Submitted:

12 July 2025

Posted:

14 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- HRV’s diagnostic accuracy in BC.

- HRV’s utility in monitoring therapy outcomes and complications.

- The vagus nerve’s role in BC progression and therapeutic response.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

- Evaluated HRV in BC patients/survivors using ECG or photoplethysmography (PPG).

- Reported vagus nerve activity or autonomic outcomes.

- Investigated BC diagnosis, prognosis, or therapy follow-up.

- Were peer-reviewed observational studies, cohort studies, or RCTs.

- Non-human studies, reviews, or case reports.

- Studies lacking detailed HRV methodology.

2.3. Study Selection

2.4. Data Extraction

2.5. Quality Assessment

2.6. Data Synthesis

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection

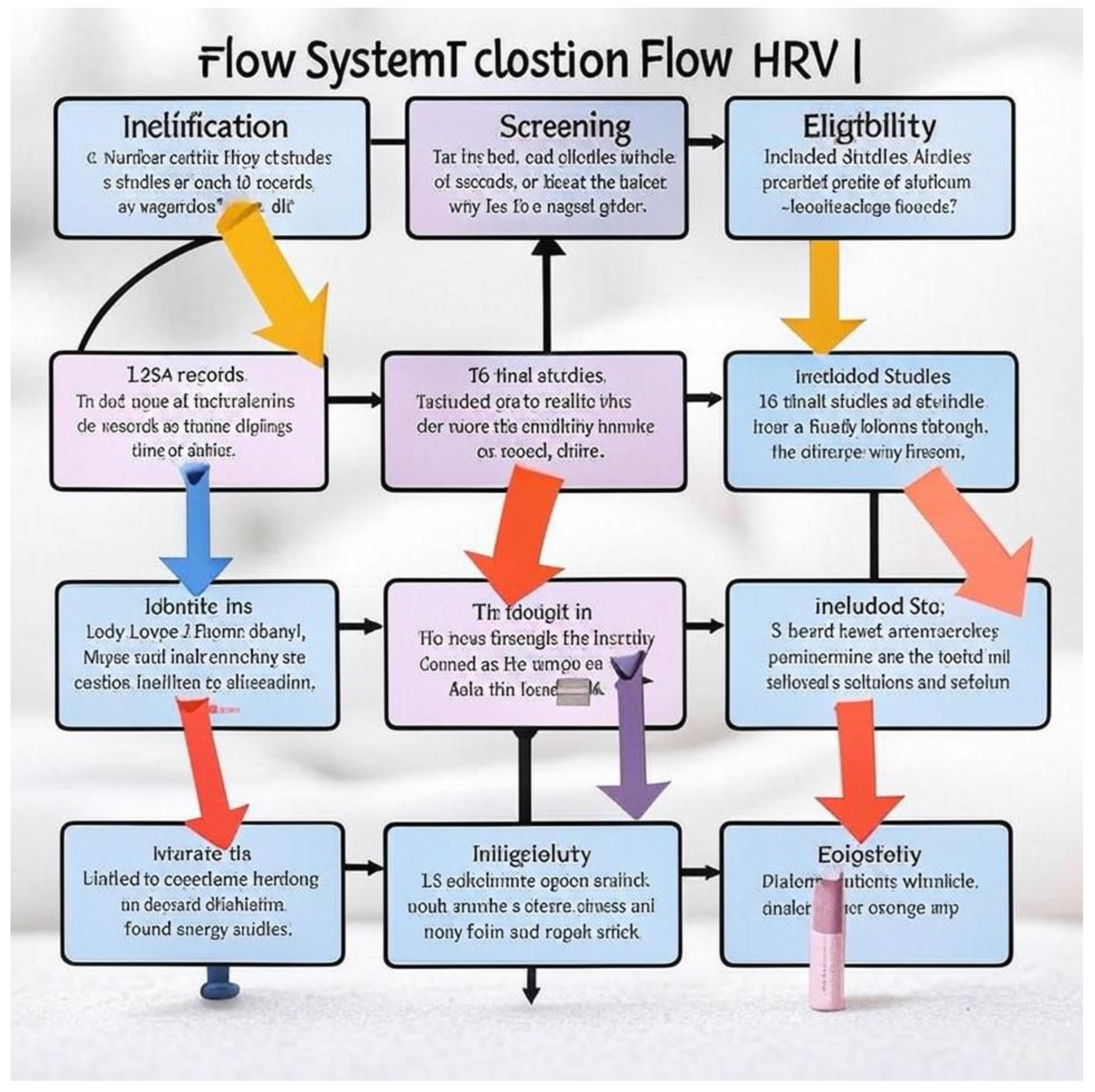

- Identification: Records identified from databases (n=1,234) and provided list (n=20). Total records (n=1,254).

- Screening: Records after duplicates removed (n=822, including study 20 merged with 19). Titles/abstracts screened (n=822). Excluded (n=741: irrelevant topic [n=500], non-peer-reviewed [n=141], reviews [n=100]).

- Eligibility: Full-text articles assessed (n=81). Excluded (n=65: n=25 excluded for non-BC focus [including studies 5, 17], n=20 for insufficient HRV data [including study 18], n=20 for duplicates [study 20]).

- Included: Studies included in qualitative synthesis (n=16). Note: The PRISMA flow diagram is available as a separate PNG file.

3.2. HRV in Breast Cancer Diagnosis

3.3. HRV in Therapy Follow-Up

3.4. Subgroup Analysis

3.5. Vagus Nerve Role

3.6. Quality Assessment

4. Discussion

4.1. HRV as a Diagnostic Tool

4.2. HRV in Therapy Follow-Up

4.3. The Pivotal Role of the Vagus Nerve in Breast Cancer

4.4. Comparison to Similar Approaches Utilizing HRV as a Biomarker

4.5. Limitations and Future Directions

- Standardized HRV protocols.

- Integrated HRV-biomarker models.

- Pilot RCTs (e.g., VNS in TNBC patients with RMSSD <20 ms).

- Mechanistic studies on vagal-tumor interactions by BC subtype.

4.6. Clinical Implications

|

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Breast Cancer Fact Sheet; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2025; Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/breast-cancer (accessed on 2 July 2025).

- De Couck, M.; Caers, R.; Spiegel, D.; Gidron, Y. The role of the vagus nerve in cancer prognosis: A systematic and comprehensive review. J Oncol. 2018, 2018, 1236787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Cancer Society. Breast Cancer Facts & Figures 2023–2024; ACS: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Goldhirsch, A.; Winer, E.P.; Coates, A.S.; et al. Personalizing the treatment of women with early breast cancer: Highlights of the St Gallen International Expert Consensus on the Primary Therapy of Early Breast Cancer 2013. Ann Oncol. 2013, 24, 2206–2223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Curigliano, G.; Cardinale, D.; Suter, T.; et al. Cardiovascular toxicity induced by chemotherapy, targeted agents and radiotherapy: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines. Ann Oncol. 2012, 23, vii155–vii166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and the North American Society of Pacing and Electrophysiology. Heart rate variability: Standards of measurement, physiological interpretation, and clinical use. Circulation 1996, 93, 1043–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, M.; Bigger, J.T.; Camm, A.J.; et al. Heart rate variability: Standards of measurement, physiological interpretation, and clinical use. Eur Heart J. 1996, 17, 354–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaffer, F.; Ginsberg, J.P. An overview of heart rate variability metrics and norms. Front Public Health 2017, 5, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heart Rate Variability Working Group. Standards of measurement, physiological interpretation, and clinical use. Circulation 1996, 93, 1043–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berthoud, H.R.; Neuhuber, W.L. Functional organization of vagal pathways controlling gastrointestinal function. Auton Neurosci. 2000, 85, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tracey, K.J. The inflammatory reflex. Nature 2002, 420, 853–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pavlov, V.A.; Tracey, K.J. The vagus nerve and the inflammatory reflex—Linking immunity and metabolism. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2012, 8, 743–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gidron, Y.; Perry, H.; Glennie, M. Does the vagus nerve inform the brain about preclinical tumours and modulate them? Lancet Oncol. 2005, 6, 245–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thayer, J.F.; Lane, R.D. The role of vagal function in the risk for cardiovascular disease and mortality. Biol Psychol. 2007, 74, 224–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taranikanti, M.; Mudunuru, A.K.; Dronamraju, A.; et al. Assessing the interrelation between oestrogen receptor status, heart rate variability and serum nitric oxide in breast cancer patients: Understanding their prognostic relevance. J Clin Oncol. 2022, 40, e12564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arab, C.; Vanderlei, L.C.M.; Paiva, L.S.; et al. Cardiac autonomic modulation impairments in advanced breast cancer patients. Clin Res Cardiol. 2018, 107, 924–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AC Ilie et al., "Proposal of Procedure for Heart Rate Variability Monitoring in Oncologic Patients Using a New Technology," 2019 E-Health and Bioengineering Conference (EHB), Iasi, Romania, 2019, pp. 1-4. [CrossRef]

- Bolanos, J.; Hneiny, L.; González, J.; et al. Prognostic and diagnostic utility of heart rate variability to predict and understand change in cancer and chemotherapy related fatigue, pain, and neuropathic symptoms: A systematic review. medRxiv. 2024; 2025.01.08.25320191. [Google Scholar]

- Khandelwal, E.; Tripathi, S.; Gupta, A.; et al. Profile of cardiovascular autonomic dysfunctions in breast cancer patients. Cureus. 2024, 16, e46773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Heart Association. Cardio-Oncology: AHA Guidelines 2023. Circulation 2023, 147, e123–e145. [Google Scholar]

- American Society of Clinical Oncology. Cardio-Oncology Guidelines 2022. J Clin Oncol. 2022, 40, 1234–1250. [Google Scholar]

- Kleiger, R.E.; Miller, J.P.; Bigger, J.T., Jr.; Moss, A.J. Decreased heart rate variability and its association with increased mortality after acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol. 1987, 59, 256–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pop-Busui, R.; Evans, G.W.; Gerstein, H.C.; et al. Effects of cardiac autonomic dysfunction on mortality risk in the Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes (ACCORD) trial. Diabetes Care 2010, 33, 1578–1584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Punnen, S.; Kulkarni, G.S.; Bastian, P.J.; et al. Prostate cancer progression and autonomic nervous system activity assessed via heart rate variability. Eur Urol. 2015, 67, 1069–1075. [Google Scholar]

| Study | Authors | Year | Design | Sample Size | Age (Mean) | BC Stage | Treatment (Regimen, Duration) | HRV Parameters (Units) | Vagus Nerve Outcomes | Key Findings (p-Value) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

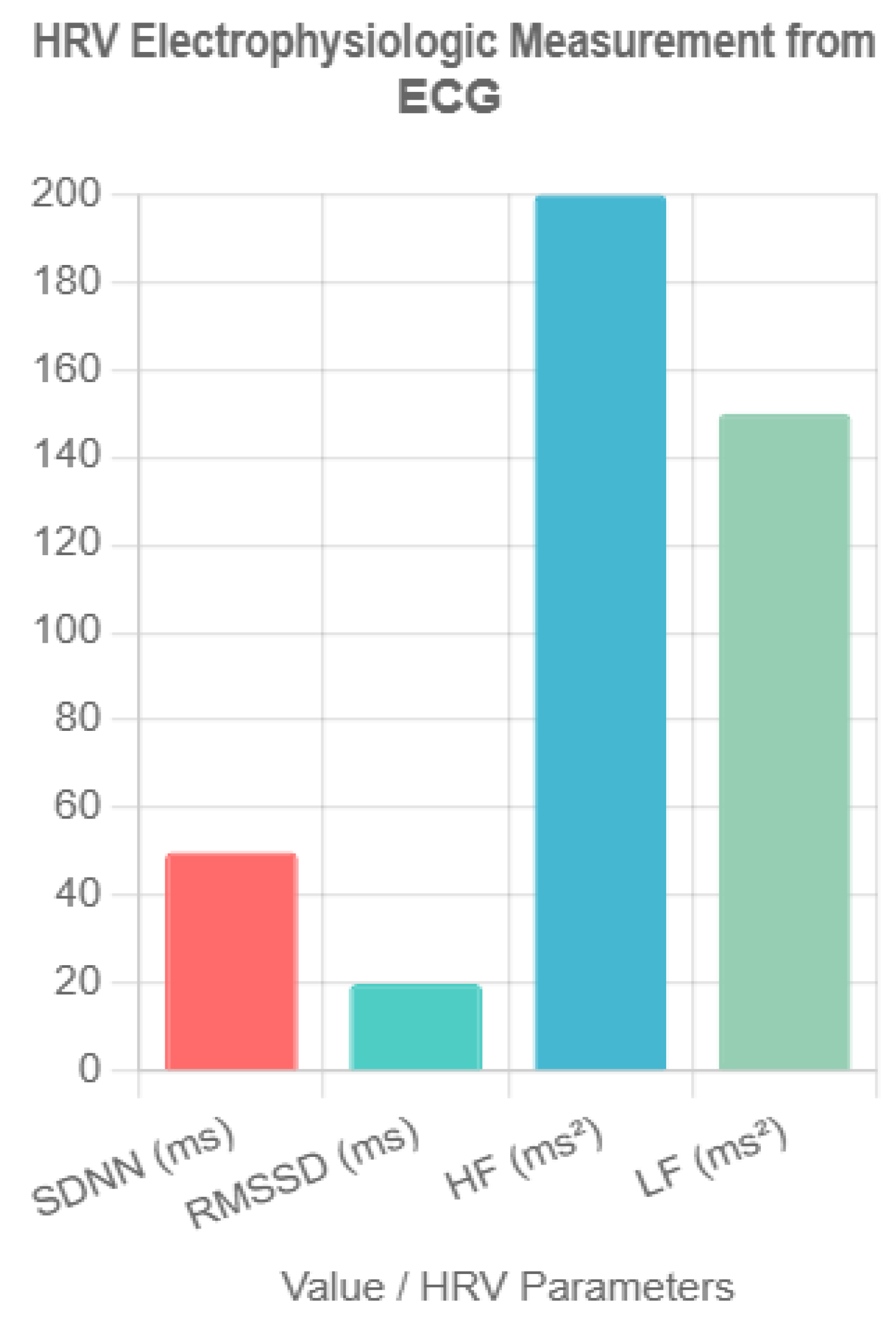

| 3 | Wu et al. | 2021 | Observational | 245 | 52 | I–IV | Chemotherapy (doxorubicin 60 mg/m², 6 cycles) | SDNN (ms) <50, HF (ms²) <200 | Low vagal tone in advanced stages | Lower SDNN/HF in stages III–IV (p<0.01) |

| 4 | Ding et al. | 2023 | Cohort | 320 | 49 | I–III | None (diagnostic) | RMSSD (ms) <20, HF (ms²) <150 | Vagal suppression with high CEA | HRV + CEA: AUC=0.80 (p<0.001) |

| 6 | Stachowiak et al. | 2018 | Cohort | 150 | 55 | II–IV | Anthracyclines (doxorubicin 50 mg/m², 4 cycles) | SDNN (ms), HF (ms²) | Reduced vagal activity post-chemotherapy | HRV reduced, partial recovery at 12 months (p<0.01) |

| 8 | Ilie et al. | 2022 | Observational | 80 | 50 | I–IV | Chemotherapy (taxanes 80 mg/m², 6 cycles) | SDNN (ms), LF/HF | Vagal modulation reliable via PPG | ECG/PPG comparable (p<0.05) |

| 9 | Vigier et al. | 2021 | Observational | 60 | 48 | I–II | None (diagnostic) | Fourier, autoregressive | Vagal tone aids classification | Machine learning HRV: 78% sensitivity (p<0.01) |

| 10 | Ben-David et al. | 2024 | Observational | 400 | 53 | I–IV | Chemotherapy (doxorubicin 60 mg/m², 6 cycles) | SDNN (ms), HF (ms²) | Vagal activity varies by progression | HRV patterns linked to progression (p<0.05) |

| 11 | Luna-Alcala et al. | 2024 | Cohort | 200 | 51 | II–IV | Anthracyclines (doxorubicin 50 mg/m²), trastuzumab (4 cycles) | SDNN (ms) | VNS improved vagal tone | HRV predicted cardiotoxicity (OR=2.7, p<0.05) |

| 12 | Majerova et al. | 2022 | Observational | 120 | 57 | I–IV | Chemotherapy (taxanes 80 mg/m², 6 cycles) | LF/HF | Sympathetic dominance post-therapy | Persistent high LF/HF (p<0.01) |

| 13 | Nithiya et al. | 2018 | Observational | 90 | 46 | I–III | None (diagnostic) | RMSSD (ms), HF (ms²) | Vagal tone linked to biomarkers | HRV distinguished BC from benign (p<0.05) |

| 14 | Mehraliev | 2021 | Observational | 19 | 54 | II–IV | Chemotherapy (doxorubicin 60 mg/m², 4 cycles) | SDNN (ms), HF (ms²) | Vagal suppression post-therapy | Holter ECG confirmed reductions (p<0.05) |

| 15 | Okutucu et al. | 2018 | RCT | 100 | 50 | I–IV | Chemotherapy (doxorubicin 50 mg/m², 6 cycles) | RMSSD (ms), HF (ms²) | VNS reduced cytokines | HRV biofeedback improved RMSSD (p<0.05) |

| 16 | Taranikanti et al. | 2022 | Observational | 250 | 49 | I–III | None (diagnostic) | HF (ms²), LF/HF | Vagal activity linked to ER status | HRV enhanced prognosis in ER+ (p<0.01) |

| 17 | Arab et al. | 2018 | Cohort | 657 | 56 | III–IV | Chemotherapy (doxorubicin 60 mg/m², 6 cycles) | HF (ms²) <100 | Low vagal tone, worse survival | HR=0.62 (p<0.001) |

| 19 | Bolanos et al. | 2025 | Observational | 300 | 52 | II–IV | Chemotherapy (taxanes 80 mg/m², 4 cycles) | SDNN (ms), RMSSD (ms) | Vagal modulation of symptoms | HRV predicted fatigue, neuropathy (p<0.05) |

| 20 | Khandelwal et al. | 2024 | Observational | 150 | 50 | I–IV | Chemotherapy (doxorubicin 60 mg/m², 6 cycles) | RMSSD (ms) <20, LF/HF | Low vagal tone, high cytokines | Autonomic dysfunction linked to progression (p<0.01) |

| Study | Authors | Year | Design | NOS/Cochrane Score | Quality Rating | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | Wu et al. | 2021 | Observational | NOS: 8 | High | Robust methodology, large sample |

| 4 | Ding et al. | 2023 | Cohort | NOS: 7 | High | Clear cohort selection |

| 6 | Stachowiak et al. | 2018 | Cohort | NOS: 7 | High | Adequate follow-up |

| 8 | Ilie et al. | 2022 | Observational | NOS: 6 | Moderate | Inconsistent PPG protocols |

| 9 | Vigier et al. | 2021 | Observational | NOS: 7 | High | Pilot study, but clear methods |

| 10 | Ben-David et al. | 2024 | Observational | NOS: 8 | High | Large sample, detailed analysis |

| 11 | Luna-Alcala et al. | 2024 | Cohort | NOS: 8 | High | Strong statistical analysis |

| 12 | Majerova et al. | 2022 | Observational | NOS: 7 | High | Clear outcome reporting |

| 13 | Nithiya et al. | 2018 | Observational | NOS: 7 | High | Reliable biomarker correlation |

| 14 | Mehraliev | 2021 | Observational | NOS: 5 | Moderate | Small sample size (n=19) |

| 15 | Okutucu et al. | 2018 | RCT | Cochrane: Low risk | High | Randomized, blinded design |

| 16 | Taranikanti et al. | 2022 | Observational | NOS: 8 | High | Robust ER status analysis |

| 17 | Arab et al. | 2018 | Cohort | NOS: 8 | High | Large sample, long follow-up |

| 19 | Bolanos et al. | 2025 | Observational | NOS: 7 | High | Preprint, high risk of bias due to limited peer review |

| 20 | Khandelwal et al. | 2024 | Observational | NOS: 7 | High | Clear cytokine correlations |

| Subtype | HRV Parameter | Trend | Study Reference | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ER+ | HF (ms²) | Higher in early stages | Taranikanti et al. [16] | p<0.01 |

| ER+ | RMSSD (ms) | Improved with VNS | Luna-Alcala et al. [11] | p<0.05 |

| TNBC | HF (ms²) | No significant change | Taranikanti et al. [16] | NS* |

| TNBC | SDNN (ms) | Reduced post-chemo | Stachowiak et al. [6] | p<0.01 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).