1. Introduction

The Chloranthaceae family, an early-diverging lineage of angiosperms, has long captivated biologists due to its unique combination of ancestral traits. Its vascular system exclusively contains scalariform perforation plates [

1], a characteristic shared with ancient ANA-grade taxa of flowering plants. The frequent absence of perianth structures in Chloranthaceae flowers exhibits remarkable convergence with Piperales members (Saururaceae and Piperaceae) and basal monocots [

2,

3]. Paleobotanical evidence positions Chloranthaceae fossils as one of the most extensively distributed early angiosperm fossil groups during the Early Cretaceous [

4]. The global occurrence of these fossils, particularly pollen fossils demonstrating striking morphological continuity with living Chloranthaceae species [

5], provides critical insights into the diversification patterns and biogeographic dispersal of the early angiosperms.

Chloranthaceae species are pharmacologically significant for their specialized metabolites, particularly diverse terpenoids [

6] and coumarin derivatives [

7]. Terpenoid metabolism has been relatively well-characterized in early angiosperms [

5,

8]. However, coumarin biosynthesis remains incompletely understood and persistently overlooked. The phytochemicals not only define the family’s distinctive biological properties but also play crucial roles in plant defense mechanisms. Under environmental stressors including pathogen attack, insect herbivory, nutrient deprivation, and growth restriction, Chloranthaceae species exhibit upregulated biosynthesis and compartmentalization of coumarins as an evolutionary conserved protective strategy [

9]. Among these secondary metabolites, isofraxidin (7-hydroxy-6, 8-dimethoxycoumarin) stands out as a representative dihydroxycoumarin compound [

10]. As a bioactive constituent, isofraxidin demonstrates pleiotropic pharmacological activities through modulation of key inflammatory mediators: nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB), tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), and matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), highlighting its therapeutic potential in inflammatory regulation [

11,

12].

Although isofraxidin plays a crucial role in plant stress resistance and bioactivity, its biosynthetic pathway remains unresolved due to inadequate functional annotation of pivotal enzyme-encoding gene families, such as CYP71 P450s and O-methyltransferases (OMT) in early-diverging angiosperms. Conventional botanical extraction remains the primary method for obtaining isofraxidin to date. However, this approach suffers from low efficiency due to the compound’s natural scarcity in plants and raises environmental sustainability concerns. Here, we generated a high-quality genome assembly of the autotriploid cultivar Chloranthus erectus using multiple advanced technologies. Through comparative genomics analysis, we validated the evolutionary position of Chloranthaceae as a critical lineage in angiosperm evolution. By integrating genomics, transcriptomics, and metabolomics datasets, we elucidated the biosynthetic pathway and accumulation patterns of isofraxidin in C. erectus. This study establishes the genomic foundations of chemical defense evolution in early-diverging angiosperm lineages, deciphering specialized metabolic systems to advance engineered production of plant-derived antimicrobials.

2. Results

This section may be divided by subheadings. It should provide a concise and precise description of the experimental results, their interpretation, as well as the experimental conclusions that can be drawn.

2.1. Chromosome-Scale Genome Assembly and Annotation

Using PacBio HiFi sequencing (122.62 Gb) combined with Illumina short-read data (227.40 Gb), we generated a 8.57 Gb triploid genome for

C. erectus with 99% sequence anchored to 45 chromosomal pseudomolecules through Hi-C scaffolding (

Table 1,

Tables S1-S6). The assembly achieved 8.76 Mb contig N50 and 94.35% BUSCO [

13] completeness (

Table S7-S8), showing superior contiguity compared to other triploid plant genomes like cultivated bananas [

14]. Integrated annotation combining transcriptomic and homology evidence identified 72, 675 protein-coding genes (average CDS length 1, 154 bp) with 92.7% functional annotation rate (

Tables S9-S11). Comparative analysis revealed high gene content conservation across homologous chromosomes, while Hi-C interaction maps resolved three-dimensional chromatin architecture. Chromosomal organization was validated by cytogenetic analysis confirming 3x = 45 karyotype (

Figure 1,

Figure S1).

2.2. Transposable Element Accumulation and Whole Genome Duplication

Analysis of transposable elements (TEs) and whole genome duplication (WGD) events revealed significant genomic evolutionary drivers in

C. erectus [

15]. Combined homolog-based and structure-based analyses identified 6315.87 Mb TEs occupying 73.7% of the assembled genome (

Table S13), exceeding TE content in most angiosperms, as well as ginkgo (>70%) [

16] and pine (69.4%) [

17]. Long terminal repeats (LTRs) dominate (63.54% of genome), suggesting slow TE clearance mechanisms similar to pine [

16], contributing to

C. erectus’ large genome size.

Comparative genomic analysis using monoploid chromosome representatives detected a single WGD event through Ks distribution and 4DTv analyses (

Figure 2B, C). The Ks peak at 1.1~ and calculated divergence rate (4.339821e-09/year) dated this event to 126.7 Mya. Phylogenetic comparisons with

Amborella [

18] and Magnoliaceae confirmed this paleopolyploidy event was unique to Chloranthaceae (

Figure 2D).

2.3. Phylogenetic Reconstruction

The phylogenetic relationships among Magnoliids, Monocots, and Eudicots continue to present unresolved questions in angiosperm evolution [

19]. Leveraging genomic data from early-diverging angiosperms, our study provides enhanced resolution of these critical evolutionary connections. Our comprehensive sampling encompassed 25 representative species across major plant lineages (

Table S14). A phylogenetically informative set of 1, 092 conserved low-copy nuclear genes (LCGs) was rigorously curated from whole-genome alignments to reconstruct maximum likelihood phylogenies with robust statistical support.

Chloranthus demonstrated strong phylogenetic affinity with core Magnoliids, forming a well-supported group (BS=100) that resolves as sister to the Eudicot clade (

Figure 2D). This topology aligns with current models positioning Magnoliids as a paraphyletic lineage ancestral to core eudicots [

20]. Systematic subsampling further revealed exceptional topological concordance across analytical frameworks, evidenced by consistent results from 1092 LCGs and 517 LCGs optimized for site-heterogeneous models (

Figure S7). Finally, a coalescent-based species tree reconstructed from 1, 092 LCGs delineated three angiosperm lineages with high confidence: Monocots,

Chloranthus + Magnoliids, and Eudicots.

2.4. Expansion of Disease Resistance-Related Gene Families

The analysis of gene families showed that 48843 gene families were clustered in 25 species, of which 3361 gene families were shared. The corresponding clustering results of the genomes of

C.erectus and four Magnoliids species,

P.nigrum,

L.chinense,

M.biondii and

P.americana were extracted, and it was found that the number of gene families they shared was 7057 (

Figure 2A), which may represent the core gene families of Chloranthales and related Magnoliids.

Genome-specific analysis revealed the dynamic evolution of gene families in

C. erectus, identifying 138 gene families (containing 1, 310 genes) that showed significant expansion (

Figure 2D), and 144 gene families (containing 128 genes) that underwent contraction. Notably, genes related to plant-pathogen interactions were found to be significantly expanded and enriched (

Figure 2E). The KEGG plant-pathogen interaction pathway integrates a multi-level gene network ranging from pathogen recognition (PRRs), signal transduction (MAPK, calcium signaling), transcriptional regulation (WRKY, NPR) to defense execution (ROS, PR proteins). The coordinated action of these genes helps plants balance defense and growth and resist pathogen invasion through PTI and ETI mechanisms. The coordinated expansion of these immune-related loci suggests an evolutionary arms race between

C. erectus and its ancestral pathogens, which may explain the successful adaptation of the

Chloranthus genus to a wide range of ecological environments.

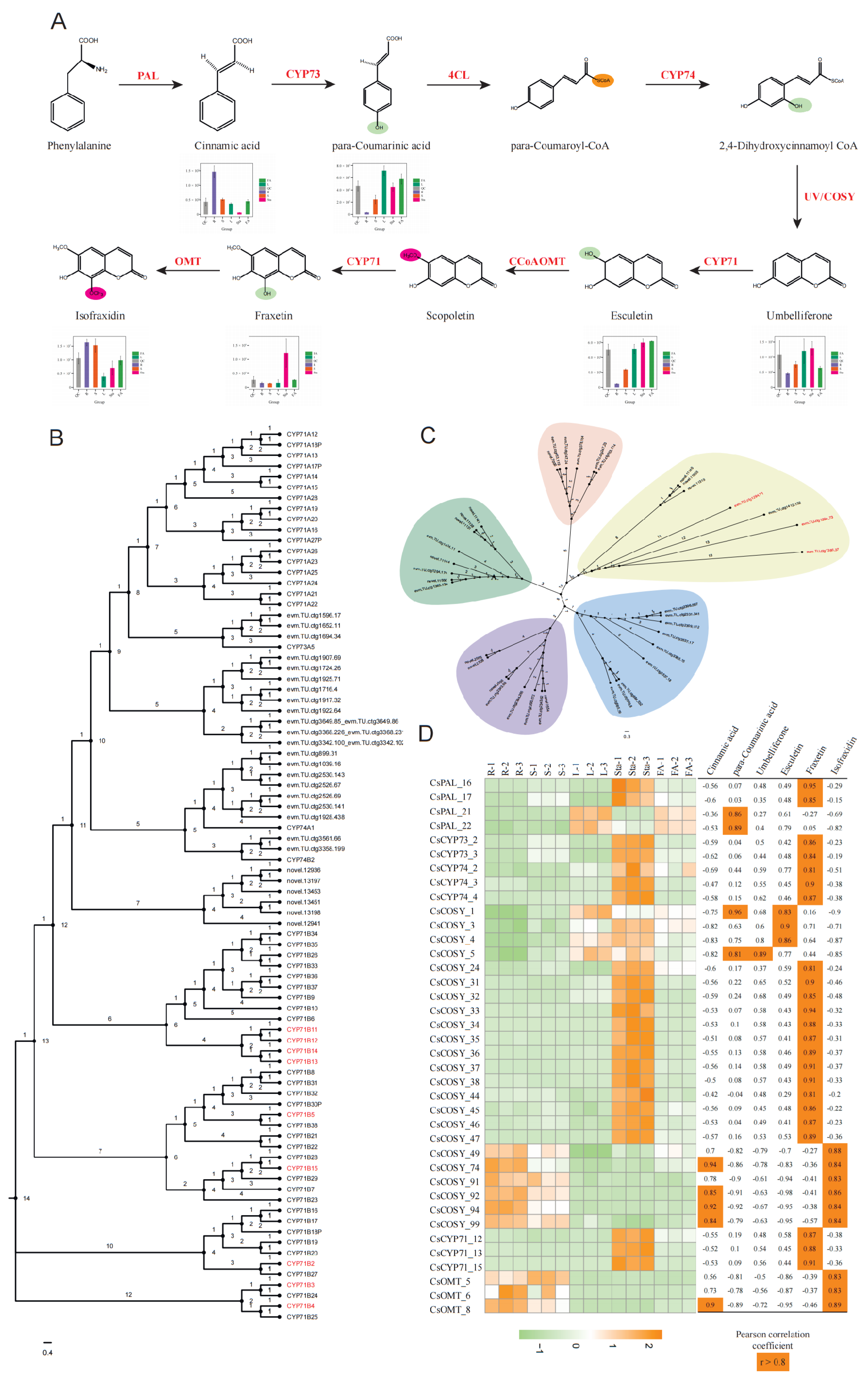

2.5. Biosynthesis of Isofraxidin

2.5.1. Characteristics of Coumarin Biosynthetic Pathways in Early Angiosperms

The coumarin backbone is derived from phenylalanine, which undergoes deamination catalyzed by phenylalanine ammonia-lyase (PAL), resulting in the formation of trans-cinnamic acid. This intermediate is subsequently hydroxylated at the para position by cinnamic acid 4-hydroxylase (C4H, CYP73) to yield p-coumaric acid. The carboxylic acid is then activated by 4-coumaroyl-CoA ligase (4CL) to generate 4-coumaroyl-CoA (para-Coumaroyl-CoA). Ortho-hydroxylation of 4-coumaroyl-CoA at the C2′ position is catalyzed by coumaroyl-CoA 2′-hydroxylase (C2′H, CYP74) to yield the unstable intermediate 2′, 4′-dihydroxycinnamoyl-CoA. Recent studies have demonstrated that coumarin synthase (COSY), a member of the BAHD acyltransferase family, facilitates the spontaneous cyclization of this intermediate into umbelliferone [

21], which serves as the universal scaffold for coumarin derivatives (

Figure 3).

From umbelliferone, coumarin biosynthesis diverges into simple coumarins and complex coumarins (pyranocoumarins and furanocoumarins). Simple coumarins are mainly subjected to substitutions at positions C3–C8 and functional group modifications on the core nucleus. In contrast, the biosynthesis of complex coumarins initiates with the prenylation of umbelliferone. Prenyltransferases mediate the attachment of prenyl groups at either the C6 or C8 position, producing 6-prenylumbelliferone or 8-prenylumbelliferone, respectively [

22]. The 6-substituted derivatives are subsequently cyclized by angular-type cyclases to form pyranocoumarins, whereas the 8-substituted derivatives undergo cyclization by linear-type cyclases to yield furanocoumarins.

Metabolome-wide profiling in

Chloranthus identified 49 distinct coumarin metabolites (

Table S19), representing a quantitatively significant expansion over previously documented occurrences [

23]. Structurally, the majority constituted most of them are simple coumarins, such as daphnetin, fraxidin and scopolin. Additionally, we identified structurally diversified derivatives, including cleomiscosin A/C. Crucially, pyranocoumarin and furanocoumarin subclasses, which characteristic of Apiaceae and Rutaceae, were nearly absent across all parts in this species. This chemotaxonomic gap implies substantially reduced biosynthetic capability for prenylation and dehydrative cyclization reactions catalyzed by PTs and DC/OC enzymes, respectively. We propose that limited transcriptional activation or catalytically constrained orthologs of these pathway-specific enzymes result in negligible metabolic flux toward downstream heterocyclic coumarin biosynthesis.

2.5.2. Integrated Transcriptomic-Metabolomic Elucidation of the Isofraxidin Biosynthetic Pathway

To further elucidate the biosynthetic mechanism of the representative simple coumarin molecule, isofraxidin, which is the focus of this study, as well as to identify its key regulatory genes, this research systematically conducted gene mining based on the formation of umbelliferone and subsequent modification steps specific to simple coumarins. Through comprehensive functional annotation, orthologous best-matching clustering, and phylogenetic analysis in

Chloranthus species, we systematically identified core gene families governing isofraxidin biosynthesis and their cascade catalytic mechanisms. A total of 267 candidate genes from 9 pivotal gene families (PAL, CYP73, C4L, CYP74, COSY, CYP71, CCoAOMT, OMT) were characterized. Notably, the COSY family exhibited significant expansion (115 members vs. 29 in

Arabidopsis, P<0.01), while other families displayed distinct evolutionary patterns: PAL (22), CYP73 (3), C4L (56), CYP74 (9), CYP71 (15), CCoAOMT (9), and OMT (38), indicating differential gene duplication strategies among these families to meet metabolic demands during evolution. Spatial expression profiling revealed tissue-specific patterns that COSY members showed distinct expression in roots, stems, leaves, and stamens, CYP71 subfamily members demonstrated root (CYP71_5-10), leaf (CYP71_1-4), and stamens (CYP71_11-15) specificity, while OMT_5-22 and OMT_23-26 exhibited predominant expression in roots and stems, respectively (

Figure 4).

Our UPLC-MS/MS analysis validated key pathway intermediates. The initial conversion of phenylalanine to cinnamic acid by PAL showed maximum catalytic activity in root tissues, correlating with significant cinnamic acid accumulation. Subsequent CYP73-mediated hydroxylation generated para-coumarinic acid, preferentially accumulated in leaves, stamens, and floral axis. CYP74 catalysis transformed this intermediate into 2, 4-dihydroxycinnamic acid, which underwent COSY-driven cyclization to form umbelliferone. Metabolomic data revealed 2-fold higher umbelliferone levels in leaves and stamens compared to roots, with biosynthesis primarily attributed to COSY_1-21 and COSY_22-47 clusters (

Figure 5A). Transcriptome-metabolome integration demonstrated strong positive correlations between COSY expression and umbelliferone concentrations (r>0.85), underscoring their critical role in early-stage biosynthesis.

Downstream modifications were also delineated through integrated multi-omics analysis. CYP71_1-4 (leaf-specific, FPKM>1) catalyzed umbelliferone hydroxylation to esculetin, while CCoAOMT likely mediated subsequent methylation to scopoletin. Notably, CYP71_11-15 (stamen-specific, FPKM>1) potentially facilitated scopoletin-to-fraxetin conversion, establishing spatial metabolic decoupling. Despite ubiquitous esculetin accumulation (leaves, stamens and floral axis), fraxetin showed stamen-specific enrichment. This pattern strongly correlated with CYP71_11-15 expression. In particular, CYP71_12/13/15 showing Pearson correlation coefficients of 0.87, 0.88, and 0.91 with fraxetin levels, confirming their dominant role in this biosynthetic step (

Figure 5B, D). Concurrently, suppressed CCoAOMT expression in stamens (FPKM<1) likely diverted metabolic flux from lignin precursors to isofraxidin biosynthesis.

Final OMT-mediated methylation of fraxetin to isofraxidin involved 38 identified genes. Among these, OMT_5/6/8 demonstrated root/stem-predominant expression (FPKM>1) with strong correlations to isofraxidin accumulation (r=0.83/0.83/0.89) (

Figure 5C, D), directly implicating them in terminal methyl group transfer.

3. Discussion

Herbal genomics, an emerging research field, investigates the genetic and regulatory mechanisms of medicinal plants through genomic approaches to elucidate their bioactive principles and advance molecular breeding [

24,

25]. Genomic dissection of valuable natural product biosynthetic pathways provides critical insights for synthetic biology-driven compound synthesis and scalable production. Co-expression network analysis and genome mining are becoming indispensable strategies to accelerate the modernization of traditional medicinal plant research.

The biosynthesis of coumarins and associated genes has evolved independently multiple times in plants [

22]. As an early-diverging angiosperm,

Chloranthus accumulates diverse simple coumarins, among which isofraxidin—a compound with extensive clinical applications and significant pharmaceutical potential—warrants systematic investigation. Through integrated multi-omics analysis, this study elucidates the genetic basis of isofraxidin biosynthesis, offering the first comprehensive understanding of its metabolic regulation. Our findings reveal the remarkable complexity and evolutionary adaptability of plant secondary metabolism in

Chloranthus. Systematic identification of 9 key gene families (267 candidate genes) and their functional specialization within the metabolic cascade provides novel perspectives on coumarin regulation.

Recent studies have established the COSY-encoded enzyme as catalytically essential for coumarin biosynthesis in upstream pathway steps, revising the conventional model wherein cyclization was considered spontaneous [

21]. Consequently, COSY gene copy number expansion likely enhances umbelliferone production capacity. Notably, coumarin abundance exhibits significant divergence across angiosperm lineages. As a core scaffold for bioactive coumarins, COSY gene family amplification constitutes a pivotal driver.

Our analysis reveals a strong correlation between coumarin structural complexity and COSY ortholog numbers. While Arabidopsis thaliana contains merely 29 COSY orthologs, the Chloranthus genome exhibits substantial expansion with 115 members—indicating near four-fold paralog proliferation. This disparity in gene family size underscores key gene family expansion events during plant evolution and their concomitant functional diversification processes. These mechanisms represent core drivers of evolutionary innovation, providing the genetic foundation for novel trait development and environmental adaptation. We further infer that Chloranthus’ adoption of this proactive gene duplication strategy likely reflects profound adaptation to specific ecological niches. For instance, possessing an expanded COSY gene repertoire may significantly enhance the species’ capacity to counteract biotic stresses, particularly in pathogen defense. Numerous and potentially specialized COSY genes could support the synthesis of more complex, potent, or rapidly responsive coumarin-based defense compound libraries. Genomic alterations supply raw materials for metabolic innovation, while environmental pressures act as selective filters that fix genetic variants conferring adaptive advantages.

Our analysis of the CYP71 subfamily reveals tissue-specific functional partitioning among its members. Subclades CYP71_1-4 exhibit high expression in leaf tissues, where they catalyze the hydroxylation of umbelliferone to yield esculetin. Conversely, isoforms CYP71_11-15 demonstrate stamen-specific expression and drive the conversion of scopoletin to fraxetin. This metabolic modularity strategy effectively minimizes cytotoxicity risks by confining potentially toxic intermediates (such as esculetin) to specialized tissues, while optimizing metabolic flux through spatial compartmentalization. Consequently, defense compound biosynthesis achieves precise spatiotemporal regulation.

Gene family functional stratification is equally notable. The final step of isofraxidin biosynthesis requires an OMT for methylation. Transcriptomics identified OMT_5, OMT_6, and OMT_8 with rhizome-specific high expression (FPKM > 1), showing strong positive correlation with isofraxidin accumulation (r = 0.83–0.89, P < 0.01). Among 38 screened OMT genes, only these three core members significantly associate with target metabolite production. This finding indicates strict spatiotemporal and functional stratification within the OMT family. Core isoforms OMT_5/6/8 specifically dominate isofraxidin biosynthesis in rhizomes, while paralogs participate in divergent pathways—such as lignin synthesis (

Eucalyptus CCoAOMT homologs) or flavonoid modification (

Citrus CrcCCoAOMT7 homologs) [

26,

27].

Collectively, this study elucidates the biosynthetic pathway of isofraxin, a key coumarin in Chloranthus, and substantiates the paradigm of “one gene family, multiple functions; one metabolic pathway, multiple genes.” This genomic plasticity-driven mechanism of metabolic innovation likely represents a pivotal evolutionary strategy that facilitated the ecological success of early angiosperms, including members of the Chloranthaceae family, in response to the complex environmental pressures of the Cretaceous.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Materials and Sequencing

Fresh leaves were collected from one individual of autotriploid

C. erectus (LYY202008). The samples were sent to Novogene (Beijing, China) for DNA extraction and sequencing. Chromosomes were checked using root tips from plants. After staining with DAPI, photographs were taken under a fluorescent microscope (Leica DM2500) in dark. Determine its karyotype as 3X = 45. Genome size was estimated using

K-mer analysis of Illumina 150 bp paired-end reads. The

K-mer depth-frequency distribution was generated using jellyfish v.2.2.7 [

28].

DNA was extracted from leaves using the DNAsecure Plant Kit (TIANGEN). The 15 Kb circular consensus sequencing (CCS) library was constructed and sequenced on the PacBio Sequge II platform. Short reads genomic library was prepared and sequenced using the Illumina HiSeq platform. Young leaf samples were processed and DNA extracted using standard protocols, and a 350 bp Hi-C library was sequenced on an Illumina HiSeq instrument.

Roots (R), stems (S), leaves (L), stamens (Sta), and floral axis (FA) under normal growth conditions were collected for metabolomics detection and transcriptome sequencing.

4.2. Genome Assembly

The 122.62 Gb (7 cells) Hifi reads were rapidly constructed using hifiasm v.0.14 [

29]. In order to evaluate the accuracy of the assembly, the reads of the small fragment library were aligned to the assembled genome using BWA v.0.7.10 [

30], and the alignment rate, the coverage of genome and the distribution of depth were counted. The presence of contamination was assessed using GC content and sequencing coverage analysis. We applied both CEGMA v.2.5 [

31] and BUSCO v.3.0 [

32] to assess the integrity of the assembly.

Hi-C data (510 Gb) was obtained on the Illumina HiSeq platform, and allhic [

33] was used for contig clustering, ranking and orientation. Then in Juicebox v.1.11.08 [

34], manual corrections were made according to the strength of chromosome interactions, and the final triploid chromosome assembly was generated, containing all 45 chromosomes.

4.3. Repeat Annotation

We used both homology-based and de novo-based strategies to identify transposable elements (TEs). Firstly, RepeatMasker v.4.0.7 [

35] and RepeatProteinMask are used to generate homology-based repeat libraries based on RepBase nucleic acid library and RepBase protein library, respectively. De novo predictions are then performed using RepeatModeler v.1.0.5 [

36], RepeatScout [

37], Piler [

38] and LTR_FINDER v.1.0.6 [

39]. All TEs data were integrated and de-redundant to obtain an integrated repeat library, which was finally annotated by RepeatMasker.

4.4. Protein-Coding Gene Prediction and Functional Annotation

Three complementary strategies, including denovo, homology, and RNA-seq based prediction were used to annotate the protein-coding genes of the

C. erectus genome. Augustus v.3.0.2 [

40], Genscan v.1.0 [

41], Geneid [

42], GlimmerHMM v.3.0.3 [

43] and SNAP [

44] were run on the repeat-masked genomes to evaluate de novo gene predictions. For homolog-based prediction, we used the inferred protein sequences of four species, C. demersum, L. chinense, N. colorata and P. somniferum. Alignments were further processed using GeneWise v.2.2.0 [

45] to generate accurate exon and intron information. For transcriptome-based prediction, cufflinks v.2.1.1 [

46] and PASA 2.0.2 [

47] were used to predict and improve the gene structures. All predictions were combined using EVidenceModeler (EVM) v.1.1.1 [

48] to generate a non-redundant gene set, resulting in a final set of 72, 675 protein-coding genes.

4.5. Construction of Gene Families

We selected 25 species (A. trichopoda, A. comosus, A. coerulea, A. thaliana, C. demersum, C. kanehirae, C. esculenta, E. ferox, G. biloba, C. erectus, L. chinense, M. biondii, M. acuminata, N. nucifera, N. colorata, O. sativa, P. somniferum, P. americana, P. equestris, P. nigrum, S. lycopersicum, S. polyrhiza, T. sinense, V. vinifera, Z. marina) to construct gene families. Only the transcript with the longest coding region was reserved, and the similarity between protein sequences was obtained by all-vs-all blastp. Gene family clusters based on 25 species were then constructed using OrthoMCL v.2.0.9 [

49] with an inflation factor set as 1.5. Gene family expansion and contraction analysis was performed using CAFÉ v.4.2 [

50].

4.6. Phylogenetic Analyses

The SCG and LCG of 25 seed plants were identified using SonicParanoid v.1.0 [

51] and OrthoMCL v.2.0.9 [

49]. Finally, we identified 1092, 517, 299 and 27 homologous genes, respectively. Amino acid sequences were aligned using MUSCLE v.3.8.31 [

52]. For concatenated datasets, ModelFinder [

53] is used to automatically select the best-fit surrogate model. Maximum likelihood trees were inferred from the sequences using RaxML v.8.2.12 [

54], and support values were estimated using 500 bootstrap replicates. In the analysis based on coalescent approach, each gene tree was first constructed using IQ-TREE v.1.6.9 [

55], and then these trees are used to infer species tree with posterior probabilities in Astral v.5.6.1 [

56]. To estimate the timescales of the evolution of

Chloranthus, Magnoliids, Monocots and Eudicots, we calibrated a relaxed molecular clock with 2 well-established constraints: the divergence between angiosperms and gymnosperms (337–289 Ma) and the divergence between A. trichopoda and N. colorata (199–173 Ma) (

http://www.timetree.org/). Bayesian phylogenetic age analysis and approximate likelihood calculations for branch lengths were performed on selected genes using the program MCMCTree in PAML v.4.9 [

57,

58].

4.7. Identification of Whole-Genome Duplication

We selected four genomes of

C. erectus, A. trichopoda, L. chinense and C. kanehirae for polyploidy analysis based on previous studies [

20,

59]. For protein BLASTP within or between genomes, the cut-off value of e value is 1×10-5. According to the position of the genes and BLASTP results, McscanX v.2 [

60] was used to search for the collinear segment to determine homologous gene pairs. Protein-gene pairs were subjected to multiple sequence alignment in MUSCLE v.3.8.31 [

52]. The KS and 4DTv values for each homologous gene pair were estimated using the codeml method implemented in PAML v.4.9 [

58]. The distributions of the values were obtained by kernel function analysis, and they were further modeled as a mixture of multiple normal distributions by the kernel smoothed density function. Multimodal fitting of the curve was performed using the Gaussian approximation function (CfTool) in MATLAB.

4.8. UPLC/QTRAP-MS Metabolomic Analysis

Lyophilized tissues (root, stem, leaf, stamen, floral axis; 50 mg/sample) were pulverized at 30 Hz for 1.5 min (MM 400 grinder, Retsch), then extracted with 1200 μL of -20°C pre-cooled 70% methanol containing internal standards. After vortexing every 30 min (6 cycles, 30 sec each), extracts were centrifuged (12, 000 rpm, 3 min), filtered through 0.22-μm membranes, and stored at -80°C. Chromatographic separation used an Agilent SB-C18 column (1.8 μm, 2.1×100 mm) with mobile phase A (0.1% formic acid/water) and B (0.1% formic acid/acetonitrile) at 0.35 mL/min (40°C). The gradient program was: 0-9 min (95%→5% A), 9-10 min (5% A), 10-11.1 min (5%→95% A), 11.1-14 min (95% A). MS detection employed an ExionLC™ AD/UPLC-ESI-QTRAP system with ion spray voltage ±5500/4500 V, source temperature 550°C, gas pressures (GSI:50 psi, GSII:60 psi, CUR:25 psi), and collision-activated dissociation in high mode. Metabolites were quantified via MRM with nitrogen collision gas, optimized declustering potential (DP), and collision energy (CE).

4.9. Identification of Gene Families Involved in Isofraxidin Biosynthesis

In the identification of gene families involved in the biosynthesis of isofraxidin pathway enzymes a comprehensive approach was adopted. For genes encoding P450 enzymes including CYP71, CYP73, and CYP74 sequences from

Arabidopsis (

https://www.arabidopsis.org) were used as references for genome-wide screening followed by sequence alignment using MAFFT and phylogenetic reconstruction with IQ-TREE v.1.6.9 applying the Approximate-Maximum-Likelihood method to identify candidate sequences clustering with AtCYP71, AtCYP73, and AtCYP74. In parallel for PAL (PF00221), COSY (PF02458), CCoAOMT (PF01596), and OMT (PF00891) initial candidate sequences were identified through HMMER v3.0 [

61] searches against Pfam domains with an E-value cutoff of 1e-15 and further validated using BLASTp against specific

Arabidopsis protein sequences AAC18870.1, AT1G28680, AAM66108.1 and AT5G54160 respectively also with an E-value threshold of 1e-15. The final list of candidate genes for each family was established by intersecting results obtained from both HMMER and BLASTp searches.

4.10. Integrated Transcriptome-Metabolome Analysis

The quantitative values of both genes and metabolites across all samples were normalized using the Z-score method. Pearson correlation coefficients between gene expression and metabolite levels were calculated using the core function in R. Correlations with an absolute Pearson correlation coefficient greater than 0.8 and a p-value less than 0.05 were considered significant and selected for further analysis.

5. Conclusions

As an early-diverging angiosperm lineage, Chloranthus provides an exceptional model for investigating isofraxidin biosynthesis, offering critical insights into the adaptive evolution of chemical defenses in basal flowering plants. Through integrated multi-omics analysis complemented by enzymatic verification, we have elucidated the core regulatory framework governing representative hydroxycoumarin biosynthesis in C. erectus. Principal mechanisms were identified: (1) Functional divergence within the expanded COSY gene family facilitates tissue-specific accumulation of key precursors through substrate specialization, establishing a dynamic metabolic reservoir for downstream isofraxidin production. (2) CYP71 subfamily members demonstrate spatiotemporal differentiation, with stamen-enriched CYP71_12/13/15 (r > 0.87) serving as critical nodes for fraxetin biosynthesis via compartmentalized expression patterns. (3) The final modifications is achieved through rhizome-preferential OMT isoforms (OMT_5/6/7, r > 0.83), enabling accumulation patterns of terminal derivatives.

This work establishes a mechanistic paradigm for coumarin pathway evolution. By bridging genomic innovation with ecological adaptation, these findings provide advances in understanding early angiosperm chemical evolution and developing biotechnological applications for natural product biosynthesis.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Supplementary Figures; Supplementary Tables.

Author Contributions

Lingjian Gui led and conceived the genome sequencing; Yingying Liu and Ming Lei manage the project; Cuihong Yang, Wenjing Liang, Zhigang Yan and Shugen Wei collect materials for genome and transcriptome sequencing; Lisha Song, Lingyun Wan, Lingjian Gui and Jing Wang analyzed the data. Lingjian Gui and Yingying Liu wrote the manuscript. Jing Wang, Ming Lei contributed to the discussion and improvement of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final paper.

Funding

This work was supported by the Guangxi Science & Technology Programme (No. AD1850002); Independent Research Project of Guangxi Medicinal Plant Conservation Talent Center (GXYYXGD202202); Guangxi Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine (GXZYA20230015).

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Kong, H.Z. Karyotypes of Sarcandra Gardn. and Chloranthus Swartz (Chloranthaceae) from China. Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society 2000, 133, 327–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, N.F.; Ge, D.; Laing, J.F. Barremian earliest angiosperm pollen. Palaeontology 1979, 22, 513–535. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, N.F. The enigma of angiosperm origins; Cambridge University Press: 1994; Volume 1.

- Taylor, D.W.; Hickey, L.J. Phylogenetic evidence for the herbaceous origin of angiosperms. Plant Systematics and Evolution 1992, 180, 137–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doyle, J.A.; Endress, P.K. Integrating Early Cretaceous fossils into the phylogeny of living angiosperms: ANITA lines and relatives of Chloranthaceae. International Journal of Plant Sciences 2014, 175, 555–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Fang, D.; Sahu, S.K.; Yang, S.; Guang, X.; Folk, R.; Smith, S.A.; Chanderbali, A.S.; Chen, S.; Liu, M.; et al. Chloranthus genome provides insights into the early diversification of angiosperms. Nature communications 2021, 12, 6930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; Liu, D.; Fan, G.; Wang, R.; Lu, X.; Gu, Y.; Shi, Q. Constituents from Chloranthaceae plants and their biological activities. Heterocyclic Communications 2016, 22, 175–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.C.; Li, Z.; Zhao, Y.X.; Gao, M.; Wang, J.Y.; Liu, K.W.; Wang, X.; Wu, L.W.; Jiao, Y.L.; Xu, Z.L. The Litsea genome and the evolution of the laurel family. Nature communications 2020, 11, 1675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robe, K.; Izquierdo, E.; Vignols, F.; Rouached, H.; Dubos, C. The coumarins: secondary metabolites playing a primary role in plant nutrition and health. Trends in Plant Science 2021, 26, 248–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharifi-Rad, J.; Cruz-Martins, N.; López-Jornet, P.; Lopez, E.P.-F.; Harun, N.; Yeskaliyeva, B.; Beyatli, A.; Sytar, O.; Shaheen, S.; Sharopov, F. Natural coumarins: exploring the pharmacological complexity and underlying molecular mechanisms. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity 2021, 2021, 6492346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durmaz, L.; Gulçin, İ.; Taslimi, P.; Tüzün, B. Isofraxidin: Antioxidant, Anti-carbonic Anhydrase, Anti-cholinesterase, Anti-diabetic, and in Silico Properties. ChemistrySelect 2023, 8, e202300170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.; Zhang, T.; Wang, Y.; Yuan, W.; Li, L.; Li, J.; Yang, Y.; Wu, D.; Xu, Y. Isofraxidin attenuates dextran sulfate sodium-induced ulcerative colitis through inhibiting pyroptosis by upregulating Nrf2 and reducing reactive oxidative species. International Immunopharmacology 2024, 128, 111570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manni, M.; Berkeley, M.R.; Seppey, M.; Simão, F.A.; Zdobnov, E.M. BUSCO update: novel and streamlined workflows along with broader and deeper phylogenetic coverage for scoring of eukaryotic, prokaryotic, and viral genomes. Molecular Biology and Evolution 2021, 38, 4647–4654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Yu, S.; Cheng, Z.; Chang, X.; Yun, Y.; Jiang, M.; Chen, X.; Wen, X.; Li, H.; Zhu, W. Origin and evolution of the triploid cultivated banana genome. Nature genetics 2024, 56, 136–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wendel, J.F.; Jackson, S.A.; Meyers, B.C.; Wing, R.A. Evolution of plant genome architecture. Genome Biology 2016, 17, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Wang, X.; Wang, G.; Cui, P.; Wu, S.; Ai, C.; Hu, N.; Li, A.; He, B.; Shao, X.; et al. The nearly complete genome of Ginkgo biloba illuminates gymnosperm evolution. Nature Plants 2021, 7, 748–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niu, S.; Li, J.; Bo, W.; Yang, W.; Zuccolo, A.; Giacomello, S.; Chen, X.; Han, F.; Yang, J.; Song, Y.; et al. The Chinese pine genome and methylome unveil key features of conifer evolution. Cell 2022, 185, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albert, V.A.; Barbazuk, W.B.; Depamphilis, C.W.; Der, J.P.; Leebens-Mack, J.; Ma, H.; Palmer, J.D.; Rounsley, S.; Sankoff, D.; Schuster, S.C. The Amborella genome and the evolution of flowering plants. Science 2013, 342, 1241089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, L.; Xu, Z.; Wang, M.; Fan, R.; Yuan, D.; Wu, B.; Wu, H.; Qin, X.; Yan, L.; Tan, L.; et al. The chromosome-scale reference genome of black pepper provides insight into piperine biosynthesis. Nature communications 2019, 10, 4702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaw, S.M.; Liu, Y.C.; Wu, Y.W.; Wang, H.Y.; Lin, C.Y.I.; Wu, C.S.; Ke, H.M.; Chang, L.Y.; Hsu, C.Y.; Yang, H.T. Stout camphor tree genome fills gaps in understanding of flowering plant genome evolution. Nature plants 2019, 5, 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Fan, Z.; Wei, W.; Yang, C.; Wang, Y.; Shen, X.; Yan, X.; Zhou, Z. Biosynthesis of the plant coumarin osthole by engineered Saccharomyces cerevisiae. ACS Synthetic Biology 2023, 12, 2455–2462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Tang, H.; Wei, X.; He, Y.; Hu, S.; Wu, J.; Xu, D.; Qiao, F.; Xue, J.; Zhao, Y. The gradual establishment of complex coumarin biosynthetic pathway in Apiaceae. Nature Communications 2024, 15, 6864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.-y.; Li, Y.-z.; Huang, S.-q.; Zhang, H.-w.; Deng, C.; Song, X.-m.; Zhang, D.-d.; Wang, W. Genus Chloranthus: A comprehensive review of its phytochemistry, pharmacology, and uses. Arabian Journal of Chemistry 2022, 15, 104260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leng, L.; Xu, Z.; Hong, B.; Zhao, B.; Tian, Y.; Wang, C.; Yang, L.; Zou, Z.; Li, L.; Liu, K. Cepharanthine analogs mining and genomes of Stephania accelerate anti-coronavirus drug discovery. Nature Communications 2024, 15, 1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ouadi, S.; Sierro, N.; Goepfert, S.; Bovet, L.; Glauser, G.; Vallat, A.; Peitsch, M.C.; Kessler, F.; Ivanov, N.V. The clove (Syzygium aromaticum) genome provides insights into the eugenol biosynthesis pathway. Communications biology 2022, 5, 684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, Z.; Song, L.; Chen, M.; Liu, Z.; Yuan, Z.; Wen, H.; Zhang, H.; Huang, Y.; Peng, Z.; Yang, H. Neofunctionalization of an OMT cluster dominates polymethoxyflavone biosynthesis associated with the domestication of citrus. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2024, 121, e2321615121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carocha, V.; Soler, M.; Hefer, C.; Cassan-Wang, H.; Fevereiro, P.; Myburg, A.A.; Paiva, J.A.; Grima-Pettenati, J. Genome-wide analysis of the lignin toolbox of E ucalyptus grandis. New Phytologist 2015, 206, 1297–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marçais, G.; Kingsford, C. A fast, lock-free approach for efficient parallel counting of occurrences of k-mers. Bioinformatics 2011, 27, 764–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.; Concepcion, G.T.; Feng, X.W.; Zhang, H.W.; Li, H. Haplotype-resolved de novo assembly using phased assembly graphs with hifiasm. Nature Methods 2021, 18, 170–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Durbin, R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 1754–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parra, G.; Bradnam, K.; Korf, I. CEGMA: a pipeline to accurately annotate core genes in eukaryotic genomes. Bioinformatics 2007, 23, 1061–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simão, F.A.; Waterhouse, R.M.; Ioannidis, P.; Kriventseva, E.V.; Zdobnov, E.M. BUSCO: assessing genome assembly and annotation completeness with single-copy orthologs. Bioinformatics 2015, 31, 3210–3212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, S.; Zhao, Q.; Ming, R.; Tang, H. Assembly of allele-aware, chromosomal-scale autopolyploid genomes based on Hi-C data. Nature plants 2019, 5, 833–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durand, N.C.; Shamim, M.S.; Machol, I.; Rao, S.S.; Huntley, M.H.; Lander, E.S.; Aiden, E.L. Juicer provides a one-click system for analyzing loop-resolution Hi-C experiments. Cell systems 2016, 3, 95–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, N.S. Using Repeat Masker to identify repetitive elements in genomic sequences. Current Protocols in Bioinformatics 2004, 5, 4–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flynn, J.M.; Hubley, R.; Goubert, C.; Rosen, J.; Clark, A.G.; Feschotte, C.; Smit, A.F. RepeatModeler2 for automated genomic discovery of transposable element families. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2020, 117, 9451–9457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Price, A.L.; Jones, N.C.; Pevzner, P.A. De novo identification of repeat families in large genomes. Bioinformatics 2005, 21, i351–i358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edgar, R.C.; Myers, E.W. PILER: identification and classification of genomic repeats. Bioinformatics 2005, 21, i152–i158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Wang, H. LTR_FINDER: an efficient tool for the prediction of full-length LTR retrotransposons. Nucleic acids research 2007, 35, W265–W268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanke, M.; Schöffmann, O.; Morgenstern, B.; Waack, S. Gene prediction in eukaryotes with a generalized hidden Markov model that uses hints from external sources. BMC Bioinformatics 2006, 7, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Zhu, H.; Ruan, J.; Qian, W.; Fang, X.; Shi, Z.; Li, Y.; Li, S.; Shan, G.; Kristiansen, K. De novo assembly of human genomes with massively parallel short read sequencing. Genome Research 2010, 20, 265–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parra, G.; Blanco, E.; Guigó, R. Geneid in drosophila. Genome Research 2000, 10, 511–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Majoros, W.H.; Pertea, M.; Salzberg, S.L. TigrScan and GlimmerHMM: two open source ab initio eukaryotic gene-finders. Bioinformatics 2004, 20, 2878–2879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korf, I. Gene finding in novel genomes. BMC Bioinformatics 2004, 5, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Birney, E.; Durbin, R. Using GeneWise in the Drosophila annotation experiment. Genome Research 2000, 10, 547–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trapnell, C.; Williams, B.A.; Pertea, G.; Mortazavi, A.; Kwan, G.; Van Baren, M.J.; Salzberg, S.L.; Wold, B.J.; Pachter, L. Transcript assembly and quantification by RNA-Seq reveals unannotated transcripts and isoform switching during cell differentiation. Nature Biotechnology 2010, 28, 511–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haas, B.J.; Delcher, A.L.; Mount, S.M.; Wortman, J.R.; Smith Jr, R.K.; Hannick, L.I.; Maiti, R.; Ronning, C.M.; Rusch, D.B.; Town, C.D. Improving the Arabidopsis genome annotation using maximal transcript alignment assemblies. Nucleic acids research 2003, 31, 5654–5666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haas, B.J.; Salzberg, S.L.; Zhu, W.; Pertea, M.; Allen, J.E.; Orvis, J.; White, O.; Buell, C.R.; Wortman, J.R. Automated eukaryotic gene structure annotation using EVidenceModeler and the Program to Assemble Spliced Alignments. Genome biology 2008, 9, R7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Stoeckert, C.J.; Roos, D.S. OrthoMCL: identification of ortholog groups for eukaryotic genomes. Genome research 2003, 13, 2178–2189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, M.V.; Thomas, G.W.; Lugo-Martinez, J.; Hahn, M.W. Estimating gene gain and loss rates in the presence of error in genome assembly and annotation using CAFE 3. Molecular biology and evolution 2013, 30, 1987–1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosentino, S.; Iwasaki, W. SonicParanoid: fast, accurate and easy orthology inference. Bioinformatics 2019, 35, 149–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edgar, R.C. MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic acids research 2004, 32, 1792–1797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalyaanamoorthy, S.; Minh, B.Q.; Wong, T.K.F.; Von Haeseler, A.; Jermiin, L.S. ModelFinder: fast model selection for accurate phylogenetic estimates. Nature methods 2017, 14, 587–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stamatakis, A. RAxML version 8: a tool for phylogenetic analysis and post-analysis of large phylogenies. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 1312–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, L.-T.; Schmidt, H.A.; Von Haeseler, A.; Minh, B.Q. IQ-TREE: a fast and effective stochastic algorithm for estimating maximum-likelihood phylogenies. Molecular biology and evolution 2015, 32, 268–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirarab, S.; Reaz, R.; Bayzid, M.S.; Zimmermann, T.; Swenson, M.S.; Warnow, T. ASTRAL: genome-scale coalescent-based species tree estimation. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, i541–i548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, M.d.; Yang, Z. Approximate likelihood calculation on a phylogeny for Bayesian estimation of divergence times. Molecular biology and evolution 2011, 28, 2161–2172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z. PAML 4: phylogenetic analysis by maximum likelihood. Molecular biology and evolution 2007, 24, 1586–1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Hao, Z.; Guang, X.; Zhao, C.; Wang, P.; Xue, L.; Zhu, Q.; Yang, L.; Sheng, Y.; Zhou, Y. Liriodendron genome sheds light on angiosperm phylogeny and species–pair differentiation. Nature plants 2019, 5, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Tang, H.; DeBarry, J.D.; Tan, X.; Li, J.; Wang, X.; Lee, T.-h.; Jin, H.; Marler, B.; Guo, H. MCScanX: a toolkit for detection and evolutionary analysis of gene synteny and collinearity. Nucleic acids research 2012, 40, e49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potter, S.C.; Luciani, A.; Eddy, S.R.; Park, Y.; Lopez, R.; Finn, R.D. HMMER web server: 2018 update. Nucleic acids research 2018, 46, W200–W204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).