1. Introduction

Global climate change affects the regional climate, resulting in heavy precipitation and river flooding. Strong climatic contrasts over Europe - northern and southern air currents over 2,000 km, high temperatures in the Mediterranean region, and polar air over the North Sea - led to massive moisture transport to eastern Central Europe and intense precipitation accumulation in the Carpathian Vault and the Northern Alps. The situation was exacerbated by climate change, which caused the Mediterranean Sea to warm up and the atmosphere to absorb more moisture, leading to more prolonged precipitation. In 2024 Mediterranean surface temperatures were at record levels, reaching between 25 °C and almost 30 °C in the northern Mediterranean region in mid-September. This meant that the temperature values were in some cases well above 4 °C above the long-term average. As a result, flooding in Central and Eastern Europe began on Friday, September 13, 2024, triggered by Cyclone "Boris", which caused severe cold and precipitation across most European countries.

According to the meteorological agency of Spain, in just a few hours in a number of places in the country the amount of precipitation equivalent to an annual indicator fell at the end of October 2024. In Chiva, west of Valencia, the agency recorded at least 491 liters of rainfall per square meter. This deluge, associated with the meteorological phenomenon known as "cold fall" (an isolated depression in altitude), forced several rivers out of their channels and caused the sudden formation of massive mudflows.

Therefore, it is essential to study the hydrological processes in rivers using mathematical modeling to construct digital twins of rivers. It is important for digital twin developers to perform real-time computations. There are several recent works in this area.

Several recent studies have demonstrated the potential of digital twin systems to enhance the modeling of hydrological processes under climate change. For example, the University of Trento developed a digital twin of the Adige River Basin in Italy to account for anthropogenic changes in reservoir dynamics [

1], while the Digital Twin Earth (DTE) model incorporated high-resolution Earth observation data to simulate soil moisture, precipitation, and river discharge for improved flood forecasting [

2].

A national scale model for Denmark was also introduced to function as a real-time digital twin for flood risk prediction and agricultural planning under climate extremes. The so-called GEUS, Denmark system delivered 5 terabytes of hydrological model data to the portal, with robust calibration methods and hybrid machine learning being key parts [

3].

The article of authors from UK Center for Ecology and Hydrology, Lancaster, UK, reflects on the role of data science in digital twins of the natural environment, with particular attention on how resultant data models can work alongside the rich legacy of process models that exist in this domain. The authors seek to unravel the complex two-way relationship between data and understanding of processes [

4].

From a mathematical point of view, the problems of studying flood processes can be reduced to solving forward and inverse problems in the field of hydrological processes using the equations of Shallow Water Theory [

5].

Physics-Informed Neural Networks (PINNs), a key component of digital twins, enable real-time calculations and have been the subject of significant recent advancements [

6,

7,

8]. PINNs embed the residual of partial differential equations (PDE) in the loss function of the neural network. They have been used successfully to solve various forward and inverse PDE problems [

9,

10,

11].

The modern theory of solving inverse problems for hyperbolic equations is covered in the works of the authors [

12,

13]. Some early work in the field of numerical solutions of inverse problems in the field of hydrology is known [

14,

15] using various mathematical methods to solve the Saint-Venant equations [

13,

16,

17].

Earlier research was also carried out to investigate the possibilities of using PINNs for solving hydrological problems, in particular for approximation of the 1D equation of the shallow water theory. As a rule, model problems were considered.

Several studies by scientific groups from the USA [

18,

19] demonstrated that PINNs successfully assimilated various types of observation and directly solved the 1D Saint-Venant equations.

The authors performed flow simulations over a floodplain and along an open channel in several synthetic case studies. PINN performance was evaluated against analytical solutions and numerical models. The results indicated that the PINN solutions of water depth had satisfactory accuracy with assimilated limited observations.

A scientific group from Ecuador investigated the numerical solution of a 1D differential equation to predict water surface profiles in a river, as well as to estimate the so-called roughness parameter [

20]. Then a real mountain river morphology, the so-called Step-pool, was studied. PINN models were implemented in the TensorFlow framework using two neural networks. Different numbers of layers and neurons per hidden layer were tested, as well as different activation functions.

A 2D model for "Dam break case" was analyzed in the Ph.D. thesis [

21]. The purpose of this work was to investigate the possibility of using PINNs to approximate shallow water equations (SWE), a PDE system that simulates free-surface flow problems. A wide variety of benchmark problems, selected for both steady-state solutions and Riemann problems of increasing complexity, were examined.

Another important direction is the study of filtration in porous media, including the Darcy and Richards equations.

The PINN method was presented to solve the coupled Darcy equation and the advection-dispersion equation (ADE) and was tested in a range of Pe numbers. For coupled Darcy flow and ADE with space-dependent hydraulic conductivity and velocity fields, PINN solutions for the hydraulic head and concentration were found to agree well with numerical solutions obtained with the finite-volume method [

22].

Thanks to the PINN method, the numerical results obtained in real time can be used for subsequent numerical modeling of the silting of river channels. Predicting indicators is important in preventing river pollution from sedimentation. The paper [

23] proposed a comparative analysis of the PINN method and numerical simulation to estimate indicators of velocity, pressure, and density in the aquatic environment.

The partial differential equation for soil–water infiltration has been combined with the PINN-based neural network to obtain a numerical analysis of the soil–water infiltration process.

The results indicated that compared to the traditional numerical method, the proposed PINN-based method for the numerical investigation of the vertical infiltration of soil and water had a smaller error and could obtain more accurate numerical results. During vertical infiltration of water in the different soil types, the light soil was the fastest, the heavy soil the second, and the medium soil the slowest [

24].

The Water Retention curves (WRCs) and Hydraulic Conductivity Functions (HCFs) are critical soil-specific characteristics necessary for modeling the movement of water in soils using the Richardson- Richards equation (RRE). Well-established laboratory measurement methods for WRCs and HCFs are usually not suitable to simulate field-scale soil moisture dynamics due to the scale mismatch. The inverse solution of the RRE must be used to estimate the WRCs and HCFs from the field-measured data. The authors [

25,

26] proposed a PINN framework for the inverse solution of RRE and the estimation of WRC and HCF only from volumetric measurements of water content. The proposed framework does not need initial and boundary conditions, which are rarely available in real applications.

The authors of the paper [

27] investigated the application of PINNs to inverse problems in unsaturated groundwater flow. PINNs have been applied to the types of unsaturated groundwater flow problems modeled with the Richards partial differential equation and the van Genuchten constitutive model. The inverse problem has been formulated as a problem with known or measured values of the solution to the Richards equation at several spatio-temporal instances, and unknown values of the solution in the rest of the problem domain and unknown parameters of the van Genuchten model. PINNs solved inverse problems by reformulating the loss function of a deep neural network so that it simultaneously aims to match the measured data and estimate the unknown values at a set of collocation points distributed across the problem domain.

The paper [

28] proposed an adaptive inverse PINN applied to different transport models, from diffusion to advection-diffusion-reaction and mobile-immobile transport models for porous materials. Once a suitable PINN was established to solve the forward problem, the transport parameters were added as trainable parameters, and the reference data were added to the cost function. It was found that, for the inverse problem to converge to the correct solution, the different components of the loss function (data mismatch, initial conditions, boundary conditions, and residual of the transport equation) need to be adaptively weighted as a function of the training iteration (epoch).

In study [

29], the authors proposed a new method, gradient-enhanced physics-informed neural networks (gPINNs), to improve the accuracy of PINNs. gPINNs leverage the gradient information of the PDE residual and embed the gradient into the loss function. gPINNs were extensively tested and demonstrated their effectiveness in both forward and inverse PDE problems. The numerical results showed that gPINN performs better than PINN with fewer training points.

The paper [

30] addressed the peridynamic inverse problem of determining the horizon size of the kernel function in a 1D model of a linear microelastic material. The authors explored different kernel functions, including V-shaped, distributed, and tent kernels. The paper presents numerical experiments using PINNs to learn the horizon parameter for problems in one- and two-dimensional spatial dimensions.

The use of PINN for solving SWE on the sphere in a meteorological context was proposed in [

31]. PINNs have been trained to satisfy the differential equations along with the prescribed initial and boundary data, and thus can be seen as an alternative approach to solving differential equations compared to traditional numerical approaches such as finite difference, finite volume or spectral methods.

Recent studies have explored the use of PINNs and other ML-based methods for modeling climate-driven processes in PDEs, combining physical constraints with data-driven learning [

6,

7,

8,

32,

33].

A new area in the development of PINN architectures is related to the direction of evolutionary deep neural networks [

34,

35,

36,

37].

Currently, there are other approaches to building the PINN architecture based on Deep Operator Neural Networks (DeepOnet) [

38] and Fourier Neural Operators (FNO) [

39]. But these architectures are more complicated in terms of software implementation.

The process of training neural networks requires datasets that cannot always be obtained from an experiment or laboratory. The synthetic data obtained from the physical modeling can be used for this purpose. These are artificially generated data sets that are created when real hydrological data is either not available at all or is very rare or expensive to obtain.

Many fully physics-solving and reduced physics hydrodynamic models are available in numerical codes (Delft3D [

40], ParFlow [

41], LISFLOOD-FP [

42], WRF-Hydro [

43], HEC-RAS [

44]).

The synthetic data for training neural networks can be obtained using one of these open source codes.

Previously, different numerical methods have been developed to solve the Saint-Venant equation in 1D/2D formulations. Among them, the authors could emphasize the semi-implicit finite-difference method [

45,

46]. In the paper a simple initial boundary value problem for the shallow-water equations in one space dimension was considered [

47]. The authors discretized the problem in space by the standard Galerkin finite element method on a quasiuniform mesh and temporally by the classical four-stage, fourth-order, explicit Runge–Kutta scheme.

The finite-element method was combined with the classical 4th order accurate, explicit Runge-Kutta time-stepping procedure. The authors considered the one-dimensional Shallow Water Equations in a finite channel with variable bottom topography [

48].

The Delft3D modeling code is very popular among hydrologists due to the availability of open source code, pre / post processors, and a wide range of many physical models to describe hydrological processes.

The Delft3D modeling code is widely used by hydrologists due to its open source availability, pre / post processors, and broad library of physical models, and has been applied, for example, to simulate temperature stratification and ice formation in deep lakes such as Lake Teletskoye [

49].

A new feasible bank erosion model was developed and successfully implemented in Delft3D software code [

50]. The developed model considered physical bank erosion processes to a greater extent than previous models. Model performance was assessed by comparison with a previously reported experiment in an open-channel bend flume from a mobile bed and bank laboratory.

The performance of two widely used hydrodynamic models (2D HEC-RAS and Delft3D-flexible mesh) was compared to predict the total water level (TWL) in Delaware Bay, USA in the study [

51]. Based on a previously established model configuration, the authors simulated Hurricane Sandy and Isabel that affected the Bay and caused considerable damage and economic losses. The model was then evaluated with tidal analysis, comparing observed and simulated TWL, and spatio-temporal variations of TWL were analyzed through scenario-based simulations.

The Delft3D modeling code was used to identify and select the optimal living shoreline structure for a complex inlet and bay system at Carancahua Bay, Texas [

52]. To achieve this goal, an extensive array of sensors was deployed to collect hydrodynamic and geotechnical data in the field, and historical shoreline changes were assessed using image analysis. The measured data were then used to parameterize and validate the baseline Delft3D model.

In the study, the process-based modeling approach was applied to assess changes in hydrodynamics and sediment dynamics resulting from climate change and engineering scenarios [

53]. 2DH numerical model based on Delft3D FM was used to describe sediment dynamics and simulate the sediment budget and patterns in SSC, and turbidity levels.

In the study [

54], Sandy storylines were created to assess the compound coastal flooding on critical infrastructure in New York City under different scenarios, including the effects of climate change (in the storm and through the increase in sea level) and internal variability (variations in the intensity and location of the storm). A calibrated global hydrodynamic model based on Delft3D Flexible Mesh was used as the global tide and surge model.

The paper [

55] aims to assess the impact of the high-dyke system on water level fluctuations and tidal propagation in the branches of the Mekong River. A coupled 1-D to 2-D unstructured grid using Delft3D Flexible Mesh software was developed. The results showed that the inclusion of high dykes changes the percentages of seaward outflow through the different Mekong branches and modifies the seazonal flow distribution across low- and high-flow periods.

In the study [

56] three methods (structural mesh encryption, suspension mesh and nonstructural mesh) based on Delft3D were compared and the optimization scheme was applied to a real bridge project. The unstructured mesh (Delft3D Flexible Mesh) scheme was unable to capture the oscillations in the wake flow behind the bridge piers. However, the application of the optimized scheme in bridge engineering demonstrated its practical value.

The purpose of this work is to develop an effective PINN model for solving 2D forward and inverse problems on the example of hydrological processes in a model channel with a given geometric parameters using synthetic data obtained from Delft3D open source hydrological code. PINN will be used to approximate the 2D Saint-Venant equations and to predict the inverse problem of finding the roughness coefficient.

The paper is organized as follows.

Section 1 contains an Introduction that provides a brief overview of the research area.

Section 2 covers the Materials and Methods. These are General Mathematical model for hydrological problem (

Section 2.1), Formulation of the Inverse Coefficient Problem (

Section 2.2), Finite difference discretization of Saint-Venant equations (

Section 2.3).

Section 3 covers Neural Network Architecture and the description of the Loss Function in machine learning.

Section 4 covers Regularization methods and Optimization problem.

Section 5 covers Definition of the problem. These are definitions for 1D problem (

Section 6.1), for 2D forward problem (

Section 6.2).

Section 6 covers the used approach.

Section 7 covers main Results. The results of numerical computations for all types of described models and their combinations are analyzed.

Section 8 covers the Discussion, where both the results obtained and the hardware implementation are discussed. In the end there are Conclusions and plans to conduct further research.

3. Neural Network Architecture

In the framework of this paper, the architecture of a Fully Connected Neural Network (FCNN) is considered to construct a physically-informed neural network for modeling various simple flows. For the neural network the following concepts are introduced: an input layer with neurons with features specified at the input in the form of point coordinates and discrete time values, the several hidden layers with neurons, the output layer with neurons.

The network also incorporates initial and boundary conditions, a point cloud representing the computational domain, and a loss function based on the continuity and momentum equations.

Such a physics-informed neural network consists of three main blocks. The first part includes a module for calculating residual summands for partial differential equations or the relative error of the solution in L1-L2 norm, as well as errors for initial and boundary conditions. The parameters for the FCNN are determined by finding the minimum for the overall loss function. The inputs for the neural network are converted into corresponding outputs. The second part is a FCNN with physical data, which takes the output function’s fields and calculates their derivatives using the initial equations for motion and continuity for fluid mechanics problems. The boundary and initial conditions, as well as the observational data from the experiment, are also evaluated.

The last step is the backpropagation mechanism, which minimizes the loss function using a given optimizer (for example, Adam and L-BFGS-B) according to some learning rate to obtain the optimal parameters for the neural network.

3.1. Mathematical Model for Neural Network

In our approach, we consider a FCNN of L layers and neurons in the kth layer. The weight matrix and bias vector in the kth layer (1<k<L) are denoted by and . The input vector is indicated by and the output vector in the k th layer is indicated by and .

We denote the activation function by , which is applied layer-wise along with the scalable parameters. is responsible for the slope of activation function in each hidden-layer and thereby increasing the training speed. Such locally adaptive activation functions enhance the learning capacity of the network, especially during the early training period.

The

- hidden layer of FCNN is defined as

In general, the parameterized conservation law is given by

We solve forward problems where solutions of partial differential equations are inferred given fixed model parameters as well as inverse problems, where the unknown parameters should be found from the observed or synthetic data.

The given mathematical model is converted into a surrogate model. More specifically, a given problem of solving a PDE is converted into a minimization problem where the global minimum of the loss function corresponds to the solution of the PDE. The loss function can be defined using training data points like initial and boundary conditions and the residual of the given PDE.

The main hyperparameters for the PINN are the following:

The number of layers and neurons is shown in

Table 2.

The function of activation: tanh

The optimizers are Adam and L-BFGS on different stages for improving convergence

The final number of points are: num domain = 500, num boundary = 200

The number of random method points =10000

The kernel initializer for the weights in a neural network: Glorot uniform

Taking into account the characteristic scales, the weighting coefficients were set equal to 1

The final number of points in the calculation domain was chosen on the basis of the predicted water surface level values obtained and the available RAM on the Nvidia GPU card.

Increasing the number of points resulted in a significant increase in training time without a noticeable improvement in accuracy and a decrease in the stability of calculations. Reducing the number of points resulted in a significant difference compared to synthetic data. The simplest example of a FCNN for PINN is shown in

Figure 1.

3.2. The Loss Function Value

The loss function value is formed by summation of 3 components of errors for residuals of equations, boundary and initial conditions. The MSE metric is used to calculate the error.

The loss function for the 1D model is:

Here is the loss function for the equations, is the loss function for the boundary conditions, is the loss function for the initial conditions, is the dimensionless residual of the i-th equation at the n-th point, is the number of points inside the computational domain, , , are the number of points at inlet, at outlet and for the initial conditions, , , are the specified values of the discharge and the area of water section in the boundary and initial conditions, , are the weights also used for non-dimensionalization.

The loss function for the 2D model is:

Here

is the loss function for the equations,

is the loss function for the boundary conditions,

is the dimensionless residual of the

i-th equation at the

n-th point,

is the number of points inside the computational domain,

,

are the number of points at inlet and at outlet,

,

,

are specified values of velocities and depth in boundary conditions,

,

are the weights also used for non-dimensionalization.

Similarly, MSE values are calculated for the values of the magnitude functions at the boundaries of the computational domain and at the initial moment of time.

To approach the true solution, PINNs embed the PDEs into their loss function.

The neural network was also used to solve the inverse problem - finding the roughness coefficient n. It turned out to be most effective to use the new value as the desired variable and to restore the roughness coefficient n after the solution.

Since a variant of Newton’s method is used in the solution process, it is intuitively clear that calculating the derivative of a linear function is preferable. Morever, enters the equations linearly.

The main approaches and parameters of the results presented in the further presented solutions of problems using PINN methods are given in the

Table 3.

The description of approximation theory and error analysis for PINNs has been cited in the article [

60] with Theorem that showed that feed-forward neural nets (FNNs) with enough neurons could simultaneously and uniformly approximate any function and its partial derivatives.

9. Conclusions

The posed forward and inverse hydrological problems based on the Saint-Venant equations using PINNs were successfully solved for test examples. However, our results have shown that the computational costs for solving these problems are significantly higher than those of traditional approaches, even when using Nvidia GPUs.

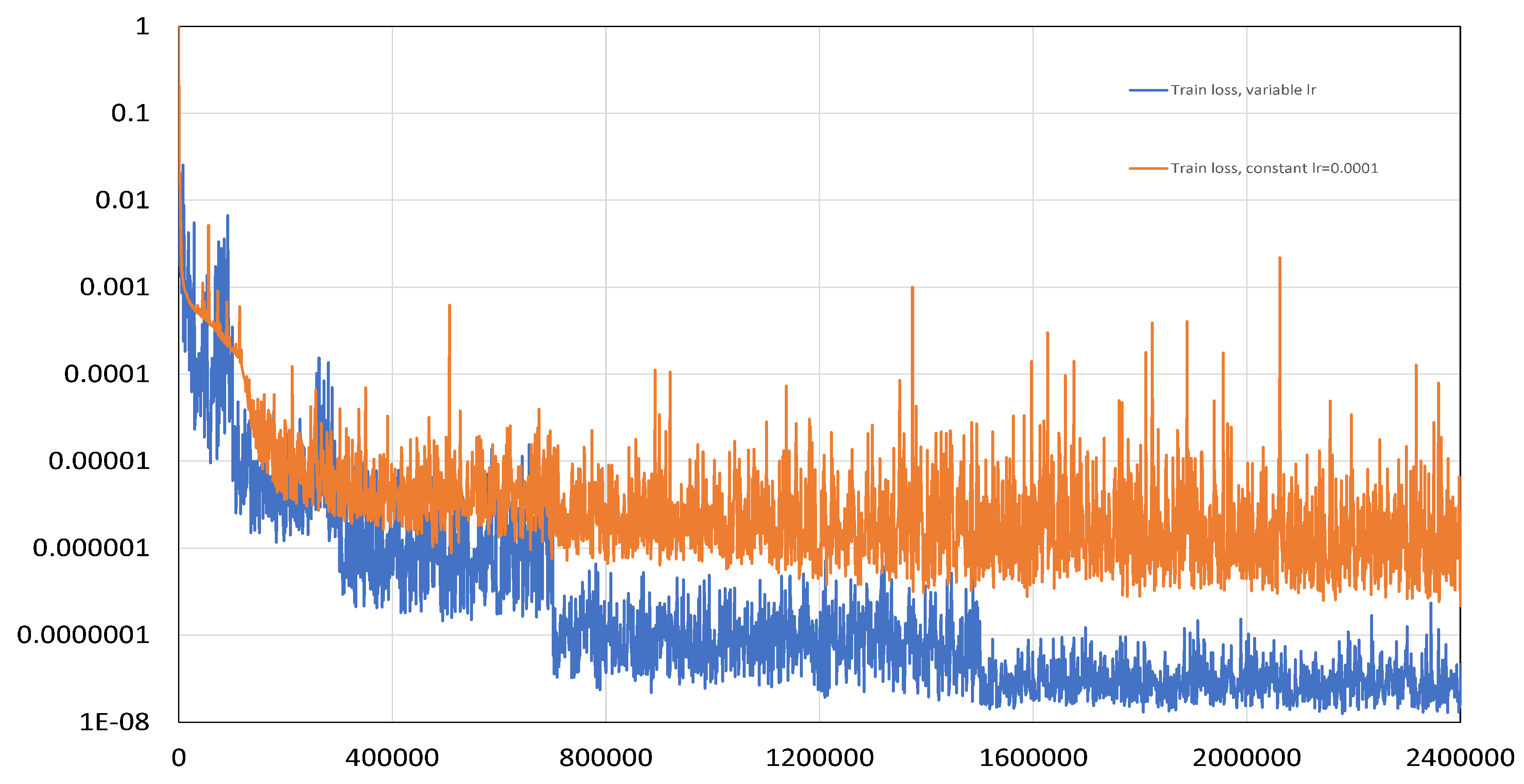

The simulations have shown that training with a constant learning rate is inferior in efficiency to training with a variable learning rate, which should gradually decrease during the iteration process.

It seems that the creation of an automatic procedure for changing the learning rate, based on physical principles, will be extremely useful for increasing efficiency.

The novelty in our work was that using PINN, we investigated the flow in a channel with a sharply changing bottom surface, which may be more complex than in real rivers.

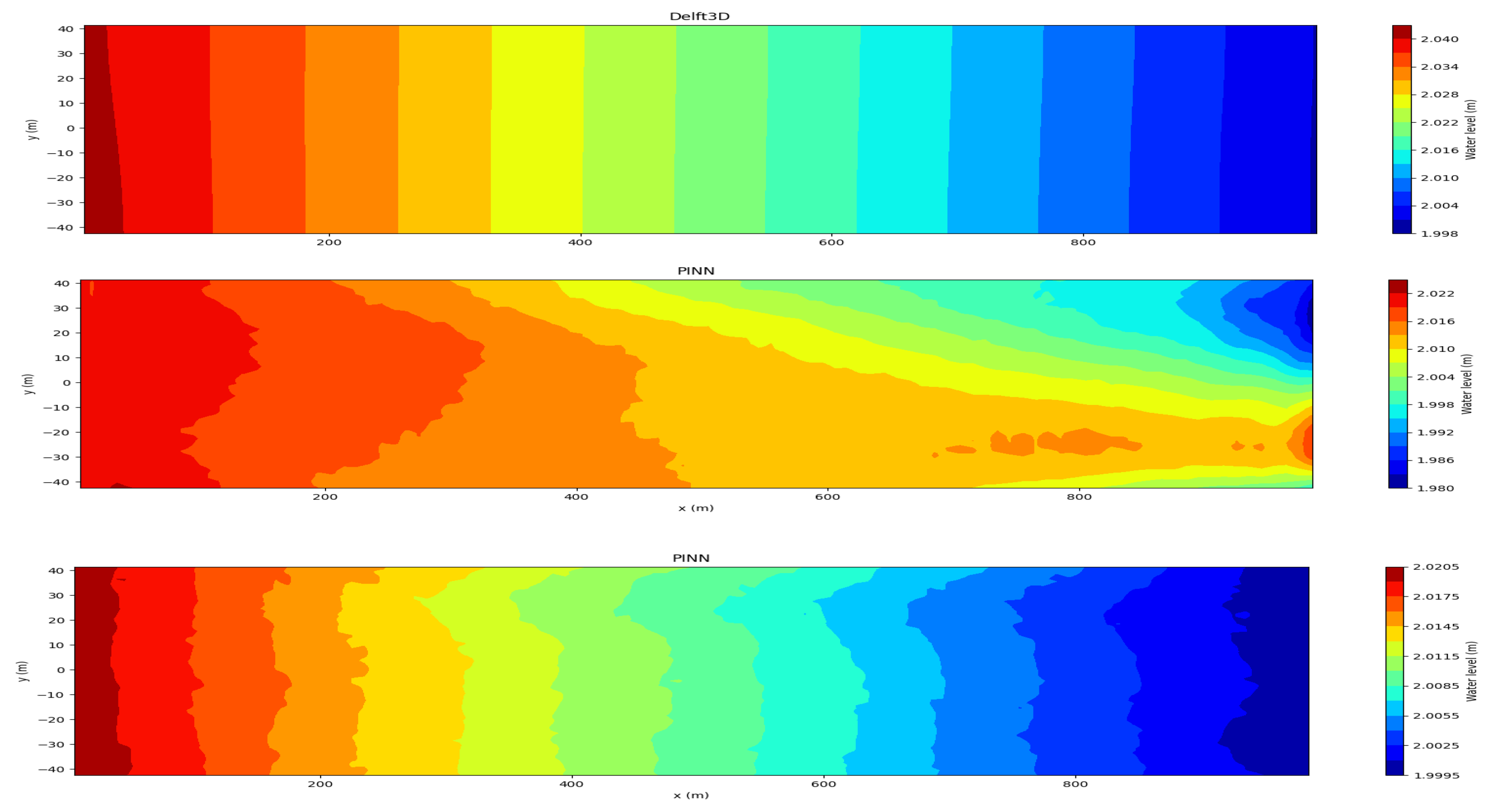

It is also for the first time we solved the coefficient inverse problem for the Saint-Venant equations using PINNs in 2D case. The synthetic data was obtained in the Delft3D computational code for steady problem in a long channel. Using PINNs the velocity and water level fields were obtained. The prediction error of the roughness coefficient n value in 2D case did not exceed 10%.

The most important advantage of using PINN to study hydrological processes is the small computational time for prediction. PINNs may be in demand in digital twin models that need to perform real-time computations.

Another advantage of using PINN is the ability to explore different scenarios while varying the boundary conditions to find the roughness coefficient of the river bed.

However, one disadvantage of the first generation of PINNs is that they usually have limited accuracy even with many training points, and also place high computational demands on memory resources on GPU cards.

Further research in terms of improving prediction accuracy can be related to the use of the regularization approach and in particular to the approach based on the gPINN architecture. The future work will explore problems involving more complex river channel geometries.

Another important area of work is the use of PINNs for real hydrological scenarios, which, however, will require significant efforts to improve the architecture of neural networks. We have to draw our attention to the task of selecting input features. In particular, incorporating river channel geometry is essential.

Figure 1.

The structure of a FCNN for 2D case. X, Y coordinates of points are features. The velocity components, water level, and roughness coefficient are predicted quantities.

Figure 1.

The structure of a FCNN for 2D case. X, Y coordinates of points are features. The velocity components, water level, and roughness coefficient are predicted quantities.

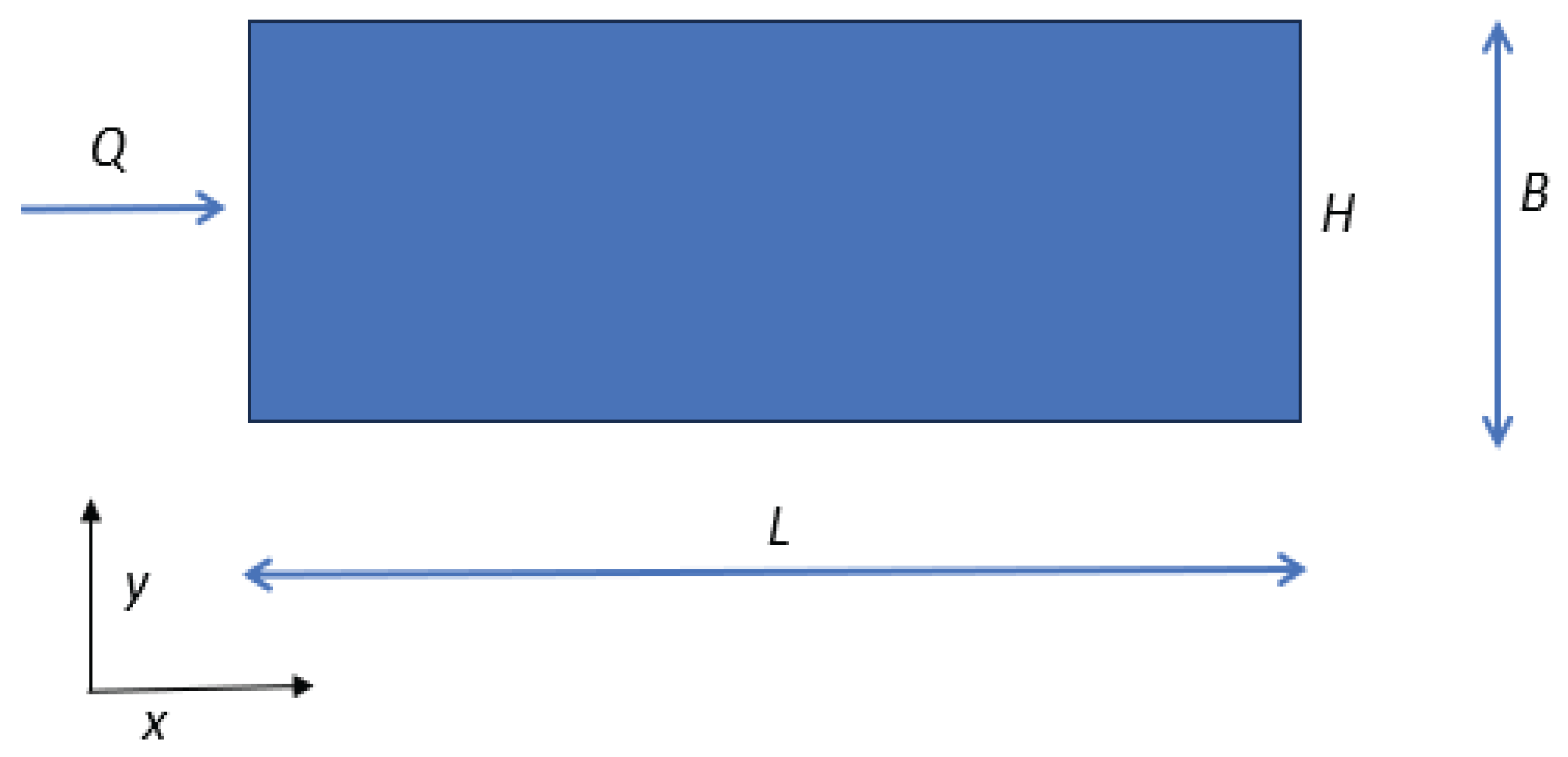

Figure 2.

The computational domain.

Figure 2.

The computational domain.

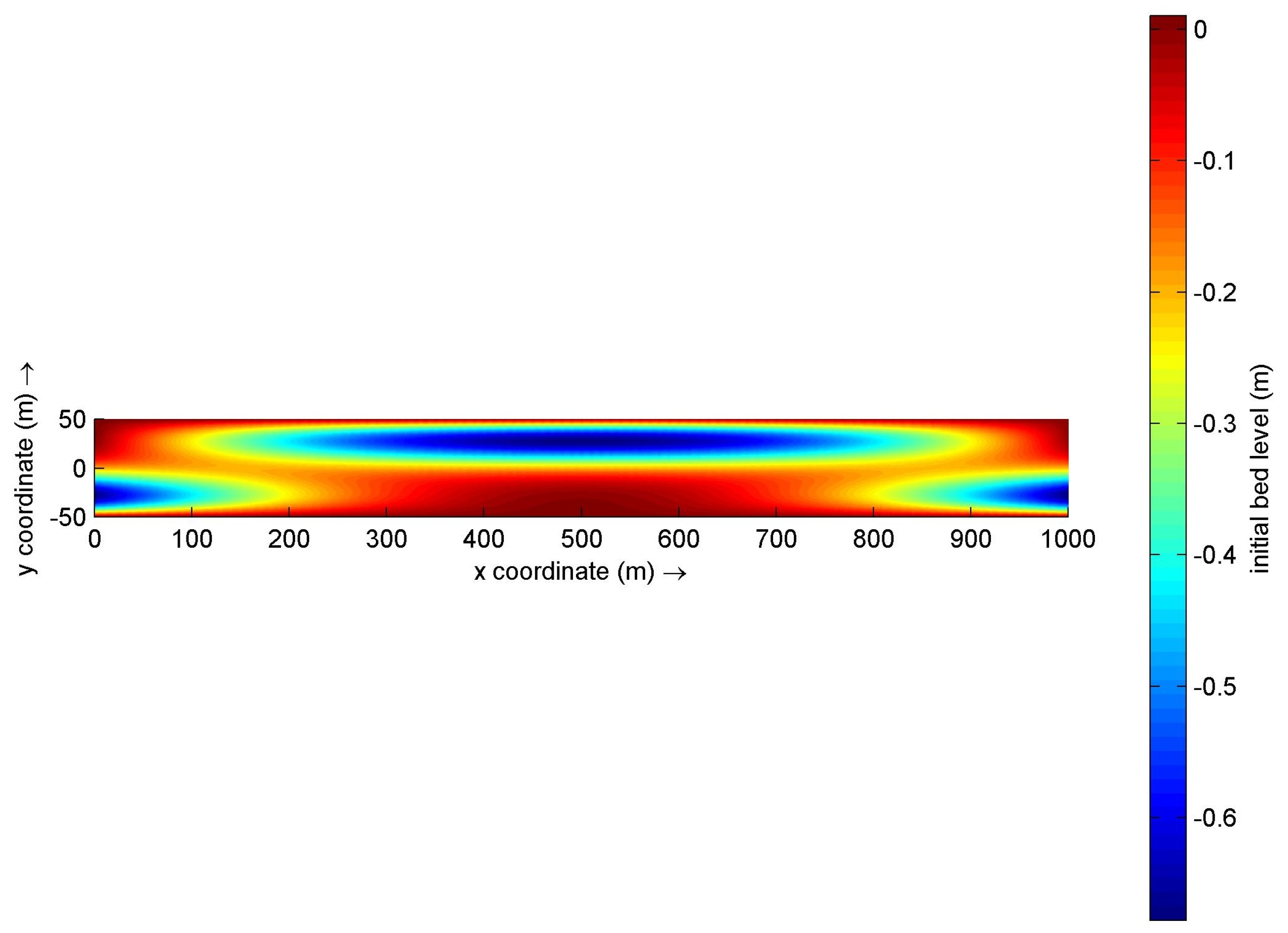

Figure 3.

The Bed surface.

Figure 3.

The Bed surface.

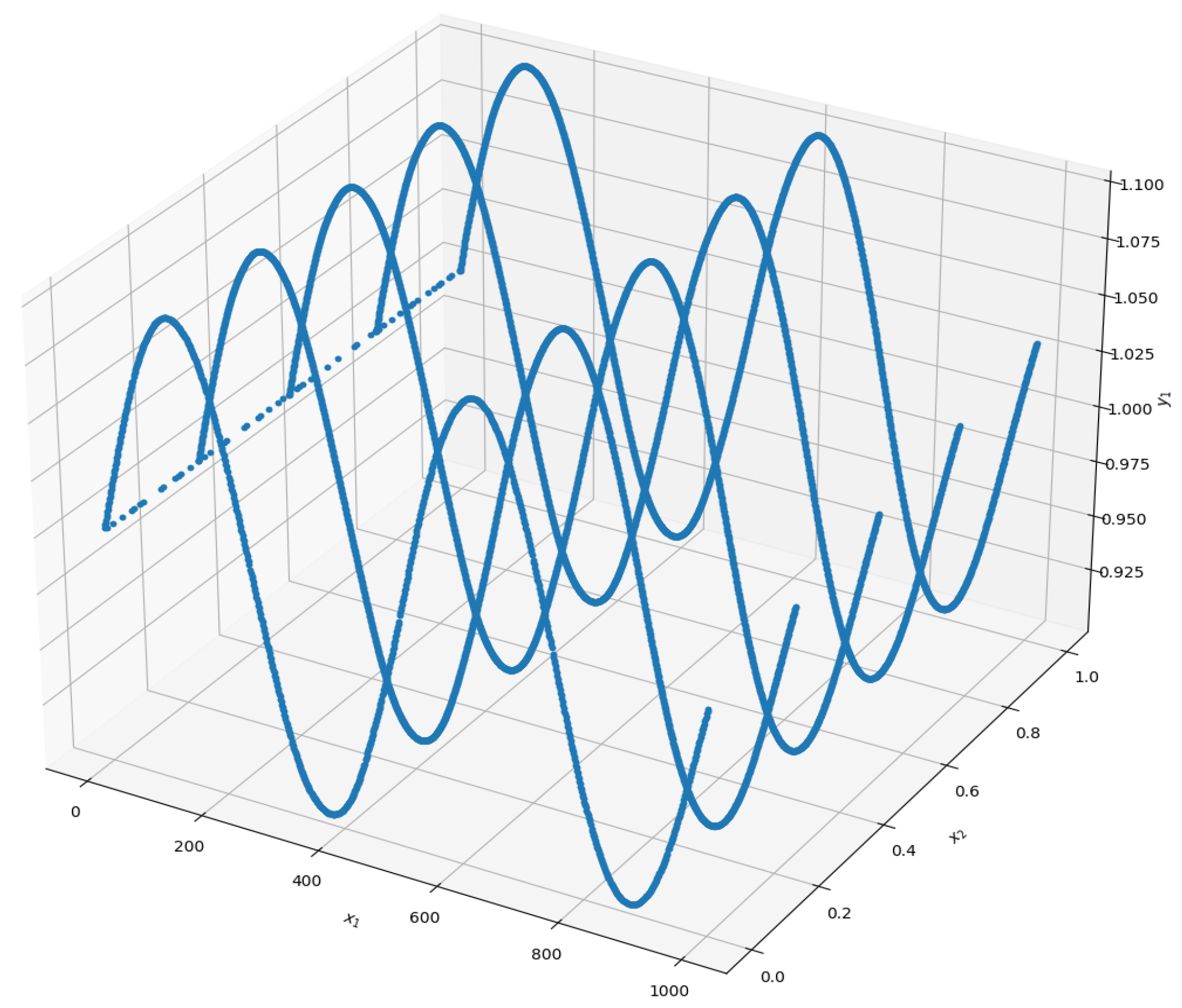

Figure 4.

The area of water section is plotted on the vertical axis. One of the horizontal axes shows the change of x coordinate, the other horizontal axis shows the dimensionless time t. 1D case.

Figure 4.

The area of water section is plotted on the vertical axis. One of the horizontal axes shows the change of x coordinate, the other horizontal axis shows the dimensionless time t. 1D case.

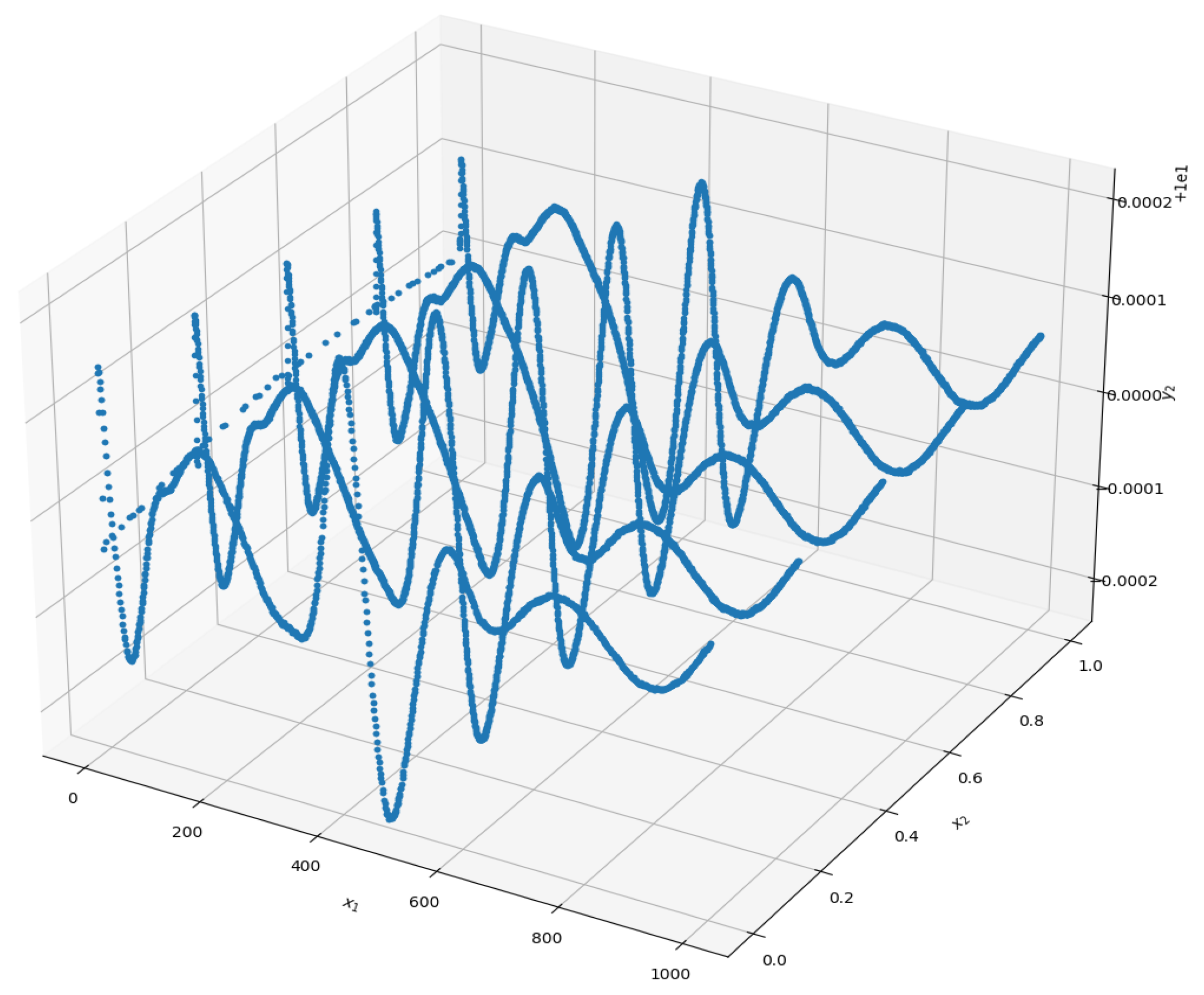

Figure 5.

The water discharge is plotted on the vertical axis. One of the horizontal axes shows the change of x coordinate, the other horizontal axis shows the dimensionless time t. 1D case.

Figure 5.

The water discharge is plotted on the vertical axis. One of the horizontal axes shows the change of x coordinate, the other horizontal axis shows the dimensionless time t. 1D case.

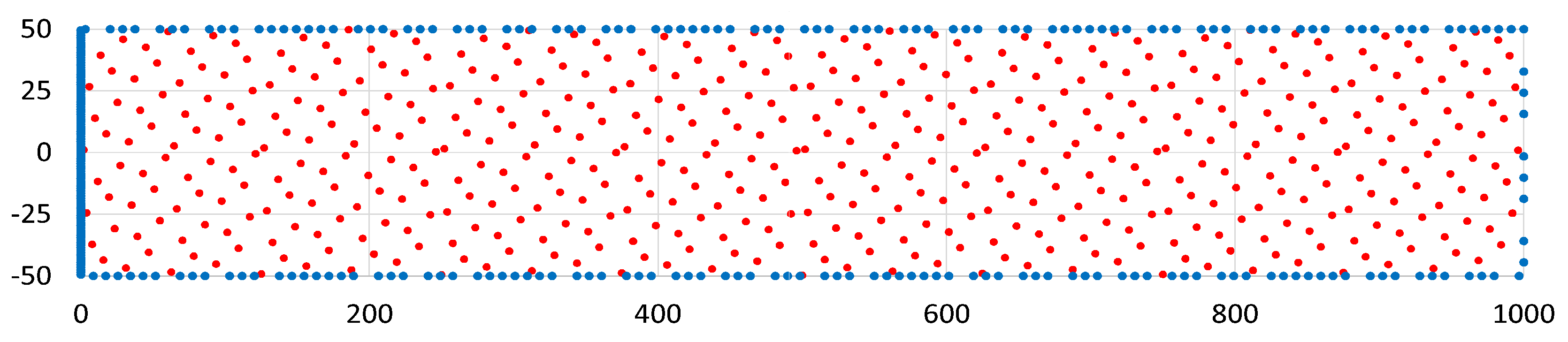

Figure 6.

The number of collocation’s points. 2D case. Grid 1.

Figure 6.

The number of collocation’s points. 2D case. Grid 1.

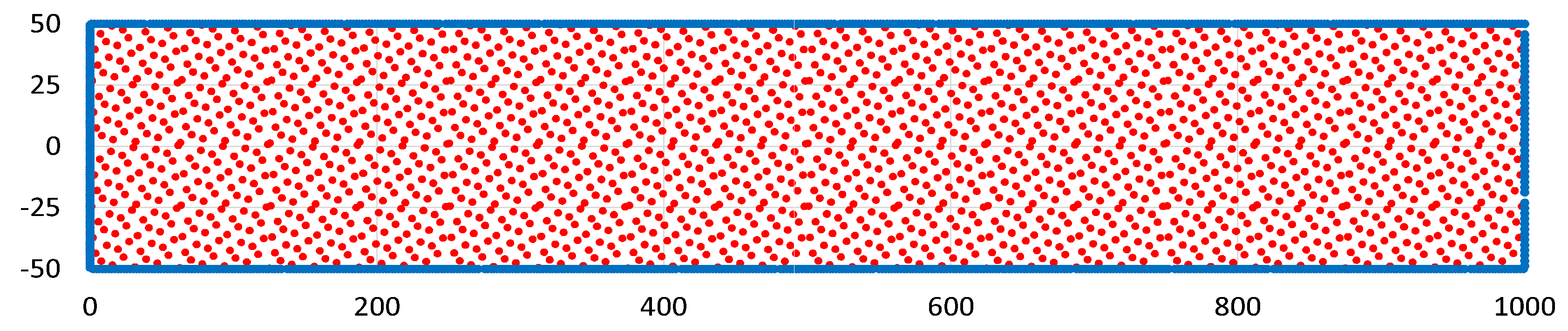

Figure 7.

The number of collocation’s points. 2D case. Grid 2.

Figure 7.

The number of collocation’s points. 2D case. Grid 2.

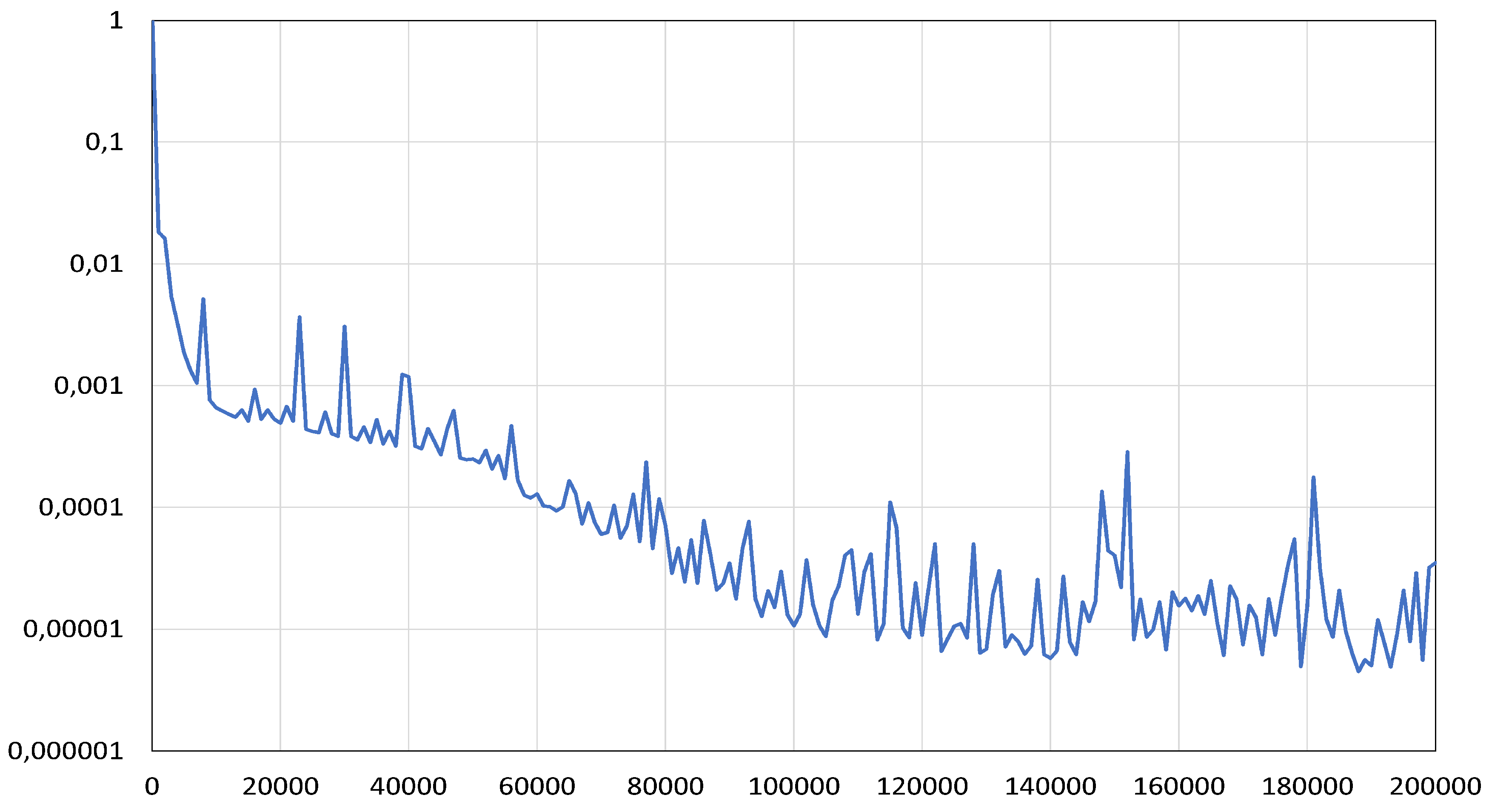

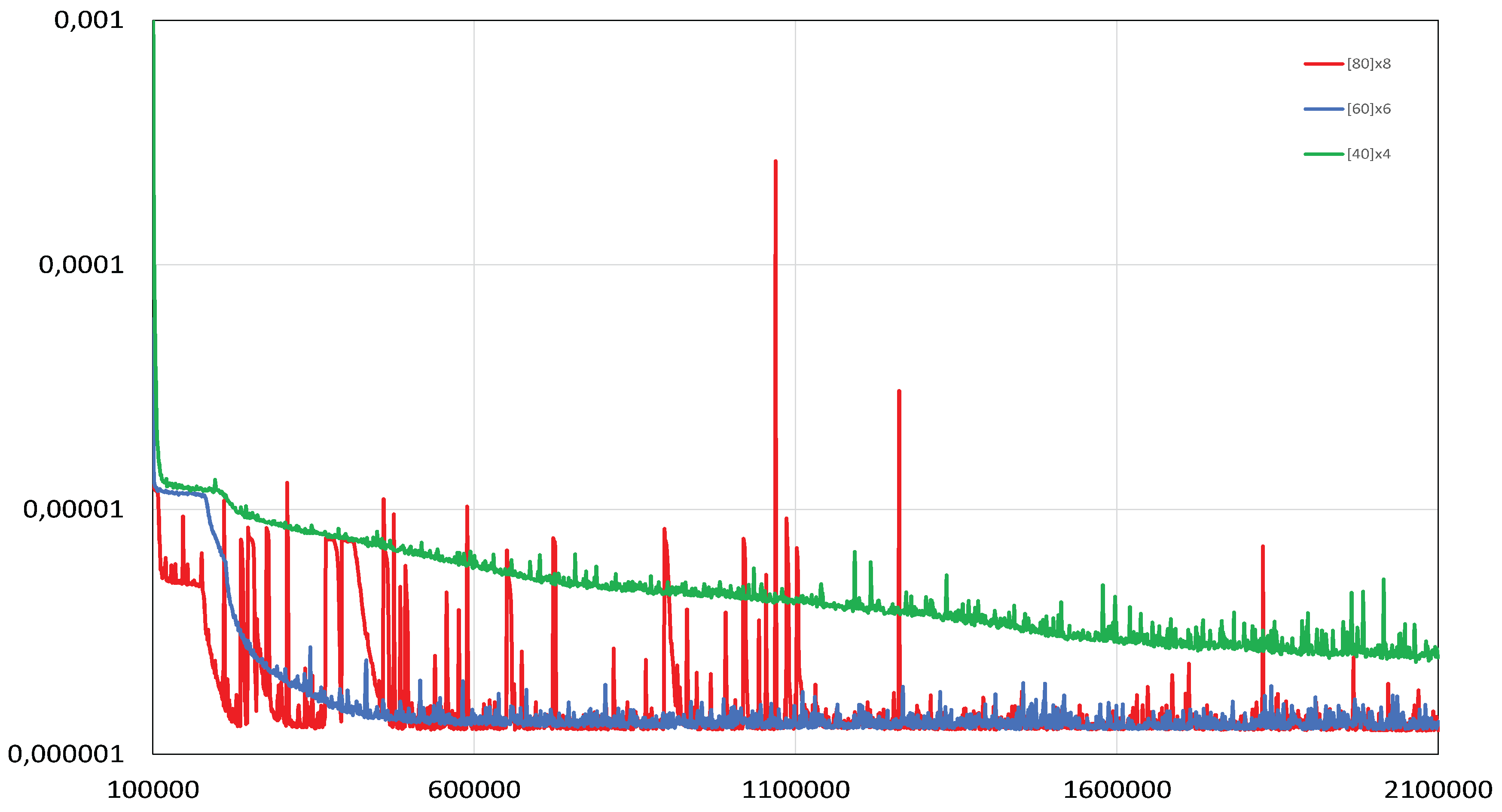

Figure 8.

Evaluation graph of a loss function. The number of iterations is plotted on the horizontal axis. 2D case.

Figure 8.

Evaluation graph of a loss function. The number of iterations is plotted on the horizontal axis. 2D case.

Figure 9.

The water level, calculated using Delft3D code (upper figure), calculated using PINN and constant learning rate lr=0.0001 (middle figure) and calculated using PINN and variable learning rate (lower figure). 2D forward case.

Figure 9.

The water level, calculated using Delft3D code (upper figure), calculated using PINN and constant learning rate lr=0.0001 (middle figure) and calculated using PINN and variable learning rate (lower figure). 2D forward case.

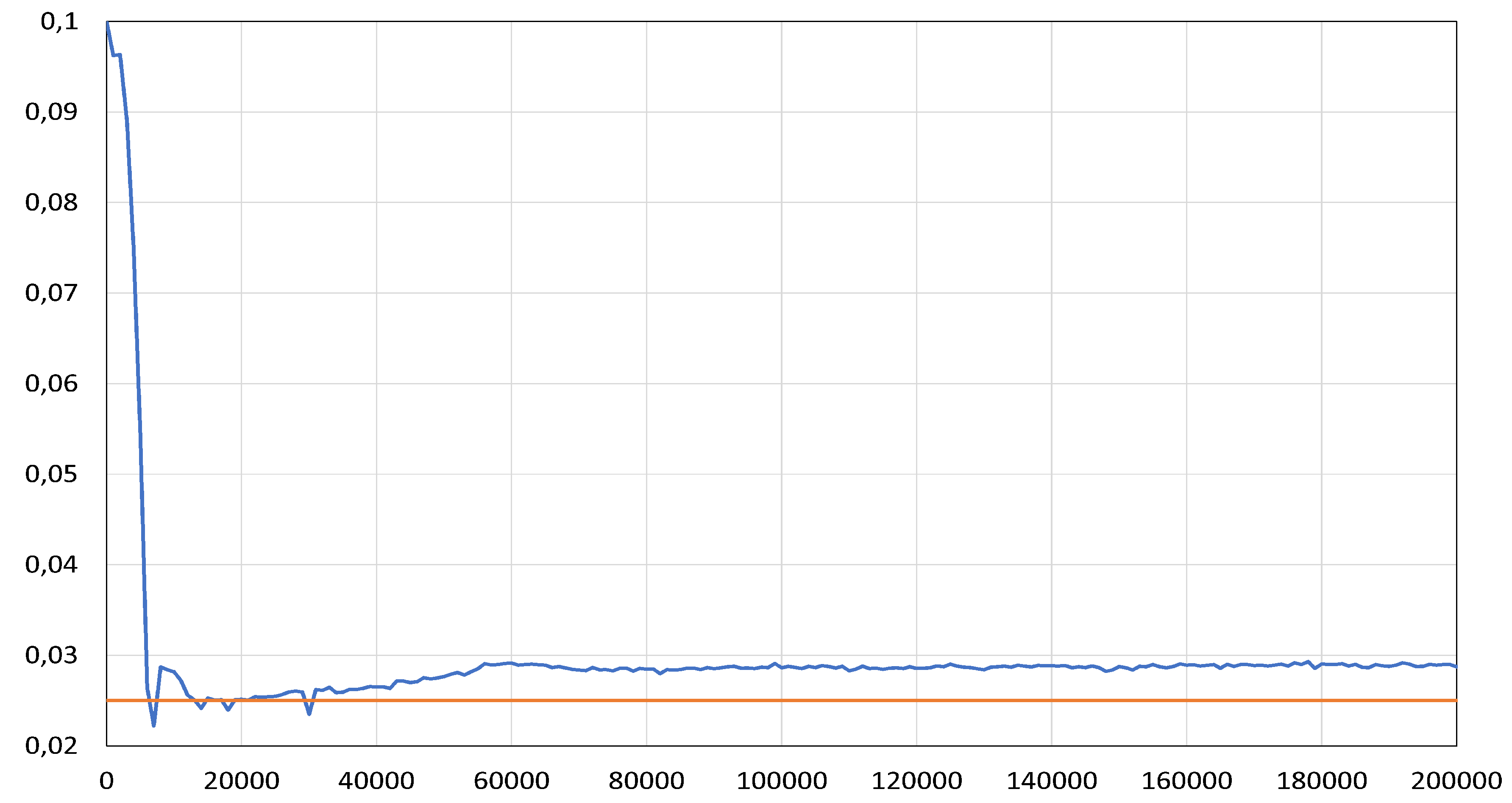

Figure 10.

Evaluation graph of a loss function. The number of iterations is plotted on the horizontal axis. 2D inverse problem. The first variant.

Figure 10.

Evaluation graph of a loss function. The number of iterations is plotted on the horizontal axis. 2D inverse problem. The first variant.

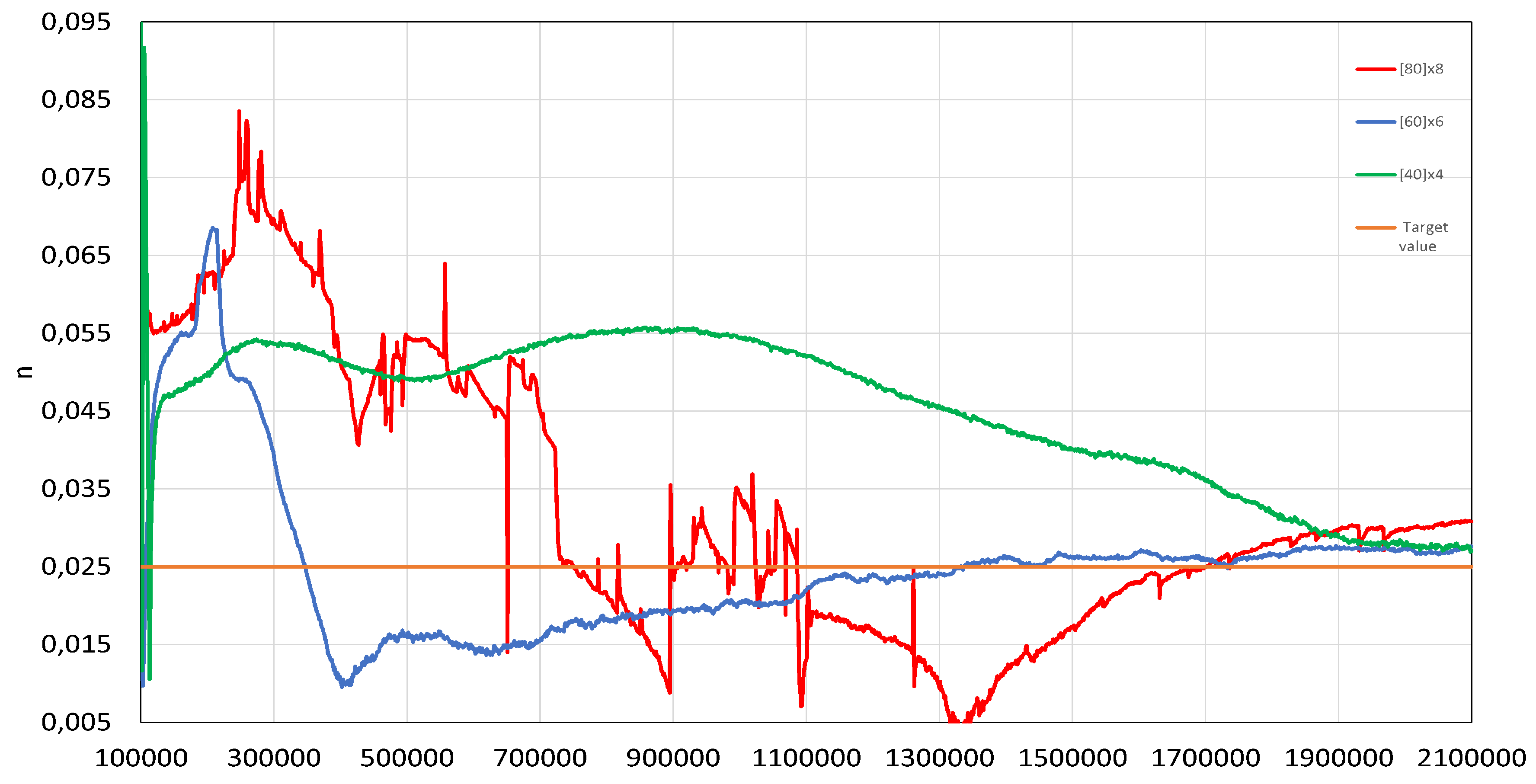

Figure 11.

The roughness coefficient. The orange curve is the exact value of the coefficient. The number of iterations is plotted on the horizontal axis. 2D inverse problem. The first variant.

Figure 11.

The roughness coefficient. The orange curve is the exact value of the coefficient. The number of iterations is plotted on the horizontal axis. 2D inverse problem. The first variant.

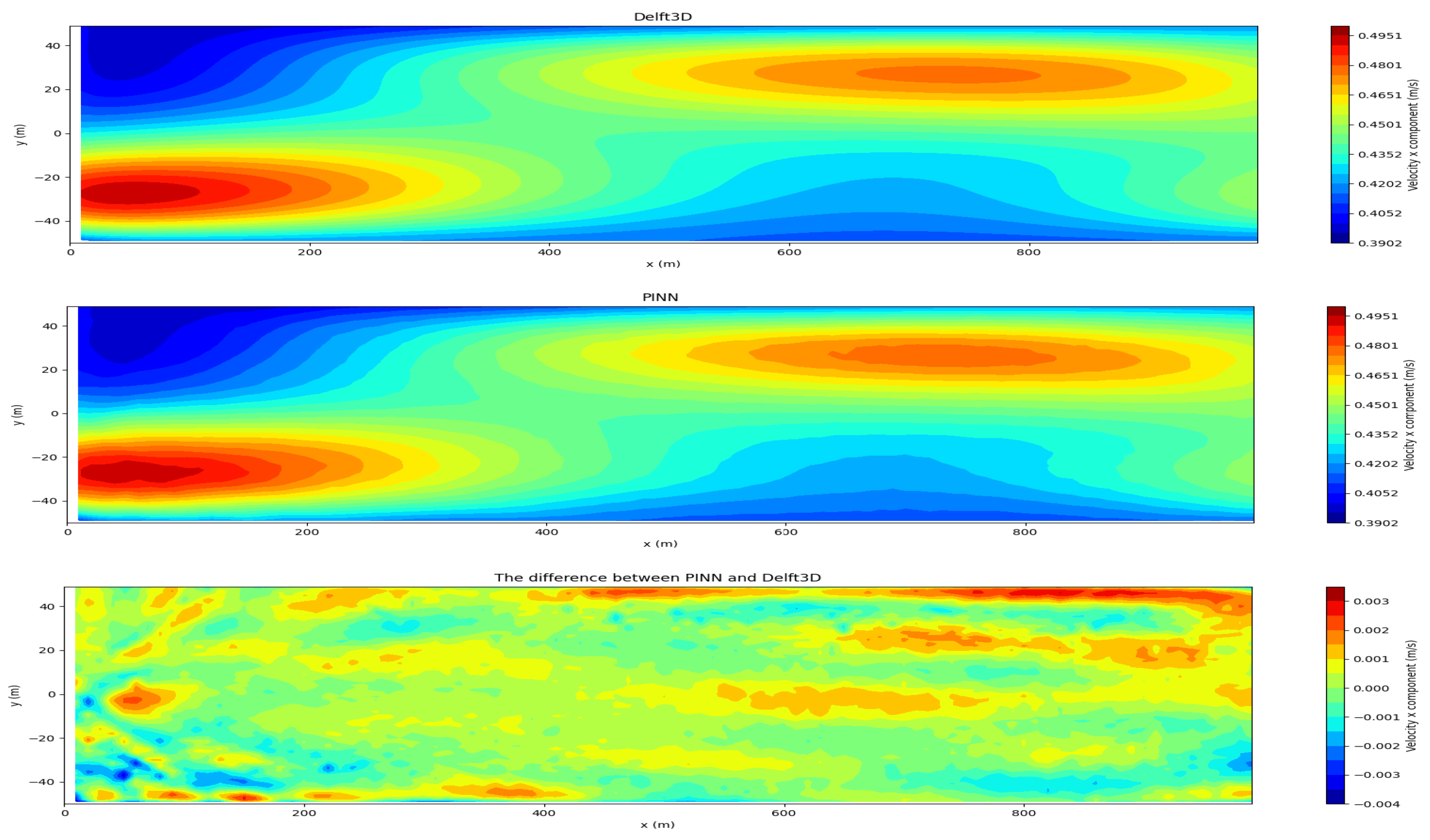

Figure 12.

x component of averaged velocity. 2D inverse problem. The first variant.

Figure 12.

x component of averaged velocity. 2D inverse problem. The first variant.

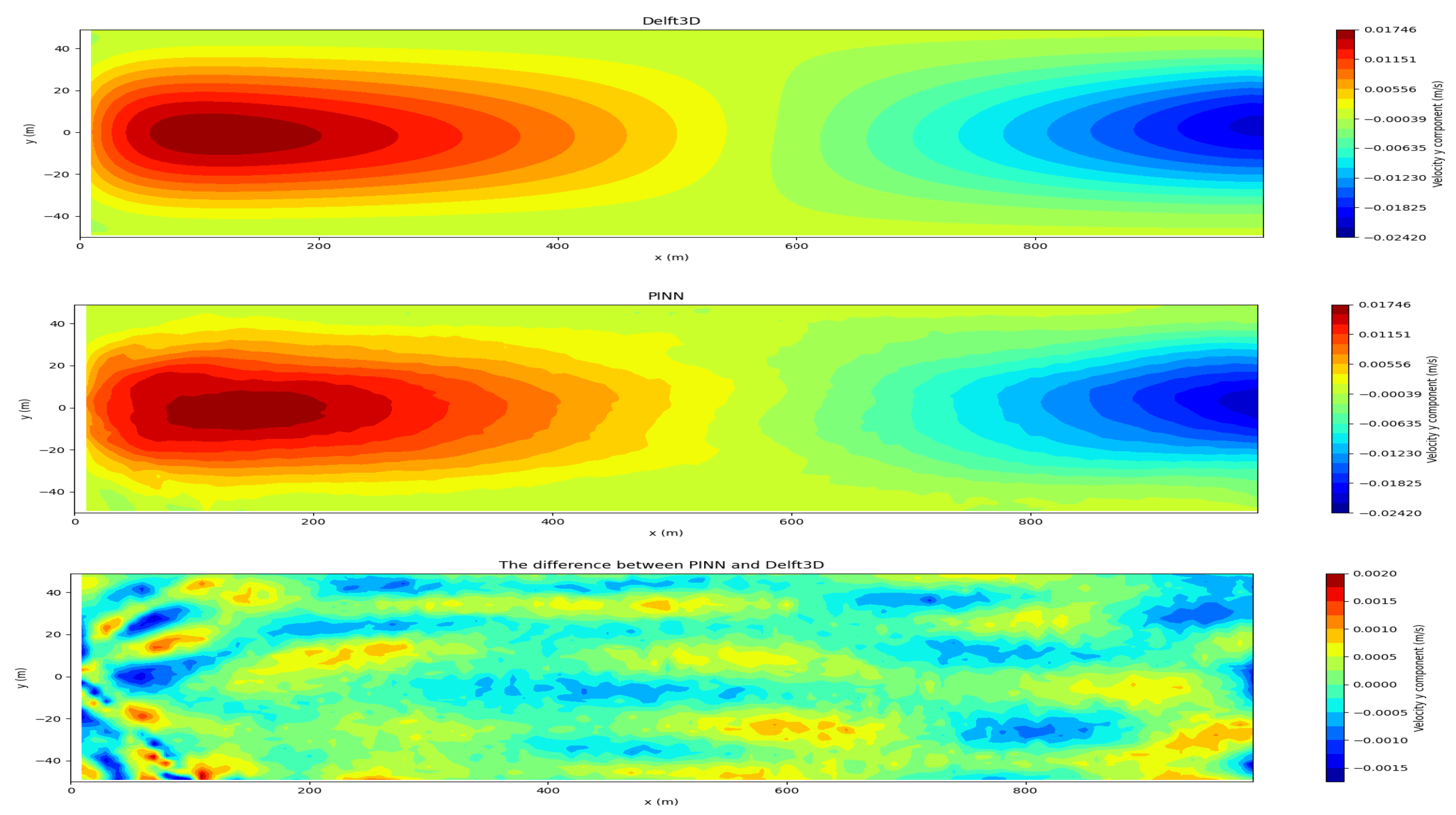

Figure 13.

y component of averaged velocity. 2D inverse problem. The first variant.

Figure 13.

y component of averaged velocity. 2D inverse problem. The first variant.

Figure 14.

Evaluation graph of a loss function. The number of iterations is plotted on the horizontal axis. The second variant of inverse problem.

Figure 14.

Evaluation graph of a loss function. The number of iterations is plotted on the horizontal axis. The second variant of inverse problem.

Figure 15.

The roughness coefficient. The orange curve is the exact value of the coefficient. The number of iterations is plotted on the horizontal axis. The second variant of inverse problem.

Figure 15.

The roughness coefficient. The orange curve is the exact value of the coefficient. The number of iterations is plotted on the horizontal axis. The second variant of inverse problem.

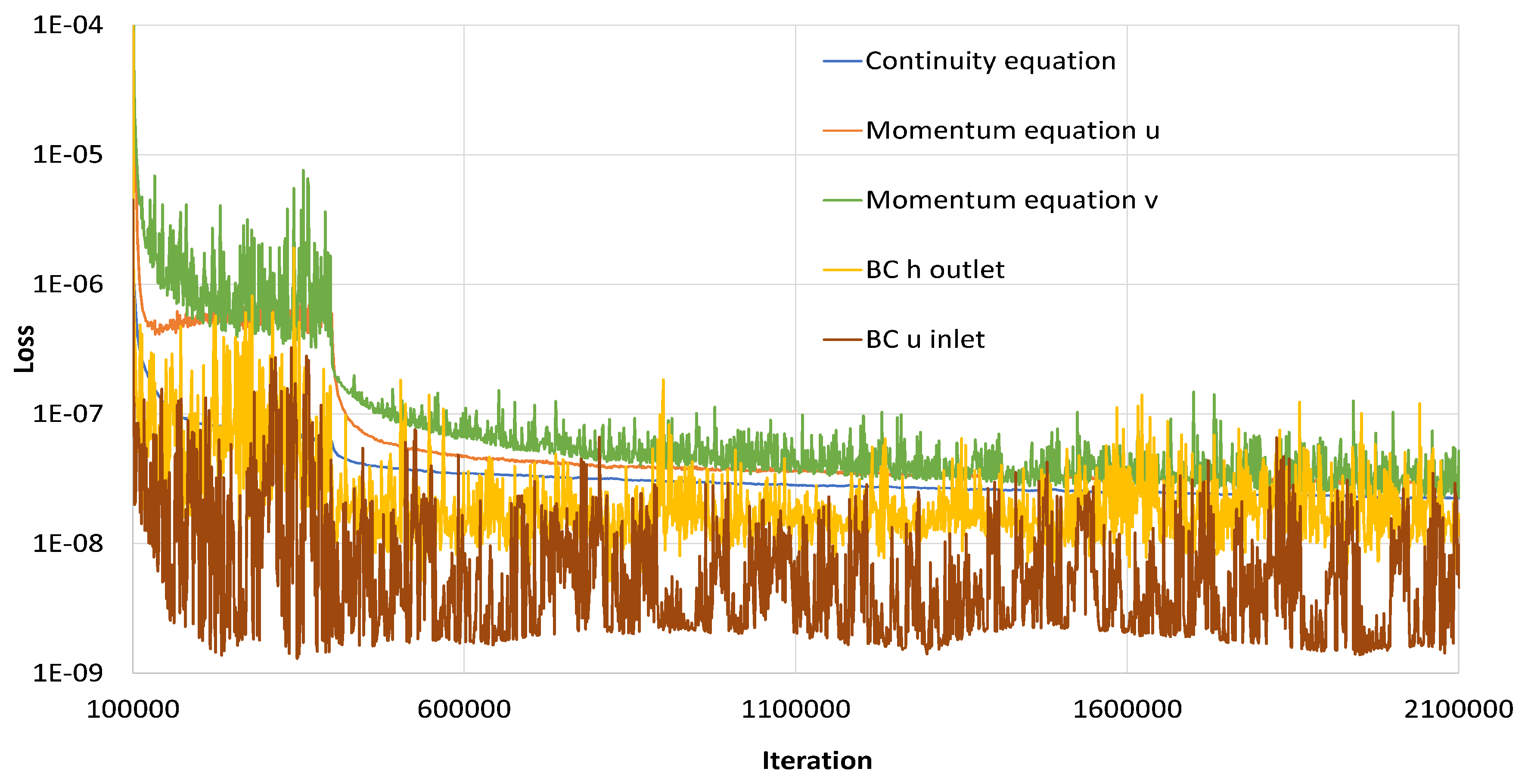

Figure 16.

Graphs of different values of loss function components for 2D inverse problem.

Figure 16.

Graphs of different values of loss function components for 2D inverse problem.

| Number |

Value |

Description |

| 1 |

0.022 |

Earth channel - clean |

| 2 |

0.025 |

Earth channel - gravelly |

| 3 |

0.030 |

Earth channel - weedy |

| 4 |

0.035 |

Earth channel - stony, cobbles |

| 5 |

0.035 |

Floodplains - pasture, farmland |

| 6 |

0.050 |

Floodplains - light brush |

| 7 |

0.075 |

Floodplains - heavy brush |

| 8 |

0.15 |

Floodplains - trees 1

|

Table 2.

The main hyperparameters

Table 2.

The main hyperparameters

| Number of layers |

Number of neurons |

Name of test |

| 4 |

40 |

test 1 - model 1 |

| 6 |

60 |

test 2 - model 2 |

| 8 |

80 |

test 3 - model 3 |

Table 3.

The main approaches and parameters

Table 3.

The main approaches and parameters

| Equations |

Problem |

Reference solution, Anchors |

| 1D |

forward |

Analytical |

| 1D |

inverse |

Analytical, Random points |

| 2D |

forward |

Delft3D |

| 2D variant 1 |

inverse |

Delft3D, Delft3D mesh |

| 2D variant 2 |

inverse |

Delft3D, Inlet |

Table 4.

The number of points for grid

Table 4.

The number of points for grid

| Grid |

Points inner area |

Points for borders |

| 1 |

500 |

200 |

| 2 |

2000 |

1000 |

Table 5.

Selection of value for Learning rate.

Table 5.

Selection of value for Learning rate.

| Iterations |

Learning rate |

| 0-100000 |

0.001 |

| 100000-300000 |

0.0003 |

| 300000-700000 |

0.0001 |

| 700000-1500000 |

0.00003 |

| 1500000-2500000 |

0.00001 |

Table 6.

Selection of points and Learning time

Table 6.

Selection of points and Learning time

| Points |

Learning time, hours |

| 500 |

1 |

| 2000 |

1 |

| 5000 |

1.3 |

| 20000 |

3 |

| 50000 |

6 |