Submitted:

14 July 2025

Posted:

16 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

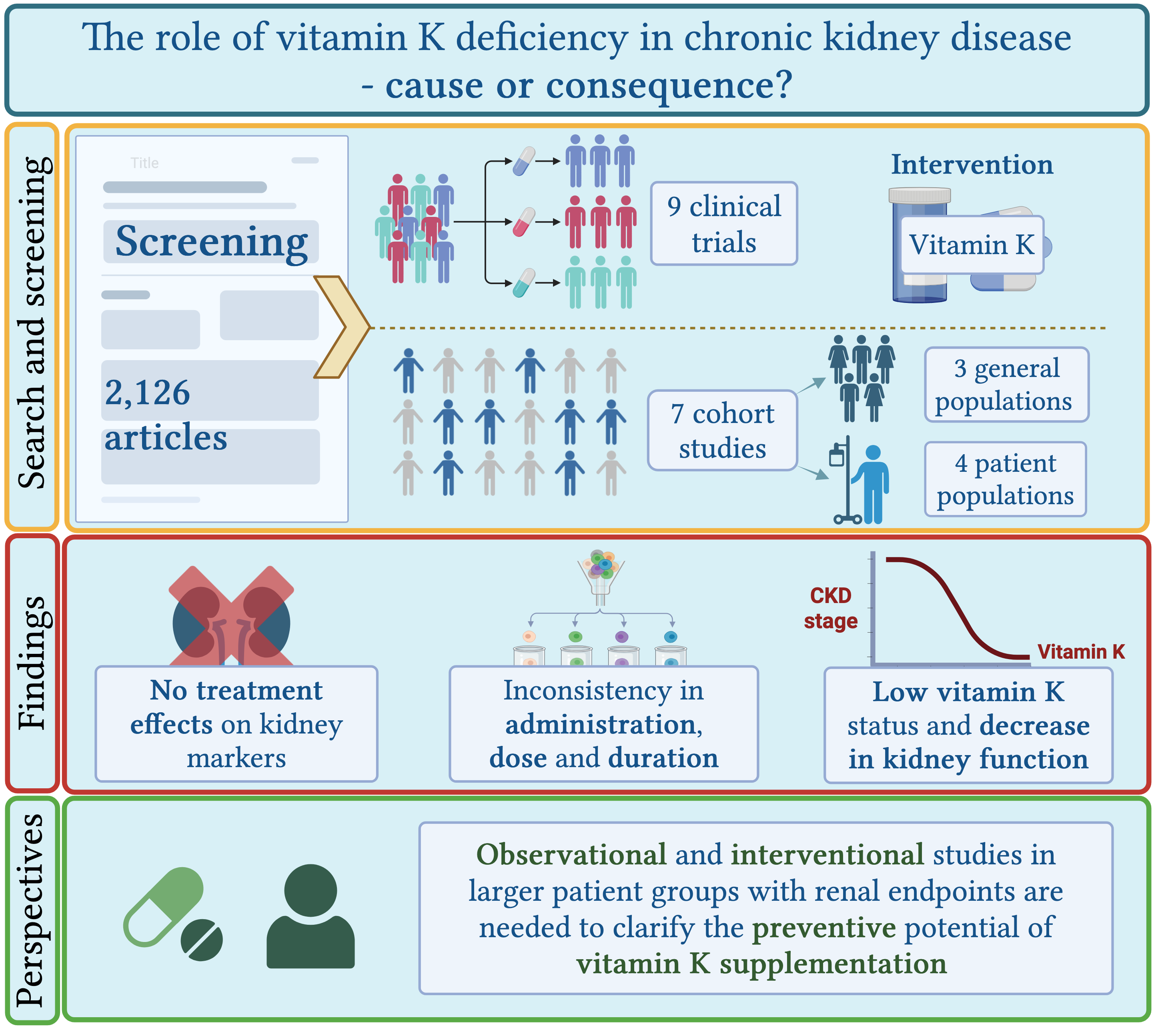

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

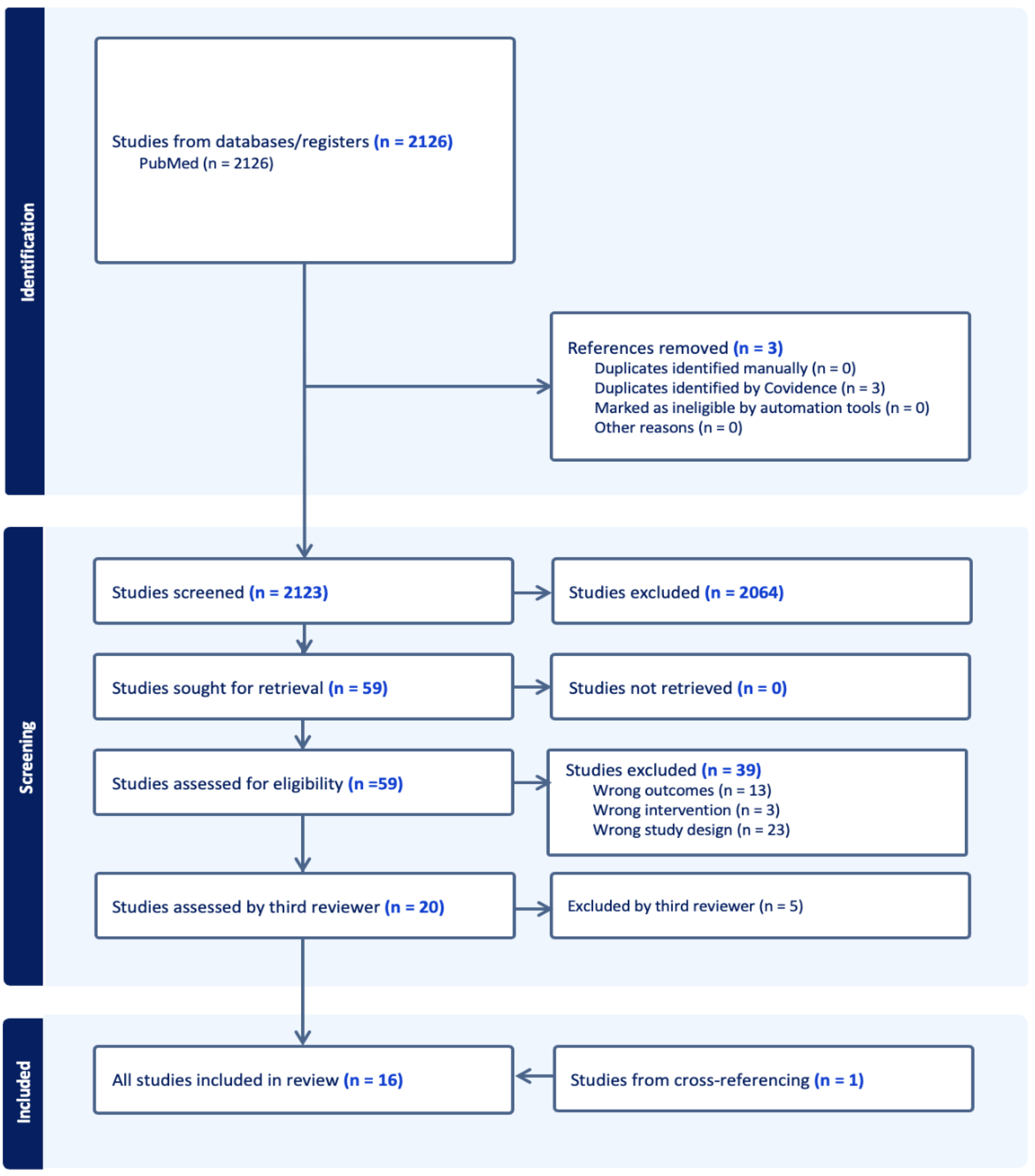

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Experimental Studies

3.1.1. Chronic Kidney Disease

3.1.2. Kidney Transplant Recipients

3.1.3. Haemodialysis Patients

3.2. Cohort Studies

3.2.1. General Adult Populations

3.2.2. Cohort Studies in Kidney Transplant Recipient

3.2.3. Cohort Study in Type 1 Diabetes Patients

3.2.4. Cohort Study in Chronic Kidney Disease Cohort

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CKD | Chronic kidney disease |

| GFR | Glomerular filtration rate |

| NF-kB | Nuclear factor kappa beta |

| BMP2 | Bone morphogenic protein 2 |

| VSMC | Vascular smooth muscle cell |

| T2D | Type 2 diabetes |

| T1D | Type 1 diabetes |

| MKs | Menaquinones |

| VKDP | Vitamin K dependent protein |

| Dp-ucMGP | Dephospho-uncarboxylated matrix Gla protein |

| PIVKA | Protein induced by vitamin k absence |

| GAS-6 | Growth arrest specific protein 6 |

| OR | Odds ratio |

| CI | Confidence interval |

| RCT | Randomized controlled trial |

| KTR | Kidney transplant recipients |

| HD | Haemodialysis |

| Uc-OC | Uncarboxylated osteocalcin |

| OC | Osteocalcin |

| eGFR | Estimated glomerular filtration rate |

| UACR | Urine albumin creatinine ratio |

| ESKD | End stage kidney disease |

Appendix A. Search Strategy

| MeSH terms | Kidney failure, chronic | Renal insufficiency, chronic | Renal insufficiency | Glomerulosclerosis focal segmental | Glomerular filtration rate | Estimated glomerular filtration rate | eGFR | Proteinuria | Albuminuria |

Renal Dialysis |

Dialysis |

|||

| Entry terms | Renal failure, chronic | Chronic renal insufficiencies | Renal insufficiencies | Segmental glomerulosclerosis focal | Filtration rate, glomerular | Proteinurias | Albuminurias | Dialyses, renal | Dialyses | |||||

| Chronic renal Failure | Renal insufficiencies, chronic | Kidney insufficiency | Glomerulo-nephritis, focal sclerosing | Filtration rates, Glomerular | Renal dialyses | |||||||||

| End-stage kidney disease | Chronic kidney insufficiency | Insufficiency, kidney | Focal sclerosing glomerulo-nephritides | Glomerular filtration rates | Dialysis, renal | |||||||||

| Disease, end-stage kidney | Chronic kidney insufficiencies | Kidney insufficiencies | Focal sclerosing glomerulonephritis | Rate, glomerular filtration | Hemodialysis | |||||||||

| End stage kidney Disease | Kidney insufficiencies chronic | Kidney failure | Glomerulo-nephritides, focal sclerosing | Rates, glomerular filtration | Hemodialyses | |||||||||

| Kidney disease, end-Stage | Chronic renal insufficiency | Failure, kidney | Sclerosing glomerulo-nephritides, focal | Dialysis, extracorporeal | ||||||||||

| ESRD | Kidney insufficiency, chronic | Failures, kidney | Sclerosing glomerulonephritis focal | Dialyses, extracorporeal | ||||||||||

| End-stage renal disease | Chronic kidney diseases | Kidney failures | Glomerulosclerosis focal | Extracorporeal dialyses | ||||||||||

| Disease, end-stage renal | Chronic kidney disease | Renal failure | Focal glomerulosclerosis | Extracorporeal dialysis | ||||||||||

| End stage renal disease | Disease, chronic kidney | Failure, renal | Focal segmental glomerulosclerosis | |||||||||||

| Renal disease, end-stage | Diseases, chronic kidney | Failures, renal | Hyalinosis, segmental glomerular | |||||||||||

| Renal disease, end stage | Kidney disease, chronic | Renal failures | Glomerular hyalinosis, segmental | |||||||||||

| Renal failure, end-stage | Kidney diseases, chronic | Hyalinosis, segmental | ||||||||||||

| End-stage renal failure | Chronic renal diseases | Segmental hyalinosis | ||||||||||||

| Renal failure, end stage | Chronic renal disease | Segmental glomerular hyalinosis | ||||||||||||

| Chronic kidney failure | Disease, chronic renal | |||||||||||||

| Diseases, chronic renal | ||||||||||||||

| Renal disease, chronic | ||||||||||||||

| Renal diseases, chronic | ||||||||||||||

| Abbreviations: eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; ESRD, end-stage renal disease; MeSH, Medical Subject Headings; | ||||||||||||||

| MeSH terms | Carboxyprothrombin | Vitamin K1 | Vitamin K2 | Menaquinone 7 | Matrix Gla Protein | Dp-ucMGP | ucMGP | Osteocalcin | Vitamin K |

| Entry terms | Decarboxyprothrombin | Phyto-nadione | Mena-quinone | Menaquinone K7 | Gla protein, matrix | Desphospho-uncarboxylated matrix GLA protein, human | 4-Carboxyglutamic protein, bone | ||

| Des(gamma-carboxy)prothrombin | Phyllo-quinone | Vitamin K quinone | Vitamin MK 7 | Matrix gamma-carboxyglu-tamic acid protein | Dephosphory-lated uncarboxylated matrix Gla protein | 4 Carboxyglutamic protein, bone | |||

| Des-gamma-carboxy prothrombin | Phyto-menadione | Vitamin K2 | Menaquinone-7 | Bone 4-carboxy- glutamic protein |

|||||

| Descarboxylated prothrombin | Vitamin K1 | Mena-quinones | Vitamin K2(35) | Protein, bone 4-carboxyglutamic | |||||

| Descarboxyprothrombin | Konakion | 1,4-naphthalenedione, 2-(3,7,11,15,19,23,27-heptamethyl-2,6,10,14,18,22,26-octacosaheptaenyl)-3-methyl-, (all-E)- | Bone gamma-carboxyglutamic acid protein | ||||||

| Non-carboxylated factor II | Phyllohydro-quinone | Bone gamma carboxyglutamic acid protein | |||||||

| PIVKA II | Aqua-mephyton | Bone Gla protein | |||||||

| PIVKA-II | Protein, bone Gla | ||||||||

| protein induced by vitamin K absence or antagonist-II | Calcium-binding protein, vitamin K-dependent | ||||||||

| Des-gamma-carboxyprothrombin | Calcium binding protein, vitamin K dependent | ||||||||

| DCP (prothrombin) | Gla protein, bone | ||||||||

| Acarboxy prothrombin | Vitamin K-dependent bone protein | ||||||||

| protein induced by vitamin K absence or antagonists | Vitamin K dependent bone protein | ||||||||

| PIVKA | |||||||||

| Prothrombin precursor | |||||||||

| Isoprothrombin | |||||||||

| Abbreviations: DCP, Des-gamma-carboxy prothrombin; dp-ucMGP, dephospho-uncarboxylated matrix Gla protein; uc-MGP, uncarboxylated matrix Gla protein; PIVKA, protein induced by vitamin K absence or antagonist; | |||||||||

Appendix B

Appendix C. Extracted Data

| Author | Country | Title | Study design | Population description | Sample size | Intervention | Kidney outcome (Primary/secondary) | Vitamin K measurements/outcomes |

| Lees et al. 2021 | United Kingdom | The ViKTORIES trial: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of vitamin K supplementation to improve vascular health in kidney transplant recipients. | RCT | KTR with functioning kidney transplant for 1 year or more. | 90 | Vitamin K (menadiol diphosphate) 5 mg orally x3 weekly for 12 months + Placebo (n=45 intervention, n=45 placebo). | Secondary: No treatment effect on eGFR or urine protein-creatinine ratio between intervention group and placebo. | Dp-ucMGP: Significant lowering in intervention group to placebo. |

| Eelderink et al. 2023 | Netherlands | Effect of vitamin K supplementation on serum calcification propensity and arterial stiffness in vitamin K-deficient kidney transplant recipients: A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial. | RCT | KTR with eGFR>20 and vitamin K deficiency (plasma dp-ucMGP >500 pmol/L). | 40 | Vitamin K2 (MK-7) 360 μg/day for 12 weeks + placebo (n=20 intervention, n=20 placebo). | Secondary: No treatment effect on eGFR. | Dp-ucMGP, ucOC, ucOC/cOC ratio: all showed significant lower score in treatment group compared with placebo. |

| Naiyarakseree et al. 2023 | Thailand | Effect of Menaquinone-7 Supplementation on Arterial Stiffness in Chronic Hemodialysis Patients: A Multicenter Randomized Controlled Trial. | RCT | Chronic HD patients with arterial stiffness (cfPWV ≥ 10 m/s). | 96 | Vitamin K2 (MK-7) 375 µg/daily for 24 weeks, no placebo (n=50 intervention, n=46 control). | No significant differences or changes in serum creatinine after 12 and 24 weeks. | No vitamin K measurements. |

| Witham et al. 2020 | United Kingdom | Vitamin K Supplementation to Improve Vascular Stiffness in CKD: The K4Kidneys Randomized Controlled Trial. | RCT | CKD patients stage 3b or 4 (defined as an eGFR of >15 ml/min and <45 ml/min). | 159 | vitamin K2 (MK-7) 400 µg tablet/day for 12 months + placebo (n=80 intervention, n=79 placebo). | eGFR, urinary protein-creatinine ratio and serum creatinine: No significant differences in intervention group to placebo. | Significantly lowered osteocalcin and log-transformed dp-ucMGP between intervention and placebo. |

| Kurnatowska et al. 2015 | Poland | Effect of vitamin K2 on progression of atherosclerosis and vascular calcification in nondialyzed patients with chronic kidney disease stages 3-5. | RCT | CKD stage 3-5 with eGFR <60 for at least 6 months. | 42 | Vitamin K2 (MK-7) 90 µg/day + 10 µg vitamin D for 270±12 days + placebo 10µg vitamin D/day (n=29 intervention, n=13 placebo). | Significant rise in serum creatinine in intervention group. Significant group difference in eGFR after intervention (decline in eGFR in intervention group). | Significant decrease in dp-ucMGP in intervention group, but no significant difference to placebo. Significant decrease in osteocalcin in treatment group, significant increase in placebo group, but no significant difference between the groups. Borderline significant increase in MGP for treatment group, no significant difference to placebo. |

| Oikonomaki et al. 2019 | Greece | The effect of vitamin K2 supplementation on vascular calcification in haemodialysis patients: a 1-year follow-up randomized trial. | RCT | ESRD patients on haemodialysis. | 102 | Vitamin K2 (MK-7) 200 µg/day for 12 months, no placebo (n=58 intervention, n=44 control). | No significant change or difference in serum creatinine. | Significant decrease in ucMGP in intervention group at 12 months follow-up and significant difference to placebo group. |

| Macias-Cervantes et al. 2024 | Mexico | Effect of vitamin K1 supplementation on coronary calcifications in hemodialysis patients: a randomized controlled trial. | RCT | Chronic haemodialysis patients. 58.3% (n=35) with diabetic nephropathy being the primary etiology of chronic kidney disease. The median duration of haemodialysis was 48 months (12–204). | 60 | Vitamin K1 10 mg IV x3 weekly, after haemodialysis session, for 12 months, placebo (n=30 intervention, n=30 placebo). | Secondary: Serum creatinine: No significant changes between groups at follow-up. | No vitamin K measurements. |

| Kurnatowska et al. 2016 | Poland | Plasma Desphospho-Uncarboxylated Matrix Gla Protein as a Marker of Kidney Damage and Cardiovascular Risk in Advanced Stage of Chronic Kidney Disease. | RCT | CKD patients stage 4-5 with a coronary calcification score (CACS) of ≥10 Agatston units. | 38 | Vitamin K2 (MK-7) 90 µg/day + 10 µg vitamin D for 270±12 days. Placebo with vitamin D 10 µg (n=26 intervention, n=12 placebo). | Primary: Association between plasma dp-ucMGP and kidney function (serum creatinine, eGFR and proteinuria): No significant change in eGFR in either group after substitution. Strong inverse association between eGFR and dp-ucMGP. Positive correlation between dp-ucMGP, creatinine and proteinuria. | Dp-ucMGP: Significant decrease from baseline to follow-up in intervention group, compared to placebo? Osteocalcin: Significant difference between groups at follow-up. |

| Mansour et al. 2017 | Lebanon | Vitamin K2 supplementation and arterial stiffness among renal transplant recipients-a single-arm, single-center clinical trial. | Non-Controlled clinical trial | KTR patients with functional renal graft. | 60 | Vitamin K2 (MK-7) 360 μg/day for 8 weeks, no control group (n=60 intervention). | Secondary: Serum creatinine: Borderline significant increase from baseline to follow-up. | Dp-ucMGP: Significant decrease from baseline to follow-up. |

|

Table C1: Data table of included clinical studies. Abbreviations: CKD, chronic kidney disease; cOC, carboxylated osteocalcin; dp-ucMGP, dephospho-uncarboxylated Matrix Gla-Protein; eGFR, Estimated glomerular filtration rate; ESKD, end stage kidney disease; KTR, kidney transplant recipients; MGP, matrix Gla protein; MK-7, menaquinone 7; Q1-Q4, quartiles 1-4; RCT, randomized controlled trial; T1D, type 1 diabetes; T2D, Type 2 diabetes; ucMGP, uncarboxylated matrix Gla protein; ucOC, uncarboxylated osteocalcin. | ||||||||

| Author | Country | Title | Study design | Aim of study/purpose | Population description | Sample size | Follow up (years) | Kidney Outcome (Primary/Secondary) | Vitamin K measurements |

| Van Ballegooijen et al. 2019 | Nether-lands | Joint association of vitamins D and K status with long-term outcomes in stable kidney transplant recipients. | Cohort study | The association of both vitamins D and K status, and vitamin D treatment with all-cause mortality and death-censored graft failure. |

Adult kidney transplant recipients. Stable kidney function, median 6.1 years post transplantation, mean age of 52 years, 53% male. | 461 | Median 9.8 | Primary: Associations of combined vitamin D and dp-ucMGP levels with graft failure(return to dialysis therapy or re-transplantation), showed significantly. Higher eGFR in the groups with low dp-ucMGP levels. | dp-ucMGP <1057pmol/L or ≧ 1057pmol/L. |

| Keyzer et al. 2015 | Nether-lands | Vitamin K status and mortality after kidney transplantation: a cohort study. | Cohort study | Investigating if Vitamin K defficiency increase risk of all cause mortality and transplant failure after kidney transplantation. | Kidney transplant recipients with stable kidney function, 56% male, mean age 51 years, median of 6 years after kidney transplantation. | 518 | Median 9.8 | Primary: Highest quartile showed significant increase in transplant failure in three adjustment models, association was lost after adjustment for baseline kidney function. | dp-ucMGP Quartiles Q1: <734pmol/L, Q2: 734-1038 pmol/L, Q3: 1039-1535 pmol/L and Q4: >1535 pmol/L. |

| Wei et al. 2017 | Belgium | Desphospho-uncarboxylated matrix Gla protein is a novel circulating biomarker predicting deterioration of renal function in the general population. | Cohort study | Does dp-ucMGP predict a decrease in eGFR. | Flemish from the FLEMENGHO family-based population study, present analysis covered period from 1996-2015, 50.6% women, white europeans. | 1009 | Median 8.9 | Primary: Association between eGFR and plasma dp-ucMGP. with significant decline in eGFR between low and high levels of dp-ucMGP. | dp-ucMGP low: mean 2.42 µg/L (1.87–3.06) and high mean 5.08 ug/L (4.22–6.30). |

| Nielsen et al. 2025 | Den-mark | The associations between functional vitamin K status and all-cause mortality, cardiovascular disease and end-stage kidney disease in persons with type 1 diabetes | Cohort study | To assess the association of dp-ucMGP with mortality, cardiovascular disease and progression to ESKD in persons with T1D | Data from a cohort of persons with T1D followed up at Steno Diabetes Center Copenhagen, Denmark. 55% male. | 667 | Approximately 5-7 | Primary: Progression of ESKD. Lost significance in multivariable adjustment model four after adjusting for baseline eGFR and urinary albumin excretion rate. | dp-ucMGP quartiles (pmol/L): 316.5 (302.0–336.0) 386.0 (370.0–398.0) 457.0 (433.5–478.0) 611.0 (551.0–775.0). |

| O'Seaghdha et al. 2012 | USA | Phylloquinone and vitamin D status: associations with incident chronic kidney disease in the Framingham Offspring cohort. | Cohort study | Investigating if deficiencies of vitamins D and K may be associated with incident CKD and/or incident albuminuria in general population. | Framingham Heart Study participants (mean age 58 years; 50.5% women), free of CKD (eGFR<60 ml/min/1.732). |

1442 | Median 7.8 | Primary: Significantly higher incidence of CKD in the highest quartile of phylloquinone. Secondary: Significant association between higher quartiles of phylloquinone and incident albuminuria, but a borderline significance in the highest quartiles. | Phylloquinone levels stratified into 4 quartiles (nmol/L): 0.05-0.55, 0.56-0.98, 0.99-1.77 and 1.78-35.02. |

| Groothof et al. 2020 | Nether-lands | Functional vitamin K status and risk of incident chronic kidney disease and microalbuminuria: a prospective general population-based cohort study. | Cohort study | To assess the association between. circulating dp-ucMGP and incident CKD |

Inhabitants from the city of Groningen, mean age 52.3 years, mainly Caucasian. | 3969 | Median 7.1 | Primary: Incident CKD or microalbuminuria. The association of plasma dp-ucMGP with incident CKD disappeared following adjustment for the confounding effect of baseline eGFR. The association to proteinuria in males disappeared after adjustment for age. | Dp-ucMGP levels stratified in four quartiles (pmol/L) Males: <245, 245–381, 382–550 and >550. Females: <193, 193-341, 342–513 and >513. |

| Roumeliotis et al. 2020 | Greece | The Association of dp-ucMGP with Cardiovascular Morbidity and Decreased Renal Function in Diabetic Chronic Kidney Disease. | Cohort study | Investigating the association between dp-ucMGP and mortality, CV disease, and decreased renal function in a cohort of patients with diabetic CKD. | Diabetic CKD patients, divided into two groups: dp-ucMGP over and under 656 pM Mean age 67.4 (dp-ucMGP <656 pM) Mean age 69.7 (dp-ucMGP >656 pM) Almost all male in both groups. |

66 | Median 7 | Primary: Significantly higher risk of eGFR decline or progression to ESKD which remained after adjustment for T2D, proteinuria and serum albumin. | Dp-ucMGP < 656 pmol/L and Dp-ucMGP ≥ 656 pmol/L. |

|

Table C2: Data table of included cohort studies. Abbreviations: CKD, chronic kidney disease; dp-ucMGP, dephosphorylated-uncarboxylated matrix Gla-protein; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; ESKD, end stage kidney disease; Q1-Q4, quartiles 1-4; T1D, type 1 diabetes; T2D, type 2 diabetes; ucMGP, uncarboxylated matrix Gla-protein. | |||||||||

References

- Hill NR, Fatoba ST, Oke JL, Hirst JA, O’Callaghan CA, Lasserson DS, et al. Global Prevalence of Chronic Kidney Disease – A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS One 2016;11. [CrossRef]

- Düsing P, Zietzer A, Goody PR, Hosen MR, Kurts C, Nickenig G, et al. Vascular pathologies in chronic kidney disease: pathophysiological mechanisms and novel therapeutic approaches. J Mol Med (Berl) 2021;99:335. [CrossRef]

- Shea MK, Booth SL. Vitamin K, Vascular Calcification, and Chronic Kidney Disease: Current Evidence and Unanswered Questions. Curr Dev Nutr 2019;3. [CrossRef]

- Dai L, Li L, Erlandsson H, Jaminon AMG, Qureshi AR, Ripsweden J, et al. Functional vitamin K insufficiency, vascular calcification and mortality in advanced chronic kidney disease: A cohort study. PLoS One 2021;16. [CrossRef]

- Rizzoni D, Agabiti-Rosei E. Structural abnormalities of small resistance arteries in essential hypertension. Intern Emerg Med 2012;7:205–12. [CrossRef]

- Oates JC, Russell DL, Van Beusecum JP. Endothelial cells: potential novel regulators of renal inflammation. American Journal of Physiology-Renal Physiology 2022;322:F309–21. [CrossRef]

- Shioi A, Morioka T, Shoji T, Emoto M. The Inhibitory Roles of Vitamin K in Progression of Vascular Calcification. Nutrients 2020;12:583. [CrossRef]

- Alicic RZ, Rooney MT, Tuttle KR. Diabetic kidney disease: Challenges, progress, and possibilities. Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology 2017;12:2032–45. [CrossRef]

- Lacombe J, Guo K, Bonneau J, Faubert D, Gioanni F, Vivoli A, et al. Vitamin K-dependent carboxylation regulates Ca2+ flux and adaptation to metabolic stress in β cells. Cell Rep 2023;42. [CrossRef]

- Moore DJ, Leibel NI, Polonsky W, Rodriguez H. Understanding the different stages of type 1 diabetes and their management: a plain language summary. Curr Med Res Opin 2025;41:13–24. [CrossRef]

- Bhikadiya D, Bhikadiya K. Calcium Regulation And The Medical Advantages Of Vitamin K2. South East Eur J Public Health 2024:1568–79. [CrossRef]

- Roumeliotis S, Dounousi E, Salmas M, Eleftheriadis T, Liakopoulos V. Vascular Calcification in Chronic Kidney Disease: The Role of Vitamin K- Dependent Matrix Gla Protein. Front Med (Lausanne) 2020;7:154. [CrossRef]

- Chen HG, Sheng LT, Zhang YB, Cao AL, Lai YW, Kunutsor SK, et al. Association of vitamin K with cardiovascular events and all-cause mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Nutr 2019;58:2191–205. [CrossRef]

- Van Der Meer JHM, Van Der Poll T, Van’t Veer C. TAM receptors, Gas6, and protein S: roles in inflammation and hemostasis. Blood 2014;123:2460–9. [CrossRef]

- Thamratnopkoon S, Susantitaphong P, Tumkosit M, Katavetin P, Tiranathanagul K, Praditpornsilpa K, et al. Correlations of Plasma Desphosphorylated Uncarboxylated Matrix Gla Protein with Vascular Calcification and Vascular Stiffness in Chronic Kidney Disease. Nephron 2017;135:167–72. [CrossRef]

- Kaesler N, Schreibing F, Speer T, Puente-Secades S de la, Rapp N, Drechsler C, et al. Altered vitamin K biodistribution and metabolism in experimental and human chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int 2022;101:338–48. [CrossRef]

- Grzejszczak P, Kurnatowska I. Role of Vitamin K in CKD: Is Its Supplementation Advisable in CKD Patients? Kidney Blood Press Res 2021;46:523–30. [CrossRef]

- Bellone F, Cinquegrani M, Nicotera R, Carullo N, Casarella A, Presta P, et al. Role of Vitamin K in Chronic Kidney Disease: A Focus on Bone and Cardiovascular Health. Int J Mol Sci 2022;23:5282. [CrossRef]

- Taher M, Wafa E, Sayed-Ahmed N, el Dahshan K. Correlation Between Matrix Gla Protein Level and Effect of Vitamin K2 Therapy on Vascular Calcification in Hemodialysis Patients. Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation 2023;38. [CrossRef]

- Dihingia A, Ozah D, Baruah PK, Kalita J, Manna P. Prophylactic role of vitamin K supplementation on vascular inflammation in type 2 diabetes by regulating the NF-κB/Nrf2 pathway via activating Gla proteins. Food Funct 2018;9:450–62. [CrossRef]

- Manna P, Kalita J. Beneficial role of vitamin K supplementation on insulin sensitivity, glucose metabolism, and the reduced risk of type 2 diabetes: A review. Nutrition 2016;32:732–9. [CrossRef]

- Lauridsen JA, Leth-Møller KB, Møllehave LT, Kårhus LL, Dantoft TM, Kofoed KF, et al. Investigating the associations between uncarboxylated matrix gla protein as a proxy for vitamin K status and cardiovascular disease risk factors in a general adult population. Eur J Nutr 2025;64:1–9. [CrossRef]

- Peters, MDJ; Godfrey, C; McInterney, P; Munn, Z; Tricco, AC; Khalil, H. Scoping Reviews (2020). Aromataris E, Lockwood C, Porritt K, Pilla, B; Jordan, Z; editors. JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis. JBI; 2024. Available from: https://synthesismanual.jbi.global. Last accessed: 20/05/2025; n.d. [CrossRef]

- Covidence 2025. Covidence systematic review software, Veritas Health Innovation, Melbourne, Australia. Available at www.covidence.org. Last accessed: 25/05/2025; n.d.

- Witham MD, Lees JS, White M, Band M, Bell S, Chantler DJ, et al. Vitamin K Supplementation to Improve Vascular Stiffness in CKD: The K4Kidneys Randomized Controlled Trial. J Am Soc Nephrol 2020;31:2434–45. [CrossRef]

- [Kurnatowska I, Grzelak P, Masajtis-Zagajewska A, Kaczmarska M, Stefańczyk L, Vermeer C, et al. Plasma Desphospho-Uncarboxylated Matrix Gla Protein as a Marker of Kidney Damage and Cardiovascular Risk in Advanced Stage of Chronic Kidney Disease. Kidney Blood Press Res 2016;41:231–9. [CrossRef]

- Kurnatowska I, Grzelak P, Masajtis-Zagajewska A, Kaczmarska M, Stefańczyk L, Vermeer C, et al. Effect of vitamin K2 on progression of atherosclerosis and vascular calcification in nondialyzed patients with chronic kidney disease stages 3-5. Pol Arch Med Wewn 2015;125:631–40. [CrossRef]

- Lees JS, Rankin AJ, Gillis KA, Zhu LY, Mangion K, Rutherford E, et al. The ViKTORIES trial: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of vitamin K supplementation to improve vascular health in kidney transplant recipients. Am J Transplant 2021;21:3356–68. [CrossRef]

- Eelderink C, Kremer D, Riphagen IJ, Knobbe TJ, Schurgers LJ, Pasch A, et al. Effect of vitamin K supplementation on serum calcification propensity and arterial stiffness in vitamin K-deficient kidney transplant recipients: A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Am J Transplant 2023;23:520–30. [CrossRef]

- Mansour AG, Hariri E, Daaboul Y, Korjian S, A EA, Protogerou AD, et al. Vitamin K2 supplementation and arterial stiffness among renal transplant recipients-a single-arm, single-center clinical trial. J Am Soc Hypertens 2017;11:589–97. [CrossRef]

- Naiyarakseree N, Phannajit J, Naiyarakseree W, Mahatanan N, Asavapujanamanee P, Lekhyananda S, et al. Effect of Menaquinone-7 Supplementation on Arterial Stiffness in Chronic Hemodialysis Patients: A Multicenter Randomized Controlled Trial. Nutrients 2023;15. [CrossRef]

- Oikonomaki T, Papasotiriou M, Ntrinias T, Kalogeropoulou C, Zabakis P, Kalavrizioti D, et al. The effect of vitamin K2 supplementation on vascular calcification in haemodialysis patients: a 1-year follow-up randomized trial. Int Urol Nephrol 2019;51:2037–44. [CrossRef]

- Macias-Cervantes HE, Ocampo-Apolonio MA, Guardado-Mendoza R, Baron-Manzo M, Pereyra-Nobara TA, Hinojosa-Gutiérrez LR, et al. Effect of vitamin K1 supplementation on coronary calcifications in hemodialysis patients: a randomized controlled trial. J Nephrol 2025;38:511–9. [CrossRef]

- Groothof D, Post A, Sotomayor CG, Keyzer CA, Flores-Guerero JL, Hak E, et al. Functional vitamin K status and risk of incident chronic kidney disease and microalbuminuria: a prospective general population-based cohort study. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2021;36:2290–9. [CrossRef]

- O’Seaghdha CM, Hwang SJ, Holden R, Booth SL, Fox CS. Phylloquinone and vitamin D status: associations with incident chronic kidney disease in the Framingham Offspring cohort. Am J Nephrol 2012;36:68–77. [CrossRef]

- Wei FF, Trenson S, Thijs L, Huang QF, Zhang ZY, Yang WY, et al. Desphospho-uncarboxylated matrix Gla protein is a novel circulating biomarker predicting deterioration of renal function in the general population. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2018;33:1122–8. [CrossRef]

- Van Ballegooijen AJ, Beulens JWJ, Keyzer CA, Navis GJ, Berger SP, H de BM, et al. Joint association of vitamins D and K status with long-term outcomes in stable kidney transplant recipients. Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation 2020;35:706–14. [CrossRef]

- Keyzer CA, Vermeer C, Joosten MM, Knapen MH, Drummen NE, Navis G, et al. Vitamin K status and mortality after kidney transplantation: a cohort study. Am J Kidney Dis 2015;65:474–83. [CrossRef]

- Nielsen CFB, Thysen SM, Kampmann FB, Hansen TW, Jørgensen NR, Tofte N, et al. The associations between functional vitamin K status and all-cause mortality, cardiovascular disease and end-stage kidney disease in persons with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Obes Metab 2025;27:348–56. [CrossRef]

- Roumeliotis S, Roumeliotis A, Stamou A, Leivaditis K, Kantartzi K, Panagoutsos S, et al. The Association of dp-ucMGP with Cardiovascular Morbidity and Decreased Renal Function in Diabetic Chronic Kidney Disease. Int J Mol Sci 2020;21:6035. [CrossRef]

- Schlackow I, Simons C, Oke J, Feakins B, O’Callaghan CA, Richard Hobbs FD, et al. Long-term health outcomes of people with reduced kidney function in the UK: A modelling study using population health data. PLoS Med 2020;17:e1003478. [CrossRef]

- Sai Varsha MKN, Raman T, Manikandan R, Dhanasekaran G. Hypoglycemic action of vitamin K1 protects against early-onset diabetic nephropathy in streptozotocin-induced rats. Nutrition 2015;31:1284–92. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).