1. Introduction

Breast cancer is one of the leading causes of mortality among women across the globe. According to data reported by WHO in 2022, approximately 2.3 million women around the world were diagnosed with breast cancer, out of which 670,000 of them lost their lives [

1]. One of the major causes behind such a high number is late-stage diagnosis, which leads to the disease already progressing to advanced stages where treatment options are limited. Hence, there is an urgent need to develop an automated, efficient, cost-effective, and objective diagnostic tool to identify the breast cancer subtype. This is crucial since it enables the physicians to provide an effective treatment plan, ultimately improving the patient’s survival rate.

Traditionally, breast cancer is diagnosed by utilizing histopathological examination [

2,

3,

4,

5], where tissue samples are analyzed by the pathologist under a microscope and classify whether the tumors are benign or malignant. Similarly, other common diagnostic techniques that are employed include mammography [

6,

7,

8], ultrasound [

9,

10,

11], magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) [

12], and biopsy-based histopathology [

13,

14]. All of these techniques have shown their effectiveness in diagnosing breast cancer. However, each of them has some shortcomings. Mammography-based breast cancer screening can result in false positives or negatives for women with dense breast tissue. Ultrasound and MRI-based diagnostic techniques are very effective; however, their dependence on a skilled operator has resulted in them becoming expensive and inaccessible in resource-limited settings. Though biopsy-based histopathology is considered a gold standard in breast cancer, it is labor-intensive and prone to inter-observer variability, which can result in inconsistent diagnoses among pathologists. Given all the challenges associated with each of the techniques, it is crucial to have a reliable, cost-effective, and automated diagnostic approach that can reduce dependency on humans, which is also accessible to women across the world. All of this can be achieved through artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML). By applying these advanced techniques and deep learning on the histopathological images, human dependence on diagnosing or classifying the cancer type can be reduced, while improving the accuracy of the diagnosis.

Many studies have been done on applying deep learning models to classify breast cancer using histopathological images, mammograms, and ultrasound scans. For example, convolutional neural networks (CNNs) are widely used in binary classification to distinguish between benign and malignant tumors. In [

15], deep learning-based computer-aided diagnosis (CAD) systems for mammographic mass lesion classification significantly enhance diagnostic accuracy by 98.94% and reduce reliance on unnecessary biopsies. Similarly, in another study, CNN-based classification was applied to the mini-MIAS database, consisting of mammographic images, and achieved an impressive accuracy of 89.05% and sensitivity of 90.63% [

16]. Transfer learning is another technique where pretrained deep learning architectures, such as VGG16, Inception, and ResNet, have shown remarkable accuracy in automating breast cancer detection in mammographic and histopathological images [

17,

18,

19]. For example, Saber et al. [

17] showed that through transfer learning, such as VSG16 and ResNet50, breast cancer can be diagnosed using mammographic images at an impressive accuracy of 98.96%. Another study by Shahidi et al. [

19] showed that using pre-processing, data augmentation, and model selection, the performance of transfer learning like ResNeXt and SENet can be improved for breast cancer classification.

Though these advancements in deep learning models have significant leaps in breast cancer diagnosis, most of the existing studies mainly focus on binary classification (benign vs. malignant) rather than differentiating specific histopathological subtypes. Breast cancer is a heterogeneous disease; hence, it has multiple subtypes, each of which requires its own treatment. However, researchers have conducted limited work using deep learning models to do a multi-class classification of breast cancer subtypes with histopathological images. Due to this research gap, it is essential to study the ability of CNN-based deep learning architectures, such as ResNet, to classify multiple histopathological subtypes of breast cancer. Hence, in this work, we are examining the ResNet architecture to perform multi-class classification of breast cancer subtypes using histopathological images. Moreover, in this work, we are employing ResNet-18, ResNet-34, and ResNet-50 models to evaluate their performance in distinguishing eight different tumor subtypes from the BreaKHis dataset [

20] at multiple magnifications (40X, 100X, 200X, and 400X). By analyzing the effectiveness of these deep learning models, this study will advance the current efforts to automate histopathological classification, which will eventually reduce diagnostic subjectivity and improve the accuracy of breast cancer subtype identification.

The remainder of the paper is organized in the following order: Section II discusses the relevant studies conducted with the BreakHis dataset. Section III follows Section II, which presents the methodology utilized in the work to examine the performance of various ResNET models. After that comes Section IV, the results section, where various metrics will be used to evaluate the performance of various ResNET models. Then, we will conclude by describing the implications of the studies and their effect on breast cancer diagnosis and potential directions for future research.

2. Relevant Work

In this study, we are utilizing the BreaKHis dataset, which has been widely used as a benchmark for testing AI based models in breast cancer diagnosis [

20]. The dataset consists of 7,909 histopathological images from 82 patients, which are categorized into benign and malignant tumors. Each of these categories is further divided into four subtypes. Additionally, the dataset magnifies each image into four different levels, including 40X, 100X, 200X, and 400X, making the deep learning model better trained on varying image resolutions. Various studies have been done using the BreaKHis dataset to apply ML and AI models for diagnosing breast cancer.

2.1. Machine Learning Techniques

The initial research work done in BreaKHis dataset in diagnosing breast cancer included utilizing traditional machine learning techniques to classify the histopathological images. For this purpose, handcrafted feature extraction was done first, followed by applying classifiers such as Support Vector Machines (SVMs), k-nearest Neighbors (k-NN), Decision Trees, and Random Forests. For instance, in [

21], Alqudah et al. utilized sliding window-based feature extraction using Local Binary Pattern (LBP) features, where they divided each image into 25 sliding windows for localized feature extraction. These extracted features are then utilized to train a Support Vector Machine (SVM) classifier, which achieved an impressive accuracy of 91.2%. Another study by [

22] extracted features that included color, Gabor filter, and GLCM descriptors, which were later utilized to train a Weighted K-Nearest Neighbors (Weighted K-NN) to classify the histopathological images. The proposed method in [

22] achieved classification accuracies of 90% at 40X, 100X, and 200X magnifications, and 89.6% at 400X, demonstrating its potential in supporting breast cancer histopathology analysis. A similar study by Murtaza et al. in [

23] trained decision tree model using BreaKHis dataset and fine-tuned on the Bioimaging Challenge 2015 dataset. Using a misclassification reduction algorithm, they achieved a classification accuracy ranging from 87.5% to 100% across four breast tumor subtypes. All these traditional machine learning techniques have shown promise. However, they have limitations due to their overreliance on feature extraction. Hence, these conventional machine learning techniques are unable to capture complex patterns inherent in histopathological images.

2.2. Deep Learning Models for Binary Classification

Similarly, earlier work on applying deep learning models on the BreaKHis dataset focused primarily on binary classification using CNNs. These models focused only on differentiating between benign and malignant tumors. Araújo et al. in [

24] trained a CNN model using the BreaKHis dataset to achieve an accuracy of 83.3% across each magnification. Similarly, in another work by Spanhol et al., a patch-based CNN model was utilized for feature extraction and classification that achieved an accuracy of 85.6% at 200X magnification [

20]. All these works underscore the potential of deep learning models to learn hierarchical features from histopathological images automatically.

2.3. Transfer Learning and Model Optimization

The use of deep learning on the BreakHis dataset was further advanced by Bayramoglu et al. through the combined use of CNN with transfer learning, resulting in the accuracy further improving to 87.3% at 400X magnification [

25].

A further advancement in the breast cancer classification between the benign and malignant tumors was done through a hybrid between CNN and Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) under federated learning, resulting in achieving an accuracy of 93% [

26]. A similar hybrid technique is utilized by Kaddes et al. in [

27] to achieve an enhanced impressive accuracy of 99.90%. Besides the hybrid technique, various deep learning techniques that included ResNeXt-50, DPN131, and DenseNet-169 were utilized for classifying the binary cancer type that showed an impressive accuracy of 99.5% [

28]. All this shows the impact and progress made in distinguishing benign from malignant tumors due to the advancement in deep learning.

However, even when the AI presents a strong case of its potential in breast cancer diagnostics through binary classification, this is not sufficient for capturing the full heterogeneity of breast cancer [

29]. Since breast cancer consists of multiple histopathological subtypes, developing a multi-class classification type is essential to ensure the patient can get the proper treatment plan.

2.4. Deep Learning Models for Multi-Class Classification

Though binary classification in breast cancer research using deep learning is showing great promise and potential, it is not sufficient since subtype classification is essential for personalized treatment. For this purpose, multi-class classification of histopathological subtypes of breast cancer is a necessity. In the BreakHis dataset, there are eight classes in which images are categorized, including Adenosis (A), Ductal carcinoma (DC), Fibroadenoma (F), Lobular carcinoma (LC), Mucinous Carcinoma (MC), Papillary Carcinoma (PC), Phyllodes Tumor (PT), and Tubular Adenoma (TA). Some research work done in this direction was also included by Umer et al., where they proposed a six-branch deep convolutional neural network (6B-Net) with feature fusion and selection mechanisms for multi-class breast cancer classification [

30]. When this model was applied to the BreakHis dataset to classify the histopathological images into eight breast cancer classes, an accuracy of 90.10% was achieved. Another research work adopted a DenseNet121 based deep learning model that was able to achieve an average accuracy of 92.50% [

31].

The BreaKHis dataset enables advancing AI-driven breast cancer diagnosis, resulting in significant progress in binary and multi-class classification tasks. The traditional machine learning model, though not very accurate, provided the groundwork for integrating advanced deep learning models to improve the accuracy of the classification accuracy further. Though the use of deep learning, transfer learning, and model optimization have significantly improved the accuracy of binary classification, much of the work still needs to be done in multi-class classification. The complexity and heterogeneity of breast cancer make it a necessity to further advancement in the multi-class classification that enables precise and personalized treatment planning.

3. Dataset and Preprocessing

3.1. BreaKHis Dataset

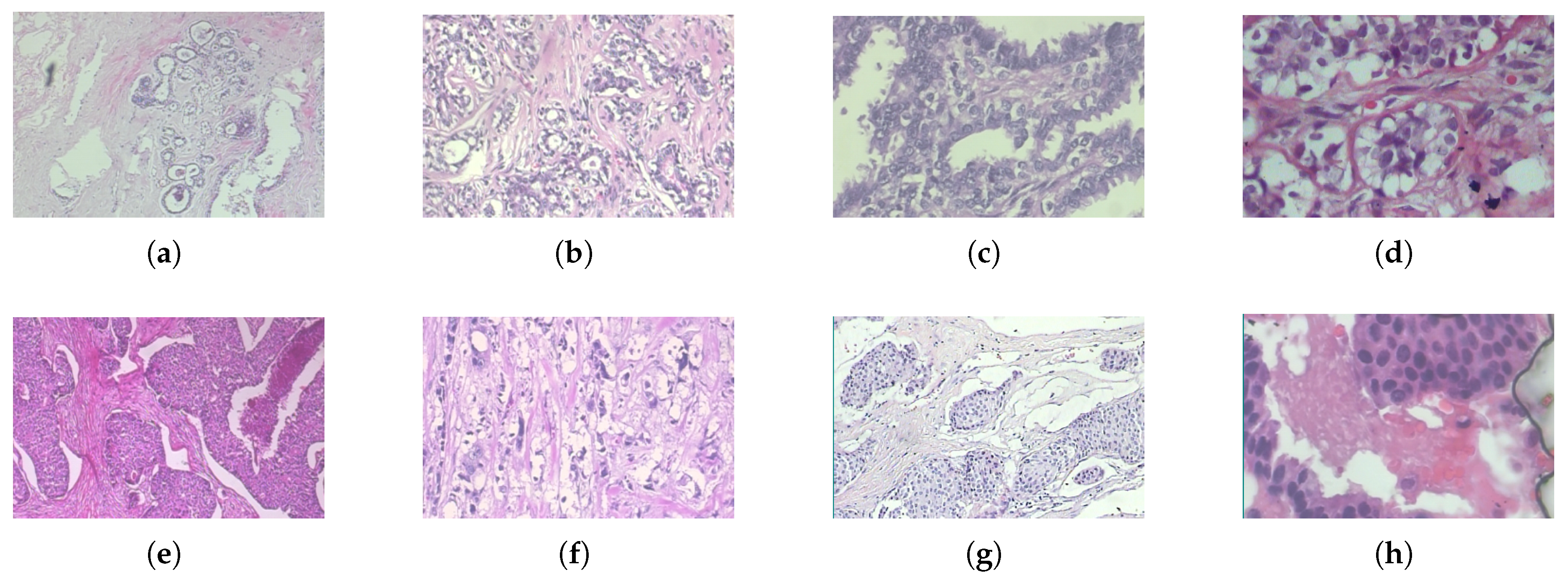

The BreaKHis dataset is publicly available [

20] consisting of histopathological breast cancer images widely used for benchmarking machine learning and deep learning models for breast cancer classification. The dataset has a collection of 7,909 microscopic images obtained from 82 different patients. Each of the images in the dataset corresponds to a breast tumor specimen extracted through biopsy procedures as shown in

Figure 1. Additionally, each of the images in the dataset is in four different magnification levels (40X, 100X, 200X, and 400X) to capture tissue structures at varying resolutions, enabling multi-scale feature learning as shown in

Table 1. The low magnification levels (40X, 100X) are ideal for the broader tissue morphology, whereas the higher magnifications (200X, 400X) offer detailed cellular structures, which are crucial for deep learning models to differentiate tumor subtypes.

Each tumor sample in the dataset is further classified into four different subcategories for both benign and malignant, as shown in

Table 2. For oncology, precise information regarding the varied growth patterns, aggressiveness, and treatment responses in different cancer types is vital, which can only be achieved through multi-class classification. Given the dataset is imbalanced where the malignant cases significantly outnumber benign cases. Hence data processing and augmentation are essential to train and build a robust model.

3.2. Preprocessing and Augmentation

For applying deep learning models for image classification of histopathological preprocessing, it is essential for the model to effectively learn discriminative features while mitigating variations in staining techniques, imaging conditions, and tissue structures. A robust preprocessing pipeline is especially necessary for the BreaKHis dataset since the images in the dataset are of varying resolutions, intensity distributions, and orientations.

3.2.1. Image Resizing

As discussed earlier, the BreaKHis dataset consists of images in different magnification levels (40X, 100X, 200X, and 400X), leading to variations in spatial resolution. Deep learning models such as CNNs require input images to be of uniform size for batch processing. Hence, to ensure uniformity and compatibility with pretrained architectures such as ResNet, all the images are resized to a standard resolution of 224 x 224 pixels. The resizing operation of the images will maintain spatial consistency across different magnifications, reduce computational overhead, and ensure compatibility with ImageNet-pretrained models. Though the resizing of images will cause a loss of fine-grained cellular details, the use of deep feature extraction layers in ResNet architecture compensates for this loss by capturing hierarchical spatial information.

3.2.2. Normalization

The next step in preparing the dataset for training and testing of dataset is normalization. This step is crucial for deep learning since it standardizes the image’s intensity distributions, stabilizing training and improving model convergence. Among various techniques, in this work, mean-variance normalization was applied to scale pixel values to a zero mean, unit-variance distribution:

where,

is the normalized image,

I represent the original pixel intensity,

is the dataset-wide mean, and

is the standard deviation. This transformation of all the images ensures a reduction of the variability that staining differences in histopathological slides may have introduced and ensures a consistent input distribution.

3.3. Data Splitting Strategy

To train ResNet models and later evaluate them, we split the dataset randomly into three subsets that include 80% of images for training, 10% for validation, and the remaining 10% for testing. The use of a random split ensures that each subset contains a diverse representation of the eight breast cancer subtypes. This ensures that the trained model can able to generalize well across unseen samples. In this work, stratified sampling was not used due to the multi-class nature of the classification task; instead, random shuffling was performed prior to splitting to ensure variability across sets.

3.4. Data Augmentation

The data augmentation technique is applied when the dataset consists of a limited number of images; hence, in this technique, the training dataset is expanded artificially by applying a series of transformations to improve the model’s robustness and generalization. This technique is appropriate since the BreakHis dataset has limited histopathological images. The data augmentation technique introduces variations in image orientation and appearance while preserving the essential structural patterns required for classification, reducing the possibility of overfitting. Hence, in this work, the augmentation technique was applied through PyTorch transforms pipeline:

3.4.1. Random Horizontal Flipping

Histopathological slides can exhibit variations in tissue orientation due to the preparation and orientation processes. Hence, to prevent potential biases arising from these positional differences, random orientation flipping is employed. In this work, random flipping of images with a probability of 50% is applied. This ensures that the model is not biased towards a particular tissue orientation.

3.4.2. Random Rotation ()

Random rotation of images within the range of ±10° is applied to account for the possible variation in slide position under the microscope.

where (

x,

y) represents the original pixel coordinates, (

,

) represents the rotated coordinates after transformation, and

is the randomly selected rotation angle between -10° and +10°.

3.5. Handling Class Imbalance

The BreakHis dataset consists of the malignant tumor samples significantly outnumbering benign ones which can result in the deep learning model being biased towards the majority class. Hence, in this work, instead of applying the popular class balancing techniques such as oversampling, undersampling, or weighted loss functions, we applied random shuffling.

4. Methodology

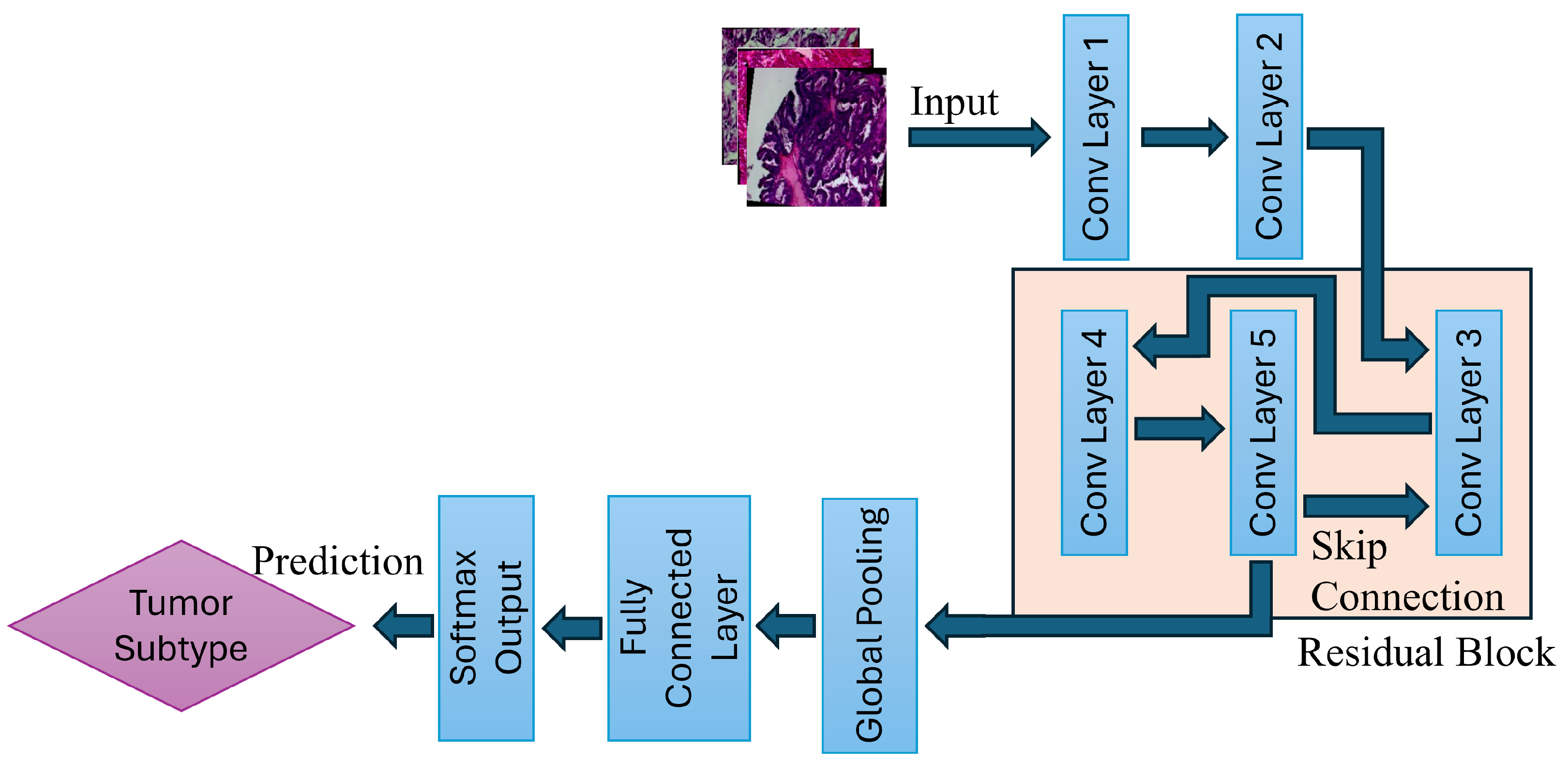

This study proposes an automated deep learning based classification framework leveraging Residual Networks (ResNet-18, ResNet-34, and ResNet-50) to classify eight distinct tumor subtypes. The model architecture built in this study is designed in such a way that can able to efficiently extract and learn hierarchical feature representations, enabling multi-class classification with high accuracy. The methodology employed in this study consists of multiple stages, including data acquisition, model architecture, training strategy, and evaluation.

4.1. Overview of the Proposed Model

The proposed deep-learning framework follows a structured pipeline that begins with image acquisition of BreaKHis dataset, followed by preprocessing and augmentation that includes image resizing, normalization, random horizontal flipping, and random rotations. After all these processes, the processed dataset is fed into the ResNet-based CNN architecture for classification. The ResNet model employed in this work then does convolutional feature extraction, residual learning, and fully connected classification layers, which allow for accurate differentiation between eight breast tumor subtypes as shown in

Figure 2.

4.2. Deep Residual Networks (ResNet) for Tumor Classification

By addressing the vanishing gradient problem, the ResNet has revolutionized deep learning applications in image classification. Traditional CNN models are very capable techniques for various applications; however, as the architecture grows in depth, the signal that guides the network’s learning process dwindles to near insignificance during backpropagation. This makes the learning process ineffective, eventually making the network incapable of effectively refining its parameters. ResNet rectifies this issue through the use of a skip connection, as shown in

Figure 2.

The output of a residual block is computed as:

where,

x is the input to the residual block,

is residual function learning by the network, and

W represents the weight matrices of convolutional layers.

This can be expanded further into a two-layer residual block, the transformation is defined as:

where

and

are the convolutional weight matrices. The

and

are the bias terms.

4.2.1. ResNet Architecture

This work implemented three variations of ResNet to evaluate the network depths in classifying the various breast cancer classes, including ResNet-18, ResNet-34, and ResNet-50. Each of these architectures is different in terms of the number of layers and computational efficiency, as shown in

Table 3. The ResNet-18 and ResNet-34 use a basic residual block consisting of two 3 x 3 convolutional layers per block. Whereas, the ResNet-50 incorporates bottleneck residual blocks, where each block consists of three convolutional layers (1×1, 3×3, 1×1 convolutions). The bottleneck residual block reduces the amount of computations while maintaining a superior feature extraction.

4.3. Model Training Process

The training process of the ResNet deep learning model follows a structured pipeline, which ensures an efficient feature extraction and residual learning ideal for multi-class breast tumor subtype identification. The training mechanism is based on mini-batch processing, back propagation, and optimization using Adam optimization.

Each image first goes through the preprocessing and augmentation, after which all are fed into the ResNet models. All images are then passed through multiple convolution processes where hierarchical features from the images are extracted. The early stage captures low level features that includes edges and textures, while deeper layers learn high-level tumor structures. Then comes the residual learning mechanism in ResNet which is critical for stable gradient propagation through skip connections, which mitigates the vanishing gradient problem, as shown in

Figure 2.

4.3.1. Forward Propagation

- 1.

Input Image Processing:

Each of the images will go through normalization and resizing prior to entering the neural network.

- 2.

Convolutional Feature Extraction:

As presented in

Figure 2, the first two convolution layers extract spatial features such as edges, textures, and cell morphology. These are computed using:

where,

is the input feature map,

represents the input image pixels and

is the convolution kernel.

- 3.

Residual Learning via Skip Connections:

The residual block allows the gradient to flow smoothly and efficiently through the network, which eventually helps in preventing the vanishing gradient problem. This is achieved by adding skip connections that bypass one or more layers, enabling the network to learn identity mappings. The skip gradient is representation is shown in equation

3 and equation

4, respectively.

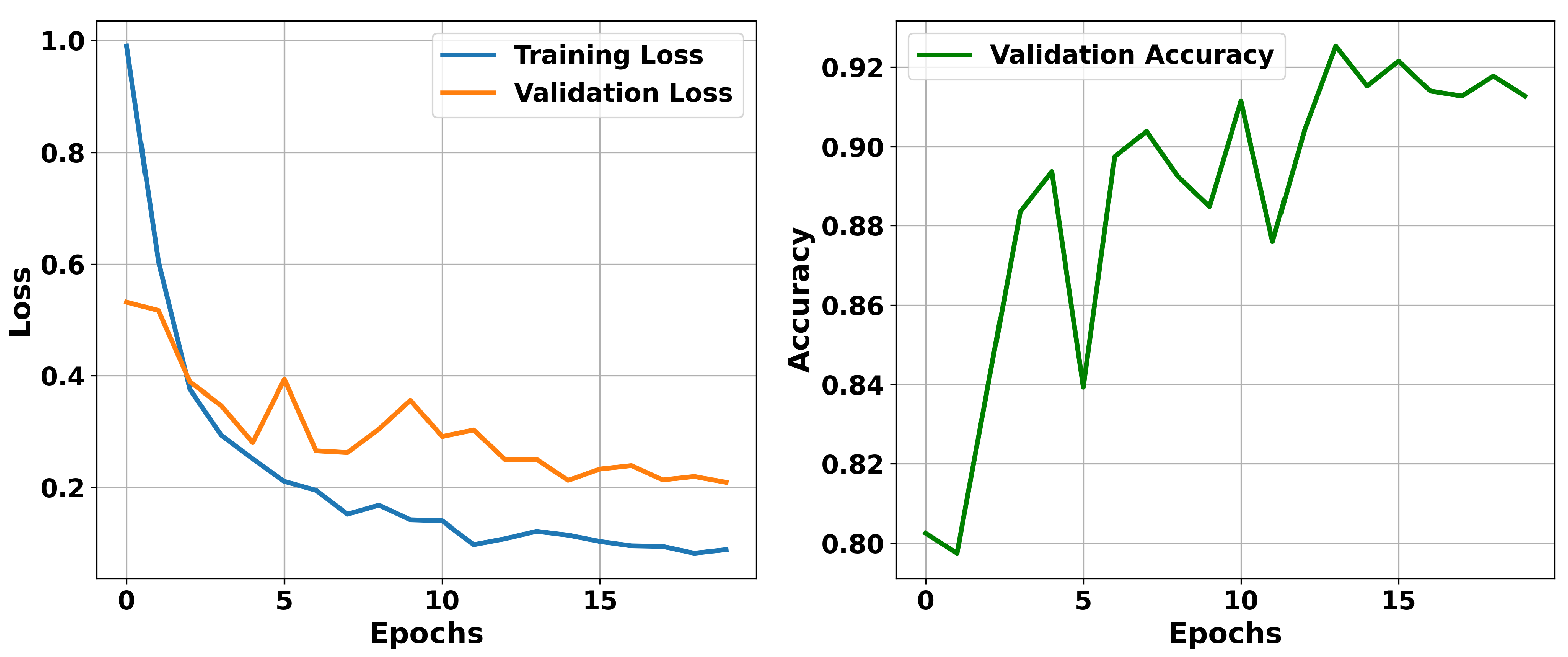

5. Results and Analysis

In this section, we evaluate three deep learning models, ResNet-18, ResNet-34, and ResNet-50, to determine their performance when classifying breast cancer subtypes. We utilize multiple performance metrics such as accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score for a well-rounded assessment. Additionally, graphical tools such as loss curves, confusion matrix, ROC curves, and Precision-Recall (PR) curves were employed to provide comprehensive insights into the model’s training dynamics, predictive behavior, and class-wise performance across multiple evaluation dimensions.

5.1. Model Training Dynamics and Convergence

Among all the ResNet models utilized in this study, ResNet-50, when run over 20 epochs, performed superior. The validation accuracy in ResNet-50 improved from 80.25% in the initial epoch to 92.53%. A similar steady decline in validation loss is seen from 0.5319 to 0.2130, as shown in

Figure 3. Except for the brief fluctuation around the epochs 4 and 6, a continuous increase in the improvement in the accuracy. Overall, the accuracy and validation loss show that the model effectively learned to discriminate features from the training data, while avoiding overfitting.

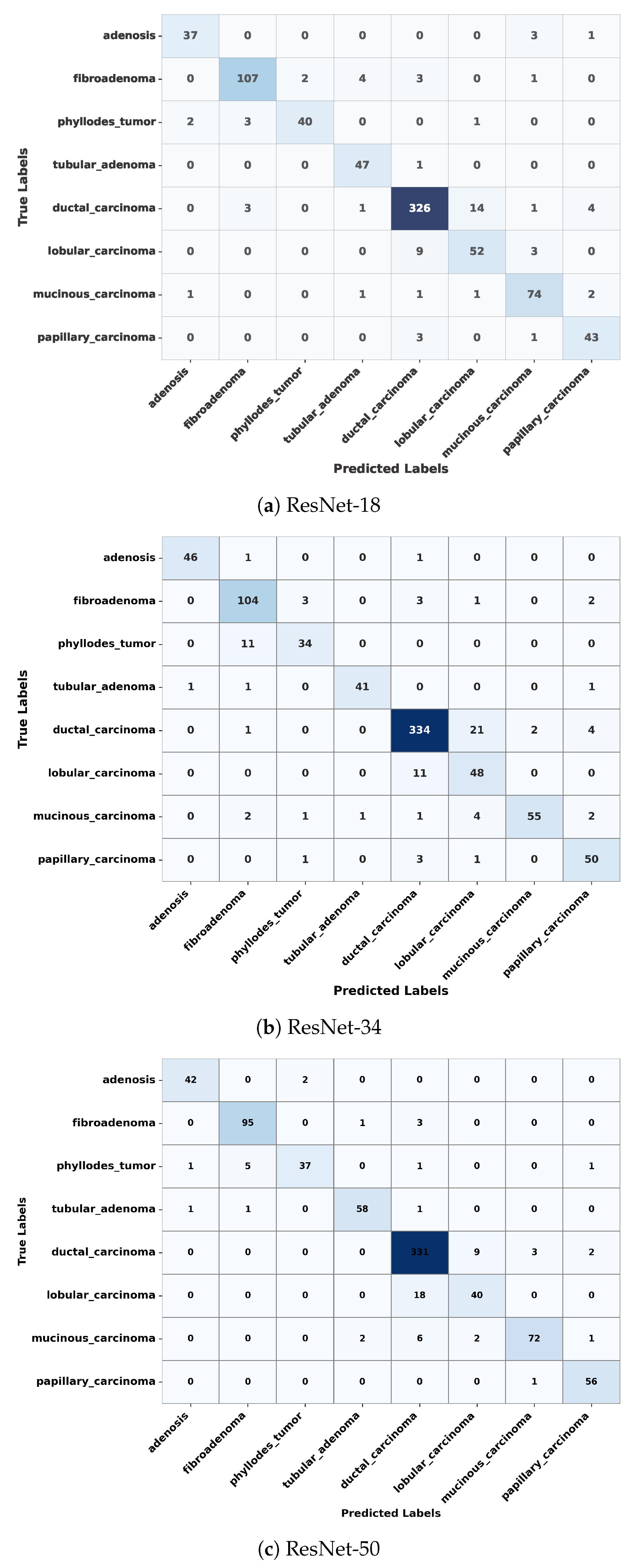

5.2. Confusion Matrix Analysis

In this section, we will examine the strengths and residual weaknesses of the trained ResNet model in prediction ability on the test set across subtypes using a confusion matrix. In this section, we will examine the strengths and residual weaknesses of the trained ResNet model in prediction ability on the test set across subtypes using a confusion matrix. The confusion matrix for ResNet-18, ResNet-34, and ResNet-50 is shown in

Figure 4. The diagonal dominance indicates high accuracy across most of the classes. The three confusion matrices shown in

Figure 4 depict that the ResNet model in all three categories was able to achieve exceptional performance in classifying ductal carcinoma, adenosis, fibroadenoma, and tubular adenoma. However, the model still confuses between some of the classes, such as lobular carcinoma and mucinous carcinoma, as well as between phyllodes tumor and fibroadenoma, as shown in

Figure 4. These misclassifications might have resulted from inherent visual similarities in tissue architecture patterns and morphology among these subtypes. Such confusion can be minimized through the use of a balanced dataset in which each of the subclasses is adequately represented, thus allowing the model to learn distinctive and discriminative features.

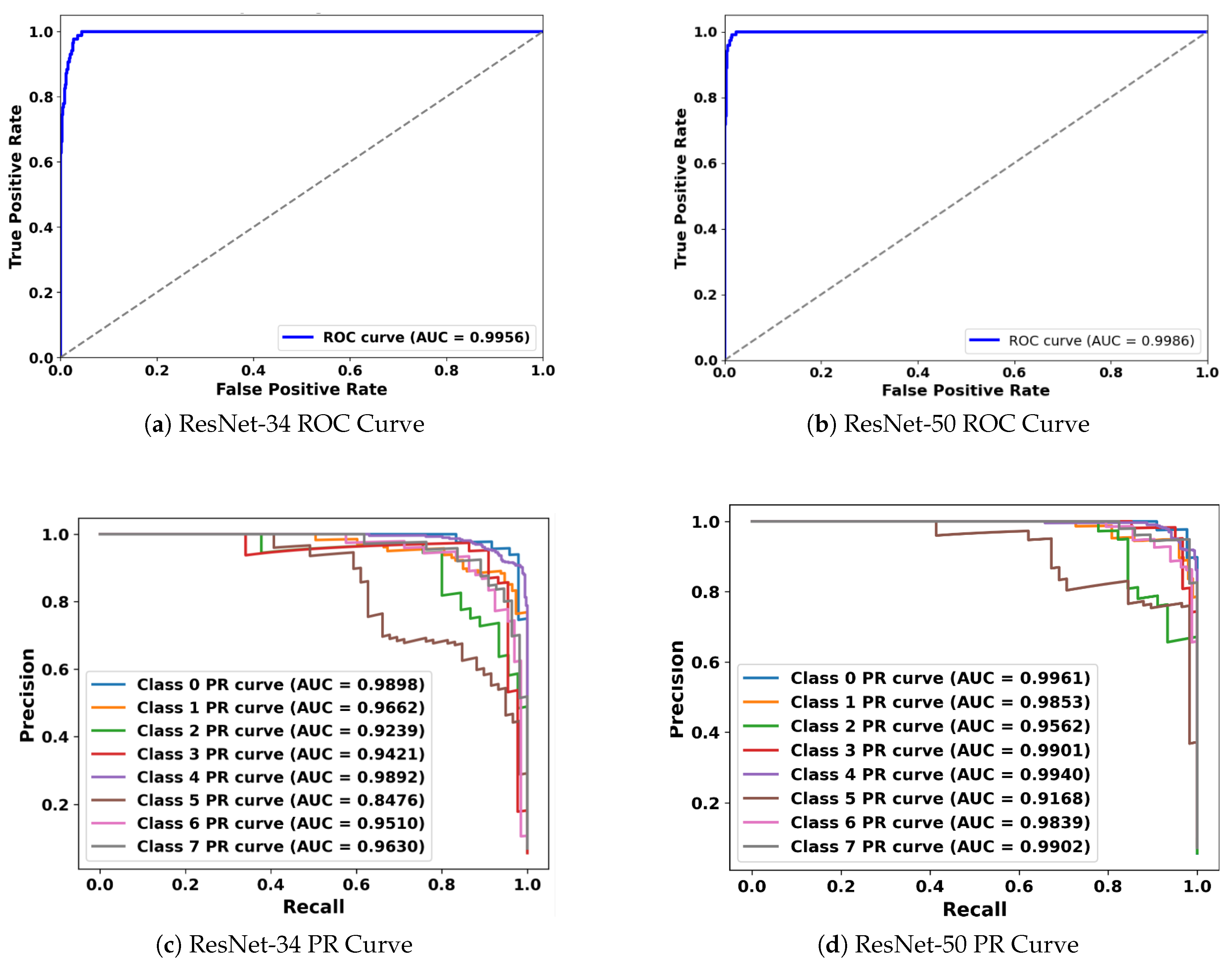

5.3. Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) and Precision-Recall (PR) Curve Analysis

In medical image classification tasks, especially for diseases like cancer, it is essential not only to achieve high overall accuracy but also to rigorously evaluate how well the model distinguishes between different classes. It becomes even more crucial when the dataset is imbalanced or where the cost of false positives and false negatives varies significantly. The ROC curve serves this purpose as it plots the True Positive Rate (Sensitivity) against the False Positive Rate (Specificity) at various decision thresholds. The primary metric derived from the ROC curve is the Area Under the Curve (AUC), which summarizes the model’s ability to correctly classify positive and negative instances across all thresholds. An AUC score of 1.0 means perfect classification, whereas a value of 0.5 implies no discriminative power, which is equivalent to random guessing. In this study, ROC curves for the ResNet-34 and ResNet-50 demonstrate that both models maintain high true positives while maintaining a low false positive across various decision thresholds, as shown in

Figure 5. The AUC for the ResNet-50 is 0.9979, signifying near-perfect classification capability across the eight breast tumor classes. Similarly, for the ResNet-34, the AUC is 0.995, indicating exceptional discriminative performance as well. This high AUC for both the ResNet models highlights the capabilities of each of them in separating tumor classes with minimal overlap in their predictive probabilities.

Though the ROC curve provides valuable insights, it can sometimes give an overly optimistic view in imbalanced datasets, which can result in favoring the dominant classes and reducing performance with the minority classes. In such cases, the Precision-Recall (PR) curve becomes a more appropriate tool. Typically, in a PR curve, Precision (Positive Predictive Value) is plotted against Recall (Sensitivity), explicitly focusing on the performance for the positive class while ignoring the true negatives, which dominate in imbalanced scenarios. The summary metrics that are utilized for the PR curve are Area Under the Precision-Recall Curve (PR-AUC). Hence, the PR-AUC measures the model’s ability to correctly identify positive instances while minimizing the false positives. This becomes crucial when it is important for cases where detecting rare classes has significant consequences. The PR curves for the ResNet-34 and ResNet-50, across each of the 8 tumor classes, are shown in

Figure 5. ResNet-34 shows pretty strong PR-AUC values for all the tumor subtypes, ranging from 0.85 to 0.9898. The lowest PR-AUC is observed for class 5 (Lobular Carcinoma), either due to lower representation or high similarity with other classes. Similarly, for ResNet-50, the PR-AUC is even more robust, achieving AUCs above 0.91 and many of the classes going beyond 0.99. Hence, it shows that the ResNet-50 consistently maintains both high precision and recall across tumor classes, even when the dataset is imbalanced.

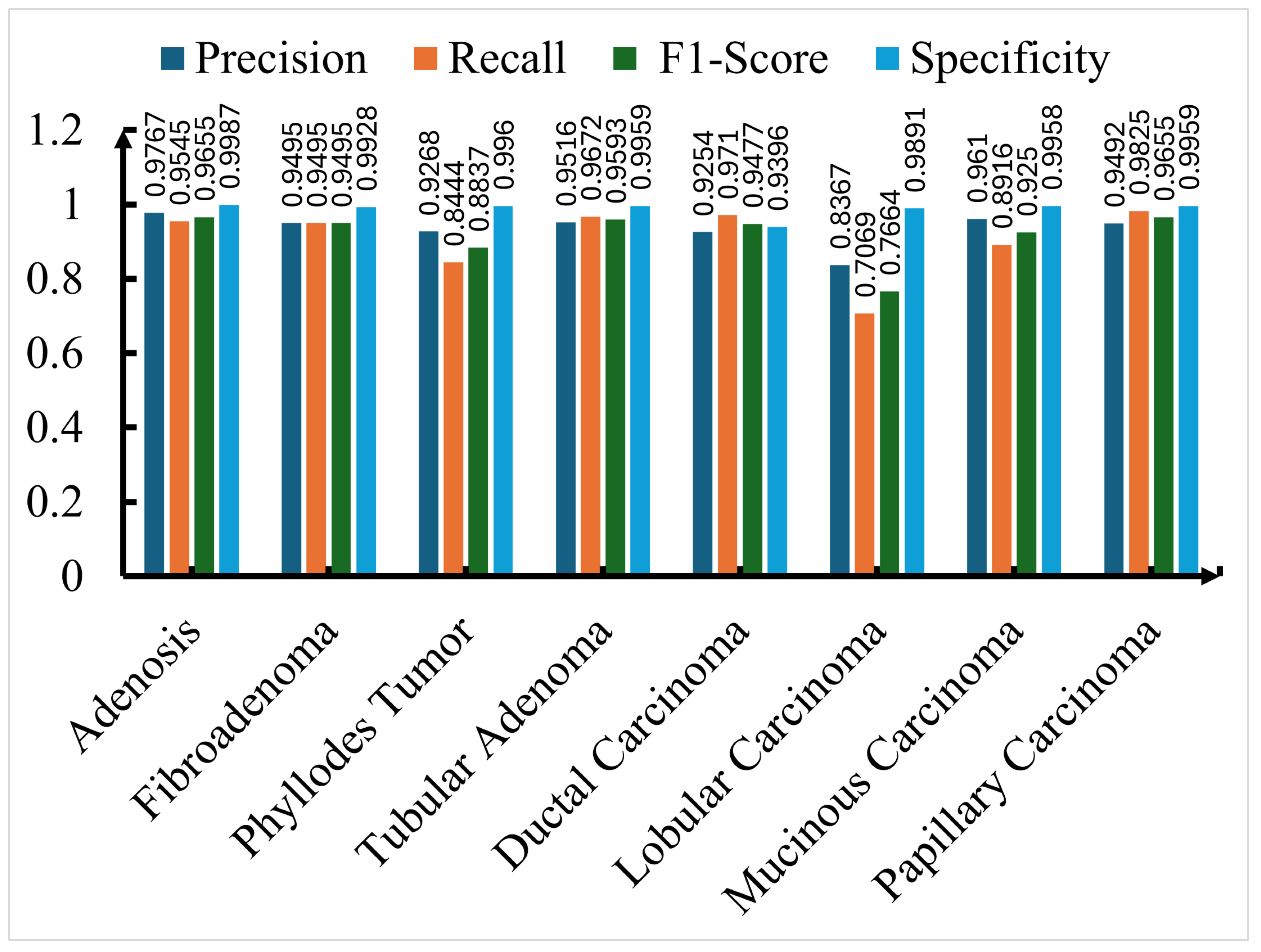

5.4. Class-wise Performance Metrics and Detailed Analysis

For a comprehensive understanding of the model’s performance besides overall accuracy, we utilized four critical metrics that include precision, recall, F1-score, and specificity. All of the metrics allow a thorough assessment of how well the model performs in identifying each of the breast cancer subtypes present in the BreaKHis dataset. Of all of these metrics, precision reflects the proportion of samples that were identified as positive among all of them that were positively predicted. Precision is important in medical diagnosis, where a high precision score means a low false positive that can result in minimizing unnecessary treatments or invasive procedures. Similarly, recall measures the ability of the model to identify all the true positives within each sample in a given class. A high recall score ensures that all the actual cancer cases in a clinical setting are diagnosed. In an imbalanced dataset, the F1-score plays a vital role in providing a model’s completeness in identifying positive cases. Since F1-score represents a harmonic mean of precision and recall, it provides a score for both the accuracy of positive predictions and the model’s completeness in identifying positive cases. In the end, specificity reflects the ratio of correctly identified negative cases, thereby ensuring that the model does not raise false alarms while identifying the non-cancerous or different subtype cases.

Though all three ResNet models received an impressive performance in all four metrics, the evaluation of the ResNet-50, since it is superior compared to the rest, is shown in

Figure 6. Precision for each of the seven breast cancer classes was more than 93%, except for the lobular carcinoma. For the same class, lobular carcinoma, F1-score, and recall are under 78% likely due to the subtle visual differences with other subtypes, or due to fewer training samples. Except for the lobular carcinoma, the model exhibits superior performance compared to other subtypes. For instance, adenosis achieved the highest performance in each of the categories, including precision of 0.9767, recall of 0.9545, and F1-score of 0.9655, showing the trained models’ exceptional ability in identifying adenosis with minimal misclassifications. Similar to adenosis, tabular adenoma, fibroadenoma, and papillary carcinoma also showed superior scores in precision, recall, and F1-score. The model achieved an impressive score of 0.9710 and 0.9477 in recall and F1-score, respectively, in Dactual carcinoma, one of the most prevalent and clinically significant subtypes in malignant tumors. This shows that the trained model can play a pivotal role in detecting this critical class with minimal false negatives, as shown in

Figure 6. Besides the precision, recall, and F-1 score, the model consistently achieved high specificity, such that in each of the subtypes, it got a score of more than 0.92. In some cases, such as adenosis, tubular adenoma, and papillary carcinoma, the specificity score approach nears perfect scores. This shows that the trained ResNet-50 model has the ability to minimize false-positive predictions, which is an essential characteristic in clinical applications.

To measure the impact and effectiveness of the proposed ResNet model, it is crucial to compare it with existing published work that also utilized the BreaKHis dataset and applied multi-class classification on breast tumor subtypes. This comparison is presented in

Table 4, where the proposed technique is shown to achieve a superior accuracy compared to previously reported methods that achieved accuracies ranging from 73.68% to 91.3%. In the previous work, various techniques such as traditional CNNs, Inception V3, or attention-based networks like ECSAnet, are being employed. In most of the techniques shown in

Table 4, the dataset was split in an 80:20 ratio for the train and test split. In some of the cases, it was split into a train, test, and validation set. For uniformity, the validation and test divisions are combined into one category. This comparison clearly shows the robustness and practical potential of the proposed model in automating breast cancer subtype classification in clinical pathology.

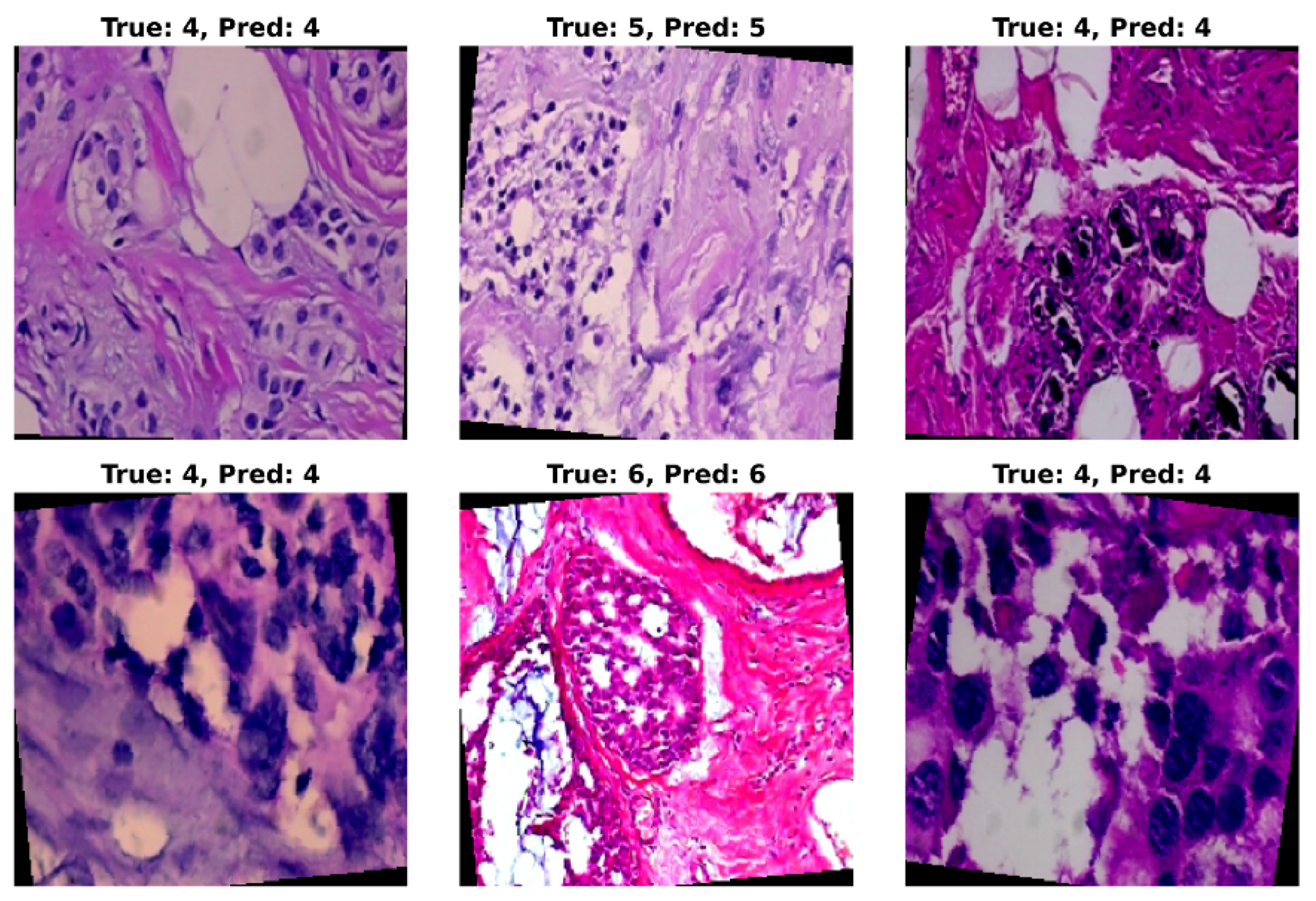

5.5. Visual Assessment of Model Predictions

Through quantitative metrics, we were able to showcase the effectiveness of the ResNet model in classifying breast cancer into 8 subclasses. To complement the numerical results, a visual inspection of the trained model’s prediction ability provides valuable insights into the classification performance. For this purpose, randomly selected test set images were applied as input to the model, and the predicted classification was then compared with the original class label. A grid of six histopathological images from the BreaKHis test set from various breast cancer subtypes and magnification levels was provided as input to the trained ResNet-50 model. The model’s predictions (Pred), alongside the true class labels (True), are shown in

Figure 7. In

Figure 7, True class 4 represents ductal carcinoma, class 5 is for lobular carcinoma, and class 6 corresponds to mucinous carcinoma. In this figure, most of the prediction on the test sample is shown to be correct. However, on some occasions, misclassification may occur when the subtypes exhibit subtle morphological similarities.

6. Discussion

This work presents the potential of deep learning models, such as the ResNet architecture, to achieve a challenging task of multi-class classification of breast cancer subtypes from histopathological images. Among the ResNet-18, ResNet-34, and ResNet-50, the latter outperformed in all the metrics and parameters such as accuracy, AUC, ROC, precision, recall, F1-score, and specificity. This superior performance can largely be attributed to the deeper architecture of ResNet-50, specifically its bottleneck residual blocks, which enable the extraction of complex, fine-grained histopathological features essential for differentiating between visually similar subtypes. The model performed much better in classifying the subtypes, such as ductal carcinoma, adenosis, fibroadenoma, and tubular adenoma. Even though the model did better compared to other published work in classifying lobular carcinoma and mucinous carcinoma, its performance for these subtypes was still not as strong as for others, likely due to the subtle morphological differences among these subtypes and their under-representation within the dataset. Hence, due to these observations, more future research is necessary where more advanced data augmentation strategies, subtype-specific learning approaches, and more balanced datasets are used to improve the classification of challenging subtypes.

Additionally, in a recent work done using an ensemble of Swin Transformer models, BreaST-Net, on the BreakHis dataset, was able to achieve a higher accuracy of 96% test accuracy across eight subtypes (at 40× magnification) [

36]. However, some of the metrics used in the model presented in this work were in terms of performance. Similarly, Joseph et al., by combining a hybrid method of handcrafted feature extraction technique and deep neural network (DNN) classifier, achieve an accuracy of 97.89% for multi-class classification of breast cancer subtypes on the same dataset [

37]. Likewise, Chikkala et al. proposed a novel Bidirectional Recurrent Neural Network (BRNN) framework that integrates a ResNet-50-based transfer learning backbone, Gated Recurrent Units (GRU), residual collaborative branches, and a feature fusion module to do multi-class classification on the BreakHis dataset, which achieved an accuracy of 97.25% [

38]. Sharma et al. used the VGG16 pre-trained network with a linear SVM classifier on the BreakHis dataset, showing an accuracy that was a little better than the ResNet-50 model proposed in this work [

39]. All these recent publications highlight that by incorporating advanced architecture, such as transformers or recurrent neural networks, or using hybrid learning approaches that integrate handcrafted features, the multiclassification of breast cancer could be achieved. While these models achieve slightly higher accuracy than the ResNet-50 model presented in this study, they often require more complex architectures or additional training resources. Additionally, the integration of explainable AI (XAI) methods could also improve the interpretability of model decisions, fostering greater trust in clinical applications. As a future work, we will incorporate these advanced methods into the current framework, along with additional techniques such as ensemble learning and domain adaptation, to improve accuracy and generalizability. Overall, this study reinforces the capability of deep learning in multi-class classification of the histopathological image and lays a strong foundation for continued research in this domain.

7. Conclusions

In this study, we presented a deep learning-based framework for the multi-class classification of breast cancer subtypes from histopathological images using ResNet architectures. Among the evaluated models, ResNet-50 achieved the highest classification performance across all major metrics, including accuracy, AUC, ROC, precision, recall, F1-score, and specificity. This superior performance is attributed to its deeper architecture and the ability to capture fine-grained features necessary for distinguishing between visually similar subtypes.

Despite the strong performance of the proposed model, some subtypes, such as lobular carcinoma and mucinous carcinoma, remained more challenging to classify, likely due to subtle morphological differences and limited sample sizes in the dataset. Nevertheless, our approach demonstrates a strong baseline for breast cancer subtype classification with relatively simpler architectures compared to more complex models such as transformers, recurrent neural networks, and hybrid systems, which may require greater computational resources.

This study provides valuable insights into the potential of deep learning models for automated histopathological image analysis. Future research will focus on integrating advanced architectures, ensemble learning, domain adaptation, and explainable AI (XAI) techniques to further enhance classification accuracy, model robustness, and interpretability. Ultimately, this line of work aims to contribute to the development of reliable and clinically applicable AI-assisted diagnostic tools for breast cancer.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.D. and R.M.; methodology, A.D.; software, A.D.; validation, A.D. and R.M.; formal analysis, A.D.; investigation, A.D.; resources, A.D.; data curation, A.D.; writing—original draft preparation, R.M.; writing—review and editing, R.M.; visualization, R.M.; supervision, R.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank California State University, Fullerton (CSUF), for providing access to Grammarly through its institutional license. During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used Grammarly for grammar checking and sentence refinement. The authors have reviewed and edited the final manuscript and take full responsibility for its content.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Løyland, B.; Sandbekken, I.H.; Grov, E.K.; Utne, I. Causes and risk factors of breast cancer, what do we know for sure? An evidence synthesis of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Cancers 2024, 16, 1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veta, M.; Pluim, J.P.; Diest, P.J.V.; Viergever, M.A. Breast cancer histopathology image analysis: A review. IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering 2014, 61, 1400–1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aswathy, M.A.; Jagannath, M. Detection of breast cancer on digital histopathology images: Present status and future possibilities. Informatics in Medicine Unlocked 2017, 8, 74–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.I.; Uribe, D.J.; Daling, J.R. Clinical characteristics of different histologic types of breast cancer. British Journal of Cancer 2005, 93, 1046–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rakha, E.A.; et al. Breast cancer prognostic classification in the molecular era: the role of histological grade. Breast Cancer Research 2010, 12, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gøtzsche, P.C.; Olsen, O. Is screening for breast cancer with mammography justifiable? The Lancet 2000, 355, 129–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olsen, O.; Gøtzsche, P.C. Screening for breast cancer with mammography. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2001, p. CD001877.

- Gøtzsche, P.C.; Jørgensen, K.J. Screening for breast cancer with mammography. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2013. Accessed: Mar. 01, 2025. [Online].

- Guo, R.; Lu, G.; Qin, B.; Fei, B. Ultrasound imaging technologies for breast cancer detection and management: a review. Ultrasound in Medicine & Biology 2018, 44, 37–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gordon, P.B. Ultrasound for breast cancer screening and staging. Radiologic Clinics 2002, 40, 431–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sood, R.; et al. Ultrasound for Breast Cancer Detection Globally: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JGO 2019, pp. 1–17. [CrossRef]

- Bluemke, D.A.; et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of the breast prior to biopsy. JAMA 2004, 292, 2735–2742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwok, T.C.; et al. Histological grading of breast cancer on needle core biopsy: the role of immunohistochemical assessment of proliferation. Histopathology 2010, 57, 212–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellis, I.O.; Humphreys, S.; Michell, M.; Pinder, S.E.; Wells, C.A.; Zakhour, H. Best Practice No 179: Guidelines for breast needle core biopsy handling and reporting in breast screening assessment. Journal of Clinical Pathology 2004, 57, 897–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chougrad, H.; Zouaki, H.; Alheyane, O. Deep Convolutional Neural Networks for breast cancer screening. Computer Methods and Programs in Biomedicine 2018, 157, 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, B.; Ge, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Guan, E.; Yan, W. Benign and malignant mammographic image classification based on Convolutional Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2018 10th International Conference on Machine Learning and Computing, New York, NY, USA, 2018; ICMLC ’18, p. 247–251. [CrossRef]

- Saber, A.; Sakr, M.; Abo-Seida, O.M.; Keshk, A.; Chen, H. A novel deep-learning model for automatic detection and classification of breast cancer using the transfer-learning technique. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 71194–71209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saini, M.; Susan, S. Vggin-net: Deep transfer network for imbalanced breast cancer dataset. IEEE/ACM Transactions on Computational Biology and Bioinformatics 2022, 20, 752–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahidi, F.; Daud, S.M.; Abas, H.; Ahmad, N.A.; Maarop, N. Breast cancer classification using deep learning approaches and histopathology image: a comparison study. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 187531–187552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spanhol, F.A.; Oliveira, L.S.; Petitjean, C.; Heutte, L. A Dataset for Breast Cancer Histopathological Image Classification. IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering 2016, 63, 1455–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alqudah, A.; Alqudah, A.M. Sliding Window Based Support Vector Machine System for Classification of Breast Cancer Using Histopathological Microscopic Images. IETE Journal of Research 2022, 68, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariateja, D.; Aprilliyani, R.; Chaidir, M.D. Breast cancer histopathological images classification based on weighted K-nearest neighbor. AIP Conference Proceedings 2024, 3215, 120007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murtaza, G.; Abdul Wahab, A.W.; Raza, G.; Shuib, L. A tree-based multiclassification of breast tumor histopathology images through deep learning. Computerized Medical Imaging and Graphics 2021, 89, 101870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Araújo, T. Others. Classification of breast cancer histopathological images using Convolutional Neural Networks. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0177544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bayramoglu, N.; Kannala, J.; Heikkilä, J. Deep learning for magnification independent breast cancer histopathology image classification. In Proceedings of the 2016 23rd International Conference on Pattern Recognition (ICPR); 2016; pp. 2440–2445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, S.; Khurana, S. Enhanced Breast Tumor Detection with a CNN-LSTM Hybrid Approach: Advancing Accuracy and Precision. In Proceedings of the 2024 2nd International Conference on Recent Trends in Microelectronics, Automation, Computing and Communications Systems (ICMACC); 2024; pp. 14–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaddes, M.; Ayid, Y.M.; Elshewey, A.M.; Others. Breast cancer classification based on hybrid CNN with LSTM model. Scientific Reports 2025, 15, 4409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toma, T.A.; Biswas, S.; Miah, M.S.; Alibakhshikenari, M.; Virdee, B.S.; Fernando, S.; Rahman, M.H.; Ali, S.M.; Arpanaei, F.; Hossain, M.A.; et al. Breast Cancer Detection Based on Simplified Deep Learning Technique With Histopathological Image Using BreaKHis Database. Radio Science 2023, 58, e2023RS007761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benhammou, Y.; Achchab, B.; Herrera, F.; Tabik, S. BreakHis based breast cancer automatic diagnosis using deep learning: Taxonomy, survey and insights. Neurocomputing 2020, 375, 9–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umer, M.J.; Sharif, M.; Kadry, S.; Alharbi, A. Multi-Class Classification of Breast Cancer Using 6B-Net with Deep Feature Fusion and Selection Method. Journal of Personalized Medicine 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rafiq, A.; Jaffar, A.; Latif, G.; Masood, S.; Abdelhamid, S.E. Enhanced Multi-Class Breast Cancer Classification from Whole-Slide Histopathology Images Using a Proposed Deep Learning Model. Diagnostics 2025, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bardou, D.; Zhang, K.; Ahmad, S.M. Classification of Breast Cancer Based on Histology Images Using Convolutional Neural Networks. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 24680–24693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mi, W.; et al. . Deep Learning-Based Multi-Class Classification of Breast Digital Pathology Images. Cancer Management and Research 2021, 13, 4605–4617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, P.T.; Nguyen, T.T.; Nguyen, N.C.; Le, T.T. Multiclass Breast Cancer Classification Using Convolutional Neural Network. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Symposium on Electrical and Electronics Engineering (ISEE), Oct. 2019; pp. 130–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldakhil, L.A.; Alhasson, H.F.; Alharbi, S.S. Attention-Based Deep Learning Approach for Breast Cancer Histopathological Image Multi-Classification. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tummala, S.; Kim, J.; Kadry, S. BreaST-Net: Multi-Class Classification of Breast Cancer from Histopathological Images Using Ensemble of Swin Transformers. Mathematics 2022, 10, 4109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, A.A.; Abdullahi, M.; Junaidu, S.B.; Ibrahim, H.H.; Chiroma, H. Improved multi-classification of breast cancer histopathological images using handcrafted features and deep neural network (dense layer). Intelligent Systems with Applications 2022, 14, 200066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chikkala, R.B.; et al. Enhancing Breast Cancer Diagnosis With Bidirectional Recurrent Neural Networks: A Novel Approach for Histopathological Image Multi-Classification. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 41682–41707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Mehra, R. Conventional Machine Learning and Deep Learning Approach for Multi-Classification of Breast Cancer Histopathology Images—a Comparative Insight. Journal of Digital Imaging 2020, 33, 632–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Figure 1.

Histopathological images of different breast tumor subtypes from the BreaKHis dataset at various magnifications: (a) Adenosis (40X), (b) Fibroadenoma (100X), (c) Phyllodes Tumor (200X), (d) Tubular Adenoma (400X), (e) Ductal Carcinoma (40X), (f) Lobular Carcinoma (100X), (g) Mucinous Carcinoma (200X), and (h) Papillary Carcinoma (400X).

Figure 1.

Histopathological images of different breast tumor subtypes from the BreaKHis dataset at various magnifications: (a) Adenosis (40X), (b) Fibroadenoma (100X), (c) Phyllodes Tumor (200X), (d) Tubular Adenoma (400X), (e) Ductal Carcinoma (40X), (f) Lobular Carcinoma (100X), (g) Mucinous Carcinoma (200X), and (h) Papillary Carcinoma (400X).

Figure 2.

Illustration of the ResNet-based multi-class breast tumor classification model. The pipeline consists of convolutional feature extraction, residual block learning, global pooling, and final classification via a fully connected layer.

Figure 2.

Illustration of the ResNet-based multi-class breast tumor classification model. The pipeline consists of convolutional feature extraction, residual block learning, global pooling, and final classification via a fully connected layer.

Figure 3.

Training and validation loss (left) and validation accuracy (right) over 20 epochs for ResNet-50 on the BreaKHis dataset.

Figure 3.

Training and validation loss (left) and validation accuracy (right) over 20 epochs for ResNet-50 on the BreaKHis dataset.

Figure 4.

Confusion matrices of ResNet-18, ResNet-34, and ResNet-50 on the test dataset, showing classification performance across eight breast tumor subtypes. Each matrix illustrates correct predictions along the diagonal and misclassifications off-diagonal.

Figure 4.

Confusion matrices of ResNet-18, ResNet-34, and ResNet-50 on the test dataset, showing classification performance across eight breast tumor subtypes. Each matrix illustrates correct predictions along the diagonal and misclassifications off-diagonal.

Figure 5.

ROC and Precision-Recall (PR) curves for ResNet-34, and ResNet-50 models on the test dataset. This plot shows the trade-off between sensitivity and specificity for each model and the classification performance in imbalanced scenarios.

Figure 5.

ROC and Precision-Recall (PR) curves for ResNet-34, and ResNet-50 models on the test dataset. This plot shows the trade-off between sensitivity and specificity for each model and the classification performance in imbalanced scenarios.

Figure 6.

Precision, Recall, F1-Score, and Specificity for each of the eight breast cancer classes using the ResNet-50 model.

Figure 6.

Precision, Recall, F1-Score, and Specificity for each of the eight breast cancer classes using the ResNet-50 model.

Figure 7.

Visual assessment of ResNet-50 model predictions on randomly selected histopathological images from the BreaKHis test set. Each image displays the corresponding ground truth class (True) and the predicted class (Pred) assigned by the model. The visualization highlights the model’s strong ability to correctly classify most tumor subtypes across varying magnifications, while also revealing occasional misclassifications in subtypes with subtle morphological differences.

Figure 7.

Visual assessment of ResNet-50 model predictions on randomly selected histopathological images from the BreaKHis test set. Each image displays the corresponding ground truth class (True) and the predicted class (Pred) assigned by the model. The visualization highlights the model’s strong ability to correctly classify most tumor subtypes across varying magnifications, while also revealing occasional misclassifications in subtypes with subtle morphological differences.

Table 1.

Four magnification levels in BreaKHis, categorized into benign and malignant tumor subtypes.

Table 1.

Four magnification levels in BreaKHis, categorized into benign and malignant tumor subtypes.

| Magnification Level |

Description |

Application |

| 40X |

Low-resolution overview of tissue structure |

Identifying overall morphology |

| 100X |

Balanced detail of cell structure and tissue morphology |

Intermediate analysis |

| 200X |

Detailed examination of cellular organization |

Feature extraction for AI models |

| 400X |

High-resolution visualization of individual cell structures |

Fine-grained classification |

Table 2.

Tumor subtypes in the BreaKHis dataset. The dataset includes both benign and malignant tumors, each further categorized into four distinct subtypes.

Table 2.

Tumor subtypes in the BreaKHis dataset. The dataset includes both benign and malignant tumors, each further categorized into four distinct subtypes.

| Benign Tumors |

Malignant Tumors |

|

Adenosis: Non-cancerous overgrowth of glands within the lobules |

Ductal Carcinoma: The most common malignant tumor, originating in the milk ducts |

|

Fibroadenoma: Common benign tumor composed of fibrous and glandular tissues |

Lobular Carcinoma: Cancer that begins in the lobules and tends to spread diffusely |

|

Phyllodes Tumor: Rare fibroepithelial tumor with potential to recur |

Mucinous Carcinoma: Malignant tumor characterized by mucin production |

|

Tubular Adenoma: Well-circumscribed benign tumor of tightly packed tubules |

Papillary Carcinoma: Malignant tumor with papillary structural patterns |

Table 3.

Comparison of ResNet architectures utilized in this study.

Table 3.

Comparison of ResNet architectures utilized in this study.

| ResNet Model |

Depth |

Residual Block Type |

Parameters (millions) |

| ResNet-18 |

18 layers |

Basic Block |

11.7 |

| ResNet-34 |

34 layers |

Basic Block |

21.8 |

| ResNet-50 |

50 layers |

Bottleneck Block |

25.6 |

Table 4.

Comparison of classification performance with existing methods.

Table 4.

Comparison of classification performance with existing methods.

| Work |

Method |

Dataset Split (Train:Test) |

Classification Type |

Accuracy |

| [32] |

CNN |

70:30 |

8 Class |

88.23% |

| [33] |

Inception V3 CNN |

80:20 |

8 Class |

88.16% |

| [34] |

CNN |

90:10 |

8 Class |

73.68% |

| [35] |

ECSAnet |

70:30 |

8 Class |

91.3% |

| Proposed |

ResNet-18 |

80:20 |

8 Class |

91.41% |

| Proposed |

ResNet-34 |

80:20 |

8 Class |

90.40% |

| Proposed |

ResNet-50 |

80:20 |

8 Class |

92.30% |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).