1. Introduction

Bread wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) stands as one of the most important staple crops globally, serving as the principal source of food for over 2.5 billion people. Its adaptability to a wide range of agro-ecological zones, ease of processing, and extended shelf life make it a preferred cereal in many parts of the world. According to the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), wheat contributes approximately 20% of the global dietary energy and protein intake, underscoring its central role in human nutrition and food security (FAO, 2023). Its high yield potential and extensive consumption make it a strategic crop in addressing hunger and undernutrition in both developed and developing nations.

However, the heavy dependence on bread wheat as a staple food presents nutritional limitations, particularly concerning micronutrient content. Traditional wheat varieties are typically low in essential micronutrients such as iron, zinc, and vitamin A, which are vital for growth, immunity, and cognitive development. This has led to the recognition of "hidden hunger" in populations with wheat-dominant diets where caloric intake may be sufficient, but micronutrient intake remains inadequate (Bouis & Saltzman, 2022). In regions such as South Asia and North Africa, where wheat constitutes a major portion of the daily caloric intake, deficiencies in iron and zinc are widespread, contributing to anemia and impaired immune function.

Moreover, the increasing reliance on refined wheat products, which undergo processing that removes nutrient-dense bran and germ layers, exacerbates concerns about dietary diversity and quality. Processed wheat-based foods, though convenient, often lack dietary fiber, B vitamins, and phytochemicals present in whole grains. This dietary pattern has been associated with rising incidences of non-communicable diseases such as type 2 diabetes, obesity, and cardiovascular disorders (Shewry & Hey, 2015; Mohan et al., 2021). Thus, while wheat secures calorie sufficiency, its nutritional profile requires enhancement to meet the broader spectrum of dietary needs.

To address these concerns, ongoing efforts in wheat biofortification, genetic improvement, and diversification of diets are gaining momentum. Biofortified wheat varieties enriched with iron and zinc have shown promise in field trials and nutritional studies, particularly in Ethiopia, India, and Pakistan (Velu et al., 2022). Simultaneously, policy interventions promoting dietary diversification through the inclusion of legumes, fruits, vegetables, and other cereals—are crucial for reducing overdependence on wheat and improving overall nutritional outcomes. These integrated strategies are essential for achieving sustainable food and nutrition security in wheat-reliant populations.

2. Global and Regional Consumption Patterns

Global and regional consumption patterns of bread wheat vary significantly based on dietary habits, agricultural capacity, and socioeconomic factors. Globally, wheat is the second most consumed cereal after rice, with per capita consumption exceeding 70 kg/year in many countries (FAO, 2023). In regions such as Europe, Central Asia, and North Africa, wheat consumption often surpasses 100 kg per person annually, forming the cornerstone of daily diets through products like bread, pasta, and couscous. In contrast, Sub-Saharan Africa and parts of East Asia traditionally relied more on alternative staples such as maize, rice, and sorghum, though wheat consumption is rising rapidly due to urbanization and changing food preferences (Tadesse et al., 2022). In Ethiopia, for example, wheat consumption has grown markedly in urban areas, driven by increased demand for processed and baked foods (Abate et al., 2021). This shift in consumption patterns underscores the growing importance of wheat in food security planning across diverse regions, necessitating attention to both production and nutritional quality.

Table 1.

Per Capita Wheat Consumption by Region (2020–2025) (kg/person/year).

Table 1.

Per Capita Wheat Consumption by Region (2020–2025) (kg/person/year).

| No |

Region |

2020 Estimate |

2023 Estimate |

2025 Projection |

Key Notes |

References |

| 1 |

North Africa |

180 |

185 |

190 |

Highest global consumption; wheat is staple food |

FAO (2023); Bouis & Saltzman (2022) |

| 2 |

Europe |

100 |

102 |

105 |

Stable consumption; dominant in bread and pasta |

FAO (2023) |

| 3 |

Central Asia |

120 |

125 |

128 |

High intake due to traditional bread-based diet |

Shewry & Hey (2015) |

| 4 |

South Asia (e.g., India, Pakistan) |

60–75 |

70–80 |

75–85 |

Increasing trend; wheat replacing rice in urban diets |

Velu et al. (2022); Mohan et al. (2021) |

| 5 |

Sub-Saharan Africa |

25–35 |

30–40 |

35–45 |

Growing due to urbanization and import dependency |

Tadesse et al. (2022); Abate et al. (2021) |

| 6 |

East Asia (e.g., China) |

60 |

62 |

65 |

Moderate growth; more noodles and wheat-based products |

FAO (2023) |

| 7 |

Latin America |

60 |

62 |

65 |

Stable consumption; wheat used in processed foods |

FAO (2023) |

| 8 |

Global Average |

~70 |

~72 |

~75 |

Reflects gradual growth across developing countries |

FAO (2023) |

In Ethiopia, wheat is the third most consumed cereal after teff and maize, with its demand steadily increasing, especially in urban areas. This shift is largely driven by rapid urbanization, income growth, and changing dietary preferences favoring convenient, wheat-based processed foods like bread and pasta. As a result, per capita wheat consumption in Ethiopia has risen significantly over the past decade. While traditionally grown in highland regions, the country has expanded wheat cultivation into lowland areas to meet rising demand. Despite increased domestic production, Ethiopia remains a major wheat importer. This trend highlights the crop’s growing role in food security and market integration (Tadesse et al., 2022; Abate et al., 2021; FAO, 2023)..

3. Nutritional Contribution of Bread Wheat

Bread wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) is a significant source of calories and plant-based protein, contributing approximately 20% of global human energy and protein intake (FAO, 2023). It provides complex carbohydrates, primarily in the form of starch, which serve as a vital energy source for billions of people. Wheat also offers dietary fiber, particularly when consumed as whole grain, which supports digestive health and helps regulate blood glucose levels (Shewry & Hey, 2015). Additionally, wheat contains essential micronutrients such as B vitamins (thiamine, niacin, folate), iron, magnesium, and zinc, though the levels of these micronutrients vary significantly depending on the variety and degree of processing.

Despite its macronutrient value, bread wheat’s contribution to micronutrient sufficiency is limited, particularly when consumed in refined forms. Milling processes often remove the bran and germ parts rich in vitamins, minerals, and phytochemicals leaving behind mostly endosperm, which is lower in nutrient density. This nutritional gap is a concern in populations that rely heavily on wheat as a staple, leading to increased risk of deficiencies, especially in iron and zinc (Bouis & Saltzman, 2022). Such deficiencies contribute to widespread public health issues including anemia, stunted growth, and impaired cognitive development, particularly among children and women in low-income regions.

To address these challenges, biofortification strategies have been implemented to develop wheat varieties with enhanced micronutrient profiles. Research efforts led by institutions like CIMMYT and HarvestPlus have resulted in high-zinc and high-iron wheat cultivars now being grown in countries like Ethiopia, India, and Pakistan. These biofortified varieties have demonstrated improved nutritional outcomes in target populations (Velu et al., 2022). Furthermore, promoting whole grain wheat consumption can significantly improve fiber and micronutrient intake, contributing to the prevention of non-communicable diseases and better overall health outcomes.

In summary, while bread wheat is indispensable for global food security and energy supply, its nutritional contribution can be substantially enhanced through dietary diversification, promotion of whole grain consumption, and biofortification initiatives. Such measures are crucial for leveraging wheat’s potential to combat both calorie and micronutrient deficiencies.

Table 2.

Nutritional Composition of Whole Wheat Flour (per 100g).

Table 2.

Nutritional Composition of Whole Wheat Flour (per 100g).

| No |

Nutrient |

Average Content |

Health Implication |

Reference |

| 1 |

Energy |

340 kcal |

Provides dietary energy from complex carbohydrates |

USDA, 2023 |

| 2 |

Carbohydrates |

72.5 g |

Main energy source; includes dietary fiber |

Shewry & Hey, 2015 |

| 3 |

Dietary Fiber |

12.2 g |

Supports digestive health; reduces risk of chronic diseases |

Slavin, 2003 |

| 4 |

Protein |

13.2 g |

Builds and repairs body tissues; essential amino acids |

FAO, 2023 |

| 5 |

Fat |

2.5 g |

Mostly unsaturated fats; contributes to satiety |

USDA, 2023 |

| 6 |

Iron |

3.9 mg |

Supports oxygen transport; deficiency causes anemia |

Velu et al., 2022 |

| 7 |

Zinc |

2.8 mg |

Essential for immunity and cell function |

Bouis & Saltzman, 2022 |

| 8 |

Magnesium |

138 mg |

Regulates muscle and nerve function |

Shewry & Hey, 2015 |

| 9 |

B Vitamins (esp. B1, B3, B6, Folate) |

Varied (e.g., B1: 0.4 mg) |

Important for energy metabolism and red blood cell production |

FAO, 2023 |

Bread wheat is rich in carbohydrates and provides moderate protein. However, its lysine content is limited, making it a poor-quality protein when consumed alone.

4. Nutritional Challenges and Fortification

While bread wheat is a key source of energy and protein, its nutritional quality is limited by certain inherent factors. One of the primary challenges is the presence of phytates (phytic acid) in the bran layer, which bind essential minerals such as iron and zinc, significantly reducing their bioavailability (Hurrell & Egli, 2010). This is particularly concerning in populations with monotonous wheat-based diets, where alternative sources of these micronutrients are limited. Additionally, the widespread consumption of refined wheat flour exacerbates nutritional deficiencies, as the milling process removes the nutrient-rich bran and germ, leading to lower levels of dietary fiber, vitamins (such as B1, B6, and folate), and trace elements (Shewry & Hey, 2015).

To address these shortcomings, several interventions have been adopted globally. Biofortification, which involves breeding wheat varieties with higher concentrations of bioavailable zinc and iron, has shown promising results in improving micronutrient intake in target populations, including in Ethiopia, India, and Pakistan (Velu et al., 2022). Moreover, flour fortification with iron, folic acid, and other nutrients is widely implemented in over 80 countries and is endorsed by the World Health Organization as an effective public health strategy (WHO, 2021). Complementary dietary practices, such as combining wheat-based meals with legumes, fruits, or vegetables rich in vitamin C, can further enhance mineral absorption. Together, these strategies play a critical role in mitigating the hidden hunger associated with wheat consumption and in promoting better nutritional outcomes, especially in vulnerable populations.

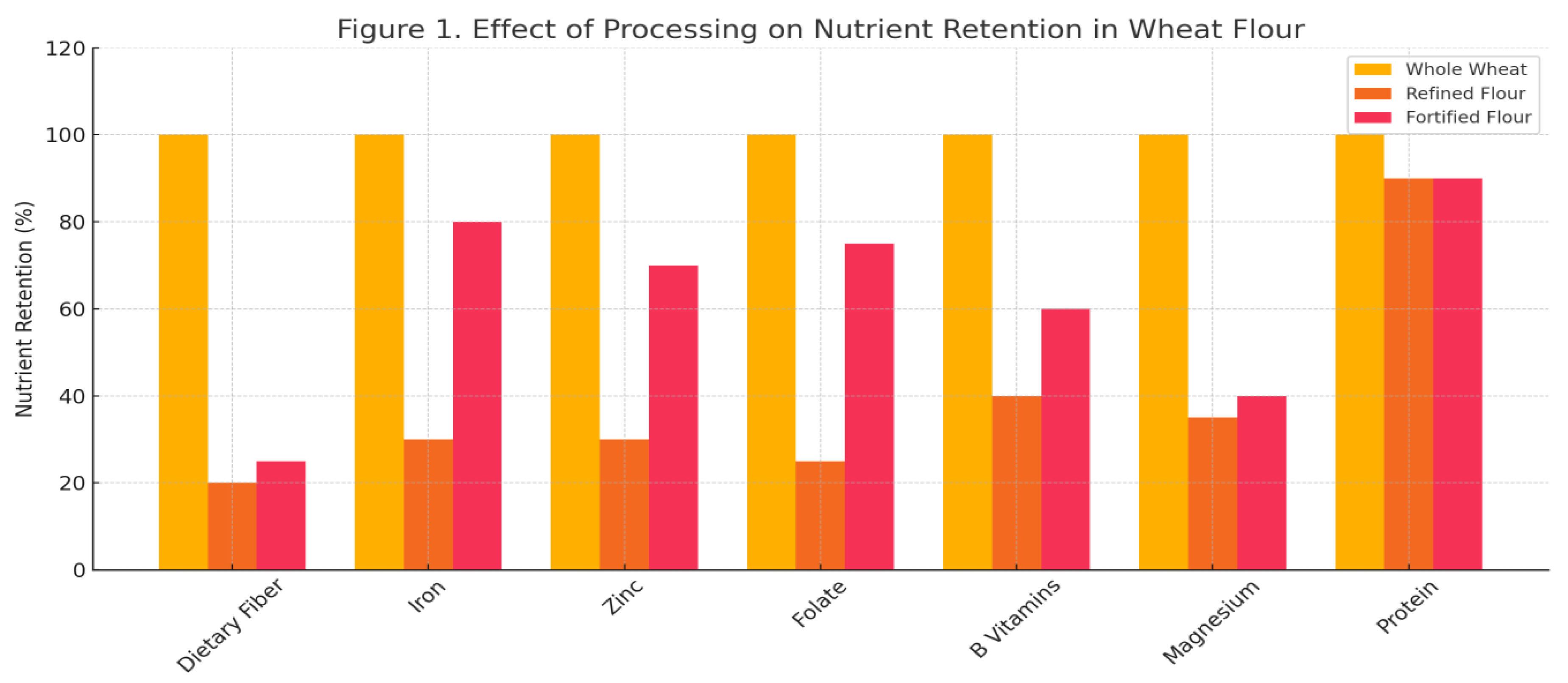

Figure 1.

Effect of Processing on Nutrient Retention in Wheat Flour.

Figure 1.

Effect of Processing on Nutrient Retention in Wheat Flour.

The graph illustrates the significant nutrient losses in refined flour and the partial restoration achieved through fortification highlighting the importance of both whole grain consumption and targeted nutrient enhancement strategies.

5. Policy Implications

In the Ethiopian context, promoting nutrition-sensitive agriculture is crucial to address both macro- and micronutrient deficiencies associated with wheat-based diets.

-

1)

Nutrition-Sensitive Agriculture: Support research and scale up the adoption of biofortified wheat varieties rich in iron and zinc, which have already shown positive impacts in pilot regions (Velu et al., 2022).

-

2)

Fortification Policies: Implement mandatory wheat flour fortification with key micronutrients such as iron and folic acid, which could significantly reduce anemia and neural tube defects, as evidenced in other low- and middle-income countries (WHO, 2021).

-

3)

Diet Diversification Programs:Strengthen initiatives like school feeding and the Productive Safety Net Program (PSNP) by incorporating a balanced mix of cereals and legumes to improve overall dietary quality and mineral absorption.

-

4)

Trade and Import Policy: Align trade and wheat import strategies with nutrition goals by prioritizing the import of fortified or higher-quality wheat while maintaining affordability and food security for vulnerable populations (Tadesse et al., 2022).

These integrated strategies can improve the nutritional impact of wheat while supporting long-term public health and development goals.

6. Challenges and Future Directions

∙ Limited Public Awareness of Whole vs. Refined Wheat:

Many consumers lack understanding of the nutritional differences between whole wheat and refined wheat products. This gap affects dietary choices and ultimately public health outcomes, as whole wheat provides higher fiber, vitamins, and minerals that are often lost during refining.

∙ Need for Investment in Biofortification and Local Seed Systems:

Enhancing the nutritional quality of wheat through biofortification breeding varieties rich in essential micronutrients like iron and zinc is critical. Coupled with strengthening local seed systems, these efforts can improve seed accessibility, farmer adoption, and sustainability of nutrient-rich wheat cultivation.

∙ Strengthening Inter-Sectoral Collaboration Between Agriculture, Health, and Education Sectors:

Effective promotion of biofortified wheat and whole grain consumption requires coordinated strategies involving agricultural extension, public health messaging, and nutrition education in schools. This integrated approach can accelerate awareness, acceptance, and improved nutrition outcomes at community and national levels.

7. Conclusion

Bread wheat plays a crucial role in global food security; however, its natural micronutrient content is limited. Targeted strategies including biofortification through breeding, flour fortification, and supportive policy frameworks are essential to enhance its nutritional value and effectively combat malnutrition, particularly in resource-limited regions.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The author declares that there is no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this paper.

Acknowledgments

The author acknowledges the contributions of researchers and institutions whose work on wheat nutrition, biofortification, and food policy significantly informed this review. Appreciation is also extended to international organizations for providing statistical and policy data, and to digital tools and Google Scholar for assistance in drafting and literature access.

References

- Abate, T., Tadesse, T., & Teklewold, H. (2021). Urban demand for wheat and processed foods in Ethiopia: Trends and implications. Journal of Food Security, 9(2), 110-123.

- Bouis, H. E., & Saltzman, A. (2022). Improving nutrition through biofortification: A review of evidence from HarvestPlus. Food Policy, 102, 102154. [CrossRef]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). (2023). FAOSTAT statistical database. http://www.fao.org/faostat/en/.

- Hurrell, R., & Egli, I. (2010). Iron bioavailability and dietary reference values. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 91(5), 1461S–1467S. [CrossRef]

- Mohan, V., Gokulakrishnan, K., Deepa, M., & Rema, M. (2021). Dietary patterns and non-communicable diseases: The role of whole grains. Nutrition Reviews, 79(7), 713-725. [CrossRef]

- Shewry, P. R., & Hey, S. J. (2015). The contribution of wheat to human diet and health. Food and Energy Security, 4(3), 178–202. [CrossRef]

- Slavin, J. (2003). Why whole grains are protective: Biological mechanisms. Proceedings of the Nutrition Society, 62(1), 129-134. [CrossRef]

- Tadesse, T., Abate, T., & Getachew, A. (2022). Wheat consumption trends and implications for food security in Ethiopia. African Journal of Agricultural Research, 17(4), 561-571. [CrossRef]

- Velu, G., Ortiz-Monasterio, I., Cakmak, I., & Hao, Y. (2022). Biofortified wheat: Progress and challenges. Plant Breeding Reviews, 46, 147-178. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO). (2021). Fortification of wheat flour with iron and folic acid: A global overview. WHO/NMH/NHD/21.5. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/345785.

- United States Department of Agriculture (USDA). (2023). FoodData Central. https://fdc.nal.usda.gov/.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).