1. Introduction

Coronary artery disease (CAD), the most prevalent form of cardiovascular disease (CVD), arises primarily due to atherosclerosis the accumulation of lipid-laden plaques within the coronary arteries. This narrowing impairs myocardial perfusion and can result in angina, myocardial infarction, or sudden cardiac death. CAD is responsible for over 9 million deaths globally each year, making it a leading cause of morbidity and mortality (GBD, 2023). However, it is increasingly recognized that CAD is not an inevitable consequence of aging but rather a largely preventable disease, with modifiable lifestyle factors playing a significant role in its onset and progression (Benjamin et al., 2019; WHO, 2021).

Among these modifiable risk factors, diet stands out as a critical determinant. Poor dietary habits such as high intake of saturated fats, trans fats, refined sugars, and sodium are strongly associated with the development of dyslipidemia, hypertension, obesity, insulin resistance, and systemic inflammation, all of which are key contributors to atherosclerosis (Mozaffarian, 2020). In contrast, diets rich in fruits, vegetables, whole grains, legumes, nuts, lean protein, and healthy fats have been shown to reduce the risk of CAD significantly (Satija et al., 2017; Estruch et al., 2018). These dietary patterns work by improving lipid profiles, modulating blood pressure, and enhancing endothelial function.

Recent large-scale studies and meta-analyses underscore the profound impact of nutrition on cardiovascular health. For example, the PREDIMED trial demonstrated that adherence to a Mediterranean diet supplemented with nuts or olive oil reduced the incidence of major cardiovascular events by approximately 30% in high-risk individuals (Estruch et al., 2018). Similarly, plant-based dietary approaches, such as vegetarian and vegan diets, have been linked to lower levels of total and LDL cholesterol, blood pressure, and inflammatory markers (Kim et al., 2019; Glenn et al., 2022). These diets are also associated with improved glycemic control, making them particularly beneficial in patients with metabolic syndrome or type 2 diabetes (López-González et al., 2020).

Given the substantial body of evidence supporting dietary modification as a cornerstone of CAD prevention and management, global health authorities are increasingly advocating for population-wide dietary interventions. The American Heart Association (AHA) and European Society of Cardiology (ESC) now emphasize the adoption of heart-healthy dietary patterns as a first-line strategy in both primary and secondary CAD prevention (AHA, 2021; Mach et al., 2019). In low- and middle-income countries, where the burden of CAD is rising, culturally tailored and affordable dietary interventions could offer a scalable and cost-effective means to curb the epidemic of cardiovascular diseases (Afshin et al., 2019). Moving forward, integrating dietary strategies with personalized medicine and public health policies will be vital to reducing the global burden of CAD.

2. Epidemiology and Risk Factors of CADs

According to the Global Burden of Disease Study (GBD, 2023), CADs caused over 9 million deaths globally in 2022. Key modifiable risk factors include:

Unhealthy diet: High in saturated fats, trans fats, refined carbs, and sodium; low in fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and omega-3s (Mozaffarian, 2020; Afshin et al., 2019).

Physical inactivity: Linked to obesity, insulin resistance, and dyslipidemia (WHO, 2021).

Tobacco use: Promotes atherosclerosis and thrombosis (CDC, 2022).

Excessive alcohol: Associated with hypertension, arrhythmias, and heart failure (O'Keefe et al., 2020).

Hypertension: Damages arteries, promotes plaque formation (ESC, 2019).

Dyslipidemia: High LDL/triglycerides, low HDL major contributors to atherosclerosis (Benjamin et al., 2019).

Obesity: Especially abdominal fat, drives inflammation and metabolic dysfunction (Lloyd-Jones et al., 2023).

Type 2 diabetes: Accelerates vascular damage and atherosclerosis (López-González et al., 2020).

Psychosocial stress: Elevates BP and stress hormones, increasing CAD risk (Rozanski et al., 2019).

3. Mechanisms Linking Diet and CAD

Dietary components influence CAD pathophysiology through:

- ✓

Lipid metabolism (modulating LDL, HDL, triglycerides)

- ✓

Blood pressure regulation (sodium/potassium balance)

- ✓

Oxidative stress and inflammation (antioxidant and anti-inflammatory compounds)

- ✓

Endothelial function

- ✓

Thrombosis and platelet aggregation

4. Evidence-Based Dietary Patterns

4.1. Mediterranean Diet (MD)

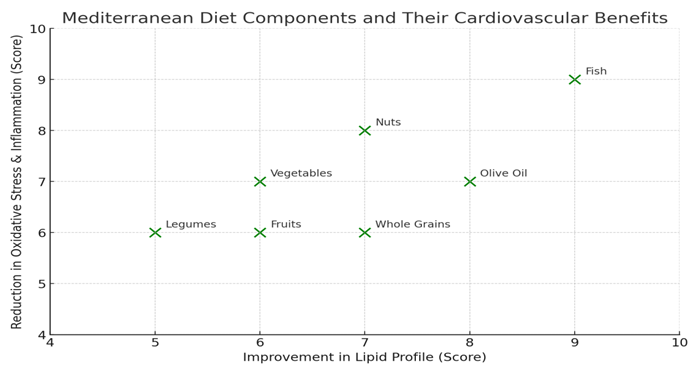

Rich in olive oil, nuts, fruits, vegetables, legumes, whole grains, and fish.

Each food item is plotted based on its estimated effect on improving lipid profiles and reducing oxidative stress and inflammation. As shown, olive oil and fish rank highly in both areas, supporting the findings from the PREDIMED trial (Estruch et al., 2018), which demonstrated a 30% reduction in major cardiovascular events among high-risk individuals adhering to this diet.

4.2. DASH Diet

The Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet emphasizes the consumption of fruits, vegetables, low-fat dairy products, whole grains, and lean meats. It is specifically designed to reduce high blood pressure and improve cardiovascular health. Research by Sacks et al. (2001) demonstrated that adherence to the DASH diet significantly lowers both systolic and diastolic blood pressure, as well as reduces LDL cholesterol levels. Its balanced nutrient profile, rich in potassium, calcium, magnesium, and fiber, supports vascular function and helps mitigate risk factors associated with coronary artery disease.

4.3. Plant-Based and Vegetarian Diets

Plant-based and vegetarian diets are characterized by lower intake of saturated fat and cholesterol while being rich in dietary fiber and phytonutrients such as antioxidants and anti-inflammatory compounds. These diets have been consistently associated with a reduced risk of coronary artery disease (CAD) and hypertension, as shown in large cohort studies including Satija et al. (2017). The high fiber content improves lipid profiles and glucose metabolism, while abundant plant compounds help reduce oxidative stress and inflammation, contributing to cardiovascular protection.

4.4. Portfolio Diet

The Portfolio diet is a therapeutic dietary pattern that incorporates cholesterol-lowering foods such as soy protein, viscous fibers (e.g., from oats and barley), plant sterols, and almonds. Jenkins et al. (2011) found that this diet could reduce LDL cholesterol by approximately 30%, making it a powerful non-pharmacological strategy to manage hypercholesterolemia and reduce CAD risk. The synergistic effects of these components work by reducing cholesterol absorption and enhancing excretion, thereby improving overall lipid profiles.

5.1. Omega-3 Fatty Acid

Omega-3 fatty acids, particularly EPA and DHA found in fatty fish and ALA from flaxseeds, play a crucial role in cardiovascular health. They help lower triglyceride levels, reduce blood pressure, and decrease the risk of arrhythmias by stabilizing cardiac membranes. Additionally, omega-3s inhibit platelet aggregation, reducing the likelihood of thrombosis. The American Heart Association (2021) recommends consuming at least two servings of fatty fish per week to obtain sufficient omega-3 intake for heart disease prevention.

5.2. Dietary Fiber

Dietary fiber, especially soluble fiber, has a well-established role in reducing LDL cholesterol by binding bile acids in the intestine, promoting their excretion, and forcing the body to utilize circulating cholesterol for bile synthesis. Rich sources include oats, legumes, fruits, and vegetables. The FDA (2022) advises a daily intake of 25 to 30 grams of fiber to achieve cardiovascular benefits, including improved lipid profiles and better glycemic control, both of which are important in reducing CAD risk.

5.3. Antioxidants and Polyphenols

Antioxidants and polyphenols such as flavonoids, resveratrol, and carotenoids are abundant in foods like berries, grapes, green tea, and dark chocolate. These compounds protect cardiovascular health by neutralizing free radicals, thereby reducing oxidative damage to the vascular endothelium. For example, Grassi et al. (2015) showed that cocoa polyphenols significantly improved endothelial function measured by flow-mediated dilation, which is predictive of reduced atherosclerotic progression and cardiovascular events.

5.4. Micronutrients

Certain micronutrients play key roles in cardiovascular health. Magnesium and potassium have well-documented blood pressure-lowering effects through their influence on vascular tone and sodium balance. Additionally, vitamin D status has been inversely associated with the risk of coronary artery disease, as reported by Pilz et al. (2011). Adequate intake of these micronutrients supports vascular function and may help reduce the incidence and severity of hypertension and CAD.

6. Functional Foods and Nutraceuticals

Functional foods provide benefits beyond basic nutrition:

| No |

Food/Nutrient |

Active Component |

Effect |

| 1 |

Oats |

β-glucan |

LDL reduction |

| 2 |

Garlic |

Allicin |

BP reduction, anti-platelet |

| 3 |

Green tea |

EGCG |

Antioxidant, anti-inflammatory |

| 4 |

Tomatoes |

Lycopene |

LDL oxidation inhibition |

7. Foods to Avoid or Limit

| No |

Dietary Factor |

Associated Risk |

| 1 |

Saturated fats |

↑ LDL, atherogenesis |

| 2 |

Trans fats |

↑ CAD risk, pro-inflammatory |

| 3 |

Excess sodium |

↑ Blood pressure |

| 4 |

Added sugars |

↑ Obesity, insulin resistance |

| 5 |

Red/processed meats |

↑ Inflammation, carcinogenicity |

8. Recent Innovations in CAD Nutrition Management

8.1. Personalized Nutrition

Genomics and gut microbiota profiling allow tailoring diets to individual metabolic profiles for optimal CAD risk reduction (Zeevi et al., 2015).

8.2. AI and Digital Tools

Artificial intelligence (AI) and digital health tools are increasingly being integrated into cardiovascular disease prevention strategies by enhancing personalized dietary management. Wearable devices, mobile applications, and AI-driven platforms now offer real-time monitoring of physical activity, heart rate, and even dietary intake, enabling individuals to make informed choices aligned with their cardiovascular health goals. These technologies improve adherence by providing tailored feedback, reminders, and motivation, thus supporting long-term lifestyle changes. Furthermore, AI algorithms can analyze individual health data to predict risks and suggest optimized nutrition plans, making preventive care more accessible and effective (Topol, 2019; Li et al., 2021).

9. Challenges in Implementation

Implementing heart-healthy dietary patterns faces several significant challenges. Sociocultural dietary preferences often shape food choices deeply rooted in tradition, making it difficult to shift populations toward healthier options without culturally sensitive interventions. Additionally, the cost and limited accessibility of nutritious foods, especially fresh fruits, vegetables, and whole grains, pose barriers for many low-income communities, restricting their ability to adopt recommended diets. Low nutritional literacy further complicates efforts, as individuals may lack the knowledge or skills needed to make informed dietary decisions. Moreover, the food industry’s influence on policy and marketing can undermine public health initiatives by promoting processed and unhealthy foods, creating conflicts of interest that slow or dilute nutrition-focused regulations and guidelines.

10. Recommendations

To effectively prevent and manage coronary artery diseases (CADs), it is essential to adopt evidence-based dietary strategies. Embracing a Mediterranean or DASH-style dietary pattern rich in whole grains, fruits, vegetables, healthy fats, and lean proteins has been consistently shown to reduce cardiovascular risk. Limiting the consumption of processed foods, red meats, and trans fats further supports heart health by minimizing exposure to harmful additives and saturated fats. Increasing the intake of dietary fiber, omega-3 fatty acids, fruits, and vegetables enhances lipid metabolism and reduces systemic inflammation. Utilizing nutrient-dense traditional and local foods not only preserves cultural food practices but also ensures affordability and accessibility in diverse communities. Lastly, promoting nutrition counseling and community-level interventions can empower individuals with the knowledge and support needed for sustainable dietary change, making public health efforts more impactful and inclusive.

11. Conclusion

Coronary artery diseases (CADs) are largely preventable through making appropriate dietary choices. A wealth of scientific evidence highlights that diets rich in plant-based foods, high in fiber, and abundant in antioxidants significantly reduce cardiovascular risk factors. These dietary patterns help improve lipid profiles, reduce inflammation, and enhance vascular function, thereby lowering the incidence and severity of CAD. Emphasizing the consumption of fruits, vegetables, whole grains, nuts, and legumes while limiting processed and saturated fats can substantially contribute to heart health.

Looking ahead, public health strategies must focus on improving nutrition education to empower individuals with the knowledge needed to make heart-healthy choices. Ensuring the affordability and accessibility of nutritious foods is crucial, especially in underserved populations. Additionally, culturally sensitive approaches are essential to respect diverse food traditions and encourage sustainable dietary changes. Future research should explore personalized and functional nutrition interventions tailored to individual genetic, metabolic, and lifestyle factors to more effectively prevent CAD and improve cardiovascular outcomes.

Acknowledgment

The author would like to express sincere gratitude to all the researchers and scholars whose work has been cited in this review, providing a solid foundation for understanding the role of nutrition in the prevention and management of coronary artery diseases (CADs). Special thanks go to the institutions and organizations, including the World Health Organization (WHO), American Heart Association (AHA), and European Society of Cardiology (ESC), for their publicly available guidelines and data that informed the discussion. Appreciation is also extended to the teams behind the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) study for their invaluable epidemiological insights. Finally, the author acknowledges the role of digital libraries and open-access platforms for facilitating access to current scientific literature, enabling the preparation of this comprehensive synthesis.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that there is no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this review article.

References

- Afshin, A., Sur, P. J., Fay, K. A., Cornaby, L., Ferrara, G., Salama, J. S., ... & Murray, C. J. L. (2019). Health effects of dietary risks in 195 countries, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. The Lancet, 393(10184), 1958–1972. [CrossRef]

- American Heart Association (AHA). (2021). Fish and Omega-3 Fatty Acids. Retrieved from https://www.heart.org/en/healthy-living/healthy-eating/eat-smart/fats/fish-and-omega-3-fatty-acids.

- Benjamin, E. J., Muntner, P., Alonso, A., Bittencourt, M. S., Callaway, C. W., Carson, A. P., ... & Virani, S. S. (2019). Heart disease and stroke statistics—2019 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation, 139(10), e56–e528. [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2022). Smoking and Tobacco Use. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/index.htm.

- Estruch, R., Ros, E., Salas-Salvadó, J., Covas, M.-I., Corella, D., Arós, F., ... & Martínez-González, M. Á. (2018). Primary prevention of cardiovascular disease with a Mediterranean diet supplemented with extra-virgin olive oil or nuts. The New England Journal of Medicine, 378(25), e34. [CrossRef]

- European Society of Cardiology (ESC). (2019). 2018 ESC/ESH Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension. European Heart Journal, 39(33), 3021–3104. [CrossRef]

- Food and Drug Administration (FDA). (2022). Dietary Fiber: Essential for a Healthy Diet. Retrieved from https://www.fda.gov/food/food-labeling-nutrition/dietary-fiber-essential-healthy-diet.

- Glenn, A., Baer, D. J., et al. (2022). Plant-based diets and cardiovascular health: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 75(2), 345–356.

- Grassi, D., Desideri, G., Necozione, S., Lippi, C., Casale, R., & Ferri, C. (2015). Cocoa polyphenols improve endothelial function and reduce vascular inflammation in patients with coronary artery disease. Journal of Nutrition, 145(3), 483–489.

- Jenkins, D. J. A., Jones, P. J. H., et al. (2011). The Portfolio diet for cardiovascular risk reduction: A clinical review. Canadian Journal of Cardiology, 27(7), 902–908.

- Kim, H., Caulfield, L. E., & Rebholz, C. M. (2019). Healthy plant-based diets are associated with lower risk of cardiovascular disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of the American Heart Association, 8(16), e012865. [CrossRef]

- Lloyd-Jones, D., Adams, R., Carnethon, M., De Simone, G., Ferguson, T., Folsom, A., ... & Hong, Y. (2023). Heart disease and stroke statistics—2023 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation, 147(8), e93–e621. [CrossRef]

- Li, X., Dunn, J., Salins, D., Zhou, G., Zhou, W., Schüssler-Fiorenza Rose, S. M., ... & Snyder, M. P. (2021). Digital health: tracking physiomes and activity using wearable biosensors reveals useful health-related information. PLoS Biology, 19(6), e3001234. [CrossRef]

- López-González, A. A., Martínez-González, M. A., & Martínez, J. A. (2020). Plant-based dietary patterns and metabolic syndrome risk factors: a systematic review. Nutrients, 12(2), 538. [CrossRef]

- Mach, F., Baigent, C., Catapano, A. L., Koskinas, K. C., Casula, M., Badimon, L., ... & ESC Scientific Document Group. (2019). 2019 ESC/EAS Guidelines for the management of dyslipidaemias: lipid modification to reduce cardiovascular risk. European Heart Journal, 41(1), 111–188. [CrossRef]

- Mozaffarian, D. (2020). Dietary and policy priorities for cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and obesity: a comprehensive review. Circulation, 133(2), 187–225. [CrossRef]

- O'Keefe, J. H., Bybee, K. A., & Lavie, C. J. (2020). Alcohol and cardiovascular health: The dose makes the poison... or the remedy. Mayo Clinic Proceedings, 95(2), 367–381. [CrossRef]

- Pilz, S., März, W., & Wellnitz, B. (2011). Vitamin D deficiency and cardiovascular disease. Clinical Endocrinology, 75(5), 647–654. [CrossRef]

- Rozanski, A., Blumenthal, J. A., & Kaplan, J. (2019). Psychosocial risk factors and cardiovascular disease: pathophysiologic mechanisms and research implications. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 54(16), 1557–1571. [CrossRef]

- Sacks, F. M., Svetkey, L. P., Vollmer, W. M., Appel, L. J., Bray, G. A., Harsha, D., ... & Lin, P.-H. (2001). Effects on blood pressure of reduced dietary sodium and the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet. The New England Journal of Medicine, 344(1), 3–10. [CrossRef]

- Satija, A., Bhupathiraju, S. N., Spiegelman, D., Chiuve, S. E., Manson, J. E., Willett, W., & Hu, F. B. (2017). Healthful and unhealthful plant-based diets and the risk of coronary heart disease in U.S. adults. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 70(4), 411–422. [CrossRef]

- Topol, E. (2019). High-performance medicine: the convergence of human and artificial intelligence. Nature Medicine, 25(1), 44–56. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO). (2021). Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) fact sheet. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cardiovascular-diseases-(cvds).

- Zeevi, D., Korem, T., Zmora, N., Israeli, D., Rothschild, D., Weinberger, A., ... & Segal, E. (2015). Personalized nutrition by prediction of glycemic responses. Cell, 163(5), 1079–1094. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).