Introduction

Midfacial fractures constitute a substantial portion of maxillofacial trauma and are traditionally linked to high-energy mechanisms such as interpersonal violence and road traffic accidents [

4,

12,

15,

16]. However, the increasing proportion of elderly individuals in the global population has led to a notable shift in the etiology and presentation of such injuries. In this demographic, low-energy trauma—particularly ground-level falls—has become the predominant cause [

2,

6,

7].

Elderly patients present unique anatomical and physiological challenges in the context of facial trauma. Age-related osteopenia and osteoporosis, in conjunction with edentulism and diminished facial structural support, significantly increase the risk of fracture from relatively minor impacts [

3,

11,

13]. These changes not only alter fracture patterns but also influence management strategies [

1,

5,

8,

9]. In many cases, conservative treatment is favored due to limited physiological reserves, comorbidities, and reduced functional and aesthetic expectations among older patients [

6,

10,

21,

22].

In addition to skeletal fragility, edentulism represents a key anatomical and functional risk factor in elderly patients sustaining midfacial trauma [

3,

13]. Tooth loss compromises the vertical dimension of occlusion and significantly alters maxillary and mandibular support, reducing the capacity of the masticatory system to absorb external forces. Consequently, even minor low-energy impacts may translate into direct transmission of force to the midfacial bones, increasing the likelihood of fracture.

Few studies have comprehensively addressed the intersection of age, gender, and injury mechanism in midfacial trauma, particularly in Central and Eastern European populations [

12,

18]. Understanding these variables is critical for optimizing preventive strategies and tailoring therapeutic protocols to meet the specific needs of elderly patients [

14,

20].

The present study aims to retrospectively analyze a 10-year cohort of patients with midfacial fractures in Hungary, at the University of Pécs, Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. Emphasis is placed on identifying age- and gender-specific trends, with particular emphasis on the role of low-energy trauma and its implications for diagnosis, treatment planning, and resource allocation in geriatric care.

Materials and Methods

This retrospective cohort study was conducted at the Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, University of Pécs, Hungary and included patients diagnosed with midfacial fractures between January 2013 and December 2022. Patient data were retrieved from institutional electronic health records using ICD-10 diagnostic codes corresponding to midfacial fractures. Patients were included if they had radiologically (with CT) confirmed fractures involving the midfacial region (e.g., zygomatic complex, maxilla, frontal bone, orbital wall), and when complete clinical documentation was available. Patients were excluded with incomplete medical records, and when fractures were limited to the mandible or nasal bone without midfacial involvement.

Patient data were retrospectively extracted from electronic medical records. All data were fully anonymized in accordance with the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) prior to analysis. Study variables included demographic characteristics (age, gender), etiology of the injury (fall, traffic accident, assault, sport, other), fracture localization (i.e. the anatomical site of fracture), the hospitalization status (admitted to our maxillofacial institution, treated in external departments, or managed only on an outpatient basis). Analyzed variables included furthermore the presence and location of associated injuries (e.g., head, upper/lower limb, trunk, orbital/nasal region) and the dental status of the elderly patient group. The dentition status was categorized as i) patients with minor tooth loss and/or fixed dental prostheses (less than 3 teeth missing); ii) patients with major tooth loss (more than 3 but less than 10 teeth missing); iii) edentulous or partially edentulous patients with removable prostheses, and finally iv) completely edentulous patients without any prosthetic rehabilitation.

Patients then were stratified into two age groups: <65 years and ≥65 years, based on the World Health Organization (WHO) definition of elderly populations.

Ethical Approval

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Pécs (reference number: KK63973-1/2024). Due to the retrospective nature of the study, the requirement for informed consent was waived.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize patient demographics and clinical characteristics. Categorical variables were analyzed with Pearson’s chi-square test, or Fisher’s exact test where appropriate (i.e., when expected cell counts were below 5). MedCalc was used to compute univariate odds ratios [

23]. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics, version 28.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

Patient Demographics

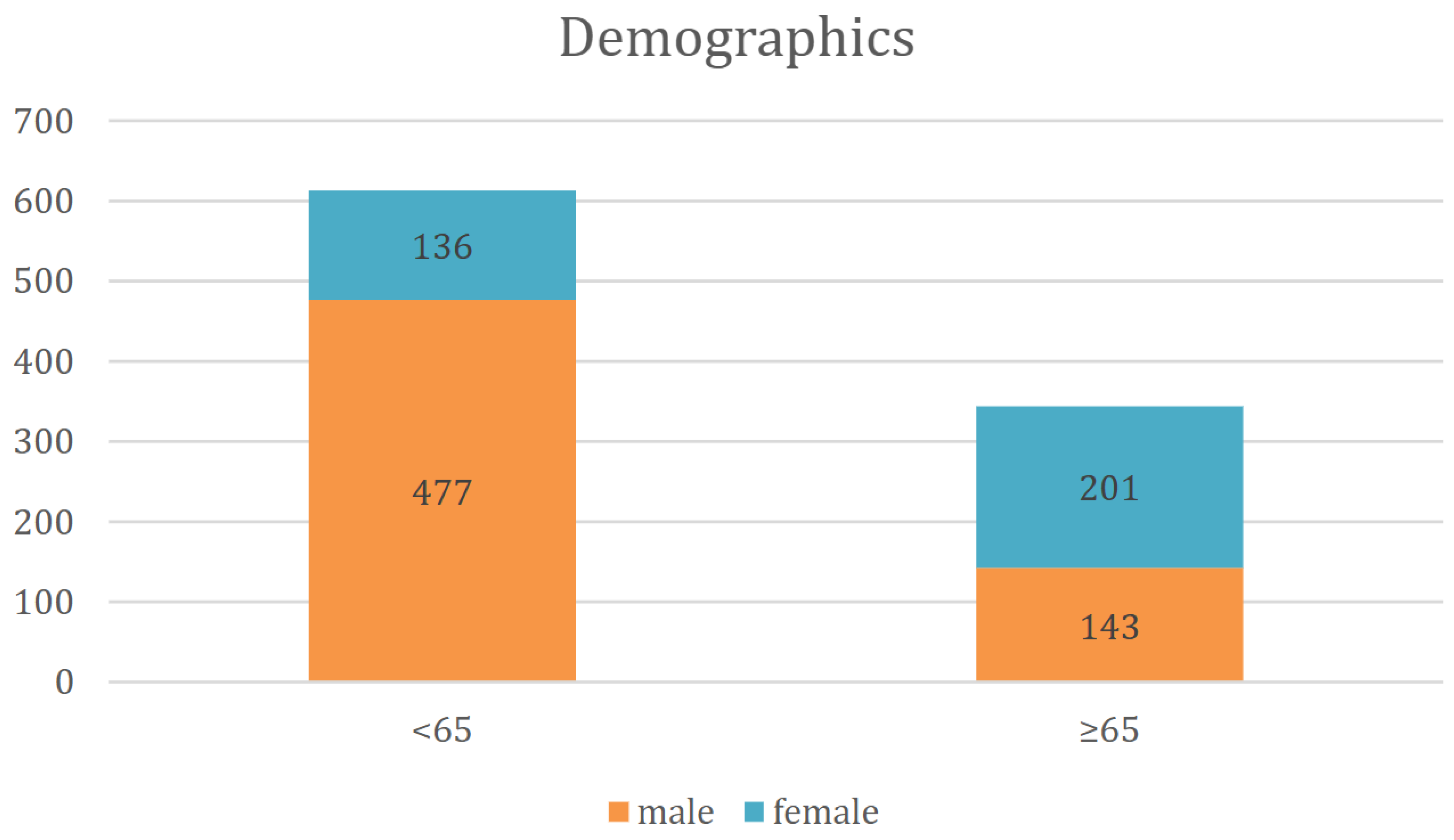

A total of 957 patients with CT-confirmed midfacial fractures were included in the study. Of these, 620 were male and 337 female. Among patients under the age of 65 (n = 613), the majority were male (n=477), while females constituted the majority (n=201) in the elderly group (≥65 years; n = 344) (

Figure 1). The mean age of the study population was 50.73 years (SD ± 24,82). Male patients had a mean age of 48,66 years (SD ± 20.69), whereas female patients were significantly older, with a mean age of 66,1 years (SD ± 19,1). Stratified by age, the <65-year subgroup had a mean age of 39,7 years (SD ± 14,0), while the ≥65-year group had a mean age of 77.41 years (SD ± 7.6).

Dental status in the elderly population

In the ≥65-year-old patient group (n=344), the dental status of patients was as follows. 28 patients had minor tooth loss and/or fixed dental prostheses (8.1%). 114 patients had major tooth loss (33.1%). 92 patients were edentulous or partially edentulous but had removable prostheses (26.7%), and 110 patients were completely edentulous without any prosthetic rehabilitation (32.0%). Midfacial fracture showed a ~16 times higher occurrence (OR: 16.05, 95%CI: 10.32-24.98, p<0.001) in patients with total or subtotal tooth loss than in patients having only minor (<3 teeth missing) tooth loss.

Etiology of Midfacial Fractures

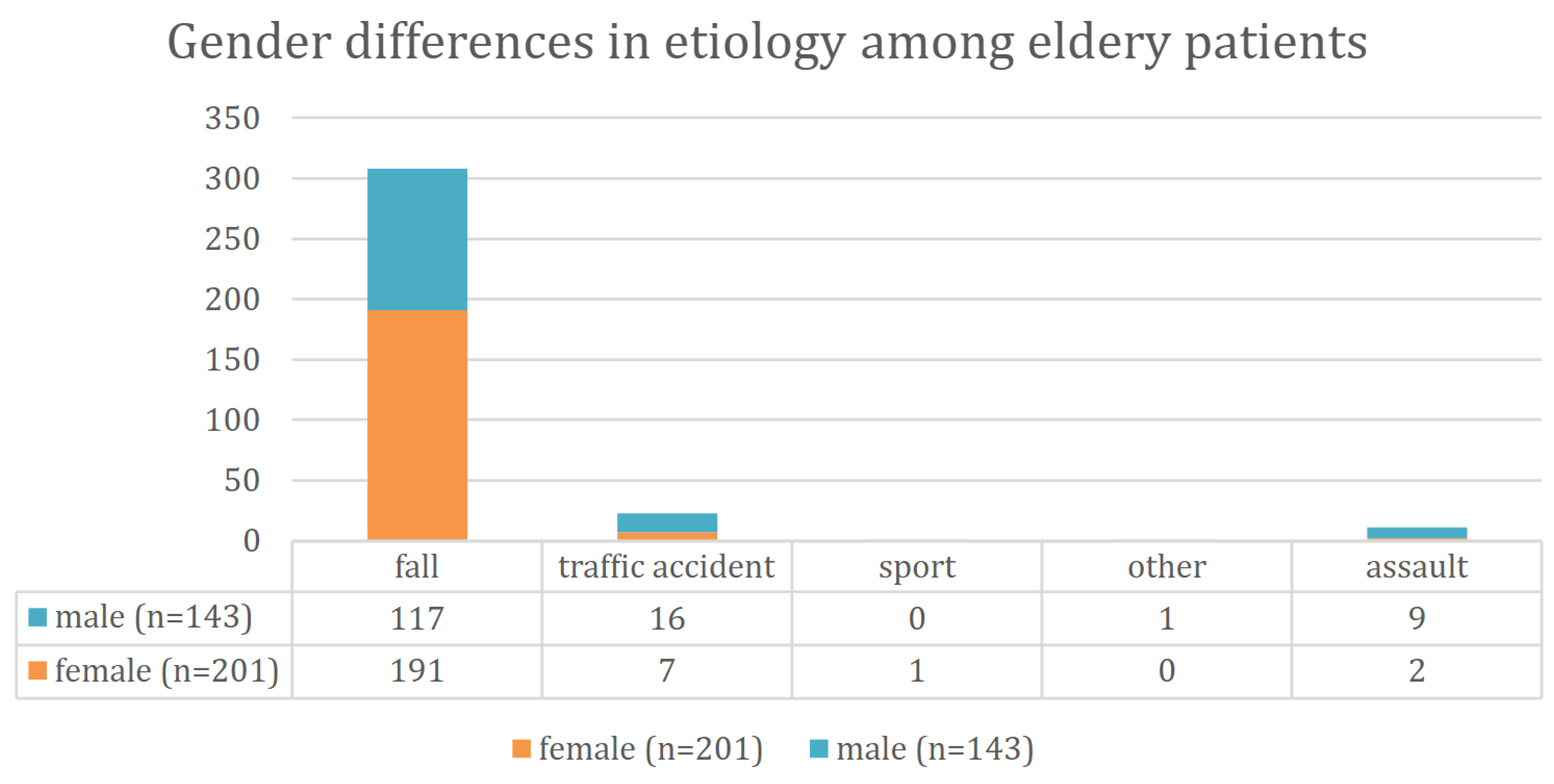

Falls were the most common cause of injury among elderly patients (≥65 years), accounting for 89.5% of cases, in contrast to 37.1% in the younger group (<65 years). In the <65 cohort, assaults (32.2%) and traffic accidents (22.1%) i.e. non-fall causes were the predominant when considering the etiology (

Table 1). The chi-square test confirmed that this age-related difference in trauma mechanisms was statistically significant (p < 0.001).

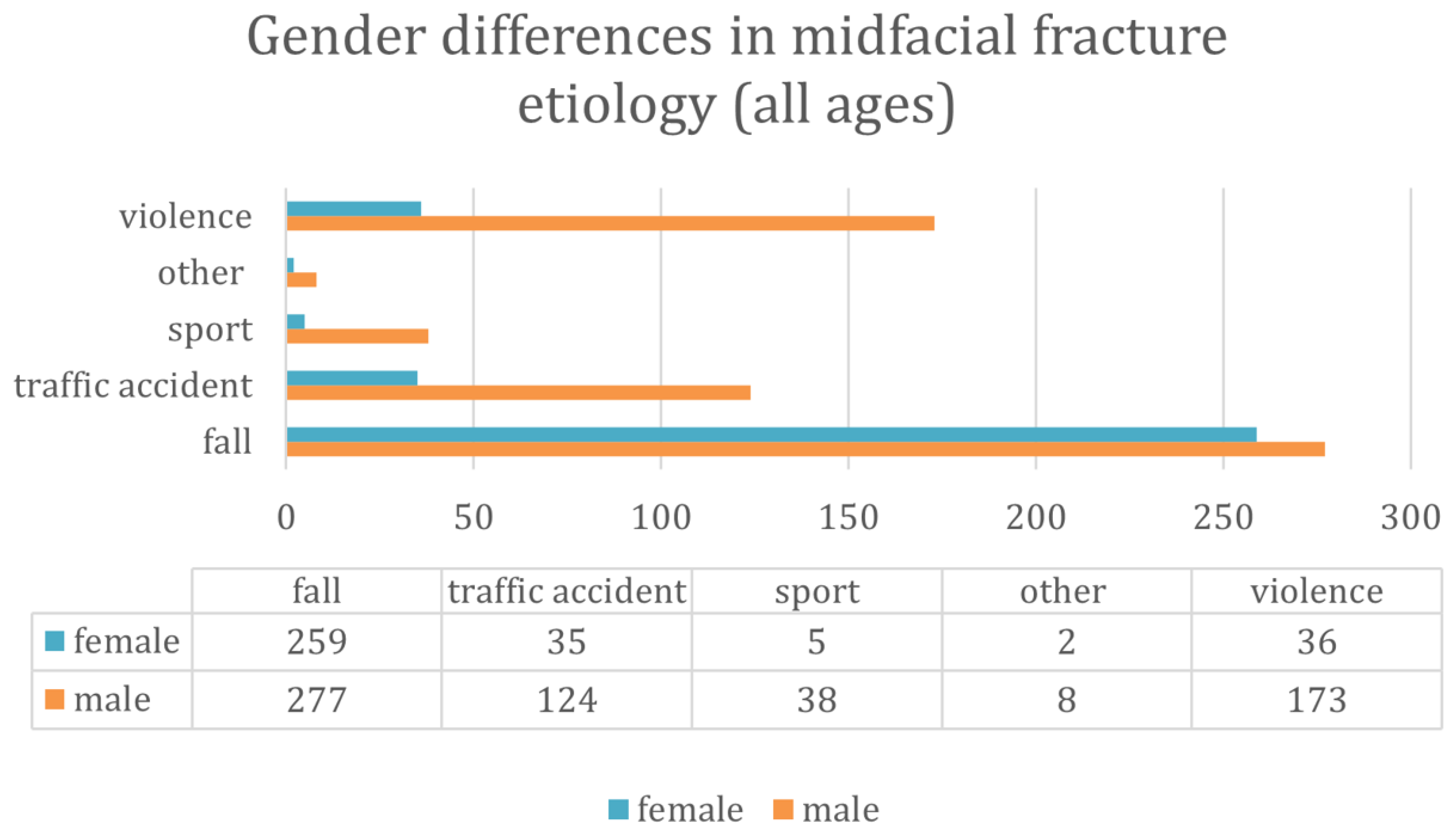

Gender-Specific Injury Patterns

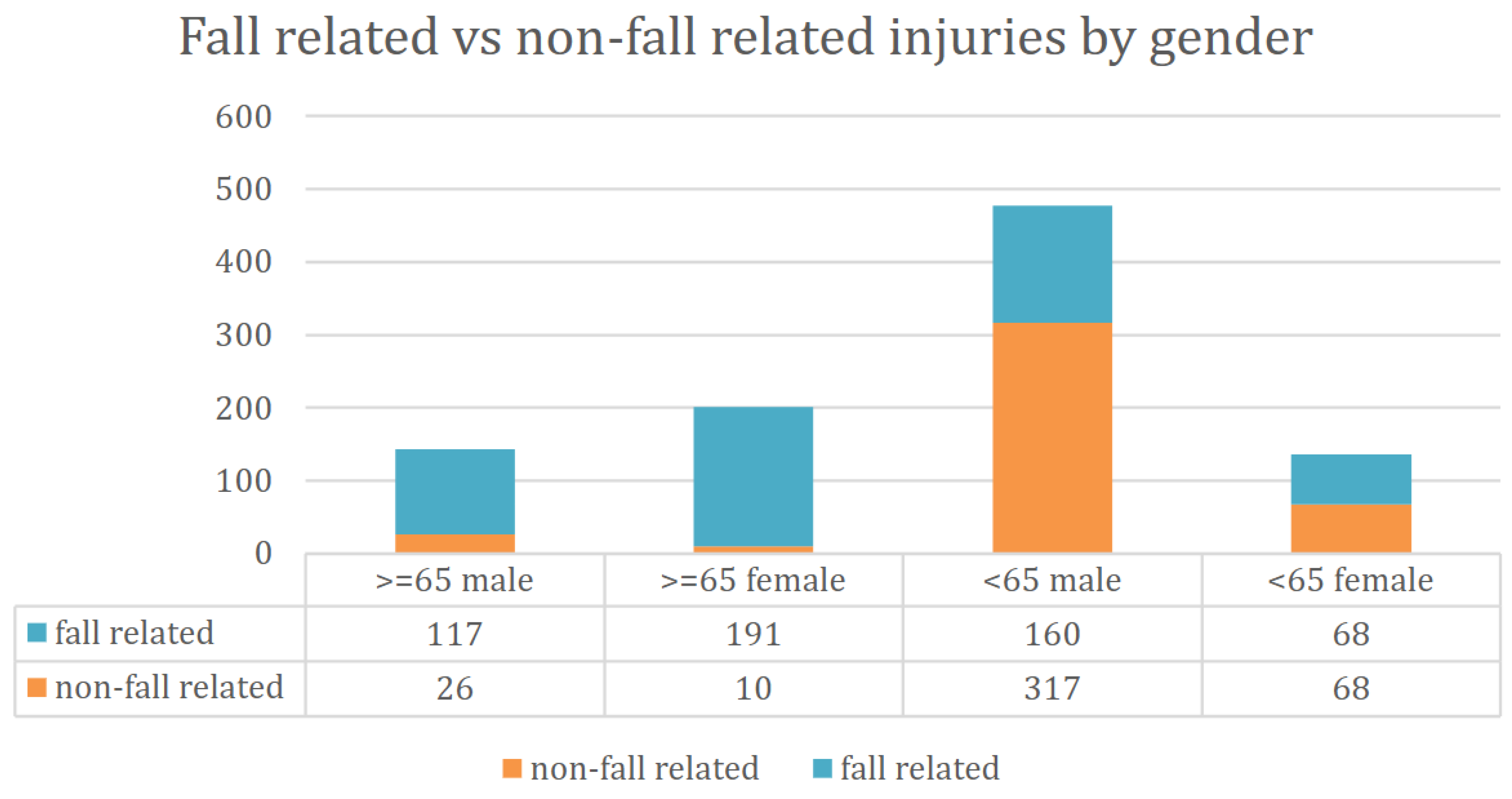

Across all age groups, fall-related fractures were significantly more frequent in females (76.9%) than in males (44.7%). In the elderly subgroup, 95.0% of fractures in females and 81.8% in males resulted from falls (

Figure 2). Falls were more common in individuals aged 65 and older (89.5%) compared to those under 65 (37.1%) (

Figure 3). Conversely, traffic accidents (6.7% vs. 22.2%), sports-related injuries (0.3% vs. 6.9%), and assault-related injuries (3.2% vs. 32.3%) were more frequent in the younger age group (

Figure 4). The association between gender, age and fall-related etiology was statistically significant (p < 0.001).

Age- and sex-stratified analysis revealed significant differences in fall-related midfacial fracture risk. Elderly men (≥65 years) had nearly 10-fold higher chance for such injuries compared to younger men (OR = 9.92, 95% CI: 5.60–14.20,

p < 0.001). This age-related increase was even more pronounced in women, where elderly females had a 19-fold higher risk compared to younger females (OR = 19.1, 95% CI: 9.30–39.21,

p < 0.001) (

Table 2).

In terms of gender differences, elderly females had more than four times higher chance to a fall-related fracture than their male counterparts (OR = 4.24, 95% CI: 1.98–9.12,

p = 0.001). Among younger patients, females also showed a nearly twofold increased risk compared to younger males (OR = 1.98, 95% CI: 1.35–2.92,

p<0.001) (

Table 2). These findings emphasize that female sex and advanced age act synergistically, placing elderly women at the highest overall risk for fall-related midfacial fractures.

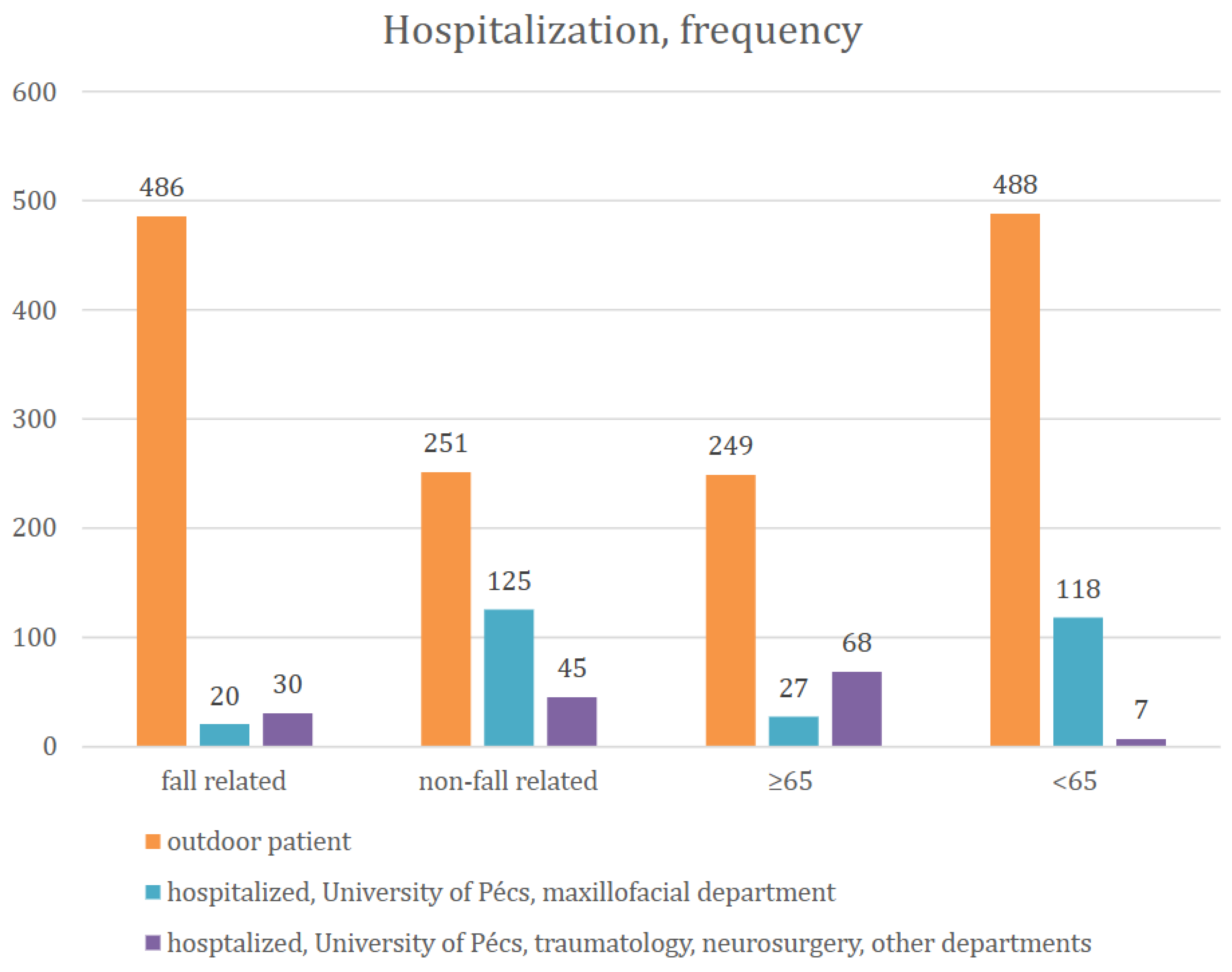

Hospitalization Patterns

Patients with fall-related injuries were much more likely to be treated as outpatients, while non-fall-related injuries were more often managed in a hospital setting (

Figure 5). Outpatient cases were ~6.6 times more likely to present fall-related injuries compared to hospitalized patients (

Table 3, Figure 5). In the younger patient group (<65yrs) one from five patients, while in the elderly group (≥65yrs) one from ten patients was on average hospitalized in our maxillofacial department (p < 0.001) (

Table 3). When considering, however, all kinds of hospitalizations (including other departments), 27.6% of elderly (≥65yrs) and 20.4% of younger patients (<65yrs) were treated as inpatients. Overall, elderly were ~1.5 times more likely to be treated as inpatients, however significantly less frequently in the maxillofacial department.

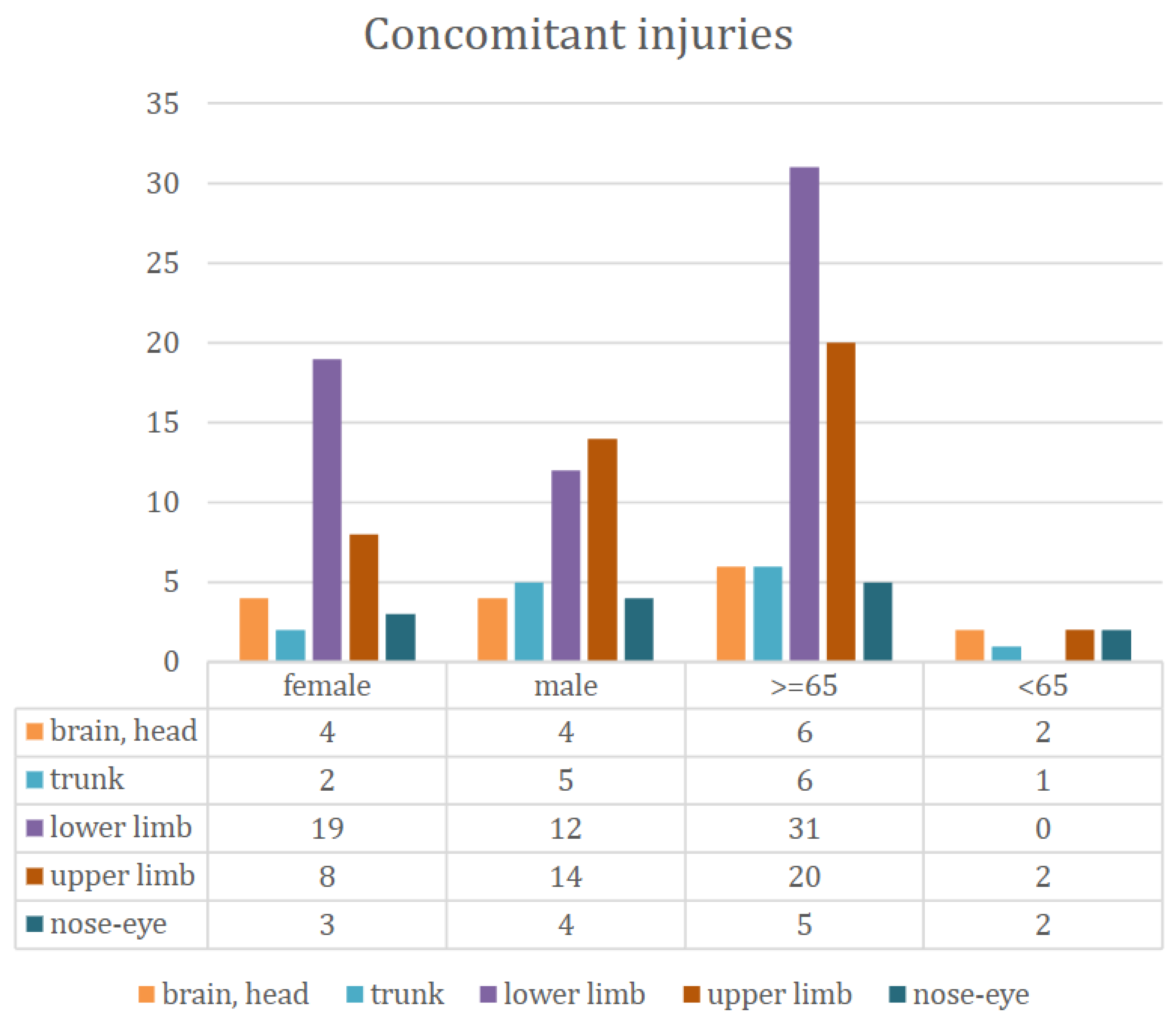

Associated Injuries

Among 957 patients, detailed data on the localization of concomitant injuries were available for 75 individuals. Notably, all 75 cases with documented concomitant injuries were hospitalized in external departments of the University of Pécs, primarily in traumatology, otorhinolaryngology, or neurosurgery units (

Figure 6). These records allowed for subgroup analyses based on both sex and age. Injury patterns differed notably by both sex and age groups. Elderly patients (≥65 years) most frequently sustained lower limb injuries (n=31), which were almost exclusively absent in the younger group (<65 years). Upper limb injuries were also more common among the elderly (n=20 vs. n=2), while head/brain and trunk injuries were relatively evenly distributed. Females experienced more lower limb injuries (n=19) than males (n=12), whereas males showed slightly higher number of upper limb and trunk trauma.

We recorded only the most severe injury in polytraumatized patients; therefore, for example, we do not see associated lower limb injuries in the younger age group.

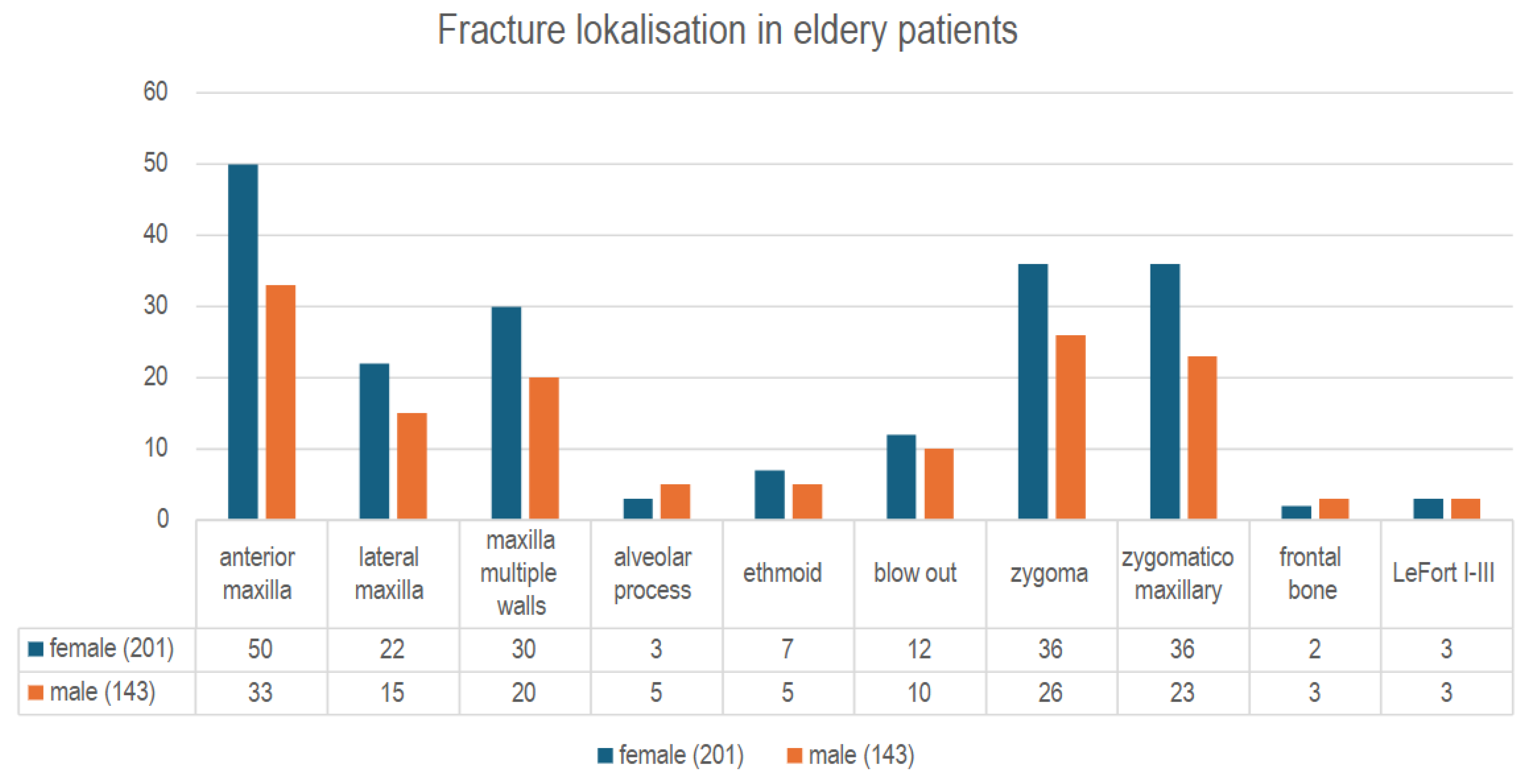

Fracture Localization in Elderly Fall Patients

Among elderly patients with fall-related injuries, the most frequently affected anatomical sites were the anterior maxillary wall (24.9%) the zygomaticomaxillary complex (17.9%), and the zygoma (17.9%). A statistically significant difference in fracture localization was found between elderly males and females (p = 0.047). Specifically, fractures involving the lateral maxillary wall (11.8% vs. 2.6%) and multiple maxillary walls (18.7% vs. 12.1%) were more frequent in women, while men had a higher proportion of zygomatic (24.1% vs. 17.6%) and zygomaticomaxillary fractures (22.4% vs. 19.3%) (

Figure 7). These anatomical trends highlight the need for gender-sensitive diagnostic attention in geriatric trauma imaging.

Discussion

This retrospective analysis confirms that low-energy falls are the leading cause of midfacial fractures in elderly patients, especially among women. The disproportionately high incidence in females aged ≥65 may be attributed to several interrelated factors, including osteoporosis [

4,

6,

16], edentulism [

3,

8], and a generally higher fall risk [

8,

20]. Demographic factors may also contribute in Hungary, women over the age of 65 outnumber men by nearly 1.5 to 1 [

24], which likely influences the gender distribution observed in fall-related injuries. These findings align with previous studies emphasizing the vulnerability of the aging midface due to reduced bone density and diminished structural resilience [

3,

8,

9,

20].

The fracture pattern in elderly patients differed markedly from that of younger individuals, with zygomatic and anterior maxillary wall fractures being most prevalent following falls [

3,

6,

8,

13,

21]. In contrast, high-energy etiologies such as traffic accidents and interpersonal violence were more typical in the under-65 group [

12,

15,

18]. The strong gender disparity in injury mechanisms — with women experiencing a higher rate of fall-related fractures — underscores the need for gender-sensitive prevention efforts.

Hospitalization rates were notably lower in elderly patients, and conservative management was more commonly employed in fall-related cases. This likely reflects both the low-impact nature of the trauma and a more cautious therapeutic approach, balancing surgical risks with expected functional benefits [

6,

10]. These trends echo findings in the maxillofacial trauma literature that advocate for individualized, age-adapted treatment plans in geriatric patients [

2,

15,

17].

Our data also revealed that associated injuries — particularly to the lower extremities — are more common in elderly and female patients, suggesting the need for multidisciplinary trauma assessment and care [

7,

14]. The high prevalence of comorbidities and polypharmacy in this age group further reinforces the importance of integrating geriatric expertise into trauma management protocols [

2,

6,

19,

22]. Notably, international studies from Africa, India, Malaysia but also Poland report contrasting findings — with significantly fewer elderly patients and fall-related cases among midfacial fracture populations — highlighting the influence of differing demographic structures, healthcare access, and injury mechanisms across countries [

9,

11,

14,

18].

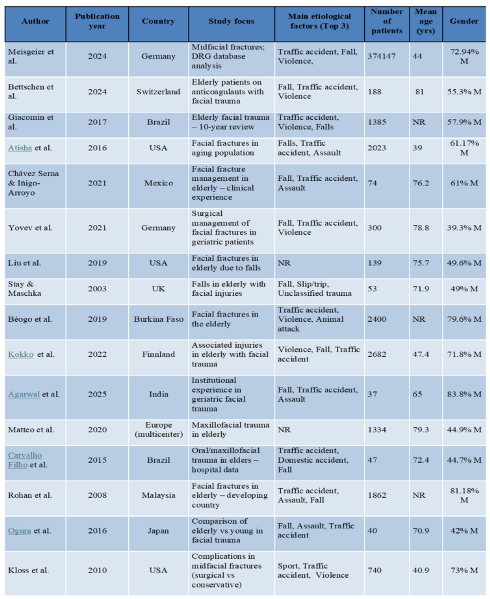

Table 4 summarizes the demographic characteristics of the studies referenced in the present analysis. Beyond surgical considerations, dental rehabilitation in elderly patients with midfacial trauma poses unique challenges. Age-related edentulism and reduced bone quality often render even significant occlusal disturbances clinically less relevant, especially when the maxilla is involved [

5,

22]. Unlike mandibular trauma, maxillary fractures rarely result in complex prosthetic dilemmas due to the anatomical and functional characteristics of the upper arch [

3,

4,

6,

13]. However, poor bone quality frequently contraindicates the use of dental implants [

3], and the generally lower demand for advanced prosthetic care among elderly Hungarian patients — compared to their Western European counterparts — further reduces the clinical imperative for aggressive rehabilitation.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, its retrospective and single-center design may limit generalizability. Second, only the most severe associated injury was recorded in polytraumatized patients, which likely underestimates the total burden of trauma. Lastly, dental status was classified based on chart data rather than clinical intraoral examination, which may have introduced misclassification bias.

Conclusion

Midfacial fractures in elderly patients are predominantly the result of low-energy falls and often do not necessitate surgical intervention or hospitalization. The presence of comorbidities and elevated perioperative risks frequently supports a conservative treatment approach. Demographic factors—particularly the higher proportion of elderly women—appear to influence injury patterns. Recognizing these age- and gender-specific trauma profiles is essential for developing individualized care strategies and for avoiding overtreatment, particularly in cases where dental rehabilitation is unlikely to yield substantial functional or quality-of-life benefits due to anatomical limitations or socioeconomic constraints.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.O. ; Methodology, E.O., J.S..; Formal analysis, L.M.; Investigation, O.E. ; Data curation, O.E..; Resources, J.S. ; Writing—original draft preparation, E.O.; Writing—review and editing, J.S.; Visualization, L.M.; Supervision, J.S. and L.O.; Project administration, E.O. All authors have read and agreed to the submitted version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Department of Radiology and the hospital archives team for their valuable assistance in data collection and management.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest related to this study.

References

- Meisgeier A, Pienkohs S, Dürrschnabel F, Moosdorf L, Neff A. Epidemiologic Trends in Maxillofacial Trauma Surgery in Germany—Insights from the National DRG Database 2005–2022. J Clin Med. 2024;13(15):4438. [CrossRef]

- Bettschen D, Kronenberg J, Kruse A, Rücker M, Wanner GA, Rücker M. Epidemiology of maxillofacial trauma in elderly patients receiving oral anticoagulant or antithrombotic medication: a Swiss retrospective study. BMC Emerg Med. 2024;24(1):39. [CrossRef]

- Giacomin M, De Conto F, Siqueira SP, Signori PH, Eidt JMS, Sawazaki R. Elderly patients with facial trauma: a ten-year review. Rev Bras Geriatr Gerontol. 2017;20(5):618–623. [CrossRef]

- Atisha DM, Burr TVR, Allori AC, Puscas L, Erdmann D, Marcus JR. Facial Fractures in the Aging Population. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2016;137(2S):39-49. [CrossRef]

- Chávez Serna E, Iñigo-Arroyo F. Management of Facial Fractures in the Elderly Patient: Experience of the Orthognathic Surgery and Facial Trauma Clinic of the Gea González Hospital. J Am Coll Surg. 2021;233(5S2):e161–e162. [CrossRef]

- Yovev T, Burnic A, Kniha K, Knobe M, Hölzle F, Modabber A. Surgical Management of Facial Fractures in Geriatric Patients. J Craniofac Surg. 2021;32(6):2082–2086. [CrossRef]

- Liu FC, Halsey JN, Oleck NC, Lee ES, Granick MS. Facial Fractures as a Result of Falls in the Elderly: Concomitant Injuries and Management Strategies. Craniomaxillofac Trauma Reconstr. 2019;12(1):45–53. [CrossRef]

- Stay E, Maschka D. Falls in elderly people that result in facial injuries. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2003;41(2):138–142. [CrossRef]

- Béogo R, Coulibaly TA, Traoré I, Mabika BDD, Zoma E. Facial Fractures in the Elderly: Epidemiology and Outcome in 103 Patients. Int J Clin Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2019;4(2):48–51.

- Kokko LL, Puolakkainen T, Suominen A, Snäll J, Thorén H. Are the Elderly With Maxillofacial Injuries at Increased Risk of Associated Injuries? Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2022;60(4):387–392. [CrossRef]

- Agarwal S, Krishnan M, Arularasan G, Lakshmanan S. Single Institutional Experience of Geriatric Maxillofacial Trauma Patients: A Retrospective Study. J Korean Assoc Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2025;51(2):102–107. [CrossRef]

- Matteo M, et al. Management of Maxillofacial Trauma in the Elderly: A European Multicenter Study. Dent Traumatol. 2020;36(3):241–246. [CrossRef]

- Carvalho Filho MAM, Saintrain MVL, Dos Anjos RES, Pinheiro SS, Cardoso LCP, Moizan JAH, de Aguiar ASW. Prevalence of Oral and Maxillofacial Trauma in Elders Admitted to a Reference Hospital in Northeastern Brazil. PLoS One. 2015;10(8):e0135813. [CrossRef]

- Royan SJ, Hamid AL, Kovilpillai FJ, Junid NZ, Wan Mustafa WM. A Prospective Study on Elderly Patients With Facial Fractures in a Developing Country. Gerodontology. 2008;25(2):124–128. [CrossRef]

- Ogura I, Hirahara N, Muraoka H, Fukuda T. Characteristics of Maxillofacial Fractures in Elderly Patients Compared With Young Patients. Int J Oral-Med Sci. 2016;15(1):10–16. [CrossRef]

- Kloss FR, Stigler RG, Brandstätter A, Tuli T, Rasse M, Laimer K, Hächl OL, Gassner R. Complications Related to Midfacial Fractures: Operative Versus Non-Surgical Treatment. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2011;40(1):33–37. [CrossRef]

- Rahimpour A, Baxter J, Giangrosso G, Murphy A, Bown P, Denning DA, Ray P, Rahman B. Age-Related Patterns of Traumatic Facial Fractures in the Appalachian Tri-state Area: A Five-Year Retrospective Study. Cureus. 2024;16(6):e62090. [CrossRef]

- Michalak P, Wyszyńska-Pawelec G, Szuta M, Hajto-Bryk J, Zapała J, Zarzecka JK. Fractures of the Craniofacial Skeleton in the Elderly: Retrospective Studies. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(21):11219. [CrossRef]

- Atinga A, Shekkeris A, Fertleman M, Batrick N, Kashef E, Dick E. Trauma in the Elderly Patient. Br J Radiol. 2018;91(1087):20170739. [CrossRef]

- Kannus P, Niemi S, Parkkari J. Rising incidence of fall-induced maxillofacial injuries among older adults. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2016;28(6). [CrossRef]

- Kerschbaum M, Lang S, Henssler L, et al. Influence of Oral Anticoagulation and Antiplatelet Drugs on Outcome of Elderly Severely Injured Patients. J Clin Med. 2021;10(8):1649. [CrossRef]

- Pagin M, Mabire C, Cotton M, Zingg T, Carron PN. Retrospective Analysis of Geriatric Major Trauma Patients Admitted in the Shock Room of a Swiss Academic Hospital: Characteristics and Prognosis. J Clin Med. 2020;9(5):1343. [CrossRef]

- MedCalc Software Ltd. Odds ratio calculator. Available online: https://www.medcalc.org/calc/odds_ratio.php (accessed on 18 June 2025).

- Klinger A, Monostori J, Spéder Z, szerk. Demográfiai Atlasz – Magyarország népessége térben és időben. Budapest: Központi Statisztikai Hivatal (KSH); 2021. https://www.ksh.hu/apps/shop.kiadvany?p_kiadvany_id=1117141.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).