Submitted:

10 July 2025

Posted:

11 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

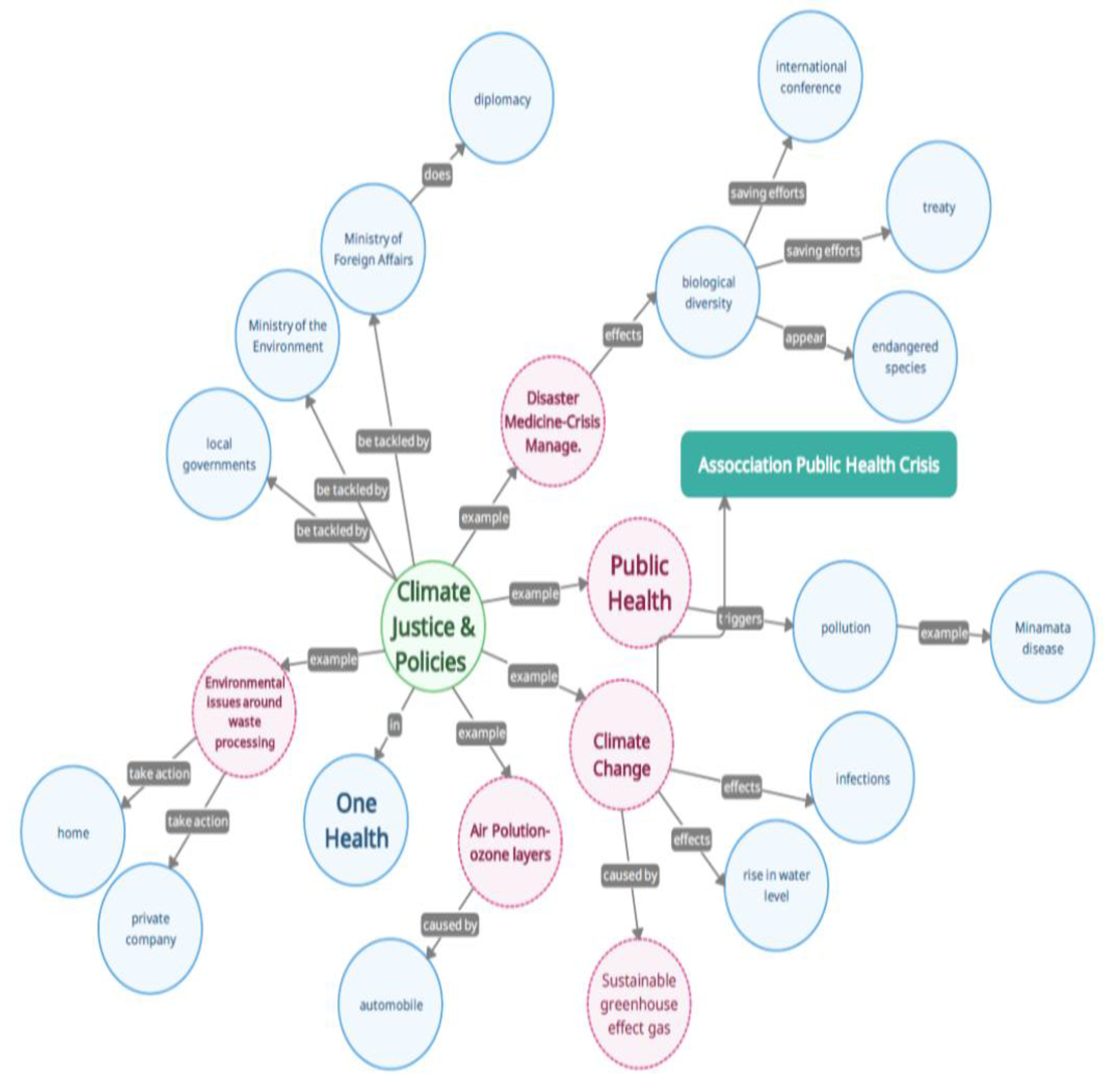

Introduction

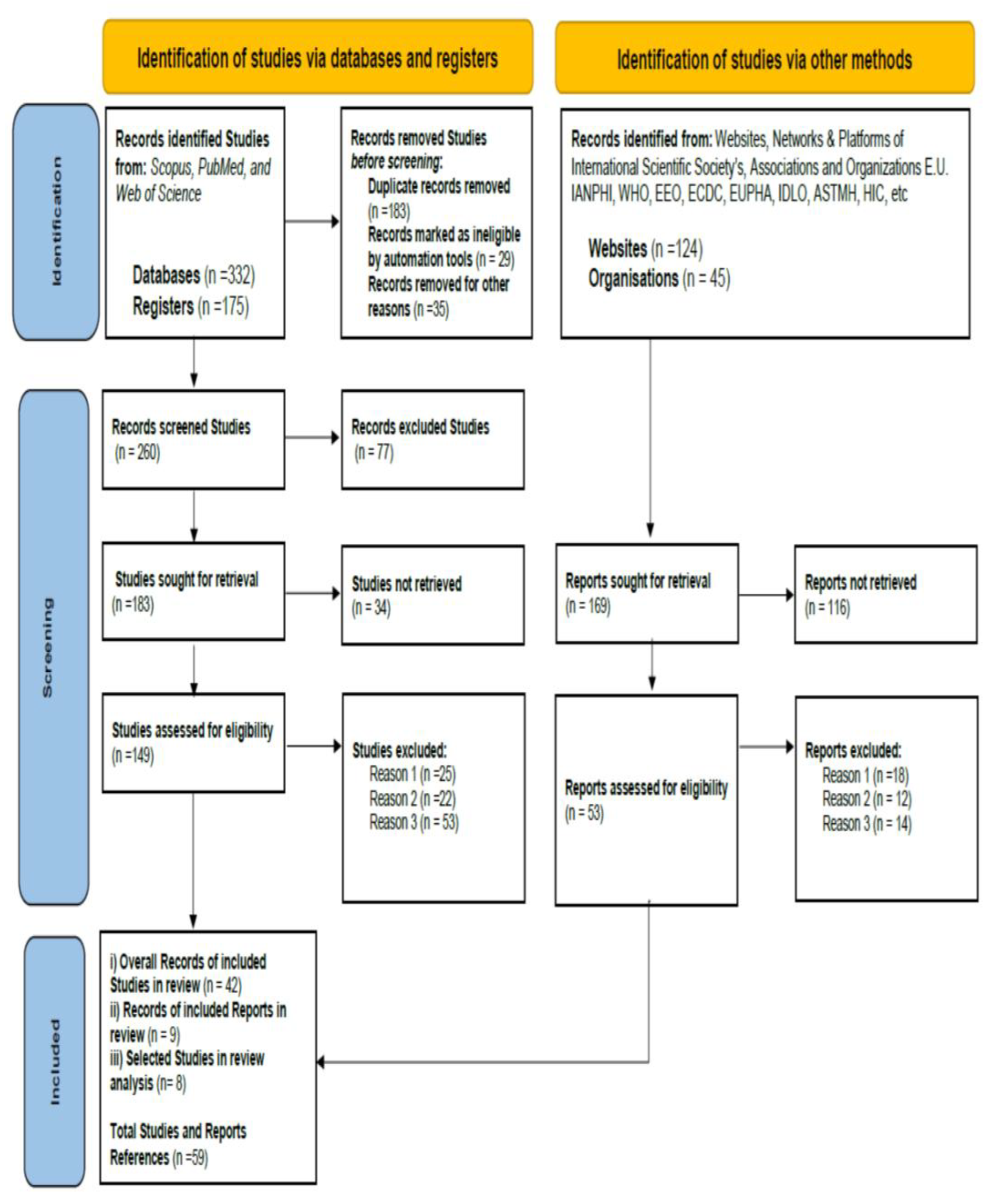

Materials and Methods

Methodology

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

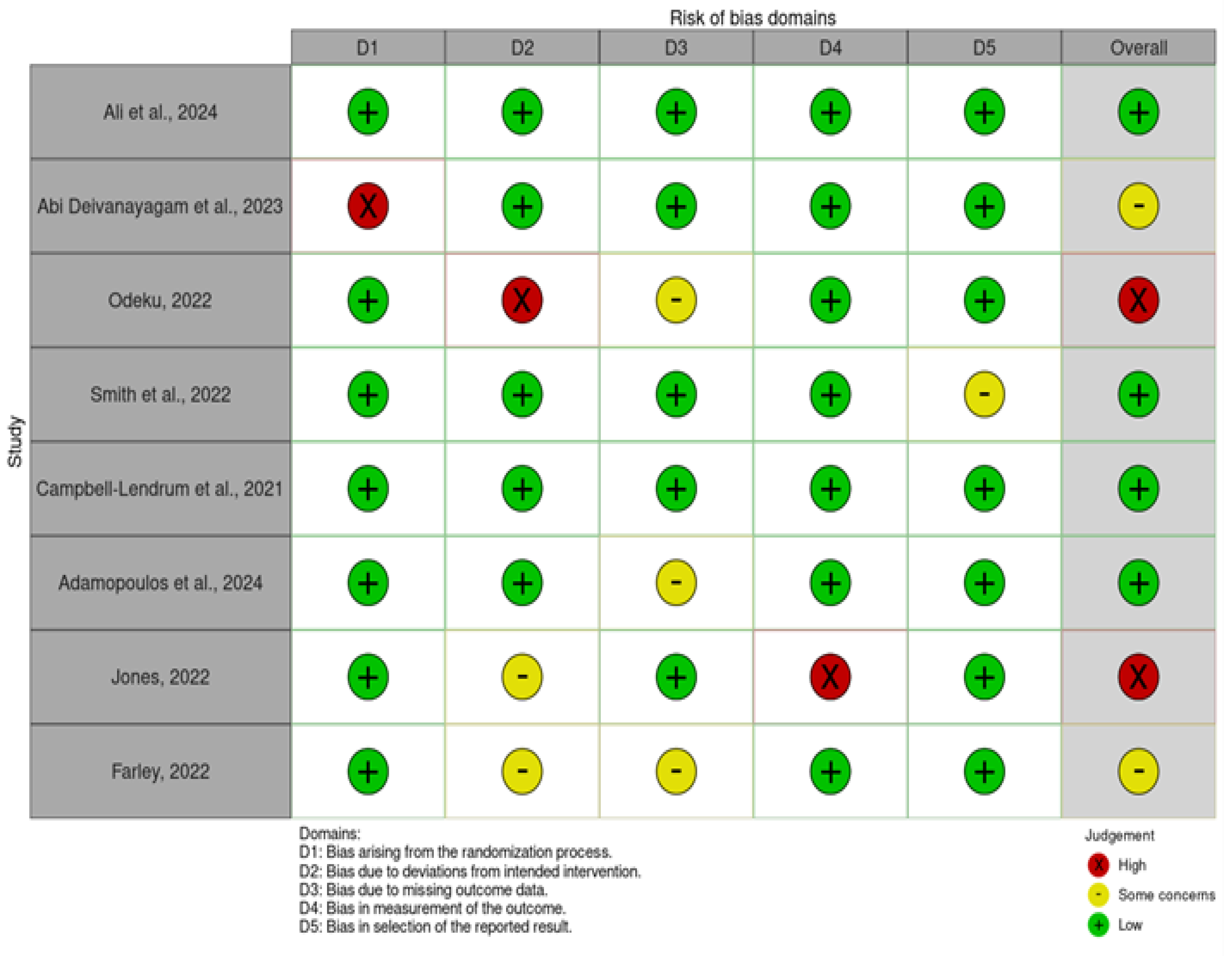

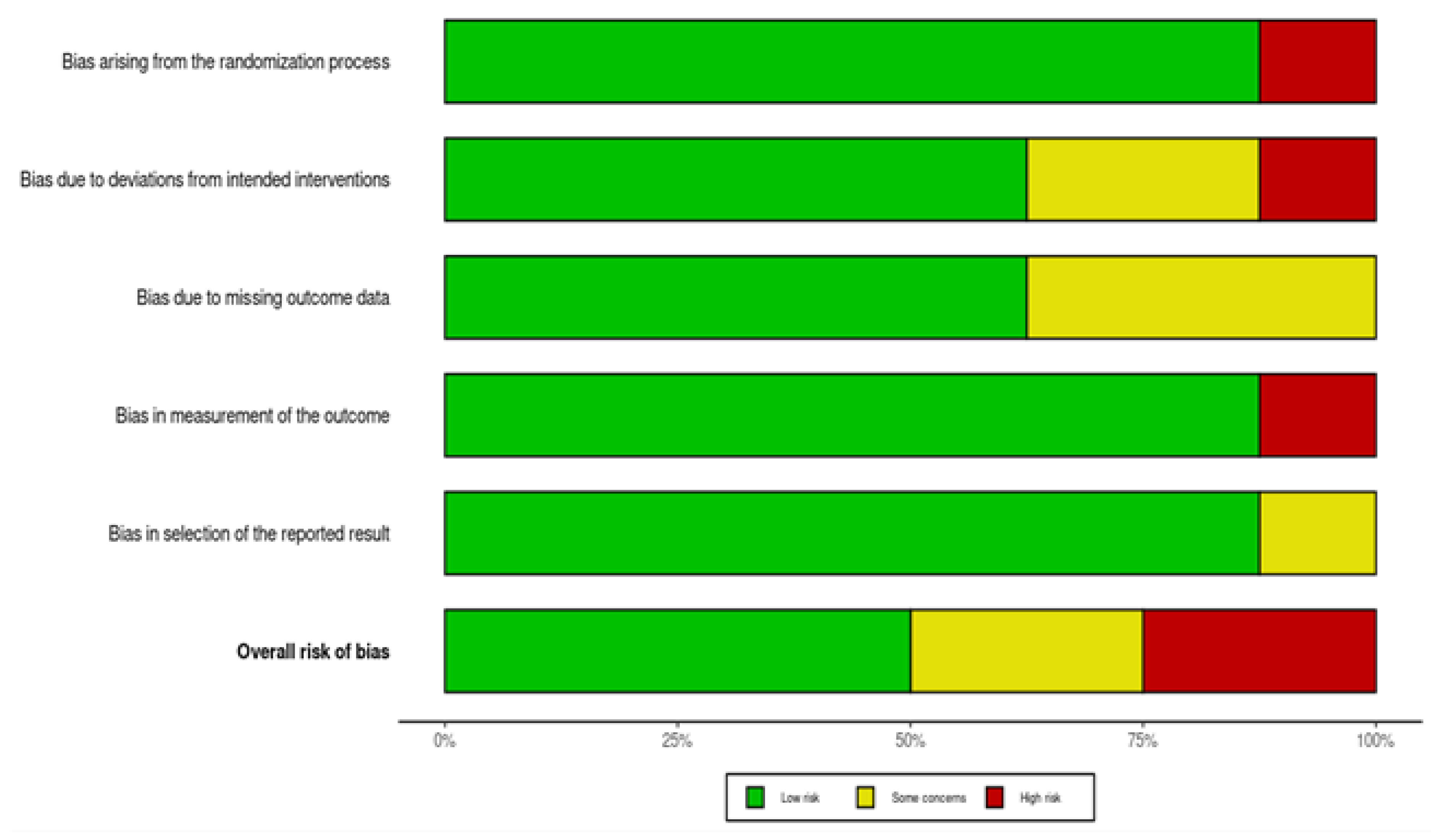

Quality Assessment of the Reviews

Statistical Analysis

Data Challenges and Gaps

Results of the Review and Discussion

Challenges in Implementing Adaptation Policies and Regulations

Policy Responses to Climate Justice Associated with One Health

Recommendations, future research directions, and limitations

Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| IANPHI | International Association of National Public Health Institutes |

| EEO | European Climate and Health Observatory |

| ECDC | European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control |

| HIC | Health in climate change |

| NPHI | National Public Health Institutes |

| EUPHA | European Public Health Association |

| E.U. | European Union |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic and Met-analysis |

| IDLO | International Development Law Organization |

| ASTMH | American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene |

References

- Ali, S.; Khan, Z.A.; Azhar, M.; Raheem, I. Investigating the Disproportionate Effects of Climate Change on Marginalized Groups and the Concept of Climate Justice in Policy-Making. Rev. Educ. Adm. LAW 2024, 7, 369–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngcamu, B.S. Climate change effects on vulnerable populations in the Global South: a systematic review. Nat. Hazards 2023, 118, 977–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorkenoo, K.; Scown, M.; Boyd, E. A critical review of disproportionality in loss and damage from climate change. WIREs Clim. Chang. 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deivanayagam, T.A.; English, S.; Hickel, J.; Bonifacio, J.; Guinto, R.R.; Hill, K.X.; Huq, M.; Issa, R.; Mulindwa, H.; Nagginda, H.P.; et al. Envisioning environmental equity: climate change, health, and racial justice. Lancet 2023, 402, 64–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Odeku, KO. Climate injustices due to the unequal and disproportionate impacts of climate change. Perspectives of Law and Public Administration. 2022.

- Smith, G.S.; Anjum, E.; Francis, C.; Deanes, L.; Acey, C. Climate Change, Environmental Disasters, and Health Inequities: The Underlying Role of Structural Inequalities. Curr. Environ. Heal. Rep. 2022, 9, 80–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khine, M.M.; Langkulsen, U. The Implications of Climate Change on Health among Vulnerable Populations in South Africa: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2023, 20, 3425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farley, M. Making the connections: resource extraction, prostitution, poverty, climate change, and human rights. Int. J. Hum. Rights 2021, 26, 1032–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonn, B.; Hawkins, B.; Rose, E.; Marincic, M. A futures perspective of health, climate change and poverty in the United States. Futures 2021, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.; Eklund, E. Climate change impacts in coastal bangladesh: migration, gender and environmental injustice. Asian Aff. 2021, 52, 155–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yael Wright C, Eleanor Moore C, Chersich M, Hester R et al. A Transdisciplinary Approach to Address Climate Change Adaptation for Human Health and Well-Being in Africa. 2021.

- Nguyen, T.T.; Grote, U.; Neubacher, F.; Rahut, D.B.; Do, M.H.; Paudel, G.P. Security risks from climate change and environmental degradation: implications for sustainable land use transformation in the Global South. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2023, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birkmann J, Liwenga E, Pandey R, Boyd E, Djalante R, Gemenne F, Leal Filho W, Pinho P, Stringer L, Wrathall D. Poverty, livelihoods and sustainable development.

- Campbell-Lendrum, D.; Neville, T.; Schweizer, C.; Neira, M. Climate change and health: three grand challenges. Nat. Med. 2023, 29, 1631–1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kimuli, J.B.; Di, B.; Zhang, R.; Wu, S.; Li, J.; Yin, W. A multisource trend analysis of floods in Asia-Pacific 1990–2018: Implications for climate change in sustainable development goals. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2021, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soergel, B.; Kriegler, E.; Bodirsky, B.L.; Bauer, N.; Leimbach, M.; Popp, A. Combining ambitious climate policies with efforts to eradicate poverty. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buhaug H, Von Uexkull N. Vicious circles: violence, vulnerability, and climate change. Annual Review of Environment and Resources. 2021 Oct 18; 46(1):545-68.

- Romanello M, McGushin A, Di Napoli C, Drummond P, Hughes N, Jamart L, Kennard H, Lampard P, Rodriguez BS, Arnell N, Ayeb-Karlsson S. The 2021 report of the Lancet Countdown on health and climate change: code red for a healthy future. The Lancet. 2021 Oct 30; 398(10311):1619-62.

- Adua, L. Super polluters and carbon emissions: Spotlighting how higher-income and wealthier households disproportionately despoil our atmospheric commons. Energy Policy 2022, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glennerster, R.; Jayachandran, S. Think Globally, Act Globally: Opportunities to Mitigate Greenhouse Gas Emissions in Low- and Middle-Income Countries. J. Econ. Perspect. 2023, 37, 111–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, I.; Kennard, H.; McGushin, A.; Höglund-Isaksson, L.; Kiesewetter, G.; Lott, M.; Milner, J.; Purohit, P.; Rafaj, P.; Sharma, R.; et al. The public health implications of the Paris Agreement: a modelling study. Lancet Planet. Heal. 2021, 5, e74–e83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armstrong, C.; McLaren, D. Which Net Zero? Climate Justice and Net Zero Emissions. Ethic- Int. Aff. 2022, 36, 505–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verschuuren, J. Achieving agricultural greenhouse gas emission reductions in the EU post-2030: What options do we have? Rev. Eur. Comp. Int. Environ. Law 2022, 31, 246–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitmee, S.; Green, R.; Belesova, K.; Hassan, S.; Cuevas, S.; Murage, P.; Picetti, R.; Clercq-Roques, R.; Murray, K.; Falconer, J.; et al. Pathways to a healthy net-zero future: report of the Lancet Pathfinder Commission. Lancet 2023, 403, 67–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sovacool, B.K.; Newell, P.; Carley, S.; Fanzo, J. Equity, technological innovation and sustainable behaviour in a low-carbon future. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2022, 6, 326–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adamopoulos, I.P.; Syrou, N.F.; Mijwil, M.; Thapa, P.; Ali, G.; Dávid, L.D. Quality of indoor air in educational institutions and adverse public health in Europe: A scoping review. Electron. J. Gen. Med. 2025, 22, em632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liamputtong P, Rice ZS. Health and illness. InThe Routledge Handbook of Global Development 2022 Jan 31 (pp. 469-479). Routledge.

- Amoateng, A.Y.; Biney, E.; Ewemooje, O.S. Social determinants of chronic ill-health in contemporary South Africa: a social disadvantage approach. Soc. Sci. J. 2021, 61, 653–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karapliagkou, A. Compassionate communities: Working with marginalized populations. Collaborative Practice in Palliative Care. 2021.

- Mezzina R, Gopikumar V, Jenkins J, Saraceno B, Sashidharan SP. Social vulnerability and mental health inequalities in the “Syndemic”: Call for action. Frontiers in psychiatry. 2022 May 30; 13:894370.

- Borras, A.M. Toward an Intersectional Approach to Health Justice. Int. J. Heal. Serv. 2020, 51, 206–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bejaković, P.; Škare, M.; Družeta, R.P. Social exclusion and health inequalities in the time of COVID-19. Technol. Econ. Dev. Econ. 2021, 27, 1563–1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putsoane, T.; Bhanye, J.I.; Matamanda, A. Extreme weather events and health inequalities: Exploring vulnerability and resilience in marginalized communities. Dev. Environ. Sci. 2024, 15, 225–248. [Google Scholar]

- Nayna Schwerdtle P, Irvine E, Brockington S, Devine C et al. ‘Calibrating to scale: a framework for humanitarian health organizations to anticipate, prevent, prepare for and manage climate-related health risks’. 2020.

- Adamopoulos, I.; Frantzana, A.; Syrou, N. Climate Crises Associated with Epidemiological, Environmental, and Ecosystem Effects of a Storm: Flooding, Landslides, and Damage to Urban and Rural Areas (Extreme Weather Events of Storm Daniel in Thessaly, Greece). Med. Sci. Forum 2024, 25, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Adamopoulos, I.; Frantzana, A.; Adamopoulou, J.; Syrou, N. Climate Change and Adverse Public Health Impacts on Human Health and Water Resources. Environ. Sci. Proc. 2023, 26, 178. [Google Scholar]

- Malik, I.H.; Ford, J.D. Monitoring climate change vulnerability in the Himalayas. AMBIO 2024, 54, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adamopoulos, I.; Syrou, N. Climate Change, Air Pollution, African Dust Impacts on Public Health and Sustainability in Europe. Eur. J. Public Heal. 2024, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- V Quintana A, H Mayhew S, Kovats S, Gilson L. A story of (in) coherence: climate adaptation for health in South African policies. 2024.

- Jones, A. The health impacts of climate change: why climate action is essential to protect health. Orthop. Trauma 2022, 36, 248–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gautam S, Gautam AS, Awasthi A, N R. The Urgency of Action. In Sustainable Air: Strategies for Cleaner Atmosphere and Healthier Communities 2024 Nov 28 (pp. 21-26). Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland.

- Søvold, L.E.; Naslund, J.A.; Kousoulis, A.A.; Saxena, S.; Qoronfleh, M.W.; Grobler, C.; Münter, L. Prioritizing the Mental Health and Well-Being of Healthcare Workers: An Urgent Global Public Health Priority. Front. Public Heal. 2021, 9, 679397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbas, J. Crisis management, transnational healthcare challenges and opportunities: The intersection of COVID-19 pandemic and global mental health. Res. Glob. 2021, 3, 100037–100037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Health Organization, W. Global Accelerated Action for the Health of Adolescents (AA-HA!): guidance to support country implementation. 2023.

- Benton, T.D.; Boyd, R.C.; Njoroge, W.F. Addressing the Global Crisis of Child and Adolescent Mental Health. JAMA Pediatr. 2021, 175, 1108–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hickman, C.; Marks, E.; Pihkala, P.; Clayton, S.; Lewandowski, R.E.; Mayall, E.E.; Wray, B.; Mellor, C.; van Susteren, L. Climate anxiety in children and young people and their beliefs about government responses to climate change: a global survey. Lancet Planet. Health 2021, 5, e863–e873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene (ASTMH) Green Task Force members, Dumre, S. P., LaBeaud, A. D., Ehrlich, H., Vazquez Guillamet, L. J., Ondigo, B. N., Sadarangani, S. P., Wamae, C. N., & Whitfield, K. (2022). Why Climate Action Is Global Health Action. The American journal of tropical medicine and hygiene, 107(3), 500–503.

- International Development Law Organization, “Women, Food, Land: Exploring Rule of Law Linkages”, (2017), [accessed 25 June 2025] available at: https://www.idlo.int/publications/women-food-land-exploring-rule-law-linkages-0.

- UNFCCC COP20 adopted the Lima Work Programme on Gender (subsequently renewed) to promote gender balance and achieve gender-responsive climate policy”; see UNFCCC, “The Enhanced Lima Work Programme on Gender”, [accessed 25 June 2025] available at: https://www.idlo.int/sites/default/files/pdfs/publications/a_rule_of_law_approach_to_feminist_climate_action.pdf.

- IDLO’s Policy Brief Climate Justice: A Rule of Law Approach for Transformative Climate Action highlights three key elements of achieving transformative climate action through the rule of law, 2021: [accessed 25 June 2025] available at: https://www.idlo.int/publications/climate-justice-rule-law-approach-transformative-climate-action.

- EPA. (2023). Climate Adaptation and EPA’s role. [Accessed June 25, 2025] at: https://www.epa.gov/climate-adaptation/climate-adaptation-and-epas-role.

- IPCC, 2014: Climate Change 2014: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Part A: Global and Sectoral Aspects. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change Field, C.B., V.R. Barros, D.J. Dokken, K.J. Mach, M.D. Mastrandrea, T.E. Bilir, M. Chatterjee, K.L. Ebi, Y.O. Estrada, R.C. Genova, B. Girma, E.S. Kissel, A.N. Levy, S. MacCracken, P.R. Mastrandrea, and L.L.White. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA, chapter 20, 1101-1132 pp. [Accessed June 25, 2025] at: https://www.ipcc.ch/site/assets/uploads/2018/02/WGIIAR5-PartA_FINAL.pdf.

- IANPHI (2021) Survey Results: The Role of National Public Health Institutes in Climate Change Adaptation and Mitigation, Public Health Institutes of the World, IANPHI – International Association of National Public Health Institutes. [Accessed June 25, 2025] at: https://ianphi.org/news/2021/roadmap-climate-change.html.

- WHO (2021) WHO health and climate change global survey report, World Health Organization. [Accessed June 25, 2025] at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240038509.

- Organized by: Robert Koch Institute, IANPHI (France), & Chairpersons: Angela Fehr (Germany), Sébastien Denys (France). 4. E. Workshop: The role of National Public Health Institutes and IANPHI as Key Climate Actors. Eur. J. Public Health 2022, 32 Suppl. 3, ckac129.223. [CrossRef]

- EEO, The methodology of the survey and the detailed results are available in the background document (European Climate and Health Observatory, 2024). Web report no. 20/2024 Title: The impacts of heat on health: surveillance and preparedness in Europe. EN HTML: TH-01-24-019-EN-Q - ISBN: 978-92-9480-696-3 - ISSN: 2467-3196 - doi: 10.2800/8167140. [Accessed June 25, 2025] at: https://www.eea.europa.eu/en/analysis/publications/the-impacts-of-heat-on-health.

- Alba, R.; Klepp, S.; Bruns, A. Environmental justice and the politics of climate change adaptation – the case of Venice. Geogr. Helvetica 2020, 75, 363–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGuinness, L.A.; Higgins, J.P.T. Risk-of-bias VISualization (robvis): An R package and Shiny web app for visualizing risk-of-bias assessments. Res. Synth. Methods 2021, 12, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement : an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tricco, A. C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K. K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M. D. J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Authors /Year of publication/Cite | Title |

Aim/ Study Purpose |

Overall Samples Risk of Quality Assessment | Methodology | Results/ Relevant Findings/ Outcome Measures | |

| 1 |

Ali et al., 2024 [1] |

Investigating the Disproportionate Effects of Climate Change on Marginalised Groups and the Concept of Climate Justice in Policymaking. | This study aimed to identify and examine the body of research on several sectoral pieces of evidence that affect the environment throughout Pakistan. This thorough study seeks to assess the consequences of climate change from a sociocentric perspective. | Low |

Comprehensive Review study | The study found that the research suggested that governmental interference is essential for the sustainable development of the country through strict accountability of resources and regulation implemented in the past for generating state-of-the-art climate policy. The findings of the review suggested that GHG emissions cause climate change, which has affected agriculture, livestock and forestry, weather trends and patterns, food, water and energy security, and the society of Pakistan. |

| 2 | Abi Deivanayagam et al., 2023 [4] | Envisioning environmental equity: climate change, health, and racial justice | The Health Policy has three primary aims: to highlight the unequal health impacts of climate change due to racism, xenophobia, and discrimination, historical responsibility between countries, and the interplay between climate change, health, and discrimination in affected areas globally. | Some concerns | A mixed-method approach to measures, scoping review multi-method approach to tackle three central aims. | This study revealed significant results in many circumstances. Indigenous people, migrants, and racially marginalised groups bear an unfair share of the cost of disease and mortality brought on by climate change. The findings of this article draw attention to disparities in accountability for climate change and its consequences. Outcome Measures are responsible for climate change, as well as the estimated mortality and illness risk attributed to climate change per 100,000 people in 2050, geographically. |

| 3 | Odeku, 2022 [5] | Climate Injustice due to the unequal and disproportionate impacts | The aim of this study argue that developed industrialised countries are primarily responsible for climate change due to their massive greenhouse gas emissions from their industrial activities. It calls for justice to provide adaptation and mitigation measures through international law instruments and COP agreements. | High | Review study | The results and the relevant findings upon climate injustice are primarily caused by rich developed countries, who contribute to global warming through aggressive industrialisation and competition. To achieve climate justice, international organisations should implement emission reduction strategies and promote zero-emission treaties. Fair and equal distribution of climate burden among countries, rich industrialised countries assisting poor countries and sharing the benefits. |

| 4 | Smith et al., 2022 [6] | Climate Change, Environmental Disasters, and Health Inequities: The Underlying Role of Structural Inequalities | The purpose of this study was to determine and explore the link between environmental disasters and structural inequities, highlighting how disparities in land use, natural environment, and built environment increase vulnerability to these disasters and health disparities. |

Low | Narrative Analytical Review | The study indicates a high prevalence of a direct correlation between climate change and increased frequency and intensity of natural disasters in the US, affecting both immediate and long-term health effects. The data-driven approach critically analyses the role of structural inequalities in climate-induced health disparities. Despite evidence showing, minorities and lower-income populations are disproportionately affected. |

| 5 | Campbell-Lendrum et al., 2021 [14[ | Climate change and health: three grand challenges | The main aims of the study are to illustrate the links between health and climate change and to enumerate the three "grand challenges" for preserving and advancing health in the face of climate change. The examination of the responsibilities that the health community plays in addressing these issues and promoting change both inside and beyond the health sector is also included. | Low | Review Article | The results and the relevant outcome upon the literature show that climate change poses significant health issues, largely affecting health systems. A response aimed at reducing carbon emissions, building resilient health systems, and implementing public health measures can accelerate the response. The scale and scope of the health sector response need to be proportionate to the health threat, requiring political leadership and public support. |

| 6 | Adamopoulos et al., 2024 [35] | Climate Crises Associated with Epidemiological, Environmental, and Ecosystem Effects of a Storm: Flooding, Landslides, and Damage to Urban and Rural Areas (Extreme Weather Events of Storm Daniel in Thessaly, Greece) | The long-term impacts of Storm Daniel in Greece, including flooding, landslides, and extreme weather events, have been analysed in a mixed methods review study. Focuses on the effectiveness of mitigation and adaptation strategies and policy evaluating the resilience of urban and rural areas to such events as the environmental and ecosystem effects of the storm and the needs for new guidelines upon climate justice issues. | Low | It is a mixed-method study that utilizes structured modelling techniques, forecasting methods, and review includes a variety of strategies and tools used for analyzing data. | The Findings and the Outcomes of this research show that the needs for ecological assessments are crucial for understanding the long-term effects of climate change on ecosystems. Primary to identify potential risks and inform disaster preparedness strategies. It is crucial to measure the promotion of sustainable land use and implement conservation measures for endangered species, we can mitigate future risks. Public awareness campaigns and future studies should expand this strategy to better understand the impacts of extreme weather events like Storm Daniel. |

| 7 | Jones, 2022 [40] | The health impacts of climate change: why climate action is essential to protect health | The article aims to explain why climate change is the biggest danger to world health in the twenty-first century, why immediate action is required to address it, and what part health professionals may play in this. | High | Review study | The study highlights that Climate action in healthcare can enhance greater resilience to extreme events by reducing emissions of greenhouse gases and promoting climate adaptation. Healthcare professionals play a crucial role in highlighting these threats, advocating for action to protect health and healthcare systems, and minimising environmental impacts in their clinical practice. Healthcare systems and infrastructure must be equipped to manage this unprecedented threat to global health. |

| 8 | Farley, 2022 [8] | Making the connections: resource extraction, prostitution, poverty, climate change, and human rights | The purpose of this study was to assess the exploration of the link between resource extraction, prostitution, poverty, and climate change, highlighting the negative effects of poverty, choicelessness, and the appearance of consent. | Some concerns | Review study | The study measures and highlights Climate justice and human rights, with resource extraction and poverty being significant issues. Understanding the link between these issues can help implement human rights conventions to reduce harms to survivors, climate refugees, and prostituted women. By addressing these issues, we can work towards a more equitable and sustainable future. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).