S.P.; Guillou, H.; Ellero-Simatos, S. The gut microbiota: a major player in the toxicity of environmental pollutants? Npj Biofilms Microbiomes. 2016, 2, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Popli, S.; Badgujar, P.C.; Agarwal, T.; et al. Persistent organic pollutants in foods, their interplay with gut microbiota and resultant toxicity. Sci Total Environ. 2022, 832, 155084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, P.; Ye, Z.; Kakade, A.; et al. A review on gut remediation of selected environmental contaminants: possible roles of probiotics and gut microbiota. Nutrients. 2018, 11, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desaulniers, D.; Vasseur, P.; Jacobs, A.; et al. Integration of epigenetic mechanisms into non-genotoxic carcinogenicity hazard assessment: focus on DNA methylation and histone modifications. Int J Mol Sci. 2021, 22, 10969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buha, A.; Manic, L.; Maric, D.; et al. The effects of endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs) on the epigenome—A short overview. Toxicol Res Appl. 2022, 6, 23978473221115817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, D.D. Epigenetic mechanisms of endocrine-disrupting chemicals in breast cancer and their impact on dietary intake. J Xenobiot. 2024, 15, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langie, S.A.; Koppen, G.; Desaulniers, D.; et al. Causes of genome instability: the effect of low dose chemical exposures in modern society. Carcinogenesis 2015, 36 (Suppl_1), S61–S88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spatari, G.; Allegra, A.; Carrieri, M.; et al. Epigenetic effects of benzene in hematologic neoplasms: the altered gene expression. Cancers. 2021, 13, 2392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Acharjee, S.; Chauhan, S.; Pal, R.; et al. Mechanisms of DNA methylation and histone modifications. Prog Mol Biol Transl Sci. 2023, 197, 51–92. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lewis, C.J.; Mardaryev, A.N.; Sharov, A.A.; et al. The epigenetic regulation of wound healing. Adv Wound Care (New Rochelle). 2014, 3, 468–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis, C.J.; Stevenson, A.; Fear, M.W.; et al. A review of epigenetic regulation in wound healing: implications for the future of wound care. Wound Repair Regen. 2020, 28, 710–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagar, N.; Saxena, H.; Pathak, A.; et al. A review on structural mechanisms of protein-persistent organic pollutant (POP) interactions. Chemosphere. 2023, 332, 138877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoyeck, M.P.; Matteo, G.; MacFarlane, E.M.; et al. Persistent organic pollutants and β-cell toxicity: a comprehensive review. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2022, 322, E383–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guillotin, S.; Delcourt, N. Studying the impact of persistent organic pollutants exposure on human health by proteomic analysis: a systematic review. Int J Mol Sci. 2022, 23, 14271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beigh, S. A phytochemicals approach towards the role of dioxins in disease progression targeting various pathways: insights. Ind J Pharm Educ Res. 2024, 58, s732–s756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, H.; Ji, Y.; Pan, Y.; et al. Persistent organic pollutants and metabolic diseases: from the perspective of lipid droplets. Environ Pollut. 2024, 124980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Babaniyi, B.R.; Isaac, G.O.; Adebomi, J.I.; et al. Effect of biodegradation and biotransformation of perfluorinated compounds (PFCs), polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs), and perfluoroalkyl substances in human body and food products. In: Emerging Contaminants in Food and Food Products. CRC Press; 2024:162-185.

- Velasco, A.M.; Lesmes, I.B.; Perales, A.D.; et al. Report of the scientific committee of the Spanish Agency for Food Safety and Nutrition (AESAN) on the available evidence in relation to the potential obesogenic activity of certain chemical compounds that may be present in foods. 2023 Sep.

- Wang, X.; Sun, Z.; Liu, Q.S.; et al. Environmental obesogens and their perturbations in lipid metabolism. Environ Health. 2024, 2, 253–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uchendu, C.; Ambali, S.F.; Ayo, J.O.; et al. Chronic co-exposure to chlorpyrifos and deltamethrin pesticides induces alterations in serum lipids and oxidative stress in Wistar rats: mitigating role of alpha-lipoic acid. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2018, 25, 19605–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reddam, A.; McLarnan, S.; Kupsco, A. Environmental chemical exposures and mitochondrial dysfunction: a review of recent literature. Curr Environ Health Rep. 2022, 9, 631–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lou, Y.; Xu, X.; Lv, L.; et al. Co-exposure to cadmium and triazophos induces variations at enzymatic and transcriptional levels in Opsariichthys bidens. Chemosphere. 2024, 362, 142561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beyrami, S.; Ramezanifar, S.; Golmohammadi, H.; et al. Changes in oxidative stress parameters in terms of simultaneous exposure to physical and chemical factors: a systematic review. Iran J Public Health. 2023, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pei DS, Liu Y, editors. Toxicological Assessment of Combined Chemicals in the Environment. John Wiley & Sons; 2025.

- Kaur, M.; Sharma, A.; Bhatnagar, P. Vertebrate response to microplastics, nanoplastics and co-exposed contaminants: assessing accumulation, toxicity, behaviour, physiology, and molecular changes. Toxicol Lett. 2024. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asuku, A.O.; Ayinla, M.T.; Ajibare, A.J.; et al. Heavy metals and emerging contaminants in foods and food products associated with neurotoxicity. In: Emerging Contaminants in Food and Food Products. 2024:236-50.

- Ashif, I.; Musheer, A.; Shahnawaz, A.; et al. Environmental neurotoxic pollutants. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2020, 27, 41175–98. [Google Scholar]

- Thakur, M.; Rachamalla, M.; Niyogi, S.; et al. Molecular mechanism of arsenic-induced neurotoxicity including neuronal dysfunctions. Int J Mol Sci. 2021, 22, 10077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kabbashi, E.B.M. Major contaminants of peanut and its products and their methods of management. 2024.

- Panel EFSA CONTAM; Schrenk, D.; Bignami, M. Panel EFSA CONTAM; Schrenk, D.; Bignami, M.; et al. Risk assessment of aflatoxins in food. 2020.

- Cascella, M.; Bimonte, S.; Barbieri, A.; et al. Dissecting the mechanisms and molecules underlying the potential carcinogenicity of red and processed meat in colorectal cancer (CRC): an overview on the current state of knowledge. Infect Agents Cancer. 2018, 13, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cantwell, M.; Elliott, C. Nitrates, nitrites and nitrosamines from processed meat intake and colorectal cancer risk. J Clin Nutr Diet. 2017, 3, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandal, P.; Lanaridi, O.; Warth, B.; et al. Metabolomics as an emerging approach for deciphering the biological impact and toxicity of food contaminants: the case of mycotoxins. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2024, 64, 9859–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Czarnywojtek, A.; Jaz, K.; Ochmańska, A.; et al. The effect of endocrine disruptors on the reproductive system-current knowledge. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2021, 25. [Google Scholar]

- Amir, S.; Shah, S.T.; Mamoulakis, C.; et al. Endocrine disruptors acting on estrogen and androgen pathways cause reproductive disorders through multiple mechanisms: a review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021, 18, 1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, J.; Liu, P.; Yu, X.; et al. The adverse role of endocrine disrupting chemicals in the reproductive system. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2024, 14, 1324993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patisaul, H.B. Reproductive toxicology: endocrine disruption and reproductive disorders: impacts on sexually dimorphic neuroendocrine pathways. Reproduction. 2021, 162, F111–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernal, K.; Touma, C.; Erradhouani, C.; et al. Combinatorial pathway disruption is a powerful approach to delineate metabolic impacts of endocrine disruptors. FEBS Lett. 2022, 596, 3107–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Celik, M.N.; Yesildemir, O. Endocrine disruptors in child obesity and related disorders: early critical windows of exposure. Curr Nutr Rep. 2025, 14, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nappi, F.; Barrea, L.; Di Somma, C.; et al. Endocrine aspects of environmental “obesogen” pollutants. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2016, 13, 765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nwanaforo, E.; Obasi, C.N.; Frazzoli, C.; et al. Exposure to environmental pollutants and risk of diarrhea: a systematic review. Environ Health Insights. 2024, 18, 11786302241304539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guerrieri, N.; Mazzini, S.; Borgonovo, G. Food plants and environmental contamination: an update. Toxics. 2024, 12, 365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbasi, A.; Sheykhsaran, E.; Hosseinzadeh, N.; et al. Novel approaches in establishing chemical food safety based on the detoxification capacity of probiotics and postbiotics: a critical review. Probiotics Antimicrob Proteins. 2025 Jun 13:1-41.

- Cassani, L.; Gomez-Zavaglia, A.; Simal-Gandara, J. Technological strategies ensuring the safe arrival of beneficial microorganisms to the gut: from food processing and storage to their passage through the gastrointestinal tract. Food Res Int. 2020, 129, 108852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jamroz, E.; Kulawik, P.; Gokbulut, C.; et al. The impact of nano/micro-plastics toxicity on seafood quality and human health: facts and gaps. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2023, 63, 6445–63. [Google Scholar]

- van der Meulen, B.; Wernaart, B. Food and agriculture organization (FAO) and Codex Alimentarius commission. In: Res Handb Eur Union Int Organ. 2019 Sep 27:82-100.

- Fortin, N.D. Global governance of food safety: the role of the FAO, WHO, and Codex Alimentarius in regulatory harmonization. In: Res Handb Int Food Law. 2023 Nov 9:227-42.

- World Health Organization. Understanding the codex alimentarius. Food Agric Organ. 2018 Jun 13.

- Ranjan, S.; Chaitali, R.O.; Sinha, S.K. Gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC-MS): a comprehensive review of synergistic combinations and their applications in the past two decades. J Anal Sci Appl Biotechnol. 2023, 5, 72–85. [Google Scholar]

- Meher, A.K.; Zarouri, A. Environmental applications of mass spectrometry for emerging contaminants. Molecules. 2025, 30, 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shyamalagowri, S.; Shanthi, N.; Manjunathan, J.; et al. Techniques for the detection and quantification of emerging contaminants. Phys Sci Rev. 2023, 8, 2191–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhavadharini, B.; Kavimughil, M.; Malini, B.; et al. Recent advances in biosensors for detection of chemical contaminants in food—a review. Food Anal Methods. 2022, 15, 1545–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nirmala, G. Impact of good agricultural practices (GAP) on small farm development: knowledge and adoption levels of farm women of rainfed areas. Indian Res J Ext Educ. 2015, 15, 153–6. [Google Scholar]

- Kılıç, O.; Boz, I.; Eryılmaz, G.A. Comparison of conventional and good agricultural practices farms: A socio-economic and technical perspective. J Clean Prod. 2020, 258, 120666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olaniran, A.F.; Taiwo, A.E.; Iranloye, Y.M.; et al. The role of good agricultural practices (GAPs) and good manufacturing practices (GMPs) in food safety. Food Saf Toxicol. 2023, 417–432. [Google Scholar]

- Sarrocco, S.; Vannacci, G. Preharvest application of beneficial fungi as a strategy to prevent postharvest mycotoxin contamination: a review. Crop Prot. 2018, 110, 160–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dufera, L.T.; Jimma, E. Management of mycotoxin in post-harvest food chain of durable crops. Manag. 2020, 100, 12–20. [Google Scholar]

- Bartholomew, H.P.; Bradshaw, M.; Jurick, W.M.; et al. The good, the bad, and the ugly: mycotoxin production during postharvest decay and their influence on tritrophic host–pathogen–microbe interactions. Front Microbiol. 2021, 12, 611881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bešić, C.; Bogetić, S.; Ćoćkalo, D.; et al. The role of global GAP in improving competitiveness of agro-food industry. Ekonomika Poljoprivrede. 2015, 62, 583–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, A.; Mueses, C.; Kennedy, H.; et al. Supplier quality assurance systems: important market considerations. In: Food Saf Qual Syst Dev Ctries. 2020 Jan 1:125-84.

- Kimanya, M.E. Contextual interlinkages and authority levels for strengthening coordination of national food safety control systems in Africa. Heliyon, 2024; 10. [Google Scholar]

- Weldeslassie, T.; Naz, H.; Singh, B.; et al. Chemical contaminants for soil, air and aquatic ecosystem. Mod Age Environ Prob Remediat. 2018:1-22.

- Dehkordi, M.M.; Nodeh, Z.P.; Dehkordi, K.S.; et al. Soil, air, and water pollution from mining and industrial activities: sources of pollution, environmental impacts, and prevention and control methods. Results Eng. 2024, 102729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanam, Z.; Sultana, F.M.; Mushtaq, F. Environmental pollution control measures and strategies: an overview of recent developments. Geospat Anal Environ Pollut Model. 2023 Dec 2:385-414.

- Awewomom, J.; Dzeble, F.; Takyi, Y.D.; et al. Addressing global environmental pollution using environmental control techniques: a focus on environmental policy and preventive environmental management. Discov Environ. 2024, 2, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Shen, X.; Jiang, W.; et al. Comprehensive review of emerging contaminants: detection technologies, environmental impact, and management strategies. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2024, 278, 116420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira, L.C.; de Souza, A.O.; Bernardes, M.F.; et al. A perspective on the potential risks of emerging contaminants to human and environmental health. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2015, 22, 13800–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lebelo, K.; Malebo, N.; Mochane, M.J.; et al. Chemical contamination pathways and the food safety implications along the various stages of food production: a review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021, 18, 5795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mu, W.; Kleter, G.A.; Bouzembrak, Y.; et al. Making food systems more resilient to food safety risks by including artificial intelligence, big data, and internet of things into food safety early warning and emerging risk identification tools. Compr Rev Food Sci Food Saf. 2024, 23, e13296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Health Outcome | Key Contaminants | Mechanisms of Toxicity | Vulnerable Populations | Representative Evidence |

| Neurotoxicity and Neurodegeneration [145,146,147,148] | Lead, mercury, arsenic, organophosphates, paraquat, BPA, phthalates, microplastics | Oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, neuroinflammation, neurotransmitter disruption, endocrine interference | Children, pregnant women, agricultural workers | Lead: ↓IQ in children; Methylmercury: fetal neurotoxicity; Pesticides: ↑Parkinson’s risk |

| Carcinogenicity [149,150,151,152] | Aflatoxins, arsenic, dioxins, PCBs, nitrites/nitrates | DNA adducts, epigenetic changes, hormone mimicry, chronic inflammation | Individuals with HBV, processed food consumers | Aflatoxins: liver cancer; Nitrites: colorectal cancer; POPs: breast cancer |

| Hepato-Renal Toxicity [153] | Aflatoxins, ochratoxin A, cadmium, lead, arsenic, PFAS, microplastics | Lipid peroxidation, fibrosis, enzyme dysregulation, histopathological damage | Populations exposed via contaminated crops and water | Cadmium: renal failure; PFAS: ↑ALT and creatinine in rodents |

| Reproductive and Developmental Effects [154,155,156,157] | BPA, phthalates, dioxins, PCBs, cadmium, nitrates | Hormone disruption, epigenetic changes, gametotoxicity, fetal malformations | Pregnant women, fetuses, neonates | Phthalates: ↓sperm quality; BPA: brain sexual dimorphism in animals |

| Metabolic Dysregulation [158,159,160,161] | BPA, phthalates, arsenic, PFAS, organotins | PPAR activation, β-cell dysfunction, mitochondrial stress, lipid accumulation | Children, adolescents, metabolically vulnerable individuals | BPA: ↑obesity in children; Arsenic: insulin resistance; PFAS: ↑cholesterol |

| Immunotoxicity [162,163,164] | Lead, cadmium, aflatoxins, BPA, PFAS, microplastics | Suppressed lymphocyte proliferation, cytokine imbalance, altered antibody response, immune activation | Infants, elderly, immunocompromised individuals | Lead: ↓antibody levels; BPA: immune dysregulation; PFAS: ↓vaccine efficacy |

| Gastrointestinal & Microbiome Disruption [165,166] | Cadmium, mercury, DON, antibiotics, microplastics, BPA, triclosan | Increased permeability, epithelial damage, dysbiosis, SCFA imbalance | Children, individuals with GI disorders | DON: intestinal barrier disruption; Microplastics: dysbiosis in mice; BPA: altered gut flora |

| Main Strategy | Sub-strategy | Description | Relevant Stakeholders |

| Regulatory Control and Policy Interventions [167,168,169] | Maximum Residue Limits (MRLs) | Legally enforced limits for contaminants like heavy metals, pesticides, and mycotoxins to protect consumer health. | Governments, FAO, WHO, Codex Commission |

| Food Safety Acts & Environmental Laws | National laws to regulate food safety, environmental protection, and waste management to prevent contamination. | National Governments, Regulatory Agencies | |

| Food Recall Mechanisms | Systems to rapidly remove contaminated products from the market to prevent public health crises. | Food Industry, Food Safety Authorities | |

| International Harmonization | Global standards (e.g., Codex Alimentarius) to align food safety regulations and facilitate safe trade. | FAO, WHO, Codex Commission | |

| Technological Innovations in Detection and Monitoring [170,171,172,173] | Advanced Laboratory Techniques | Techniques like GC-MS, LC-MS/MS, ICP-MS for highly sensitive contaminant detection. | Laboratories, Food Safety Authorities |

| Portable Biosensors & Rapid Tests | On-site, quick detection of contaminants using immunoassays or molecular methods, crucial in resource-limited areas. | Food Producers, Inspectors | |

| Blockchain & Smart Packaging | Technologies for product traceability and real-time monitoring of contamination risks along the food chain. | Food Industry, Retailers | |

| AI & Big Data Analytics | Predictive tools to analyze contamination risks based on environmental and supply chain data. | Food Industry, Tech Developers | |

| Agricultural and Pre-Harvest Interventions [174,175,176] | Good Agricultural Practices (GAP) | Safe use of water, fertilizers, and pesticides to reduce contaminants at the source. | Farmers, Extension Workers |

| Integrated Pest Management (IPM) | Sustainable pest control combining biological, cultural, and chemical methods to minimize residues. | Farmers, Agribusiness | |

| Selective Breeding & GM Crops | Development of crops with reduced contaminant uptake or fungal resistance (e.g., aflatoxin-resistant varieties). | Researchers, Seed Companies | |

| Phytoremediation | Use of metal-accumulating plants to remediate contaminated soils, reducing heavy metal risks. | Farmers, Environmental Agencies | |

| Post-Harvest Handling, Processing, and Storage Controls [177,178,179] | Safe Storage Practices | Control of moisture, temperature, and aeration to prevent mold growth and mycotoxin production. | Food Handlers, Storage Operators |

| Processing Techniques | Washing, peeling, thermal treatment, fermentation to reduce chemical contaminants. | Food Processors | |

| Innovative Decontamination | UV light, ozone, and irradiation technologies to degrade chemical contaminants and pathogens. | Food Industry | |

| Safe Packaging | Use of food-grade, biodegradable materials to prevent leaching of harmful substances like microplastics. | Packaging Industry, Food Producers | |

| Industry Responsibility and Supply Chain Management [180,181,182] | HACCP & Certification | Implementation of HACCP, ISO 22000, Global G.A.P. to ensure food safety from farm to fork. | Food Industry, Auditors |

| Supplier Audits & Testing | Regular checks to prevent contaminated raw materials entering the production process. | Food Companies, Retailers | |

| Traceability Systems | Use of digital tools, including blockchain, to track food products and enable rapid response to contamination events. | Food Industry, Tech Providers | |

| Sustainable Sourcing | Sourcing practices aimed at minimizing environmental pollution and contamination risks. | Food Companies, Suppliers | |

| Environmental Protection and Waste Management [183,184,185,186] | Industrial Pollution Control | Regulations to limit contaminant release from mining, manufacturing, and other industrial activities. | Environmental Agencies, Industries |

| Agrochemical Waste Management | Safe disposal and treatment of pesticides, fertilizers, and packaging materials to prevent environmental contamination. | Farmers, Waste Management Services | |

| Global Conventions (e.g., Stockholm Convention) | International efforts to restrict or eliminate persistent organic pollutants that can accumulate in the food chain. | Governments, International Bodies | |

| Water & Runoff Management | Wastewater treatment and control of agricultural runoff to protect irrigation water and aquatic food sources. | Farmers, Environmental Agencies | |

| Research, Education, and International Collaboration [187,188,189,190] | Innovation in Detection & Safer Alternatives | Research to improve detection methods and develop biopesticides, natural preservatives, and green technologies. | Research Institutions, Private Sector |

| Capacity Building | Strengthening of laboratory, surveillance, and regulatory capacities, particularly in developing countries. | Governments, Donors, NGOs | |

| Public Education & Awareness | Campaigns targeting farmers, food handlers, industry, and consumers to promote safe practices. | Health Agencies, Media, Educators | |

| Global Data Sharing & Networks | International platforms (WHO, FAO, INFOSAN) to exchange food safety information and coordinate responses. | Governments, International Organizations |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).