Introduction

The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM) have defined Long COVID as “an infection-associated chronic condition that occurs after SARS-CoV-2 infection and is present for at least 3 months as a continuous, relapsing and remitting, or progressive disease state that affects one or more organ systems”. Long COVID can present with a variety of symptoms, ranging from mild to severe. It can impact one or more systems, including the immune, cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, respiratory, genitourinary, musculoskeletal, endocrine, neurological systems, and sensory, including taste and smell. Because SARS-CoV-2 continues to mutate or change, researchers have been unable to accurately predict exactly how many individuals have been or are currently affected by Long COVID, but many online databases estimate that 10 percent to 40 percent of patients who contract SARS-CoV-2 progress to symptoms consistent with a diagnosis of Long COVID.

At the onset of COVID-19, given human immunologic naivete to SARS-CoV-2, the innate immune system played a more paramount role than the adaptive immune system in the defense against the virus. Several reports have shown innate immune status as conferred by TAS2R (T2R) phenotype associated with severity of illness including methylation of T2R as a mechanism for gene expression, influencing disease development.1-3 If T2R status is associated with severity of illness with upper respiratory infections, including COVID-19, this is associated with one’s innate immune protection against upper respiratory infections. Severe illness with SARS-CoV-2 infection can be defined in two ways. One is severity of symptoms, including duration, symptom profile, and hospitalization. The second is increased systemic infection with spike protein circulation, increased relative to mild systemic infection. The two typically go together, but don’t necessarily have to, especially now that vaccines, monoclonal antibodies, and additional therapies have been rolled out, influencing the adaptive immune response.

COVID-19 vaccines have been credited by public health officials with the prevention of millions of COVID-19 deaths but have shown decreasing effectiveness with time.4,5 A portion of the population reports a chronic debilitating condition after COVID-19 vaccination, often referred to as post- vaccination syndrome. To explore the potential association between post-vaccination syndrome and Long COVID, we evaluated 100 consecutive patients, both vaccinated and unvaccinated, with symptoms of Long COVID. While Long COVID is defined as an infection-associated chronic condition, we explore the possibility of this condition impacting patients post vaccination. Reports have shown individuals reporting post-vaccination symptoms resembling long COVID, often referred to as post-vaccination syndrome or post-acute COVID-19 vaccination syndrome.6 As expected, post vaccinated individuals should in fact exhibit elevated levels of circulating spike protein, but the concern is whether this ultimately can lead to post-vaccination syndrome with symptoms consistent with Long COVID.

By evaluating immunologic features in patients presenting with symptoms of Long COVID, both vaccinated and unvaccinated, we are able to further evaluate and generate hypotheses surrounding the symptom profile and expectations of disease course. As health practitioners continue to manage patients dealing with the short-term effects of COVID-19, Long COVID, and post-vaccination syndrome, further evaluation into immunologic features will be essential in helping to manage patient expectations and clinical course.

Methods

To investigate the association between post-vaccination syndrome and Long COVID, we performed an observational cohort study at our outpatient clinical practice. We evaluated SARS-CoV-2 Semi-Quant Spike Ab (LabCorp, reference interval: Negative < 0.8 U/ml) results of 100 consecutive patients presenting to Sinus and Nasal Specialists of Louisiana, both vaccinated and unvaccinated, with symptoms of Long COVID, including immunological features and symptom profiles in patients presenting for evaluation of persistent symptoms after COVID-19 infection and vaccination. A total of 81 participants with post-vaccination syndrome who reported no pre-existing comorbidities and 19 unvaccinated participants with no history of SARS-CoV-2 vaccination but with evidence of prior SARS-CoV-2 infection, greater that three months prior to inclusion, with symptoms of Long COVID, as defined by The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.

Exclusions

Participants with evidence of active infection with SARS-CoV-2 confirmed via positive PCR test result at study commencement were excluded. Participants with evidence of prior infection with SARS-CoV-2 or clinical suspicion of infection with SARS-CoV-2 within three months at study commencement were excluded. Participants were excluded from evaluation if they had pharmacological immunosuppression or a diagnosis of immunodeficiency including agammaglobulinemia, common variable immune deficiency, or hypogammaglobulinemia.

Results

The vaccinated cohort consisted of a total of 81 participants (38 (46.9%) female and 43 (53.1%) male) with no preexisting comorbidities. The unvaccinated cohort consisted of 19 participants (9 (47.4%) female and 10 (52.6%) male). The vaccinated cohort reported having a history of one or more previous SARS-CoV-2 infections. Even though all post-vaccination syndrome participants developed chronic symptoms following vaccination and not infection, it is important to consider the impact of a subsequent SARS-CoV-2 infection on results in this study. Individuals in the post-vaccination syndrome cohort completed the primary series of vaccines based on World Health Organization recommendations, up to forty-eight months prior to inclusion. No subjects were included in the analysis if they had pharmacological immunosuppression, immunodeficiency, or history of SARS-CoV-2 infection within three months of evaluation. SARS-CoV-2 vaccination was verified in 81 of the 100 participants.

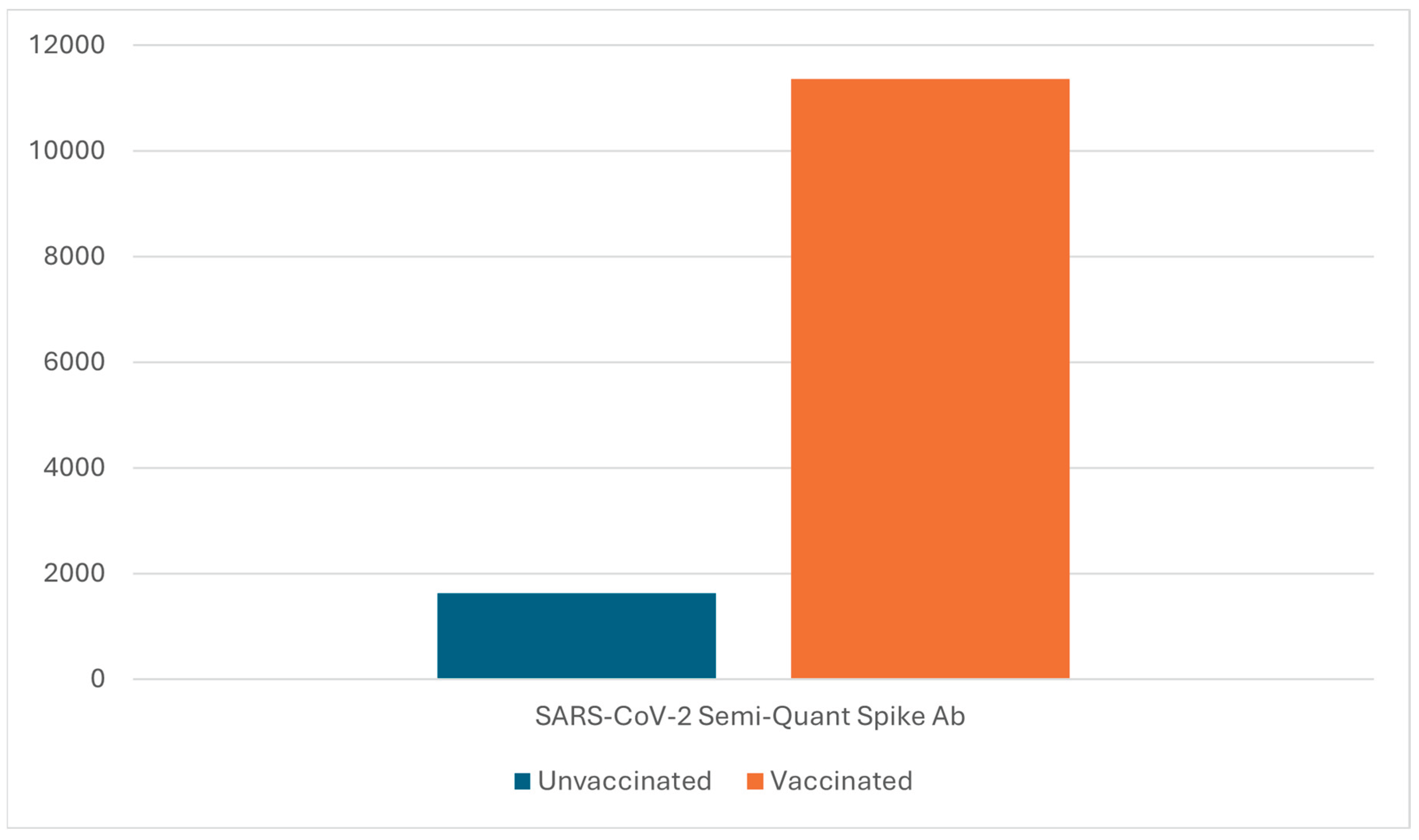

SARS-CoV-2 Semi-Quant Spike Ab in the vaccinated cohort showed an average result of 11356.86 U/ml (range: 1291 U/ml - >25000 U/ml). SARS-CoV-2 Semi-Quant Spike Ab in the unvaccinated cohort showed an average result of 1631.94 U/ml (range: 1.5 U/ml – 4614 U/ml) (

Figure 1).

The most frequent symptoms reported by participants, both vaccinated and unvaccinated, were excessive fatigue (81%), brain fog (76%), headaches (75%), muscle and joint aches (71%), anxiety (54%), sleep irregularity (50%), nasopharyngitis/adenoid hypertrophy with associated aural fullness (40%), tinnitus (38%), gastrointestinal discomfort (34%), numbness and tingling (34%), chest pain/tightness (27%), shortness of breath (21%), lymphadenopathy (14%), diverticulitis (5%).

Discussion

COVID-19 is an infectious disease caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus, which typically presents in infected patients with mild to moderate respiratory illness symptoms. Most patients recover without significant sequela. However, there is a portion of the population, which progresses on to symptoms of Long COVID, defined as “an infection-associated chronic condition that occurs after SARS-CoV-2 infection and is present for at least 3 months as a continuous, relapsing and remitting, or progressive disease state that affects one or more organ systems”. Long COVID can present with a variety of symptoms, impacting multiple organ systems, affecting ten to forty percent of patients previously infected with SARS-CoV-2. Our study findings reveal potential immune differences in both individuals with Long COVID and those with post-vaccination syndrome that merit further investigation to better understand these conditions and inform future research into diagnostic and therapeutic approaches.

Based on the results from this study, we describe our current understanding of Long COVID as increased levels of circulating spike protein with immune system response of antibody production with circulation and deposition of these immune complexes into tissue with resulting associated symptoms. Clinically, we initially observed increased levels of inflammation and associated symptoms in addition to recurring upper respiratory infections with increasing prevalence. We have noted significantly increasing numbers of patients deficient in pneumococcal titers, often with lymphoid hypertrophy/inflammation of the nasopharynx/adenoid. The patient population making up the deficiency seems to be weighted towards the mRNA vaccination group but also did penetrate non-vaccinated with prior SARS-CoV-2 infection group.

One hypothesis for Long COVID is that increased levels of circulating spike protein with deposition, either isolated or with immune complex deposition, into various organ systems causes two things. The first is associated problems related to deposition into organ systems, including pericarditis, myocarditis, headaches, endocrine dysfunction, inflammatory bowel disease, diverticulitis, and Bell’s palsy to name a few. Another hypothesis is that increasing level levels of circulating spike protein also causes immune response with production of antibodies. This is typically an appropriate immune response. The potential problem lies in long-term increased levels of circulation with chronic antibody production, thereby leading to immune fatigue, including pneumococcal antibody deficiencies.

Post-vaccination syndrome could cause long term symptoms by several mechanisms. Vaccine components could lead to chronic inflammation through stimulation of innate immune response via pattern recognition receptors by mRNA, adenoviral vectors, and or nanoparticles.7,8 This vaccine induced immune response could trigger autoreactive lymphocytes.6,9 Spike protein expression following vaccination circulates in the plasma within one day following vaccination and host interaction with full-length Spike protein, subunits, or peptide fragments could results in prolonged symptoms. 6,10,11 Spike protein potential ability to cross the blood-brain barrier could result in neural or cognitive symptoms, based on biodistribution models of mRNA-LNP. 6,12 Another concern is that with chronic increased circulating levels of Spike protein with immune response, in addition to developing immune fatigue, the virus may ultimately become an oncogenic virus with alterations in response of neutrophils, memory cells, T cells and antibodies.

In response to managing this problem, further investigation is needed to better understand these conditions and inform future research into diagnostic and therapeutic approaches. There is limited and conflicting data related to systemically binding the Spike protein involving nattokinase, bromelain, and curcumin.13,14 Another interesting possibility is the interaction between nicotine receptors and viral cell entry. Nicotine binds to nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs), which are distributed throughout the body, including the respiratory tract, which share similarities with ACE2 receptors, which SARS-CoV-2 uses to enter cells of the host.

Limitations

There is selection bias in this study as all patients were referred to an otolaryngology practice for symptoms of sinonasal origin with concerns for Long COVID and did not typically represent all symptoms associated with Long COVID. The results of testing were a snapshot in time of the population and not followed on a set time period following known COVID infection, though were at a minimum, greater than three months post SARS-CoV-2 infection. An additional possibility is that post-vaccination syndrome could result from an asymptomatic COVID infection immediately following the vaccination as up to 40% of COVID infections are reported as asymptomatic,15 leading to inappropriately presumed post-vaccination syndrome.

Conclusions

Long COVID is an infection-associated chronic condition that occurs after SARS-CoV-2 infection and is present for at least 3 months as a continuous, relapsing and remitting, or progressive disease state. While COVID-19 vaccines have been credited by public health officials with the prevention of COVID-19 associated morbidity and mortality, a portion of the population reports post-vaccination syndrome often concerning for Long COVID, based on symptom profile. Our study findings reveal potential immune involvement in both individuals with Long Covid and those with post-vaccination syndrome that merit further investigation to better understand these conditions and inform future research into diagnostic and management approaches.

Declaration of conflicts of interest: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article

References

- Barham HP et al. Association Between Bitter Taste Receptor Phenotype and Clinical Outcomes Among Patients With COVID-19. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(5):e2111410. [CrossRef]

- Barham HP et al. Does phenotypic expression of bitter taste receptor T2R38 show association with COVID-19 severity? Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2020 Nov;10(11):1255-1257. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Melis M et al. TAS2R38 gene methylation is associated with syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection and clinical symptoms. Sci Rep. 2025 Apr 25;15(1):14462. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wu, Nana et al. Long-term effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines against infections, hospitalisations, and mortality in adults: findings from a rapid living systematic evidence synthesis and meta-analysis up to December, 2022. The Lancet Respiratory Medicine, Volume 11, Issue 5, 439 - 452.

- Zheng, C et al. Real-world effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines: a literature review and meta-analysis. Int J Infect Dis 114, 252-260. 10.1016/j.ijid.2021.11.009.

- Bornali B et al. Immunological and Antigenic Signatures Associated with Chronic Illnesses after COVID-19 Vaccination. medRxiv 2025.02.18.25322379. [CrossRef]

- Verbeke R et al. Innate immune mechanisms of mRNA vaccines. Immunity 55, 1993-2005. [CrossRef]

- Appledorn DM et al. Adenovirus vector-induced innate inflammatory mediators, MAPK signaling, as well as adaptive immune responses are dependent upon both TLR2 and TLR9 in vivo. J Immunol 181, 2134-2144. [CrossRef]

- Segal Y and Shoenfeld Y. Vaccine-induced autoimmunity: the role of molecular mimicry and immune crossreaction. Cell Mol Immunol 15, 586-594. [CrossRef]

- Ogata AF et al. Circulating Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) Vaccine Antigen Detected in the Plasma of mRNA-1273 Vaccine Recipients. Clin Infect Dis 74, 715-718. [CrossRef]

- Cognetti JS et al. Monitoring Serum Spike Protein with Disposable Photonic Biosensors Following SARS-CoV-2 Vaccination. Sensors (Basel) 21. [CrossRef]

- Theoharides TC. Could SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein Be Responsible for Long COVID Syndrome? Mol Neurobiol 59, 1850-1861. [CrossRef]

- Tanikawa T et al. Degradative Effect of Nattokinase on Spike Protein of SARS-CoV-2. Molecules. 2022 Aug 24;27(17):5405. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hulscher N et al. Clinical Approach to Post-acute Sequelae After COVID-19 Infection and Vaccination. Cureus. 15. [CrossRef]

- Ma, Q et al. Global Percentage of Asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 Infections Among the Tested Population and Individuals With Confirmed COVID-19 Diagnosis: A Systematic Review and Meta analysis. JAMA Netw Open 4, e2137257. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).