Keywords Alzheimer’s disease; Cognitive decline; CPAP; Mild cognitive impairment; Obstructive sleep apnea

Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most prevalent neurodegenerative disorder, accounting for approximately 60-70% of dementia cases globally, and is characterized by progressive cognitive decline, memory impairment, and behavioral disturbances [

1,

2]. The disease manifests through the accumulation of amyloid-beta (Aβ) plaques and neurofibrillary tangles of hyperphosphorylated tau protein in the brain, leading to synaptic dysfunction, widespread neuronal death, and atrophy, particularly in regions crucial for memory and cognitive function [

3,

4,

5]. Despite extensive research and significant advances in the understanding of the molecular and cellular mechanisms underlying AD, there remains no cure, and current treatments focus on symptom management rather than addressing the root causes of the disease [

3,

6,

7].

The prodromal stage of AD is characterized by the presence of Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI), which consists in cognitive decline that does not interfere significantly with daily life activities [

8,

9]. This is a critical period for early intervention, as it represents the initial stage before onset of dementia [

7,

8,

9]. Individuals with MCI have annual conversion rates to AD ranging from 10-15% [

4].

One of the most significant recent advances in neurobiology has been the discovery of the glymphatic system, a brain-wide network responsible for clearing metabolic waste products from the central nervous system (CNS), including Aβ [

3,

10,

11]. This process is crucial for preventing the accumulation of Aβ and other toxic proteins that are implicated in the pathogenesis of AD [

12,

13]. The glymphatic system is highly dependent on the sleep-wake cycle, with its activity probably being most pronounced during slow-wave sleep (SWS) phase of non-rapid eye movement sleep (NREM) characterized by low-frequency, high-amplitude delta waves [

12,

13]. Studies have shown that the efficacy of the glymphatic system declines with age, which, coupled with sleep disturbances common in older adults, may contribute to the increased risk of AD and accelerate its progression observed in the aging population [

11,

12].

Sleep plays a fundamental role in cognitive health, with disturbances in sleep being increasingly recognized as both a symptom and a contributing factor to neurodegenerative diseases like AD [

2,

10,

14]. Sleep disturbances, including insomnia, fragmented sleep, and Obstructive Sleep Apnea (OSA), are prevalent among older adults and particularly in individuals with AD [

14]. OSA is one of the sleep alterations with higher prevalence in AD, affecting between 43% and 91% of patients [

14,

15]. It is characterized by repeated episodes of partial or complete obstruction of the upper airway during sleep [

14,

16]. OSA leads to intermittent hypoxia, hypercapnia, frequent arousals, and significant fragmentation of sleep, particularly reducing the duration and quality of SWS [

14,

15,

16]. OSA is also a potential cause of cognitive impairment, likely due to multiple potential mechanisms including oxidative stress, increased inflammation and the presence of cerebral small-vessel lesions [

17]. This underscores the current significance of medical treatments.

Continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) therapy is the gold standard treatment for OSA and has been proven to be effective in improving sleep quality by preventing airway collapse during sleep [

15,

16,

18]. It increases the duration and quality of SWS, potentially enhancing the glymphatic system’s function and reducing the risk of Aβ accumulation in the brain [

15,

18]. Several studies have demonstrated that CPAP adherence in patients with OSA and MCI/AD can normalize sleep breathing and possibly lead to a better cognition, which specific cognitive domains still need to be determined [

15]. Other studies have also reported that CPAP could increase CSF flow rate in anaesthetised rats, suggesting a possible therapeutic enhancement of glymphatic function [

18].

Given the significant overlap between the prevalence of sleep disturbances in AD, as well as the potential for CPAP therapy to mitigate cognitive decline, this study aimed to explore the intricate relationship between OSA, and MCI progression. We found that patients diagnosed with MCI and OSA with good CPAP adherence had improved sleep parameters and cognitive decline outcomes at 12 months follow-up, compared to those that did not use CPAP devices.

Methods

Study design and participants inclusion

The current study consists of a sub-analysis of a prospective interventional and longitudinal pilot study. We included participants with MCI referred to the Cognition and Behaviour Unit at the Department of Neurology, Hospital Universitari MútuaTerrassa (HUMT) in Terrassa, Barcelona, Spain. Ethical approval from the local ethics committee was obtained.

Participants with a diagnosis of MCI (confirmed by a Delayed Memory Index (DMI) below 85 on the Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status (RBANS), a Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) score below 27, or a Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) score of at least 0.5) and sufficient reading and writing skills to complete cognitive tests were included. AD pathology was confirmed by positive CSF AD biomarkers or positive 18F Flutemetamol PET/CT. AD biomarkers in CSF were measured by Catlab according to the established local cut-off values. Patients were considered positive for AD biomarkers when Aβ1-42/Aβ1-40 was < 0.068 pg/mL plus two more of the following: t-tau (> 404 pg/mL), p-tau 181 (> 52.1 pg/mL), Aβ1-42 (< 638pg/mL), t-tau/ Aβ1-42 (> 0.784). For the current study, all the patients were required to have sleep registry with overnight video-polysomnography(V-PSG).

Exclusion criteria included a prior diagnosis of other neurocognitive disorders, a history of affective disorders or psychosis, current participation in cognitive training programs, or the use of psychotropic medications affecting cognition. Those with a history of cerebrovascular accidents, transient ischemic attacks, or traumatic brain injury, as well as individuals with conditions likely to interfere with the study procedures, were also excluded.

Cognitive assessment

Baseline cognitive assessments with CDR, MMSE and RBANS tests were conducted, followed by a re-evaluation after 12 months.

CDR assesses the following areas: Memory, Orientation, Judgement and Problem Solving, Community Affairs, Home and Hobbies and Personal Care. It generates a semi-quantitative and categorical score that classifies different levels of cognitive impairment, with higher scores indicating more severe impairment.

MMSE consists of five parts: Orientation, Registration, Attention, Calculation, Recall and Language. Each section contains questions that contribute to determining the cognitive impairment score.

RBANS is composed of five indexes, which are Immediate Memory Index (IMI), Visuospatial Index (VSPI), Language Index (LNGI), Attention Index (ATI), and Delayed Memory Index (DMI). To determine the value of each index, different subtests are also considered. IMI: List Learning (LL) and Story Memory (SM); VSPI: Figure Copy (FC) and Line Orientation (LO); LNGI: Picture Naming (PN) and Semantic Fluency (SF); ATI: Direct Digit Span (DDS), Indirect Digit Span (IDS) and Coding (C); DMI: List Recall (LR), List Recognition (LRe), Story Recall (SR) and Figure Recall (FR). To minimize learning effects, a parallel version of the same cognitive battery was used (version A at baseline and version B at follow-up). In both the MMSE and RBANS, lower scores indicate more severe cognitive impairment.

Video-polysomnography (V-PSG) and sleep architecture

Participants underwent overnight V-PSG at Adsalutem sleep unit, where one sleep night was recorded using a comprehensive setup including synchronized audiovisual recording, electroencephalography (EEG; F3, F4, C3, C4, O1, and O2, referred to the combined ears), electrooculography (EOG), electrocardiography, surface electromyogram (EMG) of the right and left anterior tibialis in the lower limbs. Nasal cannula, nasal and oral thermistors, thoracic and abdominal strain gauges, and finger pulse oximeter were used to measure the respiratory variables. Sleep stages and respiratory events were scored according to the American Academy of Sleep Medicine’s Manual for Scoring of Sleep and Associated Events, Version 3. All participants from the current sub-study were diagnosed with OSA. The OSA’s severity was established from the Apnea-Hypopnea Index (AHI), extracted from the V-PSG, considering the following limits: Mild OSA (AHI: 5-15 events/hour), Moderate OSA (AHI: 15-30 events/hour) and Severe OSA (AHI: > 30 events/hour) [

19].

From V-PSG, we obtained the following sleep parameters: Duration of sleep stages, composed of non-rapid eye movement (NREM), sleep stages N1, N2 and N3; and duration of rapid eye movement (REM) sleep, total time in bed (total amount of time spent in bed including both sleep and wake periods), total sleep time (amount of time spent sleeping), sleep efficiency (ratio of the total sleep time to the time in bed, that could be affected by sleep disruptions) and wakefulness (amount of time spent awake while in bed), sleep position, including supine prone, right and left side times. All these variables are measured in minutes, except sleep efficiency, which is indicated in percentage (%).

Patients diagnosed with moderate or severe OSA were prescribed CPAP based on standard medical criteria.

Statistical Analysis

Participants were classified into two groups: those who used CPAP (due to prescription and tolerance of the device) and those who did not (because of lack of prescription in mild OSA or lower tolerance). The median, minimum and maximum were calculated for the demographic data of each group, while the mean and standard deviation were calculated for neuropsychological test’s parameters. Differences in neuropsychological test scores were assessed by subtracting baseline values from follow-up scores (e.g., MMSE = 12 Months MMSE – Baseline MMSE).

The normality of the data was assessed with Shapiro-Wilk test. Demographic features were compared between CPAP and non-CPAP groups using T-tests and Fisher’s exact tests, as appropriate, based on the normality. Longitudinal changes in CDR were assessed using Stuart-Maxwell test. Longitudinal changes in the other neurocognitive scores were analyzed using both Spearman and Pearson correlation tests for the full sample. The effect of CPAP treatment in the cognitive progression between the baseline and 12 months follow-up (CDR, MMSE, RBANS Total and RBANS sub-domains) was assessed using Generalized Linear Models (GLM) with baseline cognitive outcomes and AHI as covariates. Using GLM, the association among PSG variables and the cognitive variables was also evaluated, with the baseline results of the neuropsychological tests and CPAP as covariates. All statistical analyses were conducted in RStudio (version 4.4.2). The results were considered statistically significant when the p-value was lower than 0.05 and the correlation coefficient (r) higher than 0.3.

Results

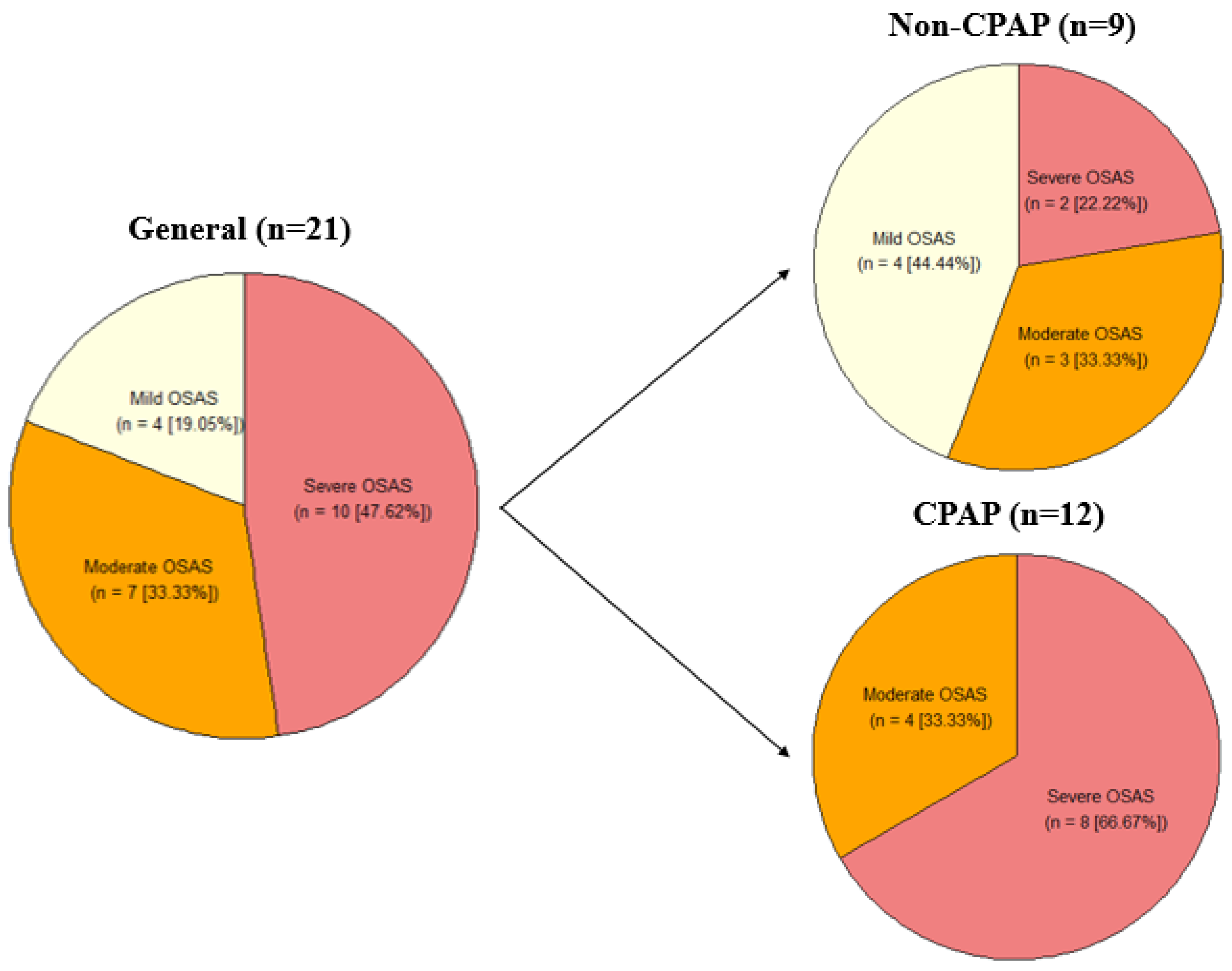

Demographic description of the CPAP and non-CPAP groups

A total of 21 patients with MCI were included in this study. The median age of the sample was 77 years (60-81), and 71% (n = 15) were female. All patients were diagnosed with some OSA degree and accordingly, they were prescribed with CPAP. 57% (n = 12) of patients were compliant in CPAP use ( ≥ 4h/night on, at least, 70% of nights). No statistically significant differences were found in sex and education between CPAP users and non-users (

Table 1), but statistically differences were identified in age (p-value = 0.010), the CPAP group being younger than the non-CPAP group (

Figure 1).

CPAP results

Longitudinal Cognitive Status

When focusing on the full cohort included in the current study, statistically significant decline in neurocognitive performance at the 12-month follow-up compared with the baseline assessment were identified in CDR (p = 0.223), MMSE (p = < 0.001), RBANS Total (p = < 0.001), RBANS IMI (p = < 0.001), RBANS LL (p = < 0.001), RBANS SM (p = 0.001), RBANS SF (p = < 0.001), RBANS ATI (p = < 0.001), RBANS DDS (p = 0.005), RBANS C (p = < 0.001), RBANS DMI (p = 0.003), RBANS SR (p = 0.002) and RBANS FR (p = 0.003). On the other hand, RBANS LO (p = 0.031), RBANS LNGI (p = < 0.001), RBANS PN (p = 0.016), and RBANS LR (p = 0.003) presented better performance at the 12-month follow-up compared with the baseline (

Table 2).

When comparing the difference between 12-month follow-up and baseline results in the CPAP and non-CPAP groups, a statistically significant difference was found in Δ MMSE, with lower cognitive decline in the CPAP group (p = 0.016). Statistically significant differences were also identified in Δ RBANS Total (p = 0.028), Δ RBANS FC (p = 0.010) and Δ RBANS SF (p = 0.045), with cognitive improvement in the CPAP group (

Table 3).

Effect of sleep in cognitive progression.

The association between sleep parameters measured at baseline and cognitive progression was evaluated. Only cognitive variables that changed between baseline and 12-months follow-up (

Table 2) were evaluated. To ensure that the results were not influenced using CPAP, the use of this device was considered as covariate for those analyses where a cognitive variable identified a previous analysis without covariates was associated with CPAP.

From the different sleep stages (

Table 4), N2 duration showed a significant negative correlation with Δ MMSE, while N3 had a significant positive correlation with Δ MMSE and Δ RBANS FR. REM duration was associated with better cognitive progression measured with Δ RBANS IMI and Δ RBANS LL. From the other sleep parameters, total sleep time showed a significant positive correlation with Δ RBANS IMI, Δ RBANS LL, Δ RBANS SM, Δ RBANS SF, Δ RBANS C and Δ RBANS SR. Sleep efficiency was positively correlated with Δ RBANS LL, Δ RBANS SF and RBANS C, while wakefulness had a significant negative correlation with Δ RBANS LL, Δ RBANS SF and Δ RBANS C. About the sleep position variables, supine time had a significant negative correlation with Δ MMSE, Δ RBANS LO, and Δ RBANS DDS and right side time had a significant positive correlation with Δ MMSE and Δ RBANS LO. All these results were independent from the use of CPAP.

Discussion

In this study, we reported a positive clinical effect of CPAP on cognitive progression in specific cognitive domains. Furthermore, we show an association between baseline sleep patterns, including N2 and N3 time, supine and right-side time with cognitive progression at 12 months follow-up.

Cognitive Progression in the full cohort

The full cohort showed a decline in almost all significant cognitive variables, which is expected in patients with MCI or AD and OSA. Participants improved their scores in RBANS LO, RBANS LNGI, RBANS PN and RBANS LR. RBANS LO and RBANS LR variables show a cognitive improvement in the CPAP group, while a worsening in non-CPAP group, indicating that this may be attributed to the positive effects of CPAP therapy. For the other two improved variables, RBANS LNGI and RBANS PN, improved scores were greatest in the CPAP group, but the cognition scores for both CPAP and non-CPAP groups improved. This is not consistent with the current literature and with what we expected (cognitive decline in the non-CPAP group, at least) [

20]. Potential reasons for unexpected outcomes such as improved cognitive scores could be associated with the small size of the full cohort (n = 21).

Impact of the CPAP on Cognitive Progression

The positive effect of CPAP on cognitive progression was reported in previous studies. CPAP use was linked with a significant t-tau and t-tau/Aβratio reduction in plasma of OSA patients in a 3-month follow-up [

21]. This was translated with an Aβ increase in CSF, which have been also correlated with a decreased brain deposition [

22] in a 1-year study with a patient with OSA and subjective cognitive impairment, obtaining the normalization of the cerebral Aβ dynamics and t-tau/Aβ and Aβ/Aβ ratios [

23]. Previous studies characterized one of the main features of OSA, intermittent hypoxia during sleep, as one of the causes of cognitive decline before AD symptomatology [

24,

25,

26]. During sleep, the dysfunction of the glymphatic system has been implicated as a mechanism for accumulation of Aβ in the brain [

27]. This could be related with the cognitive worsening that was obtained in MMSE scores in patients with OSA [

28], as well as in other domains (memory, attention, visuospatial, language, etc.) [

29]. Other studies also observed slow cognitive decline or cognitive improvement in patients with OSA and AD when treated with CPAP [

30,

31,

32].

Our results are consistent with these studies, obtaining that CPAP use was significantly associated with slower decline in Δ MMSE and an improvement in Δ RBANS Total, as well as an improvement in Δ RBANS FC and Δ RBANS SF sub-domains in a 12 months follow-up study in patients with OSA and MCI due to AD. These results are due to CPAP impact on sleep quality improvement, as well as an increase in oxygenation and a reduction in neuroinflammation [

33]. Consequently, a better concentration and memory makes these two sub-domains to be significantly improved [

34].

Effect of sleep parameters on Cognitive Progression

The relationship between sleep variables, CPAP therapy and cognition has been investigated in multiple studies studies in patients with OSA. However, examining it in patients with OSA and MCI could provide important insights into its appropriate use in patients with cognitive decline.

NREM N2, N3 and REM sleep are critical for cognitive health. N2 was longer in OSA patients and shorter in control and OSA-CPAP groups [

35,

36]. NREM N3 sleep is the main stage in which the glymphatic system is effective [

37]. The impact of this enhancement is an improved clearance of metabolic products in the brain, including Aβ, generating less deposition of this protein and an improved cognition when this stage is prolonged. Shorter REM is associated with lower performance in neuropsychological tests [

38,

39]. The results obtained in our study are consistent with this literature for NREM N2, in which longer stage has been associated with cognitive worsening in Δ MMSE, as well as for NREM N3, with longer stages correlated with cognitive improvement in Δ MMSE and Δ RBANS FR, and REM sleep, with longer duration associated with better cognition in Δ RBANS IMI and Δ RBANS LL.

Total sleep time and sleep efficiency also play significant roles in maintaining cognitive health. Studies have demonstrated that higher total sleep time would facilitate the repetition of sleep cycles, allowing NREM N3 to be longer [

40]. Other studies have also described that sleep duration shorter or longer than certain limits, generally described as < 5h and > 9h in 70-year-old participants, would be associated with worsening cognition with a quadratic trend that can not be well-established with linear models [

41]. There are disruptions too, like wakefulness that can affect sleep efficiency, which in turn can further fragment sleep when it is longer, generating poor cognition [

42]. This data supports our results for total sleep time, sleep efficiency and wakefulness as longer total sleep time was associated with better cognition in Δ RBANS IMI, Δ RBANS LL, Δ RBANS SM, Δ RBANS SF, Δ RBANS C, and Δ RBANS SR, higher sleep efficiency was correlated with cognitive improvement in Δ RBANS LL, Δ RBANS SF, and Δ RBANS C, and longer wakefulness with cognition worsening in Δ RBANS LL, Δ RBANS SF, and Δ RBANS C.

Right side time and supine time are essential to understanding the sleep position importance that have been studied by other research groups. In humans, the “Starling resistor” mechanism in normal conditions prevents the over drainage of cranial venous blood in supine sleeping position. In OSA, this mechanism is altered because a pressure airway drops below a critical value generating the collapse of the upper airway [

43,

44]. This collapse activates a defense mechanism based on a choking feeling that may disrupt sleep in patients affecting their cognition in chronic events [

45]. Lower CPAP pressure can maintain the upper airway open easier in lateral than in supine position, helping to prevent this aforementioned collapse [

46]. The possible reason for this would be a easier collapse in supine than in lateral position caused by gravitational effect. This collapse is associated with an increase of apneas and respiratory disruptions when sleeping [

47], worsening cognition. These studies are consistent with the result obtained for supine time, in which longer time is associated with cognitive decline in Δ MMSE, Δ RBANS LO, and Δ RBANS DDS.

When sleeping in lateral position, it was observed that right position generates an increase in vagal tone and a reduction in sympathetic tone stronger than in left position [

48]. It leads to the highest vagal modulation [

49], where fibers provide parasympathetic innervation to the atria and sinoatrial node, while the left vagal nerve just innervates the ventricles [

50]. Vagus Nerve Stimulation (VNS), an FDA-approved treatment for epilepsy and depression among others, has been associated with increased penetration of CSF into the brain increasing brain waste clearance in mice [

51]. This information could be the reason why longer right side time is associated with cognitive improvement in Δ MMSE and Δ RBANS LO in our study, thus sleeping in a right-side position would cause a stronger activation of parasympathetic tone in heart and affect CSF penetrance.

In the overall literature, it has been described that sleep deprivation evidences a decrease in comprehension, attention, language and memory [

52,

53,

54,

55]. This could explain why we have obtained these results, affecting longer sleep time and greater sleep efficiency to MMSE and to some attention, language and memory RBANS sub-domains. Regarding to the sleep position, it has been observed in our results that these positions could also have consequences. Thus, supine position had a negative effect on MMSE and RBANS sub-domains related with attention and memory, while right side position showed cognitive improvement in MMSE and a memory RBANS sub-domain.

Study Limitations

This study has some limitations. Although prospective, it is a pilot study with a reduced sample size and an unequal distribution of participants between the CPAP (n = 12) and non-CPAP (n = 9) groups. The CPAP compliance in AD patients is more difficult when they are in more advanced stages of the disease. The V-PSG data was derived from a single-night study, which may not fully capture chronic sleep patterns. For future studies, long-term monitoring methods such as actigraphy could provide more robust insights [

56]. Despite these limitations, we have found identified significant results that are consistent with previous literature.

Conclusion

Our findings underscore the potential of CPAP to reduce the rate of cognitive decline in patients with OSA and MCI, demonstrating better cognitive outcomes in CPAP group after a 12 months follow-up. The associations between sleep and cognitive progression highlight the significance of sleep duration and position in maintaining cognitive health. Future studies with larger cohorts and extended monitoring are warranted to validate these findings and explore the role of CPAP in mitigating dementia progression in OSA patients. Additionally, follow-up at 24 months is important to further investigate the differences between groups, as well was, to learn how to improve CPAP adherence in AD patients.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Carmen L. Frias, Natalia Cullell and Jerzy Krupinski; Data curation, Carmen L. Frias and Cristina Artero; Formal analysis, Carmen L. Frias; Funding acquisition, Natalia Cullell and Jerzy Krupinski; Investigation, Carmen L. Frias, Marta Almeria, Judith Castejon, Cristina Artero, Giovanni Caruana, Andrea Elias and Karol Uscamaita; Methodology, Carmen L. Frias; Project administration, Natalia Cullell and Jerzy Krupinski; Resources, Marta Almeria, Judith Castejon, Cristina Artero and Karol Uscamaita; Software, Carmen L. Frias; Supervision, Natalia Cullell and Jerzy Krupinski; Validation, Marta Almeria and Judith Castejon; Visualization, Carmen L. Frias; Writing – original draft, Carmen L. Frias; Writing – review & editing, Marta Almeria, Judith Castejon, Giovanni Caruana, Andrea Elias, Karol Uscamaita, Virginia Hawkins, Nicola J. Ray, Mariateresa Buongiorno, Natalia Cullell and Jerzy Krupinski.

References

- Jiao, B.; Li, R.; Zhou, H.; Qing, K.; Liu, H.; Pan, H.; Lei, Y.; Fu, W.; Wang, X.; Xiao, X.; Liu, X.; Yang, Q.; Liao, X.; Zhou, Y.; Fang, L.; Dong, Y.; Yang, Y.; Jiang, H.; Huang, S.; Shen, L. Neural biomarker diagnosis and prediction to mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer's disease using EEG technology. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2023 Feb 10;15, 32. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayer, G.; Frohnhofen, H.; Jokisch, M.; Hermann, D.M.; Gronewold, J. Associations of sleep disorders with all-cause MCI/dementia and different types of dementia - clinical evidence, potential pathomechanisms and treatment options: A narrative review. Front Neurosci. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Thipani Madhu, M.; Balaji, O.; Kandi, V.; Ca, J.; Harikrishna, G.V.; Metta, N.; Mudamanchu, V.K.; Sanjay, B.G.; Bhupathiraju, P. Role of the Glymphatic System in Alzheimer's Disease and Treatment Approaches: A Narrative Review. Cureus. 2024 Jun 29;16, e63448. [CrossRef]

- Hussain, R.; Graham, U.; Elder, A.; Nedergaard, M. Air pollution, glymphatic impairment, and Alzheimer's disease. Trends Neurosci. 2023 Nov;46, 901-911. [CrossRef]

- Ekanayake, A.; Peiris, S.; Ahmed, B.; Kanekar, S.; Grove, C.; Kalra, D.; Eslinger, P.; Yang, Q.; Karunanayaka, P. A Review of the Role of Estrogens in Olfaction, Sleep and Glymphatic Functionality in Relation to Sex Disparity in Alzheimer's Disease. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2024 Jan-Dec;39:15333175241272025. [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Jordan, J.D.; Zhang, Q. Early life adversity as a risk factor for cognitive impairment and Alzheimer's disease. Transl Neurodegener. 2023 May 12;12, 25. [CrossRef]

- Heutz, R.; Claassen, J.; Feiner, S.; Davies, A.; Gurung, D.; Panerai, R.B.; Heus, R.; Beishon, L.C. Dynamic cerebral autoregulation in Alzheimer's disease and mild cognitive impairment: A systematic review. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2023 Aug;43, 1223-1236. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Coury, R.; Tang, W. Prediction of conversion from mild cognitive impairment to Alzheimer's disease and simultaneous feature selection and grouping using Medicaid claim data. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2024 Mar 9;16, 54. [CrossRef]

- Matuskova, V.; Veverova, K.; Jester, D.J.; Matoska, V.; Ismail, Z.; Sheardova, K.; Horakova, H.; Cerman, J.; Laczó, J.; Andel, R.; Hort, J.; Vyhnalek, M. Mild behavioral impairment in early Alzheimer's disease and its association with APOE and BDNF risk genetic polymorphisms. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2024 Jan 26;16, 21. [CrossRef]

- Astara, K.; Tsimpolis, A.; Kalafatakis, K.; Vavougios, G.D.; Xiromerisiou, G.; Dardiotis, E.; Christodoulou, N.G.; Samara, M.T.; Lappas, A.S. Sleep disorders and Alzheimer's disease pathophysiology: The role of the Glymphatic System. A scoping review. Mech Ageing Dev. 2024 Feb;217:111899. [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Liu, K.; Zhu, J. Glymphatic system: an emerging therapeutic approach for neurological disorders. Front Mol Neurosci. 2023 Jul 6;16:1138769. [CrossRef]

- Voumvourakis, K.I.; Sideri, E.; Papadimitropoulos, G.N.; Tsantzali, I.; Hewlett, P.; Kitsos, D.; Stefanou, M.; Bonakis, A.; Giannopoulos, S.; Tsivgoulis, G.; Paraskevas, G.P. The Dynamic Relationship between the Glymphatic System, Aging, Memory, and Sleep. Biomedicines. 2023 Jul 25;11, 2092. [CrossRef]

- Örzsik, B.; Palombo, M.; Asllani, I.; Dijk, D.J.; Harrison, N.A.; Cercignani M. Higher order diffusion imaging as a putative index of human sleep-related microstructural changes and glymphatic clearance. Neuroimage. 2023 Jul 1;274:120124. [CrossRef]

- Simmonds, E.; Levine, K.S.; Han, J.; Iwaki, H.; Koretsky, M.J.; Kuznetsov, N.; Faghri, F.; Solsberg, C.W.; Schuh, A.; Jones, L.; Bandres-Ciga, S.; Blauwendraat, C.; Singleton, A.; Escott-Price, V.; Leonard, H.L.; Nalls, M.A. Sleep disturbances as risk factors for neurodegeneration later in life. medRxiv [Preprint]. 2023 Nov 9:2023.11.08.23298037. [CrossRef]

- Oliver, C.; Li, H.; Biswas, B.; Woodstoke, D.; Blackman, J.; Butters, A.; Drew, C.; Gabb, V.; Harding, S.; Hoyos, C.M.; Kendrick, A.; Rudd, S.; Turner, N.; Coulthard, E. A systematic review on adherence to continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) treatment for obstructive sleep apnoea (OSA) in individuals with mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer's disease dementia. Sleep Med Rev. 2024 Feb;73:101869. [CrossRef]

- Richards, K.C.; Lozano, A.J.; Morris, J.; Moelter, S.T.; Ji, W.; Vallabhaneni, V.; Wang, Y.; Chi, L.; Davis, E.M.; Cheng, C.; Aguilar, V.; Khan, S.; Sankhavaram, M.; Hanlon, A.L.; Wolk, D.A.; Gooneratne, N. Predictors of Adherence to Continuous Positive Airway Pressure in Older Adults With Apnea and Amnestic Mild Cognitive Impairment. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2023 Oct 9;78, 1861-1870. [CrossRef]

- Ke, S., Luo, T., Ding, Y. et al. Does Obstructive sleep apnea mediate the risk of cognitive impairment by expanding the perivascular space?. Sleep Breath 29, 130 (2025). [CrossRef]

- Ozturk, B.; Koundal, S.; Al Bizri, E.; Chen, X.; Gursky, Z.; Dai, F.; Lim, A.; Heerdt, P.; Kipnis, J.; Tannenbaum, A.; Lee, H.; Benveniste, H. Continuous positive airway pressure increases CSF flow and glymphatic transport. JCI Insight. 2023 Jun 22;8, e170270. [CrossRef]

- Kapur, V.K.; Auckley, D.H.; Chowdhuri, S.; Kuhlmann, D.C.; Mehra, R.; Ramar, K.; Harrod, C.G. Clinical Practice Guideline for Diagnostic Testing for Adult Obstructive Sleep Apnea: An American Academy of Sleep Medicine Clinical Practice Guideline. J Clin Sleep Med. 2017 Mar 15;13, 479-504. [CrossRef]

- Duff, K.; Suhrie, K.R.; Hammers, D.B.; Dixon, A.M.; King, J.B.; Koppelmans, V.; Hoffman, J.M. Repeatable battery for the assessment of neuropsychological status and its relationship to biomarkers of Alzheimer's disease. Clin Neuropsychol. 2023 Jan;37, 157-173. [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.T.; Huang, H.T.; Hung, H.Y.; Lin, S.Y.; Hsu, W.H.; Lee, F.Y.; Kuan, Y.C.; Lin, Y.T.; Hsu, C.R.; Stettler, M.; Yang, C.M.; Wang, J.; Duh, P.J.; Lee, K.Y.; Wu, D.; Lee, H.C.; Kang, J.H.; Lee, S.S.; Wong, H.J.; Tsai, C.Y.; Majumdar, A. Continuous Positive Airway Pressure Reduces Plasma Neurochemical Levels in Patients with OSA: A Pilot Study. Life (Basel). 2023 Feb 22;13, 613. [CrossRef]

- Grimmer, T.; Riemenschneider, M.; Förstl, H.; Henriksen, G.; Klunk, W.E.; Mathis, C.A.; Shiga, T.; Wester, H.J.; Kurz, A.; Drzezga, A. Beta amyloid in Alzheimer's disease: increased deposition in brain is reflected in reduced concentration in cerebrospinal fluid. Biol Psychiatry. 2009 Jun 1;65, 927-34. [CrossRef]

- Claudio Liguori, Agostino Chiaravalloti, Francesca Izzi, Marzia Nuccetelli, Sergio Bernardini, Orazio Schillaci, Nicola Biagio Mercuri, Fabio Placidi, Sleep apnoeas may represent a reversible risk factor for amyloid-β pathology, Brain, Volume 140, Issue 12, December 2017, Page e75, . [CrossRef]

- Ma, J., Chen, M., Liu, GH. et al. Effects of sleep on the glymphatic functioning and multimodal human brain network affecting memory in older adults. Mol Psychiatry (2024). [CrossRef]

- Jackson, M.L.; Howard, M.E.; Barnes, M. Cognition and daytime functioning in sleep-related breathing disorders. Prog Brain Res. 2011;190:53-68. [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.J.; Lee, D.A.; Shin, K.J.; Park, K.M. Glymphatic system dysfunction in obstructive sleep apnea evidenced by DTI-ALPS. Sleep Med. 2022 Jan;89:176-181. [CrossRef]

- Kamagata K, Andica C, Takabayashi K, Saito Y, Taoka T, Nozaki H, Kikuta J, Fujita S, Hagiwara A, Kamiya K, Wada A, Akashi T, Sano K, Nishizawa M, Hori M, Naganawa S, Aoki S; Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative. Association of MRI Indices of Glymphatic System With Amyloid Deposition and Cognition in Mild Cognitive Impairment and Alzheimer Disease. Neurology. 2022 Dec 12;99, e2648-e2660. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, L.; Wang, K.; Shen, H.; Xu, Y.; Wang, J.; Chen, R. Effects of continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) therapy on neurological and functional rehabilitation in Basal Ganglia Stroke patients with obstructive sleep apnea: A prospective multicenter study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2019 Jul;98, e16344. [CrossRef]

- Bubu, O.M.; Andrade, A.G.; Umasabor-Bubu, O.Q.; Hogan, M.M.; Turner, A.D.; de Leon, M.J.; Ogedegbe, G.; Ayappa, I.; Jean-Louis, G.G.; Jackson, M.L.; Varga, A.W.; Osorio, R.S. Obstructive sleep apnea, cognition and Alzheimer's disease: A systematic review integrating three decades of multidisciplinary research. Sleep Med Rev. 2020 Apr;50:101250. [CrossRef]

- Richards K.C., Gooneratne N., Dicicco B., et. al.: CPAP adherence may slow 1-year cognitive decline in older adults with mild cognitive impairment and apnea. J Am Geriatr Soc 2019; 67: pp. 558-564.

- Ancoli-Israel S., Palmer B.W., Cooke J.R., et. al.: Cognitive effects of treating obstructive sleep apnea in Alzheimer's disease: a randomized controlled study. J Am Geriatr Soc 2008; 56: pp. 2076-2081.

- Cooke J.R., Ayalon L., Palmer B.W., et. al.: Sustained use of CPAP slows deterioration of cognition, sleep, and mood in patients with Alzheimer's disease and obstructive sleep apnea: a preliminary study. J Clin Sleep Med 2009; 5: pp. 305-309.

- Lajoie, A.C.; Lafontaine, A.L.; Kimoff, R.J.; Kaminska, M. Obstructive Sleep Apnea in Neurodegenerative Disorders: Current Evidence in Support of Benefit from Sleep Apnea Treatment. J Clin Med. 2020 Jan 21;9, 297. [CrossRef]

- Djonlagic, I.; Guo, M.; Matteis, P.; Carusona, A.; Stickgold, R.; Malhotra, A. First night of CPAP: impact on memory consolidation attention and subjective experience. Sleep Med. 2015 Jun;16, 697-702. [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, M.; Chiaravalloti, A.; Manfredi, N.; Placidi, F.; Nuccetelli, M.; Izzi, F.; Camedda, R.; Bernardini, S.; Schillaci, O.; Mercuri, N.B.; Liguori, C. Nocturnal Hypoxia and Sleep Fragmentation May Drive Neurodegenerative Processes: The Compared Effects of Obstructive Sleep Apnea Syndrome and Periodic Limb Movement Disorder on Alzheimer's Disease Biomarkers. J Alzheimers Dis. 2022;88, 127-139. [CrossRef]

- Liguori, C.; Mercuri, N.B.; Izzi, F.; Romigi, A.; Cordella, A.; Sancesario, G.; Placidi, F. Obstructive Sleep Apnea is Associated With Early but Possibly Modifiable Alzheimer's Disease Biomarkers Changes. Sleep. 2017 May 1;40(5). [CrossRef]

- Reddy, O.C.; van der Werf, Y.D. The Sleeping Brain: Harnessing the Power of the Glymphatic System through Lifestyle Choices. Brain Sci. 2020 Nov 17;10, 868. [CrossRef]

- Scullin, M.K.; Bliwise, D.L. Is cognitive aging associated with levels of REM sleep or slow wave sleep? Sleep. 2015 Mar 1;38, 335-6. [CrossRef]

- Song Y, Blackwell T, Yaffe K, Ancoli-Israel S, Redline S, Stone KL; Osteoporotic Fractures in Men (MrOS) Study Group. Relationships between sleep stages and changes in cognitive function in older men: the MrOS Sleep Study. Sleep. 2015 Mar 1;38, 411-21. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lo, J.C.; Groeger, J.A.; Cheng, G.H.; Dijk, D.J.; Chee, M.W. Self-reported sleep duration and cognitive performance in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Med. 2016 Jan;17:87-98. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Zhu, H.; Dai, R.; Zhang, T. Associations Between Total Sleep Duration and Cognitive Function Among Middle-Aged and Older Chinese Adults: Does Midday Napping Have an Effect on It? Int J Gen Med. 2022 Feb 10;15:1381-1391. [CrossRef]

- Nelson, K.L.; Davis, J.E.; Corbett, C.F. Sleep quality: An evolutionary concept analysis. Nurs Forum. 2022 Jan;57, 144-151. [CrossRef]

- Barami, K. Cerebral venous overdrainage: an under-recognized complication of cerebrospinal fluid diversion. Neurosurg Focus. 2016 Sep;41, E9. [CrossRef]

- Gleadhill, I.C.; Schwartz, A.R.; Schubert, N.; Wise, R.A.; Permutt, S.; Smith, P.L. Upper airway collapsibility in snorers and in patients with obstructive hypopnea and apnea. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1991 Jun;143, 1300-3. [CrossRef]

- Wellman, A.; Genta, P.R.; Owens, R.L.; Edwards, B.A.; Sands, S.A.; Loring, S.H.; White, D.P.; Jackson, A.C.; Pedersen, O.F.; Butler, J.P. Test of the Starling resistor model in the human upper airway during sleep. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2014 Dec 15;117, 1478-85. [CrossRef]

- Thomas Penzel Marion Möller Heinrich, F. Becker, Lennart Knaack, Jörg-Hermann Peter, Effect of Sleep Position and Sleep Stage on the Collapsibility of the Upper Airways in Patients with Sleep Apnea, Sleep, Volume 24, Issue 1, January 2001, Pages 90–95, . [CrossRef]

- Landry, S.A.; Beatty, C.; Thomson, L.D.J.; Wong, A.M.; Edwards, B.A.; Hamilton, G.S.; Joosten, S.A. A review of supine position related obstructive sleep apnea: Classification, epidemiology, pathogenesis and treatment. Sleep Med Rev. 2023 Dec;72:101847. [CrossRef]

- Kuo, C.D.; Chen, G.Y.; Lo, H.M. Effect of different recumbent positions on spectral indices of autonomic modulation of the heart during the acute phase of myocardial infarction. Crit Care Med. 2000 May;28, 1283-9. [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.L.; Chen, G.Y.; Kuo, C.D. Comparison of effect of 5 recumbent positions on autonomic nervous modulation in patients with coronary artery disease. Circ J. 2008 Jun;72, 902-8. [CrossRef]

- Muppidi, S.; Gupta, P.K.; Vernino, S. Reversible right vagal neuropathy. Neurology. 2011 Oct 18;77, 1577-9. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, K.P.; Brodnick, S.K.; Blanz, S.L.; Zeng, W.; Kegel, J.; Pisaniello, J.A.; Ness, J.P.; Ross, E.; Nicolai, E.N.; Settell, M.L.; Trevathan, J.K.; Poore, S.O.; Suminski, A.J.; Williams, J.C.; Ludwig, K.A. Clinically-derived vagus nerve stimulation enhances cerebrospinal fluid penetrance. Brain Stimul. 2020 Jul-Aug;13, 1024-1030. [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.J.; Lee, H.P.; Kim, M.S.; Park, Y.J.; Go, H.J.; Kim, K.S.; Lee, S.P.; Chae, J.H.; Lee, C.T. The effect of total sleep deprivation on cognitive functions in normal adult male subjects. Int J Neurosci. 2001 Jul;109(1-2):127-37. [CrossRef]

- Pilcher, J.J.; McClelland, L.E.; DeWayne, D.; Henk, M.; Jaclyn, H.; Thomas, B.; Wallsten, S.; McCubbin, J.A. Language performance under sustained work and sleep deprivation conditions. Aviation, Space, and Environmental Medicine. 2007 May 1;78, B25-38.

- Crowley, R.; Alderman, E.; Javadi, A.H.; Tamminen, J. A systematic and meta-analytic review of the impact of sleep restriction on memory formation. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2024 Dec;167:105929. [CrossRef]

- Chua, E.C.; Fang, E.; Gooley, J.J. Effects of total sleep deprivation on divided attention performance. PLoS One. 2017 Nov 22;12, e0187098. [CrossRef]

- Menon, R.N.; Radhakrishnan, A.; Sreedharan, S.E.; Sarma, P.S.; Kumari, R.S.; Kesavadas, C.; Sasi, D.; Lekha, V.S.; Justus, S.; Unnikrishnan, J.P. Do quantified sleep architecture abnormalities underlie cognitive disturbances in amnestic mild cognitive impairment? J Clin Neurosci. 2019 Sep;67:85-92. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).