1. Introduction

In the English dictionary, the term

pneu·ma (ˈnjuːmə) originates from the Greek word πνεῦμα, which literally means "air" or "breath" and, by extension, "spirit." It carries multiple definitions: in ancient Greek philosophy, it refers to a vital spirit, breath, or animating force—the very principle of life. In Christian theology, particularly in Pauline writings, pneuma denotes the Holy Spirit (Aghion Pneuma) [

1]. Beyond these well-known meanings, the term also appears in a more unexpected context: in medicine, where it historically referred to a supposed vital principle or vapor believed to circulate through the body, intimately linked to respiration and life.

Clearly, the term

pneuma (πνεῦμα) is a remnant of ancient Greek thought, representing a fascinating intersection of philosophy, early science, and medicine. While its semantics might suggest a straightforward equivalent of "air" or "breath," pneuma is a far more intricate concept, hinting at the prescientific mystery of vital and psychic processes—some of which were later elucidated through scientific inquiry, including what we now understand as cardiopulmonary physiology [

2]. It is therefore compelling to trace the historical trajectory of this highly abstract term—often imbued with metaphysical and philosophical connotations—and explore how one of its many facets found a lasting place in the lexicon of medical thought [

3]. In essence, this is an inquiry into how the concept of

pneuma evolved from philosophical speculation into empirical observation.

In ancient Greece, what we now consider scientific knowledge was deeply intertwined with prescientific, philosophical reflections on the cosmos, the elements, and the nature of life itself [

4]. As a result, pneuma was far from an objective, well-defined physiological process; instead, it was conceived as a fundamental cosmological constant—mysterious both in its origins and in its essential nature [5, 6]. This holistic perspective did not draw a strict boundary between physiological function and spiritual essence; rather, they were perceived as inseparable aspects of the same phenomenon [

7]. Yet, tracing the evolution of the term pneuma is particularly illuminating, as it reveals how conceptual thought gradually adopted new modes of understanding reality—modes increasingly defined by specialization and objectification [

8]. Ultimately, this intellectual transformation led to the clear distinctions we now make between the abstract and the spiritual on one hand, and the concrete and the physiological on the other [

9].

This article aims to provide a fresh perspective on how the concept of pneuma, with all its intricate connotations, shaped early cardiopulmonary medicine. Rather than reiterating conventional historical narratives, we will examine the subtle nuances of how pneuma evolved from the philosophical and prescientific traditions of antiquity into its place within modern medical discourse [10, 11]. By doing so, we seek to deepen our understanding of how these shifting interpretations influenced early conceptions of the heart, lungs, and the circulation of vital substances [

2]. Moreover, this article will explore the enduring echoes of pneuma—not only in medical terminology but also in broader conceptualizations of health and disease, where traces of its holistic mystery still seem to persist.

To achieve this, we will move beyond a purely chronological account and instead adopt a thematic approach, examining:

The philosophical foundations of

pneuma, tracing its roots in pre-Socratic thought and its development in the works of Plato and Aristotle [

2].

The application of

pneuma in early medical theories, with a focus on its role in Hippocratic and Alexandrian medicine [

3].

The transformation and eventual decline of pneuma as a dominant theory in light of emerging scientific discoveries, particularly in the works of figures like Galen, Ibn-Nafis, and William Harvey [9, 12].

The enduring legacy of

pneuma, analyzing its influence on medical language, its subtle presence in contemporary medical concepts, and its broader significance in the history of medicine [

8].

Through this thematic exploration, we aim to gain a more insightful perspective on the multifaceted role of pneuma in the historical development of cardiopulmonary medicine.

2. Materials and Methods

This study employs a historical and thematic analysis of the evolution of the concept of pneuma in cardiopulmonary medicine, tracing its philosophical origins and medical applications across different historical periods. The methodology consists of a comprehensive literature review, source evaluation, and comparative analysis of primary and secondary texts.

2.1. Literature Review and Source Selection

The research is based on an extensive review of historical, medical, and philosophical literature concerning pneuma and its role in ancient, medieval, and early modern medical theories. Primary sources include the works of pre-Socratic philosophers, Plato, Aristotle, Hippocratic and Alexandrian medical texts, Galenic treatises, and medieval and Renaissance medical manuscripts. Secondary sources include modern analyses, historical interpretations, and contemporary discussions on the relevance and transformation of pneuma in medical thought.

A systematic search was conducted using academic databases such as PubMed, Scopus, Google Scholar, and specialized repositories for historical texts in medicine and philosophy. The search terms included "pneuma," "ancient cardiopulmonary physiology," "history of respiration," "Hippocratic medicine," "Galenic physiology," "pulmonary circulation," and "evolution of medical theories." Inclusion criteria prioritized peer-reviewed articles, historical monographs, and critical editions of primary sources.

2.2. Comparative and Thematic Analysis

To structure the analysis, a thematic approach was adopted to examine the conceptual trajectory of pneuma in different medical traditions. The following themes were identified and analyzed:

Philosophical Foundations – Investigation of how early Greek philosophers conceptualized pneuma as a fundamental principle of life, emphasizing its metaphysical and cosmological dimensions.

Medical Theories in Antiquity – Examination of the role of pneuma in Hippocratic medicine, Alexandrian anatomical studies, and the Pneumatist school, focusing on how these traditions integrated pneuma into physiological models.

Galenic Systemization – Analysis of Galen’s tripartite model of pneuma and its influence on medieval and early modern medical theories.

Scientific Challenges and Decline – Assessment of key developments that led to the empirical rejection of pneuma, including Ibn al-Nafis’s discovery of pulmonary circulation, William Harvey’s theory of blood circulation, and the identification of oxygen in the 18th century.

Modern Legacy and Conceptual Reinterpretations – Discussion of how the historical concept of pneuma continues to inform medical thought, including contemporary perspectives on holistic medicine and the mind-body connection.

2.3. Historical Contextualization and Source Evaluation

Each historical period was analyzed within its intellectual and scientific context to avoid retrospective interpretations. Primary texts were examined in their original language when available, with references to established translations and scholarly commentaries. Secondary sources were critically assessed for historical accuracy, interpretative biases, and methodological rigor.

3. The Philosohical Foundation of Pneuma

In light of the preceding discussion, it is evident that the concept of pneuma did not emerge ex nihilo; rather, it is deeply rooted in the philosophical inquiries of the ancient Greeks, who were primarily concerned with exploring the fundamental principles of the cosmos and the nature of life itself [

13]. Therefore, a review of these philosophical foundations is essential for developing a more nuanced understanding of the complexity of this concept.

3.1. Pre-Socratic Influences

Among the many groundbreaking developments in early Greek philosophical thought, the Pre-Socratic philosophers were the first to explore the notion of pneuma in their quest for a deeper understanding of the human condition. Their primary focus was the identification of the arche—the fundamental principle of the universe. Within this framework, air, in its tangible and dynamic form, emerged as one of the earliest elements considered a conduit to the transcendental principles of existence [14, 15].

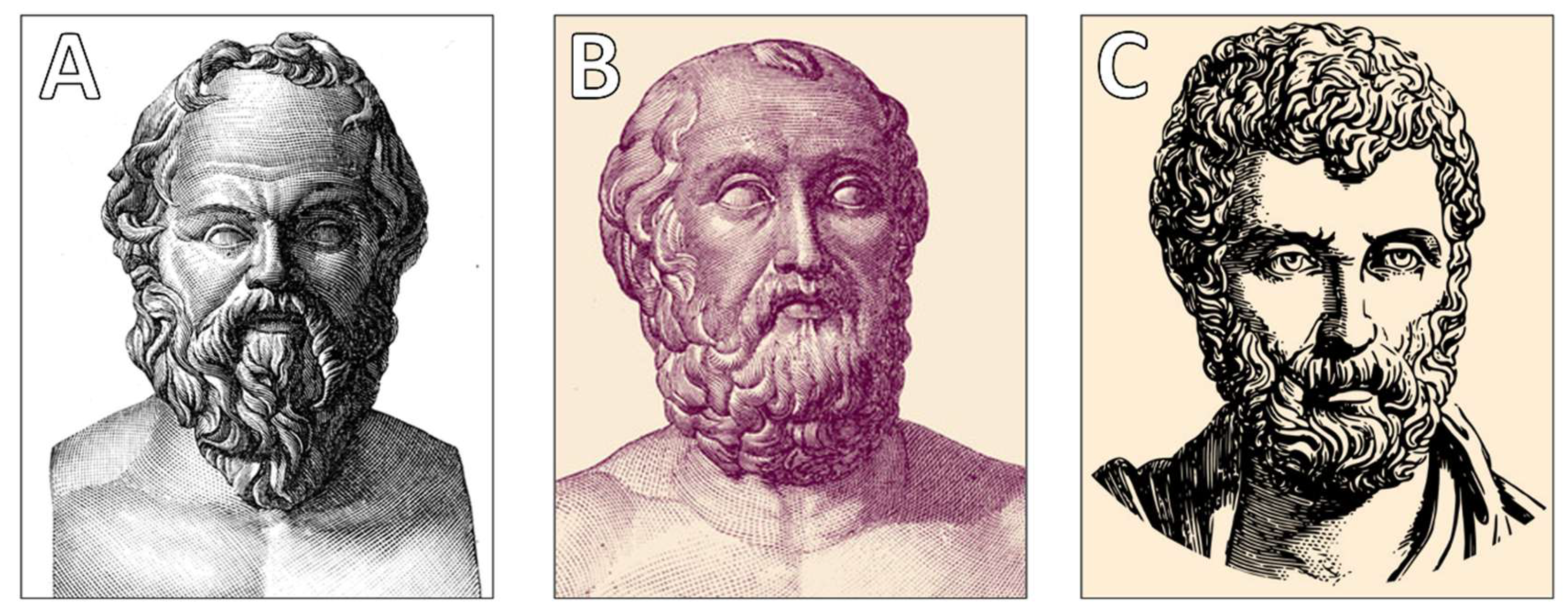

Anaximenes of Miletus (6

thcentury BCE,

Figure 1A) was the foremost proponent of the idea that air served as the

arche(αρχή)of all things—a primordial, protean substance capable of transforming into other elements through the processes of condensation and rarefaction. In this view, air was not merely a physical element but a mysterious, causative force intricately tied to the origins of both life and the soul [

16]. This early association of air with vitality and the psyche laid the groundwork for the more developed concept of

pneuma that would emerge in later philosophical and medical traditions [

17].

Other Pre-Socratic philosophers also contributed to the conceptualization of pneuma as a fundamental substratum of being. Empedocles (5

thcentury BCE,

Figure 1B) is best known for his cosmological theory, which proposed that the universe consists of four elemental constituents—earth, air, fire, and water—governed by two opposing forces, love (

Eros) and strife (

Anteros) [

18]. Although he never explicitly equated air with

pneuma, he nevertheless emphasized its importance as one of the universe’s foundational elements [

19]. Furthermore, his ideas about the cyclical processes of the cosmos may have influenced later interpretations of respiration and other dynamic exchanges between organisms and their environment.

3.2. Plato and Pneuma

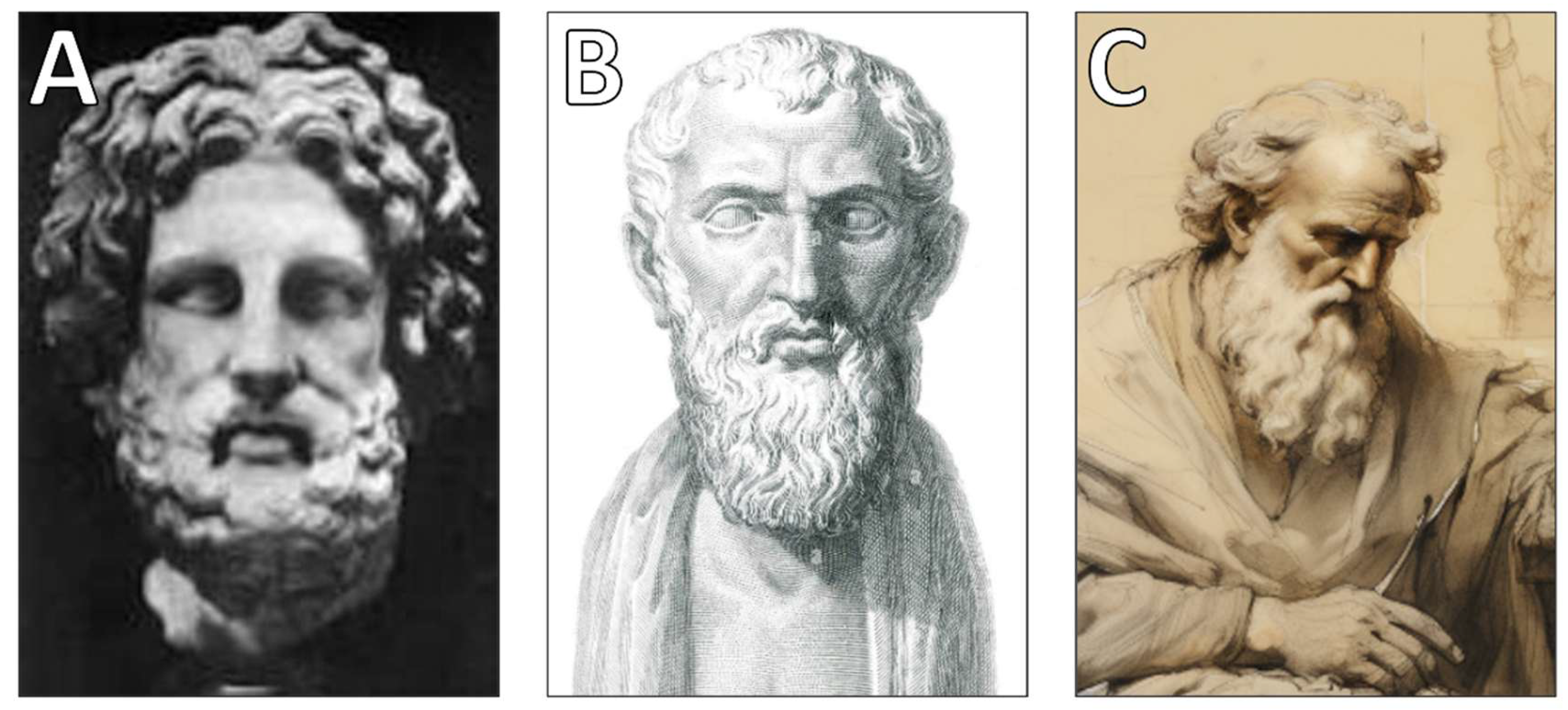

Socrates (470 – 399 BCE,

Figure 2A) himself did not develop a specific theory of

pneuma in the context of pulmonary physiology. Unlike the Pre-Socratics, who were primarily concerned with identifying the fundamental principles of the cosmos, and later philosophers like Aristotle and Galen, who integrated pneuma into physiological models, Socrates focused on ethical philosophy, epistemology, and dialectical reasoning rather than natural science or medical theory.However, in dialogues recorded by Plato (428/423 - 348/347 BCE,

Figure 2B), Socrates occasionally alluded to breath (

pneuma) in a more metaphorical or spiritual sense, often linking it to the soul rather than physiological functions. His discussions were more concerned with

psyche (soul) and its moral and intellectual development rather than material or biological processes[20, 21].

Thus, while Socrates may have acknowledged pneuma in a general philosophical context, he did not contribute directly to its medical or physiological interpretations. Instead, it was later thinkers—such as Aristotle, the Stoics, and Galenic physicians—who expanded the concept into a framework that included its role in respiration and bodily functions [

21].

Naturally, such a significant concept was not absent from the philosophical dialogues of Plato. However, whenever he referred to pneuma, it was primarily in relation to the psyche (soul) and its connection to the body rather than as a physiological entity. In Plato’s grand cosmology, the universe itself was conceived as a living, intelligent being, imbued with a form of consciousness—a property often associated with breath or pneuma [

20]. Within this framework, Plato explored the nature of the soul and distinguished its various aspects, yet he did not develop a comprehensive physiological theory of pneuma. Instead, he acknowledged it as an intermediary between the material body and the higher functions of the soul, suggesting that it played a role in the transmission of life and movement.

While Plato did not explicitly link pneuma to respiration in a medical sense, his occasional references to it as a vehicle for the soul’s interaction with the body contributed to the broader philosophical discourse on the nature of life. His ideas laid the groundwork for later interpretations that connected pneuma not only to metaphysical and psychological processes but also to physiological functions. Thus, his conceptualization of pneuma—though abstract—anticipated future debates on the relationship between breath, vitality, and the mechanisms sustaining human existence [

21].

3.3. Aristotle’s Comprehensive View

Aristotle (4

thcentury BCE,

Figure 2C) provided a more systematic and detailed account of

pneuma, bridging the abstract philosophical conceptions of his predecessors with the more structured biological principles that would emerge in later medical traditions. Unlike earlier thinkers who viewed pneuma primarily as an elemental force or a broad metaphysical principle, Aristotle introduced the concept of connate pneuma—a form of vital heat inherent to living beings, originating in the heart and essential for sustaining life [

22]. In his view, respiration played a crucial role in regulating this internal heat, ensuring physiological balance. This perspective can be seen as an early formulation of a homeostatic mechanism, wherein breathing served not only to maintain life but also to modulate the body's internal equilibrium. Aristotle’s emphasis on the heart’s function as the seat of heat, and the role of respiration in its regulation, would later exert a profound influence on emerging medical theories, particularly those of Galen and later physicians [21, 23, 24].

Within Aristotle’s hierarchical model of the soul, pneuma functioned at different levels, aligning with his tripartite division of the soul into the nutritive soul, the sensitive soul, and the rational soul. Each of these possessed its own pneumatic function, reflecting its role in the body's physiological and intellectual processes [

25]. The higher faculties of the soul, associated with cognition and rational thought, were linked to a more refined and subtle form of pneuma, whereas the lower faculties, responsible for growth and nutrition, relied on a coarser and more material manifestation of it. This distinction reinforced the idea that pneuma was not a singular entity but rather a dynamic force, adapting to different levels of biological and cognitive complexity.

3.4. Praxagoras’sTheory

Orly Lewis's book, "Praxagoras of Cos on Arteries, Pulse and Pneuma," delves into the medical theories of Praxagoras (4

th-3

rdcentury BCE,

Figure 3A), particularly his distinctions between arteries and veins, and his perspectives on pulsation and pneuma (vital air or breath). The work compiles and interprets fragmentary evidence of Praxagoras's ideas, offering fresh insights into his views on the soul, heart functions, and the role of pneuma[26, 27].

Praxagoras is credited with differentiating arteries from veins based on structural differences, noting that arteries have thicker walls and are involved in pulsation. He theorized that arteries carried pneuma rather than blood, a concept that influenced subsequent medical thought. Additionally, he believed that arteries terminated in structures resembling neura (sinews or nerves), contributing to the understanding of bodily movement[

26].

Lewis's analysis challenges previous interpretations of Praxagoras's work, emphasizing the empirical basis of his theories and his engagement with earlier medical debates and Aristotelian physiology. The book includes an edition and translation of relevant fragments, some previously absent from standard collections, followed by commentary and a synthetic analysis of Praxagoras's contributions to the history of medicine and ideas[

27].

3.5. Pneuma and Stoicism

Friedrich Kudlien's 1974 article, "Die Pneuma-Bewegung. Ein Beitragzum Thema 'Medizin und Stoa'," explores the concept of 'pneuma' within the context of ancient medicine and Stoic philosophy. 'Pneuma,' often translated as 'breath' or 'spirit,' played a crucial role in both medical theories and Stoic thought, serving as a fundamental principle of life and vitality [

28]. Kudlien examines how medical practitioners and Stoic philosophers (

Figure 3B) interpreted 'pneuma,' highlighting its significance in physiological processes and its metaphysical implications. The article delves into the intersections between medical practices and Stoic philosophy, shedding light on how the concept of 'pneuma' influenced understandings of human health, disease, and the functioning of the body and soul. By analyzing historical texts and philosophical doctrines, Kudlien contributes to a deeper understanding of the 'pneuma' concept, illustrating its impact on the development of medical and philosophical thought in antiquity.

In the early twentieth century, historians interpreted the alchemical theories of the third-century alchemist Zosimus of Panopolis (

Figure 3C) through the lens of Platonism and Aristotelianism, framing his ideas on transmutation within these philosophical traditions. More recently, scholars such as Christina Viano and William Newman have proposed a link between Zosimean alchemy and Stoicism. This paper builds on their insights by conducting a close textual analysis of Zosimus's writings, offering a Stoic perspective on key aspects of his alchemical thought, particularly the roles of pneuma and tension. Zosimus viewed pneuma as essential for imparting color to metals, while tension contributed to the stability and cohesion of metallic compounds. This interpretation suggests that Zosimus employed Stoic principles to explain the alchemical process of metal tincturing [

29].

4. ApplicationofPneumain Early Medical Theories

As the concept of pneuma evolved through philosophical discourse, it found fertile ground in the realm of medicine, where it was no longer confined to abstract speculation but became integral to understanding the human body, the causes of disease, and the principles of treatment. The intellectual environment of ancient medical traditions absorbed and refined this idea, translating it from a cosmological force into a physiological and pathological framework.From the earliest recorded medical theories—particularly those associated with Hippocratic and Alexandrian medicine—pneuma played a pivotal role in shaping early conceptions of bodily function and disease. Physicians and anatomists sought to explain the mechanisms of respiration, circulation, and neural activity through the movement and regulation of pneuma, incorporating it into their models of health and illness. Over time, this once-metaphysical concept became a key explanatory tool in diagnosing ailments and devising therapeutic interventions, marking a critical shift from philosophical abstraction to empirical medical inquiry[30-33].

4.1. Hippocratic Medicine and Pneuma

A cornerstone of medical history, the Hippocratic Corpus stands as an enduring testament to the foundational principles of ancient medical thought. Comprising a collection of medical treatises attributed to Hippocrates (460 – 370 BCE,

Figure 4A) and his followers, these writings played a crucial role in shaping the practice of medicine for centuries. While they do not present a fully developed theory of pneuma, they reflect a growing awareness of its significance in understanding health and disease, demonstrating its gradual integration into medical discourse [30, 31]. The Hippocratic Corpus offers some of the earliest attempts to move away from supernatural explanations of disease, instead emphasizing natural causes, bodily functions, and environmental influences—elements that would later shape the evolving concept of pneuma as a physiological principle.

Figure 4.

Hippocratic and early Hellenistic contributions to pneuma theory. (A) Hippocrates of Kos (460–370 BCE) – The renowned Greek physician whose medical writings included early references to pneuma as a crucial factor in health and disease, laying the foundation for later physiological theories.(B)OctogintaVolumina (The Hippocratic Corpus) – The first complete Latin edition (1525, Rome) of the Hippocratic Corpus, a collection of medical texts that shaped early medical thought and included discussions on the role of pneuma in bodily functions.(C) Diocles of Carystus (375–295 BCE) – An influential Hellenistic physician who integrated pneuma into anatomical and physiological explanations, contributing to its transition from a philosophical concept to a structured medical theory.

Figure 4.

Hippocratic and early Hellenistic contributions to pneuma theory. (A) Hippocrates of Kos (460–370 BCE) – The renowned Greek physician whose medical writings included early references to pneuma as a crucial factor in health and disease, laying the foundation for later physiological theories.(B)OctogintaVolumina (The Hippocratic Corpus) – The first complete Latin edition (1525, Rome) of the Hippocratic Corpus, a collection of medical texts that shaped early medical thought and included discussions on the role of pneuma in bodily functions.(C) Diocles of Carystus (375–295 BCE) – An influential Hellenistic physician who integrated pneuma into anatomical and physiological explanations, contributing to its transition from a philosophical concept to a structured medical theory.

Figure 5.

Alexandrian anatomists and the refinement of pneuma-based physiology. (A) Erasistratus of Ceos (304 – 250 BCE), who proposed that arteries carried pneuma rather than blood, contributing to early circulatory theories.(B) Herophilos of Chalcedon (335 – 280 BCE), who conducted anatomical dissections and associated pneuma with brain function and sensation.

Figure 5.

Alexandrian anatomists and the refinement of pneuma-based physiology. (A) Erasistratus of Ceos (304 – 250 BCE), who proposed that arteries carried pneuma rather than blood, contributing to early circulatory theories.(B) Herophilos of Chalcedon (335 – 280 BCE), who conducted anatomical dissections and associated pneuma with brain function and sensation.

Figure 6.

The Pneumatic School and Galenic Systematization of pneuma. (A) Athenaeus of Attalia (1st century CE), founder of the Pneumatic School of Medicine, which emphasized pneuma as a key regulator of health.(B) Aelius Galenus (Galen) (129–216 CE), who developed a tripartite classification of pneuma and integrated it into his influential medical theories.

Figure 6.

The Pneumatic School and Galenic Systematization of pneuma. (A) Athenaeus of Attalia (1st century CE), founder of the Pneumatic School of Medicine, which emphasized pneuma as a key regulator of health.(B) Aelius Galenus (Galen) (129–216 CE), who developed a tripartite classification of pneuma and integrated it into his influential medical theories.

In Hippocratic medicine, pneuma was not merely linked to respiration; it was conceived as a fundamental force governing a wide array of internal bodily processes, particularly those we now recognize as homeostatic mechanisms [

32]. While breathing was acknowledged as the most essential function of life, pneuma was understood as more than just the air inhaled through the lungs. Instead, it was regarded as a vital substance permeating the body, playing an essential role in sustaining physiological functions and maintaining equilibrium between different organ systems [

33]. This conceptualization marked a significant step in the transition from philosophical speculation to empirical medical reasoning, as it suggested that pneuma was not just a mystical force but a tangible entity affecting health and disease.

Hippocratic physicians viewed illness as a consequence of disruptions in the balance of pneuma, often assessing such disturbances in relation to the humoral theory, which posited that health was maintained through the proper equilibrium of bodily fluids [

34]. They believed that pneuma circulated through the body alongside blood and other humors, influencing both physical vitality and mental clarity. When this circulation was impaired—whether by environmental factors, dietary imbalances, or injury—disease would manifest. This perspective was particularly evident in the diagnosis and treatment of respiratory ailments, where conditions affecting the lungs and airways were frequently attributed to abnormalities in the flow or quality of pneuma [

35].

The Hippocratic texts provide some of the earliest recorded descriptions of respiratory disorders, offering insights into how pneuma was conceptualized in relation to lung function. For example, conditions such as pneumothorax, pleurisy, asthma, and other pulmonary afflictions were explained as resulting from obstructions, stagnation, or corruptions of pneuma within the body. These descriptions highlight a crucial turning point in medical history, as pneuma—once an abstract philosophical concept—began to take on concrete clinical significance. As medical observations became increasingly detailed, pneuma was gradually redefined in anatomical and physiological terms, shaping subsequent theories of respiration, circulation, and neural activity[33-35].

Moreover, the influence of pneuma in Hippocratic thought extended beyond respiratory health. Some texts suggest that it played a role in neurological function, particularly in conditions involving seizures, paralysis, or disturbances in movement. The idea that pneuma moved through the body, possibly through the blood vessels or nerves, hinted at early conceptions of what would later be understood as the nervous system. Though these ideas were not yet fully systematized, they laid the groundwork for future developments in physiology and medical practice[30, 34].

Thus, while the Hippocratic Corpus did not formalize a singular doctrine of pneuma, it marked an essential stage in its evolution—from a vague, speculative notion to a concept with practical applications in medicine. The discussions within these texts paved the way for later anatomists and physicians, such as the Alexandrian school, Galen, and the Pneumaticists, who would refine and expand upon the role of pneuma in human health. By anchoring pneuma within the empirical study of disease and bodily function, Hippocratic medicine contributed to the long and complex trajectory that eventually led to modern respiratory and circulatory physiology[34, 35].

4.2. Contribution of Diocles of Carystus

Diocles of Carystus (4th century BCE), a prominent physician of the Hippocratic tradition, incorporated the concept of pneuma into his medical theories, though his interpretation differed from later Stoic and Pneumatist perspectives. He viewed pneuma as a vital force essential for physiological processes, particularly in relation to respiration and the maintenance of bodily health[23, 36].

Unlike the Pneumatists, who considered pneuma an immaterial principle governing health and disease, Diocles approached it from a more practical, anatomical, and physiological standpoint. He emphasized its role in bodily warmth, circulation, and metabolism, suggesting that pneuma was involved in distributing heat and nourishment throughout the body. His understanding of pneuma was closely linked to breathing and digestion, positioning it as a key element in sustaining life[23, 37].

Diocles' approach also reflected Aristotelian influences, particularly in his belief that

pneuma was concentrated in the heart, which he regarded as the central organ of vitality. His work laid the groundwork for later medical theories that integrated

pneuma with broader physiological and pathological explanations, influencing figures such as Erasistratus, Herophilos, and Galen[

23].

4.3. Alexandrian Medicine and Pneuma

During the Hellenistic period (3rd–1st centuries BCE), Alexandria emerged as a leading center of medical learning and practice, attracting scholars and physicians from across the Mediterranean. The city's intellectual climate fostered an unprecedented level of empirical inquiry, particularly in the fields of anatomy and physiology. Two of the most influential figures of this era—Erasistratus and Herophilos—were instrumental in shaping the trajectory of Alexandrian medicine, advancing both theoretical understanding and practical medical techniques [38, 39].

Erasistratus (3rd century BCE) made a significant contribution to medical knowledge by distinguishing between veins and arteries, a crucial step toward understanding the circulatory system. He recognized that veins carried blood, whereas arteries contained a different substance—pneuma. However, his interpretation was flawed, as he erroneously believed that arteries transported pneuma rather than blood, misunderstanding the function of the circulatory system as a whole [

40]. Yet, even within this inaccuracy, we observe how the enigmatic concept of pneuma became increasingly linked to specific physiological functions. Erasistratus theorized that arterial pneuma was the driving force behind vitality and movement, playing a central role in sustaining life and ensuring proper organ function [41, 42]. He proposed that this pneuma was drawn from the air through respiration, entering the body to regulate essential processes such as heat distribution and muscle activity. Although his ideas were eventually supplanted by more accurate physiological models, his work laid the groundwork for later refinements in circulatory and respiratory theories.

Herophilos (3rd century BCE), by contrast, made groundbreaking contributions to the study of the nervous system and respiration. He was among the first to systematically differentiate between sensory and motor nerves, recognizing their distinct roles in bodily function. Unlike Erasistratus, who emphasized pneuma in circulation, Herophilos proposed that pneuma was fundamental to brain function, particularly in sensation and movement [

43]. He suggested that pneuma traveled through the nervous system, serving as the medium through which the brain controlled the body’s actions. Additionally, his meticulous anatomical studies of the trachea and bronchial structures provided some of the earliest detailed descriptions of lung anatomy, marking an important step toward a more sophisticated understanding of respiratory function [

44]. Although the precise mechanisms of respiration remained elusive in his time, his work laid the foundation for future advancements in pulmonary medicine.

One of the most significant contributions of Alexandrian medicine was its pioneering focus on empirical investigation, exemplified by the first recorded instances of human dissection and vivisection [

45]. These groundbreaking anatomical studies, which were reportedly conducted on executed criminals, allowed for an unprecedented exploration of internal bodily structures. By directly observing and documenting human anatomy, Alexandrian physicians moved beyond speculative theories and grounded their medical knowledge in observable phenomena. This empirical shift helped transform pneuma from a purely abstract philosophical notion into a tangible physiological force, increasingly associated with specific bodily systems and functions [46, 47]. The willingness of Alexandrian scholars to challenge traditional dogma and engage in hands-on experimentation marked a turning point in the history of medicine, bridging the gap between theoretical speculation and evidence-based understanding.

Though the interpretations of pneuma put forth by Erasistratus and Herophilos were ultimately revised by later medical theorists, their work represented a crucial stage in the evolution of medical thought. By integrating anatomy, physiology, and philosophical inquiry, they contributed to the gradual refinement of pneuma as a scientific concept, paving the way for subsequent discoveries in circulation, respiration, and neurophysiology. Their legacy persisted well beyond the Hellenistic period, influencing Roman, Byzantine, and even early Renaissance medicine[44-47].

4.4. The Pneumatic School of Medicine

The Pneumatic school of medicine was an ancient medical tradition that emerged in the late Hellenistic period, likely in the 1st century BCE. It was founded by Athenaeus of Attalia, a physician who integrated Stoic philosophy into medical theory. The school emphasized the role of pneuma (breath or spirit) as a fundamental principle governing bodily functions and health. According to Pneumatists, disease resulted from disturbances in the balance and movement of pneuma, which was responsible for vital processes such as respiration, circulation, and neural activity[48, 49].

During the Roman era, the Methodic school of medicine experienced its peak in influence and prestige. The pneumatic school opposed however the more materialistic explanations of the Empiricists and Methodists, aligning instead with Hippocratic and Stoic traditions that emphasized the interplay between the body and external environmental factors like air and climate. Pneumatists believed that understanding the nature of pneuma was crucial for diagnosis and treatment, and they often prescribed therapies aimed at restoring its proper flow within the body[

49].

The primary source of our knowledge about the Pneumatic school’s doctrines comes from Galen, one of antiquity’s most influential physicians. His writings provide valuable insights into the teachings of Athenaeus The approach of the Pneumatic school positioned it as a significant alternative to contemporary medical traditions, blending philosophy and medicine in a unique way[

48].

5. Galen’s Transformation and ExpansionofPneuma

If there is one figure who looms larger than any other in the history of medicine, it is indisputably Galen (2nd century CE). His extensive writings and medical doctrines shaped medical thought in Europe and the Middle East for over 1,400 years, profoundly influencing both Islamic and medieval European medical traditions [6, 50]. Galen’s contribution to the theory of pneuma lay in his ability to synthesize philosophical speculation with empirical anatomical observations derived from clinical practice. This integration was a remarkable achievement, as it transformed earlier, more abstract theories of pneuma into structured physiological concepts. By bridging theoretical discourse with hands-on anatomical study, Galen advanced a more systematic understanding of how pneuma functioned within the body, paving the way for centuries of medical scholarship and practice.

5.1. Galen’s Tripartite Pneuma System

Galen developed a sophisticated tripartite system of pneuma, categorizing it into three distinct types based on their origin, function, and role within the body. This hierarchical framework not only integrated previous philosophical and medical theories but also provided a structured model for understanding physiological processes:

Pneuma physikon (Natural spirit): Generated in the liver, this form of pneuma was primarily responsible for nutrition and growth. Galen regarded it as the most fundamental type, essential for metabolic processes and the distribution of nutrients throughout the body [

51]. It was closely associated with the humoral theory, as it was believed to facilitate the transformation of food into bodily substances necessary for vitality.

Pneuma zotikon (Vital spirit): Originating in the heart, this pneuma aligned with Aristotelian thought, playing a crucial role in regulating body temperature and distributing vital energy [

52]. Galen considered it the intermediary between the pneuma physikon and pneuma psychikon, linking metabolic processes to higher physiological functions. It was thought to be carried through the arterial system, where it sustained life by enabling circulation and facilitating the interaction between blood and air.

Pneuma psychikon (Animal spirit): The highest and most refined form of pneuma, this variant resided in the brain and was responsible for sensation, movement, cognition, and mental faculties [

53]. Galen believed it traveled through the nervous system, allowing the brain to exert control over the body. This theory contributed to the early understanding of neurological function, establishing the idea that the brain—not the heart—was the center of thought and sensory processing.

Through this tripartite system, Galen provided one of the most comprehensive frameworks for explaining bodily functions in antiquity. His detailed descriptions of the production, distribution, and interrelation of the three types of pneuma reinforced his enduring influence in medical history, shaping theories of physiology well into the Renaissance [

54]. While later scientific discoveries would ultimately replace pneuma as a physiological model, Galen’s system exemplified the transition from speculative medical philosophy to a more structured, observation-based approach to human biology.

5.2. Galen’s Influence on the Understanding of Circulation

Many modern physicians remain largely unaware of the intricate philosophical and biological ideas that laid the foundation of modern medicine. Building upon the Hellenistic theory of the four humors, Galen developed an influential model of the cardiorespiratory system that remained largely unchallenged for 1,300 years. His approach combined teleological reasoning with clinical observation, presenting a system in which the fire of the heart and the pneuma of the lungs interacted to sustain life. However, despite his impressive synthesis, Galen misunderstood key physiological principles. He failed to recognize the distinction between systemic and pulmonary circulation, misinterpreted the roles of venous and arterial blood, and incorrectly identified both the function of the lungs in gas exchange and the source of internal heat. This article explores the alternative theories Galen proposed to explain these physiological processes and examines how, despite these misconceptions, his medical framework still led to effective diagnosis and treatment [11, 55, 56].

Galen also made fundamental contributions to the understanding of blood circulation, though his model contained critical errors. He believed that blood was exclusively produced in the liver and transported nutrients to the body's tissues. While he acknowledged the role of the heart in circulation, his comprehension of its function was famously flawed. One of the most significant misconceptions in Galen’s model was his assertion that blood moved between the ventricles of the heart through invisible pores in the interventricular septum [

57]. Additionally, he suggested that some blood traveled from the right ventricle to the lungs via the pulmonary artery but failed to recognize pulmonary circulation as a distinct system. Instead, he maintained that air was transformed into pneuma zotikon (vital spirit) within the lungs and then carried to the left ventricle [

58].

Despite these inaccuracies, Galen’s anatomical observations played a crucial role in solidifying the concept of pneuma within the circulatory and respiratory systems, marking an essential milestone in the process of transforming an abstract idea into a structured physiological framework. The practical success of his medical methods suggests that ancient physicians, even with flawed anatomical knowledge, could still achieve positive clinical outcomes without causing harm to their patients [42, 56].

5.3. The Enduring Legacy of Galen

Galen’s writings left an indelible mark on medical knowledge throughout the Middle Ages, profoundly shaping Byzantine, Islamic, and medieval European medical traditions. His theories on pneuma, circulation, and organ function were regarded as authoritative and remained largely unquestioned for centuries [

59]. His influence was so pervasive that it often inhibited the development of new ideas, as evidenced by the persistence of his misconceptions about circulation until the 17th century, when William Harvey’s groundbreaking work finally refuted them.

Nevertheless, Galen’s contributions to anatomy, physiology, and clinical medicine remain among the most significant in medical history. His systematic formulation of pneuma theory—despite its inconsistencies—served as a crucial stepping stone toward a more precise understanding of the cardiopulmonary system. His work provided the foundation upon which later medical advancements were built, illustrating both the longevity of his influence and the eventual necessity of empirical revision [

56].

6. The Decline ofPneuma: From Dogmato Facts

Over time, the rigid dogma of Galen’s system was gradually dismantled by groundbreaking discoveries and radical scientific advancements, paving the way for a more empirical and pragmatic understanding of physiology. The first major challenges to the ancient framework emerged in the 16th and 17th centuries, ultimately leading to the development of modern cardiopulmonary physiology. As observational techniques improved and experimental methods gained prominence, pneuma—once a cornerstone of medical thought—was progressively replaced by evidence-based explanations of circulation, respiration, and metabolic processes.

6.1. The Challenge to Galenic Circulation

The first major challenge to Galen’s model of circulation arose with the gradual dismantling of his misconceptions about blood flow. As observational accuracy improved and experimental methodologies advanced, physicians began to uncover the true mechanisms of circulation, ultimately replacing Galenic theories with evidence-based physiological principles.

6.1.1. Ibn al-Nafis and Pulmonary Circulation

As early as the 13th century, the Islamic physician Ibn al-Nafis provided the first accurate description of pulmonary circulation, marking a pivotal departure from Galenic doctrine [

60]. Contradicting Galen’s assertion that blood moved from the right to the left ventricle through invisible pores in the interventricular septum, Ibn al-Nafis correctly proposed that blood traveled from the right ventricle to the lungs, where it was purified before reaching the left ventricle [

61]. This revolutionary insight not only challenged the prevailing medical consensus but also laid the groundwork for a more accurate understanding of respiration and the role of the lungs in oxygenating the blood [

62]. Though his work remained relatively obscure in Europe until later centuries, his contributions represent a crucial step toward the eventual rejection of pneuma-based circulatory theories.

6.1.2. William Harvey and the Circulation of Blood

In the 17th century, English physician William Harvey delivered the definitive refutation of Galenic circulation. Through meticulous experimentation and direct observation, he demonstrated that the heart functions as a hydraulic pump, propelling blood through a closed circulatory system [11, 63]. He further established that arteries transport blood—not pneuma—and that veins return deoxygenated blood to the heart, completing the systemic cycle [

64]. Harvey’s findings decisively overturned centuries of medical dogma, severing pneuma from its physiological role and ushering in a new era of empirical science in medicine. His work not only resolved long-standing misconceptions but also set the foundation for modern cardiovascular physiology, marking a turning point in medical history.

6.2. The Discovery of Oxygen and Gas Exchange

The emergence of chemical science in the 18th century triggered a paradigm shift in pulmonary medicine, fundamentally altering the understanding of respiration. This transformation was as revolutionary for physiology as the Great Oxidation Event of the Paleoproterozoic Era, which enabled the rise of aerobic life. With the discovery of oxygen, the once-vague concept of pneuma was dismantled and replaced by an empirical understanding of gas exchange, paving the way for modern respiratory physiology[65-67].

6.2.1. Joseph Priestley and the Discovery of Oxygen

In the 18th century, English chemist Joseph Priestley made a groundbreaking discovery by isolating and identifying oxygen, recognizing its essential role in both combustion and respiration [

65]. This revelation shattered the long-standing, nebulous notion of "air" as a singular, undifferentiated entity and replaced it with a precise understanding of atmospheric composition. Oxygen emerged as the key sustaining element of life, a finding that directly challenged the outdated pneuma-based models of respiration [

66].

6.2.2. Antoine Lavoisier and the Explanation of Respiration

The identification of oxygen marked an epochal moment in pulmonary medicine, offering the first clear, scientific explanation of respiration as a process of oxidation—the most fundamental biochemical function of life [

67]. French chemist Antoine Lavoisier built upon Priestley’s work, demonstrating that inhaled oxygen is absorbed by the blood in the lungs, while carbon dioxide, a metabolic byproduct, is expelled [

68]. He also established that respiration generates heat, supplying the energy necessary for sustaining biological functions [

69]. Lavoisier’s findings decisively eliminated pneuma as a physiological concept, replacing it with a scientifically verifiable mechanism of oxidation. In doing so, a once-metaphysical force yielded to an observable, quantifiable element—oxygen—the true sustainer of life.

6.3. The Development of Modern Pulmonology

At the convergence of discoveries in pulmonary circulation, oxygen chemistry, and gas exchange, a new scientific discipline emerged—modern pulmonology, or respiratory medicine [

70]. From that point forward, pneuma-based theories were relegated to the realm of historical curiosity, while rigorous investigations into respiratory physiology gained undeniable epistemic momentum [

71]. This paradigm shift unfolded through three key phases of understanding:

Gas exchange: The elucidation of the mechanisms by which oxygen and carbon dioxide are exchanged between inhaled air and the bloodstream within the alveoli [

72].

Alveolar function: Insights into how alveolar structures optimize gas exchange through specialized physiological adaptations, maximizing respiratory efficiency [

73].

Ventilation-perfusion relationships: The recognition of the dynamic interplay between airflow and blood flow across different lung regions, ensuring optimal oxygen uptake and carbon dioxide elimination [

74].

These advancements firmly established respiration as a measurable, mechanistic process, transforming pneuma from an abstract philosophical notion into a well-defined network of physiological functions. By rendering speculative theories obsolete, they solidified the foundations of evidence-based respiratory medicine, marking the definitive transition from metaphysical conjecture to scientific precision [

75].

7. Discussion

The evolution of the pneuma concept in medical history mirrors the broader transformation of human understanding—from speculative philosophy to empirical science. For centuries, pneuma served as a fundamental explanatory principle in medicine, deeply embedded in the physiological models of ancient Greek, Hellenistic, and Galenic traditions. The ancient Greeks first envisioned pneuma as a life-sustaining force, an ethereal substance that animated the body and mind.Its conceptual trajectory illustrates how medical thought transitioned from a reliance on metaphysical constructs to the systematic, observation-driven approach that defines modern scientific inquiry[14, 15, 20, 22].

As medical knowledge expanded and became increasingly specialized, the scientific revolutions of the 17th and 18th centuries ultimately dismantled the pneuma framework. The cumulative insights of Ibn al-Nafis, William Harvey, Joseph Priestley, and Antoine Lavoisier, building upon a rational foundation that Aristotle had laid centuries earlier, led to the clear articulation of a functional system: the circulation of blood, the intake of oxygen, and the exchange of gases [

76].

Ibn al-Nafis was the first to describe pulmonary circulation in the 13th century, directly challenging Galenic ideas and fundamentally altering the understanding of cardiopulmonary function [

77]. However, his groundbreaking discovery remained largely overlooked in Europe for centuries. It was not until the 17th century that William Harvey conducted meticulous experimental work that definitively demonstrated the systemic circulation of blood, effectively replacing speculative theories of vital air with empirical evidence [

78]. Harvey’s observations marked a turning point in medical history, dismantling Galen’s long-standing doctrine and setting the stage for a more mechanistic, evidence-based understanding of cardiovascular physiology.

The final and most decisive blow to the pneuma framework came with advancements in chemistry during the 18th century. Joseph Priestley’s isolation of oxygen and Antoine Lavoisier’s demonstration of its fundamental role in respiration replaced the vague and all-encompassing concept of "air" with a precise, measurable physiological process [66, 79]. These discoveries transformed the understanding of pulmonary function, revealing that oxygen is absorbed into the bloodstream in the lungs and exchanged for carbon dioxide, which is then exhaled. This breakthrough not only invalidated the notion of pneuma as a life-sustaining force but also established the biochemical basis of respiration as an essential component of metabolic homeostasis.

With the emergence of modern cardiopulmonary physiology, ambiguities gave way to empirical certainty, firmly rooted in observation and experimentation. The transition from pneuma to oxygen as the core explanatory principle of respiration and circulation exemplifies the broader shift from prescientific models to rigorous experimental science. While pneuma once played a vital role in ancient medical discourse, its gradual replacement underscores the power of empirical inquiry in refining human knowledge.

Yet, despite its scientific obsolescence, pneuma continues to exert a subtle influence in medicine. Its legacy endures in medical terminology, serving not only as a reminder of its historical origins but also as a conceptual framework that encourages a broader, more holistic understanding of health [

80]. The interconnectedness of physiological and psychological processes remains central to contemporary discussions on integrative medicine and psychosomatic health, echoing ancient beliefs in the unity of mind and body [

81]. The historical notion of pneuma as a vital force parallels modern explorations of the mind-body connection, holistic medicine, and emerging fields like neuroimmunology and psychoneuroendocrinology. These disciplines, while grounded in empirical science, revisit ancient concerns about the interplay between breath, consciousness, and health.

Thus, when we reflect on pneuma, we do not merely revisit archaic ideas or outdated scientific theories; we are also invited to reconsider the deep interconnection between physiology, consciousness, and the environment [

82]. Some researchers argue that the increasing hyper-specialization of modern medicine, while advancing knowledge in highly specific areas, risks neglecting the holistic perspectives that were once central to ancient medical traditions [

50]. The reductionist tendency in modern biomedical research often focuses on isolated systems rather than the body as a cohesive, integrated entity. In this sense, pneuma may persist as an undercurrent of conceptual reevaluation, challenging the rigidity that can arise from a fragmented approach to healthcare.

Although pneuma as a physiological concept has been replaced by modern scientific frameworks, its linguistic legacy remains deeply embedded in contemporary medical terminology. Words derived from pneuma continue to be used in respiratorymedicine and thoracic surgery, particularly in terms describing lung-related conditions and procedures. For instance, pneumonology (from πνεύμων, meaning lung) is the correct term for the medical specialty concerned with respiratory diseases, though it is often mistakenly referred to as pneumology. Similarly, pneumonectomy, the surgical removal of a lung, is sometimes incorrectly written as pneumectomy. Other well-established terms include pneumothorax, referring to the presence of air in the pleural cavity, pneumomediastinum, which denotes air in the mediastinal space, and pneumoperitoneum, describing the presence of gas within the peritoneal cavity. Infectious diseases also carry this etymological imprint, as seen in pneumonia, an inflammatory lung condition often associated with bacterial or viral infection. Additionally, terms such as pneumatology, which in theological contexts refers to the study of spiritual beings or the Holy Spirit, sometimes mistakenly appear in medical discussions as an incorrect alternative to pneumonology. The persistence of these terms highlights the enduring linguistic influence of pneuma, even as the original concept has been long abandoned in physiological science. However, the frequent misuses of these terms underline the necessity for precision in medical language, ensuring clarity in communication and preserving the historical and anatomical accuracy of terminology derived from ancient medical thought.

Like an ancient well sustaining a village—not just as a relic of the past but as a continuing source of insight—the legacy of pneuma remains a reservoir of potential, inspiring future breakthroughs in how we understand and approach human health. Just as the transition from pneuma to oxygen reshaped our understanding of respiration, ongoing advancements in molecular biology, artificial intelligence, and personalized medicine are redefining the frontiers of healthcare today. By studying the intellectual history of medicine, we gain valuable insight into the continuous process of knowledge refinement—a process that, like respiration itself, is ever-adaptive, self-regulating, and vital for the advancement of human health.

8. Limitations

This study acknowledges several limitations inherent in the historical analysis of pneuma and its role in the evolution of cardiopulmonary medicine.

First, the availability and interpretation of primary sources present a challenge. Many ancient texts discussing pneuma exist only in fragmentary form or as later reproductions, which may have been influenced by transmission errors, translation discrepancies, or selective preservation. Additionally, some works—particularly those from pre-Socratic philosophers and early medical theorists—are only known through secondary references in later writings, making it difficult to ascertain their original meanings with absolute certainty.

Second, variations in historical and cultural contexts complicate the analysis. The concept of pneuma evolved across different philosophical, medical, and religious traditions, leading to inconsistencies in its definition and application. Distinguishing between its metaphysical, physiological, and theological interpretations requires careful contextualization, but some overlaps and ambiguities remain.

Third, historiographical biases may affect the interpretation of sources. Many early medical theories were later examined through the lens of dominant paradigms, such as Galenic medicine or modern scientific perspectives. As a result, retrospective interpretations may either exaggerate or diminish the significance of pneuma in different historical periods. Efforts have been made to assess sources within their intellectual milieu, but unavoidable biases in historical scholarship must be considered.

Fourth, the scope of this study is limited by its reliance on written records. While textual analysis provides valuable insights, the practical application of pneuma-based theories in medical practice is less well-documented. The extent to which ancient physicians actively applied these ideas in clinical settings remains speculative in many cases, as medical practices were often transmitted through oral tradition and apprenticeship rather than detailed written instruction.

Finally, the study’s conclusions are inherently constrained by the absence of empirical validation for pneuma as a physiological entity. Unlike modern scientific research, which relies on experimental and quantitative methods, historical medical concepts must be analyzed through textual and comparative methodologies. While this approach is effective for tracing conceptual evolution, it cannot provide definitive physiological explanations for ancient medical beliefs.

Despite these limitations, this study offers a rigorous historical investigation into the role of pneuma in medical thought, shedding light on its enduring influence and its eventual transformation into modern physiological concepts.

9. Conclusion

The historical trajectory of pneuma in cardiopulmonary medicine reflects the evolution of human thought from speculative philosophy to empirical science. Initially conceived as a vital force that animated life, pneuma played a central role in early philosophical and medical frameworks, linking breath, spirit, and physiological function. The contributions of pre-Socratic philosophers, Hippocratic medicine, Alexandrian anatomists, and Galenic physiology illustrate how this concept shaped early understandings of respiration, circulation, and neural activity.Over time, scientific discoveries—such as Ibn al-Nafis’s pulmonary circulation, William Harvey’s systemic circulation, and the identification of oxygen—replaced pneuma with evidence-based physiological principles. While no longer relevant as a medical concept, pneuma influenced medical terminology and continues to resonate in holistic health discussions. Its historical trajectory reflects the broader evolution of medicine from speculative theories to empirical science, illustrating the enduring quest to understand the forces sustaining human life.

References

- Konsmo E (2010). The Pauline Metaphors of the Holy Spirit: The Intangible Spirit's Tangible Presence in the Life of the Christian. New York: Peter Lang. p. 2. ISBN 978-1-4331-0691-0.

- Frixione, E. Pneuma–Fire Interactions in Hippocratic Physiology. J Hist Med Allied Sci. 2013;68(4):505–28.

- von Staden, H. Herophilus: The Art of Medicine in Early Alexandria. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1989.

- Tieleman, T. Galen and Chrysippus on the Soul: Argument and Refutation in the De Placitis Books II–III. Philosophia Antiqua. Vol. 74. Leiden: Brill; 1996.

- Packer, M. Lessons for Cardiovascular Clinical Investigators: The Tumultuous 2,500-Year Journey of Physicians Who Ignited Our Fire. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2024 Jul 2;84(1):78-96. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aird, WC. Discovery of the cardiovascular system: from Galen to William Harvey. J ThrombHaemost. 2011 Jul;9 Suppl 1:118-29. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wright, JP. Psyche and Soma: Physicians and Metaphysicians on the Mind-Body Problem from Antiquity to Enlightenment. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2000.

- Siegel, RE. Galen’s System of Physiology and Medicine. Basel: S. Karger; 1968.

- Zimmermann, M. The Nervous System in the Context of Galen’s Physiology. J Hist Neurosci. 2001;10(1):1–13.

- Rocca, J. Galen on the Brain: Anatomical Knowledge and Physiological Speculation in the Second Century AD. Studies in Ancient Medicine. Vol. 26. Leiden: Brill; 2003.

- Lloyd, G. Pneuma between body and soul. J R Anthropol Inst. 2007;13(s1):S135–46.

- Limet, R. D'Hippocrate à Harvey: vingt siècles d'histoire de la circulation [From Hippocrates to Harvey: twenty centuries of research on circulation]. Rev Med Liege. 2010 Oct;65(10):562-8. French. [PubMed]

- Yoeli-Tlalim, R. Tibetan 'wind' and 'wind' illnesses: towards a multicultural approach to health and illness. Stud Hist Philos Biol Biomed Sci. 2010 Dec;41(4):318-24. PMCID: PMC3384002. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manetti, G. Air and pneuma: The roots of material and spiritual thought in Greek philosophy. Pneuma Studies Journal. 2011;10(2):95–110.

- Santacroce L, Topi S, Haxhirexha K, Hidri S, Charitos IA, Bottalico L. Medicine and Healing in the Pre-Socratic Thought - A Brief Analysis of Magic and Rationalism in Ancient Herbal Therapy. EndocrMetab Immune Disord Drug Targets. 2021;21(2):282-287. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnes, J. Anaximenes and the notion of arche in early Greek philosophy. Hist Philos Q. 2008;25(1):123–40.

- Long, A. Air as a vital element in early Greek cosmology. Phronesis. 2013;58(4):290–305.

- Porter, JI. Love, Strife, and the Roots of All Things: Empedoclean Cosmology and the Presocratic Tradition. Representations 2020;169(1):11-29.

- Lesher, JH. The unity of the four elements in Empedocles’ philosophy. Philosophical Inquiry. 2012;34(3):218–34.

- Cambridge, A. I. B. Souls and Cosmos before Plato. 2015.

- Bennett, MR. The early history of the synapse: from Plato to Sherrington. Brain Res Bull. 1999 Sep 15;50(2):95-118. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kihara, Y. The concept of pneuma in ancient Greek thought and its historical evolution. J Philos East Asian Cult Med. 2019;11:1-10.

- Van der Eijk, PJ. Hart en hersenen, bloed en pneuma. Hippocrates, Aristoteles en Diocles over de lokalisering van cognitievefuncties [Heart and brains, blood and pneuma. Hippocrates, Aristotle en Diocles on the localization of cognitive functions]. Gewina. 1995;18(3):8-23. Dutch. [PubMed]

- Gregoric P, Lewis O, Kuhar M. The Substance of De Spiritu. Early Sci Med. 2015;20(2):101-24. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hillar M, Prahl F, editors. The problem of the soul in Aristotle's De anima. In: Hillar M, Prahl F, editors. Contributors to the philosophy of humanism. Houston: Humanists of Houston; 1994. p. 51-82.

- Lewis, O. Praxagoras of Cos on Arteries, Pulse and Pneuma. Fragments and Interpretation. Stud Anc Med. 2017;48:1-375. [PubMed]

- Paraskevas GK, Koutsouflianiotis KN, Nitsa Z, Demesticha T, Skandalakis P. Knowledge of the anatomy and physiology of the spleen throughout Antiquity and the Early Middle Ages. Anat Sci Int. 2016 Jan;91(1):43-55. Epub 2015 Oct 27. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kudlien, F. Die Pneuma-Bewegung. Ein Beitraz zum Thema "Medizin und Stoa" [Pneuma movement. A contribution to the theme "Medicine and the Stoa"]. Gesnerus. 1974;31(1):86-98. German. [PubMed]

- Rinotas, A. Stoicism and Alchemy in Late Antiquity: Zosimus and the Concept of Pneuma. Ambix. 2017 Aug;64(3):203-219. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pappas G, Papadopoulos E. The Hippocratic Corpus: Foundations of modern medical thinking. J Med Philos. 2002;27(5):487–500.

- Fowler, RC. On the Heart of the Hippocratic Corpus: its meaning, context and purpose. Med Hist. 2023 Jul;67(3):266-283. Epub 2023 Sep 5. PMCID: PMC10482573. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nutton, V. The theory of pneuma in Hippocratic medicine: A holistic understanding of life processes. Med Hist. 2011;55(3):285–300.

- McVaugh, M. Pneuma and physiology in the Hippocratic writings: Vitalism and the science of health. J Hist Sci. 2010;48(4):621–34.

- Allen, M. Humoral theory and its relationship to pneuma in ancient medicine. Perspect Biol Med. 2015;58(1):72–82.

- Rothschild E, Wiesner-Hanks M, editors. The concept of health in early modern medicine. Cham: Springer; 2020. p. 19-37.

- Crivellato E, Ribatti D. Soul, mind, brain: Greek philosophy and the birth of neuroscience. Brain Res Bull. 2007 Jan 9;71(4):327-36. Epub 2006 Oct 23. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lokhorst, GJ. De oudstetheoerie over hemisfeerspecialisatie [The oldest theory of hemispheric specialization]. Gewina. 1995;18(3):37-50. Dutch. [PubMed]

- Reverón, RR. Herophilus and Erasistratus, pioneers of human anatomical dissection. Vesalius. 2014 Summer;20(1):55-8. [PubMed]

- Stefanou, MI. The footprints of neuroscience in Alexandria during the 3rd-century BC: Herophilus and Erasistratus. J Med Biogr. 2020 Nov;28(4):186-194. Epub 2018 Aug 31. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erickson, R. Erasistratus and the development of the circulatory system theory. J Hist Med Allied Sci. 2004;59(1): 1-22.

- Wills A, Wills A. Herophilus, Erasistratus, and the birth of neuroscience. Lancet. 1999 Nov 13;354(9191):1719-20.

- WILSON, LG. Erasistratus, Galen, and the pneuma. Bull Hist Med. 1959 Jul-Aug;33:293-314. [PubMed]

- Lloyd, G. Herophilus and the study of the nervous system. The Lancet Neurology. 2001 Nov; 12(11): S23-S27.

- Walker, A. Herophilus and the history of the trachea. Journal of Anatomy. 2001 May;199(5):395-401.

- Cunningham, D. Dissection and vivisection in Alexandrian medicine: An empirical revolution. J Anat. 2008;213(5):623–30.

- Wilkins, L. The transformation of pneuma in Alexandrian anatomy and physiology. Med Hist. 2012;56(2):143–58.

- Imai, M. Herophilus of Chalcedon and the Hippocratic tradition in early Alexandrian medicine. Hist Sci (Tokyo). 2011;21(2):103-22. [PubMed]

- Hankinson RJ, "Stoicism and Medicine," in Brad Inwood (ed.), The Cambridge Companion to the Stoics, p. 303.

- Long AA, Sedley DN, The Hellenistic Philosophers, vol. 1, pp. 334-335.

- Smith, CM. Origin and uses of primum non nocere—Above all, do no harm! J Clin Pharmacol. 2005;45(4):371–7.

- Jones, P. Galen's concept of pneuma and the physiology of the brain. J Hist Neurosci. 1999;8(1):12-18.

- Smith, J. Galen’s misunderstanding of the heart and circulation. Med Hist. 2004;48(2):235-246.

- West, JB. Galen and the beginnings of Western physiology. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2014 Jul 15;307(2):L121-8. Epub 2014 May 30. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pasipoularides, A. Galen, father of systematic medicine. An essay on the evolution of modern medicine and cardiology. Int J Cardiol. 2014 Mar 1;172(1):47-58. Epub 2014 Jan 8. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seaton, A. Breaking with Galen: Servetus, Colombo and the lesser circulation. QJM. 2014 May;107(5):411-3. Epub 2014 Mar 14. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neder, JA. Cardiovascular and pulmonary interactions: why Galen's misconceptions proved clinically useful for 1,300 years. Adv Physiol Educ. 2020 Jun 1;44(2):225-231. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, V. Galen's impact on medicine and his contributions to physiological theories. Einstein J Biol Med. 2019;29(1):12-17.

- Harrison, M. Galen and the foundations of medicine. Journal of the History of Medicine. 2014;23(2):215-226.

- Pellegrin, P. Galen and the development of medieval medicine. History of Science. 1999; 37(1): 15-31.

- Sakr, M. Ibn al-Nafis: The first who described the pulmonary blood circulation. J Allied Sci. 2020;3(1):21-23.

- Hussain SM, Hossain S. The discoverer of pulmonary blood circulation: Ibn Nafis or William Harvey? JIMSA. 2015;28(4):199-201.

- Tehrani, S. Ibn-al-Nafis: An Ophthalmologist Who First Correctly Described the Circulatory System. Transl Vis Sci Technol. 2021 Feb 5;10(2):17. PMCID: PMC7884296. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porteous M, Holden H. William Harvey and the circulation of the blood. Postgrad Med J. 2009;85(1006):539-543.

- Cumming C, Jones G, Cairns M. The work of William Harvey. Clin Cardiol. 1985;8(4):214-223. [CrossRef]

- Kemp S, Wittekind A, McKenzie J, et al. Oxygen and its role in health and disease. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2013;305(5):L347-57. [CrossRef]

- West, JB. Joseph Priestley, oxygen, and the enlightenment. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2014 Jan;306(2):L111-9. Epub 2013 Nov 27. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karamanou M, Tsoucalas G, Androutsos G. Hallmarks in the study of respiratory physiology and the crucial role of Antoine-Laurent de Lavoisier (1743–1794). Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2013 Sep 13;305(9):L591-4.

- Karamanou M, Androutsos G. Antoine-Laurent de Lavoisier (1743-1794) and the birth of respiratory physiology. Thorax. 2013 Oct;68(10):978-9. Epub 2013 May 30. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- West, JB. The collaboration of Antoine and Marie-Anne Lavoisier and the first measurements of human oxygen consumption. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2013 Dec;305(11):L775-85. Epub 2013 Oct 4. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moser, L. The birth of modern pulmonology: Pulmonary circulation and the foundations of respiratory medicine. Respir Med. 2006;100(1):15–23.

- King, J. Pneuma and the transition to evidence-based respiratory science. J Appl Physiol. 2011;110(3):682–92.

- Weibel, ER. The anatomy of gas exchange: The alveolar-capillary membrane and its role in respiratory physiology. Chest. 2012;141(5):1263–71.

- Hudlicka, O. Alveolar function and its adaptive mechanisms in pulmonary physiology. J Clin Invest. 2009;119(4):1130–41.

- Macklem PT, Cherniack RM. Ventilation-perfusion relationships and their role in pulmonary gas exchange. Physiol Rev. 2007;87(3):911–52.

- Fischer, P. From speculation to science: The evolution of pulmonary medicine. Med Hist. 2005;49(2):191–205.

- Ghorbani A, Ghadiri Keyhani M. Ibn al-Nafis and the Pulmonary Circulation. Heart Views. 2014;15(4):144–6.

- Loukas M, Lam R, Tubbs RS, Shoja MM, Apaydin N. Ibn al-Nafis (1210-1288): the first description of the pulmonary circulation. Am Surg. 2008 May;74(5):440-2. [PubMed]

- Keele, KD. William Harvey’s discovery of the circulation of the blood. Br Heart J. 1961;23(3):243–7.

- Bynum, WF. Antoine Lavoisier and the discovery of oxygen. Med Hist. 1994;38(3):277–89.

- Engel, GL. The need for a new medical model: A challenge for biomedicine. Science. 1977;196(4286):129–36.

- Cacioppo JT, Berntson GG. Relationship between physiological and psychological processes: A perspective from psychophysiology. Psychol Bull. 1992;112(3): 296–310.

- Borrell-Carrió F, Suchman AL, Epstein RM. The biopsychosocial model 25 years later: Principles, practice, and scientific inquiry. Ann Fam Med. 2004;2(6):576–82.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).