1. Introduction

Osteoporosis is one of the most-common diseases nowadays. It is characterized by gradually-decreased bone density and compromised bone strength leading to bone fragility and fractures [

1].

Osteoporosis is associated with postmenopausal estrogen deficiency [

2], since the estrogen deficiency leads to increase in bone remodeling with an imbalance between bone formation and resorption [

3,

4]. Normal bone continuously requires bone remodeling in which osteoclasts and osteoblasts are coordinating well to regulate the remodeling process. The previous studies demonstrated that bone remodeling process is damaged by estrogen deficiency due to the presence of estrogen receptors in osteoclasts. A bone resorption by osteoclasts increases while the bone formation by osteoblasts decreases [

5,

6,

7].

At present, bisphosphonates are commonly used as inhibitors of bone resorption which is majority in the osteoclasts’ metabolism for osteoporosis [

8,

9,

10,

11]. Bisphosphate compounds include alendronate, risedronate, iBandronate, zoledronate, etidronate, pamidronate, etc. Although widely prescribed, bisphosphonates have serious side-effects such as nausea, gastric ulcer, and jaw osteonecrosis [

9]. Therefore, it is required to develop a novel therapeutic without adverse-effects, and cell-based therapeutic approaches should fulfil this requirement.

As a regenerative medicine for bone repair, stem cell therapies of osteoporosis have been increasingly attempted. Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) have the ability to differentiate into osteocytes, chondrocytes, and adipocytes [

12]. Due to the potential of MSCs for osteocytic differentiation, they can be used for replacement therapy of destroyed bone tissue and osteoporosis. Otherwise, MSCs express and secrete numerous functional molecules including cytokines, chemokines, growth factors (GFs), and neurotrophic factors (NFs) which are involved in the paracrine effects of MSCs. Among them, GFs and NFs were found out to be major mediators of tissue-regenerating paracrine effects. Indeed, MSCs release various GFs and NFs that are taken up by damaged tissues or cells. The GFs and NFs inhibit cell apoptosis as well as inflammatory tissue injury, facilitate cell proliferation, and thereby promotes osteogenesis [

13,

14]. Notably, recent studies demonstrated that hypoxia-preconditioned MSCs intensify paracrine signaling [

15,

16].

Notably, it has been reported that functional molecules such as GFs and NFs are released in a form of extracellular vesicles (EVs) from functional cells, and exosomes are one of the EVs with a size of 50–300 nm [

17]. Exosomes, as nano-lipid vesicles containing functional molecules, can easily penetrate bodily membrane barriers, so deliver the functional proteins to target cells. However, due to very-low yield, low purity, and difficulty in isolation, exosomes has been limited in clinical application [

18].

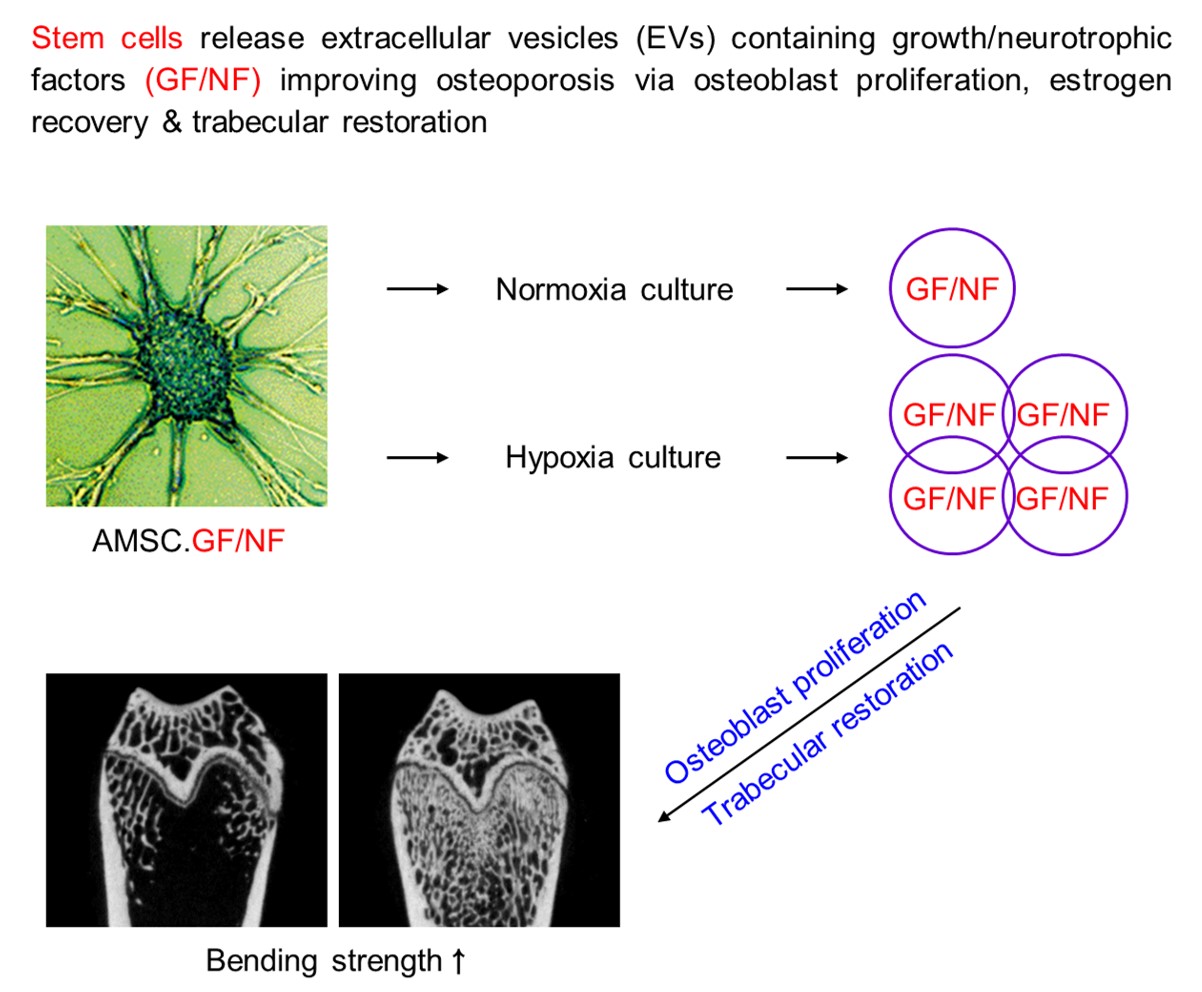

Recently, we attained large amounts of EVs via a hypoxic (2% O2) culture of human amniotic membrane mesenchymal stem cells (AMSCs). The EVs were confirmed to be 70–80 nm in diameter and contain high concentrations of GFs and NFs [

19,

20].

The present study was aimed to verify the effects of EVs containing high concentrations of GFs and NFs, in comparison with zoledronic acid (a reference control), in promoting bone regeneration and in inhibiting bone resorption in ovariectomy (OVX)-induced osteoporosis conditions, and thereby to provide a possibility of the EVs as a candidate for osteoporosis treatment.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preparation of AMSCs

Human amniotic membrane tissues were obtained through Caesarean section from a healthy pregnant female donor. The amniotic membrane tissues were digested with collagenase I, neutralized with an equal volume of medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Biowest, Kansas City, MO, USA), and centrifuged at 1,500 rpm for 10 min. After washing twice, the contaminated red blood cells (RBCs) were lysed with RBC lysis buffer, and the remaining cells were suspended in Keratinocyte serum-free medium (SFM; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) supplemented with 5% FBS, 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 mg/mL streptomycin (Invitrogen) [

19,

20]. Cultures were maintained under 5% CO

2 at 37 °C in culture flask. Media were changed every 2–3 days.

The prepared amniotic stem cells were analyzed for their stem cell markers in a flow cytometric system. The AMSCs were confirmed to be mesenchymal stem cells (data not shown).

2.2. Preparation of EVs

The separated AMSCs were suspended in the defined serum-free medium in Hyper flask (Nunc, Rochester, NY, USA) and cultivated under normal oxygen (20% O

2, 5% CO

2) or hypoxic oxygen (2% O

2, 5% CO

2) tensions at 37°C for 3 days [

19,

20]. The media were filtered through a bottle-top vacuum filter system (0.22 μm, PES membrane) (Corning, Glendale, CA, USA). The conditioned media were 30-fold concentrated using Vivaflow-200 (Sartorius, Hannover, Germany).

2.3. Osteoblast Culture

Murine osteoblastic MC3T3-E1 cells were purchased from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA). Cells were cultivated in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM; Biowest) supplemented with 10% FBS, 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 mg/mL streptomycin [

21,

22]. The cultures were maintained under 5% CO

2 at 37°C in a culture flask. Media were changed every 2 – 3 days, and all experiments were conducted using the cells within the first 5 passages.

2.4. Osteoblast-Proliferative Activity

In order to assess the cell-proliferating activity of EVs, MC3T3-E1 cells (5 x 10

4/mL) were seeded in a 96-well plate. The cells were treated with various concentrations (1 x 10

5–1 x 10

7 particles/mL) of EVs. After 24-hour culture in a normoxic condition (20% O

2) at 37°C, the cell number was counted [

19].

2.5. Osteoblast-Protective Activity

To evaluate the cytoprotective activity of EVs against oxidative stress, MC3T3-E1 cells (5 × 10

4/mL) were seeded in a 96-well plate. The cells were exposed to 200 μM H

2O

2 and treated with EVs (1 x 10

5–1 x 10

7 particles/mL) [

19]. Following 24-hour culture in a normoxic condition (20% O

2) at 37°C, the cell number was counted.

To assess the cytoprotective activity of EVs against hypoxic injury, MC3T3-E1 cells (5 x 10

4/mL) were seeded in a 96-well plate. The cells were treated with various concentrations (1 x 10

5–1 x 10

7 particles/mL) of EVs. After 24-hour culture in normoxic (20% O

2) or hypoxic (2% O

2) conditions at 37°C, the cell number was counted [

19].

2.6. Design of Animal Experiment

Ten-week-old female Sprague-Dawley rats were purchased from DBL (Eumseong, Korea). The animals were subjected to either bilateral ovariectomy or Sham operation without removing the ovaries described previously [

23,

24]. All rats were assigned to 6 groups at 8 weeks post-surgery.

Ovariectomized rats were intravenously injected with EVs (1 x 108, 3 x 108 or 1 x 109 particles/rat), zoledronic acid (ZA; 100 μg/kg; a reference control) or their vehicle (phosphate-buffered saline; 100 μL/rat) once a week for 8 weeks.

Rats were sacrificed 1 week after the final EV administration. Serum and femurs from each rat were harvested, and then the serum and bone parameters related to bone remodeling were analyzed.

2.7. Analysis of Serum Markers

2.7.1. Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) Analysis of 17β-Estradiol

The level of 17β-estradiol in serum was measured using ELISA kits (Arigo Biolaboratories, Hsinchu, Taiwan) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

2.7.2. Biochemistry Analysis of Alkaline Phosphatase (ALP) and Calcium

The levels of ALP and calcium in serum were analyzed using an automatic biochemistry analyzer (Hitachi 7180, Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan) according to the manufacturer’s instructions, respectively.

2.8. Analysis of Bone Parameters

2.8.1. X-Ray Analysis of Bone Minerals

A dual-energy X-ray (PIXImus, Lunar, Madison, WI, USA) was used to measure bone mineral density (BMD; mg/cm2) and bone mineral content (BMC; mg) of the femurs. The rats were lightly anesthetized with diethyl ether, ventrally positioned on a DEXA table, and scanned according to manufacturer’s procedures.

2.8.2. Biomechanical Measurement of Three-Point Bending Strength

The bending strength of the femurs was measured via a three-point bending test. The test was carried out using Universal Material Testing Machine (Instron 4411, Instron, MA, USA). The cross-head speed was set at 5 mm/min until fracture. The load-time curve was converted into a load-displacement curve, and then failure load was determined as a maximum bending strength at fracture in the load-displacement curve. The sample was set according to a literature [47].

2.8.3. Micro-Computed Tomographic (CT) Analysis of Bone Structure

Micro-CT images of the femurs of rats were obtained using Quantum FX Micro-CT (Perkin-Elmer, Waltham, MA, USA), and reconstructed by scanner software (Quantum FX Micro-CT Control Software, Perkin-Elemer) [

25,

26]. Test conditions were set to a voltage of 90 kVp, current of 160 μA, and isotropic voxel size of 20 μm per pixel.

For the evaluation of bone regeneration, the histomorphometric parameters of bone were determined in the region of interest: i.e., bone volume/tissue volume (BV/TV) ratio (%), trabecular thickness (Tb.Th; mm), trabeculsr number (Tb.N; (1/mm), and trabeculsr space (Tb.Sp; mm).

2.9. Statistical Analysis

The data were described as mean ± standard error. Statistical significance between the groups was analyzed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) using the SPSS statistical software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). P-values of less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Osteoblast-Proliferative and -Protective Activities of EVs

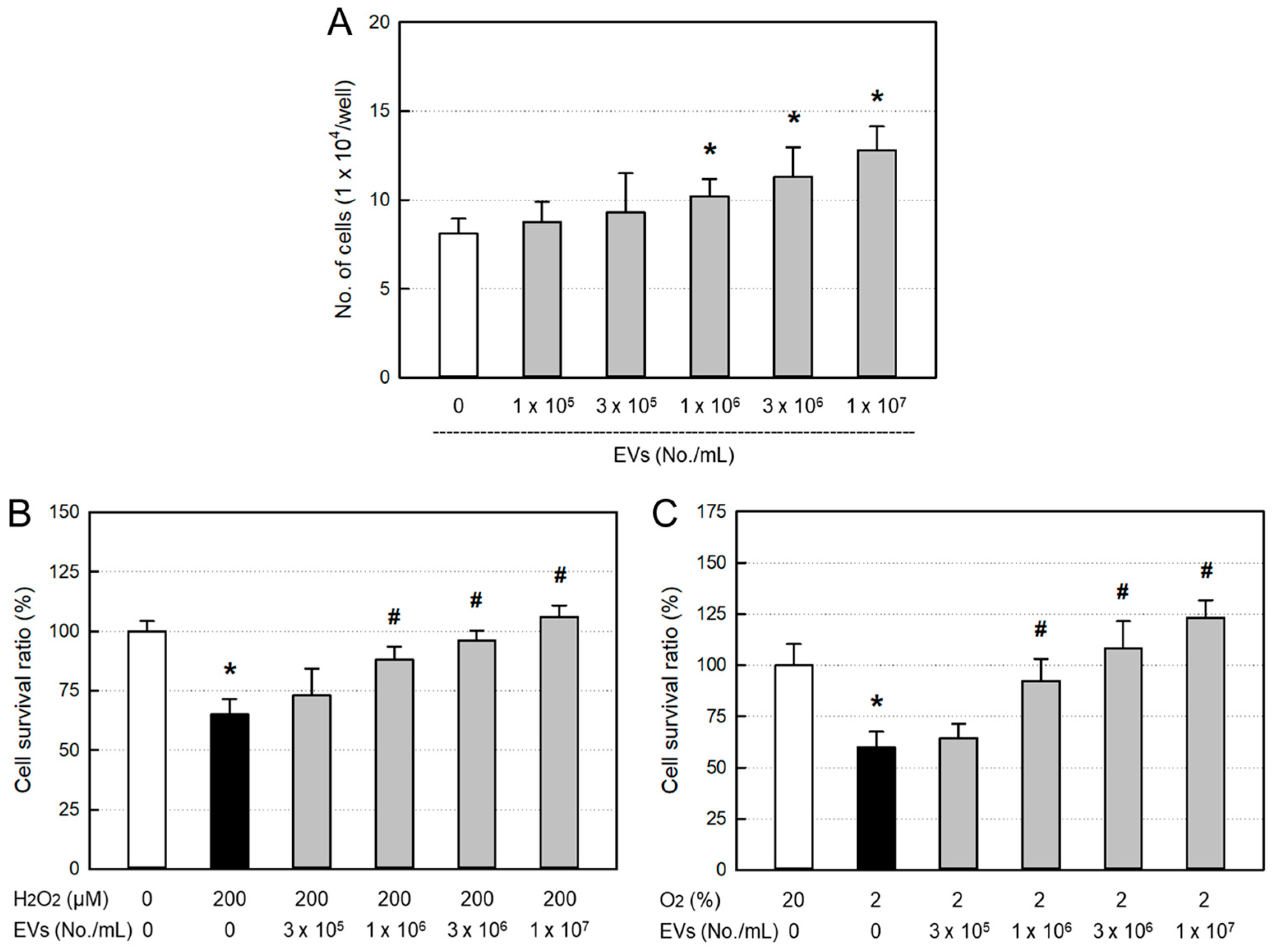

Treatment of EVs (≥ 1 x 10

6 particles/mL) significantly facilitated the proliferation of osteoblastic MC3T3-E1 cells in a concentration-dependent manner (

Figure 1A). Furthermore, EVs significantly protected against 200 μM H

2O

2 (

Figure 1B) and 2% hypoxic (

Figure 1C) insults from the concentration of 1 x 10

6 particles/mL.

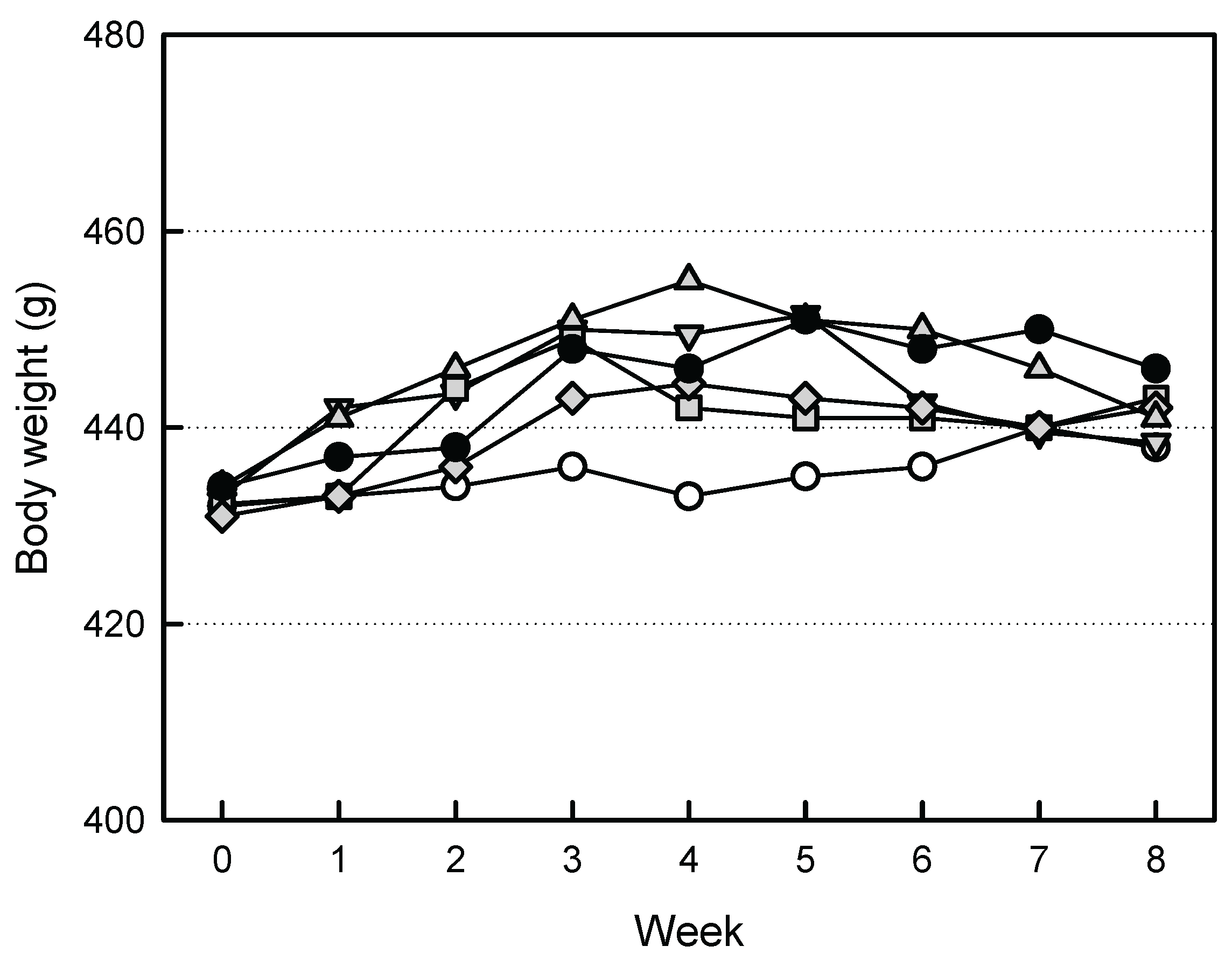

3.2. Effects of EVs on the Body Weights

The body weights of ovariectomized rats tended to increase, compared to Sham group animals (

Figure 2). However, increased body weights were somewhat attenuated by treatment of the high-dose EVs (1 x 10

9 particles/rat). Similarly, such body weight-decreasing effect was also observed in ZA (100 μg/kg)-treated animals.

3.3. Effects of EVs on the Organ Weights

After ovariectomy, in addition to body weights, liver and kidney weights tended to increase (

Table 1). In contrast, spleen weight decreased following ovariectomy. Such changes in the weights of liver, kidneys, and spleen were somewhat recovered by treatment with EVs or ZA.

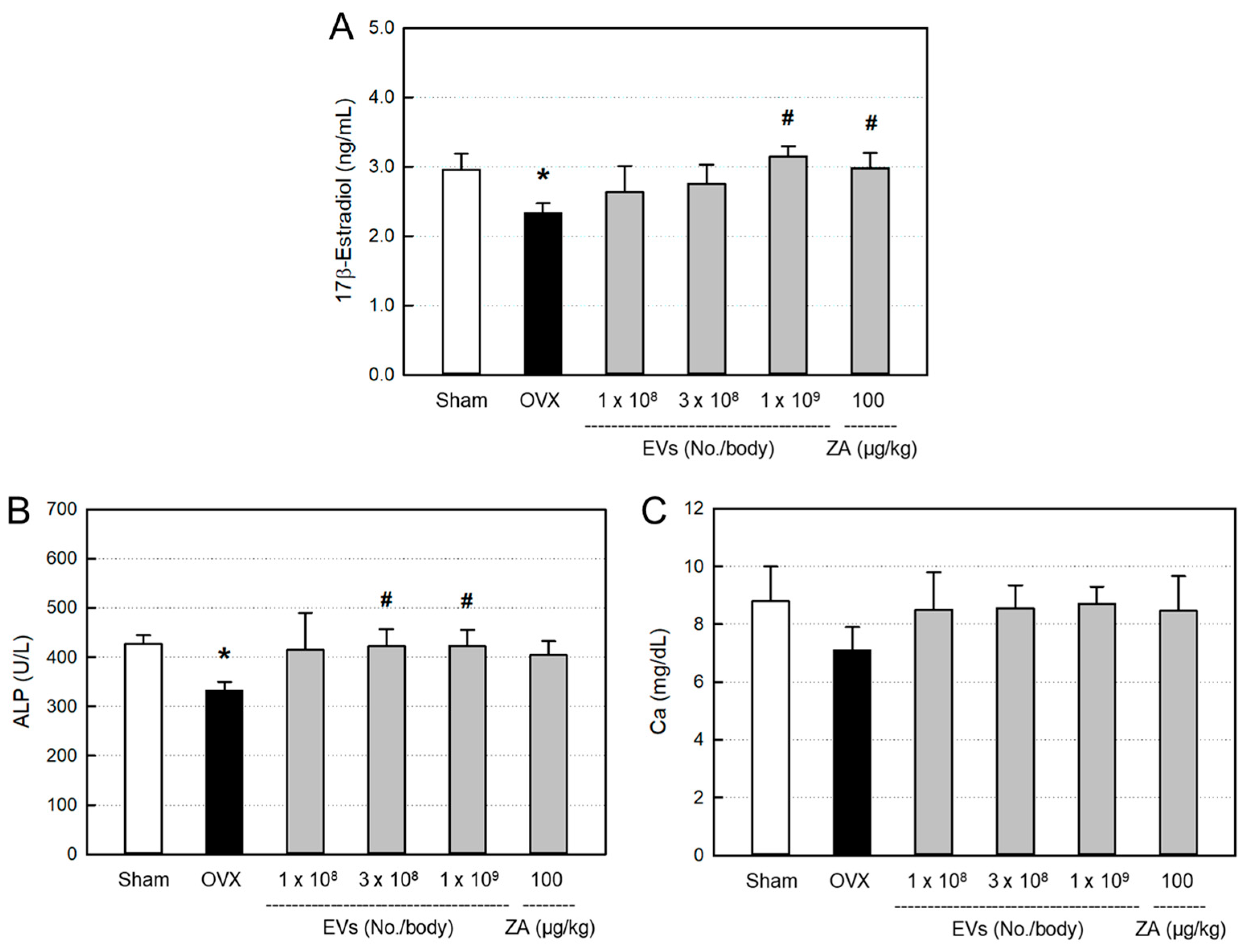

3.4. Effects of EVs on Serum Markers

The blood levels of bone-differentiation markers, including 17β-estradiol (

Figure 3A), ALP (

Figure 3B), and calcium (

Figure 3C), decreased following ovariectomy, compared with Sham control. All the serum 17β-estradiol, ALP, and calcium were recovered by treatment with EVs, showing near-full recovery in the high-dose (1 x 10

9 particles/body) group, although there were different responses among parameters. Such effects were also obtained by treatment with ZA (100 μg/kg).

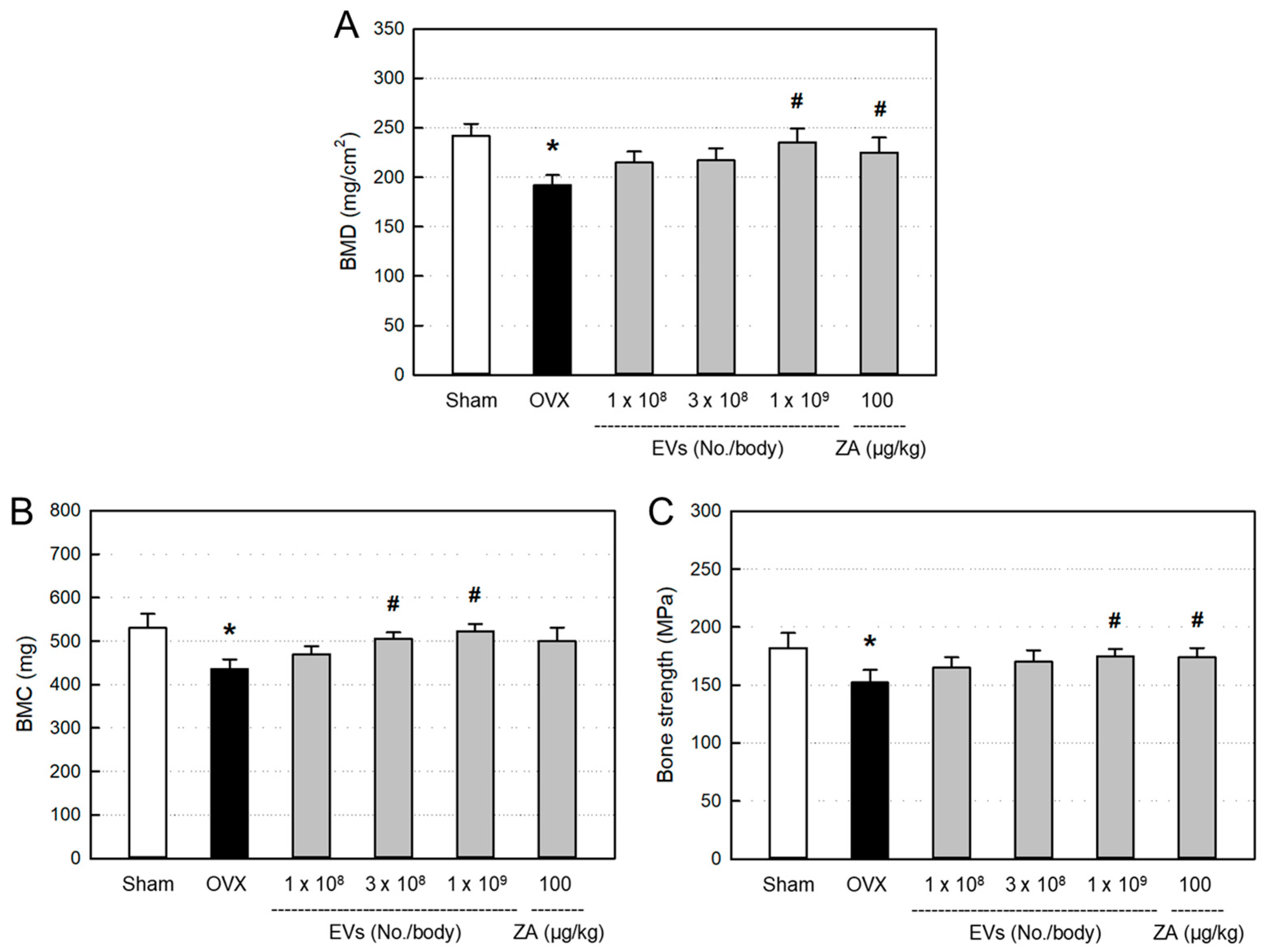

3.5. Effects of EVs on Bone Minerals and Strength

BMD (

Figure 4A) and BMC (

Figure 4B) significantly decreased in ovariectomized rats, compared to Sham control. However, the decreased BMD and BMC were restored by treatment with EVs, in which the high dose of EVs (1 x 10

9 particles/body) markedly recovered both the BMD and BMC levels. Such BMD- and BMC-recovering effects were also achieved with ZA (100 μg/kg).

Ovariectomy induced significant decrease in bending strength of the femurs, in comparison with Sham control (

Figure 4C). However, the reduced bone strength was recovered by treatment with EVs (1 x 10

9 particles/body). Similarly, ZA also significantly recovered the bending strength.

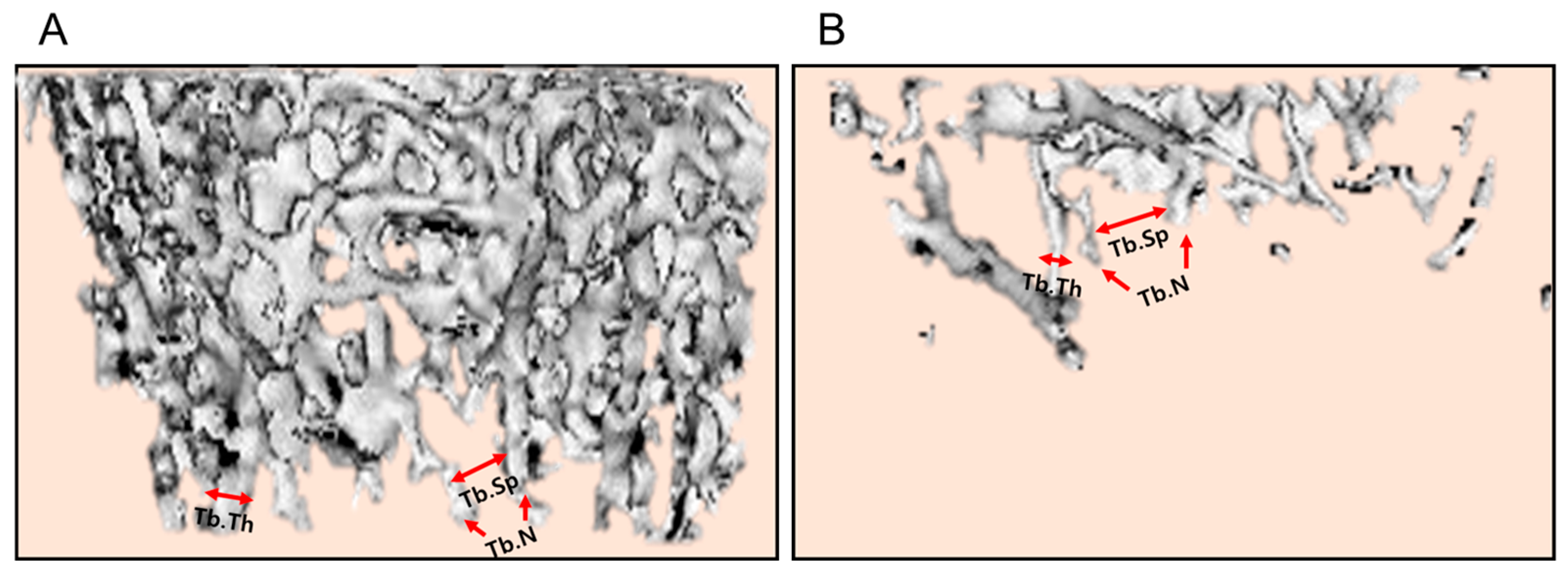

3.6. Effect of EVs on Bone Structure

In 3-dimensional images obtained by micro-CT showed severe loss of cancellous bones in ovariectomized rat femurs (

Figure 5, ★), compared to normal features in Sham control. The cancellous bone loss was attenuated by treatment with EVs in a dose-dependent manner (1 x 10

8–1 x 10

9 particles/body). Especially, a marked recovery was found in the high-dose group (arrows). Such a cancellous bone-recovering effect was also seen in the femurs of rats treated with ZA (100 μg/kg).

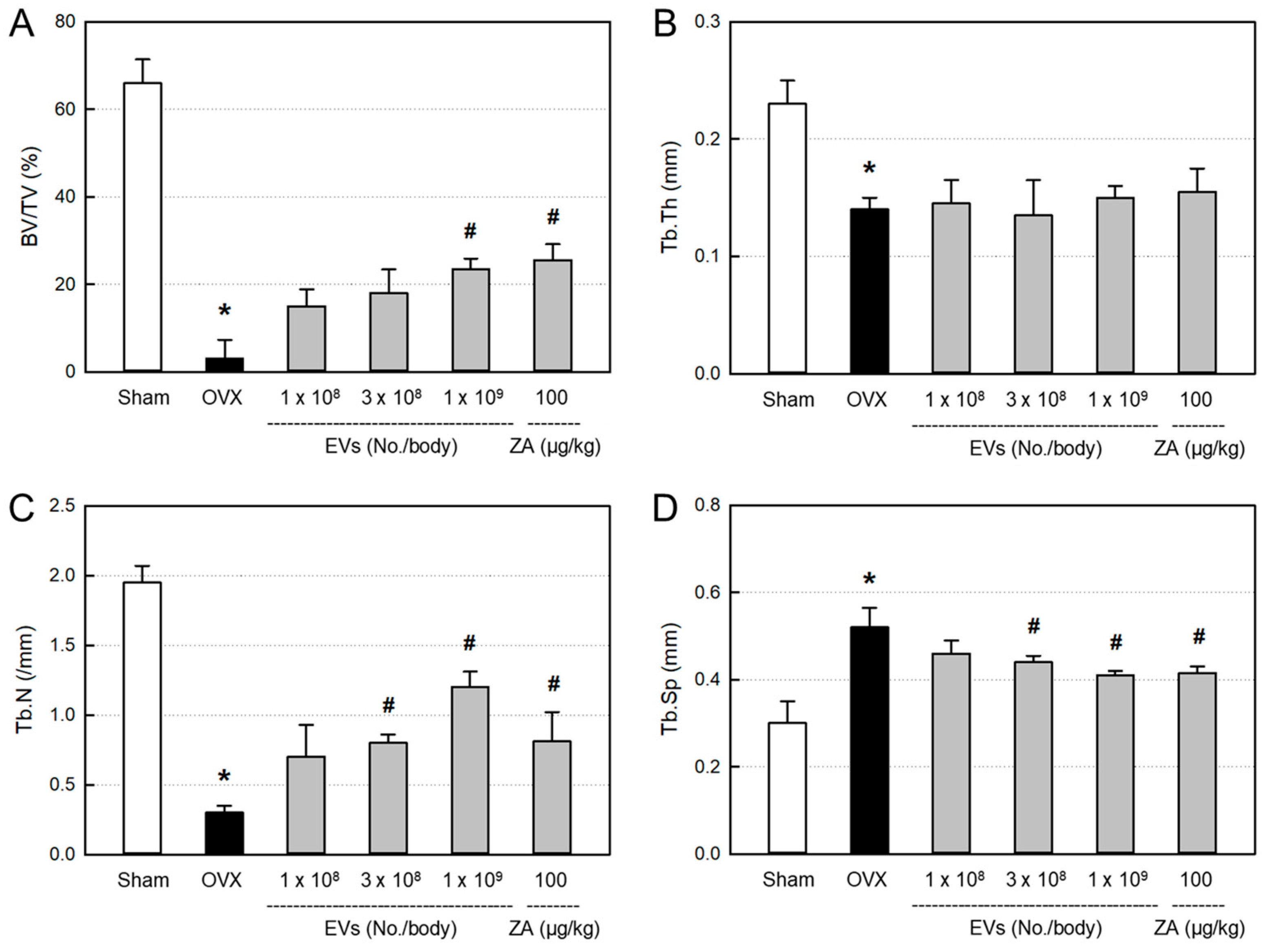

3.7. Effects of EVs on Bone Structural Parameters

In order to quantitatively analyze the bone structure, the values of BV/TV ratio, Tb.Th, Tb.N, and Tb.Sp of the femurs from the micro-CT images were measured. In comparison with the control bone (

Figure 6A), BV/TV, Tb.Th, and Tb.N markedly decreased in ovariectomized rat femurs (

Figure 6B).

The decreased BV/TV ratio in ovariectomixed animals was significantly recovered by EVs (1 x 10

9 particles/body) and ZA (100 μg/kg), although the effects were not statistically significant at lower doses of EVs (1 x 10

8–3 x 10

9 particles/body) (

Figure 7A). By comparison, Tb.N was markedly restored by treatment with EVs (3 x 10

8–1 x 10

9 particles/body) and ZA (

Figure 7C), while Tb.Th was not recovered by EVs or ZA (

Figure 7B). Tb.Sp significantly increased following ovariectomy, which was attenuated by treatment with EVs in a dose-dependent manner (

Figure 7D). Such Tb.Sp-recovering effect was also observed in the ZA-treated rat femurs.

4. Discussion

Osteoporosis is one of the most-common symptoms in postmenopausal women. Recently, stem cell-based therapy has been actively studied in tissue and bone regeneration [

27,

28,

29].

In the present study, we attained large amounts of EVs containing high concentrations of GFs and NFs from AMSCs via hypoxic culture (2% O

2), wherein much higher functional molecules than normoxic culture (20% O

2) were obtained [

19,

20].

Since various functional proteins such as GFs and NFs have been demonstrated to control osteoclast activation, osteocyte differentiation, and bone formation [

30], we treated ovariectomy-induced osteoporotic animals with various doses (1 x 10

8–1 x 10

9 particles/body) of EVs to confirm their beneficial effects.

Estrogen deficiency is one of the most-representative characteristics of menopausal women. Since the limited bone restoration due to estrogen deficiency results from decreased osteoblast proliferation [

5,

6,

7], we assessed the EVs’ activities on the MC3T3-E1 cell proliferation as well as protection against H

2O

2 and hypoxic insults. As expected from the high concentrations of GFs and NFs, EVs facilitated the osteoblast proliferation and protected against oxidative and hypoxic stresses (

Figure 1).

It is well known that the lack of estrogen level in serum leads to increased body weight gain [

31]. Also, the estrogen deficiency has been reported to damage some organs such as liver and kidneys [

32,

33,

34]. It has been reported that MSC-derived exosomes could stimulate the repair of tissues such as liver, kidneys, and bones [

35,

36,

37]. Our results were consistent with previous studies. Treatment with EVs gradually reduced the body weights increased by ovariectomy (

Figure 2). In addition, the increased relative weights of the liver and kidneys in ovariectomized rats were restored after EV treatment (

Table 1). Therefore, it is assumed that EVs not only reverse body weight gain, but also protect against liver and kidney damage following estrogen deficiency.

Serum markers are chosen to analyze metabolism related to bone resorption and formation. Previous studies investigated the decrease in serum level of estrogen after bilateral ovariectomy [

38,

39,

40]. In the present study, there were decreases in 17β-estradiol, ALP, and calcium levels, to some extent, in ovariectomized rats (

Figure 3). However, all the 3 parameters were recovered by treatment with EVs or ZA, in spite of different sensitivities. Previous studies have reported that estrogen can also be synthesized by some tissues, other than ovaries, especially, adipose tissues [

41,

42,

43]. Therefore, it is believed that EVs and ZA may stimulate alternative tissues to produce estrogen in ovariectomized rats, and thereby positively affect the bone restoration.

BMD is well known as a primary parameter for clinical diagnosis of osteoporosis. Some studies have reported marked decrease in the values of BMD and BMC in 8 weeks after ovariectomy [

44,

45]. In the present study, both the BMD and MBC significantly decreased 8 weeks after ovariectomy. Therefore, we started treatment with EVs to the ovariectomized rats at 8 weeks post-surgery. Most importantly, EV treatment improved bone mineral parameters to the levels of Sham control, which was superior to ZA (100 μg/kg) at a high dose (1 x 10

9 particles/body) (

Figure 4A,B).

In parallel with the decreased bone minerals, bending strength of the bone significantly decreased in ovariectomized rats. Notably, EVs remarkably restored the bone strength in ovariectomized rats, as seen in ZA-treated animals (

Figure 4C). The results indicate that EVs and ZA restore mechanical properties of the bones.

From the effects of EVs on BMD, BMC, and bending strength, we observed the inner integrity of femurs using micro-CT images. As expected, EV treatment inhibited bone loss in ovariectomized rats (

Figure 5). This result can be considered to be similar to the effect of ZA. ZA is known to block bone resorption by inhibiting osteoclast proliferation and inducing the osteoclast apoptosis [

46,

47,

48]. Although underlying mechanisms of EVs should be further clarified, such effects may be due to the activities of GFs and NFs in EVs, enhancing bone formation via osteoblasts, and inhibiting bone resorption via osteoclasts.

The bone-protective activities of EVs and ZA were confirmed by analyzing histomorphometric parameters, in which BV/TV can verify the mass of cancellous bone, while Tb.Th, Tb.N, and Tb.Sp represent the morphological structure of trabecular bones. Ovariectomy significantly decreased the BV/TV, Tb.Th, and Tb.N, and increased Tb.Sp. Notably, EVs and ZA increased Tb.N, that is, the number of bony trabecular, and thereby made the spaces between trabeculars (Tb.Sp) narrow and enhanced BV/TV ratio (

Figure 6).

5. Conclusions

In the present study, we demonstrated that EVs containing high concentrations of GFs and NFs improved ovariectomy-induced osteoporosis in rats. Actually, EVs increased blood estrogen level, ALP, BMD, BMC, and Tb.N, and thereby enhanced the bending strength. The results indicate that EVs can restore the bone soundness not only by directly inhibiting bone resorption and promoting bone regeneration, but also by indirectly enhancing estrogen and ALP.

Author Contributions

Animal experiments, K.Y.K. and C.H.N.; Cell studies, K.E,T. and Z.B.; EVs preparations, H.S.J. and D.P.; Experimental design, writing & editing, D.P. and Y.B.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Human amniotic membrane tissues were obtained through Caesarean section from a healthy pregnant female donor. All sample collection procedures from human beings were approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Korea University Anam Hospital, Korea (Approval No. 2020AN0305).

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent on the collection of amniotic membrane tissues was obtained from the donor.

Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee Statement

All animal experiments were performed following protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of Chungbuk National University (CBNU), Korea (Approval No. CBNUA-1754-22-01).

Acknowledgments

In this section, you can acknowledge any support given which is not covered by the author contribution or funding sections. This may include administrative and technical support, or donations in kind (e.g., materials used for experiments).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- LeBoff, M.S.; Greenspan, S.L.; Insogna, K.L.; Lewiecki, E.M.; Saag, K.G.; Singer, A.J.; Siris, E.S. The clinician’s guide to prevention and treatment of osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int. 2022, 33, 2049–2102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhatnagar, A.; Kekatpure, L. Postmenopausal osteoporosis: A literature review. Cureus 2022, 14, e29367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khosla, S.; Oursler, M.J.; Monroe, D.G. Estrogen and the skeleton. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2012, 23, 576–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, C.H.; Chen, L.R.; Chen, K.H. Osteoporosis due to hormone imbalance: An overview of the effects of estrogen deficiency and glucocorticoid overuse on bone turnover. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, M.X.; Yu, Q. Primary osteoporosis in postmenopausal women. Chronic Dis. Transl. Med. 2015, 1, 9–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khalid, A.B.; Krum, S.A. Estrogen receptors alpha and beta in bone. Bone 2016, 87, 130–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.M.; Lin, C.; Stavre, Z.; Greenblatt, M.B.; Shim, J.H. Osteoblast–osteoclast communication and bone homeostasis. Cells 2020, 9, 2073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, A.A.; Sandor, G.K.B.; Dore, E.; Morrison, A.D.; Alsahli, M.; Amin, F.; Peters, E.; Hanley, D.A.; Chaudry, S.R.; Lentle, B.; Dempster, D.W.; Glorieux, F.H.; Neville, A.J.; Talwar, R.M.; Clokie, C.M.; Mardini, M.A.; Paul, T.; Khosla, S.; Josse, R.G.; Sutherland, S.; Lam, D.K.; Carmichael, R.P.; Blanas, N.; Kendler, D.; Petak, S.; Ste-Marie, L.G.; Brown, J.; Evans, A.W.; Rios, L.; Compston, J.E. Bisphosphonate associated osteonecrosis of the jaw. J. Rheumatol. 2009, 36, 478–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lo, J.C.; O'Ryan, F.S.; Gordon, N.P.; Yang, J.; Hui, R.L.; Martin, D.; Hutchinson, M.; Lathon, P.V.; Sanchez, G.; Silver, P.; Chandra, M.; McCloskey, C.A.; Staffa, J.A.; Willy, M.; Selby, J.V.; Go, A.S. Prevalence of osteonecrosis of the jaw in patients with oral bisphosphonate exposure. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2013, 68, 243–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saleh, A.; Hegde, V.V.; Potty, A.G.; Lane, J.M. Bisphosphonate therapy and atypical fractures. Orthop. Clin. North Am. 2013, 44, 137–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, G.W.; Zheng, X.; Chang, S.X.; Zhou, L.; Wang, X.Y.; Nian, H.; Shi, X. Influence of early zoledronic acid administration on bone marrow fat in ovariectomized rats. Endocrinology 2014, 155, 4731–4738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Undale, A.H.; Westendorf, J.J.; Yaszemski, M.J.; Khosla, S. Mesenchymal stem cells for bone repair and metabolic bone diseases. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2009, 84, 893–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baraniak, P.R.; McDevitt, T.C. Stem cell paracrine actions and tissue regeneration. Regen. Med. 2010, 5, 121–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linero, I.; Chaparro, O. Paracrine effect of mesenchymal stem cells derived from human adipose tissue in bone regeneration. PLoS One 2014, 9, e107001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, C.P.; Chio, C.C.; Cheong, C.U.; Chao, C.M.; Cheng, B.C.; Lin, M.T. Hypoxic preconditioning enhances the therapeutic potential of the secretome from cultured human mesenchymal stem cells in experimental traumatic brain injury. Clin. Sci. (Lond) 2013, 124, 165–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.H.; Yoon, Y.M.; Lee, S.H. Hypoxic preconditioning promotes the bioactivities of mesenchymal stem cells via the HIF-1α-GRP78-Akt axis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tkach, M.; Thery, C. Communication by extracellular vesicles: Where we are and where we need to go. Cell 2016, 164, 1226–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Bi, J.; Huang, J.; Tang, Y.; Du, S.; Li, P. Exosome: A review of its classification, isolation techniques, storage, diagnostic and targeted therapy applications. Int. J. Nanomedicine 2020, 22, 6917–6934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seong, H.R.; Noh, C.H.; Park, S.; Cho, S.; Hong, S.J.; Lee, A.y.; Geum, D.; Hong, S.C.; Park, D.; Kim, T.M.; Choi, E.K.; Kim, Y.B. Intraocular pressure-lowering and retina-protective effects of exosome-rich conditioned media from human amniotic membrane stem cells in a rat model of glaucoma. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 8073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noh, C.H.; Park, S.; Seong. H.R.; Lee A.y.; Tsolmon, K.E.; Geum, D.; Hong, S.C.; Kim, T.M.; Choi, E.K.; Kim, Y.B. An exosome-rich conditioned medium from human amniotic membrane stem cells facilitates wound healing via increased reepithelization, collagen synthesis, and angiogenesis. Cells 2023, 12, 2698.

- Hu, K.; Olsen, B.R. Osteoblast-derived VEGF regulates osteoblast differentiation and bone formation during bone repair. J. Clin. Invest. 2016, 126, 509–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, J.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, W.J.; Ye, T.W.; Chen, A. Resveratrol attenuates lipopolysaccharides (LPS)-induced inhibition of osteoblast differentiation in MC3T3-E1 cells. Med. Sci. Monit. 2018, 24, 2045–2052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Komori, T. Animal models for osteoporosis. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2015, 759, 287–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Souza, V.R.; Mendes, E.; Casaro, M.; Antiorio, A.T.F.B. Description of ovariectomy protocol in mice. Methods Mol. Biol. 2019, 1916, 303–309. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jiang, G.Z.; Matsumoto, H.; Hori, M.; Gunji, A.; Hakozaki, K.; Akimoto, Y.; Fujii, A. Correlation among geometric, densitometric, and mechanical properties in mandible and femur of osteoporotic rats. J. Bone Miner. Metab. 2008, 26, 130–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, C.; Lee, J.H.; Han, S.S.; Kim, Y.H.; Choi, Y.J.; Jeon, K.J.; Jung, H.I. Site-specific and time-course changes of postmenopausal osteoporosis in rat mandible: comparative study with femur. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 14155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batoon, L.; Millard, S.M.; Raggatt, L.J.; Wu, A.C.; Kaur, S.; Sun, L.W.H.; Williams, K.; Sandrock, C.; Ng, P.Y.; Irvine, K.M.; Bartnikowski, M.; Glatt, V.; Pavlos, N.J.; Pettit, A.R. Osteal macrophages support osteoclast-mediated resorption and contribute to bone pathology in a postmenopausal osteoporosis mouse model. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2021, 36, 2214–2228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, B.; Su, Y.; Shen, E.; Song, M.; Liu, D.; Qi, H. Extracellular vesicles from GPNMB-modified bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells attenuate bone loss in an ovariectomized rat model. Life Sci. 2021, 272, 119208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, Y.; Guo, Y.; Kong, L.; Shi, J.; Liu, P.; Li, R.; Geng, Y.; Gao, W.; Zhang, Z.; Fu, D. A bone-targeted engineered exosome platform delivering siRNA to treat osteoporosis. Bioact. Mater. 2022, 10, 207–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Negri, S.; Wang, Y.; Sono, T.; Lee, S.; Hsu, G.C.; Xu, J.; Meyers, C.A.; Qin, Q.; Broderick, K.; Witwer, K.W.; Peault, B.; James, A.W. Human perivascular stem cells prevent bone graft resorption in osteoporotic contexts by inhibiting osteoclast formation. Stem Cells Transl. Med. 2020, 9, 1617–1630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lizcano, F.; Guzman, G. Estrogen deficiency and the origin of obesity during menopause. Biomed. Res. Int. 2014, 2014, 757461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaggini, M.; Morelli, M.; Buzzigoli, E.; DeFronzo, R.A.; Bugianesi, E.; Gastaldelli, A. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and its connection with insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, atherosclerosis and coronary heart disease. Nutrients 2013, 5, 1544–1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Byrne, C.D.; Targher, G. NAFLD: A multisystem disease. J. Hepatol. 2015, 62, S47–S64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panneerselvam, S.; Packirisamy, R.M.; Bobby, Z.; Jacob, S.E.; Sridhar, M.G. Soy isoflavones (Glycine max) ameliorate hypertriglyceridemia and hepatic steatosis in high fat-fed ovariectomized Wistar rats (an experimental model of postmenopausal obesity). J. Nutr. Biochem. 2016, 38, 57–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, R.; Lin, M.; Li, L.; Li, L.; Qi, G.; Rong, R.; Xu, M.; Zhu, T. Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosome protects kidney against ischemia reperfusion injury in rats. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi 2014, 94, 3298–3303. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Narayanan, R.; Huang, C.C.; Ravindran, S. Hijacking the cellular mail: Exosome mediated differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cells Int. 2016, 2016, 3808674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tao, S.C.; Yuan, T.; Zhang, Y.L.; Yin, W.J.; Guo, S.C.; Zhang, C.Q. Exosomes derived from miR-140-5p-overexpressing human synovial mesenchymal stem cells enhance cartilage tissue regeneration and prevent osteoarthritis of the knee in a rat model. Theranostics 2017, 7, 180–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strom, J.O.; Theodorsson, E.; Theodorsson, A. Order of magnitude differences between methods for maintaining physiological 17beta-oestradiol concentrations in ovariectomized rats. Scand. J. Clin. Lab. Invest. 2008, 68, 814–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Gendy, A.A.; Elsaed, W.M.; Abdallah, H.I. Potential role of estradiol in ovariectomy-induced derangement of renal endocrine functions. Ren. Fail. 2019, 41, 507–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.H.; Jang, J.W.; Lee, J.K.; Park, C.K. Rutin Improves Bone histomorphometric values by reduction of osteoclastic activity in osteoporosis mouse model induced by bilateral ovariectomy. J. Korean Neurosurg. Soc. 2020, 63, 433–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simpson, ER. Sources of estrogen and their importance. J. Steriod Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2003, 86, 225–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, J.; Shen, Y.; Li, R. Estrogen synthesis and signaling pathways during ageing: from periphery to brain. Trends Mol. Med. 2013, 19, 197–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hetemaki, N.; Mikkola, T.S.; Tikkanen, M.J.; Wang, F.; Hamalainen, E.; Turpeinen, U.; Haanpaa, M.; Vihma, V.; Peltonen, H.S. Adipose tissue estrogen production and metabolism in premenopausal women. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2021, 209, 105849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bauss, F.; Dempster, D.W. Effects of ibandronate on bone quality: preclinical studies. Bone 2007, 40, 265–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lei, Z.; Xiaoying, Z.; Xingguo, L. Ovariectomy-associated changes in bone mineral density and bone marrow haematopoiesis in rats. Int. J. Exp. Pathol. 2009, 90, 512–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, X.L.; Huang, L.Y.; Cheng, Y.T.; Li, F.; Zhou, Q.; Wu, C.; Shi, Q.H.; Guan, Z.Z.; Liao, J.; Hong, W. Zoledronic acid inhibits osteoclast differentiation and function through the regulation of NF-κB and JNK signalling pathways. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2019, 44, 582–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, X.L.; Liu, C.; Shi, X.M.; Cheng, Y.T.; Zhou, Q.; Li, J.P.; Liao, J. Zoledronic acid inhibits osteoclastogenesis and bone resorptive function by suppressing RANKL-mediated NF-κB and JNK and their downstream signalling pathways. Mol. Med. Rep. 2022, 25, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, B.; Zhan, Y.; Yan, L.; Hao, D. How zoledronic acid improves osteoporosis by acting on osteoclasts. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 961941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Figure 1.

Osteoblast-proliferative and -protective activities of amniotic stem cell extracellular vesicles (EVs). A: MC3T3-E1 cells were treated with EVs and incubated for 24 hours. B & C: MC3T3-E1 cells were treated with EVs and exposed to 200 μM H2O2 (B) or hypoxic (2% O2) condition (C) for 24 hours.

Figure 1.

Osteoblast-proliferative and -protective activities of amniotic stem cell extracellular vesicles (EVs). A: MC3T3-E1 cells were treated with EVs and incubated for 24 hours. B & C: MC3T3-E1 cells were treated with EVs and exposed to 200 μM H2O2 (B) or hypoxic (2% O2) condition (C) for 24 hours.

Figure 2.

Change in body weight of ovariectomized (OVX) rats treated with extracellular vesicles (EVs) or zoledronic acid (ZA). ○: Sham control, ●: OVX alone, ▲: OVX + 1 x 108 EVs/body, ▼: OVX + 3 x 108 EVs/body, ◆: OVX + 1 x 109 EVs/body, ■: OVX + ZA (100 μg/kg).

Figure 2.

Change in body weight of ovariectomized (OVX) rats treated with extracellular vesicles (EVs) or zoledronic acid (ZA). ○: Sham control, ●: OVX alone, ▲: OVX + 1 x 108 EVs/body, ▼: OVX + 3 x 108 EVs/body, ◆: OVX + 1 x 109 EVs/body, ■: OVX + ZA (100 μg/kg).

Figure 3.

Blood 17β-estradiol (A), alkaline phosphatase (ALP) (B), and calcium (C) levels of ovariectomized (OVX) rats treated with extracellular vesicles (EVs; 1 x 108–1 x 109 particles/body) or zoledronic acid (ZA; 100 μg/kg). *Significantly different from Sham control (P < 0.05). #Significantly different from OVX alone (P < 0.05).

Figure 3.

Blood 17β-estradiol (A), alkaline phosphatase (ALP) (B), and calcium (C) levels of ovariectomized (OVX) rats treated with extracellular vesicles (EVs; 1 x 108–1 x 109 particles/body) or zoledronic acid (ZA; 100 μg/kg). *Significantly different from Sham control (P < 0.05). #Significantly different from OVX alone (P < 0.05).

Figure 4.

Bone mineral density (BMD) (A), bone mineral content (BMC) (B), and bending strength (C) of the femurs of ovariectomized (OVX) rats treated with extracellular vesicles (EVs; 1 x 108–1 x 109 particles/body) or zoledronic acid (ZA; 100 μg/kg). *Significantly different from Sham control (P < 0.05). #Significantly different from OVX alone (P < 0.05).

Figure 4.

Bone mineral density (BMD) (A), bone mineral content (BMC) (B), and bending strength (C) of the femurs of ovariectomized (OVX) rats treated with extracellular vesicles (EVs; 1 x 108–1 x 109 particles/body) or zoledronic acid (ZA; 100 μg/kg). *Significantly different from Sham control (P < 0.05). #Significantly different from OVX alone (P < 0.05).

Figure 5.

Representative 3D reconstruction of micro-computed tomographic images of the femurs of ovariectomized (OVX) rats treated with extracellular vesicles (EVs; 1 x 108–1 x 109 particles/body) or zoledronic acid (ZA; 100 μg/kg). The area of cancellous bone loss was marked with a star (★) and regenerated trabecular bones were marked with arrows.

Figure 5.

Representative 3D reconstruction of micro-computed tomographic images of the femurs of ovariectomized (OVX) rats treated with extracellular vesicles (EVs; 1 x 108–1 x 109 particles/body) or zoledronic acid (ZA; 100 μg/kg). The area of cancellous bone loss was marked with a star (★) and regenerated trabecular bones were marked with arrows.

Figure 6.

Representative histomorphometric parameters in the femurs of Sham control (A) and ovariectomized (B) rats. Tb.Th: trabecular thickness, Tb.N: trabecular number, Tb.Sp: trabecular space.

Figure 6.

Representative histomorphometric parameters in the femurs of Sham control (A) and ovariectomized (B) rats. Tb.Th: trabecular thickness, Tb.N: trabecular number, Tb.Sp: trabecular space.

Figure 7.

Histomorphometric parameters in the femurs of ovariectomized (OVX) rats treated with extracellular vesicles (EVs; 1 x 108–1 x 109 particles/rat) or zoledronic acid (ZA; 100 μg/kg). A: bone volume/tissue volume (BV/TV) ratio, B: trabecular thickness (Tb.Th), C: trabecular number (Tb.N), D: trabecular space (Tb.Sp). *Significantly different from Sham control (P<0.05). #Significantly different from OVX alone (P < 0.05).

Figure 7.

Histomorphometric parameters in the femurs of ovariectomized (OVX) rats treated with extracellular vesicles (EVs; 1 x 108–1 x 109 particles/rat) or zoledronic acid (ZA; 100 μg/kg). A: bone volume/tissue volume (BV/TV) ratio, B: trabecular thickness (Tb.Th), C: trabecular number (Tb.N), D: trabecular space (Tb.Sp). *Significantly different from Sham control (P<0.05). #Significantly different from OVX alone (P < 0.05).

Table 1.

The body and organ weights of ovariectomized (OVX) rats treated with extracellular vesicles (EVs) or zoledronic acid (ZA).

Table 1.

The body and organ weights of ovariectomized (OVX) rats treated with extracellular vesicles (EVs) or zoledronic acid (ZA).

| Weight |

Sham control |

OVX alone |

+ EVs

(1x108/body) |

+ EVs

(3x108/body) |

+ EVs

(1x109/body) |

+ ZA

(100 μg/kg) |

Body weight

(g) |

434.3

±37.7 |

442.9

±30.9 |

439.7

±30.0 |

446.4

±18.0 |

435.5

±20.4 |

441.7

±17.6 |

| Liver |

Absolute (g) |

8.99

±0.21 |

9.68

±0.94 |

9.63

±0.27 |

9.62

±1.01 |

9.48

±0.80 |

9.36

±1.25 |

| Relative (%) |

2.06

±0.19 |

2.19

±0.09 |

2.19

±0.13 |

2.16

±0.20 |

2.15

±0.14 |

2.15

±0.26 |

| Kidneys |

Absolute (g) |

1.82

±0.12 |

2.04

±0.22 |

1.86

±0.08 |

1.86

±0.20 |

1.90

±0.26 |

1.82

±0.64 |

| Relative (%) |

0.42

±0.01 |

0.46

±0.02 |

0.42

±0.02 |

0.42

±0.04 |

0.43

±0.06 |

0.42

±0.18 |

| Spleen |

Absolute (g) |

0.86

±0.17 |

0.75

±0.22 |

0.81

±0.14 |

0.70

±0.09 |

0.76

±0.09 |

0.82

±0.13 |

| Relative (%) |

0.20

±0.03 |

0.17

±0.05 |

0.18

±0.03 |

0.16

±0.02 |

0.17

±0.02 |

0.19

±0.03 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).