Submitted:

14 July 2025

Posted:

16 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Extension Distance

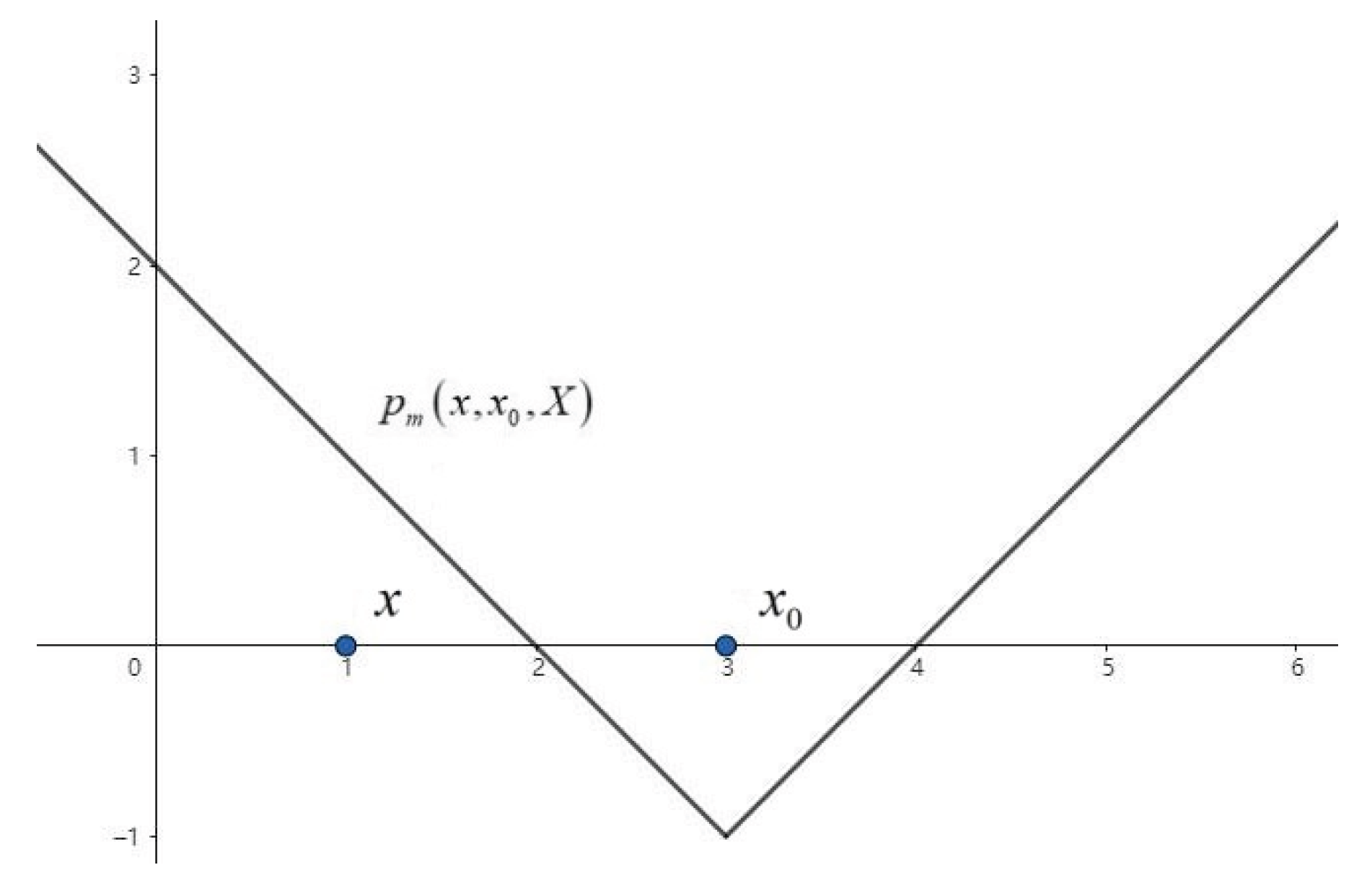

2.1. One-Dimensional Extension Distance

2.2. Limitation in High Dimensions

3. Extension Distance in Two-Dimensional Space

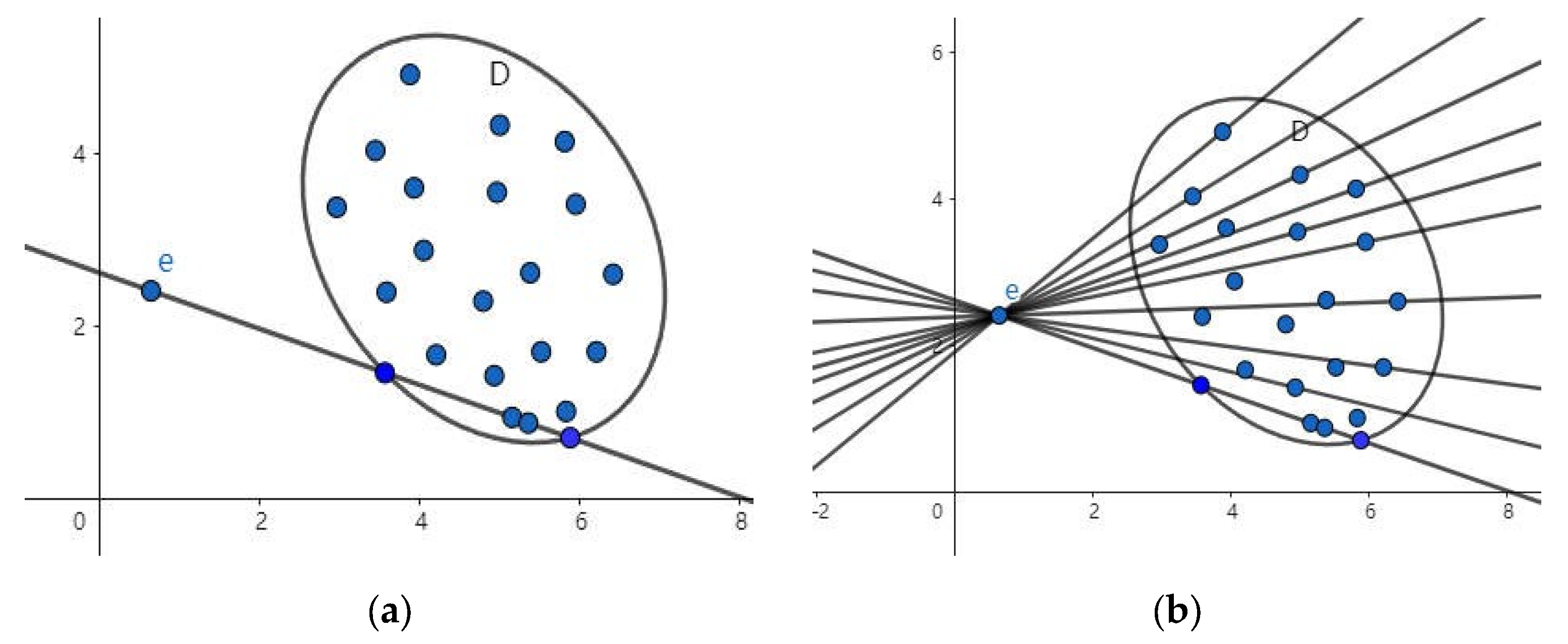

3.1. Straight Line Traversal Method

3.2. Properties and Verification

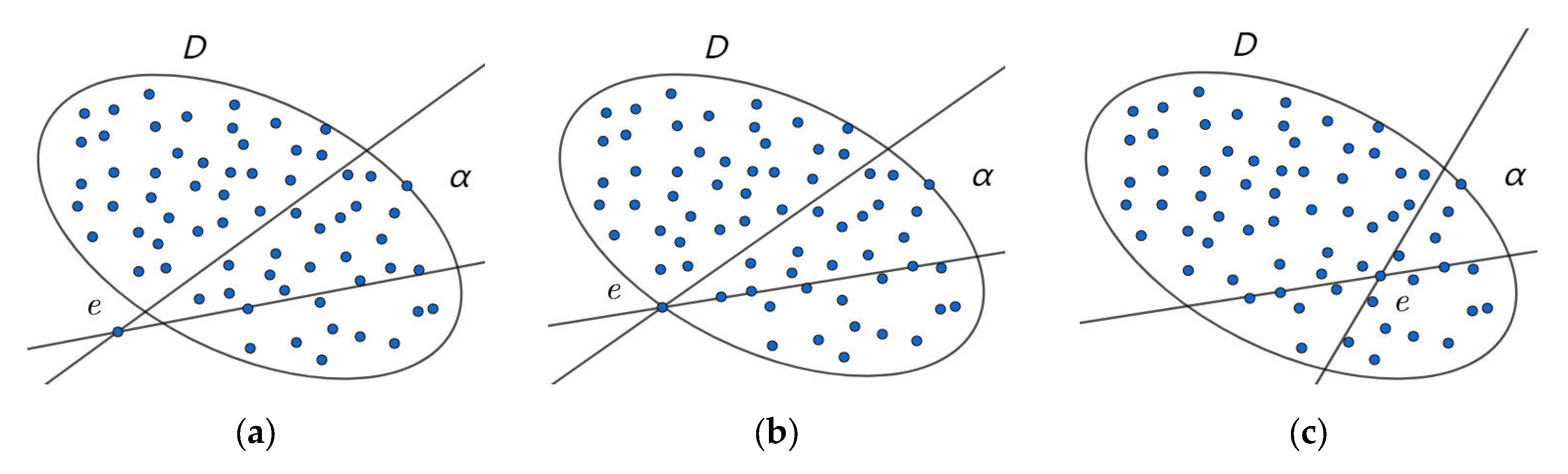

- In the event of point e lying outside set D, for any line passing through the set such that and is satisfied, it follows that for any of the above lines, and are greater than 0. Consequently, is greater than 0.The following essay will provide a comprehensive overview of the relevant literature on the subject.

- When point e is on the boundary of set D,for any line passing through the set, or ,then for any of the above lines, and are both equal to 0,so is equal to 0.

- In the event of point e being in set D,for any line passing through the set such that and ,it can be concluded that is less than 0.

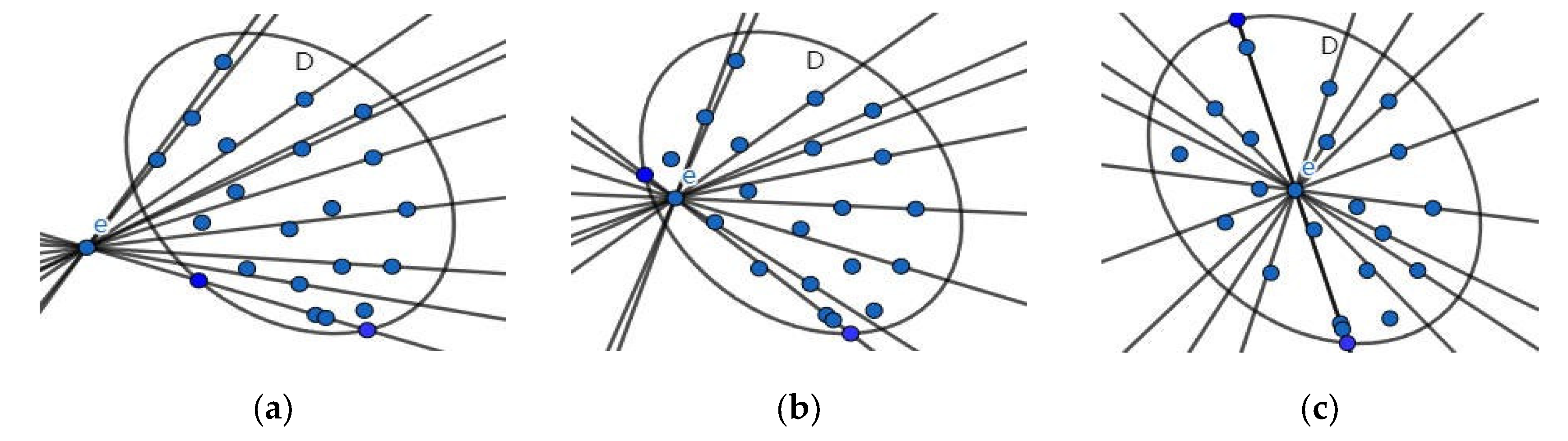

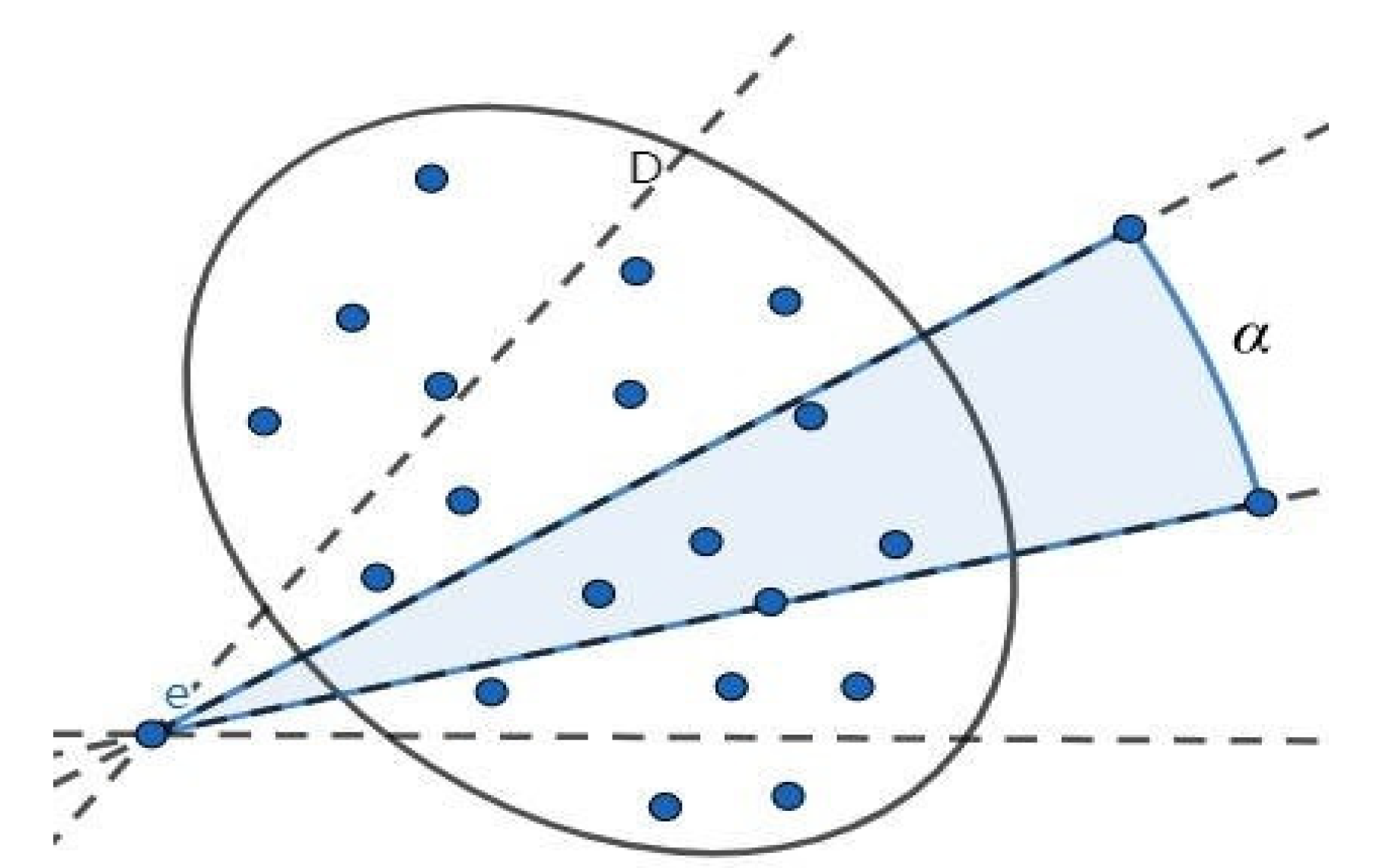

3.3. Fixed-Angle Traversal Method

3.4. Verification and Set Intersection

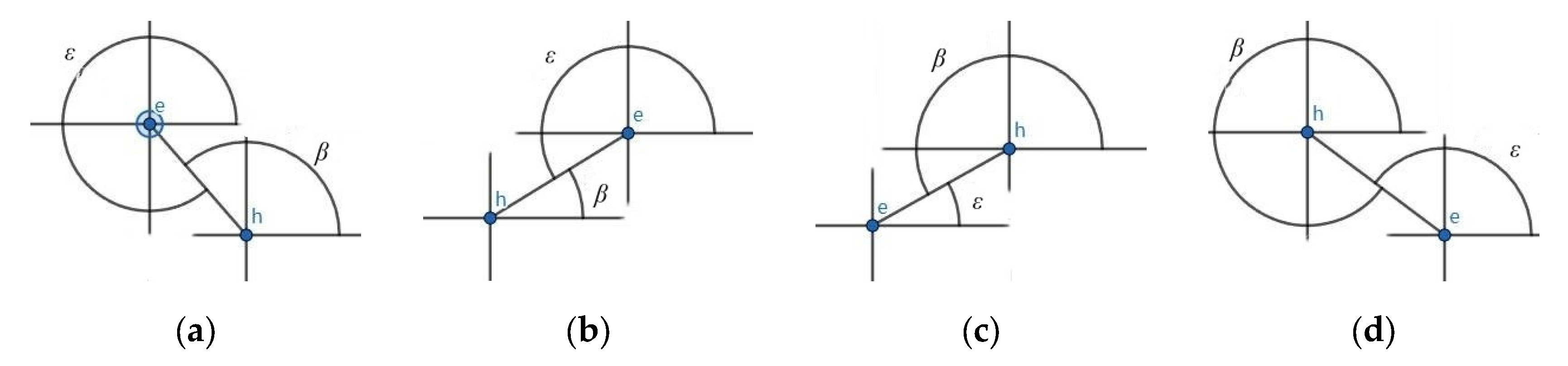

- In Scenario 1, only one point belongs to the set within the fan-shaped range. Furthermore, interval is a single point and , so we have:

- In Scenario 2: There are two or more points in the sector belonging to set and none of the sector boundaries are vertical or horizontal. According to Figure 1, we know that, for the interval so .

- In Scenario 3: There are two or more points within the sector belonging to set and a horizontal or vertical sector edge. In this case, projecting the obtained points onto the or y axis results in a single point rather than an interval, so or .According to Equation (3), analyzing the case where gives us:.

4. Kmeans Variant Based on Extension Distance

4.1. Limitations of Standard K-Means

4.2. Proposed Algorithm Framework

4.3. Angle Relation Matrix

5. Algorithm Comparison Experiment

5.1. Evaluation Metrics

5.2. Datasets and Experimental Setup

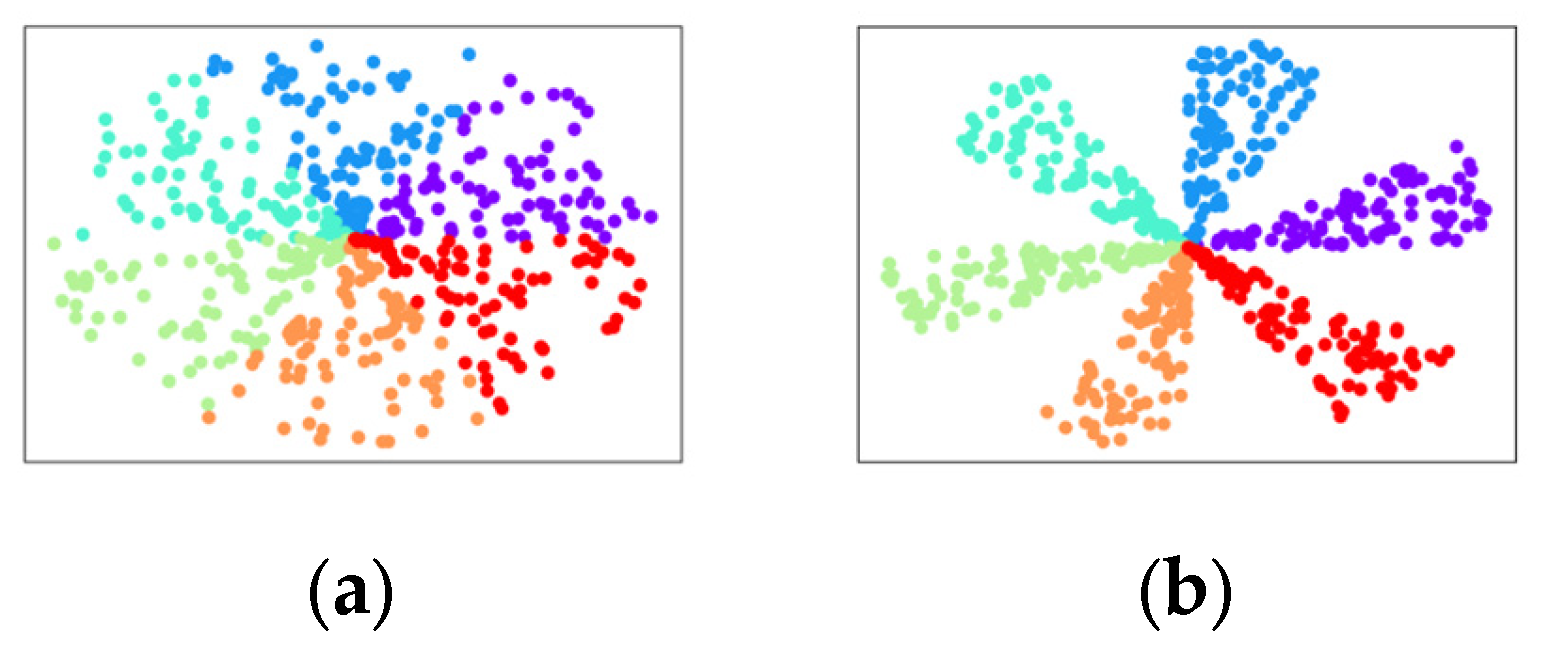

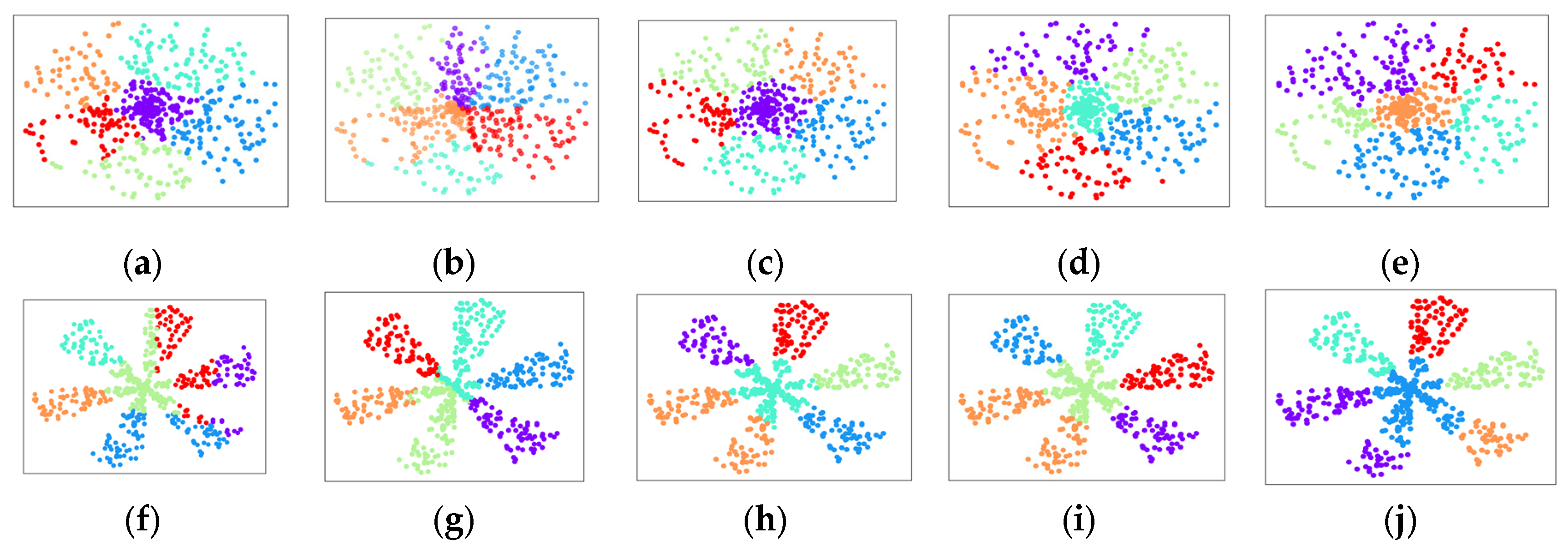

5.3. Clustering Results Visualization

5.4. Quantitative Results Analysis

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

- The proposed algorithm significantly outperforms conventional methods (e.g., K-means++, GMM) in external metrics such as ARI and NMI, highlighting its robustness for fan-shaped distributions.

- The two-dimensional extension distance framework effectively handles inter-feature correlations, overcoming the high-dimensional limitations of one-dimensional approaches.

Institutional Review Board Statement

References

- Yuan, C.; Yang, H. Research on K-value selection method of K-means clustering algorithm. J 2019, 2, 226–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, C.C.; Hinneburg, A.; Keim, D.A. On the surprising behavior of distance metrics in high dimensional space. In Proceedings of the International conference on database theory. Springer; 2001; pp. 420–434. [Google Scholar]

- Von Luxburg, U. A tutorial on spectral clustering. Statistics and computing 2007, 17, 395–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, C.; He, X. K-means clustering via principal component analysis. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the twenty-first international conference on Machine learning, 2004, p. 29.

- Xu, Q.; Ding, C.; Liu, J.; Luo, B. PCA-guided search for K-means. Pattern Recognition Letters 2015, 54, 50–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, D.; Schmidt, M.; Sohler, C. Turning big data into tiny data: Constant-size coresets for k-means, pca, and projective clustering. SIAM Journal on Computing 2020, 49, 601–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suwanda, R.; Syahputra, Z.; Zamzami, E.M. Analysis of euclidean distance and manhattan distance in the K-means algorithm for variations number of centroid K. In Proceedings of the Journal of Physics: Conference Series. IOP Publishing, Vol. 1566; 2020; p. 012058. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Z.; Song, T.; Zhang, Y. Quantum k-means algorithm based on Manhattan distance. Quantum Information Processing 2022, 21, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Yadav, A.; Rana, A. K-means with Three different Distance Metrics. International Journal of Computer Applications 2013, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faisal, M.; Zamzami, E.; et al. Comparative analysis of inter-centroid K-Means performance using euclidean distance, Canberra distance and manhattan distance. In Proceedings of the Journal of Physics: Conference Series. IOP Publishing, Vol. 1566, 012112. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.; Roe, D.R.; Kochert, M.; Simmerling, C.; Miranda-Quintana, R.A. k-Means NANI: an improved clustering algorithm for Molecular Dynamics simulations. Journal of chemical theory and computation 2024, 20, 5583–5597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Premkumar, M.; Sinha, G.; Ramasamy, M.D.; Sahu, S.; Subramanyam, C.B.; Sowmya, R.; Abualigah, L.; Derebew, B. Augmented weighted K-means grey wolf optimizer: An enhanced metaheuristic algorithm for data clustering problems. Scientific reports 2024, 14, 5434. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, W.; Peng, Y.; Ge, Y.; Kong, W. A new Kmeans clustering model and its generalization achieved by joint spectral embedding and rotation. PeerJ Computer Science 2021, 7, 450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, W. Extension theory and its application. Chinese science bulletin 1999, 44, 1538–1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.; Li, X. A method for calculating two-dimensional spatially extension distances and its clustering algorithm. Procedia Computer Science 2023, 221, 1187–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd, S. Least squares quantization in PCM. IEEE transactions on information theory 1982, 28, 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Zhu, F.; Gui, F.; Ren, S.; Xie, Z.; Xu, C. Improved k-means algorithm based on extension distance. CAAI transactions on intelligent systems 2020, 15, 344–351. 425. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, D.L.; Bouldin, D.W. A cluster separation measure. IEEE transactions on pattern analysis and machine intelligence 1979, pp. 224–227.

- Rousseeuw, P.J. Silhouettes: a graphical aid to the interpretation and validation of cluster analysis. Journal of computational and applied mathematics 1987, 20, 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubert, L.; Arabie, P. Comparing partitions. Journal of classification 1985, 2, 193–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strehl, A.; Ghosh, J. Cluster ensembles—a knowledge reuse framework for combining multiple partitions. Journal of machine learning research 2002, 3, 583–617. [Google Scholar]

| The positionalrelationship betweenpoints and intervals or set | Extension distancebetween point andinterval | Extension distancebetween point andtwo-dimensional plane set |

|---|---|---|

| Point outside the interval or set |

||

| Point on the edge of the interval or set |

||

| Point inside the interval or set |

| Algorithm | ARI | NMI | SilhouetteScore | DBI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Algorithm before Improvement |

0.304 | 0.480 | 0.329 | 0.904 |

| This article’s algorithm |

0.480 | 0.597 | 0.259 | 0.974 |

| Kmeans++ | 0.289 | 0.485 | 0.388 | 0.794 |

| GMM | 0.383 | 0.526 | 0.346 | 0.860 |

| Agglomerative | 0.305 | 0.478 | 0.330 | 0.854 |

| Algorithm | ARI | NMI | SilhouetteScore | DBI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Algorithm before Improvement |

0.328 | 0.529 | 0.354 | 0.855 |

| This article’s algorithm |

0.658 | 0.736 | 0.367 | 0.927 |

| Kmeans++ | 0.378 | 0.604 | 0.473 | 0.732 |

| GMM | 0.389 | 0.610 | 0.471 | 0.732 |

| Agglomerative | 0.395 | 0.617 | 0.453 | 0.760 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).