Submitted:

11 July 2025

Posted:

14 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

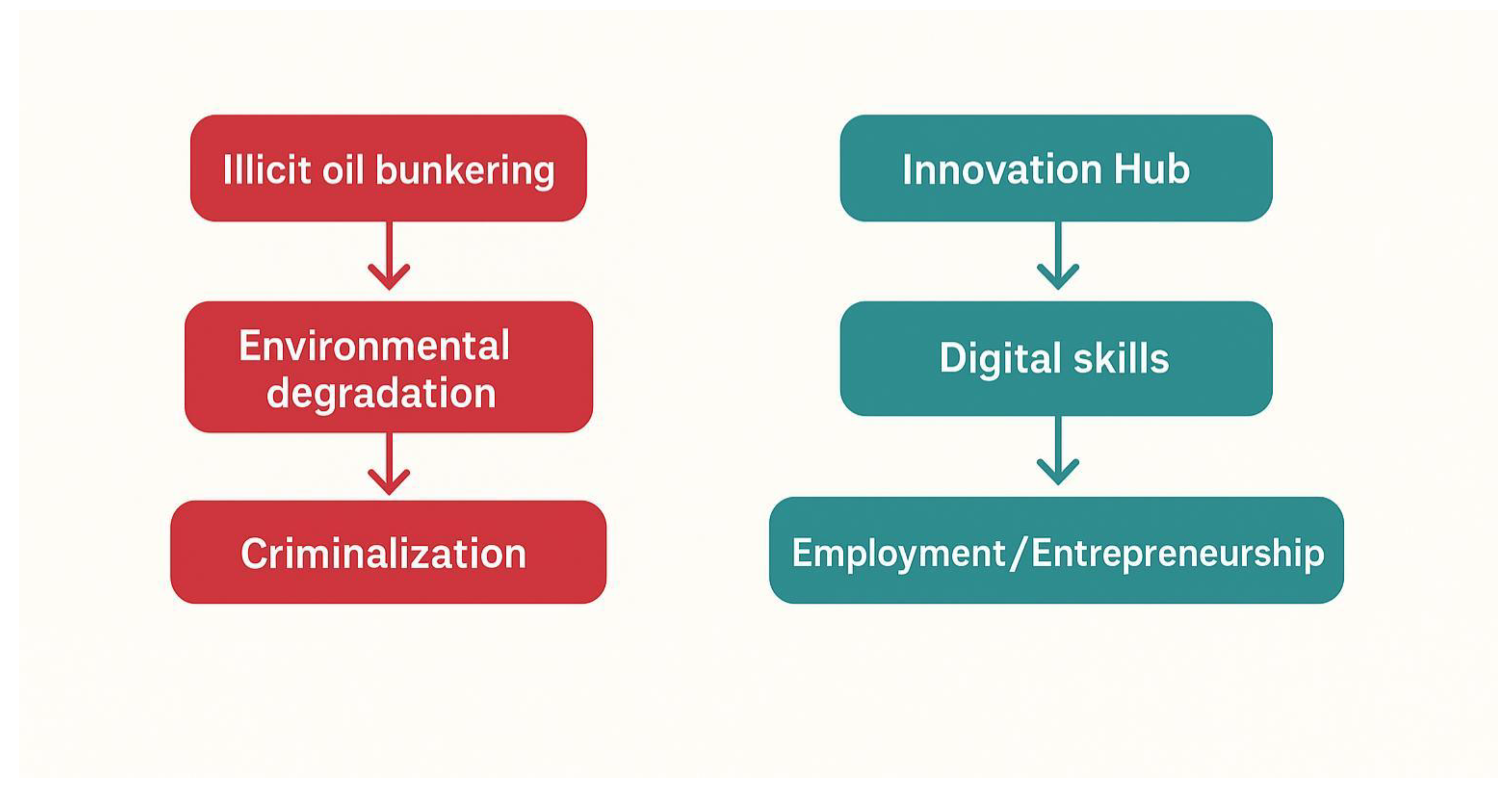

Introduction: Oil Wealth, Wasted Youth

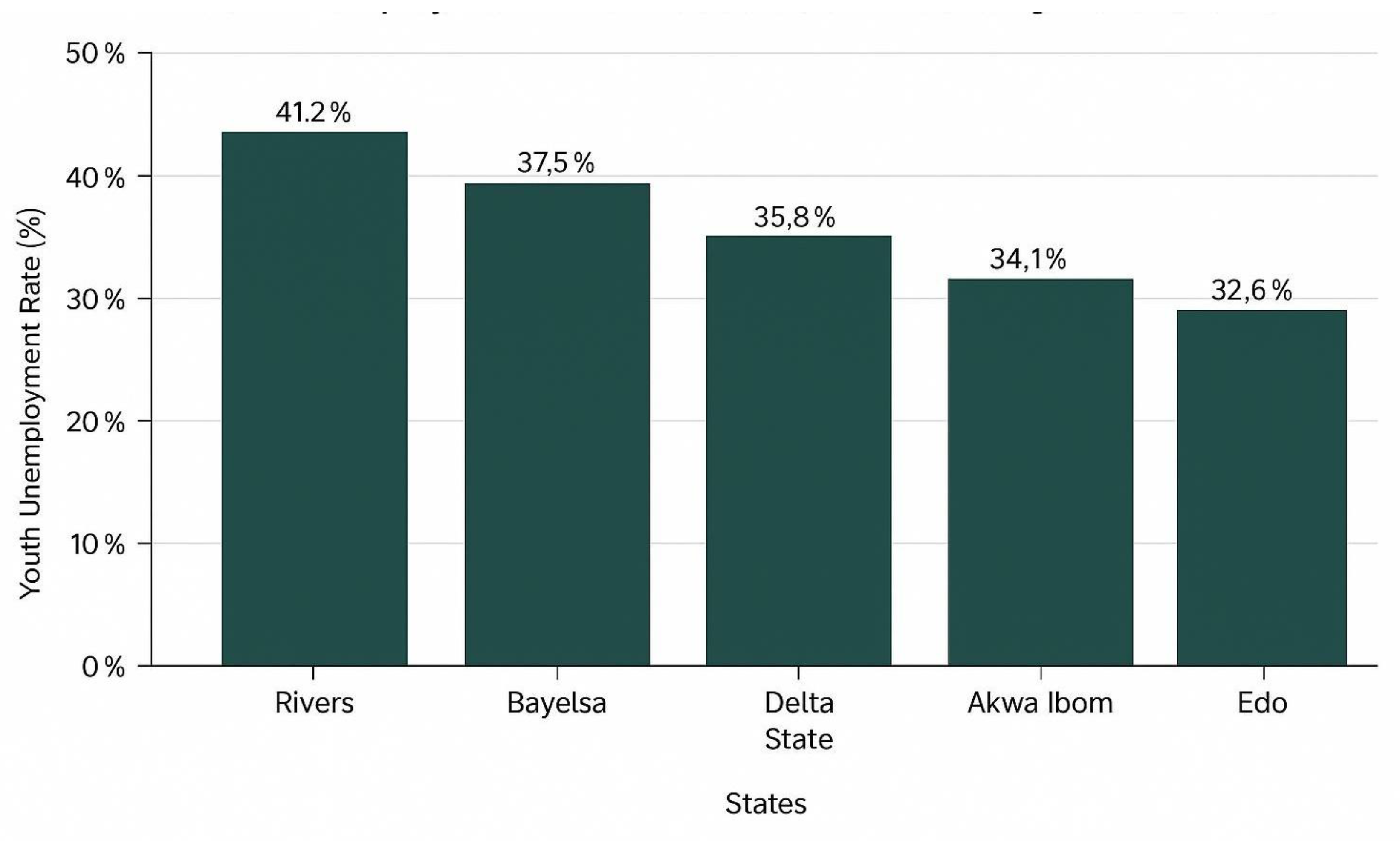

Youth Crisis in Rivers State

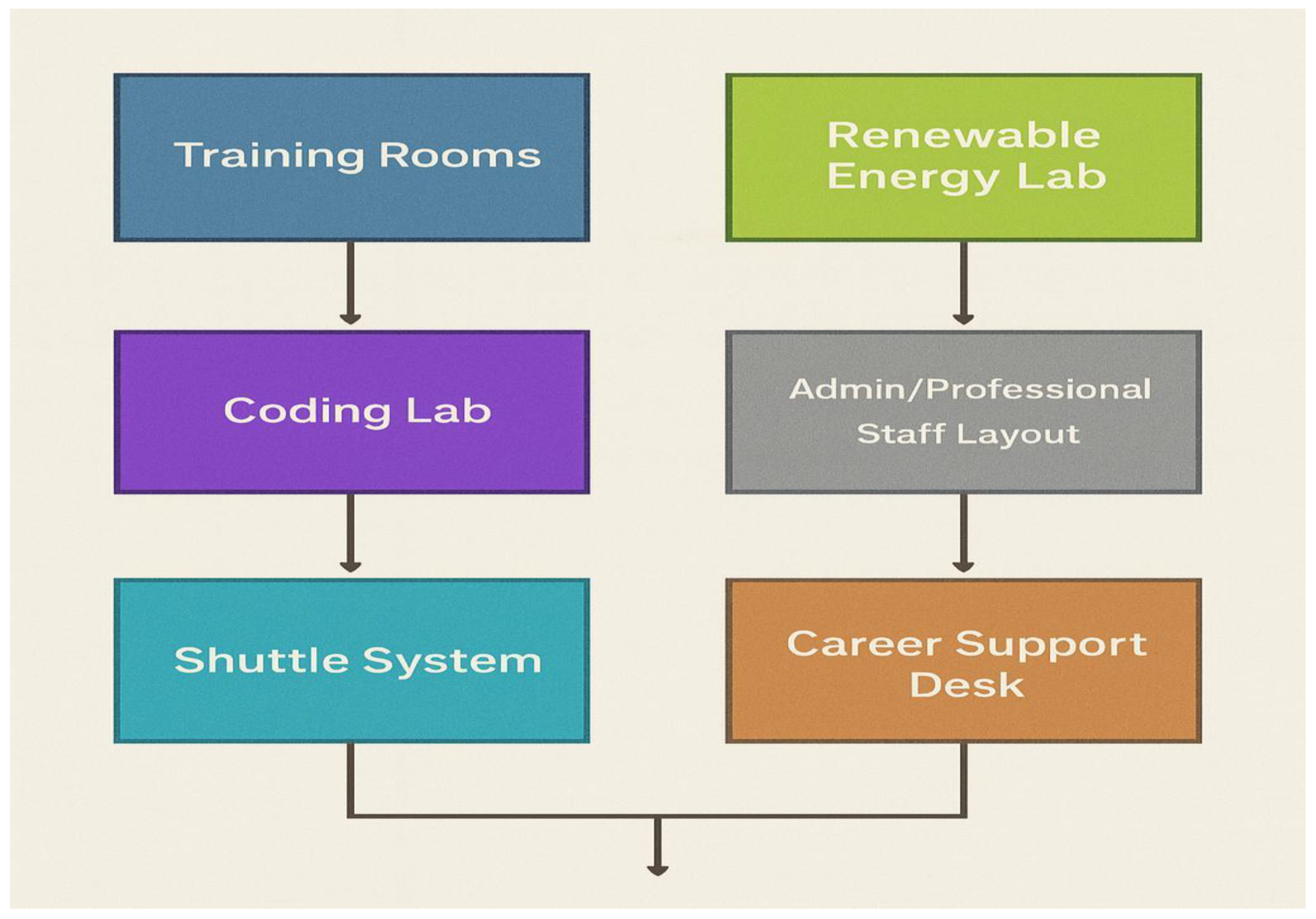

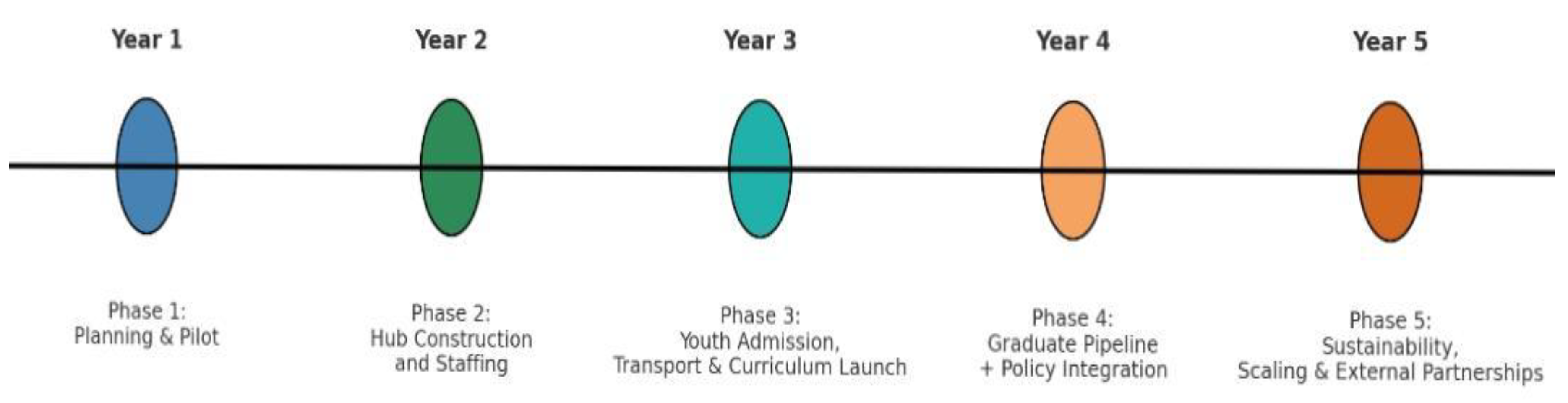

Innovation Hubs: Vision and Structure

- a)

- Full-stack web and mobile development

- b)

- Blockchain development and smart contracts (e.g., Ethereum, Solana)

- c)

- Cryptocurrency and DeFi literacy (wallets, staking, DAO governance, Airdrops)

- d)

- Solar photovoltaic (PV) installation and maintenance

- e)

- Digital freelancing, marketing, and entrepreneurship.

Logistics, Access, and Incentives

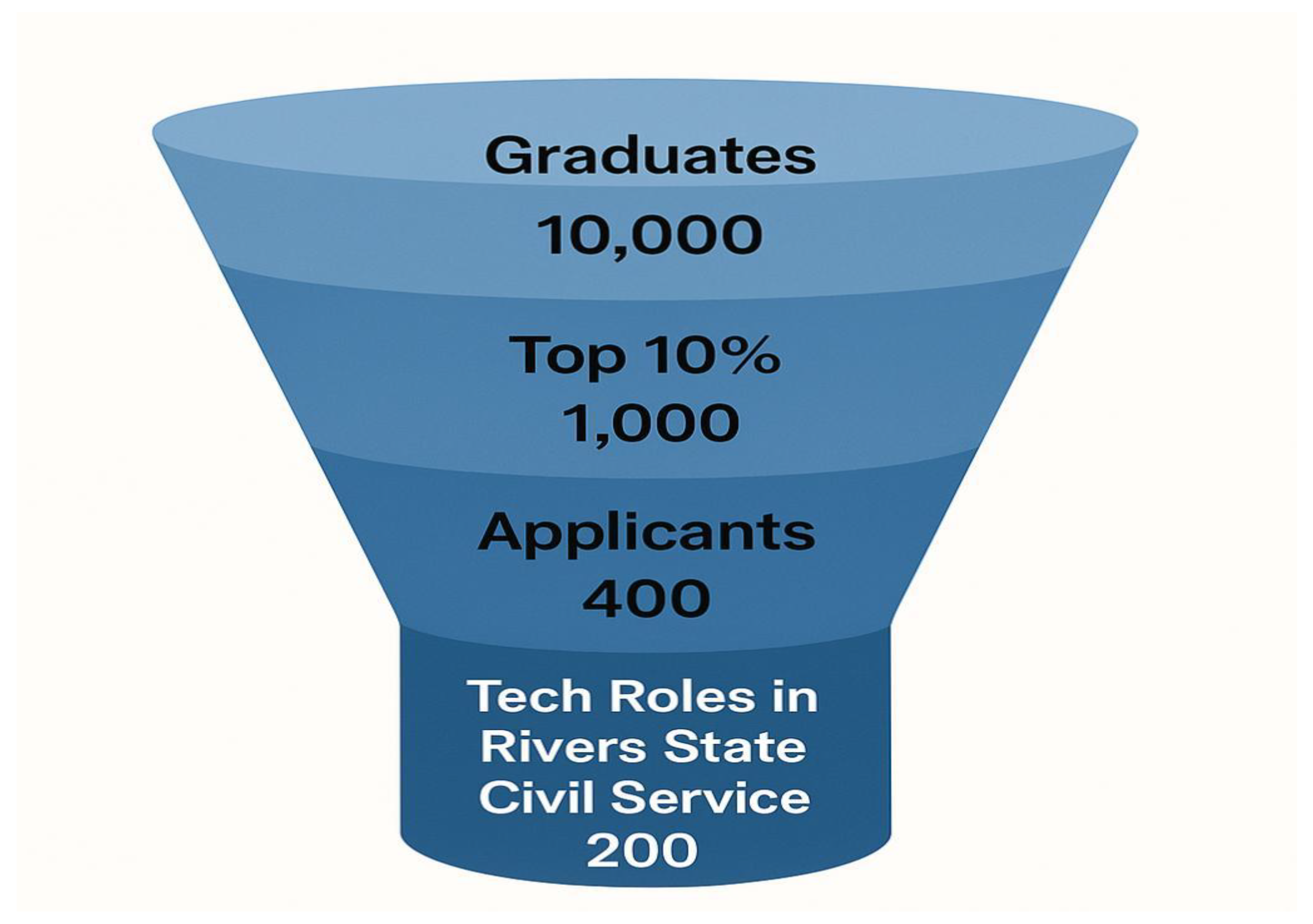

Staffing, Graduation, and Job Paths

Policy Recommendations and Expected Impact

- Allocate 10% of the Rivers State Youth Empowerment Fund to the development and operation of the hubs annually (BudgIT, 2023).

- Legislate continuity, mandating future administrations to sustain the program through a dedicated Innovation and Digital Economy Act (YIAGA Africa, 2022).

- Deploy a blockchain dashboard for real-time monitoring of enrollment, stipend disbursement, and graduate employment outcomes (World Economic Forum, 2020).

- Partner with tech giants, NGOs, and development banks for co-funding, certification, and mentorship support (ITU, 2021).

- a)

- A projected 80% reduction in youth involvement in bunkering over 3 years

- b)

- Over 50,000 new job pathways created within 5 years

- c)

- Increased civil service efficiency with tech-literate employees

- d)

- Strengthened local economies through grassroots innovation

| LGA Name | No. of Hubs | Estimated Youth Served Per Year | Nearest Transport Nodes | Nearby Tertiary Institutions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Port Harcourt | 3 | 2,000 | Waterlines, Rumuola, Eleme Junction | Rivers State University, Uniport |

| Obio-Akpor | 3 | 2,000 | Rumuokoro, Choba, GRA | Uniport, Ignatius Ajuru University |

| Ikwerre | 3 | 1,200 | Elele Junction | Uniport Satellite Campus |

| Etche | 3 | 900 | Okehi, Igboh | Federal Polytechnic, Etche (planned) |

| Ahoada East | 3 | 1,000 | Ahoada Motor Park | Western Delta University (nearby) |

| Ahoada West | 3 | 900 | Joinkrama | - |

| Ogba/Egbema/Ndoni | 3 | 1,200 | Omoku Junction | - |

| Bonny | 3 | 1,000 | Bonny Jetty | - |

| Okrika | 3 | 800 | Okochiri, Navy Road | - |

| Opobo/Nkoro | 3 | 700 | Minima Waterfront | - |

| Gokana | 3 | 1,000 | Bori Junction | Ken Saro-Wiwa Polytechnic |

| Khana | 3 | 1,000 | Saakpenwa | Ken Saro-Wiwa Polytechnic (Bori Campus) |

| Tai | 3 | 700 | Kpite, Nonwa | - |

| Oyigbo | 3 | 900 | Kom-Kom, Afam | - |

| Eleme | 3 | 1,100 | Refinery Road | - |

| Andoni | 3 | 800 | Ngo Town | - |

| Ogu/Bolo | 3 | 600 | Bolo Town | - |

| Akuku-Toru | 3 | 750 | Abonnema Waterfront | - |

| Asari-Toru | 3 | 750 | Buguma Waterfront | - |

| Degema | 3 | 700 | Tombia | - |

| Abua/Odual | 3 | 800 | Abua Central | - |

| Emuoha | 3 | 1,000 | Emuoha Junction | - |

| Omuma | 3 | 600 | Eberi | - |

Conclusion: Silicon Delta Vision

References

- Adeola, G. N.; Olayemi, A. Unemployment and insecurity in Nigeria: A critical appraisal. Journal of Social Sciences 2019, 45(2), 134–148. [Google Scholar]

- Adewumi, O.; Okafor, U.; James, A. Nigeria’s digital skill gap and its impact on youth employability. African Journal of Science, Technology & Innovation 2023, 15(1), 45–59. [Google Scholar]

- AfDB. Jobs for Youth in Africa Strategy (2022–2025); African Development Bank Group, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Aghedo, I.; Osumah, O. Insurgency in Nigeria: A comparative study of Niger Delta and Boko Haram uprisings. Journal of Asian and African Studies 2015, 50(2), 208–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aina, L.; Salau, S. Digital workforce readiness in Nigerian higher education. Journal of African Educational Research 2021, 11(3), 98–112. [Google Scholar]

- Akinola, A. O. Youth engagement and political participation in Nigeria: Trends, challenges, and prospects. African Journal of Politics and Society 2020, 13(1), 22–41. [Google Scholar]

- Auty, R. M. Sustaining Development in Mineral Economies: The Resource Curse Thesis. Routledge, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Bada, A.; Madon, S. The role of ICTs in community development in Africa: Lessons from SW Nigeria. Information Technology for Development 2006, 12(3), 201–216. [Google Scholar]

- British Council. Nigeria Creative Economy Report; British Council: London, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- BudgIT. State of States: Subnational Budget Transparency in Nigeria; BudgIT Foundation: Lagos, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Chukwuemeka, E. Youth empowerment and sustainable development in the Niger Delta. African Journal of Development Studies 2020, 10(1), 24–36. [Google Scholar]

- Egbula, M.; Eronmhonsele, E. Renewable energy adoption in the Niger Delta: Barriers and opportunities. Energy Policy Journal 2021, 35(4), 142–158. [Google Scholar]

- Foundation, Ethereum. Ethereum Developer Documentation. 2022. https://ethereum.org/en/developers/docs/.

- GSMA. Mobile Internet Skills Training Toolkit: Lessons from Digital Skills Programs in Africa; GSMA: London, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Ibaba, S. I.; Ikelegbe, A. The amnesty programme and the resolution of the Niger Delta crisis. Journal of Third World Studies 2010, 27(1), 83–105. [Google Scholar]

- ILO. Skills Development for Youth Employment in Africa; International Labour Organization: Geneva, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- International Telecommunication Union (ITU). Partnerships for Digital Skills Development in Africa; ITU: Geneva, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- International Telecommunication Union (ITU). Digital Skills in Sub-Saharan Africa: From Policy to Practice; ITU: Geneva, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- IRENA. Renewable Energy and Jobs–Annual Review 2021; International Renewable Energy Agency: Abu Dhabi, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Kazeem, Y. Nigeria’s youth are leading a remote work revolution. Quartz Africa. 2020. https://qz.com/africa.

- National Bureau of Statistics. Labour Force Statistics: Unemployment and Underemployment Report; Abuja: NBS, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Ndemo, B.; Weiss, T. Digital Kenya: An Entrepreneurial Revolution in the Making; Palgrave Macmillan, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Nwachukwu, T.; Mordi, F. Digital infrastructure and employment creation in Nigeria. Nigerian Economic Review 2022, 34(2), 87–103. [Google Scholar]

- Obi, C. Nigeria's oil wealth and the crisis of development. Journal of Contemporary African Studies 2021, 39(2), 151–167. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Blockchain for Inclusive Growth: The Case of Emerging Markets; OECD Publishing: Paris, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Olanrewaju, F. Education and youth unemployment in Nigeria: The missing link. Journal of African Policy Research 2019, 11(3), 58–72. [Google Scholar]

- Oseni, T.; Briggs, J. Blockchain technology and the future of digital governance in Nigeria. Nigerian Journal of Public Policy and Administration 2021, 8(2), 75–88. [Google Scholar]

- Oyeyemi, T.; Okoro, U. Digital skills for youth empowerment in Nigeria: Barriers and opportunities. Nigerian Journal of Educational Technology 2020, 5(2), 44–56. [Google Scholar]

- Tapscott, D.; Tapscott, A. Blockchain Revolution: How the Technology Behind Bitcoin Is Changing Money, Business, and the World; Penguin, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- UNDP. Niger Delta Human Development Report; United Nations Development Programme, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- UNDP. Accelerating Digital Transformation in Africa: Policy Brief; United Nations Development Programme: New York, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Youth and Skills: Putting Education to Work; UNESCO: Paris, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Upwork. Freelancing in 2023: Global Skills Trends. 2023. https://www.upwork.com/research/.

- World Bank. Harnessing Digital Technologies for Inclusion in Africa; World Bank Group: Washington, DC, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- World Economic Forum. Blockchain Deployment Toolkit; WEF: Geneva, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- YIAGA Africa. Legislative Reforms and Youth Participation in Governance; YIAGA: Abuja, 2022. [Google Scholar]

| Skill Area | Duration | Certification | Partner Institution/Platform |

|---|---|---|---|

| Full-Stack Web Development | 8 weeks | Yes | ALX, Coursera, or Hub-specific |

| Blockchain & Smart Contracts | 6 weeks | Yes | Ethereum Foundation / Celo Labs |

| Renewable Energy Systems | 6 weeks | Yes | IRENA or Solar Sister Nigeria |

| DeFi Literacy & Wallet Skills | 4 weeks | Badge | Binance Academy / DeFi Africa |

| Freelancing & Digital Skills | 4 weeks | Yes | Upwork/LinkedIn Learning |

| Incentive Type | Description | Delivery Mechanism |

|---|---|---|

| Monthly Stipend | ₦20,000 per student | Blockchain wallet |

| Free Transportation | Hub buses operating on set routes daily | Local driver cooperatives |

| Meal Subsidy | 1 daily meal from local vendors | Meal vouchers |

| Certification Grants | Paid exam fees for partner certification programs | Program-administered |

| Stage | Percentage | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Enrolled Youth | 100% | All admitted students |

| Completed Training | 85% | Accounts for dropout rate and attendance |

| Certified Graduates | 75% | Those who pass assessments |

| Top Performers | 20% | Highest scorers with leadership potential |

| Civil Service Placement | 10% | Absorbed into Rivers State tech departments |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).