Submitted:

10 August 2025

Posted:

13 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

| Contents | ||

| Preface | 4 | |

| 1 | Introduction to Partial Difference Equations | 5 |

| 1.1 Motivation and Background........................................................................................................................................... | 5 | |

| 1.2 Discrete Function................................................................................................................................................... | 5 | |

| 1.3 Shift Operator...................................................................................................................................................... | 5 | |

| 1.4 Partial Shift Operator.............................................................................................................................................. | 6 | |

| 1.5 Ordinary Difference Equations....................................................................................................................................... | 6 | |

| 1.6 Partial Difference Equation......................................................................................................................................... | 6 | |

| 1.7 The Order of a Partial Difference Equation.......................................................................................................................... | 7 | |

| 1.8 Comparison with Ordinary Difference Equations....................................................................................................................... | 7 | |

| 1.9 Comparison with Partial Differential Equations...................................................................................................................... | 8 | |

| 1.10 Advantages of Rewriting Complex Systems as Partial Difference Equations............................................................................................. | 8 | |

| 1.11 Scope and Limitations............................................................................................................................................... | 8 | |

| 1.12 Classification and Examples......................................................................................................................................... | 9 | |

| 1.13 Notations........................................................................................................................................................... | 9 | |

| 2 | Linear Partial Difference Equations | 11 |

| 2.1 Motivation.......................................................................................................................................................... | 11 | |

| 2.2 Definition.......................................................................................................................................................... | 11 | |

| 2.3 Discrete 1D Transport Equation...................................................................................................................................... | 11 | |

| 2.4 Discrete 1D Diffusion Equation...................................................................................................................................... | 13 | |

| 2.5 Discrete 1D Wave Equation........................................................................................................................................... | 14 | |

| 3 | Discrete Function Spaces and Operators | 15 |

| 3.1 Motivation.......................................................................................................................................................... | 15 | |

| 3.2 Discrete Function Spaces............................................................................................................................................ | 16 | |

| 3.3 Operators........................................................................................................................................................... | 17 | |

| 3.4 The Kronecker Delta Function........................................................................................................................................ | 22 | |

| 3.5 The Discrete Green’s Function..................................................................................................................................... | 23 | |

| 3.6 Boundary Value Problems............................................................................................................................................. | 25 | |

| 4 | Elementary Cellular Automata | 26 |

| 4.1 Introduction........................................................................................................................................................ | 26 | |

| 4.2 Notation Evolution.................................................................................................................................................. | 26 | |

| 4.3 The Rule 90......................................................................................................................................................... | 27 | |

| 4.4 Rule 30............................................................................................................................................................. | 30 | |

| 4.5 The Rule 153........................................................................................................................................................ | 31 | |

| 4.6 Rule 45............................................................................................................................................................. | 32 | |

| 4.7 Rule 105............................................................................................................................................................ | 33 | |

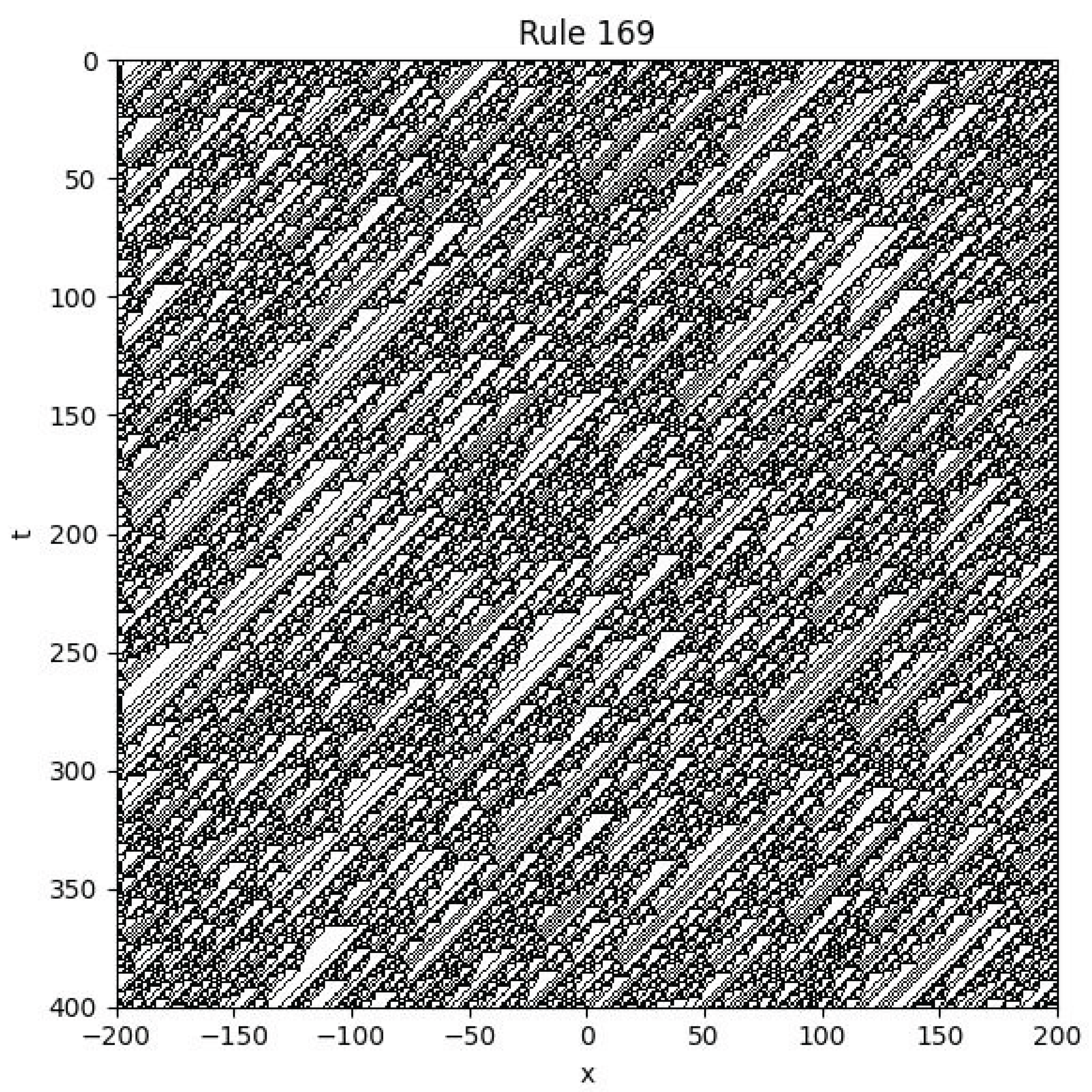

| 4.8 Rule 169............................................................................................................................................................ | 34 | |

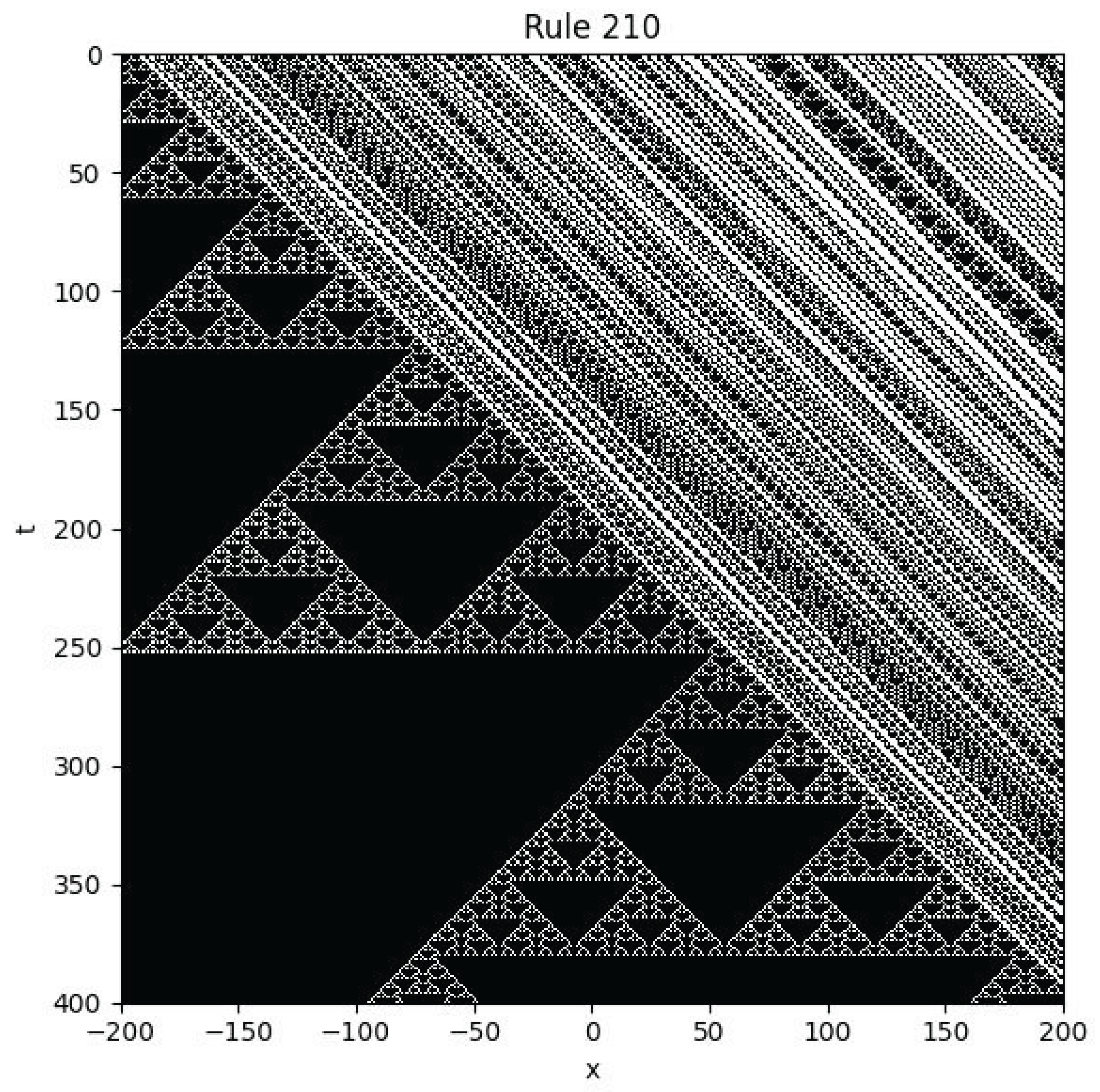

| 4.9 Rule 210............................................................................................................................................................ | 35 | |

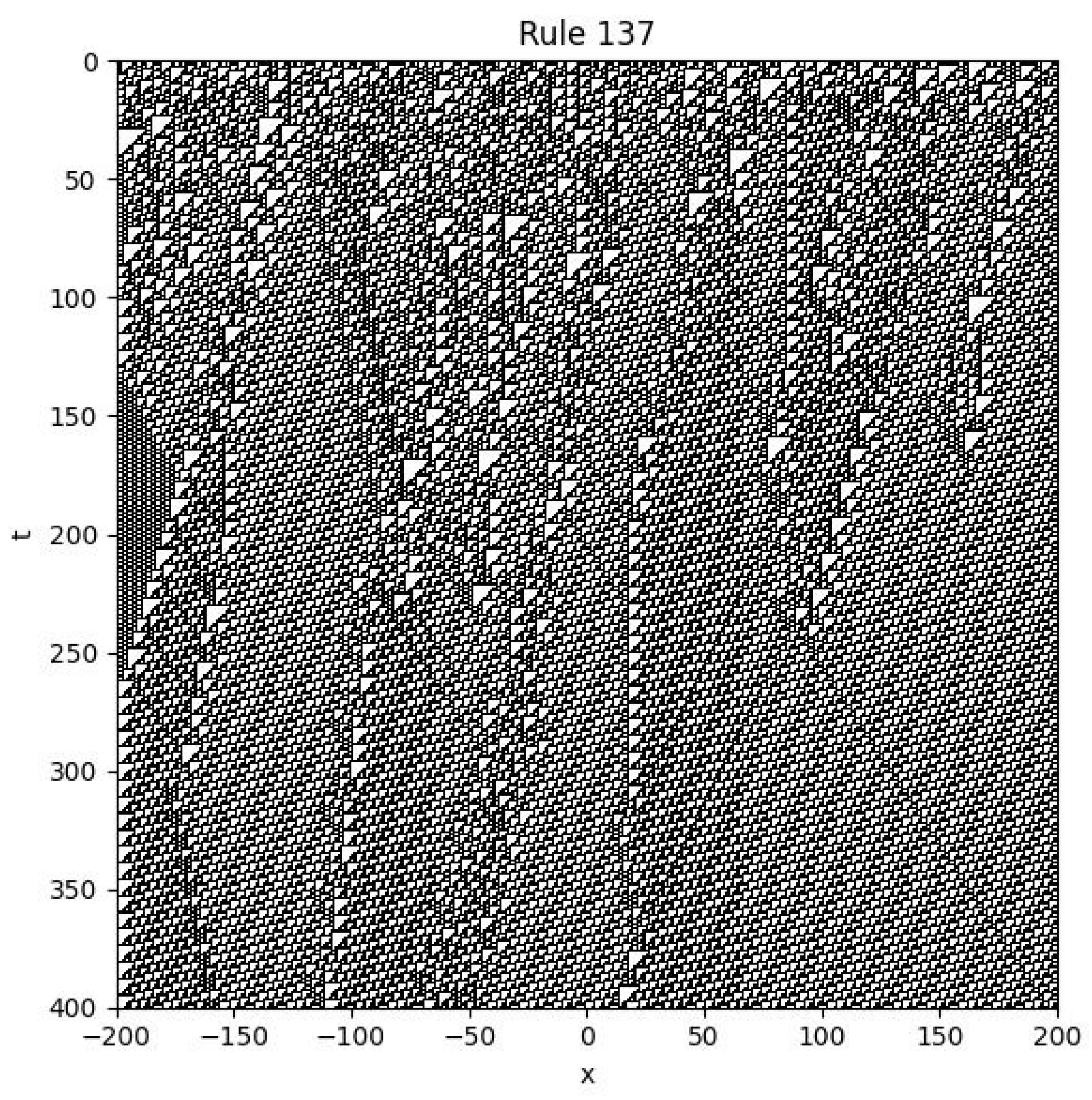

| 4.10 Rule 137............................................................................................................................................................ | 36 | |

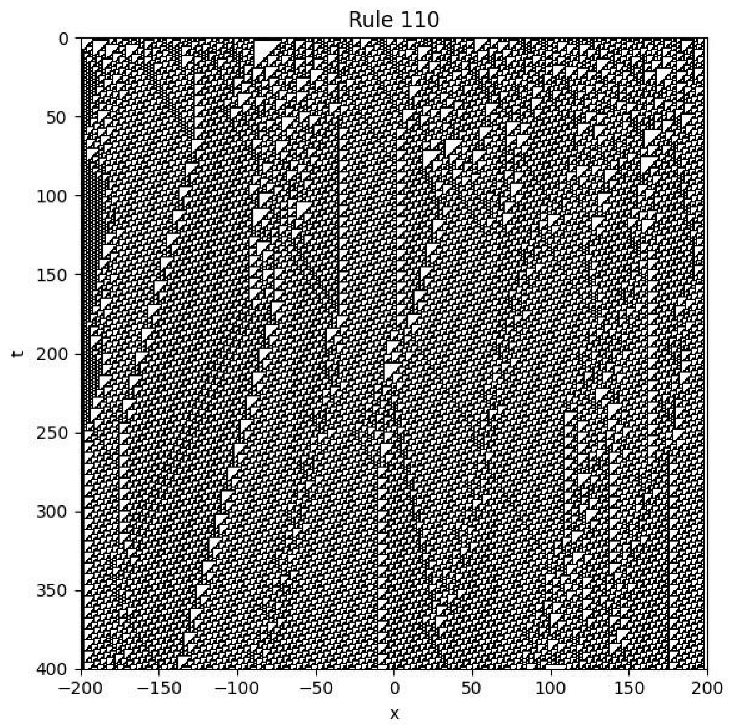

| 4.11 Rule 110............................................................................................................................................................ | 37 | |

| 5 | Other 1D Nonlinear Partial Difference Equations | 38 |

| 5.1 Introduction........................................................................................................................................................ | 38 | |

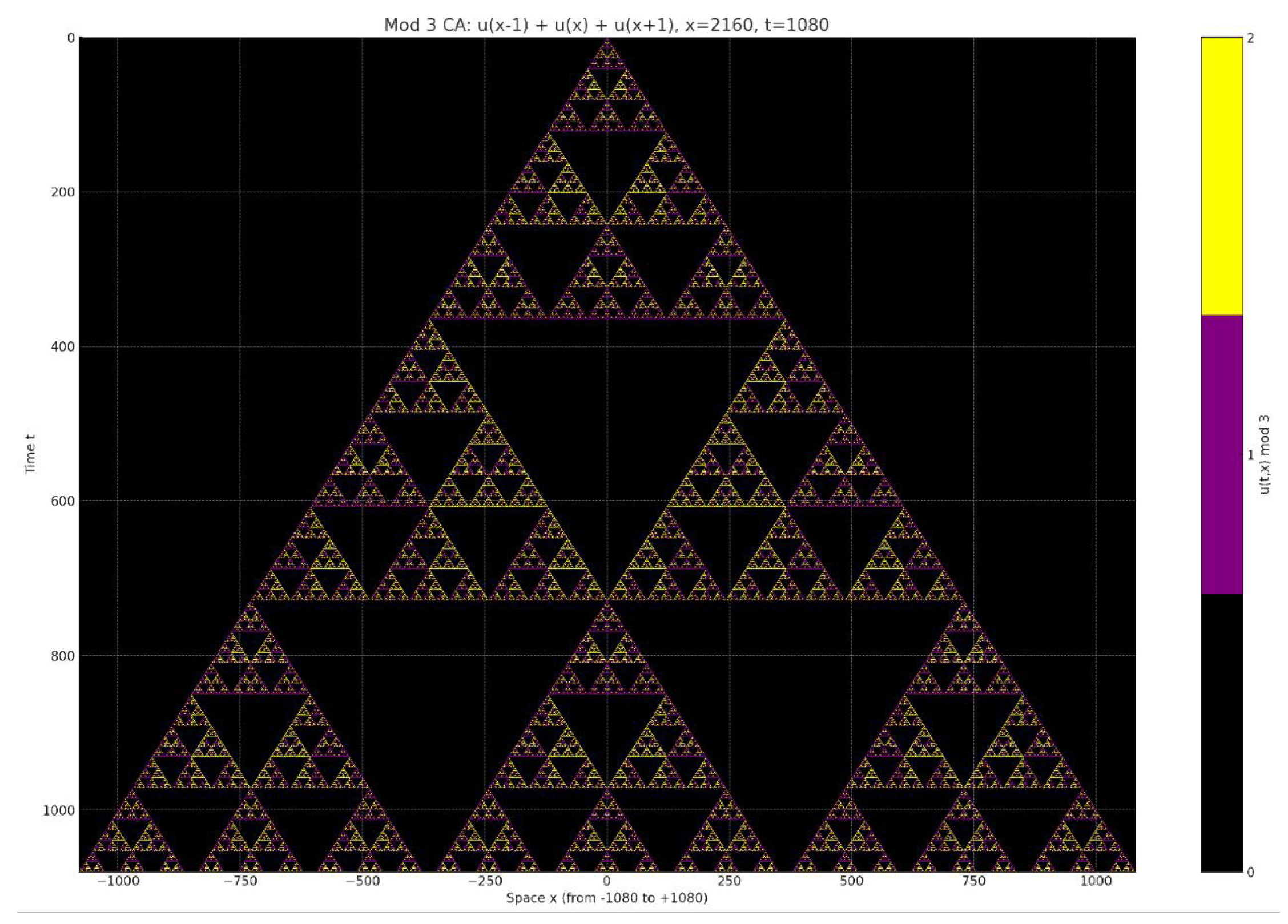

| 5.2 Sierpinski Fan Equation............................................................................................................................................. | 38 | |

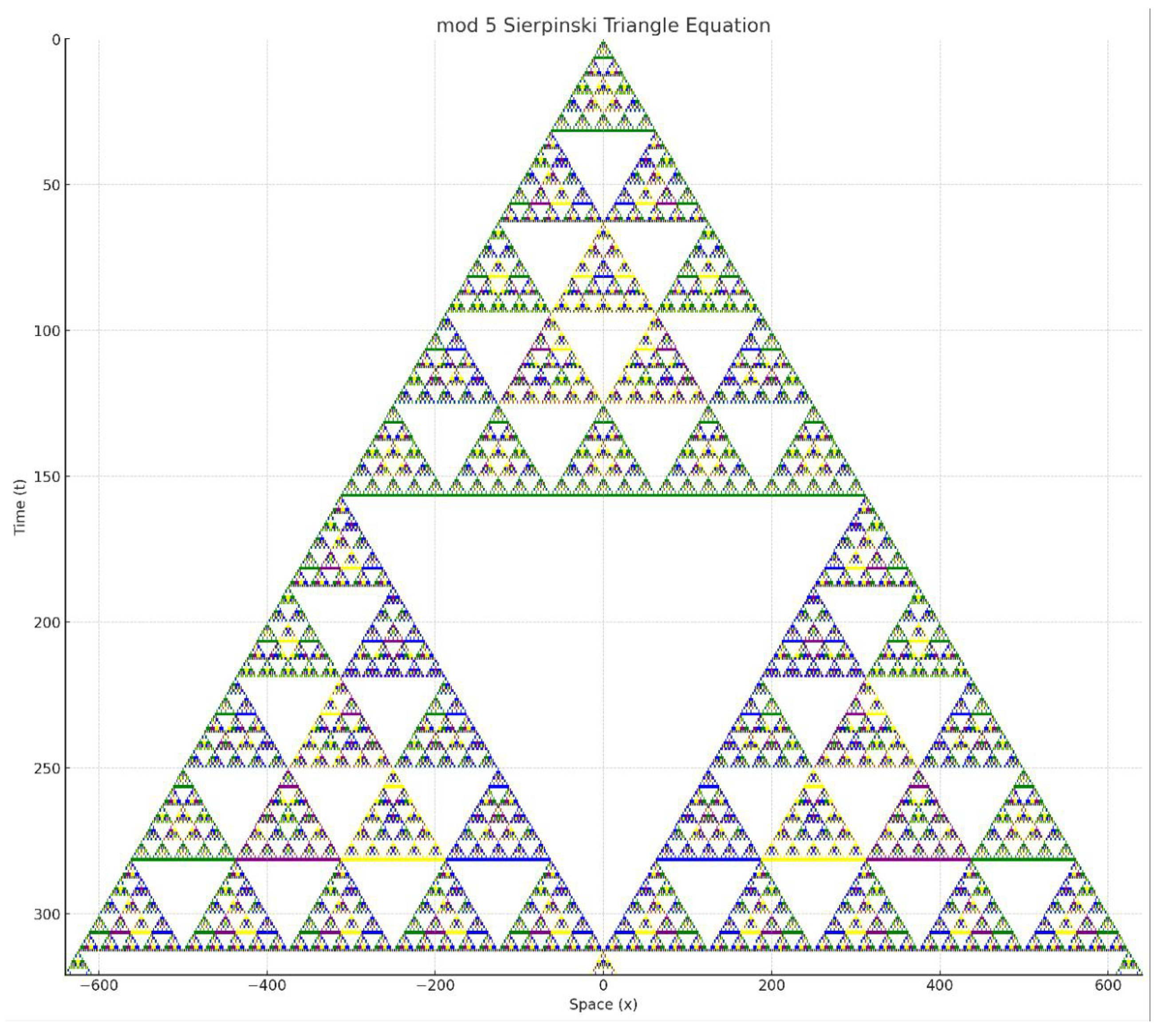

| 5.3 Mod 5 Sierpiński Equation.......................................................................................................................................... | 39 | |

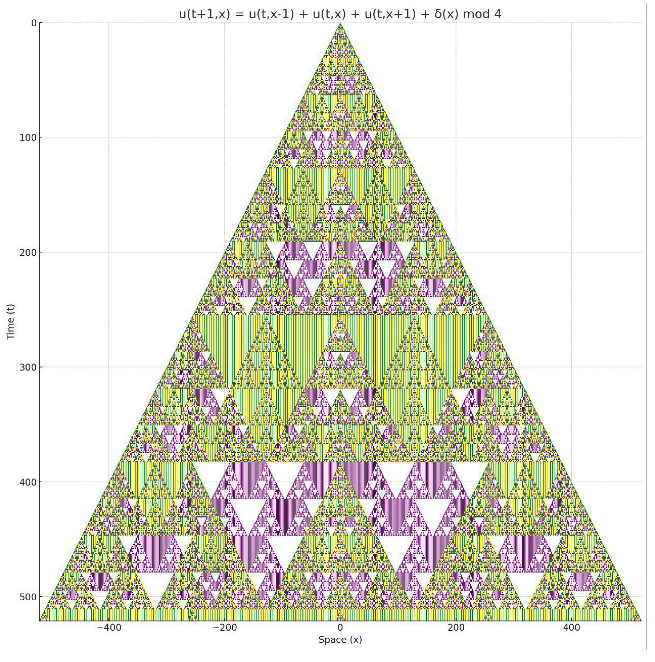

| 5.4 Mod 4 Sierpinski Fractal Equation................................................................................................................................... | 39 | |

| 6 | Coupled Map Lattice | 41 |

| 6.1 1D Coupled Map Lattice.............................................................................................................................................. | 41 | |

| 6.2 2D Coupled Map Lattice.............................................................................................................................................. | 42 | |

| 6.3 Explanation......................................................................................................................................................... | 42 | |

| 7 | The Conway’s Game of Life | 42 |

| 7.1 Conway’s Equation................................................................................................................................................. | 42 | |

| 7.2 Interpretation...................................................................................................................................................... | 43 | |

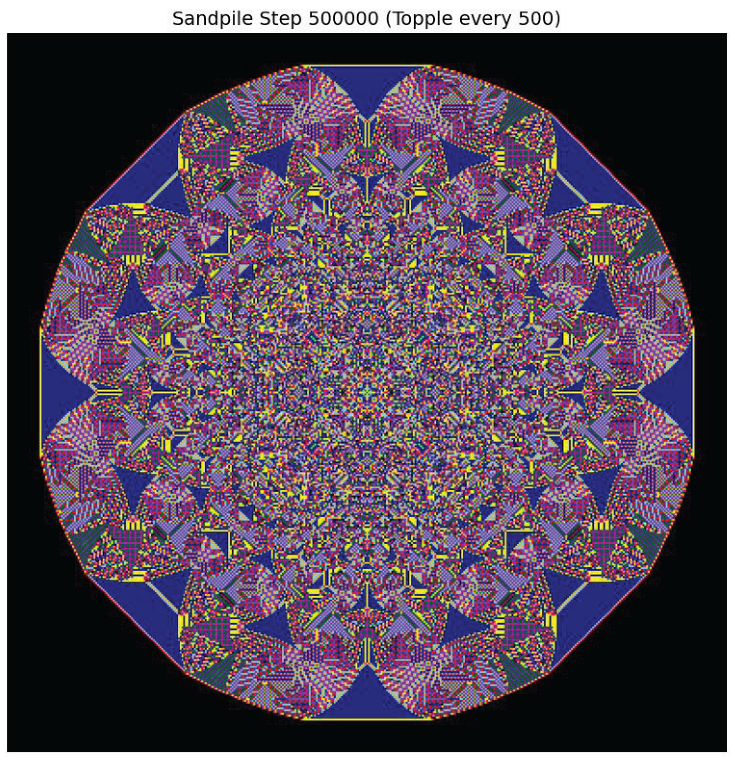

| 8 | Abelian Sandpile Model | 43 |

| 8.1 Abelian Sandpile Equation........................................................................................................................................... | 43 | |

| 8.2 Remarks............................................................................................................................................................. | 43 | |

| 8.3 The Sandpile Fractal................................................................................................................................................ | 44 | |

| 8.4 Extended Sandpile Model............................................................................................................................................. | 44 | |

| 8.5 Explanation for the Self-Organized Criticality...................................................................................................................... | 45 | |

| 8.6 Explanation for the Power Law Distribution.......................................................................................................................... | 46 | |

| 9 | OFC Earthquake Model | 46 |

| 9.1 OFC Earthquake Equation............................................................................................................................................. | 46 | |

| 9.2 Observations and Phenomena.......................................................................................................................................... | 47 | |

| 10 | Forest Fire Model | 47 |

| 10.1 Forest Fire Equation................................................................................................................................................ | 47 | |

| 10.2 Definitions......................................................................................................................................................... | 47 | |

| 10.3 Transition Logic (via mod 3)........................................................................................................................................ | 48 | |

| 10.4 Interpretation...................................................................................................................................................... | 48 | |

| 10.5 Observations and Phenomena.......................................................................................................................................... | 48 | |

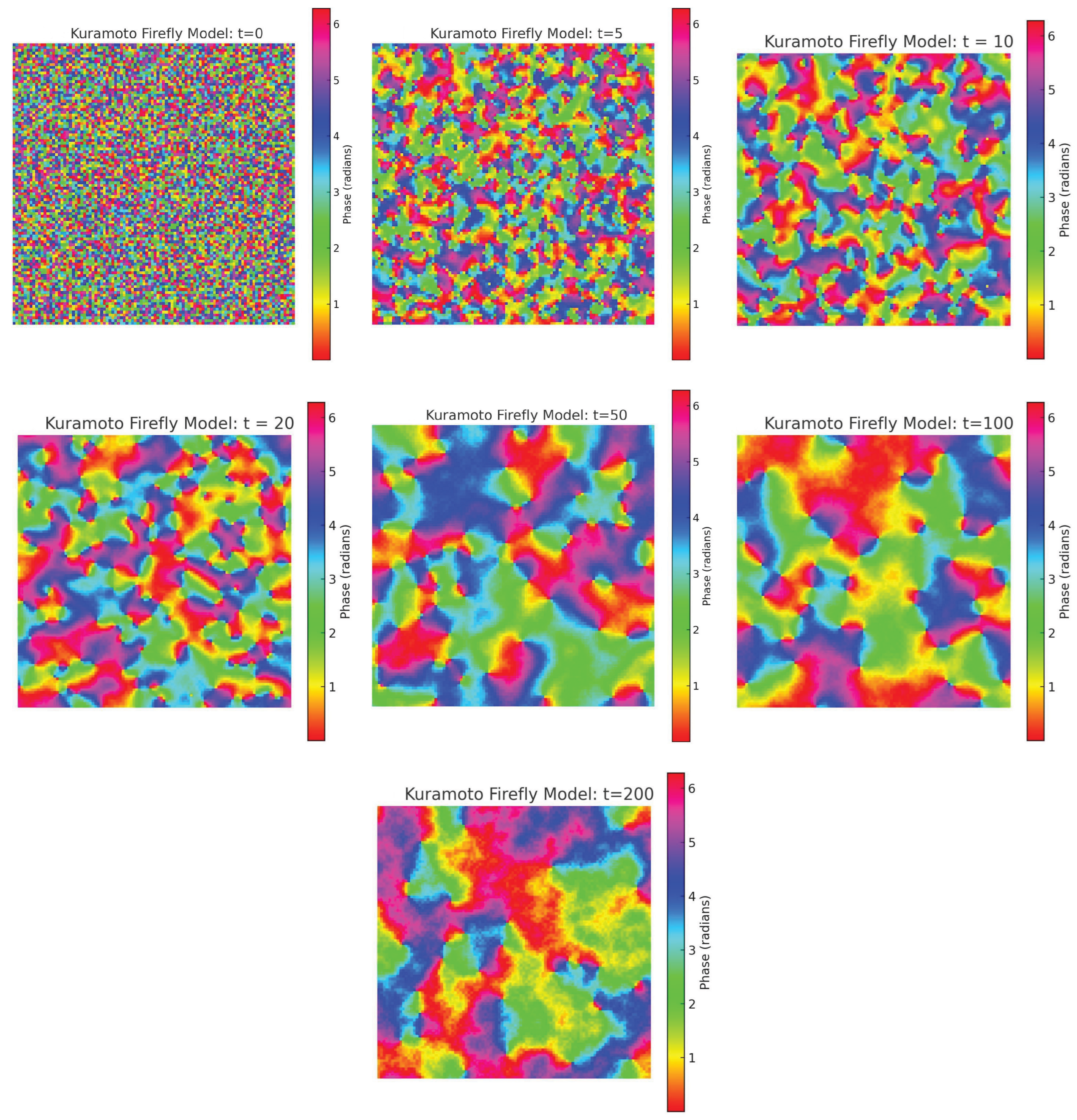

| 11 | Kuramoto Firefly Model | 48 |

| 11.1 Kuramoto Equation................................................................................................................................................... | 48 | |

| 11.2 Principle of Locality............................................................................................................................................... | 49 | |

| 11.3 Observations and Phenomena.......................................................................................................................................... | 49 | |

| 12 | Ising Model | 50 |

| 12.1 Governing Equation.................................................................................................................................................. | 50 | |

| 12.2 Physical Interpretation............................................................................................................................................. | 51 | |

| 13 | Greenberg–Hastings Model | 51 |

| 13.1 Greenberg-Hastings Equation......................................................................................................................................... | 51 | |

| 13.2 Explanation......................................................................................................................................................... | 51 | |

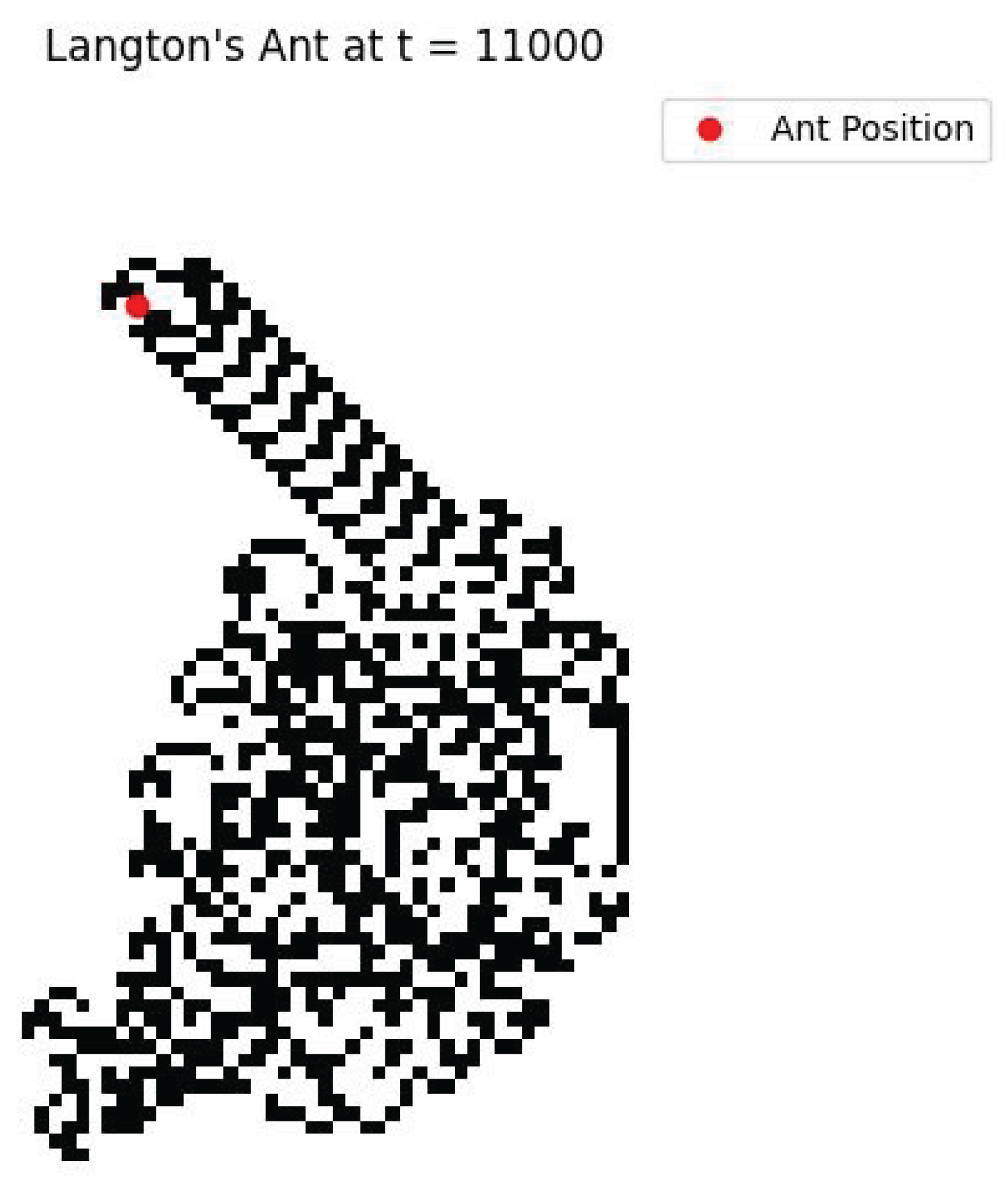

| 14 | The Langton’s Ant | 52 |

| 14.1 The Langton’s Ant Equations....................................................................................................................................... | 52 | |

| 14.2 Observations and Phenomena.......................................................................................................................................... | 52 | |

| 15 | The Discrete Parallel Universe of PDE | 52 |

| 15.1 Motivation.......................................................................................................................................................... | 52 | |

| 15.2 Calculus and Discrete Calculus...................................................................................................................................... | 53 | |

| 15.3 ODE and OΔE........................................................................................................................................................ | 54 | |

| 15.4 Initial and Boundary Conditions..................................................................................................................................... | 54 | |

| 15.5 Laplace Transform and Z Transform................................................................................................................................... | 55 | |

| 15.6 Fourier Transform and Discrete Fourier Transform.................................................................................................................... | 55 | |

| 15.7 Discrete and Continuous Green’s Function.......................................................................................................................... | 56 | |

| 15.8 Gaussian Distribution and Combinatorics............................................................................................................................. | 57 | |

| 15.9 Discrete and Continuous Dynamical Systems........................................................................................................................... | 57 | |

| 15.10 Manifolds and Networks.............................................................................................................................................. | 58 | |

| 15.11 Boolean Algebra, Theoretical Computer Science and Number Theory..................................................................................................... | 59 | |

| 15.12 Summary............................................................................................................................................................. | 59 | |

| 16 | Summary | 59 |

| 16.1 From Numerical Methods to Language of Complexity.................................................................................................................... | 59 | |

| 17 | References | 60 |

Preface

1. Introduction to Partial Difference Equations

1.1. Motivation and Background

1.2. Discrete Function

1.3. Shift Operator

Examples.

1.4. Partial Shift Operator

Examples.

1.5. Ordinary Difference Equations

- is the unknown function defined on ,

- is the shift operator,

- are known coefficient functions,

- is the known input or forcing term,

- and is the total order.

1.6. Partial Difference Equation

- F is a given function, which may be linear or nonlinear;

- denotes the shift operator in the direction, defined by

- is a finite index set determining the set of applied shifts.

1.7. The Order of a Partial Difference Equation

- A shift operator is said to be of order .

- A mixed shift operator is said to be of order .

1.8. Comparison with Ordinary Difference Equations

- Ordinary Difference Equation (OE): Involves a single-variable function , typically evolving along a one-dimensional time axis.

- Partial Difference Equation (PE): Involves a multi-variable function , evolving over a multi-dimensional discrete lattice.

- PE equations utilize partial shift operators, such as , acting independently on each coordinate axis, introducing more geometric and structural complexity.

1.9. Comparison with Partial Differential Equations

- Partial Differential Equations (PDE): Defined over continuous space-time domains. Dynamics are governed by partial derivatives, such as or .

- Partial Difference Equations (PE): Defined over discrete lattice domains, where partial derivatives are replaced by partial difference operators or partial shift operators, e.g. .

- PE capture the dynamics of discrete systems such as cellular automata, lattice models, or numerical schemes, and often exhibit different phenomena such as intrinsic stochasticity or discrete chaos.

1.10. Advantages of Rewriting Complex Systems as Partial Difference Equations

-

Elegant and Unified FrameworkPartial Difference Equations provide a universal and elegant mathematical language to describe a wide range of complex systems. Instead of relying on a fragmented set of ad hoc models, many seemingly unrelated systems can be encoded using the same formalism. This promotes unification across disciplines such as biology, physics, and computer science.

-

Mathematical Rigor and Analytical ToolsBy expressing complex systems through Partial Difference Equations, we enable the use of powerful tools from modern mathematics, including functional analysis, topology, and chaos theory. This increases the precision, clarity, and theoretical strength of the analysis.

-

Extending Modeling ParadigmsMany classical models of complex systems such as Conway’s Game of Life or the sandpile model, are static in the sense that individual entities do not move, and they typically involve only a single scalar field. Reformulating these systems as Partial Difference Equations makes it straightforward to introduce multiple field coupling, or even discrete vector fields to represent additional attributes of the entities, such as phenotypic traits or movement directions. This greatly expands the range of phenomena that can be modeled within the same theoretical framework.

1.11. Scope and Limitations

Future Work.

1.12. Classification and Examples

-

Linear PE: A PE is said to be linear if it is linear in u and all its shifted terms. For example:This equation represents a discrete diffusion process, where the future state is the average of neighbouring spatial values.

-

Nonlinear PE: Nonlinear PE contain nonlinear terms involving u or its shifts. For example:Such systems can exhibit complex behaviour, including chaos and pattern formation.

-

Autonomous PE: If the evolution rule is independent of the explicit time step t, the equation is said to be autonomous:These are time-invariant systems and useful for studying equilibrium dynamics.

-

Non-Autonomous PE: If the update rule explicitly depends on t or x, the system is non-autonomous:These equations are useful for modeling time-varying or spatially heterogeneous environments.

-

System of PE: A coupled system of multiple interacting fields:Such systems arise in biology, physics, and complex networks.

1.13. Notations

2. Linear Partial Difference Equations

2.1. Motivation

2.2. Definition

- is a finite index set,

- is the shift operator in the direction: ,

- and f are known functions on .

- .

- is the shift operator in the direction: ,

- and f are known functions on .

2.3. Discrete 1D Transport Equation

Initial condition:

Interpretation:

Characteristic curve:

Solution

A General Form of Discrete 1D Linear Transport Equation

2.4. Discrete 1D Diffusion Equation

Physical Interpretation.

Special Case

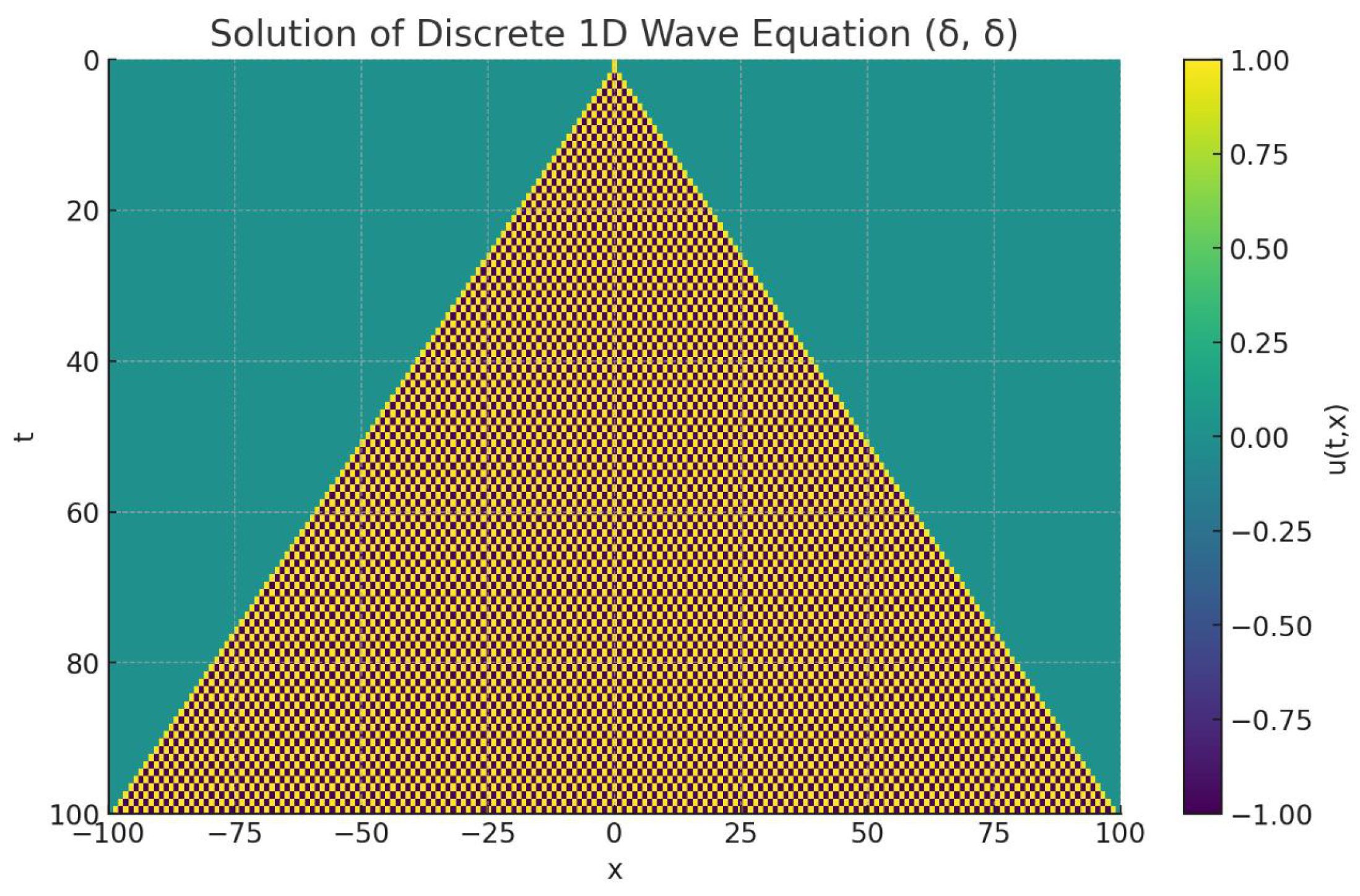

2.5. Discrete 1D Wave Equation

Special Case

Exact Solution:

3. Discrete Function Spaces and Operators

3.1. Motivation

3.2. Discrete Function Spaces

- Conjugate Symmetry:

- Linearity in the First Argument:

- Positive Definiteness:

3.3. Operators

3.4. The Kronecker Delta Function

3.5. The Discrete Green’s Function

3.6. Boundary Value Problems

Dirichlet boundary condition.

Neumann boundary condition.

Robin boundary condition.

4. Elementary Cellular Automata

4.1. Introduction

- It provides a unified mathematical framework to study discrete systems.

- It allows the application of analytical tools such as operator theory, stability analysis, and even Green’s functions.

- It enables the exploration of different types of initial and boundary conditions in a more formalized way.

- It makes it possible to introduce non-autonomous terms and study how external forcing influences the evolution.

4.2. Notation Evolution

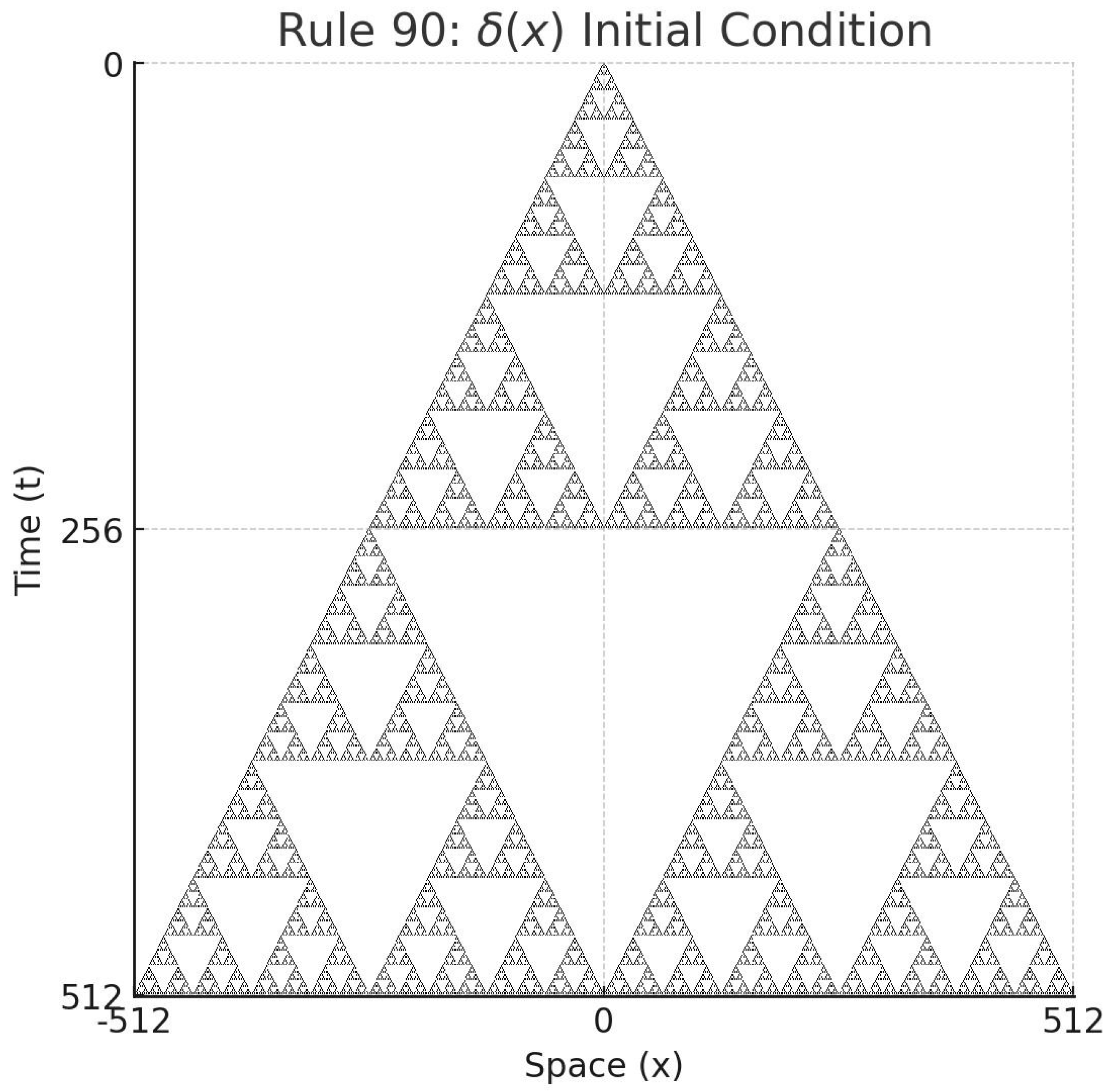

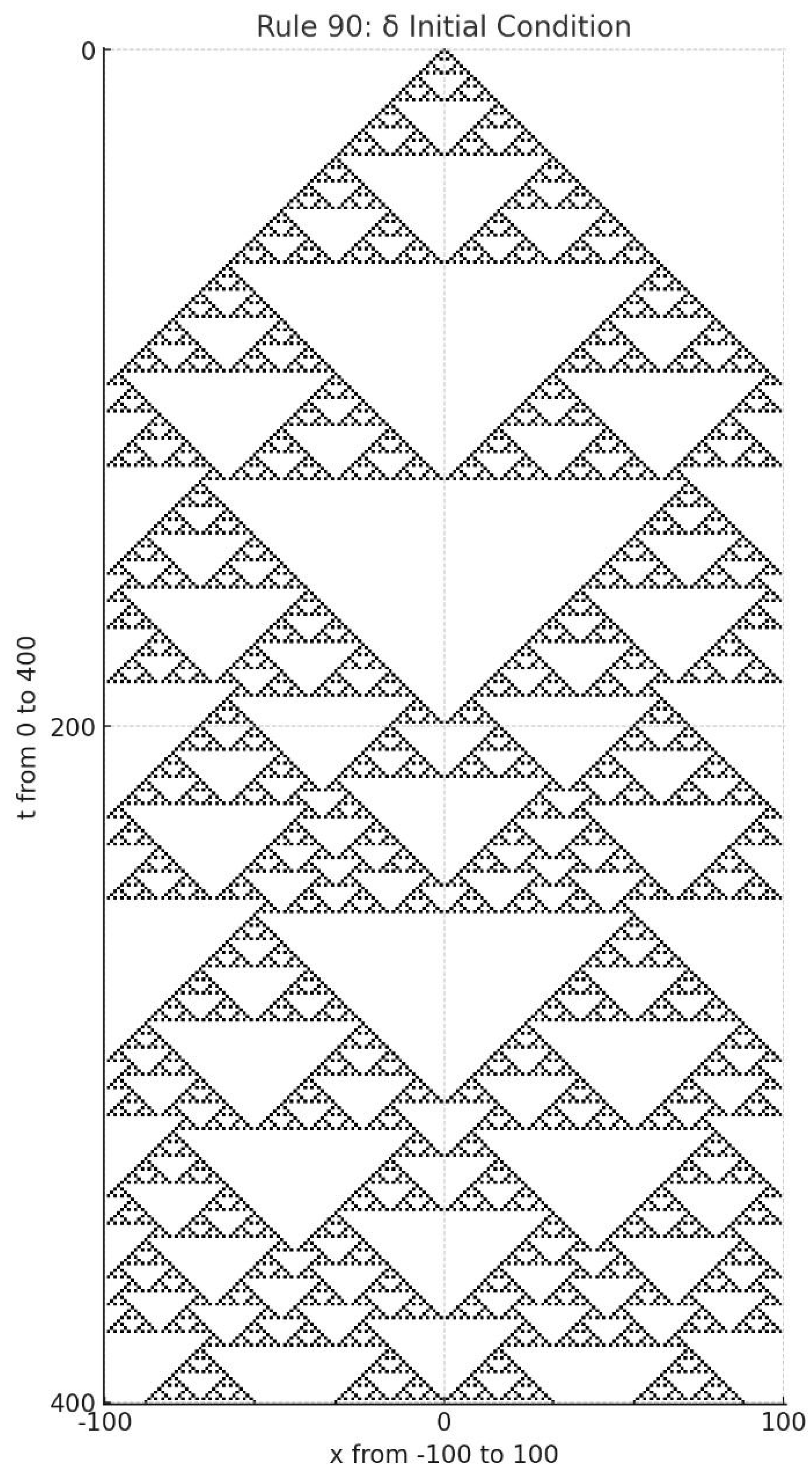

4.3. The Rule 90

Example 1

Example 2

Example 3

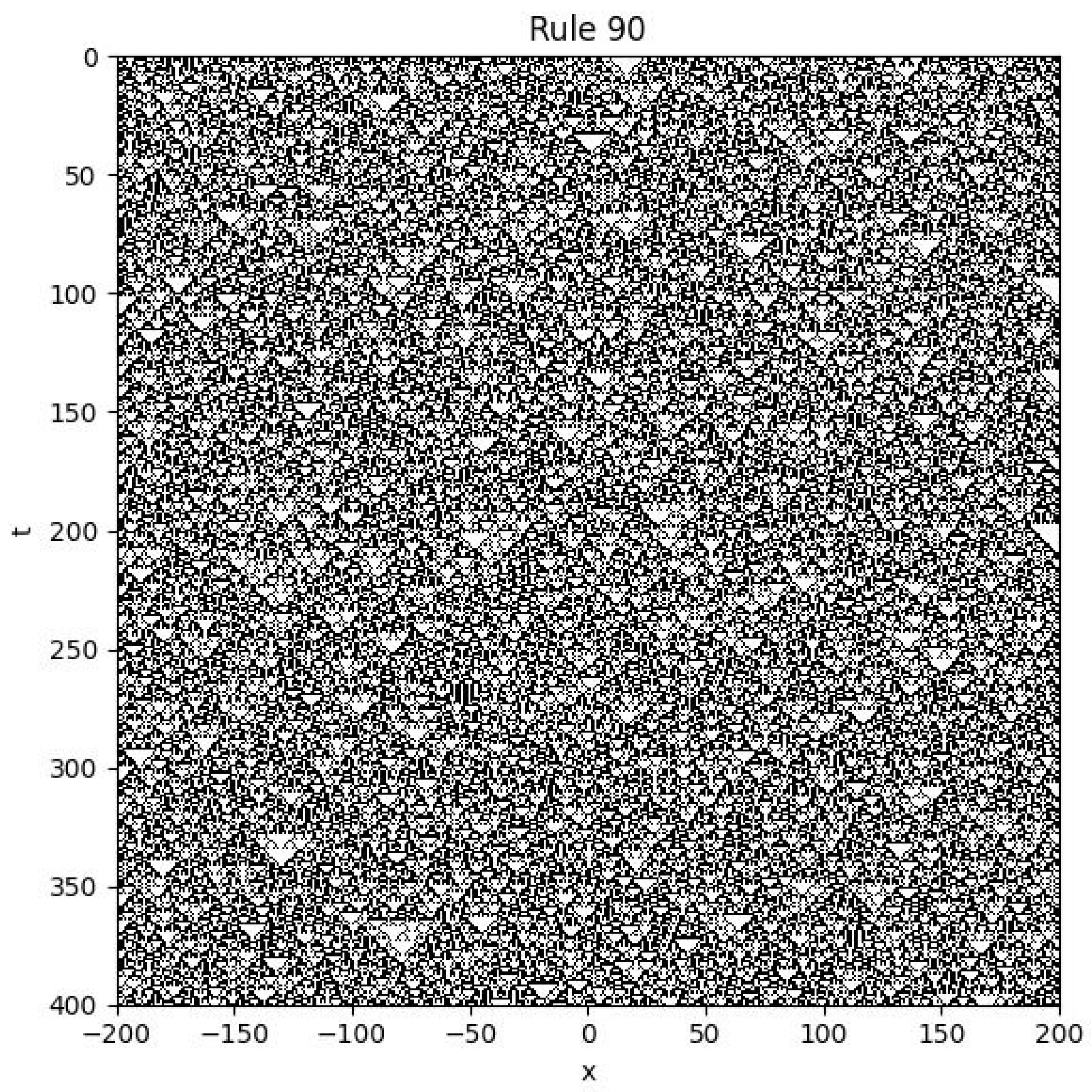

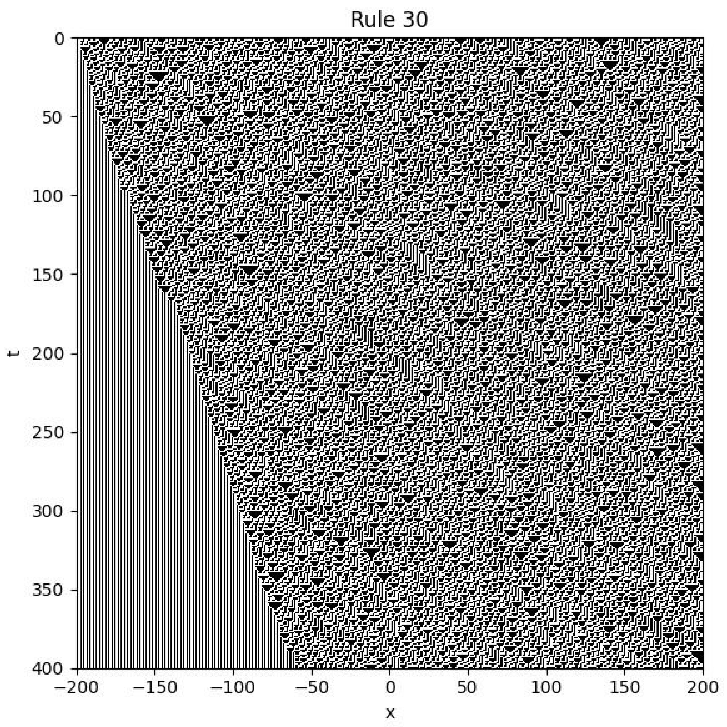

4.4. Rule 30

Example

- Initial condition: is chosen randomly with values in .

- Boundary condition: for all t.

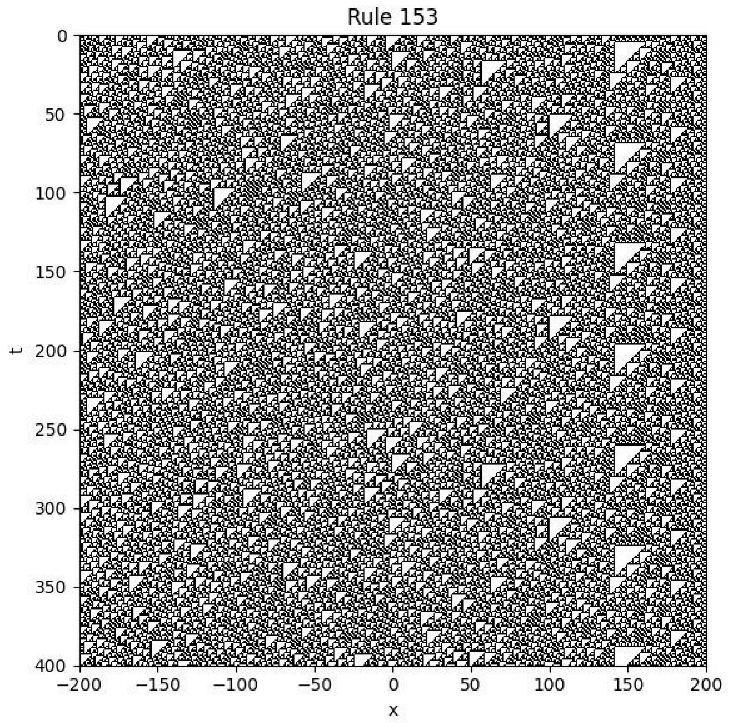

4.5. The Rule 153

Example

- Initial condition: is assigned a random binary value (0 or 1) at each spatial point.

- Boundary condition: for all t.

- Colour scheme: 0 is shown as white, and 1 is shown as black.

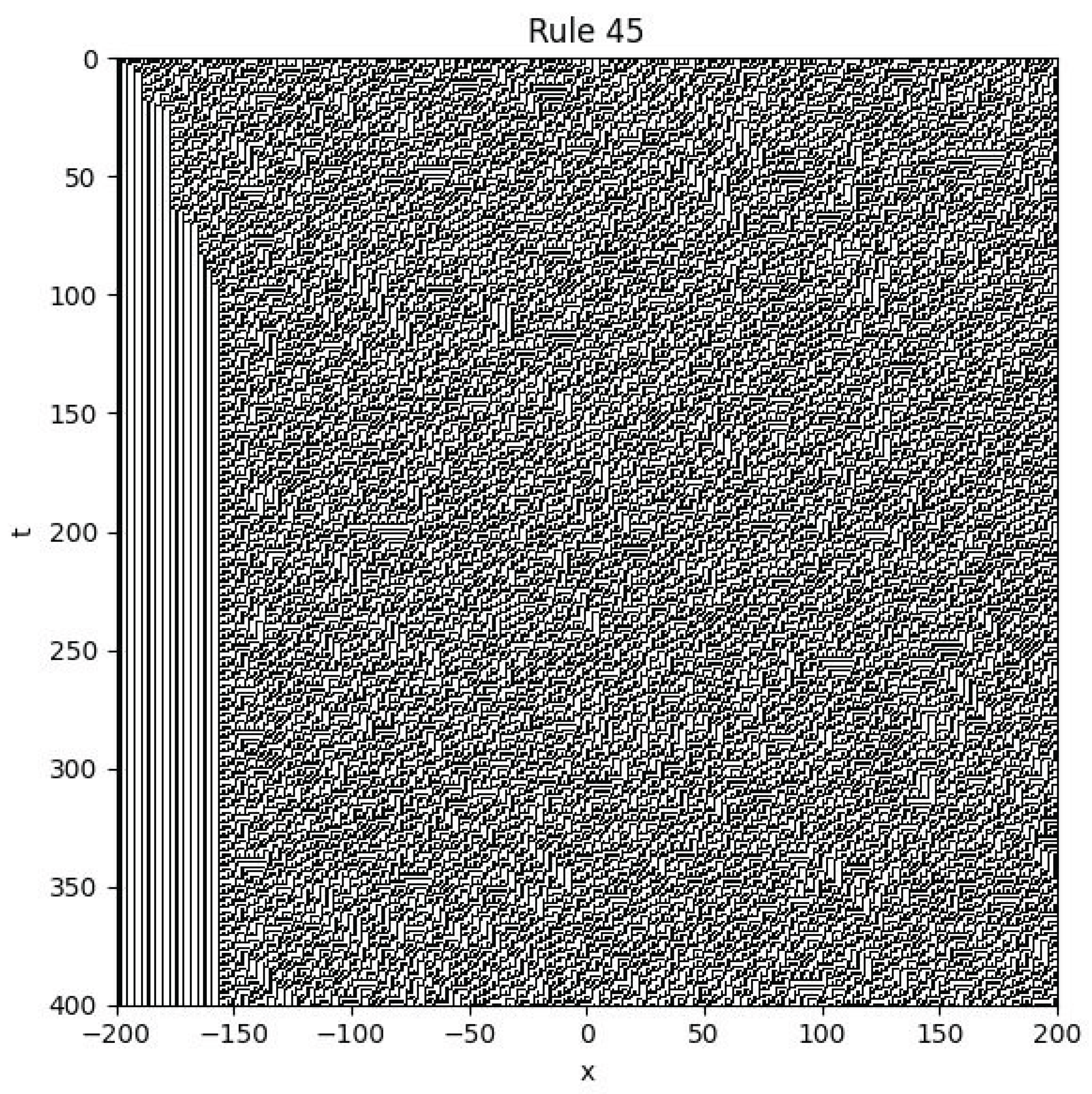

4.6. Rule 45

Example

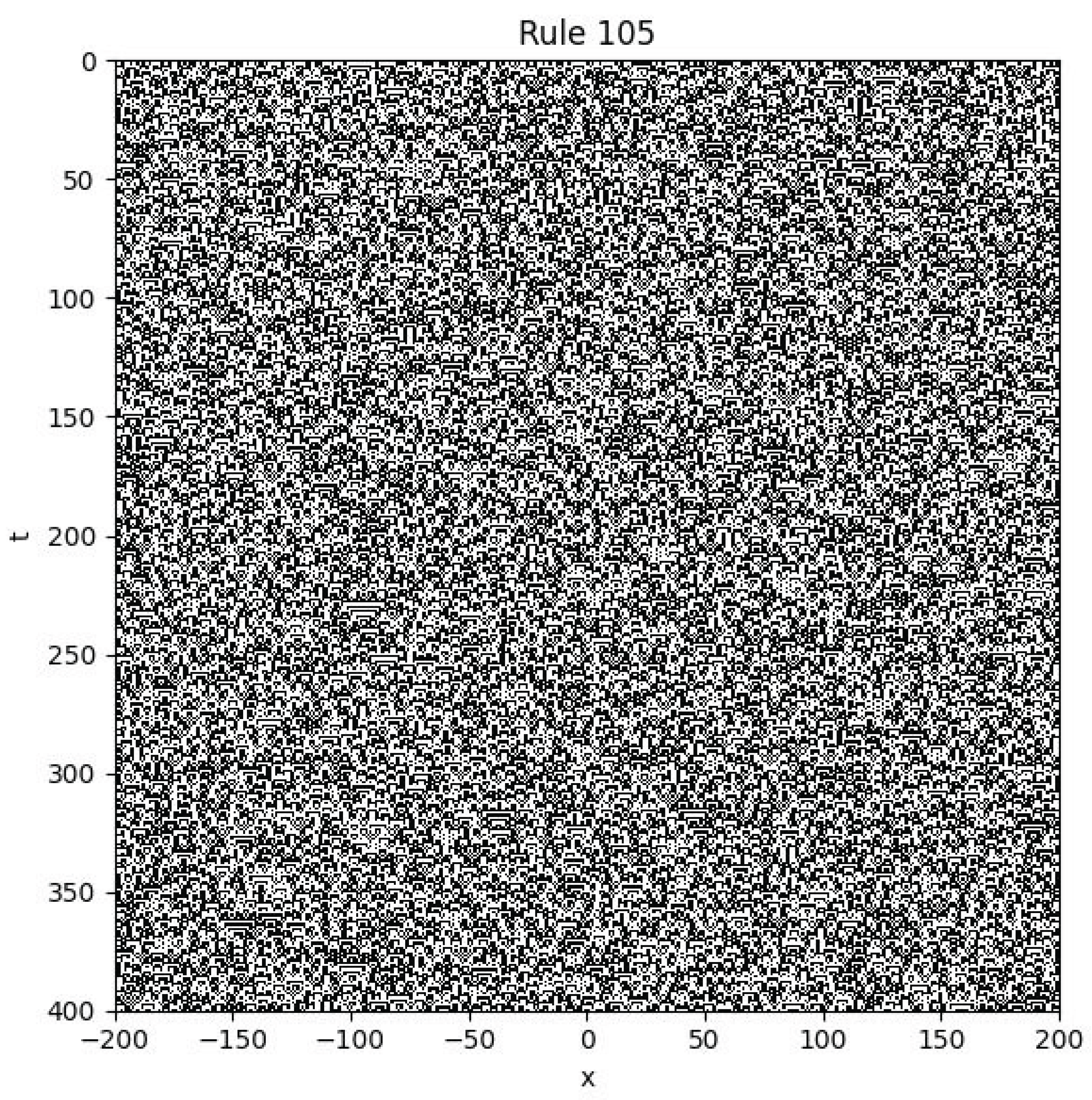

4.7. Rule 105

Example

4.8. Rule 169

Example

4.9. Rule 210

Example

4.10. Rule 137

Example

4.11. Rule 110

Example

- Initial condition: is chosen randomly with values in .

- Boundary condition: for all t.

5. Other 1D Nonlinear Partial Difference Equations

5.1. Introduction

5.2. Sierpinski Fan Equation

5.3. Mod 5 Sierpiński Equation

- is the discrete delta function defined by if , and 0 otherwise;

- for all ;

- The system is updated on a discrete 1D lattice with no boundary condition.

5.4. Mod 4 Sierpinski Fractal Equation

| Value | Colour |

| 0 | White |

| 1 | Green |

| 2 | Purple |

| 3 | Yellow |

6. Coupled Map Lattice

6.1. 1D Coupled Map Lattice

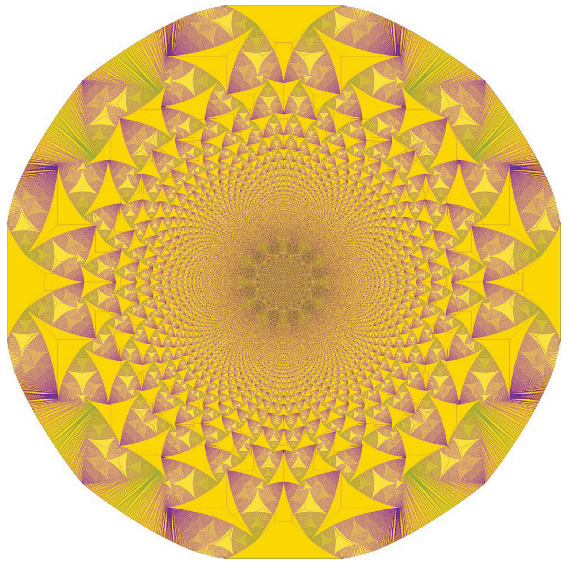

6.2. 2D Coupled Map Lattice

6.3. Explanation

7. The Conway’s Game of Life

7.1. Conway’s Equation

- is the binary state of the cell at time t and position , where 1 denotes "alive" and 0 denotes "dead".

- are the forward shift operators in time and spatial directions, respectively.

- M is the Moore neighbourhood excluding the center, i.e., the set of 8 nearest neighbours:

- is the Kronecker delta function, defined as:

7.2. Interpretation

8. Abelian Sandpile Model

8.1. Abelian Sandpile Equation

- is the Heaviside step function:

- V is the von Neumann neighbourhood:

- is the external forcing term (i.e., the addition of sand grains)

8.2. Remarks

- Emergent fractal patterns

- Scale-invariant avalanches

- Critical behaviour without parameter fine-tuning

8.3. The Sandpile Fractal

8.4. Extended Sandpile Model

- represents the number of sand grains at position and time t,

- is the Heaviside step function,

-

M denotes the Moore neighbourhood:,

- is an external sand input term.

Example

- Initial Condition:

- Boundary Condition: None (infinite or sufficiently large grid with no boundary constraints)

- Forcing Term: (unit sand grain dropped at the center)

8.5. Explanation for the Self-Organized Criticality

- Linear growth phase: Sites far below the threshold evolve smoothly and predictably.

- Chaotic collapse phase: Sites at the threshold trigger avalanches with unpredictable, nonlinear dynamics.

8.6. Explanation for the Power Law Distribution

-

Why are small avalanches more common than large ones?Because the dynamics are based on local interactions, triggering a large avalanche requires a long chain of causally connected sites to be near the threshold, which is statistically less likely. In contrast, small avalanches require only a short chain and are thus much more probable.

-

Why do large avalanches still occur frequently (not exponentially rare)?The collapse dynamics are chaotic: once a critical site topples, small perturbations can lead to unpredictable and explosive cascades, this is the butterfly effect. Therefore, even though rare, large avalanches are possible due to the system’s inherent sensitivity at the critical state.

-

Why is there no characteristic scale in avalanche size?The update rules impose no intrinsic limit on the spatial extent of an avalanche. The avalanche size depends entirely on the current configuration of the system. If a small localized region is near-critical, only a small avalanche occurs. But if a large domain is close to the threshold, a large avalanche may follow. Furthermore, the external driving is random and slow, allowing the system to evolve into configurations where large avalanches are statistically allowed. Thus, the system exhibits scale-invariant behaviour.

9. OFC Earthquake Model

9.1. OFC Earthquake Equation

- represents the local shear stress (or load) at site at time t, .

- denotes the stress at the next time step.

- is the Heaviside function, defined as:

- represents the redistributed stress received from neighbouring sites that have exceeded the failure threshold. is a constant.

- is an external driving term, typically very small, which represents slow tectonic loading. In most implementations, at a randomly selected site and zero elsewhere, modeling slow, local buildup of stress.

9.2. Observations and Phenomena

10. Forest Fire Model

10.1. Forest Fire Equation

10.2. Definitions

-

is the state of the cell at time t and spatial coordinates .

- 0: empty ground (bare land)

- -

- 1: tree

- -

- 2: burning tree

- is the forward time shift operator:

- are spatial shift operators in the Moore neighbourhood M.

- is the Kronecker delta function: if , else 0.

- is the Heaviside step function: if , else 0.

-

is the non-autonomous external driving force:

- -

- : no external change

- -

- : apply one-step growth/fire transition (see below)

10.3. Transition Logic (via mod 3)

- : tree grows on empty land

- : tree catches fire

- : burning tree becomes ash (empty)

10.4. Interpretation

10.5. Observations and Phenomena

- Low density (e.g., 10%): The fire fails to propagate. Due to the sparsity of trees, the flame quickly extinguishes after burning only a few connected trees.

- High density (e.g., 80%): The fire spreads rapidly and extensively. Almost the entire forest is consumed in a short period, with the flame front advancing in a nearly uniform and predictable wave.

- Intermediate density (e.g., around 40%): A highly nontrivial behaviour emerges. The fire propagates in an irregular, branching manner, forming a complex fractal-like structure. The fire path becomes winding, unpredictable, and sensitive to small variations in the initial configuration.

11. Kuramoto Firefly Model

11.1. Kuramoto Equation

- is the phase at grid point and time t.

- is a fixed intrinsic frequency assigned randomly to each point.

- K is the coupling constant. In our simulations, we choose .

- M is the Moore neighbourhood:

11.2. Principle of Locality

11.3. Observations and Phenomena

- The system exhibits topological defects: points around which the phase (colour) continuously wraps from 0 to .

-

These defects appear in pairs, with opposite rotational direction:

- -

- One clockwise

- -

- One counterclockwise

- When these defects move and eventually annihilate each other, a large region of synchronization emerges suddenly.

- Phase synchronization phenomena

- Topological vortex dynamics

- Pattern formation and self-organization

12. Ising Model

12.1. Governing Equation

- V is the von Neumann neighbourhood.

- is the binary state at discrete time t and spatial coordinate .

- is the next time step value.

- is a random driving field at site , drawn from a normal distribution centered at , where T is the temperature and k is a constant.

- is a small positive number (baseline activation threshold).

- is a larger threshold required for flipping a stable site.

- J is the coupling constant determining interaction strength between neighbouring sites.

12.2. Physical Interpretation

- The first term activates when the site’s current state is different from the local neighbourhood majority (), allowing it to flip easily when .

- The second term activates when the site’s current state matches the neighbourhood majority, but may still flip if the driving force exceeds a higher threshold , modeling thermal noise or instability.

13. Greenberg–Hastings Model

13.1. Greenberg-Hastings Equation

- , a discrete function defined on space-time: .

- is the Heaviside step function.

- is the Kronecker delta function.

- is the modulo-n operation.

- is the number of discrete states (typically ).

- is the excitation threshold.

- N is the set of relative spatial coordinates in the neighbourhood (e.g., von Neumann or Moore).

13.2. Explanation

14. The Langton’s Ant

14.1. The Langton’s Ant Equations

- is the state of the lattice at time t and position , i.e., .

- is the direction of the ant at time t, where .

- is the location of the ant, with .

- The modulo function is defined as: .

- One partial difference equation for the lattice state .

- Three ordinary difference equations for the ant’s direction and position: , , and .

14.2. Observations and Phenomena

15. The Discrete Parallel Universe of PDE

15.1. Motivation

15.2. Calculus and Discrete Calculus

15.3. ODE and OE

15.4. Initial and Boundary Conditions

- Dirichlet condition: Specifies the value of the function at the boundary.

- Neumann condition: Specifies the value of the normal derivative at the boundary.

- Robin condition: Specifies a linear combination of the function and its derivative at the boundary.

- Discrete Dirichlet condition: Specifies function values on the boundary nodes.

- Discrete Neumann condition: Specifies discrete gradients (differences) at the boundary.

- Discrete Robin condition: Specifies a linear relation between function value and difference at the boundary.

15.5. Laplace Transform and Z Transform

15.6. Fourier Transform and Discrete Fourier Transform

Fourier Series (Continuous, Periodic)

Fourier Transform (Continuous, Aperiodic)

Discrete Fourier Series

Discrete Fourier Transform (DFT)

15.7. Discrete and Continuous Green’s Function

15.8. Gaussian Distribution and Combinatorics

15.9. Discrete and Continuous Dynamical Systems

Continuous Dynamical Systems.

Discrete Dynamical Systems.

Fractals and Complexity.

- Rule 90 cellular automaton generates the Sierpiński triangle.

- The Abelian Sandpile Model exhibits discrete self-organized criticality with fractal avalanche clusters.

- Coupled Map Lattices generate chaotic spatial patterns with complex attractors.

15.10. Manifolds and Networks

15.11. Boolean Algebra, Theoretical Computer Science and Number Theory

15.12. Summary

16. Summary

16.1. From Numerical Methods to Language of Complexity

References

- Murray, J. Mathematical Biology: I. An Introduction, third ed.; Vol. 17, Interdisciplinary Applied Mathematics, Springer-Verlag: New York, Berlin, Heidelberg, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Murray, J. Mathematical Biology II: Spatial Models and Biomedical Applications, third ed.; Vol. 18, Interdisciplinary Applied Mathematics, Springer-Verlag: New York, Berlin, Heidelberg, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Bak, P.; Tang, C.; Wiesenfeld, K. Self-Organized Criticality: An Explanation of 1/f Noise. Physical Review Letters 1987, 59, 381–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnston, N.; Greene, D. Conway’s Game of Life: Mathematics and Construction; Self-published, 2022; p. 492. Hardcover, colour printing; US letter size (8. [CrossRef]

- Elaydi, S. An Introduction to Difference Equations, 3rd ed.; Undergraduate Texts in Mathematics, Springer: New York, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Olver, P.J. Introduction to Partial Differential Equations; Undergraduate Texts in Mathematics, Springer: Cham, Heidelberg, New York, Dordrecht, London, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfram, S. A New Kind of Science, 1st ed.; Wolfram Media: Champaign, Illinois, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Itoh, M.; Chua, L.O. Difference Equations for Cellular Automata. International Journal of Bifurcation and Chaos 2009, 19, 805–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanagita, T.; Kaneko, K. Coupled map lattice model for convection. Physics Letters A 1993, 175, 415–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.Q.; Wang, S.J. Self-Organized Criticality in an Anisotropic Earthquake Model. Communications in Theoretical Physics 2018, 69, 280–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Li, N.; Chen, D.; Chen, G.; Sun, C.; Shi, M.; Gao, X.; Wang, K.; Hezam, I.M. A Forest Fire Prediction Model Based on Cellular Automata and Machine Learning. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 55389–55403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strogatz, S.H. From Kuramoto to Crawford: Exploring the Onset of Synchronization in Populations of Coupled Oscillators. Physica D: Nonlinear Phenomena 2000, 143, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.P. The Ising Model: Brief Introduction and Its Application. In Solid State Physics; IntechOpen, 2020. CC BY 3. [CrossRef]

- Wu, A.C.; Xu, X.J.; Wang, Y.H. Excitable Greenberg-Hastings cellular automaton model on scale-free networks. arXiv preprint cond-mat/0701248, 0701. [Google Scholar]

- Boon, J.P. Langton’s Ant as an Elementary Turing Machine. In Nonequilibrium Thermodynamics and Fluctuation Kinetics; Springer, Cham, 2022; Vol. 208, Fundamental Theories of Physics, pp. 135–140. [CrossRef]

- Mariconda, C.; Tonolo, A. Discrete Calculus: Methods for Counting; Vol. 103, UNITEXT - La Matematica per il 3+2, Springer International Publishing: Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adkins, W.A.; Davidson, M.G. Ordinary Differential Equations; Undergraduate Texts in Mathematics, Springer, 2012.

- Mutagi, R.N. Understanding the Discrete Fourier Transform. PDF lecture notes, 04. Uploaded by the author on ResearchGate, Indus University. 20 January.

- Brin, M.; Stuck, G. Introduction to Dynamical Systems, 1st ed.; Cambridge University Press, 2002. Graduate-level introduction to dynamical systems theory; Cambridge, 1st ed.

- Petersen, P. Riemannian Geometry, 3rd ed.; Vol. 171, Graduate Texts in Mathematics, Springer, Cham, 2016. [CrossRef]

- Devadoss, S.L.; O’Rourke, J. Discrete and Computational Geometry, 1st ed.; Princeton University Press, 2011.

- Discrete Mathematics and Its Applications, Chapman & (Ed.) Handbook of Discrete and Computational Geometry, 3rd ed.; Discrete Mathematics and Its Applications, Chapman & (Ed.) Hall/CRC: Boca Raton, FL, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rendell, P. Game of Life Turing Machine. In Turing Machine Universality of the Game of Life; Adamatzky, A.; Martínez, G.J., Eds.; Springer International Publishing, Cham, 2016; Vol. 18, Emergence, Complexity and Computation, pp. 45–70. [CrossRef]

- Rosen, K.H. (Ed.) Handbook of Discrete and Combinatorial Mathematics, 2nd ed.; Discrete Mathematics and Its Applications, Chapman & Hall/CRC, 2017; p. 1612. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).