1. Introduction

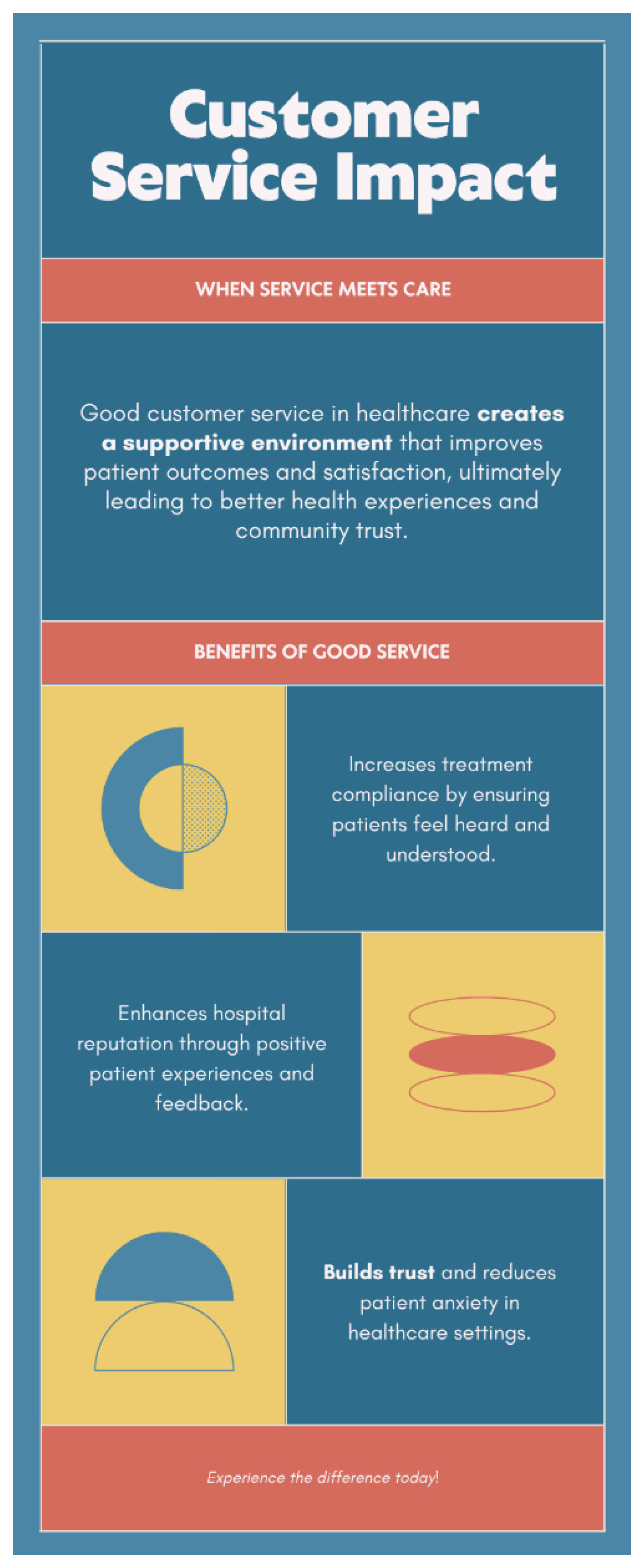

Good customer service in healthcare is more than a professional courtesy; it is a vital element that can significantly affect the quality of care and the patient’s overall experience [

1]. When patients feel respected, heard, and valued, their emotional and psychological well-being improves, which can have a direct influence on physical healing and recovery. Compassionate interactions from receptionists, nurses, doctors, and support staff reduce anxiety, foster trust, and create a sense of safety, especially during vulnerable moments [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6].

The effects of good customer service extend beyond individual feelings. When patients are satisfied with their experience, they are more likely to adhere to treatment plans, attend follow-up appointments, and take an active role in managing their health [

4]. This increased compliance contributes to better health outcomes and lowers the risk of complications. A patient who understands their diagnosis and feels comfortable asking questions is more empowered and engaged, which ultimately leads to more effective care.

Furthermore, healthcare institutions that consistently deliver excellent customer service benefit from improved reputations in the communities they serve [

2]. Satisfied patients often share their positive experiences with friends, family, or online platforms, enhancing the hospital’s public image. This word-of-mouth endorsement can increase patient intake and position the hospital as a trusted provider of care [

1].

Internally, good customer service cultivates a healthier workplace culture. When healthcare workers are trained to engage with empathy and communicate effectively, they experience greater job satisfaction and teamwork improves [

2]. Reduced conflicts, fewer complaints, and a stronger sense of purpose among staff contribute to lower turnover rates and a more motivated workforce.

On a systemic level, quality customer service helps healthcare organizations meet regulatory standards, accreditation criteria, and patient-centered care benchmarks. It also reduces the incidence of complaints, legal disputes, and re-hospitalizations, which can be costly to both patients and the institution [

5].

Ultimately, good customer service in healthcare is not just about politeness or speed; it is about creating a culture where patients are treated with dignity at every point of care. It supports healing, strengthens provider-patient relationships, and builds systems that prioritize both clinical excellence and human compassion. In an increasingly competitive and patient-driven healthcare environment, customer service is not a luxury it is a necessity.

2. The Patient Journey Touchpoints

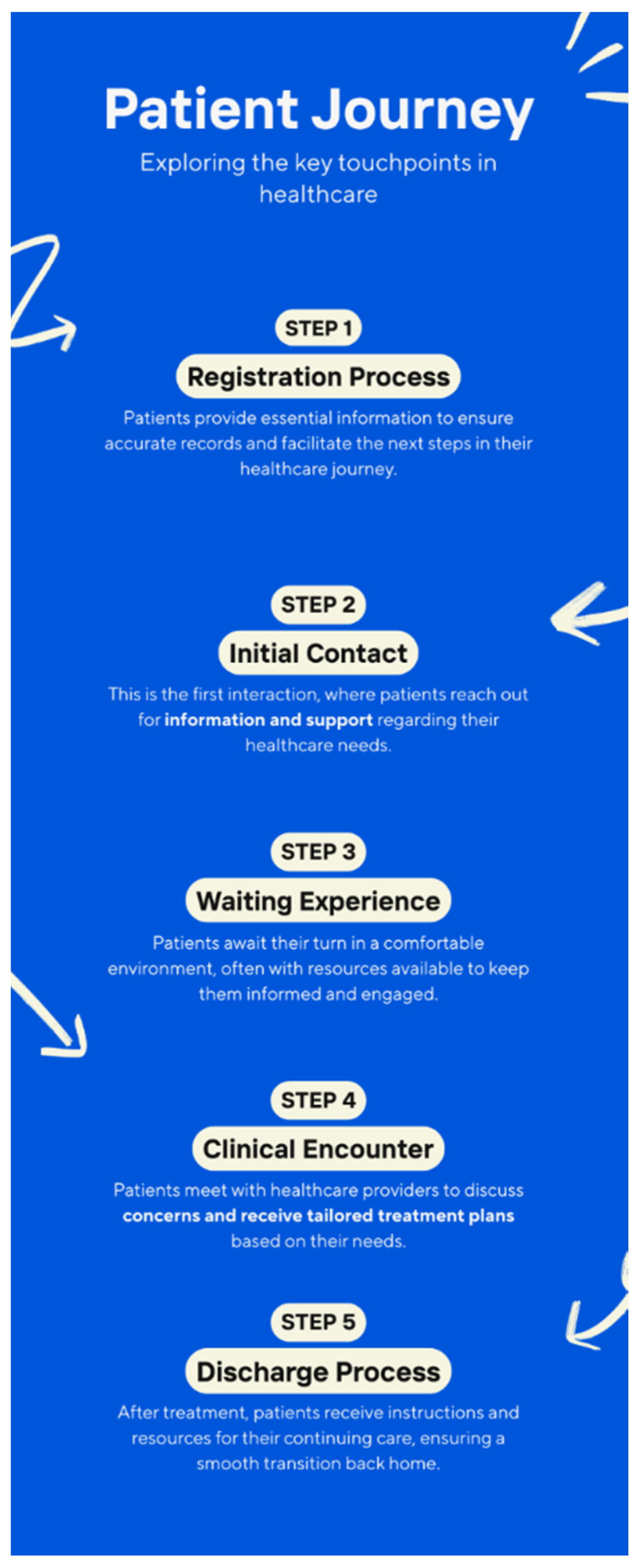

The patient journey within a healthcare facility is composed of multiple moments, each point is an opportunity to either strengthen or weaken trust, comfort, and satisfaction. These touchpoints form a continuum that begins before the patient enters the hospital and continues long after discharge. Understanding and optimizing these stages is essential to delivering a seamless, empathetic healthcare experience.

The journey often begins with initial contact, which could take the form of a phone call, website visit, or a walk-in inquiry. The tone, clarity, and helpfulness of this interaction set the stage for all future perceptions. If patients are met with confusion, indifference, or delays at this point, it undermines confidence and adds anxiety even before treatment begins.

Next is the registration and admission process. This phase often involves paperwork, identity verification, and financial information, elements that can be intimidating or stressful. Friendly, patient staff who guide individuals through this process with respect and transparency can help ease tensions and promote a sense of being cared for.

Once registered, patients move into the waiting experience, where emotions like worry and discomfort often surface. A clean, organized, and calming environment, paired with clear communication about waiting times and procedures, demonstrates respect for the patient’s time and dignity. This seemingly passive moment is, in reality, a powerful indicator of service quality.

The clinical encounter interactions with nurses, doctors, and other healthcare providers are the most critical touchpoint. It’s where trust is either deepened or eroded. Patients value clinicians who not only diagnose and treat but who also listen, explain, and empathize. Good customer service in this context means clear communication, cultural sensitivity, and a commitment to shared decision-making.

After treatment, the discharge process represents a crucial handover. It includes instructions, medications, follow-up appointments, and sometimes financial settlements. A rushed or unclear discharge can leave patients feeling unprepared and abandoned. Conversely, a well-orchestrated exit that anticipates questions and affirms continued support reflects a strong service culture.

The journey continues with post-care follow-up, which may include phone calls, emails, or telehealth check-ins. These interactions are often overlooked but play a vital role in recovery and ongoing patient satisfaction. They reassure patients that they have not been forgotten and that their healing remains a shared priority.

Each of these touchpoints is an opportunity to either reinforce or damage a patient’s trust in the healthcare system. Together, they form a mosaic of experience where attentive customer service transforms care from a clinical transaction into a meaningful, healing relationship. By mapping and intentionally improving these stages, healthcare institutions can design more compassionate, efficient, and patient-centered services that support long-term loyalty and better health outcomes.

Figure 1.

Five Critical Touchpoints.

Figure 1.

Five Critical Touchpoints.

2.1. Global Service Gaps in Healthcare

Despite advancements in healthcare delivery and the growing recognition of the importance of patient-centered care, service gaps persist across hospitals worldwide. These gaps often undermine the quality of patient experiences and can significantly impact health outcomes, even in well-resourced environments [

11]. Understanding these common service gaps is essential for identifying areas that require improvement and innovation [

21].

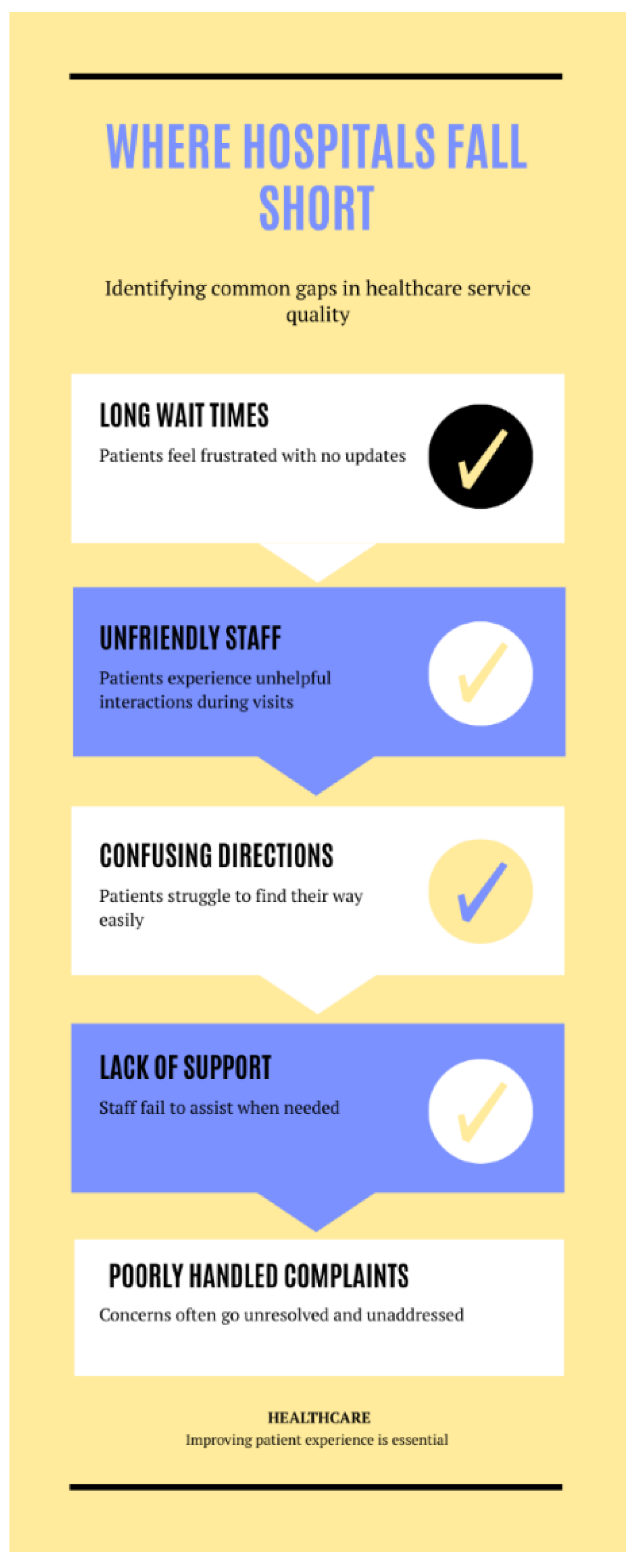

One of the most prevalent gaps is the lack of timely access to care. In many regions, patients encounter long waiting times for appointments, delays in emergency services, and extended periods before diagnostic results are available [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12]. These delays not only cause frustration but also jeopardize health, especially in time-sensitive cases [

5].

Another widespread issue is poor communication between healthcare providers and patients. Patients frequently report not being adequately informed about their diagnoses, treatment options, or medication instructions. This communication gap can lead to confusion, non-compliance with medical advice, and a general sense of neglect. Cultural and language differences further compound this problem, especially in multicultural societies or countries with diverse populations.

There is also a global inconsistency in staff attitudes and emotional intelligence. While many healthcare professionals are highly skilled clinically, some lack the soft skills needed to interact with patients empathetically. Dismissive behavior, lack of courtesy, or indifference to patients’ concerns can create emotional distress and erode trust, regardless of the quality of the clinical care provided [

8].

Infrastructure and facility management are additional areas where service gaps are evident [

21]. Outdated equipment, insufficient cleanliness, lack of signage, or uncomfortable waiting areas can all contribute to a negative patient experience. In lower-income countries, this may stem from limited funding, while in higher-income regions, bureaucratic inefficiencies or poor planning may be to blame [

18].

Digital inequality represents another growing gap. As hospitals increasingly rely on technology for patient portals, telemedicine, and automated systems, not all patients are equally equipped to navigate these tools [

12]. Older adults, those with limited digital literacy, and patients in rural areas without strong internet connectivity often struggle to benefit from these technological innovations, creating a divide in access and service quality [

20].

Coordination between departments within hospitals is frequently cited as a pain point. A lack of internal communication can lead to misplaced test results, duplicate procedures, or misaligned care plans [

14]. Patients may feel like they are repeating themselves at every step or being passed from one department to another without proper handover or context [

6].

Lastly, follow-up care is a neglected area in many healthcare systems [

1]. After patients leave the hospital, they often receive little to no communication regarding their recovery, medication, or the need for further appointments [

7]. This absence of continuity increases the risk of readmissions, complications, or feelings of abandonment.

These common global service gaps highlight the importance of approaching healthcare not just as a clinical obligation but as a comprehensive human experience [

17]. Bridging these gaps requires commitment, innovation, and leadership from healthcare institutions and policymakers worldwide [

13]. The path to better healthcare begins with listening to patients, valuing their experiences, and acting decisively to eliminate the barriers that stand in the way of compassionate, efficient, and equitable service [

16].

Figure 2.

Five Global Service Gaps in Healthcare.

Figure 2.

Five Global Service Gaps in Healthcare.

2.2. Global Perspectives on Service Delivery

Healthcare service delivery varies widely across the globe, shaped by cultural values, economic resources, political systems, and public expectations [

2]. Yet, despite these differences, a common global aspiration persists: to provide care that is accessible, respectful, and responsive to the needs of every patient [

9]. By examining how different regions approach healthcare service delivery, valuable insights emerge into both innovative practices and shared challenges [

13].

In countries with universal healthcare systems such as the United Kingdom, Canada, and many in Western Europe, the focus often lies on equity and access. These systems are designed to ensure that all citizens receive care without financial hardship [

16]. However, they sometimes struggle with long wait times, overstretched resources, and bureaucracy, which can dilute the quality of the patient experience [

10]. Customer service initiatives in these regions often aim to improve efficiency, enhance provider communication, and personalize care within the constraints of a publicly funded system [

19].

In the United States, where healthcare is largely privatized, service delivery is often influenced by competition [

7]. Hospitals and clinics invest heavily in customer service to attract and retain patients. This has led to innovations such as concierge services, luxury birthing suites, digital patient engagement platforms, and personalized wellness plans [

12]. However, disparities in care remain a major issue, with access heavily dependent on insurance coverage and socioeconomic status.

Here, customer service excellence can coexist with unequal treatment access, highlighting the need for both structural reform and service refinement [

16].

In middle-income countries such as India, Brazil, and South Africa, a dual-system approach exists where both public and private sectors operate concurrently. While public hospitals aim to serve the masses, they often suffer from underfunding and congestion, resulting in lower service quality [

18]. In contrast, private facilities cater to those who can afford higher costs, offering faster, more comfortable, and more personalized services. The gap between these two tiers creates tension in service delivery, as national health goals strive to bring consistency and fairness across socioeconomic classes [

16].

Asian countries like Japan, South Korea, and Singapore offer compelling models of efficient service delivery. These nations combine strong government regulation, cutting-edge technology, and a cultural emphasis on respect and order [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13]. In Japan, for example, the patient-provider interaction is guided by deep-rooted traditions of politeness and dignity, while Singapore’s digitized healthcare system ensures fast and coordinated care [

12]. These countries demonstrate that integrating cultural values with modern systems can produce highly effective service environments [

14].

In many parts of Africa and Southeast Asia, healthcare systems face enormous challenges, including workforce shortages, limited infrastructure, and funding constraints [

5]. Despite these hurdles, there are growing efforts to improve service delivery through community health initiatives, mobile health units, and international partnerships [

13]. Countries like Rwanda and Ghana have made significant strides in enhancing access and service quality through innovative health insurance models and community engagement. In these settings, customer service is increasingly recognized as essential, not secondary, to care delivery [

12].

Globally, the COVID-19 pandemic has acted as a catalyst for rethinking healthcare service models. It forced hospitals around the world to adopt virtual consultations, streamline patient flow, and strengthen communication channels - all key elements of good customer service [

16]. From urban hospitals in Europe to rural clinics in Latin America, the crisis exposed weaknesses and prompted systemic change toward more agile, patient-responsive care models [

5].

Ultimately, global perspectives on healthcare service delivery reveal that while each system has unique strengths and weaknesses, the human need for compassionate, respectful, and efficient care is universal [

17]. Learning from each other’s successes and failures offers a path forward - one where best practice can be adapted, scaled, and localized to improve service experiences across diverse healthcare landscapes.

Figure 3.

Perspectives on Service Delivery.

Figure 3.

Perspectives on Service Delivery.

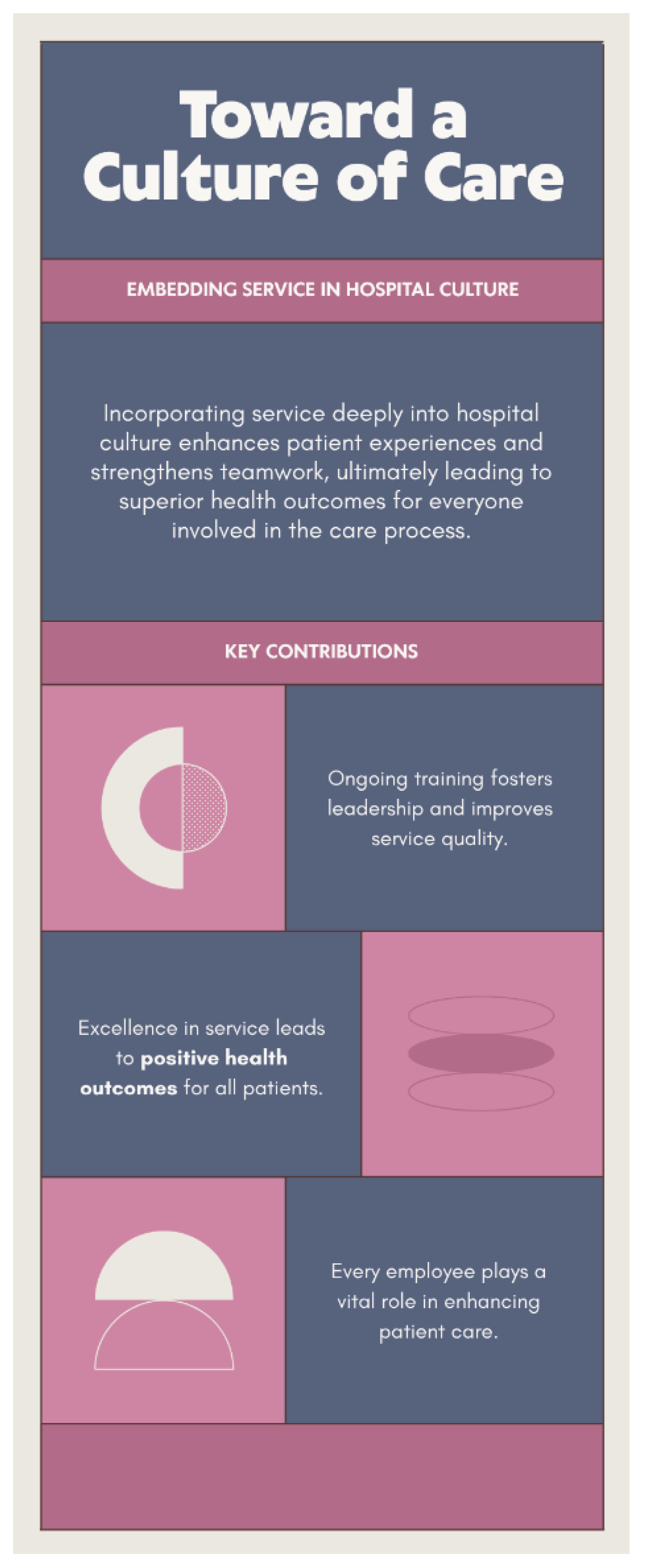

2.3. Toward a Culture of Care

Transforming healthcare service delivery is not merely about systems and procedures. It is about shaping a deeper organizational ethos that consistently places the patient at the heart of every decision [

11]. A culture of care transcends transactional service encounters and embeds compassion, dignity, and responsiveness into the fabric of daily hospital life [

19]. While policies and technologies may guide structure, it is the people, values, and mindset within an institution that determine the real quality of care experienced by patients [

10].

At its core, a culture of care begins with leadership. When hospital leaders and administrators visibly champion empathy, fairness, and respect, they set the tone for everyone else [

21]. This culture cascades down through every department, influencing how staff interact with patients, how problems are solved, and how improvement is pursued. Leadership that listens to both patients and staff, that embraces feedback, and that remains open to change is essential to sustaining meaningful service transformation [

5].

A culture of care is also defined by shared ownership of the patient experience. It is not only the job of doctors and nurses to ensure that patients feel seen, heard, and valued [

4,

5]. Everyone be it receptionists, cleaners, pharmacists, porters, security personnel play a role in shaping how patients perceive and experience the healthcare environment [

7]. When every team member understands that they contribute to healing, a collective sense of purpose emerges [

9].

Training and education are critical enablers of this cultural shift. Soft skills such as active listening, conflict resolution, cultural competence, and emotional intelligence must be continually developed [

2]. These skills do not come automatically with medical expertise, yet they are crucial in fostering trust and comfort. Institutions that integrate customer service principles into clinical and non-clinical training tend to build stronger, more respectful relationships between caregivers and patients [

8].

Equally important is the way organizations recognize and reward compassionate service. Celebrating staff who go the extra mile reinforces the behaviors that embody a culture of care [

10]. Recognition programs, feedback loops, and open communication channels all help staff feel valued and motivated [

3]. When staff feel respected and supported, they are more likely to extend the same warmth and attentiveness to those in their care [

3].

Another hallmark of a culture of care is the continuous pursuit of patient feedback and co-design. Patients are not passive recipients; they are experts in their own experience [

12]. Institutions that invite patients to help shape services, participate in planning, and review systems from their perspective tend to deliver more responsive and meaningful care. This inclusivity builds mutual respect and strengthens trust in the healthcare system [

13,

14].

Lastly, a true culture of care is resilient and adaptable. In times of crisis like the COVID-19 pandemic healthcare systems were tested not only in terms of capacity but also in compassion [

7]. Those that had already invested in empathy-driven systems were better able to reassure, communicate with, and protect their patients and staff. Building a culture of care is thus not a luxury, but a necessity for preparedness, sustainability, and long-term success [

15].

In moving toward this vision, hospitals around the world must reflect not just on what services they provide, but how they provide them [

19]. The journey toward a culture of care is ongoing, but with intention and leadership, it can reshape the global standard for what healthcare truly means [

16].

Figure 4.

A Culture of Care.

Figure 4.

A Culture of Care.

3. Conclusion

At the heart of every successful healthcare experience lies a foundation of trust. Trust that the patient’s needs will be understood, respected, and prioritized throughout their care journey [

12]. Customer service in healthcare is far more than a courtesy; it is a critical pillar that supports this trust. When hospitals deliver compassionate, efficient, and patient-centered service, they create an environment where patients feel safe and valued, empowering them to engage actively in their own health [

1].

Trust is earned not in a single moment but through consistent positive interactions, clear communication, and demonstrated commitment to patient well-being [

18]. Each touchpoint in the patient journey whether the first greeting at reception, the clarity of clinical explanations, or the attentiveness during follow-up care contributes to this fragile yet vital bond [

7].

Building trust through service also means acknowledging and addressing barriers that patients face, from long wait times and confusing processes to cultural and language differences [

19]. When healthcare providers actively listen and respond with empathy, they affirm the dignity of every individual, fostering loyalty and improving health outcomes.

Moreover, trust extends beyond the patient to their families and communities, amplifying the hospital’s reputation and encouraging broader public engagement [

17]. In a world increasingly defined by choice and competition, excellent customer service becomes a strategic advantage, shaping not just satisfaction but long-term relationships and community health [

13].

Figure 5.

Steps to Build Thrust Through Service.

Figure 5.

Steps to Build Thrust Through Service.

Ultimately, investing in customer service is investing in the very essence of healthcare; the human connection. It is through this connection that hospitals can transform care from a transactional necessity into a healing experience. By building trust through every service interaction, healthcare institutions worldwide can move closer to the ideal of truly patient-centered care.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

There is conflict of interest.

References

- Shie, A. J., Huang, Y. F., Li, G. Y., Lyu, W. Y., Yang, M., Dai, Y. Y., ... & Wu, Y. J. (2022). Exploring the relationship between hospital service quality, patient trust, and loyalty from a service encounter perspective in elderly with chronic diseases. Frontiers in public health, 10, 876266.

- Endeshaw, B. (2021). Healthcare service quality-measurement models: a review. Journal of Health Research, 35(2), 106-117.

- Ferreira, D. C., Vieira, I., Pedro, M. I., Caldas, P., & Varela, M. (2023, February). Patient satisfaction with healthcare services and the techniques used for its assessment: a systematic literature review and a bibliometric analysis. In Healthcare (Vol. 11, No. 5, p. 639). Mdpi.

- Abdulrab, M., & Hezam, N. (2024). Service Quality and Customer Satisfaction in the Hospitality Sector: A paper review and future research directions. Library of Progress-Library Science, Information Technology & Computer, 44(3).

- Danaher, T. S., Berry, L. L., Howard, C., Moore, S. G., & Attai, D. J. (2023). Improving how clinicians communicate with patients: an integrative review and framework. Journal of Service Research, 26(4), 493-510.

- AlOmari, F. (2021). Measuring gaps in healthcare quality using SERVQUAL model: challenges and opportunities in developing countries. Measuring Business Excellence, 25(4), 407-420.

- Tian, Y. (2023). A review on factors related to patient comfort experience in hospitals. Journal of Health, Population and Nutrition, 42(1), 125.

- Hofmeyer, A., & Taylor, R. (2021). Strategies and resources for nurse leaders to use to lead with empathy and prudence so they understand and address sources of anxiety among nurses practising in the era of COVID-19. Journal of clinical nursing, 30(1-2), 298-305.

- Bald, S. M. (2022). Factors influencing dignity in sub-Saharan African health systems: a qualitative systematic review.

- Sharma, K., Trott, S., Sahadev, S., & Singh, R. (2023). Emotions and consumer behaviour: A review and research agenda. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 47(6), 2396-2416.

- Hsu, C. H., Chen, N., & Zhang, S. (2024). Emotion regulation research in hospitality and tourism. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 36(6), 2069-2085.

- Kaur, M., & Kumar, M. (2024). Facial emotion recognition: A comprehensive review. Expert Systems, 41(10), e13670.

- Levine, D. S., & Drossman, D. A. (2022). Addressing misalignments to improve the US health care system by integrating patient-centred care, patient-centred real-world data, and knowledge-sharing: a review and approaches to system alignment. Discover Health Systems, 1(1), 8.

- Fukami, T., & FUKAMI, T. (2024). Enhancing healthcare accountability for administrators: Fostering transparency for patient safety and quality enhancement. Cureus, 16(8).

- Ramar, K., Oxentenko, A. S., & Dowdy, S. C. (2025, July). Transforming Health Care Through Quality and Safety. In Mayo Clinic Proceedings. Elsevier.

- Lei, N. J., Vaishnani, D. K., Shaheen, M., Pisheh, H., Zeng, J., Ying, F. R., ... & Hou, N. J. (2025). Embedding narrative medicine in primary healthcare: Exploration and practice from a medical humanities perspective. World Journal of Clinical Cases, 13(22).

- Datt, M., Gupta, A., & Misra, S. K. (2025). Advances in management of healthcare service quality: a dual approach with model development and machine learning predictions. Journal of Advances in Management Research.

- Limiri, D. M. (2025). The Impact of Long Wait Times on Patient Health Outcomes: The Growing NHS Crisis. Premier Journal of Public Health.

- Rathnayake, D., & Clarke, M. (2021). The effectiveness of different patient referral systems to shorten waiting times for elective surgeries: systematic review. BMC health services research, 21(1), 155.

- Sartini, M., Carbone, A., Demartini, A., Giribone, L., Oliva, M., Spagnolo, A. M., ... & Cristina, M. L. (2022, August). Overcrowding in emergency department: causes, consequences, and solutions—a narrative review. In Healthcare (Vol. 10, No. 9, p. 1625). MDPI.

- Carini, E., Villani, L., Pezzullo, A. M., Gentili, A., Barbara, A., Ricciardi, W., & Boccia, S. (2021). The impact of digital patient portals on health outcomes, system efficiency, and patient attitudes: updated systematic literature review. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 23(9), e26189.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).