1. Introduction

Aquaculture has become an essential strategy to meet the escalating global demand for animal protein, contributing significantly to food security, livelihoods, and economic growth-particularly in developing nations. According to FAO (2022), global aquaculture production has exceeded 87.5 million metric tons, driven largely by the expansion of finfish and crustacean farming. However, the rapid intensification of aquaculture practices has introduced several challenges, including deteriorating water quality, increased disease outbreaks, overdependence on antibiotics, and compromised fish welfare. These issues not only hinder productivity but also pose serious risks to environmental sustainability and public health, especially due to the emergence of antibiotic-resistant bacteria (Ringø et al., 2010).

In response to these growing concerns, the aquaculture industry is increasingly adopting functional feed additives-particularly probiotics and prebiotics-as eco-friendly alternatives to conventional chemotherapeutics. Probiotics are live microorganisms that, when administered in adequate quantities, confer health benefits to the host by modulating gut microbiota, improving nutrient assimilation, and enhancing immune responses (Fuller, 1989). Prebiotics, in contrast, are non-digestible dietary components that selectively promote the growth and activity of beneficial gut microbes, thereby improving gut health and immunity (Gibson & Roberfroid, 1995). When used in combination, these additives form synbiotics, offering synergistic effects that have gained increasing attention in commercial aquafeed development (Hai, 2015).

This review aims to provide a comprehensive overview of the use of probiotics and prebiotics in aquaculture. It begins with a discussion of their types and sources, followed by an analysis of their mechanisms of action. Subsequent sections examine their documented benefits-including growth promotion, immune modulation, and disease resistance-across various aquatic species. The paper also discusses application strategies, current limitations, and emerging challenges in their formulation and use. Finally, the review explores future directions such as nano-formulations, omics-driven personalization, and artificial intelligence (AI)-based feed optimization for sustainable and precision aquaculture.

2. Types and Sources

2.1. Common Probiotics Used in Aquaculture

In aquaculture, probiotics include a diverse group of beneficial microorganisms that are intentionally introduced into the aquatic environment or fish feed to improve the health and performance of farmed species. Among the bacterial strains commonly used, Bacillus, Lactobacillus, Pediococcus, Enterococcus, and Streptococcus are well-documented for their probiotic efficacy. Bacillus subtilis and Bacillus licheniformis are particularly favored in commercial formulations because of their ability to form endospores, which enhance their stability during feed processing and storage. These strains are known for producing antimicrobial peptides, competitive exclusion of pathogens, and modulating host immunity by stimulating cytokine expression and enhancing phagocytic activity (Nayak, 2010; Ringø et al., 2010).

Lactic acid bacteria (LAB), including Lactobacillus plantarum and Lactobacillus rhamnosus, play a crucial role in maintaining gut health through acid production, pathogen inhibition, and strengthening of the gut epithelial barrier. Their presence in the gastrointestinal tract (GIT) has been shown to reduce intestinal inflammation, enhance digestive enzyme activities, and improve survival rates in species such as tilapia, carp, and catla.

In addition to bacterial probiotics, yeast strains like Saccharomyces cerevisiae have gained popularity in aquaculture due to their rich content of bioactive components such as β-glucans, mannan-oligosaccharides (MOS), nucleotides, and antioxidants. These compounds stimulate the innate immune system, bind pathogenic toxins, and promote gut morphological improvements (Li & Gatlin, 2004). Some photosynthetic bacteria (Rhodopseudomonas, Rhodobacter) and Pseudomonas species are also used, particularly in shrimp farming, for their water-purifying and probiotic effects. The selection of probiotic species is often influenced by host species, environmental parameters (temperature, salinity, pH), and compatibility with feed formulations.

2.2. Prebiotics and Their Sources

Prebiotics are non-digestible oligosaccharides or fiber-like substances that selectively promote the proliferation of beneficial gut bacteria, especially Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium. Unlike probiotics, prebiotics do not contain live organisms but act as a substrate or energy source for the host’s endogenous microbiota. In aquaculture, common prebiotics include inulin, fructo-oligosaccharides (FOS), galacto-oligosaccharides (GOS), mannan-oligosaccharides (MOS), and β-glucans. These compounds enhance gut microbial diversity, short-chain fatty acid (SCFA) production, and immune cell responsiveness (Merrifield et al., 2010).

Plant-derived ingredients such as chicory root (source of inulin), garlic, onion, and banana peel contain naturally occurring prebiotic compounds and have been investigated for aquafeed use. Additionally, yeast cell wall extracts and marine polysaccharides (e.g., alginate, laminarin) are being explored as functional prebiotics. Notably, MOS derived from Saccharomyces cerevisiae cell walls have been shown to improve intestinal morphology and resistance to Aeromonas infections in tilapia and carp. The selection of prebiotics depends on cost, availability, host gut microbiome compatibility, and synergistic potential with probiotic strains when used as synbiotics.

2.3. Synbiotics and Combined Use

Synbiotics are defined as synergistic combinations of probiotics and prebiotics that enhance the survival and colonization of beneficial microbes in the host gut. Unlike independent use, synbiotics ensure that administered probiotic strains receive the required nutritional substrate (prebiotics), thereby enhancing their persistence and activity. For example, dietary inclusion of Bacillus subtilis with mannan-oligosaccharides (MOS) has been shown to significantly improve growth performance and immune responses in tilapia and carp (Zhou et al., 2020; Kumar et al., 2018).

Additionally, synbiotics have demonstrated superior results in modulating gut microbiota, increasing short-chain fatty acid production, and improving disease resistance compared to probiotics or prebiotics alone. The effectiveness of synbiotics largely depends on the compatibility between the microbial strain and the selected prebiotic. Therefore, rational design of synbiotic formulations based on species-specific gut microbiota is essential for maximizing their functional benefits in aquaculture.

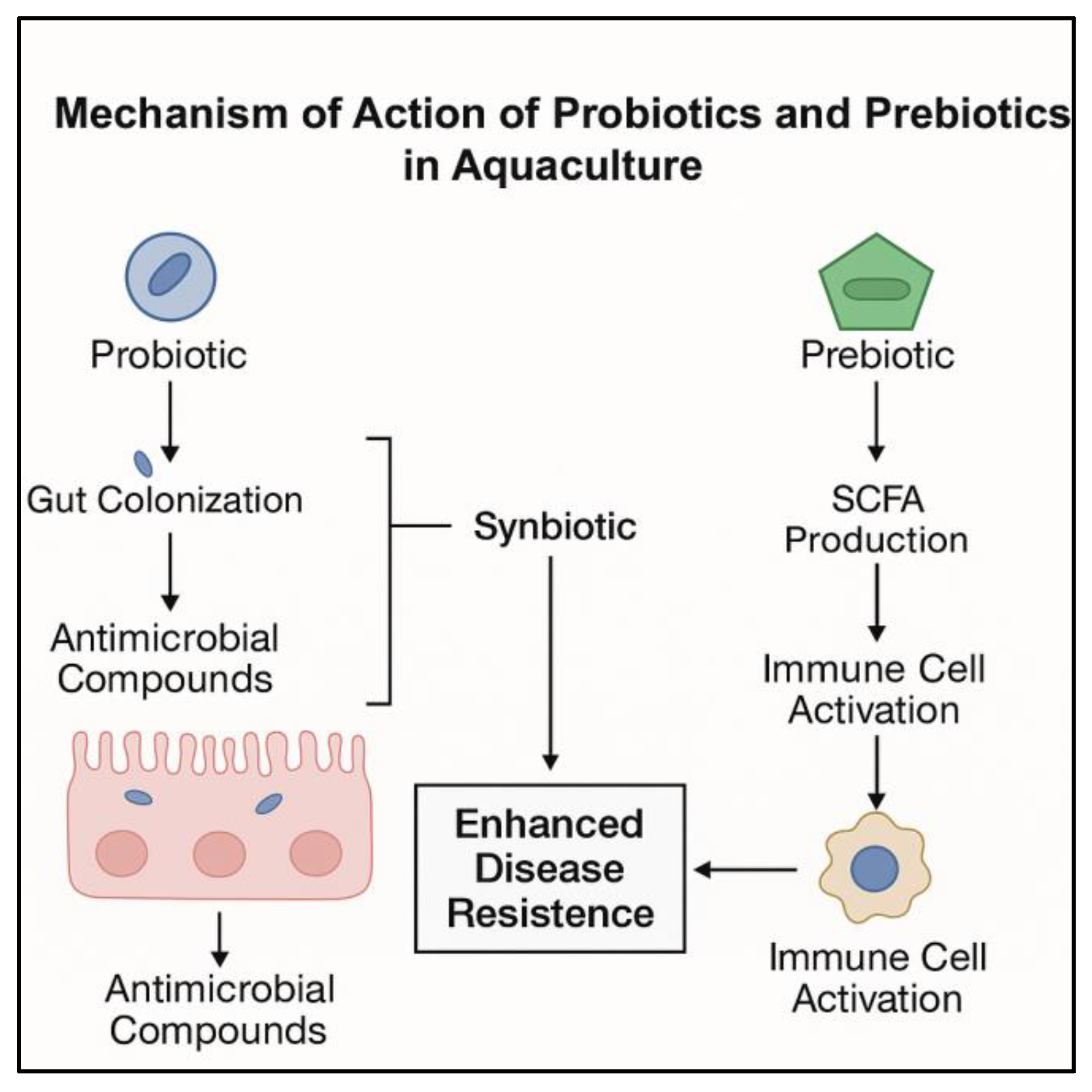

3. Mechanisms of Action of Probiotics and Prebiotics in Aquaculture

3.1. Modulation of Gut Microbiota

One of the primary mechanisms through which probiotics exert their beneficial effects in aquaculture species is by modulating the composition and functional activity of the gut microbiota. The gastrointestinal tract (GIT) of fish and other aquatic organisms harbors a diverse microbial community that plays essential roles in digestion, nutrient assimilation, and immune system development. When administered through feed or water, probiotics compete with pathogenic microbes for adhesion sites and nutrients, thereby limiting pathogen colonization and virulence. In addition, certain probiotic strains such as Bacillus subtilis and Lactobacillus plantarum secrete antimicrobial agents like bacteriocins and organic acids (e.g., lactic acid), which directly inhibit the growth of common pathogens including Aeromonas hydrophila and Vibrio species (Nayak, 2010).

Prebiotics act as selective substrates for beneficial gut microbes, primarily Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium, supporting their growth and activity. Upon fermentation in the gut, they produce short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) that contribute to lowering intestinal pH, creating an unfavorable environment for pathogenic bacteria. These SCFAs also serve as an energy source for intestinal epithelial cells, promoting mucosal integrity and enhancing host immune defenses. Together, probiotics and prebiotics promote a stable gut microbiota. This leads to better digestion, nutrient absorption, and overall health in fish.

3.2. Immune System Stimulation

Another key function of probiotics and prebiotics in aquaculture is the stimulation of the host immune system, particularly the innate immune response, which serves as the first line of defense against pathogens. Probiotics can upregulate the expression of immune-related genes, including those encoding lysozyme, complement proteins (C3, C4), and cytokines such as interleukin-1β and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α). These changes lead to stronger immune defense and pathogen resistance. For example, supplementation with Lactobacillus rhamnosus and Bacillus amyloliquefaciens has been shown to enhance the expression of pro-inflammatory and antiviral genes in species like tilapia and catfish.

Prebiotics, particularly β-glucans and mannan-oligosaccharides (MOS), also play a significant role in modulating immune responses. These compounds act as pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs), which are recognized by pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) on immune cells. This interaction triggers downstream signaling cascades that promote the production of antimicrobial peptides and inflammatory mediators. Notably, β-glucans derived from yeast cell walls have been shown to improve survival rates and resistance against Streptococcus iniae in hybrid striped bass and Edwardsiella tarda in catla (Li & Gatlin, 2004).

3.3. Enhancement of Digestive Enzyme Activity

Probiotics have been shown to enhance both the production and activity of digestive enzymes in fish, including protease, amylase, lipase, and cellulase. These enzymes are essential for the breakdown of proteins, carbohydrates, and lipids, thereby improving nutrient assimilation and feed digestibility. Certain strains, such as Bacillus licheniformis, are known to secrete exogenous enzymes that complement the host’s digestive processes, particularly in species with limited endogenous enzyme production, such as catla and common carp (Merrifield et al., 2010). Additionally, probiotics can stimulate the intestinal epithelium to produce higher levels of endogenous enzymes, further enhancing metabolic efficiency and nutrient uptake.

Prebiotics, although not directly involved in enzyme production, indirectly support digestive function by promoting a healthier gut environment. Their fermentation in the intestine leads to morphological improvements such as increased villus height, crypt depth, and brush border surface area-anatomical changes associated with improved nutrient absorption. In fish fed with prebiotics like inulin or MOS, studies have reported enhanced protease and amylase activity, resulting in better feed conversion ratios (FCR) and higher weight gain.

3.4. Pathogen Inhibition and Biofilm Disruption

Beyond their role in gut microbiota modulation, probiotics can directly inhibit pathogenic bacteria through disruption of quorum sensing and biofilm formation. Many aquatic pathogens, such as Vibrio and Aeromonas species, rely on biofilm development to establish chronic infections and evade antimicrobial treatments. Certain probiotic strains produce quorum-quenching enzymes or biosurfactants that interfere with bacterial communication and compromise biofilm structural integrity (Zhou et al., 2020). Additionally, probiotic supplementation has been shown to reduce pathogen adhesion to the intestinal epithelium and promote their elimination through fecal expulsion.

When combined with prebiotics, this antagonistic effect is further amplified due to increased proliferation and metabolic activity of beneficial microbes. For instance, mannan-oligosaccharides (MOS) can bind to the fimbrial structures of enteric pathogens, preventing their attachment to epithelial surfaces and thereby reducing the likelihood of infection.

Figure 1 illustrates the complementary roles of probiotics and prebiotics in promoting gut health and immunity through synbiotic interactions.

4. Benefits of Probiotics and Prebiotics in Aquaculture

4.1. Enhanced Growth Performance

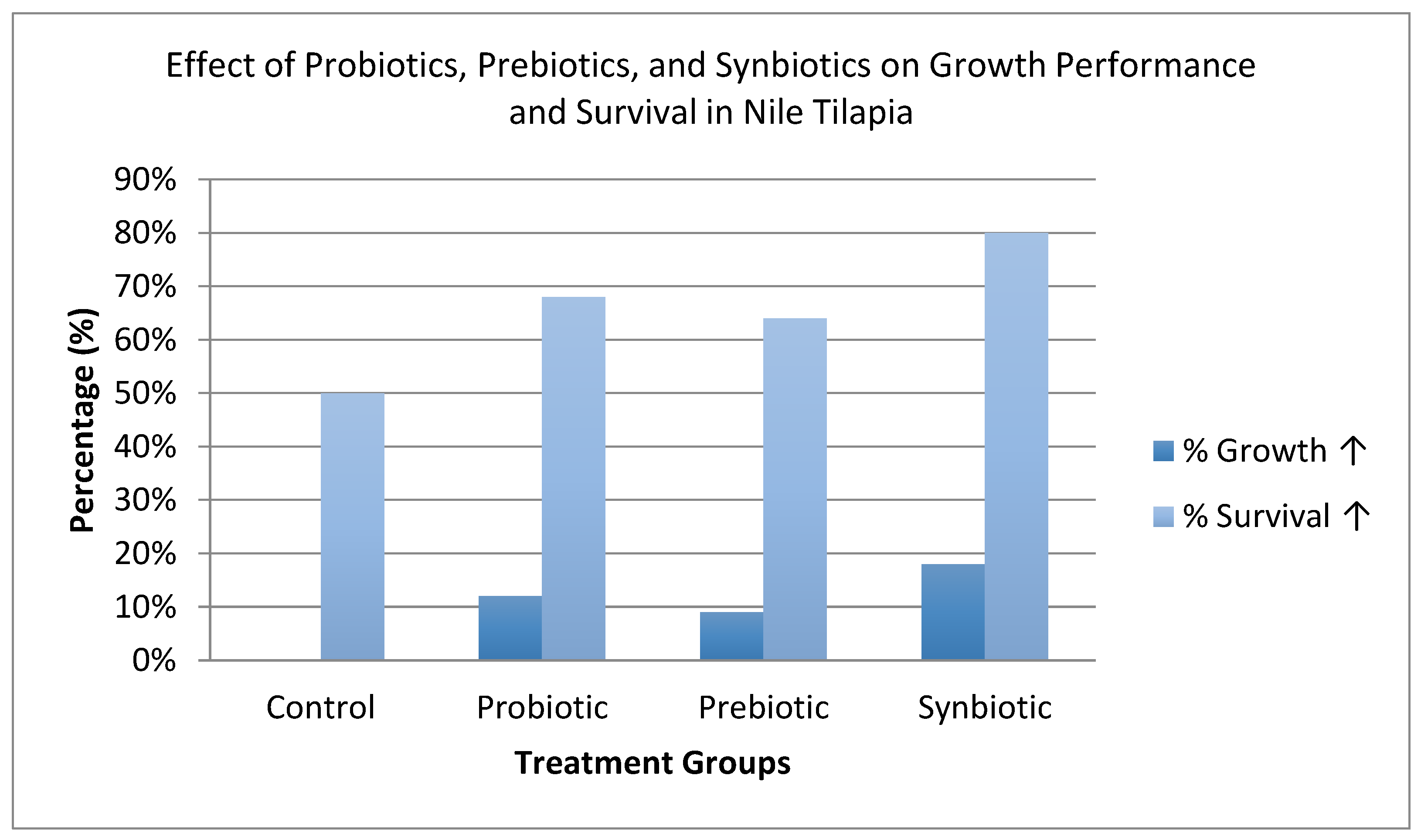

One of the most consistently reported benefits of probiotic and prebiotic supplementation in aquaculture is the enhancement of growth performance. Farmed fish and crustaceans receiving probiotic strains such as Bacillus subtilis, Lactobacillus rhamnosus, or yeast-derived additives often demonstrate significantly higher weight gain, improved specific growth rate (SGR), and reduced feed conversion ratio (FCR) compared to untreated controls. These improvements are linked to better nutrient assimilation and weight gain.

Prebiotics such as inulin and mannan-oligosaccharides (MOS) further potentiate these effects by promoting the proliferation of beneficial gut microbes. These microbes ferment prebiotic substrates into short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), thereby creating an energy-rich and microbially balanced gut environment. Studies conducted on Nile tilapia and common carp have reported statistically significant improvements in final body weight and protein efficiency ratio (PER) following dietary inclusion of probiotics or prebiotics (Zhou et al., 2020).

4.2. Improved Feed Utilization and Digestibility

Fish supplemented with probiotics often demonstrate improved feed utilization, resulting in enhanced growth efficiency and potential economic benefits for commercial aquaculture operations. This improvement is attributed to both direct and indirect mechanisms. Certain probiotic strains secrete exogenous digestive enzymes such as amylase, protease, and lipase, while others stimulate the production of endogenous enzymes within the host’s gastrointestinal tract. For instance, dietary supplementation of Bacillus licheniformis in catla and rohu has been associated with elevated activities of protease and lipase enzymes (Kumar et al., 2018).

In parallel, prebiotics such as β-glucans contribute to improved digestive function by enhancing intestinal health. They promote epithelial cell proliferation and mucin secretion, which collectively improve nutrient absorption. These physiological changes lead to reduced fecal nutrient loss and lower organic waste discharge, thereby minimizing water pollution and contributing to more environmentally sustainable aquaculture practices.

4.3. Enhanced Disease Resistance

Disease outbreaks represent a significant challenge in aquaculture, particularly in high-density farming systems and environments with limited biosecurity measures. The application of probiotics and prebiotics has emerged as an effective biological strategy to enhance the innate immune response of aquatic organisms, thereby increasing their resistance against prevalent pathogens such as Aeromonas hydrophila, Vibrio harveyi, and Edwardsiella tarda. Numerous studies have reported that supplementation with probiotics leads to elevated leukocyte counts, increased lysozyme activity, enhanced complement system function, and improved phagocytic capacity in fish (Hai, 2015). Yeast-derived β-glucans are especially known for activating macrophages and neutrophils, enhancing disease resistance. Field trials conducted on commercially important species including tilapia, catfish, and shrimp have demonstrated reduced mortality rates and improved post-challenge survival following synbiotic administration prior to pathogen exposure (Merrifield et al., 2010). These findings highlight the promising role of probiotic and prebiotic supplementation in bolstering disease resistance and improving aquaculture sustainability.

4.4. Stress Tolerance and Water Quality Improvement

Aquaculture species frequently encounter various environmental stressors including temperature fluctuations, handling, transportation, ammonia accumulation, and hypoxic conditions. Such stress adversely affects growth performance, immune competence, and overall survival rates. Multiple probiotic strains have been documented to mitigate stress by reducing cortisol levels and oxidative stress biomarkers in fish subjected to environmental challenges (Zhou et al., 2020).

Additionally, the application of probiotics such as

Rhodobacter sphaeroides in shrimp culture systems has been associated with significant reductions in ammonia and nitrite concentrations, thereby enhancing water quality and minimizing risks of gill pathology and metabolic disorders. Prebiotics indirectly support stress resilience by stabilizing gut microbial homeostasis and maintaining digestive function, which is particularly critical in intensive recirculating aquaculture systems (RAS). Collectively, these biological interventions contribute to improved health and productivity in aquaculture operations. The comparative benefits of probiotics, prebiotics, and synbiotics on growth and survival in tilapia are presented in

Figure 2.

4.5. Positive Effects on Reproduction and Larval Development

Although less extensively investigated, accumulating evidence indicates that probiotics and prebiotics can positively influence reproductive performance and early larval development in certain aquatic species. Lactobacillus and Bacillus strains improve sperm motility, egg quality, and fecundity in broodstock diets (Balcázar et al., 2006). In larval stages, administration of probiotics or synbiotics has been associated with improved gut maturation and increased survival rates. These findings carry significant implications for hatchery management, particularly for species exhibiting sensitive larval phases such as catla, milkfish, and ornamental fish.

Table 1.

Commonly used probiotics, prebiotics, and synbiotics in aquaculture species along with their sources and documented benefits.

Table 1.

Commonly used probiotics, prebiotics, and synbiotics in aquaculture species along with their sources and documented benefits.

| Species |

Additive Type |

Source/Strain |

Reported Effects |

Reference |

| Tilapia |

Probiotic |

Bacillus subtilis |

Growth enhancement, disease resistance (Streptococcus, Aeromonas) |

Zhou et al., 2020 |

| Prebiotic |

MOS (Yeast cell wall) |

Improved gut morphology, SCFA production |

Merrifield et al., 2010 |

| Synbiotic |

B. subtilis + MOS |

Better FCR, immune gene upregulation |

Kumar et al., 2018 |

| Common Carp |

Probiotic |

Lactobacillus plantarum |

Enhanced enzyme activity, reduced gut inflammation |

Nayak, 2010 |

Prebiotic

Synbiotic |

Inulin |

Improved growth performance, gut integrity |

Ringø et al., 2010 |

|

L. plantarum + Inulin |

Increased survival and microbial diversity |

Zhou et al., 2020 |

| Catla |

Probiotic |

Bacillus licheniformis |

Improved protease/lipase activity, antioxidant status |

Kumar et al., 2018 |

| Prebiotic |

β-glucan |

Resistance to Edwardsiella, improved immune response |

Li & Gatlin, 2004 |

| Synbiotic |

B. licheniformis + β-glucan |

Reduced mortality, enhanced phagocytic activity |

Merrifield et al., 2010 |

| Shrimp (L. vannamei) |

Probiotic |

Rhodobacter sphaeroides, Pseudomonas

|

Improved water quality, reduced Vibrio infections |

Hai, 2015 |

| Prebiotic |

MOS, β-glucan |

Enhanced hemocyte count, better molting, ammonia stress tolerance |

Wang et al., 2008 |

| Synbiotic |

B. subtilis + MOS |

Boosted survival under stress, enhanced digestion |

Zhou et al., 2020 |

5. Application Methods of Probiotics and Prebiotics in Aquaculture

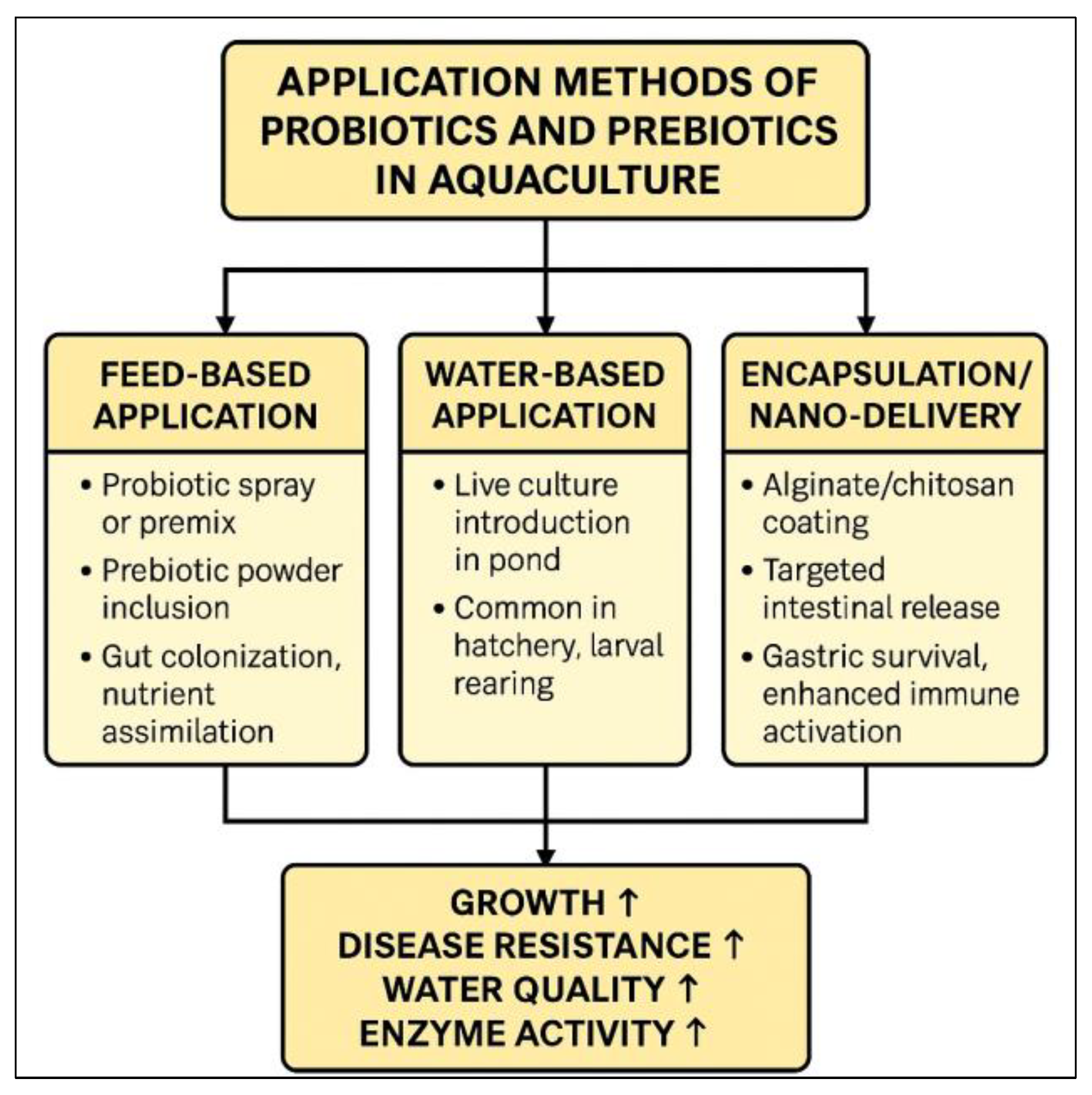

5.1. Feed-Based Supplementation

Feed-based supplementation remains the most prevalent and effective approach for delivering probiotics and prebiotics in aquaculture. Probiotic microorganisms are either applied via spraying onto pelleted feeds post-cooling or incorporated during feed production using techniques such as microencapsulation or spore formation. Prebiotics like inulin, mannan-oligosaccharides (MOS), and β-glucans are typically added as dry powders or water-soluble additives. This method promotes effective gut colonization and steady immune support through consistent intake. Empirical studies have demonstrated that supplementation of commercial feeds with Bacillus subtilis or Lactobacillus rhamnosus significantly enhances growth performance, feed conversion efficiency, and survival rates in species such as tilapia, catla, and shrimp (Hai, 2015; Merrifield et al., 2010).

Additionally, dietary inclusion of MOS has been associated with improved gut histomorphology, characterized by elongated villi and increased mucosal surface area, facilitating nutrient absorption and pathogen exclusion. However, high-temperature extrusion during feed processing often reduces probiotic viability. To address this, heat-resistant spores of Bacillus spp. are preferred, and post-pelleting top-coating with live probiotic cultures is commonly employed. Probiotics require cool, dry storage to maintain stability and effectiveness.

5.2. Water-Based Application

In hatcheries and open pond systems, the direct application of probiotics into rearing water is a widely adopted practice, particularly in larval rearing tanks and shrimp ponds. Live probiotic strains such as Rhodobacter, Pseudomonas, and Lactobacillus are introduced into the aquatic environment where they competitively inhibit pathogenic microorganisms, improve water quality, and colonize the skin, gill, and gastrointestinal surfaces of cultured species. This water-based administration is especially beneficial for early larval stages that may not readily consume solid feed or where feed-based gut colonization is inadequate (Balcázar et al., 2006). Moreover, this approach is integral to biofloc technology and recirculating aquaculture systems (RAS), where microbial community balance is critical for system stability. Nevertheless, environmental factors such as pH, temperature, and organic load can significantly affect probiotic viability and efficacy. Consequently, frequent reapplication and rigorous monitoring of probiotic populations are essential to maintain consistent and effective microbial presence in these systems.

5.3. Encapsulation and Nano-Delivery Systems

To improve the stability and targeted release of probiotics and prebiotics, advanced delivery systems such as microencapsulation and nanotechnology are gaining momentum. Encapsulation involves enclosing live microbial cells or prebiotic compounds within protective matrices made of alginate, chitosan, gelatin, or lipids. This protects the bioactives from environmental stress, stomach acidity, and ensures release in the intestine where they exert their effects. For example, chitosan-encapsulated Lactobacillus plantarum has shown improved survival in simulated gastric fluids and higher colonization in the posterior intestine of fish (Zhou et al., 2020).

Nanoparticles offer even greater precision, allowing delivery of bioactives at the cellular or molecular level. Although still under research, nano-prebiotics or nano-probiotic composites show promise in enhancing immune responses, reducing required dosages, and minimizing wastage. However, biosafety, cost-effectiveness, and regulatory approval remain key considerations before widespread adoption in commercial aquaculture. A schematic overview of the different application methods for probiotics and prebiotics is presented in

Figure 3.

6. Species-Specific Responses to Probiotics and Prebiotics

6.1. Finfish Species (Tilapia, Carp, Catla, etc.)

Finfish are the most extensively studied group in aquaculture when it comes to the application of probiotics and prebiotics. Among these, Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus), common carp (Cyprinus carpio), rohu (Labeo rohita), and catla (Catla catla) have received significant attention due to their commercial importance and high tolerance to dietary interventions. In Nile tilapia, supplementation with Lactobacillus plantarum or Bacillus subtilis has been shown to improve growth performance, digestive enzyme activity, and disease resistance against Streptococcus agalactiae (Zhou et al., 2020). Similarly, the use of mannan-oligosaccharides (MOS) or inulin in tilapia diets has led to increased villus height and improved gut microbial diversity, resulting in better nutrient absorption and immune modulation.

In Indian major carps such as rohu and catla, probiotic strains like Bacillus licheniformis, Pediococcus acidilactici, and yeast-derived β-glucans have shown promise in enhancing antioxidant status, non-specific immune parameters (e.g., lysozyme, respiratory burst), and resistance to pathogens like Aeromonas hydrophila and Edwardsiella tarda (Kumar et al., 2018). These species also respond well to synbiotic formulations, particularly when probiotics are paired with compatible prebiotics that support gut microbiota balance. Moreover, improvements in hematological profiles and survival during transport or handling stress have been observed, making these additives useful beyond just nutritional purposes.

6.2. Shellfish Species (Shrimp, Prawn, etc.)

Shellfish, especially penaeid shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei, Penaeus monodon) and freshwater prawn (Macrobrachium rosenbergii), are highly sensitive to environmental stress and microbial imbalance, making them ideal candidates for probiotic and prebiotic interventions. In shrimp farming, waterborne and feed-based application of probiotics such as Rhodobacter sphaeroides, Pseudomonas fluorescens, and Bacillus subtilis has been widely adopted to control pathogenic bacteria like Vibrio harveyi and V. parahaemolyticus, the causative agents of white spot and EMS (Early Mortality Syndrome) (Hai, 2015).

Shrimp and prawn supplemented with probiotics typically show enhanced phagocytic activity, increased total hemocyte count (THC), and better resistance to bacterial and viral challenges. Furthermore, yeast-derived MOS and β-glucans have been associated with improved gut morphology, feed conversion efficiency, and survival under low salinity or ammonia-stress conditions. Some studies have reported that long-term synbiotic feeding in shrimp can improve molting frequency and reduce mortality during peak growth phases (Wang et al., 2008). Overall, the species-specific response in shellfish appears to be highly dose- and environment-dependent, highlighting the importance of tailored probiotic-prebiotic formulations for each culture system.

6.3. Comparative Overview

While both finfish and shellfish benefit from the inclusion of probiotics and prebiotics, the magnitude and nature of their responses vary significantly due to differences in digestive physiology, immune architecture, and microbial colonization patterns. Finfish tend to show stronger improvements in feed utilization and gut morphology, whereas shellfish often exhibit more pronounced immunological and survival-related benefits.

Moreover, waterborne applications are more common and effective in shellfish culture systems, especially during larval and post-larval stages, while feed-based delivery remains the standard approach in finfish nutrition. Understanding these species-specific nuances is essential for designing effective feeding strategies and maximizing the benefits of functional feed additives in diverse aquaculture operations.

7. Challenges and Limitations

Despite the promising advantages of probiotics and prebiotics in aquaculture, several practical, biological, and regulatory challenges continue to impede their widespread and consistent implementation. These constraints must be carefully addressed to ensure sustained efficacy, cost-effectiveness, and safety within commercial aquaculture operations. Addressing issues such as probiotic viability during feed processing, environmental variability affecting microbial performance, potential risks related to biosafety, and compliance with regulatory frameworks is essential for the successful integration of these functional additives. Consequently, ongoing research and development, alongside stringent quality control measures, are critical to overcoming these barriers and realizing the full potential of probiotics and prebiotics in sustainable aquaculture.

7.1. Viability and Stability Issues

One of the foremost technical challenges is maintaining the viability of probiotic strains during feed processing and storage. Many beneficial microbes are heat-sensitive and may lose viability during high-temperature extrusion or prolonged storage, especially in tropical climates. Although Bacillus spp. spores are relatively stable, other strains like Lactobacillus and Pediococcus often require microencapsulation or post-pellet spraying to survive processing (Merrifield et al., 2010). Even after successful delivery, probiotic organisms must survive the acidic conditions of the stomach and establish in the intestine - a process influenced by the host’s gut environment, diet, and existing microbiota.

Prebiotics, while more stable, are not immune to challenges. Their efficacy depends on the presence of compatible beneficial microbes in the gut, and sometimes they may promote fermentation by opportunistic or non-target bacteria if used in excess or under dysbiotic conditions.

7.2. Host and Species-Specific Responses

The effects of probiotics and prebiotics are often highly variable depending on the fish or shellfish species, developmental stage, and environmental conditions. A formulation effective in tilapia may not yield the same results in catla or shrimp due to differences in gut physiology, immune system architecture, and feeding habits (Ringø et al., 2010). Moreover, genetic differences among probiotic strains - even within the same species - can significantly influence their bioactivity, colonization ability, and interaction with host tissues. This inter-strain variability complicates standardization and requires species-specific research before commercial implementation.

7.3. Quality Control and Regulation

The probiotic market in aquaculture is still loosely regulated in many regions, leading to inconsistent product quality. Several commercial products have been found to contain fewer viable organisms than declared, or to include undeclared strains, which could be ineffective or even harmful (Verschuere et al., 2000). In addition, the absence of global standards for probiotic/prebiotic testing, labeling, and approval delays scientific validation and farmer trust. There is also limited post-market surveillance on environmental impacts and residue risks, especially when large-scale or long-term use is involved.

7.4. Biosafety and Environmental Concerns

The introduction of live microbes into aquatic systems raises potential biosafety concerns, particularly in open water or biofloc systems. Probiotic strains that are non-native to the local microbial ecology might disrupt existing microbial communities, promote horizontal gene transfer, or inadvertently create antibiotic resistance reservoirs (Nayak, 2010). Overuse or uncontrolled application of prebiotics can lead to excessive fermentation, gas accumulation, or water fouling - all of which negatively impact fish health and pond ecology.

Therefore, rigorous strain selection, functional characterization, and eco-toxicological assessments are essential before approving probiotic or synbiotic formulations for mass use. Further, the long-term ecological effects of such interventions are still poorly understood and need dedicated research attention.

7.5. Economic Barriers and Farmer Adoption

Finally, cost-effectiveness remains a major bottleneck in low- and middle-income aquaculture systems. High-quality, scientifically validated probiotics or synbiotics often come at a premium price. Many smallholder farmers may lack access to cold-chain infrastructure, proper dosing instructions, or technical training to use these additives effectively. Moreover, the results from probiotic use are often not immediately visible, which discourages consistent use. Addressing these socio-economic limitations requires coordinated efforts in education, extension services, and government-supported demonstration projects to improve field-level adoption.

8. Future Perspectives

As the aquaculture industry continues to expand to meet global food demands, the need for more targeted, effective, and sustainable feed solutions is becoming increasingly critical. While the use of probiotics and prebiotics has already demonstrated significant benefits, future advancements must focus on improving their specificity, delivery, integration with advanced technologies, and long-term ecological compatibility.

8.1. Development of Next-Generation Probiotics and Synbiotics

Next-generation probiotics are being designed with enhanced host specificity, improved gut colonization ability, and greater resistance to environmental stressors. Advances in microbial genomics have enabled researchers to screen and engineer probiotic strains with known genetic profiles, functional genes (e.g., bacteriocin production, adhesion factors), and metabolic traits tailored for specific aquaculture species (Ghanbari et al., 2015). Similarly, synbiotics are being formulated not just as random combinations of probiotics and prebiotics, but as purpose-built functional consortia optimized for synergistic performance under varied aquaculture conditions.

8.2. Nanoformulations and Smart Delivery Systems

Emerging research is focusing on nano-encapsulation of probiotics and prebiotics using biodegradable polymers like chitosan, alginate, or lipid-based nanocarriers. These systems enhance the stability of the active ingredients, protect them from gastric degradation, and enable targeted release in specific sections of the gut. Smart delivery systems can also be designed to respond to environmental cues (e.g., pH, enzymes) and release bioactives accordingly. Preliminary studies have shown that nanoformulated synbiotics improve immunogenic response and gut microbiome modulation at lower doses than conventional formulations (Ramesh et al., 2022). However, cost, scalability, and biosafety still need to be addressed before widespread commercialization.

8.3. Integration with Omics and Precision Nutrition

The application of omics technologies-genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics-is revolutionizing our understanding of host-microbiota interactions. These tools can help identify species-specific gut microbiota profiles, immune biomarkers, and probiotic-host metabolic interactions, enabling precise formulation of functional feeds. For instance, transcriptomic studies can reveal how specific probiotics influence immune gene expression, while metabolomics can detect shifts in microbial fermentation products (Merrifield et al., 2010). Such data can be integrated into predictive models for more rational synbiotic design.

8.4. AI-Driven Feed Formulation and Decision Support Tools

Artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) algorithms are increasingly being used in feed formulation, performance prediction, and risk assessment in aquaculture. By analyzing large datasets from trials, water quality, species responses, and feed compositions, AI can recommend optimized synbiotic combinations tailored to local conditions and species. These platforms could also be integrated into digital farm management systems to automate dosage adjustments, feeding schedules, and health monitoring (Pérez-Rostro et al., 2021). Although still in early stages, AI-based tools offer immense promise for precision aquaculture.

8.5. Sustainability and LCA-Based Evaluation

As sustainability becomes a global priority, probiotics and prebiotics must also be evaluated from a life cycle assessment (LCA) perspective. LCA tools can estimate the environmental impact of functional feed production, transport, usage, and waste output. Future formulations must aim to minimize carbon and nutrient footprints, promote circular bioeconomy principles (e.g., use of agro-industrial waste for prebiotic extraction), and align with green aquaculture certifications. Such frameworks will not only improve product credibility but also assist policymakers and consumers in choosing environmentally responsible feed solutions.

9. Conclusions

The incorporation of probiotics and prebiotics into aquaculture feeding strategies signifies a substantial progression towards sustainable and health-focused aquatic food production. These bio-functional additives have been extensively demonstrated to enhance gut health, stimulate immune responses, promote growth performance, and provide targeted protection against bacterial pathogens in a species-specific manner. Their contributions to improving feed conversion efficiency and reducing environmental pollution further align with the objectives of eco-friendly aquaculture practices.

Nevertheless, despite notable advancements, several challenges persist, including probiotic viability during feed processing, species-specific variability in response, and regulatory discrepancies across different regions. Overcoming these obstacles necessitates a multidisciplinary approach encompassing microbiology, nutrition, immunology, biotechnology, and data science.

Future efforts should prioritize precision probiotic selection grounded in host-specific microbiome profiling, development of nano-encapsulation technologies for targeted delivery, and integration of omics tools alongside AI-driven formulation platforms. Additionally, life cycle assessment (LCA) modeling can serve to quantify the environmental benefits of functional feeds, thereby guiding policy and practical implementation.

In summary, probiotics and prebiotics are not universal solutions; however, when strategically selected, properly formulated, and judiciously applied, they hold significant potential to enhance aquaculture sustainability and fish welfare. Continued research, innovation, and field validation will be essential to fully realize their benefits in the next generation of aquafeed systems.

Funding

This review received no external funding.

Acknowledgements

The author gratefully acknowledges the encouragement and inspiration provided by friends, classmates, senior scholars, and teachers during the preparation of this manuscript.

Ethical Approval

This article is a review of previously published literature and does not involve any studies with human participants or animals performed by the author.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were generated or analyzed during the writing of this review article.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares that there is no conflict of interest related to this publication.

References

- Balcázar, J.L.; de Blas, I.; Ruiz-Zarzuela, I.; Vendrell, D.; Múzquiz, J.L. The role of probiotics in aquaculture. Veterinary Microbiology 2006, 114, 173–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FAO. The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2022; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Fuller, R. Probiotics in man and animals. Journal of Applied Bacteriology 1989, 66, 365–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghanbari, M.; Kneifel, W.; Domig, K.J. A new view of the fish gut microbiome: Advances from next-generation sequencing. Aquaculture 2015, 448, 464–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, G.R.; Roberfroid, M.B. Dietary modulation of the human colonic microbiota: introducing the concept of prebiotics. The Journal of Nutrition 1995, 125, 1401–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hai, N.V. The use of probiotics in aquaculture. Journal of Applied Microbiology 2015, 119, 917–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, S.; Sahu, N.P.; Pal, A.K.; Choudhury, D.; Yengkokpam, S.; Mukherjee, S.C. Dietary synbiotic effect on immunity, antioxidant status and resistance to Aeromonas hydrophila in catla (Catla catla). Fish & Shellfish Immunology 2018, 80, 479–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Gatlin, D.M. Dietary brewer’s yeast and the prebiotic GroBiotic™-A influence growth performance, immune responses and resistance of hybrid striped bass (Morone chrysops × M. saxatilis) to Streptococcus iniae. Aquaculture 2004, 231, 445–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merrifield, D.L.; Dimitroglou, A.; Foey, A.; Davies, S.J.; Baker, R.T.M.; Bøgwald, J.; Castex, M.; Ringø, E. The current status and future focus of probiotic and prebiotic applications for salmonids. Aquaculture 2010, 302, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayak, S.K. Probiotics and immunity: A fish perspective. Fish & Shellfish Immunology 2010, 29, 2–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez-Rostro, C.I.; Ibarra-Gámez, J.C.; Ramírez-Carrillo, E. Smart aquaculture and artificial intelligence in the feeding of shrimp: A review. Reviews in Aquaculture 2021, 13, 1441–1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramesh, D.; Souissi, S.; Rosales, C.; Wang, H. Recent trends in the nanoencapsulation of probiotics and prebiotics: Opportunities for aquaculture applications. Aquaculture Reports 2022, 24, 101166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringø, E.; Olsen, R.E.; Gifstad, T.Ø.; Dalmo, R.A.; Amlund, H.; Hemre, G.I.; Bakke, A.M. Prebiotics in aquaculture: a review. Aquaculture Nutrition 2010, 16, 117–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verschuere, L.; Rombaut, G.; Sorgeloos, P.; Verstraete, W. Probiotic bacteria as biological control agents in aquaculture. Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews 2000, 64, 655–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.B.; Xu, Z.R.; Xia, M.S. The effectiveness of commercial probiotics in Northern white shrimp (Penaeus vannamei L.) ponds. Fish & Shellfish Immunology 2008, 25, 471–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Wang, Y.; Gu, Q.; Li, W. Effects of synbiotics on tilapia: A review. Aquaculture Research 2020, 51, 961–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).