Submitted:

14 July 2025

Posted:

16 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Literature Review and Keywords

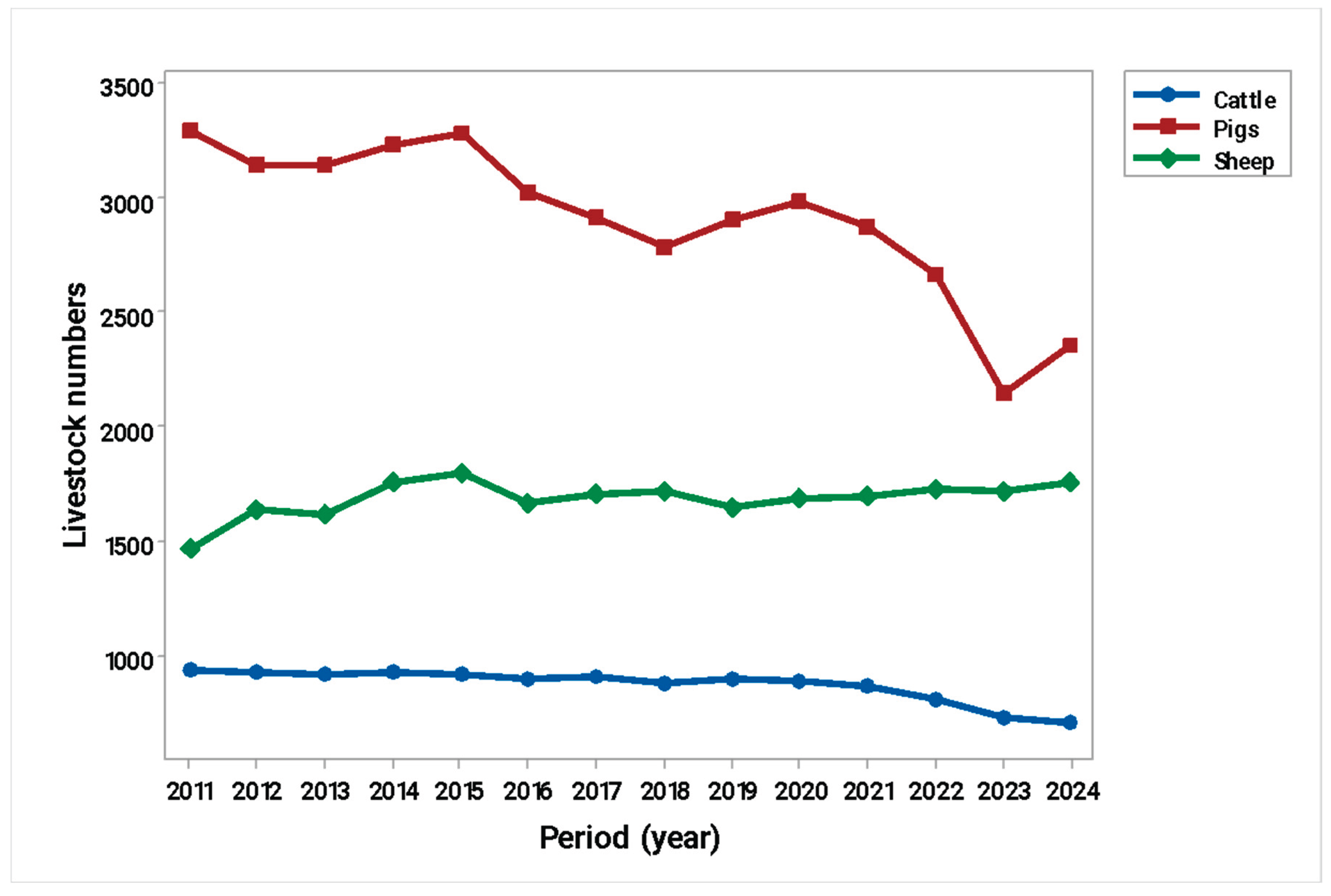

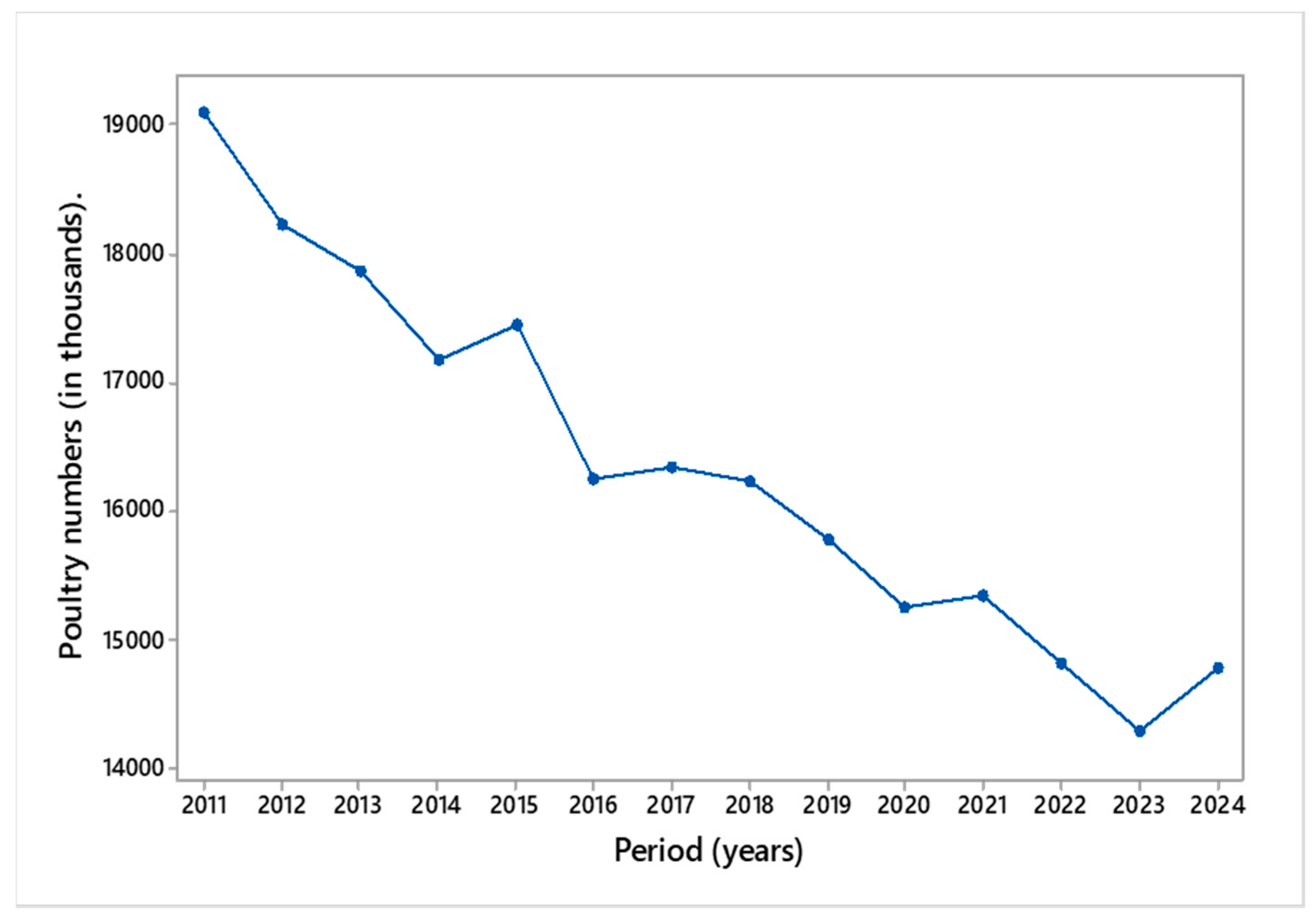

3. Present Situation in Livestock Production in Serbia

3.1. Global Factors

3.1. Domestic Factors

3.3. Economic Accounts for Agriculture in Serbia

- Strategic and structural factors

- Technological factors

- Economic and financial factors

- Market organization and branding

- Biosecurity and animal health

- Climate and environmental factors

- Demographic factors

3.4. Strategic Recommendations for Sustainable Livestock Competitiveness

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Adesogan, A. T., Gebremikael, M. B., Varijakshapanicker, P., & Vyas, D. (2025). Climate-smart approaches for enhancing livestock productivity, human nutrition, and livelihoods in low-and middle-income countries. Animal Production Science, 65(6).https://doi.org/10.1071/AN24215.

- Akinsulie, O. C., Idris, I., Aliyu, V. A., Shahzad, S., Banwo, O. G., Ogunleye, S. C., ... & Soetan, K. O. (2024). The potential application of artificial intelligence in veterinary clinical practice and biomedical research. Frontiers in Veterinary Science, 11, 1347550. https://doi.org/10.3389/fvets.2024.1347550.

- Ali, A. A. (2023). Artificial intelligence and its application in the prediction and diagnosis of animal diseases: A review. Indian Journal of Animal Research, 57(10), 1265-1271. https://doi.org/10.18805/IJAR.BF-1684.

- Andjelković T., Janković-Milić V., Lepojević V., Jovanović S. 2024. Comparative analysis of Serbian agriculture and agriculture of other high middle-income countries. Ekonomika poljoprivrede, 71(3), 787-801. https://doi.org/10.59267/ekoPolj2403787A.

- Aničić D., Nestorović O., Aničić J., Jovanović Z. 2025. Trends and perspectives of agricultural development in Serbia. Ekonomika poljoprivrede, 72(1), 375-385. https://doi.org/10.59267/ekoPolj2501375a.

- Bešić C., Ćoćkalo D., Bakator M., Stanisavljev S., Bogetić S. 2024. Society 5.0 and its impact on agricultural business and innovation: A new paradigm for rural development. Ekonomika poljoprivrede, 71(3), 803-819. https://doi.org/10.59267/ekoPolj2403803B.

- Bošković J., Popović V., Mladenović J., Stevanović A., Ristić V., Maksin M., Jovanov D. 2023. The future of smart agricultural production through applied information technologies. In Book of Proceedings, IRASA International Scientific Conference Science, Education, Technology and Innovation (SETI V 2023), 14 October 2023, Belgrade, 3-35. Belgrade: International Research Academy of Science and Art (IRASA). https://hdl.handle.net/21.15107/rcub_fiver_4074.

- Çakmakçı, R., Salık, M. A., & Çakmakçı, S. (2023). Assessment and principles of environmentally sustainable food and agriculture systems. Agriculture, 13(5), 1073.https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture13051073.

- Đurić K., Cvijanović D., Prodanović R., Čavlin M., Kuzman B., Lukač Bulatović M. 2019. Serbian agriculture policy: Economic analysis using the PSE approach. Sustainability, 11(2), 309. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11020309.

- EC (2024), EU agricultural outlook, 2024-2035. European Commission, DG Agriculture and Rural Development, Brussels.https://agriculture.ec.europa.eu/data-and-analysis/markets/outlook/medium-term_en.

- EC (2024), Monitoring EU agri-food trade. European Commission, DG Agriculture and Rural Development, Brussels.Available: https://agriculture.ec.europa.eu/international/agricultural-trade/trade-and-international-policy-analysis_en.

- EUROSTAT. 2025. Agricultural statistics – livestock production. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat.

- FAO. (2024). FAOSTAT: Livestock primary production data. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Retrieved July 5, 2025, from https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data.

- FAO. 2018a. The future of food and agriculture – Alternative pathways to 2050. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. https://www.fao.org/3/i8429en/i8429en.pdf.

- FAO. 2018b. World Livestock: Transforming the livestock sector through the Sustainable Development Goals. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. https://www.fao.org/3/CA1201EN/ca1201en.pdf.

- FAO. 2022. The State of Food and Agriculture 2022. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. https://doi.org/10.4060/cc0639en.

- Goller, M., Caruso, C., & Harteis, C. (2021). Digitalisation in Agriculture: Knowledge and Learning Requirements of German Dairy Farmers. International Journal for Research in Vocational Education and Training, 8(2), 208–223. https://doi.org/10.13152/IJRVET.8.2.4.

- Grujić Vučkovski B., Paraušić V., Jovanović Todorović M., Joksimović M., Marina I. 2022. Analysis of influence of value indicators agricultural production on gross value added in Serbian agriculture. Custos e Agronegocio, 18(4), 349-372. http://www.custoseagronegocioonline.com.br/.

- Hossein-Zadeh, N. G. (2025). Artificial intelligence in veterinary and animal science: applications, challenges, and future prospects. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture, 235, 110395.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compag.2025.110395.

- International Monetary Fund (IMF). 2025. Republic of Serbia: Staff Report and Macroeconomic Indicators. https://www.imf.org.

- International Trade Centre (ITC). 2025. Trade Map: International Trade Statistics. https://www.trademap.org.

- Katsini, L., López, C. A. M., Bhonsale, S., Roufou, S., Griffin, S., Valdramidis, V., ... & Van Impe, J. (2024). Modeling climatic effects on milk production. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture, 225, 109218. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compag.2024.109218.

- Kovačević, V., Vidojević5, D., Strićević, R., Vimić, A. V., & Bogdanović, V. (2024). 6. Adaptation to climate change in agriculture–status, gaps and recommendations in Serbia. CLIMATE CHANGE ADAPTATION IN AGRICULTURE–STATUS AND PROSPECTS IN WESTERN, 271.

- Langemeier, M. “Measuring Farm Profitability.” farmdoc daily (6):63, Department of Agricultural and Consumer Economics, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, April 1, 2016.http://farmdocdaily.illinois.edu/2016/04/measuring-farm-profitability.html.

- Madžar, L. (2014). Značaj i izvozni potencijal privrede Republike Srbije sa posebnim osvrtom na stanje stočnog fonda. Škola biznisa, 2, 124-140. https://doi.org/10.5937/skolbiz2-7107.

- Marković M., Simonović Z. 2025. Competitiveness of the agri-food sector of Serbia through the perspective of unit values of exports and imports. Ekonomika Poljoprivrede, 72(2), 469-481. https://doi.org/10.59267/ekoPolj2502469M.

- Milić, D. M., Glavaš Trbić, D. B., Tomaš Simin, M. J., Zekić, V. N., Novaković, T. J., & Vukelić, N. B. (2020). Ekonomski pokazatelji proizvodnje polutvrdog i tvrdog sira u mlekarama malog kapaciteta u Srbiji. Journal of Agricultural Sciences (Belgrade), 65(3), 283-296. https://doi.org/10.2298/JAS2003283M.

- Milićević D. 2025. Foreign exchange rate and inflation as factors of movements in imports of agricultural and food products in the period 2006-2024. http://www.makroekonomija.org.

- Mukhamedova, Karina R., Natalya P. Cherepkova, Alexandr V. Korotkov, Zhanerke B. Dagasheva, and Manuela Tvaronavičienė. 2022. "Digitalisation of Agricultural Production for Precision Farming: A Case Study" Sustainability 14, no. 22: 14802. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142214802.

- Munz, J., Gindele, N., & Doluschitz, R. (2020). Exploring the characteristics and utilisation of Farm Management Information Systems (FMIS) in Germany. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture, 170, 105246. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compag.2020.105246.

- National Bank of Serbia (NBS). 2025. Macroeconomic indicators. https://www.nbs.rs.

- Novaković D., Milić D., Tomaš Simin M., Jocic B., Novaković T. 2025. Factors influencing the profitability of SMEs from the Republic of Serbia: Food industry. Ekonomika Poljoprivrede, 72(2), 409-423. https://doi.org/10.59267/ekoPolj2502409N.

- Ocran, J.N. (2025). Livestock and poultry production in the age of artificial intelligence (AI): Transforming the livestock and poultry sector through modern innovation. International Journal of Applied Research, 11(3), 112-115. https://doi.org/10.22271/allresearch.2025.v11.i3b.12403.

- Özentürk, U., Chen, Z., Jamone, L., & Versace, E. (2024). Robotics for poultry farming: Challenges and opportunities. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture, 226, 109411. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compag.2024.109411.

- Petrović M.P., Petrović M.M., Pantelić V., Caro Petrović V., Ružić-Muslić D., Selionova M.I., Maksimović N. 2015. Trend and current situation in animal husbandry of Serbia. In Proceedings of the 4th International Congress "New Perspectives and Challenges of Sustainable Livestock Production", Belgrade, Serbia, October 7-9, 2015, 1-7. Institute for Animal Husbandry, Belgrade-Zemun. https://r.istocar.bg.ac.rs/handle/123456789/692.

- Radišić R., Sredojević Z., Perišić P. 2021. Some economic indicators of production of cow’s milk in the Republic of Serbia. Ekonomika poljoprivrede, 68(1), 113-126. https://doi.org/10.5937/ekopolj2101113R.

- Radović Č., Petrović M., Gogić M., Radojković D., Živković V., Stojiljković N., Savić R. 2019. Autochthonous breeds of Republic of Serbia and valuation in food industry: Opportunities and challenges. Food Processing. https://doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.88900.

- Radović G., Subić J., Pejanović V. 2024. Analysis of implementation of the IPARD II program in Serbia. Ekonomika Poljoprivrede, 71(3), 1017-1031. https://doi.org/10.59267/ekoPolj24031017R.

- Schwering, D. S., Bergmann, L., & Sonntag, W. I. (2022). How to encourage farmers to digitize? A study on user typologies and motivations of farm management information systems. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture, 199, 107133.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compag.2022.107133.

- SORS. 2025. Statistical Yearbook of the Republic of Serbia 2025. Belgrade: Statistical Office of the Republic of Serbia. https://www.stat.gov.rs/en-US/.

- Stanković B., Bugarski D., Ninković M., Kureljušić B., Kjosevski M., Chantziaras I. 2024. Implementation of biosecurity measures in ruminants farms. In Proceedings of the 26th International Congress of the Mediterranean Federation for Health and Production of Ruminants (FeMeSPRum), Novi Sad, Serbia, 274-286. https://doi.org/10.5937/FeMeSPRumNS24033S.

- Statistical Office of the Republic of Serbia (SORS). 2025a. Statistical Yearbook of the Republic of Serbia 2025. Belgrade: Statistical Office of the Republic of Serbia. https://www.stat.gov.rs/en-US/.

- Statistical Office of the Republic of Serbia (SORS). 2025b. National accounts – Economic Accounts for Agriculture. https://www.stat.gov.rs/en-US/oblasti/nacionalni-racuni.

- Tolimir, N., Maslovarić, M., Jovanović, R., Tomić, V., Popović, N., Stanimirović, I., & Beskorovajni, R. (2025). Transfer naučnih znanja kroz programe obuke savetodavaca u oblasti stočarstva. Biotechnology in Animal Husbandry, 41(1), 89-100. https://doi.org/10.2298/BAH2501089T.

- United Nations, European Commission, International Monetary Fund, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, World Bank. 2009. System of National Accounts 2008. New York: United Nations. https://unstats.un.org/unsd/nationalaccount/docs/SNA2008.pdf.

- Velten, S., Leventon, J., Jager, N., & Newig, J. (2015). What is sustainable agriculture? A systematic review. Sustainability, 7(6), 7833-7865. https://doi.org/10.3390/su7067833.

- Verdouw, C., Sundmaeker, H., Tekinerdogan, B., Conzon, D., & Montanaro, T. (2019). Architecture framework of IoT-based food and farm systems: A multiple case study. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture, 165, 104939.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compag.2019.104939.

- Vlaicu, P.A., Gras, M.A., Untea, A.E., Lefter, N.A., Rotar, M.C. (2024). Advancing Livestock Technology: Intelligent Systemization for Enhanced Productivity, Welfare, and Sustainability. AgriEngineering, 6, 1479–1496. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriengineering6020084.

- Vukoje V., Miljatović A., Tekić D. 2022. Factors influencing farm profitability in the Republic of Serbia. Ekonomika poljoprivrede, 69(4), 1031-1042. https://doi.org/10.5937/ekoPolj2204031V.

- Wolfert, S., Ge, L., Verdouw, C., & Bogaardt, M.-J. (2017). Big Data in Smart Farming – A review. Agricultural Systems, 153, 69–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agsy.2017.01.023.

- Zhang, L., Guo, W., Lv, C., Guo, M., Yang, M., Fu, Q., & Liu, X. (2024). Advancements in artificial intelligence technology for improving animal welfare: Current applications and research progress. Animal Research and One Health, 2(1), 93-109. https://doi.org/10.1002/aro2.44.

- Županić F.Ž., Radić D., Podbregar I. 2021. Climate change and agriculture management: Western Balkan region analysis. Energy, Sustainability and Society, 11(1), 51. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13705-021-00327-z.

| Period | Beef | Pork | Lamb | Chicken | Beef | Pork | Lamb | Chicken | N | Beef | Pork | Lamb | Chicken |

| Meat production in tons | Consumption per household in kg | Total consumption in tons | |||||||||||

| 2013 | 35574 | 131942 | 936 | 56678 | 10,9 | 47,8 | 2,0 | 46,9 | 2465799 | 26877 | 117865 | 4932 | 115646 |

| 2014 | 36844 | 150294 | 1296 | 62847 | 12,4 | 50,5 | 2,7 | 46,8 | 2466316 | 30582 | 124549 | 6659 | 115424 |

| 2015 | 40014 | 166350 | 1260 | 66876 | 13,9 | 46,4 | 2,5 | 47,2 | 2466316 | 34282 | 114437 | 6166 | 116410 |

| 2016 | 42160 | 163688 | 1404 | 70550 | 14,4 | 46,0 | 2,4 | 47,5 | 2466316 | 35515 | 113451 | 5919 | 117150 |

| 2017 | 45034 | 155925 | 1768 | 86139 | 13,9 | 45,4 | 2,3 | 50,0 | 2466316 | 34282 | 111971 | 5673 | 123316 |

| 2018 | 44461 | 170709 | 2006 | 93245 | 16,2 | 47,2 | 6,2 | 48,6 | 2466316 | 39954 | 116410 | 15291 | 119863 |

| 2019 | 46537 | 173082 | 2312 | 101662 | 16,8 | 49,6 | 6,5 | 50,2 | 2466316 | 41434 | 122239 | 16031 | 123809 |

| 2020 | 47300 | 169728 | 2465 | 100409 | |||||||||

| 2021 | 48327 | 168630 | 3723 | 100405 | 21,3 | 49,9 | 12,0 | 47,2 | 2466316 | 52533 | 123069 | 29596 | 116410 |

| 2022 | 43952 | 139524 | 3893 | 115328 | 20,0 | 46,0 | 9,6 | 47,3 | 2466316 | 49326 | 113451 | 23677 | 116657 |

| 2023 | 43040 | 136752 | 3468 | 124609 | 19,8 | 47,5 | 8,5 | 48,4 | 2466316 | 48833 | 117150 | 20964 | 119370 |

| 2024 | 45592 | 140067 | 3179 | 137228 | |||||||||

| Period | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 |

| Current prices in millions of dinars | |||||||||||

| Output | 599,638 | 624425 | 584834 | 643686 | 590707 | 640862 | 653184 | 700488 | 785423 | 918689 | 842083 |

| IC | 349334 | 367327 | 344056 | 371854 | 336109 | 366069 | 377541 | 399919 | 437684 | 514034 | 490408 |

| GVA | 250304 | 257098 | 240778 | 271832 | 254598 | 274793 | 275642 | 300570 | 347739 | 404655 | 351675 |

| FI | 225787 | 236171 | 217348 | 243416 | 228284 | 246111 | 246158 | 267437 | 299920 | 357482 | 333868 |

| EEA (%) | 6,50 | 6,60 | 5,60 | 6,00 | 5,40 | 5,40 | 5,40 | 5,50 | 5,50 | 5,70 | 4,00 |

| Output | 389186 | 398499 | 367717 | 398347 | 354914 | 377498 | 377582 | 399731 | 415383 | 422123 | 359594 |

| IC | 226730 | 234423 | 216327 | 230123 | 201944 | 215632 | 218243 | 228212 | 231476 | 236190 | 209419 |

| GVA | 162456 | 164076 | 151391 | 168224 | 152970 | 161866 | 159339 | 171519 | 183907 | 185932 | 150175 |

| FI | 146544 | 150721 | 136681 | 150639 | 137160 | 144971 | 142295 | 152612 | 158617 | 164257 | 142572 |

| Strengths | Weaknesses |

| Existing capacities in the dairy and meat sectors with long-standing tradition and expertise. Favourable geographic and agro-climatic conditions for livestock production. Potential for integration into EU value chains. Presence of indigenous breeds suitable for Geographical Indications (GI) and traditional branding. |

Highly fragmented farm structure with economically non-viable smallholdings. Low productivity, e.g. average milk yield per cow of 3,500–4,500 L/year vs. >7,000 L in the EU. Outdated housing systems and insufficient technological modernisation. Limited adoption of Precision Livestock Farming technologies, AI, IoT, and robotics. Weak market organisation with few producer groups and clusters. Lack of a dedicated livestock development strategy aligned with EU CAP Strategic Plans and the Green Deal. Insufficient implementation of biosecurity and animal welfare standards. |

| Opportunities | Threats |

| Alignment with EU Farm to Fork Strategy, Green Deal, and CAP Strategic Plans. Potential for harmonization with EU CAP green architecture (eco-schemes, environmental conditionality) could facilitate access to future funding and enhance farm sustainability. Utilisation of IPARD and other EU funds for farm modernisation and digital transformation. Development of GI-certified and traditionally branded products for domestic and export markets. Implementation of AI, IoT, precision feeding, and robotics to increase productivity and sustainability. Growing demand for high-quality animal products within the EU and regional markets. |

Ongoing rural depopulation and an ageing farming population reducing available labour and innovation capacity. Climate change impacts, including droughts and heat stress, reducing forage yields and pasture productivity. Geopolitical and macroeconomic instabilities affecting feed costs, exchange rates, and market competitiveness. Increased risk of transboundary animal diseases (e.g. African Swine Fever, Avian Influenza) with insufficient biosecurity. Rising imports of cheaper animal products due to real appreciation of the dinar. Lack of adaptation to EU sustainability standards and delayed digital transformation may widen the competitiveness gap with EU livestock sectors. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).