Submitted:

13 July 2025

Posted:

14 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Model Setup

3. Three-Step Estimation Methodology

3.1. Initial Estimation of Bivariate Varying-Coefficient Function

3.2. Estimation of FAR Error Process

3.3. Improved Estimation of Bivariate Varying-Coefficient Function

3.4. Implementation

3.4.1. Selection of Bandwidth

3.4.2. Identifying the Order of the FAR Process

4. Theoretical Results

5. Numerical Study

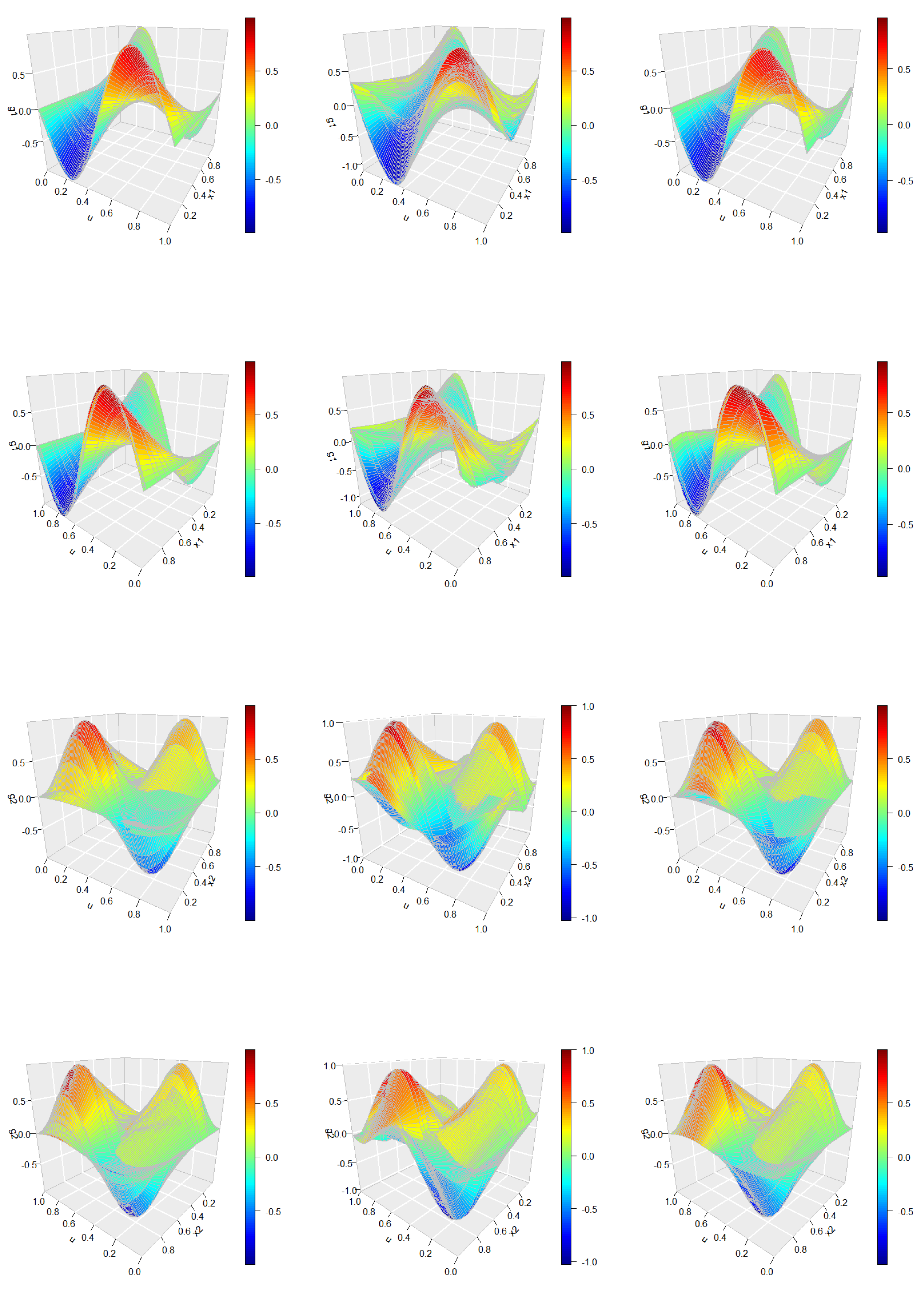

5.1. Case 1

5.2. Case 2

6. Real Data Analysis

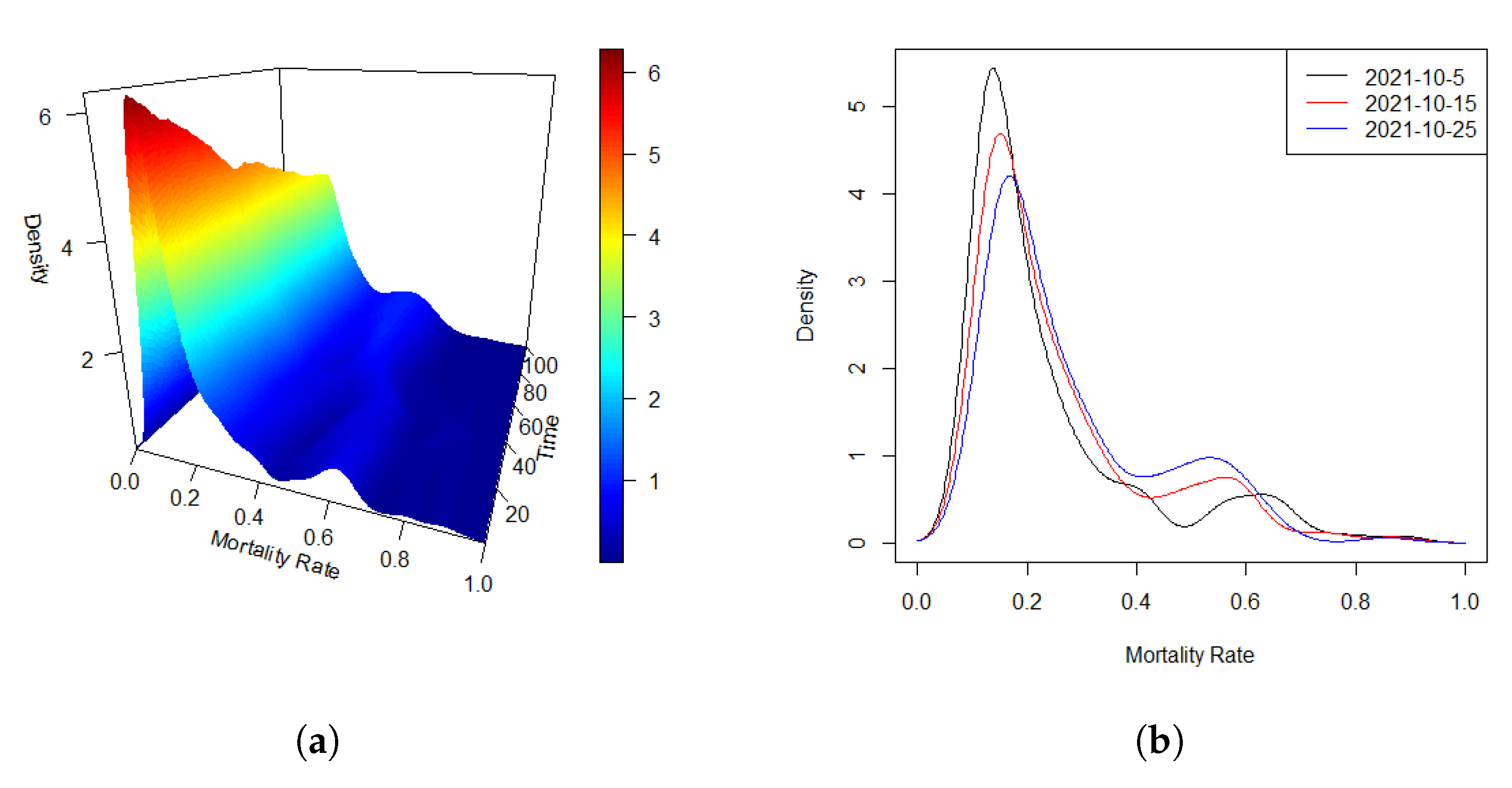

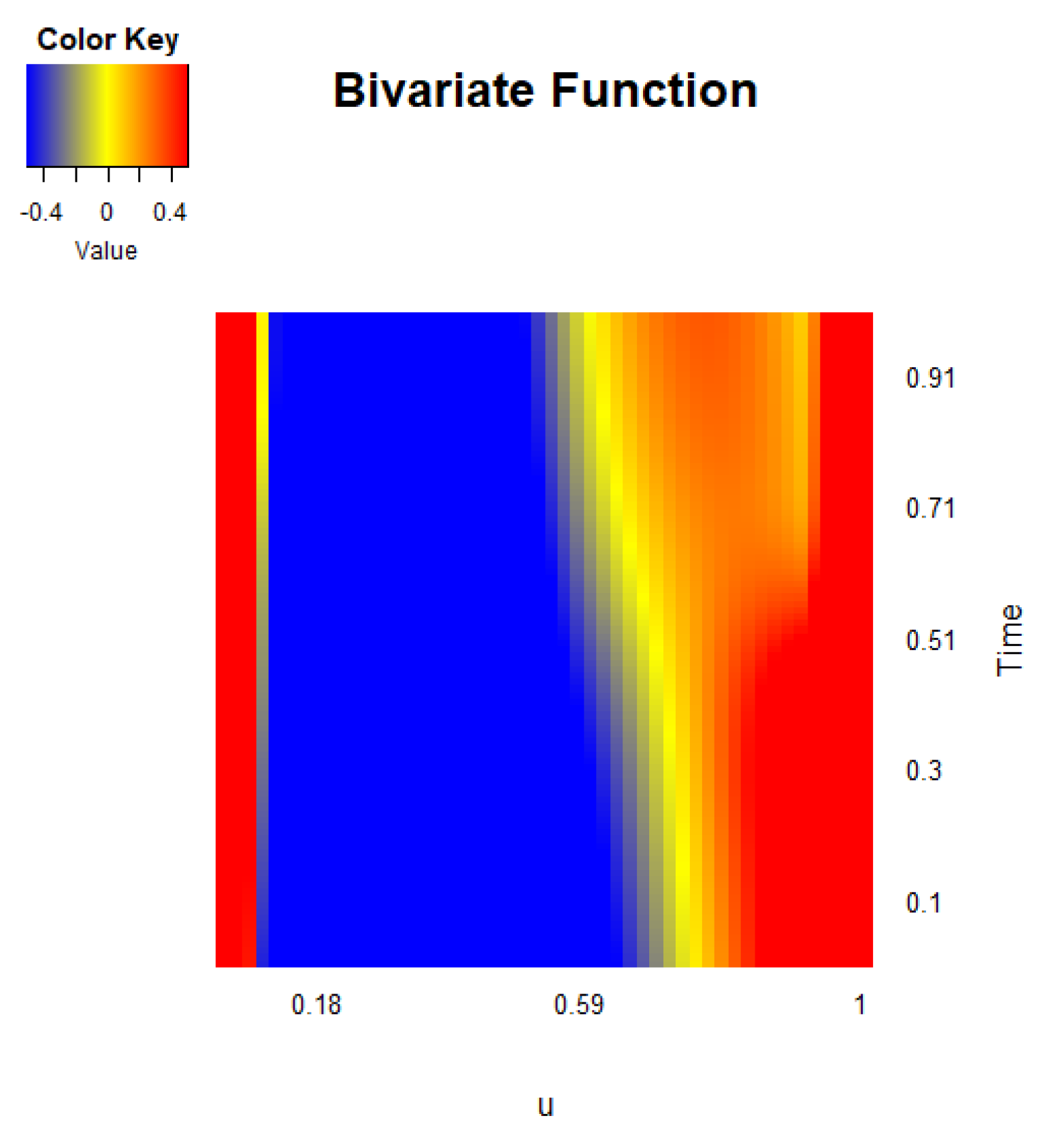

6.1. COVID-19 Data

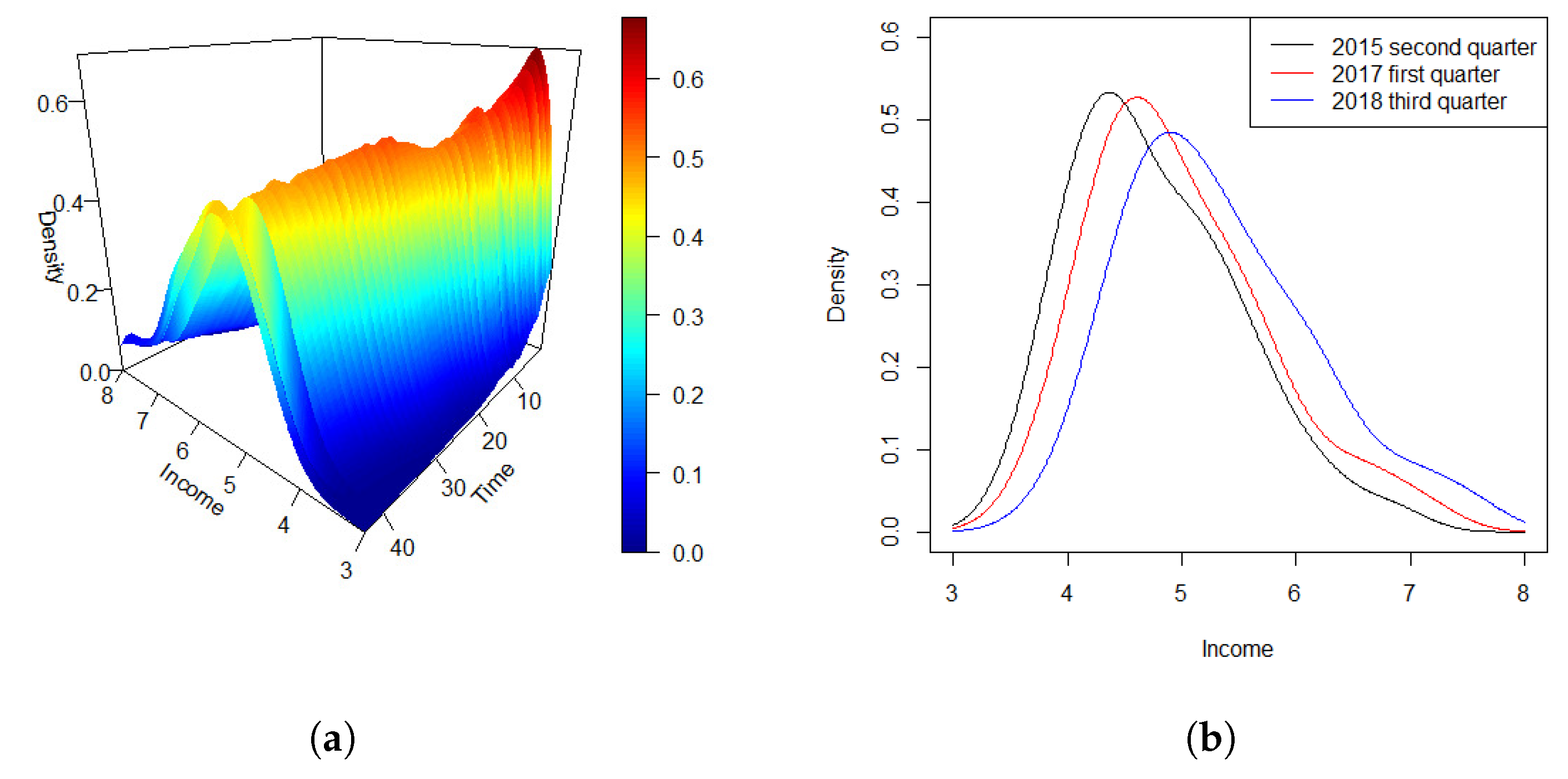

6.2. USA Income Data

7. Discussion

Appendix A

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Berhoune, K.; Bensmain, N. . Sieves estimator of functional autoregressive process. Statistics and Probability Letters 2018, 135, 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosq, D. . Linear processes in function spaces: theory and applications. Springer Science & Business Media, New York, 2000.

- Chen, Y.; Chua, W. S.; Hardle, W. Forecasting limit order book liquidity supply-demand curves with functional autoregressive dynamics. Quantitative Finance 2019, 19(9), 1473–1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Li, B. . An adaptive functional autoregressive forecast model to predict electricity price curves. Journal of Business and Economic Statistics 2017, 35(3), 371–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Lin, Z.; Müller, H. . Wasserstein regression. Journal of the American Statistical Association 2023, 118(542), 869–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniel, R.; David, S.; David, R. . Functional autoregression for sparsely sampled data. Journal of Business and Economic Statistics 2019, 37(1), 97–109. [Google Scholar]

- DeVore, R.; Lorentz, G. . Constructive approximation, Springer Science & Business media, 1993; volume 303.

- Han, K.; Müller, H.; Park, B. . Additive functional regression for densities as responses. Journal of the American Statistical Association 2020, 115(530), 997–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokoszka, P.; Miao, H.; Petersen, A.; Shang, H. L. . Forecasting of density functions with an application to cross-sectional and intraday returns. International Journal of Forecasting 2019, 35, 1304–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokoszka, P.; Reimherr, M. . Determining the order of the functional autoregressive model. Journal of Time Series Analysis 2013, 34, 116–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, A.; Chen, C.; Müller, H. Quantifying and visualizing intraregional connectivity in resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging with correlation densities. Brain Connectivity 2019, 9(1), 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petersen, A.; Müller, H. . Functional data analysis for density functions by transformation to a Hilbert space. The Annals of Statistics 2016, 44(1), 183–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, A.; Müller, H. . Fréchet regression for random objects with Euclidean predictors. The Annals of Statistics 2019, 47(2), 691–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, A.; Banerjee, S.; Kurtek, S.; Narang, S.; Lee, J.; Rao, G.; Martinez, J.; Bharath, K.; Rao, A.; Baladandayuthapani, V. . DEMARCATE: Density-based magnetic resonance image clustering for assessing tumor heterogeneity in cancer. NeuroImage: Clinical 2016, 12, 132–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sen, R.; Ma, C. Forecasting density function: Application in finance. Journal of Mathematical Finance 2015, 5, 433–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, C. . The use of polynomial splines and their tensor products in multivariate function estimation. The Annals of Statistics 1994, 22(1), 118–171. [Google Scholar]

- Talská, R.; Menafoglio, A.; Machalová, J.; Hron, K.; Fiserová, E. Compositional regression with functional response. Computational Statistics & Data Analysis 2018, 123(1), 66–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, G.; Koch, T. . Modeling functional time series and mixed-type predictors with partially functional autoregressions. Journal of Business and Economic Statistics 2022, 0, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Kokoszka, P.; Petersen, A. . Wasserstein autoregressive models for density time series. Journal of Time Series Analysis 2022, 43, 30–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Average RMSEs of Bivariate Varying-Coefficient Additive Functions | |||||

| Sample Size | |||||

| T | n | Initial | Improved | Initial | Improved |

| 50 | 50 | 0.2247 | 0.1848 | 0.2139 | 0.1785 |

| 100 | 0.1759 | 0.1325 | 0.1844 | 0.1521 | |

| 100 | 50 | 0.1826 | 0.1471 | 0.1732 | 0.1354 |

| 100 | 0.1431 | 0.1164 | 0.1319 | 0.1057 | |

| Average SD and Bias of Bivariate Varying-Coefficient Additive Functions | |||||||||

| Sample Size | |||||||||

| Initial | Improved | Initial | Improved | ||||||

| T | n | SD | Bias | SD | Bias | SD | Bias | SD | Bias |

| 50 | 50 | 0.205 | 0.147 | 0.168 | 0.104 | 0.219 | 0.137 | 0.183 | 0.117 |

| 100 | 0.179 | 0.122 | 0.142 | 0.093 | 0.196 | 0.128 | 0.164 | 0.095 | |

| 100 | 50 | 0.174 | 0.136 | 0.151 | 0.082 | 0.187 | 0.131 | 0.158 | 0.086 |

| 100 | 0.133 | 0.099 | 0.112 | 0.057 | 0.153 | 0.111 | 0.129 | 0.061 | |

| Null Hypothesis | |||||||

| Alternative Hypothesis | |||||||

| Sample Size | Significance Level | Significance Level | Significance Level | ||||

| T | n | 0.05 | 0.1 | 0.05 | 0.1 | 0.05 | 0.1 |

| 50 | 50 | 0.893 | 0.962 | 0.787 | 0.846 | 0.082 | 0.134 |

| 100 | 0.931 | 0.985 | 0.824 | 0.893 | 0.073 | 0.125 | |

| 100 | 50 | 0.942 | 0.972 | 0.821 | 0.881 | 0.071 | 0.121 |

| 100 | 0.985 | 1.000 | 0.889 | 0.935 | 0.064 | 0.113 | |

| Average RMSEs of Bivariate Varying-Coefficient Additive Functions | |||||

| Sample Size | |||||

| T | n | Initial | Improved | Initial | Improved |

| 50 | 50 | 0.2739 | 0.2438 | 0.2691 | 0.2235 |

| 100 | 0.2264 | 0.1852 | 0.2157 | 0.1809 | |

| 100 | 50 | 0.2136 | 0.1817 | 0.2232 | 0.1761 |

| 100 | 0.1729 | 0.1263 | 0.1816 | 0.1224 | |

| Null Hypothesis | ||

| Alternative Hypothesis | ||

| P-value | 0.000 | 0.194 |

| Null Hypothesis | |||

| Alternative Hypothesis | |||

| P-value | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.436 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).