Submitted:

14 July 2025

Posted:

15 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Case of Study

2.2. Alternatives for the Emergency and Escape Lighting Test System

- -

- Alternative 1. Traditional Testing of Self-Contained Emergency and Escape Luminaires. This method involves scheduled manual testing of luminaires equipped with integral batteries. It offers flexibility in terms of installation and is simple to implement; however, it requires continuous human intervention for battery status checks and functional verification, increasing operational workload and the potential for human error.

- -

- Alternative 2. Automatic Testing (ATS) of Self-Contained Emergency and Escape Luminaires. This approach integrates automated testing and monitoring protocols directly into self-contained luminaires. By eliminating the need for manual testing, it significantly reduces maintenance demands and improves overall system reliability. Continuous monitoring ensures timely fault detection and enhances compliance with safety regulations.

- -

- Alternative 3. Traditional Testing of Centrally Powered Emergency and Escape Lighting Systems. Under this configuration, a centralized battery system supplies power to multiple luminaires. Manual testing is carried out periodically in accordance with established schedules. Centralized power simplifies battery replacement and lifecycle monitoring, thereby assisting and facilitating maintenance through its centralized structure.

- -

- Alternative 4. Automatic Testing (ATS) of Centrally Powered Emergency and Escape Lighting Systems. This solution incorporates automated testing and diagnostics within a centralized power framework. It enables real-time monitoring and streamlined fault identification, offering enhanced system performance. However, it entails greater infrastructure complexity and a higher initial investment compared to other solutions, as well as the need for skilled professionals to maintain the system.

- -

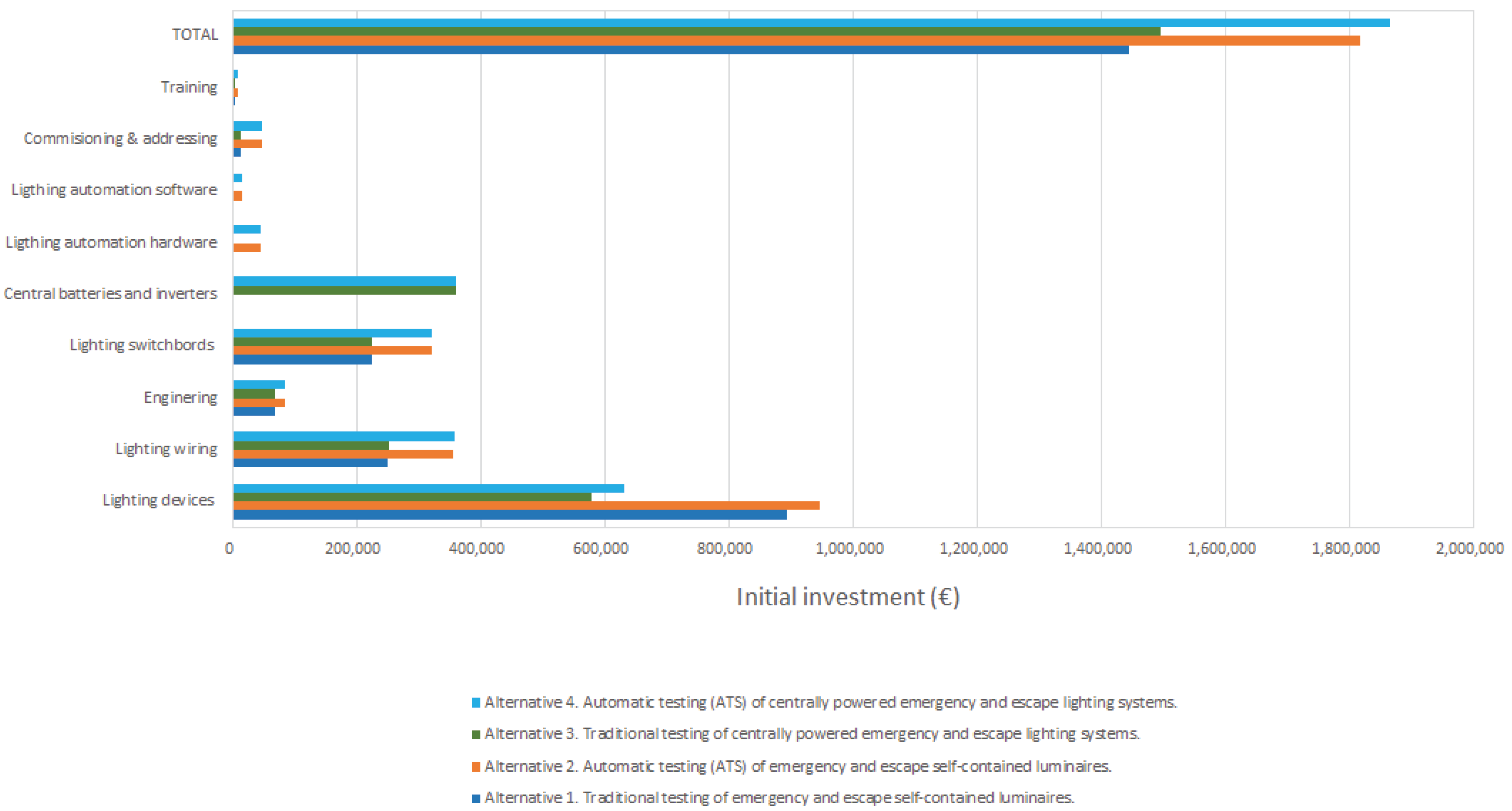

- Luminaire pricing: An average unit price was considered for both emergency luminaires (such as floodlights, technical luminaires, downlights, wall-mounted fixtures, and similar) and escape route luminaires, based on platform design standards.

- -

- Battery pricing: The battery cost was estimated using an average value provided by the manufacturer LIGHTPARTNER for this type of equipment which is the main supplier of luminaires of this platform.

- -

- A 2.5 mm2 cable section was considered for each luminaire, as is standard in this type of installation. A 3G2.5 cable was used for traditional systems in platforms, while a 5G2.5 cable was used for ATS systems, assuming an average distance of 25 meters between luminaires. For centralized systems, it was further assumed that power supply from the battery panels is provided using 35 mm2 cables over a distance of 60 meters. All other auxiliary system cabling (power supplies, heating circuits and automation signals) was estimated as 10% of the total value of the main cabling.

- -

- It was estimated that the entire project of the emergency and escape lighting system should be completed within 4 months with a team of three engineers, whereas autonomous systems are expected to require 5 months.

- -

- The cost of the electrical panels was estimated based on information provided by the supplier for the BorWin 5 project, considering a 30% reduction if the system does not include an automatic control system.

- -

- The cost of the central panels include the inverters, batteries, interconnections and distribution boxes.

- -

- Ilumination software: The involvement of an expert technician in programming was considered for a duration of tree months. This estimation is based on the knowledge acquired during the development of the BorWin5 project.

2.3. Decision Model

- -

- cost

- -

- system architecture and design optimization

- -

- operational performance

3. Results and Discussion

. Similarly, weights were also been assigned to the sub-criteria. The sum of

weights of the sub-criteria must also add up to 100 for each criterion,

. Similarly, weights were also been assigned to the sub-criteria. The sum of

weights of the sub-criteria must also add up to 100 for each criterion,  .

.4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Emergency and Escape Lighting System of BorWin5

| Distribution panels | Central emergency lighting switchboard |

| Sub-distribution emergency lighting switchboard | |

| Central escape lighting switchboard | |

| Sub-distribution escape lighting switchboard | |

| 220Vdc/3x400V+N inverters | Emergency inverter |

| Escape inverter | |

| Approximately 1,800 luminaires equipped with DALI drivers for the emergency and escape networks | |

References

- W. Li, Y. W. Li, Y. Wang, Z. Ye, Y. A. Liu, and L. Wang, “Development of a mixed reality assisted escape system for underground mine- based on the mine water-inrush accident background,” Tunn. Undergr. Sp. Technol., vol. 143, p. 105471, Jan. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Q. Zhang, J. Q. Zhang, J. Zhou, J. Liu, and Y. Zhang, “Design of a ship light environment control system,” in 3rd International Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Automation, and High-Performance Computing (AIAHPC 2023), Jul. 2023, p. 42. [CrossRef]

- L. C. Towle, “An analysis of the overall integrity of an escape route lighting system,” in Fifth International Conference on `Electrical Safety in Hazardous Environments’, 1994, vol. 1994, pp. 239–244. [CrossRef]

- S. Mukherjee, P. S. Mukherjee, P. Satvaya, and S. Mazumdar, “Development of a Microcontroller Based Emergency Lighting System with Smoke Detection and Mobile Communication Facilities,” Light Eng., pp. 46–50, Feb. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- G. Wati et al., “Analysis of Generator Power Requirements for Lighting Distribution Using LED Lights on a 500 DWT Sabuk Nusantara,” Indones. J. Marit. Technol., vol. 1, no. 2, Dec. 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. Suardi, A. Y. S. Suardi, A. Y. Kyaw, A. I. Wulandari, and F. Zahrotama, “Impacts of Application Light-Emitting Diode (LED) Lamps in Reducing Generator Power on Ro-Ro Passenger Ship 300 GT KMP Bambit,” Int. J. Mech. Eng. Sci., vol. 7, no. 1, p. 44, Mar. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- N. Balfe, S. N. Balfe, S. Sharples, and J. R. Wilson, “Understanding Is Key: An Analysis of Factors Pertaining to Trust in a Real-World Automation System,” Hum. Factors J. Hum. Factors Ergon. Soc., vol. 60, no. 4, pp. 477–495, Jun. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. Narasimha and S. R. Salkuti, “Design and development of smart emergency light,” TELKOMNIKA (Telecommunication Comput. Electron. Control., vol. 18, no. 1, p. 358, Feb. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Lowden and, G. Kecklund, “Considerations on how to light the night-shift,” Light. Res. Technol., vol. 53, no. 5, pp. 437–452, Aug. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gritsuk, P. Nosov, O. Dyagileva, and M. Masonkova, “Improving safety of navigation by constructing a dynamic model of the navigator’s actions in the conditions of navigation risks,” Collect. Sci. Work. State Univ. Infrastruct. Technol. Ser. “Transport Syst. Technol., no. 41, pp. 84–95, Jun. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- E. Aizlewood and G. M. B. Webber, “Escape route lighting: Comparison of human performance with traditional lighting and wayfinding systems,” Light. Res. Technol., vol. 27, no. 3, pp. 133–143, Sep. 1995. [CrossRef]

- M. Fuchtenhans, E. H. M. Fuchtenhans, E. H. Grosse, and C. H. Glock, “Literature review on smart lighting systems and their application in industrial settings,” in 2019 6th International Conference on Control, Decision and Information Technologies (CoDIT), Apr. 2019, pp. 1811–1816. [CrossRef]

- H.-C. Lin, L.-Y. H.-C. Lin, L.-Y. Liu, W.-L. Luo, and M.-N. Chi, “Development of Wireless Automatic Checking Handset for Wide-Distributed Emergency Lights,” Meas. Control, vol. 46, no. 7, pp. 213–220, Sep. 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- H. C. Lin, M. N. H. C. Lin, M. N. Chi, and W. L. Luo, “Achievement of a wireless portable apparatus for self-checking emergency lights,” IEEJ Trans. Electr. Electron. Eng., vol. 11, no. 6, pp. 812–819, Nov. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ”IEC 62034:2012; Automatic Test Systems for Battery Powered Emergency Escape Lighting; International Electrotechnical Commission: Geneva, Switzerland, 2012.

- L. García Rodríguez, L. L. García Rodríguez, L. Castro-Santos, and M. I. Lamas Galdo, “Techno-Economic Analysis of the Implementation of the IEC 62034:2012 Standard—Automatic Test Systems for Battery-Powered Emergency Escape Lighting—In a 52.8-Meter Multipurpose Vessel,” Eng, vol. 6, no. 6, p. 110. May; 25. [CrossRef]

- J. Lin, S.-W. J. Lin, S.-W. Huang, H.-Y. Chang, J.-B. Sheu, and G.-H. T. Tzeng, “FACTORS INFLUENCING FOLLOW-ON PUBLIC OFFERING OF SHIPPING COMPANIES FROM INVESTOR PERSPECTIVE – A HYBRID MULTIPLE-CRITERIA DECISION-MAKING APPROACH,” Technol. Econ. Dev. Econ., vol. 30, no. 4, pp. 1087–1119, Jun. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J. Lin, H.-Y. J. Lin, H.-Y. Chang, and B. Hung, “Identifying Key Financial, Environmental, Social, Governance (ESG), Bond, and COVID-19 Factors Affecting Global Shipping Companies—A Hybrid Multiple-Criteria Decision-Making Method,” Sustainability, vol. 14, no. 9, p. 5148, Apr. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. K. Sahoo and S. S. Goswami, “A Comprehensive Review of Multiple Criteria Decision-Making (MCDM) Methods: Advancements, Applications, and Future Directions,” Decis. Mak. Adv., vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 25–48, Dec. 2023. [CrossRef]

- G. Rodríguez, M. I. G. Rodríguez, M. I. Lamas, J. de D. Rodríguez, and C. Caccia, “ANALYSIS OF THE PRE-INJECTION CONFIGURATION IN A MARINE ENGINE THROUGH SEVERAL MCDM TECHNIQUES,” Brodogradnja, vol. 72, no. 4, pp. 1–17, Dec. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinogradova, V. Podvezko, and E. Zavadskas, “The Recalculation of the Weights of Criteria in MCDM Methods Using the Bayes Approach,” Symmetry (Basel)., vol. 10, no. 6, p. 205, Jun. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. I. Lamas, L. M. I. Lamas, L. Castro-Santos, and C. G. Rodriguez, “Optimization of a Multiple Injection System in a Marine Diesel Engine through a Multiple-Criteria Decision-Making Approach,” J. Mar. Sci. Eng., vol. 8, no. 11, p. 946, Nov. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ”DNV. Rules for Classification. Ships. DNV GL: Høvik, Norway, 2021.

| Advantages | Comparison to the other alternatives |

|---|---|

| Lower initial investment compared to ATS | Unlike ATS (alternatives 2 and 4), traditional testing requires no automated control components, diagnostic systems, or communication modules, significantly reducing capital expenditure. |

| Low technical complexity | Unlike centralized systems (alternatives 3 and 4), and automated self-contained luminaires (alternative 2), this approach does not require complex configurations, making it easier to install. |

| Independence and fault containment | Similar to alternative 2 and unlike alternatives 3 and 4, self-contained luminaires function independently. In the event of a failure, the issue is isolated to a single unit, with no impact on other luminaires or circuits. |

| No dependency on central infrastructure | Unlike alternatives 3 and 4, traditional self-contained luminaires do not rely on centralized battery systems, power distribution panels, or extended cabling, making them highly suitable for modular or remote installations. |

| Ideal for small-scale installations | In installations where the number of luminaires is limited, the simplicity and low cost of manual testing offer a practical and efficient solution compared to more sophisticated (and costly) automated or centralized alternatives. |

| Advantages | Comparison to the other alternatives |

|---|---|

| Automated compliance and reduced human error | Unlike alternatives 1 and 3, the ATS function ensures periodic tests (function and duration) are performed automatically according to pre-defined schedules, minimizing the risk of missed inspections, human oversight, or non-compliance with regulatory requirements. |

| Enhanced fault detection and reporting | Unlike traditional systems (alternatives 1 and 3), ATS systems automatically detect, log, and report failures of each addressing luminaries in real time, providing clear and timely diagnostics that support preventive maintenance and reduce downtime. |

| Retention of luminaire independence | Unlike centrally powered systems (alternatives 3 and 4), self-contained luminaires operate independently. A failure in one luminaire does not compromise the functionality of the overall system, enhancing operational reliability in safety-critical environments. |

| Simplified infrastructure compared to centralized systems | Unlike alternatives 3 and 4, this solution does not require central battery systems, power distribution battery networks, or additional cabling, reducing installation complexity and cost, particularly in retrofitting or offshore modular applications. |

| Lower long-term operational costs | Although the initial investment may be higher than traditional test, the reduction in manual labor and increased efficiency in maintenance activities typically result in lower lifecycle costs compared to traditional testing methods. |

| Improved data logging and maintenance planning | Compared to manual systems, ATS provides a continuous log of system performance, supporting maintenance planning, trend analysis, and facilitating documentation for compliance with standards. |

| Suitable for distributed and isolated installations | Unlike centralized systems (alternatives 3 and 4), ATS-enabled self-contained luminaires are well suited for installations with spatial constraints or segmented layouts—common in offshore units—where centralized cabling and control may be impractical. |

| Advantages | Comparison to the other alternatives |

|---|---|

| Lower initial investment compared to ATS | While offering the benefits of centralized power management, this alternative avoids the additional cost of automation infrastructure required in alternatives 2 and 4 (ATS), making it a more economical solution for projects with budget constraints. |

| Simplified system architecture compared to self-contained solutions | Unlike alternatives 1 and 2, the central battery system eliminates the need for each luminaire to be equipped with its own power source. This centralization can simplify power maintenance and lifecycle battery replacement logistics. |

| Unified battery maintenance | With a centralized power source, battery testing, charging, and replacement are managed at a single location—unlike self-contained systems (alternatives 1 and 2), where batteries must be individually maintained and monitored. |

| Suitable for high-density lighting installations | In facilities or offshore units with large concentrations of emergency and escape luminaires, a centralized system may offer a more efficient and structured approach to power management than distributed self-contained units. |

| Lower complexity than ATS systems in terms of software and configuration | Compared to alternatives 2 and 4, traditional centralized systems do not require automated testing protocols or software-based monitoring, reducing system setup complexity and potential cybersecurity risks. |

| Advantages | Comparison to the other alternatives |

|---|---|

| Centralized monitoring and management | Unlike self-contained systems (alternatives 1 and 2), centrally powered ATS systems allow for centralized supervision, enabling real-time fault detection, test result logging, and streamlined maintenance management from a single control point. |

| Automated testing without manual intervention | Unlike traditional testing methods (alternatives 1 and 3), ATS systems perform scheduled functional and autonomy tests automatically, ensuring continuous compliance with safety regulations without relying on manual inspections. |

| Reduced long-term operational costs | Automation and centralized battery infrastructure reduce the need for individual inspections and interventions, leading to significant cost savings over the lifecycle of the system. |

| Optimized energy and battery management | Compared to self-contained luminaires (alternatives 1 and 2), centrally powered systems offer more efficient energy distribution and centralized control of battery charging, discharging, and health monitoring. |

| Scalability and suitability for complex installations | Ideal for large-scale or high-density lighting installations, where managing numerous individual units would be impractical. Centralized systems provide structured and scalable solutions. |

| Integration with Building Management Systems (BMS) or offshore automation system | Unlike traditional systems, ATS centrally powered solutions can be integrated with BMS or other facility management platforms, enabling remote diagnostics, alarm notifications, and full traceability of system performance. Artificial intelligence protocols may be integrated into the automation system by leveraging the continuous monitoring of the luminaires, thereby enabling adaptive and data-driven decision-making. |

| Architectural and technical design flexibility | In emergency and escape lighting, many emergency luminaires—such as projectors, downlights, and recessed fittings with elevated power consumption— are not designed to house an internal battery but also serve architectural or decorative purposes. In such cases, self-contained luminaires (alternatives 1 and 2) would require built-in batteries, which often complicate the luminaire design, increase its size significantly, and negatively impact its aesthetics or architectural integration. A centrally powered system overcomes this limitation by allowing for compact, visually refined luminaires without internal batteries, thus preserving both performance and design intent. |

| Criterion | Sub-criterion | Beneficial |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Cost | 1.1 Initial capital expenditure | ✕ |

| 1.2 Time of preventive maintenance testing | ✕ | |

| 1.3 Long-term operational costs | ✕ | |

| 1.4 Luminaire service life | ✓ | |

| 1.5 Frequency of battery replacement | ✕ | |

| 1.6 Requirement of personnel with high technical expertise | ✕ | |

| 2. System architecture and device optimization | 2.1 Wire cables | ✕ |

| 2.2 No dependency on central infrastructure | ✕ | |

| 2.3 Luminaire weight optimization | ✕ | |

| 2.4 Suitability for high-density luminaire configurations | ✓ | |

| 2.5 Reduction of electrical number switchboards | ✕ | |

| 2.6 Streamlined luminaire design | ✓ | |

| 3. Operational performance |

3.1 Interface with other systems (BMS, ICMS,….) | ✓ |

| 3.2 Influence of human error | ✕ | |

| 3.3 Fault isolation and discrimination | ✓ | |

| 3.4 Optimized data dogging and maintenance management | ✓ | |

| 3.5 Reliability of monthly functional test performance | ✓ | |

| 3.6 Reliability of yearly duration test performance | ✓ | |

| 3.7 Time of fault detection | ✓ |

| Sub-criterion(i.j) | Unit | Alternative 1(k = 1) | Alternative 2(k = 2) | Alternative 3(k = 3) | Alternative 4(k = 4) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.1 | € | 1445.240 | 1818.310 | 1495.663 | 1865.945 |

| 1.2 | hour | 2250 | 250 | 1350 | 250 |

| 1.3 | ratio 3:1 (traditional test/ATS) |

3 | 2 | 3 | 1 |

| 1.4 | hour | 61320 | 61320 | 175200 | 219000 |

| 1.5 | number of battery replacements every 5 years/7 | 1800 | 1800 | 200 | 200 |

| 1.6 | €/month | 1666 | 2540 | 1666 | 2540 |

| 2.1 | kg | 7920 | 11880 | 8202.48 | 12162.48 |

| 2.2 | - | 5 | 3 | 3 | 1 |

| 2.3 | kg | 7182 | 7182 | 5760 | 5760 |

| 2.4 | - | 1 | 4 | 2 | 5 |

| 2.5 | switchboards | 4 | 4 | 8 | 8 |

| 2.6 | - | 1 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 3.1 | - | 1 | 5 | 3 | 5 |

| 3.2 | - | 1 | 5 | 2 | 5 |

| 3.3 | - | 1 | 4 | 3 | 5 |

| 3.4 | - | 1 | 5 | 2 | 5 |

| 3.5 | - | 1 | 5 | 2 | 5 |

| 3.6 | - | 1 | 5 | 2 | 5 |

| 3.7 | - | 1 | 5 | 2 | 5 |

| Sub-criterion(i.j) | Alternative 1(k = 1) | Alternative 2(k = 2) | Alternative 3(k = 3) | Alternative 4(k = 4) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.1 | 1 | 0.113 | 0.88 | 0 |

| 1.2 | 0 | 1 | 0.45 | 1 |

| 1.3 | 0 | 0.5 | 0 | 1 |

| 1.4 | 0 | 1 | 0.722 | 1 |

| 1.5 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 1.6 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 2.1 | 1 | 0.067 | 0.933 | 0 |

| 2.2 | 1 | 0.788 | 0.091 | 0 |

| 2.3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 2.4 | 0 | 0.75 | 0.25 | 1 |

| 2.5 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 2.6 | 0 | 0.5 | 0.75 | 1 |

| 3.1 | 0 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 |

| 3.2 | 1 | 0 | 0.75 | 0 |

| 3.3 | 0 | 0.75 | 0.5 | 1 |

| 3.4 | 0 | 1 | 0.25 | 1 |

| 3.5 | 0 | 1 | 0.25 | 1 |

| 3.6 | 0 | 1 | 0.25 | 1 |

| 3.7 | 0 | 1 | 0.25 | 1 |

| Criterion | Criterion weight | Sub-criterion | Sub-criterion weight |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Cost | α1 = 45% | 1.1 Initial capital expenditure | β1.1 = 25% |

| 1.2 Time of preventive maintenance testing | β1.2 = 20% | ||

| 1.3 Long-term operational costs | β1.3 = 20% | ||

| 1.4 Luminaire service life | β1.4 = 15% | ||

| 1.5 Frequency of battery replacement | β1.5 = 10% | ||

| 1.6 Requirement of personnel with high technical expertise | β1.6 = 10% | ||

| 2. System architecture and device optimization | α2 = 20% | 2.1 Wire cables | β2.1 = 10% |

| 2.2 Independency on central infrastructure | β2.2 = 20% | ||

| 2.3 Luminaire weight optimization | β2.3 = 10% | ||

| 2.4 Suitability for high-density luminaire configurations | β2.4 = 30% | ||

| 2.5 Reduction of electrical number switchboards | β2.5 = 15% | ||

| 2.6 Streamlined luminaire design | β2.6 = 15% | ||

| 3. Operational performance | α3 = 35% | 3.1 Interface with other systems (BMS, ICMS,….) | β3.1 = 15% |

| 3.2 Influence of human error | β3.2 = 15% | ||

| 3.3 Fault isolation and discrimination | β3.3 = 10% | ||

| 3.4 Optimized data dogging and maintenance management | β3.4 = 15% | ||

| 3.5 Reliability of monthly functional test performance | β3.5 = 15% | ||

| 3.6 Reliability of yearly duration test performance | β3.6 = 15% | ||

| 3.7 Time of fault detection | β3.7 = 15% |

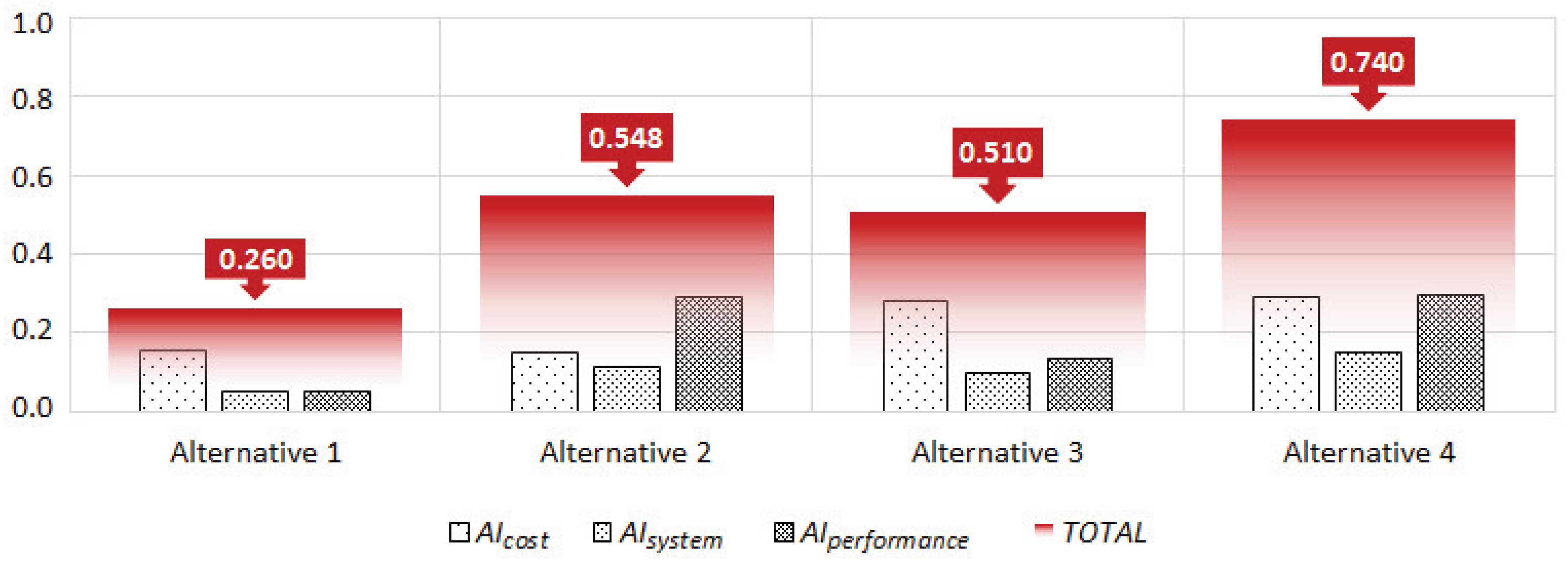

| Alternative (k) | AI |

|---|---|

| Alternative 1 | 0.260 (4th) |

| Alternative 2 | 0.548 (2nd) |

| Alternative 3 | 0.510 (3rd) |

| Alternative 4 | 0.740 (1st) |

| Alternative (k) | Adequacy indices | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AIcost | AIsystem | AIperformance | AI | |

| Alternative 1 | 0.158 (4th) | 0.050 (4th) | 0.053 (4th) | 0.260 (4th) |

| Alternative 2 | 0.148 (3rd) | 0.111 (2nd) | 0.289 (2nd) | 0.548 (2nd) |

| Alternative 3 | 0.278 (2nd) | 0.096 (3rd) | 0.136 (3rd) | 0.510 (3rd) |

| Alternative 4 | 0.293 (1st) | 0.150 (1st) | 0.298 (1st) | 0.740 (1st) |

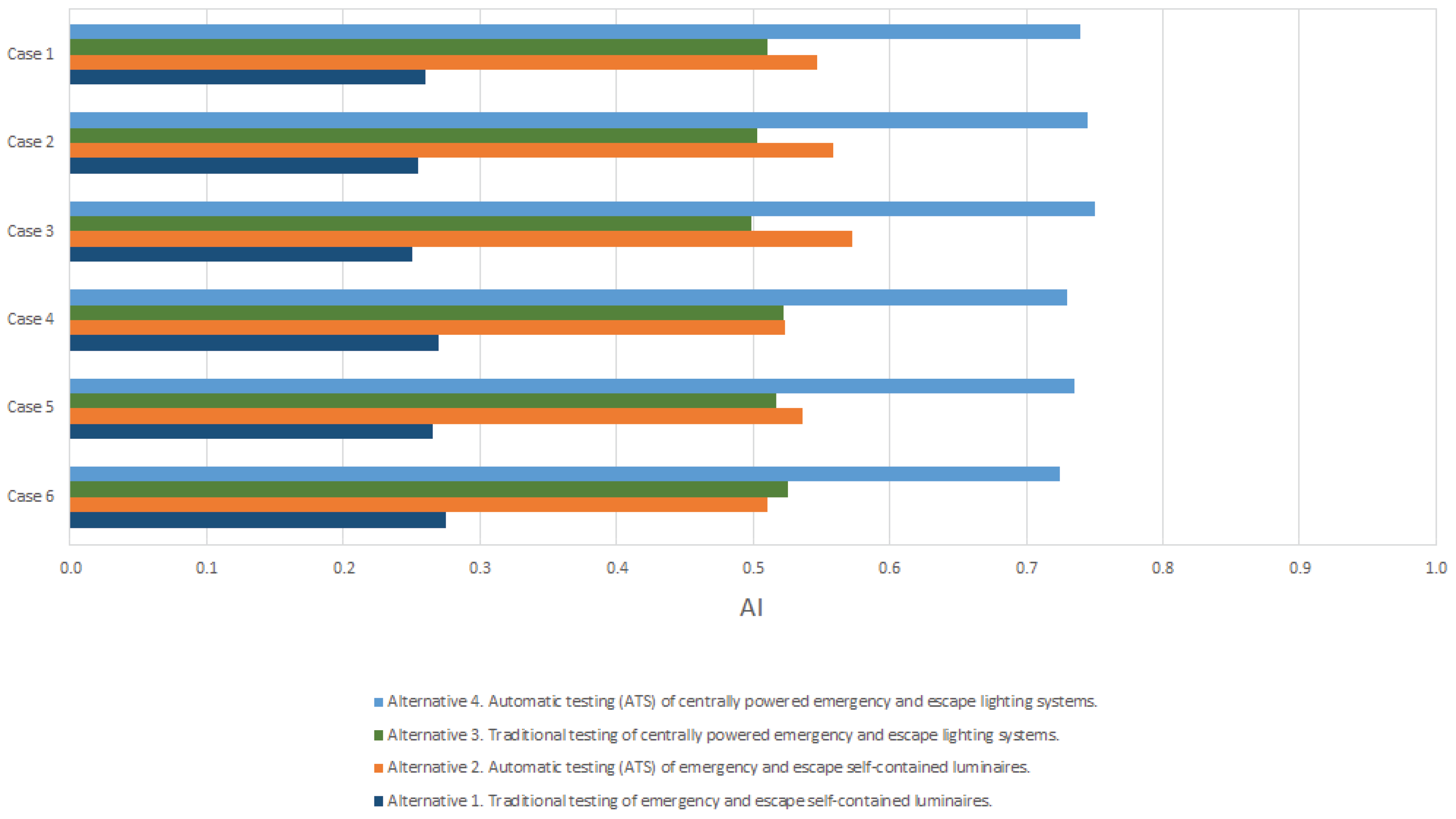

| Weights and adequacy indices | Cases | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 | Case 4 | Case 5 | Case 6 | |

|

α1 |

45% | 40% | 40% | 50% | 50% | 50% |

| α2 | 20% | 25% | 20% | 20% | 15% | 25% |

|

α3 |

35% | 35% | 40% | 30% | 35% | 25% |

| AI1 (alternative 1) |

0.260 (4th) | 0.255 (4th) | 0.250 (4th) | 0.270 (4th) | 0.265 (4th) | 0.275 (4th) |

| AI2 (alternative 2) |

0.547 (2nd) | 0.559 (2nd) | 0.573 (2nd) | 0.523 (2nd) | 0.536 (2nd) | 0.510 (3nd) |

| AI3 (alternative 3) |

0.510 (3rd) | 0.503 (3rd) | 0.499 (3rd) | 0.522 (3rd) | 0.517 (3rd) | 0.526 (2rd) |

| AI4 (alternative 4) |

0.740 (1st) | 0.745 (1st) | 0.750 (1st) | 0.730 (1st) | 0.735 (1st) | 0.725 (1st) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).