1. Introduction

The Paris Agreement stands as a landmark global commitment to combat climate change, yet its success hinges on an unprecedented mobilization of capital. For emerging market and developing economies (EMDEs), the challenge is particularly acute. These nations, often the most vulnerable to climate impacts, face an immense investment gap to fund their climate action plans, known as Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs). The annual climate finance needs of EMDEs alone are estimated at USD 400 billion, a figure that dwarfs the capacity of domestic public finance and makes the attraction of international private capital essential (Climate Policy Initiative, 2024).In this context, sovereign green bonds have emerged as a vital instrument for governments to finance green infrastructure and signal national commitment to climate goals (Legal500, 2025). On June 25, 2024, the Dominican Republic launched its inaugural sovereign green bond, raising USD 750 million (LatinFinance, 2024). The transaction was met with overwhelming demand, generating an order book six times the size of the offering and achieving an estimated 15-basis-point pricing advantage, or “greenium,” compared to a conventional bond (World Bank, 2025).This initial triumph, however, exists within a profoundly challenging context. The first is a problem of scale. The USD 750 million raised represents less than 5% of the over USD 17.6 billion the Dominican Republic estimates it needs to fully implement its 2030 NDC targets (Dominican Republic, 2020). The second, and more insidious, challenge is the systemic threat of “greenwashing”—the deceptive promotion of an organization’s environmental credentials (Baker McKenzie, 2019). Research has shown that a significant portion of corporate green bond issuers exhibit a deterioration in environmental performance after issuance, a practice that erodes investor trust and threatens to erase the greenium (Hong Kong Monetary Authority, 2022).The existing literature has extensively covered the importance of pre-issuance frameworks, but a critical gap remains in analyzing how emerging market sovereigns can institutionalize robust post-issuance transparency and verification systems. This paper argues that for the Dominican Republic to translate its successful debut into a scalable strategy, it must proactively move beyond voluntary principles to a system of proven, data-driven impact. The central thesis is that a dedicated digital platform—a “Green Bond Impact Tracker”—is a necessary piece of strategic national infrastructure to ensure radical post-issuance transparency, mitigate greenwashing risk, and thereby sustain and expand access to the preferential financing required to fund its green transition.

2. Literature Review

The Dominican Republic’s entry into the green bond market occurs at a pivotal moment of maturation, opportunity, and risk for sustainable finance globally. A review of the relevant literature reveals four interconnected themes that define this landscape: the catalytic role of sovereign green bonds in emerging markets, the volatile economics of the “greenium,” the systemic market failure of greenwashing, and the emergence of digital technologies as a potential solution.

2.1. The Rise of Sovereign Green Bonds in Emerging Markets

While corporations and multilateral banks were early adopters, sovereign green bond issuance has been transformative, signaling strong government commitment to climate policies and stimulating broader market development (International Monetary Fund, 2024). This trend is visible across numerous emerging markets. India, for instance, established a Green Finance Working Committee to oversee its program, issuing sovereign green bonds to fund public sector projects in renewable energy and clean transportation (World Bank, 2023). Malaysia leveraged its leadership in Islamic finance to pioneer the “green sukuk,” integrating its Sustainable and Responsible Investment (SRI) Framework with global standards like the ICMA Green Bond Principles (International Finance Corporation, 2018).A crucial finding from recent research by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) is that sovereign issuance has a powerful catalytic effect on the domestic private market (International Monetary Fund, 2024). Analysis suggests that after a sovereign debut, both the number and volume of corporate green bond issuances increase significantly. This occurs through a “demonstration effect” that raises awareness, a “signaling effect” of policy commitment, and the establishment of a pricing benchmark that makes it easier for corporates to issue their own green debt (International Monetary Fund, 2024).

2.2. The Economics and Volatility of the “Greenium”

A primary attraction of green bonds is the potential to secure a “greenium”—a yield discount compared to an equivalent conventional bond (Karpf & Mandel, 2018, as cited in IJNRD, 2024). This premium is driven by factors including immense investor demand to meet ESG mandates and a perception of lower risk (European Central Bank, 2022). For a sovereign issuer, even a small greenium can translate into millions in public debt savings.

However, a critical development is the increasing volatility and erosion of this pricing advantage. Recent analysis shows that while global GSSS (Green, Social, Sustainability, and Sustainability-Linked) bond issuance hit a record high in 2024, the global greenium more than halved (Amundi, 2025). For emerging markets specifically, the greenium “effectively disappeared in 2024 as supply caught up with demand” (Amundi, 2025, p. 5). This trend suggests that simply labeling a bond “green” is no longer sufficient to guarantee preferential pricing. In an increasingly crowded and skeptical market, the greenium is evolving into an earned premium for demonstrable credibility, selectively rewarding issuers who provide superior transparency and governance (European Central Bank, 2022).

2.3. Greenwashing as a Market Failure

The primary threat to the integrity of the green bond market is greenwashing, a market failure rooted in information asymmetry where issuers possess more knowledge about their environmental performance than investors (IMF, 2022). This can lead to a misallocation of capital toward projects with negligible environmental impact, undermining the purpose of green finance (Emerald, 2024). The prevalence of this risk is not merely theoretical. A landmark 2022 study by the Hong Kong Monetary Authority (HKMA) found that approximately one-third of corporate green bond issuers exhibited a worse environmental performance after their initial green bond issuance (Hong Kong Monetary Authority, 2022). The market, however, is not passive. The same study found that investors penalize firms perceived as greenwashing, making it more difficult and costly for them to re-issue green bonds (Hong Kong Monetary Authority, 2022). The current market structure relies heavily on the voluntary ICMA Green Bond Principles (GBP), which are guidelines, not legally binding contracts, creating an “enforcement gap” that underscores the need for systems that move beyond promises to proof (Baker McKenzie, 2019).

2.4. Digital MRV for Climate Finance Integrity

The technological and policy response to this challenge is the emergence of Digital Measurement, Reporting, and Verification (Digital MRV) systems. These systems represent a paradigm shift from static, manual reporting to dynamic, automated, and near-real-time data frameworks. By leveraging technologies such as IoT, satellite imagery, and AI, Digital MRV aims to provide a more accurate, efficient, and trustworthy account of climate action and its impacts (Mungroo, 2024).This technological evolution is converging with a major shift in the international climate policy landscape. Under the Paris Agreement, the Enhanced Transparency Framework (ETF) requires all signatory countries to submit Biennial Transparency Reports (BTRs) starting from the end of 2024 (UNFCCC, n.d.-c). These reports must provide comprehensive information on a country’s greenhouse gas inventory, its progress toward achieving its NDC targets, and climate finance flows (UNDP, 2025). This creates a powerful convergence of incentives: the financial market demands verifiable data to mitigate greenwashing risk, while the international climate regime legally obligates countries to produce the same kind of data for their BTRs. A national Digital MRV platform is therefore a dual-use strategic asset, satisfying the due diligence requirements of global capital markets and the international reporting obligations of the state (UNDP, 2025).

3. Methodology

This study employs a qualitative, single-case study analysis methodology. This approach is well-suited for an in-depth investigation of a single, bounded case to understand a complex, real-world problem in its contemporary context (UAGC Writing Center, 2025). The case is the Dominican Republic’s June 2024 sovereign green bond issuance. The analytical process follows a structured, problem-solution format, conducted through four stages:

Case Examination: A review of primary and secondary source documents, including the official “Green, Social, and Sustainable Bond Framework,” the bond’s legal Prospectus, the pre-issuance allocation report, and post-issuance analyses from partners like the World Bank and the Global Green Growth Institute (Dirección General de Crédito Público, 2024a; World Bank, 2025).

Problem Identification: Juxtaposing the success of the issuance with two countervailing forces: the scale of the national climate finance gap detailed in the country’s NDC, and the threat of greenwashing to the long-term sustainability of the program (Dominican Republic, 2020; Hong Kong Monetary Authority, 2022).

Literature Synthesis: Situating the case within the broader academic and policy literature on the global sustainable finance market, including the ICMA Green Bond Principles, the economics of the “greenium,” evidence of greenwashing, and the evolution of Digital MRV systems (Hong Kong Monetary Authority, 2022; International Monetary Fund, 2023; Sustainability Directory, 2025).

Solution Proposal and Recommendation Formulation: Proposing a specific, technology-based solution—the Green Bond Impact Tracker—based on the synthesis of the case analysis and literature review, and formulating actionable recommendations for key stakeholders.

4. Results

The empirical foundation of this analysis rests on a detailed deconstruction of the Dominican Republic’s inaugural sovereign green bond. The data reveal a highly successful financial transaction underpinned by a robust governance strategy.

4.1. Anatomy of a Landmark Transaction

The June 2024 issuance was a landmark event. The government raised USD 750 million with a 12-year tenor and a coupon of 6.6% (World Bank, 2025). The offering was met with exceptional investor demand, attracting an order book of approximately USD 4.5 billion, a six-fold oversubscription (World Bank, 2025). Critically, this translated into an estimated “greenium” of 15 basis points, a tangible public saving that validates the economic case for a credible green financing strategy (World Bank, 2025).

Table 1.

Dominican Republic Sovereign Green Bond - Key Issuance Details.

Table 1.

Dominican Republic Sovereign Green Bond - Key Issuance Details.

| Metric |

Detail |

| Bond Name |

Dominican Republic Sovereign Green Bond |

| Issuance Date |

June 25, 2024 |

| Amount Issued |

USD 750,000,000 |

| Maturity Date |

June 1, 2036 (12-year tenor) |

| Coupon Rate |

6.600% |

| Oversubscription Rate |

6 times |

| Greenium (Cost Saving) |

Approx. 15 basis points vs. conventional bond |

| Governing Framework |

Green, Social, and Sustainable Bond Framework |

| Framework Alignment |

ICMA Green Bond Principles (GBP) |

| Second Party Opinion |

S&P Global Ratings |

| Source: Compiled from World Bank (2025) and Dirección General de Crédito Público (2024b). |

4.2. The Governance Architecture of Credibility

The market success was the result of a deliberate governance strategy designed to build investor trust. Key pillars included: a high-level Thematic Bonds Commission; a comprehensive “Green, Social, and Sustainable Bond Framework” aligned with the ICMA’s Green Bond Principles; an independent Second Party Opinion (SPO) from S&P Global Ratings; and extensive technical assistance from the World Bank and the Global Green Growth Institute (GGGI) (World Bank, 2025).4.3 The Strategic Context: NDC Alignment and the Financing Chasm

The bond program is explicitly designed to finance the nation’s NDC. The pre-issuance allocation report details how proceeds are allocated to eligible green categories that directly align with NDC priorities (Dirección General de Crédito Público, 2024a).

Table 2.

Indicative Allocation of Proceeds for Inaugural Green Bond.

Table 2.

Indicative Allocation of Proceeds for Inaugural Green Bond.

| Eligible Green Category |

Indicative Allocation Range (%) |

Indicative Allocation (USD Million) |

| Renewable Energy |

56% - 80% |

$420 - $600 |

| Low Carbon Transport |

10% - 24% |

$75 - $180 |

| Efficient and Resilient Water & Wastewater Management |

10% - 16% |

$75 - $120 |

| Natural Resources, Land Use, and Protected Marine Areas |

0% - 4% |

$0 - $30 |

| Source: Adapted from Dirección General de Crédito Público (2024a). |

However, the scale of the financing challenge is immense. The Dominican Republic’s 2020 NDC outlines a financial requirement of approximately USD 17.6 billion for the 2021-2030 period (Dominican Republic, 2020). The USD 750 million raised covers less than 5% of this need, highlighting the imperative to create a scalable, long-term financing program.

5. Discussion

The analysis yields critical insights into the future of sovereign climate finance. The “greenium” appears to be a function of actively managed trust, and a digital transparency platform can serve as a dual-use instrument of both economic and climate policy, catalyzing a national sustainable finance ecosystem.

5.1. Interpreting the “Dominican Greenium”

The achievement of a 15-basis-point greenium is a central finding, as it runs counter to the prevailing market trend of a shrinking premium for emerging market issuers (Amundi, 2025). This should be interpreted as a direct financial reward for the country’s substantial investment in a credible, transparent pre-issuance governance structure. In a market wary of greenwashing, the comprehensive governance architecture effectively reduced information asymmetry and perceived risk for investors (Hong Kong Monetary Authority, 2022). The resulting greenium was not a gift, but an earned premium on credibility. This reframes the greenium as a valuable and fragile asset that must be actively protected through unwavering post-issuance transparency.

5.2. The Tracker as a Dual-Use Policy Instrument

The proposed Green Bond Impact Tracker is the mechanism designed to protect this earned credibility. For the Ministry of Finance, the Tracker is an instrument of prudent public debt management, functioning as an “insurance policy” for the greenium. By providing a continuous, verifiable record of impact, it mitigates greenwashing risk and preserves lower borrowing costs. For the Ministry of Environment, the Tracker is a powerful tool for policy execution and international compliance. The data required for the mandatory Biennial Transparency Reports (BTRs) under the Paris Agreement’s Enhanced Transparency Framework is precisely the data the Tracker is designed to collect, manage, and verify (UNDP, 2025). This dual-use nature means an investment in the Tracker is an investment in both cheaper financing and more effective climate governance.

5.3. Catalyzing a National Sustainable Finance Ecosystem

The strategic implications extend beyond the public sector. As IMF research has shown, a successful sovereign green bond issuance often has a significant catalytic effect on the private sector (International Monetary Fund, 2024). By designing the Tracker as a multi-tenant “platform-as-a-service,” the government could offer it as shared national infrastructure. Dominican companies seeking to issue their own green bonds could use the Tracker’s standardized frameworks, lowering the barrier to entry, ensuring high-quality reporting across the national market, and accelerating the development of a domestic sustainable finance ecosystem capable of helping close the nation’s climate finance gap.

6. Conclusion

The Dominican Republic’s inaugural sovereign green bond was a resounding success, but this achievement must be viewed as a strategic starting point. The scale of the country’s NDC financing needs demands a transition from a single transaction to a durable financing program. In a global market skeptical of greenwashing, the key to building such a program is the institutionalization of credibility through technology-enabled transparency. The proposed Green Bond Impact Tracker is the central mechanism to achieve this objective. It is an insurance policy against the erosion of the greenium, a management tool for executing climate policy, and a marketing platform to attract the global capital required to fund a sustainable future.

Appendix A. A Blueprint for the Green Bond Impact Tracker

Appendix A.1. Conceptual Framework

The Green Bond Impact Tracker is a proposed digital public good designed to institutionalize transparency for all thematic investments in the Dominican Republic. It is built on a modern, scalable Digital MRV architecture composed of four integrated layers:

Data Aggregation Engine: Ingests and standardizes data from diverse sources, including direct API integration with government financial systems (e.g., SIGEF), secure portals for project implementers, and third-party data from IoT sensors or satellite imagery for independent verification.

Impact Measurement Module: An analytical core that translates raw project data into meaningful impact metrics using a standardized library of Key Performance Indicators (KPIs). It features a calculation engine to quantify impacts (e.g., GHG emissions avoided) and maps these impacts directly to NDC and SDG targets.

Compliance & Reporting Dashboard: A user-facing interface (e.g., built on Power BI or Tableau) providing interactive, role-based visualizations, geospatial maps, progress-to-target gauges, and automated generation of ICMA-compliant allocation and impact reports.

AI-Powered Verification Layer: An advanced module using Natural Language Processing (NLP) and machine learning to scan reports for greenwashing red flags, predict project delays, and detect anomalies in financial or performance data, providing an early warning system to regulators.

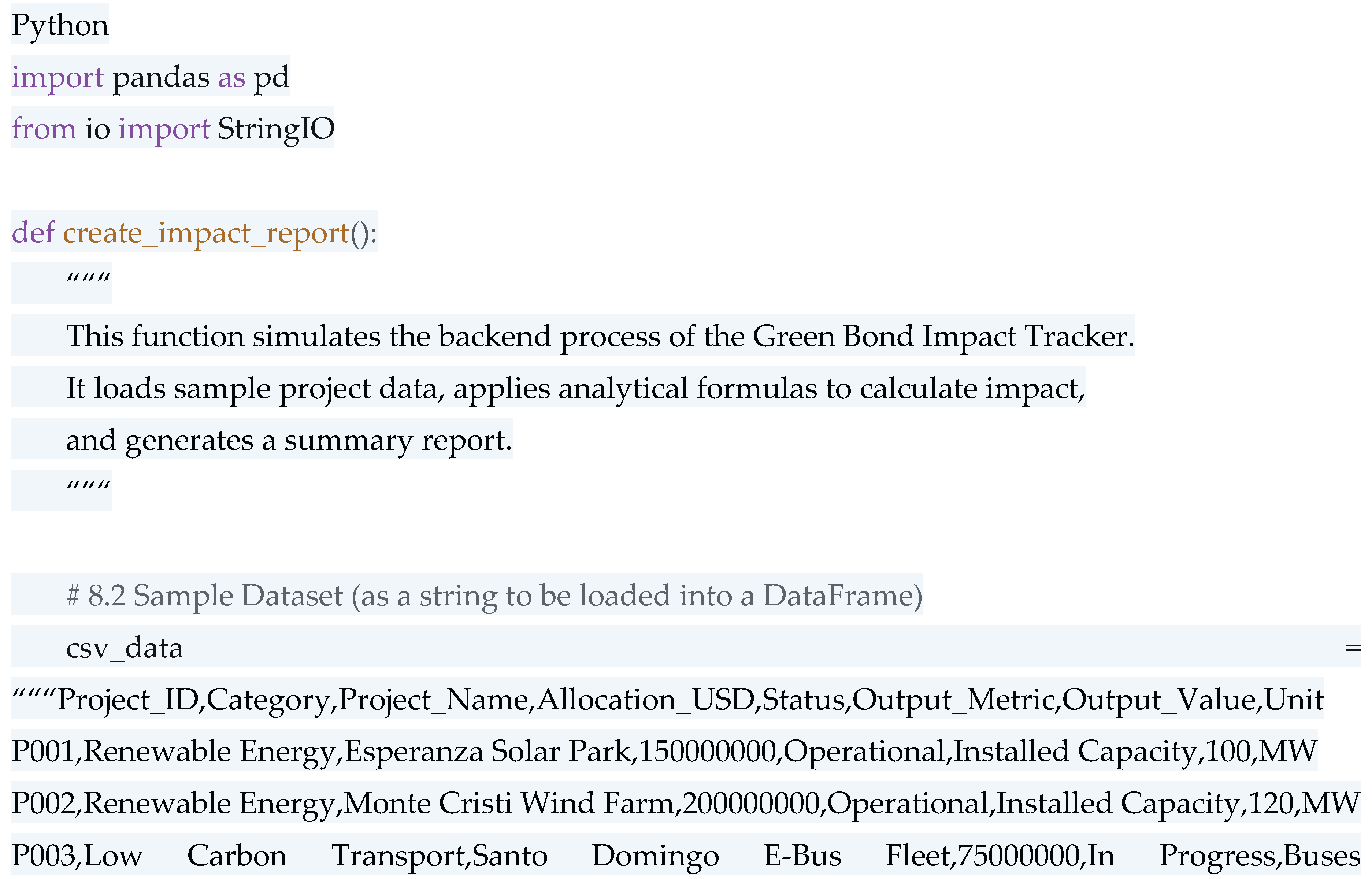

Appendix A.2. Sample Dataset

The following table represents a simplified dataset that would form the basis of the Tracker. It includes project identifiers, allocation amounts, and key output metrics that serve as inputs for impact calculations.

| Project_ID |

Category |

Project_Name |

Allocation_USD |

Status |

Output_Metric |

Output_Value |

Unit |

| P001 |

Renewable Energy |

Esperanza Solar Park |

150000000 |

Operational |

Installed Capacity |

100 |

MW |

| P002 |

Renewable Energy |

Monte Cristi Wind Farm |

200000000 |

Operational |

Installed Capacity |

120 |

MW |

| P003 |

Low Carbon Transport |

Santo Domingo E-Bus Fleet |

75000000 |

In Progress |

Buses Deployed |

50 |

Buses |

| P004 |

Water Management |

Yaque del Norte Basin Restoration |

50000000 |

Operational |

Area Restored |

1500 |

Hectares |

| P005 |

Renewable Energy |

San Juan Solar Farm |

120000000 |

In Progress |

Installed Capacity |

80 |

MW |

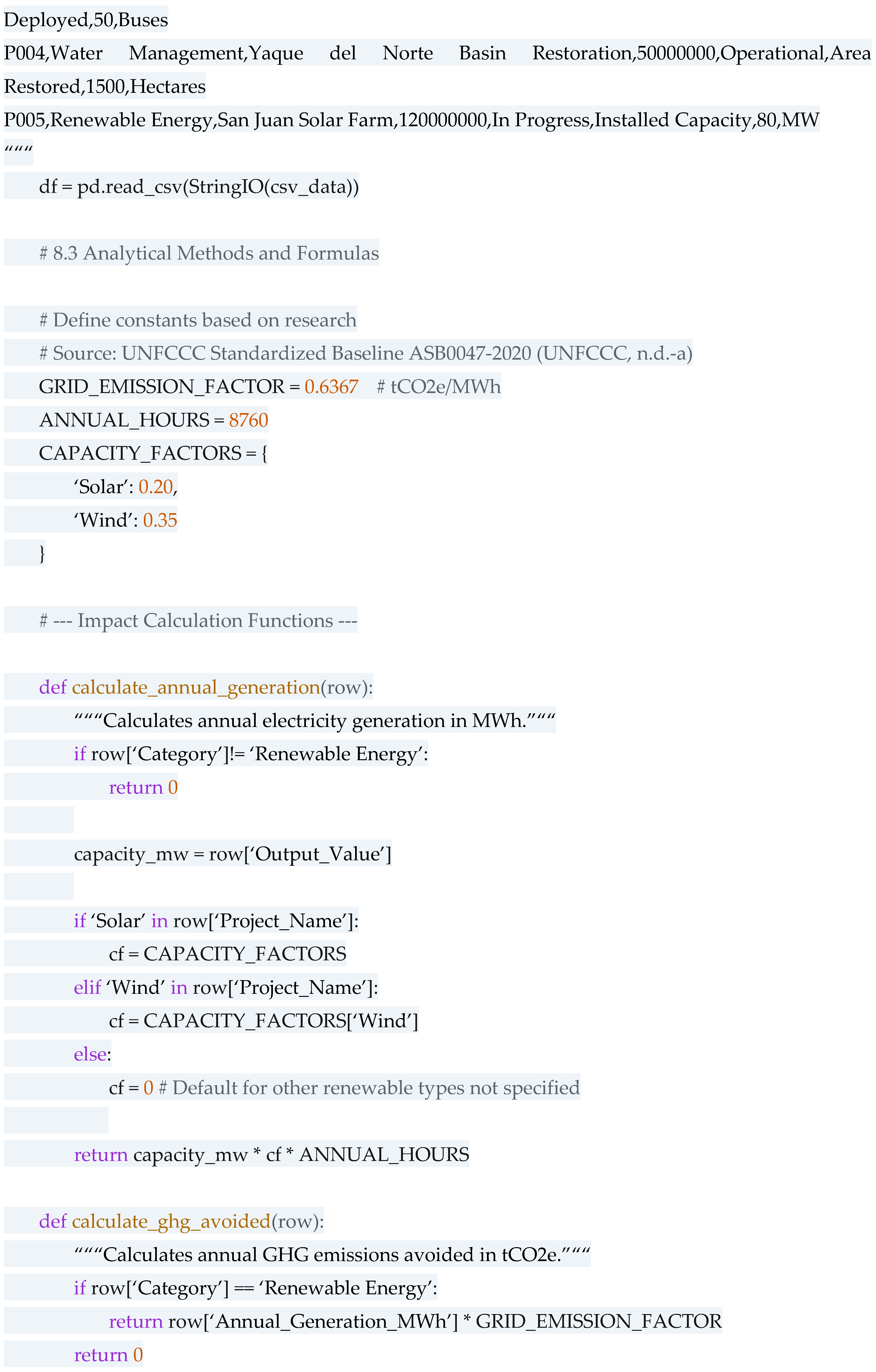

Appendix A.3. Analytical Methods and Formulas

The core analytical function of the Tracker is to convert project outputs into quantifiable environmental impacts. The primary formula for renewable energy projects is the calculation of avoided greenhouse gas emissions.

Formula 1: GHG Emissions Avoided

GHGavoided=Egen×EFgrid

Where:

GHG_avoided: Greenhouse gas emissions avoided, measured in tonnes of CO2 equivalent per year (tCO2e/year).

-

E_gen: Net annual electricity generation from the project, measured in megawatt-hours per year (MWh/year). This is calculated as:Egen=CapacityMW×CF×8760 hours/year

-

o

Capacity_MW: Installed capacity of the power plant in MW.

-

o

CF: The capacity factor of the technology (a dimensionless ratio representing the actual output over time compared to its potential output if it were possible for it to operate at full nameplate capacity continuously). For this model, we assume a CF of 20% for solar and 35% for wind.

EF_grid: The CO2 grid emission factor for the Dominican Republic’s national interconnected electricity system (SENI). Based on UNFCCC-approved standardized baselines and related studies, a conservative ex-ante value is 0.6367 tCO2e/MWh (UNFCCC, n.d.-a). This factor represents the carbon intensity of the electricity displaced by the new renewable energy project.

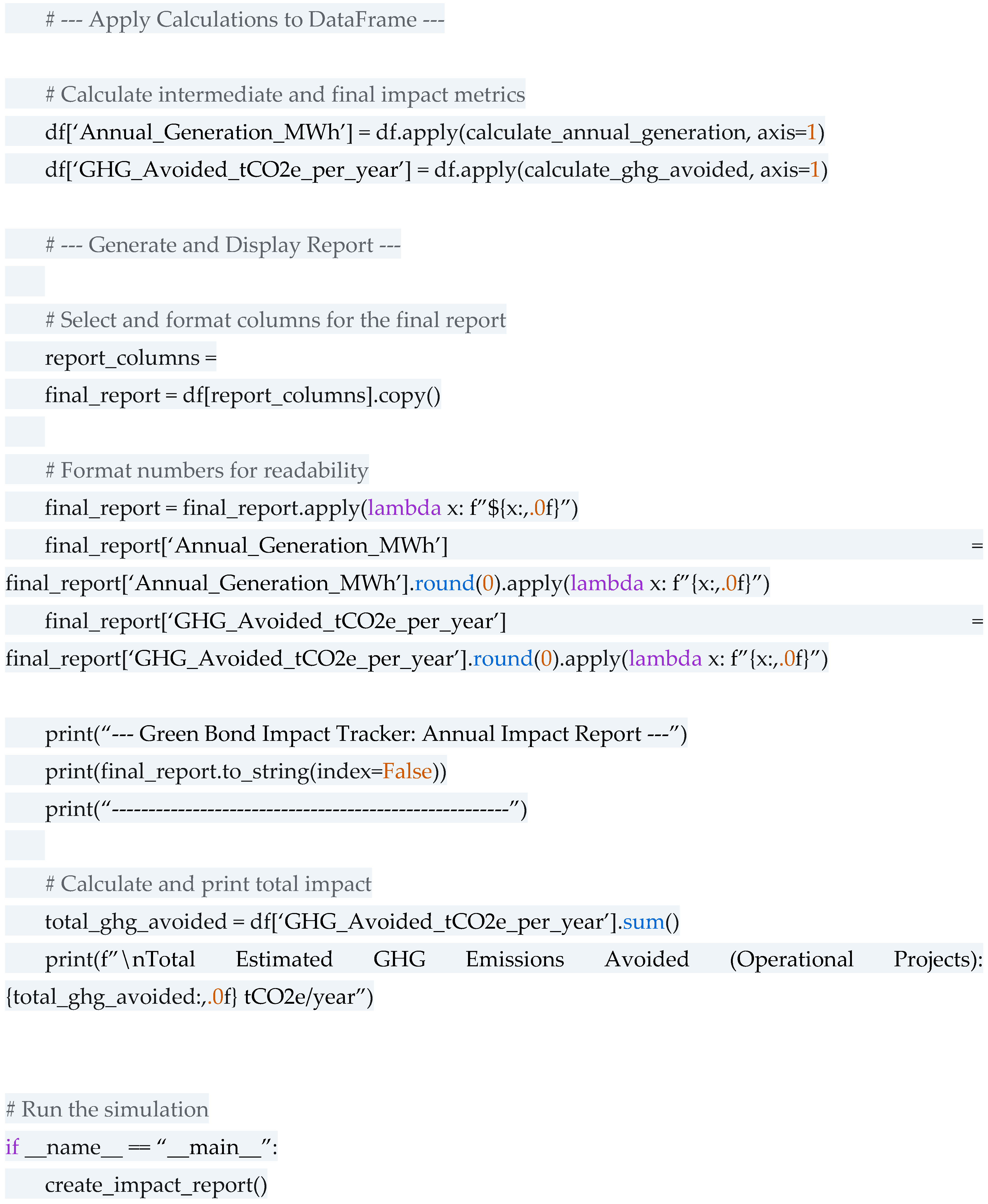

Appendix A.4. Sample Python Implementation

This Python code is a functional, self-contained script that can be executed to produce the sample impact report. It operationalizes the concepts discussed in the paper, providing a tangible example of the Tracker’s analytical capabilities.

References

- Amundi. (2025). Emerging market green bonds report 2024. Retrieved June 5, 2025, from https://www.amundi.com/institutional/article/emerging-market-green-bonds-report-2024.

- Baker McKenzie. (2019). Critical challenges facing the green bond market. Retrieved September 5, 2024, from https://www.bakermckenzie.com/-/media/files/insight/publications/2019/09/iflr--green-bonds-%28002%29.pdf.

- Climate Policy Initiative. (2024). Leveraging NDC updates to bridge the climate finance gap. Retrieved May 10, 2025, from https://www.climatepolicyinitiative.org/leveraging-ndc-updates-to-bridge-the-climate-finance-gap/.

- Dirección General de Crédito Público. (2024a). Inaugural Green Bond Pre-Issuance Indicative Allocation Report. Ministerio de Hacienda de la República Dominicana. Retrieved September 10, 2024, from https://www.creditopublico.gob.do/Content/emisiones_de_titulos/asg/otrosdocumentos/02Rep%C3%BAblica%20Dominicana%20-%20Reporte%20Adjudicaci%C3%B3n%20Indicativa%20Para%20Bono%20Verde%20Inagurar%20(Pre-emisi%C3%B3n).pdf.

- Dirección General de Crédito Público. (2024b). Prospectus Bonos Verdes con Vencimiento en 2036 y Reapertura de Bonos con Vencimiento 2031. Ministerio de Hacienda de la República Dominicana. Retrieved September 11, 2024, from https://www.creditopublico.gob.do/Content/emisiones_de_titulos/externas/prospectus/26Prospectus%20Bonos%20Verdes%20con%20Vencimiento%20en%202036%20y%20Reapertura%20de%20Bonos%20con%20Vencimiento%202031.pdf.

- Dominican Republic. (2020). Contribución Nacionalmente Determinada 2020. UNFCCC. Retrieved December 5, 2024, from https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/NDC/2022-06/Dominican%20Republic%20First%20NDC%20%28Updated%20Submission%29.pdf.

- Emerald. (2024). Greenwashing practices and ESG reporting: an international review. International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy. Retrieved May 15, 2025, from https://www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi/10.1108/sampj-03-2024-0212/full/html.

- European Central Bank. (2022). What’s in a green bond? The impact of credibility and investors’ demand on the greenium. (ECB Working Paper Series No 2728). Retrieved May 1, 2025, from https://www.ecb.europa.eu/pub/pdf/scpwps/ecb.wp2728~7baba8097e.en.pdf.

- Global Green Growth Institute. (2025). Dominican Republic’s Green Bond Debut (USD 750 Million) after Publication of Green, Social, Sustainable Bonds Framework. Retrieved May 29, 2025, from https://gggi.org/dominican-republics-green-bond-debut-usd-750-million-after-publication-of-green-social-sustainable-bonds-framework/.

- Hong Kong Monetary Authority. (2022). Greenwashing in the corporate green bond markets (Research Memorandum RM08-2022). Retrieved September 15, 2024, from https://www.hkma.gov.hk/media/eng/publication-and-research/research/research-memorandums/2022/RM08-2022.pdf.

- International Finance Corporation. (2018). Creating Green Bond Markets. Retrieved October 1, 2024, from https://www.ifc.org/content/dam/ifc/doc/mgrt/sbn-creating-green-bond-markets-report-case-studies.pdf.

- International Monetary Fund. (2022). Green Bonds: A Primer on Adverse Selection and Greenwashing. (IMF Working Paper WP/22/246). Retrieved November 10, 2024, from https://www.elibrary.imf.org/view/journals/001/2022/246/article-A001-en.xml.

- International Monetary Fund. (2023). How large is the sovereign greenium? (IMF Working Paper WP/23/80). Retrieved November 5, 2024, from https://www.elibrary.imf.org/view/journals/001/2023/080/article-A001-en.xml.

- International Monetary Fund. (2024). Sovereign green bonds: A catalyst for sustainable debt market development? (IMF Working Paper WP/24/120). Retrieved November 6, 2024, from https://www.elibrary.imf.org/view/journals/001/2024/120/article-A001-en.xml.

- IJNRD. (2024). Greenium in Emerging Markets: A Review of Determinants and Contextual Factors. International Journal of Novel Research and Development, 9(5). Retrieved June 1, 2025, from https://www.ijnrd.org/papers/IJNRD2409419.pdf.

- LatinFinance. (2024, June 25). Dominican Republic issues first green bond. Retrieved September 2, 2024, from https://latinfinance.com/daily-brief/2024/06/25/domrep-issues-its-first-green-bond/.

- Legal500. (2025). Sovereign green bonds: increasing focus and their significance for sustainable investment practices. Retrieved May 2, 2025, from https://www.legal500.com/developments/thought-leadership/sovereign-green-bonds-increasing-focus-and-their-significance-for-sustainable-investment-practices/.

- Mungroo, R. (2024). Addressing Leakage in Carbon Markets: A Technological Integration Framework for Digital MRV Systems. UNFCCC. Retrieved June 1, 2025, from https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/resource/MEP004_CfI_Addressing_Leakage_Mungroo.pdf.

- Sustainability Directory. (2025). Digital MRV Systems. Retrieved April 30, 2025, from https://climate.sustainability-directory.com/term/digital-mrv-systems/.

- UAGC Writing Center. (2025). Writing a case study analysis. Retrieved March 25, 2025, from https://writingcenter.uagc.edu/writing-case-study-analysis.

- UNDP. (2025, June 11). Climate transparency: The key to unlocking finance and development. Climate Promise. Retrieved June 20, 2025, from https://climatepromise.undp.org/news-and-stories/climate-transparency-key-unlocking-finance-and-development.

- UNFCCC. (n.d.-a). Determination of the Grid CO2 Emission Factor for the Electrical System of the Dominican Republic. Retrieved June 15, 2025, from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/275522435_Determination_of_the_Grid_CO2_Emission_Factor_for_the_Electrical_System_of_the_Dominican_Republic.

- UNFCCC. (n.d.-b). Enhanced Transparency Framework. Retrieved June 15, 2025, from https://unfccc.int/process-and-meetings/transparency-and-reporting/preparing-for-the-ETF.

- UNFCCC. (n.d.-c). The Enhanced Transparency Framework in Practice. Retrieved June 15, 2025, from https://www.c2es.org/document/the-enhanced-transparency-framework-in-practice/.

- World Bank. (2023). India: Sovereign Green Bond Technical Assistance. Retrieved October 5, 2024, from https://thedocs.worldbank.org/en/doc/c68d5c90796897b1628c25fea3590a5b-0340012023/original/Case-Study-India-Green-Bond-TA.pdf.

- World Bank. (2025, July 1). Investing in a greener future: Successful debut of the Green Bond of the Dominican Republic. World Bank Blogs. Retrieved June 5, 2025, from https://blogs.worldbank.org/en/latinamerica/invertir-futuro-debut-bono-verde-republica-dominicana.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).