Submitted:

14 July 2025

Posted:

16 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Research Object and Strategy

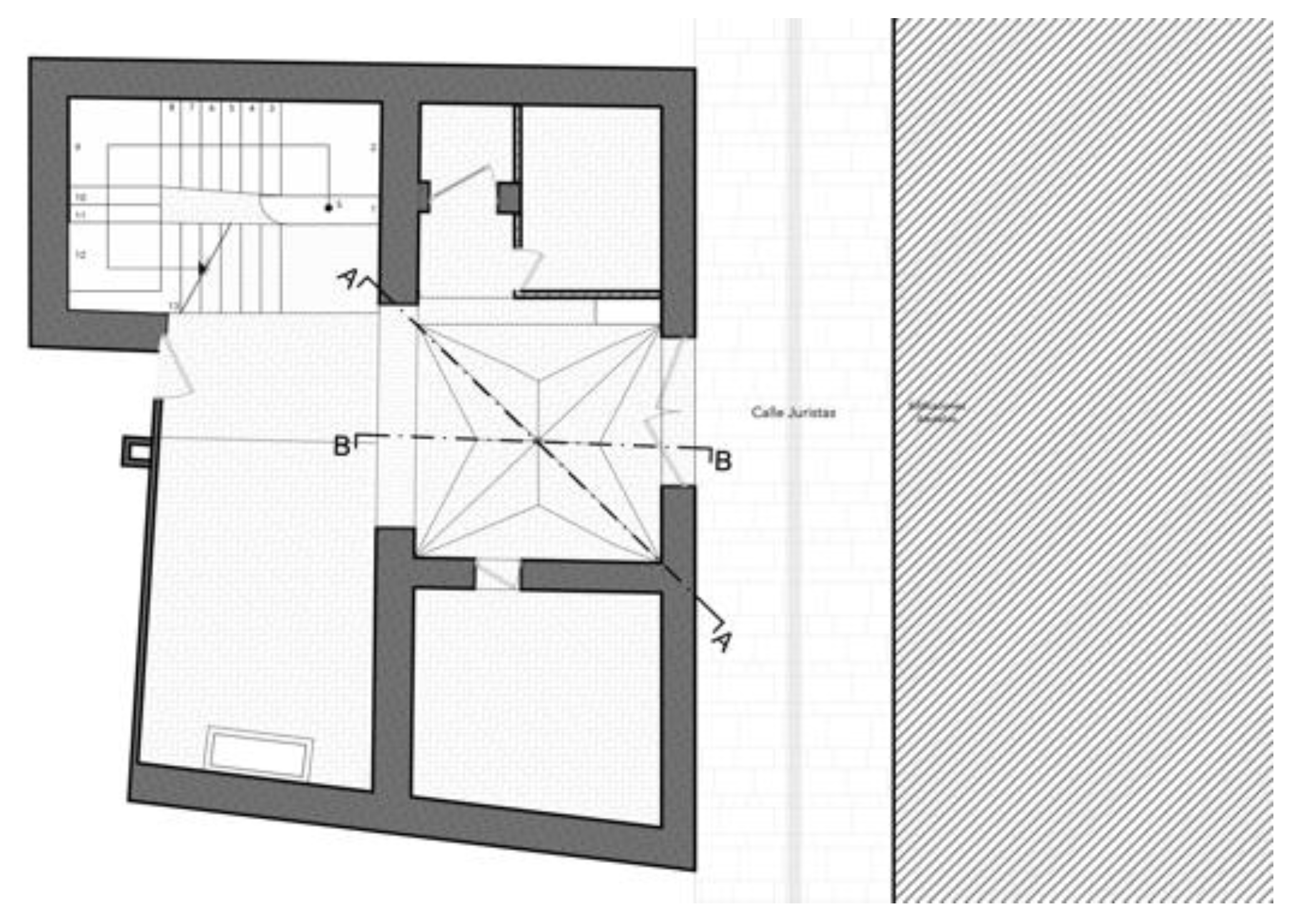

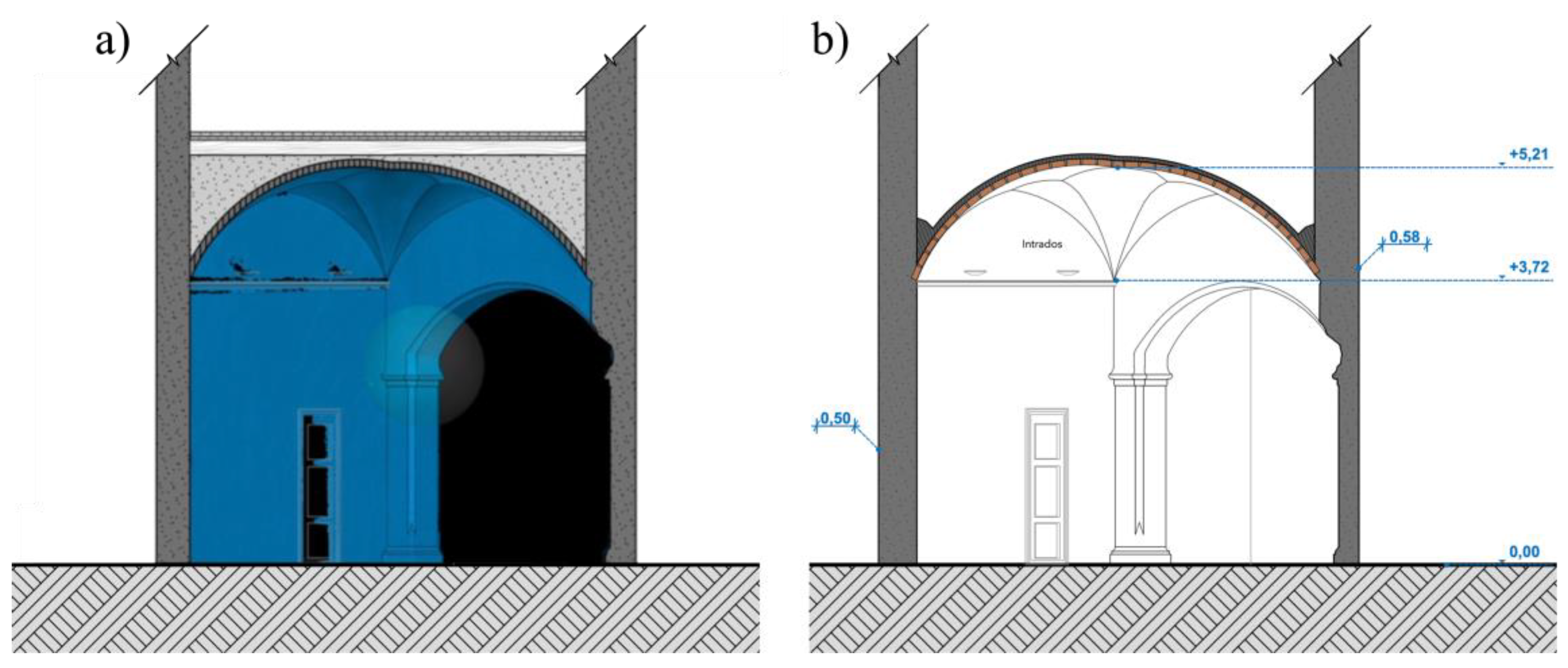

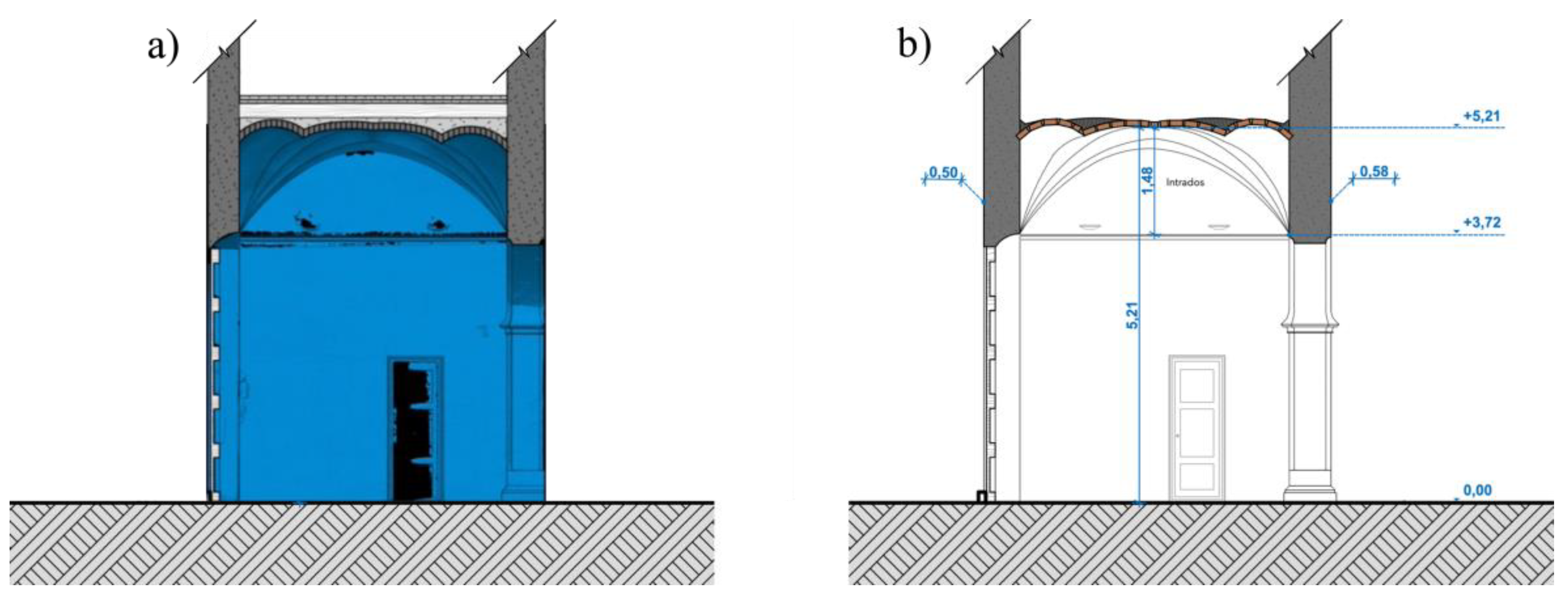

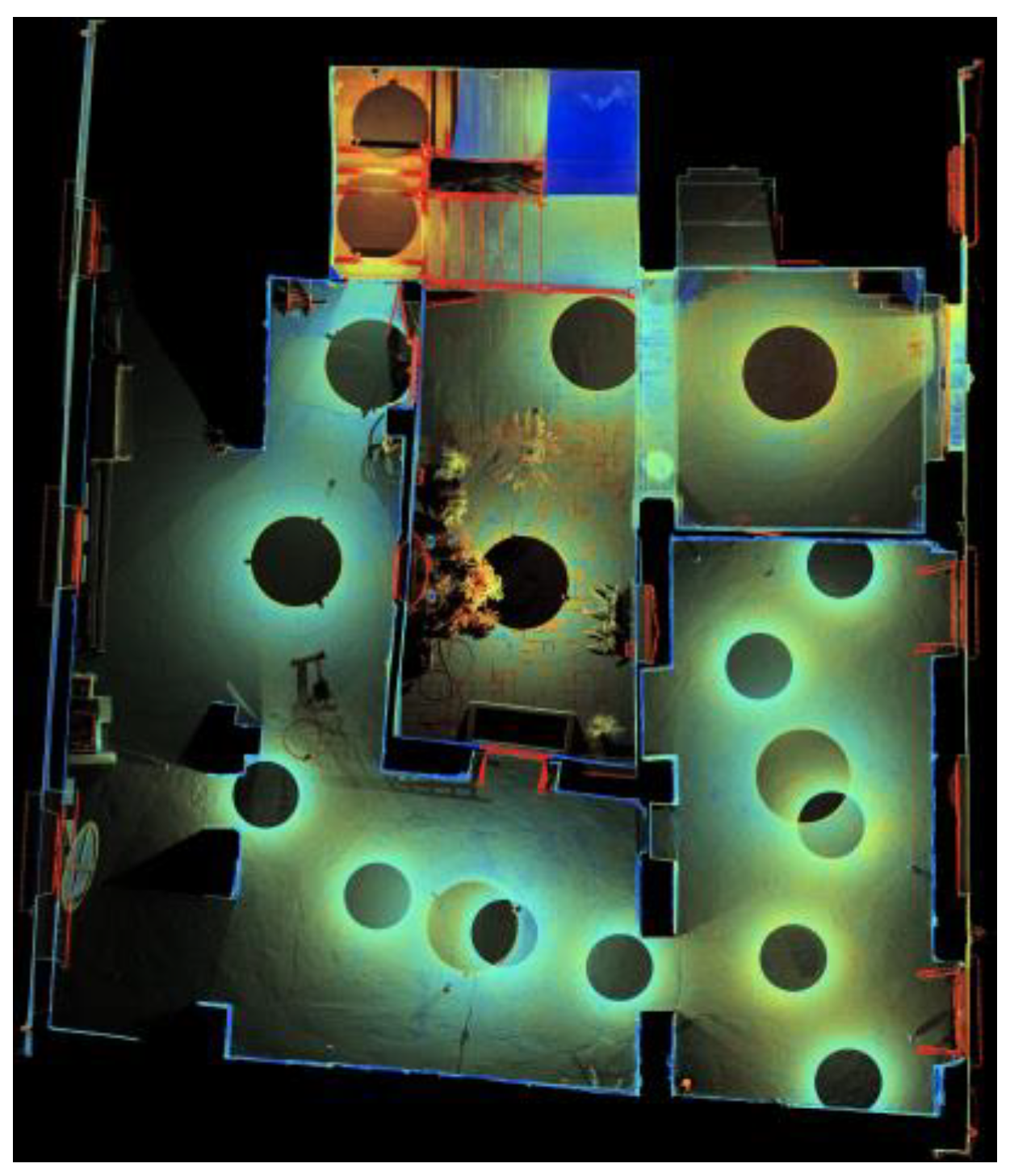

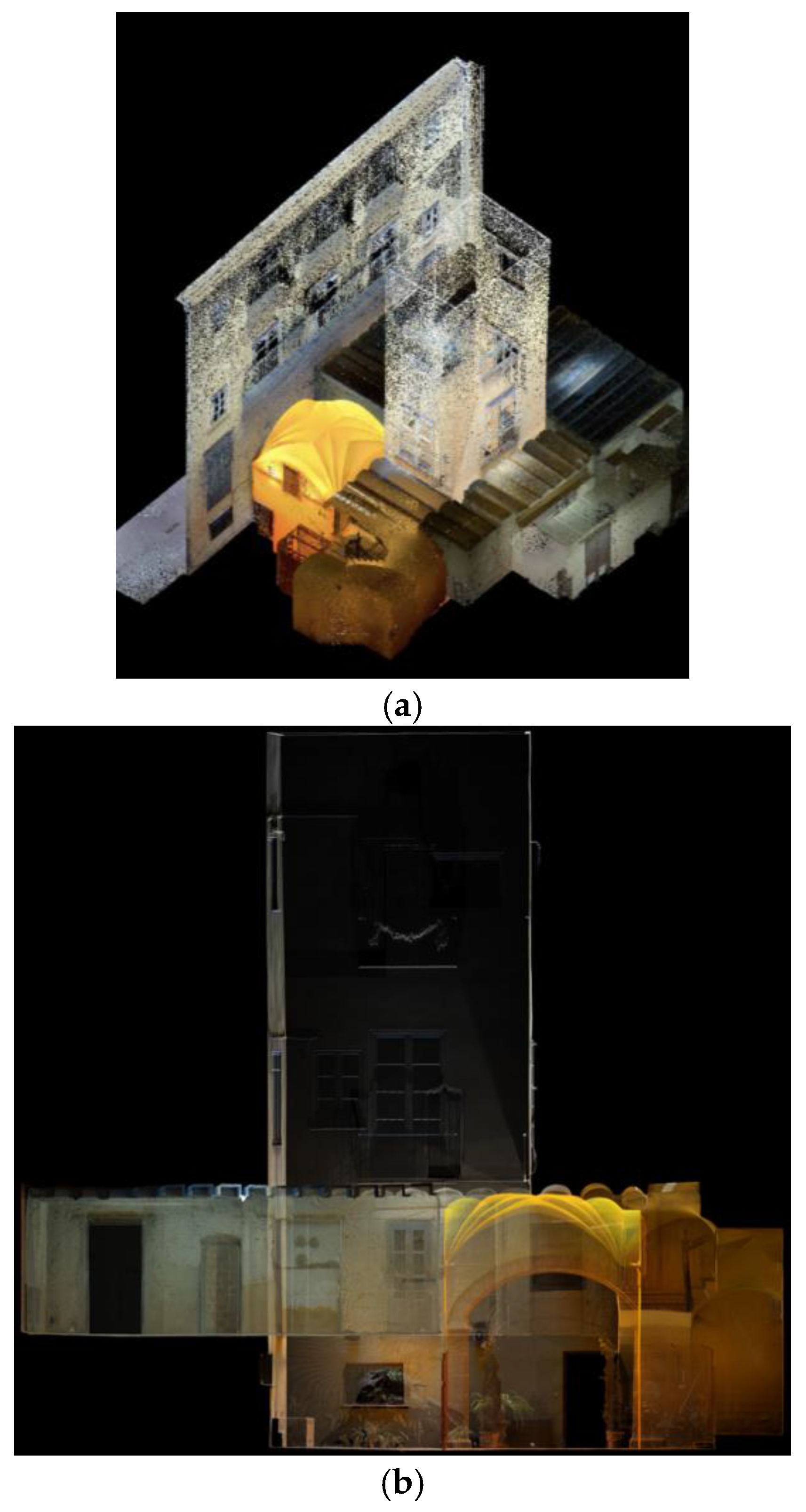

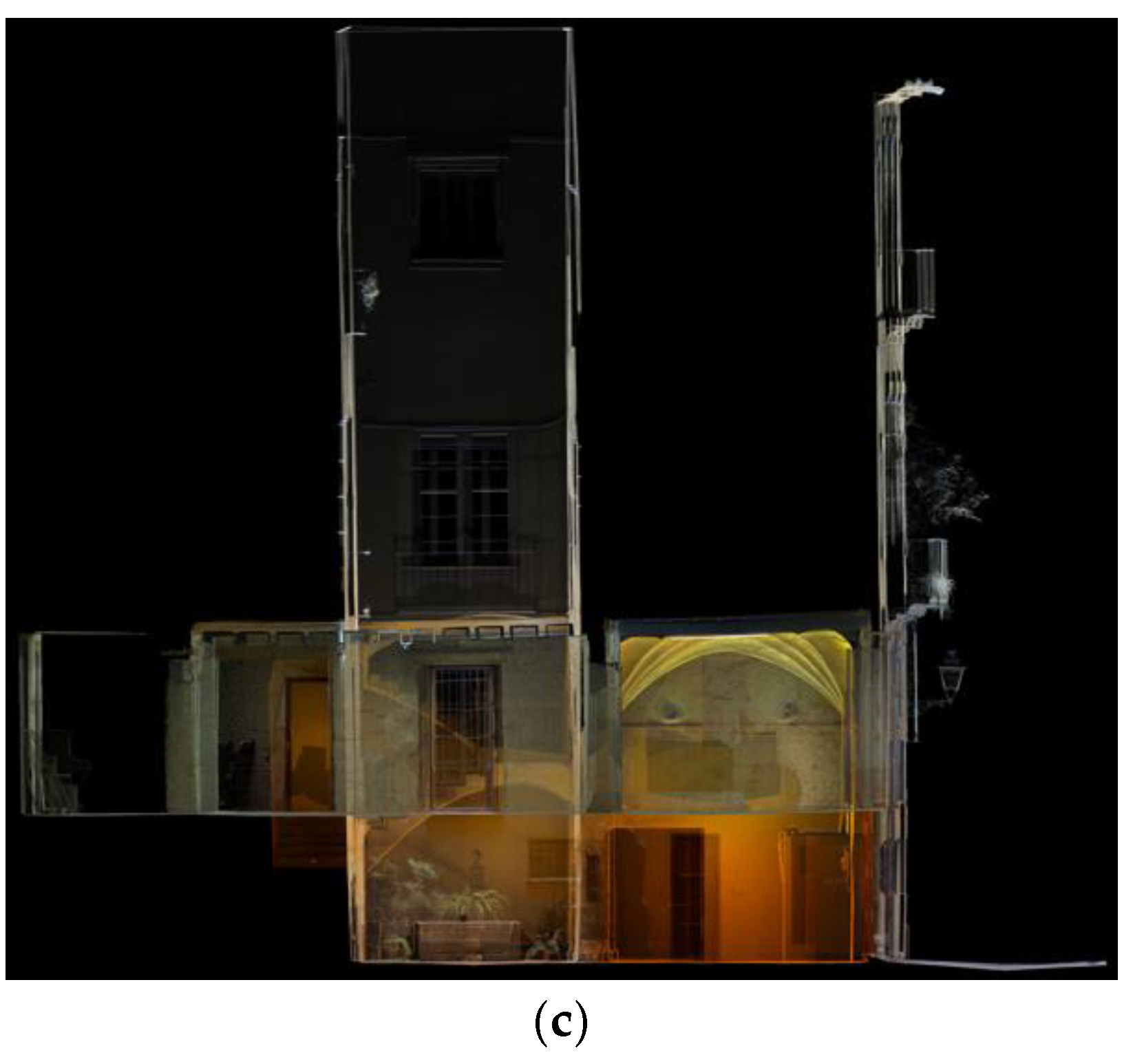

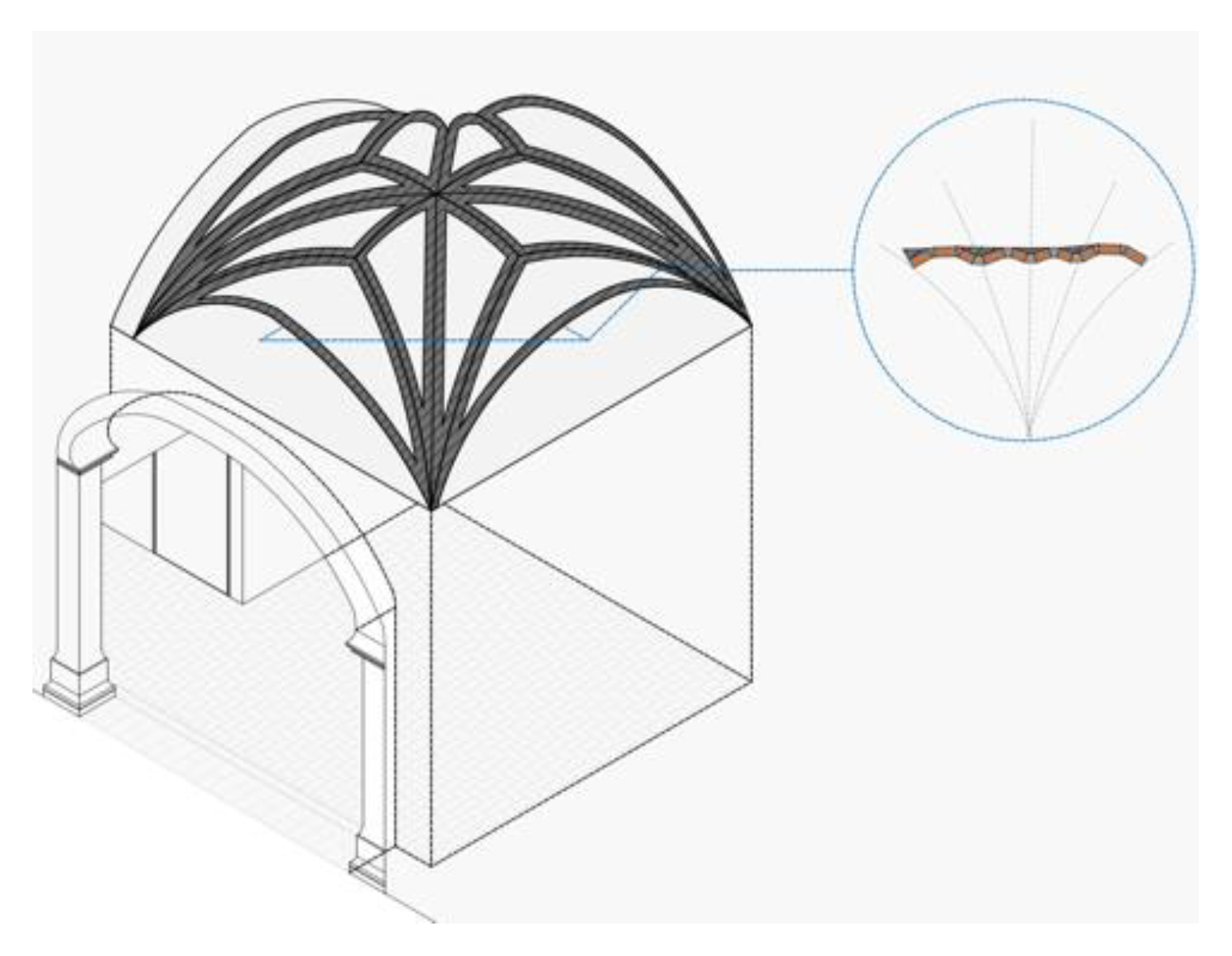

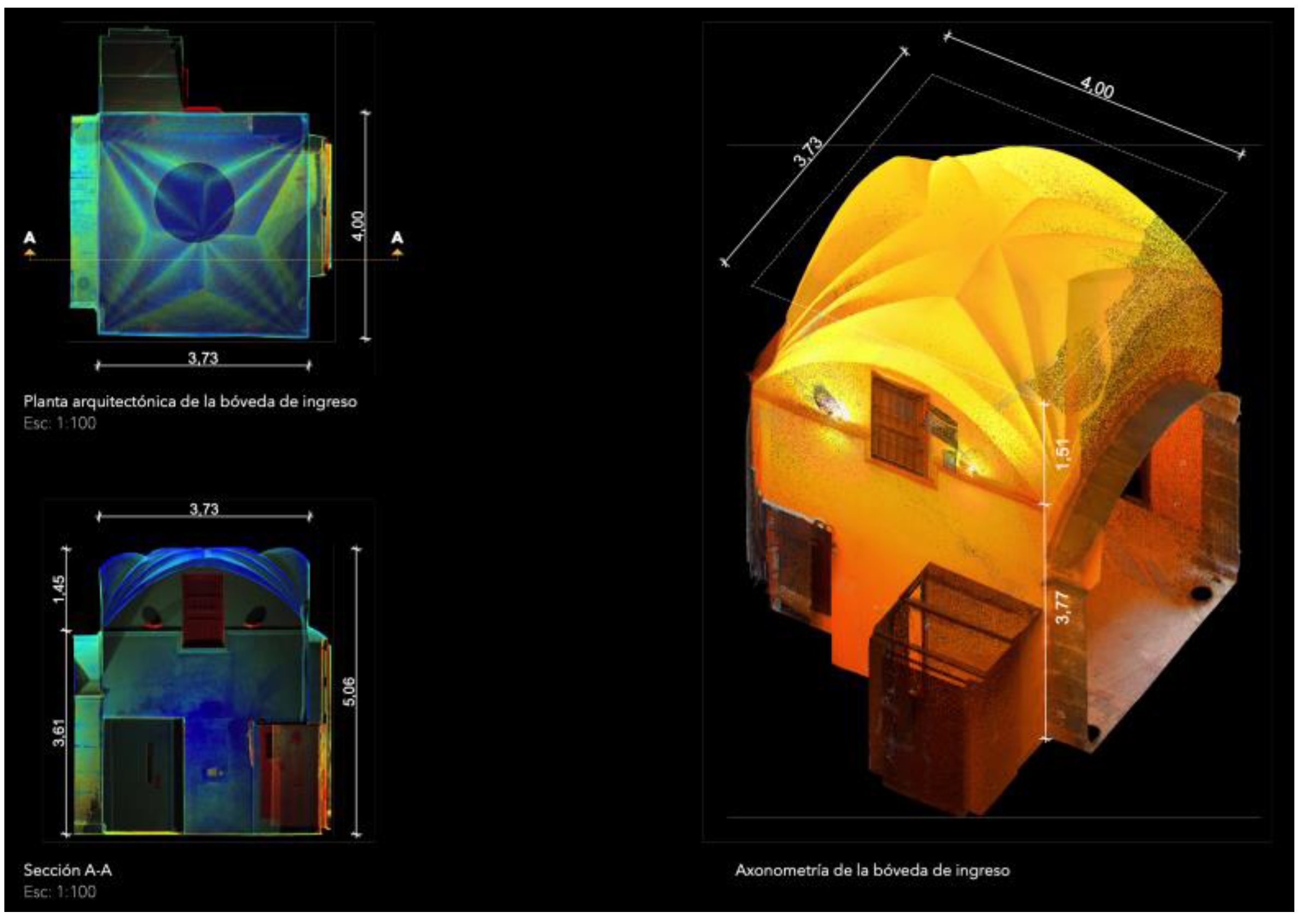

2. Lifting strategy

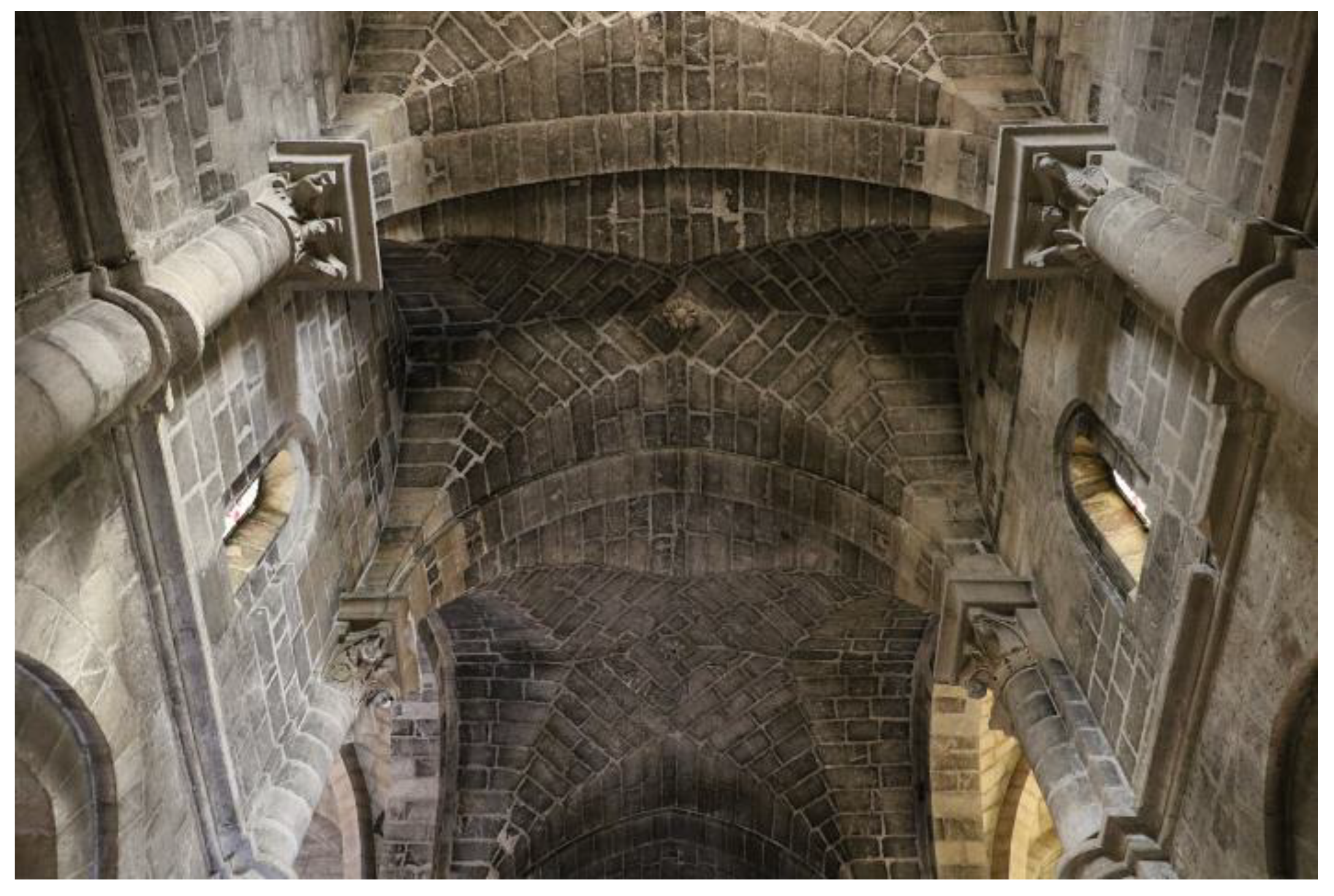

3. La Bóveda Estrellada Entre la Tradición Gótica y El Contexto Meridional

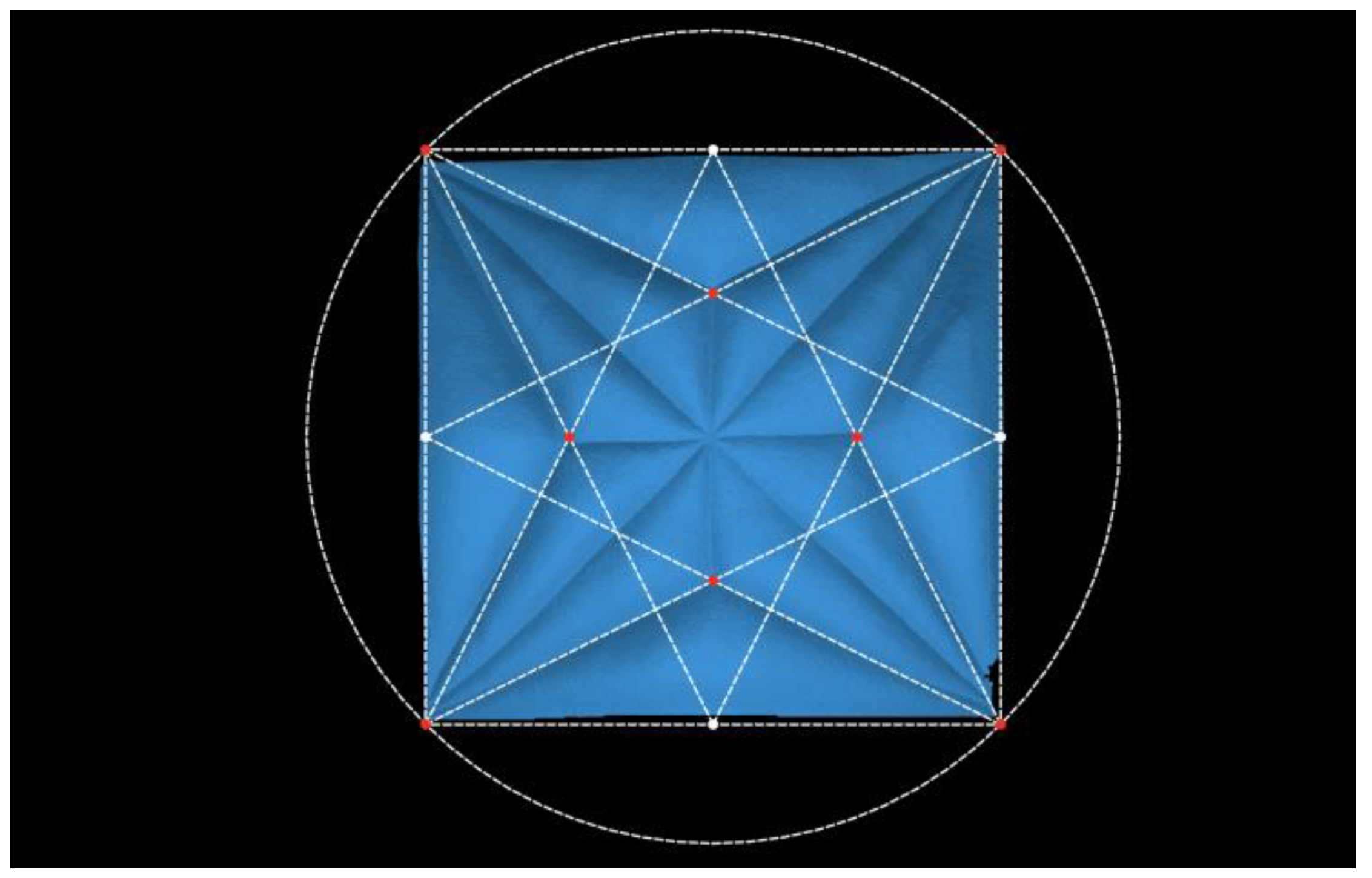

4. Formal Matters

5. Constructive Questions

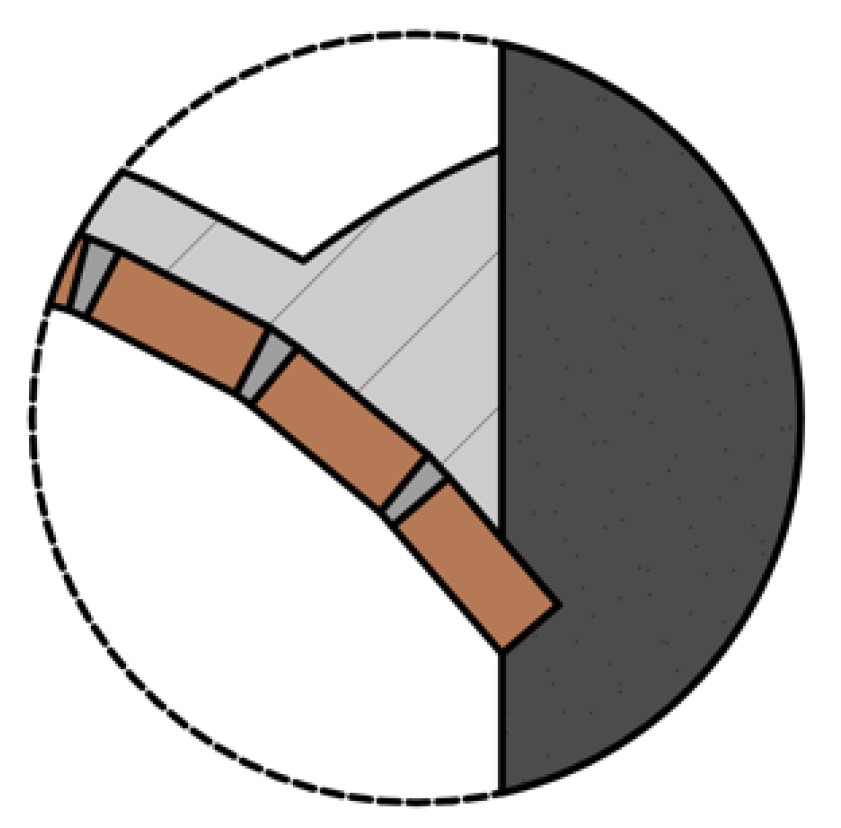

6. The Crown of Aragon and the Valencian Context

7. The Grooved Vaults

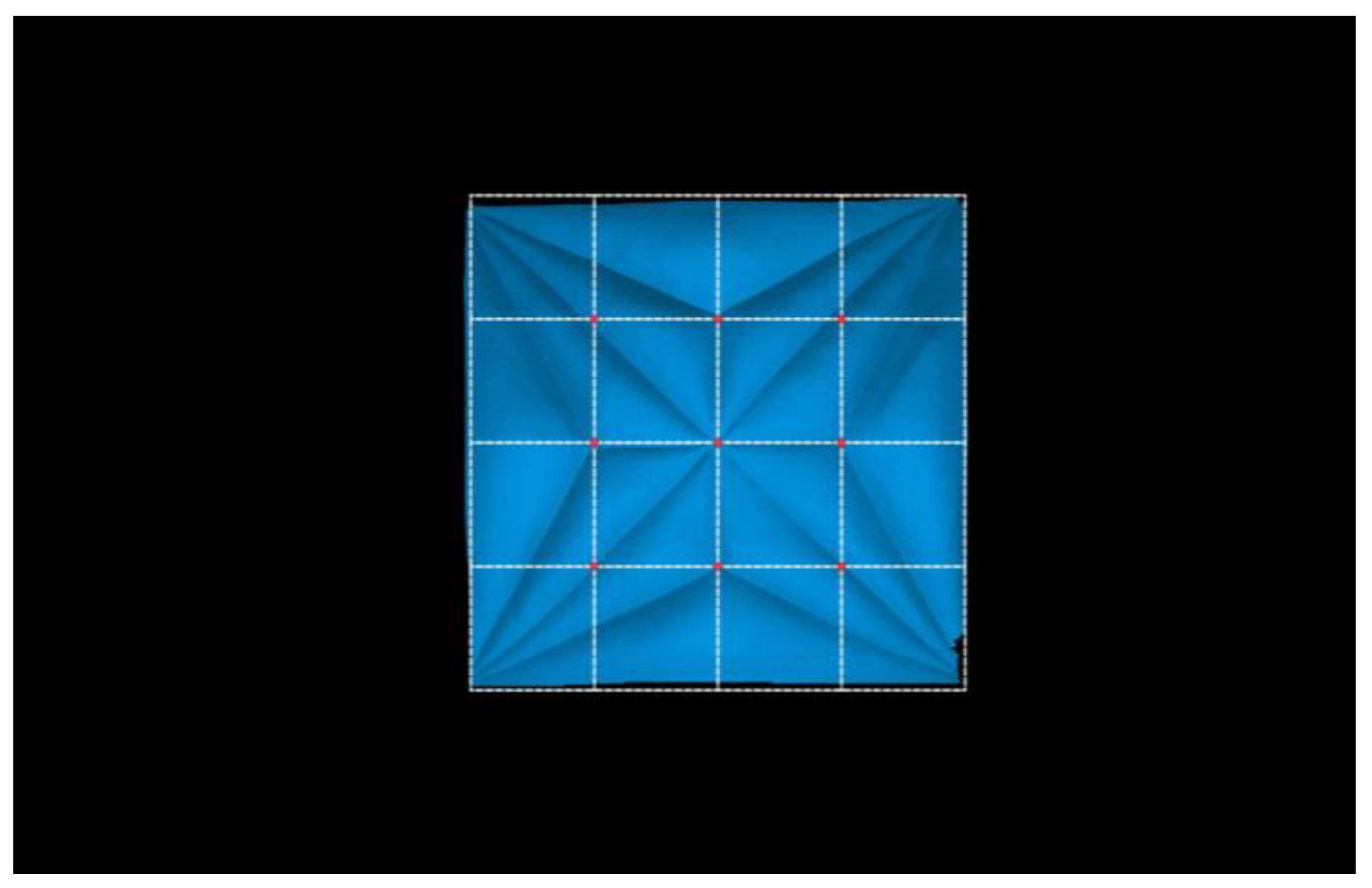

8. The Partitioning Technique Applied to Star Vaults

9. The Case of the Vault of the Más Palace

10. Análisis Formal

11. Restitution of the Trace

12. Constructive Analysis

13. Conclusions

13.1. Methodological Conclusions

13.2. Conclusions of the Analysis of the Vault

| 1 | Barrón García, Aurelio A., “bóvedas con figuras de estrellas y combados del |

| 2 | Tardogótico en la Rioja”. TVRIASO XXI, p. 222. |

| 3 | Barrón García, Aurelio A., “bóvedas con figuras de estrellas y combados del |

| 4 | Tardogótico en la Rioja”. TVRIASO XXI, p. 225. |

| 5 | Bertachi, Silvia, “Modelos de bóvedas en estrella: forma y geometría”. En Juan Carlos Navarro Fajardo (ed.), Bóvedas valencianas. Arquitecturas ideales, reales y virtuales en época medieval y moderna, Editorial Universitat Politécnica de Valencia, Valencia 2014, p. 138. |

| 6 | Palacios Gonzalo, José Carlos, “Las bóvedas de crucería españolas, ss. XV y XVI”. En A. Graciani, S. Huerta, E. Rabasa, M. Tabales (eds.). Actas del Tercer Congreso Nacional de Historia de la Construcción, Sevilla, 26-28 octubre 2000, eds., Madrid: I. Juan de Herrera, SEdHC, Universidad de Sevilla, Junta Andalucía, COAAT Granada, CEHOPU, 2000, p. 749. |

| 7 | Tellia, Fabio y Palacios, José Carlos, “Las bóvedas de crucería del manuscrito Llibre de trasas de viax y muntea, de Joseph Ribes”, LOCVS AMOENVS 13, 2015, p. 33. |

| 8 | Bertachi, Silvia, “Modelos de bóvedas en estrella: forma y geometría”. En Juan Carlos Navarro Fajardo (ed.), Bóvedas valencianas. Arquitecturas ideales, reales y virtuales en época medieval y moderna, Editorial Universitat Politécnica de Valencia, Valencia 2014, p. 145. |

| 9 | Bertachi, Silvia, “Modelos de bóvedas en estrella: forma y geometría”. En Juan Carlos Navarro Fajardo (ed.), Bóvedas valencianas. Arquitecturas ideales, reales y virtuales en época medieval y moderna, Editorial Universitat Politécnica de Valencia, Valencia 2014, p. 140. |

| 10 | Pecoraro, Ilaria, “Las bóvedas estrelladas del Salento. Una arquitectura a caballo entre la edad media y la edad moderna”. En Eduard Mira y Arturo Zaragozá Catalán (com.), Una arquitectura gótica mediterránea Vol. II, Generalidad valenciana, Valencia, 2003, p. 59. |

| 11 | Pecoraro, Ilaria, “Las bóvedas estrelladas del Salento. Una arquitectura a caballo entre la edad media y la edad moderna”. En Eduard Mira y Arturo Zaragozá Catalán (com.), Una arquitectura gótica mediterránea Vol. II, Generalidad valenciana, Valencia, 2003, p. 59. |

| 12 | Bertachi, Silvia, “Modelos de bóvedas en estrella: forma y geometría”. En Juan Carlos Navarro Fajardo (ed.), Bóvedas valencianas. Arquitecturas ideales, reales y virtuales en época medieval y moderna, Editorial Universitat Politécnica de Valencia, Valencia 2014, p. 139. |

| 13 | Martínez-Espejo Zaragoza, Isabel. “Técnicas de levantamiento con escáner láser del patrimonio arquitectónico. Hipótesis y restitución virtual de la bóveda de una iglesia”. En José Antonio Melgares Guerrero y Pedro Enrique Collado Espejo (dirs. congr.). XXII Jornadas de patrimonio cultural de la Región de Murcia: (4 de Octubre - 8 de Noviembre de 2011) Cartagena, Murcia, 2011, pp. 275-284. |

| 14 | Navarro Fajardo, Juan Carlos, “La lonja de valencia a la luz de las trazas de |

| 15 | Montea”, ARCHÉ. publicación del instituto universitario de restauración del patrimonio de la UPV - Núms. 4 y 5 – 2010, pp. 245-253. |

| 16 | Palacios Gonzalo, José Carlos, La geometría de la bóveda de crucería española del XVI. Conferencia leída en el III Seminario de bóvedas, impartido dentro del máster de restauración de la Universidad Politécnica de Valencia, Gothicmed.com. A virtual museum of mediterranean gothic arquitecture, Archivo Digital UPM, 2007, pp. s. n. Acceso en línea: https://oa.upm.es/30744/

|

| 17 | Palacios Gonzalo, José Carlos, “Las bóvedas de crucería españolas, ss. XV y XVI”. En A. Graciani, S. Huerta, E. Rabasa, M. Tabales (eds.). Actas del Tercer Congreso Nacional de Historia de la Construcción, Sevilla, 26-28 octubre 2000, eds., Madrid: I. Juan de Herrera, SEdHC, Universidad de Sevilla, Junta Andalucía, COAAT Granada, CEHOPU, 2000, pp. 743-750. |

| 18 | Palacios Gonzalo, José Carlos, “Las bóvedas de crucería españolas, ss. XV y XVI”. En A. Graciani, S. Huerta, E. Rabasa, M. Tabales (eds.). Actas del Tercer Congreso Nacional de Historia de la Construcción, Sevilla, 26-28 octubre 2000, eds., Madrid: I. Juan de Herrera, SEdHC, Universidad de Sevilla, Junta Andalucía, COAAT Granada, CEHOPU, 2000, p. 744. |

| 19 | Palacios Gonzalo, José Carlos, La geometría de la bóveda de crucería española del XVI. Conferencia leída en el III Seminario de bóvedas, impartido dentro del máster de restauración de la Universidad Politécnica de Valencia, Gothicmed.com. A virtual museum of mediterranean gothic arquitecture, Archivo Digital UPM, 2007, pp. s. n. Acceso en línea: https://oa.upm.es/30744/

|

| 20 | Chueca, Fernando. La catedral nueva de Salamanca. Historia documental de su construcción. Volumen del Acta Salmanticensia, Filosofía y Letras tomo IV, N.º 3, Salamanca, Universidad de Salamanca, 1951. |

| 21 | Zaragozá Catalán, Arturo, Arquitectura gótica valenciana siglos XIII-XV. Monumentos de la Comunidad Valenciana. Catálogo de monumentos y conjuntos declarados e incoados, Tomo I, Generalitat valenciana, Valencia, 2000, p. 174. |

| 22 | Palacios Gonzalo, José Carlos, La geometría de la bóveda de crucería española del XVI. Conferencia leída en el III Seminario de bóvedas, impartido dentro del máster de restauración de la Universidad Politécnica de Valencia, Gothicmed.com. A virtual museum of mediterranean gothic arquitecture, Archivo Digital UPM, 2007, pp. s. n. Acceso en línea: https://oa.upm.es/30744/

|

| 23 | Breymann, Gustav Adolf, Allgemeine Bau-Constructions-Lehre, mit Besonderer Beziehung auf das Hochbauwesen ein Leiftaden zu Vorlesungen und zum Selbstunterrichte. Constructionen in Metall Eisenconstrutionen (1858). |

| 24 | Bertachi, Silvia, “Modelos de bóvedas en estrella: forma y geometría”. En Juan Carlos Navarro Fajardo (ed.), Bóvedas valencianas. Arquitecturas ideales, reales y virtuales en época medieval y moderna, Editorial Universitat Politécnica de Valencia, Valencia 2014, p. 147. |

| 25 | Zaragozá Catalán, Arturo y Ibáñez Fernández, Javier, “Materiales, técnicas y significados en torno a la arquitectura de la Corona de Aragón en tiempos del Compromiso de Caspe (1410-1412)”, Artigrama, nº 26, 2011, p. 22. |

| 26 | This interest is sufficiently documented, with specific examples, in royal chronicles. For example, when the first brick vaults were built in the Royal Palace of Valencia (1382), King Pedro IV the Ceremonious asked the merino of Zaragoza to send Master Faraig Delbadar and another of his best to Valencia to learn the new technique. He explained that a new type of construction method based on brick and plaster had been developed in Valencia. In 1407, the royal chapel of Martin the Humane in Barcelona Cathedral was already being vaulted in this same way. |

| 27 | [1] Navarro Camallonga, Pablo. Tesis: Arcos, bóvedas de arista y bóvedas aristadas de cantería en el círculo de Francesc Baldomar y Pere Compte. Directores Ignacio Bosch Reig y Luis Bosch Roig. Escuela Técnica Superior de Arquitectura de Valencia (UPV), 2018, p. 79. |

| 28 | [1] Serra Desfilis, Amadeo, “Al servicio de la ciudad: Joan del Poyo y la práctica de la arquitectura en Valencia (1402-1439)”. Ars longa: cuadernos de arte, Nº. 5, 1994, pp. 111-119. |

| 29 | [1] López Lorente, Víctor Daniel, “Mestres d’obra, Mestres de cases e imaginaires: la semántica de la construcción a finales de la edad Media en el contexto lingüístico catalán, Medievalismo, 30, 2020, pp. 331-352. |

| 30 | Palacios Gonzalo, José Carlos, La geometría de la bóveda de crucería española del XVI. Conferencia leída en el III Seminario de bóvedas, impartido dentro del máster de restauración de la Universidad Politécnica de Valencia, Gothicmed.com. A virtual museum of mediterranean gothic arquitecture, Archivo Digital UPM, 2007, pp. s. n. Acceso en línea: https://oa.upm.es/30744/

|

| 31 | A good example of this is the ribbed vaults that cover the church of the College of Corpus Christi in Valencia or College of the Patriarch Saint John of Ribera, which were built between 1586 and 1606. |

| 32 | Marín Sánchez, Rafael, “Bóvedas de crucería con nervios prefabricados de yeso y de ladrillo aplantillado”. En S. Huerta, I. Gil Crespo, S. García, M. Taín (eds.). Actas del Séptimo Congreso Nacional de Historia de la Construcción, Santiago 26-29 octubre 2011, Madrid: Instituto Juan de Herrera, 2011, p. 843. |

| 33 | Navarro Camallonga, Pablo, “Transverse Arches in Spanish Ribless Vaults”, Nexus Network Journal Architecture and Mathematics, 22, (4), p. 1. |

| 34 | Barrón García, Aurelio A., “bóvedas con figuras de estrellas y combados del |

| 35 | Tardogótico en la Rioja”. TVRIASO XXI, p. 225. |

| 36 | Zaragozá Catalán, Arturo "Una Catedral, una escuela. La arquitectura y la escultura valenciana del cuatrocientos a través de los maestros Dalmau, Baldomar y Compte". En Manuel Muñoz Ibáñez (coord.) La catedral de Valencia: historia, cultura y patrimonio 2018, p. 42.

|

| 37 | Martín Lloris, Catalina, “El monasterio de Santa María de la Valldigna: símbolo en la organización territorial del Antiguo Reino de Valencia”, Revista valenciana d'estudis autonòmics, nº 58 · Vol. I, 2013, p. 83. |

| 38 | Zaragozá Catalán, Arturo, “Cuando la arista gobierna el aparejo: Bóvedas aristadas”. En Amadeo Serra Desfilis (coord.) Arquitectura en construcción en Europa en época medieval y moderna, Universidad de Valencia 2010, p. 186. |

| 39 | Finalmente Alfonso V fue enterrado en el Monasterio de Poblet (Tarragona) |

| 40 | Chiva Maroto, German Andreu. Tesis doctoral Francesc Baldomar. Maestro de obra de la Seo. geometría e inspiración bíblica. Departamento de Composición Arquitectónica, UPV, Valencia 2014. |

| 41 | Navarro Camallonga, Pablo, “Transverse Arches in Spanish Ribless Vaults”, Nexus Network Journal Architecture and Mathematics, 22, (4), pp. 1-22. DOI 10.1007/s00004-020-00524-x.; “Las bóvedas nervadas de Baldomar. Singularidad y representación del poder en tiempos de Alfonso el Magnánimo”, Universidad Politécnica de Valencia, pp. 101-116. / Soler Estrela et al.: Soler Estrela, Alba; Garfella Rubio, José Teodoro y Cabeza González, Manuel. “Geometría y construcción en la capilla real del convento de santo Domingo. valencia”. En Francisco Hidalgo Delgado (coord..). XI Congreso Internacional de Expresión Gráfica aplicada a la Edificación. Universidad Politécnica de Valencia. Valencia, 2012, pp. 527-534/ Zaragozá Catalán, Arturo: Zaragozá Catalán, Arturo, “Cuando la arista gobierna el aparejo: Bóvedas aristadas”. En Amadeo Serra Desfilis (coord.) Arquitectura en construcción en Europa en época medieval y moderna, Universidad de Valencia 2010, pp. 187-224.; “Bóvedas del gótico mediterráneo”. En Eduardo Mira y Arturo Zaragozá Catalán (eds.). Una arquitectura del gótico mediterráneo. Catálogo de la exposición. Generalitat Valenciana. Conselleria de Cultura i Educació. Subsecretaria de Promoció Cultural. Valencia, 2003. · 2 volúmenes: 1º volumen, pp. 129-142. / Sánchez Simón, Ignacio, “Traza y montea de la bóveda de la Capilla Real del convento de Santo Domingo de Valencia. La arista del Triángulo de Reuleaux entre las aristas de la bóveda”. En S. Huerta, I. Gil Crespo, S. García, M. Taín (eds.). Actas del Séptimo Congreso Nacional de Historia de la Construcción, Santiago 26-29 octubre 2011. Madrid, Instituto Juan de Herrera, 2011, pp. 1302-1309., etc. |

| 42 | Natividad Vivó, Pau; Calvo López, José y Muñoz Cosme, Gaspar. “La bóveda de crucería anervada del portal de Quart de Valencia”. EGA Expresión Gráfica Arquitectónica nº 19 (2012), Pp. 190-199 |

| 43 | Zaragozá Catalán, Arturo y Marín Sánchez, Rafael, “El monasterio de San Jerónimo de Cotalba (Valencia). Un laboratorio de técnicas de albañilería (ss. XIV-XVI)”. En Santiago Huertas y Paula Fuentes (coords.). Actas del Noveno Congreso Nacional y Primer Congreso Internacional Hispanoamericano de Historia de la Construcción: Segovia, 13 a 17 de octubre de 2015, Vol. 3, 2015, p. 1799. |

| 44 | Navarro Camallonga, Pablo. Tesis: Arcos, bóvedas de arista y bóvedas aristadas de cantería en el círculo de Francesc Baldomar y Pere Compte. Directores Ignacio Bosch Reig y Luis Bosch Roig. Escuela Técnica Superior de Arquitectura de Valencia (UPV), 2018, p. 100. |

| 45 | Shelby, Lon R, 1977. Gothic Design techniques: The 15th Century Design Booklets of Mathes Roriczer and Hans Schumttermayer, Carbondale and Edwardsville: Southern Illinois University Press. / |

| 46 | Shelby, Lon R and Mark, R, 1979. Late Gothic Structural Design in the 'Instructions' of Lorenz Lechler." Architectura, 9, pp. 1 13-131. / Coenen, U, 1990. Die spãtgotischen Werkmeisterbücher in Deutschland. Untersuchung und Edition der Lehrschriften fiir Entwurfund Ausfiihrung von Sakralbauten. (Beitrüge zur Kunstwissenschaft, Bd. 25), München: Scaneg. / Müller, Werner, 1990. Grundlagen gotischer Bautechnik, München: Deutscher Kunstverlag. / Binding, G, 1993. Baubetrieb im Mittelalter, Darmstadt: Wissenshaftliche Gesellschaft. |

| 47 | Fitchen, J, 1981 (first. ed. 1961). The construction of Gothic Cathedrals: A Study of Medieval Vault Erection, Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. |

| 48 | Huerta, Santiago and Ruiz, Antonio. “Some Notes on Gothic Building Processes: The Expertises of Segovia Cathedral”. In M. Dunkeld, J. Campbell, Hentie Louw, M. Tutton, B. Addis, R. Thorne (eds.). The Second International Congress on Construction History (2006), London, p. 1619. |

| 49 | Zaragozá Catalán, Arturo, Arquitectura gótica valenciana siglos XIII-XV. Monumentos de la Comunidad Valenciana. Catálogo de monumentos y conjuntos declarados e incoados, Tomo I, Generalitat valenciana, Valencia, 2000. |

| 50 | Huerta, Santiago and Ruiz, Antonio. “Some Notes on Gothic Building Processes: The Expertises of Segovia Cathedral”. In M. Dunkeld, J. Campbell, Hentie Louw, M. Tutton, B. Addis, R. Thorne (eds.). The Second International Congress on Construction History (2006), London, pp. 1619-1631.

|

| 51 | Navarro Camallonga, Pablo. Tesis doctoral, Arcos, Bóvedas de Arista y Bóvedas Aristadas de Cantería en el Círculo de Francesc Baldomar y Pere Compte. Departamento de expresión gráfica, UPV, Valencia, 2018. |

| 52 | Navarro Camallonga, Pablo. Bóvedas aristadas. Levantamiento y estudio histórico-constructivo. Editorial Universidad de Alcalá, 2021. |

| 53 | Navarro Camallonga, Pablo. Tesis: Arcos, bóvedas de arista y bóvedas aristadas de cantería en el círculo de Francesc Baldomar y Pere Compte. Directores Ignacio Bosch Reig y Luis Bosch Roig. Escuela Técnica Superior de Arquitectura de Valencia (UPV), 2018, p. 178. |

| 54 | Huerta Fernández, Santiago, “Las bóvedas tabicadas en Alemania: la larga migración de una técnica constructiva”. Actas del Segundo Congreso Internacional Hispanoamericano, Noveno Nacional, de Historia de la Construcción, Vol. 2, Instituto Juan de Herrera, Madrid, p. 762. |

| 55 | The new kingdom stretched from the northern part of the Valencian region to the present-day region of Murcia, with some territories in the province of Teruel. This new Almoravid kingdom reached its peak under the reign of Ibn Mardanis, known to the Christians as the "Rey Lobo". |

| 56 | The rapid setting of plaster requires a fast pace of execution, because if it is not used immediately, the plaster begins to set and loses its plasticity. |

| 57 | Marín Sánchez, Rafael, “Bóvedas de crucería con nervios prefabricados de yeso y de ladrillo aplantillado”. En S. Huerta, I. Gil Crespo, S. García, M. Taín (eds.). Actas del Séptimo Congreso Nacional de Historia de la Construcción, Santiago 26-29 octubre 2011, Madrid: Instituto Juan de Herrera, 2011, p. 845. |

| 58 | Ibáñez Fernández, Javier, “Técnica y ornato: aproximación al estudio de la bóveda tabicada en Aragón y su decoración a lo largo de los siglos XVI y XVII”, Artigrama, núm. 25, 2010, p. 368. |

| 59 | Gómez-Ferrer Lozano, Mercedes, “Las bóvedas tabicadas en la arquitectura valenciana durante los siglos XIV, XV y XVI”. En Eduard Mira y Arturo Zaragozá Catalán (com.), Una arquitectura gótica mediterránea Vol. II, Generalidad valenciana, Valencia, 2003, p. 135. |

| 60 | Marín Sánchez, Rafael, “Aspectos constructivos de las bóvedas levantinas de albañilería (S. XV-XVI) a la luz de las obras y los documentos”. En Mercedes Gómez-Ferrer y Yolanda Gil Saura (eds.). Ecos culturales, artísticos y arquitectónicos entre Valencia y el Mediterráneo en Época Moderna. Cuadernos Ars Longa nº 8, 2018, p. 68. |

| 61 | Zaragozá Catalán, Arturo, “Hacia una historia de las bóvedas tabicadas”. En Arturo Zaragozá Catalán, Rafael Soler y Rafael Marín (eds.), Construyendo bóvedas tabicadas. Actas del simposio internacional de bóvedas tabicadas, Valencia 26, 27 y 28 de mayo de 2011, Editorial UPV, Valencia, 2012, p.20. |

| 62 | Ibáñez Fernández, Javier, “De la crucería al cortado: importación, implantación y desarrollo de la bóveda tabicada en Aragón y su decoración a lo largo de los siglos XVI y XVII”. En Arturo Zaragozá, Rafael Soler y Rafael Marín (eds.). Construyendo bóveda tabicadas. Actas del Simposio Internacional sobre Bóvedas tabicadas, Valencia 26, 27 y 28 de mayo de 2011. Editorial Universidad Politécnica de Valencia, Valencia, 2012, p. 87. |

| 63 | Ibáñez Fernández, Javier, “De la crucería al cortado: importación, implantación y desarrollo de la bóveda tabicada en Aragón y su decoración a lo largo de los siglos XVI y XVII”. En Arturo Zaragozá, Rafael Soler y Rafael Marín (eds.). Construyendo bóveda tabicadas. Actas del Simposio Internacional sobre Bóvedas tabicadas, Valencia 26, 27 y 28 de mayo de 2011. Editorial Universidad Politécnica de Valencia, Valencia, 2012, p. 87. |

| 64 | Thunissen H. J. W., Bóvedas su construcción y empleo en la arquitectura, Instituto Juan de Herrera, Madrid, 2012, p. 169. |

| 65 | Like the middle Ebro valley in Aragon or in most of Valencian territory. |

| 66 | Marín Sánchez, Rafael, “Aspectos constructivos de las bóvedas levantinas de albañilería (S. XV-XVI) a la luz de las obras y los documentos”. En Mercedes Gómez-Ferrer y Yolanda Gil Saura (eds.). Ecos culturales, artísticos y arquitectónicos entre Valencia y el Mediterráneo en Época Moderna. Cuadernos Ars Longa nº 8, 2018, p. 81. |

| 67 | Zaragozá Catalán, Arturo y Ibáñez Fernández, Javier, “Materiales, técnicas y significados en torno a la arquitectura de la Corona de Aragón en tiempos del Compromiso de Caspe (1410-1412)”, Artigrama, nº 26, 2011, p. 54. |

| 68 | Marín Sánchez, Rafael, “Bóvedas de crucería con nervios prefabricados de yeso y de ladrillo aplantillado”. En S. Huerta, I. Gil Crespo, S. García, M. Taín (eds.). Actas del Séptimo Congreso Nacional de Historia de la Construcción, Santiago 26-29 octubre 2011, Madrid: Instituto Juan de Herrera, 2011, p. 841. |

| 69 | Zaragozá Catalán, Arturo, “Hacia una historia de las bóvedas tabicadas”. En Arturo Zaragozá Catalán, Rafael Soler y Rafael Marín (eds.), Construyendo bóvedas tabicadas. Actas del simposio internacional de bóvedas tabicadas, Valencia 26, 27 y 28 de mayo de 2011, Editorial UPV, Valencia, 2012, p.27. |

| 70 | Zaragozá Catalán, Arturo, Arquitectura gótica valenciana siglos XIII-XV. Monumentos de la Comunidad Valenciana. Catálogo de monumentos y conjuntos declarados e incoados, Tomo I, Generalitat valenciana, Valencia, 2000, p. 153. |

| 71 | Gómez-Ferrer, Mercedes y Zaragozá, Arturo, “Lenguajes, fábricas y oficios en la arquitectura valenciana del tránsito entre la Edad Media y la Edad Moderna. (1450-1550)”, Artigrama, nº 23, 2008, p. 173. |

| 72 | Corbalán–de Celis y Durán, Juan. “De obras públicas y maestros de obras en la Valencia del siglo XV e inicios del XVI. El entorno de la iglesia de San Bartolomé”. Boletín de la sociedad castellonense de cultura Tomo LXXXIII • Enero-Junio 2007 • Cuad. I-II, p. 116. |

| 73 | Serra Desfilis, Amadeo. “A través de la frontera: los maestros de Castilla y la arquitectura tardogótica en Valencia”. En Juan Carlos Navarro Fajardo (coord.). Bóvedas valencianas: arquitecturas ideales, reales y virtuales en época medieval y moderna, Universidad de Cantabria, 2014, p.15. |

| 74 | Miralles, in addition to indicating that he participated in "all" of the city's works, specifically mentions his work in the Seu and in the monasteries of Portaceli and San Jerónimo la Virgen María in la Murta, Trinidad de Santa Clara and Valdexpi. |

| 75 | Melcior Miralles, Crònica i dietari del capellà d’Alfons el Magnànim, edició a cura de Mateu Rodrigo Lizondo, Fonts Històriques Valencianes, 47, València Universitat de València, 2011. |

| 76 | Serra Desfilis, Amadeo. “A través de la frontera: los maestros de Castilla y la arquitectura tardogótica en Valencia”. En Juan Carlos Navarro Fajardo (coord.). Bóvedas valencianas: arquitecturas ideales, reales y virtuales en época medieval y moderna, Universidad de Cantabria, 2014, p.15. |

| 77 | According to José Manuel Barrera Puigdollers, financed by Beatriz Villaragut. Report p. 41 |

| 78 | Barrera Puigdollers, J. M., PLAN ESPECIAL ZONA NORTE DE ALFAUIR (PE); URBANÍSTICA Y PATRIMONIAL Plan Especial de Protección del Monumento- Monasterio de San Jerónimo de Cotalba (PEP). |

| 79 | Zaragozá Catalán, Arturo, “Hacia una historia de las bóvedas tabicadas”. En Arturo Zaragozá Catalán, Rafael Soler y Rafael Marín (eds.), Construyendo bóvedas tabicadas. Actas del simposio internacional de bóvedas tabicadas, Valencia 26, 27 y 28 de mayo de 2011, Editorial UPV, Valencia, 2012, p.34. |

| 80 | Gómez-Ferrer Lozano, Mercedes, “Las bóvedas tabicadas en la arquitectura valenciana durante los siglos XIV, XV y XVI”. En Eduard Mira y Arturo Zaragozá Catalán (com.), Una arquitectura gótica mediterránea Vol. II, Generalidad valenciana, Valencia, 2003, p. 145. |

| 81 | Corbalán–de Celis y Durán, Juan. “De obras públicas y maestros de obras en la Valencia del siglo XV e inicios del XVI. El entorno de la iglesia de San Bartolomé”. Boletín de la sociedad castellonense de cultura Tomo LXXXIII • Enero-Junio 2007 • Cuad. I-II, p. 109. |

| 82 | Corbalán–de Celis y Durán, Juan. “De obras públicas y maestros de obras en la Valencia del siglo XV e inicios del XVI. El entorno de la iglesia de San Bartolomé”. Boletín de la sociedad castellonense de cultura Tomo LXXXIII • Enero-Junio 2007 • Cuad. I-II, p. 116. |

| 83 | Serra Desfilis, Amadeo, “El fasto del palacio inacabado. la casa de la ciudad de valencia en los siglos XIV y XV”, Historia de la ciudad III: Arquitectura y transformación urbana de la ciudad de Valencia, COACV, 2004, p. 95. |

| 84 | Bertachi, Silvia, “Modelos de bóvedas en estrella: forma y geometría”. En Juan Carlos Navarro Fajardo (ed.), Bóvedas valencianas. Arquitecturas ideales, reales y virtuales en época medieval y moderna, Editorial Universitat Politécnica de Valencia, Valencia 2014, p. 140. |

References

- Barrera Puigdollers, J. M. , PLAN ESPECIAL ZONA NORTE DE ALFAUIR (PE); URBANÍSTICA Y PATRIMONIAL Plan Especial de Protección del Monumento- Monasterio de San Jerónimo de Cotalba (PEP).

- Barrón García, Aurelio A.

- Tardogótico en la Rioja”. TVRIASO.

- Bertachi, Silvia, “Modelos de bóvedas en estrella: forma y geometría”. En Juan Carlos Navarro Fajardo (ed.), Bóvedas valencianas. Arquitecturas ideales, reales y virtuales en época medieval y moderna, Editorial Universitat Politécnica de Valencia, Valencia 2014, pp. 137-162.

- Breymann, Gustav Adolf, Allgemeine Bau-Constructions-Lehre, mit Besonderer Beziehung auf das Hochbauwesen ein Leiftaden zu Vorlesungen und zum Selbstunterrichte. Constructionen in Metall Eisenconstrutionen ( 1858.

- Chiva Maroto, German Andreu. Tesis doctoral Francesc Baldomar. Maestro de obra de la Seo. geometría e inspiración bíblica. Departamento de Composición Arquitectónica, UPV, Valencia 2014.

- Chueca, Fernando. La catedral nueva de Salamanca. Historia documental de su construcción. Volumen del Acta Salmanticensia, Filosofía y Letras tomo IV, N.º 3, Salamanca, Universidad de Salamanca, 1951.

- Coenen, U, 1990. Die spãtgotischen Werkmeisterbücher in Deutschland. Untersuchung und Edition der Lehrschriften fiir Entwurfund Ausfiihrung von Sakralbauten, Beitrüge: zur Kunstwissenschaft, Bd. 25), München: Scaneg.

- Corbalán-de Celis y Durán, Juan. “De obras públicas y maestros de obras en la Valencia del siglo XV e inicios del XVI. El entorno de la iglesia de San Bartolomé́”. Boletín de la sociedad castellonense de cultura Tomo LXXXIII • Enero-Junio 2007, Cuad. I-II, pp. 105-122.

- Fitchen, J, 1981 (first. ed. 1961). The construction of Gothic Cathedrals: A Study of Medieval Vault Erection, Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

- Gómez-Ferrer Lozano, Mercedes, “Las bóvedas tabicadas en la arquitectura valenciana durante los siglos XIV, XV y XVI”. En Eduard Mira y Arturo Zaragozá Catalán (com.), Una arquitectura gótica mediterránea Vol. II, Generalidad valenciana, Valencia, 2003, pp. 135-155.

- Gómez-Ferrer, Mercedes y Zaragozá, Arturo, “Lenguajes, fábricas y oficios en la arquitectura valenciana del tránsito entre la Edad Media y la Edad Moderna. (1450-1550)”, Artigrama, nº 23, 2008, pp. 149-184.

- Huerta, Santiago and Ruiz, Antonio. “Some Notes on Gothic Building Processes: The Expertises of Segovia Cathedral”. In M. Dunkeld, J. Campbell, Hentie Louw, M. Tutton, B. Addis, R. Thorne (eds.). The Second International Congress on Construction History (2006), London, pp. 1619-1631, 1619.

- Huerta Fernández, Santiago, “Las bóvedas tabicadas en Alemania: la larga migración de una técnica constructiva”. Actas del Segundo Congreso Internacional Hispanoamericano, Noveno Nacional, de Historia de la Construcción, Vol. 2, Instituto Juan de Herrera, Madrid, 2017, pp. 759-772.

- Ibáñez Fernández, Javier, “Técnica y ornato: aproximación al estudio de la bóveda tabicada en Aragón y su decoración a lo largo de los siglos XVI y XVII”, Artigrama, núm. 25, 2010, pp. 363-405.

- Ibáñez Fernández, Javier, “De la crucería al cortado: importación, implantación y desarrollo de la bóveda tabicada en Aragón y su decoración a lo largo de los siglos XVI y XVII”. En Arturo Zaragozá, Rafael Soler y Rafael Marín (eds.). Construyendo bóveda tabicadas. Actas del Simposio Internacional sobre Bóvedas tabicadas, Valencia 26, 27 y 28 de mayo de 2011. 2012; Editorial Universidad Politécnica de Valencia, Valencia, 2012.

- López Lorente, Víctor Daniel, “Mestres d’obra, Mestres de cases e imaginaires: la semántica de la construcción a finales de la edad Media en el contexto lingüístico catalán, Medievalismo, 30, 2020, pp. 331-352.

- Marín Sánchez, Rafael, “Bóvedas de crucería con nervios prefabricados de yeso y de ladrillo aplantillado”. En S. Huerta, I. Gil Crespo, S. García, M. Taín (eds.). Actas del Séptimo Congreso Nacional de Historia de la Construcción, I: 26-29 octubre 2011, Madrid, 2011: Instituto Juan de Herrera, 2011, pp. 841-850.

- Marín Sánchez, Rafael, “Aspectos constructivos de las bóvedas levantinas de albañilería (S. XV-XVI) a la luz de las obras y los documentos”. En Mercedes Gómez-Ferrer y Yolanda Gil Saura (eds.). Ecos culturales, artísticos y arquitectónicos entre Valencia y el Mediterráneo en Época Moderna. Cuadernos Ars Longa; nº 8, 2018.

- Martín Lloris, Catalina, “El monasterio de Santa María de la Valldigna: símbolo en la organización territorial del Antiguo Reino de Valencia”, Revista valenciana d’estudis autonòmics, nº 58 · Vol. I, 2013, pp. 65-85.

- Martínez-Espejo Zaragoza, Isabel. “Técnicas de levantamiento con escáner láser del patrimonio arquitectónico. Hipótesis y restitución virtual de la bóveda de una iglesia”. En José Antonio Melgares Guerrero y Pedro Enrique Collado Espejo (dirs. congr.). XXII Jornadas de patrimonio cultural de la Región de Murcia: (4 de Octubre - 8 de Noviembre de 2011) Cartagena, Murcia, 2011, pp. 275-284.

- Melcior Miralles, Crònica i dietari del capellà d’Alfons el Magnànim, edició a cura de Mateu Rodrigo Lizondo, Fonts Històriques Valencianes, 47, València Universitat de València, 2011.

- Müller, Werner, 1990. Grundlagen gotischer Bautechnik, München: Deutscher Kunstverlag. / Binding, G, 1993. Baubetrieb im Mittelalter, Darmstadt: Wissenshaftliche Gesellschaft.

- Natividad Vivó, Pau; Calvo López, José y Muñoz Cosme, Gaspar. “La bóveda de crucería anervada del portal de Quart de Valencia”. EGA Expresión Gráfica Arquitectónica nº 19 (2012), Pp. 190-199.

- Navarro Fajardo, Juan Carlos, “La lonja de valencia a la luz de las trazas de.

- Montea”, ARCHÉ. publicación del instituto universitario de restauración del patrimonio de la UPV - Núms. 4 y 5 – 2010, pp. 245-253.

- Navarro Camallonga, Pablo. Tesis: Arcos, bóvedas de arista y bóvedas aristadas de cantería en el círculo de Francesc Baldomar y Pere Compte. Directores Ignacio Bosch Reig y Luis Bosch Roig. Escuela Técnica Superior de Arquitectura de Valencia (UPV), 2018.

- Navarro Camallonga, Pablo, “Transverse Arches in Spanish Ribless Vaults”, Nexus Network Journal Architecture and Mathematics, 22, (4), 2020, pp. 1-22. . https://doi.org/. [CrossRef]

- Navarro Camallonga, Pablo. Bóvedas aristadas. Levantamiento y estudio histórico-constructivo. Editorial Universidad de Alcalá, 2021.

- Navarro Camallonga, Pablo, “Las bóvedas nervadas de Baldomar. Singularidad y representación del poder en tiempos de Alfonso el Magnánimo”, Universidad Politécnica de Valencia, pp. 101-116.

- Palacios Gonzalo, José Carlos, “Las bóvedas de crucería españolas, ss. XV y XVI”. En A. Graciani, S. Huerta, E. Rabasa, M. Tabales (eds.). Actas del Tercer Congreso Nacional de Historia de la Construcción, Sevilla, 26-28 octubre 2000, eds., Madrid: I. Juan de Herrera, SEdHC, Universidad de Sevilla, Junta Andalucía, COAAT Granada, CEHOPU, 2000, pp. 743-750.

- Palacios Gonzalo, José Carlos, La geometría de la bóveda de crucería española del XVI. Conferencia leída en el III Seminario de bóvedas, impartido dentro del máster de restauración de la Universidad Politécnica de Valencia, Gothicmed.com. A virtual museum of mediterranean gothic arquitecture, Archivo Digital UPM, 2007, pp. s. n. Acceso en línea: https://oa.upm.es/ 30744/. 3074.

- Pecoraro, Ilaria, “Las bóvedas estrelladas del Salento. Una arquitectura a caballo entre la edad media y la edad moderna”. En Eduard Mira y Arturo Zaragozá Catalán (com.), Una arquitectura gótica mediterránea Vol. II, Generalidad valenciana, Valencia, 2003, pp. 53-66.

- Redondo Martínez, Esther. Tesis: La Bóveda Tabicada en España en el Siglo XIX. La Transformación de un Sistema Constructivo. Dirigida por Santiago Huerta Fernández, Escuela Técnica Superior de Arquitectura de Madrid, Madrid, 2013.

- Sánchez Simón, Ignacio, “Traza y montea de la bóveda de la Capilla Real del convento de Santo Domingo de Valencia. La arista del Triángulo de Reuleaux entre las aristas de la bóveda”. En S. Huerta, I. Gil Crespo, S. García, M. Taín (eds.). Actas del Séptimo Congreso Nacional de Historia de la Construcción, Santiago 26-29 octubre 2011. Madrid, Instituto Juan de Herrera, 2011, pp. 1302-1309.

- Serra Desfilis, Amadeo, “Al servicio de la ciudad: Joan del Poyo y la práctica de la arquitectura en Valencia (1402-1439)”. Ars longa: cuadernos de arte, Nº. 5, 1994, pp. 111-119.

- Serra Desfilis, Amadeo, “El fasto del palacio inacabado. la casa de la ciudad de valencia en los siglos XIV y XV”, Historia de la ciudad III: Arquitectura y transformación urbana de la ciudad de Valencia, COACV, 2004, pp. 73-99.

- Serra Desfilis, Amadeo. “A través de la frontera: los maestros de Castilla y la arquitectura tardogótica en Valencia”. En Juan Carlos Navarro Fajardo (coord.). Bóvedas valencianas: arquitecturas ideales, reales y virtuales en época medieval y moderna, Universidad de Cantabria, 2014, pp. 10-33.

- Shelby, Lon R, 1977. Gothic Design techniques: The 15th Century Design Booklets of Mathes Roriczer and Hans Schumttermayer, Carbondale and Edwardsville: Southern Illinois University Press.

- Shelby, Lon R and Mark, R, 1979. Late Gothic Structural Design in the ‘Instructions’ of Lorenz Lechler.” Architectura, 9, pp. 1 13-131.

- Soler Estrela, Alba; Garfella Rubio, José Teodoro y Cabeza González, Manuel.

- “Geometría y construcción en la capilla real del convento de santo Domingo. valencia”. En Francisco Hidalgo Delgado (coord..). XI Congreso Internacional de Expresión Gráfica aplicada a la Edificación. Universidad Politécnica de Valencia. Valencia, 2012.

- Tellia, Fabio y Palacios, José Carlos, “Las bóvedas de crucería del manuscrito Llibre de trasas de viax y muntea, de Joseph Ribes”, LOCVS AMOENVS 13, 2015, pp. 29 -41.

- Thunissen H. J., W. , Bóvedas su construcción y empleo en la arquitectura, Instituto Juan de Herrera, Madrid, 2012.

- Varagnoli, Claudio; Serafini, Lucia; Pezzi, Aldo y Zullo, Enza, “Arte y cultura de la construcción histórica del Abruzzo 2: las estructuras horizontales”. En M. Arenillas, C. Segura, F. Bueno y S. Huerta (eds.). Actas del Quinto Congreso Nacional de Historia de la Construcción, Burgos: 7-9 junio 2007, Madrid: I. Juan de Herrera, SEdHC, CICCP, CEHOPU, 2007, pp. 925-934.

- Zaragozá Catalán, Arturo, Arquitectura gótica valenciana siglos XIII-XV. Monumentos de la Comunidad Valenciana. Catálogo de monumentos y conjuntos declarados e incoados, Tomo I, Generalitat valenciana, Valencia, 2000.

- Zaragozá Catalán, Arturo, “Historia de las bóvedas tabicadas”. En Eduard Mira y Arturo Zaragozá Catalán (com.), Una arquitectura gótica mediterránea Vol. I, Generalidad valenciana, Valencia, 2003, pp. 129-140.

- Zaragoza, Catalán, Arturo. “Bóvedas del gótico mediterráneo”. En Eduardo Mira y Arturo Zaragozá Catalán (eds.). Una arquitectura del gótico mediterráneo, Catálogo: de la exposición. Generalitat Valenciana. Conselleria de Cultura i Educació. Subsecretaria de Promoció Cultural. Valencia, 2003. · 2 volúmenes, : 1º volumen, pp. 129-142.

- Zaragozá Catalán, Arturo, “Cuando la arista gobierna el aparejo: Bóvedas aristadas”. En Amadeo Serra Desfilis (coord.) Arquitectura en construcción en Europa en época medieval y moderna, Universidad de Valencia 2010, pp. 187-224.

- Zaragozá Catalán, Arturo y Ibáñez Fernández, Javier, “Materiales, técnicas y significados en torno a la arquitectura de la Corona de Aragón en tiempos del Compromiso de Caspe (1410-1412)”, Artigrama, nº 26, 2011, pp. 21-102.

- Zaragozá Catalán, Arturo, “Hacia una historia de las bóvedas tabicadas”. En Arturo Zaragozá Catalán, Rafael Soler y Rafael Marín (eds.), Construyendo bóvedas tabicadas. Actas del simposio internacional de bóvedas tabicadas, Valencia 26, 27 y 28 de mayo de 2011, Editorial UPV, Valencia, 2012, pp. 11-46.

- Zaragozá Catalán, Arturo y Marín Sánchez, Rafael, “El monasterio de San Jerónimo de Cotalba (Valencia). Un laboratorio de técnicas de albañilería (ss. XIV-XVI)”. En Santiago Huertas y Paula Fuentes (coords.). Actas del Noveno Congreso Nacional y Primer Congreso Internacional Hispanoamericano de Historia de la Construcción: Segovia, 13 a 17 de octubre de 2015, Vol. 3, 2015, pp. 1793-1802.

- Zaragozá Catalán, Arturo “Una Catedral, una escuela. La arquitectura y la escultura valenciana del cuatrocientos a través de los maestros Dalmau, Baldomar y Compte”. En Manuel Muñoz Ibáñez (coord.) La catedral de Valencia: historia, cultura y patrimonio 2018, pp. 13-60.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).