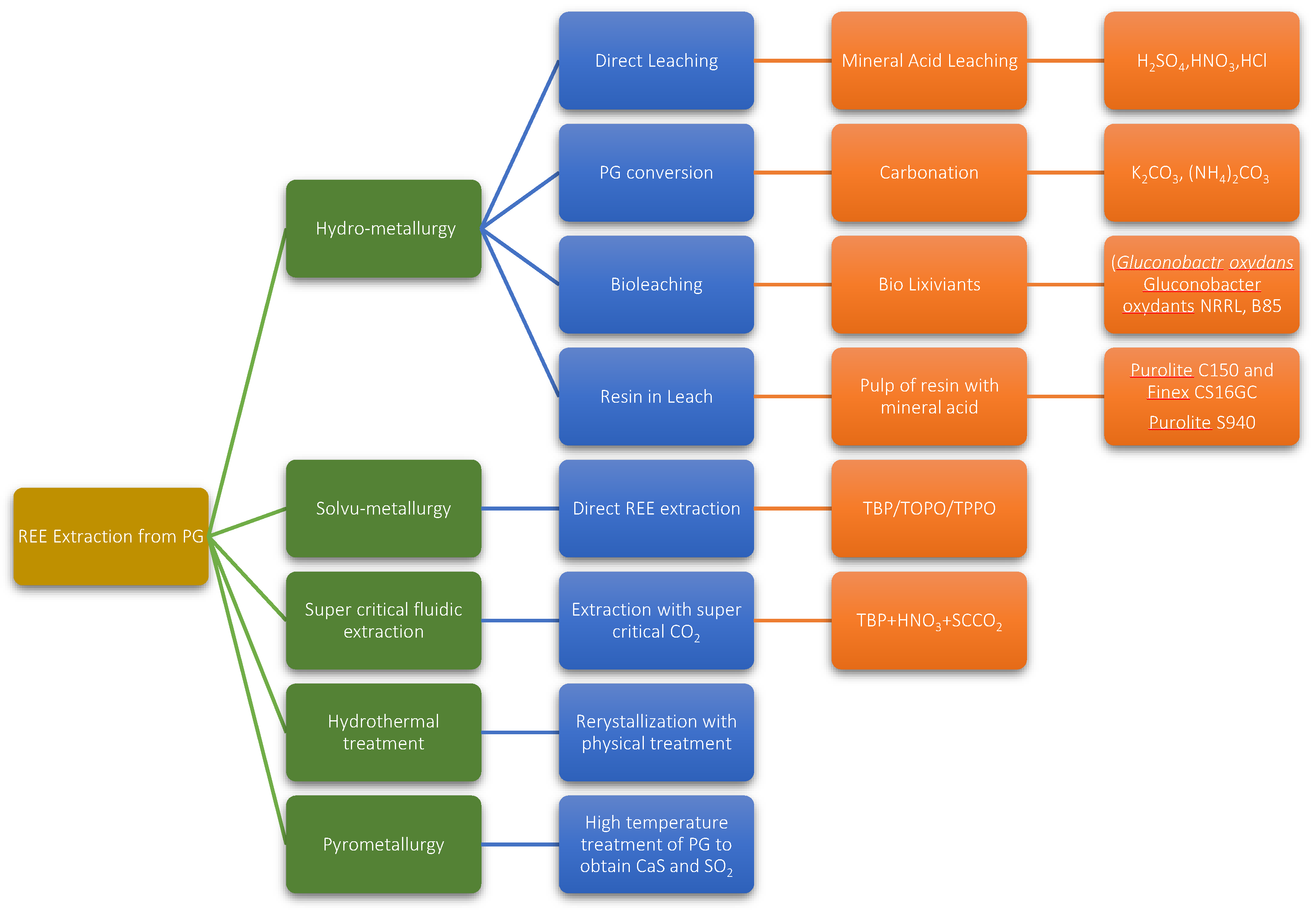

Hydrometallurgy involves the use of aqueous chemistry for the recovery of metals from ores, concentrates, and recycled or residual materials. This process is used in extraction of less electro positive or less reactive metals like gold and silver. Recently, hydrometallurgy was preferred over pyrometallurgical process since it is considered environmentally friendly since it is more energy efficient. Hydrometallurgy is typically divided into three general areas:

4.1.1. Mineral Acid Leaching

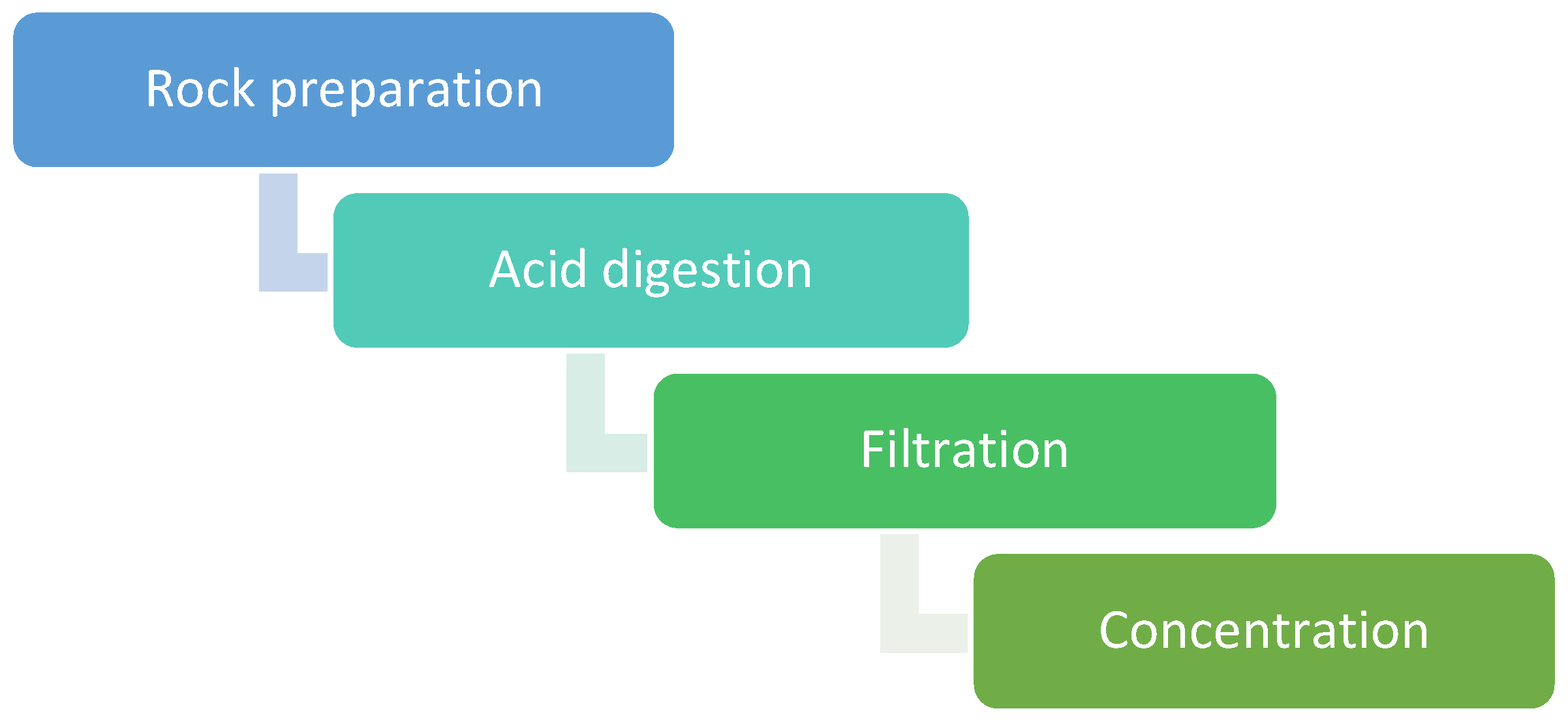

Leaching involves the use of aqueous solutions, which is brought into contact with a material holding a valuable metal; the solution may be acidic or basic. In the leaching process, oxidation potential, temperature, and pH of the solution are important parameters, and are often manipulated to optimize dissolution of the desired metal part into the aqueous phase. Mineral acid leaching is one of the most widely used methods for the extraction of rare earth metals from phosphogypsum.

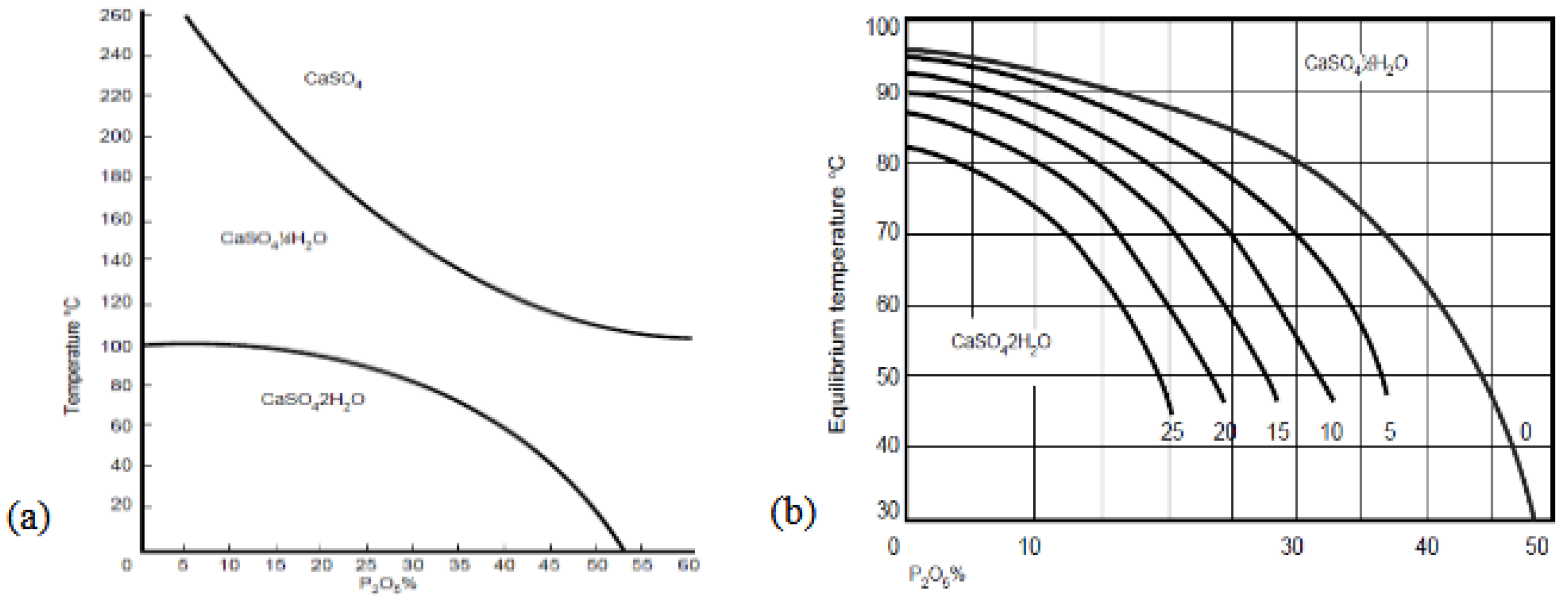

Sulfuric acid is the most common mineral acid used for the leaching of rare earth elements from phosphogypsum due to its easy availability and cost-effectiveness compared to other mineral acids. However, due to excess of sulphate ions in the reaction mixture it promotes the recrystallization of calcium as calcium sulphate at higher acid concentrations and at increased temperatures. This phenomenon occurs due to the common ion effect and the low solubility of calcium sulphate under such conditions, hindering the dissolution process and reducing the extraction efficiency.

To address these challenges, several studies have been conducted to investigate different operating conditions aimed at enhancing the extraction of REEs while minimizing the dissolution of unwanted impurities. Adjustments to acid concentration, temperature control, optimization of liquid-to-solid ratios, careful management of dissolution time, and the strategic use of additives have all been explored to improve the overall efficiency and selectivity of the mineral acid leaching process.

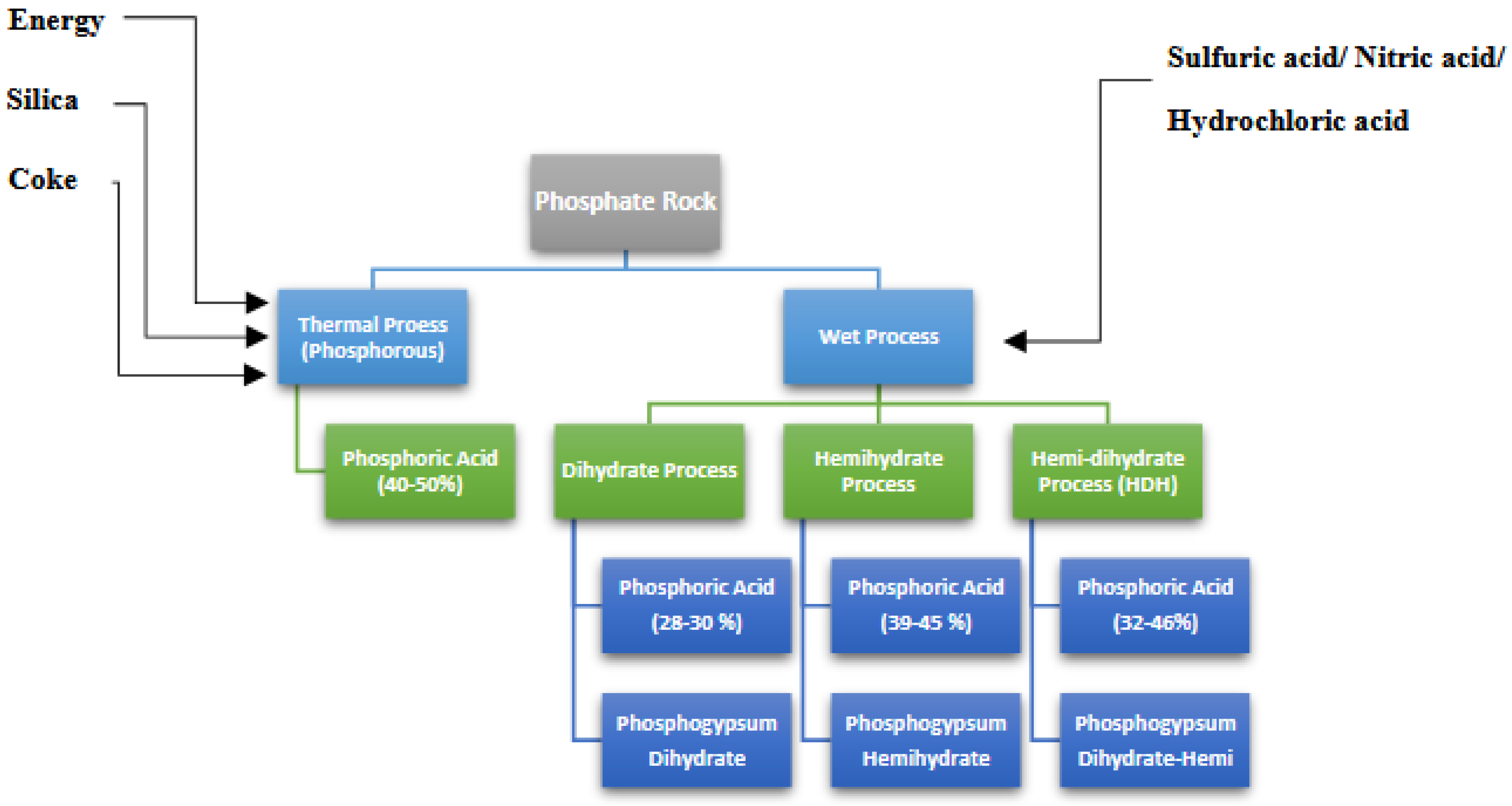

In a pilot scale study, the hemihydrate and dihydrate types of PG have been evaluated for the recovery of rare earth elements (REEs). The PG is produced through hemihydrate method, leaching is performed using diluted sulfuric acid at temperatures below 10°C, leading to a high REE recovery rate of about 80%. On the other hand, the dihydrate method evaluated at higher temperatures, typically between 50°C and 60°C, and at higher sulfuric acid concentration ranging from 10% to 15%, resulted in a lower REE recovery rate of approximately 52%. A significant advantage of the dihydrate process is the possibility of recrystallizing the leached phosphogypsum into anhydrite, which can be used as a raw material for cement production. Further process optimization in both methods often involves steps such as filtration, crystallization, and calcination to ensure efficient separation of valuable materials from waste streams [

53].

In a separate study, the use of mechano-activation to enhance REE solubility from phosphogypsum has been explored. Mechano-activation is conducted using a centrifugal ball mill under various conditions, including activation in air, in water suspensions, and in diluted hydrochloric and sulfuric acid solutions. Results show that activation in air significantly increases the solubility of phosphogypsum and facilitates the leaching of REEs into acid solutions. On the other hand, activation in water suspensions appears to reduce overall solubility but enriches the concentration of REEs in the dissolved fractions. When activated in acid suspensions, varying results are seen: activation in diluted hydrochloric acid leads to a slight increase in REE concentrations, while activation in sulfuric acid does not show a significant impact on REE recovery. The findings highlight that water-activated phosphogypsum samples treated later with 7% sulfuric acid show technological potential due to the enhanced enrichment of REEs in the resulting leachate [

54].

Low-concentration sulfuric acid treatment, using around 4 wt.% acid at room temperature, has also shown effectiveness in removing impurities such as fluorides and phosphates from phosphogypsum. This approach achieves high extraction efficiencies, with complete recovery of thorium, fluorine, sodium, and phosphorus, while uranium recovery reaches up to 93.1%. In addition to purifying the phosphogypsum for potential use in cement manufacturing, this method also enables the concurrent recovery of rare earth elements (REEs) [

55].

Laboratory-scale studies conducted at the Wizow Chemical Plant in Poland have shown REE recovery through a sulfuric acid leaching and crystallization strategy. The phosphogypsum is leached with 15% sulfuric acid extracted a rare earth concentrate with up to 25% lanthanide oxides. Following the leaching step, recrystallization transforms the remaining gypsum into anhydrite, which can be used as a high-quality construction material. Despite the encouraging results in terms of recovery and material valorization, the economic feasibility of the process is still a significant consideration, given the high initial investment costs associated with scaling up, although the ecological benefits are large [

56].

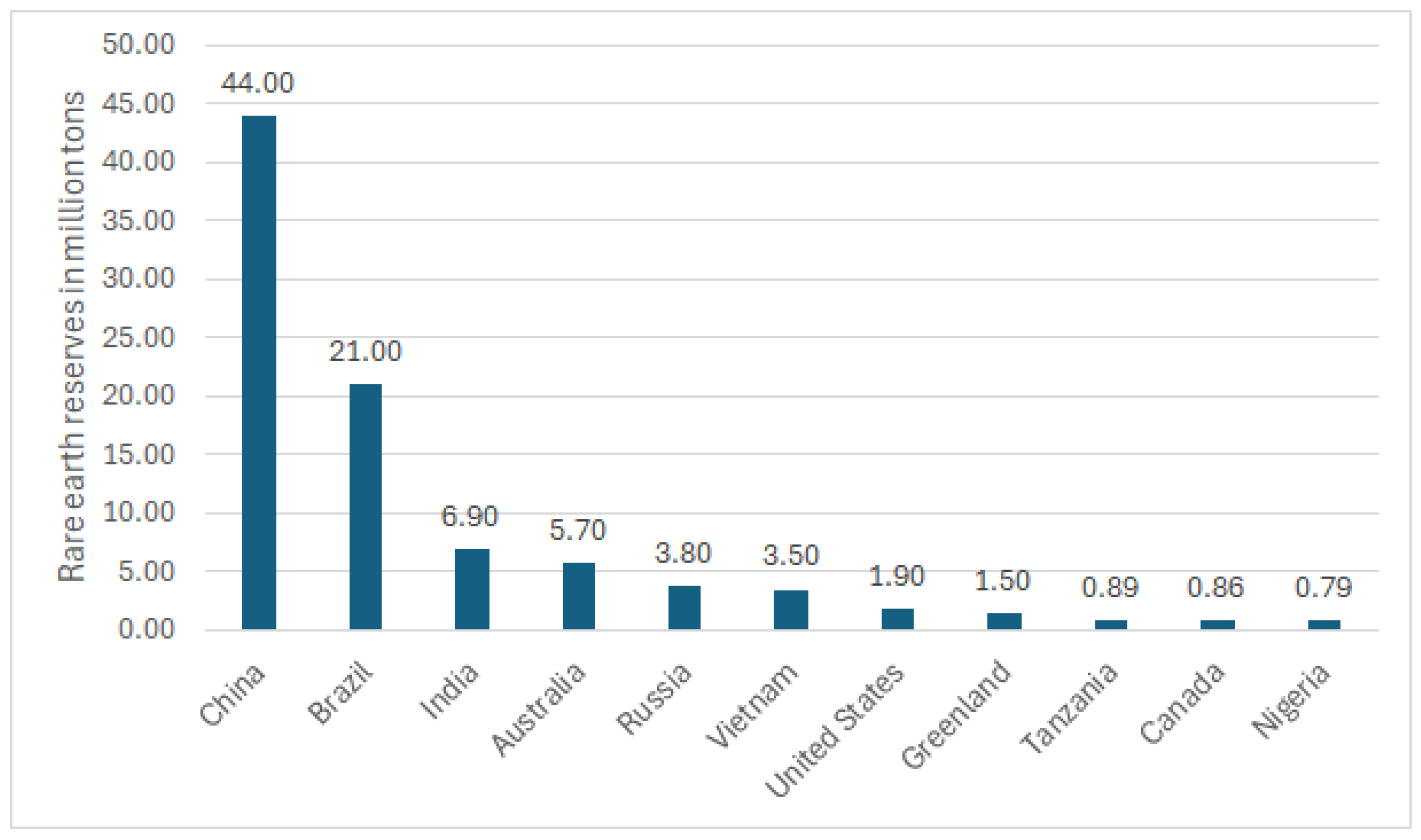

Further investigations into the extraction of rare earth elements (REEs) from phosphoric acid, phosphoric acid sludge (PAS), and phosphogypsum emphasize the economic potential of recovering valuable metals from phosphate processing streams. Ion exchange resins have proven effective for REE extraction from phosphoric acid, offering a viable route for recovery. Additionally, digestion of phosphogypsum with concentrated sulfuric and phosphoric acids, followed by solvent extraction, enables selective recovery of REEs, with heavy rare earth elements (HREEs) dominating the recovered fractions. Critical REEs account for about 45% of the total recovered metals, underscoring their strategic importance. Comparative studies show that nitric acid leaching of PAS achieves greater efficiency (58%) compared to sulfuric acid leaching (49%) [

57].

In another study, a two-step sulfuric acid leaching approach was applied to Tunisian phosphogypsum, showing substantial REE enrichment. The process involved washing and grinding the phosphogypsum, followed by sequential leaching at 60°C. This first leaching step increased the REE concentration in the solid residue by 52%. The later leaching phase dissolved REEs into the acid solution with a 50% dissolution rate. The final crystallized product, consisting of anhydrite and monazite, achieved a total REE enrichment of 86%, confirming the potential of this method for both purification of phosphogypsum and effective recovery of rare earth elements [

58].

When it comes to metals leaching, sulfuric acid is the first choice among researchers because of its easy availability, ease of handling and lower cost as compared to nitric acid and hydrochloric acid. However, the hydrometallurgical extraction of REEs from PG depends on the number of important factors such as type and concentration of acid, leaching temperature, solid to liquid ratio, contact time and the presence of other chemicals which could help in the release of REEs during the leaching phase.

A recent study showed that 25 g/l sulfuric acid concentration is best to leach up to 65 % REEs [

59]. In contrast, another recent study showed that it was possible to extract 92 % REE employing 2 M H

2SO

4, using undried, finely ground particles (≤200 µm), and maintaining a temperature of 60 ◦C [

60]. Apart from sulfuric acid, nitric acid and hydrochloric acid also showed good REE leaching efficiencies [

61]. The higher leaching efficiency of these acids could be linked to the PG solubility and complexation behavior of REEs with these acids, particularly cerium complex with HCl. On the other hand, nitric acid has strong oxidizing properties which could also lead to the increased REE dissolution. Another factor could be the fast kinetics of these acids over sulfuric acid helping in higher REEs leaching efficiency. However, higher leaching efficiencies obtained through nitric acid and hydrochloric come with the drawback of contaminated leachate, contaminated with other metal ions, so lowering REE selectivity and increasing downstream operation steps thus increasing overall cost of the process.

To increase the metals extraction efficiency, the requirement to completely dissolve PG in acid solution is still questionable among the researchers and a mixed observation is found throughout the literature review. Some studies insisted that it is mandatory to destroy the PG matrix to release the rare earth elements as they believe that the REEs are present in PG as isomorphous Ca

2+ substitutions as well as separate oxides and sulphate phases blocked inside PG crystal lattice. In a test conducted in Sverdlovsk region, Russia, they combined the grinding of phosphogypsum along with ultrasonic treatment to avoid the agglomeration of fine particles to see its effect on the leaching efficiency of phosphogypsum. However, the experiment does not effectively show the effect of grinding since the tests are performed with varying sulfuric acid concentrations, so putting in doubt the increased leaching efficiency is due to increased acid concentration or due to the grinding and ultrasonic effect [

62]. Whereas other studies oppose the idea of complete PG dissolution and support their observation with higher extraction efficiencies obtained without complete dissolution of PG [

59,

60].

Leaching temperature is a crucial factor for the extraction REEs from PG. Studies showed that higher leaching temperature promotes the release of REEs in the solution. However, increasing the temperature to enhance REEs leaching can only be done to a certain extent. This is because of the different solubility behavior of PG in water and in mineral acids. This behavior limits the increase in temperature up to certain point. In a recent study the researcher analyzed the PG solubility at different acid concentration at different leaching temperature. It was found that leaching at 45 °C with 2.5 M HCl and a 29.8 mL/g L/S ratio resulted in the high dissolution of PG, this could be associated with the transformation of calcium sulphate hydrates to soluble salt, CaCl

2 with a solubility of 1280 g/l. Similarly, in the HNO3 system, leaching at 85 °C with 2.1 M HNO

3 and 27.7 mL/g liquid-to-solid ratio also resulted in the high dissolution of PG, which could be linked to the generation of highly soluble salt, Ca (NO

3)

2 with a solubility of 3580 g/L. In the H

2SO

4 system, the dissolution rate of PG is significantly lower. The solid residue after leaching at 85 °C with 1.3 M H

2SO

4 and 30 mL/g liquid-to-solid ratio is anhydrite (CaSO4, S = 2.34 g/L), which is sparingly soluble and precipitates residue [

61].

Solid to liquid ratio is another key parameter for increasing the extraction efficiency of REEs from PG. A recent study employed Plackett–Burman design (PBD) method to screen the main influencing factor for the recovery of REEs from phosphogypsum and it was found that increasing solid to liquid ratio from 1/3 to 1/9 increased the extraction efficiency from 30 % to 83 %. However, during this change of solid to liquid ratio other parameters are also changed such as acid concentration and leaching temperature which could also have profound influence on the leaching efficiency putting this claim under doubt [

63]. However, from technological point of view, increasing too much the solid to liquid ratio makes the overall process unfeasible to scale since larger volumes means larger equipment sizes, increased liquid waste and increased number of steps to concentrate the REEs rich solution keeping in mind that the concentration of REEs in PG is significantly lower. All these factors will increase the cost capital as well as the operating cost of the plant.

REE Leaching kinetics is faster and equilibrium reaches typically within an hour thus making leaching time less important as compared to other factors mentioned above. However, there are contradicting references in literature about leaching kinetics, a study carried out in Egypt where they leached Egyptian low-P

2O

5 PG with hydrochloric, nitric, and sulfuric acid, and found that leaching with nitric and hydrochloric reached completion within 2 hours, but REE continued leaching with sulfuric acid for up to 8 hours [

64,

65]. On the other hand, another research presented that with 0.5 M H2SO4 and with 3 M HNO3, leaching was ≈ 90% complete within 2 hours [

66]. In a recent study it is reported that 87.5 % REEs leaching with 3.3 M HNO

3 achieved within 20 minutes time [

63].

Table 7 shows the operating conditions and leaching efficiency of REEs using different acid types and concentration.

Based on the compiled data, sulfuric acid (H₂SO₄) appears as the most widely used leaching agent for REEs from phosphogypsum. The highest reported leaching efficiency with H₂SO₄ is 92%, achieved at 60 °C using 2 M concentration, a solid-to-liquid (S/L) ratio of 0.125, and a contact time of 4 hours. Another notable efficiency (86%) was recorded with 0.5 M H₂SO₄ at 25 °C, S/L ratio 0.05, and 8 hours of leaching. For nitric acid (HNO₃), the best condition yielded an 87.55% recovery at 75 °C using 3.3 M HNO₃, S/L ratio of 0.111, and 20 minutes of contact time. Additionally, 2.1 M HNO₃ at 85 °C resulted in 83.5% Y, 77.8% Dy, and 7.6% Nd extraction. On the other hand, 2.5 M HCl at 45 °C with a low S/L ratio of 0.033 and just 20 minutes contact time achieved 98.5% Y, 94.6% Nd, and 86.1% Dy leaching efficiency. These results highlight that higher acid concentrations, elevated temperatures, and lower S/L ratios enhance REE extraction from phosphogypsum, with HCl delivering the most efficient recovery in the shortest time for selected elements.

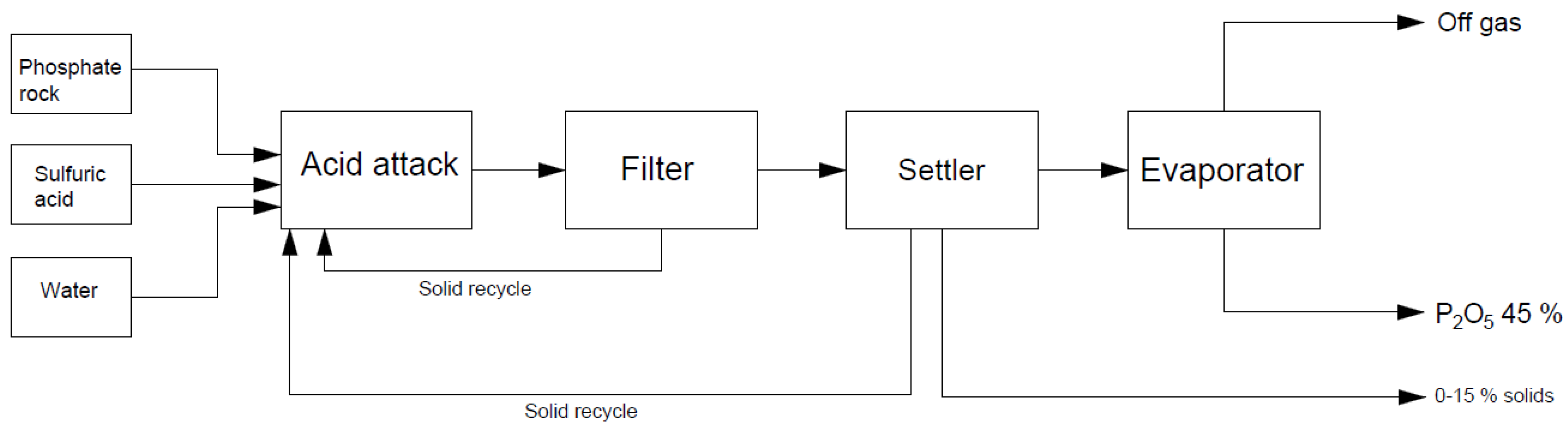

4.1.2. Phosphogypsum Conversion

During the conversion of phosphogypsum to ammonium sulfate using the Merseburg ammonium carbonation process, researchers analyzed samples from industrial-scale phosphoric acid plants to track the behavior of radionuclides such as U-238, Ra-226, Pb-210, and Po-210. The results revealed that these radio nuclides stay in the by-product calcium carbonate rather than transferring to the ammonium sulfate. This shows that the process effectively lowers the radioactive content in the final fertilizer product. For example, in Indonesian phosphogypsum samples, the activity of Ra-226 was recorded at 730 Bq/kg in the calcium carbonate compared to only 9 Bq/kg in the ammonium sulfate. These findings support the feasibility of the Merseburg process as a method to mitigate the environmental impact of phosphogypsum while simultaneously producing a valuable fertilizer [

74].

In another study, the production of potassium sulfate (K₂SO₄) from phosphogypsum and potassium carbonate (K₂CO₃) was evaluated. The research compared the reactivity of phosphogypsum with two types of synthetic gypsum, focusing on reaction efficiency under various temperatures and concentrations. Optimal conversion was achieved at 80°C using exact stoichiometric proportions of phosphogypsum and potassium carbonate, with a largest K₂SO₄ solubility of 1.2 mol/L after 1.5 hours of reaction time. The experiments showed that phosphogypsum was more reactive than synthetic gypsum, leading to complete conversion into potassium sulfate and calcite, while synthetic gypsum produced slower reactions and unwanted by-products. These findings highlight the efficiency and industrial potential of the process for reducing phosphogypsum waste while generating valuable products like K₂SO₄ and calcite [

75].

Another study explored the impact of residual sulfuric and phosphoric acids on the conversion of phosphogypsum waste into calcium carbonate, aiming to enhance the efficiency of phosphogypsum processing by removing acidic impurities that hinder its chemical reactivity. Researchers conducted experiments using dump phosphogypsum from Phosagro, Volkhov, which was washed in a jacketed glass HEL mono-reactor at 70°C under constant stirring at 200 rpm. This washing process successfully removed approximately 22% of impurities, including sulfuric and phosphoric acids. Subsequent conversion reactions were carried out using sodium carbonate (Na₂CO₃), potassium carbonate (K₂CO₃), and ammonium carbonate ((NH₄)₂CO₃), resulting in calcium carbonate yields of 70.6% and 65.0% for sodium and potassium carbonate reactions, respectively. The study concluded that washing phosphogypsum significantly improves its reactivity and enhances the yield of calcium carbonate, making it a more workable material for construction and paper industries.

Additionally, the study calculated the change in Gibbs free energy for reactions using Na₂CO₃, K₂CO₃, and (NH₄)₂CO₃. The results showed that reactions with Na₂CO₃ and K₂CO₃ are thermodynamically favorable under normal conditions without the need for elevated heat or pressure, showing Gibbs free energy changes of –37 kJ/mol and –58 kJ/mol, respectively. In contrast, the reaction with (NH₄)₂CO₃ was less favorable, with a positive Gibbs energy change of 166.7 kJ/mol, suggesting a lower probability of calcium carbonate formation. Enthalpy changes further revealed that reactions with Na₂CO₃ and K₂CO₃ are exothermic, releasing heat, while the reaction with (NH₄)₂CO₃ is endothermic and requires other energy input. The study suggests that further investigation is needed to improve the conditions for reactions with (NH₄)₂CO₃ to enhance its efficiency [

76].

4.1.4. Resin in leach

The resin-in-leach (RIL) method is an evolving hydrometallurgical technique designed for the selective recovery of rare earth elements (REEs) from complex matrices such as phosphogypsum (PG). This process involves the use of ion exchange resins which are directly added to the acidic leaching medium that has PG. In this way the process enables the simultaneous dissolution of REEs and their immediate capture by the resin. The integrated strategy could reduce the loss of REEs, minimize impurity interference, and simplify later separation processes. The RIL approach is particularly helpful for low-grade materials like PG, where achieving efficient and selective recovery is essential for both economic viability and environmental sustainability.

The research conducted by S. Al-Thyabat and P. Zhang focused on the extraction of rare earth elements (REEs) from phosphoric acid, phosphoric acid sludge (PAS), and phosphogypsum (PG) using ion exchange resin and solvent extraction techniques. Phosphoric acid samples were treated with ion exchange resin at varying temperatures (10–82°C) and resin dosages (3–7 kg/t), achieving extraction efficiencies of up to 65%. For PG, a mixture of concentrated sulfuric acid and recycled phosphoric acid was employed, followed by solvent extraction using DEHPA, reaching a maximum extraction efficiency of 59% after three stages. The study highlighted that heavy rare earth elements (HREEs) represented over 70% of the REEs in phosphoric acid, while critical REEs (CREEs) accounted for 45%. It was concluded that both temperature and resin dosage significantly affected extraction efficiency, with higher values improving the results [

57].

The research conducted by Ural Federal University (UrFU) and VTT focused on developing industrial technologies for extracting rare earth elements (REEs) and scandium from phosphogypsum and uranium in-situ leach (ISL) solutions. The study combined solvent extraction with advanced ion exchange methodologies in a pilot facility capable of treating 5 m³ of solution per hour. Leaching-absorption processes were supported by multicomponent solution modeling using VTT’s ChemSheet/Balas program. In the experiments, 45 tons of solids were processed, yielding 100 kg of REE concentrate. Additionally, a mini-pilot plant was used to recover scandium oxide and REE concentrates from uranium ISL solutions, achieving concentrations with 99% purity for both scandium oxide and REEs. The study found that the best conditions for REE extraction involved using macroporous sulfonated resins with a divinylbenzene (DVB) content of over 12%, which resulted in an extraction efficiency of 32.8% for REEs and 30-40% for scandium. Desorption using ammonium sulfate solution was effective, with a recommended concentration of 300 g/dm³ and a feed rate of five volumes per hour. The overall extraction efficiency for REEs was 32.8%, with scandium extraction varying between 30-40% [

79].

Another research investigated the potential of extracting rare earth elements (REEs) from phosphogypsum (PG) using Resin-in-Leach (RIL) technology. The method involved batch contacting PG with sulfuric acid and a strong acid cation exchange resin (Purolite C150TLH) at varying acid concentrations and ratios. The optimal conditions were found to be a sulfuric acid concentration of 10 g/L and an acid-to-PG ratio of 4:1. The tests showed that REE recovery efficiency varied significantly depending on the source of PG, with extraction efficiencies ranging from 15% to 80%. Despite the variability, the study concluded that RIL technology could be economically favorable, especially considering the mixed REE oxide product price of over

$21/kg, even with overall REE recovery as low as 15% [

80].

A separate study explored the use of a combination of mechanical grinding, ultrasonic impact, and resin-in-pulp (RIP) processes to enhance the leaching efficiency of rare earth elements (REEs) from phosphogypsum. The experiments involved treating 40g samples of phosphogypsum with 300mL of sulfuric acid solutions at concentrations ranging from 5 to 30g/L. Mechanical grinding was applied at 3000 rpm for 2 hours, followed by ultrasonic treatment at 50W power for 2 hours, and the addition of 40cm³ of cation exchange resin. The results showed that this combined treatment significantly increased REE recovery from 15-17% to over 70%. Additionally, the study has shown that the treated phosphogypsum could be used as a raw material for cement production, thus enhancing the economic feasibility of the process [

62].

Another study systematically investigated the selection of resin, leaching agent, and eluent to improve the recovery process. The experiments employed four different lixiviants H₂SO₄, HCl, and H₃PO₄ at varying concentrations. Using a chelating resin allowed for a low H₂SO₄ concentration (1 g/L) in the resin-in-leach (RIL) process, achieving a rare earth element (REE) loading of 19.2 g (REE)/kg (resin) and up to 20% purity after four stages. In contrast, strong acid resins reached only 3% purity. The study concluded that breaking the phosphogypsum (PG) structure or adsorbing calcium via the resin was unnecessary for enhancing REE recovery. For elusion, saturated sodium chloride solutions were effective for strong cation exchangers, while EDTA or concentrated hydrochloric acid was needed for the chelating resin. Overall extraction efficiency depended on the resin and leaching agent combination, with the chelating resin showing superior performance [

81].

Another study investigated enhancing the recovery efficiency of rare earth metals (REEs) from technological solutions generated during apatite raw material processing, particularly phosphogypsum, which has light REEs such as praseodymium, neodymium, and samarium. The researchers employed an ion exchange method using the AN-31 anion exchanger to extract REEs from sulfate solutions. Experiments were conducted under static conditions with a liquid-to-solid ratio of 1:1, a pH of 2, and a temperature of 298 K. Initial REE concentrations in the solutions varied from 0.83 to 226.31 mmol/kg. The study showed that under such conditions it was possible to recover 59.7% for praseodymium at pH 2 and 52.8% for samarium at pH 4. The ion exchange equilibrium constants were determined to be 1.84 for praseodymium, 1.66 for neodymium, and 2.32 for samarium, with corresponding Gibbs free energy changes of −1507.16, −1259.15, and −2082.96 J/mol, respectively. The total sorbent capacity reached 0.67 mol/kg for praseodymium, 0.68 mol/kg for neodymium, and 0.71 mol/kg for samarium. The study showed that the AN-31 anion exchanger effectively recovers a mixture of light REEs from sulfate solutions, showing an average ion exchange equilibrium constant of 1.94 and a total sorbent capacity of 0.6853 mol/kg [

82].

Another study examined the extraction and purification of rare earth elements (REEs) from phosphogypsum waste using a resin-in-leach (RIL) process followed by batch elusion. The researchers utilized Purolite S940 resin in a diluted sulfuric acid solution across multiple consecutive RIL cycles, achieving a maximum REE loading of 0.92 equiv./kg and a calcium-REE purity exceeding 70% after seven cycles. The loaded resin was later treated in a packed bed column with a two-step elution procedure: calcium was first removed using 0.06 M HCl, followed by REE elution with biodegradable chelating agents, including

N,N-dicarboxymethyl glutamic acid (GLDA) and methylglycinediacetic acid (MGDA). Results demonstrated that both MGDA and GLDA effectively eluted REEs, with MGDA yielding a high-purity REE fraction of up to 99.01%. The study concludes that the RIL process, combined with biodegradable chelating agents, offers a promising approach for REE recovery from phosphogypsum waste [

83].

Table 8 shows the operating conditions and leaching eff. of REEs using RIL process.

Resin in leach method is a unique technique for the simultaneous extraction and loading of REEs on either chelating of strong acidic cation resins. The idea is to integrate the two separate processes to reduce capital and operational costs while also reducing the requirement of very concentrated acid solutions. However, the process comes with various limitations such as High concentrations of calcium, iron, aluminum, and other metal ions compete with REEs for binding sites on the resin. On the other hand, Extraction efficiency varies widely depending on the origin and composition of PG (e.g., 15% to 80%). In addition, many resins require a narrow pH range or specific acid concentration to be effective (e.g., chelating resins work well at low H₂SO₄ concentrations but require strong eluents for desorption) while resins like Purolite S940 have moderate REE capacity and require multiple cycles for meaningful recovery. Nevertheless, most of the processes reported in literature have a very long contact time which is already not feasible for an industrial scale process, except one study from 2018 which showed 2 h contact time with a variable REEs leaching efficiency of 15-70 % while using Purolite C160 and 10-20 g/l sulfuric acid solution with a Resin/PG/Acid ratio of 4:30:4.

In general, chelating resins (e.g., Purolite S940 or similar) prove the best selectivity and REE loading performance, particularly under optimized RIL conditions and low acid concentrations. However, their effectiveness is offset by complex elution requirements and the need for multiple processing cycles. For practical and scalable extraction, macroporous SAC resins (with DVB >12%) offer a compromise between efficiency and industrial applicability, though their selectivity is lower.

Table 9 shows the type of resins with their advantages and limitations in terms of REEs extraction.