1. Introduction

Behcet’s syndrome (BS) is a chronic, multisystem, inflammatory condition with relapsing and remitting course. Recurrent oral and genital ulceration, the hallmark of BS, are the most common clinical manifestations, but other organs can be involved including, but not limited to, eyes, gastrointestinal tract, central nervous system and vascular tree. BS is particularly prevalent along the ancient “Silk Road,” especially in Turkey, the Middle East, and Southeast Asia. The etiology of the BS remains to be elucidated but it is believed to involve complex interplay between genetic predisposition (e.g., HLA-B51), environmental triggers, and abnormal immune responses, [

1].

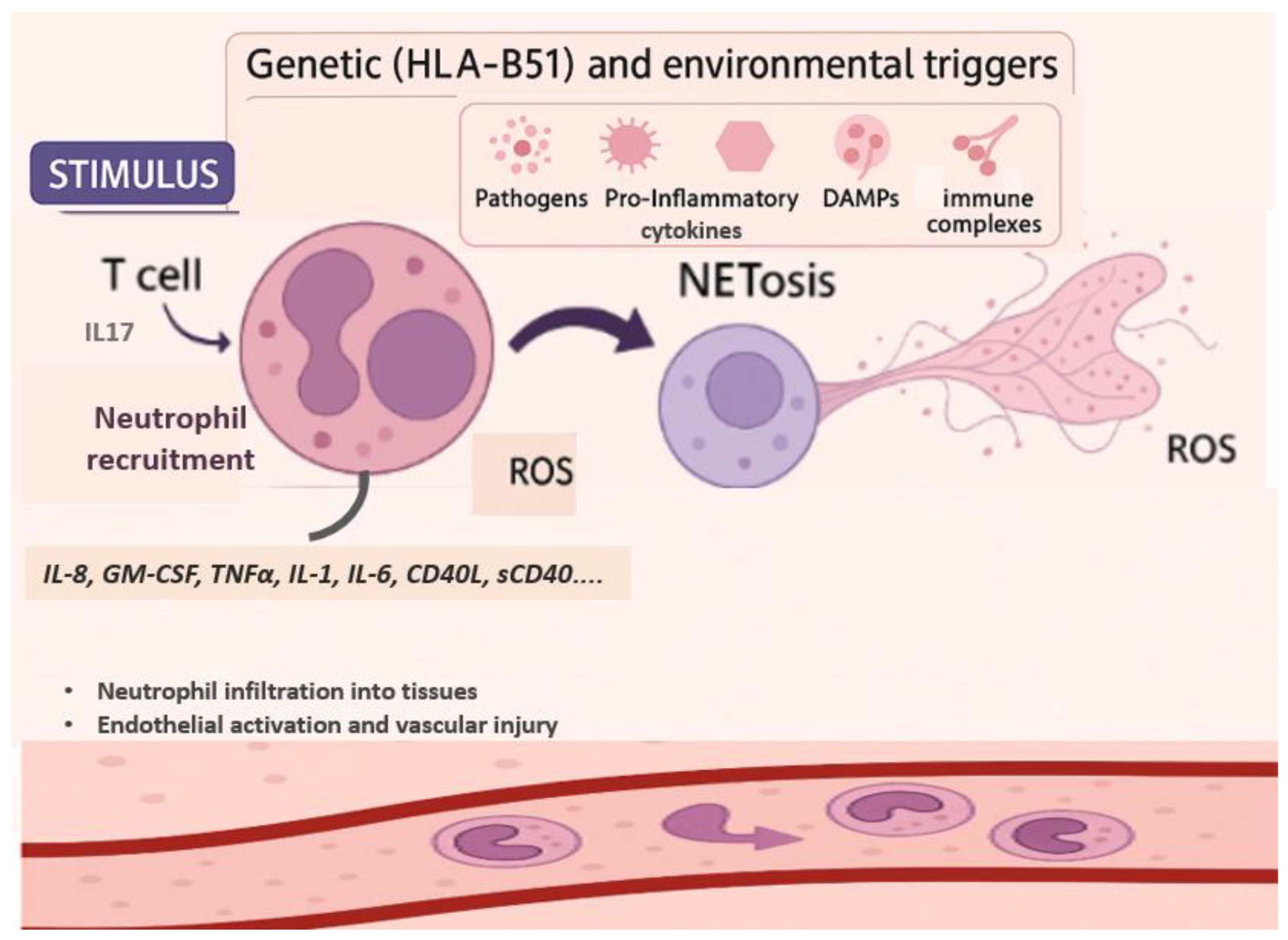

Neutrophils play central role in the pathogenesis of BS as suggested by several observations including the activation of Th17 cells and endothelium, the secretion of neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) and reactive oxygen species (ROS) and the presence of neutrophils in several typical lesions of BS, such oral ulcers, pathergy and the GI tract [

2,

3].

Currently, no single, specific marker can reliably assess disease activity. Therefore, assessment of disease activity is based mainly on recent medical history as exemplified in the Behçet’s Disease Current Activity Form (BDCAF) or the Physician Global Assessment, alongside non-specific inflammatory markers like C-reactive protein (CRP) and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) [

4]. In parallel, growing attention has been directed toward simple and accessible inflammatory markers derived from routine blood tests. Among these, the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR), calculated by dividing the neutrophil count by the lymphocyte count, has gained interest as a reflection of the balance between the innate (neutrophils) and adaptive (lymphocytes) immune responses [

5]. Cumulative evidence supports the use of NLR as cost effective and simple disease activity marker for endothelial activation and inflammation in many diseases including BS. NLR has been studied in wide range of clinical conditions, including ischemic stroke, cerebral hemorrhage, cardiovascular events, sepsis, infectious diseases, and cancer and has been found to be associated with increased disease burden and poor clinical outcomes [

6,

7]. In recent years, growing attention has been directed toward the utility of NLR in autoimmune diseases. Elevated NLR values have been reported in psoriasis, ulcerative colitis, rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, primary Sjögren’s syndrome, Takayasu’s arteritis, and BS, suggesting its potential use as a surrogate marker for systemic inflammation and disease activity [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12]. There is a growing interest in NLR as potential inflammatory biomarker in BS, mainly due the central role of neutrophils in the pathogenesis of BS. Several studies have explored its utility, suggesting possible correlation between elevated NLR values and active disease. The first study that examined the role of NLR in BS was reported by Rifaioglu et al. in 2014. They demonstrated that NLR levels were higher in patients with active BS compared to both, healthy controls and patients with inactive disease [

13]. In more recent large-scale retrospective study, Mentesoğlu et al. (2024) analyzed 513 BS patients and found that mean NLR values were significantly higher among patients with active disease compared to those with inactive disease (3.50 vs. 1.88;

p < 0.001). Elevated NLR levels were also associated with various clinical presentations, including mucocutaneous, vascular, neurological, and articular involvement, [

14].

Studies to date have investigated the performance of NLR in a variety of clinical contexts in BS, including its correlation with overall disease activity, specific organ involvement, and its potential role in predicting disease course or treatment response.

This review aims to comprehensively review the current literature regarding the role of NLR in BS, including its correlation with acceptable and validated indices of disease activity, its performance as a measure of global disease activity and specific organ activity, and its performance as a predictor of treatment response and future complications.

2. Role of Neutrophils in Behçet’s Syndrome

Neutrophils, as key components of the innate immune system, have long been implicated in the pathogenesis of BS, with early studies in the 1970s demonstrating enhanced chemotactic activity in neutrophils from BS patients. Histopathological examinations of various tissues, including mucosal, aortic, intestinal, conjunctival, and cutaneous lesions, have shown prominent neutrophilic infiltration, particularly around the vasa vasorum. These neutrophils express pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1α, TNF-α, and IFN-γ, and show increased adhesion to HLA-DR–positive endothelial cells. Similar patterns of infiltration have been documented in neurological involvement (neuro-Behçet’s) and in erythema nodosum-like lesion [

2].

The mechanisms driving increased neutrophil activity in BS are multifactorial and may involve soluble mediators, microbial products, and direct cellular interactions. Upregulation of adhesion molecules on both neutrophils and endothelial cells is thought to facilitate recruitment and transmigration, [

2].

Supporting these histological and pathophysiological findings, flow cytometry studies have demonstrated upregulation of activation markers such as CD64, CD11a, CD11b, CD18, CD206, CD209, and CD66b on neutrophils from BS patients, indicating a hyperactivated neutrophil profile. In parallel, increased levels of neutrophil granule enzymes—including neutrophil elastase (NE), myeloperoxidase (MPO), and S100A proteins—have been reported in saliva and serum, reflecting systemic neutrophil activation in BS [

2]. Additionally, sera from BS patients have been shown to enhance the adhesion of healthy neutrophils to human endothelial cells, alongside elevated levels of CXCL-8, a potent neutrophil chemoattractant [

15].

In recent years, increasing attention has been given to the role of NETs in the pathogenesis of BS. Neutrophils, as central components of the innate immune system, contribute to disease mechanisms through multiple effector functions, including phagocytosis, degranulation, and NETs formation. NETs are web-like structures composed of chromatin fibers decorated with histones and neutrophil-derived enzymes, released through a distinct form of cell death known as NETosis, [

16]. Beyond their antimicrobial function, NETs have been implicated in the pathogenesis of several autoinflammatory and autoimmune diseases, including systemic vasculitides. In BS, they are increasingly recognized as key contributors to endothelial damage and to thrombus initiation and propagation in both venous and arterial systems, such as deep vein thrombosis, stroke, and myocardial infarction, [

2].

NETosis can be triggered by a variety of stimuli, including pathogens, proinflammatory cytokines, pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs), damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) and immune complexes [

16].

One of the major molecular pathways leading to NETosis is the generation ROS. ROS are the products of biological reduction reactions. Uncontrolled free radicals in a living organism cause disease and cell damage [

17]. NETosis is mediated by NADPH oxidase, results in the formation of superoxide anions (O₂⁻) and hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂), which are further processed by MPO into highly reactive secondary oxidants. While ROS are crucial for pathogen clearance, under certain circumstances such as during autoimmune response, neutrophils can be triggered to release ROS and proteases extracellularly causing damage to host tissues, modification of host proteins, lipids and DNA and dysregulation of oxidative homeostasis. Studies have consistently shown elevated ROS levels and reduced antioxidant defenses in both the plasma and neutrophils of BS patients. Moreover, excessive ROS may contribute to fibrinogen oxidation, resulting in delayed fibrin polymerization and resistance to fibrinolysis—mechanisms that may underlie the thrombus formation process frequently observed in BS [

18]. Supporting these findings, Becatti et al. demonstrated that neutrophils from patients with BS exhibit significantly elevated ROS production. This enhanced oxidative stress leads to fibrinogen carbonylation and alterations in its secondary structure, resulting in impaired clot formation and decreased susceptibility of fibrin to plasmin-induced lysis. These suggested mechanisms may further contribute to thrombus formation in patients with BS [

19]. ROS generation, together with calcium mobilization, triggers a cascade of intracellular events that culminates in NETosis. These include nuclear delobulation, enzymatic activation of MPO and NE, and chromatin modification via histone citrullination by peptidyl arginine deiminase 4 [

2]. Le Joncour et al. analyzed NET components in blood samples from patients with BS including circulating cell-free DNA (cfDNA) and MPO-DNA complexes. They showed that patients with active disease had significantly elevated levels of cfDNA and MPO-DNA compared to those with inactive disease and healthy donors. Notably, these levels were even higher in patients with vascular involvement. Furthermore, purified neutrophils from BS patients exhibited spontaneous NETosis, in contrast to healthy controls. These findings support the hypothesis that enhanced NET formation contributes to the thrombotic and vasculopathic features of BS [

20].

Accumulating evidence suggests that IL-17-producing Th17 cells play important role in the pathogenesis of BS. These cells contribute to inflammation not only by secreting proinflammatory cytokines, but also by promoting neutrophil recruitment via the granulocyte colony-stimulating factor pathway [

3]. Patients with active BS exhibit increased proportion of circulating Th17 cells and enhanced IL-17 production by peripheral blood mononuclear cells. IL-21, a promoter of Th17 responses, has been shown to contribute to the expansion of Th17 cells in the peripheral blood of patients with BS, while concurrently reducing the number of FoxP3-expressing regulatory T cells (Tregs). Interestingly, inhibition of IL-21 was found to restore the balance between Th17 and Treg populations, highlighting its role in the immune dysregulation characteristic of BS. Altogether, the interplay between Th17 cells and neutrophils may sustain self-amplifying inflammatory loop that bridges innate and adaptive immunity in BS [

3].

From therapeutic perspective, several agents used in the management of BS have been shown to attenuate neutrophil activation and reduce the formation of NETs. Colchicine, as demonstrated in the study by Korkmaz et al., modulates neutrophil activity by lowering intracellular calcium concentrations (Ca²⁺), a key trigger of ROS production. By suppressing Ca²⁺ influx, colchicine reduces oxidative stress and limits neutrophil-mediated tissue damage in BS [

17]. Similarly, glucocorticoids, anti-TNFα therapies, and apremilast have also been reported to inhibit neutrophil activation and NETs release [

2].

Figure 1 describes the potential role of neutrophils in BS, highlighting their activation by various cytokines including IL-17, production of ROS, NETosis, and infiltration into affected tissues.

3. Physiological Background of NLR and Normal Limits

NLR reflects the balance between innate and adaptive immune responses and serves as reliable indicator of both, inflammation and stress. The reciprocal changes in neutrophil and lymphocyte counts represent a complex, multifactorial process influenced by regulation of various immunologic, neuroendocrine, humoral, and biological mechanisms [

5]. Although the separate role of neutrophil and lymphocyte counts in the clinical severity of systemic inflammatory response has been previously examined, the concept of NLR was initially proposed by Zahorec in 2001 as simple marker of systemic inflammatory response and physiological stress in critically ill patients, particularly for assessing the severity of sepsis and systemic infections, including bacteremia [

21]. This parameter, which is formulated by the ratio of two simple complete blood count parameters, has been found to provide better performance in the prognosis of many critical conditions than its components [

22].

An increase in NLR is determined by an increase of neutrophils and/or reduction in lymphocytes. Elevated neutrophil counts and the corresponding rise in the NLR are common findings in a variety of clinical settings associated with acute or chronic inflammation. These include bacterial and fungal infectious diseases, acute cerebrovascular events, myocardial infarction, atherosclerotic processes, malignancies, major trauma, and complications following surgery. Such elevations often reflect the early proinflammatory phase of systemic responses, where neutrophils play a central role, [

23]. In the context of systemic inflammatory response syndrome, inhibition of neutrophils’ apoptosis further amplifies their activity, contributing to increased NLR, typically characterized by both neutrophilia and relative lymphopenia [

23]. On the other hand, lymphocytes play central role in the adaptive immune system, enabling targeted elimination of pathogens, infected cells, and even malignant or premalignant cells. A reduction in circulating lymphocyte counts can be observed following acute infections, the use of immunosuppressive or cytotoxic therapies (e.g., chemotherapy), and in various immune-mediated diseases such as systemic lupus erythematosus [

6]. The mechanisms responsible for lymphopenia also involve margination and redistribution of lymphocytes within the lymphatic system, along with accelerated apoptosis through tumor-related cytokines, particularly interleukin [IL-10] and tumor necrosis factor beta [

22].

Beyond its diagnostic implications, NLR has also been associated with prognostic value in the general population. Higher NLR levels were linked to increased overall mortality and specific mortality risks, including cardiovascular diseases, chronic respiratory conditions, infections such as pneumonia and influenza, and renal disorders, with hazard ratios rising progressively across NLR quartiles [

6,

23]. Notably, NLR association with overall mortality appeared strongest in the immediate 1-year period after the baseline blood measurement [

6].

NLR values can be influenced by various physiological and demographic factors, including age, sex, smoking status, obesity, diabetes mellitus, and ethnicity, and lower values have been reported among African American individuals [

5,

24].

Several epidemiological studies have evaluated normal NLR values in healthy populations, showing variability by ethnicity and geography. However, the average NLR is generally around 1.65, with commonly accepted normal values ranging between 1.2 and 2.15 [

5,

22]. Although earlier studies proposed broader upper limits of up to 5, distinct cutoff values have been reported for different diseases (e.g., malignancy, sepsis, and cardiovascular diseases), and there remains lack of consensus as to the unified pathological value in this regard [

22]. Values higher than 3 and below 0.7 in adults are pathological. The NLR between 2 and 3 is considered as grey zone corresponding to latent, subclinical or low-grade inflammation [

5]. Several population-based studies have examined these variations. Azab et al. reported mean NLR of 2.15 in large US cohort, while Lee et al. found lower average of 1.65 in Korean population [

24,

25]. Overall, higher NLR values are generally associated with more severe inflammation and physiological stress [

5].

4. NLR in Behçet’s Syndrome

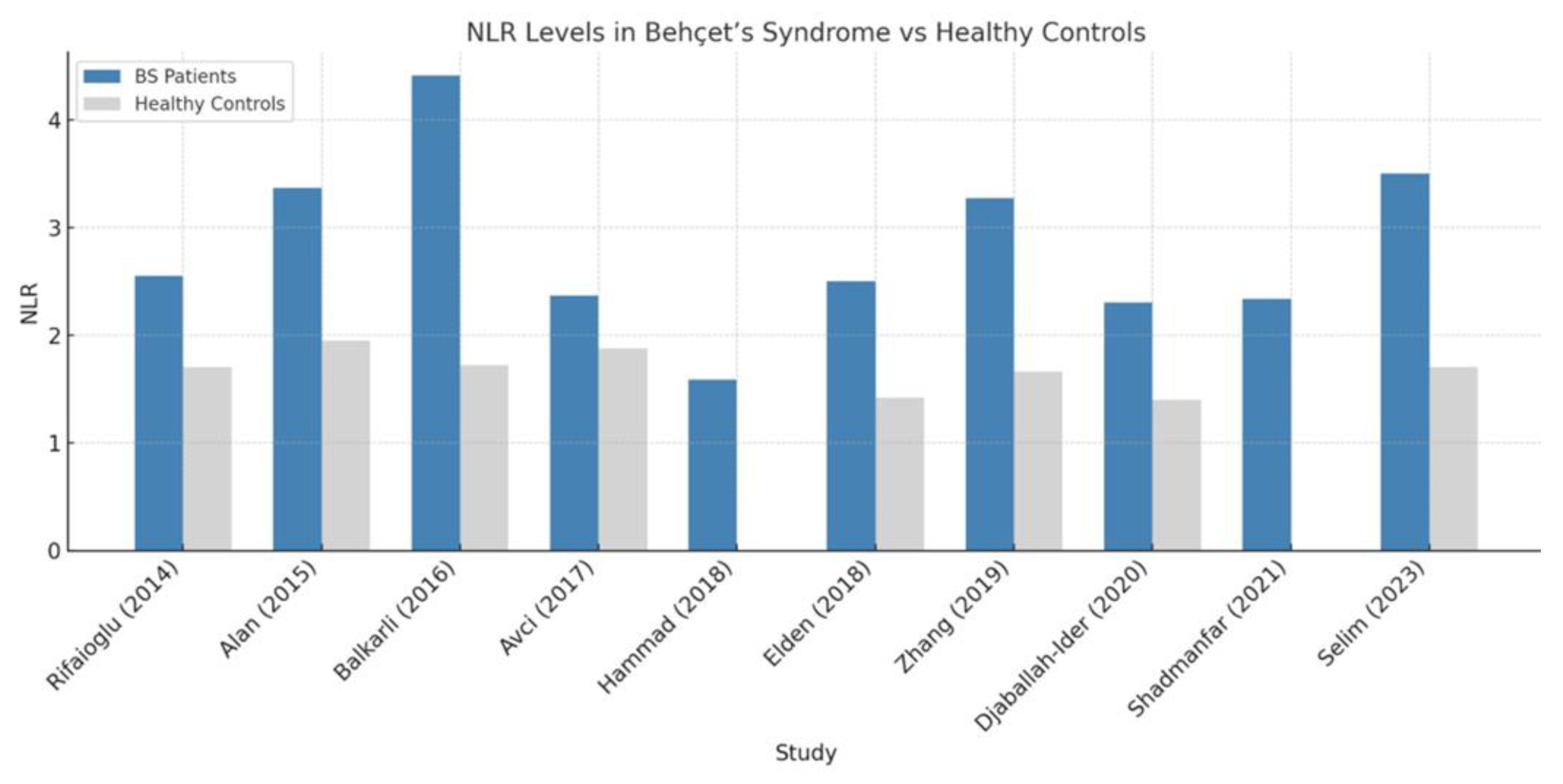

Cumulative evidence supports the role of the NLR as a simple, accessible, and cost-effective biomarker for systemic inflammation in BS. Numerous studies have investigated its association with disease activity and clinical manifestations. The first study to investigate NLR in BS was reported by Rifaioglu et al. in 2014. In this retrospective analysis of 65 BS patients and 100 healthy controls, the authors demonstrated that NLR values were significantly higher in BS patients compared to controls, and markedly elevated in patients with active disease. Importantly, NLR correlated positively with CRP and white blood cell counts. These findings supported the notion that NLR reflects disease activity in BS and may serve as low-cost, readily accessible inflammatory marker [

13]. More recently, Mentesoglu et al. analyzed a large retrospective cohort of 513 adult BS patients to explore the association between inflammatory indices—including NLR—and disease activity. Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve analysis revealed an optimal NLR cutoff value of 2.11, yielding 67.3% sensitivity and 68.4% specificity for identifying active disease (AUC = 0.750). The mean NLR was significantly higher in active patients compared to those with inactive disease (3.50 vs. 1.88;

p < 0.001) [

14]. Similarly, a case-control study by Selim et al. that included 36 BS patients and 36 healthy controls, demonstrated significantly elevated levels of both NLR and platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio (PLR) in BS patients (

p = 0.008 and 0.011, respectively). The median NLR in the BS group was 3.5 (0.4–9.6), compared to 1.7 (0.8–9.8) in the control group (

p = 0.008). Supporting these findings, a 2024 meta-analysis by Young et al. reported significantly higher NLR values in BS patients compared to healthy controls, with standardized mean difference of 1.312 (95% CI: 0.713–1.911;

p < 0.001), indicating large effect size. Alan et al. also confirmed these observations, demonstrating elevated NLR values in BS patients relative to healthy individuals [

26].

In the context of active BS, NLR has emerged as potential marker of inflammatory activity. Selim et al. [

27] reported that NLR levels were significantly higher in active BS patients compared to those with inactive disease (median NLR: 3.8 [1.0–5.4] vs. 1.8 [0.4–9.6];

P = 0.009). Additional inflammatory markers—including PLR, lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio (LMR), ESR, and CRP—also differed significantly between active and inactive groups (

P < 0.05), with active patients showing elevated NLR, PLR, ESR, and CRP, and reduced LMR. These findings are supported by Balkarli et al., who similarly observed increased NLR in active BS relative to inactive disease and healthy controls. Rifaioglu et al. [

28], Hammad et al. [

29], Djaballah-Ider et al. [

30], and Shadmanfar et al. [

31] have all reinforced this association, collectively underscoring the utility of NLR as a surrogate marker for disease activity in BS.

Several of these studies also demonstrated associations between elevated NLR and specific clinical manifestations, including mucocutaneous and articular involvement [

14,

27,

29,

30], gastrointestinal manifestations [

29], vascular involvement [

14,

30], neurologic symptoms [

14,

27], and ocular involvement [

27,

31].

Supporting the ocular relevance of NLR, a hospital-based study by Avci et al. involving 912 BS patients showed that NLR, along with PLR and mean platelet volume (MPV), were all significantly elevated in patients with anterior uveitis compared to BS patients without ocular involvement and healthy controls. Among the three parameters, NLR demonstrated the strongest diagnostic performance, suggesting its utility in identifying anterior uveal inflammation in BS [

32]. In terms of clinical indices, Hammad et al. found that NLR correlated more strongly with BS activity scores than other hematologic indices such as PLR [

29]. This observation was echoed by Elden et al. (2018), who demonstrated an association between elevated NLR and increased carotid intima-media thickness [

33].

Djaballah-Ider et al. further showed that NLR is treatment-responsive: in active BS patients it

declined after 15 days of combined colchicine and corticosteroid therapy (P < 0.0001). They also reported that NLR values were highest in naïve-active patients with mucocutaneous or angio-Behçet manifestations, exceeding those seen in ocular or articular disease [

30]. Lee et al. conducted a meta-analysis including 24 studies and concluded that NLR is elevated in BS, particularly during active disease phases. They reinforced its role as reliable and reproducible marker for disease monitoring [

34]. Zhang et al. proposed combining NLR with hemoglobin levels to enhance diagnostic accuracy [

35].

Taken together, these findings underscore NLR’s clinical utility in BS as a biomarker reflecting systemic inflammation, disease activity, and specific organ involvement. Its consistency across multiple studies and populations supports its use in clinical practice and research settings. Even though, it should be emphasized that NLR has not been adapted by clinicians in daily practice when treating patients with BS. This is likely due to lack of specificity, as well as the lack of standardized cutoff values, insufficient prospective validation, and the absence of clear clinical consensus regarding its implementation.

Table 1 summarizes the key studies evaluating the NLR in patients with BS.

Figure 2 provides visual comparison of NLR values reported in BS patients versus healthy controls across selected studies, highlighting the wide variations across different studies.

5. Additional Neutrophil-Related Indices in Behçet’s Syndrome

Another index derived from NLR is the Systemic Immune-Inflammation Index (SII), introduced in 2014, calculated as (platelets × neutrophils) / lymphocytes. By incorporating platelet count, SII offers broader reflection of systemic inflammation and has shown prognostic value in cancers, cardiovascular diseases, and infections. In BS, [

22]. Tanacan et al. [

36] found elevated SII and absolute neutrophil count (ANC) in patients with active BS, suggesting that an SII value above 552×10³/mm³ may help identify active disease. Similarly, Mentesoglu et al. demonstrated that SII was significantly higher in active BS, with a proposed cutoff of 526.23×10³/mm³, showing 70.4% sensitivity and 70.3% specificity, [

14].

Another emerging marker is the Systemic Inflammation Response Index (SIRI), which is calculated by the formula= Neutrophil x Monocyte/Lymphocyte, was introduced in 2016. Initially proposed as prognostic marker in malignancy, SIRI has also been explored in various diseases characterized by prominent inflammatory responses, with growing interest in its potential diagnostic and prognostic utility across diverse clinical settings [

22].

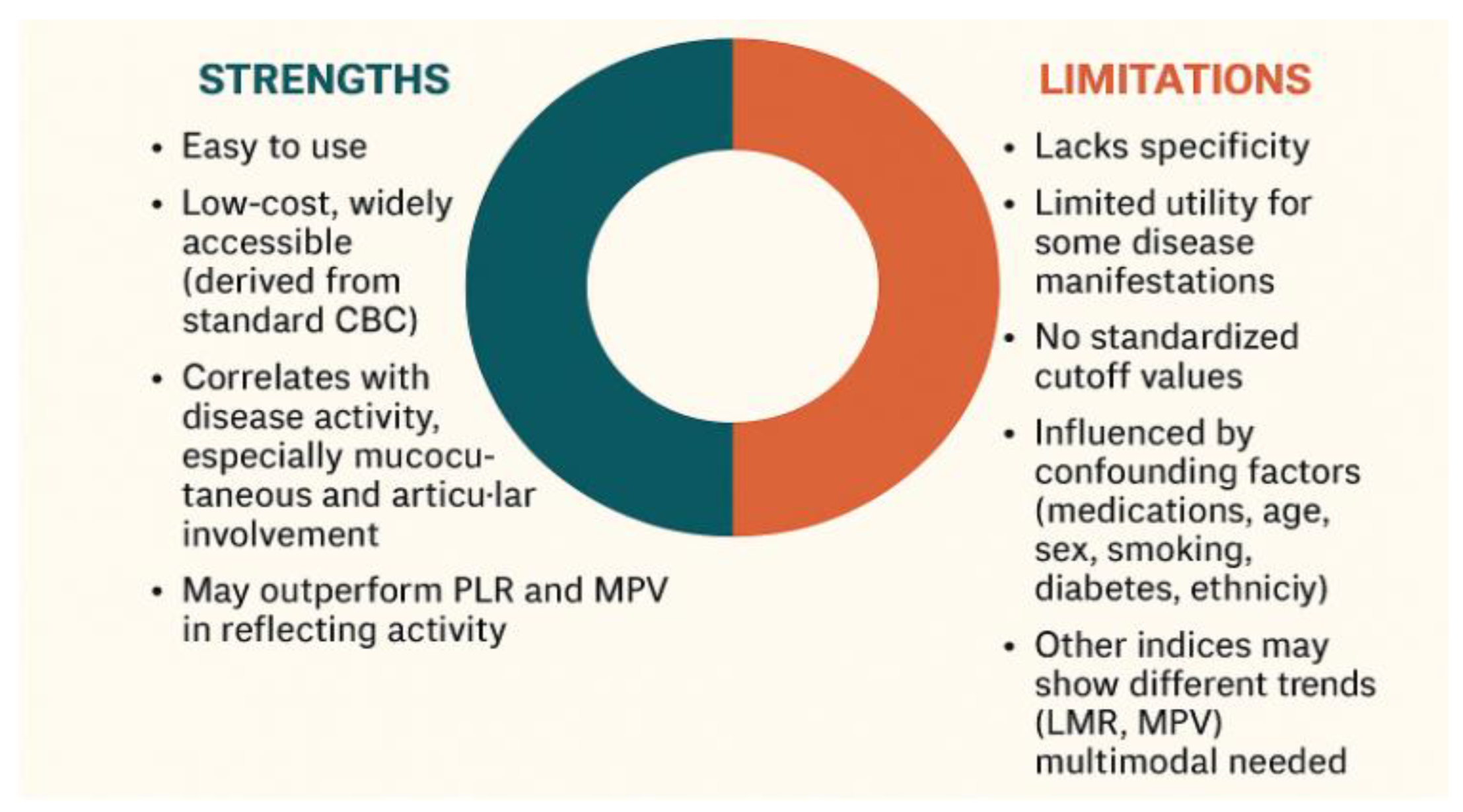

6. Strengths and Limitations in NLR Use in Rheumatic Diseases Including Behçet’s Syndrome

In BS, where specific and reliable biomarkers for diagnosis and disease monitoring remain limited, the NLR offers several notable advantages. Unlike clinical symptoms, which may be subjective and influenced by patient perception, NLR provides objective and quantifiable indicator of systemic inflammation. It is non-invasive, inexpensive, widely accessible and easily derived from routine blood tests without requiring specialized assays. NLR reflects the underlying immune dysregulation central to BS pathogenesis by incorporating both neutrophilia and relative lymphopenia. Several studies have shown significant correlation between elevated NLR and disease activity in BS, including specific manifestations such as vascular involvement and ocular flares. NLR may serve as a valuable adjunct to clinical evaluation, particularly in resource-limited settings, by supporting flare assessment and treatment decisions. Its integration into routine assessment could enhance the precision of disease activity evaluation and complement clinical judgment.

Despite its advantages, NLR presents several limitations. The primary concern is its lack of specificity. Elevated NLR values may be observed in wide range of non-rheumatic conditions, including infections, malignancies, psychological stress, and metabolic disorders [

6,

7]. Additionally, while NLR has shown consistent correlation with mucocutaneous and articular involvement in BS, its utility may be limited in assessing other disease manifestations. Another notable challenge is the absence of standardized cutoff values, complicating its uniform application in clinical practice [

5,

22]. Furthermore, various confounding factors, including medication use, age, sex, smoking status, obesity, diabetes mellitus, and ethnicity, influence NLR values and hinder their interpretability [

24,

30]. Moreover, broader hematologic profiling suggests that while NLR and PLR tend to rise with BS activity, other indices such as the lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio and MPV may display inverse or non-linear trends, supporting the need for multimodal approach to disease monitoring [

27].

Several key considerations must be addressed for the effective clinical application of NLR, including sufficient time for proper contextual interpretation. Ideally, NLR should be measured at multiple time points, as tracking its dynamic fluctuations may enhance clinical relevance. It has been proposed that calculating an average NLR across different stages of disease, rather than relying on a single-point measurement, could yield more reliable insights. Similarly, the use of delta (∆) NLR—reflecting changes from baseline—may improve its predictive and prognostic value. However, the optimal method for NLR assessment, whether through serial monitoring, baseline comparison, or averaging, remains to be defined.

Therefore, large-scale prospective studies are still needed to validate its clinical utility, establish standardized cutoff values, and determine its precise role in various clinical contexts. Until such evidence is available and consensus is reached, we believe that NLR can not be adopted for routine use in daily clinical practice.

Figure 3 illustrates the key strengths and limitations of using NLR as a biomarker in BS, highlighting its accessibility and clinical utility, alongside important constraints related to specificity, confounders, and variability across disease manifestations.

7. Future Research Directions

Several key directions may enhance the clinical utility and research applications of NLR in BS. Establishing standardized cutoff values is essential, taking into consideration organ-specific involvement and individual factors such as age, sex, and ethnicity. Prospective multicenter studies are needed to validate its diagnostic and prognostic validity across other BS populations.

Integrating NLR into composite disease activity indices or predictive models may further improve its relevance in clinical decision-making. Additionally, longitudinal studies assessing NLR dynamics over time in response to treatment could provide valuable insights into disease monitoring and flare prediction.

8. Conclusion

NLR is a simple, accessible, and cost-effective biomarker that has shown consistent correlation with disease activity in BS, particularly in cases with mucocutaneous, articular, ocular, and vascular involvement as well as an indicator of treatment response. It may offer valuable adjunct to clinical evaluation and can enhance the ability to track systemic inflammation and help tailor treatment for specific patients. NLR has the potential to serve as prognostic marker for disease severity and even mortality, provided that relevant potential confounding factors are identified and taken into account. Nevertheless, several limitations—including the lack of specificity, influence of confounding factors, and absence of standardized cutoff values—currently preclude the routine use of NLR in clinical practice. Its variability across disease stages and organ involvement necessitates further refinement in measurement strategy.

Future prospective, multicenter studies are essential to validate its clinical utility, define standardized thresholds, and determine the best way to integrate NLR into disease activity indices. Until then, NLR should be considered a valuable adjunctive tool—particularly in resource-limited settings—but not a standalone marker for decision-making in BS.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the supporting staff and colleagues who contributed to the development of this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Saadoun D, Bodaghi B, Cacoub P. Behçet’s Syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2024 Feb 15;390(7):640-651. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le Joncour A, Cacoub P, Boulaftali Y, Saadoun D. Neutrophil, NETs and Behçet’s disease: A review. Clin Immunol. 2023 May;250:109318. Epub 2023 Apr 3. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neves FS, Spiller F. Possible mechanisms of neutrophil activation in Behçet’s disease. Int Immunopharmacol. 2013 Dec;17(4):1206-10. Epub 2013 Aug 23. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 1st Workshop of the International Society for Behcet’s Disease (ISBD) on Pathophysiology and Treatment of Behcet’s Disease. Kuhtai, Austria, 2-5 April 2003. Abstracts. Arthritis Res Ther. 2003;5 Suppl 2:1-13. [PubMed]

- Zahorec, R. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio, past, present and future perspectives. Bratisl Lek Listy. 2021;122(7):474-488. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, M.; Graubard, B.I.; Rabkin, C.S.; et al. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio and mortality in the United States general population. Sci Rep 2021, 11, 464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell CD, Parajuli A, Gale HJ, Bulteel NS, Schuetz P, de Jager CPC, Loonen AJM, Merekoulias GI, Baillie JK. The utility of peripheral blood leucocyte ratios as biomarkers in infectious diseases: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Infect. 2019 May;78(5):339-348. Epub 2019 Feb 22. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Mangoni AA, Zinellu A. Diagnostic accuracy of the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio and the platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio in rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Exp Med. 2024 Sep 4;24(1):207. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Pan L, Du J, Li T, Liao H. Platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio and neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio associated with disease activity in patients with Takayasu’s arteritis: a case-control study. BMJ Open. 2017 May 4;7(4):e014451. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wu Y, Chen Y, Yang X, Chen L, Yang Y. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) and platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio (PLR) were associated with disease activity in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Int Immunopharmacol. 2016 Jul;36:94-99. Epub 2016 Apr 22. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mihai A, Caruntu A, Opris-Belinski D, Jurcut C, Dima A, Caruntu C, Ionescu R. The Predictive Role of Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio (NLR), Platelet-to-Lymphocyte Ratio (PLR), Monocytes-to-Lymphocyte Ratio (MLR) and Gammaglobulins for the Development of Cutaneous Vasculitis Lesions in Primary Sjögren’s Syndrome. J Clin Med. 2022 Sep 21;11(19):5525. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ma L, Pang X, Ji G, Ma X, Li J, Chang Y, Ma C. Application of the neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio in the diagnosis and activity determination of ulcerative colitis: A meta-analysis and systematic review. Medicine (Baltimore). 2021 Oct 22;100(42):e27551. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Rifaioglu EN, Bülbül Şen B, Ekiz Ö, Cigdem Dogramaci A. Neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio in Behçet’s disease as a marker of disease activity. Acta Dermatovenerol Alp Pannonica Adriat. 2014;23(4):65-7. [PubMed]

- Mentesoglu D, Atakan N. The association between Behçet disease activity and elevated systemic immune-inflammation index: A retrospective observational study in a tertiary care hospital. Natl Med J India. 2024 Mar-Apr;37(2):74-78. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahin S, Akoqlu T, Direskeneli H, Sen LS, Lawrence R. Neutrophil adhesion to endo- thelial cells and factors affecting adhesion in patients with Behçet’s disease. Ann Rheum Dis 1996;55:128–33.

- Li S, Ying S, Wang Y, Lv Y, Qiao J, Fang H. Neutrophil extracellular traps and neutrophilic dermatosis: an update review. Cell Death Discov. 2024 Jan 10;10(1):18. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Korkmaz, S.; Erturan, İ.; Nazıroğlu, M.; et al. Colchicine Modulates Oxidative Stress in Serum and Neutrophil of Patients with Behçet Disease Through Regulation of Ca2+ Release and Antioxidant System. J Membrane Biol 2011, 244, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- L. Glennon-Alty, A.P. L. Glennon-Alty, A.P. Hackett, E.A. Chapman, H.L. Wright, Neutrophils and redox stress in the pathogenesis of autoimmune disease, Free Radic. Biol. Med. 125 (2018) 25–35. [CrossRef]

- Becatti M, Emmi G, Silvestri E, Bruschi G, Ciucciarelli L, Squatrito D, Vaglio A, Taddei N, Abbate R, Emmi L, Goldoni M, Fiorillo C, Prisco D. Neutrophil Activation Promotes Fibrinogen Oxidation and Thrombus Formation in Behçet Disease. Circulation. 2016 Jan 19;133(3):302-11.

- Le Joncour A, Martos R, Loyau S, Lelay N, Dossier A, Cazes A, Fouret P, Domont F, Papo T, Jandrot-Perrus M, Bouton MC, Cacoub P, Ajzenberg N, Saadoun D, Boulaftali Y. Critical role of neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) in patients with Behcet’s disease. Ann Rheum Dis. 2019 Sep;78(9):1274-1282. Epub 2019 May 30. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zahorec, R. Ratio of neutrophil to lymphocyte counts--rapid and simple parameter of systemic inflammation and stress in critically ill. Bratisl Lek Listy. 2001;102(1):5-14. English, Slovak. [PubMed]

- Islam MM, Satici MO, Eroglu SE. Unraveling the clinical significance and prognostic value of the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio, platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio, systemic immune-inflammation index, systemic inflammation response index, and delta neutrophil index: An extensive literature review. Turk J Emerg Med. 2024 Jan 8;24(1):8-19. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Buonacera A, Stancanelli B, Colaci M, Malatino L. Neutrophil to Lymphocyte Ratio: An Emerging Marker of the Relationships between the Immune System and Diseases. Int J Mol Sci. 2022 Mar 26;23(7):3636. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Azab B, Camacho-Rivera M, Taioli E. Average Values and Racial Differences of Neutrophil Lymphocyte Ratio among a Nationally Representative Sample of United States Subjects. PLOS One 2014; 9 (11): e112361.

- Lee JS, Kim NY, Na SH, Youn YH, Shin CS. Reference values of neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio, lymphocyte–monocyte ratio, platelet-lymphocyte ratio, and mean platelet volume in healthy adults in South Korea. Medicine 2018; 97: e11138.

- Alan S, Tuna S, Türkoğlu EB. The relation of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio, platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio, and mean platelet volume with the presence and severity of Behçet’s syndrome. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 2015 Dec;31(12):626-31. Epub 2015 Dec 10. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Selim, Z.I.; Mostafa, N.M.; Ismael, E.O.; et al. Platelet lymphocyte ratio, lymphocyte monocyte ratio, mean platelet volume, and neutrophil lymphocyte ratio in Behcet’s disease and their relation to disease activity. Egypt Rheumatol Rehabil 2023, 50, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balkarli A, Kucuk A, Babur H, Erbasan F. Neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio and mean platelet volume in Behçet’s disease. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2016 Jul;20(14):3045-50. [PubMed]

- Hammad M, Shehata OZ, Abdel-Latif SM, El-Din AMM. Neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio and platelet/lymphocyte ratio in Behçet’s disease: which and when to use? Clin Rheumatol. 2018 Oct;37(10):2811-2817. Epub 2018 Jul 7. Erratum in: Clin Rheumatol. 2019 Jul;38(7):2019. 10.1007/s10067-019-04583-5. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Djaballah-Ider F, Touil-Boukoffa C. Effect of combined colchicine-corticosteroid treatment on neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio: a predictive marker in Behçet disease activity. Inflammopharmacology. 2020 Aug;28(4):819-829. Epub 2020 Mar 29. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shadmanfar S, Masoumi M, Davatchi F, Shahram F, Akhlaghi M, Faezi ST, Kavosi H, Parsaei A, Moradi S, Balasi J, Moqaddam ZR. Correlation of clinical signs and symptoms of Behçet’s disease with platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio (PLR) and neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR). Immunol Res. 2021 Aug;69(4):363-371. Epub 2021 Jun 9. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avci A, Avci D, Erden F, Ragip E, Cetinkaya A, Ozyurt K, Atasoy M. Can we use the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio, platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio, and mean platelet volume values for the diagnosis of anterior uveitis in patients with Behcet’s disease? Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2017 Jul 17;13:881-886. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Elden, M.S.; Hmmad, G.; Farouk, H.; et al. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio: relation to disease activity and carotid intima-media thickness in Behçet’s disease. Egypt Rheumatol Rehabil 2018, 45, 133–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee YH, Song GG. Role of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio and platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio as potential biomarkers in Behçet’s disease: a meta-analysis. Z Rheumatol. 2024 Feb;83(Suppl 1):206-213. English. Epub 2023 Sep 14. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang Z, Su Q, Zhang L, Yang Z, Qiu Y, Mo W. Diagnostic value of hemoglobin and neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in Behcet Disease. Medicine (Baltimore). 2019 Dec;98(52):e18443. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Tanacan E, Dincer D, Erdogan FG, Gurler A. A cutoff value for the Systemic Immune-Inflammation Index in determining activity of Behçet disease. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2021 Mar;46(2):286-291. Epub 2020 Oct 10. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).