1. Introduction

Cassava, also known as the South Sea potato, is a perennial shrub of the Euphorbiaceae family, mainly distributed in tropical and subtropical regions. As an important tropical crop with food, economic, and horticultural value, cassava not only provides starch-rich storage roots that are widely used as food and industrial raw materials, but also produces tender leaves that are consumed as leafy vegetables in parts of Africa and Asia [

1,

2]. These leaves are rich in proteins, vitamins, and minerals, offering high nutritional value and great potential for horticultural development [

3,

4]. Due to its strong tolerance to drought, poor soils, and environmental stresses, cassava is considered a key crop for ensuring food and nutritional security in marginal areas, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa [

5].

CBB (Cassava bacterial blight) is one of the major international quarantine diseases caused by

Xanthomonas pxonopodis pv.

manihotis (

Xpm) [

6]. It leads to severe destruction of the global cassava production [

7] and has even been linked to famines throughout human history [

8]. The initial signs of infection manifest as dark green, angular lesions on the leaves that appear water-soaked. Subsequently, the pathogen

Xpm spreads through the vascular system, causing the leaves to wilt and eventually leading to the death of plants [

9]. However, currently, there are no effective strategies for preventing or controlling CBB.In present years, enhancing genetic resistance to CBB has emerged as a critical research priority in cassava breeding research. When specific cell-surface receptors detect pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs), PAMP-triggered immunity (PTI) is initiated. This activates signaling pathways, orchestrating a cascade of disease-resistance responses and inducing the transcriptional activation of numerous defense-related genes in plant cells [

10,

11].

Transcription factors play a vital role in plant responses to environmental stress. They regulate plant growth, development, and stress signaling pathways by binding to cis-elements in the promoter regions of various genes [

12]. This establishes complex regulatory networks that modulate physiological and metabolic responses, enabling plants to adapt to specific environmental conditions and stressors or enhance disease resistance [

13].

Growth regulatory factors (GRFs) represent a large gene family characterized by highly conserved proteins. The N-terminal regions of GRF proteins contain two well-conserved domains: QLQ (Glu-Leu-Glu) and WRC (Trp-Arg-Cys) [

14]. The QLQ domain, composed of the conserved Gln-Leu-Gln (QX₃LX₂Q) motif and its adjacent residues, is also found in the SWI2/SNF2 chromatin-remodeling protein complex in

Saccharomyces cerevisiae [

15,

16,

17]. The GIF proteins possess a highly conserved SNH domain at the N-terminus that directly interacts with the GRF QLQ domain [

18]. The WRC domain, which consists of three cysteines and one histidine residue (CX₉CX₁₀CX₂H, also known as the C

3H motif), serves as a DNA-binding domain that regulates downstream gene expression by binding to cis-acting elements [

19,

20]. In contrast to the conserved N-terminal region, the C-terminal region of the GRF proteins is less conserved and contains additional motifs such as TQL (Thr, Gln, Leu), FFD (Phe, Phe, Asp), and GGPL (Gly, Gly, Pro, Leu) [

14,

15,

21,

22].

GRFs are unique plant-specific transcription factors that regulate plant growth, development, and responses to biotic stresses [

23,

24,

25]. The first GRF gene, named OsGRF1, was identified in rice (

Oryza sativa) and was found to be induced by gibberellin (GA₃) [

15], where it played a key role in stem elongation. The GRF gene family comprises 9 members in

Arabidopsis thaliana, 12 in rice(

Oryza sativa), 14 in maize(

Zea mays), and 17 in Chinese cabbage (

Brassica rapa) [

14,

21,

26,

27,

28]. Extensive research has demonstrated that GRF genes are involved in various aspects of plant development, including leaf growth [

29], flower organ development [

30,

31], grain size [

32], root development [

33], and the regulation of plant organ lifespan [

34]. Most GRF genes exhibit higher expression levels in meristematic and young tissues, while their expression is typically reduced in mature tissues [

21]. In

A. thaliana, triple null mutants of grf1/2/3 produce smaller leaves and cotyledons, while single mutants showed no noticeable changes in phenotype, double mutants exhibited only slight alterations [

21]. The overexpression of AtGRF1 and AtGRF2 results in larger leaves, longer petioles, and a delay in bolting the inflorescence stem relative to wild-type plants [

21]. In rice, the overexpression of OsGRF3 and OsGRF10 induces the formation of adventitious roots at nodesand give rises to abnormal meristematic activity [

35,

36,

37]. In addition, GRF genes contribute to stress responses by coordinating plant growth with defense mechanisms. For example, the overexpression of AtGRF7 in

Arabidopsis enhances resistance to drought and salt stress [

23]. Certain GRFs are involved in responding to environmental stress. For instance, OsGRF6 is crucial for responding to biotic and abiotic stresses, contributing to the balance between growth and disease resistance in rice [

37,

38,

39,

40]. Likewise, AtGRF1 and AtGRF3 have been implicated in the biotic stress response following

Heterodera schachtii infection [

33]. Nonetheless, the roles of GRF family genes in responding to environmental stress in various plant species, including cassava, are still mostly uninvestigated [

22].

GIF proteins represent a conserved class of plant transcriptional coactivators, functionally analogous to human SYT coactivators [

41] and classified within the SSXT superfamily [

25]. Structurally, these proteins feature an N-terminal SNH domain highly conserved and capable of direct interaction with the QLQ domain of GRF proteins [

42], and a C-terminal transactivation domain rich in glutamine (Q) and glycine (G), termed the QG domain due to its distinctive composition [

27]. In

A. thaliana, the GIF family comprises three members: GIF1, GIF2, and GIF3 [

23,

43]. While AtGIF1 regulates leaf growth and morphology [

33,

44], GIF2 and GIF3 primarily enhance cell proliferation, influencing leaf size [

43]. Emerging evidence indicates that GIF proteins may interact with additional regulatory factors to coordinate plant growth and development [

34,

45,

46,

47]. Ultimately, it is important to note that although GIFs have the ability to activate transcription, their absence of a DNA-binding domain indicates that they act as transcriptional co-regulators instead of being direct transcription factors [

46,

47].

The GRF family encodes transcription factors that bind to DNA in a sequence-specific manner and interact with the transcriptional coactivator GIF to form a functional transcriptional complex [

42]. This complex plays crucial roles in plant growth and development, including leaf, stem, root, seed, and flower development [

19]. The functions of GRF-GIF fusion proteins have been extensively studied. For example, a GRF-GIF chimeric protein in wheat enhances plant regeneration, improves transformation efficiency [

48], and facilitates gene editing applications. In

A. thaliana, a GRF-GIF fusion protein increases chlorophyll content and delays leaf senescence [

49]. Additionally, these fusion proteins influence biotic stress responses. For instance, in cabbage (

Brassica oleracea), the expression of a GRF5-GIF1-GRF5 fusion protein optimizes genetic transformation efficiency [

50]. By using an optimized gene editing and transformation system, researchers successfully knocked out the BoBPM6 and BoDMR6 genes, generating novel cabbage germplasm with broad-spectrum disease resistance [

50]. These findings highlight the pivotal role of GRF-GIF interactions in plant development and their potential in agricultural biotechnology for crop improvement.

To better understand the functional evolution of GRF and GIF genes in cassava and their roles in shaping horticultural traits and to investigate their possible regulatory functions in response to Xpm, we performed a genome-wide identification and expression analysis of the GRF and GIF gene families. A total of 28 MeGRFs and 5 MeGIFs were identified in the cassava genome. Comprehensive in silico analyses were conducted to characterize their chromosomal distribution, cis-regulatory elements, evolutionary relationships, genome collinearity, and patterns of selection pressure. In addition, we investigated their potential functional roles through protein-protein interaction network predictions and gene expression profiling. These results will offer important understanding of the regulatory roles of GRF and GIF family members in relation to cassava bacterial blight (CBB) infection.

3. Results

3.1. Identification Analysis of the MeGRFs and MeGIFs Gene in the Cassava Genome

Through BLAST and HMMER searches of the WRC (PF08879) and QLQ (PF08880) domains, 28 non-redundant candidate MeGRF genes were identified from the cassava genome database. We further named these genes MeGRF1-28 based on their position on the chromosome. ranging from 191 aa (MeGRF5) to 2243 aa (MeGRF3 and MeGRF10) amino acids in length. The molecular weights ranged from 20990.78 Da (MeGRF5) to 251011.23 Da (MeGRF10), and the isoelectric points were between 5.65 (MeGRF6) and 9.67 (MeGRF17). The pI values of 21 PgGRF members were greater than 7. The instability index ranged from 39.8 (MeGRF4) to 61.43 (MeGRF17), the Aliphatic Index was between 45.29 (MeGRF19) and 75.22 (MeGRF12), and the Grand Average of Hydropathicitywas from -1.018 (MeGRF17) to -0.471 (MeGRF11) (

Table S1).

Furthermore, we obtained five MeGIF genes through BLAST and HMMER searches of the conserved domain SSXT (PF05030). These genes were named MeGIF1-5 based on their position on the chromosome. The amino acid lengths of the GIF proteins in cassava ranged from 144 aa (MeGIF1) to 224 aa (MeGIF5). In addition, the interval of molecular weights was 16790.96 Da (MeGIF1) to 23706.29 Da (MeGIF5), and the isoelectric points varied from 5.63 (MeGIF2) to 6.12 (MeGIF1). These outcomes indicated that these GIF proteins were rich in acidic amino acids. Also, the instability index ranged from 58.59 (MeGIF3) to 77.37 (MeGIF1), the Aliphatic Index flctuated between 54.11 (MeGIF4) and 68.54 (MeGIF1), and the Grand Average of Hydropathicity spanned from -0.88 (MeGIF1) to -0.582 (MeGIF4) (

Table S1).

Table 1.

Physical and chemical properties of the MeGRFs and MeGIFs gene family proteins.

Table 1.

Physical and chemical properties of the MeGRFs and MeGIFs gene family proteins.

Gene ID

|

Number of Amino Acid |

Molecular Weight |

Theoretical pI |

Instability Index |

Aliphatic Index |

Grand Average of Hydropathicity |

| MeGRF1 |

495 |

52400.94 |

6.32 |

55.07 |

61.58 |

-0.507 |

| MeGRF2 |

218 |

23968.14 |

8.99 |

53.19 |

72.02 |

-0.544 |

| MeGRF3 |

2243 |

250934.06 |

9.08 |

55.41 |

72.58 |

-0.706 |

| MeGRF4 |

480 |

51734.08 |

9.29 |

39.8 |

65.25 |

-0.604 |

| MeGRF5 |

191 |

20990.78 |

9.21 |

61.39 |

69.95 |

-0.609 |

| MeGRF6 |

257 |

29154.26 |

5.65 |

47.84 |

65.64 |

-0.962 |

| MeGRF7 |

496 |

54818.67 |

9.17 |

48.77 |

61.33 |

-0.695 |

| MeGRF8 |

359 |

40723.21 |

8.69 |

56.36 |

55.99 |

-0.85 |

| MeGRF9 |

345 |

38959.98 |

8.22 |

58.33 |

52.61 |

-0.866 |

| MeGRF10 |

2243 |

251011.23 |

8.93 |

58.16 |

70.4 |

-0.746 |

| MeGRF11 |

475 |

51559.57 |

9.54 |

47.05 |

73.87 |

-0.471 |

| MeGRF12 |

276 |

31666.05 |

6.51 |

53.13 |

75.22 |

-0.522 |

| MeGRF13 |

595 |

64651.39 |

6.63 |

56.15 |

66.87 |

-0.588 |

| MeGRF14 |

339 |

37222.87 |

8.32 |

45 |

66.25 |

-0.502 |

| MeGRF15 |

409 |

44355.41 |

8.61 |

53.14 |

62.32 |

-0.581 |

| MeGRF16 |

323 |

35901.59 |

9.57 |

56.67 |

60.93 |

-0.909 |

| MeGRF17 |

335 |

37622.51 |

9.67 |

61.43 |

53.28 |

-1.018 |

| MeGRF18 |

944 |

107236.37 |

6.11 |

42.81 |

75.67 |

-0.647 |

| MeGRF19 |

327 |

36385.27 |

8.74 |

57.02 |

45.29 |

-0.784 |

| MeGRF20 |

340 |

38313.39 |

9.32 |

54.09 |

59.06 |

-0.695 |

| MeGRF21 |

396 |

43061.93 |

7.81 |

47.56 |

62.37 |

-0.624 |

| MeGRF22 |

344 |

38540.8 |

9.01 |

57.02 |

49.39 |

-0.798 |

| MeGRF23 |

448 |

49554.39 |

5.97 |

59.41 |

61.61 |

-0.552 |

| MeGRF24 |

1520 |

172018.07 |

5.94 |

46.36 |

75.61 |

-0.488 |

| MeGRF25 |

1036 |

117794.42 |

8.56 |

53.77 |

75.81 |

-0.543 |

| MeGRF26 |

384 |

43073.87 |

8.84 |

53.73 |

56.88 |

-0.783 |

| MeGRF27 |

1043 |

118549.18 |

8.3 |

51.52 |

78.68 |

-0.519 |

| MeGRF28 |

627 |

68086.34 |

8.68 |

51.04 |

61.18 |

-0.635 |

| MeGIF1 |

144 |

16790.96 |

6.12 |

77.37 |

68.54 |

-0.88 |

| MeGIF2 |

208 |

22243.16 |

5.63 |

69.46 |

60.24 |

-0.606 |

| MeGIF3 |

207 |

21958.62 |

5.83 |

58.59 |

54.98 |

-0.676 |

| MeGIF4 |

219 |

23066.56 |

5.72 |

64.57 |

54.11 |

-0.582 |

| MeGIF5 |

224 |

23706.29 |

5.8 |

62.54 |

56.34 |

-0.617 |

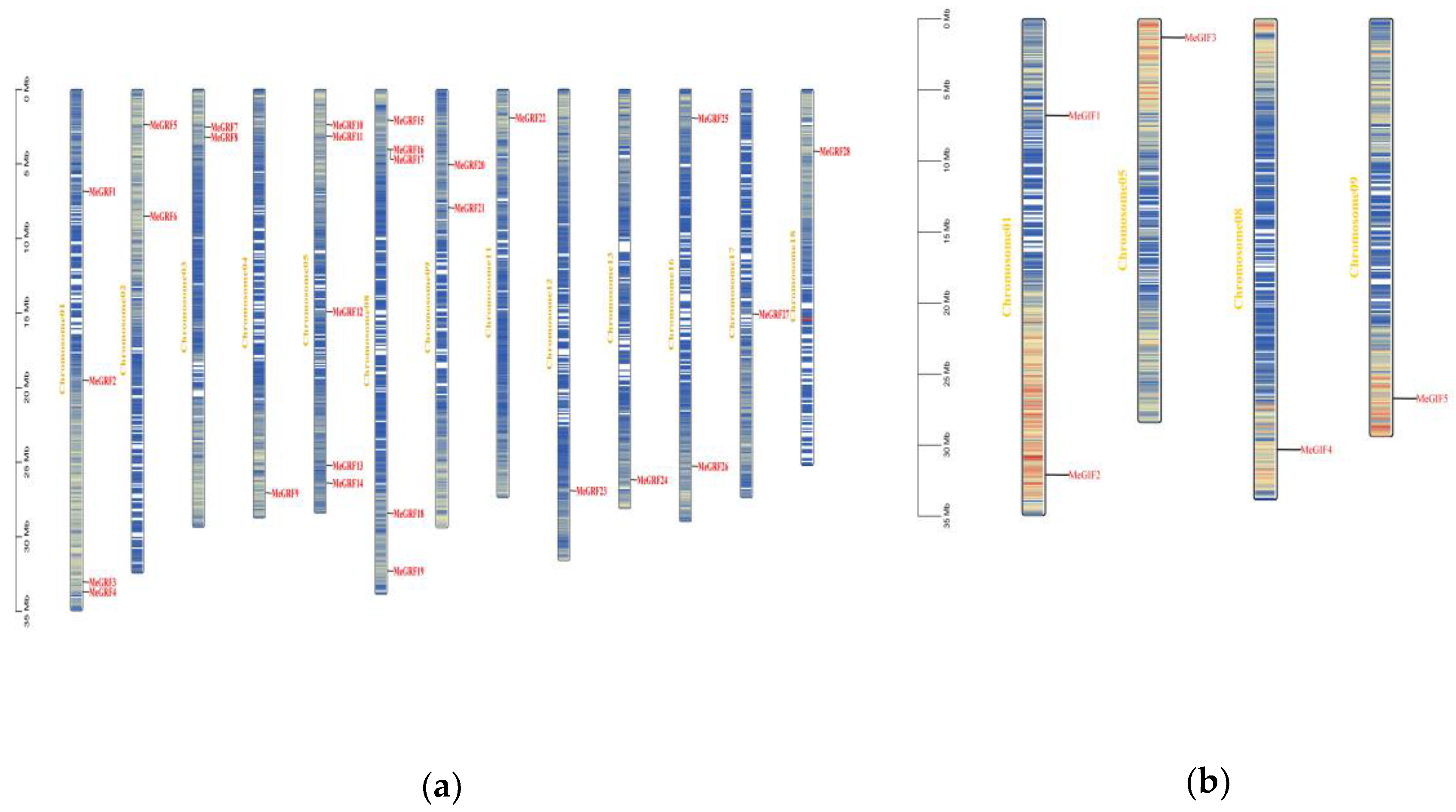

MeGRFs and MeGIFs were unevenly distributed on cassava chromosomes. MeGRF genes were distributed across 13 chromosomes (chromosomes1-5,chromosomes8-9, chromosomes11-13, chromosomes16-18). Some chromosomes harbored multiple MeGRF genes. For example, Chromosome08 had five genes ( MeGRF15-19), while some chromosomes had only one MeGRF gene (chromosomes4, chromosomes11-13, chromosomes17-18). In contrast, MeGIF genes were distributed across 4 chromosomes (chromosomes1, chromosomes5, chromosomes8-9). All chromosomes had only one gene except for two genes on the first chromosome (

Figure 1).

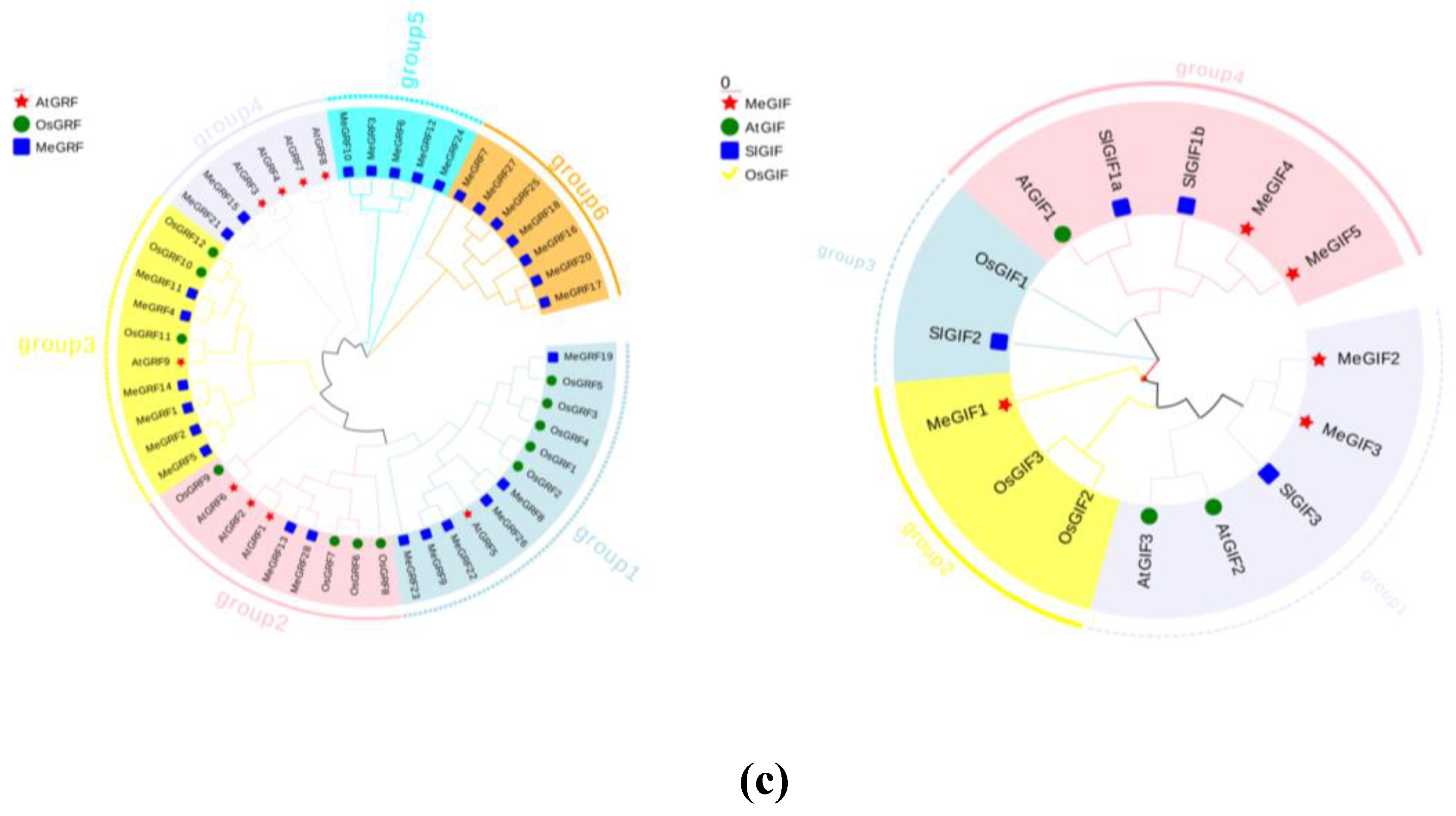

3.2. Phylogenetic, Conserved Motif, and Gene Structure Analysis

To explore the evolutionary relationships and sequence homology between MeGRF proteins,

A. thaliana, and rice, a phylogenetic tree was constructed using MEGA11 software. The evolutionary relationship of MeGRFs was analyzed, and 49 MeGRFs from 3 plant species (AtGRF,OsGRF,MeGRF) were clustered into 6 subgroups, designated as Group 1, Group 2, Group 3, Group 4, Group 5, and Group 6 (

Figure 2c). 6, 2, 6, 2, 5, and 7 MeGRF members were assigned to subgroups 1, 2, 3, 4, 5and 6, respectively (

Figure 2). Notably, MeGRFs were found to be more closely related to AtGRFs, probably due to the fact that both cassava and

Arabidopsis are dicotyledonous species. The clear separation of subgroups in the tree highlighted the conserved nature and evolutionary divergence of the MeGRFs gene family across different species. For instance, Group 4 includes MeGRF proteins from cassava(MeGRF15,MeGRF21) and

Arabidopsis(AtGRF3-4,AtGRF7-8), illtustrating the potential conservation of roles in growth and development. In contrast, Group 6 contained only MeGRFs, which implied the cassava-specific functional evolution. Furthermore, within Group 2, OsGRF6 was previously reported to enhance rice yield and resistance to bacterial blight, suggesting that members of this subgroup may also play key roles in biotic stress responses (

Figure 2).

The phylogenetic relationship of MeGIFs clustered 15 MeGIFs from 4 plant species(MeGRF,AtGRF,SlGRF,OsGRF) into 4 subgroups, subsequently designated as Group 1, Group 2, Group 3, and Group 4. 5, 3, 2, and 5 MeGIF members are assigned to subgroups 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5, respectively (

Figure 2d). The phylogenetic tree showed that MeGIF was more closely related to AtGIF and SlGIF than OsGIF (

Figure 2d). This could be due to the fact that cassava and tomato are both dicotyledons. Group 4 consisted of various MeGIF members along with SiGIF1a and SiGIF1b, creating a closely-knit evolutionary group. This indicated that these genes might be involved in comparable regulatory pathways or possess conserved functional traits. In contrast, Group 3 contained only MeGIF1 and OsGIF1, indicating that this subgroup may represent a more conserved and functionally distinct lineage.

To determine the structural diversity and functional prediction of MeGRFs and MeGIFs, the amino acid sequences of MeGRFs and MeGIFs family members were compared several times. A total of 10 conserved motifs were identified in MeGRF. Among them, motifs 1 and 2 are labeled as WRC and QLQ domains, respectively, and they are included in most of the MeGRF family members, indicating that these two domains are highly conserved. It is important to note that the characteristics of these motifs are consistent within the same cluster. For example, MeGRF22, MeGRF9, MeGRF8, and MeGRF26 exhibit 4 common conserved motifs (motifs 1, 2, 3, and 5). The gene structure of the MeGRF gene family was further analyzed using the GSDS online tool. The lengths of MeGRF genes range from approximately 2,000 to 12,000 bp.Members of the same phylogenetic cluster exhibited similar exon-intron structures, suggesting a strong correlation between gene structure and evolutionary relationships within the gene family. In addition, MeGRF8, MeGRF19, and MeGRF15 had only one 3’ untranslated region (UTR), while MeGRF22, MeGRF9, MeGRF23, MeGRF14, MeGRF20, and MeGRF7 did not have a 3’ UTR, and the other 19 MeGRF genes have 5’ CDS and 3’ UTR at both ends (

Figure 2d). A total of 10 conserved motifs were identified in MeGIFs. Among them, motif 1 is labeled as the SSXT domain, and they are found in all MeGIF gene members, indicating that this domain is highly conserved. It is important to note that the characteristics of these motifs are consistent within the same cluster. For example, MeGIF2 and MeGIF3 exhibit 7 common conserved motifs (motifs 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 8, and 9). The gene structure of the MeGIF gene family was further analyzed using the GSDS online tool. The lengths of MeGIF genes range from approximately 1,000 to 5,000 bp, with each gene containing two to three introns. Members of the same phylogenetic group showed comparable exon-intron arrangements, indicating a significant link between gene structure and the evolutionary connections among members of the gene family. In addition, MeGIF2 did not have a 3′ UTR at either end, while the other 4 MeGIF genes have 5′-CDS and 3′-UTR at both ends (

Figure 3 and

Figure 4).

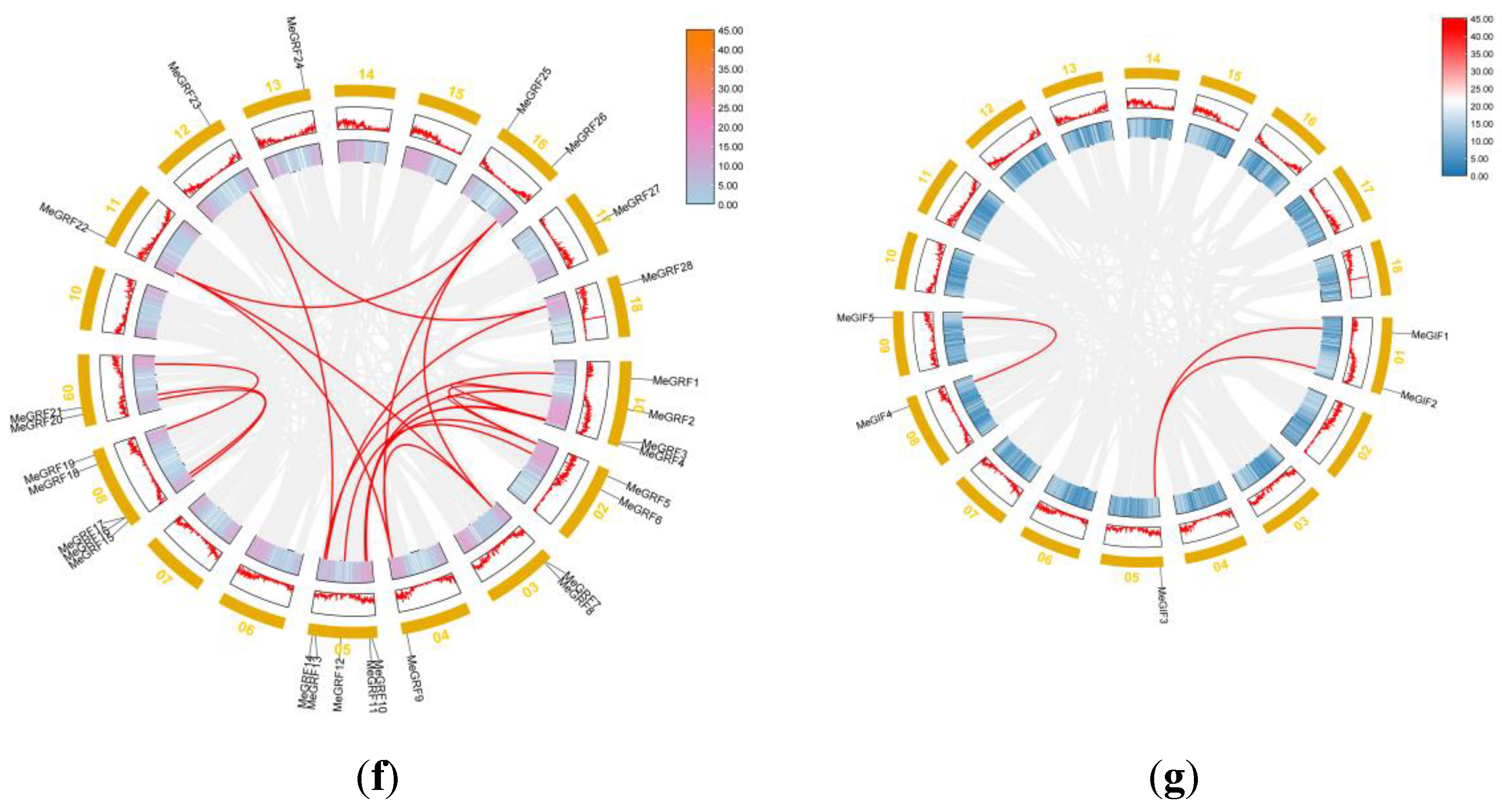

3.3. Synteny Analysis of MeGRFs and MeGIFs Genes

Gene duplication events were regarded as the primary driving force of evolution.. Previous studies defined two or more adjacent homologous genes on a single chromosome as tandem duplicated genes [

51]. In contrast, homologous genes between different genomic regions or chromosomes were considered segmental duplication genes [

51]. An intraspecific collinearity analysis showed that 20 pairs of MeGRFs originated from segmental replication (whole-genome duplication, WGD). In the MeGIF family, 3 pairs of MeGIFs originated from segmental replication. Based on the above results, we can infer that WGD events lead to the derivation of new MeGRF gene members. The same phenomenon was found in many other plant GRF and GIF families, such as

Panax ginseng (

Figure 4) [

52].

Figure 4.

Collinearity analysis of GRFs and GIFs. The red lines indicate probably duplicated MeGRFs and MeGIFs gene pairs. (g) Collinearity analysis of all MeGRFs in the cassava genome. (h) Collinearity analysis of all MeGIFs in the cassava genome.

Figure 4.

Collinearity analysis of GRFs and GIFs. The red lines indicate probably duplicated MeGRFs and MeGIFs gene pairs. (g) Collinearity analysis of all MeGRFs in the cassava genome. (h) Collinearity analysis of all MeGIFs in the cassava genome.

3.4. Cis-Acting Elements in the Promoter Regions of MeGRFs and MeGIFs Genes

To further understand the function of cis-acting elements within the promoter region of MeGRF, the promoter region of MeGRFs was submitted to PlantCARE for prediction. These cis-regulatory elements are divided into four categories: light-responsive elements, hormone-responsive elements, growth and development-related elements, and stress-related elements. Light response includes seven cis-regulatory elements, accounting for the majority of the total number. MeGRF11, MeGRF19, and MeGRF28 were found to contain several cis-acting elements that were closely associated with hormonal responses, including ABRE (associated with abscisic acid reactivity), AuxRR-core (associated with auxin reactivity), TCA-element (associated with salicylic acid reactivity), CGTCA, and TGACGmotif (associated with MeJA reactivity), and P-box (associated with gibberellin reactive element). Most of the MeGRF genes containing the CGTCA and TGACG motifs were observed 48 times, accounting for 32 % of the hormone-associated cis-acting elements. The subsequent category pertains to plant growth and development, and it comprises 6 distinct types of cis-regulatory elements: CAT-box, CCAAT-box, GCN4 motif, Box II-like sequence, A-box, and O

2-site. The promoter regions of the 28 MeGRFs contain

cis-acting elements associated with environmental stresses. The ARE motif, critical for anaerobic induction, has been identified 53 times, accounting for 53 % of the stress-related cis-acting elements. TC-rich repeats, and defense and stress-responsive elements were identified from MeGRF10, MeGRF15, and MeGRF25 (

Figure 5).

The

cis-acting element in the promoter of MeGIFs is mainly responsible for the growth and development of plants, TCA element, CGTCA- and TGACG-motif, TATC-box (the MeJA-responsiveness), TGA-element (auxin-responsive element), ABRE, P-box and GARE-motif (gibberellins responsive element). The promoter region of the four MeGIFs contains cis-acting elements associated with environmental stress. LTR (Low-Temperature Responsive

cis-acting Element), MBS (drought-induced cis-acting element), MBSI (salt stress-induced cis-acting element), and the ARE motif have been discovered 12 times, accounting for 50 % of the stress-related cis-acting elements. The promoter of MeGIF5 contains CAT-box (associated with meristem development). Similarly, the promoter of MeGIF2 contains an MSA-like motif that is implicated in cell cycle regulation. In addition, cis-acting elements associated with light-responsive elements (G-box and Box 4) were also found in the promoters of MeGIFs (

Figure 5).

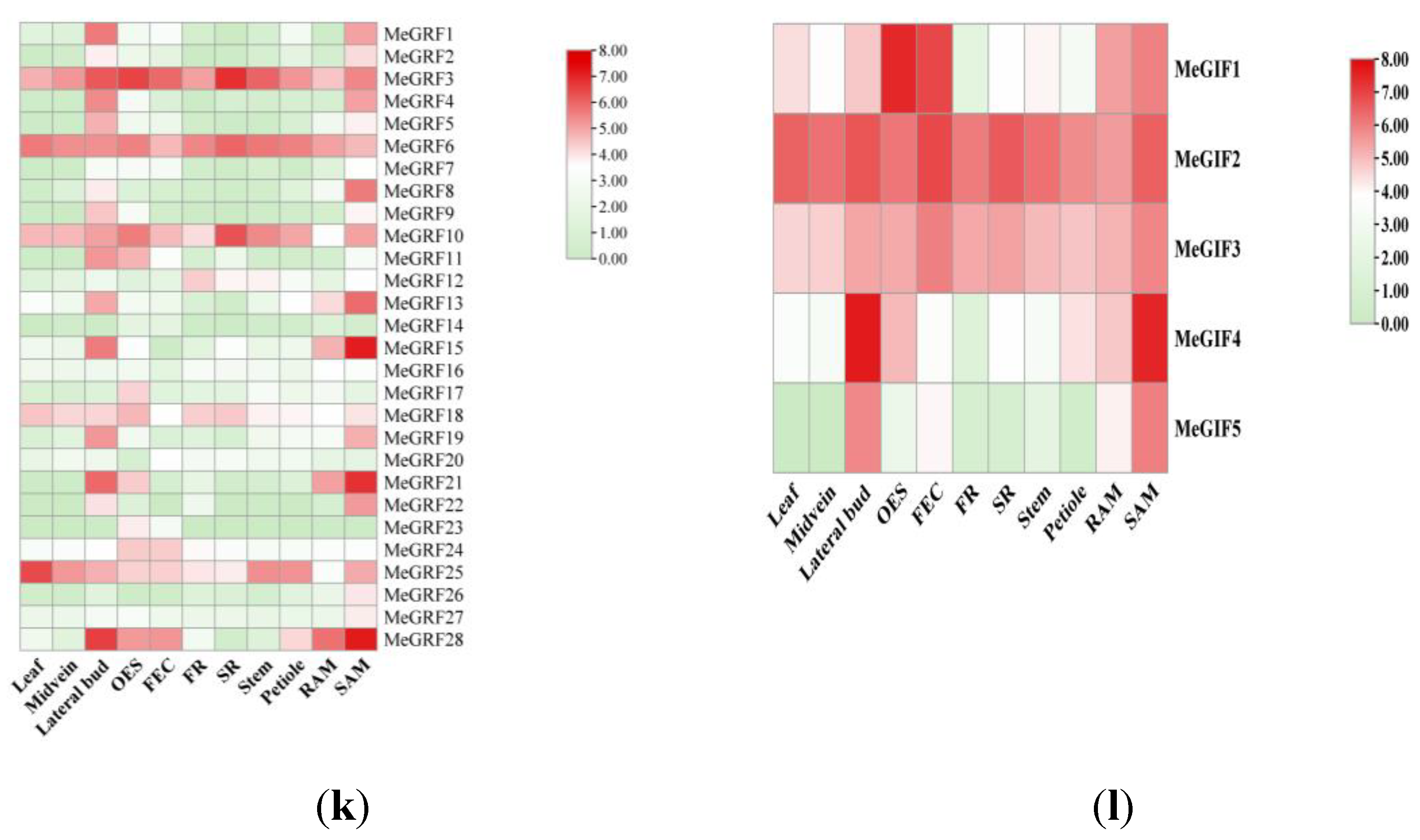

3.5. Tissue-Specific Expression of MeGRFs and MeGIFs in Cassava

The tissue-specific expression analysis of 28 genes showed that these genes exhibited significant expression differences across various cassava tissues. Overall, Six genes (MeGRF3, MeGRF6, MeGRF10, MeGRF18, MeGRF25, and MeGRF28) showed higher expression in the Lateral bud, and SAM was highly expressed in all 11 tested tissues (FPKM > 5). In comparison, two genes (MeGRF14 and MeGRF23) exhibited consistently low expression across all tissues (FPKM < 1)(

Figure 6).

The examination of tissue-specific expression for the five MeGIF genes revealed that all MeGIFs, with the exception of MeGIF5, showed high expression levels in leaves (FPKM > 10).. Notably, MeGIF2 and MeGRF3 were highly expressed across all 11 tissues. The distinct expression patterns of MeGRFs and MeGIFs suggest that these genes may participate in different biological processes in various cassava tissues(

Figure 6).

3.6. Expression Analysis of MeGRFs and MeGIFs Under Different Biotic and Abiotic Stresses

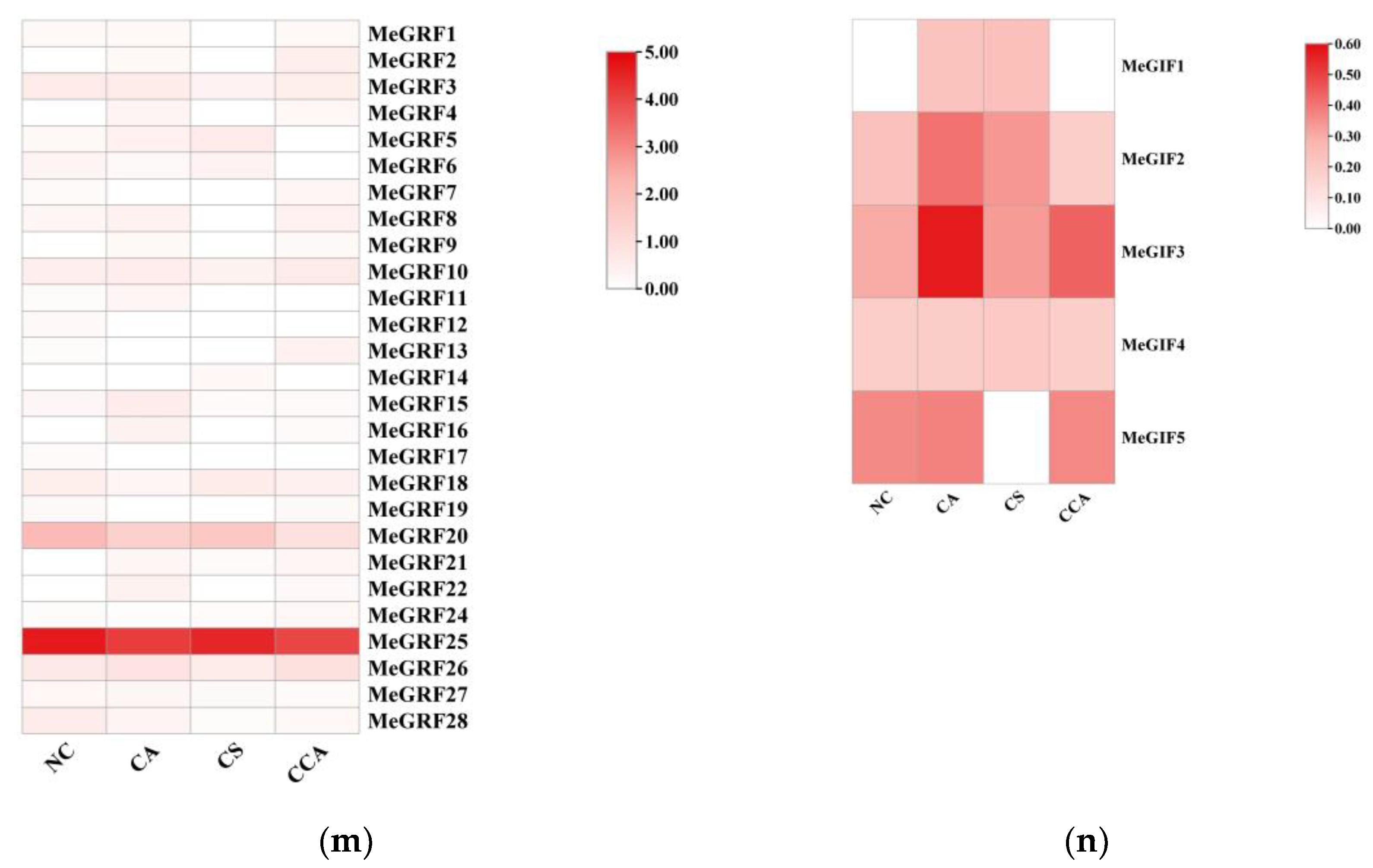

For MeGRFs, the expression levels varied significantly among different stress treatments. Under CA (from 24°C to 14°C), MeGRF1 showed a notable upregulation, while MeGRF2 was downregulated. This indicated that the responses of different MeGRF genes to moderate chilling stress were distinctive. When subjected to CCA (from 14°C to 4°C after acclimation), approximately two - thirds of the differentially expressed MeGRF genes reversed their expression patterns. For instance, MeGRF1, which was upregulated during CA, became downregulated during CCA. This reversal suggested that the plant's regulatory mechanisms adjust to the changing stress intensity, and MeGRFs play crucial roles in this adaptation process. Under CS (a rapid drop from 24°C to 4°C), a large number of MeGRF genes were expressed in different extents. MeGRF4, for example, was highly induced, suggesting its importance in the plant's response to sudden and severe chilling stress.

Regarding MeGIFs, similar trends were observed. During CA, MeGIF1 and MeGIF3 were upregulated, indicating their possible involvement in the early response to moderate chilling. In CCA, many differentially expressed MeGIFs reversed their expression directions. Specifically, 87.5% of the miRNAs that were down - and up - regulated from NC to CA reversed their expression from CA to CCA. This reversal was also observed in the expression of their target genes, suggesting a complex regulatory network involving MeGIFs and their targets in response to chilling stress. In the context of CS, the expression levels of MeGIFs were notably affected, particularly MeGIF4, which exhibited a significant drop in expression. This decline may be linked to the plant's reaction to the abrupt stress..

Figure 6.

Expression profiles of cassava GRF and GIF under different low temperature stress conditions. (m) Expression profiles of cassava GRF under different low temperature stress conditions. (n) Expression profiles of cassava GIF under different low temperature stress conditions. gradual chilling acclimation (CA), chilling stress after chilling acclimation (CCA), and chilling shock (CS), with plants grown at 24°C as the normal control (NC).

Figure 6.

Expression profiles of cassava GRF and GIF under different low temperature stress conditions. (m) Expression profiles of cassava GRF under different low temperature stress conditions. (n) Expression profiles of cassava GIF under different low temperature stress conditions. gradual chilling acclimation (CA), chilling stress after chilling acclimation (CCA), and chilling shock (CS), with plants grown at 24°C as the normal control (NC).

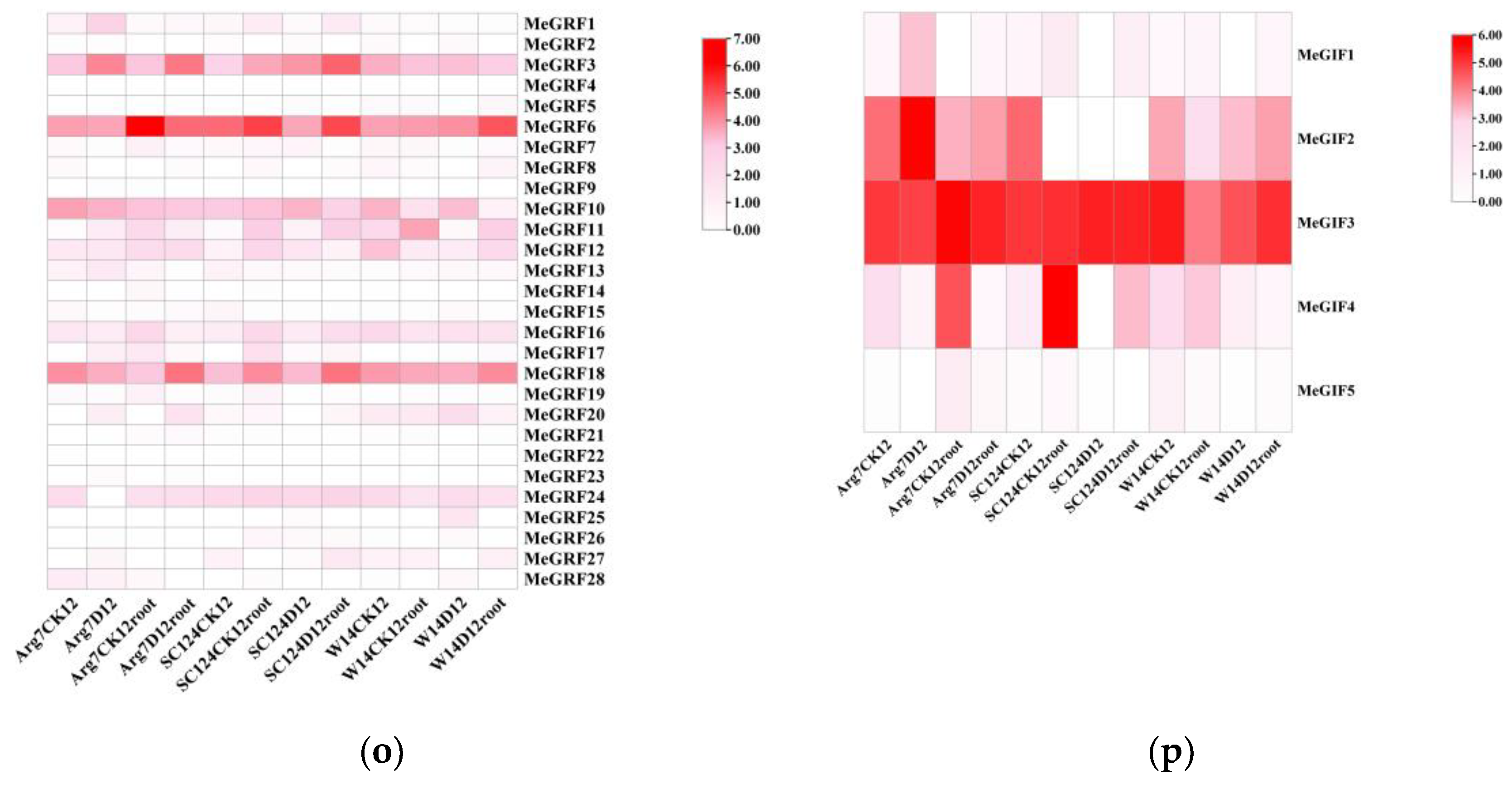

To seek insights into the roles of GRF and GIF genes in cassava development, total RNA was isolated from stems, leaves, and storage roots of cultivated varieties (Arg7) 、in south 124 (SC124) variety and china wild subspecies (W14) for transcriptome analysis.Regarding the MeGRFs heatmap, MeGRF5 standed out with high expression in various samples, including Arg7D12, SC124D12root, and W14D12root. This high expression might be associated with functions such as modulating cell growth and metabolism to cope with water scarcity. MeGRF17 also showed significant expression levels in multiple samples, potentially playing a role in stress - responsive pathways.On the other hand, some MeGRF genes like MeGRF14 and MeGRF20 had relatively low expression across most samples, suggesting that their functions may be less relevant or that they were downregulated under drought stress.

From the heatmap of MeGIFs, several notable patterns emerged. MeGIF2 showsed relatively high expression levels across multiple samples, such as in Arg7D12, SC124D12root, and W14D12root. This suggested that MeGIF2 may play a crucial role in the response to drought stress in these genotypes. For example, in Arg7D12, its high expression might be involved in regulating gene expression networks related to drought adaptation in this particular cassava variety.

MeGIF3 also exhibited elevated expression in many samples, indicating its importance in the overall response to drought. In contrast, MeGIF5 had a lower expression level in most samples, which demonstrated that its function may not be as prominent under drought conditions or that it may be regulated differently compared to other MeGIF genes.

Figure 7.

Expression profiles of MeGRF and MeGIF genes in different tissues of three cassava genotypes. FPKM value was used to create the heat map. The scale represents the relative signal intensity of FPKM values. (o) Expression profiles of MeGRF genes in different tissues of three cassava genotypes. (p) Expression profiles of MeGIF genes in different tissues of three cassava genotypes.

Figure 7.

Expression profiles of MeGRF and MeGIF genes in different tissues of three cassava genotypes. FPKM value was used to create the heat map. The scale represents the relative signal intensity of FPKM values. (o) Expression profiles of MeGRF genes in different tissues of three cassava genotypes. (p) Expression profiles of MeGIF genes in different tissues of three cassava genotypes.

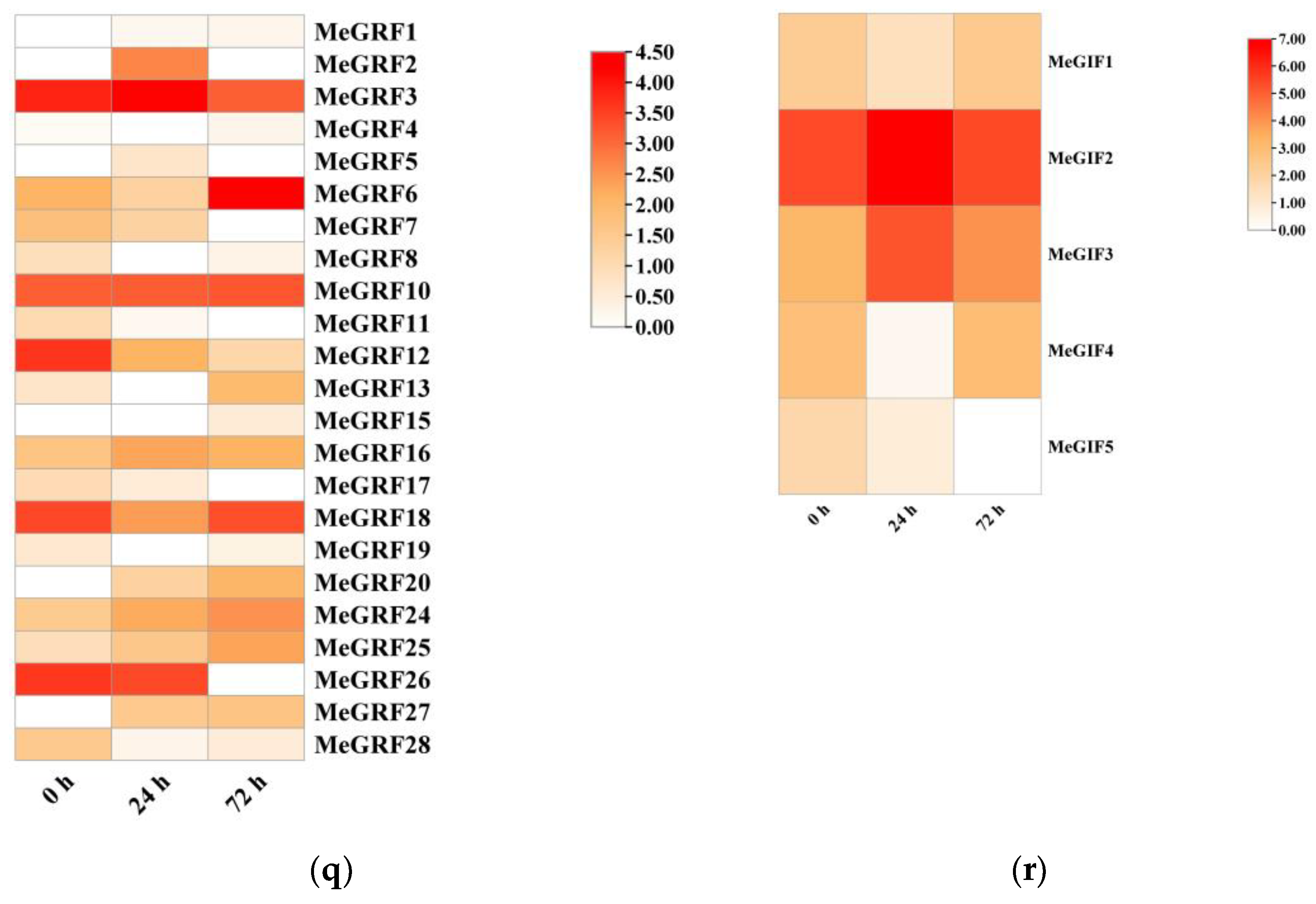

To further explore the responses of GRF and GIF to insect infestation in cassava, we analyzed the transcriptome data of cassava after 0 h, 24 h and 72 h after insect infestation. In the heatmap of MeGRFs, different genes exhibited distinct expression profiles over time under insect pest stress. MeGRF3 exhibited elevated expression levels at 0 h, 24 h, and 72 h, indicating its continuous involvement in the response of plants to insects. This gene might play a fundamental role in the basal defense mechanisms or regulatory processes related to pest resistance.MeGRF6 had particularly high expression at 72 h, suggesting that it may be involved in the later - stage response to insect pests. It could be regulating genes associated with long - term defense adaptations, like the synthesis of secondary metabolites that deter pests or the reinforcement of plant cell walls. Some MeGRF genes, like MeGRF4 and MeGRF14, showed lower expression level throughout the time points, which might imply that they are not major players in the insect pest stress response under these experimental conditions, or their functions are suppressed during pest attack.

For the MeGIFs heatmap, MeGIF2 showed a remarkable peak in expression at 24 h. This significant upregulation at this specific time point suggests that MeGIF2 may be a key regulator in the plant's immediate response to insect pests. It could be interacting with MeGRFs or other regulatory components to initiate defense - related gene expression cascades.MeGIF3 also had a higher expression level at 24 h and 72 h, indicating its continuous participation in the response process. It might collaborate with MeGIF2 or other MeGIFs to gradually adjust the plant's defense mechanisms.MeGIF4 and MeGIF5 displayed lower expression levels compared to MeGIF2 and MeGIF3, especially at 24 h. Their relatively subdued expression might suggest that they have less prominent roles in the initial and mid - stage responses to insect pests. However, they could still be engaged in other elements of the overall stress response at various times or under particular circumstances.

Figure 8.

Expression profiles of cassava GRF and GIF genes under insect pest stress.(q) Expression profiles of cassava GRF genes under insect pest stress.. (r) Expression profiles of cassava GRF and GIF genes under insect pest stress.

Figure 8.

Expression profiles of cassava GRF and GIF genes under insect pest stress.(q) Expression profiles of cassava GRF genes under insect pest stress.. (r) Expression profiles of cassava GRF and GIF genes under insect pest stress.

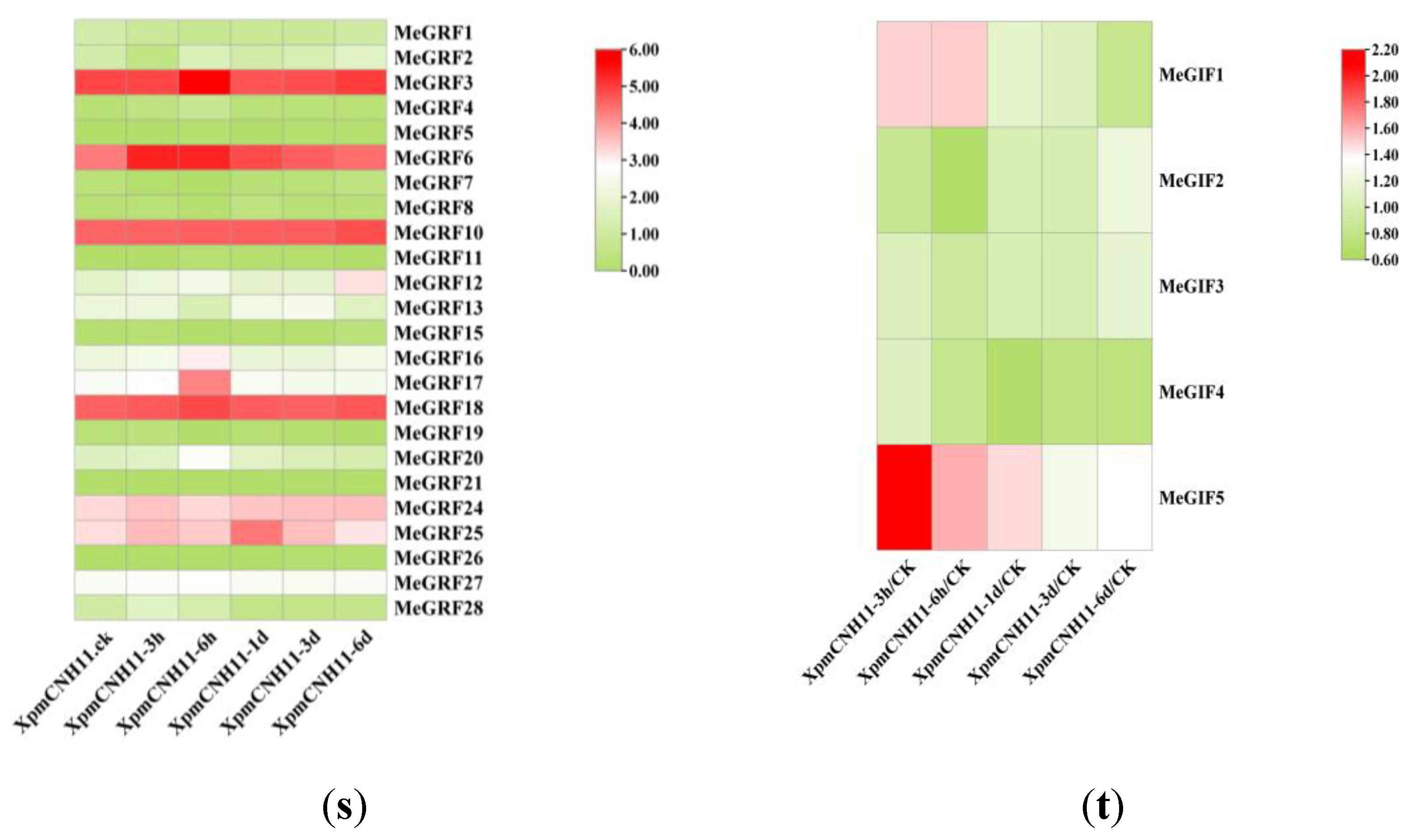

We performed transcriptomic analysis of MeGRF and MeGIF genes at different time points after infection with

XpmCNH11. The results showed that the expression levels of MeGRF genes initially increased and then decreased over time compared to the 0 h control. However, the timing of peak expression varied among different MeGRF genes, occurring at 3 h, 6 h, 1 day, 3 days, or 6 days. The expression levels of each gene were distinguishing, and the overall expression levels of MeGRF3, MeGRF6, MeGRF10, MeGRF18, and MeGRF25 were higher than those of other genes. Most gene traits were initially upregulated and then downregulated (e.g., MeGRF3, MeGRF6, MeGRF17, MeGRF18, and MeGRF25), but MeGRF9, MeGRF22, and MeGRF23 were not expressed in transcriptome data. In 25 MeGRF genes, varying degrees of response expression were observed. Specifically, MeGRF1, MeGRF7, and MeGRF26 mainly showed late responses, while genes with high expression levels (MeGRF6 and MeGRF28) all showed early responses. These results indicated that

XpmCNH11 induction could affect the expression of the cassava GRF gene for some time. In MeGIFs, although the expression levels of individual genes varied significantly, a clear overall trend of upregulation was observed. MeGIF1, MeGIF4, and MeGRF5 were predominantly expressed during the early stage, whereas MeGIF2 and MeGIF3 showed higher expression in the late stage(

Figure 7).

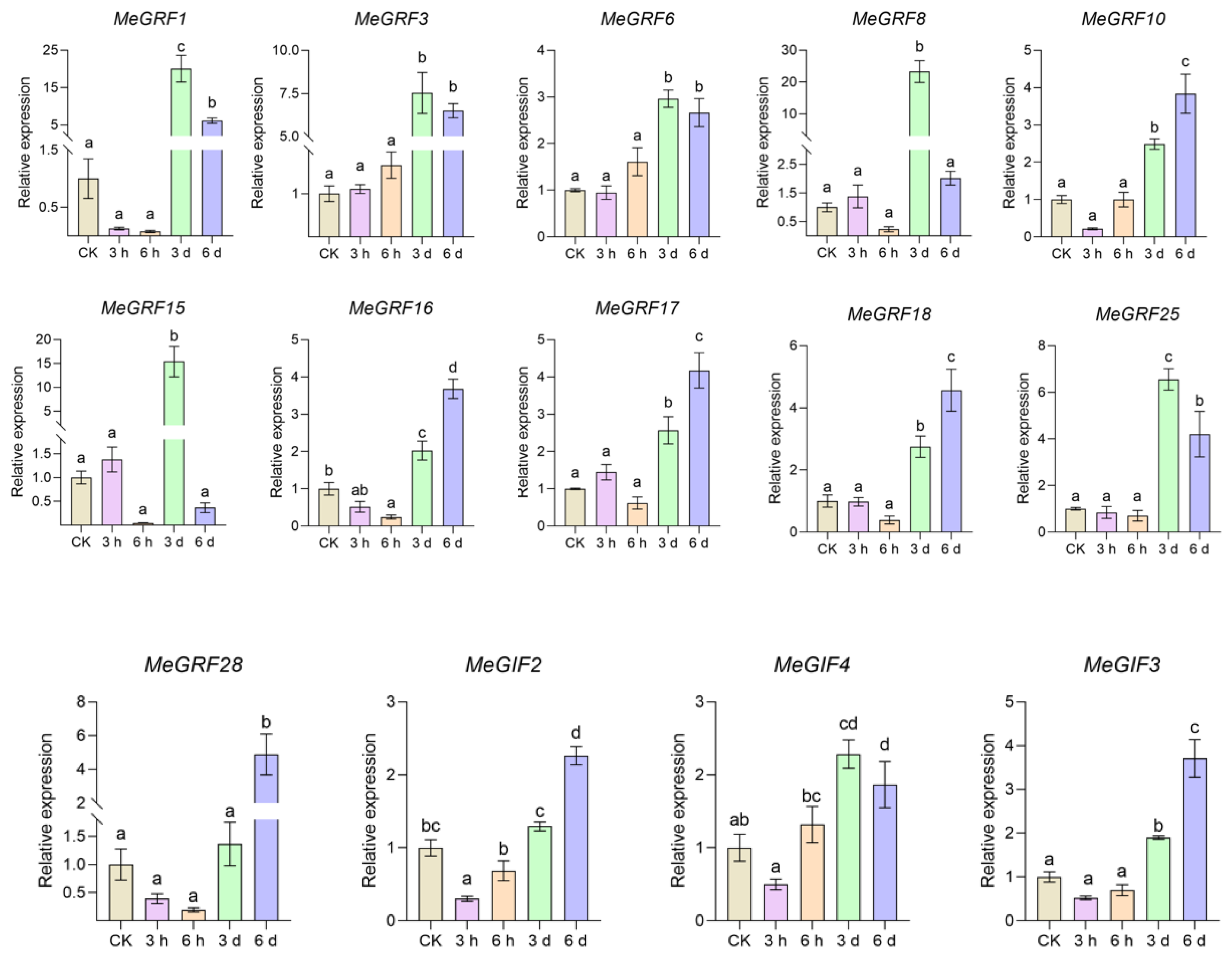

3.5. RNA Extraction and Real-Time PCR

The results of qPCR analysis of the MeGRF gene in cassava under XpmCNH11 infection revealed diverse and dynamic expression patterns. In the early stages of infection (3 h and 6 h later), most genes such as MeGRF3, MeGRF6, and MeGRF8 exhibited lower expression levels with higher statbility, , which displayed weaker immediate response compared to the control group. Over time to day 3, several genes were significantly upregulated, suggesting that they were involved in defense responses, including MeGRF3, MeGRF6, and MeGRF8. By day 6, while some genes, such as MeGRF10, MeGRF16, and MeGRF17, continued to be highly expressed, others, such as MeGRF8 and MeGRF15, returned to early-stage levels, and some genes were significantly upregulated at day 6, such as MeGRF28. This suggested that different MeGRF genes had different temporal functions in cassava defense against XpmCNH11. Some genes are essential for long-term resistance, while others are more short-lived in specific defense phases. These genes constitute a coordinated and time-varying defense network, highlighting the complexity of cassava’s molecular response to XpmCNH11 infection.

The qPCR results of MeGIF2, MeGIF3, and MeGIF4 in cassava under

XpmCNH11 infection showed distinctive time-dependent expression patterns. MeGIF2 gradually increased in expression over time, MeGIF3 had low expression initially and upregulates later, while MeGIF4 showed a pattern of initial low expression with a peak at 3 d and a slight decrease at 6 d. These genes likely contributed to a coordinated defense response, with their expressions finely tuned for optimal resistance at different infection stages, providing key insights into cassava’s anti-pathogen molecular mechanisms(

Figure 8).

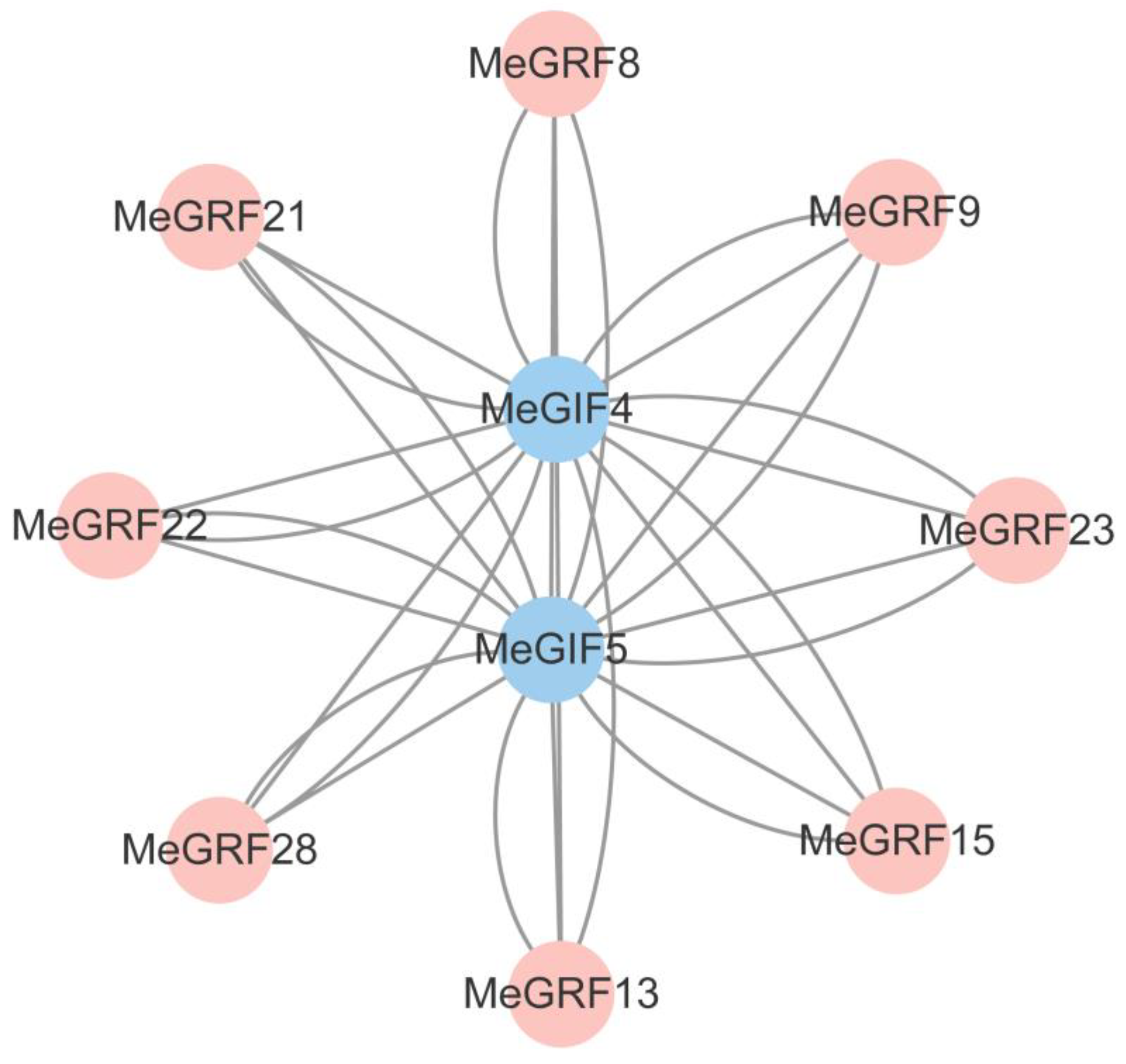

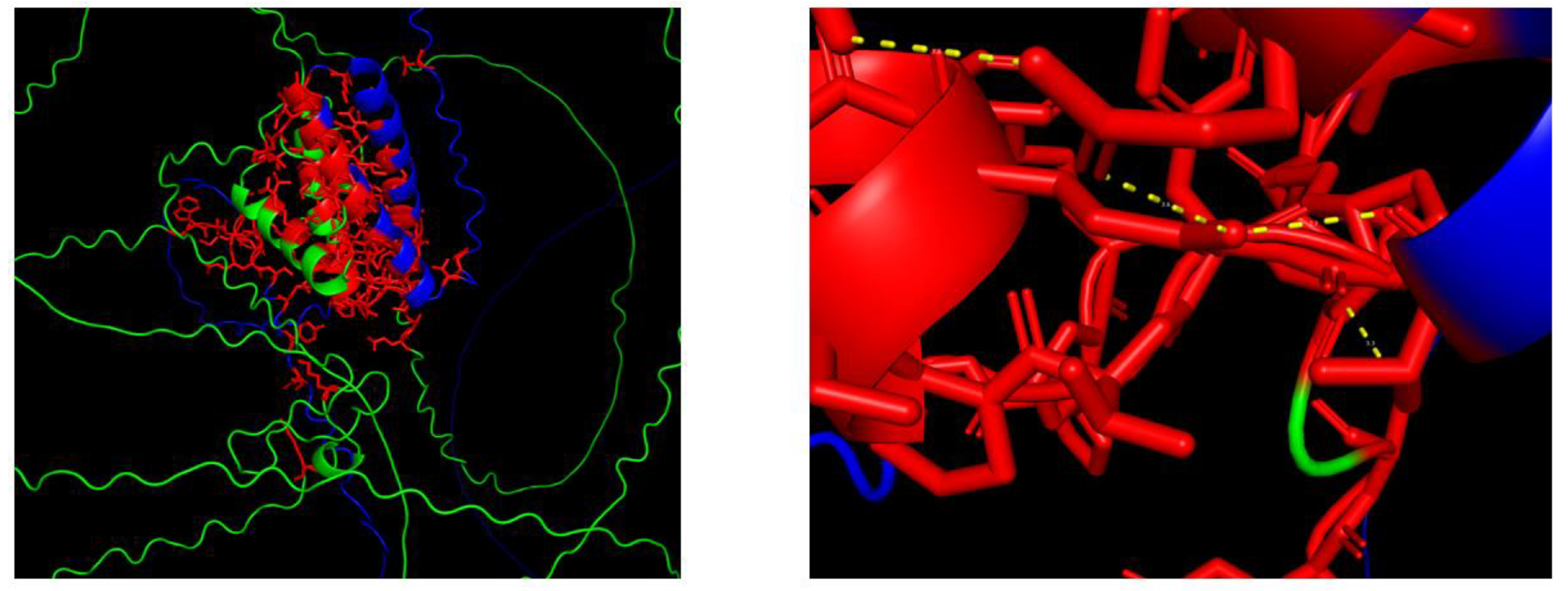

3.6. Interaction Analysis Between MeGRFs and MeGIFs Family Proteins

The protein-protein interaction map depicted relationships between MeGIF4, MeGIF5 (in blue), and several MeGRF genes (in pink) in cassava,which suggested that MeGIF4 and MeGIF5 may interact with these MeGRF proteins, By predicting the interaction domain between MeGRF28 and MeGIF4 protein, the interface area (Å2) of the protein interaction surface was 345.3, and the free energy was -2.9 (ΔiG kcal/mol) under this docking mode. Usually less than zero free energy corresponds to a meaningful docking result.likely forming complexes to modulate various biological processes. These interactions could be crucial for coordinating gene expression and physiological responses in cassava, such as growth regulation or stress responses. Understanding these interactions can provide insights into the molecular mechanisms underlying cassava’s development and adaptation(

Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Interaction analysis of GRF and GIF proteins. Red circles represent GRF proteins, whereas blue circles represent GIF proteins.

Figure 9.

Interaction analysis of GRF and GIF proteins. Red circles represent GRF proteins, whereas blue circles represent GIF proteins.

Figure 10.

Visualization analysis of the interaction domain between MeGRF28 and MeGIF4 proteins. Green represents MeGRF, blue represents MeGIF, red represents interacting amino acids, and yellow represents polar covalent bonds.

Figure 10.

Visualization analysis of the interaction domain between MeGRF28 and MeGIF4 proteins. Green represents MeGRF, blue represents MeGIF, red represents interacting amino acids, and yellow represents polar covalent bonds.

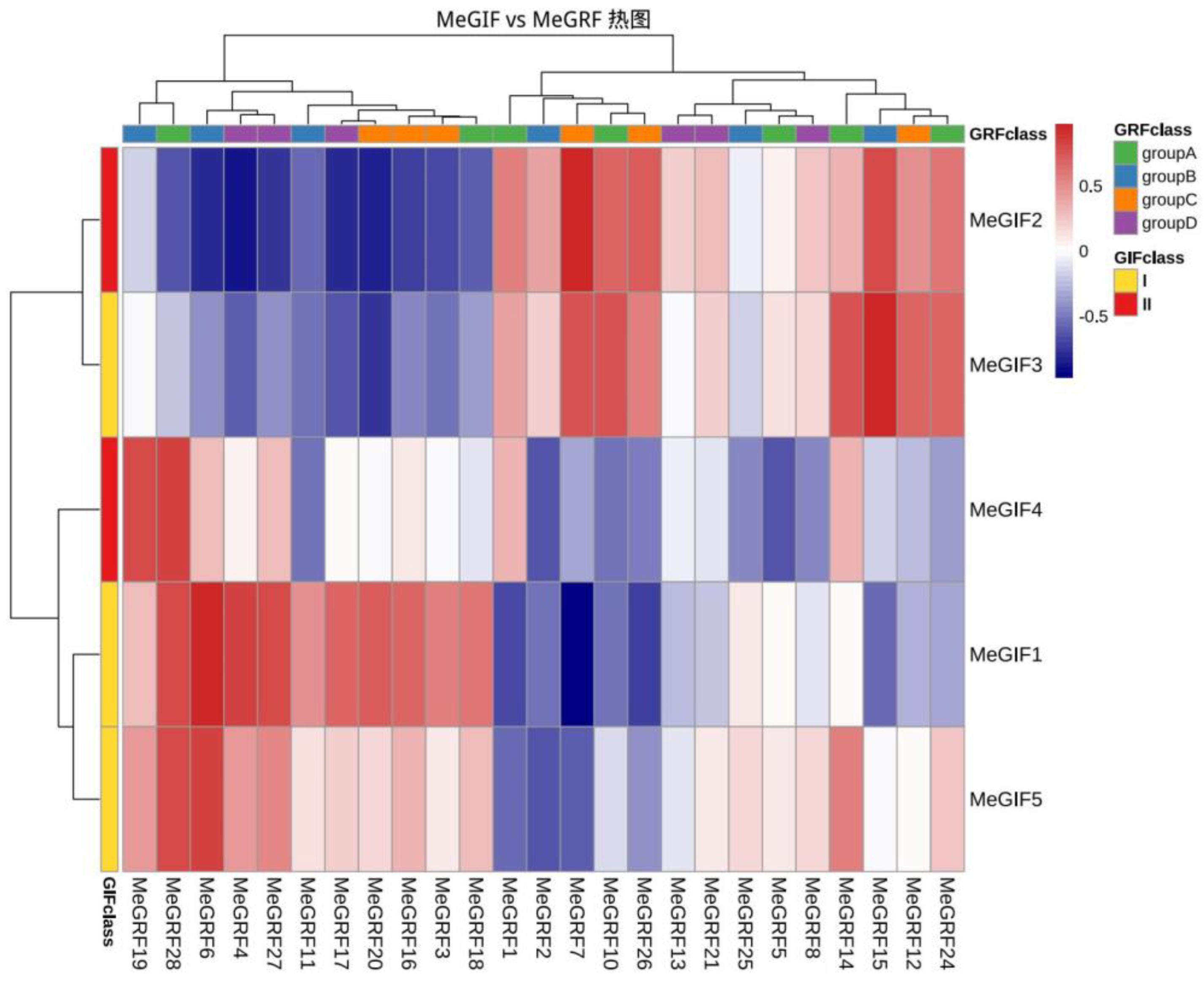

3.5. Coexpression Analysis Between MeGRFs and MeGIFs

To further understand whether there is a regulatory relationship between cassava GIF and GRF genes, the correlation between MeGIFs and MeGRFs was analyzed. Coexpression heat maps of MeGRFs and MeGIFs genes revealed the relationship between MeGIF and MeGRF gene families in cassava

XpmCNH11 infection. During the examination process of phylogenetic tree analysis, we concentrated on MeGRF28 due to its significant similarity to OsGRF6, which has been demonstrated to improve rice yield and aid in resistance to bacterial blight. The coexpression network also showed that the expression levels of MeGRF28 were higher with MeGIF1, MeGIF4 and MeGIF5 (correlation r value greater than 0.5) (

Figure 10). The expression levels of MeGIF and MeGRF genes were highly correlated, indicating that there was a regulatory relationship between these genes.(MeGRF6 and MeGIF1,MeGIF5;MeGRF15 and MeGIF3;MeGRF7 and MeGIF3)(

Figure 10).

Figure 1.

Chromosomal mapping of cassava MeGRFs and MeGIFs. The ratio represents megabases (Mb). The chromosome number is displayed to the left of each vertical bar. (a) Chromosomal mapping of cassava MeGRFs; (b) cassava MeGIFs.

Figure 1.

Chromosomal mapping of cassava MeGRFs and MeGIFs. The ratio represents megabases (Mb). The chromosome number is displayed to the left of each vertical bar. (a) Chromosomal mapping of cassava MeGRFs; (b) cassava MeGIFs.

Figure 2.

Phylogenetic analysis of MeGRFs and MeGIFs in cassava. (c) Phylogenetic tree of GRF genes in cassava, Arabidopsis, and rice. The star represents Arabidopsis, the circle represents rice, and the square represents cassava.; (d) Phylogenetic tree of GIF genes in cassava, Arabidopsis, rice, and tomato. The star represents cassava, the circle represents Arabidopsis, the square represents tomato, and the check mark represents rice.

Figure 2.

Phylogenetic analysis of MeGRFs and MeGIFs in cassava. (c) Phylogenetic tree of GRF genes in cassava, Arabidopsis, and rice. The star represents Arabidopsis, the circle represents rice, and the square represents cassava.; (d) Phylogenetic tree of GIF genes in cassava, Arabidopsis, rice, and tomato. The star represents cassava, the circle represents Arabidopsis, the square represents tomato, and the check mark represents rice.

Figure 3.

Conserved domain of cassava MeGRFs and MeGIFs. Conserved motifs in MeGRF and MeGIF genes were detected using MEME. Boxes of different colors represent ten different motifs. (d) Conserved domain of MeGRFs; (e) Conserved domain of MeGIFs.

Figure 3.

Conserved domain of cassava MeGRFs and MeGIFs. Conserved motifs in MeGRF and MeGIF genes were detected using MEME. Boxes of different colors represent ten different motifs. (d) Conserved domain of MeGRFs; (e) Conserved domain of MeGIFs.

Figure 4.

The C-terminal region of GRF proteins is less conserved and contains additional motifs such as TQL (Thr, Gln, Leu), FFD (Phe, Phe, Asp), and GGPL (Gly, Gly, Pro, Leu).

Figure 4.

The C-terminal region of GRF proteins is less conserved and contains additional motifs such as TQL (Thr, Gln, Leu), FFD (Phe, Phe, Asp), and GGPL (Gly, Gly, Pro, Leu).

Figure 5.

Type and number of cis-acting elements in the MeGRFs and MeGIFs gene promoter. (i) Cis-acting element analysis of the MeGRFs family genes. (h) Cis-acting element analysis of the MeGRFs family genes. There are four directions of light response element, hormone response, growth and development, and environmental stress: the light reaction element, the hormone response related element., growth and development, and the environmental stress element.

Figure 5.

Type and number of cis-acting elements in the MeGRFs and MeGIFs gene promoter. (i) Cis-acting element analysis of the MeGRFs family genes. (h) Cis-acting element analysis of the MeGRFs family genes. There are four directions of light response element, hormone response, growth and development, and environmental stress: the light reaction element, the hormone response related element., growth and development, and the environmental stress element.

Figure 6.

Expression patterns of cassava GRF and GIF Expression in different tissues. (k) Expression patterns of cassava GRF Expression in different tissues. (l) Expression patterns of cassava GIF Expression in different tissues. OES, Somatic embryos; FEC, Brittle calluses; FR, Fibrous roots; SR, Root tubers; RAM, Root tips; SAM, Stem apexes were tested. The bar at the right of the heatmap represents the relative expression values; values < 0 represent downregulated expression, and values > 0 represent upregulated expression.

Figure 6.

Expression patterns of cassava GRF and GIF Expression in different tissues. (k) Expression patterns of cassava GRF Expression in different tissues. (l) Expression patterns of cassava GIF Expression in different tissues. OES, Somatic embryos; FEC, Brittle calluses; FR, Fibrous roots; SR, Root tubers; RAM, Root tips; SAM, Stem apexes were tested. The bar at the right of the heatmap represents the relative expression values; values < 0 represent downregulated expression, and values > 0 represent upregulated expression.

Figure 7.

Expression profiles of cassava GRF and GIF genes in response to the XpmCNH11 (s) Expression profiles of cassava GRF genes in response to the XpmCNH11 (t) Expression profiles of cassava GIF genes in response to the XpmCNH11.

Figure 7.

Expression profiles of cassava GRF and GIF genes in response to the XpmCNH11 (s) Expression profiles of cassava GRF genes in response to the XpmCNH11 (t) Expression profiles of cassava GIF genes in response to the XpmCNH11.

Figure 8.

Expression analysis of MeGRFs and MeGIFs in response to XpmCNH11.

Figure 8.

Expression analysis of MeGRFs and MeGIFs in response to XpmCNH11.

Figure 10.

Coexpression of GIF and GRF genes under pathogen stress. Red indicates a high correlation, and blue indicates a low correlation. The FPKM values of MeGRF and MeGIF gene families under XpmCNH11 infection were calculated using the R software package “Hmisc.” The Pearson correlation between the GRF and GIF families was calculated.

Figure 10.

Coexpression of GIF and GRF genes under pathogen stress. Red indicates a high correlation, and blue indicates a low correlation. The FPKM values of MeGRF and MeGIF gene families under XpmCNH11 infection were calculated using the R software package “Hmisc.” The Pearson correlation between the GRF and GIF families was calculated.